Abstract

Associations between maternal sensitivity to infant distress and non-distress and infant social-emotional adjustment were examined in a subset of dyads from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care (N = 376). Mothers reported on infant temperament at 1 and 6 months postpartum, and maternal sensitivity to distress and non-distress were observed at 6 months. Child behavior problems, social competence, and affect dysregulation were measured at 24 and 36 months. Maternal sensitivity to distress but not to non-distress was related to fewer behavioral problems and higher social competence. In addition, for temperamentally reactive infants, maternal sensitivity to distress was associated with less affect dysregulation. Sensitivity to non-distress only prevented affect dysregulation if sensitivity to distress was also high.

There is considerable evidence that infants develop healthy relationships, behaviors, and social-emotional skills in the context of early sensitive interactions with their mothers (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters & Wall, 1978; van den Boom, 1994, 1995). Sensitive responses to infant distress may be of more developmental significance in relation to social-emotional outcomes than sensitivity to non-distress. How parents respond to children's negative emotions may teach infants valuable lessons about their own emotional states and what they can expect from social partners. Two studies support the primacy of sensitivity to negative emotions over and above other dimensions of maternal sensitivity in relation to infant-mother attachment security (Del Carmen, Pederson, Huffman & Bryan, 1993; McElwain & Booth-LaForce, 2006). It is still not known, however, whether sensitivity to infant distress predicts other aspects of early social-emotional adjustment independent of sensitivity to non-distress. Furthermore, the possibility that maternal sensitivity to infant distress is particularly important to the adaptive development of temperamentally reactive infants who are prone to more frequent and intense negative emotions remains to be examined. Thus the goals of the present study were to: 1) examine the associations between maternal sensitivity both to infant distress and to non-distress and indices of early social-emotional development (behavior problems, social competence, and affect dysregulation); and 2) determine if these associations vary based on infant temperament.

The Meaning and Measurement of Maternal Sensitivity

Maternal sensitivity refers to the quality with which mothers respond to their infants’ cues in a timely and appropriate manner. Sensitive mothers respond to cues reasonably quickly, establishing a clear contingency between their infants’ cues and their responses. Moreover, their responses are well matched to their infants’ cues, the developmental level of their infant, and the demands of the current context. In most published studies, single scores representing global ratings of sensitivity in response to diverse infant cues are used as indices of the quality of maternal responsiveness (e.g., Ainsworth et al., 1978). Even when sensitivity is rated separately in responses to specific types of infant cues, the ratings tend to be aggregated into larger composite variables (Clarke, Hyde, Essex, & Klein, 1997; Pederson & Moran, 1995; van den Boom, 1994). The underlying assumption appears to be that mothers who respond sensitively to one type of infant cue respond sensitively to other types as well, and that sensitivity in general, rather than its specific dimensions, is related to important child outcomes.

Recently, there has been a call for greater specification of the dimensions of sensitivity and the contexts in which they are rated. For example, some authors have noted that, theoretically, sensitivity to distress or in response to bids for safety and protection should be more predictive of attachment security than global measures of sensitivity because attachment relationships serve the purpose of protection (Goldberg, Grusec, & Jenkins, 1999; Thompson, 1997). Consistent with this view, when multiple measures of sensitivity have been used, sensitivity to distress has emerged as the only significant predictor of attachment security (Del Carmen et al., 1993; McElwain & Booth-LaForce, 2006). Further support for the usefulness of examining specific aspects of sensitivity comes from the work of Tamis-LeMonda, Bornstein, Baumwell, and Damast (1996) who reported that maternal responsiveness to infant vocalizations was linked to infant language ability, whereas responsiveness to infant play behavior was linked to infant symbolic play behavior. They concluded that “maternal responsiveness can be profitably categorized into subtypes that relate to domains of child outcomes in specialized ways” (p. 173). In the present study, we propose that sensitivity to infant distress cues will be more predictive of early social-emotional adjustment than will sensitivity to non-distress cues.

Associations between Sensitivity to Distress and Social-Emotional Outcomes

Because situations involving negative emotions are highly salient, parents’ responses to children's negative emotions are likely to have important developmental implications (Eisenberg, Cumberland & Spinrad, 1998; Thompson, 1994). Sensitive responses to negative emotions (i.e., scaffolding self-soothing by providing security objects, fostering attention shifting by providing something appealing to look at, or modeling and encouraging adaptive problem-oriented responses) may help infants learn to self-regulate. Over time, infants’ supported and independent use of regulatory strategies is reinforced by the accompanying reduction in arousal and positive reinforcement from mothers. As a consequence, infants are able to develop a sense of efficacy in their ability to self-regulate (Bell & Ainsworth, 1972) and perceive the expression and sharing of negative emotions as acceptable rather than problematic (Stern, 1985). Furthermore, sensitive responses to bids for safety and protection contribute to a positive sense of self and others, elements of a secure working model (Bowlby, 1973), which in turn facilitates social competence and positive relations with others (Bohlin, Hagekull, & Rydell, 2000).

In contrast, insensitive responses such as rejection, dismissing, or ignoring negative emotions are likely to teach children to minimize, mask, or over-regulate negative emotions rather than express them or regulate them in an adaptive fashion (Cassidy, 1994). Calkins (1994) proposed that mothers’ insensitive responses to infant distress can contribute to escalated distress in the moment, negative beliefs and cognitions about the social environment, and a maladaptive regulatory style. Each of these may ultimately lead to difficulties with peer interactions as evidenced by aggression or social withdrawal. This conceptualization is consistent with Bowlby's (1980) view that infants develop expectations as to whether or not they can expect their own emotional needs to be met, which in turn influences how they process and respond to emotional stimuli in other relationships. That is, a history of insensitive responses to negative emotions is predicted to promote personal distress and self-focus during conflicts with parents, other caregivers, and peers, which in turn undermine feelings of empathy and subsequent prosocial behavior (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998). Infants whose negative emotions are not attended to sensitively may also struggle to understand the meaning and causes of negative emotions (Thompson, 1994), further reducing their ability to respond appropriately to others in social settings (Denham et al., 2003).

Consistent with this view, prior research has shown that sensitive maternal behaviors observed during emotionally arousing tasks in infancy (e.g., re-engagement following the still-face, receiving immunizations, and goal blocking and novelty tasks) are related to infants’ adaptive emotion regulation and the absence of behavioral problems (Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2004; 2006; Crockenberg, Leerkes, & Barrig, 2008; Jahromi & Stifter, 2007; Moore & Calkins, 2004). Because sensitivity to distress and non-distress were not rated separately in these studies, it is unclear if sensitivity to all infant cues in an emotionally arousing context or sensitivity specifically in response to distress cues accounted for these associations.

Research with older children suggests the importance of sensitive responses to negative emotions. Children whose parents report that they actively encourage the expression of emotion and help them develop strategies to cope with their emotions are more emotionally expressive, show better physiological and behavioral regulation, and exhibit fewer behavior problems (Davidov & Grusec, 2006; Fabes, Poulin, Eisneberg, & Madden-Derdich, 2002; Gottman, Katz, & Hooven, 1996; Spinrad, Stifter, Donelan-McCall, & Turner, 2004). In contrast, children whose emotional displays are responded to punitively appear to mask their negative emotions rather than regulate them (Berlin & Cassidy, 2003; Buck, 1984; Eisenberg & Fabes, 1994; Eisenberg et al., 1999). These results support our conceptualization; however, it remains unclear if sensitivity to negative emotions during infancy predicts these types of child outcomes over and above sensitivity to non-distress.

Association between Sensitivity to Non-Distress and Social Emotional Well-Being

Sensitive responses to infants’ positive cues likely support children's early social-emotional adjustment as well. Sensitive mothers elicit and respond positively to their infants’ smiles and sounds; these responses maintain child positive affect. Frequent experience of positive emotions is as a source of resilience that is linked to psychological well-being in adult samples (Shiota, 2006; Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004). Some evidence suggests positive emotion may operate similarly among young children (Hayden, Klein, Durbin, & Olino, 2006). Further, infants who experience frequent positive affect in their early relationships are expected to develop an approach orientation toward social partners because they view social interaction positively (MacDonald, 1992).

Consistent with this view, a number of studies demonstrate that global measures of sensitivity assessed during free play and other low intensity tasks are linked to children's social emotional adjustment. For example, sensitive mothers were found to have children with few internalizing and externalizing symptoms and high levels of social competence (NICHD ECCRN, 1998), and mothers who provided positive guidance during play have children who used effective regulation strategies in emotionally challenging situations (Calkins & Johnson, 1998; Calkins, Smith, Gill & Johnson, 1998). The present study differs from past work in that maternal sensitivity to infant distress and sensitivity to non-distress were observed in the same situation and were analyzed simultaneously in order to determine if one aspect of sensitivity is more predictive of social-emotional adjustment than the other. In addition, we examined the possibility that maternal sensitivity to non-distress would be positively associated with child outcomes only if mothers were also highly sensitive to distress because these infants receive the message that both positive and negative emotions are valuable and worthy of response.

Moderating Effects of Infant Temperament

Temperamentally reactive infants, sometimes described as “difficult,” are easily and intensely distressed, are hard to soothe, and have trouble adapting to change (Rothbart & Bates, 1998; Thomas & Chess, 1977). Prior research suggests that temperamentally reactive infants are predisposed to the development of poor affect regulation, behavior problems, and problematic peer relations (see Calkins & Degnan, 2006; Rothbart & Bates, 1998 for reviews). In the present study, we view temperament as a factor that may moderate the association between maternal sensitivity to distress and early social-emotional adjustment. Specifically, we anticipate that there will be a stronger association between maternal sensitivity to distress and infant outcomes among temperamentally reactive infants than less reactive infants.

This hypothesis is consistent with Belsky's (1997) differential susceptibility hypothesis which argues that the environment, in this case sensitive parenting, may affect children differently depending on their temperament. In this case, sensitivity to distress may have greater functional significance for temperamentally reactive infants because they are dependent on external aid in regulating their emotions and because they are more likely to be on a developmental trajectory toward maladjustment that will proceed unless disrupted by external influence. Consistent with the differential susceptibility hypothesis, several studies have demonstrated stronger associations between maternal behavior and child outcomes among temperamentally reactive children than among less reactive children (Belsky, Hsieh, & Crnic, 1998; Kochanska, 1995; Kochanska, Aksan, & Carlson, 2005; Park, Belsky, Putnam & Crnic, 1997). In the present study, we test this hypothesis in relation to maternal sensitivity to infant distress as well as sensitivity to non-distress.

The Current Study

The present study examined the following hypotheses: 1) when considered simultaneously, maternal sensitivity to infant distress but not sensitivity to non-distress will be positively associated with children's later social competence and negatively associated with behavior problems and affect dysregulation; 2) sensitivity to non-distress will be positively associated with children's adaptive social-emotional outcomes when mothers are highly sensitive to distress but not when they are low on sensitivity to distress; and 3) the associations between maternal sensitivity to infant distress and early social emotional adjustment will be stronger among highly temperamentally reactive infants than among infants who are less temperamentally reactive. These hypotheses were tested using data from the first wave of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care (NICHD SECC). Several features of this research distinguish it from previous studies. First, both sensitivity to distress and non-distress were rated at 6 months, allowing us to control for sensitivity to non-distress when examining the association between sensitivity to distress and child outcomes. Second, a sufficient proportion of infants in this large national sample did become distressed during home observations of maternal sensitivity to test these hypotheses in a reasonably large sample (n=376). Third, because maternal sensitivity to distress was observed, there is no shared method variance when evaluating associations between sensitivity to distress and mothers’ subsequent ratings of their infants’ social-emotional adjustment. Finally, we control for several relevant factors including socioeconomic status and maternal depression, potential confounds that tend to correlate with both maternal sensitivity and children's early social-emotional adjustment (NICHD ECCRN, 2005). We also control for measures of maternal sensitivity at 24 and 36 months to ensure that observed associations between sensitivity at 6 months and child outcomes are not an artifact of concurrent measures of sensitivity. This is important given evidence of stability in sensitivity over early childhood in this sample (NICHD, 1999).

Methods

Participants

Participants in the NICHD SECC were recruited throughout 1991 from hospitals in 10 locations across the United States (Little Rock, AK; Irvine, CA; Lawrence, KS; Boston, MA; Philadelphia, PA; Pittsburgh, PA; Charlottesville, VA; Morganton, NC; Seattle WA; and Madison, WI). A total of 1364 families enrolled in the SECC (see NICHD ECCRN, 1999, for further details). For the present study, mothers and infants were included only if the infants displayed distress during the 6-month home observation of maternal sensitivity and therefore had data on maternal sensitivity both to distress and to non-distress. This yielded a possible sample of 397 mothers and infants. These mother-infant dyads were compared on demographic factors to dyads in which the infants never became distressed and who therefore had no measure of maternal sensitivity to distress. Dyads in the “distress” subsample were more temperamentally reactive (t [1362]= 2.06, p =.04) and more likely to include a male infant (χ2 [1], N= 1133] = 5.03, p <.05). All other comparisons were nonsignificant.

Of the 397 potential dyads, 21 were missing all outcome variables and were excluded from further analyses. The excluded dyads had lower income (t [367]= −2.02, p=.04) and mothers were more likely to be single (χ2 [6, N=397] = 23.24, p=.001) compared with dyads with data on the outcome variables. Additionally, dyads with all missing outcome variables had mothers who were younger (t [395]= −2.601, p = .01), less likely to be white (χ2[1, N=397]=5.53, p=.02), and less well educated (t[395]= −2.173, p =.03).

In the final sample of 376 mother-infant dyads, mothers were 29 years of age on average (SD= 5.66) and had approximately 14 years of education (SD= 2.50); 81% were European American, 13% African American, and 6% other ethnicities. Additionally, 86% of the mothers had partners living in the home at both 1 and 6 months. Fifty-six percent of the children were male. Finally, the mean family income-to-needs ratio (total family income divided by the poverty level for that family size) for the sample, averaged over 1 and 6 months, was 3.18 (SD= 2.82). Approximately 38% of the sample had an income-to-needs ratio of 2 or less, 44% between 2 and 5, and 18% had income-to-needs ratios greater than 5.

Overview of Data Collection

Data for the present analyses were collected from the time the child was 1 month through 36 months of age. At 1 month, basic demographic information on the child and family was obtained from the mother during a home visit. At 6 months, maternal sensitivity was assessed during a videotaped free play situation in the child's home. Mothers updated demographic information and completed measures of infant temperament and maternal depression at this time. At 24 and 36 months, mothers completed measures of child behavior problems and social competence, and maternal and child behaviors were observed during various interactions.

Measures

Predictor Variables

Maternal Sensitivity

At 6 months, mothers and infants were observed during a 15 minute structured interaction situation in the home. In the first 7-8 minutes the mothers and their infants played with toys of their own choosing. This was immediately followed by a second 7-8 minute session in which the mother-infant dyads were provided with a standard set of toys. Videotapes of the mother-child interaction were shipped to a central site and rated by trained coders who were blind to family characteristics. Videotapes were coded for maternal sensitivity to distress and sensitivity to non-distress using a global 4-point rating scale ranging from 1 (not at all characteristic) to 4 (highly characteristic). Sensitivity to distress represents the promptness and appropriateness of the mother's response to the child's distress, while sensitivity to non-distress represents the promptness and appropriateness of the mother's responses to the child's social gestures, expressions, and signals. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using intraclass correlations (Winer, 1971) and was .83 for sensitivity to distress and .85 for sensitivity to non-distress.

Infant Temperament

At 1 and 6 months, mothers completed an adaptation of the Early Infant Temperament Questionnaire (EITQ; Medoff-Cooper, Carey, & McDevitt, 1993) and the Revised Infant Temperament Questionnaire (ITQ-R; Carey & McDevitt, 1978), respectively, which are measures consisting of infant behaviors (e.g., “My baby is fussy on waking up or going to sleep”). The 1-month questionnaire comprised 38 items (alpha = .67), while the 6-month questionnaire comprised 55 items (alpha = .81). Mothers were asked to indicate on a scale of 1 (almost never) to 6 (almost always) how often their child exhibited each behavior. A total composite measure was formed, at each time point, by averaging non-missing items with appropriate reflection so that the total score is an indication of “difficult” or reactive infant temperament. The 1- and 6-month scores correlated positively, r = .32, p < .01. For the present analyses, a composite was formed by averaging these two scores.

Social-Emotional Outcome Variables

Child Behavior Checklist

At 24 and 36 months, mothers reported on their children's internalizing and externalizing behaviors using the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 2-3 (CBCL; Achenbach, 1992). The CBCL consists of 99 items for which the mother rated how well the item described her child on a 3-point scale from 0 (not true of child) to 2 (very true of child). The raw CBCL scores were used for the present analyses.

Adaptive Social Behavior Inventory

At 24 and 36 months mothers completed the Adaptive Social Behavior Inventory (ASBI; Hogan, Scott, & Bauer, 1992). The ASBI is a 36-item scale designed to measure positive social behaviors in pre-kindergarten-aged children. The scale consists of three subscales, two of which assess positive social behavior (express, comply) and one of which assesses negative behavior (disrupt). Reliabilities for the subscales were .77, .82, and .60, respectively at 24 months, and .76, .82, and .62, respectively at 36 months.

Affect Dysregulation

Infant affect dysregulation was observed at 24 and 36 months in the laboratory during a child compliance clean-up task. After a solitary play procedure in which the child played with a variety of toys, the mother was instructed to involve her child in picking up the toys in the room. The clean-up session lasted a maximum of 5 minutes. Ratings of child and parent behavior during the clean-up session were made from a videotape of the session by trained coders at a central location. Negative affect and defiant non-compliance, each rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (very uncharacteristic) to 5 (very characteristic) were used as indices of affect dysregulation (NICHD, 2004). The inter-rater reliability (Winer, 1971) for the two scales was .82 and .89, and .91 and .89, at 24 and 36 months, respectively.

Covariates

Demographics

Income-to-needs ratio was averaged across 1- and 6-months. Mother's years of education and employment status (unemployed, employed and at work, or employed and on leave) were reported when the child was 6 months old. Mother's ethnicity, reported when the child was 1 month old, was dichotomized as European-American (0) and non-European-American (1).

Maternal depressive symptoms were measured at 6 months, using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The CES-D is a self-report scale intended to measure symptoms of depression in non-clinical populations. Mothers rated the frequency of 20 symptoms during the past week on a scale from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). A total score was calculated by summing responses on all items (Cronbach's α = .88).

24 and 36 Month Maternal Sensitivity

At 24 and 36 months, mothers and infants were observed during a 15 minute structured play situation in the home. At 24 months, videotapes were coded for global maternal sensitivity, intrusiveness, and positive regard using a 4-point rating scale ranging from 1 (not at all characteristic) to 4 (highly characteristic). Inter-rater reliability was assessed using intraclass correlations (Winer, 1971) and ranged from .69 to .80. A composite variable, created by reflecting the intrusiveness rating and then averaging the scores, was used in the present analyses. Internal consistency reliability for the composite was .74, and inter-rater reliability was .84. At 36 months, videotapes were coded for maternal supportive presence, respect for autonomy, and hostility using a global 7-point rating scale ranging from 1 (very low) to 7 (very high). Inter-rater reliability ranged from .72 to .82. A composite variable, created by reflecting the hostility rating and then averaging the scores, was used in the present analyses. Internal reliability for the composite was .78, and inter-rater reliability was .84.

Negative maternal behavior was rated during the compliance task described above and was used as a covariate in the analyses predicting affect dysregulation. Mother's sensitivity, overcontrol, undercontrol, positive regard, and negative regard were rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (very uncharacteristic) to 5 (very characteristic). Inter-rater reliability ranged from .43 to .76 at 24 months, and .77 to .82 at 36 months. Separate exploratory factor analyses of the 24- and 36-month ratings indicated a single factor at each time point. Therefore, the ratings were summed to form one maternal behavior composite for each time point (alphas = .67 at 24 months and .65 at 36 months). Sensitivity and positive regard were reverse scored before summing so that the variables reflect negative maternal behavior, a behavior which may exacerbate child affect dysregulation in the moment.

Data Reduction

In order to reduce the number of outcome variables, principal components analyses were conducted, similar to analyses conducted by NICHD ECCRN (1998). The root-one criterion (Kaiser, 1958) and the scree-test (Hurley & Cattell, 1962) were examined, and components were rotated to achieve approximations to simple structure in accordance with the varimax criterion (Kaiser). The same three-component solution was identified for both the 24-month and 36-month outcomes; these are described next with the component loadings at 24 and 36 months noted in parentheses. Behavior problems consists of CBCL Internalizing (.82/.77) and Externalizing (.91/.88) and ASBI Disrupt (.81/.88). Social competence consists of ASBI Express (.94/.94) and Comply (.75/.71). Affect dysregulation consists of negative affect (.94/.93) and defiance (.94/.92) during the clean-up tasks.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Before conducting analyses, variables were examined for missing values. Overall missingness was 2.5%. Because the proportion of missing values was so small, single imputation was reasonable (Acock, 2005; Schafer, 1999a) and efficient (Rubin, 1987). Missing data were imputed using the NORM software (Schafer, 1999b), which uses an Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm to replace missing values. Missingness was related to mother's age, education, employment status, and school status. Therefore, these variables were included in the imputation model along with all other predictor and outcome variables in our analytical model in order to preserve the relationships among the focal variables in our substantive analyses (Schafer, 1999b). Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Information for the Study Variables

| Variable | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant Temperament | 3.29 | .43 | 1.86 | 4.81 |

| Sensitivity to distress | 2.94 | .81 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Sensitivity to non-distress | 2.83 | .76 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Behavior Problems, 24 MO | 0.00 | 2.59 | −4.72 | 8.50 |

| Social Competence, 24 MO | 0.00 | 1.79 | −6.37 | 3.79 |

| Affect dysregulation, 24 MO | 2.36 | 1.08 | 2.00 | 10.00 |

| Behavior Problems, 36 MO | 0.00 | 2.62 | −4.99 | 10.27 |

| Social Competence, 36 MO | 0.00 | 1.77 | −7.15 | 3.23 |

| Affect dysregulation, 36 MO | 2.34 | 1.02 | 2.00 | 10.00 |

Next, correlations between the potential covariates and primary variables were examined. Criteria for inclusion as a covariate were significant associations with both a predictor and outcome variable. Mothers’ education, income to needs ratio, ethnicity, depressive symptoms, maternal negative behavior during the compliance tasks and maternal sensitivity at 24 and 36 months met criteria for inclusion as covariates and were therefore retained in further analyses. In addition, infant gender was examined as a moderator of all hypothesized effects in a series of preliminary analyses. These interactions were primarily non-significant (40 out of 42 interactions), and dismissed from further consideration.

The zero-order correlations between the study variables are shown in Table 2. Partial correlations between sensitivity to distress and sensitivity to non-distress and each child outcome variable, controlling for the covariates as well as infant temperament, are displayed in parentheses in columns 2 and 3 of this table. Importantly, when the covariates and temperament are partialled, sensitivity to distress remains a significant correlate of behavior problems at 24 and 36 months and social competence at 24 months. In contrast, none of the partial correlations among sensitivity to non-distress and the child outcomes are significant.

Table 2.

Zero-order and Partial Correlations among the Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Infant Temperament | --- | |||||||

| 2. Sensitivity to distress | .01 | --- | ||||||

| 3. Sensitivity to non-distress | −.07 | .68 ** (.63**) | --- | |||||

| 4.Behavior Problems 24 MO | .31** | −.20** (−.13*) | −.19** (−.03) | --- | ||||

| 5. Social Competence 24 MO | −.24** | .19** (.12*) | .16** (.02) | −.47** | --- | |||

| 6. Affect dysregulation 24 MO | .05 | −.06 (−.02) | −.06 (.00) | .17** | −.18** | --- | ||

| 7. Behavior Problems 36 MO | .31** | −.19** (−.11*) | −.19** (−.04) | .76** | −.40** | .15** | --- | |

| 8. Social Competence 36 MO | −.22** | .18** (.10) | .20** (.06) | −.39** | .70** | −.14** | −.48** | --- |

| 9. Affect Dysregulation 36 MO | .01 | −.03 (.00) | −.07 (−.04) | .10* | −.22** | .24** | .11** | −.19** |

Note. Partial correlations among sensitivity to distress and non-distress and child outcomes controlling for covariates and temperament are in parentheses.

p≤.05.

p≤.01.

Substantive Analyses

A series of hierarchical multiple regression analyses was conducted to test the hypotheses that sensitivity to distress would predict children's social-emotional outcomes independent of sensitivity to non-distress and that this association would be stronger among temperamentally reactive infants. Predictor variables were centered at the mean to reduce multicollinearity. The first step of the regression analysis included the covariates. The second step included the predictor variables: temperament, sensitivity to non-distress, and sensitivity to distress. In the third step, the three interaction terms (sensitivity to non-distress × temperament; sensitivity to distress × temperament; sensitivity to non-distress × sensitivity to distress) were entered. Finally, the fourth step included the three way interaction between temperament, sensitivity to non-distress, and sensitivity to distress. The interaction terms were created as products of the centered predictor variables. Significant interactions were probed by calculating and plotting simple slopes at +/−1 SD from the mean of the moderator (Aiken & West, 1991) and the region of significance for simple slopes was calculated using the computational tools provided online by Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (2006). That is, we indicate the value(s) of the moderator variable at which the simple slopes are statistically significant at the .05 alpha level if other than +/−1 SD. Results of the analyses are presented in Table 3. No three-way interactions were significant; therefore, results are reported only for steps 1-3.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses Predicting Social Emotional Outcomes

| Behavior Problems 24 MO |

Behavior Problems 36 MO |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Beta | ΔR2 | FΔ | B | SE | Beta | ΔR2 | FΔ | |

| Step 1: df= 5, 370 | .18 | 15.96** | .21 | 19.78** | ||||||

| Average Income-to-needs Ratio | −.06 | .05 | −.06 | −.04 | .05 | −.05 | ||||

| Mother's Education | −.16 | .06 | −.16** | −.17 | .06 | −.16** | ||||

| Mother's Ethnicitya | .97 | .34 | .14** | .46 | .33 | .07 | ||||

| Maternal Depression | .07 | .01 | .25** | .09 | .01 | .29** | ||||

| Concurrent Maternal Sensitivity | −.08 | .08 | −.06 | −.12 | .05 | −.13* | ||||

| Step 2: df= 8, 367 | .07 | 12.10** | .06 | 10.40** | ||||||

| Infant Temperament | 1.55 | .28 | .26** | 1.49 | .28 | .24** | ||||

| Sensitivity to Non-distress | .30 | .23 | .09 | .26 | .23 | .08 | ||||

| Sensitivity to Distress | −.53 | .20 | −.16** | −.39 | .20 | −.12* | ||||

| Step 3: df= 11, 364 | .01 | .98 | .01 | .87 | ||||||

| Sensitivity to Non-distress X Temperament | −.13 | .49 | −.02 | −.05 | .49 | −.01 | ||||

| Sensitivity to Distress X Temperament | −.51 | .47 | −.07 | −.41 | .47 | −.06 | ||||

| Sensitivity to Non-distress X Sensitivity to Distress | .02 | .19 | .01 | .18 | .19 | .04 | ||||

| Social Competence 24 MO |

Social Competence 36 MO |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Beta | ΔR2 | FΔ | B | SE | Beta | ΔR2 | FΔ | |

| Step 1: df= 5, 370 | .14 | 12.25** | .14 | 12.29** | ||||||

| Average Income-to-needs Ratio | .08 | .04 | .12* | .03 | .04 | .04 | ||||

| Mother's Education | .06 | .04 | .09 | .11 | .04 | .15** | ||||

| Mother's Ethnicitya | −.51 | .24 | −.11* | −.38 | .23 | −.08 | ||||

| Maternal Depression | −.02 | .01 | −.08 | −.03 | .01 | −.14** | ||||

| Concurrent Maternal Sensitivity | .18 | .05 | .18** | .10 | .03 | .16** | ||||

| Step 2: df= 8, 367 | .05 | 7.95** | .03 | 4.65** | ||||||

| Infant Temperament | −.82 | .20 | −.20** | −.71 | .20 | −.17** | ||||

| Sensitivity to Non-distress | −.30 | .16 | −.13 | −.10 | .16 | −.04 | ||||

| Sensitivity to Distress | .39 | .14 | .18** | .20 | .14 | .09 | ||||

| Step 3: df= 11, 364 | .00 | .60 | .00 | .66 | ||||||

| Sensitivity to Non-Distress X Temperament | −.46 | .35 | −.08 | −.36 | .35 | −.07 | ||||

| Sensitivity to Distress X Temperament | .36 | .34 | .07 | .47 | .34 | .09 | ||||

| Sensitivity to Non-Distress X Sensitivity to Distress | .01 | .14 | .00 | −.02 | .14 | −.01 | ||||

| Affect Dysregulation 24 MO |

Affect Dysregulation 36 MO |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Beta | ΔR2 | FΔ | B | SE | Beta | ΔR2 | FΔ | |

| Step 1: df= 6, 369 | .21 | 15.91** | .06 | 4.00** | ||||||

| Average Income-to-needs Ratio | .01 | .02 | .02 | .01 | .02 | .00 | ||||

| Mother's Education | −.01 | .03 | −.03 | −.01 | .03 | −.04 | ||||

| Mother's Ethnicitya | −.26 | .14 | −.09 | −.08 | .14 | −.03 | ||||

| Maternal Depression | −.01 | .01 | −.06 | .00 | .01 | .03 | ||||

| Concurrent Maternal Sensitivity | .01 | .03 | .02 | .01 | .02 | .03 | ||||

| Negative Maternal Behavior Compliance Task | .21 | .02 | .48** | .11 | .02 | .25** | ||||

| Step 2: df= 9, 366 | .01 | .99 | .00 | .13 | ||||||

| Infant Temperament | .12 | .12 | .05 | −.06 | .12 | −.02 | ||||

| Sensitivity to Non-distress | .09 | .10 | .07 | −.05 | .10 | −.03 | ||||

| Sensitivity to Distress | .02 | .09 | .01 | .02 | .09 | .02 | ||||

| Step 3: df= 12, 363 | .02 | 2.64* | .04 | 4.71** | ||||||

| Sensitivity to Non-Distress X Temperament | .30 | .20 | .09 | .46 | .21 | .15* | ||||

| Sensitivity to Distress X Temperament | −.50 | .20 | −.16** | −.43 | .20 | −.15* | ||||

| Sensitivity to Non-Distress X Sensitivity to Distress | −.11 | .08 | −.06 | −.25 | .08 | −.15** | ||||

Mother's ethnicity dummy coded 0= European-American, 1= non European-American.

p≤.05.

p≤.01.

Behavior Problems

The final models predicting behavior problems were significant: at 24 months, F(11,364)=11.47, p<.001, accounting for 26% of the variance; and at 36 months, F(11,364)=12.74, p<.001, accounting for 28% of the variance. Consistent with prediction, sensitivity to distress was negatively associated with behavior problems at both 24 and 36 months but sensitivity to non-distress was not. Thus, mothers who were more sensitive to infant distress had children with fewer behavior problems. The interaction terms were not significant.

Social Competence

The overall models predicting social competence were significant: at 24 months, F(11,364)=8.19, p<.001, accounting for 20% of the variance; and at 36 months, F(11,364)=7.18, p<.001, accounting for 18% of the variance. Consistent with the hypothesis, sensitivity to distress but not sensitivity to non-distress was positively associated with social competence at 24 months, but neither measure of sensitivity emerged as significant predictors at 36 months. There were no interaction effects for 24 and 36-month social competence.

Affect Dysregulation

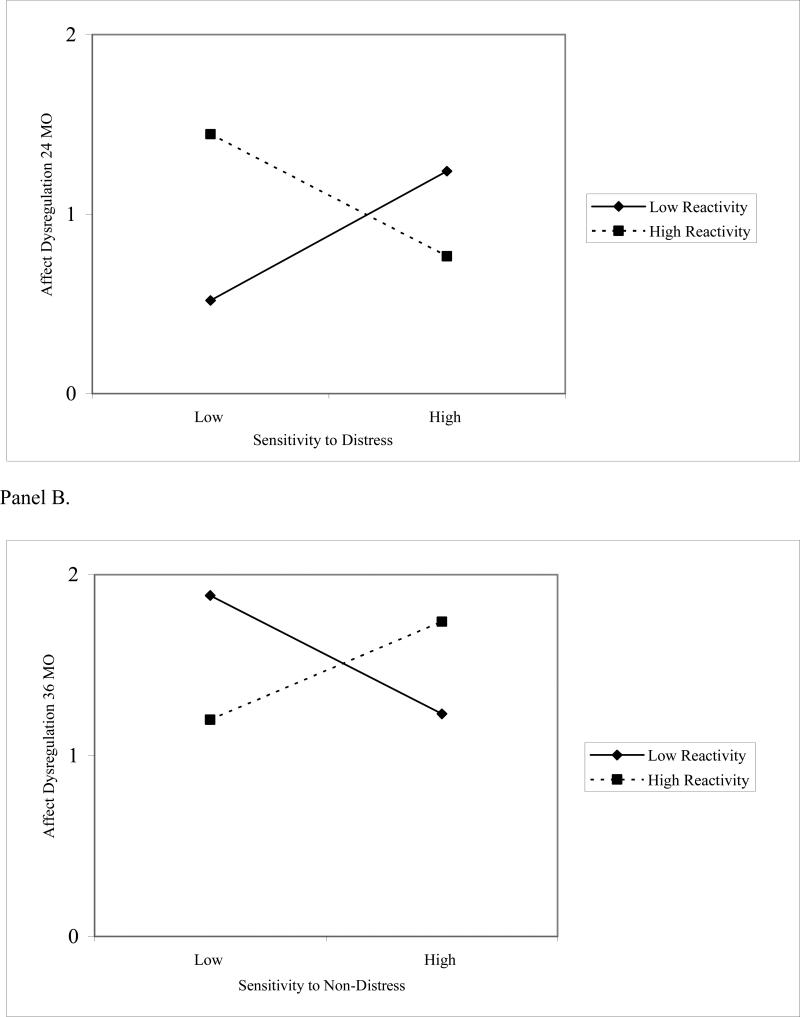

The overall models predicting affect dysregulation were significant; at 24 months, F(12, 363)=8.97, p<.01, accounting for 23% of the variance; and at 36 months, F(12, 363)=3.26, p<.01, accounting for 10% of the variance. There were no main effect associations between sensitivity to distress or non-distress and affect dysregulation at either time. However, there was a significant interaction between sensitivity to distress and temperament at both times. As illustrated in Figure 1 Panel A, and consistent with prediction, maternal sensitivity to distress was negatively associated with affect dysregulation at 24 months among highly reactive infants (b = −.21, p = .09). This simple effect was significant at p < .05 at 1.37 SD above the mean of temperamental reactivity. In contrast, maternal sensitivity to distress was positively associated with affect dysregulation among low reactive infants (b = .23, p =.06). This simple effect was significant at 1.08 SD below the mean of temperamental reactivity. Likewise, sensitivity to distress was negatively associated with affect dysregulation at 36 months among highly reactive infants (b= −.17, p= .17), but was positively associated with affect dysregulation among infants low on temperamental reactivity (b= .20, p=.11), similar to the pattern displayed in Figure 1 Panel A. These results were less robust than the results at 24 months as the simple effects were only statistically significant at rather extreme levels of temperamental reactivity; 2.91 SD above the mean and 2.05 SD below the mean respectively.

Figure 1.

Panel A. Moderating effect of infant temperamental reactivity on the association between maternal sensitivity to distress and affect dysregulation at 24 months. Panel B. Moderating effect of infant temperamental reactivity on the association between maternal sensitivity to non-distress and affect dysregulation at 36 months.

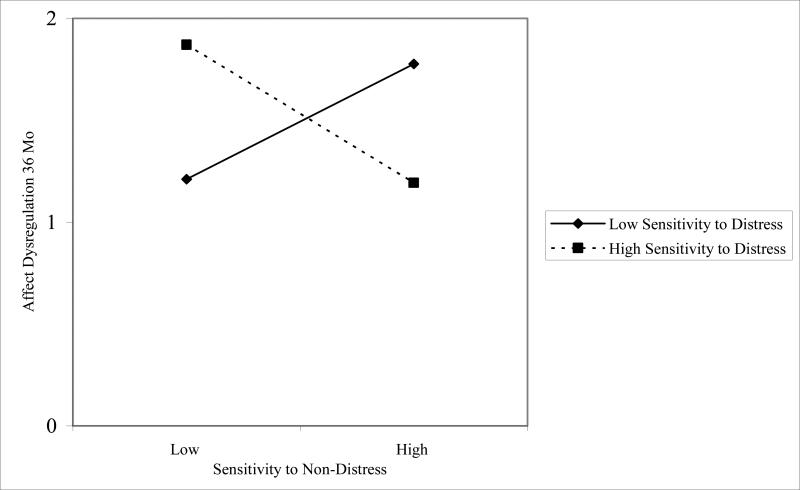

The other two interactions were significant also, but only in relation to affect dysregulation at 36 months. As illustrated in Figure 1 Panel B, the interaction effect between sensitivity to non-distress and temperament operated opposite to the interaction effect between sensitivity to distress and temperament. That is, maternal sensitivity to non-distress was primarily unassociated with affect dysregulation among highly reactive infants (b= .16, p= .25). This effect was only significant at an extreme 4.03 SD above the mean of temperamental reactivity. In contrast, maternal sensitivity to non-distress was associated with less affect dysregulation among infants low on temperamental reactivity (b= −.23, p= .08). This effect was significant at 1.38 SD below the mean of temperamental reactivity. Finally, consistent with our hypothesis, sensitivity to non-distress was linked with low affect dysregulation among infants whose mothers were also high on sensitivity to distress (b= −.24, p<.05) but linked with high affect dysregulation among infants whose mothers were not sensitive to distress (b= .17, p=.17). The latter effect was significant at 1.60 SD below the mean of sensitivity to distress. This effect is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Moderating effect of maternal sensitivity to distress on the association between maternal sensitivity to non-distress and affect dysregulation at 36 months.

Discussion

Consistent with our hypotheses, sensitivity to distress appears to be a key and unique factor in children's early social-emotional adjustment. Moreover, sensitivity to distress altered the manner in which sensitivity to non-distress was related to affect dysregulation, and there was support for the view that sensitivity to distress is particularly adaptive for temperamentally reactive infants in relation to affect dysregulation. These results have important theoretical, methodological, and applied implications as discussed below.

When both types of sensitivity were considered simultaneously, after controlling for a number of potential confounds, maternal sensitivity to infant distress was linked with fewer behavior problems at 24 and 36 months and greater social competence at 24 months, but sensitivity to non-distress was not. This is consistent with the view that how mothers respond to their children's negative emotions early in life serves a unique role in the development of positive social-emotional characteristics. These results extend previous research in two ways. First, they demonstrate that sensitive responses to infants’ bids for safety, protection, and comfort are highly salient in relation to indices of child adjustment in addition to infant-mother attachment security (Goldberg, et al., 1999; McElwain & Booth-LaForce, 2006). Second, they extend previous findings linking positive responses to older children's negative emotions with their positive adjustment (Eisenberg, et al., 1998) by demonstrating that this effect begins in infancy prior to parents’ use of more sophisticated emotion socialization strategies such as explanations about emotions. Additional research is needed to determine if the proposed pathways (i.e., a secure working model, increased emotion regulation, emotion understanding, a prosocial orientation) account for these effects. These effects were not moderated by infant temperament indicating that maternal sensitivity to distress is equally adaptive in relation to behavioral problems and social competence for infants of different temperamental dispositions.

Neither maternal sensitivity to distress nor sensitivity to non-distress independently predicted affect dysregulation at 24 or 36 months, but the proposed joint effect was supported. First, sensitivity to non-distress predicted lower affect dysregulation at 36 months among children whose mothers were also high on sensitivity to distress. This finding supports the view that mothers’ positive responsiveness to both positive and negative emotions is highly adaptive for young children particularly in relation to how they regulate their emotions. Such children are likely to display negative emotion appropriately, signaling their emotional needs to others, and to engage in adaptive self-regulatory behaviors. In contrast, sensitivity to non-distress predicted more affect dysregulation among children whose mothers were insensitive to their distress. This pattern may suggest inconsistent parenting or these mothers may minimize emotions by sending the message that negative emotions are problematic or unworthy of a response. Either situation may escalate negative arousal and undermine children's efforts to self-regulate. That emotion minimization is characteristic of mothers of insecure-avoidant infants, who display less adaptive emotion regulation than secure infants, is consistent with this view (Cassidy, 1994).

We also found that the effect of maternal sensitivity on affect dysregulation varied for children with different temperamental dispositions. That maternal sensitivity to infant distress buffered temperamentally reactive infants from affect dysregulation at 24 and 36 months was consistent with our view that maternal sensitivity to distress is particularly adaptive for infants who are frequently and intensely distressed. At 36 months, this effect was only apparent for children who were rated as extremely temperamentally reactive in infancy (2+ SD above the mean). Infants whose negative emotions are responded to sensitively likely develop a repertoire of adaptive emotion regulation skills that prevent the escalation of distress and may ultimately promote compliant and cooperative behavior. It could also be the case that infants whose mothers respond sensitively to their negative emotions encourage the development of a mutual positive bond that contributes to child compliance with their mothers’ requests (Kochanska, 1995; Kochanska, et al., 2005). Some investigators have proposed that a similar effect would be apparent for sensitivity to non-distress, which is believed to foster the development of an affiliative system between mother and child (MacDonald, 1992). Our results do not support this proposal. Instead we found that sensitivity to non-distress predicted less affect dysregulation among infants low on temperamental reactivity, but not infants high on temperamental reactivity. This supports our view that sensitivity to non-distress is not a sufficient condition to support adaptive regulation among infants who are frequently and intensely distressed and illustrates that distinct dimensions of sensitivity operate differently for children with various temperamental dispositions.

We had expected that sensitivity to distress would simply have no effect or a less positive effect on outcomes for low reactive children. Counter to this expectation, maternal sensitivity to distress was associated with greater affect dysregulation among infants who were low on temperamental reactivity. Perhaps low reactive infants find their mothers’ sensitive responses to their distress to be intrusive; as a result, their own regulatory abilities may be undermined, or they may become resistant to mothers’ efforts to recruit compliance. Further research is needed to examine these findings.

It is important to note that the interaction effects reported here are not fully consistent with Belsky's (1997) differential susceptibility hypothesis. Recently, Belsky, Bakersmans-Kranenburg, and van IJzendoorn (2007) clarified that one of the conditions necessary to demonstrate differential susceptibility is that the slope describing the relationship between parenting and the relevant child outcome must be steeper for one group of children than the other. In fact, we have demonstrated “contrastive effects” in which both slopes are significant and comparably strong, but in opposite directions. Thus, it is not the case that temperamentally reactive infants are more susceptible to the influence of sensitivity to distress than non-reactive infants, but rather that the nature of the influence of sensitivity to distress on affect regulation varies for the two groups of infants.

In sum, these results provide evidence that maternal sensitivity to infant distress is uniquely related to positive adjustment and this effect is independent of how mothers respond to non-distress cues. These results are consistent with previous findings in this data set, particularly the finding that maternal sensitivity to distress but not –non-distress predicted attachment security at 15 months (McElwain & Booth-LaForce, 2006) and the finding that maternal sensitivity was more predictive of externalizing behavior in first grade among children who were temperamentally reactive in infancy (Bradley & Corwyn, 2007). They also extend the general finding that the quality of mothering predicts children's social-emotional adjustment by clarifying that sensitivity to distress is the most predictive dimension of sensitivity in relation to these outcomes (NICHD ECCRN, 1998). The current findings also raise important directions for future research. First, even though sensitivity to distress and non-distress are highly related to one another in this sample, the fact that they predict infant outcomes differently suggests they are different constructs and may have different origins. In fact, our preliminary analyses indicated that sensitivity to non-distress appears to be more influenced by socio-demographic characteristics than is sensitivity to distress. Given increasing evidence that maternal sensitivity to distress is important to later child functioning, identifying its predictors is important both to develop effective methods to screen for insensitivity to negative emotions and to develop intervention efforts that foster sensitive responses to infant distress.

These results also support Tamis-LeMonda et al.'s (1996) view that sensitivity can best be examined when it is broken into its component parts or relevant domains. This approach requires greater attention to the measurement of sensitivity. If sensitivity to distress is a unique and important parenting behavior, as our results suggest, it is necessary to observe mother-child interaction in contexts that are likely to yield infant distress.

Four limitations reduce the strength of the conclusions that can be drawn from this study. First, the sample was primarily of European-American descent so it is unclear if these results generalize to minority groups. This is an important concern given racial and cultural differences in emotion display rules, affect expression, and emotion socialization practices (Fivush & Wang, 2005; Matsumoto, 1993). Second, the measure of affect dysregulation was based on a compliance task which most likely captured how young children regulate the emotion of anger but not fear and sadness. It is possible that a different pattern of associations would emerge in relation to the regulation of other types of negative affect. Third, maternal sensitivity was observed in a play context where infants were not likely to be distressed intensely or for long durations, which may undermine the validity of the resulting measure of sensitivity to distress. Related to this point, this sample is somewhat selected in that it consists only of dyads in which the infants became distressed in a generally non-distressing context. Therefore, caution should be taken in generalizing the results. Finally, the measure of maternal sensitivity to non-distress did not distinguish between sensitivity to neutral affect and sensitivity to positive affect. It may be that sensitivity to positive affect is more relevant to children's social emotional adjustment given its potential role in facilitating the up-regulation and maintenance of positive affect.

In conclusion, maternal sensitivity to distress and non-distress appear to have different associations with young children's social-emotional adjustment. In particular, sensitivity to infant distress assessed during the first year of life is linked to less affect dysregulation among temperamentally reactive infants, and fewer behavior problems and greater social competence among all infants, independent of maternal sensitivity to non-distress. In the future, greater attention should be paid to the appropriate measurement of sensitivity to infant distress and efforts should be made to identify the origins of this type of sensitivity.

Acknowledgments

Data collection was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) through a cooperative agreement (U10) calling for scientific collaboration between the grantees and NICHD staff. We thank the families for giving their time and the site coordinators and data collection staff for their dedication to the project.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist / 2-3 and 1992 Profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Acock AC. Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2005;67:1012–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth M, Blehar M, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bell SM, Ainsworth MD. Infant crying and maternal responsiveness. Child Development. 1972;43(4):1171–1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Variation in susceptibility to rearing influence: An evolutionary argument. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Bakersmans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. For better and for worse: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:300–304. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Hsieh K, Crnic K. Mothering, fathering, and infant negativity as antecedents of boys’ externalizing problems and inhibition at age 3 years: Differential susceptibility to rearing experience? Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:301–319. doi: 10.1017/s095457949800162x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Cassidy J. Mothers’ self-reported control of their preschool children's emotional expressiveness: A longitudinal study of associations with infant-mother attachment and children's emotion regulation. Social Development. 2003;12:477–495. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlin G, Hagekull B, Rydell AM. Attachment and social functioning: A longitudinal study from infancy to middle childhood. Social Development. 2000;9:24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation. Basic Books; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss. Basic Books; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Buck R. The communication of emotion. Guilford; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD. Origins and outcomes of individual differences in emotion regulation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59(2-3):53–72. 250–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Degnan KA. Temperament in early development. In: Ammerman RT, editor. Comprehensive handbook of personality and psychopathology. Vol. 3. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. pp. 64–84. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Johnson MC. Toddler regulation of distress to frustrating events: Temperamental and maternal correlates. Infant Behavior and Development. 1998;21:379–395. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Smith CL, Gill KL, Johnson MC. Maternal interactive style across contexts: Relations to emotional, behavioral, and physiological regulation during toddlerhood. Social Development. 1998;7:350–369. [Google Scholar]

- Carey WB, McDevitt SC. Revision of the Infant Temperament Questionnaire. Pediatrics. 1978;61:735–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. Fox NA, editor. Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. The development of emotion regulation: Biological and behavioral considerations. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59(2-3):228–249. Serial No. 240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Hyde JS, Essex MJ, Klein MH. Length of maternity leave and quality of mother-infant interactions. Child Development. 1997;68:364–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SC, Leerkes EM. Infant and maternal behaviors regulate infant reactivity to novelty at 6 months. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:1123–1132. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SC, Leerkes EM. Infant and maternal behavior moderate reactivity to novelty to predict anxious behavior at 2.5 years. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:17–34. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SC, Leerkes EM, Barrig Jo PS. Predicting aggressive behavior in the third year from infant reactivity and regulation as moderated by maternal behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:37–54. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidov M, Grusec JE. Untangling the links of parental responsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Development. 2006;77:44–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Carmen R, Pedersen FA, Huffman LC, Bryan YE. Dyadic distress management predicts subsequent security of attachment. Infant Behavior and Development. 1993;16:131–147. [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Blair KA, DeMulder E, Levitas J, Sawyer K, Auerbach-Major S, et al. Preschool emotional competence: Pathway to social competence. Child Development. 2003;74:238–256. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA. Mothers’ reactions to children's negative emotions: Relations to children's temperament and anger behavior. Merrill Palmer Quarterly. 1994;40:138–156. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Reiser M. Parental reactions to children's negative emotions: Longitudinal relations to quality of children's social functioning. Child Development. 1999;70:513–534. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Poulin RE, Eisenberg N, Madden-Derdich DA. The Coping with Childen's Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES): Psychometric properties and relations with children's emotional competence. Marriage & Family Review. 2002;34:285–310. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Wang Q. Emotion talk in mother-child conversations of the shared past: The effects of culture, gender, and event valence. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2005;6:489–506. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg S, Grusec JE, Jenkins JM. Confidence in protection: Arguments for a narrow definition of attachment. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:475–483. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C. Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: Theoretical models and preliminary analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden EP, Klein DN, Durbin CE, Olino TM. Positive emotionality at age 3 predicts cognitive styles in 7-year-old children. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:409–423. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan AE, Scott KG, Bauer CR. The Adaptive Social Behavior Inventory (ASBI): A new assessment of social competence in high risk three year olds. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 1992;10:230–239. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley JR, Cattell RB. The procrustes program: Producing direct rotation to test a hypothesized factor structure. Behavioral Science. 1962;7:258–262. [Google Scholar]

- Jahromi LB, Stifter CA. Individual differences in the contribution of maternal soothing to infant distress reduction. Infancy. 2007;11:255–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2007.tb00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser HF. The varimax criterion for analytic rotation in factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1958;23:187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Children's temperament, mother's discipline, and security of attachment: Multiple pathways to emerging internalization. Child Development. 1995;66:597–615. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N, Carlson JJ. Temperament, relationships, and young children's receptive cooperation with their parents. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:648–660. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald K. Warmth as a developmental construct: An evolutionary analysis. Child Development. 1992;63:753–773. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D. Ethnic differences in affect intensity, emotion judgments, display rule attitudes, and self-reported emotional expression in an American sample. Motivation and Emotion. 1993;17:107–123. [Google Scholar]

- McElwain NL, Booth-LaForce C. Maternal sensitivity to infant distress and nondistress as predictors of infant-mother attachment security. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:247–255. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medoff-Cooper B, Carey WB, McDevitt SC. Early Infancy Temperament Questionnaire. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1993;14:230–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore G, Calkins SD. Infants’ vagal regulation in the still-face paradigm is related to dyadic coordination of mother-infant interaction. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:1068–1080. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network Early child care and self-control, compliance, and problem behavior at twenty-four and thirty-six months. Child Development. 1998;69:1145–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network Child care and mother-child interaction in the first three years of life. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1399–1413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network Affect dysregulation in the mother-child relationship in the toddler years: Antecedents and consequences. Development & Psychopathology. 2004;16:43–68. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network . Child care and child development: Results from he NICHD study of early child care and youth development. Guilford; New York: 2005. Chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity, and child functioning at 36 months. pp. 151–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Belsky J, Putnam S, Crnic K. Infant emotionality, parenting, and 3-year inhibition: Exploring stability and lawful discontinuity in a male sample. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:218–227. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson DR, Moran G. A categorical description of infant-mother relationships in the home and its relation to Q-sort measures of infant-mother interaction. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1995;60(2-3):111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. Wiley; New York, NY: 1998. pp. 105–176. Series Ed. Vol. Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Multiple imputation: A primer. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1999a;8:3–15. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. NORM: Multiple imputation of incomplete multivariate data under a normal model (Version 2.03) [Computer software] 1999b available from: http://www.stat.psu.edu/~jls/misoftwa.html.

- Shiota MN. Silver linings and candles in the dark: Differences among positive coping strategies in predicting subjective well-being. Emotion. 2006;6:335–339. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.2.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Stifter CA, Donelan-McCall N, Turner L. Mothers’ regulation responses in response to toddlers’ affect: Links to later emotion self-regulation. Social Development. 2004;13:40–55. [Google Scholar]

- Stern DN. The interpersonal world of the infant: A view from psychoanalysis and developmental psychology. Basic Books; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-LeMonda CS, Bornstein MH, Baumwell L, Damast AM. Responsive parenting in the second year: Specific influences on children's language and play. Early Development and Parenting. 1996;5:173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Chess S. Temperament and development. Brunner/Mazel; Oxford, England: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;(2-3):25–52. Serial No. 240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Sensitivity and security: New questions to ponder. Child Development. 1997;68:595–597. [Google Scholar]

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:320–333. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Boom DC. The influence of temperament and mothering on attachment and exploration: An experimental manipulation of sensitive responsiveness among low-class mothers with irritable infants. Child Development. 1994;65:1457–1147. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Boom DC. Do first-year intervention effects endure? Follow-up during toddlerhood of a sample of Dutch irritable infants. Child Development. 1995;66:1798–1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer BJ. Statistical principles in experimental design. McGraw Hill; New York: 1971. [Google Scholar]