Abstract

Slit–Roundabout (Robo) signalling has a well-understood role in axon guidance1–5. Unlike in the nervous system, however, Slitdependent activation of an endothelial-specific Robo, Robo4, does not initiate a guidance program. Instead, Robo4 maintains the barrier function of the mature vascular network by inhibiting neovascular tuft formation and endothelial hyperpermeability induced by pro-angiogenic factors 6. In this study, we used cell biological and biochemical techniques to elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying the maintenance of vascular stability by Robo4. Here, we demonstrate that Robo4 mediates Slit2-dependent suppression of cellular protrusive activity through direct interaction with the intracellular adaptor protein paxillin and its paralogue, Hic-5. Formation of a Robo4–paxillin complex at the cell surface blocks activation of the small GTPase Arf6 and, consequently, Rac by recruitment of Arf-GAPs (ADP-ribosylation factor- directed GTPase-activating proteins) such as GIT1. Consistent with these in vitro studies, inhibition of Arf6 activity in vivo phenocopies Robo4 activation by reducing pathologic angiogenesis in choroidal and retinal vascular disease and VEGF-165 (vascular endothelial growth factor-165)-induced retinal hyperpermeability. These data reveal that a Slit2–Robo4–paxillin–GIT1 network inhibits the cellular protrusive activity underlying neovascularization and vascular leak, and identify a new therapeutic target for ameliorating diseases involving the vascular system.

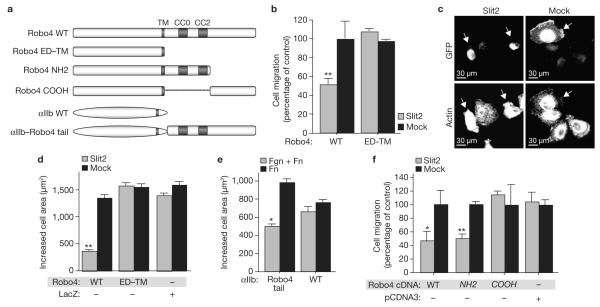

In both developmental and pathologic settings, cells migrate by orienting protrusive events in response to attractive and repulsive cues. Slit2–Robo4 signalling has been shown previously to inhibit migration of cells towards a soluble chemoattractant gradient7,8. In addition to chemoattractants, immobilized extracellular matrix proteins, such as fibronectin, have a critical role in regulating cellular motility during development and disease9, and gradients of fibronectin direct migration in a process called haptotaxis. We determined whether Slit2–Robo4 signalling modulates extracellular matrix-driven motility, using HEK 293 cells expressing fulllength Robo4 or a cytoplasmic tail-domain deletion mutant containing only the ectodomain and the transmembrane domain (Robo4 ED–TM; Fig. 1a). We induced these cells to migrate to fibronectin in the absence (mock) and presence of Slit2, and found that Slit2 inhibited the motility of cells expressing Robo4, but not Robo4 ED–TM (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

The Robo4 cytoplasmic tail suppresses fibronectin-induced protrusive activity. (a) Schematic representation of cDNA constructs used in migration and spreading assays. TM, transmembrane domain. CC0 and CC2 are conserved cytoplasmic signalling motifs found in Robo family members. (b–d, f) HEK 293 cells expressing GFP and the indicated constructs were subjected to haptotaxis migration assays (b, f) or spreading assays (c, d) on fibronectin and mock or Slit2. Arrows indicate GFPpositive cells. (e) CHO-K1 cells stably expressing αIIb integrin or αIIb integrin–Robo4 cytoplasmic tail were subjected to spreading assays on fibronectin (Fn) or fibronectin and fibrinogen (Fn + Fgn). Cell area was determined using ImageJ software. For migration assays, GFP-positive cells on the underside of the filter were counted and migration on fibronectin or mock membranes was set at 100% (n = 3, in triplicate). For spreading assays, the area of GFP-positive cells was determined using ImageJ (n = 3,150 cells per experiment). Expression of Robo4 constructs was verified by immunoblotting (data not shown). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005. Error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m. WT, wild type. Mock, a sham preparation of Slit2. αIIb–Robo4, αIIb integrin–Robo4. pCDNA3, empty vector.

Migrating cells protrude in the forward direction and form new attachments to the extracellular matrix9. These newly formed attachments lead to adhesion-induced activation of the small GTPase Rac, which creates broad protrusive structures called lamellipodia through localized actin polymerization10. When detached cells adhere, adhesion-induced Rac activation leads to unpolarized lamellipodial extension, resulting in spreading11. As cell spreading is an integral part of migration on the extracellular matrix, we assessed whether Slit2–Robo4 signalling inhibits this process. We found that although cells expressing Robo4 adhered normally to fibronectin and Slit2 (data not shown), they spread significantly less in the presence of Slit2 than cells expressing Robo4 ED–TM or LacZ (Fig. 1c, d).

The inability of Robo4 ED–TM to inhibit spreading showed that the cytoplasmic tail is required for this activity. To test whether it is also sufficient for inhibition of spreading, we generated an αIIb integrin–Robo4 chimaeric protein (Fig. 1a), which enabled initiation of Robo4 signalling with fibrinogen, a ligand for αIIb:β3 integrin. Cells expressing αIIb:β3 integrin spread equivalently on fibronectin alone, and a mixture of fibronectin and fibrinogen, whereas αIIb integrin–Robo4:β3-expressing cells spread significantly less in the presence of fibrinogen (Fig. 1e).

To define the region of the Robo4 cytoplasmic tail that is required for inhibition of fibronectin-induced protrusive activity, cells expressing Robo4 deletion constructs (Fig. 1a) were subjected to haptotaxis assays. Migration of cells expressing Robo4 NH2, but not Robo4 COOH, was inhibited by Slit2 (Fig. 1f), indicating the necessity and sufficiency of the amino-terminal half of the Robo4 tail for suppressing cell motility elicited by the extracellular matrix.

Identification of the region of the Robo4 cytoplasmic tail that confers functional activity allowed us to search for cytoplasmic components that might regulate Robo4 signal transduction. Using the N-terminal half of the Robo4 tail as bait, a yeast two-hybrid screen of a human aortic cDNA library identified a member of the paxillin family of adaptor proteins, Hic-5, as a potential Robo4-interacting protein (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1).

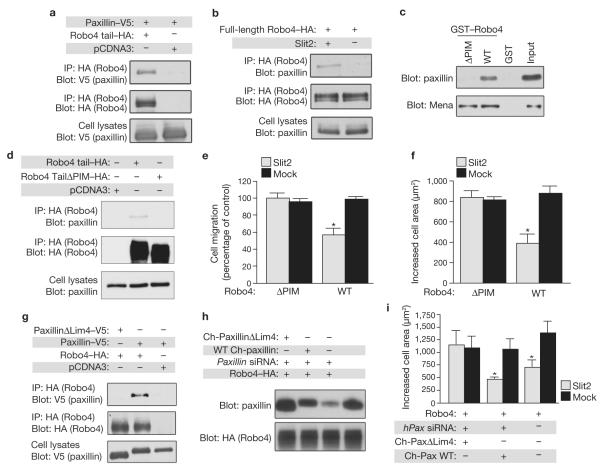

Hic-5 and its paralogue, paxillin, show cell-type-specific expression12,13.Western blotting of CHO-K1, HEK 293 and NIH3T3 cell lysates with antibodies against Hic-5 and paxillin detected paxillin in each cell line, whereas Hic-5 was only found in CHO-K1 and NIH3T3 cells (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1d). As functional studies used HEK 293 cells, this result suggested that paxillin interacts with Robo4 to regulate cell migration. As observed with Hic-5 (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1c), paxillin was identified in Robo4 immunoprecipitates of cells expressing paxillin and the Robo4 cytoplasmic tail, but not paxillin alone (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

Robo4–paxillin interaction is required for Slit2-dependent inhibition of protruive activity. (a) Lysates from HEK 293 cells expressing paxillin–V5 and Robo4 cytoplasmic tail–HA or empty vector (pcDNA3) were immunoprecipitated with HA antibodies and immunoblotted with V5 antibodies. (b) Lysates from Slit2-stimulated HEK 293 cells expressing full length Robo4–HA were immunoprecipitated with HA antibodies and immunoblotted with paxillin antibodies. (c) Purified GST–Robo4 wild type or GST–Robo4ΔPIM were incubated with recombinant purified paxillin or in vitro transcribed/translated Mena–V5, precipitated with glutathione agarose, and immunoblotted with paxillin or V5 antibodies. (d) Lysates from HEK293 cells expressing wild-type Robo4 cytoplasmic tail–HA, Robo4ΔPIM cytoplasmic tail–HA or empty vector (pcDNA3) were immunoprecipitated with HA antibodies and immunoblotted with paxillin antibodies. (e, f) HEK 293 cells expressing GFP and the indicated constructs were subjected to haptotaxis migration assays (e) or spreading assays (f) on fibronectin and mock or Slit2. (g) Lysates from HEK 293 cells expressing Robo4 cytoplasmic tail–HA and either wild-type paxillin-V5 or paxillinΔLim4–V5 were immunoprecipitated with HA antibodies and immunoblotted with V5 antibodies. (h) Endogenous paxillin was depleted in HEK 293 cells using siRNA and reconstituted with wild-type chicken (Ch-) paxillin or ChpaxillinΔLim4. Lysates were immunoblotted with paxillin antibodies. (i)Depleted/reconstituted HEK 293 cells were subjected to spreading assays on fibronectin and mock or Slit2. In migration assays, GFP-positive cells on the underside of the filter were counted and migration on fibronectin/mock membranes was set at 100% (n = 3, in triplicate). In spreading assays, the area of GFP-positive cells was determined using ImageJ software (n = 3,150 cells per experiment). Expression of Robo4 constructs was verified by immunoblotting (data not shown). *P < 0.05. Error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m. Full scans of blots are shown in Supplementary Information, Fig. S6. WT, wild type. Mock, sham preparation of Slit2.

As Slit2 activates Robo4 (refs 7, 8, 14, 15), we asked whether Slit2 stimulation regulates the interaction between Robo4 and paxillin. Full-length Robo4 was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates after incubation in the absence and presence of Slit2, and endogenous paxillin was only detected in Robo4 immunoprecipitates after Slit2 treatment (Fig. 2b).

We defined the region of Robo4 that is required for interaction with paxillin by generating GST–Robo4 fusion proteins spanning the cytoplasmic tail (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2a, b), and performing in vitro binding assays with purified recombinant paxillin (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2c, d). We identified a 70-amino-acid fragment of the N-terminal half of the Robo4 tail as the region that mediates interaction with paxillin (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2d). Deletion of this region prevented interaction with paxillin, as well as the known Robo family-binding protein Mena (murine enabled; data not shown)7,16. As Mena interacts with Robo through the Robo CC2 motif, which lies outside the deleted region, these binding data suggested that elimination of amino acids 604–674 affects conformation of the Robo4 tail.We then created smaller deletions within this 70-amino-acid stretch and performed additional in vitro binding assays (data not shown). Using this approach we identified a mutant GST–Robo4 fusion protein lacking 35 amino acids (604–639) that failed to bind paxillin, but retained interaction with Mena (Fig. 2c). This region of Robo4 is subsequently referred to as the paxillin interaction motif (PIM; Supplementary Information, Fig. S2e). We confirmed the importance of this region in promoting interaction with endogenous paxillin using co-immunoprecipitation from cells expressing wild-type Robo4 cytoplasmic tail or Robo4ΔPIM (Fig. 2d).

We next determined whether the PIM is important for receptor activity by performing functional assays with cells expressing Robo4ΔPIM. This mutant form of the receptor failed to inhibit fibronectin-induced cell migration and spreading in the presence of Slit2 (Fig. 2e, f), demonstrating that the region of the Robo4 tail necessary for paxillin binding is also required for inhibition of protrusive activity.

Although Robo4ΔPIM maintained its interaction with Mena (Fig. 2c), it remained possible that the mutation perturbed interactions between Robo4 and proteins other than paxillin. To investigate this, we generated paxillin mutants that disrupt its association with Robo4. Paxillin is a modular protein composed of N-terminal leucine/aspartic acid (LD) repeats and C-terminal Lim domains17 (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2f). Analysis of clones recovered from the yeast two-hybrid screen (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1a) suggested that the Lim domains, particularly Lim3 and Lim4, are important for interaction with Robo4. We performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments using cells expressing the Robo4 tail and either paxillin-LD or paxillin-Lim, and found Paxillin-Lim, but not paxillin-LD, was in Robo4 immunoprecipitates (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2g). To clarify which Lim domain is required for binding to Robo4, we made serial deletions from the C terminus of paxillin, co-transfected these with the Robo4 cytoplasmic tail into cells and performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Deletion of Lim4 completely abrogated binding between paxillin and Robo4 (Fig. 2g).

Delineation of the Robo4 binding site on paxillin allowed us to evaluate the role of paxillin in Robo4-dependent processes. If paxillin were required for receptor activity, the paxillinΔLim4 mutant, which is unable to interact with Robo4, should fail to inhibit fibronectin-induced spreading in the presence of Slit2. Endogenous paxillin was depleted in Robo4-expressing cells using short interfering RNA (siRNA) and then reconstituted with wild-type chicken paxillin (Ch-paxillin) or Ch-paxillinΔLim4, both of which are resistant to siRNA targeting the endogenous gene (Fig. 2h).Cells expressing Ch-paxillinΔLim4 spread normally in the presence of Slit2, whereas cells expressing Ch-paxillin showed a reduction in cell area characteristic of Slit2–Robo4 signalling (Fig. 2i).

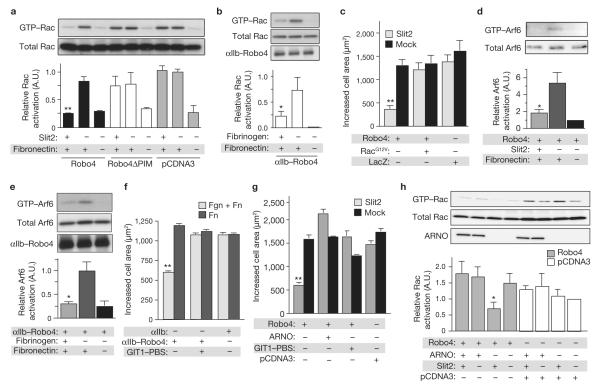

The ability of a cell to spread and migrate on an extracellular matrix protein, such as fibronectin, is regulated by the activation of Rho family GTPases, which include Rho, Cdc42 and Rac18. Of these proteins, Rac has an essential role in promoting the actin polymerization that leads to lamellipodial extension and cell spreading during migration18,19. To examine whether Slit2–Robo4 signalling inhibits adhesion-dependent Rac activation, cells expressing Robo4, Robo4ΔPIM or pcDNA3 alone were plated on fibronectin in the absence and presence of Slit2, and Rac–GTP levels were analysed. Additionally, cells expressing αIIb integrin–Robo4:β3 were plated on fibronectin in the absence and presence of fibrinogen, and Rac–GTP levels were analysed. Cells expressing Robo4 or αIIb integrin– Robo4:β3 showed significantly less adhesion-stimulated Rac activation when plated on Slit2 and fibrinogen, respectively (Fig. 3a, b). When this experiment was repeated with Robo4ΔPIM, we found that cells expressing this mutant receptor were refractory to Slit2 treatment (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

obo4 blocks Rac-dependent protrusive activity through inhibition of Arf6. (a) Lysates from HEK 293 cells expressing the indicated constructs,plated on fibronectin and mock or Slit2, were precipitated with GST–PBD and immunblotted with Rac antibodies (n = 3). (b) Lysates from CHO-K1 cells expressing αIIb-Robo4 were precipitated with GST–PBD and immunoblotted with Rac antibodies (n = 3). (c) HEK 293 cells expressing Robo4 and RacG12Vor LacZ were subjected to spreading assays on fibronectin and mock or Slit2.(d, e) Lysates from HEK 293 cells expressing full-length Robo4 (d) and CHO-K1 cells expressing αIIb integrin–Robo4 cytoplasmic tail (e), plated on the indicated matrix, were precipitated with GST–GGA3 and immunoblotted with Arf6 antibodies (n = 3). (f) CHO-K1 cells stably expressing αIIb or αIIb integrin–Robo4 cytoplasmic tail were co-transfected with GFP and either an empty vector or GIT1–PBS, and were subjected to spreading assays on the indicated matrix. (g) HEK 293 cells expressing GFP and the indicated constructs were subjected to spreading assays on fibronectin and Mock or Slit2. Expression of Robo4 and ARNO was verified by immunoblotting (data not shown). (h) Lysates from HEK 293 cells expressing the indicated constructs, plated on fibronectin and mock or Slit2, were precipitated with GST–PBD and immunoblotted with Rac antibodies (n = 3). For spreadingassays, the area of GFP-positive cells was determined using ImageJ software(n = 3, 150 cells per experiment). Expression of Robo4 constructs was verifiedby western blotting (data not shown). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005. Error bars xindicate the mean ± s.e.m. Full scans of blots are shown in Supplementary Information, Fig. S7. αIIb–Robo4 indicates αIIb integrin–Robo4.

To confirm that Robo4-dependent inhibition of cell spreading is principally due to suppression of Rac activation, we subjected cells co-expressing Robo4 and a dominant-active form of Rac, RacG12V, tospreading assays. Cells expressing RacG12V were refractory to Slit2 treatment (Fig. 3c), providing additional evidence that Slit2–Robo4 signalling blocks protrusive activity by inhibiting Rac.

We previously demonstrated that the interaction of α4integrin with a paxillin–GIT1 complex enables α4 integrin to control Rac-dependent changes in protrusive activity by modulating the activity of the small GTPase Arf6 (ref. 20). Our finding that Robo4 interacts with paxillin and inhibits protrusive activity prompted us to determine whether Robo4 signalling impinges on the Arf6 pathway. Cells expressing full-length Robo4 were plated on fibronectin in the absence and presence of Slit2, while those expressing αIIb integrin–Robo4:β3 were plated on fibronectin in the absence and presence of fibrinogen, and Arf6–GTP levels were analysed. Whereas fibronectin alone stimulated an increase in Arf6–GTP, both Slit2 and fibrinogen reduced Arf6–GTP levels in cells expressing Robo4 or αIIb integrin–Robo4:β3, respectively (Fig. 3d, e).

We analysed the requirement for a paxillin–GIT1 complex in Robo4dependent inhibition of protrusive activity. The GIT1 paxillin-binding sequence (PBS) is at the C terminus of the protein, and ectopic expression of this fragment blocks interaction between GIT1 and paxillin20.Cells were transfected with αIIb integrin–Robo4:β3 and an empty vector or GIT1–PBS, and subjected to spreading assays on fibronectin in the absence and presence of fibrinogen. Cells expressing αIIb integrin–Robo4:β3 showed a decrease in cell area when plated on fibronectin and fibrinogen, but this effect was lost in cells expressing GIT1–PBS (Fig. 3f). Similarly, in full-length Robo4-expressing cells plated on fibronectin and Slit2, GIT1–PBS prevented a decrease in cell area (Fig. 3g).

To determine whether Slit2–Robo4 signalling inhibits protrusive activity by inactivating Arf6, we co-expressed the Arf6 guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) ARNO with Robo4 and performed spreading assays. Overexpression of ARNO blocked the ability of Slit2 to reduce cell area, indicating that a principal effect of Slit2–Robo4 signalling is to prevent GTPloading of Arf6 (Fig. 3g). If ARNO restores the ability of Robo4-expressing cells to spread on fibronectin and Slit2, it should similarly re-establish Rac activation on this matrix. Indeed, overexpression of ARNO led to normal levels of Rac–GTP in cells plated on fibronectin and Slit2 (Fig. 3h).

To assess the effect of Slit2–Robo4 signalling on the subcellular distribution of paxillin, cells were plated on fibronectin in the absence and presence of Slit2, and stained for endogenous paxillin. In the absence of Slit2, cells expressing full-length Robo4 spread normally and formed abundant, paxillin-stained focal adhesions near the cell periphery (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3a, top panel). In the presence of Slit2, however, cells showed reduced spreading, contained less F-actin and formed fewer and smaller paxillin-stained focal adhesions(Supplementary Information, Fig. S3a, bottom panel). Control cells (cells not expressing Robo4) showed similar morphology when adhered on fibronectin alone or on fibronectin and Slit2 (data not shown), indicating that the effect of Slit2 is Robo4-dependent.

We repeated this assay using bovine aortic endothelial(BAE) cells, which endogenously express Robo4. On substrata coated with fibronectin and Slit2, BAE cells showed reduced spreading compared with cells adhered to fibronectin alone (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3b). In addition, BAE cells adhered to fibronectin and Slit2 formed small paxillin-stained structures, which were inconsistent with the mature focal adhesions observed in cells adhered to fibronectin alone (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3b; see arrows). The inhibitory effect of Slit2 on cell spreading seems to be transient, as cells adhered for extended intervals showed similar morphology and focal adhesion formation irrespective of Slit2 treatment (data not shown).

Our data suggest that in Robo4-expressing cells, Slit2 redistributes paxillin from focal adhesions to the cell surface, where it co-localizes with Robo4. To test this hypothesis, we analysed the subcellular distribution of paxillin and Robo4 in the absence and presence of Slit2. Because Slit2 blocks cell spreading and prevents clear visualization of the plasma membrane, we performed these experiments in endothelial cells pre-spread on fibronectin. In the absence of Slit2, paxillin was found almost exclusively in focal adhesions, whereas Robo4 was localized to the cell surface (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3c, top panel). In the presence of Slit2, however, a significant portion of paxillin appeared at the cell surface, co-localized with Robo4; this alteration in localization was coincident with a reduction of paxillin in focal adhesions (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3c, middle panel).

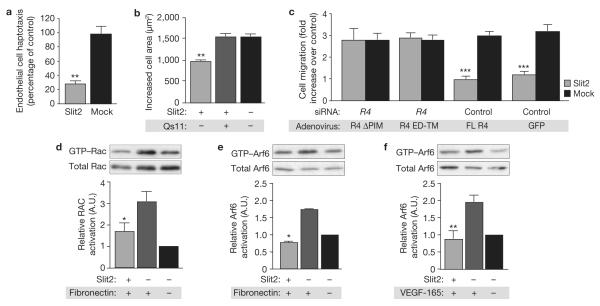

Thus far, our experiments had used model cell systems to decipher signal transduction downstream of Robo4. To determine whether this pathway is important for Robo4 function in primary cells, we first subjected human endothelial cells to haptotaxis assays and, analogous to the model cell system, Slit2 blocked fibronectin-driven cell motility (Fig. 4a). We also performed spreading assays on coverslips coated with the 9–11 fragment of fibronectin (a ligand for α5β1 integrin) and Slit2, and again found that Slit2 suppressed cellular protrusive activity stimulated by integrin ligation (Fig. 4b). To analyse a potential role for GIT1 in Slit2-dependent inhibition of cell protrusion, we pre-treated endothelial cells with a small-molecule inhibitor of Arf-GAPs, Qs11 (ref. 21), and subjected them to spreading assays on the 9–11 fibronectin fragment and Slit2. Arf–GAP-inhibition prevented the reduction in cell area elicited by Slit2 (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

Slit2–Robo4 signalling inhibits endothelial cell protrusive activity through paxillin and Arf-GAPs. (a) Endothelial cells were subjected to haptotaxis migration assays on fibronectin and mock or Slit2. Cells on the underside of the filter were counted and migration on fibronectin/mock membranes was set at 100% (n = 3, in triplicate). (b) Endothelial cells were subjected to spreading assays on fibronectin and mock or Slit2, in the absence and presence of Qs11 (n = 3, 150 cells per experiment). Cell area was determined using ImageJ software. (c) Robo4 was depleted in endothelial cells using siRNA. Cells were then infected with an adenovirus expressing the indicated constructs, and were subjected to migration assays (n = 5, in triplicate). (d, e) Lysates from endothelial cells plated on fibronectin and either mock or Slit2, were precipitated with GST–PBD and immunoblotted with Rac antibodies (d) or GST-GGA3 and immunoblotted with Arf6 antibodies (e; n = 3 in e and f). (f) Lysates from endothelial cells plated on VEGF-165 and mock or Slit2 were precipitated with GST–GGA3 and immunoblotted with Arf6 antibodies (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 and ***P < 0.0005. Error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m. Full scans of blots are shown in Supplementary Information, Fig. S8. R4, Robo4. FL, full-length.

Next, we determined the requirement for paxillin binding to Robo4 in Slit2-dependent inhibition of cell migration. We depleted endogenous Robo4 in human endothelial cells using siRNA, and reconstituted the receptor using adenoviral vectors expressing full-length murine Robo4, Robo4 ED–TM or Robo4ΔPIM, and subjected these cells to migration assays in the absence and presence of Slit2. The migration of control cells and Robo4-knockdown cells reconstituted with full-length Robo4 was inhibited by Slit2, but Slit2 had no effect on Robo4-knockdown cells reconstituted with either Robo4 ED–TM or Robo4ΔPIM (Fig. 4c).

These cell biological data suggest that Slit2–Robo4 signalling in endothelial cells blocks Rac and Arf6 activation in response to integrin ligation. To test this idea, we plated endothelial cells on fibronectin in the absence and presence of Slit2, and analysed Rac–GTP and Arf6–GTP levels. Consistent with results from the model cell systems, Slit2 blocked the fibronectin-induced increase in Rac–GTP (Fig. 4d) and Arf6–GTP levels (Fig. 4e). In addition to fibronectin, the angiogenic and permeability-inducing factor VEGF-165 exists in vivo as an extracellular matrix component, and has been suggested to stimulate Arf6 activation22. Consequently, we plated endothelial cells on VEGF-165 in the absence and presence of Slit2, and analysed Arf6–GTP levels. Whereas VEGF-165 induced Arf6 activation, addition of Slit2 prevented this stimulatory event (Fig. 4f).

We previously demonstrated that the effect of Slit2 on endothelial cell biology is Robo4-dependent6. To determine whether this relationship exists for the biochemical regulation of Arf6, we plated endothelial cells from Robo4+/+ and Robo4AP/AP mice6 on fibronectin, in the absence and presence of Slit2, and analysed Arf6–GTP levels. Slit2 decreased activated Arf6 in Robo4+/+, but notRobo4AP/AP, endothelial cells (Supplementary Information, Fig. S4).

In addition to Arf6 and Rac, Rho and Cdc42 have known roles in cellular protrusion18. To gain insight into the regulation of these small GTPases by Slit2, we plated endothelial cells on fibronectin in the absence and presence of Slit2, and analysed Rho–GTP and Cdc42–GTP levels. Whereas Rho activation was unaltered by Slit2, Cdc42 activation was significantly reduced (Supplementary Information, Fig. S5a, b). This latter effect was surprising given that Robo4 does not interact with the Robo1-binding protein srGAP1, a known Cdc42 GTPase-activating protein (Supplementary Information, Fig. S5c).

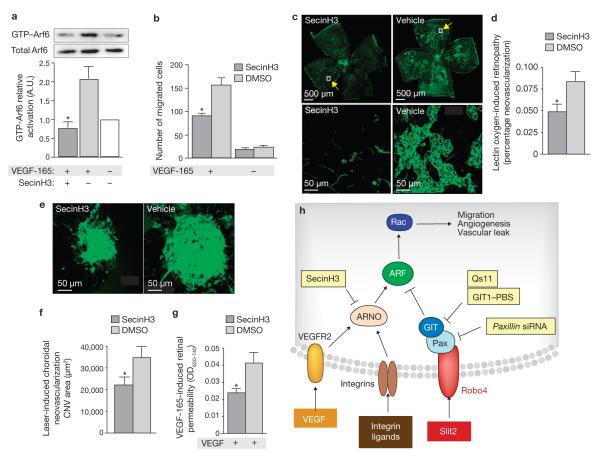

Recently, we showed that Robo4 mediates Slit2-dependent inhibition of neovascular tuft formation and endothelial hyperpermeability6, processes that are initiated and perpetuated by endothelial integrins and growth factor receptors. The ability of Slit2 to block Arf6 activation in response to fibronectin and VEGF-165 (which are ligands for these angiogenic and permeability-inducing receptors) led us to speculate that Arf6 is a critical nexus in signalling pathways regulating pathologic angiogenesis and vascular leak22. To test this hypothesis, we used a recently developed small-molecule inhibitor of cytohesin Arf–GEFs, SecinH3, which blocks insulin-induced Arf6 signalling23. SecinH3, but not DMSO, prevented both VEGF-induced Arf6 activation and VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration (Fig. 5a, b). Furthermore, injection of SecinH3 into the eyes of wild-type mice inhibited neovascular tuft formation in oxygen-induced retinopathy (Fig. 5c, d) and choroidal neovascularization (Fig. 5e, f), as well as retinal hyperpermeability caused by VEGF-165 (Fig. 5g).

Figure 5.

SecinH3 blocks Arf6 activation and inhibits pathologic angiogenesis and endothelial hyperpermeability in animal models of vascular eye disease.(a) Lysates from endothelial cells, pre-treated with SecinH3 or DMSO and then stimulated with VEGF-165, were precipitated with GST–GGA3 and immunoblotted with Arf6 antibodies. (b) Endothelial cells, pre-treated with SecinH3 or DMSO, were subjected to migration assays using VEGF-165.(c, e, g) SecinH3 or DMSO were injected into contralateral eyes of wildtype mice, which were then subjected to oxygen-induced retinopathy (c), laser-induced choroidal neovascularization (e) or VEGF-165-induced retinal hyperpermeability (g). (c) Retinal flatmounts prepared from neonatal mice subjected to oxygen-induced retinopathy were stained with fluorescent isolectin and analysed by fluorescence microscopy. Top panels are low magnification images, and bottom panels, high magnification images of the outlined areas, which emphasize the pathologic neovascular tufts.(d) Quantification of pathologic neovascularization shown in c(n = 14animals). (e) Choroidal flatmounts prepared from 2–3- month-old mice subjected to laser-induced choroidal neovascularization were stained with fluorescent isolectin and analysed by confocal microscopy. (f) Quantification of pathologic angiogenesis observed in e (n = 15 animals). (g) Quantification of retinal permeability following intravitreal injection of VEGF-165 (n = 6 animals). Vehicle is DMSO. *P < 0.05. Error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m.(h) VEGFR and integrin signalling promote sequential activation of Arf6 and Rac, leading to cellular protrusive activity. Concomitant initiation of Robo4-signalling by Slit2 stimulates recruitment of a paxillin–Arf–GAP complex to the cytoplasmic tail of the receptor, which causes local inactivation of Arf6and Rac, thereby blocking the protrusive activity necessary for angiogenesis and vascular leak. Full scans of blots are shown in SupplementaryInformation, Fig. S9. CNV, choroidal neovascularization.

Cumulatively, these data demonstrate the importance of paxillin and GIT1 in mediating Slit2–Robo4-dependent inhibition of endothelialcell protrusive activity, and suggest that blocking activation of Arf6 is a potential therapy for human diseases characterized by pathologic angiogenesis and vascular leak (Fig. 5h).

METHODS

Reagents

HEK 293 and COS-7 cells, and all IMAGE clones were from ATCC. SP6 and T7 Message Machine kits were from Ambion. Glutathione-Sepharose 4B, parental pGEX-4T1 and ECL PLUS were from Amersham-Pharmacia. Human fibronectin was from Biomedical Technologies and Invitrogen. Coomassie blue and PVDF (polyvinyldifluoride) were from BioRad. Yeast two-hybrid plasmids and reagents were from Clontech. Costar Transwells and Amicon Ultra-15 Concentrator Columns were from Fisher. FBS was from Hyclone. Anti-V5 antibody, DAPI, DMEM, Lipofectamine 2000, Penicillin-Streptomycin, Prolong Gold, Superscript III kit, Trizol and TrypLE Express were from Invitrogen. Goat Anti-Mouse-HRP and Goat Anti-Rabbit-HRP secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch. 3D Blind Deconvolution algorithm of AutoQuantX was from Media Cybernetics. HMVEC, HUVEC, EBM-2 and bullet kits were from Lonza. Alexa564-Phalloidin, Anti-GFP and Goat Anti-Rabbit Alex488 were from Molecular Probes. Rosetta2 Escherichia coli was from Novagen. Low melt agarose was from NuSieve. T7 in vitro transcription/translation kit was form Promega. Anti-HA affinity matrix, Fugene6 and protease inhibitor cocktail were from Roche. Arf6 antibody and normal Rat IgG-agarose conjugate was from Santa Cruz. Anti-Flag M2, phosphatase inhibitor cocktails, soybean trypsin inhibitor and fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA) were from Sigma. Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U microscope was from Semrock. Quick change site-directed mutagenesis kit was from Stratagene. Oligonucleotides for PCR were from the University of Utah Core Facility.

Molecular biology

The Robo4–HA, Slit2-Myc–His and chicken paxillin plasmids have been described previously2,7,20. Robo4–NH2 was amplified from Robo4–HA and cloned into EcoRV/NotI of pcDNA3-HA. Robo4–COOH was amplified from Robo4–HA by overlap-extension PCR and cloned into EcoRV/NotI of pcDNA––HA. The N-terminal half of the human Robo4 cytoplasmic tail (amio-acids 465–723) was amplified by PCR and cloned into (EcoRI/BamHI) of pGBKT7. Murine Robo4 fragments were amplified by PCR and cloned into BamHI/EcoRI of pGEX-4T1. Murine Hic-5, Mena and paxillin (including deletions) were amplified from IMAGE clones by PCR and cloned into EcoRV/NotI of pcDNA3-V5. GST–Robo4ΔPIM and full-length Robo4ΔPIM were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of relevant wild-type constructs using Quick Change. The integrity of all constructs was verified by sequencing at the University of Utah Core Facility.

Cell culture

HEK 293 and COS-7 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC) were cultured in EGM-2 MV and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were cultured in EGM-2 supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were used between passages 2 and 5.

Transfection

HEK293 and COS-7 cells were transfected with Fugene6 or Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Preparation of concentrated recombinant Slit2 protein

Slit2 and mock were prepared as described previously6. Mock is sham preparation of Slit2, and was used as a control in all experiments analysing the effect of Slit2.

Haptotaxis migration assay

Cells were removed from tissue culture dishes with TrypLE Express, washed once with 0.1% trypsin inhibitor, 0.2% fatty acidfree BSA in DMEM or EBM-2, and twice with 0.2% BSA in the relevant media. The washed cells were counted, resuspended, and 1.5 × 105 (HEK) or 0.2 × 105(HMVEC) cells were loaded into the upper chamber of 12-μm (HEK) or 8-μm (HMVEC) Costar transwells pre-coated on the lower surface with fibronectin (5 μg ml−1). The effect of Slit2 on haptotaxis was analysed by co-coating with Slit2 (5 μg ml−1) or an equivalent amount of mock. After 6 h (HEK) or 3 h (HMVEC), cells on the upper surface of the transwell were removed with a cotton swab. The cells on the lower surface were fixed with 4% formaldehyde, washed three times with PBS and mounted in Vectashield with DAPI. The number of GFP-positive (HEK) and DAPI-positive (HMVEC) cells on the lower surface was determined by counting six 10× fields on an inverted fluorescence microscope. The number of migrated cells on fibronectin/mock-coated membranes was set at 100%. Experiments were performed at least three times in triplicate.

Yeast two hybrid assay

pGBKT7::hRobo4 465-723 was transformed into the yeast strain PJ694A, creating PJ694A-Robo4. A human aortic cDNA library was cloned into the prey plasmid pACT2 and then transformed into PJ694A-Robo4. Co-transformed yeast strains were plated onto SD-Leu-Trp (-LT) to analyse transformation efficiency and SD-Leu-Trp-His-Ade (-LTHA) to identify putative interacting proteins. Yeast strains competent to grow on SD–LTHA were then tested for expression of β-galactosidase by a filter lift assay. Prey plasmids were isolated from yeast strains capable of growing on SD–LTHA and expressing β-galactosidase, and sequenced at the University of Utah Core Facility.

Immunoprecipitation

Cell lysates were prepared in 50 mM Tris-Cl at pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.5% Triton X-100, phosphatase and protease inhibitors, centrifuged at 16,000g for 20 min, cleared with normal IgG coupled to agarose beads for 60 min, and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with relevant antibodies coupled to agarose beads. The precipitates were washed extensively in lysis buffer and resuspended in 2× sample buffer (125 mM Tris-Cl at pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 20% Glycerol, 0.04% bromophenol blue and 1.4 M 2-mercaptoethanol).

GST pulldown assay

Rosetta2 E. coli cells harbouring pGEX-4T1::mRobo4 were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6 and induced with IPTG(0.3 mM). After 3–4 h at 30 °C, cells were centrifuged at 2,800g for 5 min, cells were lysed by sonication in 20 mM Tris-Cl at pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, lysozyme (1 μg ml−1), DTT (1 mM) and protease inhibitors. The GST fusion proteins were captured on glutathione-Sepharose 4B, washed once with lysis buffer without lysozyme and then twice with binding/wash buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl at pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% BSA and protease inhibitors). The GST fusion proteins were incubated with purified recombinant paxillin (60 nM) overnight at 4 °C, washed extensively in binding/wash buffer, and resuspended in 2× sample buffer.

Immunoblotting

Protein samples were incubated for 2 min at 100 °C, separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane. PVDF membranes were incubated with 5% non-fat dry milk in PBS + 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST; PBST-M) for 60 min at 25 °C. Blocked membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (against Arf6, Cdc42, Flag M2, Hic-5, paxillin, Rac and Rho) in PBST-M for 60 min at 25 °C, or overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were washed for 10 min, three times, in PBST and then incubated with a secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase) for 60 min at 25 °C. Membranes were washed for 10 min, three times, in PBST and visualized with ECL PLUS. Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: antibodies against GTPases, 1:1,000; Flag, 1:1,000; Hic-5, 1:500 and paxillin, 1:10,000.

In vitro transcription/translation

Mena-V5 was synthesized with the T7 Quick Coupled in vitro Transcription/Translation system according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Spreading assay

Cell spreading was analysed as described previously20. The cell area from at least 150 cells, from three independent experiments, was measured using ImageJ (NIH).

Depletion and reconstitution of paxillin

HEK 293 cells were transfected with 100 nM of siRNA duplexes (5′-CCCUGACGAAAGAGAAGCCUAUU-3′ and 5′-UAGGCUUCUCUUUCGUCAGGGUU-3′) using Lipofectamine 2000, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At 48 h after transfection, cells were processed for biochemical analysis or cell spreading assays. Paxillin reconstitution was accomplished by transfection with an expression vector encoding chicken paxillin, which has the nucleotide sequence 5′-CCCCTACAAAAGAAAAACCAA-3′ within the siRNA target site. Knockdown and reconstitution were analysed by immunoblotting with paxillin antibodies, and quantified by densitometry.

GTPase activation assays

GTPase activation was analysed as described previously20. Experiments were performed at least three times.

Adenoviral preparation

Murine full-length Robo4, Robo4ΔPIM, and Robo4 ED–TM were subcloned into pShuttle-IRES-hrGFP-2 (Stratagene). Independently, these vectors were used with pAdEasy to cotransform BJ5183 cells (Stratagene). Recombinant plasmids were linearized by PacI digestion and transfected into 293 cells for packaging. The adenovirus was then amplified and titered for plaque forming units (PFU).

Depletion and reconstitution of Robo4

huRobo4 siRNA duplex (Hs_ ROBO4_1_HP #1919431, Qiagen) or, alternatively, equimolar AllStars Negative Control siRNA (#1027280, Qiagen) was diluted to 480 nM in OptiMEM (Invitrogen). To form transfection complexes, siRNAs were premixed for 5–15 minutes at room temperature with HiPerfect Transfection Reagent (70 μl; Qiagen) and added to human microvascular endothelial cells. After an overnight incubation, cells were re-transfected with siRNA according to the same protocol. Adenoviral constructs were also added at a concentration of 1 × 106 PFU ml−1 and allowed to incubate overnight.

Immunofluorescence imaging

Glass coverslips were coated sequentially with human plasma fibronectin (5 μg ml−1) and Slit2 or Mock (5 μg ml−1), and blocked with 1% BSA. HEK Robo4 and bovine aortic endothelial (BAE) cells were then adhered for 30 min in serum-free DMEM supplemented with 1% BSA, and fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS. Cells were permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min, blocked and stained for Paxillin using either a rabbit polyclonal antibody or a mouse monoclonal antibody and counterstained with a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. When indicated, cells were co-stained for F-actin with rhodamine-phalloidin. Coverslips were subsequently mounted in Prolong Gold antifade reagent on slides. Epi-fluorescent images of cells were acquired with a 60× oil immersion objective on a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U microscope. Images as shown are maximal projections of deconvolved images that were acquired at 0.1-μm z-section intervals. Images were deconvolved using the 3D Blind Deconvolution algorithm of AutoQuantX. Additional post-acquisition processing of images was performed using ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop.

Retinal permeability

Retinal permeability was assessed as described previously15.Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. for six wild-type mice.

Oxygen-induced retinopathy

Oxygen-induced retinopathy was induced as described previously15. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. for 14 wild-type mice.

Laser-induced choroidal neovascularisation

Laser-induced choroidal neovascularization was induced as described previously15. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. for at least 15 wild-type mice.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test or ANOVA was used to determine statistical significance, where appropriate. All P values were derived from at least three independent experiments.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank J. Wythe for critical reading of the manuscript, and D. Lim for expert graphical assistance. J. Bonafacino provided the GST–GGA3 expression plasmid. This work was funded by grants from the H.A. and Edna Benning Foundation, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, the American Heart Association, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the Department of Defense (D.Y.L.); the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (D.Y.L. and M.H.G.); the National Eye Institute (K.Z.); the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft SFB 704 (M.F.); the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (M.H.G.); the National Institute of Allergy and Disease AI065357 (D.Y.L.) and by the US National Institutes of Health, Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (N.R.L.) and training grant T32-GM007464 (A.C.C.).

Footnotes

Current address: Department of Microbial Chemical Biology and Drug Discovery, Iwate Medical University School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2-1-1 Nishitokuta, Yahaba, Shiwa-gun, Iwate 028-3694, Japan.

Supplementary Information is available on the Nature Cell Biology website.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/ reprintsandpermissions/.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS The authors declare competing financial interests. The University of Utah has filed patents covering the technology described in this manuscript with the intent of commercializing this technology.

METHODS Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/naturecellbiology/.

References

- 1.Seeger M, Tear G, Ferres-Marco D, Goodman CS. Mutations affecting growth cone guidance in Drosophila: genes necessary for guidance toward or away from the midline. Neuron. 1993;10:409–426. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90330-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brose K, et al. Slit proteins bind Robo receptors and have an evolutionarily conserved role in repulsive axon guidance. Cell. 1999;96:795–806. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kidd T, Bland KS, Goodman CS. Slit is the midline repellent for the robo receptor in Drosophila. Cell. 1999;96:785–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidd T, et al. Roundabout controls axon crossing of the CNS midline and defines a novel subfamily of evolutionarily conserved guidance receptors. Cell. 1998;92:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80915-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li HS, et al. Vertebrate slit, a secreted ligand for the transmembrane protein roundabout, is a repellent for olfactory bulb axons. Cell. 1999;96:807–818. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones CA, et al. Robo4 stabilizes the vascular network by inhibiting pathologic angiogenesis and endothelial hyperpermeability. Nature Med. 2008;14:448–453. doi: 10.1038/nm1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park KW, et al. Robo4 is a vascular-specific receptor that inhibits endothelial migration. Dev. Biol. 2003;261:251–267. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seth P, et al. Magic roundabout, a tumor endothelial marker: expression and signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2005;332:533–541. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ridley AJ, et al. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302:1704–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollard TD, Borisy GG. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 2003;112:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etienne-Manneville S, Hall A. Rho GTPases in cell biology. Nature. 2002;420:629–635. doi: 10.1038/nature01148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turner CE. Paxillin and focal adhesion signalling. Nature cell Biol. 2000;2:E231–236. doi: 10.1038/35046659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuminamochi T, et al. Expression of the LIM proteins paxillin and Hic-5 in human tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2003;51:513–521. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hohenester E, Hussain S, Howitt JA. Interaction of the guidance molecule Slit with cellular receptors. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006;34:418–421. doi: 10.1042/BST0340418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones CA, et al. Robo4 stabilizes the vascular network by inhibiting pathologic angiogenesis and endothelial hyperpermeability. Nature Med. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nm1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bashaw GJ, Kidd T, Murray D, Pawson T, Goodman CS. Repulsive axon guidance: Abelson and Enabled play opposing roles downstream of the roundabout receptor. Cell. 2000;101:703–715. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80883-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner CE. Paxillin interactions. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 23):4139–4140. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.23.4139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nobes CD, Hall A. Rho, rac, and cdc42 GTPases regulate the assembly of multimolecular focal complexes associated with actin stress fibers, lamellipodia, and filopodia. Cell. 1995;81:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nobes CD, Hall A. Rho GTPases control polarity, protrusion, and adhesion during cell movement. J. Cell Biol. 1999;144:1235–1244. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishiya N, Kiosses WB, Han J, Ginsberg MH. An alpha4 integrin-paxillin-ArfGAP complex restricts Rac activation to the leading edge of migrating cells. Nature Cell Biol. 2005;7:343–352. doi: 10.1038/ncb1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Q, et al. Small-molecule synergist of the Wnt/ -catenin signaling pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:7444–7448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702136104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda S, et al. Novel role of ARF6 in vascular endothelial growth factor-induced signaling and angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 2005;96:467–475. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000158286.51045.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hafner M, et al. Inhibition of cytohesins by SecinH3 leads to hepatic insulin resistance. Nature. 2006;444:941–944. doi: 10.1038/nature05415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.