Abstract

Study Objectives:

Insomnia is a common problem that affects 9% to 15% of the population chronically. The primary objective of this study was to demonstrate that 8 weekly sessions of sleep restriction therapy of insomnia combined with hypnotic reduction instructions following a single session of sleep hygiene education would result in greater improvements in sleep and hypnotic use than sleep hygiene education alone.

Methods:

Forty-six men and women were recruited from a sleep medicine practice and randomly assigned to sleep hygiene education plus 8 weeks of sleep restriction and hypnotic withdrawal (SR+HW; n = 24), or a sleep hygiene education alone (SHE; n = 22) condition. Pre-randomization, all patients received a single session of instruction in good sleep habits (sleep hygiene education).

Results:

The SR+HW condition had greater improvements in hypnotic medication usage, sleep onset latency, morning wake time, sleep efficiency, and wake time after sleep onset (trend), than the SHE condition. Continued improvement was seen in TST in the SR+HW group at 6-month follow-up, and gains on all other variables were maintained at 6- and 12-month follow-up.

Conclusions:

These results provide evidence that more intensive treatment of insomnia (i.e., 8 sessions of SR+HW plus hypnotic withdrawal instructions) results in better outcomes than SHE alone.

Citation:

Taylor DJ; Schmidt-Nowara W; Jessop CA; Ahearn J. Sleep restriction therapy and hypnotic withdrawal versus sleep hygiene education in hypnotic using patients with insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med 2010;6(2):169-175.

Keywords: Randomized, clinical, insomnia, hypnotic, nurse, restriction

Chronic insomnia affects 9% to 15% of the population1 and results in direct and total costs of approximately $14 billion per year and $30-35 billion per year, respectively.2 Cognitive behavioral therapy of insomnia appears to have short-term efficacy equal to hypnotic medications and long-term efficacy better than hypnotic medications treating patients with primary insomnia.3–6

The current trend in cognitive behavioral therapy of insomnia is to use a multicomponent approach, which combines several well-established treatments to maximize results, but these multicomponent treatments are time intensive (e.g., 6-10 sessions) and have generally been validated with psychologists as therapists.7,8 This modality may not translate well into a busy medical practice, where general practitioners and nursing staff are pressed for time and might be more likely to deliver a single informational visit with instructions on good sleep habits (e.g., avoid caffeine, alcohol and nicotine at bedtime, regular wake time).9 While this may seem like a reasonable approach, studies show sleep hygiene instructions such as these have little effect.7,8

Although it would be nice to have a psychologist in office who could deliver 6-10 sessions of cognitive and behavioral therapies of insomnia, barriers currently exist (e.g., limited availability of psychologists with expertise in insomnia treatments, different billing procedures). One solution to this difficulty is to use nurses, who can be effective administering multicomponent therapy.10,11 However, no studies have shown the effectiveness of the simpler sleep restriction intervention by nurses. Sleep restriction might be easier for busy clinicians to learn than multimodal treatments, making it easier to disseminate, and thus provide improved treatment for a larger number of patients.

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Many patients with chronic insomnia and regular hypnotic use continue to be dissatisfied with their sleep quality. This study examined whether a behavioral intervention, sleep restriction therapy, combined with sleep hygiene, can improve sleep and reduce hypnotic use compared to sleep hygiene education alone.

Study Impact: This randomized controlled trial confirms that sleep restriction therapy is effective in improving sleep in chronic insomniacs and enables reduced hypnotic use and withdrawal. Significant contributions to the study of insomnia therapy include the focus on patients with chronic hypnotic use, the demonstration of better sleep with less medication, the use of a nurse therapist to implement treatment, and the maintenance of the treatment effect during one year follow up.

To date, three trials have found that sleep restriction was an effective single modality treatment of insomnia, making this an empirically supported psychological treatment for insomnia.12–14 Since its introduction, sleep restriction has generally been combined with stimulus control to maximize the effectiveness of this second intervention, which may be one reason that sleep restriction has only been used in a few efficacy studies as a single treatment. To date, there are no data to show that more intensive multicomponent therapies are more efficacious than the single therapies. One advantage sleep restriction has over some of the other treatment modalities is that it is relatively easy to explain to patients and somewhat simpler to implement. Indeed, recent research has shown that one session of sleep restriction instruction administered by a psychologist within a primary care clinic produced significant gains.15

Many (24% to 53%) patients in primary care and sleep medicine clinics report using hypnotics for insomnia.16,17 Several trials of multimodal and single mode (i.e., stimulus control and relaxation) treatments have shown efficacy in people taking hypnotics on a regular basis.18–24 Sleep restriction has yet to be explored as a single treatment within this context.

The primary hypothesis of the current study was that a nurse-delivered treatment of 8 sessions of sleep restriction therapy and hypnotic withdrawal instructions (SR+HW) following a single session of sleep hygiene education would result in greater improvements than the single sleep hygiene education (SHE) session alone.

METHODS

Participants

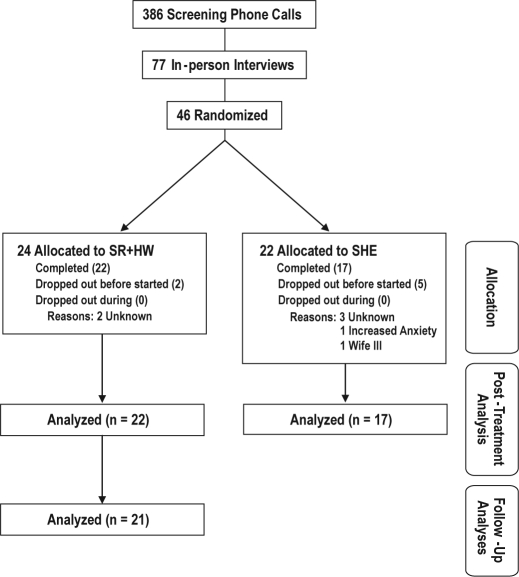

Patients (N = 386) were recruited from a sleep medicine practice (WSN), area primary care physician practices, and by appeals to the public with newspaper and radio advertising. A multistep screening process produced 46 eligible patients, who were subsequently randomized into the 2 treatment groups (SHE: n = 22; SR+HW: n = 24). Of these 46 randomized participants, the majority (35) were Caucasian, with Hispanics being the next largest group (7). The remainder of the participants were Asian, Black, or American Indian (1, 1, and 2, respectively). As can be seen in Figure 1, a total of 22 patients completed SR+HW therapy, and 17 completed SHE. All results presented are comparisons of completers. Participants assigned to a SHE condition were given the opportunity to receive SR+HW after the SHE period.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participant screening and enrollment.

Measures

Sleep Diaries

Daily sleep diaries provided the primary outcome measures used in this study, and extra effort was made (i.e., phone calls and extra visits) to establish appropriate use of the logs in the first 2 weeks. Participants were to fill out the sleep diary each morning, giving an estimate of their sleep the night before (e.g., bedtime, sleep onset). The first 2 weeks of sleep diaries were used to confirm patients' insomnia diagnoses. The second week was used as baseline in those who were subsequently randomized. After randomization, each subject kept a sleep log for the 8-week treatment period, and for 2 weeks at 6- and 12-month follow-up. Parameters calculated from the sleep logs were time in bed (TIB), total sleep time (TST), number of awakenings (AWAK), sleep onset latency (SOL), terminal wakefulness (TWAK; amount of awake time between the final awakening and the time of getting out of bed), wake time after sleep onset (WASO), and sleep efficiency (SE: TST/TIB × 100).

Apnea Monitor

A TriMed apnea monitor was used to evaluate sleep apnea. This is a screening device for sleep disturbed breathing based on CO2 detection by nasal cannula during sleep.25 Patients with frequencies > 10/h were excluded. An exclusion cutoff of AHI > 10 was selected because the TriMed apnea monitor was oversensitive (i.e., too many false positive diagnoses) at a cutoff of AHI > 5.25

Procedures

Volunteers went through a multistep screening process that consisted of telephone interviews, in-person interviews by the study nurse (CAJ), and a physical examination (WSN); a portable apnea monitor was used to screen for significant sleep disturbed breathing. The interviews used questionnaires and 2 weeks of baseline sleep diaries to confirm the presence of insomnia and a history of hypnotic use; the medical examination was a sleep focused history and physical examination.

Inclusion criteria were a report of chronic ( ≥ 6 months) insomnia, defined as persistent problems initiating or maintaining sleep, and a report of regular ( ≥ 1 month during the preceding 6 months) use of a hypnotic or other sleep promoting agent. Confirmation of the insomnia complaint was based on a 2-week log demonstrating SE < 85%. Patients were excluded from the current study if they (a) were unwilling to commit to reduced hypnotic use; (b) were unable to attend weekly visits for a period of 10 weeks; (c) were unable to maintain a sleep log; (d) had sleep apnea (AHI > 10); or (e) reported another significant concurrent medical illness (e.g., thyroid dysfunction, shingles, pain, congestive heart failure) that would interfere with adherence to the protocol; or (f) active psychiatric illness or related medication.

When the insomnia diagnosis was confirmed and medical and psychiatric disorders excluded, the patient was accepted into the study. Before randomization, all subjects were given sleep hygiene education (SHE) instructions (see below). Participants were then randomly assigned, using block randomization (blocks of 4) concealed from the recruiter, to either the SHE (n = 22) condition or the SR+HW (n = 24) condition. Those assigned to the SHE condition received no further intervention for 8 weeks. Those in the SR+HW condition received 8 weekly sessions of sleep restriction therapy of insomnia; when sleep efficiency rose to 90%, hypnotics were tapered and withdrawn (see below).

At the completion of the 8-week experimental phase, patients were reassessed. Patients originally assigned to the SHE condition were referred to the SRT + HW protocol after their post-SHE assessment. Six and 12 months later, patients who completed the SR+HW condition were reexamined by means of 2-week sleep log and a questionnaire to assess the state of their insomnia problem.

Conditions

Sleep Hygiene Education (SHE)

Pre-randomization, the SHE condition received the following sleep hygiene education instructions during a single office visit:

HABITS for BETTER SLEEP

Regular arousal time

Regular exercise (early)

Attenuate noise

Regulate the temperature

Regular light snack

Eliminate caffeine late in the day

Eliminate alcohol

Decrease tobacco use

Patients received a copy of these instructions for reference at home. These instructions were given in the belief that they were already known to many patients and in order to standardize groups at baseline.

Sleep Restriction Therapy and Hypnotic Withdrawal (SR+HW)

In this condition, all patients received SHE at baseline, which was followed by SR and when applicable, hypnotic withdrawal.

Sleep Restriction Therapy (SR)

Sleep restriction instructions typically ask the patient to immediately restrict their time in bed (TIB) to approximate their average total sleep time (TST) or TST plus 30 min (not < 5 h). Patients are then allowed to gradually expand their time in bed by 15-30 min each week, as long as sleep efficiency [(TST/TIB) × 100] remains above 87% to 90%.13 The purpose of sleep restriction is to restrict time in bed to maximize sleep efficiency through a greater emphasis on the regulation of the sleep-wake cycle.13 In the current study, the nurse asked patients to reduce time in bed to 10% above the average estimated TST reported by the patients in their sleep diaries of the previous week (never < 5 h). The nurse reviewed the diaries at each weekly session and recommended sleep restriction and hypnotic withdrawal treatments based on the data.

Hypnotic Withdrawal (HW)

When sleep efficiency rose to 90%, hypnotics were withdrawn. Patients were advised to reduce the dose 50% for one week; if tolerated, they were advised to discontinue. Once hypnotics were withdrawn, and if sleep efficiency remained ≥ 90%, time in bed was extended in 15-min increments until either 7 h of sleep were reported, or 8 weeks of treatment had elapsed.

Clinician

The nurse therapist (CAJ) was an experienced RN with full-time activity in sleep medicine, who was trained and closely supervised by the second author (WSN), a Diplomate of the American Board of Sleep Medicine and experienced sleep medicine physician. In addition, the project received consultation with Arthur Spielman, PhD, developer of the SR treatment,13 who visited the site in Albuquerque and reviewed the protocol.

RESULTS

Baseline Comparisons

As can be seen in Tables 1 and 2, the SR+HW and SHE conditions were similar in all baseline measures, although there was a trend for gender difference, with more females in the SHE condition. There were no significant differences between conditions on any sleep variables.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants at baseline (N = 46)

| Variable | SR+HW | SHE | Total | t or χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.47 | 0.148 | |||

| M | 56.75 | 50.36 | 53.70 | ||

| SD | 15.29 | 14.10 | 14.89 | ||

| Gender | |||||

| % Female | 41.7% | 68.2% | 54.3% | 3.25 | 0.071 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| % Caucasian | 83.3% | 68.2% | 76.1% | 4.78 | 0.331 |

SR+HW, sleep restriction therapy and hypnotic withdrawal condition; SHE, sleep hygiene education condition

Table 2.

Means (SD) of sleep parameters comparing sleep restriction therapy and hypnotic withdrawal condition (SR+HW; n = 22) and sleep hygiene education condition (SHE; n = 17) conditions at pre-treatment and post-treatment

| Variable | Pre-TX |

Post-TX |

6-mo FU |

12-mo FU |

Pre-post × Condition |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | Δ | df | F | p | Cohen's d | |

| SE (%) | 1 | 9.98 | 0.003 | 1.16 | |||||||||

| SR+HW | 70.66 | (11.77) | 87.77 | (7.00) | 88.07 | (7.81) | 86.62 | (9.58) | 17.11 | ||||

| SHE | 70.50 | (10.12) | 75.98 | (11.50) | 5.48 | ||||||||

| TST (min) | 1 | 2.50 | 0.122 | ||||||||||

| SR+HW | 346.72 | (62.98) | 339.46 | (57.60) | 395.41 | (43.64) | 390.71 | (51.33) | −7.26 | ||||

| SHE | 320.67 | (57.65) | 343.80 | (69.50) | 23.13 | ||||||||

| SOL (min) | 1 | 5.17 | 0.029 | 0.56 | |||||||||

| SR+HW | 57.60 | (33.28) | 23.18 | (22.98) | 22.28 | (20.55) | 23.24 | (19.08) | −34.42 | ||||

| SHE | 56.36 | (33.85) | 40.18 | (31.76) | −16.18 | ||||||||

| WASO (min) | 1 | 4.02 | 0.052 | 0.57 | |||||||||

| SR+HW | 56.17 | (32.87) | 14.96 | (8.66) | 22.37 | (15.82) | 26.92 | (30.27) | −41.21 | ||||

| SHE | 49.97 | (32.89) | 30.08 | (23.95) | −19.89 | ||||||||

| TWAK (min) | 1 | 13.29 | 0.001 | 1.06 | |||||||||

| SR+HW | 38.83 | (29.95) | 10.96 | (11.00) | 16.71 | (16.71) | 22.97 | (15.99) | −27.87 | ||||

| SHE | 40.74 | (34.53) | 43.50 | (43.00) | 2.76 | ||||||||

| Drugs (doses/wk) | 1 | 19.48 | < 0.001 | 1.05 | |||||||||

| SR+HW | 1.25 | (0.90) | 0.28 | (0.45) | 0.17 | (0.34) | 0.18 | (0.35) | −0.97 | ||||

| SHE | 1.13 | (0.86) | 1.11 | (0.93) | −0.02 | ||||||||

All effect size calculations were performed with conventions from the ES software package using Data Source 0801: Two-Factor (conditions × Time) repeated-measures ANOVA.

TX, treatment; FU, follow-up; SR+HW, sleep restriction therapy and hypnotic withdrawal condition; SHE, sleep hygiene education condition; SOL, sleep onset latency; WASO, wake time after sleep onset; TWAK, final wakefulness (amount of awake time between the final awakening and the time of getting out of bed); SE, sleep efficiency; TST, total sleep time.

Sleep

Given that the variables TIB, SOL, WASO, TWAK are used to derive TST (i.e., TST = TIB – (SOL+WASO+TWAK)) and SE ((TST/TIB) × 100), to avoid multicollinearity we first performed between subjects (SR+HW vs. SHE) repeated-measures (pre-treatment vs. post-treatment) analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with SE and TST as dependent variables. These analyses were followed by a similar multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), with SOL, WASO, and TWAK as the dependent variables.

As can be seen in Table 2, the SR+HW condition had significantly greater improvements on SE than the SHE condition from pre- to post-treatment, but not in TST, which is not uncommon considering the sleep period reduction and potential short-term sleep deprivation associated with SR+HW. The MANOVA for SOL, WASO, and TWAK was also significant, Wilks λ = −0.698, F3, 35 = 5.043, p = 0.005. Follow-up univariate analyses showed that the SR+HW condition had significantly greater improvements on SOL and TWAK, with a trend for WASO (p = 0.052).

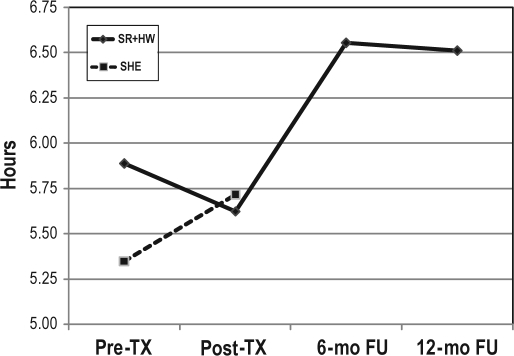

Similar repeated-measures (post-treatment vs. 6-month follow-up; 6-month follow-up vs. 12-month follow-up) ANOVAs and MANOVAs were run with the same sleep variables as above, to assess maintenance of gains within the treatment condition only (because SHE were given SR+HW after the post-treatment assessment). As shown in Figure 2, at 6-month follow-up, there was significant (i.e., ∼60 min) improvement in TST in the SR+HW condition, F1, 20 = 17.374, p < 0.001. There were no differences from 6-month to 12-month follow-up, F1, 18 = 0.099, p = 0.757, indicating maintenance of gains over the 6- to 12-month follow-up.

Figure 2.

Total sleep time (TST) scores in patients receiving sleep restriction therapy and hypnotic withdrawal condition (SR+HW; n = 22) and sleep hygiene education condition (SHE; n = 17).

TX, treatment; mo, month; FU, follow-up

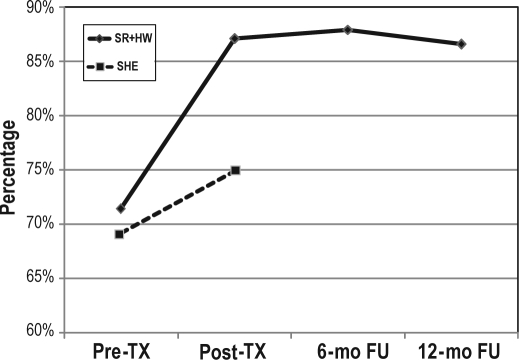

As shown in Figure 3, SE showed no significant differences from post-treatment to 6-month follow-up, F1, 20 = 0.036, p = 0.851, or from 6-month to 12-month follow-up, F1, 18 = 0.638, p = 0.435, again indicating maintenance of gains over 12-months follow-up.

Figure 3.

Sleep efficiency in patients receiving sleep restriction therapy and hypnotic withdrawal condition (SR+HW; n = 22) and sleep hygiene education condition (SHE; n = 17).

TX, treatment; mo, month; FU, follow-up

Finally, no differences were seen on SOL, WASO, or TWAK (all p values > 0.05) from post-treatment to 6-month follow-up or from 6-month to 12-month follow-up, again indicating maintenance of gains over 12-months follow-up.

Hypnotic Use

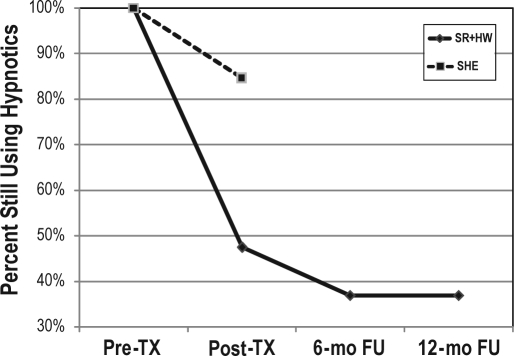

Participants were excluded from these analyses if they were not actively taking hypnotic medication at baseline. At baseline, 82.1% of these participants (i.e., SR+HW = 19, SHE = 13) were using hypnotic medication at least once per week.

A 2 (SR+HW vs. SHE) × 2 (pre-treatment vs. post-treatment) repeated-measures ANOVA with number of nights of hypnotic use as the dependent variable showed that the SR+HW condition had significantly lower use of hypnotics post-treatment than the SHE condition, F1, 37 = 19.48, p < 0.001. Similar repeated-measures (post-treatment vs. 6 months follow-up; 6-month follow-up vs. 12-month follow-up) ANOVAs were run with hypnotic use as the dependent variable. Although Table 2 shows continued improvement from post-treatment to 6-month follow-up, these analyses, as well as the 6-month versus 12-month comparison, showed no significant differences, which indicates no statistically significant improvements, but these hypnotic use reductions were maintained over 12 months follow-up.

When hypnotic use data were dichotomized, 52.6% of the subjects in the SR+HW condition had stopped using hypnotic medication by post-treatment, compared to 15.4% of the SHE condition, χ2 (1) = 4.57, p = 0.033. As can be seen in Figure 4, by 6-month follow-up, 63.2% of the SR+HW condition had quit using hypnotics, but this was not a statistically significant reduction (p = 0.414). There was no change from 6-month to 12-month follow-up. These results confirm that treatment gains in hypnotic use were maintained at follow-up.

Figure 4.

Hypnotic use status in patients receiving sleep restriction therapy and hypnotic withdrawal condition (SR+HW; n = 19) and sleep hygiene education condition (SHE; n = 13).

TX, treatment; mo, month; FU, follow-up

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show superior efficacy of SR+HW protocol over SHE, when administered by a nurse to insomnia patients using hypnotic medications. The SR+HW treatment resulted in significant improvements in self-reported sleep and reduced hypnotic medication usage, which were maintained at 6- and 12-month follow-up. This finding is important in that many clinicians may feel that providing a single informational session describing healthy sleep habits (sleep hygiene) represents a behavioral treatment of insomnia, but these findings show this intervention alone is not sufficient.

SR is a validated behavioral treatment of insomnia.7,8 At the time the current study was conceived (1989), only the Spielman case study had been performed, and a randomized clinical trial was needed to validate this new treatment.13 During the course of this study (1989-1992), and not long after, Friedman et al. performed two randomized clinical trials in older adults that showed single modality SR was more effective than a placebo condition14 and sleep hygiene education alone.12 The current study replicated the findings of these previous studies, and extends them by showing that sleep restriction is efficacious at improving sleep and reducing hypnotics in people with insomnia who are using hypnotics. This study also supports previous research that shows nurses can effectively administer multi-session behavioral treatments of insomnia, with resultant improvements in hypnotic use.10,11

The results of this study have important implications for the management of chronic insomnia and hypnotic dependence in primary care. Nurses are often the first person a patient has contact with when they go to their physician and are less expensive than physicians and psychologists. It is important for these clinicians to know that a single session of sleep hygiene education is not a sufficient treatment. Further, sleep restriction has greater promise of potential dissemination into primary care and sleep medicine clinics than multimodal treatments, because it is relatively easy to explain to patients, takes little time to learn as a clinician, and is simpler to implement. Therefore, it is important for more nurses to be trained in SR, so that patients with insomnia may get more timely and efficacious treatment of their insomnia.

A unique feature of this study is the focus on hypnotic dependent patients with insomnia and the ability to reduce hypnotic use while simultaneously receiving SR. Hypnotic withdrawal is a difficult problem, because the perception of worse sleep with less medication discourages the patient from further efforts. Whether chronic hypnotic use results in tolerance and dependence is a controversial issue in the pharmacology of sleep, especially with more contemporary agents. Regardless of the mechanism, the loss of sleep quality with drug withdrawal produces a kind of dependence that can frustrate attempts at alternative therapy. This study confirms the problem, in that 37% of patients were unable or unwilling to reduce hypnotic use, even though they had accepted the goal of drug withdrawal on study entry. On the other hand, the majority of patients had varying success in drug reduction, with more than half completely withdrawing. These findings were in line with other studies which have found behavioral treatments of insomnia delivered by nurses24 or other trained professionals,20–23 can result in significant improvements of hypnotic usage, whether specific tapering methods are used or not. Future studies might examine the efficacy of a variety of hypnotic withdrawal protocols, when combined with cognitive and behavioral interventions of insomnia.

Another important finding was the persistence of treatment gains in the SR+HW condition over a 12-month follow up. This suggests that a relatively intense but brief intervention for eight weeks can have lasting benefits. Of particular interest is that patients were able to extend their total sleep time by another hour at 6-month follow-up, while maintaining improved sleep efficiency and thus resolving one of the shortcomings of the sleep restriction method (i.e., a net reduction in total sleep). Of equal importance is that drug use did not return to pre-treatment levels, suggesting that patients found the behavioral method to be a satisfactory substitute for chronic hypnotic use.

Several potential confounders in the study design need to be considered. One component of sleep restriction and stimulus control (e.g., regular arousal time) was included in the baseline sleep hygiene education and may have been a factor in the improvement of both conditions. While the total treatment effect may have been influenced by this behavioral element, we believe that, similar to in Friedman et al.,12 the difference between the conditions was attributable to SR, as this was the essential difference between the two conditions. The additional element of hypnotic withdrawal may have influenced the treatment outcome as well, although more likely by reducing the effect attributable to SR.

This study would have been strengthened by the use of objective assessments of sleep (polysomnography) and hypnotic use (i.e., MEMS Caps or pill counts) at post-treatment and follow-up. Without objective measures, it is difficult to determine if social desirability was at play in patients' self-reports of treatment gains. We do not believe this was a major weakness though, as the use of sleep diaries and self-report of medication is what is most likely to transpire in clinical practice, making our results more ecologically valid. In addition, these results are in agreement with studies that consistently show sleep improvements with SR,7,8 as well as hypnotic usage reductions with behavioral treatments of insomnia delivered by nurses24 or other trained professionals.20–23

In addition, using only one nurse as the clinician could have resulted in a therapist effect, where patients improved because the patients liked the therapist or because that nurse was particularly effective, and not because of the effectiveness of the intervention. Again, this was likely not a major limitation, as our results were in line with previous studies that found nurses can effectively administer other behavioral treatments of insomnia.10,11

Future effectiveness studies might compare a variety of modalities (single and multimodal) treatments, for a variety of lengths (1 session vs. multiple), within multiple contexts (primary care physician, sleep medicine clinic, psychologists offices), provided by a variety of professional levels (paraprofessionals, masters level therapists, nurses, psychologists, and physicians [sleep specialists or otherwise]). Until such time, the current research clearly shows multiple sessions of SR combined with hypnotic withdrawal instructions are clearly more effective at treating insomnia and reducing hypnotic use than a single session of sleep hygiene education, when administered by a nurse.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was performed at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque, New Mexico

REFERENCES

- 1.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: What we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:97–111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh JK, Engelhardt CL. The direct economic costs of insomnia in the United States for 1995. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl 2):S386–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sivertsen B, Omvik S, Pallesen S, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2851–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.24.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith MT, Perlis ML, Park A, et al. Comparative meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy for persistent insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:5–11. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morin CM, Colecchi C, Stone J, Sood R, Brink D. Behavioral and pharmacological therapies for late-life insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;281:991–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.11.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobs GD, Pace-Schott EF, Stickgold R, Otto MW. Cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy for insomnia: a randomized controlled trial and direct comparison. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1888–96. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.17.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgenthaler T, Kramer M, Alessi C, et al. Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: An update. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep. 2006;29:1415–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morin CM, Bootzin RR, Buysse DJ, Edinger JD, Espie CA, Lichstein KL. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: Update of the recent evidence (1998-2004) Sleep. 2006;29:1398–414. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.11.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bootzin RR. Honolulu, HI: American Psychological Association 80th Annual Convention Proceedings; 1972; 1972. A stimulus control treatment for insomnia; pp. 395–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espie CA, Inglis SJ, Tessier S, Harvey L. The clinical effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic insomnia: implementation and evaluation of a sleep clinic in general medical practice. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39:45–60. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espie CA, MacMahon KM, Kelly HL, et al. Randomized clinical effectiveness trial of nurse-administered small-group cognitive behavior therapy for persistent insomnia in general practice. Sleep. 2007;30:574–84. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.5.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman L, Benson K, Noda A, et al. An actigraphic comparison of sleep restriction and sleep hygiene treatments for insomnia in older adults. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2000;13:17–27. doi: 10.1177/089198870001300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spielman AJ, Saskin P, Thorpy MJ. Treatment of chronic insomnia by restriction of time in bed. Sleep. 1987;10:45–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman L, Bliwise DL, Yesavage JA, Salom SR. A preliminary study comparing sleep restriction and relaxation treatments for insomnia in older adults. J Gerontol. 1991;46:P1–P8. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.1.p1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edinger JD, Sampson WS. A primary care “friendly” cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy. Sleep. 2003;26:177–82. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hohagen F, Rink K, Kappler C, et al. A longitudinal study. Prevalence and treatment of insomnia in general practice. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;242:329–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02190245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenthal LD, Dolan DC, Taylor DJ, Grieser E. Long-term follow-up of patients with insomnia. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2008;21:264–5. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2008.11928409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lichstein KL, Peterson BA, Riedel BW, Means MK, Epperson MT, Aguillard RN. Relaxation to assist sleep medication withdrawal. Behav Modif. 1999;23:379–402. doi: 10.1177/0145445599233003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riedel B, Lichstein K, Peterson BA, Epperson MT, Means MK, Aguillard RN. A comparison of the efficacy of stimulus control for medicated and nonmedicated insomniacs. Behav Modif. 1998;22:3–28. doi: 10.1177/01454455980221001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curran HV, Collins R, Fletcher S, Kee SCY, Woods B, Iliffe S. Older adults and withdrawal from benzodiazepine hypnotics in general practice: Effects on cognitive function, sleep, mood and quality of life. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1223–37. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morin CM, Bastien C, Guay B, Radouco-Thomas M, Leblanc J, Vallieres A. Randomized clinical trial of supervised tapering and cognitive behavior therapy to facilitate benzodiazepine discontinuation in older adults with chronic insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:332–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan K, Dixon S, Mathers N, Thompson J, Tomeny M. Psychological treatment for insomnia in the management of long-term hypnotic drug use: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:923–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soeffing JP, Lichstein KL, Nau SD, et al. Psychological treatment of insomnia in hypnotic-dependant older adults. Sleep Med. 2008;9:165–71. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Espie CA, Inglis SJ, Tessier S, Harvey L. The clinical effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic insomnia: Implementation and evaluation of a sleep clinic in general medical practice. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39:45–60. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt-Nowara WW. Cardiovascular consequences of sleep apnea. In: Issa FG, Suratt PM, Remmers JE, editors. Sleep and respiration. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1990. pp. 377–85. [Google Scholar]