The ribosome-bound initiation factor 2 recruits initiator tRNA to the 30S initiation complex

Bacterial translation initiation factor 2 (IF2) promotes the binding of the initiator tRNA to the small ribosomal subunit. Work by Rodnina and colleagues shows that - in contrast to what is often assumed - IF2·GTP binds to the 30S ribosomal subunit prior to and independent of fMet-tRNAfMet; ribosome-bound IF2 promotes initiator tRNA binding by providing anchoring interactions and/or inducing a favourable ribosome conformation. Thus, the mechanism of IF2 function differs from that of tRNA carriers such as EF-Tu, SelB, and eukaryotic initiation factor eIF2, but instead resembles eIF5B, the eukaryotic subunit association factor.

Keywords: GTPase, FRET, rapid filtration, stopped-flow fluorescence

Abstract

Bacterial translation initiation factor 2 (IF2) is a GTPase that promotes the binding of the initiator fMet-tRNAfMet to the 30S ribosomal subunit. It is often assumed that IF2 delivers fMet-tRNAfMet to the ribosome in a ternary complex, IF2·GTP·fMet-tRNAfMet. By using rapid kinetic techniques, we show here that binding of IF2·GTP to the 30S ribosomal subunit precedes and is independent of fMet-tRNAfMet binding. The ternary complex formed in solution by IF2·GTP and fMet-tRNA is unstable and dissociates before IF2·GTP and, subsequently, fMet-tRNAfMet bind to the 30S subunit. Ribosome-bound IF2 might accelerate the recruitment of fMet-tRNAfMet to the 30S initiation complex by providing anchoring interactions or inducing a favourable ribosome conformation. The mechanism of action of IF2 seems to be different from that of tRNA carriers such as EF-Tu, SelB and eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2), instead resembling that of eIF5B, the eukaryotic subunit association factor.

Introduction

Bacterial translation initiation is a multistep process, which requires initiation factor 1 (IF1), IF2 and IF3. In the first phase of initiation, IF1, IF2 (a GTP-binding protein), IF3, mRNA and the initiator fMet-tRNAfMet bind to the 30S ribosomal subunit, forming the 30S initiation complex (30S IC). In the second phase, the 50S subunit joins the 30S IC, GTP is hydrolyzed, the initiation factors dissociate and fMet-tRNAfMet is positioned in the P site of the resulting 70S IC. After binding of the first aminoacyl-tRNA and formation of the first peptide bond, the 70S IC enters the elongation cycle of translation (Gualerzi et al, 2001; Laursen et al, 2005). IF2·GTP promotes the binding of fMet-tRNAfMet to ribosomes (reviewed in Laursen et al, 2005). By analogy with other translational GTPases—for example, EF-Tu, SelB and eukaryotic initiation factor-2 (eIF2)—that deliver aminoacylated tRNAs to the ribosome, it is often assumed that IF2 also transports the initiator tRNA to the 30S subunit (Hershey & Merrick, 2000). Indeed, IF2 and EF-Tu show some sequence homology, are both GTP-binding proteins and can form ternary complexes with aminoacyl-tRNAs (the initiator or elongator, respectively) and GTP. Furthermore, a correlation between the affinity for IF2 shown by initiator tRNAs carrying formylated amino acids other than methionine and their binding to the ribosome could be interpreted as supporting the ‘tRNA carrier' model for IF2 (Wu & RajBhandary, 1997). This view is supported further by the analogy that can be drawn between prokaryotic IF2 and eukaryotic eIF2, the latter being a eukaryotic initiator tRNA (Met-tRNAi) carrier (Hershey & Merrick, 2000). By contrast, early kinetic studies of a model system showed that IF2 stimulated the binding of AcPhe-tRNAPhe to poly(U)-programmed 30S subunits by binding to the 30S subunit before the binding of the tRNA (Wintermeyer & Gualerzi, 1983; Gualerzi & Wintermeyer, 1986), arguing against IF2 being an fMet-tRNAfMet carrier. Analogous experiments with natural initiation substrates are not available. In this paper, the role of IF2 in promoting the binding of fMet-tRNAfMet to the 30S subunit is addressed by rapid kinetics, monitoring the formation of the complex between IF2·GTP, fMet-tRNAfMet and the 30S subunit.

Results And Discussion

Pathways of 30S initiation complex formation

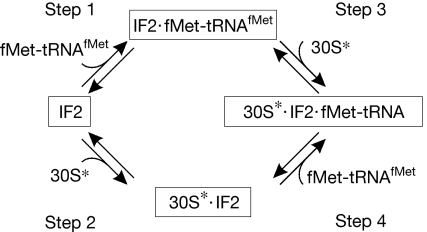

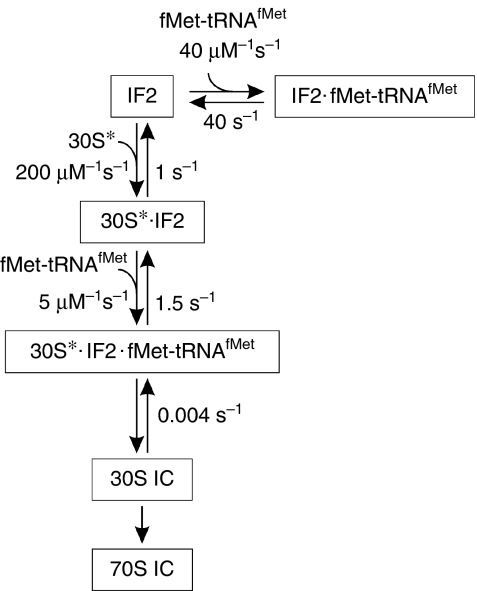

fMet-tRNAfMet might be delivered to the 30S subunit by one of two pathways (Fig 1): it could form the ternary complex IF2·GTP·fMet-tRNAfMet (step 1), which then binds to the mRNA-programmed 30S·IF1·IF3 (30S*) complex (step 3), or IF2·GTP could bind to the 30S* complex (step 2) and promote fMet-tRNAfMet binding (step 4). To evaluate the extent to which the two pathways are used in 30S IC formation, the rate constants of the four reactions were determined by using rapid kinetic techniques.

Figure 1.

A scheme of the interactions between IF2·GTP, fMet-tRNAfMet and the complex 30S·mRNA·IF1·IF3 (denoted as 30S*). GTP bound to IF2 is omitted for simplicity. fMet-tRNAfMet can bind to the 30S* complex in the ternary complex with IF2·GTP (steps 1/3 pathway) or to the IF2·GTP·30S* complex (steps 2/4 pathway). IF, initiation factor.

Formation of the IF2·GTP·fMet-tRNAfMet complex

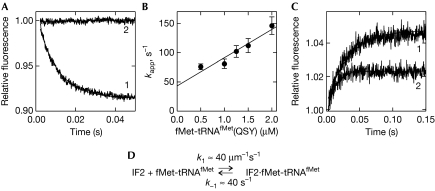

The interaction between IF2 and fMet-tRNAfMet (step 1; Fig 1) was studied by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between IF2 labelled at Cys 599 with Atto465 (IF2(Atto)) as the donor and fMet-tRNAfMet labelled with a non-fluorescent acceptor, QSY35, at thioU8 (fMet-tRNAfMet(QSY); Milon et al, 2008; see Methods). Neither label caused any appreciable loss of activity in 30S IC formation, as measured by nitrocellulose filtration. The quenching of the Atto fluorescence by FRET to QSY that was observed on mixing IF2(Atto)·GTP with fMet-tRNAfMet(QSY) indicated the formation of the ternary complex (Fig 2A). The rate constants were determined from the linear concentration dependence of the kapp of ternary complex formation (Fig 2B). The value of k−1 was also determined from dissociation experiments, which were performed by mixing IF2(Atto)·GTP·fMet-tRNAfMet(QSY) with excess unlabelled IF2 (Fig 2C, trace-1). In a further experiment, dissociation of the complex was induced by dilution (Fig 2C, trace-2) and the time courses were evaluated by numeric integration. With all three approaches, k1≈40 μM−1 s−1 and k−1≈40 s−1 were obtained (Fig 2D). The concentration dependence of the fluorescence change amplitude yielded Kd=1.0 μM (supplementary Fig S1 online), the same value as calculated from the k1 and k−1. Thus, the ternary complex formed of IF2·GTP and fMet-tRNAfMet is relatively weak and kinetically unstable.

Figure 2.

The kinetics of IF2·GTP·fMet-tRNAfMet complex formation. (A) Binding of IF2(Atto) (0.2 μM) with GTP (0.25 mM) to fMet-tRNAfMet(QSY) (2 μM; trace-1) or to unlabelled fMet-tRNAfMet (2 μM; trace-2). (B) Concentration dependence of kapp. Values of kapp were estimated by one-exponential fitting of the time courses obtained at increasing concentrations of fMet-tRNAfMet(QSY). Linear regression yielded k1=48±8 μM−1 s−1 and k−1=43±10 s−1, assuming a one-step binding model. (C) Dissociation of the IF2·GTP·fMet-tRNAfMet complex. IF2(Atto) (0.2 μM) and fMet-tRNAfMet(QSY) (1 μM) were pre-incubated and mixed with unlabelled IF2 (2 μM; trace-1) or buffer A (trace-2) in the presence of GTP (0.25 mM). Exponential fitting of trace-1 gives k−1=40±5 s−1. Numerical integration (continuous lines) yielded k1=40±3 μM−1 s−1 and k−1=38±2 s−1, assuming a one-step binding model. (D) The kinetic parameters of ternary complex formation. IF, initiation factor.

Binding of IF2 to the 30S* complex

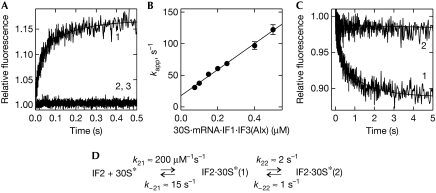

Binding of IF2·GTP to the 30S* complex was followed by monitoring FRET between IF2(Atto) and Alexa555-labelled IF3 (IF3(Alx); Milon et al, 2008). A biphasic fluorescence increase was observed (Fig 3A), indicating a two-step binding of IF2 to the 30S* complex. The apparent rate constants of the first and second step are referred to as kapp21 and kapp22, and the forward and backward rate constants as k21, k−21, k22 and k−22, respectively. The concentration dependence of kapp21 (Fig 3B) yielded k21=200±20 μM−1 s−1 and k−21=15±3 s−1. The value of kapp22 (≈3 s−1) was independent of concentration, indicating a mechanism in which binding (reflected by kapp21) is followed by slow rearrangement. As kapp21≫kapp22, the approximation kapp22≈k22+k−22 can be used. To determine k−22, chase experiments were performed monitoring FRET changes that occurred on mixing 30S·mRNA·IF1·IF2(Atto)·IF3(Alx) with an excess of unlabelled IF2·GTP (Fig 3C). The resulting dissociation rate constant (k−22) was about 1 s−1, hence k22≈2 s−1 (Fig 3D), which gives a Kd≈40 nM for 30S*·IF2·GTP. This value is consistent with that obtained from the concentration dependence of the total fluorescence amplitude (data not shown) and with the value estimated from co-sedimentation experiments (Caserta et al, 2006). Thus, in the absence of fMet-tRNAfMet, IF2·GTP binds rapidly and tightly to the 30S* complex.

Figure 3.

IF2 binding to the 30S* complex. (A) The time course of IF2(Atto) (0.025 μM) binding to the 30S subunit (0.075 μM) in the presence of mRNA (0.75 μM), IF1 (0.75 μM), IF3(Alx) (0.75 μM) and GTP (0.25 mM; trace-1). Controls were performed with unlabelled IF2 (acceptor only, trace-2) or unlabelled IF3 (donor only, trace-3). Binding was monitored by FRET from IF2(Atto) to IF3(Alx). kapp21=30±3 s−1 and kapp22=3±0.3 s−1 were estimated by two-exponential fitting. (B) The concentration dependence of kapp21. IF2(Atto) (0.025 μM) was mixed with the 30S* complex at increasing concentrations. The rate constants k21=200±20 μM−1 s−1 and k−21=15±3 s−1 were obtained from the linear fit. (C) Dissociation of IF2(Atto) (0.025 μM) from the 30S·mRNA·IF1·IF3(Alx) complex (0.25 μM) on mixing with unlabelled IF2 (2 μM; trace-1) or buffer A (trace-2). Dissociation rate constant k−22=1±0.1 s−1. (D) The two-step binding mechanism. FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; IF, initiation factor.

The pathway of fMet-tRNAfMet binding to the 30S subunit

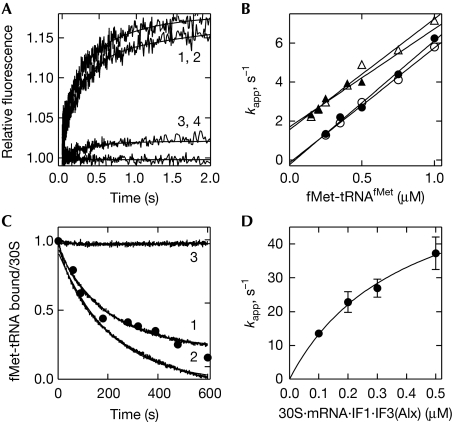

As IF2·GTP can bind to either fMet-tRNAfMet or to the 30S* complex, the relative use of these alternative pathways depends on the relative efficiency of steps 3 and 4 (Fig 1). To determine which pathway is favoured, the following experiments were performed. To monitor step 3, fMet-tRNAfMet was preincubated with IF2·GTP and mixed with the 30S* complex. For monitoring step 4, fMet-tRNAfMet was mixed with 30S*·IF2·GTP. Binding of fMet-tRNAfMet was monitored by FRET between fluorescein (Flu)-labelled fMet-tRNAfMet and IF3(Alx) (Fig 4A; supplementary Fig S2A online; Milon et al, 2008) and by rapid filtration using 35S-labelled fMet-tRNAfMet (supplementary Fig S2B online; Brandi et al, 2007). The two techniques yielded identical time courses, regardless of whether IF2 was prebound to the 30S subunit (supplementary Fig S2A,B online). The association rate constant estimated by linear fitting of the concentration dependence of kapp was 5 μM−1 s−1 (Fig 4B). The y-axis intercept was close to zero in the filtration experiment and about 1.5 s−1 in the FRET experiments, suggesting that different steps were monitored by the two techniques. The Kd value calculated from the kon and koff of the reaction monitored by FRET (0.3 μM) was close to that determined from the concentration dependence of the FRET amplitude (0.2 μM; supplementary Fig S2C online), but much higher than the Kd value in the subnanomolar range estimated from the filter binding experiments (Antoun et al, 2006b). This suggests that binding of fMet-tRNAfMet to the 30S subunit takes place in at least two steps: a bimolecular binding step (reported by FRET) followed by tRNA adjustments on the 30S subunit, which are not reported by FRET but contribute to the overall affinity measured by filtration. Nevertheless, the rate of fMet-tRNAfMet binding to the 30S* complex did not change when the tRNA was preincubated with IF2·GTP or added directly to 30S*·IF2·GTP.

Figure 4.

The kinetics of fMet-tRNAfMet binding to the 30S subunit. (A) The time courses of fMet-tRNAfMet binding to the 30S* complex. IF2 (0.15 μM, concentrations after mixing) was preincubated with fMet-tRNAfMet(Flu) (0.5 μM) and GTP (0.5 mM), and mixed with 30S subunits (0.075 μM), mRNA (0.3 μM), IF1 (0.15 μM), IF3(Alx) (0.15 μM) and GTP (0.5 μM; trace-1). Alternatively, fMet-tRNAfMet(Flu) was mixed with 30S*·IF2·GTP (trace-2). Controls were performed with unlabelled fMet-tRNAfMet (acceptor only, trace-3) or unlabelled IF3 (donor only, trace-4). (B) The concentration dependence of fMet-tRNAfMet binding to the 30S* complex. Closed symbols, IF2 preincubated with fMet-tRNAfMet; open symbols, IF2 preincubated with the 30S* complex; circles, rapid filtration; triangles, stopped-flow. (C) Dissociation of fMet-tRNAfMet from the 30S IC. The complex was formed by incubation of 30S subunits (0.05 μM) with 002mRNA (0.2 μM), IF1 (0.1 μM), IF2 (0.1 μM), IF3(Alx) (0.1 μM), f[3H]Met-tRNAfMet(Flu) (0.15 μM) and GTP (0.25 mM). FRET was monitored from f[3H]Met-tRNAfMet(Flu) to IF3(Alx). Exchange of f[3H]Met-tRNAfMet(Flu) was induced by the addition of unlabelled fMet-tRNAfMet (2.25 μM) alone (trace-1) or together with IF2 (2 μM; trace-2). In the control experiment, buffer A was added (trace-3). Closed circles, 30S-bound f[3H]Met-tRNAfMet determined by nitrocellulose filtration. Single-exponential fitting (trace-1/2) yielded a dissociation rate constant of 0.004±0.001 s−1. (D) The concentration dependence of binding to the 30S* complex of IF2·GTP (0.05 μM) preincubated with fMet-tRNAfMet (1.5 μM). FRET was monitored from IF2(Atto) to IF3(Alx). In addition, a fast binding step was observed due to binding of free IF2 to the 30* complex (data not shown). FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; IC, initiation complex; IF, initiation factor.

The dissociation rate constant of the complete 30S IC was estimated from the FRET changes observed on the addition of excess unlabelled fMet-tRNAfMet—with or without IF2—to 30S IC containing IF3(Alx) and fMet-tRNAfMet(Flu) (Fig 4C). When fMet-tRNAfMet was added alone, only tRNA was exchanged, and the observed rate reflected the dissociation rate constant of step 4, k−4, which was 0.004 s−1 (Fig 1). The same value was obtained when fMet-tRNAfMet and IF2 were added together (Fig 4C), suggesting that either the dissociation proceeds through step 3 (k−3) or k−4 is similar to k−3.

IF2 binds to 30S* prior to initiator tRNA

The above results would be consistent with two models: either the two pathways (Fig 1) are equivalent (that is, k3 is comparable to k4 and k−3 to k−4, and the equilibrium binding constants K3 and K4 are equal), or the pathways are not equivalent, and one is favoured regardless of the order of addition. As the Kd values of steps 1 (1 μM) and 2 (40 nM) are different, the Kd values of steps 3 and 4 must differ by the same factor; thus, the two pathways cannot be equivalent and so the question is, which one is favoured kinetically? One potential scenario is that IF2·GTP dissociates from 30S*·IF2·GTP (step 2), binds to fMet-tRNAfMet (step 1) and delivers it to the 30S complex (step 3). In such a case, however, binding of fMet-tRNAfMet to the 30S subunit would be rate-limited by the dissociation of IF2·GTP from the 30S complex, giving rise to a concentration-independent step with a rate of 1 s−1 (Fig 3D), which is not observed (Fig 4B). Conversely, if the pathway through steps 2 and 4 was favoured, the ternary complex IF2·GTP·fMet-tRNAfMet would have to dissociate (step 1) before IF2 can bind to the 30S* complex; that is, the rate of IF2 binding to the 30S* complex would be limited to about 40 s−1. To test this, the rate of IF2 binding to the 30S* complex was measured with the preformed IF2(Atto)·GTP·fMet-tRNAfMet complex, monitoring FRET between IF2(Atto) and IF3(Alx) (Fig 4D). Under these conditions, the rate of IF2 binding to the 30S* complex was about 10 times higher than that of fMet-tRNAfMet, suggesting that IF2 and fMet-tRNAfMet bind to the ribosome independently of one another. Unlike the binding of free IF2 to the 30S* complex, which showed linear concentration dependence (Fig 3), the rate of IF2 binding from the ternary complex was extrapolated to saturate at about 50 s−1 (Fig 4D). This rate is comparable to the dissociation rate constant of IF2·GTP·fMet-tRNAfMet, indicating that the overall reaction proceeds through steps 1 (dissociation), 2 and 4 (Fig 5).

Figure 5.

The pathway of IF2·GTP and fMet-tRNAfMet binding to the 30S* complex. The main pathway is shown vertically. The formation of the ternary complex IF2·GTP·fMet-tRNAfMet, which is probably an insignificant side reaction under normal conditions, might take place under conditions of 30S subunit shortage, perhaps acting as a storage complex. IC, initiation complex; IF, initiation factor.

The results of the kinetic analysis clearly favour a scenario in which IF2·GTP binds to the 30S subunit first, promoting fMet-tRNAfMet binding by providing essential anchoring interactions or inducing a favourable conformation of the 30S subunit (Canonaco et al, 1986). This conclusion agrees with the results of previous experiments performed with model components (Wintermeyer & Gualerzi, 1983; Gualerzi & Wintermeyer, 1986) and argues against IF2 acting as a carrier for fMet-tRNAfMet. In fact, the genuine tRNA carriers—EF-Tu, SelB and eIF2—form tight complexes with the tRNAs that they transport, with Kd values in the nM or even the pM range (Paleskava et al, 2009), whereas the complex of fMet-tRNAfMet with IF2·GTP is weak (Kd≈1 μM) and kinetically unstable. Another important difference is that IF2 binds to the 30S subunit independently of fMet-tRNAfMet, whereas Met-tRNAi and elongator aminoacyl-tRNAs are delivered to the ribosome in ternary complexes with their respective factors and GTP (Kapp & Lorsch, 2004). IF2 seems to function differently from the factors that carry their respective aminoacyl-tRNAs to the ribosome. Instead, IF2 functionally resembles its structural homologue eIF5B. IF2 is known to promote the joining of the 50S subunit to the 30S IC (Grunberg-Manago et al, 1975; Antoun et al, 2006a; Milon et al, 2008). Similarly to IF2, eIF5B accelerates the joining of the ribosomal subunits (Acker et al, 2009), but hardly binds free Met-tRNAi to an appreciable extent: Kd>5 μM (Shin et al, 2002); Kd=40 μM (Guillon et al, 2005). Whereas the common activity of eIF5B and IF2 in accelerating subunit joining was conserved in evolution, the ability to protect initiator tRNA has been lost by eIF5B, perhaps because in eukaryotes this function was taken over by eIF2, which evolved to achieve efficient and accurate mRNA scanning. Cryo-electron microscopic reconstruction of the 30S initiation complex suggested that IF2 positions the acceptor end of fMet-tRNAfMet for insertion into the 50S subunit (Simonetti et al, 2008). The initiation factors and fMet-tRNAfMet bound to the 30S subunit form a surface landscape, which is favourable for 50S subunit joining and the following steps of translation initiation leading to the formation of the 70S IC.

Methods

Biochemical methods. Measurements were taken at 20°C in buffer A (50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 70 mM NH4Cl, 30 mM KCl and 7 mM MgCl2). Ribosomal subunits were prepared from purified 70S ribosomes by zonal centrifugation (Rodnina & Wintermeyer, 1995; Milon et al, 2007). 30S subunits were reactivated in buffer A with 20 mM MgCl2 for 1 h at 37°C. The activity of the reassociated 30S and 50S subunits was >95% in fMet-tRNAfMet binding and peptide bond formation. fMet-tRNAfMet was purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (Milon et al, 2007) and was 95% aminoacylated and formylated. mRNA was prepared by T7 RNA polymerase transcription or purchased from Microsynth (Microsynth AG, Balgad, Switzerland); unless stated otherwise, mRNA derived from 022mRNA was used (Milon et al, 2007). Preparation of single-cysteine mutants of IF2 and IF3 and fluorescence labelling of mutant factors and fMet-tRNA were performed as described by Milon et al (2007). 30S initiation complexes were formed by incubating 30S subunits with a twofold excess of IF1 and IF3, and a fourfold excess of mRNA in buffer A containing 0.25 mM GTP for 30 min at 37°C. IF2 and fMet-tRNAfMet were added as indicated in the figure legends. The extent of f[3H]Met-tRNAfMet or f[35S]Met-tRNAfMet binding to 30S subunits was measured by nitrocellulose filtration.

Kinetic experiments. Rapid filtration experiments were performed by using a Bio-Logic SFM-400 apparatus (Biologic SA, Grenoble, France; Brandi et al, 2007). Stopped-flow measurements were performed by using the SX-20 MV stopped-flow apparatus (Applied Photophysics, Leatherhead, UK) and rapidly mixing equal volumes (60 μl each) of reactants at 20°C. Atto465 and fluorescein were excited at 465 nm. Fluorescence emission was measured after passing cut-off filters (Schott AG, Mainz, Germany) KV590 for Alexa555 and KV500 for Atto465. Time courses (1,000 data points each, acquired in logarithmic sampling mode) were measured at pseudo-first-order conditions and were evaluated by fitting an exponential function, F=F∞+A × exp(−kapp × t), with a time constant (kapp), the amplitude of the signal change (A), the final signal (F∞) and the fluorescence signal at time t (F). If necessary, additional exponential terms were included. Calculations were performed by using the TableCurve software (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA) or Prism (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Standard deviations of all values were calculated from 7–10 time courses.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Schillings, A. Böhm and S. Möbitz for expert technical assistance. The work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (MVR) and the Italian Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Universìtà e della Ricerca (PRIN 2007 to COG).

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Acker MG, Shin BS, Nanda JS, Saini AK, Dever TE, Lorsch JR (2009) Kinetic analysis of late steps of eukaryotic translation initiation. J Mol Biol 385: 491–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoun A, Pavlov MY, Lovmar M, Ehrenberg M (2006a) How initiation factors maximize the accuracy of tRNA selection in initiation of bacterial protein synthesis. Mol Cell 23: 183–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoun A, Pavlov MY, Lovmar M, Ehrenberg M (2006b) How initiation factors tune the rate of initiation of protein synthesis in bacteria. EMBO J 25: 2539–2550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandi L, Fabbretti A, Milon P, Carotti M, Pon CL, Gualerzi CO (2007) Methods for identifying compounds that specifically target translation. Methods Enzymol 431: 229–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canonaco MA, Calogero RA, Gualerzi CO (1986) Mechanism of translational initiation in prokaryotes. Evidence for a direct effect of IF2 on the activity of the 30S ribosomal subunit. FEBS Lett 207: 198–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caserta E, Tomsic J, Spurio R, La Teana A, Pon CL, Gualerzi CO (2006) Translation initiation factor IF2 interacts with the 30S ribosomal subunit via two separate binding sites. J Mol Biol 362: 787–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunberg-Manago M, Dessen P, Pantaloni D, Godefroy-Colburn T, Wolfe AD, Dondon J (1975) Light-scattering studies showing the effect of initiation factors on the reversible dissociation of Escherichia coli ribosomes. J Mol Biol 94: 461–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualerzi CO, Wintermeyer W (1986) Prokaryotic initiation factor 2 acts at the level of the 30S ribosomal subunit. A fluorescence stopped-flow study. FEBS Lett 202: 1–6 [Google Scholar]

- Gualerzi CO, Brandi L, Caserta E, Garofalo C, Lammi M, La Teana A, Petrelli D, Spurio R, Tomsic J, Pon CL (2001) Initiation factors in the early events of mRNA translation in bacteria. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 66: 363–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillon L, Schmitt E, Blanquet S, Mechulam Y (2005) Initiator tRNA binding by e/aIF5B, the eukaryotic/archaeal homologue of bacterial initiation factor IF2. Biochemistry 44: 15594–15601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey JW, Merrick WC (2000) Pathway and mechanism of initiation of protein synthesis. In Translational Control of Gene Expression, Sonenberg N, Hershey JW, Mathew MB (eds) pp33–88. Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory [Google Scholar]

- Kapp LD, Lorsch JR (2004) GTP-dependent recognition of the methionine moiety on initiator tRNA by translation factor eIF2. J Mol Biol 335: 923–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen BS, Sorensen HP, Mortensen KK, Sperling-Petersen HU (2005) Initiation of protein synthesis in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 69: 101–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milon P, Konevega AL, Peske F, Fabbretti A, Gualerzi CO, Rodnina MV (2007) Transient kinetics, fluorescence, and FRET in studies of initiation of translation in bacteria. Methods Enzymol 430: 1–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milon P, Konevega AL, Gualerzi CO, Rodnina MV (2008) Kinetic checkpoint at a late step in translation initiation. Mol Cell 30: 712–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paleskava A, Konevega AL, Rodnina MV (2009) Thermodynamic and kinetic framework of selenocysteyl-tRNASec recognition by elongation factor SelB. J Biol Chem 285: 3014–3020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodnina MV, Wintermeyer W (1995) GTP consumption of elongation factor Tu during translation of heteropolymeric mRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 1945–1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin BS, Maag D, Roll-Mecak A, Arefin MS, Burley SK, Lorsch JR, Dever TE (2002) Uncoupling of initiation factor eIF5B/IF2 GTPase and translational activities by mutations that lower ribosome affinity. Cell 111: 1015–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonetti A, Marzi S, Myasnikov AG, Fabbretti A, Yusupov M, Gualerzi CO, Klaholz BP (2008) Structure of the 30S translation initiation complex. Nature 455: 416–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintermeyer W, Gualerzi C (1983) Effect of Escherichia coli initiation factors on the kinetics of N-AcPhe-tRNAPhe binding to 30S ribosomal subunits. A fluorescence stopped-flow study. Biochemistry 22: 690–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu XQ, RajBhandary UL (1997) Effect of the amino acid attached to Escherichia coli initiator tRNA on its affinity for the initiation factor IF2 and on the IF2 dependence of its binding to the ribosome. J Biol Chem 272: 1891–1895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.