Abstract

Study Objectives:

To review studies examining the cooccurrence of insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), explore evidence for the effect of OSA therapy on insomnia symptoms and the effect of insomnia treatments on breathing and sleep in patients with OSA, and discuss challenges in the evaluation and treatment of comorbid insomnia and OSA.

Methods/Results:

Seven pertinent studies were identified that assessed the prevalence of comorbid insomnia and OSA or sleep disordered breathing. Four studies were identified that examined the effects of OSA treatment in patients with insomnia, and 8 studies were found that examined hypnotic use in patients with OSA or sleep disordered breathing. A high prevalence (39%-58%) of insomnia symptoms have been reported in patients with OSA, and between 29% and 67% of patients with insomnia have an apnea-hypopnea index of greater than 5. Combination therapy, including both cognitive behavior therapy and OSA treatment, resulted in greater improvements in insomnia than did either cognitive behavior therapy or OSA treatment alone. The use of GABAergic nonbenzodiazepine agents has been associated with improvements in sleep and has little to no effect on the apnea-hypopnea index in patients with OSA.

Conclusions:

Insomnia and OSA frequently cooccur. The optimal strategy for adequately treating comorbid insomnia and OSA remains unclear. Future research examining the impact of insomnia on continuous positive airway pressure therapy is needed. Given the substantial overlap in symptoms between insomnia and OSA, evaluation and treatment of these 2 conditions can be challenging and will require multidisciplinary collaboration among sleep specialists.

Citation:

Luyster FS; Buysse DJ; Strollo PJ. Comorbid insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea: challenges for clinical practice and research. J Clin Sleep Med 2010;6(2):196-204.

Keywords: Insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), sleep disordered breathing (SDB)

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and insomnia are often thought of as opposing clinical conditions, specifically in regard to alertness and sleepiness. Hyperarousal processes such as increased whole body and brain metabolism, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation, and elevated heart rate and sympathetic nervous system activation may play a key role in the pathophysiology of insomnia, thus causing an elevated level of alertness during both the night and daytime.1,2 On the other hand, frequent arousals and fragmented sleep associated with OSA often lead to excessive daytime sleepiness, although daytime sleepiness is not universally present in all patients with OSA.3–5 Increasing evidence from studies suggests that insomnia and OSA frequently coexist.6–12

In this review, we first provide background information on OSA and insomnia separately, including definitions, symptoms, and health risks. Second, we review studies examining the cooccurrence of insomnia in patients with OSA and of OSA in patients with insomnia. Third, we explore the evidence for the effect of OSA therapy on insomnia symptoms and the effect of insomnia treatments on breathing and sleep in patients with OSA and discuss the possible impact of insomnia on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy. Finally, we discuss challenges in the evaluation and treatment of comorbid insomnia and OSA and identify future research needs.

METHODS

We conducted an extensive MEDLINE search for English-language studies examining the prevalence of comorbid insomnia and OSA or sleep disordered breathing (SDB), treatment studies of OSA in participants with insomnia, and treatment studies using hypnotics in participants with OSA or SDB. In addition, we searched the reference lists of all identified relevant publications. The keywords used to search for articles on the prevalence of comorbid insomnia and OSA or SDB were insomnia, sleep apnea, and sleep disordered breathing. The search terms used to identify treatment studies of OSA or SDB in patients with insomnia were insomnia, sleep apnea, sleep disordered breathing, positive airway pressure, oral appliance, and surgery. For articles on hypnotic use in patients with OSA or SDB, the search terms used were sleep apnea, sleep disordered breathing, hypnotic, trazodone, amitriptyline, and flurazepam, quazepam, estazolam, temazepam, triazolam (Food and Drug Administration-approved benzodiazepine agents), as well as eszopiclone, zolpidem, and zaleplon (Food and Drug Administration-approved nonbenzodiazepine agents).

Studies were included in the review if they reported data from an original study (i.e., no review articles) and reported (a) the prevalence of insomnia assessed via polysomnography, interview, or questionnaires in participants diagnosed with OSA or SDB; (b) the prevalence of diagnosed OSA or SDB in participants who were identified as having insomnia via polysomnography, interview, or questionnaires; (c) the effect of OSA or SDB treatments in participants identified as having insomnia and diagnosed OSA or SDB; and (d) hypnotic use in participants with diagnosed OSA or SDB. The first author (FSL) searched the database and reviewed identified articles to determine if each article met inclusion criteria. The search yielded 337 potential article titles for review that addressed comorbid insomnia and OSA or SDB, of which 120 were excluded for being review articles and 210 were excluded for not meeting inclusion criterion a or b. Thus, 7 articles were included in this review, which assessed the prevalence of comorbid insomnia and OSA or SDB (Table 1 and Table 2). The search yielded 42 articles regarding OSA or SDB treatments in participants with insomnia, of which 4 met inclusion criterion c and were included in the review. Sixty-six articles were identified that examined the use of hypnotics in participants with OSA or SDB. No studies were found that examined the use of trazodone, amitriptyline, quazepam, estazolam, or zaleplon in patients with OSA. Of the 66 treatment articles, 9 studies met inclusion criterion d and were included in the review. Thus, a total of 20 articles were included in the review.

Table 1.

Prevalence of insomnia symptoms in patients with OSA.

| Source, year | Population | Agea | Sexb | Prevalence of insomnia symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smith et al., 200612 | 102 patients diagnosed with OSA at sleep clinic | 53.91 ± 13.67, 18-87 | 69.5 | 39% of patients with OSA met criteria for insomniac |

| Chung et al., 20056 | 157 patients diagnosed with OSA by PSG | 44.5 ± 9.6 | 93 | 42% reported at least 1 insomnia symptomd |

| Krell et al., 200510 | 228 patients diagnosed with SDB by PSG | 47, 20-85 | 60.4 | 54.9% reported 1 of 3 insomnia complaintsd |

| Krakow et al., 20019 | 231 patients diagnosed with SDB at sleep disorders center | 51, 19-79 | 68.8 | 50% reported 2 of 3 insomnia complaintse |

OSA refers to obstructive sleep apnea; SDB, sleep disordered breathing; PSG, polysomnography.

Data are presented as mean ± SD, range;

Data are presented as the percentage of men;

Criteria for insomnia included an Insomnia Severity Index ≥ 15, sleep-onset latency (SOL) or wake time after sleep onset > 30 min from polysomnography (PSG), and at least 1 daytime consequence;

Insomnia symptoms or complaints included sleep-maintenance insomnia, sleep-onset insomnia, or early morning awakenings;

Insomnia complaints included SOL > 30 minutes, wake up a lot, or difficulty returning to sleep once awakened.

Table 2.

Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with insomnia.

| Source, year | Population | Agea | Sexb | Prevalence of insomnia symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gooneratneet et al., 20067 | 200 community-dwelling older adults—100 with insomnia symptoms and 100 without insomnia symptoms | 71.9 ± 5.0 | 65.8 | 29.3% of older adults with insomnia had an AHI ≥ 15. |

| Guilleminaultet et al., 20058 | 394 postmenopausal women with chronic insomnia complaints | 55-70 | 100 | 67% had an AHI > 5 during portable monitoring or PSG. |

| Lichstein et al., 200511 | 80 older adults ineligible for insomnia research due to suspected OSA, PLM, or RLS. | 69.4 ± 7.2, 59-92 | 60 | 29% had an AHI > 15 and 43% had an AHI > 5 during PSG. |

AHI refers to apnea-hypopnea index; PSG, polysomnography; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PLM, periodic limb movements; RLS, restless legs syndrome.

Data are presented as mean ± SD, range;

Data are presented as the percentage of women.

OSA and Insomnia as Separate Conditions

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

OSA is defined by repetitive apneas and hypopneas caused by upper airway collapse during sleep, despite persistent ventilatory efforts. OSA severity is most often characterized by the number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep, with an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of between 5 and 14 considered as mild, 15 to 29 as moderate, and 30 or greater as severe.13 The termination of apneas and hypopneas is associated with a transient arousal from sleep. Sleep disruption due to frequent arousals may lead to excessive daytime sleepiness or fatigue. Loud snoring or witnessed breathing interruptions are often reported by the bedpartner and the patient. Patient reports of awakening with a sensation of gasping or choking are characteristic of OSA.

Insomnia

Insomnia can be defined as a symptom comprising sleep-specific complaints—such as difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, early awakenings, or unrefreshing or nonrestorative sleep—or as a disorder denoting sleep and waking symptoms. Depending on the conceptualization of insomnia, prevalence rates of insomnia can vary widely, from 6% to 48%.14 Typically, insomnia is defined by subtype based on frequency, duration, and etiology. The following qualitative insomnia diagnostic criteria have been suggested: sleep-onset latency or wake after sleep onset greater than 30 minutes, occurring at least 3 times per week, and with duration of at least 6 months.15 Using only sleep-specific insomnia symptoms for sample characterization may be a suboptimal approach to defining clinically significant insomnia.16 The inclusion of daytime symptoms along with sleep complaints has been recommended as a more acceptable definition of insomnia in research practice, given that daytime symptoms often prompt treatment seeking.16

Health Risks

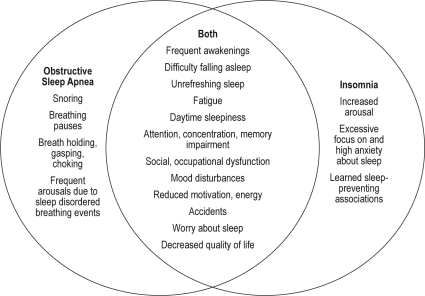

In addition to several symptoms, insomnia and OSA also share a number of negative consequences, including decreased health-related quality of life, psychological symptoms, and increased work-related impairments such as absenteeism and lost work productivity (Figure 1).17–21 Decreased vigilance or falling asleep at the wheel may impair driving performance, thus increasing the risk of motor vehicle crashes in patients with either OSA and insomnia.22–26 Short sleep duration associated with insomnia may increase cardiovascular risk and, in particular, the risk of developing hypertension.27,28 Additionally, OSA is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease (e.g., hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, and stroke) and is common in those with existing cardiovascular disease.29–31 Insomnia is a typical symptom of psychiatric disorders and may be an independent risk factor for the development of such disorders.32,33 Insomnia and OSA pose considerable safety and health problems for patients. The impact on health is likely to be increased when the conditions coexist.

Figure 1.

The interrelationship between symptoms and clinical factors associated with obstructive sleep apnea and insomnia.

Symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea and insomnia were derived from the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-2nd edition criteria for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and general insomnia disorder, except for hyperarousal, anxiety about sleep, and learned associations, which were adopted from criteria for psychophysiological insomnia.

Prevalence of Comorbid Insomnia and OSA

Comorbid Insomnia in OSA

The association between insomnia and OSA was described by Guilleminault and colleagues in 1973.34 Subsequently, limited attention has been given to the presence of comorbid insomnia in OSA. A high prevalence (39% to 55%) of insomnia symptoms has been reported in patients with OSA in the small number of available studies (Table 1).6,9–10,12 Krakow and colleagues9 retrospectively assessed the prevalence of insomnia in a sample of 231 patients with SDB or upper airway resistance syndrome. Patients who reported 2 or 3 of the following insomnia complaints were categorized as having both SDB and insomnia (SDB+): require 30 minutes to fall asleep; wake up frequently; and, if awakened, have difficulty returning to sleep. Those reporting no insomnia complaints or 1 insomnia compliant were designated SDB-only. More than 50% of the sample (n = 116) reported clinically meaningful insomnia complaints (SDB+ group), including sleep-onset latency of longer than 30 minutes (51% vs 3% of SDB-only patients) or difficulty returning to sleep once awake (59% vs 10%). The SDB+ group had snoring patterns and arterial oxygen saturations similar to those of the SDB-only group; however, the SDB+ group had significantly lower AHIs (mean, 46/h in SDB+ vs 58/h in SDB–only groups). The SDB+ patients reported significantly worse sleep characteristics consistent with insomnia, including a longer sleep latency, reduced total sleep time, and impaired sleep efficiency.

In a prospective study of 105 consecutive patients referred for investigation of suspected OSA, 102 patients were diagnosed with OSA, and 39% (n = 41) of these patients met study criteria for insomnia, including an Insomnia Severity Index score of at least 15, duration of the sleep complaint for longer than 6 months, a sleep-onset latency or wake time after sleep onset longer than 30 minutes on polysomnography, and at least 1 daytime consequence of sleep disturbances.12 OSA severity was correlated with insomnia-symptom severity score (r = 0.79, p < 0.001). In contrast, insomnia complaints were not related to OSA severity in a retrospective cross-sectional study of 255 patients undergoing evaluation for possible OSA.10 More than half of the sample (54.9%) reported 1 of 3 insomnia complaints, including difficulty initiating sleep (33.4%), difficulty maintaining sleep (38.8%), and early morning awakenings (31.4%). Additionally, 50% (n = 127) of patients had a combination of hypersomnia and insomnia complaints. Insomnia complaints were more prevalent in patients without SDB than in those with SDB (81.5% vs 51.8%, respectively).

Chung6 retrospectively examined the prevalence of different subtypes of insomnia in patients with OSA diagnosed by overnight polysomnography. Of the 157 patients, 91 (58%) had no insomnia symptoms, 44 (28%) had 1 insomnia symptom, 15 (9.6%) had 2, and 7 (4.4%) had 3 or 4 symptoms. The most frequent insomnia complaint was difficulty maintaining sleep, with 26% reporting waking up repeatedly during the night often or almost always. The prevalence of other insomnia complaints were as follows: 6% reported difficulty getting to sleep, 12% reported waking up during the night and having a hard time getting back to sleep, and 19% reported early morning awakenings.

Inconsistencies in the definitions and assessments of insomnia across these studies hinder our understanding of the prevalence of comorbid insomnia in OSA and limit the ability to compare findings across studies. For example, 2 studies considered patients to have insomnia symptoms if they reported having difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, or early morning awakenings often or almost always.6,10 Krakow and colleagues9 inquired about difficulties initiating and maintaining sleep but not early morning awakenings and assessed the presence of symptoms but not their frequency. In contrast with the other studies, Smith and colleagues used more stringent criteria that included objective and subjective assessment of symptoms and inquiry about duration of sleep complaints and daytime consequences of sleep disturbances.12 Although the prevalence of insomnia in OSA appears to be high, a clearer understanding of the magnitude of this comorbidity will require more standardized methods for characterizing clinically significant insomnia in OSA.

Comorbid OSA in Insomnia

OSA in patients presenting with insomnia complaints has been examined in several studies (Table 2).7–8,11 Lichstein and colleagues11 found that 29% of older adults with insomnia recruited for a research study (n = 80) had polysomnography-diagnosed OSA (AHI > 15), even after those with a high index of suspicion for OSA were excluded by screening clinical interview. In a case-control study (N = 200), approximately 30% of community-dwelling elderly adults with insomnia had diagnosed SDB (AHI ≥ 15), although this percentage was lower than in those without insomnia (38%).7 Among 394 postmenopausal women with chronic insomnia complaints without major psychiatric or medical disorders, 67% (n = 264) had an AHI of at least 5, based on either home monitoring or polysomnography.8

Clinical Factors Associated With Comorbid Insomnia and OSA

Few of the identified studies considered the relationship between population characteristics and comorbid OSA and insomnia. In those that did, 4 studies found no difference in age6–7,9–10 and 2 studies found no differences in sex6,9 between those with OSA and insomnia and those with only OSA or insomnia. In 1 study, more women than men had OSA and insomnia (51.4% vs 48.6% with OSA or insomnia only).10 In contrast, as compared with those with insomnia only, more men than women had comorbid OSA and insomnia.11 As compared with Hispanics, non-Hispanic whites comprised a significantly greater proportion of patients with SDB and insomnia.9

One study reported a significant difference in the rates of psychiatric disorders between patients with OSA and insomnia and those with only OSA (47.8% vs 28.7%, respectively).10 Insomnia complaints in those with OSA were associated with chronic pain and symptoms of restless legs. Krakow and colleges9 found that patients with SDB and insomnia reported more cognitive-emotional complaints (i.e., attention or concentration, memory, depressed feelings, anxious feelings, irritability, hostility, frustration, and claustrophobia), mental symptoms (i.e., racing thoughts and rumination, anxiety and fear), physical symptoms (i.e., trouble breathing, restless legs, indigestion, and pain), and psychiatric disorders than did patients with only SDB. Similarly, in a sample of patients referred for investigation of OSA, those with diagnosed OSA and whose symptoms also met the criteria for insomnia reported significantly more symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress than did patients diagnosed with only OSA.12 Patients with OSA and insomnia also endorsed more dysfunctional beliefs about sleep, in particular, concerns about the long-term consequences of poor sleep on behavior and higher levels of need for control over sleep.

In a community sample of older adults, those with insomnia and OSA reported more snoring and witnessed apneas and were more likely to have a body mass index of 30 or greater and a neck size 15 inches or larger, as compared with older adults with only insomnia.7 Comparatively, no differences in body mass index or snoring were found between a research sample of older adults with insomnia and OSA or with insomnia but no OSA.11 The insomnia plus OSA group had lower scores on the Geriatric Depression Scale (mean = 2.7, SD = 2.3) than did the insomnia-only group (mean = 4.9, SD = 4.5), although the mean scores were both within the normal range. No differences in excessive daytime sleepiness, sleep efficiency, or frequent awakenings were found between older adults with insomnia and OSA and those with insomnia only in both the community and research samples.7,11 Among postmenopausal women with insomnia, women with an AHI of 5 or greater and those with an AHI of less than 5 had similar scores on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale and similar objective total sleep time and sleep latencies.8

Treatment of Comorbid Insomnia and OSA

Limited information is available regarding the concurrent treatment of these comorbid sleep disorders. Sequential OSA therapy and cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) in patients with comorbid insomnia and OSA has been examined in 2 studies.35, 36 Studies examining the use of hypnotic agents in patients with OSA have primarily focused on measures of breathing during sleep and acceptance and adherence to CPAP and have not examined the effect of these drugs on sleep in patients with OSA and insomnia.

Treatment of OSA in Patients With Chronic Insomnia

Adults with sleep-maintenance insomnia and OSA symptoms randomly assigned to receive nasal-dilator-strip therapy reported greater improvements in insomnia severity and sleep quality than did those who received only education.37 Krakow and colleagues36 examined the effect of SDB treatment (CPAP, oral appliances, or bilateral turbinectomy) on sleep measures in patients with chronic insomnia and SDB who completed a CBT program. Both treatment phases (baseline to 3 months after completing CBT program and CBT follow-up to after maintaining 3 months' use of SDB therapy) resulted in improvements in insomnia severity and sleep-related daytime impairments. However, CBT alone had only a small effect on daytime impairments. After CBT, only 8 out of 17 patients attained a nonclinical level of insomnia, compared with 15 patients who received both CBT therapy and treatment for SDB. Combination therapy that included both CBT and OSA treatment resulted in greater improvements in insomnia complaints than did CBT alone.

In a prospective crossover study, 30 patients with complaints of insomnia and mild OSA, matched for age and sex, received either CBT or surgical treatment of OSA as primary treatment, followed by the alternative treatment if agreeable.35 Treatment of OSA alone was successful in eliminating complaints of insomnia in 5 out of 15 participants, whereas none of the participants receiving CBT alone felt that the insomnia complaints had resolved. More specifically, surgical intervention for OSA demonstrated greater initial improvements in subjective and objective sleep quality and respiratory measures than did CBT. However, CBT following surgical intervention provided additional benefits of further increasing total sleep time and decreasing sleep-onset latency by addressing the behavior component of conditioning and other residual sleep problems. Results of this study suggest that treating both insomnia and OSA together is the best approach for addressing comorbid insomnia and OSA. Treatment of the breathing problem alone was not successful in eliminating insomnia complaints in all patients, which argues for the presence of an insomnia-OSA phenotype.

Treatment of Insomnia in Patients With OSA

The use of benzodiazepines in patients with sleep apnea has been limited because the use of these drugs is associated with reduced upper airway muscle tone and decreased ventilatory response to hypoxia, thus potentially increasing the AHI and prolonging events.38 In a study comparing 30 mg of flurazepam with placebo, the flurazepam group had an increased number of apnea episodes (9.95 vs 5.35) and a longer duration of apneas (3.44 minutes vs 1.72 minutes).39 Increases in arousal threshold resulting in modest prolongation of event duration and increased desaturation have been documented with administration of triazolam in patients with severe OSA.40 However, the use of benzodiazepines in other studies has resulted in no significant changes in respiration. In 1 study, a dose of 15 to 30 mg of temazepam did not increase the respiratory disturbance index in elderly patients with mild sleep apnea and insomnia (8.8 ± 5.3), as compared with the nondrug group that received placebo or behavior therapy (9.2 ± 2.8).41 In summary, the effects of benzodiazepines on OSA are modest at best.

Studies have investigated the use of GABAergic nonbenzodiazepine agents (zaleplon, zolpidem, eszopiclone) in patients with OSA.42–46 Nonbenzodiazepine agents have hypnotic and sedative effects similar to those of benzodiazepines, but some (especially those selective for GABA receptors containing α1 subunits) may have fewer muscle-relaxant effects, thus offering a more favorable treatment approach to insomnia in OSA. A pilot study evaluating the use of eszopiclone, a selective GABAergic nonbenzodiazepine agent, in patients with mild to moderate OSA found no significant differences in mean AHI scores, total arousals, respiratory arousals, duration of apnea and hypopnea episodes, or oxygen saturation between patients treated with placebo and those treated with eszopiclone.45 Patients treated with eszopiclone experienced improved sleep duration and sleep efficacy and reduced wake time during sleep and wake time after sleep onset. Administration of 3 mg of eszopiclone prior to diagnostic polysomnography or CPAP titration significantly reduced sleep latency, improved sleep efficiency, reduced wake time after sleep onset, prolonged sleep time, and did not worsen the severity of SDB or impair airway stability.44 In a study of 16 patients with severe OSA who were treated with an effective level of CPAP, administration of 10 mg of zolpidem did not increase the AHI or oxygen desaturation index.42 Sleep architecture did not differ between zolpidem and placebo nights except for a reduction in sleep latency and the mean arousal index on zolpidem nights. This study suggests that zolpidem does not impede CPAP efficacy in patients with severe OSA. A dose of 20 mg of zolpidem, which is above the recommended hypnotic dose, did increase the apnea index and oxygen desaturation, suggesting that the usual therapeutic doses of zolpidem should not be exceeded when treating patients with OSA.46

The efficacy of selective nonbenzodiazepine agents for improving adherence to CPAP therapy in patients with OSA who complain of insomnia symptoms has not been documented. One study comparing the use of 10 mg of zolpidem, placebo, and standard therapy (no hypnotic or placebo pill) in men with OSA did not show greater CPAP usage, compared with placebo and standard therapy.43 In contrast, administration of 3 mg of eszopiclone for the first 14 nights of CPAP use in adults newly diagnosed with OSA has been shown to improve CPAP adherence and lead to lower discontinuation rates at 6-month follow-up, compared with placebo.47 The use of hypnotics for those initiating CPAP treatment appears to be safe and may be beneficial in facilitating better CPAP tolerance and improving adherence, especially for patients who report difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep.

Insomnia and CPAP Adherence

CPAP is the conventional therapy for most patients with OSA, and its use has been shown to be associated with improvements in sleep quality, cognitive function, and quality of life and reductions in daytime sleepiness and respiratory disturbances.48 Adherence to CPAP is often poor, with 29% to 83% of patients reporting using CPAP for less than 4 hours per night.49–52 Research investigating the association between comorbid insomnia and CPAP use in patients with OSA has not been conducted. Insomnia may have direct or indirect effects on CPAP adherence. Patients with OSA and insomnia may have more difficulty adhering to CPAP because of increased awareness of the mask due to frequent awakenings and an inability to initiate or return to sleep with the mask in place. Psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and depression, often coexist with insomnia and may also play a role in CPAP adherence. For example, anxious patients may be more likely to have claustrophobia, which is associated with poor CPAP adherence.53 In 1 study, almost one third (30%) of participants with OSA and comorbid insomnia who showed resistance to using CPAP therapy reported having a history of claustrophobia.54

Early CPAP use is predictive of later use55; therefore, establishing an optimal pattern of adherence at the initiation of CPAP therapy is crucial for patients with OSA and insomnia who may have particular difficulty accepting and adhering to CPAP. In a recent pilot study (PAP-NAP), a combination of psychological and physiologic treatments were conducted prior to a full-night of positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy titration in a sample of patients with SDB and insomnia who had psychiatric symptoms or disorders and who manifested a resistance to PAP therapy.4 The treatments included pretest instructions on how to prepare for the study, desensitization to the masks and pressurized airflow through emotional processing and mental imagery, PAP therapy hookup in the laboratory if needed, and an opportunity for patients to use the PAP therapy for more than 1 hour and have the potential to fall asleep with the mask in place in the laboratory. The 39 patients completing the PAP-NAP study, as compared with historical controls, were more likely to complete the overnight titrations (90% vs 63%), fill the PAP therapy prescriptions for home use (85% vs 35%), and maintain regular use of PAP therapy (67% vs 23%).54 Acclimating patients with OSA and comorbid insomnia to CPAP therapy may improve the likelihood of patients regularly using CPAP. A key element to facilitating adherence to CPAP therapy may also be to address comorbid insomnia symptoms using a hypnotic agent, CBT, or a combination thereof prior to the initiation of CPAP.

CHALLENGES AND FUTURE RESEARCH

Evaluation of Comorbid Insomnia and OSA

The evaluation of comorbid insomnia in OSA can be challenging, given that symptoms of these 2 conditions overlap substantially and that methods for evaluation are similar. Sleep disorder nosologies56,57 also present limitations for the evaluation of comorbid insomnia and OSA. General insomnia in both the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd edition (ICSD-2)56 and the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for Insomnia57 is defined by the following general criteria: (A) 1 or more sleep-related complaints: difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, waking up to early, or chronically nonrestorative or poor quality sleep; (B) above sleep difficulty occurs despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep; and (C) at least 1 daytime impairment related to the nighttime sleep difficulty, such as daytime sleepiness or fatigue. The ICSD-256 criteria for the diagnosis of OSA overlap with the above ICSD-2 criteria for general insomnia, such that complaints of unintentional sleep episodes during wakefulness, daytime sleepiness, unrefreshing sleep, fatigue, and insomnia are included as criteria. The RDC for Insomnia57 proposes the following criteria for diagnosing insomnia related to sleep apnea: (A) individual meets criteria for insomnia disorder; (B) polysomnography shows more than 5 respiratory events per hour of sleep that meet current definitional criteria for apneas, hypopneas, or respiratory effort-related arousals; and (C) medical disorders, mental disorders, and any coexisting sleep disorder cannot completely account for the insomnia. Similar to the ICSD-256 criteria for OSA, the RDC57 criteria for insomnia related to sleep apnea require clinicians to decide whether sleep complaint(s) and daytime impairment(s) are due to frequent arousals and sleep fragmentation associated with OSA or if they are representative of insomnia. For this reason, the 2005 National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science conference on insomnia58 recommended that “comorbid insomnia” may be a more appropriate term than “secondary insomnia” or “insomnia due to.”

Recently published clinical guidelines for the evaluation of chronic insomnia59 suggest that 3 major groupings of insomnia can be considered when diagnosing insomnia and insomnia related-disorders: insomnia associated with other sleep disorders; insomnia related to medical or psychiatric disorders or drug or substance use; and primary insomnias, including idiopathic, paradoxical, and psychophysiological insomnia. Furthermore, comorbid insomnias and multiple insomnia diagnoses may coexist. In patients with diagnosed OSA, identifying other medical or psychiatric disorders that may cause sleep difficulties will be important for identifying additional etiologies of insomnia complaints. Assessment of learned negative sleep behaviors—including spending more time in bed to “catch up” on sleep; eating, exercising, or smoking before bed; and watching television, using a computer, or “clock watching” when in bed or in the bedroom—and cognitive distortions is essential for evaluating patients for primary insomnia disorders.

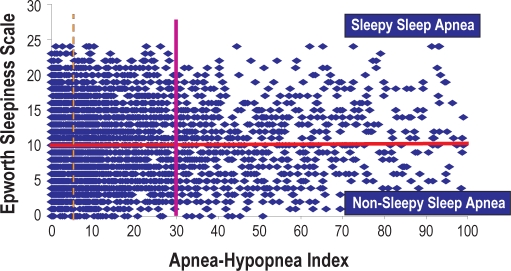

Polysomnography is not routinely used in the evaluation of chronic insomnia. However, in cases in which pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy are ineffective in ameliorating insomnia symptoms, patients should be referred for polysomnography to be evaluated for OSA. Patients with cooccurring insomnia and OSA are a challenging patient population for evaluation and treatment. It is likely that comorbid insomnia in OSA is a discreet phenotype similar to the sleepy and nonsleepy phenotype previously reported in OSA (Figure 2).60–62 The degree to which the comorbid insomnia-OSA phenotype coexist with the sleepy-nonsleepy phenotype is unknown. Multidisciplinary collaboration among sleep specialists and psychiatrists and psychologists will likely yield the most successful outcomes.

Figure 2.

The relationship between self-reported sleepiness and sleep apnea.

Depicted are data from the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, which is administered as part of the standard intake at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Sleep Medicine Center. Data were collected from 4653 consecutive patients over 5 years.

Treatment of Comorbid Insomnia and OSA

The optimal strategy for adequately treating coexisting insomnia and OSA remains unclear given the limited research examining this topic. The 2 studies that examined sequential OSA therapy and CBT suggest that concurrent treatment for both sleep disorders may be the best treatment approach.35,36 However, the treatment options for insomnia and OSA present many challenges. Treatment of OSA in patients with insomnia may be difficult because CPAP therapy might increase awakenings, thus perpetuating insomnia symptoms. Additionally, patients with insomnia may be experiencing hyperarousal or anxiety, which may impede the initiation and continuation of CPAP therapy.

As with treatments for OSA, treatments for insomnia also present challenges for patients and care providers. The efficacy of the long-term use of hypnotics has not been evaluated in patients with OSA. Side effects of benzodiazepines—including habituation, dependency, rebound effects, and withdrawal—may pose potential problems. Benzodiazepines prolong the duration of SDB events.34,40 Nonbenzodiazepine agents appear to have little or no effect on respiration and have fewer side effects and drug interactions than do benzodiazepines. Preliminary investigations into the efficacy of nonbenzodiazepine agents in patients with OSA suggest that these hypnotics may improve patient tolerance of CPAP and increase total sleep time and sleep continuity, thus helping to facilitate better more-effective CPAP titration.42,44–45

CBT has been shown in numerous studies to be effective in improving insomnia symptoms in those with primary and comorbid insomnia.63,64 Nonetheless, CBT is an intensive intervention requiring a high degree of motivation on the patient's behalf. Future treatment studies in comorbid insomnia and OSA are needed. Sequenced studies with CPAP therapy, CBT, and hypnotics will provide greater insight into the optimal treatment strategies for patients with comorbid insomnia and OSA. Additionally, clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of the chronic use of nonbenzodiazepine agents on insomnia symptoms in patients with insomnia and OSA are warranted.

Future Research

Insomnia and OSA are 2 of the most prevalent sleep disorders; thus, we would expect some degree of coexistence within patients. However, the high prevalence of comorbid insomnia and OSA found in available studies6–12 suggests that these disorders exacerbate one another and, when unaddressed, represent a barrier to effective overall treatment of the combined sleep disturbance. One could assume that daytime sleepiness often reported by patients with OSA may decrease the likelihood of insomnia symptoms or that the hyperaroused state of insomnia could reduce upper airway collapsibility. However, OSA could exacerbate insomnia symptoms as a result of sleep fragmentation and poor sleep quality.9 Patients with OSA have reported fear of dying during sleep, which could potentially result in a fear of sleep that could present as psychophysiologic insomnia.65 Alternatively, sleep fragmentation that is commonly associated with insomnia may worsen OSA by increasing lighter stages of non-rapid eye movement sleep or by negatively affecting upper-airway muscle tone.66 Insomnia may also be a potential symptom of OSA; in particular, sleep maintenance insomnia could be the product of OSA-provoked arousals.6 In a recent review, Beneto67 hypothesized that activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and its impact on the metabolic syndrome may be a potential link between insomnia and OSA. Sleep fragmentation resulting from OSA and, potentially, insomnia has been suggested to increase sympathetic activity and activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Understanding the nature of the relationship between insomnia and OSA may help to inform treatment strategies for patients with both disorders.

The clinical presentation and treatment of these coexisting sleep disorders requires additional research. Thus far, studies examining comorbid insomnia and OSA have identified patients with 1 of the conditions and then examined the prevalence of the other condition in the sample, consequently making it difficult to truly determine the prevalence of OSA in insomnia or vice versa. Variability in the definitions of insomnia and OSA in available studies also prohibits us from determining the true overlap of these conditions. For example, frequent arousals may be classified as insomnia when they could be due to OSA, and, as such, many patients with OSA could be misclassified as having sleep-maintenance insomnia. To obtain a more accurate prevalence of comorbid insomnia and OSA, it may be helpful to have a broad sample of patients without preclassification as having either OSA or insomnia undergo polysomnography. More precise phenotyping of clinical and polysomnographic features of comorbid insomnia and OSA using population and clinical studies is needed.

Insomnia and OSA are risk factors for cardiovascular disease.23,28 To date, investigations into the impact of comorbid insomnia and OSA on cardiovascular risk and other health outcomes have yet to be conducted. Understanding the health impact of comorbid insomnia and OSA is important for furthering our understanding of this growing patient population.

Insomnia is a symptom of psychiatric disorders and also a risk factor for the development of these disorders.32,33 Patients with OSA who also report having insomnia symptoms have a higher rate of psychiatric comorbidities than do patients with only OSA. In these studies, no differences in depression symptoms were found between patients with insomnia and OSA and those with only insomnia. Psychiatric comorbidities may contribute to the occurrence of insomnia in patients with OSA. Investigations into the potential role of psychiatric disorders as a contributing factor in the association between insomnia and OSA are needed.

The association between insomnia and CPAP adherence is an important, yet unexplored, research area. Some interesting questions about this potential relationship include whether comorbid insomnia negatively impacts CPAP adherence, whether treatment of OSA with CPAP can ameliorate insomnia symptoms, and the effect of comorbid insomnia on the efficacy of or outcomes associated with CPAP among those who are compliant. Understanding the role of insomnia in the treatment of OSA will be critical for the management of patients with comorbid insomnia and OSA.

CONCLUSIONS

Although insomnia and OSA frequently coexist, the prevalence of comorbid insomnia and OSA varies, primarily because of the variability in how insomnia and OSA are defined and characterized. It seems likely that concurrent treatment of insomnia and OSA would be the best treatment approach, but additional research is needed to determine the effectiveness of combination treatment in this patient population. Understanding the potential impact of insomnia on CPAP therapy will be important for the successful long-term disease management of OSA in patients with comorbid insomnia and OSA.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Buysse has received research support from Sepracor; has consulted for Actelion, Arena, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Neurocrine, Neurogen, Pfizer, Respironics, Sanofi-Aventis, Sepracor, Servier, Somnus Therapeutics, Stress Eraser, Takeda, and Transcept Pharmaceuticals; and has helped to produce CME materials and has given paid CME lectures indirectly supported by industry sponsors. Dr. Strollo has received research support from ResMed Corp. and Respironics. Dr. Luyster has indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by NIH grants HL082610 and MH024652.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonnet MH, Arand DL. Hyperarousal and insomnia: state of the science. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riemann D, Spiegelhadler R, Feige B, et al. The hyperarousal model of insomnia: a review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapur VK, Baldwin CM, Resnick HE, Gottlieb DJ, Nieto FJ. Sleepiness in patients with moderate to severe sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep. 2005;28:472–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mediano O, Barcelo A, de la Pena M, Gozal D, Agusti A, Barbe F. Daytime sleepiness and polysomnographic variables in sleep apnoea patients. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:110–3. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00009506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roure N, Gomez S, Mediano O, et al. Daytime sleepiness and polysomnography in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Sleep Med. 2008;9:727–31. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung KF. Insomnia subtypes and their relationships to daytime sleepiness in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Respiration. 2005;72:460–5. doi: 10.1159/000087668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gooneratne NS, Gehrman PR, Nkwuo JE, et al. Consequences of comorbid insomnia symptoms and sleep-related breathing disorder in elderly subjects. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1732–38. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.16.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guilleminault C, Palombini L, Poyares D, Chowdhuri S. Chronic insomnia, postmenopausal women, and sleep disordered breathing: part 1. Frequency of sleep disordered breathing in a cohort. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:611–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krakow B, Melendrez D, Ferreira E, et al. Prevalence of insomnia symptoms in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Chest. 2001;120:1923–29. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.6.1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krell SB, Kapur VK. Insomnia complaints in patients evaluated for obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2005;9:104–10. doi: 10.1007/s11325-005-0026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lichstein KL, Riedel BW, Lester KW, Aguillard RN. Occult sleep apnea in a recruited sample of older adults with insomnia. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:405–10. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith S, Sullivan K, Hopkins W, Douglas J. Frequency of insomnia report in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) Sleep Med . 2004;5:449–56. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quan SF, Gillin JC, Littner MR, Shepard JW. Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: Recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. Sleep. 1999;22:662–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:97–111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, Taylor DJ, Bush AJ, Riedel BW. Quantitative criteria for insomnia. Behav ResTher. 2003;41:427–45. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger JD, Lichstein KL, Morin CM. Recommendations for a standard research assessment of insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29:1155–73. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.9.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daley M, Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Gregoire JP, Savard J, Baillargeon L. Insomnia and its relationship to health-care utilization, work absenteeism, productivity and accidents. Sleep Med. 2009;10:427–38. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LeBlanc M, Beaulieu-Bonneau S, Merette C, Savard J, Ivers H, Morin CM. Psychological and health-related quality of life factors associated with insomnia in a population-based sample. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:157–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baldwin CM, Griffith KA, Nieto FJ, O'Connor GT, Walsleben JA, Redline S. The association of sleep-disordered breathing and sleep symptoms with quality of life in the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2001;24:96–105. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mulgrew AT, Ryan CF, Fleetham JA, et al. The impact of obstructive sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness on work limitation. Sleep Med. 2007;9:42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris RG, Glozier N, Ratnavadivel R, Grunstein, RR Obstructive sleep apnea and depression. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13:437–44. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulgrew AT, Nasvadi G, Butt A, et al. Risk and severity of motor vehicle carshes in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea. Thorax. 2008;63:536–41. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.085464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellen RLB, Marshall SC, Palayew M, Molner FJ, Wilson KG, Man-Son-Hing M. Systematic review of motor vehicle crash risk in persons with sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young T, Blustein J, Finn J, Palta M. Sleep-disordered breathing and motor vehicle accidents in a population-based sample of employed adults. Sleep. 1997;20:608–613. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.8.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powell NB, Schechtman KB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C, Chiang RPY, Weaver EM. Sleep driver near-misses predict accident risks. Sleep. 2007;30:331–342. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leger D, Massuel MA, Metlaine A The Sisyhe Study Group. Professional correlates of insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29:171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lanfranchi PA, Pennestri MH, Fradette L, Dumont M, Morin CM, Montplaisir J. Nighttime blood pressure in normotensive subjects with chronic insomnia: implications for cardiovascular risk. Sleep. 2009;32:760–66. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.6.760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Bixler EO, Chrousos GP, Vela-Bueno A. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with a high risk for hypertension. Sleep. 2009;32:491–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.4.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1378–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional results of the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:19–25. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopez-Jimenez F, Sert Kuniyoshi FH, Gami A, Somers VK. Obstructive sleep apnea: implications for cardiac and vascular disease. Chest. 2008;133:793–804. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neckelmann D, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Chronic insomnia as a risk factor for developing anxiety and depression. Sleep. 2007;30:873–80. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.7.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohayon MM, Roth T. Place of chronic insomnia in the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guilleminault C, Eldridge FL, Dement WC. Insomnia with sleep apnea: a new syndrome. Science. 1973;181:856–58. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4102.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guilleminault C, Davis K, Huynh NT. Prospective randomized study of patients with insomnia and mild sleep disordered breathing. Sleep. 2008;31:1527–33. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.11.1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krakow B, Melendrez D, Lee SA, Warner TD, Clark JO, Sklar D. Refractory insomnia and sleep-disordered breathing: a pilot study. Sleep Breath. 2004;8:15–29. doi: 10.1007/s11325-004-0015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krakow B, Melendrez D, Sisley B, et al. Nasal dilator strip therapy for chronic sleep-maintenance insomnia and symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep Breath. 2006;10:16–28. doi: 10.1007/s11325-005-0037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanly P, Powles P. Hypnotics should never be used in patients with sleep apnea. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dolly FR, Block AJ. Effect of flurazepam on sleep-disordered breathing and nocturnal oxygen desaturation in asymptomatic subjects. Am J Med. 1982;73:239–43. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berry RB, Kouchi K, Bower J, Prosise G, Light RW. Triazolam in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:450–4. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.2.7842205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Camacho ME, Morin CM. The effect of temazepam on respiration in elderly insomniacs with mild sleep apnea. Sleep. 1995;18:644–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.8.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berry RB, Patel PB. Effect of zolpidem on the efficacy of continuous positive airway pressure as treatment for obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2006;29:1052–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.8.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bradshaw DA, Ruff GA, Murphy DP. An oral hypnotic medication does not improve continuous positive airway pressure compliance in men with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2006;130:1369–76. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.5.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lettieri CJ, Quast TN, Eliasson AH, Andrada T. Eszopiclone improves overnight polysomnography and continuous positive airway pressure titration: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Sleep. 2008;31:1310–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenberg R, Roach JM, Scharf M, Amato DA. A pilot study evaluating acute use of eszopiclone in patients with mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Med. 2007;8:464–70. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cirignotta F, Mondini S, Zucconi M, Gerardi R, Farolfi A, Lugaresi E. Zolpidem-polysomnographic study of the effect of a new hypnotic drug in sleep apnea syndrome. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1988;29:807–9. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lettieri CJ, Shah AA, Holley AB, Kelly WF, Chang AS, Roop SA. Effects of a short course of eszopiclone on continuous positive airway pressure adherence. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:696–702. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giles TL, Lasserson TJ, Smith BJ, White J, Wright J, Cates CJ. Continuous positive airways pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD001106. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001106.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russo-Magno P, O'Brien A, Panciera T, Rounds S. Compliance with CPAP therapy in older men with obstructive sleep apnea. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1205–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weaver TE, Grunstein RR. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: the challenge to effective treatment. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:173–8. doi: 10.1513/pats.200708-119MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hui DS, Choy DK, Li TS, et al. Determinants of continuous positive airway pressure compliance in a group of Chinese patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2001;120:170–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.1.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sin DD, Mayer I, Man GC, Pawluk L. Long-term compliance rates to continuous positive airway pressure in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2002;121:430–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.2.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chasens ER, Pack AI, Maislin G, Dinges DF, Weaver TE. Claustrophobia and adherence to CPAP treatment. West J Nurs Res. 2005;27:307–321. doi: 10.1177/0193945904273283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krakow B, Ulibarri V, Melendrez D, Kikta S, Togami L, Haynes P. A daytime, abbreviated cardio-respiratory sleep study to acclimate insomnia patients with sleep disordered breathing to positive airway pressure (PAP-NAP) J Clin Sleep Med . 2008;4:212–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Budhiraja R, Parthasarathy S, Drake CL, et al. Early CPAP use identifies subsequent adherence to CPAP therapy. Sleep. 2007;30:320–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.The International Classifica-tion of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic & Coding Manual, 2nd ed. West-chester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Edinger JD, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR, et al. Derivation of research diagnostic criteria for insomnia: report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine work group. Sleep. 2004;27:1567–97. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement on Manifestations and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2005. Jun, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, Dorsey C, Sateia M. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:487–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kapur VK, Baldwin CM, Resnick HE, Gottlieb DJ, Nieto FJ. Sleepiness in patients with moderate to severe sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep. 2005;28:472–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mediano O, Barcelo A, de la Pena M, Gozal D, Agusti A, Barbe F. Daytime sleepiness and polysomnographic variables in sleep apnoea patients. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:110–3. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00009506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roure N, Gomez S, Mediano O, et al. Daytime sleepiness and polysomnography in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Sleep Med. 2008;9:727–31. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Edinger JD, Means MR. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for primary insomnia. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:539–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stepanski E, Rybarczyk B. Emerging research on treatment and etiology of secondary or comorbid insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brostrom A, Johansson P, Stromberg A, Albers J, Martensson J, Svanborg E. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome—patients' perceptions of their sleep and its effects on their life situation. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57:318–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Series F, Roy N, Marc I. Effects of sleep deprivation and sleep fragmentation on upper airway collapsibility in normal subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:481–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.2.8049833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Beneto A, Gomez-Siurana E, Rubio-Sanchez P. Comorbidity between sleep apnea and insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13:287–93. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]