Abstract

Since Medicare first implemented the home care Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) in 1999, we have learned a great deal about depression among the homebound elderly. First, we know that major depression is a highly prevalent illness in home care. With depression rates at almost 15%, home care—along with nursing homes—has among the highest rates of any healthcare setting (Bruce et al., 2002; Parmelee et al., 1992; Jones et al., 2003).

When we include minor and other subsyndromal depressions, the prevalence increases to approximately one-third of all geriatric home healthcare patients (Bruce et al., 2002; Ell, 2007). Amid the other illnesses (often multiple) with which these patients are struggling, depression may go undetected and is likely to be undertreated (Bruce et al., 2002). In addition to the debilitating symptoms directly caused by major depression, the illness also has a significant impact on a number of other health outcomes. Research has found that depression reduces degree of recovery from hip fractures and cancer, increases mortality from myocardial infarction and cancer, and is associated with declines in functioning and poorer physical health (Dickens et al., 2008; Lenze et al., 2004; Onitilo et al., 2006; Prieto et al, 2005; Rumsfeld et al., 2005). Work by our group also has found that geriatric depression is associated with adverse events like falls and hospitalization (Byers et al., 2008; Sheeran et al., 2004; Sheeran et al., 2010).

Although depression traditionally has gone underdetected and undertreated in home care, our group and others have demonstrated that with training and support, community health nurses can effectively identify and refer patients for treatment (Bruce et al., 2007; Ell et al., 2007; Flaherty et al., 1998). In our randomized trial of a depression assessment intervention, we found that not only did referral rates increase but patients showed significant clinical improvement (Bruce et al.). Work by Ell et al. found that depression could be identified in home care using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a nine-item screening instrument based on the diagnostic criteria for depression (Ell et al., 2005). Furthermore, Flaherty et al. found that targeting depression in home care can decrease hospitalization rates, consistent with our group's recent finding that depression is linked to short-term risk for hospitalization (Flaherty et al.).

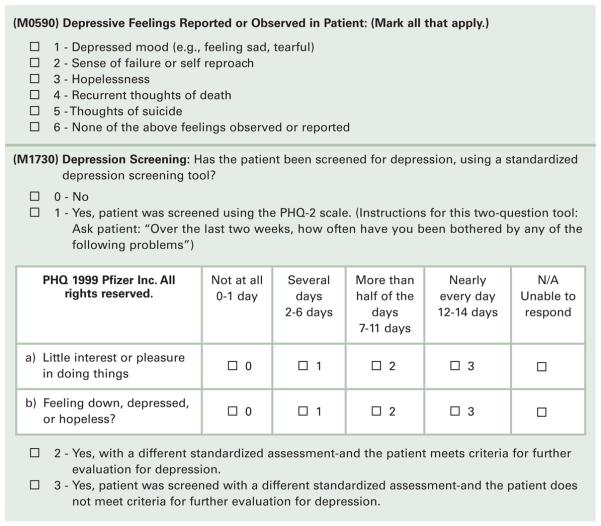

Given the growing body of evidence linking it to other clinical and adverse outcomes, geriatric depression has gained increased attention in home care. With the anticipated release of OASIS-C in January 2010, the current depression screening item, M0590, will be replaced by M1730, which encourages the use of standardized depression assessments (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2009). M1730 provides, as an option, the PHQ-2 (Table 1) to screen for depression. The PHQ-2 consists of the first two items of the PHQ-9 (see Figure 3 for the full PHQ-9), is a well-studied screening measure of depression often used in primary care, and presents a number of advantages over M0590 for identifying depression (Corson et al., 2004; Kroenke et al., 2003; Li, et al., 2007; Lowe et al., 2005). Thus, it offers a greater opportunity to identify depression and provide treatment to the homebound elderly than M0590.

Table 1.

The PHQ 1999 Pfizer Inc. All rights reserved.

| Over the past 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems? |

Not at All | Several days | More than half the days |

Nearly every day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Little interest or pleasure in doing things | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2. Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

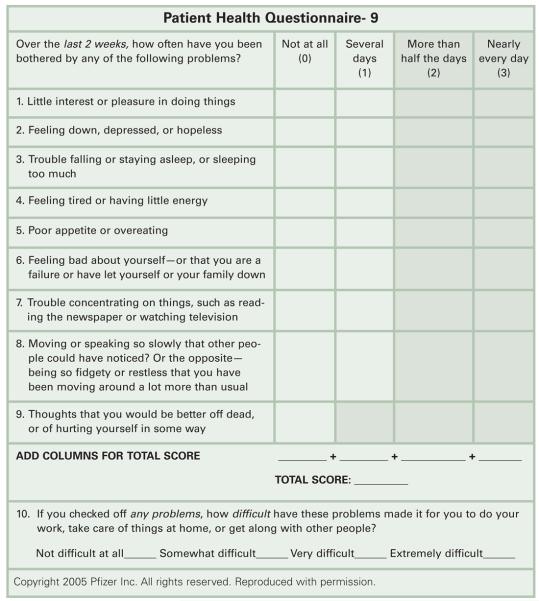

Figure 3.

The PHQ-9

As a tool developed for primary care, the usefulness of the PHQ-2 is dependent on administration methods that consider the special needs of elderly home care patients, who may have sensory, motor, cognitive, or other limitations. In this report we provide guidelines for using the PHQ-2 on the OASIS-C to screen for geriatric depression. The PHQ-2 can be used on the OASIS by any clinician responsible for admitting patients to home healthcare. Since this task typically is conducted by home health nurses or physical therapists, the term “clinician” in this article will refer to either.

What Is Major Depression?

Major depression is a clinical syndrome specified in both the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV, TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9; [ICD-9-CM: ICD-9, Clinical Modification, Sixth Edition, 1997]). There are two cardinal symptoms of major depression, sometimes referred to as “gateway” symptoms because at least one must be present in order for the patient to meet diagnostic criteria for the illness. These symptoms are (1) depressed mood and (2) diminished interest or pleasure in all, or nearly all, activities (anhedonia). These two cardinal symptoms are assessed by the PHQ-2. There are seven additional symptoms of major depression. All nine DSM-IV symptoms of major depression are listed in Table 2 below. To meet criteria for major depression, patients need at least five of these symptoms, at least one of which is a gateway symptom.

Table 2.

The DSM-IV symptoms of major depression

|

Gateway symptom of depression

Two debilitating diagnostic features of major depression are (1) persistence: lasting for at least 2 consecutive weeks in duration (and often lasting for months or more) and (2) pervasiveness: lasting most of the day, nearly every day, and causing distress or impairment in day-to-day functioning. These features of depression are also assessed by the PHQ-2.

M0590 and the New M1730 with the PHQ-2

The former OASIS item to screen for depression was M0590 (see Figure 1), which provided checklists for the clinician to endorse if symptoms of depression were identified. The value of this approach for identifying depression is that it includes several of the DSM-IV symptoms of depression and provides a means for the clinician (nurse or physical therapist) to note these symptoms while conducting the OASIS. However, there are a number of drawbacks to this item. First, the item only measured one of the two gateway symptoms: depressed mood. Although at one time the OASIS included a second measure that evaluated loss of interest or pleasure in activities (M0600), it is no longer required by Medicare. Second, there is no direction on how to ask the patient about depression. For clinicians having limited experience with geriatric depression, asking about these symptoms can seem daunting without some degree of guidance. Finally, M0590 does not assess symptom persistence and/or pervasiveness, important characteristics of major depression.

Figure 1.

Former OASIS-B1 M059 and upcoming OASIS-C M1730 with PHQ-2

The OASIS-C item, M1730 (see Figure 1), addresses many of these problems. First, M1730 is explicit about whether or not a standardized instrument was used to screen the patient for depression. It also provides for the use of other instruments, such as the Geriatric Depression Scale (Yesavage et al., 1982). By incorporating the PHQ-2 directly into M1730, a quick and valid measure is immediately available to the assessing clinician. Both of the gateway symptoms of depression are included: depressed mood and anhedonia (lack of interest/enjoyment in activities). The PHQ-2 also includes language that provides specific guidance for asking about depression. Additionally, it asks directly about persistence (“in the past 2 weeks”) and pervasiveness (number of days). M1730 also is specific about whether subsequent evaluation or treatment is needed: M1730_2 is to indicate if a standardized assessment was used and the patient does meet criteria for further depression evaluation, while M1730_3 is used if a standardized assessment was used and the patient does not meet criteria for further depression evaluation.

Finally, since the PHQ-9 and the PHQ-2 are gaining greater use in primary care, the PHQ-2 offers a “common language” by which a home health provider can discuss the patient's clinical status with the primary care physician. Note that M1730 does not specifically require the PHQ-2, however. The OASIS_C instructions emphasize that a different standardized measure can be used, and if so, the specific scoring guidelines of that measure should be used.

In summary, the new M1730 offers a number of advantages over M0590. These include: (1) inclusion of the two gateway symptoms of depression: depressed mood and lack of interest/pleasure in usual activities; (2) a quick and easy measure to administer on the spot; (3) guidance on how to ask about depression, (4) assessment of both persistence and pervasiveness, (5) the common language of a measure often used in primary care, (6) the flexibility to use other standardized measures of depression, and (7) explicit determination of whether the patient needs further depression evaluation.

Administering the PHQ-2 to Elderly Home Health Patients

The PHQ-2 consists of the first two items of the full nine-item PHQ-9. While the PHQ-9, as its name suggests, assesses all nine criteria for depression, the PHQ-2 assesses only the two gateway symptoms of depression: depressed mood and lack of interest/pleasure in activities (anhedonia). The stem question is, “Over the last two weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems?” This is followed by the two symptoms: (1) “Little interest or pleasure in doing things,” and (2) “Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless.” For a more comprehensive assessment, the PHQ-9 assesses the remaining seven symptoms of depression, but just the two items of the PHQ-2 have demonstrated good reliability and validity among primary care patients (Beaudin & Burchuk, 2004).

General Guidelines

There are a few general guidelines to consider when administering the PHQ-2 during the OASIS-C. First, the questions should flow naturally and comfortably in the context of the rest of the assessment. This can best be accomplished by being straightforward and direct when introducing the questions. This approach should not be foreign to a home health provider, who often must ask their patients about other personal aspects of health and functioning. For example, the clinician could say, “Now I'm going to ask you about your mood and your interest in activities,” or, “I'm going to ask you some questions about how you're feeling.”

Some nurses or therapists initially may not feel comfortable discussing mental health issues with their patients, even though it is included on the OASIS. However, in our work with numerous home health agencies, we have found that comfort level dramatically increases with practice and repetition. Indeed, clinicians who initially were quite hesitant to discuss depression with their patients reported that eventually the inquiry became no more difficult than evaluating other physical symptoms. It is important that the clinician discuss depression with the patient in a manner that conveys comfort with the topic, empathy, and professionalism. To the degree that she can convey ease with the topic, the patient will feel more at ease responding. As with any clinical skill, comfort with screening for geriatric depression comes with practice and experience.

It is important to screen for depression even if the patient is taking an antidepressant upon start of home care service. A common misconception is that because a patient is taking an antidepressant, the illness is being well managed, and that without the medication the patient would be even more depressed. However, the patient may have been started on a low dose of antidepressant to test tolerability, without any follow-up to increase the dose to a therapeutic level. Therefore, as with any other medication, dosing level and symptom status should be evaluated to ensure the depression is being adequately managed.

Dealing with Sensory, Motor, or Cognitive Impairment

The PHQ-2 (and PHQ-9) was designed to be completed as a paper-and-pencil measure in the waiting room of a primary care office. Although this remains an option in home care, the paper-and-pencil approach is less commonly used in this setting because home health providers often directly assess other symptoms (e.g., vital signs) or verbally review symptoms with their patients. Furthermore, many elderly patients may not have the visual or motor capacity to read and fill out a form. Thus, although capable patients certainly can complete a paper-and-pencil version of the PHQ-2, it is likely that the clinician will be directly asking many patients about their symptoms instead.

However, verbal administration creates a few challenges of its own. Most notably, cognitive impairment may hinder the patient's capacity to understand the questions. With more severe cases of cognitive impairment, the PHQ-2 may not be a feasible measure, and if this is the case, it should not be administered (see following sections for more discussion about the significant dementia). For mild cognitive impairment—or even no cognitive impairment—the questions may be challenging to comprehend when being read aloud. For example:

“Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems: little interest or pleasure in doing things. Not at all, several days, more than half the days, or nearly every day?”

When read aloud as written, this question asks the patient to process a great deal of information. We therefore recommend splitting the question into “bite size” pieces. The clinician can first ask about the presence of a symptom, then determine persistence (2 weeks or more), then determine pervasiveness (frequency of symptoms). For example:

“Have you had little interest or pleasure in doing things?” If yes…

“How long have you been feeling this way?” Or, “Have you been feeling like this for at least two weeks?” If 2 weeks or more…

“How often have you been feeling this way? Several days, more than half the days, or nearly every day?”

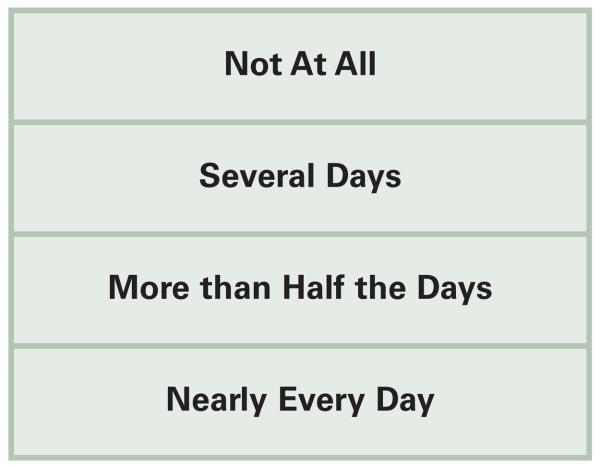

In this manner, the questions are not as potentially confusing and the clinician has more freedom to gather additional information about the nature of the patient's symptoms. When asking about frequency of symptoms, some patients may gain additional benefit from a (large print) response card, which the clinician can use to point to each frequency level. The patient then need only point to the correct response. A response card not only is good for providing greater structure and reducing confusion, but also can be useful for hearing impaired patients and the large print can be helpful for visually impaired patients. A sample large print response card is included in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Large Print PHQ Response Card

Severe Cognitive Impairment

Although the PHQ-2 is intended to be a brief screening measure among patients who are cognitively intact, the high frequency of dementia among the home care population warrants comment on this issue. First, among patients with substantial cognitive impairment (e.g., nonverbal patients), it clearly is not feasible to directly administer the PHQ-2. However, as with all illnesses, family members can be an important resource for patient evaluation. While the PHQ-2 can be used as a guide for talking with family members about patient depression, it should be used cautiously and with the knowledge that the measure may have limited validity. In these circumstances, the clinician may want to seek additional consultation with colleagues and, if available, mental health professionals. Assessing depression among the severely cognitively impaired is a notoriously difficult task, even for the most skilled geriatric mental health provider. While a full discussion on this issue is beyond the scope of this article, The Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia is a more appropriate tool to assess depression among this population (Alexopoulos et al., 1988).

Medical Comorbidity and the PHQ-9

Some of the symptoms of depression listed in Table 1, such as sleep or appetite disturbance, are physical in nature. Although the PHQ-2 does not include any of these physical symptoms of depression, the PHQ-9 does (see Figure 3). Therefore, we provide additional guidelines for those clinicians who follow up positive scores on the PHQ-2 with administration of the remainder of the PHQ-9 items.

Elderly home health patients often have more than one medical condition. Indeed, a study of a large sample of elderly patients in a variety of healthcare settings found that the average number of comorbid medical conditions was 3.4 (Unutzer et al., 1997). Importantly, independent of medical illness, depression was associated with poorer mental functional status, disability, quality of life, and healthcare costs.

However, it can often be extremely difficult to determine whether certain physical symptoms are caused by depression, by medical illness, or by both. Physical symptoms of depression, such as fatigue, sleep disturbance, appetite or weight change, and psychomotor disturbance can also be related to medical comorbidities. Differentiating these differing causes requires the advanced diagnostic skills of a geriatric mental health practitioner. However, screening for geriatric depression does not require these advanced skills. Rather, if the patient reports physical symptoms, they should be scored on the PHQ-9, regardless of possible cause. The differential diagnosis can be conducted by the mental health clinician or primary care doctor. It also is important to note that physical symptoms are inadequate to arrive at a diagnosis of depression. A patient must have one of the two gateway symptoms and may also have some of the other psychological symptoms (e.g., feelings of guilt or worthlessness).

Stigma and Ageism

Both healthcare providers and patients themselves are at risk for not identifying geriatric depression due to ageism and stigma. Ageism refers to a range of negative attitudes, beliefs, and stereotypes about older adults that can result in unfair or discriminatory behavior. Stigma can be defined as “a mark of shame or discredit” associated with mental illness (Rusch et al., 2005; Sirey et al., 2001).

Ageism can refer to a wide range of negative attitudes and behavior toward older adults. For example, both in medical and in nonmedical settings older adults can be viewed as having cognitive or physical impairments, regardless of their actual state. In contrast, ageism can also result in a tendency to normalize—and therefore ignore—real illnesses that require treatment. This is the most common manner in which ageism appears when assessing depression. Often patients, their families, and at times even healthcare providers believe that the older homebound patient “should” be depressed because of their circumstances (e.g., elderly, home bound, socially isolated, medically ill, often in pain, and functionally limited) and therefore do not take the symptoms seriously. However, there are far more people in these circumstances who are not depressed than those who are depressed. It is important that depression not be normalized or viewed as a “natural” or “expected” response to multiple risk factors. Rather, the risk factors should be viewed as “flags” to the clinician, prompting him/her to be alert for possible depression and, if found, treatment initiated.

It is also important for the clinician to make this distinction to patients and families when talking about geriatric depression. For example, the clinician could say, “You have a number of challenges, but this does not mean depression is inevitable. Depression is a medical illness with serious consequences. Depression can be treated, so that you can better handle those challenges.”

Many patients can view depression or mental illness as a shameful state or a sign of “mental weakness.” Alternatively, patients may erroneously think they are going to be involuntarily hospitalized (“put away”). These beliefs can result in a denial of symptoms. Older adults may be especially susceptible to this problem, as they lived much of their lives in an era when mental illness was highly stigmatized. There are a number of ways in which to respond to this challenge. First, patients are less likely to stigmatize the other gateway symptom, lack of interest or enjoyment in activities. Therefore, the clinician may wish to ask about this symptom first. A more direct approach is to reassure the patient that depression is not a weakness or shameful. Alternatively, when asking about depressed mood (item 2 on the PHQ-2) the clinician can use a variety of terms, such as “blue,” “down in the dumps,” “low in spirits,” and so forth. During the course of conducting the OASIS, the patients may spontaneously provide language that the clinician can use. For example, if a patient reports that she's “lost my laugh,” the clinician can immediately go to the PHQ-2 and ask how often this has bothered her in the past 2 weeks. Again, describing depression as a medical illness can help destigmatize it.

PHQ-2 Cutoff Scores

Among studies conducted in primary care centers with large samples, the PHQ-2 performed well as both a screening tool for identifying depression and a measure of depression severity (Li et al., 2007; Lowe et al., 2005). While these primary care studies cannot be considered directly applicable to home care when scoring and interpreting the PHQ-2, they do offer some guidelines from which to start.

The PHQ-2 consists of two items, each with a score ranging from 0 to 3 (see Figure 1). Thus, the total score of the PHQ-2 can range from 0 to 6. The studies comparing the PHQ-2 to patients with depression diagnoses found that a score of 3 or greater correctly identified 87% of patients who were depressed (sensitivity) and 78% of patients who were not depressed (specificity) (Li et al., 2007; Lowe et al., 2005). This was for both major depression and any depression (e.g., minor) depression, and was found to be the best balance between sensitivity and specificity. With the caveat that further research is needed to evaluate validity and cutoff scores for elderly home care patients, it is recommended that patients with a PHQ-2 score of 3 or higher be referred for further evaluation.

It is important to note that local agency resources, patient characteristics, and need for services may influence cutoff scores that an agency ultimately chooses. The optimum cutoff will depend on the goals of the agency for depression screening in terms of both identifying the maximum number of depressed patients and reducing the number of unneeded referrals. Therefore, it is recommended that a cutoff score of 3 be a starting point and that, if necessary, agencies adjust the cutoff score up or down as needed. For example, if a cutoff of 3 is found to be identifying a large number of patients who ultimately are not depressed, an agency may wish to raise the score to 4 in order to reduce the unnecessary workload on mental health staff. Conversely, if a cutoff score of 3 appears to be missing depressed patients, the agency may wish to lower the cutoff score to 2.

Documentation and Receiving “Credit” for Providing High-Quality Depression Care

The new OASIS-C provides a few other opportunities to document depression care by the clinician and the agency. These are in the OASIS-C Plan of Care Synopsis, M2250, and the Discharge M2400, which is completed at discharge or when the patient is hospitalized. The Plan of Care Synopsis, M2250, specifically identifies depression as an illness to be addressed by the agency: “Plan/Intervention: Depression intervention(s) such as medication, referral for other treatment, or a monitoring plan for current treatment” (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2009). Home health agencies can therefore document the plan to provide depression disease management in the same manner they would for other interventions (such as diabetic foot care, for example).

Discharge Intervention Synopsis, M2400, also includes depression as an illness to be addressed “since the previous OASIS assessment.” The Medicare instructions for this item note that the item is used to track best practices, with an emphasis on the fact that in order to score “yes” on M2400 items, the illness has to be both (1) included in the physician-ordered plan of care and (2) implemented. An advantage of this item is that, as with other emergent medical needs (e.g., wounds), it allows the agency to (1) document that depression was identified at the previous OASIS or later, (2) that the physician was contacted and an order for care obtained, and (3) that care was provided. The item also recognizes that depression care management can include a wide range of activities. This includes not only medication adjustments or mental health referrals but also the typical activities of symptom monitoring, medication management, and teaching.

Finally, it is important to note that the “N/A” option on M2400 is also a key indicator of quality depression care for the following reason: “N/A” may be selected if the patient was both assessed using a standardized instrument (such as the PHQ-2 on M1730) and found to have no depression. Ruling out an illness is just as important as identifying it. Thus, the agency and clinician “get credit” for conducting effective screening and ruling out depression.

Conclusion

It is important to know that depression is a treatable illness, with treatment studies showing that up to 60% to 80% of patients respond when provided with adequate depression care (Alexopoulos et al., 2005; Mulsant et al., 2001; Charney et al., 2003). As with any new measure or protocol, adaptation will take some time and effort, and non–mental-health staff are likely to have some initial unease about asking these two questions. However, in our work with numerous home health agencies, clinicians gradually have become more comfortable asking about depression. Many, in fact, have anecdotally reported that depression screening has become “routinized,” in that they view depression screening as a clinical task no different than assessing other diseases commonly encountered in home care. Moreover, they also report marked satisfaction in seeing their patients improve. Practice at this level of quality not only improves the debilitating and sometimes lethal outcomes of depression, but may also positively impact treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and adverse events, such as falls and hospitalization.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health grants K01MH073783 to Dr. Sheeran and R01MH082425 to Dr. Bruce.

Footnotes

The authors of this article have no significant ties, financial or otherwise, to any company that might have an interest in the publication of this educational activity.

Contributor Information

Thomas Sheeran, Assistant Professor of Psychology in Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, New York..

Catherine F. Reilly, Project Coordinator in Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, New York..

Patrick J. Raue, Associate Professor of Psychology in Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, NY..

Mark I. Weinberger, postdoctoral fellow in Geriatric Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, NY.

Judith Pomerantz, consultant for Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, NY..

Martha L. Bruce, Professor of Sociology in Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College White Plains, New York..

REFERENCES

- Alexopoulos GS, Abrams RC, Young RC, Shamoian CA. Cornell scale for depression in dementia. Biological Psychiatry. 1988;23(3):271–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos GS, Katz IR, Bruce ML, Heo M, Ten Have T, Raue P, et al. Remission in depressed geriatric primary care patients: A report from the PROSPECT study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(4):718–724. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.718. 3rd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. C. o. N. a. S. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudin CL, Burchuk R. Clinical practice guidelines for treating depression in primary care. Managed Care. 2004;13(Suppl. 2 Depression):17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Brown EL, Raue PJ, Mlodzianowski AE, Meyers BS, Leon AC, et al. A randomized trial of depression assessment intervention in home health care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55(11):1793–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, McAvay GJ, Raue PJ, Brown EL, Meyers BS, Keohane DJ, et al. Major depression in elderly home health care patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(8):1367–1374. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers A, Sheeran T, Mlodzianowski A, Meyers B, Nassisi P, Bruce M. Depression and risk for adverse falls in older home health care patients. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2008;1(4):245–251. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20081001-03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Outcome and Assessment Information Set-C (OASIS-C) 2009 Retrieved 11/9/09 from http://www.cms.hhs.gov/HomeHealthQuality Inits/06_OASISC.asp.

- Charney DS, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Lewis L, Lebowitz BD, Sunderland T, Alexopoulos GS, et al. Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance consensus statement on the unmet needs in diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders in late life. Archives of General. 2003;60(7):664–672. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corson K, Gerrity MS, Dobscha SK. Screening for depression and suicidality in a VA primary care setting: 2 items are better than 1 item. American Journal of Managed Care. 2004;10(11, Pt. 2):839–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens C, McGowan L, Percival C, Tomenson B, Cotter L, Heagerty A, et al. New onset depression following myocardial infarction predicts cardiac mortality. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(4):450–455. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816a74de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Unutzer J, Aranda M, Gibbs NE, Lee P-J, Xie B. Managing depression in home health care: A randomized clinical trial. Home Health Care Services Quarterly. 2007;26(3):81–104. doi: 10.1300/J027v26n03_05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Unutzer J, Aranda M, Sanchez K, Lee PJ. Routine PHQ-9 depression screening in home health care: depression, prevalence, clinical and treatment characteristics and screening implementation. Home Health Care Services Quarterly. 2005;24(4):1–19. doi: 10.1300/J027v24n04_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty JH, McBride M, Marzouk S, Miller DK, Chien N, Hanchett M, et al. Decreasing hospitalization rates for older home care patients with symptoms of depression. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1998;46(1):31–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICD-9-CM: International classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification. 6th ed U.S. Department of Human Services; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jones R, Marcantonio E, Rabinowitz T. Prevalence and correlates of recognized depression in US nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(10):1404–1409. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Munin MC, Dew MA, Rogers JC, Seligman K, Mulsant BH, et al. Adverse effects of depression and cognitive impairment on rehabilitation participation and recovery from hip fracture. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;19(5):472–478. doi: 10.1002/gps.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Friedman B, Conwell Y, Fiscella K. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2) in identifying major depression in older people. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2007;55(4):596–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe B, Kroenke K, Grafe K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2) Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2005;58(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Nebes R, Miller MD, Sweet RA, Stack J, et al. A twelve-week, double-blind, randomized comparison of nortripty-line and paroxetine in older depressed inpatients and outpatients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):406–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onitilo AA, Nietert PJ, Egede LE. Effect of depression on all-cause mortality in adults with cancer and differential effects by cancer site. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2006;28(5):396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmelee PA, Katz IR, Lawton MP. Incidence of depression in long-term care settings. Journal of Gerontology. 1992;47(6):M189–M196. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.6.m189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto JM, Atala J, Blanch J, Carreras E, Rovira M, Cirera E, et al. Role of depression as a predictor of mortality among cancer patients after stem-cell transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(25):6063–6071. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumsfeld JS, Jones PG, Whooley MA, Sullivan MD, Pitt B, Weintraub WS, et al. Depression predicts mortality and hospitalization in patients with myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure. American Heart Journal. 2005;150(5):961–967. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch N, Angermeyer MC, Corrigan PW. Mental illness stigma: Concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. European Psychiatry. 2005;20(8):529–539. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran T, Brown EL, Nassisi P, Bruce ML. Does depression predict falls among home health patients? Using a clinical-research partnership to improve the quality of geriatric care. Home Healthcare Nurse. 2004;22(6):384–389. doi: 10.1097/00004045-200406000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran T, Byers AL, Bruce ML. Depression increases short-term risk of hospitalization among geriatric home healthcare patients. Psychiatric Services. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.1.78. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Friedman SJ, Meyers BS. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(12):1615–1620. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unutzer J, Patrick DL, Simon G, Grembowski D, Walker E, Rutter C, et al. Depressive symptoms and the cost of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older. A 4-year prospective study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277(20):1618–1623. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540440052032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1982;17(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]