Abstract

Neuroinvasive West Nile virus (WNV) infections may cause acute flaccid paralysis (AFP); in fatal cases anterior horn cell (AHC) loss is presumed to be a due to direct viral infection. In related animal models, however, glutamate excitoxicity mediates bystander injury of uninfected AHCs, suggesting additional pathogenetic mechanisms. We examined expression of the principal excitatory amino acid transporter (EAAT) of astrocytes (i.e. EAAT2 in humans, glutamate transporter-1 in hamsters) in the spinal cord of human WNV AFP patients and in hamsters with WNV AFP by immunohistochemistry. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), synaptic and dendritic markers (i.e. synaptophysin, microtubule-associated protein-2 [MAP2]), immune activation (HLA-DR), and viral antigens were also evaluated. Humans and hamsters with WNV-induced AFP had decreased spinal grey matter EAAT expression despite greater numbers of GFAP-positive astrocytes compared to controls. Areas of diminished EAAT expression showed reduced synaptic and dendritic protein expression and prominent local inflammation but few infected neurons. These findings suggest that WNV infection results in local immune activation within the spinal cord that in turn causes a failure of astrocyte glutamate reuptake even as the number of astrocytes increases; rising extracellular glutamate levels may then drive excitotoxic injury of both infected and uninfected AHCs. The pathogenesis of this increasingly common disorder likely involves immune response and excitotoxicity mechanisms that are potential therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Acute flaccid paralysis, Astrocyte, Excitotoxic injury, Glutamate transporters, West Nile virus

INTRODUCTION

Since West Nile virus (WNV) first appeared in the Western hemisphere in 1999 there have been more than 20,000 symptomatic infections in North America, and serological data suggest that over a million people have been infected with this pathogen (1, 2). Although West Nile neuroinvasive disease (WNND) still occurs in only a small proportion of infected individuals, it is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality; these patients can develop meningitis, encephalitis, acute flaccid paralysis (AFP), or some combination thereof. The AFP appears to be due to a true poliomyelitis; pathological examination of the spinal cord in fatal cases often reveals predominantly grey matter inflammation and extensive destruction of anterior horn cells (AHCs) across multiple spinal levels (3–6). While the exact incidence of WNV-induced AFP has been difficult to ascertain, some estimates suggest it occurs in up to 5% to 10% of patients with WNND (6). Recovery of weakness among survivors is highly variable; some patients have severe long-term motor deficits whereas others show substantial clinical improvement over time (7, 8). This variability implies a spectrum of cellular events within the spinal cord ranging from reversible dysfunction of motor system pathways to death of AHC. Since AHCs may be directly infected by WNV, the latter has universally been ascribed to virus-induced neuronal cell death (1–8).

Related mosquito-borne viruses have been extensively investigated in animal models, and studies of pathogenesis suggest a complex interplay between the virus, the host immune response and central nervous system (CNS) neurons. Experimental models in rodents generally confirm that neurons are the main cell type directly targeted by these pathogens (9, 10) but discrete populations of infected neurons undergo different types of cell death (11), and uninfected neurons can be damaged or destroyed via bystander mechanisms (12–14). In a mouse model of alphavirus encephalomyelitis caused by neuroadapted Sindbis virus (NSV), spread of the pathogen from the brain to the spinal cord causes progressive hind limb paralysis and AHC destruction that is non-cell-autonomous and involves glutamate excitotoxicity (15–17). In that model, local innate immune responses drive the excitotoxic process by causing a profound but focal and ultimately reversible defect in astrocyte glutamate reuptake in lumbar spinal cord grey matter (16, 18). Therapies that either target the host responses or the downstream excitotoxicity pathways triggered by them can protect AHCs and reduce the severity of paralysis in NSV-infected mice (13–18). Confirmation of similar events in WNV-induced AFP would both clarify disease pathogenesis and offer novel therapeutic options focused on neuroprotective rather than antiviral approaches.

Excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs) are a family of proteins expressed by glia and neurons that are directly responsible for extracellular glutamate reuptake within the CNS. In mice, targeted disruption of the astrocyte protein, glutamate transporter-1 (GLT-1), reduces glutamate transport by as much as 90% and promotes neurodegeneration (19, 20). The homologous astrocyte protein in humans, EAAT2, disappears from the spinal grey matter of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and within active demyelinating lesions of multiple sclerosis (MS) (21–23). We recently identified a selective loss of GLT-1 within lumbar spinal cord gray matter in mice with NSV encephalomyelitis; not only is this loss directly responsible for excitotoxic AHC damage and hind limb paralysis but it also is driven by the pro-inflammatory cytokine response elicited by infection; the paralysis can reverse itself as inflammation subsides (16, 18). We hypothesize that similar mechanisms might underlie the AFP associated with WNV invasion of the spinal cord and that they might effect neuroaxonal damage in many CNS inflammatory and demyelinating diseases.

Here, we demonstrate histopathological features of fatal human cases of WNV-induced AFP that are similar to those in the spinal cords of NSV-infected animals (i.e. immune activation and locally decreased expression of EAAT2) despite increased total numbers of astrocytes. Both pre-synaptic inputs and post-synaptic dendritic proteins surrounding many of the remaining AHCs also disappear, suggesting that synaptic disruption may offer an additional explanation for motor impairment beyond actual AHC destruction. Similar astrocytic changes were also identified in the spinal cords of hamsters using a recently reported experimental system of WNV-induced AFP (24). These findings support a model in which the spread of WNV to the spinal cord triggers inflammatory production of soluble mediators that are a proximal cause of dysfunction and diminished expression of astroglial glutamate transporters even as these glial cells become more numerous in response to the infection. These changes lead to high extracellular glutamate levels that may ultimately damage AHCs and/or the synaptic and dendritic structures surrounding them. If this scenario is confirmed, targeting pathogenic immune responses or the glutamate receptors on AHCs may offer a novel therapeutic approach for patients with WNV-induced AFP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human Subjects

This study was performed using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, archival spinal cord and lower brainstem tissue samples from 4 patients with confirmed WNND and AFP. Clinical and autopsy data were collected at the University of Colorado Denver Health Sciences Center. Control human spinal cord tissues were obtained from 4 age-matched individuals who died from various non-infectious and non-neurological disorders. These specimens came from the Medical Examiner’ Office in Baltimore, Maryland via a research protocol at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. The Institutional Review Boards at both institutions approved the use of these specimens for these studies.

Animal Samples

A hamster model of AFP caused by retrograde axonal transport of WNV into the spinal cord via direct injection into the sciatic nerve has recently been described (24). Lumbar spinal cord tissue sections from these animals were obtained from the investigators at Utah State University, Logan UT who originally developed this model. All tissues were collected from hamsters at peak paralysis (day 10–16 post-infection). The lumbar spinal cords of uninfected control hamsters were analyzed for comparison purposes. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Utah State University approved the use of these specimens for the studies described here. Studies were undertaken in accordance with the United States Public Health Service’s Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Immunohistochemistry and Silver Staining

Immunohistochemistry was performed on axial cross sections of spinal cord or lower brainstem using an avidin-biotin complex (ABC) method. For each marker studied, control and experimental sections were processed at the same time with the identical reagents and under the same conditions to eliminate the possibility that staining differences might be explained by any other reason that varying levels of antigen expression. After deparaffinization, sections were processed for antigen retrieval to unmask binding epitopes of the various primary antibodies used in this study according to summarized methods (Table 1). Slides were then sequentially treated with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase, 10% normal serum of the species in which the secondary antibody was raised for 30 minutes to block non-specific binding, and then one of the primary antibodies under optimized experimental conditions (Table 1). After washing with Tris-buffered saline, sections were then incubated with the appropriate biotin-conjugated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, 1:200 at 25°C, for 30 minutes), followed thereafter by incubation with ABC reagent (Vector) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Peroxidase labeling was then visualized by treating slides with 10% 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and the sections counterstained with hematoxylin. After coverslipping and drying, slides were examined by light microscopy. Dendritic arborization in spinal grey matter was on Bielschowsky impregnation sections prepared by a previously described protocol (11, 14, 15).

Table 1.

Primary Antibodies Used for Immunohistochemistry

| Target Antigen (Target Species) | Antibody Type (Host Species, Isotype) | Supplier (Clone) | Dilution and Incubation | Antigen Retrieval Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAAT2 (Human) | Polyclonal (Guinea Pig) | Millipore, Billerica, MA | 1:100, overnight, 4°C | None |

| GFAP (Human) | Monoclonal (Mouse IgG1) | Dako, Carpinteria, CA (6F2) | 1:100, overnight, 4°C | Microwave 300 W 20 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0 |

| Synaptophysin (Human) | Monoclonal (Rabbit IgG) | Abcam, Cambridge, MA (YE269) | 1:20, overnight, 25°C | Microwave 300 W 20 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0 |

| MAP2 (Human) | Polyclonal (Rabbit) | Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO | 1:100, overnight, 4°C | Microwave 1200W 15 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0 |

| HLA-DR (Human) | Monoclonal (Mouse IgG1) | Dako (CR3/43) | 1:200, overnight, 4°C | Microwave 300 W 15 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0 |

| GLT-1 (Hamster) | Polyclonal (Guinea Pig) | Millipore | 1:100, overnight, 4°C | None |

| GFAP (Hamster) | Monoclonal (Mouse IgG1) | Millipore (GA-5) | 1:500, overnight, 4°C | Microwave 300 W 20 minutes in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0 |

| WNV Envelope Protein | Polyclonal (Rabbit) | Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO | 1:500, overnight, 4°C | None |

EAAT2: Excitatory amino acid transporter-2; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; GLT-1, glutamate transporter-1; WNV, West Nile virus.

Image Acquisition and Analysis

All slides were examined using a Nikon Ti-U inverted microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY). Images were acquired by means of a DS-Fi-1 camera (Nikon), supported by the NIS-Elements Basic Research acquisition and analysis software package (Nikon). For GLT-1/EAAT2 expression, a blinded examiner assessed staining intensity using a semiquantitative 0 to 3 scoring scale. Staining was graded according to the following criteria: absent (score 0), minimal (score 1); moderate (score 2); or intense (score 3). Since transporter expression was often patchy, a minimum of 5 randomly selected high-power microscope fields of ventral grey matter were graded for each specimen. The mean ± SEM of the individual scores for each sample were determined. The same high-power fields were also scored for the intensity of grey matter inflammation based on hematoxylin staining as follows: absent (score 0); mild (score 1); moderate (score 2); or severe (score 3). Individual AHC morphology and EAAT2 staining pattern surrounding each of these cells in the 4 WNV cases were based on the following categories: angulated cell body with increased surrounding EAAT2 expression (Grade 1), rounded cell body with increased surrounding EAAT2 expression (Grade 2), rounded cell body with diminished surrounding EAAT2 expression (Grade 3), rounded and enlarged cell body, indistinct intracellular structure, and very diminished surrounding EAAT2 expression (Grade 4), or indeterminate. More that 200 AHCs were scored in at least 3 slides of each of the 4 WNV-infected cases and proportions of cells in each category in the 4 cases were determined. For glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunostaining, the number of positive cells was counted in each ventral horn of the spinal cord (defined as grey matter ventral to the level of the central canal) for each specimen. The mean ± SEM of the counts for each ventral horn of all 4 samples in each experimental group (8 ventral horns total per group) is shown. For synaptophysin staining, the density of synaptic inputs adjacent to individual AHCs was graded using a semiquantitative grading scale defined as normal (Grade 1), mildly reduced (Grade 2), moderately reduced (Grade 3), or severely reduced (Grade 4). Completely absent staining was not seen. At least 100 AHCs from a minimum of 2 slides of each of the 4 WNV-infected cases were scored by a blinded examiner and the proportion in each category was summed across all 4 cases. The HLA-DR, MAP2 and WNV antigen immunostaining and the Bielschowsky silver preparations were not subjected to quantitative analysis but expression was assessed in all 4 human cases. Instead, representative examples of staining for each marker or labeling technique are shown.

RESULTS

Clinical, Laboratory, and Autopsy Findings

Sections of spinal cord and lower brainstem from 4 fatal cases of WNV-induced AFP were compared to specimens from 4 age-matched controls without known infectious or neurological disease. Clinical, virological and routine histopathological features of the WNV cases are shown in Table 2. Each patient had overt weakness of all 4 limbs at the time of death; their spinal cords showed had frank inflammatory cell infiltration and AHC loss. Importantly, viral antigen was detected in neurons in only 2 AHCs in one of the cases (Table 2). This low level of detection of WNV antigens by immunohistochemistry at the late stages of fatal cases of WNND is consistent with previous reports (25).

Table 2.

Clinical, Laboratory and Spinal Cord Pathological Findings in Patients With West Nile Virus-Induced Acute Flaccid Paralysis

| Parameter | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Gender | 57 years, F | 63 years, M | 46 years, F | 66 years, M |

| Main Clinical Features | Meningoencephalitis, Myelitis | Meningoencephalitis, Myelitis | Meningoencephalitis, Myelitis | Meningoencephalitis, Myelitis |

| Disease Confirmation Criteria | Serum WNV IgG, CSF WNV PCR | Serum WNV IgM, CSF pleocytosis | Serum WNV IgM, CSF WNV IgM | Serum WNV IgM, CSF pleocytosis |

| Severity of AFP | Complete flaccid quadriplegia | Moderate quadriparesis | Moderate quadriparesis | Severe quadriparesis |

| Spinal Cord Pathology | Severe inflammation; Moderate AHC loss | Moderate inflammation; Severe AHC loss | Mild-moderate inflammation; Moderate AHC loss | Moderate inflammation; Severe AHC loss |

| Viral Antigen in Tissue | None | None | Minimal | None |

| Duration of Disease | 24 days | 17 days | 15 days | 21 days |

| Other Disease Features | Immunocompromised host (lung transplant 2 years prior); Treated with IVIg containing high-titer anti-WNV antibodies at presentation | Immunocompromised host (chemotherapy and bone marrow transplant 2 years prior) |

F = female; M = male; WNV = West Nile virus; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; AHC = anterior horn cell.

Comparative Expression of Astrocyte Proteins

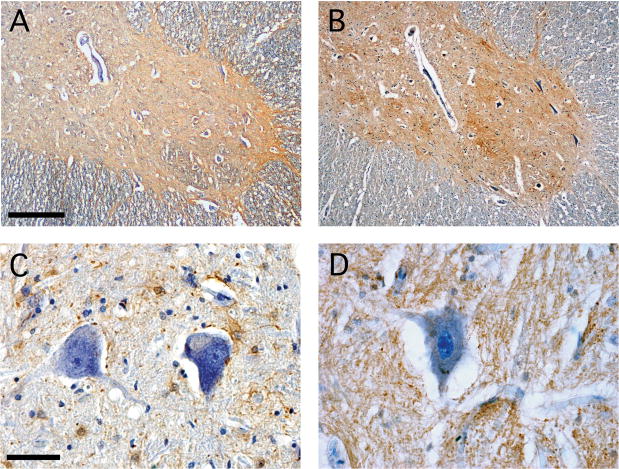

Based on observations made in related animal models (16, 18), we sought to compare spinal cord EAAT2 expression in patients with WNV-induced AFP and normal controls. We also compared expression of GFAP to assess the number and distribution of astrocytes in the same grey matter regions in these cases. At low magnification, staining of normal human spinal cord revealed diffuse GFAP and EAAT2 signal throughout spinal grey matter (Fig. 1A, B). Higher power views showed discrete GFAP-positive cells in close proximity to the cell bodies of individual AHCs (Fig. 1C). Conversely, EAAT2 staining was more diffuse in the grey matter neuropil and was not associated with discrete cells (Fig. 1D). Overall, tissue expression of the EAAT2 transporter protein was consistent with previously reported expression in the normal human spinal cord (22).

Figure 1.

Astrocyte glial fibrillary acid (GFAP) and excitatory amino acid transporter-2 (EAAT2) show overlapping distribution in the normal human spinal cord. (A, B) At low magnification, GFAP is detectable in both grey and white matter (A), whereas EAAT2 is present diffusely only throughout grey matter (B). (C, D) At higher magnification, numerous GFAP-positive astrocytes and their processes are in close proximity to cell bodies of individual anterior horn cells (C). EAAT2 localizes to grey matter neuropil and not to discrete cellular elements (D). Immunoperoxidase (brown) and hematoxylin (purple), scale bars: 200 μm (A, B), 50 μm (C, D).

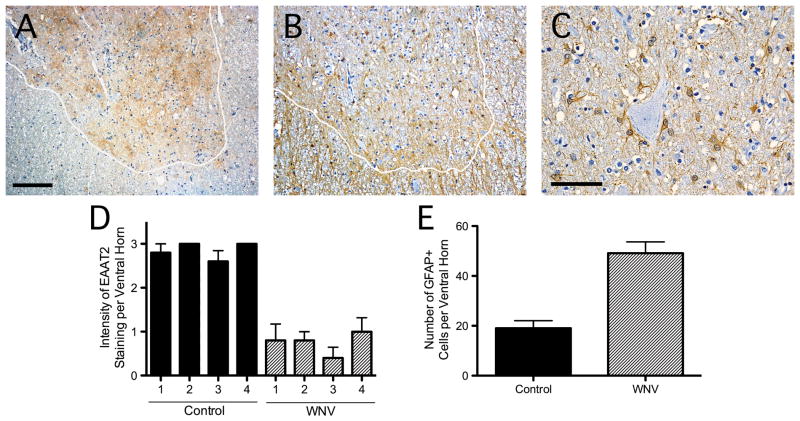

In the spinal cords of patients with WNV-induced AFP, there was less grey matter staining than in controls (Fig. 2A, D). Diminished transporter expression could not be attributed to a loss of astrocytes because the numbers of GFAP-positive cells increased in spinal grey matter of WNV-infected patients relative to uninfected individuals (Fig. 2B, E). Many astrocytes were in close proximity to the enlarged, pale-appearing AHCs commonly observed in the WNV specimens (Fig. 2C). Since there was minimal immunostaining for WNV, no relationship either between reduced EAAT2 or increased GFAP staining and infected AHCs could be identified (Table 2, staining data not shown).

Figure 2.

Spinal cords of patients with West Nile virus (WNV)-induced acute flaccid paralysis show divergent expression of excitatory amino acid transporter-2 (EAAT2) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). (A, B) At low magnification, WNV infection of the spinal cord causes a patchy loss of EAAT2 in the grey matter (demarcated by the white line) (A). GFAP-positive astrocytes are preserved throughout spinal grey matter in the same case (B). (C) GFAP-positive cells are in close proximity to individual anterior horn cells. (D) EAAT2 immunoreactivity in the ventral spinal grey matter of 4 WNV AFP patients is less than in 4 uninfected controls. (E) The number of GFAP-positive cells in these same spinal cord regions increases with infection. Immunoperoxidase (brown) and hematoxylin (purple), scale bars: 200 μm (A, B), 100 μm (C).

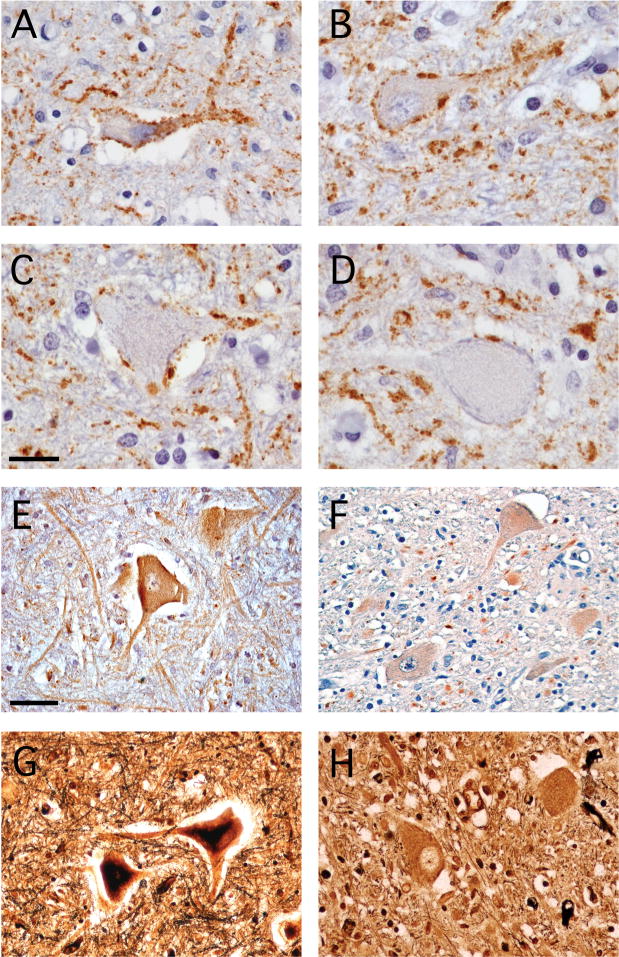

At higher magnification, a dense rim of EAAT2 staining was often observed adjacent to AHCs with angulated cell bodies (Fig. 3A). This Grade 1 staining pattern was not routinely found around the AHCs in normal spinal cord tissue (Fig. 1D), but was seen in 27 of 204 (13.2%) of the total AHCs analyzed among the 4 WNV AFP cases. For AHCs with more rounded cell bodies, some of which also had less distinct nuclei and nucleoli, the rim of EAAT2 protein outlining the cell body was less apparent (Fig. 3B, C). These Grade 2 and Grade 3 AHCs comprised 61 of 204 (29.9%) and 52 of 204 (25.5%) of the total AHCs analyzed, respectively, in the WNV AFP cases. Finally, among the AHC that had lost much of their distinguishable intracellular structure, appearing almost as ghost-like cells within the tissue sections, adjacent EAAT2 expression had largely disappeared (Fig. 3D). These Grade 4 cells comprised 21 of 204 (10.3%) of the total AHCs examined. We speculate but cannot prove that such changes to AHC morphology and EAAT2 expression occur in a sequential manner.

Figure 3.

Distinct patterns of excitatory amino acid transporter-2 (EAAT2) expression around individual anterior horn cells (AHCs) in the spinal cords of West Nile virus (WNV)-infected patients. (A) Many AHCs with angulated shapes have a dense rim of EAAT2 protein directly surrounding the cell body (Grade 1). (B) Some AHCs with more rounded cell bodies retain this rim of staining (Grade 2). (C) AHCs with less distinct nuclei and nucleoli have less adjacent EAAT2 immunoreactivity (Grade 3). (D) Many of the largest AHCs with almost no definable intracellular structure show the least amount of surrounding EAAT2 expression (Grade 4). Immunoperoxidase (brown) and hematoxylin (purple), scale bar: 20 μm (A–D).

Spinal Cord Glutamate Transporter-1 in West Nile Virus-Infected Hamsters

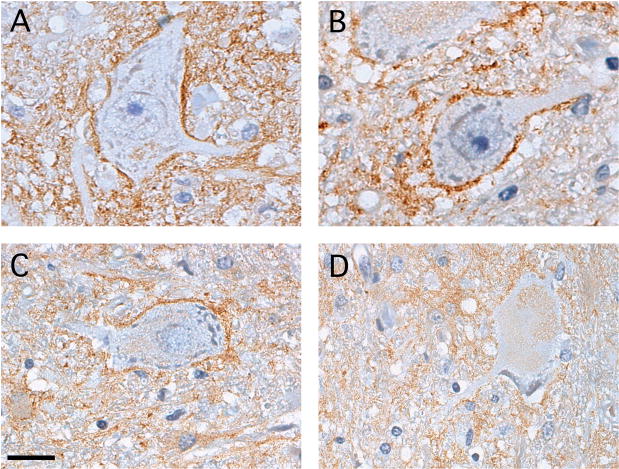

A recent study showed that hamsters develop AFP following WNV inoculation directly into the ipsilateral sciatic nerve; retrograde axonal transport carries the virus directly into the lumbar spinal cord where AHCs become infected (24). To investigate whether such animals develop local changes in glial glutamate transporter expression, GLT-1 and GFAP immunoreactivity were examined in lumbar spinal cord tissue sections. Compared to uninfected control animals (Fig. 4A), the spinal grey matter of WNV-infected hamsters contained more GFAP-positive reactive astrocytes (Fig. 4B, C). Conversely, the diffuse expression of GLT-1 throughout grey matter neuropil of the normal hamster spinal cord (Fig. 4D) became patchy and less intense in the WNV-infected animals (Fig. 4E, F). As in the human samples, we did not find any spatial relationship between changes in GLT-1 or GFAP staining and neurons containing viral antigens in the hamster spinal cord tissue sections (data not shown). This may again be due to the low frequency of infected cells relative to the much more widespread astroglial changes in grey matter. Thus, levels of this glial glutamate transporter appear to decline in spinal grey matter of WNV-infected hamsters, as they do in humans with WNV-induced AFP, despite an apparent increase in the total number of astrocytes in these regions.

Figure 4.

Patterns of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and glutamate transporter-1 (GLT-1) expression in the spinal cords of normal hamsters and those with acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) due to experimental West Nile virus (WNV) infection. (A) GFAP staining in the ventral grey matter of a representative control animal. (B) Increased GFAP immunostaining in the ventral grey matter in a WNV-infected animal. (C) Quantification of GFAP-positive cells in ventral grey matter demonstrates more cells in WNV-infected (n = 4) than in control hamsters. (D, E) GLT-1 expression is less in these same regions in an infected hamster (E) compared to a control (D). (F) Semiquantitative assessment of ventral spinal grey matter GLT-1 staining in both groups of hamsters shows the extent of transporter loss. Immunoperoxidase (brown) and hematoxylin (purple), scale bar: 100 μm (A, B, D, E).

Synaptic and Dendritic Changes in the Spinal Grey Matter of West Nile Virus-Infected Patients With Acute Flaccid Paralysis

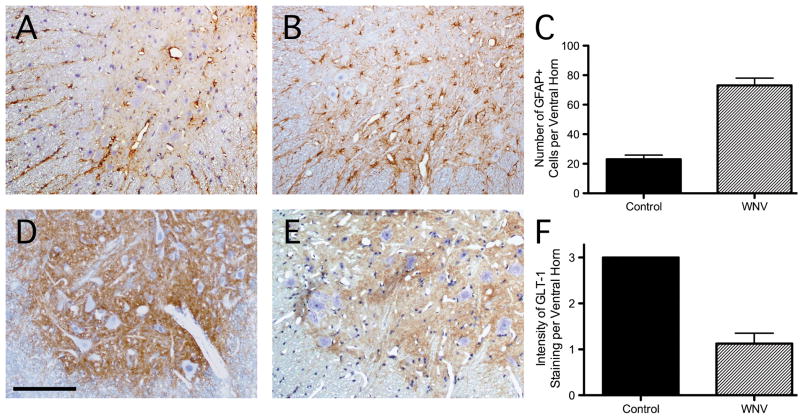

Beyond its effects on the neuronal cell body, glutamate can also damage synapses and dendrites. We hypothesized that disrupted synaptic contacts and dendritic projections of spinal AHCs could explain some of the impairment seen in patients with WNV-induced AFP and that synaptic changes, may account for reversibility of disease in those patients who recover motor function. Therefore, synaptophysin expression as a marker of synaptic integrity was examined in the spinal cords of infected and control cases. We observed a spectrum of changes immediately surrounding AHCs in the spinal cords of WNV AFP patients. Many AHCs with an angulated shape had dense synaptophysin expression surrounding their cell bodies and proximal processes (Fig. 5A). Overall, this Grade 1 staining pattern was seen in 24 of 104 (23.1%) of the AHCs analyzed among the 4 WNV cases. In cells with less angulated shapes, synaptic contacts were correspondingly less dense (Fig. 5B, C). These Grade 2 and Grade 3 reductions in the density of synaptic contacts occurred in 31 of 104 (29.8%) and 26 of 104 (25.0%) of total AHCs, respectively. The most enlarged AHCs with the least well-defined intracellular structure had adjacent synaptophysin expression that was markedly reduced (Fig. 5D). This Grade 4 level of synaptic loss was identified in 23 of 104 (22.1%) of total AHCs. Once again, however, we cannot prove that these changes were sequential events.

Figure 5.

Synaptic and dendritic markers identify changes to these structures in the spinal grey matter of patients with West Nile virus (WNV). (A) Anti-synaptophysin antibody staining identifies dense synaptic contacts around the cell bodies and proximal processes of a small, angulated anterior horn cell (AHC) (Grade 1). (B, C) Synaptophysin staining is variably reduced adjacent to cells with more rounded cell bodies (B, Grade 2 and C, Grade 3). (D) Synaptic contacts are particularly sparse in the largest AHC with the least distinct intracellular structure (Grade 4). (E) A microtubule-associated protein-2 (MAP2)-specific antibody reveals dense staining of both motor neuron cell bodies and dendritic processes in the adjacent grey matter neuropil of a normal human spinal cord. (F) MAP2 staining on cell bodies is diminished and is virtually absent from adjoining dendrites in a WNV-infected patient. (G) Silver staining shows an extensive dendritic network throughout the normal spinal cord grey matter. (H) Dendritic processes in the spinal cord are replaced by densely stained blebs in a WNV-infected patient. Immunoperoxidase (brown) and hematoxylin (purple) (A–F), modified Bielschowsky silver stain (black) (G, H), scale bars: 20 μm (A–D), 50 μm (E–H).

Immunostaining for microtubule-associated protein-2 (MAP2) identifies large motor neuron cell bodies in the spinal cord and labels the intricate dendritic network present in grey matter neuropil. In normal spinal grey matter, there were MAP2-positive motor neuron cell bodies with extensive surrounding dendritic processes (Fig. 5E). In contrast, specimens from WNV-infected patients revealed both reduced neuronal staining and a dramatic loss of this protein on dendrites in all 4 cases (Fig. 5F). Silver staining demonstrated a dense dendritic arbor in control cases (Fig. 5G), whereas in WNV AFP cases these intricate cellular processes were replaced by dense blebs (Fig. 5H). These data show that patients with WNV AFP develop synaptic and dendritic changes in motor areas that may contribute to their clinical deficits.

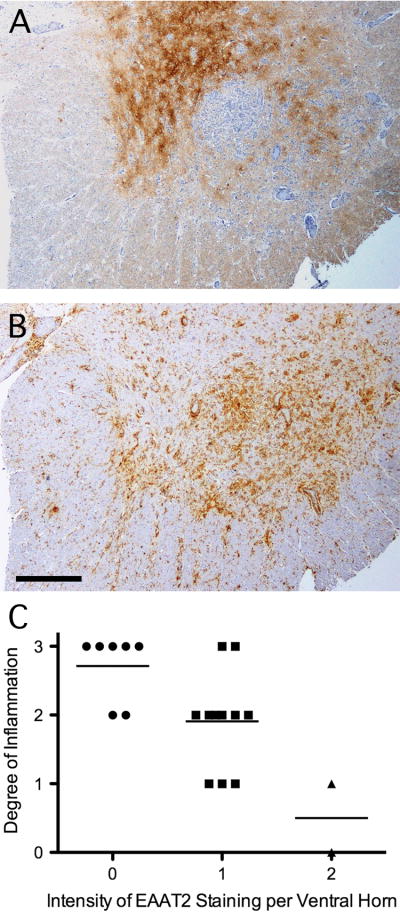

Topographical Localization of Excitatory Amino Acid Transporter-2 Expression in Relation to Inflammation

In vitro studies demonstrate that pro-inflammatory cytokines cause primary cultured astrocytes to lose their glutamate buffering capacity (26–29). To implicate the inflammatory response as a potential effector of diminished astroglial EAAT2 expression in WNV-induced AFP in vivo, we compared expression of class II major histocompatibility complex antigens (HLA-DR) and EAAT2 staining in serial sections. In WNV AFP showing patchy loss of EAAT2 expression in ventral grey matter (Fig. 6A), there was intense HLA-DR staining in regions in which transporter levels were prominently diminished (Fig. 6B). When the same fields in which diminished EAAT2 expression was analyzed in a semi-quantitative manner for overall inflammation, an inverse correlation between the intensity of EAAT2 staining and the magnitude of inflammatory cell infiltration was seen in the 4 WNV AFP cases (Fig. 6C). Although a cause-and-effect relationship remains unproven, these reciprocal expression patterns imply that local immune responses may be causally related to the loss of EAAT2 protein. A similar focal loss of EAAT2 expression has been reported in grey matter lesions of MS patients with inflammation (23). Thus, transporter changes that may be driven by the host immune response are not unique to WNV infection.

Figure 6.

A reciprocal topographical relationship between excitatory amino acid transporter-2 (EAAT2) expression and the local inflammatory response in the spinal cords of patients with West Nile virus (WNV)-induced acute flaccid paralysis (AFP). (A) Patchy loss of EAAT2 in some parts of grey matter. (B) Regions with the lowest residual EAAT2 expression have the most abundant HLA-DR expression in an adjacent section. (C) Semiquantitative assessment of the degree of cellular infiltration in the same high power microscope fields (n = 20) scored for EAAT2 expression in 4 cases of WNV AFP showed an inverse correlation between inflammation and relative EAAT2 staining. (A, B) Immunoperoxidase (brown) and hematoxylin (purple), scale bar: 500 μm.

DISCUSSION

Many conclusions about the pathogenesis of WNV-induced AFP come from autopsy studies that reveal losses of AHCs across multiple spinal levels. It is assumed that motor neurons are destroyed by direct virus-induced cell death (1–8). In patients with AFP who survive acute infection, however, AFP there can be a variable degree of clinical recovery over time (7, 8). This implies a spectrum of cellular events within the spinal cord, including ones that cause reversible dysfunction of motor pathways. Furthermore, studies in related animal models of mosquito-borne encephalomyelitis demonstrate bystander damage to uninfected AHCs via glutamate excitotoxicity (15–18). In these cases, neuronal injury is a result of defective astrocyte glutamate reuptake focally within spinal grey matter that is driven by the local inflammatory response (16, 18). If similarly complex processes underlie WNV-induced AFP, then an improved understanding of these events could suggest new therapeutic targets. We have identified reduced astroglial glutamate transporter expression and altered synaptic and dendritic networks in the spinal cords of AFP patients.

Our results indicate that EAAT2 expression diminishes in spinal grey matter during WNV-induced AFP, even as GFAP-positive cells increase in these same regions. Since reduced EAAT levels occur in the spinal grey matter of patients with ALS (21, 22), glutamate excitotoxicity remains a favored mechanism to explain the AHC loss that occurs with this disorder (30). Beyond chronic neurodegeneration, however, recent studies also show that astrocyte EAAT expression declines in active MS lesions and in the spinal grey matter of rodents with the related demyelinating disorder, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) (23, 31). EAE studies indicate that glutamate excitotoxicity contributes to disease pathogenesis (31–33), strongly suggesting the astrocytic responses are significant. Altered astroglial EAAT2 expression has also been reported in CNS viral infections caused by HIV and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), thereby further expanding the potential involvement of glutamate transporter dysfunction in neuroinflammatory disorders (34, 35). As more direct evidence of such involvement, drugs that enhance GLT-1 expression in the spinal cord also protect vulnerable AHC and prevent paralysis during viral encephalomyelitis caused by NSV, without altering virus tropism or clearance (14). High throughput screens have now identified multiple compounds that are approved for use in humans and that offer neuroprotection in the spinal cord by enhancing astroglial glutamate reuptake (36). Thus, diminished astroglial glutamate transport is relevant to the pathogenesis of both infectious and inflammatory disorders of the CNS and represents an emerging therapeutic target for many of these diseases.

Relatively little is known about the mechanisms through which local inflammation blunts the ability of astrocytes to take up extracellular glutamate. Prior studies demonstrate that primary astrocytes cultured in vitro show diminished EAAT expression and a reduced capacity to internalize radiolabeled glutamate following direct exposure to various pro-inflammatory cytokines, although such cells also lose their glutamate buffering capacity with repeated in vitro passage (26–29). In EAE, treatment of mice with glutamate receptor blocking drugs that reduces disease severity also prevents decline in astroglial GLT-1 levels, suggesting that glutamate itself somehow contributes to diminished transporter expression (31). Among NSV-infected mice, spinal cord expression of GLT-1 is preserved in interleukin1-β-deficient animals compared to controls, highlighting the importance of this inflammatory mediator in causing the defective astroglial glutamate transport that occurs with this disease (18). In the few animals that survive the acute stages of this infection, resolution of spinal cord inflammation is associated with a return of GLT-1 expression (16). Taken together, these findings implicate particular inflammatory elements in driving the loss of astrocyte EAAT expression in the spinal cord. They also indicate how blockade of pathogenic host responses can be neuroprotective by preserving this important homeostatic function of astrocytes.

In the hamster model of WNV-induced AFP, neuronal injury in the spinal cord is much more widespread than can be accounted for by direct infection of neurons (24). This indicates that (as in the NSV model [13, 18]) bystander injury to uninfected neurons likely contributes to disease pathogenesis. Given the declining astrocyte GLT-1 expression we observed in the cords of these WNV-infected animals (Fig. 4), excitotoxicity could be an important contributor to this bystander neuronal damage. The similar transporter changes that occur in humans with WNV-induced AFP bolster the clinical relevance of this finding (Figs. 2, 3). Evidence supporting a role for the host response in causing these changes during WNV myelitis remains indirect, but the greatest transporter loss occurs in precisely the same regions of spinal grey matter that have the most local inflammation (Fig. 6). Together, these findings generate new hypotheses that can be explored in this model.

Finally, the reduced number of synaptic contacts surrounding many remaining AHCs in the spinal cords of patients with WNV-induced AFP (Fig. 5A–D) offers an attractive explanation for the reversible motor deficits that may occur in survivors of this infection (7, 8). Synaptic “stripping” has been observed in experimental inflammatory brain lesions, and such changes are both reversible and not associated with neuronal damage, suggesting that they may actually be neuroprotective (37). During EAE, retraction of synaptic contacts adjoining AHCs in the lumbar spinal cord correlates closely with the onset of hind limb paralysis, while clinical recovery is temporally associated with a reestablishment of these synaptic connections (38, 39). Not only do these data confirm the reversibility of this event in the spinal cord, but they also provide an explanation for the return of motor function. In AFP, by reducing excitatory synapses immediately adjacent to those AHCs with the most abnormal morphology (Fig. 5A–D), the host may be attempting to lower the exposure of these cells to glutamate thus enhancing their likelihood of survival. Further study will be required to understand the molecular mechanisms and clinical implications of these synaptic events.

In conclusion, our observations support a model in which the spread of WNV to the spinal cord triggers host responses that are a proximal cause of diminished expression of the astroglial glutamate transporter, GLT-1/EAAT2. A corresponding rise in local extracellular glutamate levels (as occurs in experimental animals when expression of this protein is knocked down [19]) is then injurious to both infected and uninfected AHCs that express abundant glutamate receptors. In response to these events, the response may be an attempt to compensate by retracting some of the synaptic contacts from the remaining AHCs, potentially reestablishing them if the target cell survives the acute injury. If confirmed, targeting immune responses or the glutamate receptors present on AHCs may offer a novel therapeutic approach for patients with WNV-induced AFP.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Charles A. Dana Foundation (DNI) and by National Institutes of Health Grant, AI057505 (DNI).

We wish to thank Dr. Carlos Pardo-Villamizar for providing us with the control human spinal cord tissue sections used in these studies. Dr. John Morrey graciously provided us with the control and WNV-infected hamster spinal cord tissue sections.

References

- 1.Davis LE, DeBiasi R, Goade DE, et al. West Nile virus neuroinvasive disease. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:286–300. doi: 10.1002/ana.20959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeBiasi RL, Tyler KL. West Nile virus meningoencephalitis. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006;5:264–75. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doron SI, Dashe JF, Adelman LS, et al. Histopathologically proven poliomyelitis with quadriplegia and loss of brainstem function due to West Nile virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:374–77. doi: 10.1086/377177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sejvar JJ, Leis A, Stokic D, et al. Acute flaccid paralysis and West Nile virus infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:788–93. doi: 10.3201/eid0907.030129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leis A, Stokic D, Webb R, et al. Clinical spectrum of muscle weakness in human West Nile virus infection. Muscle Nerve. 2003;28:302–8. doi: 10.1002/mus.10440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sejvar JJ, Bode AV, Marfin AA, et al. West Nile virus-associated acute flaccid paralysis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1021–27. doi: 10.3201/eid1107.040991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sejvar JJ, Haddad M, Tierney B, et al. Neurologic manifestations and outcome of West Nile virus infection. JAMA. 2003;290:511–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.4.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao NJ, Ranganathan C, Kupsky WJ, et al. Recovery and prognosticators of paralysis in West Nile virus infection. J Neurol Sci. 2005;236:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson RT, McFarland HF, Levy SE. Age-dependent resistance to viral encephalitis: Studies of infections due to Sindbis virus in mice. J Infect Dis. 1972;125:257–62. doi: 10.1093/infdis/125.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aguilar MJ. Pathological changes in brain and other target organs of infant and weanling mice after infection with non-neuroadapted western equine encephalitis virus. Infect Immun. 1970;2:533–42. doi: 10.1128/iai.2.5.533-542.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Havert MB, Schofield B, Griffin DE, Irani DN. Activation of divergent neuronal cell death pathways in different target cell populations during neuroadapted Sindbis virus infection of mice. J Virol. 2000;74:5352–56. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.11.5352-5356.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nargi-Aizenman JL, Griffin DE. Sindbis virus-induced neuronal death is both necrotic and apoptotic and is ameliorated by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists. J Virol. 2001;75:7114–21. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.7114-7121.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irani DN, Prow NA. Neuroprotective interventions targeting detrimental host immune responses protect mice from fatal alphavirus encephalitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:533–44. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000263867.46070.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prow NA, Irani DN. The opioid receptor antagonist, naloxone, protects spinal motor neurons in a murine model of alphavirus encephalomyelitis. Exp Neurol. 2007;205:461–70. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nargi-Aizenman JL, Havert MB, Zhang M, et al. Glutamate receptor antagonists protect from virus-induced neural degeneration. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:541–49. doi: 10.1002/ana.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darman J, Backovic S, Dike S, et al. Viral-induced spinal motor neuron death is non-cell-autonomous and involves glutamate excitotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7566–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2002-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greene IP, Lee EY, Prow N, et al. Protection from fatal viral encephalomyelitis: AMPA receptor antagonists have a direct effect on the inflammatory response to infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3575–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712390105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prow NA, Irani DN. The inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-1 beta, mediates loss of astroglial glutamate transport and drives excitotoxic motor neuron injury in the spinal cord during acute viral encephalomyelitis. J Neurochem. 2008;105:1276–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothstein JD, Dykes-Hoberg M, Pardo CA, et al. Knockout of glutamate transporters reveals a major role for astroglial transport in excitotoxicity and clearance of glutamate. Neuron. 1996;16:675–86. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka K, Watase K, Manabe T, et al. Epilepsy and exacerbation of brain injury in mice lacking the glial glutamate transporter GLT-1. Science. 1997;276:1699–1702. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothstein JD, Van Kammen M, Levey AI, et al. Selective loss of glial glutamate transporter GLT-1 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:73–84. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasaki S, Komori T, Iwata M. Excitatory amino acid transporter 1 and 2 immunoreactivity in the spinal cord in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2000;100:138–44. doi: 10.1007/s004019900159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vercellino M, Merola A, Piacentino C, et al. Altered glutamate reuptake in relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis cortex: correlation with microglia infiltration, demyelination, and neuronal and synaptic damage. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:732–39. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31812571b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samuel MA, Wang H, Siddharthan V, et al. Axonal transport mediates West Nile virus entry into the central nervous system and induces acute flaccid paralysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:17140–45. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705837104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhatnagar J, Guarner J, Paddock CD, et al. Detection of West Nile virus in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human tissues by RT-PCR: A useful adjunct to conventional tissue-based diagnostic methods. J Clin Virol. 2007;38:1106–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye ZC, Sontheimer H. Cytokine modulation of glial glutamate uptake: A possible involvement of nitric oxide. Neuroreport. 1996;7:2181–85. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199609020-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szymocha R, Akaoka H, Dutuit M, et al. Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1-infected lymphocytes impair catabolism and uptake of glutamate by astrocytes via Tax-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Virol. 2000;74:6433–41. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6433-6441.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z, Pekarskava O, Bencheikh M, et al. Reduced expression of glutamate transporter EAAT2 and impaired glutamate transport in human primary astrocytes exposed to HIV-1 or gp120. Virology. 2003;20:60–73. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tilleux S, Hermans E. Neuroinflammation and regulation of glial glutamate uptake in neurological disorders. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:2059–70. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Damme P, Dewil M, Robberecht W, et al. Excitotoxicity and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurodegener Dis. 2005;2:147–59. doi: 10.1159/000089620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohgoh M, Hanada T, Smith T, et al. Altered expression of glutamate transporters in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;125:170–78. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith T, Groom A, Zhu B, et al. Autoimmune encephalomyelitis ameliorated by AMPA antagonists. Nat Med. 2000;6:62–66. doi: 10.1038/71548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitt D, Werner P, Raine CS. Glutamate excitotoxicity in a model of multiple sclerosis. Nat Med. 2000;6:67–70. doi: 10.1038/71555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fotheringham J, Wiliams EL, Akhyani N, Jacobson S. Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) induces dysregulation of glutamate uptake and transported expression in astrocytes. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2008;3:105–16. doi: 10.1007/s11481-007-9084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xing HQ, Hayakawa H, Gelpi E, et al. Reduced expression of excitatory amino acid transporter 2 and diffuse microglial activation in the cerebral cortex in AIDS cases with or without HIV encephalitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:199–209. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31819715df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rothstein JD, Patel S, Regan MR, et al. Beta-lactam antibiotics offer neuroprotection by increasing glutamate transporter expression. Nature. 2005;433:73–77. doi: 10.1038/nature03180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trapp BD, Wujek JR, Criste JA, et al. Synaptic stripping by cortical microglia. Glia. 2007;55:360–68. doi: 10.1002/glia.20462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marques KB, Santos LM, Oliveira AL. Spinal motoneuron synaptic plasticity during the course of an animal model of multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:3053–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu B, Luo L, Moore GR, et al. Dendritic and synaptic pathology in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1639–50. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64298-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]