Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) glycoprotein 42 (gp42) is a membrane protein essential for fusion and entry of EBV into host B-lymphocytes. Gp42 is a member of the protein fold family C-type lectin or lectin-like domains (CLECT or CTLD) and specifically is classified as a natural-killer receptor (NKR)- like CLECT. Literature review and phylogenetic comparison show that EBV gp42 shares a common structure with other NKR-like CLECTs and possibly with many viral CTLDs, but does not appear to exhibit some common binding characteristics of many CTLDs, such as features required for calcium binding. The flexible N-terminal region adjacent to the CTLD fold is important for binding to other EBV glycoproteins and for a cleavage site that is necessary for infection of host cells. From structural studies of gp42 unbound and bound to receptor and extensive mutational analysis, a general model of how gp42 triggers membrane fusion utilizing both the flexible N-terminal region and the CTLD domain has emerged.

Keywords: Epstein-Barr virus, glycoprotein, herpesvirus, EBV, gp42, viral entry

Introduction

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), taxonomically classified as Human herpesvirus 4, is a member of the γ-herpesvirus subfamily and one of eight human herpesviruses that establish latency in host cells. Prevalence of EBV is estimated at 90–95% in adult humans. EBV virus infects epithelial cells and B-lymphocytes in vivo, with lifelong latency established in B-cells [1]. While viral infection in childhood is typically benign, primary infection in adolescence or adulthood may lead to infectious mononucleosis. EBV is associated with lymphoid and epithelial cancers, including Burkitt’s lymphoma, Hodgkin’s disease, and nasopharyngeal and gastric malignancies [2–8]. In immunocompromised individuals, EBV is associated with diverse complications including immunoblastic lymphomas and oral hairy leukoplakia, an epithelial lesion [9–11].

The major cellular event in viral infection is the delivery of the viral capsid or nucleoprotein core into the host cell cytoplasm. Enveloped viruses such as the herpesviridae perform this delivery by fusion triggered by viral cell envelope glycoproteins binding to receptors on the host cell membrane. The EBV genome encodes several glycoproteins required for fusion and entry into host cells. Glycoprotein B (gB), gH and gL are necessary for fusion in both epithelial and B-cells [12–22], and glycoprotein 42 (gp42) is required for B-cell fusion but is inhibitory for epithelial fusion [23–26]. Gp350/220 serves as the first viral attachment glycoprotein for B-cells through binding to complement receptor type 2 (CD21) but is not required for entry [27]. Following this attachment, viral fusion is triggered by the binding of gp42 to human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II receptor [28–30]. When gp42 binds to this receptor, it blocks recognition of the complex by T-cell receptors [31], possibly helping the virus to escape immune system detection.

The solution of the structure of EBV gp42 bound to HLA-DR1 in 2002 [32] showed that the majority of EBV gp42 is a C-type-lectin-like domain (CTLD), part of the protein fold superfamily “CLECT: C-type lectin (CTL)/C-type lectin-like domain”. Specifically, it is in a subclass of CTLDs: “CLECT-NK-receptor like”, which are named for their resemblance to natural killer receptors. The N-terminal region of gp42 adjacent to the CTLD fold is responsible for the binding to the gH/gL complex to form a 1:1:1 ratio complex of the three proteins [23]. Disruption of the N-terminal region in gp42 results in disruption of fusion by hindering the binding of gp42 to gH/gL [25], and has led to the hypothesis that gH is a likely binding partner of gp42 in this interaction [33]. In fact, a peptide spanning the EBV gp42 region from amino acids 36–81 effectively binds gH with affinity comparable to that of the entire gp42 molecule [23]. The more recent solution of the structure of unbound EBV gp42 [34] illuminated subtle structural changes in the conformation of the protein that may provide insight into the behavior of this CTLD in binding ligands and in providing conformational triggers for fusion with host cells. This is a survey of the structural features of gp42, how they resemble or differ from typical CTLDs and how these structural features may play a role in fusion and viral entry into host B-cells.

Structural features of gp42 as a CTLD

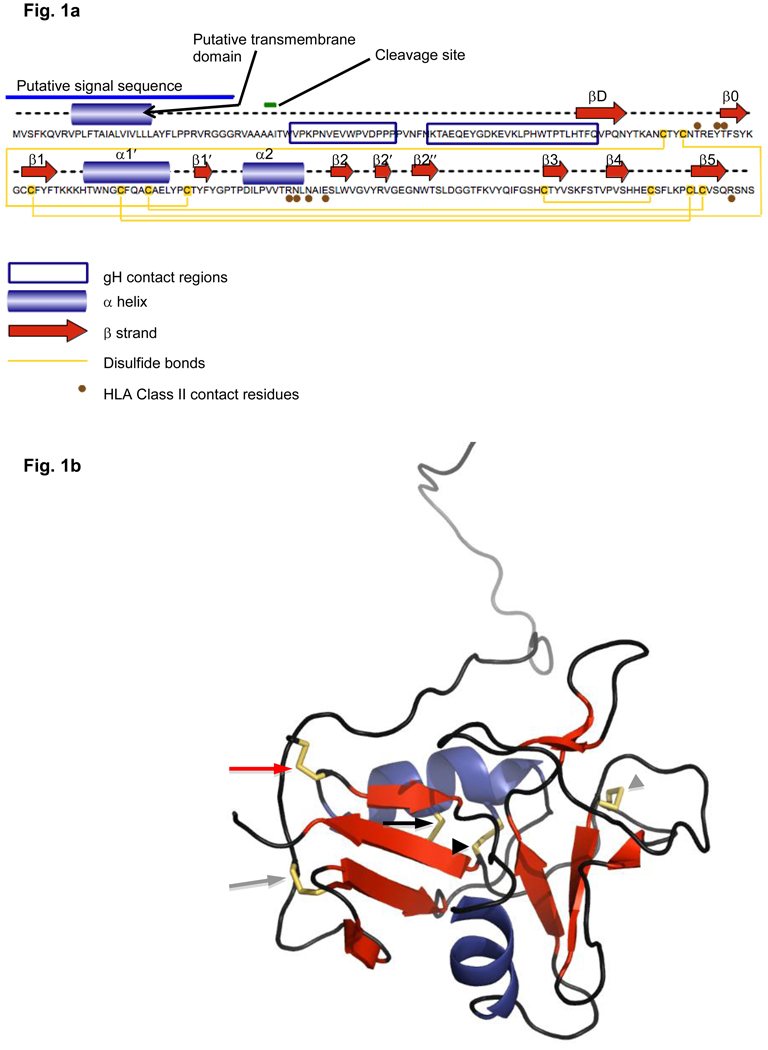

Gp42 is produced in two forms by EBV-infected B-cells: a full length form that is a 223 amino acid long type II transmembrane glycoprotein and a truncated soluble form (Figure 1A). The soluble form of gp42 is generated by the cleavage by host protease of the membrane bound form of gp42 at a protease site determined to be near amino acids 40–42 located adjacent to the N-terminal membrane spanning domain [35]. Both the soluble and membrane bound forms of gp42 bind gH/gL and HLA class II, but it is the soluble form of gp42 that functions in B cell fusion [23]. Interestingly, studies have shown that the soluble form of gp42 also inhibits HLA class II-bound antigen recognition by T-cell receptors suggesting a putative role of gp42 in immune evasion [35]. The long form of the protein gp42 fits the characteristics of a canonical C-type lectin-like domain [32], but its characteristic CTLD features, the alpha helices and beta strands, are somewhat shorter than those described in comparative reviews of the CTLD fold class [36–37]. It possesses two highly conserved disulfide bridges—sometimes called cysteine staples—present in canonical CTLDs. The first of these bridges connects the N and C terminal regions of the protein, tying together the ends of the entire structure (black arrowhead in Figure 1b). The second connects β3 and β5 in most long loop CTLDs [36], but falls just short of the β5 strand in gp42 (gray arrowhead). Two other disulfide bridges characteristic of other NK-like CLECTs are also seen in gp42. The first is typical of Ly49 NK CLECTs [38–39] and connects α1 to β5 (black arrow); the second is seen in CD94 and NKG2D CLECTs [40–42] and connects C102 with C115 in the β1 strand (gray arrow). Gp42 also contains an “extra” unique cysteine staple, serving to tack the N-terminal region to the side of the molecule nearest the HLA receptor [32, 34] (red arrow in Figure 1b).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1a Linear graphical representation of the sequence and structural features of EBV gp42

Fig. 1b Corresponding x-ray crystallization-determined structure of gp42 in its unbound form beginning with amino acid 33 (Protein DataBank identification number 3FD4). Blue coils=alpha helices; red arrows=beta strands; yellow tubeworms=disulfide bridges; black arrowhead=disulfide bridge conserved in all canonical c-type lectin-like domains (CTLDs); gray arrowhead=disulfide bridge conserved in long-loop CTLDs; black arrow=disulfide bridge conserved in Ly49 natural killer (NK) CTLDs; gray arrow=disulfide bridge conserved in CD94 and NK2GD CTLD families; red arrow=disulfide bridge unique to EBV gp42. Figure created with Pymol

A primary functional characteristic of many CTLDs is that they bind carbohydrates in a calcium-dependent manner. Two motifs interact with calcium to facilitate binding of sugar: the “WND motif” and the “EPN motif” [37]. The presence of these motifs has often been used as a predictor of carbohydrate binding. Gp42 possesses neither of these domains, so it is unlikely that it binds carbohydrate or utilizes calcium in binding its ligands [32].

The Long Loop Region (LLR)

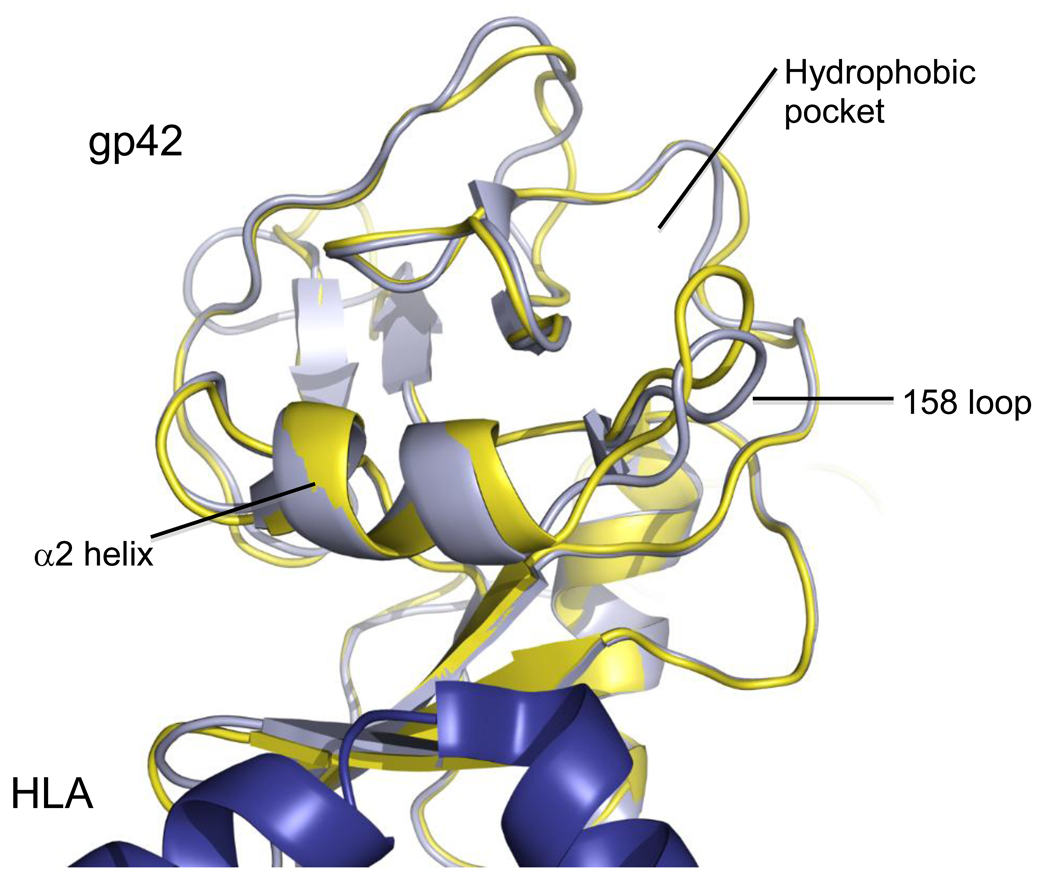

The long loop region is only observed in canonical CTLDs and is the most variable portion of the fold [37]. In CTLDs known to bind calcium, one of the calcium binding sites is located in this region. In most canonical CTLDs, specific binding sites are likely to be located in this region [36]. EBV gp42 is a canonical CTLD and possesses a LLR. Contained within this LLR is a putative canonical hydrophobic binding pocket, composed of 22 residues, 4 of which are supported by the α2 helix [32]. This pocket has been hypothesized to be involved in the initiation of membrane fusion since hydrophobic residues are typically not exposed on protein surfaces and surface hydrophobic patches are often identified as potential locations for protein-protein interactions [43]. The canonical binding pocket corresponds to the carbohydrate binding domain in CTLDs that bind carbohydrate [37]. In the heterodimeric CD94-NKG2 natural killer (NK) receptor family, this pocket is involved in binding the HLA-E receptor [44], and it binds MHC class I receptors in the Ly49 family of NK receptors [39]. In Ly49 proteins, the core of the binding site is largely conserved among all Ly49 members, while flanking regions differ among each Ly49 protein to confer specific recognition of the different MHC class I binding partners [45]. However, gp42 binds its receptor HLA protein in an entirely different portion of the CTLD, which corresponds to the homodimerization region in Ly49A and NKG2D [32, 45–46]. This leaves the canonical binding pocket open to accept another binding partner. In the unbound gp42 structure, the canonical binding pocket is more closed than in the HLA class II-bound structure [34]. Specifically, when gp42 binds to HLA class II, the alpha-2 helix shifts and the loop at residue 158 (“158 Loop”) moves towards the class II receptor, serving to widen the canonical binding pocket (Figure 2). The subtle opening of the pocket may act as a signal for fusion, since even small structural changes in proteins can create significant biological effects. The functional homologue of gp42 in herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) is glycoprotein D (gD). Structural change in gD upon binding to its receptor, HVEM, is thought to initiate recruitment of gH/gL and gB to the membrane fusion process [47]. A similar event caused by the binding of gp42 with class II may provide enough of a conformational change in the hydrophobic binding pocket and surrounding residues to initiate recruitment of cellular or viral proteins essential for membrane fusion [34], possibly EBV glycoprotein B (gB) or gH/gL.

Fig. 2.

Overlay of the HLA class II-bound and unbound structures of EBV gp42. Bound structure is light blue-gray, unbound is yellow, HLA class II is deep blue. Figure created with Pymol

Viral Orthologues to gp42

C-type lectins are among the oldest known animal lectins, with snake venom agglutinating lectin first described in the late 1800s and bovine conglutinin described in 1906 [48]. There are now more than one thousand identified animal CTLDs (some of which are inferred from genome sequences) with most of these proteins lacking lectin function, and thus best defined as “C-type lectin-like” by exhibiting characteristic CTLD fold structure and ligand binding features [37]. Non Metazoan CTLDs fall into two broad categories: parasitic bacterial & viral CTLDs and a group of CTLDs that contains non-viral plant proteins and the planktomycete Piruella bacterium [37]. Parasitic bacterial CTLDs exhibit the features of a compact form of the fold, while viral CTLDs appear to be of the canonical type, possessing a long-loop region. Many of these viral proteins show significant similarity to mammalian CTLD-containing proteins, suggesting evolutionary adaptations in which viruses hijacked or imitated host proteins to facilitate evasion of immune detection.

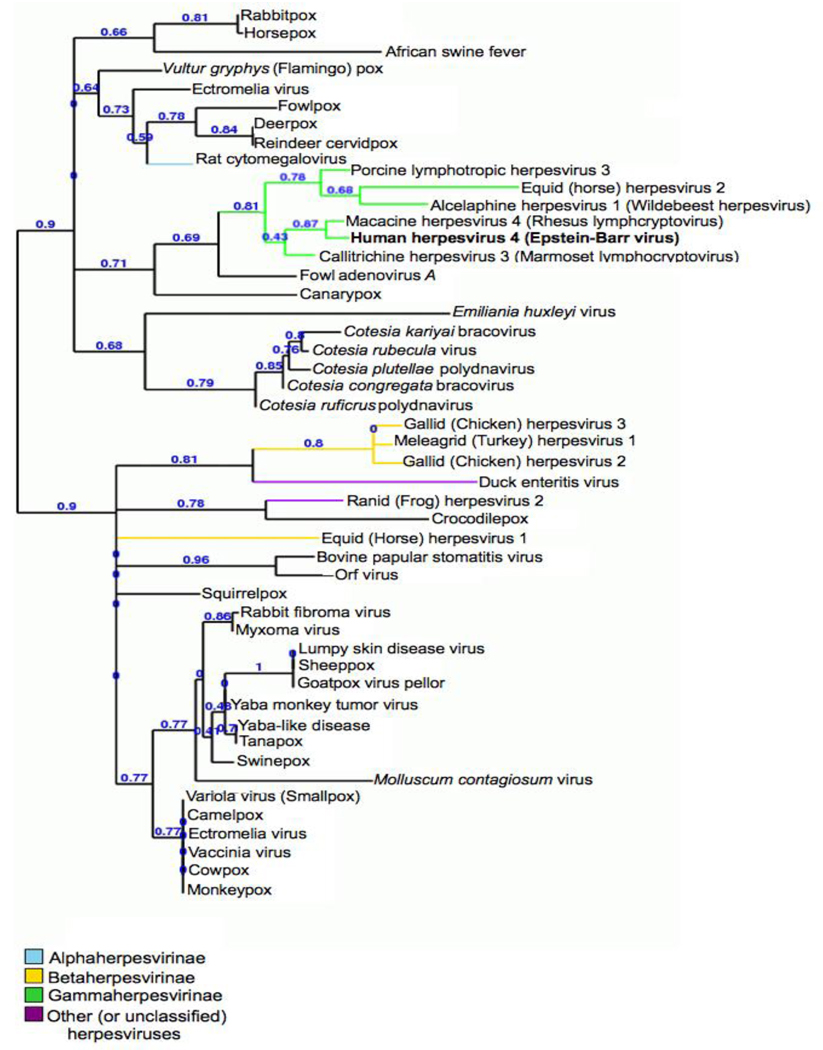

Sequence similarity searches for viral homologues to human EBV gp42 return very few orthologues in other species: notably rhesus and marmoset lymphocryptovirus gp42-type proteins. For a more thorough investigation of the phylogenetic diversity of viral CTLD-containing glycoproteins, it is useful to perform a Pattern Specific Iterated BLAST (PSI-BLAST). This is consistent with protocols used in characterizing the CTLD fold in comparative analysis studies [36]. The PSI-BLAST algorithm is similar to basic BLAST, but assigns a matrix of scores based on alignments of key patterns/motifs in the sequences in the protein database it searches [49–51]. This allows the investigator to uncover more remotely related homologues that may otherwise escape detection with BLAST, due to low overall sequence similarity scores. A PSI-BLAST was performed on proteins from only viral taxa using the BLOSSUM62 matrix on NCBI’s BLAST server at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/Blast.cgi. After 20 iterations, no novel sequences were found. The sequences returned by the search were culled to one representative sequence per viral species using reference sequences where available. These sequences were verified using the annotations in the InterPro database of viral CTLD containing proteins at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/IEntry?ac=IPR016186. The InterPro family of C-type lectin-like proteins (family accession identifier IPR016186) contained 136 viral entries at the time it was consulted, though a number of these sequences are redundant. One sequence per virus for a total of 51 species was uploaded in FASTA format to the Phylogeny.fr server, where all subsequent steps were performed [52]. Sequences were aligned in a multiple alignment using ProbCons [53], and edited manually to improve the alignment. These results then were submitted to phylogenetic analysis using PHYML [54], and trees were visualized with TreeDyn [55]. After initial tree construction, extreme outlying sequences were removed from the alignment in order to present a more compact phylogram, including sequences from two Oryza (rice) species, bluetongue virus and ovine herpesvirus 2. These sequences aligned with gp42 for only short spans with low sequence similarity and identity. Results are depicted in Figure 3. It is not surprising that proteins from two known primate lymphocryptoviruses, rhesus (88% sequence similarity to gp42, 79% identity) and marmoset (56% similar, 39% identical), are most closely related to EBV gp42. Sequencing of several non-human primate lymphocryptoviruses (LCVs) has resulted more than 50 known primate LCVs and detailed phylogenetic analysis of these sequences suggests it is possible that orthologous proteins exist in several other primate gammaherpesvirus species in addition to marmoset and rhesus, representing species from Old World and New World primates and other hominoids [56–58]. Some of the next nearest neighbors in the phylogram are other mammalian gammaherpesvirus proteins.

Fig. 3.

Rooted phylogenetic cladogram of viral CTLDs. Gamma herpesvirus CTLDs are grouped (green branch). Tree visualized with TreeDyn

The results of this analysis prompted further investigation of other viral CTLDs’ function and structural characteristics. No crystallography or NMR-solved structures exist for other viral CTLDs except for major tropism determinant (Mtd), a retroelement-encoded receptor-binding protein of Bordetella bacteriophage. This protein lacks disulfide bridges and was not detected during the PSI-BLAST performed above, but it has been cited as an example of the fact that CTLDs can tolerate massive sequence variation yet still maintain structural stability [59]. Many viral C-type lectin-like containing proteins are identified as CTLD structures solely by prediction from genomic sequence data. Interestingly, one of the sequences removed from the alignment to generate a more compact phylogram belonged to Ov7 protein from ovine herpesvirus, a γ-herpesvirus (30% similar, 9% identical to gp42). Despite belonging to the same viral family as EBV, the protein from ovine herpesvirus does not exhibit the typical disulfide bond locations that characterize many CTLDs. In fact, this protein aligned to the N-terminal region of gp42, not the canonical CTLD region, is most similar to the Alcelaphine (wildebeest) herpesvirus protein A7 (38% similar, 20% identical to gp42), but does not exhibit many characteristics of a CTLD itself. Little is known about this protein, which has not been experimentally investigated. Phylogenetic studies of gammaherpesvirinae in such diverse species as hyena, rhinocerous, zebras and crocodiles (among many others) has made the gammaherpesvirus family the most extensively characterized among the three subfamilies (alpha, beta and gammaherpesvirinae), but also the most complex [60–61]. This complexity makes coevolutionary interpretation difficult and may help to explain why such proteins as Ov7 differ greatly from EBV gp42 while still belonging to the same viral subfamily.

Information from experimental studies of viral gp42 orthologues’ similar function and overall structure despite sequence differences is valuable for understanding function of this protein class. Rat cytomegalovirus (RCMV) CTLD protein (21% similar, 14% identical to gp42) was the first of this fold class identified in a herpesvirus, and it shows marked similarity to CD69 NK receptors [62]. RCMV is a β-herpesvirus, and the CTLD coded by its genome is a spliced gene with introns and exons—making it different from the unspliced gp42 protein-coding gene BZLF2. Despite these differences, it is proposed that RCMV C-type lectin-like protein plays a role in immune system evasion by the virus by downregulating MHC class I [63]. Rat CMV lectin-like protein lacks the disulfide bridge between β3 and β5 that is present in EBV gp42 and most other long-loop CTLDs and shares this lack with cowpox (27% similar, 16% identical to gp42) and deerpox (31% similar/20% identical) virus orthologues. Canarypox viral CTLD (30% similar, 19% identical) possesses four disulfide bridge features that are shared by gp42 with other canonical CTLDs and is thus groups more closely to gp42 by sequence similarity. African swine fever virus (ASFV) possesses a CTLD-containing protein (27% similar, 16% identical) that is encoded both early and late in the infection process. This protein has been shown to be non-essential for viral growth in porcine macrophages or for virulence in domestic swine [64], but to inhibit p53 activity and apoptosis during ASFV infection [65]. Porcine lymphotropic virus CTLD-containing protein (52% similar/35% identical) comes from the γ-herpesvirus porcine lymphotropic herpesvirus 1 (PLHV-1), a homologue to EBV [66–67]. This virus has been shown to upregulate EBV promoters and to trigger reactivation of the virus in BC-3 cells latently infected with EBV, prompting cause for concern when using porcine xenografts in human transplantation [68]. While no direct comparisons between EBV gp42 and the porcine lymphotropic herpesvirus CTLD have been made, strong similarity of sequence exists between these proteins, with PLHV-1 CTLD the closest non-primate sequence recovered in the PSI-BLAST results.

CTLD Structural Neighbors of gp42

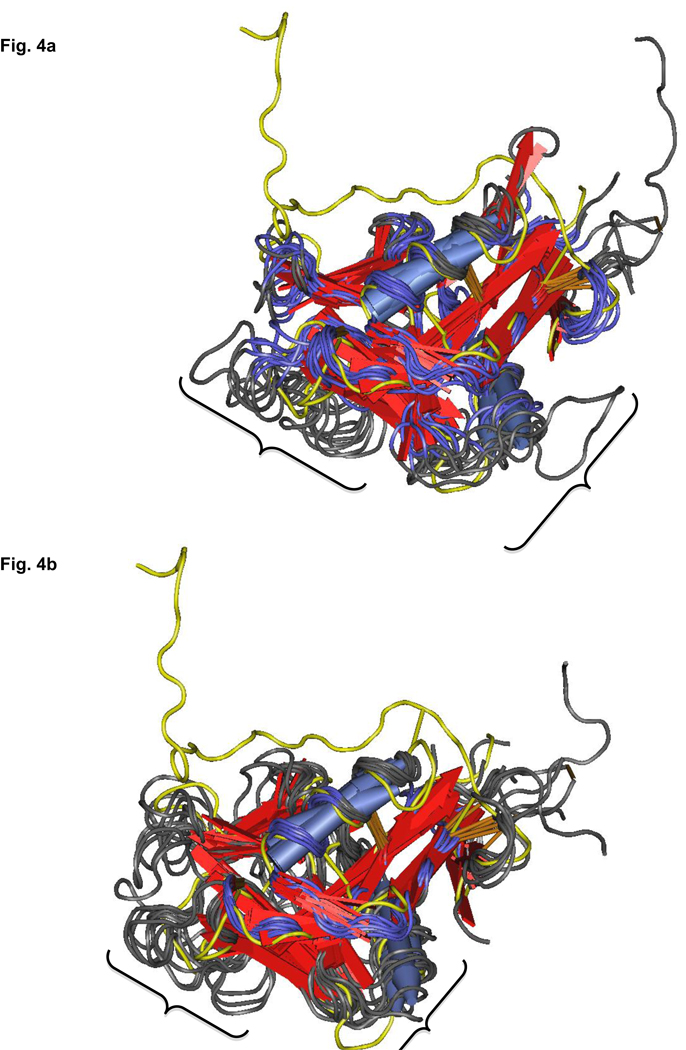

CTLDs show a remarkable structural similarity while showing as little as 20% sequence similarity [37]. For this reason, sequence similarity searches may not always elucidate the potential of this family. The CTLD is a strongly conserved fold with a long evolutionary history. The carbohydrate binding function is thought to be the oldest function of the family. Given its long history, it is not surprising that the fold family has become more varied and functionally flexible over time and species to bind other ligands besides carbohydrate while still maintaining the same overall structure. Fish antifreeze CTLDs bind ice crystals [69], pancreatic lithostathine binds CaCO3 [70] and many CTLDs bind proteins [37]. Since sequence similarity searches may not uncover EBV gp42’s nearest functional relatives, alignments based on structural similarity using the Vector Alignment Search Tool (VAST) from NCBI’s MMDB Entrez Structure database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=structure) were performed to reveal the 9 best structural neighbors to gp42, scored and ranked by number of residues aligned (Figure 4a and Table 1). EBV gp42 is very similar to NK cell-activating receptors such as CD94, but when evaluated solely by number of aligned residues by structural feature, the EBV protein also aligns with such diverse CTLDs as rat surfactant protein, mouse scavenger receptor, human lithostathine and low density lipoprotein receptors, fish antifreeze protein and chicken eggshell ovocleidin.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4a Nearest structural neighbors of EBV gp42 as determined by number of residues aligned with VAST. EBV gp42 is highlighted in yellow. Areas demarcated by brackets show less-aligned loops. Blue=alpha helices; red arrows=beta strands. Structures visualized with Cn3D

Fig. 4b Re-alignment of nearest structural neighbors using the Loop-Hausdorff method with VAST. Loops are now more compactly aligned. Colors as in Fig. 4a. Structures visualized with Cn3D

Table 1. Structural Neighbors of gp42.

Listing of best structural alignments to gp42 from the Molecular Modeling Database (MMDB). Left side shows 9 structures with greatest number of aligned residues. Right side shows 9 structures with best structural alignment using Loop Hausdorff Metric (LHM)

| 9 Best Structural Orthologues Based on Numbers of Aligned Residues |

9 Best Structural Orthologues Based on Loop Hausdorff Metric |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB ID# |

Aligned Length |

RMSD | % Sequence Identity |

LHM | Description | PDB ID# |

Aligned Length |

RMSD | % Sequence Identity |

LHM | Description |

| 1GZ2 A |

108 | 2.6 | 17.6 | 4.9 | Ovocleidin-17 Protein of Gallus Gallus Eggshell Calcified Layer |

3CDG F1 |

46 | 1.6 | 21.7 | 1.3 | Human Cd94NKG2A in Complex with HLA-E |

| 1WMZ A |

108 | 2.7 | 13 | 3.8 | C-Type Lectin Cel-I Complexed With N- Acetyl- D- Galactosamine |

1HQ8 A1 |

47 | 1.5 | 23.4 | 2.5 | Murine Nk Cell- Activating Receptor Nkg2d At 1.95 A |

| 3CDG E |

107 | 2.5 | 13.1 | 3 | Human Cd94NKG2A Complexed with HLA-E |

3CCK B |

96 | 1.9 | 20.8 | 2.5 | Human Cd69 |

| 2C6U A |

107 | 2.2 | 17.8 | 3.5 | Human Clec-2 (Clec1b) |

3FF9 B |

95 | 2.1 | 16.8 | 2.6 | Nk Cell Receptor Klrg1 |

| 2OX9 C |

106 | 2.2 | 17.9 | 3.3 | Mouse Scavenger Receptor C- Type Lectin Carbohydrate- Recognition Domain |

3FF7 C |

100 | 1.9 | 18 | 2.7 | Nk Cell Receptor Klrg1 Bound to E- Cadherin |

| 1JZN A |

103 | 2.3 | 14.6 | 3.4 | Galactose- Specific C-Type Lectin |

2RIC C1 |

97 | 2.4 | 12.4 | 2.8 | Human Surfactant Protein D With L-Glycero-D- Manno- Heptopyranosyl- (1–3)-L- Glycero- D-Manno- Heptopyranose |

| 3CAD B |

101 | 2.3 | 23.8 | 4.1 | Natural Killer Cell Receptor, Ly49g |

1R13 A | 97 | 2.3 | 12.4 | 2.8 | Carbohydrate Recognition And Neck Domains Of Surfactant Protein A (Sp-A) |

| 1R13 A1 |

100 | 2.5 | 12 | 2.9 | Carbohydrate Recognition And Neck Domains Of Surfactant Protein A (Sp-A) |

2IT5 A | 95 | 2.1 | 22.1 | 2.9 | Dcsign-Crd With Man6 |

| 3BC7 A |

100 | 2.2 | 18 | 3 | Carbohydrate Recognition Domain Of Langerin |

3BC7 A |

100 | 2.2 | 18 | 3 | Carbohydrate Recognition Domain Of Langerin |

Using the aligned length alone to compare protein similarity is the default alignment choice with VAST, and structural alignment by RMSD (root mean squared deviation) is a standard practice, but the Loop Hausdorff Metric (LHM) is a more accurate depiction of structural similarity [71]. LHM measures similarity of loops after alignment of major secondary structural elements. This type of alignment is especially relevant when comparing CTLDs that possess long-loop regions which are essential for the protein’s function or binding. LHM values were used to re-rank all structural homologues retrieved by the VAST search of the MMDB, and to create a new structural alignment based on loop similarity to EBV gp42 (Figure 4b). The best-ranked 9 proteins in this alignment are now mostly NK-receptor-like CTLDs, and thus have very similar loop characteristics, despite having very low sequence identity. Table 1 shows a summary of the best structural orthologues ranked by numbers of aligned residues and by LHM. The areas demarcated by brackets in Figures 4a and b show that the aligned loop regions are now more compact. In the LHM model, the best-matched structure with EBV gp42 is human natural killer receptor CD94NKG2A complexed with HLA-E that only shares 22% amino acid identity. These alignments emphasize that, when evaluating a fold as common as the CTLD, it is important to consider structural similarity when attempting to deduce functional characteristics of the protein.

The N-terminal Region of EBV gp42

The region of gp42 that is critical for interaction between gp42 and EBV gH/gL is the N-terminal region, specifically residues 36–81. Studies have proposed that this region interacts with gH/gL by contact through amino acids 47–61 and 67–81 with high molecular affinity in a hairpin-like conformation [72]. The structures of gp42 bound to class II and unbound gp42 begin with amino acid 33 but most of the gH/gL interactive region [34] is flexible and disordered in both the bound and native structures of gp42, and this flexibility may be beneficial in creating regions of contact with gH/gL.

In separate studies of deletions of portions of the N-terminal region, it was found that the cleavage site that results in the soluble form of gp42 is separate from the gH/gL interactive site [73] and the resultant soluble form of the protein binds B cells with greater affinity than the full-length protein. It is this soluble form that functions in B-cell fusion [23].

The N-terminal region of EBV gp42 showed little to no sequence identity with other viral CTLDs in the PSI-BLAST described above. Neither does it have strong sequence similarity with other non-viral CTLDs identified by the structural VAST search. However, investigation of these orthologous proteins’ N-terminal domains may uncover some similar characteristics shared by this region of gp42 with other lectin-like proteins. Lithostathine, pancreatitis associated protein (PAP) and other members of a multifunctional CTLD family exhibit a protease cleavage site located between arginine and isoleucine residues in the short N-terminal domain that, like gp42, produces a soluble short form of the protein [74–75]. These proteins have a great variety of functional roles depending on their location in cells, so similarity of cleavage site and CTLD fold structure do not ensure similar biological function. This diversity of function in a single fold class is another characteristic of the long evolutionary persistence of the fold [37]. Chinese white shrimp [76] and Zhikong scallop [77] possess an N-terminal signal sequence paired with a C-type lectin-like fold in proteins that, in both species, serve as pattern recognition receptors that are upregulated in immune response to invasion by bacterial pathogens. Other CTLDs with roles in cytotoxicity such as CD69 [78], NKG2D and NKp80 [79] and the Ly49 family share gp42’s type II transmembrane features in their N-terminal regions. Similarity to native immune response protein folds in diverse species raises the possibility that EBV gp42 evolved by the virus hijacking or mimicking a CTLD fold host protein in order to evade immune system detection.

In studies of EBV gH/gL chimeric complexes comprised of various combinations of human, marmoset and rhesus gH and gL proteins matched with human gp42, gp42 fails to function in fusion assays with marmoset gH (MgH) while it does function with rhesus gH (RhgH) [25, 80]. It could be possible that EBV gp42’s N-terminal region is not well-fitted for interaction with MgH and thus does not function in fusion with B cells, so the fault may lie in the human EBV gp42 and not MgH. Marmoset gp42 homologue CalHV3gp47-ORF 44 is more similar to gp42 in its CTLD region than in its N-terminal span. Additionally, the N-terminal region is at least 20 residues longer in marmoset than in EBV gp42 in the current data entry in EntrezProtein at NCBI. This may mean that the marmoset protein adopts a different conformational shape in its N-terminal region and this shape is possibly dissimilar enough to human gp42 that they are not interchangeable for fusion function. To evaluate the extent of dissimilarity between human and marmoset gp42 orthologues, the human, rhesus and marmoset gp42-like proteins were aligned in a multiple alignment, using the RefSeq sequences for each protein from EntrezProtein at NCBI. This alignment brings to light a possible error in the annotation of marmoset gp42. The marmoset protein sequence is the result of automated gene-finding algorithms and places the start codon for CalHV3gp47-ORF44 60 bases farther upstream than either the human or rhesus orthologue. The gene has three possible methionine-coding ATG start sites early in its sequence. When the three sequences are realigned, using an ATG start codon 61 bases into the marmoset DNA sequence, the resulting translated protein is nearly the same length as the human and rhesus orthologues and, more importantly, places the CTLD in the same location of the protein. This possible error in annotation of CalHV3gp47 does not fully explain the failure of human EBV gp42 to function in fusion assays with marmoset gH. It does raise the possibility that the open reading frames for the marmoset virus genome for this gene and perhaps others—such as marmoset virus gH—are incorrectly predicted. Alternatively, sequence differences between EBV gp42 and the marmoset orthologue may explain the lack of interchangeable function. This doubt can only be extinguished by more extensive laboratory experimentation on marmoset HV3 gp47 or on human-marmoset viral chimeras.

Mutational Studies of gp42 and HLA Class II

Several mutational assays of gp42 and/or HLA class II have been published [25, 72–73, 81–82]. Table 2 summarizes three studies of mutations to gp42 and their results in fusion assays and Figure 5 illustrates the locations on gp42 of some mutation sites. In addition to those shown in the table, early truncation mutants of gp42 revealed that deletion of up to 90 residues from the N-terminal end of gp42 can still produce a protein that is capable of binding HLA class II, while deletion of as few as 28 residues from the C-terminal tail rendered gp42 incapable of binding HLA class II, presumably because of disruption of the CTLD fold conformation [82]. Mutations to HLA class II confirmed that gp42 does not bind class II at the canonical hydrophobic pocket, distinguishing its interactions with class II from the canonical CTLD docking pattern exhibited by Ly49A with MHC class I [81].

Table 2. Mutational Studies of gp42.

Summary of effects of mutation on gp42 from three published studies. Symbols used: Plus sign (+) = functional in fusion assays; minus (−) = non-functional in fusion assays; plus/minus (+/−) = reduced function in fusion assays; Δ = deletion of residues following the symbol; ND = assay not done.

| Mutant | Functional Domain | Expressed at surface? | Fusion | Binding | Binding Partner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1a | LI12 | TM | Yes | + | + | HLA |

| LI27 | N-terminus | Yes | + | + | HLA | |

| LI82 | N-terminus | Yes | + | + | HLA | |

| LI93 | N-terminus | Yes | + | + | HLA | |

| W44A | N-terminus | Yes | + | + | HLA | |

| Q89A | N-terminus | Yes | + | + | HLA | |

| T104A | Class II | Yes | + | + | HLA | |

| R154A | Class II | Yes | + | + | HLA | |

| Y185F | Yes | + | + | HLA | ||

| LI118 | Structural | Yes | − | − | HLA | |

| LI122 | Structural | Yes | − | − | HLA | |

| LI134 | Structural | Yes | +/− | +/− | HLA | |

| LI179 | Structural | Yes | − | − | HLA | |

| LI195 | Yes | − | − | HLA | ||

| LI216 | Structural | Yes | − | − | HLA | |

| W125G | Structural | Yes | − | − | HLA | |

| LI104 | Class II | Yes | − | − | HLA | |

| LI112 | Class II | Yes | − | − | HLA | |

| LI148 | Class II | Yes | − | − | HLA | |

| LI149 | Class II | Yes | − | − | HLA | |

| Y107A | Class II | Yes | − | − | HLA | |

| E160A | Class II | Yes | − | − | HLA | |

| R220A | Class II | Yes | +/− | − | HLA | |

| LI193 | Yes | − | + | HLA | ||

| LI206 | Yes | − | + | HLA | ||

| LI210 | Yes | +/− | + | HLA | ||

| F210A | Yes | − | + | HLA | ||

| Study 2b | R30A | N-terminus | Yes | + | + | gH/gL |

| R32A | N-terminus | Yes | + | + | gH/gL | |

| R36A | N-terminus | Yes | + | + | gH/gL | |

| W44A | N-terminus | Yes | + | + | gH/gL | |

| K47A | N-terminus | Yes | + | + | gH/gL | |

| K47A/P48S | N-terminus | Yes | + | + | gH/gL | |

| E51A | N-terminus | Yes | + | + | gH/gL | |

| Δ32–36 | N-terminus | Yes | + | + | gH/gL | |

| Δ57–61 | N-terminus | Yes | + | − | gH/gL | |

| Δ62–66 | N-terminus | Yes | + | + | gH/gL | |

| Δ37–41 | N-terminus, cleavage | Yes | − | + | gH/gL | |

| Δ42–46 | N-terminus | Yes | − | + | gH/gL | |

| Δ82–86 | N-terminus | Yes | − | + | gH/gL | |

| Δ87–91 | N-terminus | Yes | − | + | gH/gL | |

| Δ92–96 | N-terminus | Yes | − | + | gH/gL | |

| Δ47–51 | N-terminus | Yes | − | +/− | gH/gL | |

| Δ52–56 | N-terminus | Yes | − | − | gH/gL | |

| Δ67–71 | N-terminus | Yes | +/− | − | gH/gL | |

| Δ72–76 | N-terminus | Yes | − | − | gh/gL | |

| Δ77–81 | N-terminus | Yes | − | +/− | gH/gL | |

| Δ45–89 | N-terminus | Yes | − | − | gH/gL | |

| Δ37–41/Δ67–71 | N-terminus | Yes | − | − | gH/gL | |

| Δ42–46/Δ72–76 | N-terminus | Yes | − | − | gH/gL | |

| Δ77–81/Δ47–51 | N-terminus | Yes | − | − | gH/gL | |

| Study 3c | ΔN36 | N-terminus | No; +gH/gL Yes | + | +, + | HLA, gH/gL |

| ΔN41 | N-terminus | No; +gH/gL Yes | + | +, + | HLA, gH/gL | |

| ΔN46 | N-terminus | No; +gH/gL Yes | + | +, + | HLA, gH/gL | |

| ΔN51 | N-terminus | No; +gH/gL No | − | +, − | HLA, gH/gL | |

| VAAAA37–41DDDDK | N-terminus, cleavage | ND | +/− | ND | ||

A.L. Silva, J. Omerovic, T.S. Jardetzky, R. Longnecker, J Virol 78, 5946–5956, (2004);

A.N. Kirschner, A.S. Lowrey, R. Longnecker, T.S. Jardetzky, J Virol 81, 9216–9229, (2007);

J. Sorem, T.S. Jardetzky, R. Longnecker, J Virol 83, 6664–6672, (2009)

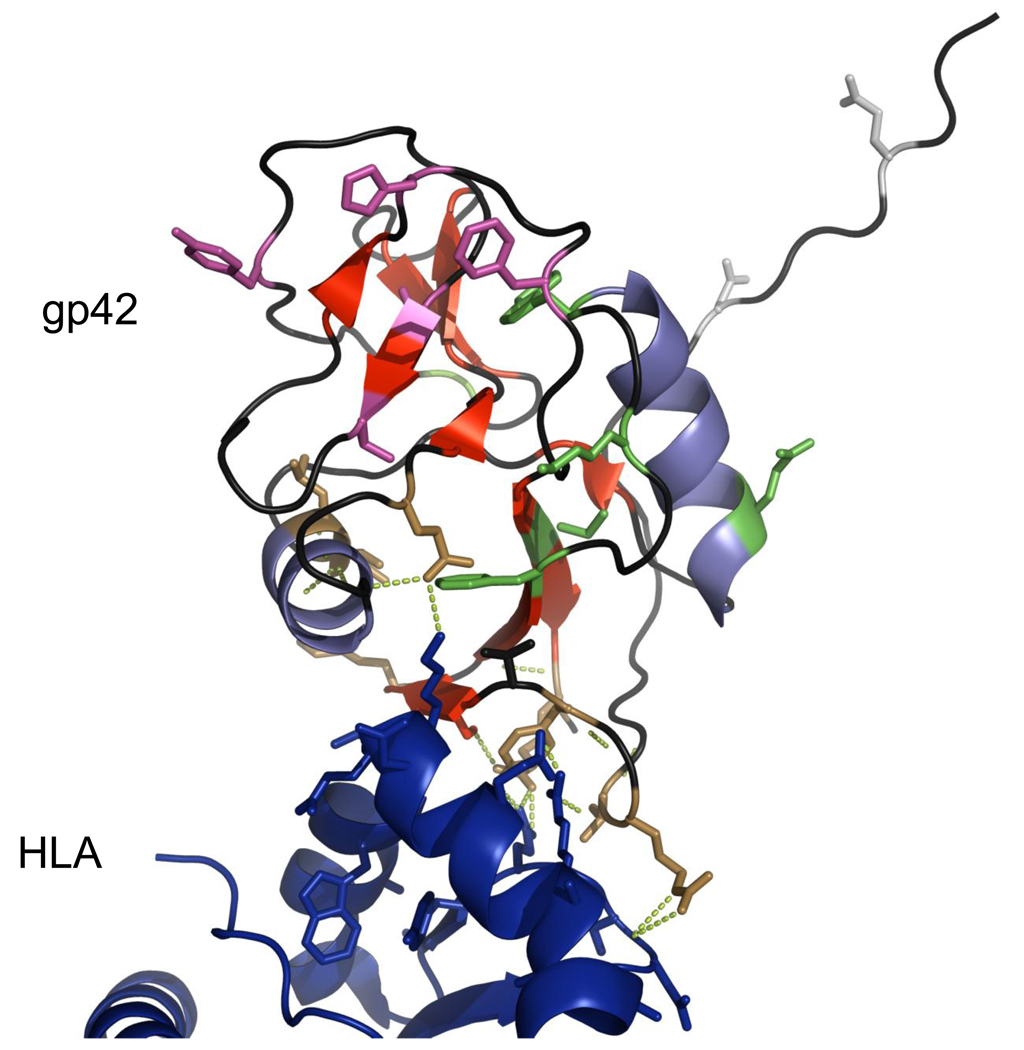

Fig. 5.

Structure of EBVgp42 bound to HLA class II (PDB identification number 1KG0) with residues selected for mutation highlighted in color. Amino acids in the N-terminal domain are shown in silver-gray; HLA class II contacting residues are brown; hydrophobic pocket residues are pink-purple; residues in other structural features are green. Hydrogen bonds between selected gp42 and HLA contact residues are shown by chartreuse dotted lines. Structure visualized with Pymol

The first study of mutations to gp42 in Table 2 confirms the importance of residues that bind HLA class II in fusion function: LI104, LI112, LI148, LI149, Y107A and E160A were non-functional in fusion while R220A exhibited reduced fusion capability. Class II contact mutants T104A and R154A did not affect fusion. The T104 mutation does not disrupt hydrogen bonds with class II residue Rβ72, while mutation of gp42 Y107A likely does disrupt hydrogen bonds with the same residue [25]. R154’s binding partner in class II is Sβ63, which has been shown to not be essential in the interaction [81]. Of greater importance in this group of mutations is the set of mutants that affect the hydrophobic binding pocket without disrupting binding with HLA class II. These mutants failed to function in fusion, providing further evidence that this pocket is a potential docking site for another protein necessary for fusion [25]. The ligand for this pocket has yet to be defined. This study also identified mutants that apparently disrupt core structural features of gp42 that are distinct from the HLA class II binding site or the hydrophobic pocket.

Mutations to the N-terminal domain shown in the second section of Table 2 fall into three categories: mutants that retain both fusion and gH/gL binding capabilities, mutants that lose fusion capability but retain gH/gL binding and mutants that lose both fusion and gH/gL binding abilities. The mutants in the third category revealed that residues 37 to 56 and 72 to 96 are essential for fusion, and the amino acids 47–61 and 67–81 are responsible for binding to gH. Based on this finding a peptide spanning amino acids from 36–81 was constructed and shown to bind to gH/gL with high affinity, inhibiting B cell fusion when competing with soluble gp42 [72]. Some mutants in the second category of this study (Δ82–86, Δ87–91 and Δ92–96) may disrupt a potential dimerization region that was modeled in the structure of gp42 bound to HLA class II [32]. One mutant, Δ37–41, eliminates most of the cleavage site that is predicted to reside at residues 40–42, which is responsible for the production of soluble gp42 [72].

Soluble gp42 plays an important role in membrane fusion [35]. The third set of mutations depicted in Table 2 was constructed to investigate the cleavage site and secretion of soluble gp42. Truncation mutant Δ51 was not functional in fusion assays and did not bind gH/gL. This is not surprising, based on studies mentioned above that implicate residues 37–56 in gH/gL binding. Truncation mutants Δ36, Δ41 and Δ46 all functioned in fusion and binding with gH/gL and HLA class II. In fact, Δ41 displayed an increased ability to mediate membrane fusion over wild-type gp42. This truncation mutant matches the start site of wild-type soluble gp42. These findings, in combination with the evidence that deletion of the cleavage site with mutant Δ37–41 eliminates fusion, strongly suggest that gp42 must be cleaved from its transmembrane region and secreted to function in membrane fusion. This truncation study found the cleavage site to be distinct from the gH/gL binding site and provides the clearest functional importance of cleaved, secreted gp42 [73].

Discussion

Epstein–Barr virus gp42 is a well-studied protein. It has been crystallized and identified as a C-type lectin-like protein, in both bound and native structures [32, 34]. Despite its structural similarity with other members of the NK-like CTLDs, it displays a unique binding conformation with its receptor HLA class II and has a flexible N-terminal domain that carries essential sites for binding gH/gL and cleavage that are necessary for membrane fusion. In-depth sequence and structural analysis have identified no other CTLDs that share this combination of N-terminal domain features, though some small similarities exist in cleavage and secretion characteristics. Also, the binding partner for the canonical hydrophobic binding pocket has not yet been identified, though this region is also essential for fusion [25]. That this protein and others in the CTLD fold class can maintain strong structural similarity while displaying little sequence identity and diverse functionality suggests that the Epstein-Barr virus may have co-opted or mimicked a host immune protein structure in order to become more efficient in infecting host B cells and evading immune detection. EBV gp42 has been altered in a number of mutational studies that have helped to define functional regions necessary for fusion and binding of gH/gL and HLA class II [25, 72–73, 81–82]. Despite this intense study, the exact mechanics of EBV binding, fusion with and entry into host cells awaits further structural evidence of gp42 bound with gH/gL and potential ligand candidates of the hydrophobic pocket, including gB or gH/gL, if there is a direct interaction. Gp42 is not currently a therapeutic target for development of EBV vaccines, but it does provide an attractive model for small-molecule inhibition of viral infection, as evidenced by studies that blocked membrane fusion with a peptide identical to the N-terminal region from amino acids 36–81 [72]. It also will help provide insight into the mechanics of immune evasion by herpesviruses, and possesses other potential targets in the N-terminal cleavage site and the hydrophobic pocket for therapeutic intervention against EBV entry and transmission.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the members of the Longnecker, Jardetzky, and Spear laboratories for help and support. This work was supported in part by National Library of Medicine / National Institutes of Health Informationist Fellowship F37LM009568 (P.L.S.) This research was supported by AI076183 (R.L. and T.J.) AI067048 (R.L.) from National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and CA117794 from the National Cancer Institute to (R.L and T.S.J.). This work was also supported in part by a predoctoral fellowship from Northwestern’s Biotechnology Training Program from NIH (A.N.K).

Sources Cited

- 1.Rickinson A, Kieff E. In: Fields' Virology. Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 2656–2700. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henle W, Henle G. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1974;4:109–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kutok JL, Wang F. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:375–404. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maeda E, Akahane M, Kiryu S, Kato N, Yoshikawa T, Hayashi N, Aoki S, Minami M, Uozaki H, Fukayama M, Ohtomo K. Jpn J Radiol. 2009;27:4–19. doi: 10.1007/s11604-008-0291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rezk SA, Weiss LM. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1293–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stebbing J, Bower M. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:430. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70045-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumforth KR, Young LS, Flavell KJ, Constandinou C, Murray PG. Mol Pathol. 1999;52:307–322. doi: 10.1136/mp.52.6.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takada K. Mol Pathol. 2000;53:255–261. doi: 10.1136/mp.53.5.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zunt SL, Tomich CE. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1990;16:812–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1990.tb01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carbone A, Tirelli U, Gloghini A, Volpe R, Boiocchi M. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1674–1681. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.9.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purtilo DT, Szymanski I, Bhawan J, Yang JP, Hutt LM, Boto W, DeNicola L, Maier R, Thorley-Lawson D. Lancet. 1978;1:798–801. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92999-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spear PG, Longnecker R. J Virol. 2003;77:10179–10185. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10179-10185.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heldwein EE. Structure. 2009;17:147–149. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Backovic M, Jardetzky TS, Longnecker R. J Virol. 2007;81:9596–9600. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00758-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haan KM, Lee SK, Longnecker R. Virology. 2001;290:106–114. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molesworth SJ, Lake CM, Borza CM, Turk SM, Hutt-Fletcher LM. J Virol. 2000;74:6324–6332. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6324-6332.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Omerovic J, Lev L, Longnecker R. J Virol. 2005;79:12408–12415. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12408-12415.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omerovic J, Longnecker R. Virology. 2007;365:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plate AE, Smajlovic J, Jardetzky TS, Longnecker R. J Virol. 2009;83:7678–7689. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00457-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reimer JJ, Backovic M, Deshpande CG, Jardetzky T, Longnecker R. J Virol. 2009;83:734–747. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01817-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sorem J, Longnecker R. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:591–595. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.007237-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu L, Hutt-Fletcher LM. Virology. 2007;363:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirschner AN, Omerovic J, Popov B, Longnecker R, Jardetzky TS. J Virol. 2006;80:9444–9454. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00572-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, Kenyon WJ, Li Q, Mullberg J, Hutt-Fletcher LM. J Virol. 1998;72:5552–5558. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5552-5558.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silva AL, Omerovic J, Jardetzky TS, Longnecker R. J Virol. 2004;78:5946–5956. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5946-5956.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Q, Turk SM, Hutt-Fletcher LM. J Virol. 1995;69:3987–3994. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.3987-3994.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janz A, Oezel M, Kurzeder C, Mautner J, Pich D, Kost M, Hammerschmidt W, Delecluse HJ. J Virol. 2000;74:10142–10152. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.21.10142-10152.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haan KM, Kwok WW, Longnecker R, Speck P. J Virol. 2000;74:2451–2454. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2451-2454.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haan KM, Longnecker R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9252–9257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160171697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hutt-Fletcher LM. J Virol. 2007;81:7825–7832. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00445-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ressing ME, van Leeuwen D, Verreck FA, Gomez R, Heemskerk B, Toebes M, Mullen MM, Jardetzky TS, Longnecker R, Schilham MW, Ottenhoff TH, Neefjes J, Schumacher TN, Hutt-Fletcher LM, Wiertz EJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11583–11588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2034960100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mullen MM, Haan KM, Longnecker R, Jardetzky TS. Molecular cell. 2002;9:375–385. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00465-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Omerovic J, Longnecker R. Virology. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirschner AN, Sorem J, Longnecker R, Jardetzky TS. Structure. 2009;17:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ressing ME, van Leeuwen D, Verreck FA, Keating S, Gomez R, Franken KL, Ottenhoff TH, Spriggs M, Schumacher TN, Hutt-Fletcher LM, Rowe M, Wiertz EJ. J Virol. 2005;79:841–852. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.841-852.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zelensky AN, Gready JE. Proteins. 2003;52:466–477. doi: 10.1002/prot.10626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zelensky AN, Gready JE. The FEBS journal. 2005;272:6179–6217. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tormo J, Natarajan K, Margulies DH, Mariuzza RA. Nature. 1999;402:623–631. doi: 10.1038/45170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dimasi N, Moretta L, Biassoni R. Immunol Res. 2004;30:95–104. doi: 10.1385/IR:30:1:095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaiser BK, Pizarro JC, Kerns J, Strong RK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6696–6701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802736105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyington JC, Riaz AN, Patamawenu A, Coligan JE, Brooks AG, Sun PD. Immunity. 1999;10:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolan DW, Teyton L, Rudolph MG, Villmow B, Bauer S, Busch DH, Wilson IA. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:248–254. doi: 10.1038/85311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsai CJ, Lin SL, Wolfson HJ, Nussinov R. Protein Sci. 1997;6 doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petrie EJ, Clements CS, Lin J, Sullivan LC, Johnson D, Huyton T, Heroux A, Hoare HL, Beddoe T, Reid HH, Wilce MC, Brooks AG, Rossjohn J. J Exp Med. 2008;205:725–735. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deng L, Cho S, Malchiodi EL, Kerzic MC, Dam J, Mariuzza RA. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:16840–16849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801526200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dam J, Baber J, Grishaev A, Malchiodi EL, Schuck P, Bax A, Mariuzza RA. J Mol Biol. 2006;362:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Subramanian RP, Geraghty RJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2903–2908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608374104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kilpatrick DC. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2002;1572:187–197. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Altschul SF, Koonin EV. Trends in biochemical sciences. 1998;23:444–447. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Nucleic acids research. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schaffer AA, Aravind L, Madden TL, Shavirin S, Spouge JL, Wolf YI, Koonin EV, Altschul SF. Nucleic acids research. 2001;29:2994–3005. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.14.2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, Chevenet F, Dufayard JF, Guindon S, Lefort V, Lescot M, Claverie JM, Gascuel O. Nucleic acids research. 2008;36:W465–W469. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Do CB, Mahabhashyam MS, Brudno M, Batzoglou S. Genome Res. 2005;15:330–340. doi: 10.1101/gr.2821705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guindon S, Gascuel O. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chevenet F, Brun C, Banuls AL, Jacq B, Christen R. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:439. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ehlers B, Spiess K, Leendertz F, Peeters M, Boesch C, Gatherer D, McGeoch DJ. J Gen Virol. 2009 doi: 10.1099/vir.0.017251-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lacoste V, Lavergne A, de Thoisy B, Pouliquen JF, Gessain A. Infect Genet Evol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ehlers B, Ochs A, Leendertz F, Goltz M, Boesch C, Matz-Rensing K. J Virol. 2003;77:10695–10699. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10695-10699.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McMahon SA, Miller JL, Lawton JA, Kerkow DE, Hodes A, Marti-Renom MA, Doulatov S, Narayanan E, Sali A, Miller JF, Ghosh P. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:886–892. doi: 10.1038/nsmb992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ehlers B, Dural G, Yasmum N, Lembo T, de Thoisy B, Ryser-Degiorgis MP, Ulrich RG, McGeoch DJ. J Virol. 2008;82:3509–3516. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02646-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McGeoch DJ, Gatherer D, Dolan A. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:307–316. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80588-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Voigt S, Sandford GR, Ding L, Burns WH. J Virol. 2001;75:603–611. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.603-611.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Powers C, DeFilippis V, Malouli D, Fruh K. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:333–359. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Neilan JG, Borca MV, Lu Z, Kutish GF, Kleiboeker SB, Carrillo C, Zsak L, Rock DL. Journal of General Virology. 1999;80:2693–2697. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-10-2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hurtado C, Granja AG, Bustos MJ, Nogal ML, de Buitrago GG, de Yebenes VG, Salas ML, Revilla Y, Carrascosa AL. Virology. 2004;326:160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lindner I, Ehlers B, Noack S, Dural G, Yasmum N, Bauer C, Goltz M. Virology. 2007;357:134–148. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ehlers B, Ulrich S, Goltz M. Journal of General Virology. 1999;80:971–978. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-4-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Santoni F, Lindner I, Caselli E, Goltz M, Di Luca D, Ehlers B. Xenotransplantation. 2006;13:308–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2006.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li Z, Lin Q, Yang DS, Ewart KV, Hew CL. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2004;43:14547–14554. doi: 10.1021/bi048485h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gerbaud V, Pignol D, Loret E, Bertrand JA, Berland Y, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Canselier JP, Gabas N, Verdier JM. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:1057–1064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Panchenko AR, Madej T. Proteins. 2004;57:539–547. doi: 10.1002/prot.20237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kirschner AN, Lowrey AS, Longnecker R, Jardetzky TS. J Virol. 2007;81:9216–9229. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00575-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sorem J, Jardetzky TS, Longnecker R. J Virol. 2009;83:6664–6672. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00195-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Iovanna JL, Dagorn JC. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2005;1723:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schiesser M, Bimmler D, Frick TW, Graf R. Pancreas. 2001;22:186–192. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200103000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang XW, Xu WT, Zhang XW, Zhao XF, Yu XQ, Wang JX. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2009;27:556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang H, Wang H, Wang L, Song L, Song X, Zhao J, Li L, Qiu L. Dev Comp Immunol. 2009;33:780–788. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hamann J, Fiebig H, Strauss M. J Immunol. 1993;150:4920–4927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moretta A, Bottino C, Vitale M, Pende D, Cantoni C, Mingari MC, Biassoni R, Moretta L. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:197–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wu L, Hutt-Fletcher LM. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:2129–2136. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82949-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McShane MP, Mullen MM, Haan KM, Jardetzky TS, Longnecker R. J Virol. 2003;77:7655–7662. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7655-7662.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Spriggs MK, Armitage RJ, Comeau MR, Strockbine L, Farrah T, Macduff B, Ulrich D, Alderson MR, Mullberg J, Cohen JI. J Virol. 1996;70:5557–5563. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5557-5563.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]