Abstract

Background

Neuromuscular blocking agents are an integral component of general anesthesia. In addition to their intended pharmacologic target on skeletal muscle nicotinic receptors, undesirable airway effects (i.e. bronchoconstriction) can result from neuromuscular blocking agents affinity for airway muscarinic receptors. We questioned whether two new members of a bisquaternary non-depolarizing muscle relaxant family, gantacurium and CW002, demonstrated detrimental effects of airway muscarinic receptors using an in vivo model in guinea pig airways.

Methods

Urethane anesthetized male guinea pigs were ventilated through a tracheostomy with continuous digital recordings of pulmonary inflation pressure and heart rate. The ED95 for muscle paralysis for gantacurium, CW002, cisatracurium and rapacuronium were defined in the guinea pig. Transient and reproducible changes in pulmonary inflation pressure and heart rate were recorded following vagal nerve stimulation or the intravenous injection of acetylcholine before and after pretreatment with cumulatively increasing concentrations of gantacurium, CW002, cisatracurium or a single concentration of rapacuronium.

Results

Gantacurium, CW002, cisatracurium and rapacuronium exhibited ED95 for muscle paralysis of 0.064 ± 0.0006, 0.012 ± 0.006, 0.10 ± 0.003, and 0.31 ± 0.05 mg/kg, respectively. Gantacurium, CW002 and cisatracurium were without effects on baseline pulmonary inflation pressures and were devoid of significant interactions with M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors in vivo.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that gantacurium and CW002 are devoid of significant effects at airway muscarinic receptors particularly M3 receptors on bronchial smooth musculature at doses several fold higher than those required for functional muscle paralysis.

Introduction

Neuromuscular blocking agents are utilized to facilitate tracheal intubation and to maintain muscle relaxation during many surgical procedures. In addition to their intended target, the nicotinic receptor on skeletal muscle, muscle relaxants can initiate bronchoconstriction via histamine release1,2, interaction with airway muscarinic receptors3–7 or anaphylaxis8–10. We have previously demonstrated that muscle relaxants that antagonize pre-junctional parasympathetic M2 muscarinic autoreceptors can potentiate vagal nerve induced bronchoconstriction6, a common event accompanying irritation of the upper airway during intubation and suctioning. Additionally, we have demonstrated that some muscle relaxants exhibit an additional detrimental effect on airway muscarinic receptors; potentiation of the effect of acetylcholine at airway smooth muscle M3 muscarinic receptors by a positive allosteric effect at this receptor4,5.

Histamine release is one known risk factor for bronchospasm and has been attributed to some neuromuscular blocking agents such as curare11–13, atracurium13 and mivacurium13. Instrumentation of the well-innervated upper trachea initiates an irritant reflex that results in the release of acetylcholine from parasympathetic nerves that activate M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors in airway smooth muscle, resulting in bronchoconstriction14. Typically ongoing acetylcholine release from parasympathetic nerves is terminated by acetylcholine acting on M2 muscarinic inhibitory auto-feedback receptors present in the presynaptic terminals of postganglionic parasympathetic nerves.15,16 However, non-depolarizing muscle relaxants are known to have differential antagonistic affinities for M2 muscarinic receptors.6,7 Agents that have a higher affinity for the M2 versus the M3 muscarinic receptor can lead to selective inhibition of M2 muscarinic auto-receptors on parasympathetic nerves during periods of parasympathetic nerve stimulation17 (e.g. intubation) and result in enhanced release of acetylcholine which then acts upon unopposed M3 muscarinic receptors in airway smooth muscle, facilitating bronchospasm. An additive detrimental effect of allosteric potentiation of acetylcholine’s effect on post-junctional M3 muscarinic receptors on airway smooth muscle was discovered with a now discontinued muscle relaxant, rapacuronium4,5.

Studies with rapacuronium and muscarinic receptors were originally pursued to identify the mechanism by which rapacuronium caused bronchoconstriction so that newly synthesized muscle relaxants intended for clinical use could be screened for these detrimental interactions with airway muscarinic receptors. A new family of bisquaternary non-depolarizing muscle relaxants that have advantageous clinical kinetic profiles (rapid onset, ultrashort and short duration, and immediate antagonism by cysteine) are currently in development18–20. Gantacurium (GW280430A) has not demonstrated detrimental airway effects in early clinical trials18 and animal studies suggest a lack of effect of gantacurium on cardiac M2 muscarinic receptors20 A second compound of intermediate duration in this family, CW002, has also demonstrated a limited cardiopulmonary side effect profile in animal studies as well as rapid reversibility by cysteine. However, neither of these previous studies were designed to detect with high sensitivity the potential of these new relaxants to interact with airway muscarinic receptors, nor were these studies designed to directly compare gantacurium and CW002 alongside rapacuronium, the relaxant which is now the standard for detrimental interactions with airway muscarinic receptors. We sought to evaluate the potential interaction of gantacurium and CW002 with airway muscarinic receptors using a well characterized in vivo guinea pig model of airway constriction. This type of airway safety evaluation is of key strategic importance in the development of new neuromuscular blocking drugs which may be used to facilitate intubation. A comparative lack of effect in these studies versus the now-established detrimental properties of rapacuronium would suggest an improved safety profile in reducing the possibility of reactive bronchospasm during airway instrumentation.

Materials and Methods

Male Hartley guinea pigs (approx. 400g) were used. Guinea pigs were handled in accordance with the standards established by the US Animal Welfare Acts set forth in the National Institutes of Health guidelines, and all protocols were approved by the Columbia University Animal Care and Use Committee (New York, New York).

Reagents

Powdered gantacurium (AV430A) was supplied by Avera Pharmaceuticals (San Diego, CA), and CW002 was supplied by Weill Cornell Medical College. The clinical formulation of rapacuronium (Organon, Roseland, NJ) and cisatracurium (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) were used in these studies. All drugs were serially diluted in physiologic saline for in vivo studies. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Animal Model

Protocols were performed as previously described5. Briefly, Hartley male guinea pigs (approx. 400g) were anesthetized with 1.7 g/kg intraperitoneal urethane. Depth of anesthesia was monitored by changes in respiratory rate and response to foot pinch before paralysis. Surgical intervention did not begin until there was an absence of response to foot pinch. A 20% increase in respiration rate or a withdrawal response to foot pinch before paralysis was taken as a potential indication of inadequate anesthesia at which time incremental doses of urethane (0.2 g/kg intraperitoneal) were given until respiratory rate or foot withdrawal was unresponsive to stimulation. The trachea was cannulated with a 1-inch and 16-gauge intravenous catheter, and the animal was ventilated by a positive pressure, constant volume animal ventilator (3ml tidal volume at 60 breaths/min) (model 683; Harvard Apparatus Co., South Natick, MA). Peak pulmonary inflation pressure (Ppi) was measured just proximal to the cannula through a side port via rigid plastic extension tubing connected independently to two pressure modules with differing ranges of sensitivity (TSD160B 0–12.5 cm H2O and TSD160C 0–25 cm H2O; Biopac Systems, Inc., Goleta, CA). Both jugular veins were cannulated with PE-50 tubing for the administration of drugs, at which time the animals were paralyzed with succinylcholine (170 µg · kg−1 · min−1). The carotid artery was cannulated with PE-50 tubing and connected to a pressure transducer in line with a Biopac TSD104A module for monitoring heart rate and blood pressure. Throughout the experiments, sympathetically mediated changes in hemodynamics (hypertension, tachycardia) were monitored as an indicator of the depth of anesthesia after muscle paralysis. A 20% increase in heart rate or systolic blood pressure was treated with incremental urethane (0.2 g/kg intraperitoneal). Both vagus nerves were tightly tied but not cut, and the distal ends were placed on shielded electrodes. In a separate group of animals ED95 for twitch suppression of sciatic nerve stimulation of gastrocnemius muscle response was measured for gantacurium, CW002, cisatracurium and rapacuronium. Animals were instrumented as above except that succinylcholine was omitted and the vagus nerves were not isolated. The tendon of the gastronemius muscle was surgically exposed and attached with a silk suture to an FT03 force transducer and preload was set at 50 g. Two 22 gauge needles were percutenously placed near the sciatic nerve to which electrodes were connected. Continuous DC square wave impulses (0.15 Hz, 2–10 V. 0.2 msec pulse width) were delivered from a Grass-Telefactor S88 stimulator, to achieve a maximal twitch response in each animal. All pressure transducers were connected to a Biopac MP100A acquisition system, and data were continuously captured using Acknowledge software, version 3.7.3 (Biopac Systems).

Determination of ED95 for gantacurium, CW002, cisatracurium and rapacuronium in the guinea pig

Following the establishment of the magnitude of the gastrocnemius twitch response, the potency of muscle paralysis of each muscle relaxant was tested in individual animals. CW002 and cistracurium were given as cumulatively increasing concentrations during continuous stimulation and recording of twitch responses. The subsequent dose of each muscle relaxant was given when the dimunition of the twitch from the previous dose had achieved a stable plateau (typically 5–10 minutes for CW002 and cisatracurium). Due to their relatively shorter duration of action, incrementally increasing doses of gantacurium and rapacuronium were given after the twitch response from the previous dose had totally returned to baseline values for 60 minutes. Dose response curves for twitch inhibition were calculated from 4 independent experiments from which 12 to 16 points were plotted. The percentage of twitch suppression was converted to logits and the ED95 for twitch blockade was calculated from the regression line.

Effects of muscle relaxants on vagal nerve stimulated- or intravenous acetylcholine-stimulated increases in pulmonary inflation pressure and heart rate

The effects of each dose of each muscle relaxant on airway and cardiac M2 muscarinic receptor function were assessed by the effect on the magnitude of the vagally induced increase in pulmonary inflation pressure and the inhibition of bradycardia, respectively. The effect of each dose of each muscle relaxant on postjunctional M3 muscarinic receptors (i.e. M3 muscarinic receptors on airway smooth muscle) was assessed by the effect on the magnitude of intravenous acetylcholine-induced increase in pulmonary inflation pressure. The potential ability of each dose of each muscle relaxant to release histamine was determine by assessing the effects of each dose of each muscle relaxant on baseline pulmonary inflation pressure3,5 in the absence of vagal nerve or intravenous acetylcholine stimuli.

Electrical stimulation of both vagus nerves (10–20 Hz, 10–20 V, 0.2-ms pulse duration, 10- to 12-s train duration) produced transient increases in Ppi and bradycardia. A single voltage was selected for each animal within a range of 10–20 V to yield similar increases in airway pressure between animals. The nerves were stimulated at approximately 10 min intervals alternating with injections of intravenous acetylcholine (5–12 µg/kg in a volume of 0.15 ml physiologic saline) approximately every 10 min to directly stimulate postjunctional muscarinic receptors on the heart and airway smooth muscle. The dose of intravenous acetylcholine was chosen to yield similar increases in airway pressure between animals and similarly to the vagal nerve stimulation (VNS)-induced increase in Ppi.

At least 3 repetitive cycles of alternating VNS followed 5 min later by intravenous acetylcholine were given to establish stable baseline responses of Ppi and heart rate. Subsequently, cumulative doses of muscle relaxants (each 0.15 ml) were administered intravenously, with each dose followed approximately 3 min later by a VNS and then 5 min later by an intravenous acetylcholine stimulus. Independent experiments were performed for each muscle relaxant in 6 animals. Cumulative doses of CW002 (0.03–0.6 mg/kg), gantacurium (0.075–1.5 mg/kg), or cisatracurium (0.025–0.5 mg/kg) were administered. Rapacuronium (8mg/kg) was given after the last dose of each muscle relaxant in every animal (about 10 times the ED95 for twitch suppression in humans). At the end of experiment, 0.5 mg/kg atropine was given to confirm that VNS-induced and intravenous acetylcholine-induced increase in Ppi and bradycardia were mediated via muscarinic receptors.

The effects of each dose of each muscle relaxant on airway and cardiac M2 muscarinic receptor function were assessed by augmentation of the magnitude of VNS-induced increases in Ppi and the inhibition of bradycardia, respectively. The effect of each dose of each muscle relaxant on postjunctional muscarinic receptors (i.e., M3 muscarinic receptors on airway smooth muscle) was assessed by the effect on the magnitude of intravenous acetylcholine-induced increases in Ppi. Any direct effect of each dose of each muscle relaxant on baseline airway tone was also assessed.

Data Analysis

All values are given as mean ± SEM. n represents the number of individual animals studied in vivo. Change in Ppi or heart rate after the addition of muscle relaxants were compared to the initial change in Ppi or heart rate induced by VNS or i.v. acetylcholine using two way analysis of variance with a post hoc Student t test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Instat software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) was used with statistical significance set at p< 0.05.

Results

Determination of ED95 for twitch suppression

The potency for neuromuscular blockade (ED95) for gantacurium, CW002, cisatracurium and rapacuronium in the guinea pig was 0.064 ± 0.006, 0.012 ± 0.0006, 0.10 ± 0.003 and 0.31 ± 0.05 mg/kg, respectively (Table 1). The potency ratio of each compound relative to rapacuronium and the dose ratio of the highest dose tested in the airway response study compared to the twitch response is also presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Muscle relaxant ED95 for twitch suppression and comparable potencies

|

Compound |

ED95 for twitch suppression |

Potency ratio of each compound to rapacuronium |

Highest dose used in airway study |

Dose ratio of highest dose used in airway study to ED95 for twitch suppression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/kg) | [ED95 of rapacuronium / ED95 of each compound] |

(mg/kg) | [Highest dose of airway study / ED95 of each compound] |

|

| CW002 | 0.012 ±0.0006 | 25.8 | 0.6 | 50.0 |

| Gantacurium | 0.064 ± 0.006 | 4.8 | 1.5 | 23.4 |

| Cisatracurium | 0.10 ± 0.003 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 5.0 |

| Rapacuronium | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 1.0 | 8 | 25.8 |

In vivo studies of muscle relaxant interaction with M2 or M3 muscarinic receptors

The effects of intravenously administered muscle relaxants (cumulatively increasing doses up to 50 X the ED95 for twitch suppression in guinea pigs) was assessed on pulmonary inflation pressures and heart rate in the absence or presence of VNS or intravenously administered acetylcholine. Baseline pulmonary inflation pressure was 8.76 ± 0.18 cm H2O before VNS and increased to 15.7 ± 0.62 cm H2O after VNS, with an average VNS-induced increase of 79.4 ± 6.4% in pulmonary inflation pressure. Baseline pulmonary inflation pressure was 8.91 ± 0.20 cm H2O before intravenous acetylcholine and increased to 16.5 ± 0.86 cm H2O after intravenous acetylcholine, with an average acetylcholine-induced increase of 85.2 ± 9.6% in pulmonary inflation pressure. There was no significant difference in baseline pulmonary inflation pressure or in the magnitude of the induced increase between VNS and intravenous acetylcholine.

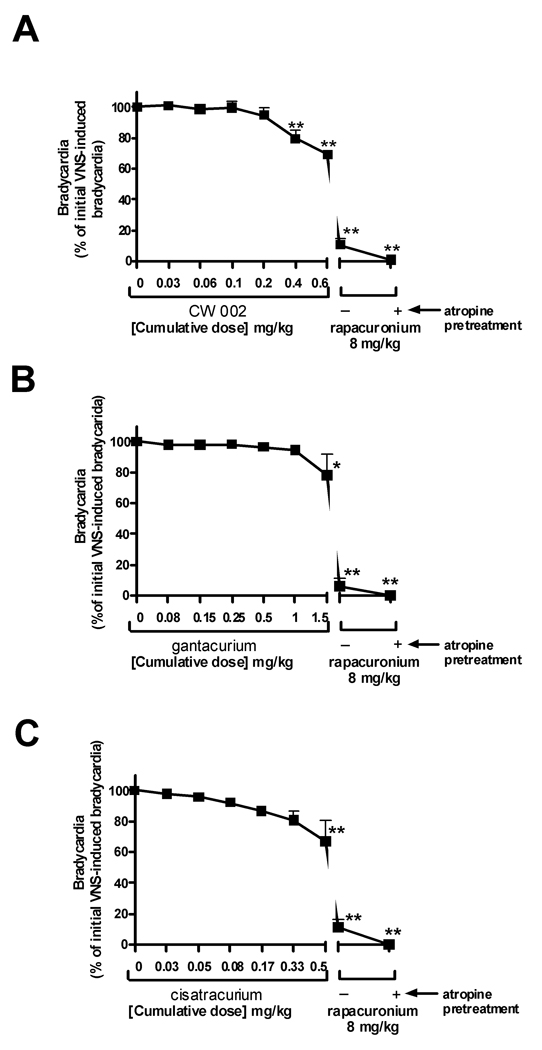

Acetylcholine released by VNS activates cardiac M2 muscarinic receptors inducing a transient bradycarida. The magnitude of the VNS-induced badycardia before the administration of muscle relaxants is defined as 100%. Antagonism of M2 muscarinic receptors by cumulatively increasing concentrations of muscle relaxants reduces this induced bradycardia by VNS and is expressed as the percent of initial bradycardia. Resting heart rate was 234.3 ± 9.2 bpm and transiently decreased by 81.5 ± 2.5% with vagal nerve stimulation.

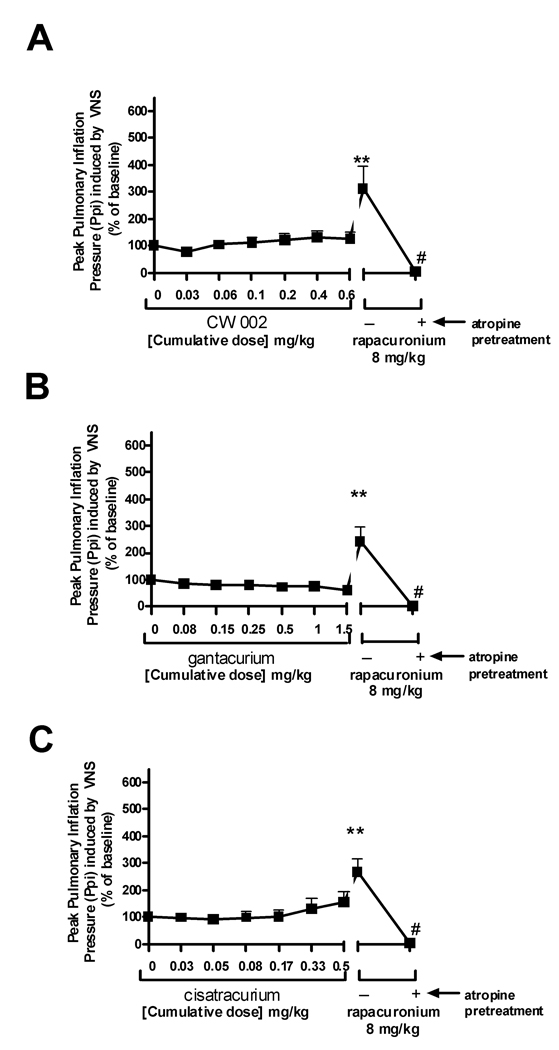

CW002 (0.03–0.6 mg/kg) (n=6) alone did not effect baseline pulmonary inflation pressure or heart rate (data not shown). CW002 had no significant effect on either VNS-induced (Fig 1) or intravenous acetylcholine-induced increases (Fig. 2) in pulmonary inflation pressure within and above clinically relevant concentrations. A high dose of CW002 (0.6 mg/kg) (50 X the ED95 for twitch suppression in guinea pigs) only slightly (20%) attenuated VNS-induced bradycardia (Fig 3).

Figure 1.

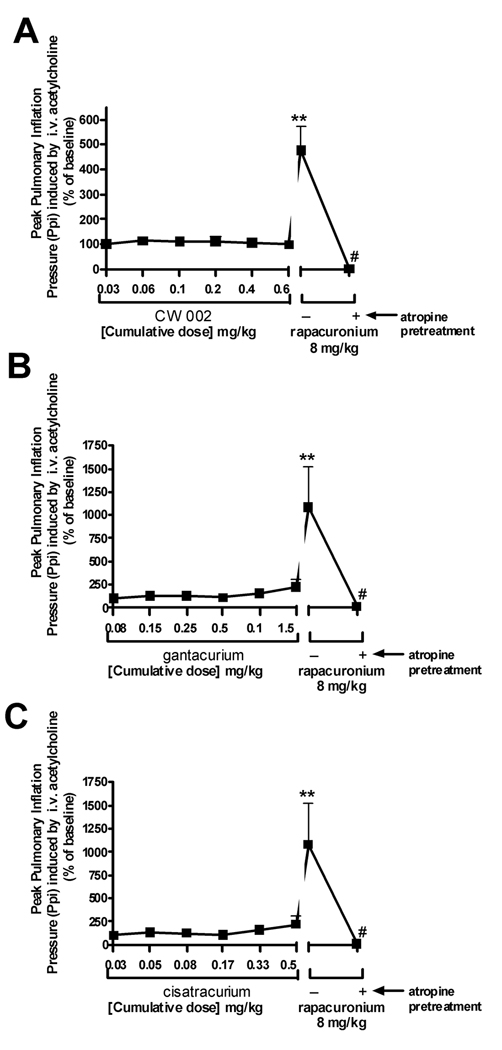

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Gantacurium (0.075–1.5 mg/kg) (n=6) alone did not affect baseline pulmonary inflation pressure or heart rate (data not shown). Gantacurium had no significant effect on either VNS-induced (Fig 1B) or intravenous acetylcholine-induced increases (Fig. 2B) in pulmonary inflation pressure within and above clinically relevant concentrations. A high dose of gantacurium (1.5 mg/kg) (23 X the ED95 for twitch suppression in guinea pigs) attenuated VNS-induced bradycardia (Fig 3B).

Cisatracurium (n=6) which shares some similarity in molecular structure to the new bisquaternary muscle relaxants and which has been shown previously to have no effect on airway muscarinic receptors6 was used as a negative control in the present studies. Cisatracurium (0.025–0.5 mg/kg) alone did not affect baseline pulmonary inflation pressure or heart rate (data not shown). Cisatracurium had no significant effect on either VNS- (Fig. 1C) or intravenous acetylcholine-induced (Fig. 2C) increases in pulmonary inflation pressures. Higher concentrations of cisatracurium dose-dependently attenuated VNS-induced bradycardia (Fig 3C). Cisatracurium administration alone had no effect on airway pressures.

Rapacuronium (n=18), which has been previously shown in this model to potentiate both VNS- and intravenous acetylcholine-induced increases in pulmonary inflation pressure5 was used as a positive control. Rapacuronium (8mg/kg) (26 X the ED95 for twitch suppression in guinea pigs), given after the last dose of each muscle relaxant in every animal, had no effect on baseline pulmonary inflation pressure but potentiated both VNS- (Fig 1) and intravenous acetylcholine-induced (Fig 2) increases in pulmonary inflation pressure and prevented VNS-induced bradycardia (Fig 3). Following a single dose of atropine (0.5 mg/kg) (n=18), rapacuronium-induced increases in pulmonary inflation pressure or bradycardia following VNS or intravenous acetylcholine were completely blocked confirming the muscarinic receptor mediation of these responses.

Discussion

The primary finding of this study is that gantacurium and CW002 at up to 23 and 50 times the ED95 of twitch suppression in guinea pigs, respectively, had no significant effect on either vagal nerve stimulated- or intravenous acetylcholine-induced increases in pulmonary inflation pressures in vivo in guinea pigs. In marked contrast, rapacuronium, a muscle relaxant previously shown in this model to have detrimental interactions with airway muscarinic receptors potentiated both nerve-and acetylcholine-induced increases in pulmonary inflation pressures in vivo. The ED95 for twitch suppression by gantacurium in the guinea pig (0.06 ± 0.006 mg/kg) is identical to that previously determined in monkeys20 and 3X more potent than that found in humans.18

Guinea pig airways and heart rate responses have been widely used models to characterize muscle relaxants interactions with M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors.3,5,17,21. Stimulation of parasympathetic nerves in the airway either by direct vagal nerve stimulation in vivo or by electrical field stimulation in vitro, releases acetylcholine that acts upon M3 muscarinic receptors on airway smooth muscle to cause smooth muscle contraction measured by an increase in pulmonary inflation pressure in vivo or direct smooth muscle contraction of an isolated airway ring in vitro. Typically the released acetylcholine acts upon inhibitory auto-feedback M2 muscarinic receptors on airway postganglionic parasympathetic nerves to inhibit further acetylcholine release21. In the heart the stimulation of vagal nerves in vivo releases acetylcholine to act upon cardiac M2 muscarinic receptors to induce bradycardia. Thus, measurements of pulmonary inflation pressure or heart rate in vivo during vagal nerve stimulation allows for the evaluation of M2 muscarinic receptor function. An antagonist or negative allosteric modulator at M2 muscarinic receptors (including some muscle relaxants)17 would block the airway parasympathetic nerve inhibitory M2 muscarinic receptor leading to enhanced acetylcholine release and increased smooth muscle contraction and would block parasympathetic nerve induced M2 muscarinic receptor-mediated bradycardia. This model also allows for the study of intravenously administered acetylcholine acting directly upon the airway smooth muscle M3 muscarinic receptor inducing airway contraction or the cardiac M2 muscarinic receptor inducing bradycardia.

These models of whole animal airway responses and isolated airway contractile responses combined with in vitro receptor pharmacology were instrumental in elucidating the detrimental effect of rapacuronium on airway smooth muscle constriction that led to its removal from clinical practice22,23. Although rapacuronium antagonized the M2 muscarinic receptor similar to other muscle relaxants6,17,24, its unique and central detrimental effect was its potentiation of the action of acetylcholine at airway smooth muscle M3 muscarinic receptors4,5. This allosteric potentiation by rapacuronium at the M3 muscarinic receptor was demonstrated in both isolated guinea pig airway rings in vitro4 and in intact whole guinea pig airways in vivo5 and this same in vivo model was therefore used in the present study for the evaluation of the new bisquaternary non-depolarizing muscle relaxants gantacurium and CW002 studied in parallel with rapacuronium.

In vivo, with doses of CW002 up to 50X the determined ED95 for twitch suppression in guinea pigs (0.6 mg/kg) there was no evidence of potentiation of vagal nerve induced increases in pulmonary inflation pressure. There was evidence of M2 muscarinic receptor antagonism of the M2 muscarinic receptors on the heart illustrated by the blockade of vagal nerve induced bradycardia, but this effect only occurred at doses which are likely to be supra-therapeutic (≥ 0.4 mg/kg). As demonstrated before5, rapacuronium (8 mg/kg; 26X the ED95 for twitch suppression in guinea pigs) caused a nearly 2-fold increase in pulmonary inflation pressures and complete blockade of bradycardia following vagal nerve stimulation in these same animals. These results suggest that in vivo attenuation of bradycardia may be a more sensitive indicator of M2 muscarinic receptor antagonism than potentiation of vagal nerve induced increases in pulmonary inflation pressure or that stimulating the vagus nerve activates other fiber subtypes to the airways (e.g. non-adrenergic, noncholinergic) in addition to parasympathetic cholinergic fibers. Nonetheless, the central result is that CW002 does not have significant effects on M2 muscarinic receptor function in vivo within clinically relevant doses.

Similarly, CW002, at clinically relevant concentrations, did not exhibit significant potentiation of acetylcholine effects at M3 muscarinic receptors in vivo. At concentrations up to 50X the determined ED95 for twitch suppression in guinea pigs, CW002 demonstrated no potentiation of i.v. acetylcholine induced increases in pulmonary inflation pressure indicating a lack of effect of CW002 at post-junctional M3 muscarinic receptors. As demonstrated before, rapacuronium caused a nearly 4-fold increase in pulmonary inflation pressures following i.v. acetylcholine in these same animals.

Only the highest in vivo dose of gantacurium tested (1.5 mg/kg = 23 X the ED95 for twitch suppression in guinea pigs) showed a small but significant blockade of vagal nerve induced bradycardia. Gantacurium demonstrated no interaction with M3 muscarinic receptors in vivo.

Cisatracurium served as a negative control in the current study due to the previous demonstration that it has no detrimental interactions with muscarinic receptors at clinically relevant concentrations. Interestingly, we were able to detect a small but significant attenuation of vagal nerve induced bradycardia at the highest dose tested (0.5 mg/kg = 5 X ED95 for twitch suppression in guinea pigs) suggestive of weak M2 muscarinic receptor antagonism at this high dose. There was no effect of cisatracurium on vagal nerve induced increases in pulmonary inflation pressures even at this extreme dose, again supporting that in this in vivo model, blockade of vagal nerve induced bradycardia is a more sensitive measure of M2 muscarinic receptor antagonism than is potentiation of vagal nerve induced bronchoconstriction. Our previous in vivo study demonstrated that 1.5 mg/kg rapacuronium which is 4.8X the ED95 for twitch suppression in guinea pig was sufficient for potentiating intravenous acetylcholine-induced bronchoconstriction.5 This suggests that the concentration of cisatracurium used in the present study (0.5 mg/kg or 5X the ED95 for twitch suppression) was sufficiently high to serve as an appropriate negative control in these studies.

Although both antagonism of the pre-junctional neural M2 muscarinic receptor and allosteric potentiation of acetylcholine at the post-junctional muscle M3 muscarinic receptor could theoretically both potentiate airway smooth muscle constriction, clinical experience with muscle relaxants would suggest that potentiation at the M3 muscarinic receptor is far more detrimental to airway tone4,5,23. Pancuronium and gallamine have long been known to be potent M2 muscarinic receptor antagonists17 yet clinical experience suggests that these muscle relaxants did not cause bronchoconstriction even when administered during periods of heightened parasympathetic nerve activity (e.g. intubation). This is likely due to pancuronium’s antagonism of post-junctional M3 muscarinic receptors and gallamine’s lack of significant affinity for the M3 muscarinic receptor7. Conversely, rapacuronium was found to potentiate acetylcholine’s action at M3 muscarinic receptor by a positive allosteric mechanism4. In the current study, neither CW002 nor gantacurium was found to have significant potentiation of acetylcholine action at post-junctional M3 muscarinic receptors in intact airways of the guinea pig.

In addition to interactions with muscarinic receptors, additional mechanisms exist by which muscle relaxants can potentiate bronchoconstriction including the release of histamine. The in vivo study of pulmonary inflation pressures is an ideal model to detect potential airway tone effects of histamine release3 and we have previously shown in this model that mivacurium-induced increases in pulmonary inflation pressure is blocked by the histamine receptor antagonist pyrilamine.5 The structural group to which CW002 and gantacurium belong has the tendency to release histamine. Gantacurium produced clinically relevant histamine release at 0.54 – 0.72 mg/kg (≈1–1.5X intubation dose) in humans18. Despite the increase in plasma histamine, there was no evidence of bronchoconstriction up to 50 times the ED95 for twitch suppression (3.2 mg/kg) in dogs19. In the current study, there was no effect on baseline pulmonary inflation pressure of the highest doses of CW002 (0.6 mg/kg) or gantacurium (1.5 mg/kg) (50 and 23X the ED95 for twitch suppression in guinea pigs, respectively) indicating that these drugs do not release amounts of histamine which might increase pulmonary inflation pressures in the guinea pig airway.

In summary, using a well defined in vivo guinea pig model previously used to define the mechanism of rapacuronium’s detrimental interaction with airway muscarinic receptors, we show that CW002 and gantacurium do not demonstrate interactions with airway M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors at concentrations up to 50X their ED95 concentrations for muscle relaxation.

Acknowledgments

Funding: National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, GM065281; intramural support from the Dept of Anesthesiology, Columbia University, New York, New York; The Nancy Paduano IRA and The CV Starr Foundation, Cornell University, New York, New York

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Summary Statement: The novel bisquaternary non-depolarizing muscle relaxants gantacurium or CW002 do not mimic rapacuronium’s potentiation of muscarinic receptor-mediated constriction of guinea pig airways in vivo.

References

- 1.Moss J, Rosow CE. Histamine release by narcotics and muscle relaxants in humans. Anesthesiology. 1983;59:330–339. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198310000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.North FC, Kettelkamp N, Hirshman CA. Comparison of cutaneous and in vitro histamine release by muscle relaxants. Anesthesiology. 1987;66:543–546. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198704000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okanlami OA, Fryer AD, Hirshman CA. Interaction of nondepolarizing muscle relaxants with m2 and m3 muscarinic receptors in guinea pig lung and heart. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:155–161. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199601000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jooste EH, Sharma A, Zhang Y, Emala CW. Rapacuronium augments acetylcholine-induced bronchoconstriction via positive allosteric interactions at the M3 muscarinic receptor. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1195–1203. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200512000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jooste E, Zhang Y, Emala CW. Neuromuscular blocking agents' differential bronchoconstrictive potential in Guinea pig airways. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:763–772. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264763.48920.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jooste E, Klafter F, Hirshman CA, Emala CW. A mechanism for rapacuronium-induced bronchospasm: M2 muscarinic receptor antagonism. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:906–911. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200304000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hou VY, Hirshman CA, Emala CW. Neuromuscular relaxants as antagonists for M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:744–750. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199803000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krombach J, Hunzelmann N, Koster F, Bischoff A, Hoffmann-Menzel H, Buzello W. Anaphylactoid reactions after cisatracurium administration in six patients. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2001;93:1257–1259. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200111000-00043. table. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laxenaire MC. Drugs and other agents involved in anaphylactic shock occurring during anaesthesia. A French multicenter epidemiological inquiry. Annales Francaises d Anesthesie et de Reanimation. 1993;12:91–96. doi: 10.1016/s0750-7658(05)81015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher MM, Baldo BA. The incidence and clinical features of anaphylactic reactions during anesthesia in Australia. Annales Francaises d Anesthesie et de Reanimation. 1993;12:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0750-7658(05)81016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alam M, Anrep GV, Barsoum GS, Talaat M, Wieninger E. Liberation of histamine from the skeletal muscle by curare. J.Physiol. 1939;95:148–158. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1939.sp003716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mongar JL, Whelan RF. Histamine release by adrenaline and D-tubocurarine in the human subject. J.Physiol. 1953;120:146–154. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1953.sp004881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naguib M, Samarkandi AH, Bakhamees HS, Magboul MA, el Bakry AK. Histamine-release haemodynamic changes produced by rocuronium, vecuronium, mivacurium, atracurium and tubocurarine. Br.J Anaesth. 1995;75:588–592. doi: 10.1093/bja/75.5.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleridge HM, Coleridge JC, Schultz HD. Afferent pathways involved in reflex regulation of airway smooth muscle. Pharmacol.Ther. 1989;42:1–63. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(89)90021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costello RW, Jacoby DB, Fryer AD. Pulmonary neuronal M2 muscarinic receptor function in asthma and animal models of hyperreactivity. Thorax. 1998;53:613–616. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.7.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fryer AD, Wills-Karp M. Dysfunction of M2-muscarinic receptors in pulmonary parasympathetic nerves after antigen challenge. J Appl.Physiol. 1991;71:2255–2261. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.6.2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fryer AD, Maclagan J. Pancuronium and gallamine are antagonists for pre- and post-junctional muscarinic receptors in the guinea pig lung. Naunyn- Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1987;335:367–371. doi: 10.1007/BF00165549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belmont MR, Lien CA, Tjan J, Bradley E, Stein B, Patel SS, Savarese JJ. Clinical pharmacology of GW280430A in humans. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:768–773. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200404000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heerdt PM, Kang R, The' A, Hashim M, Mook RJ, Jr, Savarese JJ. Cardiopulmonary effects of the novel neuromuscular blocking drug GW280430A (AV430A) in dogs. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:846–851. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200404000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savarese JJ, Belmont MR, Hashim MA, Mook RA, Jr, Boros EE, Samano V, Patel SS, Feldman PL, Schultz JA, McNulty M, Spitzer T, Cohn DL, Morgan P, Wastila WB. Preclinical pharmacology of GW280430A (AV430A) in the rhesus monkey and in the cat: A comparison with mivacurium. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:835–845. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200404000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fryer AD, Maclagan J. Muscarinic inhibitory receptors in pulmonary parasympathetic nerves in the guinea-pig. Br.J Pharmacol. 1984;83:973–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1984.tb16539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kron SS. Severe bronchospasm and desaturation in a child associated with rapacuronium. Anesthesiology. 2001;94:923–924. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200105000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meakin GH, Pronske EH, Lerman J, Orr R, Joffe D, Savaree AM, Lynn AM. Bronchospasm after rapacuronium in infants and children. Anesthesiology. 2001;94:926–927. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200105000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jooste E, Zhang Y, Emala CW. Rapacuronium preferentially antagonizes the function of M2 versus M3 muscarinic receptors in guinea pig airway smooth muscle. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:117–124. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200501000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]