Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the effects of secondary prevention clinics run by nurses in general practice on the health of patients with coronary heart disease.

Design: Randomised controlled trial of clinics over one year with assessment by self completed postal questionnaires and audit of medical records at the start and end of the trial.

Setting: Random sample of 19 general practices in northeast Scotland.

Subjects: 1173 patients (685 men and 488 women) under 80 years with working diagnoses of coronary heart disease who did not have terminal illness or dementia and were not housebound.

Intervention: Clinic staff promoted medical and lifestyle aspects of secondary prevention and offered regular follow up.

Main outcome measures: Health status measured by the SF-36 questionnaire, chest pain by the angina type specification, and anxiety and depression by the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Use of health services before and during the study.

Results: There were significant improvements in six of eight health status domains (all functioning scales, pain, and general health) among patients attending the clinic. Role limitations attributed to physical problems improved most (adjusted difference 8.52, 95% confidence interval 4.16 to 12.9). Fewer patients reported worsening chest pain (odds ratio 0.59, 95% confidence interval 0.37 to 0.94). There were no significant effects on anxiety or depression. Fewer intervention group patients required hospital admissions (0.64, 0.48 to 0.86), but general practitioner consultation rates did not alter.

Conclusions: Within their first year secondary prevention clinics improved patients’ health and reduced hospital admissions.

Key messages

Nurse led clinics in general practice were used to promote secondary prevention to patients with coronary heart disease

Within the first year the health of patients invited to the clinics improved

Most benefit was in functional status, but chest pain improved too

There was no effects on anxiety or depression

There were significant reductions in hospital admissions in the first year

Introduction

General practitioners have been encouraged to target patients with manifest coronary heart disease for secondary prevention.1 Strong evidence exists to support this strategy; reductions in cardiovascular events and mortality can be achieved by, for example, taking aspirin,2 control of blood pressure,3 lowering lipid concentrations,4,5 exercise,6 healthy diets,7 and stopping smoking.8

A comprehensive package of secondary prevention is, however, a considerable undertaking for patients, many of whom are elderly and may have other health priorities.1 There are risks that health may worsen with polypharmacy, drug side effects, and patient discordance. Weighed against the risks, however, are possible benefits: patients may appreciate extra support, uncontrolled symptoms may be identified earlier, and health promotion to patients with angina can improve symptoms.9 We conducted a randomised trial of secondary prevention clinics run by nurses in general practice to assess their effects on uptake of secondary prevention. In this paper we report the effect on patients’ symptoms and health.

Subjects and methods

Of 28 general practices selected randomly in northeast Scotland (formerly Grampian region), 19 agreed to participate in the study.10 Patients with diagnoses of coronary heart disease in their general practice records who did not have a terminal illness or dementia and were not housebound were eligible: 1343 (71%) of a random sample of 1890 completed baseline questionnaires and agreed to participate.10

We used random numbers tables to centrally randomise patients (by individual after stratification for age, sex, and practice) to intervention or control groups. Patients assigned to the intervention group were invited to attend secondary prevention clinics during which their symptoms were reviewed; treatment was reviewed and use of aspirin promoted; blood pressure and lipid management were reviewed; and lifestyle factors were assessed and, if appropriate, behavioural change negotiated. The clinics ran for one year. Patients were invited for a first appointment during the first three months and were followed up depending on clinical circumstances (usually two to six monthly). Patients in the control group received usual care by their general practitioner.

We collected data on health and symptoms by postal questionnaire before intervention and at one year using the following instruments:

SF-36 health survey questionnaire

—This is a general outcome measure that uses eight scales to assess three aspects of health: functional status (physical functioning, social functioning, role limitations attributed to physical problems, role limitations attributable to emotional problems), wellbeing (mental health, energy and fatigue, pain), and general health perception.11 It has been validated for use in the United Kingdom.12

Angina type specification

—This is designed for use with the SF-36 questionnaire to assess several aspects of chest pain.13 Its measurements of presence, frequency, and course of chest pain have been found to predict future cardiovascular events.14

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

—A well validated and widely used instrument to assess mental state.15

We collected data about attendance at general practice by audit of general practice records. Data about hospital admissions were obtained from patients’ responses to the angina type specification.

A sample size of 1300 at baseline was projected to give 808 responders at outcome, which was sufficient to detect five point “clinically and socially relevant” differences in all SF-36 domains.11 We analysed data with standard statistical techniques on an intention to treat basis using SPSS for Windows version 6.1.3. Binary outcomes were analysed by logistic regression and continuous scales by analysis of covariance, with adjustment where appropriate for age, sex, practice, and baseline performance. Frequency of chest pain, length of hospital stay, and numbers of general practitioner consultations were analysed with the Mann-Whitney U test.

The study was effectively open because practice staff who ran the clinics knew which patients were in the intervention group. Questionnaire data were entered blind to group allocation, but masking of data collection about general practitioner consultations was impracticable because indicators were often present in medical records. The study was approved by the Grampian Health Board and University of Aberdeen joint ethics committee.

Results

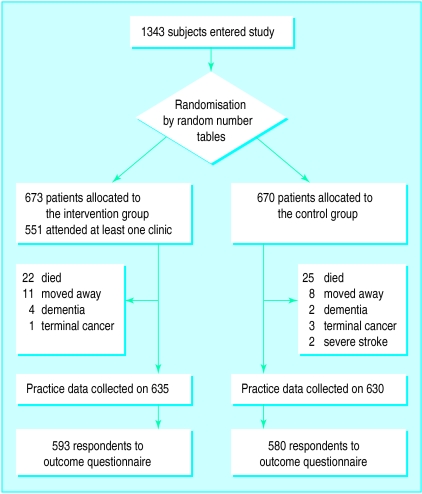

The figure shows the randomisation of subjects and follow up. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of patients in the intervention and control groups. There were no large differences, but the intervention group scored slightly better for “energy” than the control group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of control and intervention group at baseline

| No of subjects (intervention/ control) | Intervention group | Control group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) of men | 593/580 | 346 (58) | 339 (58) |

| No (%) with angina at baseline* | 554/544 | 273 (49) | 279 (51) |

| No (%) admitted to hospital in previous year | 540/518 | 132 (24) | 137 (26) |

| No (%) with myocardial infarction | 593/580 | 273 (46) | 255 (44) |

| Median (interquartile range) years since myocardial infarction | 271/254 | 5 (8) | 6 (8) |

| Mean (SD) age | 593/580 | 65.9 (7.9) | 66.3 (8.3) |

| Mean (SD) SF-36 scores: | |||

| Physical | 573/555 | 58.6 (25.7) | 57.1 (25.1) |

| Social | 592/579 | 77.3 (26.4) | 76.1 (25.9) |

| Role physical | 550/532 | 49.7 (43.6) | 47.9 (42.4) |

| Role emotional | 545/529 | 67.2 (41.4) | 67.3 (41.4) |

| Mental | 575/563 | 75.7 (17.6) | 73.9 (17.8) |

| Energy | 577/563 | 54.2 (22.3) | 51.3 (21.2) |

| Pain | 590/576 | 64.8 (26.4) | 62.9 (25.5) |

| General | 552/539 | 56.5 (22.7) | 54.7 (21.9) |

Number of subjects with chest pain in the past week.

Table 2 shows the mean changes in SF-36 scores that occurred between baseline and one year. Before the analysis of covariance we analysed variables that were thought to be potential confounders (age, sex, practice, and baseline performance) for their effect on outcome scores. No significant difference in mean change in score between practices was found in any domain with analysis of variance, and the independent samples t test showed no significant differences between sexes. Baseline performance and age, however, were found to correlate significantly with changes in scores, and we therefore adjusted for these in subsequent analyses.

Table 2.

Mean changes in SF-36 scores between baseline and one year in intervention and control groups

| Domain | No of subjects (intervention/ control) |

Mean change in score

|

Adjusted difference (95% CI)* | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group | Control group | ||||

| Physical | 554/541 | 2.28 | −1.58 | 4.33 (2.12 to 6.54) | <0.001 |

| Social | 590/577 | 0.20 | −2.79 | 3.51 (0.94 to 6.08) | 0.007 |

| Role physical | 511/497 | 4.71 | −3.04 | 8.52 (4.16 to 12.88) | <0.001 |

| Role emotional | 493/491 | 2.08 | −2.42 | 4.66 (0.11 to 9.21) | 0.045 |

| Mental | 556/532 | 0.32 | −0.13 | 1.05 (−0.50 to 2.61) | 0.185 |

| Energy | 559/545 | 1.52 | 0.71 | 1.58 (−0.17 to 3.33) | 0.077 |

| Pain | 583/569 | 1.45 | −0.33 | 2.50 (0.18 to 4.83) | 0.035 |

| General | 514/496 | 1.06 | −0.82 | 2.34 (0.50 to 4.19) | 0.013 |

Adjusted for age and baseline performance.

Of 508 patients in the intervention group, 257 (51%) reported chest pain during the past week at baseline and 232 (46%) at one year. The corresponding figures for 498 control patients were 258 (52%) and 250 (50%). After age, sex, practice, and baseline performance were adjusted for, the odds ratio for chest pain in the intervention group was 0.81 (95% confidence interval 0.61 to 1.08, P=0.143).

Fifty one of 519 (10%) patients in the intervention group reported that the course of their chest pain was worsening (“getting a little worse” or “getting much worse”) at baseline and 37 (7%) at one year. The figures for 500 control patients were 47 (9%) and 54 (11%). After age, sex, practice, and baseline performance were adjusted for, the odds ratio was 0.59 (0.37 to 0.94, P=0.025).

Among patients reporting chest pain, the median frequency during the past week for intervention and control groups at baseline was three (P=0.110). There was no change at one year (P=0.722).

Table 3 shows the hospital anxiety and depression scores. Patients from rural practices and men were significantly less anxious, and age and baseline performance significantly correlated with anxiety and depression. These confounders were included in analysis of covariance, which confirmed that there were no significant effects from intervention (adjusted difference −0.10 (−0.42 to 0.23, P=0.560) for anxiety and −0.16 (−0.44 to 0.13, P=0.281) for depression in the intervention group).

Table 3.

Hospital anxiety and depression scores at baseline and one year for intervention and control groups

| No of subjects | Mean scores

|

Difference (95% CI) | P value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1 year | ||||

| Anxiety: | |||||

| Intervention | 556 | 5.78 | 5.77 | 0.01 (−0.24 to 0.26) | 0.932 |

| Control | 552 | 6.14 | 6.19 | −0.05 (−0.27 to 0.17) | 0.660 |

| Depression: | |||||

| Intervention | 568 | 4.50 | 4.38 | 0.11 (−0.09 to 0.32) | 0.281 |

| Control | 556 | 4.63 | 4.60 | 0.03 (−0.18 to 0.23) | 0.794 |

Paired samples t test.

Of 540 patients in the intervention group, 132 (24%) were admitted to hospital during the year before the study and 106 (20%) during the study year. The corresponding figures for 518 control patients were 137 (26%) and 145 (28%). After age, sex, general practice, and baseline performance were adjusted for the odds ratio of requiring admission to hospital for the intervention group was 0.64 (0.48 to 0.86, P=0.003). The difference was explained only partly by “cardiac” admissions: there were 36 (7%) in the intervention group and 49 (9%) in the control group during the study year. It was not due to differences in non-fatal myocardial infarctions: 13 (2%) in the intervention group, 12 (2%) in the control group.

At baseline the median length of stay in hospital was seven days in the intervention group and six in the control group (P=0.435). The median stay at one year was six days in both groups (P=0.408). The median number of general practitioner consultations in three months for intervention and control groups at baseline was one (P=0.107). There was no change at one year (P=0.488).

Discussion

We assessed the effects of secondary prevention clinics on the health of patients with established coronary heart disease in typical general practices and found that patients receive important early benefits. The effect of clinics on uptake of secondary prevention will be reported later.

Against a background of overall deterioration among the control group, the general health of patients who were invited to attend the clinics improved. There were significant differences in most domains of the SF-36 questionnaire, but the largest improvements were in functional status. It was in these aspects of health that this population scored most poorly at baseline compared with a general population12 and where, therefore, improvement might be most welcome. The lowest baseline and greatest benefit were in role limitations attributed to physical problems, and the size of this effect would be expected to be clinically and socially relevant.11

Although not directly comparable, our findings are similar to those of a study in Belfast of health promotion in patients with angina.16 The Belfast study had important differences: all its subjects had angina; the intervention did not include medical aspects of secondary prevention; numbers of patients were smaller; and the Nottingham Health Profile was used to evaluate effects on perceived health. However, significant improvements in physical mobility and trends towards improvement in most other scales were reported. Our study provides stronger evidence of benefit to all patients with coronary heart disease in more areas of health but confirms that most benefit occurs in physical aspects.

Chest pain

Fewer patients in the intervention group suffered chest pain at one year, but this difference was not significant and there were no differences in the frequencies of pain among those who reported it. Significantly fewer subjects, however, reported that their chest pain was deteriorating; such patients have been found previously to have poorer prognoses.14 Overall, therefore, the intervention caused a small but important improvement in chest pain. Once again, these findings are in line with those of the Belfast study, where health promotion was found to reduce angina.9

Anxiety and depression

Intervention produced no significant improvement in hospital anxiety and depression scores or in the mental health domain of the SF-36. However, at baseline only 14% of subjects were anxious and 6% depressed (hospital anxiety and depression score >10). These estimates and the baseline mental health scores were similar to those expected in the general population,12,17,18 so it was unsurprising that there were no psychological benefits from intervention.

Most previous studies of anxiety and depression in coronary heart disease have been conducted on patients soon after myocardial infarction, when their psychological distress peaks.19 Among patients with coronary heart disease in general practice, however, recent myocardial infarction is uncommon.10 Our results suggest that anxiety and depression do not warrant additional attention in patients with stable coronary heart disease. It was reassuring, however, that the pursuit of comprehensive secondary prevention did not lead to increased psychological distress.

Use of health services

To assess the wider impact of improved general health on patients we studied their use of health services. These patients were high users: a quarter of subjects required hospital admissions in the year before the study. During the study year, however, there was a significant reduction in the numbers of patients in the intervention group requiring hospital admissions. We would not expect the increased secondary prevention to have such an immediate effect, and, indeed, there were no significant reductions in deaths or non-fatal myocardial infarctions. Neither did the fall in other “cardiac” admissions fully account for the difference. It is possible, however, that improved general health and closer monitoring helped to avoid other hospital admissions.

Relevance and limitations

Our study relied on self completed questionnaires to measure health, but we used instruments that have been validated and used extensively.11–15 Recruitment rates of general practices and patients were good, and differences between respondents and non-respondents were modest.10 There were few exclusions and response rates were good, so the sample was reasonably representative of northeast Scotland. Local factors may affect results of clinics in other regions or countries, but the concordance between our results and those of the most similar previous study (in Belfast)9,16 suggests that our results will be widely relevant. A follow up of one year is relatively short, but improvements in secondary prevention should lead to medium and long term reductions in cardiovascular events and deaths. Longer term follow up is planned to study this.

Conclusions

Overall, secondary prevention clinics improved patients’ health. Most benefit was in functional status, but there were also improvements in chest pain and less need for hospital admissions. Targeting secondary prevention in a general practice population can achieve significant and important benefits to patients’ health within the first year.

Figure.

Randomisation and exclusion of patients in trial

Acknowledgments

We thank Sandra Skilling and Janis Bryant for help with data collection and Jeremy Grimshaw for help with the study design. The clinics were run by the following health visitors, practice nurses and district nurses: June Anderson, Liz Brown, Mary Brown, Linda Bruce, Jas Burnett, Liz Clouston, Ann Darnley, Mary Duguid, Sheena Durno, Sandra Farquharson, Cath Gilbert, Gillian Grant, Linda Harper, Fiona Leitch, Heather MacAskill, Susan McSheffrey, Kirsten Masson, Pat Murray, Lynn Phillips, Hilary Plenderleith, Shiela Rattray, Marjorie Smith, Beth Struthers, Margo Stuart, Lynette Sykes, Fiona Travis, Ann Williams, Jean Wood.

Editorialby van der Weijden and Grol and p 1430

Footnotes

Funding: Health Services and Public Health Research Committee of the Chief Scientist Office at the Scottish Office and Grampian Healthcare Trust. Accommodation and nurse time for the clinics were provided by the contributing primary care teams.

References

- 1.Moher M, Schofield T, Weston S, Fullard E. Managing established coronary heart disease. BMJ. 1997;314:69–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7100.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy. 1. Prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. BMJ. 1994;308:81–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Browner WS, Hulley SB. Clinical trials of hypertension treatment: implications for subgroups. Hypertension. 1989;13(suppl 1):151–156. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian simvastatin survival study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344:1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, Rouleau JL, Rutherford JD, Cole TG, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1001–1009. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Connor GT, Buring JE, Yusuf S, Goldhaber SZ, Olmstead EM. An overview of randomised trials of rehabilitation with exercise after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1989;80:234–244. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher M. Evidence of effectiveness of interventions for secondary prevention and treatment of coronary heart disease in primary care. Oxford: Anglia and Oxford Regional Health Authority; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daly LE. Long term effect on mortality of stopping smoking after unstable angina and myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1983;287:324–326. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6388.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cupples ME, McKnight A. Randomised controlled trial of health promotion in general practice for patients at high cardiovascular risk. BMJ. 1994;309:993–996. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6960.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell NC, Thain J, Deans HG, Ritchie LD, Rawles JM. Secondary prevention in coronary heart disease: a baseline survey of provision and possibility in general practice. BMJ. 1998;316:1430–1434. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7142.1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware JE. SF-36 health survey-manual and interpretation guide. Boston: Nimrod Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garratt AM, Ruta DA, Abdalla MI, Buckingham JK, Russell IT. The SF 36 health survey questionnaire: an outcome measure suitable for routine use within the NHS? BMJ. 1993;306:1440–1444. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6890.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pryor DB. User’s manual: Angina type specification. Bloomington: Health Outcomes Institute; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pryor DB, Shaw L, McCants CB, Lee KL, Mark DB, Harrell FE, Jr, et al. Value of the history and physical in identifying patients at increased risk for coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:81–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-2-199301150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cupples ME, McKnight A, O’Neill C, Normand C. The effect of personal health education on quality of life of patients with angina in general practice. Health Educ J. 1996;55:75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hale AS. ABC of mental health: anxiety. BMJ. 1997;314:1886–1889. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7098.1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hale AS. ABC of mental health: depression. BMJ. 1997;315:43–46. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7099.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayou R. Rehabilitation after heart attack. BMJ. 1996;313:1498–1499. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7071.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]