Abstract

Aims

Patient access to reperfusion therapy and the use of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (p-PCI) or thrombolysis (TL) varies considerably between European countries. The aim of this study was to obtain a realistic contemporary picture of how patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) are treated in different European countries.

Methods and results

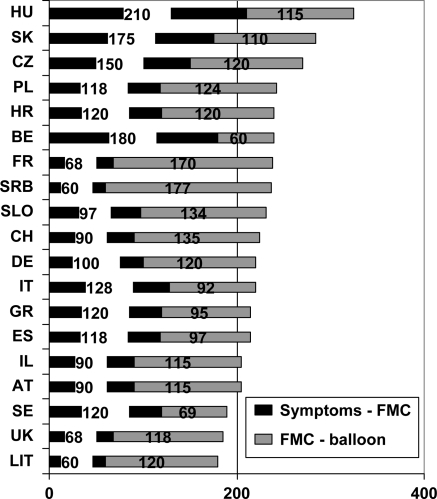

The chairpersons of the national working groups/societies of interventional cardiology in European countries and selected experts known to be involved in the national registries joined the writing group upon invitation. Data were collected about the country and any existing national STEMI or PCI registries, about STEMI epidemiology, and treatment in each given country and about PCI and p-PCI centres and procedures in each country. Results from the national and/or regional registries in 30 countries were included in this analysis. The annual incidence of hospital admission for any acute myocardial infarction (AMI) varied between 90–312/100 thousand/year, the incidence of STEMI alone ranging from 44 to 142. Primary PCI was the dominant reperfusion strategy in 16 countries and TL in 8 countries. The use of a p-PCI strategy varied between 5 and 92% (of all STEMI patients) and the use of TL between 0 and 55%. Any reperfusion treatment (p-PCI or TL) was used in 37–93% of STEMI patients. Significantly less reperfusion therapy was used in those countries where TL was the dominant strategy. The number of p-PCI procedures per million per year varied among countries between 20 and 970. The mean population served by a single p-PCI centre varied between 0.3 and 7.4 million inhabitants. In those countries offering p-PCI services to the majority of their STEMI patients, this population varied between 0.3 and 1.1 million per centre. In-hospital mortality of all consecutive STEMI patients varied between 4.2 and 13.5%, for patients treated by TL between 3.5 and 14% and for patients treated by p-PCI between 2.7 and 8%. The time reported from symptom onset to the first medical contact (FMC) varied between 60 and 210 min, FMC-needle time for TL between 30 and 110 min, and FMC-balloon time for p-PCI between 60 and 177 min.

Conclusion

Most North, West, and Central European countries used p-PCI for the majority of their STEMI patients. The lack of organized p-PCI networks was associated with fewer patients overall receiving some form of reperfusion therapy.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction, Reperfusion therapy, Thrombolysis, Primary angioplasty, Europe, Mortality, Incidence

Introduction

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and thrombolysis (TL) represent two alternative reperfusion strategies for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI). In common, TL is considered to be more widely available and can be started faster than primary PCI. In many randomized clinical trials,1–6 primary PCI has been shown to be superior to TL in reducing mortality, re-infarction, and stroke. This benefit is related to a much higher early mechanical reperfusion rate (ca. 90%) compared with pharmacological reperfusion rate (ca. 50%), to the ability of simultaneously treating the underlying stenosis and finally to the lower risk of severe bleeding. The most recent European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines7,8 recommend primary PCI as the preferred treatment whenever it is available within 90–120 min of the first medical contact (FMC). The aim of this project was to analyse the use of reperfusion treatments across Europe at the time when these new ESC guidelines were published.

Methods

The European Association for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) invited the chairpersons of the national working groups/societies of interventional cardiology in all 51 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) countries and selected experts known to be involved in the national registries of STEMI to join this project. Positive replies were received from 30 countries. Data were collected about the country and any existing national STEMI or PCI registries, about STEMI hospital admissions and treatment in each given country, and about PCI and primary PCI centres and procedures in each country. Specifically, each participating national working group (or society) provided the precise number of all existing PCI hospitals in the given country and how many of them offer non-stop (24/7) primary PCI services. Primary PCI centre (24/7) was defined as PCI hospital not using TL for the treatment of STEMI patients, in other words hospital performing primary PCI in all STEMI patients, 24 h/day and 7 days/week.

Results from 30 European countries were included in this analysis (Tables 1 and 2). These data reflect the situation in years 2007–2008 for most countries, but in 2006 or 2005 for a few, in whom the most recent data were not available.

Table 1.

National registries and other sources of the countries’ data for this study

| Country | Year | STEMI registry (name) | PCI registry (name) | Other registry or survey (name) | Expert estimate only | Completeness of STEMI capturing per period and region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 2005–07 | VIENNA STEMI registry34 | Austrian Heart Catheter Registry36 | Austrian Acute PCI Registry37 | – | 100% in Vienna region, ca. 50% for Austria |

| Belgium | 2008 | Belgian STEMI registry | Belgian Working Group Interventional Cardiology registry | 50% | ||

| Bulgaria | 2007 | National Health Insurance Fund | National Health Insurance Fund, Bulgarian WG Interventional Cardiology | – | – | 100% |

| Croatia | 2005–08 | Croatian Cardiac Society, WG for Acute Coronary Syndromes | Croatian Cardiac Society; Hospital PCI Registries | Zagreb AMI Registry; Croatian Institute of Public Health | 90% for STEMI; 100% for PCI | |

| Czech Republic | 2005–07 | CZECH registry (all ACS)19 | NRKI registry | – | – | 100% for all ACS in the CZECH registry |

| Denmark | 2007 | None | Danish Heart Registry | – | For AMI not undergoing PCI | 100% for p-PCI |

| Estonia | 2008 | Estonian Myocardial Infarction Registry, WG on Acute Coronary Syndromes | – | – | – | 100% |

| France | 2005 | FAST-MI33 | FAR | – | – | 60% of ICUs |

| Finland | 2006 | – | – | Registry of Cardiovascular Diseases, National Institute for Health and Welfare18 | – | ca. 90% for all AMI |

| Germany | 2007–08 | German Myocardial infarction registry46 | – | Herzbericht 200747 | – | 25% |

| Greece | 2006 | HELIOS14,16 | – | Hellenic Study of AMI15 | – | 100% |

| Hungary | 2004–08 | National Health Insurance Database | Registry of the Working Group of Interventional Cardiology | PCI Network in the Middle-Hungarian region (Budapest) | – | 100% for all |

| Italy | 2006–08 | VENERE,41 In-ACS (2007); BLITZ 3 (2008) | GISE Registry (GISE=Italian Society of Interventional Cardiology) | Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS) | – | 100% in Veneto Region; p-PCI 100% in GISE (all Italy); 80% in BLITZ 3 |

| Israel | 2006 | ACSIS | – | – | – | 100% |

| Latvia | 2008 | Latvian registry of acute coronary syndromes | Latvian registry of acute coronary syndromes | – | – | 100% |

| Lithuania | 2007–08 | – | Lithuanian PCI registry | – | Yes for AMIs without PCI | 100% for p-PCI only |

| F.Y.R. Macedonia | 2007–08 | – | Hospital based registries in all existing PCI centres | – | – | 95% in Skopje, ca. 80% for Macedonia |

| The Netherlands | 2008 | – | Dutch National PCI Registry (BHN) | – | – | – |

| Norway | 2007 | – | PCI-hospital based registries | – | For patients not treated by PCI | Not known (PCI data only) |

| Poland | 2004–07 | PL-ASC Registry | PCI registry of the WG on Cardiovascular Interventions of the Polish Cardiac Society | – | 100% | |

| Portugal | 2008 | National ACS Registry 2002,43 updated 200944 | – | – | – | N.A. |

| Romania | 2007–08 | RO-STEMI | – | – | – | 100% |

| Serbia | 2007 | National Institute for Health | Working group on interventional cardiology42 | 100% | ||

| Slovakia | 2007 | SLOVAKS registry | Registry of the Working Group Interventional Cardiology (Slovak Society of Cardiology) | – | – | 46% of all STEMI and 100% of p-PCI in Slovakia |

| Slovenia | 2007 | National survey | National survey | – | – | 100% |

| Spain | 2007 | – | Registro Español de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista45 | – | Yes for AMIs without PCI | N.A. |

| Sweden | 2007 | RIKS-HIA | SCAAR | – | – | 100% |

| Switzerland | 2007 | AMIS Plus (STEMI/NSTEMI/UA registry48–50) | Swiss PCI survey51 | – | – | 100% for p-PCI, 43% for STEMIs |

| Turkey | 2007 | TUMAR registry | – | – | Yes, partly | N.A. |

| UK | 2005–08 | Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP)38 | British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS)39 and Central Cardiac Audit database (CCAD)40 | – | – | 100% |

Table 2.

Population data and acute myocardial infarction annual incidence

| Country | Country population (www.populationmondiale.com) | Hospitalized STEMI/year | STEMI/100 thousand/year | Hospitalized AMI (any) | AMI/100 thousand/year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 8 199 783 | 7800 | 95 | 16 000 | 195 |

| Belgium | 10 584 534 | 7000 | 66 | 12 000 | 114 |

| Bulgaria | 7 640 238 | 8726 | 114 | 11 285 | 148 |

| Croatia | 4 493 312 | 3600 | 82 | N.A. | N.A. |

| Czech Republic | 10 228 744 | 6761 | 66 | 20 048 | 196 |

| Denmark | 5 468 120 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Estonia | 1 315 912 | 1751 | 133 | 3502 | 266 |

| France | 62 448 977 | 35 000 | 55 | 65 000 | 105 |

| Finland | 5 300 484 | 4674 | 88 | 16 446 | 310 |

| Germany | 82 217 837 | 100 000 | 121 | 208 000 | 250 |

| Greece | 10 706 290 | 11 780 | 110 | 19 853 | 185 |

| Hungary | 9 956 108 | 8900 | 89 | 18 500 | 186 |

| Italy | 58 147 733 | 67 500 | 116 | 147.500 | 254 |

| Israel | 7 337 000 | 5500 | 75 | 10 000 | 136 |

| Latvia | 2 270 894 | 1437 | 63 | N.A. | N.A. |

| Lithuania | 3 575 439 | 3000 | 84 | N.A. | N.A. |

| F.Y.R. Macedonia | 2 049 613 | 1765 | 86 | N.A. | N.A. |

| The Netherlands | 16 405 399 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Norway | 4 703 779 | 3900 | 83 | 12 650 | 276 |

| Poland | 38 518 241 | 50 000 | 130 | 90 000 | 234 |

| Portugal | 10 642 836 | 11 104 | 104 | N.A. | N.A. |

| Romania | 22 276 056 | 10 000 | 45 | 20 000 | 90 |

| Serbia | 7 400 000 | 6079 | 82 | 8655 | 117 |

| Slovakia | 5 447 522 | 3635 | 67 | 7635 | 140 |

| Slovenia | 2 009 245 | 1210 | 60 | N.A. | N.A. |

| Spain | 45 116 894 | 40 000 | 89 | 120 000 | 266 |

| Sweden | 9 031 088 | 6000 | 66 | 21 000 | 232 |

| Switzerland | 7 593 494 | N.A. | N.A. | 11 337 | 149 |

| Turkey | 70 586 256 | 100 000 | 142 | 220 000 | 312 |

| UK | 60 776 238 | 27 000 | 44 | 105 000 | 173 |

STEMI, ST elevation acute myocardial infarction; AMI, acute myocardial infarction, N.A., not available.

Those national data already published are listed in the references section9–27 and the names of ongoing registries and/or surveys are listed in the appendix and more details in Table 1.

Besides obtaining the numbers from the individual countries, the contributors were also asked to describe subjectively, what they consider to be the main barriers for better p-PCI implementation and to comment on the possible influence of hospital/staff reimbursement on the local situation.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented in the descriptive format as we received them from each individual country (see appendix for the list of contributors). The SPSS 12.0 statistical package was used to fit the linear regression lines.

Results

Annual incidence of hospital admission for acute myocardial infarction

The annual incidence of hospital admission for any acute myocardial infarction (AMI) varied between 90–312/100 000 inhabitants/year and the incidence of hospital admissions for STEMI alone between 44–142/100 000 inhabitants/year (Table 2).

Reperfusion strategy use

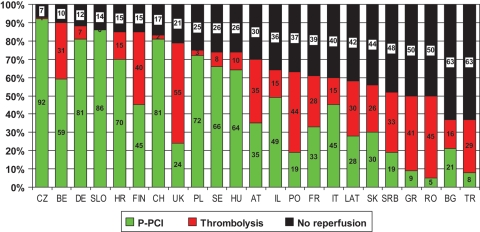

Primary PCI is the dominant reperfusion strategy in 16 countries and TL in 8 countries. From five countries (Denmark, Estonia, Lithuania, Norway, and Spain), only information about primary PCI (and not about TL) was available. The use of a p-PCI strategy varies between 5 and 92% (of all STEMI patients) and the use of TL between 0 and 55%. Any reperfusion treatment (p-PCI or TL) is used in 37–93% of STEMI patients (Figure 1). Overall, in those countries using TL as the dominant strategy, the overall population receiving some form of reperfusion therapy is lower (only 55% patients are treated, although this varied considerably from country to country).

Figure 1.

Hospitalized STEMI treatment in Europe (data from national registries or surveys). 100%, all hospitalized STEMI patients in each given country; green colour, STEMI patients treated by primary PCI; red colour, STEMI patients treated by thrombolysis; black colour, STEMI patients not treated with any reperfusion. Countries abbreviations: CZ, Czech Republic; SLO, Slovenia; DE, Germany; CH, Switzerland; PL, Poland; HR, Croatia; SE, Sweden; HU, Hungary; BE, Belgium; IL, Israel; IT, Italy; FIN, Finland; AT, Austria; FR, France; SK, Slovakia; LAT, Latvia; UK, United Kingdom; BG, Bulgaria; PO, Portugal; SRB, Serbia; GR, Greece; TR, Turkey; RO, Romania.

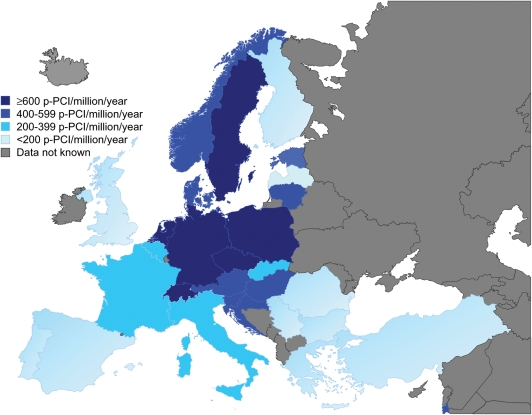

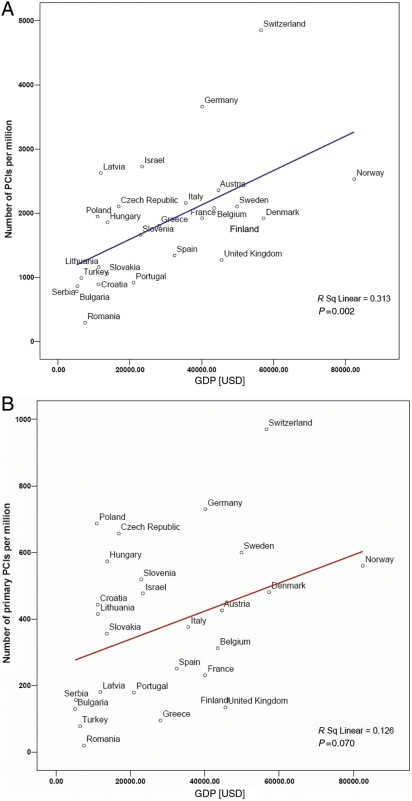

The population need for primary PCI services

The number of primary PCI procedures per 100 000 inhabitants per year (Table 3; Figure 2) ranged from 2 to 97. The mean population served by a single p-PCI centre (Table 4) varies between 0.3 and 7.4 million inhabitants. In those countries offering p-PCI services to the majority of their STEMI patients, this population varies between 0.3 and 1.1 million per centre. There was a weak correlation between numbers of PCI procedures and the gross domestic product per capita (Figure 3; Table 3).

Table 3.

Percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) per one million inhabitants compared with gross domestic product (GDP) per capital (in US dollars, according to the UN statistics for 2007, http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/socind/inc-eco.htm)

| Country | All PCIs/year | All PCIs/million | Primary PCIs/year (% of all PCIs) | Primary PCIs/million | GDP per capita (US$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 19 342 | 2358 | 3500 (18%) | 426 | 44 652 |

| Belgium | 22 000 | 2079 | 3300 (15%) | 312 | 43 469 |

| Bulgaria | 6000 | 785 | 1801 (30%) | 236 | 5177 |

| Croatia | 4000 | 890 | 1150 (22%) | 255 | 11 256 |

| Czech Republic | 21 531 | 2105 | 6720 (31%) | 657 | 16 880 |

| Denmark | 10 500 | 1920 | 2691 (26%) | 481 | 57 256 |

| Estonia | 2471 | 1878 | 485 (20%) | 369 | 15 932 |

| France | 120 000 | 1921 | 14 400 (12%) | 231 | 40 089 |

| Finland | 8894 | 1678 | 826 (9%) | 156 | 46 370 |

| Germany | 299 600 | 3660 | 60 000 (20%) | 730 | 40 162 |

| Greece | 19 311 | 1804 | 1022 (5%) | 95 | 28 111 |

| Hungary | 18 500 | 1858 | 5700 (31%) | 573 | 13 777 |

| Italy | 128 428 | 2161 | 22 421 (17%) | 376 | 35 585 |

| Israel | 20 000 | 2726 | 3500 (17%) | 477 | 23 382 |

| Latvia | 5956 | 2624 | 410 (7%) | 181 | 11 930 |

| Lithuania | 4143 | 1159 | 1485 (36%) | 415 | 11 307 |

| F.Y.R. Macedonia | 2516 | 1227 | 981 (39%) | 478 | 3703 |

| The Netherlands | 36 367 | 2217 | 11 201 (31%) | 683 | 46 669 |

| Norway | 11 890 | 2530 | 2632 (22%) | 560 | 82 464 |

| Poland | 75 024 | 1948 | 26 457 (35%) | 687 | 11 007 |

| Portugal | 9873 | 919 | 1902 (19%) | 179 | 20 990 |

| Romania | 6560 | 294 | 450 (7%) | 20 | 7523 |

| Serbia | 6395 | 864 | 1161 (18%) | 157 | 5382 |

| Slovakia | 5730 | 1061 | 1924 (34%) | 356 | 13 701 |

| Slovenia | 3336 | 1661 | 1043 (31%) | 519 | 22 936 |

| Spain | 60 457 | 1340 | 11 322 (19%) | 251 | 32 450 |

| Sweden | 19 000 | 2103 | 5421 (29%) | 600 | 49 873 |

| Switzerland | 36 817 | 4849 | 7363 (20%) | 970 | 56 578 |

| Turkey | 70 000 | 991 | 5500 (8%) | 78 | 6511 |

| UK | 77 373 | 1273 | 8153 (11%) | 134 | 45 549 |

Figure 2.

Primary PCIs per year per million inhabitants in European countries. Grey colour, no data available; blue colour, countries participating in this study.

Table 4.

Numbers of PCI centres and population per one centre

| Country | All PCI centres | Population per any PCI centre | Primary PCI centres (non-stop, 24/7) | Population per primary PCI centre (24/7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 34 | 282 751 | 24 | 341 000 |

| Belgium | 36 | 294 015 | 30 | 352 817 |

| Bulgaria | 21 | 363 820 | 9 | 850 000 |

| Croatia | 10 | 449 331 | 8 | 561 664 |

| Czech Republic | 22 | 464 943 | 22 | 464 943 |

| Denmark | 7 | 781 160 | 5 | 1 093 624 |

| Estonia | 3 | 438 637 | 2 | 657 956 |

| France | 210 | 297 376 | 200 | 312 245 |

| Finland | 24 | 220 853 | 2 | 2 650 242 |

| Germany | 430 | 190 000 | 310 | 265 000 |

| Greece | 40 | 267 657 | 10 | 1 071 000 |

| Hungary | 16 | 622 257 | 13 | 765 854 |

| Italy | 242 | 240 270 | 164 | 354 559 |

| Israel | 22 | 333 500 | 16 | 458 563 |

| Latvia | 5 | 454 179 | 1 | 2 270 894 |

| Lithuania | 6 | 595 906 | 3 | 1 191 813 |

| F.Y.R.Macedonia | 3 | 683 204 | 3 | 683 204 |

| The Netherlands | 22 | 745 700 | 22 | 745 700 |

| Norway | 8 | 587 500 | 6 | 783 963 |

| Poland | 95 | 405 455 | 74 | 520 516 |

| Portugal | 19 | 560 158 | 9 | 1 182 555 |

| Romania | 12 | 1 856 338 | 0 | N.A. |

| Serbia | 9 | 822 222 | 1 | 7 400 000 |

| Slovakia | 6 | 916 666 | 4 | 1 375 000 |

| Slovenia | 5 | 401 849 | 2 | 1 004 745 |

| Spain | 129 | 349 743 | 56 | 805 658 |

| Sweden | 29 | 311 417 | 13 | 694 699 |

| Switzerland | 27 | 281 240 | 20 | 379 675 |

| Turkey | 157 | 449 592 | 35 | 2 016 742 |

| UK | 98 | 620 165 | 23 | 2 642 445 |

Primary PCI centre (24/7) was defined as PCI hospital not using thrombolysis for the treatment of STEMI patients, in other words hospital performing primary PCI in all STEMI patients, 24 h/day and 7 days/week.

Figure 3.

Correlation between the annual number of PCI procedures per million population and the gross domestic product per capita in European countries. (A) All PCI procedures. (B) Primary PCI procedures.

Mortality

The in-hospital mortality of all consecutive STEMI patients (Table 5) varies between 4.2 and 13.5%, for patients treated by TL between 3.5 and 14%, and for patients treated by primary PCI between 2.7 and 8%.

Table 5.

In-hospital mortality (in %) of acute myocardial infarction

| Country | All STEMIs | STEMIs treated by primary PCI | STEMIs treated by thrombolysis | All AMIs (STEMI+non-STEMI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 12 | 5 | 8 | N.A. |

| Belgium | 6.6 | 5.1 | 7 | N.A. |

| Bulgaria | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Croatia | 10 | 5 | 7 | N.A. |

| Czech Republic | 8.6 | 6.7 | N.A. | 6.3 |

| Denmark | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Estonia | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| France | 6.6 | 5.0 | 4.3 | 5.4 |

| Finland | 11.9 | N.A. | N.A. | 11.8 |

| Germany | 6.8 | 5.3 | 7.8 | 6.1 |

| Greece | 8.9 | 3.6 | 5.1 | 7.7 |

| Hungary | 9.1 | 5.7 | 13 | 13.5 |

| Italy | 13.5 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 11.1 |

| Israel | 4.2 | N.A. | N.A. | 2.8 |

| Latvia | 11.7 | 2.3 | 10.1 | 10.9 |

| Lithuania | N.A. | 6 | N.A. | N.A. |

| F.Y.R.Macedonia | N.A. | 4 | 7 | N.A. |

| The Netherlands | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Norway | N.A. | 3.5 | N.A. | 8.5 |

| Poland | 8.5 | 4.2 | 12 | 7.5 |

| Portugal | 7.8 | N.A. | N.A. | 6.0 |

| Romania | 13 | 7 | 8.5 | N.A. |

| Serbia | 9.9 | 3.3 | 9.3 | 10.7 |

| Slovakia | 9.4 | 3.2 | 11.1 | N.A. |

| Slovenia | N.A. | 6.2 | N.A. | N.A. |

| Spain | N.A. | 4 | N.A. | N.A. |

| Sweden | 6.2 | 3.8 | 8.8 | 5.2 |

| Switzerland | 6.2 | 3.6 | 4.5 | 5.0 |

| Turkey | 11 | 8 | 14 | 14 |

| UK | 9 | 3.7 | 7.3 | 8.7 |

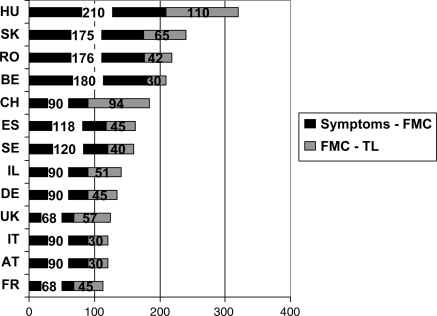

Time delays

The time from symptom onset to the FMC (defined as the time of diagnostic ECG) ranged from 60 to 210 min, FMC-needle time for TL between 30 and 110 min and FMC-balloon time for p-PCI between 60 and 177 min. These FMC-balloon times are given for all primary PCI procedures, irrespective of whether the patient underwent interhospital transfer or was directly admitted to the PCI hospital (Table 6; Figures 4and5).

Table 6.

Median time delays (in min) in reperfusion therapy

| Country | Symptoms onset: first medical contact (FMC) time | FMC-thrombolysis (needle) time | FMC-primary PCI (balloon) time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 90 | 30 | 115 |

| Belgium | 180 | 30 | 60 |

| Bulgaria | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Croatia | 140 | N.A. | 120 |

| Czech Republic | 150 | N.A. | 120 |

| Denmark | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Estonia | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| France | 68 | 57 | 170 |

| Finland | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Germany | 100 | 45 | 120 |

| Greece | 180 | N.A. | 95 |

| Hungary | 210 | 110 | 115 |

| Italy | 117 | 30 | 88 |

| Israel | 90 | 73 | 92 |

| Latvia | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Lithuania | 60 | N.A. | 120 |

| F.Y.R.Macedonia | 147 | N.A. | 154 |

| The Netherlands | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Norway | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Poland | 118 | N.A. | 124 |

| Portugal | N.A. | 60 | 86 |

| Romania | 176 | 42 | N.A. |

| Serbia | 60 | N.A. | 177 |

| Slovakia | 175 | 65 | 110 |

| Slovenia | 97 | N.A. | 134 |

| Spain | 118 | 45 | 97 |

| Sweden | 120 | 40 | 69 |

| Switzerland | 90 | 94 | 135 |

| Turkey | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| UK | 68 | 55 | 118 |

In some countries, the FMC time is not reported and instead, the door-needle or door-balloon times are in the table.

Figure 4.

Time delays in patients treated by thrombolysis: ‘symptom onset—first medical contact’ and ‘first medical contact—start of thrombolysis’ time.

Figure 5.

Time delays in patients treated by p-PCI: ‘symptom onset—first medical contact’ and ‘first medical contact—balloon’ time.

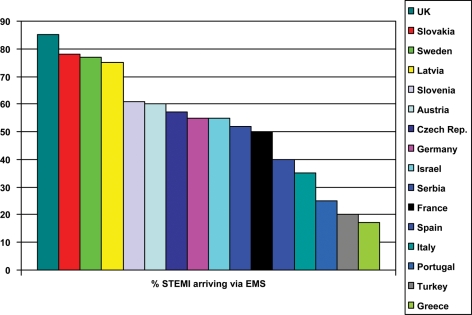

STEMI initial presentation

Only approximately half of the patients arrive at the hospital via an EMS ambulance. This proportion varies considerably between countries: from 17% (Greece) to 85% (UK) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Percentage of STEMI patients arriving to the first hospital via EMS services. In the UK, Norway, Switzerland, and Sweden, physicians are only in ambulance helicopters, paramedics are in ambulance cars. In all other countries, physicians are in most or all EMS ambulances (cars and helicopters).

Discussion

Geographic differences, heterogenity of care

Primary PCI appears to be now the dominant treatment of STEMI in the majority of countries: Scandinavia (Norway, Denmark, Sweden, and Finland), Central Europe (Czech Republic, Slovenia, Poland, Hungary, Austria, and Croatia), West Europe (Germany, Belgium, France, Switzerland, and the Netherlands), Italy, and Israel. Several countries have the infrastructure available, but do not use it sufficiently to treat most of their AMI patients—this holds true especially for the South Europe (Greece, Bulgaria, Portugal, Spain, and Turkey) and for the UK and Slovakia (however, national programs for p-PCI implementation have already started in these latter two countries). The described ‘North-South gradient’ in primary PCI services is typically seen in Italy: the Northern part of Italy has p-PCI rates similar to Central or West Europe, while the Southern part of Italy has rates similar to Greece or Turkey. Unfortunately, no or few data have been obtained from Ireland, Iceland, East Europe (Belarus, Ukraina, Russia, Moldova, Bosnia i Herzegovina, FYROM, Albania, and Georgia) and from the Mediterranean non-European countries (ESC members).

The heterogeneity of care is known from international registries—e.g. the GRACE registry showed that the care-seeking behaviour in patients with acute coronary disease differs among countries or continents.28

Annual incidence of the hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction

The annual incidence of hospital admission for any AMI varied considerably, as was the case for the incidence of STEMI alone. Those countries with the most precise data (e.g. covering 100% of the population either in the whole country or in selected regions/counties—see Table 1) reported the incidence close to the overall mean numbers (ca. 1900 for all AMIs and ca. 800 for STEMIs). In other words, the annual incidence of ca. 1900 hospital admissions for any AMI per year per million population seems to be typical for the European population. This can be used for planning infrastructure because most of these patients will need coronary angiography and subsequent PCI or CABG during their hospital stay.

Reperfusion strategy use

It is of note that primary PCI is already today the leading reperfusion strategy in most European countries. Several countries can serve as evidence that p-PCI may be able to be offered to as many as 70–90% of all STEMI patients in the whole country. An increased use of primary PCI as the preferred reperfusion therapy is identified by this data when compared with the second Euro Heart Survey on Acute Coronary Syndromes (EHS-ACS-II).29 Results of our study challenge the traditional opinion that TL is the strategy more suitable for widespread application. In some countries, the opposite appears to be true: reperfusion as a whole is offered to less of the STEMI population in those countries using TL as the dominant strategy. This may be related to the many contraindications for thrombolytic therapy and also to the fear of using TL in patients over 75 years of age, who present a significant proportion of all STEMI patients today (e.g. 31% of all hospitalized AMI patients in the Netherlands30). Thus p-PCI, despite its logistic complexity, appears to offer broader population reach in some countries.

The population need for primary PCI services

The number of primary PCI procedures per million per year in these countries, covering their population needs, varies between ca. 600 and 900 per million. In these countries, one PCI centre is serving a population of ca. 0.3–0.8 million per centre. These numbers might serve as a reference for planning the infrastructure.

Mortality

The data on mortality between countries cannot be directly compared due to the different methodology of the national registries or surveys. The Czech Republic can serve as an example of these methodological limitations: the in-hospital mortality after p-PCI in the national PCI registry reported by the cardiologists was 3.5%, while after matching the data with the national deaths registry this number rose to 6.7%. This can be explained by the fact that cardiologists are frequently entering the registry data immediately after the procedure, when the patient is subsequently moved from the interventional cardiology unit to another unit (long-term facility, local community hospital, cardiac surgery, long-term rehabilitation unit, etc.) and thus they do not reflect the true (total) hospital outcome.

As with all registries, these data must be interpreted with great caution. The demographic features of patients treated by p-PCI may well be different from those treated by TL. In the National Infact Angioplasty Project (NIAP) study in the UK, for example, the patients treated by p-PCI were younger than those treated by TL, suggesting a tendency to use p-PCI in fitter patients who have a lower predicted mortality regardless of treatment strategy. Conversely, it is also possible that some of the difference is due to the ‘real world’ inclusion of higher risk patients, for whom the differential benefits of PCI might be greater. The highest risk patients (elderly, cardiogenic shock, polymorbid, etc.) are usually excluded from the randomized trials and p-PCI is certainly an optimal treatment for this high-risk group, while TL is associated with high mortality or high complication rates in cardiogenic shock or elderly patients.

The lack of information about the baseline characteristics of individual patients in our study and subsequently the inability to statistically compensate for probable differences between the two reperfusion groups prohibit us from making any adjusted comparison of mortality outcome between p-PCI and TL. However, properly analysed consecutive STEMI patients from a whole European country (Sweden) showed that p-PCI was superior to TL with lower 30 day and 1 year mortality.31,32

Time delays

If 30 min (as an expected minimal time to achieve pharmacologic reperfusion) are arbitrarily added to FMC-needle time, then TL is only minimally faster in opening the coronary artery when compared with p-PCI in our study. The importance of time delays can be easily demonstrated on the situation in France: the time delays in reperfused patients are short and thus the mortality is low. Furthermore, the difference (125 min; Table 5) between the short TL-related delay and the long PCI-related delay causes no significant difference in mortality between the two treatment strategies in this country.33 In other words, p-PCI is superior to TL only when the time difference between these two strategies is below 2 h. We are fully aware that this survey cannot directly compare TL and p-PCI. Both treatments can certainly be offered more expeditiously than was shown in this study. This should be one of the main goals for future improvements.

Primary PCI volume per centre and per operator

Primary PCI volume per centre and per operator may influence the outcomes, especially of STEMI patients, where the complexity of care is more important compared with elective PCI. Unfortunately, this study was not designed to collect such data. The experience from countries, using primary PCI for vast majority of their STEMI patients, shows that a population between 0.3 and 1.1 million per one primary PCI (i.e. non-stop, 24/7) centre results in ca. 200–800 primary PCI procedures/year/centre. This may be considered optimal. Population per centre <0.3 million results in low numbers of STEMI and thus the experience of the team may not be sufficient. A population significantly greater than one million results in ‘overload’ of the centre by too many infarcts (of course only if all infarcts from that region are admitted to this centre). The PCI volume per operator is probably less important than PCI volume per centre, as there are very few low volume operators in the high volume centres. The optimal case load may be anywhere between 50–100 primary PCIs/operator/year.

Reimbursement

In most European countries (Austria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Israel, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, and Switzerland), the reimbursement systems supports primary PCI—i.e. the PCI hospital is reimbursed adequately, the non-PCI hospital in general does not lose money by sending patients for primary PCI and Emergency Medical Services (EMS) transfers are reimbursed. In some countries, PCI centres receive reimbursement for primary PCIs, but the small hospitals lose money when STEMI patients are admitted initially to PCI centres (Belgium, Bulgaria, Spain, Turkey, and UK) or interhospital transfer is not appropriately reimbursed (Belgium and Bulgaria). In only one country (Romania), PCIs (any) are not adequately reimbursed in general (low limits on numbers of centres and procedures).

Barriers for the implementation of primary PCI in Europe

Reimbursement is only rarely a real problem (see above). EMS interhospital transport is not supported by adequate reimbursement in some countries, and in smaller districts only a single EMS ambulance is in service during the off-hours and cannot go outside this district. Low staffing levels (lack of interventional cardiologists and/or nurses and other support staff) prevent many smaller PCI hospitals running a non-stop (24/7) primary PCI services. A conservative attitude of internists and even some noninvasive cardiologists, who still prefer to use TL instead of sending their patients to other cardiologists, is the most frequently quoted barrier, along with the insufficient motivation of interventional cardiologists and/or nurses to run the non-stop (24/7) services even when the staffing is sufficient (they are often not paid adequately for this activity). The use of helicopters for short distance transfers actually prolongs the delays and should in general be avoided; helicopter transfer is extremely useful for patients with long distance transfers but is expensive. In several countries (Austria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Norway, and Sweden), the good cooperation between the national society of cardiology, government, and insurance companies (health care funds) significantly contributed to the development of p-PCI services.

This survey suggests that medical and non-medical staff are the main barriers for wider p-PCI implementation: with reasons ranging from low staffing levels (lack of interventional cardiologists and/or nurses and other staff groups) through to the conservative attitude of many physicians and to the insufficient motivation of interventional cardiologists and/or nurses to run demanding non-stop (24/7) services. In some countries, the lack of a systematic training program has resulted in a lack of interventional cardiologists and foreign cardiologists have been invited to work there in order to fill this gap. An inappropriate reimbursement system is the limitation of p-PCI only in a few countries. Some of these problems might be overcome by organizing cooperating networks of PCI hospitals in close vicinity and organized by the local ambulance system (EMS) as shown from the VIENNA STEMI network.34 The formation of local networks might help to reach the goal.35

Limitations of this analysis

While data from 30 countries were included in this analysis, the number of centres that participated in some of the national registries or surveys may not be representative of the countries’ total populations. In addition, data were not gathered during the same period of time (data from countries are based on 2005, 2006, or 2007 registries or surveys depending on what was available in each country at the time of this manuscript preparation). Furthermore, different inclusion criteria to national registries and surveys may lead to selection bias in the patient population. This manuscript cannot objectively compare p-PCI vs. TL. It is possible that hospitals using primary PCI have better resource allocation and organization that allows for better overall management of all aspects of AMI, e.g. staffing of these centres may play an important role. Furthermore, we did not have individual patient level data and it may well be that the patients treated by p-PCI and TL are not matched (e.g. p-PCI patients might be younger than the lytic cohort) and thus caution is needed in making such non-randomized comparisons. The presented data are unvalidated, derived from national registries or surveys that might not have identified all patients with AMI or STEMI. The various registries used here differ from each other in their methodology, this being the major limitation that led us to the decision not to use sophisticated statistics in this manuscript.

Due to the facts that this is a retrospective analysis of multiple national registries, there is a lack of rigour in defining the same entry criteria to these variable registries. Furthermore, the data about all hospital admissions (including non-PCI hospitals) were available only from 16 countries. In the remaining 13 countries, data were limited mostly to PCI centres (plus partial information about admissions to non-PCI hospitals).

However, despite these limitations, we believe that these data are the best available and have clear clinical relevance.

Conclusions

The annual incidence of hospital admission for AMI in Europe is circa 1900 patients per million population with an incidence of STEMI of about 800 per million. A nationwide primary PCI strategy for STEMI results in more patients being offered reperfusion therapy. North, West, and Central Europe have already well-developed primary PCI services, offering primary PCI treatment to 60–90% of all STEMI patients. South Europe and the Balkans are still predominantly using TL—associated with this is a higher proportion of patients left without reperfusion treatment. Countries performing annually >600 primary PCIs per million population and having a mean population per one p-PCI centre <750 000 are able to meet the needs of all their STEMI patients. Countries in which (nearly) all existing PCI centres offer 24/7 p-PCI services appear to exhibit the best results. Overall, there is a substantial heterogenity of practice in Europe and there are many opportunities to improve the care.

Funding

The preparation of this manuscript was supported by the European Association for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions, EuroPCR, Eucomed, and partly (P.W.) also by the Charles University Research Project MSM0021620817. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the project MSM0021620817.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Appendix

Appendix: the full list of contributors

Austria(VIENNA STEMI Registry, Austrian Acute PCI Registry, Austrian Heart Catheter Registry, and Death Statistics Austria): K.H., F.W.

Belgium (Belgian STEMI registry, Belgian Working Group Interventional Cardiology registry): M.C., Victor Legrand.

Bulgaria: S.D., Vasil Velchev.

Croatia (Croatian Cardiac Society, WG for Acute Coronary Syndromes, Hospital PCI registries, Zagreb Registry of Acute Myocardial Infarction, Croatian Institute for Public Health): D.M., Vjeran Nikolić Heiztler, Zdravko Babić, Mijo Bergovec, Vlasta Hrabak Žerjavić, Verica Kralj.

Czech Republic (CZECH registry, National PCI registry—NRKI): P.W., P.K., Michael Zelizko, Michael Aschermann, Petr Jansky, Frantisek Tousek, Frantisek Holm.

Denmark: S.D.K., Anders Junker.

Estonia: Toomas Marandi.

Finland: J.H.

France: J.F., N.D., Martine Gilard, Didier Blanchard.

Germany (Deutsches Herzinfarkt-Register, Herzbericht 2007): U.Z., Volker Schaechinger, Anselm Gitt, Michael Boehm.

Greece (HELIOS registry, Hellenic Heart PCI registry): G.A., Georgios Papaioannou.

Hungary (Database of the National Health Insurance Fund, National primary PCI registry): B.M., David Becker.

Israel (ACSIS registry): Alexander Battler, Basil Lewis, Shlomo Behar.

Italy (SICI GISE PCI registry, LOMBARDIMA registry, BLITZ 3 survey, IN-ACS Outcome registry, Italian National Health Service, Veneto region registry, Ministero del Lavoro, Salute e Politiche Sociali, Istituto Superiore di Sanità): S.S., M.T.

Latvia (Latvian registry of ACS): Andrejs Erglis.

Lithuania: Ramunas Navickas.

F.Y.R. Macedonia: M.K.

The Netherlands: Karel T. Koch, Willem J. ter Burg.

Norway: L.A.

Poland (PL-ACS Registry, WG on Cardiovascular Interventions registry): G.O., A.W., Lech Polonski.

Portugal: J.M.

Romania (RO-STEMI registry): Dan Deleanu, Gabriel Tatu-Chitoiu.

Serbia (National ACS registry): M.O., Z.V.

Slovakia (SLOVAKS registry): M.S., Anna Baráková, Peter Hlava, Ján Murín, Gabriel Kamenský, Gabriela Kaliská.

Slovenia (National survey 2007, Ljubljana registry): M.N.

Spain: J.A.B., A.B., J.M.F., Agustin Albarrang, Felipe Hernandez.

Sweden (RIKS-HIA/Swedeheart registry): U.S.

Switzerland (Swiss PCI registry, AMIS Plus registry): P.E., D.R., Stephan Windecker, Eric Eeckhout.

Turkey (TUMAR registry): Omer Kozan, Rasim Enar.

UK (MINAP registry, BCIS registry): M.B., P.L., John Birkhead.

References

- 1.Zijlstra F, de Boer MJ, Hoorntje JC, Reiffers S, Reiber JH, Suryapranata H. A comparison of immediate coronary angioplasty with intravenous streptokinase in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:680–684. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199303113281002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vermeer F, Oude Ophuis AJ, van den Berg EJ, Brunninkhuis LG, Werter CJ, Boehmer AG, Lousberg AH, Dassen WR, Bär FW. Prospective randomised comparison between thrombolysis, rescue PTCA, and primary PTCA in patients with extensive myocardial infarction admitted to a hospital without PTCA facilities: a safety and feasibility study. Heart. 1999;82:426–431. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.4.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Widimský P, Groch L, Zelízko M, Aschermann M, Bednár F, Suryapranata H. Multicenter randomized trial comparing transport to primary angioplasty vs immediate thrombolysis vs combined strategy for patients with acute myocardial infarction presenting to a community hospital without a catheterization laboratory. The PRAGUE study. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:823–831. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Widimsky P, Budesinsky T, Vorac D, Groch L, Zelizko M, Aschermann M, Branny M, St'asek J, Formanek P ‘PRAGUE’ Study Group Investigators. Long distance transport for primary angioplasty vs. immediate thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction. Final results of the randomized national multicentre trial—PRAGUE-2. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:94–104. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen HR, Nielsen TT, Rasmussen K, Thuesen L, Kelbaek H, Thayssen P, Abilgaard U, Pedersen F, Madsen JK, Grande P, Villadsen AB, Krusell LR, Haghfelt T, Lomholt P, Husted SE, Vigholt E, Kjaergard HK, Mortensen LS. A comparison of coronary angioplasty with fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines C. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomized trials. Lancet. 2003;361:13–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van de Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Crea F, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fox K, Huber K, Kastrati A, Rosengren A, Steg PG, Tubaro M, Verheugt F, Weidinger F, Weis M, Vahanian A, Camm J, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Zamorano JL, Silber S, Aguirre FV, Al-Attar N, Alegria E, Andreotti F, Benzer W, Breithardt O, Danchin N, Di Mario C, Dudek D, Gulba D, Halvorsen S, Kaufmann P, Kornowski R, Lip GY, Rutten F ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force on the Management of ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2909–2945. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silber S, Albertsson P, Aviles FF, Camici PG, Colombo A, Hamm C, Jorgensen E, Marco J, Nordrehaug JE, Ruzyllo W, Urban P, Stone GW, Wijns W. Guidelines for percutaneous coronary interventions—the task force for percutaneous coronary interventions of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:804–847. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tadel Kocjancic S, Zorman S, Jazbec A, Gorjup V, Zorman D, Noc M. Effectiveness of primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction from a 5-year single-center experience. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.07.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merkely B, Becker D, Szabó GY. Status and development of the Hungarian interventional cardiology. JACC Hungarian Edition. 2006;1:144–148. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Studencan M, Barakova A, Hlava P, Murin J, Kamensky G. Slovak register of Acute Coronary Syndromes (SLOVAKS)—analysis of data from 2007. Cardiology. 2008;17:177–188. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Chiara A, Chiarella F, Savonitto S, Lucci D, Bolognese L, De Servi S, Greco C, Boccanelli A, Zonzin P, Coccolini S, Maggioni AP. Epidemiology of acute myocardial infarction in the Italian CCU network—The BLITZ Study. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1616–1629. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Chiara A, Fresco C, Savonitto S, Greco C, Lucci D, Gonzini L, Mafrici A, Ottani F, Bolognese L, De Servi S, Boccanelli A, Maggioni AP, Chiarella F BLITZ-2 Investigators. Epidemiology of non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes in the Italian cardiology network: the BLITZ-2 study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:393–405. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrikopoulos G, Pipilis A, Goudevenos J, Tzeis S, Kartalis A, Oikonomou K, Karvounis H, Mantas J, Kyrpizidis C, Gotsis A, Paschidi M, Tsaknakis T, Pyrgakis V, Manolis AS, Boudoulas H, Vardas P, Stefanadis C, Lekakis J On behalf of the HELIOS study investigators. Epidemiological characteristics, management and early outcome of acute myocardial infarction in Greece. The HELlenic Infarction Observation Study. Hell J Cardiol. 2007;48:325–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrikopoulos GK, Tzeis SE, Pipilis AG, Richter DJ, Kappos KG, Stefanadis CI, Toutouzas PK, Chimonas ET from the investigators of the Hellenic Study of AMI. Younger age potentiates post myocardial infarction survival disadvantage of women. Int J Cardiol. 2006;108:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pipilis A, Andrikopoulos G, Lekakis J, Kalantzi K, Kitsiou A, Toli K, Floros D, Karalis J, Dragomanovits S, Kalogeropoulos P, Synetos A, Koutsogiannis N, Stougiannos P, Antonakoudis H, Goudevenos J on behalf of the HELIOS group. Outcome of patients with acute myocardial infarction admitted in hospitals with or without catheterization laboratory: results from the HELIOS registry. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehab. 2009;16:85–90. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32831e954e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marrugat J, Elosua R, Marti H. Epidemiology of ischaemic heart disease in Spain: estimation of the number of cases and trends from 1997 to 2005. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2002;55:337–346. doi: 10.1016/s0300-8932(02)76611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salomaa V, Ketonen M, Koukkunen H, Immonen-Räihä P, Jerkkola T, Kärjä-Koskenkari P, Mähönen M, Niemelä M, Kuulasmaa K, Palomäki P, Mustonen J, Arstila M, Vuorenmaa T, Lehtonen A, Lehto S, Miettinen H, Torppa J, Tuomilehto J, Kesäniemi YA, Pyörälä K. Decline in out-of-hospital coronary heart disease deaths has contributed the main part to the overall decline in coronary heart disease mortality rates among persons 35 to 64 years of age in Finland: the FINAMI study. Circulation. 2003;108:691–696. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000083720.35869.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Widimsky P, Zelizko M, Jansky P, Tousek F, Holm F Aschermann M on behalf of the CZECH investigators. The incidence, treatment strategies and outcomes of acute coronary syndromes in the ‘reperfusion network’ of different hospital types in the Czech Republic: results of the CZech Evaluation of acute Coronary syndromes in Hospitalized patients (CZECH) Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2007;119:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pajunen P, Koukkunen H, Ketonen M, Jerkkola T, Immonen-Räihä P, Kärjä-Koskenkari P, Mähönen M, Niemelä M, Kuulasmaa K, Palomäki P, Mustonen J, Lehtonen A, Arstila M, Vuorenmaa T, Lehto S, Miettinen H, Torppa J, Tuomilehto J, Kesäniemi YA, Pyörälä K, Salomaa V. The validity of the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register and Causes of Death Register data on coronary heart disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005;12:132–137. doi: 10.1097/00149831-200504000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polewczyk A, Janion M, Gąsior M, Gierlotka M. Myocardial infarction in the elderly. Clinical and therapeutic differences. Kardiol Pol. 2008;66:166–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gąsior M, Poloński L, Gierlotka M, Zębik T, Kalarus Z, Zembala M, Opolski G. Do patients with acute coronary syndromes admitted to non-PCI hospitals have worse short-term outcome? Results from the PL-ACS Registry. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:565. (abstract supplement) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poloński L, Gierlotka M, Gąsior M, Witkowski A, Gil R, Kalarus Z, Zembala M, Opolski G. Effect of age on treatment strategy and in-hospital mortality of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Analysis form PL-ACS Registry. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:776–777. (abstract supplement) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gierlotka M, Gąsior M, Opolski G, Lekston A, Filipiak K, Janion M, Tendera M, Rużyłło W, Zembala M, Poloński L. 2-year mortality after NSTEMI and STEMI in clinical practice—results from PL-ACS Registry. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:747. (abstract supplement) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poloński L, Gąsior M, Gierlotka M, Buszman P, Wilczek K, Kalarus Z, Trusz-Gluza M, Gąsior Z, Zembala M, Tendera M. Temporal trends in treatment and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in clinical practice. Results from PL-ACS Registry in Silesia. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:746–747. abstract supplement) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dobric M, Ostojic M, Nedeljkovic M, Vukcevic V, Stankovic G, Stojkovic S, Veleslic B, Orlic D, Vasiljevic Z, Lazic B. Treatment of acute ST elevation myocardial infarction with primary percutaneous coronary intervention in Department of Cardiology, Clinical Centre of Serbia, Belgrade: movement and treatment of patients from the onset of chest pain till the attempt of reopening the infarct-related artery. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2007;135:521–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasiljevic Z, Stojanovic B, Kocev N, Stefanovic B, Mrdovic I, Ostojic M, Krotin M, Putnikovic B, Dimkovic S, Despotovic N. Hospital mortality trend analysis of patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction in the Belgrade area coronary care units. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2008;136(Suppl. 2):84–96. doi: 10.2298/sarh08s2084v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldberg RJ, Spencer FA, Fox KAA, Brieger D, Steg PG, Gurfinkel E, Dedrick R, Gore JM. Prehospital delay in patients with acute coronary syndromes (from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events [GRACE]) Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:598–603. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandelzweig L, Battler A, Boyko V, Bueno H, Danchin N, Filippatos G, Gitt A, Hasdai D, Hasin Y, Marrugat J, Van de Werf F, Wallentin L, Behar S. The second Euro Heart Survey on acute coronary syndromes: characteristics, treatment, and outcome of patients with ACS in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin in 2004. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2285–2293. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koek HL, van Dis SJ, Peters RJG, Bots ML. Hart en vaatziekten in Nederland 2005. den Haag: Nederlandse Hartstichting; 2005. Hart- en vaatziekten in Nederland; pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stenestrand U, Lindbäck J, Wallentin L for the RIKS-HIA group. Long-term outcome of primary percutaneous coronary intervention vs prehospital and in-hospital thrombolysis for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2006;296:1749–1756. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.14.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Björklund E, Lindahl B, Stenestrand U, Swahn E, Dellborg M, Pehrsson K, Van De Werf F, Wallentin L Swedish ASSENT-2; RIKS-HIA Investigators. Outcome of ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with thrombolysis in the unselected population is vastly different from samples of eligible patients in a large-scale clinical trial. Am Heart J. 2004;148:566–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Danchin N, Coste P, Ferrières J, Steg PG, Cottin Y, Blanchard D, Belle L, Ritz B, Kirkorian G, Angioi M, Sans P, Charbonnier B, Eltchaninoff H, Guéret P, Khalife K, Asseman P, Puel J, Goldstein P, Cambou JP, Simon T for the FAST-MI Investigators. Comparison of Thrombolysis Followed by Broad Use of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention With Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for ST-Segment-Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction Data From the French Registry on Acute ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (FAST-MI) Circulation. 2008;118:268–276. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.762765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalla K, Christ G, Karnik R, Malzer R, Norman G, Prachar H, Schreiber W, Unger G, Glogar HD, Kaff A, Laggner AN, Maurer G, Mlczoch J, Slany J, Weber HS, Huber K Vienna STEMI Registry Group. Implementation of guidelines improves the standard of care: the Viennese registry on reperfusion strategies in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (Vienna STEMI registry) Circulation. 2006;113:2398–2405. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.586198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fox KAA, Huber K. A European perspective on improving acute systems of care in STEMI: we know what to do, but how can we do it? Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:708–714. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mühlberger V, Pachinger O. Herzkathetereingriffe in Österreich im Jahr 2007 (mit Audit 2004–2008) J Kardiol. 2009;16:86–103. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suessenbacher A, Doerler J, Alber H, Altenberger J, Christ G, Globits S, Huber K, Karnik R, Norman G, Zenker G, Pachinger O, Weidinger F. Gender-related outcome following percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: data from the Asutrian Acute PCI Registry. Eurointervention. 2008;4:271–276. doi: 10.4244/eijv4i2a47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/CLINICAL-STANDARDS/ORGANISATION/PARTNERSHIP/Pages/MINAP-.aspx .

- 39. http://www.bcis.org.uk/resources/audit .

- 40. http://www.ccad.org.uk/

- 41.Brocco S, Fedeli U, Schievano E, Milan G, Avossa F, Visentin C, Alba N, Olivari Z, Di Pede F, Spolaore P. Effect of the new diagnostic criteria for ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction on 4-year hospitalization: an analysis of hospital discharge records in the Veneto Region. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2006;7:45–50. doi: 10.2459/01.JCM.0000199787.45940.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Proceedings and Syllabus of the Belgrade Summit of Interventional Cardiologists—BASICS +; 5–8 April 2009; Belgrade. pp. p162–164. ISBN 978-86-7117-246-2. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferreira J, Monteiro P, Mimoso J. National Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes: results of the hospital phase in 2002. Rev Port Cardiol. 2004;23:1251–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. http://www.spc.pt/cncdc/resultadoscncdc_v2.pdf .

- 45.Baz JA, Pinar E, Albarrán A, Mauri J Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization Interventional Cardiology. Spanish Cardiac Catheterization and Coronary Intervention Registry. 17th official report of the Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology (1990–2007) Rev Esp Cardiol. 2008;61:1298–1314. doi: 10.1016/s1885-5857(09)60057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeymer U. Deutsches Herzinfarkt-Register. Presented at the Hotline 1 of the Annual Meeting of the German Cardiac Society; 16 April 2009; Mannheim. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruckenberger E. Hannover: 2008. Herzbericht 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jeger R, Radovanovic D, Hunziker P, Pfisterer M, Stauffer J-C, Erne P, Urban P. Ten-year trends in the incidence and treatment of cardiogenic shock. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:618–626. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schoenenberger AW, Radovanovic D, Stauffer J-C, Windecker S, Urban P, Eberli FR, Stuck AE, Gutzwiller F, Erne P for the Acute Myocardial Infarction in Switzerland Plus Investigators. Age-related differences in the use of guideline-recommended medical and interventional therapies for acute coronary syndromes: a cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:510–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Radovanovic D, Erne P, Urban P, Bertel O, Rickli H, Gaspoz J-M. Gender differences in management and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Results on 20 290 patients from the AMIS Plus registry. Heart. 2007;93:1369–1375. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.106781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maeder M, Stauffer J-C, Windecker S, Pedrazzini G, Kaiser C, Roffi M, Rickli H on behalf of the Working Group ‘Interventional Cardiology Acute Coronary Syndrome’. Interventional cardiology in Switzerland 2006. Kardiovaskuläre Medizin. 2008;11:187–195. [Google Scholar]