Abstract

BACKGROUND

Cancer patients admitted to a palliative care unit generally have a poor prognosis. The role of antineoplastic therapy (ANT) in these patients is controversial. We examined the frequency and predictors associated with ANT use in hospitalized patients who required an acute palliative care unit (APCU) stay.

METHODS

We included all 2604 patients admitted over a five-year period to a 12-bed APCU located within a National Cancer Institute comprehensive cancer center, where patients can access both palliative care and ANT. We retrospectively retrieved from institutional databases patient demographics, cancer diagnosis, ANT use, length of hospital stay, and survival from time of admission.

RESULTS

The median hospital stay was 11 days and the median survival was 22 days. During hospitalization, 435 patients (17%) received ANT, including chemotherapy (N=297, 11%), hormonal agents (N=54, 2%) and targeted therapy (N=155, 6%). No significant change in frequency of ANT use was detected over the 5 year period. Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that younger age, specific cancer diagnoses and longer admissions were independently associated with ANT use.

CONCLUSION

The use of ANT during hospitalization that included an APCU stay was limited to a small percentage of patients, and did not increase over time. ANT use was associated with younger age, specific cancer diagnoses and longer admissions. The APCU facilitates simultaneous care where patients access palliative care while on ANT.

Keywords: neoplasms, therapeutics, antineoplastic agents, targeted agents, palliative care

INTRODUCTION

Patients with advanced cancer inevitably experience progressive functional decline and psychological distress. As patients transition from advanced to far advanced stages of disease (i.e. expected survival less than 3 months), palliative care plays an increasingly important role by providing symptom control and psychosocial counseling, and facilitating healthcare decision making. Patients who require admission under palliative care generally have a poor prognosis, with a median survival of weeks.1–5 During this critical end-of-life period, patients, family members and the healthcare team are faced with a multitude of complex healthcare decisions.

Some of the most challenging of these complex decisions concern the initiation, continuation and withdrawal of palliative anti-neoplastic therapy (ANT).6 Because of a lack of clear guidance for the use of ANT at the end-of-life and the difficulty in estimating survival for patients with advanced cancer, the decision to administer or withhold ANT is currently being made on a case-by-case basis, taking into account patients’ wishes along with clinical, logistic and financial considerations.7

The role of ANT for patients admitted to the APCU is controversial. Some institutions have a policy of discontinuing all ANT on admission to the APCU, which forces patients to choose between cancer treatments and optimal palliative care. Others propose a simultaneous care model in which patients receive palliative care while on ANT.8–10 Lagman et al. described their experience with cancer patients admitted to an inpatient palliative care unit at the Cleveland Clinic, where 13% were treated with radiotherapy, chemotherapy or both.11 Another retrospective study from a Japanese Cancer Center reported only 3 of 201 patients admitted to its palliative care unit received chemotherapy.12

There has been little documentation of the extent, trends and predictors of ANT use in patients who require an APCU stay. A better understanding of the current pattern of ANT use would provide insights into how palliative care can be integrated into oncology practice under a simultaneous care model. Using a retrospective cohort design, we examined the frequency, factors and duration between admission and death associated with ANT use in hospitalized patients who required an APCU stay.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Subjects

The Institutional Review Board at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center approved this study and waived informed consent. All cancer patients admitted to the APCU at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center between September 1, 2003 and August 31, 2008 were included in this retrospective cohort study. These dates were chosen to correspond to the institution’s fiscal year, which begins on September 1 and ends on August 31 of the following year. For patients with multiple admissions to the APCU, only the last available admission was included for analysis since this admission is closest to the end-of-life, providing insights into the extent of ANT use in patients with far advanced cancer.

Our 12-bed APCU was opened at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in 2002. Staffed by an interdisciplinary team of physicians, nurses, social workers, physiotherapists and a chaplain, one goal of the APCU is to provide symptom management for patients with advanced cancer and severe physical and/or psychosocial distress, and to provide emotional support for their families.13

Patient Characteristics and Duration between Admission and Death

We retrospectively retrieved patient demographics (age, sex, race and religion), cancer diagnosis, durations of the entire hospitalization and APCU stays from institutional databases. We also collected information about ANT used between the dates of hospital admission and discharge from our institutional pharmacy databases. To ensure consistency and accuracy of data, we conducted further reviews of patient electronic health records when any discrepancy was detected. Survival outcome was obtained from the Tumor Registry Vital Statistics Database, with further review of electronic chart records to obtain the date of last followup when necessary.

We examined ANTs use during the entire hospitalization period, rather than the APCU period alone, because the periods leading to APCU admission and immediately after APCU discharge were very much related to the APCU stay, with similar patient characteristics and disease severity. Among patients with multiple cancer diagnoses, the most responsible cancer diagnosis for hospitalization was used for analysis.

ANT Use

Decisions to initiate, continue or stop ANT were made on a case-by-case basis, with key guidance provided by the patients’ oncologists. Patients admitted to our APCU are able to receive ANT; however, our nurses are not certified to administer cytotoxic or targeted therapies intravenously. Thus, arrangements are made to facilitate administration of parenteral ANT, such as temporary transfer to the outpatient chemotherapy unit or to an oncology inpatient unit.

ANTs were categorized into chemotherapeutic agents, hormonal agents and targeted therapy. In this study, biologic agents such as interferon were classified as targeted therapy.

Megestrol acetate may be used either for anti-cancer therapy or for treatment of anorexia-cachexia. Thus, for patients who received this medication, we reviewed the indications to determine whether it had been used as ANT. Bisphosphonates and corticosteroids were not considered ANT in this study.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized baseline demographics, admission characteristics and ANT utilization using descriptive statistics, including medians, means, standard deviations, ranges, and frequencies together with 95% confidence intervals. The chi-square test was used to determine the yearly trend of ANT utilization.

We compared the baseline and admission characteristics between patients who received ANT and those who did not receive ANT. Comparisons were made using the Student’s t-test for continuous variables that were normally distributed (i.e. age), the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous, non-parametric variables (e.g. admission length), and Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables (e.g. race, religion). Variables associated with a P-value of 0.20 or less in univariate analysis were then fitted in a logistic regression model with backward elimination to identify factors associated with ANT during hospitalization. A two-sided P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Survival analysis was plotted by using the Kaplan-Meier method.14 Overall survival was calculated from the time of hospital admission to death from any cause or date last known alive.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 16.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) software was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

The characteristics of the 2604 patients who required admission to the APCU during the study period are shown in Table 1. Respiratory, gastrointestinal and genitourinary malignancies constituted more than half of all cases. A total of 740 (28%) patients were admitted to and discharged directly from the APCU; the remainder had both an oncology unit and APCU stay. The median duration between admission and death for the entire cohort was 22 days.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of 2604 Cancer Patients who required APCU Admission

| Number (%a) | |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 59 (18–101) |

| Female | 1273 (48.9) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 1745 (67.0) |

| Black | 422 (16.2) |

| Hispanic | 307 (11.8) |

| Others | 130 (5.0) |

| Religionb | |

| Christian | 2119 (94) |

| Others | 135 (5.9) |

| Cancer diagnosis | |

| Respiratory | 595 (22.9) |

| Gastrointestinal | 512 (19.7) |

| Hematologic | 304 (11.7) |

| Gynecologic | 271 (10.4) |

| Genitourinary | 217 (8.3) |

| Breast | 207 (8.0) |

| Head and neck | 155 (6.0) |

| Sarcoma | 104 (4.0) |

| Dermatologic | 99 (3.8) |

| Primary unknown | 92 (3.5) |

| Central nervous system | 26 (1.0) |

| Endocrine | 22 (0.8) |

| Admission type | |

| APCU only | 740 (28.4) |

| Oncology ward and APCU | 1864 (71.6) |

| Median admission duration | |

| MDA hospital stay in days (Q1–Q3) | 11 (8–17) |

| APCU stay in days (Q1–Q3) | 7 (4–10) |

| Antineoplastic agent use during admissionc | |

| Chemotherapeutic agents | 297 (11.4) |

| Hormonal agents | 54 (2.1) |

| Targeted agents | 155 (6.0) |

ANT: antineoplastic therapy; APCU: acute palliative care unit; MDA: M. D. Anderson Cancer Center

unless otherwise stated.

Information regarding religion was not available for 350 patients.

Of the 435 patients who received ANT, 69 patients received two classes of agents, and 1 received all three classes.

Frequency of ANT Use

During their hospitalization that included an APCU stay, 435 patients received ANT, including chemotherapy (N=297, 11%), hormonal agents (N=54, 2%) and targeted therapy (N=155, 6%). Among these patients, 58 received both chemotherapeutic agents and targeted agents, 11 received both chemotherapeutic agents and hormonal agents, and 1 received all three classes of agents. Thirty six patients (1%) received ANT as part of an experimental clinical trial. Overall, 2169 (83%) patients received no ANT during the APCU admission.

The median number of ANT during the entire hospitalization was 1 (interquartile range [Q1–Q3] 1–2), with a median number of 2 doses (Q1–Q3 1–2) per patient. The most commonly used chemotherapeutic agents included cytarabine (intravenous/intrathecal, n=58), gemcitabine (n=52), paclitaxel (n=44), hydroxyurea (n=40), carboplatin (n=30), cisplatin (n=27), methotrexate (intravenous/intrathecal, n=22), doxorubicin (n=22) and cyclophosphamide (n=22). The top three hormonal agents were anastrozole (n=10), letrozole (n=10) and leuprolide (n=9). The targeted therapies used were erlotinib (n=28), rituximab (n=22), gefitinib (n=19), bevacizumab (n=14), bortezomib (n=9), sorafenib (n=8), cetuximab (n=7), trastuzumab (n=6), imatinib (n=4) and sunitinib (n=4).

During their APCU stay, 82 (3%), 35 (1%) and 58 (2%) patients received chemotherapy, hormonal agents and targeted therapy, respectively. 382 (15%) patients started ANT while admitted under an oncology service, and 52 (2%) received their first dose after transfer to the APCU. Among the patients who were treated with chemotherapeutic, hormonal and targeted agents during hospitalization, 10%, 26% and 12% received the ANT after they were transferred to the APCU, respectively.

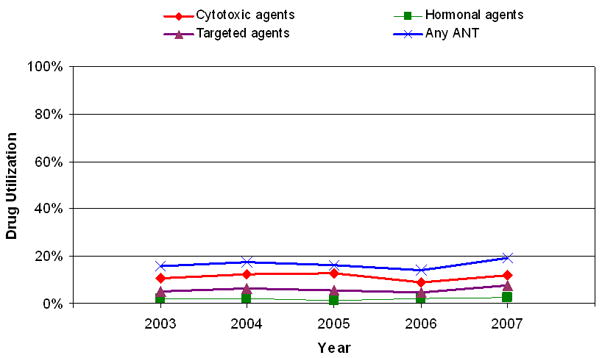

Yearly Trends of ANT Use

The frequency of ANT use during the entire hospitalization over the 5 year period is shown in Fig 1. Overall, no significant variation in the frequency of use was noted for chemotherapy, hormonal therapy and targeted agents. We also examined the yearly trend of ANT use during APCU admission and found no significant changes over time (data not shown).

FIGURE 1. Frequency of antineoplastic therapy (ANT) use by year.

The frequency of cytotoxic, hormonal, targeted and any ANT agent use is plotted between 2003 and 2007. The P-values were 0.93, 0.64, 0.30 and 0.61 (chi-square test for trend), respectively.

Factors Associated with ANT Use

Table 2 highlights the factors associated with chemotherapy, hormonal therapy and targeted therapy use by univariate analysis, and Table 3 lists variables that were significant in multivariate logistic regression analysis. Factors associated with chemotherapy use included younger age, longer hospital stay, shorter APCU stay and admissions that included an oncology unit stay in addition to APCU stay. Patients with hematologic (37%), dermatologic (18%), genitourinary (15%), primary unknown (14%) and breast (13%) malignancies were also more likely than were patients with other cancer diagnoses to receive chemotherapeutic agents during their last hospital admission that included an APCU stay. All of these factors remained significant in multivariate analysis.

TABLE 2.

Factors Associated with Anti-Neoplastic Therapy Use during Hospital Admission that included an APCU Stay

| Chemotherapeutic Agents | Hormonal Agents | Targeted Agents | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Chemo (N=2307) | Chemo (N=297) | P-valuea | No hormones (N=2550) | Hormones (N=54) | P-valuea | No targeted therapy(N=2449) | Targeted therapy(N=155) | P-valuea | |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 58.9 (13.4) | 54.0 (14.9) | <0.001 | 58.3±13.6 | 59.1±13.6 | 0.66 | 58.6±13.6 | 53.8±14.6 | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 1123 (88.2%) | 150 (11.8%) | 0.55 | 1231 (96.7%) | 42 (3.3%) | <0.001 | 1195 (93.9%) | 78 (6.1%) | 0.71 |

| Male | 1184 (89%) | 147 (11%) | 1319 (99.1%) | 12 (0.9%) | 1254 (94.2%) | 77 (5.8%) | |||

| Race | |||||||||

| White | 1543 (88.4%) | 203 (11.6%) | 0.77 | 1712 (98.1%) | 34 (1.9%) | 0.83 | 1646 (94.3%) | 100 (5.7%) | 0.018 |

| Black | 374 (88.6%) | 48 (11.4%) | 413 (97.9%) | 9 (2.1%) | 390 (92.4%) | 32 (7.6%) | |||

| Hispanic | 272 (88.6%) | 35 (11.4%) | 300 (97.7%) | 7 (2.3%) | 297 (96.7%) | 10 (3.3%) | |||

| Others | 118 (91.5%) | 11 (8.5%) | 125 (96.9%) | 4 (3.1%) | 116 (89.9%) | 13 (10.1%) | |||

| Religion | |||||||||

| Christian | 1886 (89.0%) | 233 (11.0%) | 0.27 | 2075 (97.9%) | 44 (2.1%) | 0.28 | 2001 (94.4%) | 118 (5.6%) | 0.21 |

| Non-Christian | 116 (85.9%) | 19 (14.1%) | 134 (99.3%) | 1 (0.7%) | 124 (91.9%) | 11 (8.1%) | |||

| Cancer typesb | |||||||||

| Hematologic | 191 (62.8%) | 113 (37.2%) | <0.001 | 300 (98.7%) | 4 (1.3%) | 0.23 | 250 (82.2%) | 54 (17.8%) | <0.001 |

| Solid tumors | 2116 (92.0%) | 184 (8.0%) | 2250 (97.8%) | 50 (2.2%) | 2199 (95.6%) | 101 (4.4%) | |||

| Dermatologic | 81 (81.8%) | 18 (18.2%) | 99 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 91 (91.9%) | 8 (8.1%) | |||

| Genitourinary | 230 (84.9%) | 41 (15.1%) | 262 (96.7%) | 9 (3.3%) | 256 (94.5%) | 15 (5.5%) | |||

| Primary unknown | 79 (85.9%) | 13 (14.1%) | 90 (97.8%) | 2 (2.2%) | 79 (85.9%) | 13 (14.1%) | |||

| Breast | 180 (87.0%) | 27 (13.0%) | 186 (89.9%) | 21 (10.1%) | 198 (95.7%) | 9 (4.3%) | |||

| Endocrine | 20 (90.9%) | 2 (9.1%) | 22 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 22 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| Gynecologic | 199 (91.7%) | 18 (8.3%) | 207 (95.4%) | 10 (4.6%) | 215 (99.1%) | 2 (0.9%) | |||

| Gastrointestinal | 482 (94.1%) | 30 (5.9%) | 510 (99.6%) | 2 (0.4%) | 498 (97.3%) | 14 (2.7%) | |||

| Head and neck | 148 (95.5%) | 7 (4.5%) | 155 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 148 (95.5%) | 7 (4.5%) | |||

| Respiratory | 572 (96.1%) | 23 (3.9%) | 589 (99%) | 6 (1%) | 555 (93.3%) | 40 (6.7%) | |||

| Sarcoma | 100 (96.2%) | 4 (3.8%) | 104 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 103 (99.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | |||

| CNS | 25 (96.2%) | 1 (3.8%) | 26 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 26 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| Admission type | |||||||||

| PCU only | 720 (97.3%) | 20 (2.7%) | <0.001 | 728 (98.4%) | 12 (1.6%) | 0.31 | 712 (96.2%) | 28 (3.8%) | 0.003 |

| Onc ward/APCU | 1587 (85.1%) | 277 (14.8%) | 1822 (97.7%) | 42 (2.3%) | 1737 (93.2%) | 127 (6.8%) | |||

| Median MDA hospital admission length, days (Q1–Q3) | 7 (11–16) | 18 (11–26) | <0.001 | 11 (8–17) | 13.5 (9–21) | 0.051 | 11 (8–17) | 15 (10–26) | <0.001 |

| Median APCU admission length, days (Q1–Q3) | 7 (4–10) | 7 (4–9) | 0.003 | 7 (4–10) | 7 (5–9) | 1.0 | 7 (4–10) | 6 (4–9) | 0.11 |

APCU: acute palliative care unit; CI: confidence interval; CNS: Central nervous system; MDA: M. D. Anderson Cancer Center; SD: standard deviation

Comparisons were made between patients who received ANT and those who did not receive ANT; the Chi-square test was used for categorical variables; Student t-test for age; and Mann Whitney test was used for median hospital admission and APCU admission length.

Comparisons were made between all solid tumors and hematogical malignancies using the Chi-square test for chemotherapy and targeted agents, and Fisher’s exact test for hormonal agents

Interval between hospital admission and death or last day of followup if alive

TABLE 3.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis for Factors associated with Anti-Neoplastic Agent Use during Hospital Admission that included an APCU Stay

| Chemotherapeutic agents | Hormonal agents | Targeted agents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-valuea | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-valuea | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-valuea | |

| Age, per year | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | <0.001 | - - | - | 0.97 (0.96–0.99) | <0.001 |

| Cancer types | - - | <0.001 | - - | <0.001 | - - | 0.001 |

| Hematologic | 8 (4.8–13.2) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.3–3.7) | 0.95 | 1.6 (0.9–2.6) | 0.11 |

| Dermatologic | 4 (2.0–7.9) | <0.001 | - - | - | 1 (0.4–2.4) | 1 |

| Genitourinary | 4.4 (2.6–7.6) | <0.001 | 3.3 (1.2–9.4) | 0.024 | 0.57 (0.28–1.18) | 0.14 |

| Primary unknown | 3.5 (1.7–7.4) | <0.001 | 2.1 (0.4–10.6) | 0.37 | 0.67 (0.23–2.0) | 0.47 |

| Breast | 3.3 (1.8–5.9) | <0.001 | 11.4 (4.5–28.6) | <0.001 | 0.57 (0.3–1.2) | 0.15 |

| Endocrine | 2.1 (0.4–9.9) | 0.35 | - - | - | - - | - |

| Gynecologic | 1.8 (0.9–3.5) | 0.077 | 4.7 (1.7–13.2) | 0.003 | 0.12 (0.03–0.51) | 0.004 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1.5 (0.8–2.6) | 0.19 | 0.4 (0.08–1.9) | 0.24 | 0.32 (0.16–0.65) | 0.001 |

| Head and neck | 1.2 (0.5–2.9) | 0.69 | - - | - | 0.39 (0.14–1.1) | 0.08 |

| Respiratory | 1 (ref.) | - | 1 (ref.) | - | 1 (ref.) | - |

| Sarcoma | 0.6 (0.2–1.9) | 0.41 | - - | - | - - | - |

| CNS | 0.6 (0.08–5.0) | 0.67 | - - | - | - - | - |

| PCU only admission | 0.31 (0.19–0.51) | <0.001 | - - | - | - - | - |

| MDA Hospital admission length, per day | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) | <0.001 | 1.02 (1.0–1.05) | 0.035 | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | <0.001 |

| APCU admission length, per day | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | 0.01 | - - | - | 0.94 (0.90–0.98) | 0.007 |

APCU: acute palliative care unit; CI: confidence interval; CNS: Central nervous system; MDA: M. D. Anderson Cancer Center; Ref.: reference. – denotes non-significant values

Hormonal agent use was associated with specific cancer diagnoses (breast 10%; gynecologic 5%; and genitourinary 3%) and longer hospital stays in multivariate analysis.

In univariate analysis, the use of targeted therapy was more common with younger age, race, longer hospital stay, shorter APCU stay and admissions that included oncology ward stay in addition to APCU stay. Cancer diagnoses associated with targeted therapy use included hematologic (17%), primary unknown (14%), dermatologic (8%), and respiratory (7%). In multivariate logistic regression, age, cancer diagnosis, hospital admission length, and APCU admission length were independently associated with targeted agent use.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that the vast majority of patients who required admission to our APCU did not receive ANT, and that the frequency of ANT did not increase over time. ANT use was associated with younger age, specific cancer diagnoses and longer hospital stays.

This study provides a comprehensive examination of the extent of chemotherapeutic, hormonal and targeted agent use in patients with far advanced cancer who required admission to an APCU. Among 435 (17%) patients for whom ANT was prescribed, 70% received cytotoxic agents. The frequency of chemotherapy use in our institution is consistent with findings from a recent report from another comprehensive cancer center.11 We did not detect an increase in ANT use over the 5-year period. One explanation is that ANT use may have reached a plateau among patients with advanced refractory cancer, limited by patients’ performance status, cost of therapy, and the slow United States Food and Drug Administration approval process for many novel agents.

Patients admitted to our APCU were more likely to receive ANT than were those admitted to hospices across the United States.15 First, our APCU is situated within a comprehensive cancer center that offers a full array of novel cancer therapies and clinical trials. Second, our patients tend to be young and highly motivated, with a good performance status and high socioeconomic status relative to the general oncology patient population. Third, our palliative care program provides simultaneous care in the outpatients and inpatient settings, where patients can access both palliative care and ANT.

We found that younger age, some cancer diagnoses and longer hospital admissions were associated with ANT use. In particular, hematological malignancy was a strong predictor of chemotherapy and targeted therapy use. Indeed, studies from our institution and from others have shown that patients with hematologic malignancies are more likely to be treated aggressively, to die in intensive care units, and to have delayed referrals to palliative care compared to patients with solid tumors.16–18 Not surprisingly, breast, genitourinary and gynecologic malignancies were associated with hormonal therapy use in our cohort.

The overall length of hospital stay increased with ANT use, which could be explained by the extra time needed for treatment administration and for patients to recover from therapy. Administration of ANT was also associated with a shorter stay in the APCU; thus, patients who received ANT spent a proportionally larger amount of time in the oncology ward. Of note, neither race nor religion was a key consideration in the frequency of ANT use.

Both the American Society of Clinical Oncology19–21 and the National Quality Forum22 have stated that chemotherapy use within 14 days of death is an indicator of poor end-of-life care. Only 5.5% of patients in our cohort met this criterion. While the principle of minimizing aggressive therapies in dying patients is fundamentally sound, survival estimation is extremely difficult, with no standard prognostic tools available for advanced cancer patients.23–26 More research is necessary to establish predictors of survival in this population. Until highly accurate prognostic models such as the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) Score27 in the critical care setting become available for advanced cancer patients, the application of duration between chemotherapy and death as an indictor of quality of care is challenging. Other reasons for administration of ANT close to the end-of-life include heightened expectations and the hope of life-prolongation and symptom control.7, 28–35 Some patients may have a narrow window of opportunity for therapeutic intervention, and a trial of ANT may appear to be reasonable. Another reason is the increasing availability of new ANT over the past decade. Many of these agents are associated with fewer adverse effects than older agents, making it possible for patients to receive ANT later in the trajectory of illness.

One of the problems with chemotherapy administration close to the end-of-life is that it poses a barrier for patients with far advanced cancer to receive palliative care and hospice services, since they frequently have to “give up” ANT before enrollment onto these programs.36 In our series, all patients who received chemotherapy had access to both palliative care and oncology teams, highlighting a key advantage of an integrated palliative care program. Indeed, a strong integration of palliative care into oncology practice under the simultaneous care model may enhance the care of advanced cancer patients who require ANT.10, 37 First, optimal symptom management would support patients through treatments, and help maintain their quality of life. Second, the simultaneous model would allow palliative care to be introduced earlier in patients’ disease trajectory, and in the process significantly increase its effectiveness through timely symptom control, psychosocial interventions and transition of care. This is in contrast to the traditional dichotomized model of active treatment and palliative care/hospice, which results in fragmented care, delayed palliative care referrals, the need to sacrifice quality of life for potential gain in quantity of life, and significant emotional distress.34

This study had a number of limitations. First, our study was only able to examine treatments given during hospital admissions that included an APCU stay. Due to the short survival in our cohort, we believe the likelihood of ANT use after APCU discharge is minimal. However, further studies are required to address ANT use before and after admission. Second, a number of potential determinants of ANT, such as education level, socioeconomic status, cancer stage, location of metastases, symptom profile and performance status were not available. Indeed, universal documentation of symptoms and performance status during the APCU admission would help to assess the potential impact of palliative care on physical and psychosocial distress at the end-of-life. Finally, patients who are treated at our comprehensive cancer center and the treatments that they received may not be representative of cancer patients and treatments throughout the United States, and thus the results may not be generalizable.

In summary, our APCU served advanced cancer patients with unique clinical characteristics and treatment needs, and facilitated simultaneous care. In the era of personalized medicine, we need to develop not only novel therapeutics targeting specific mutations within the cancer, but also symptom management strategies and psychosocial interventions tailored to patients’ needs and the disease trajectory. Identification of clinical and pathologic markers to better predict clinical benefits and adverse effects associated with ANT, coupled with improved prognostication skills and treatment-decision tools, would allow us to better customize therapeutic decisions. The further integration of palliative care into the practice of oncology under a simultaneous care model will improve our patients’ access to palliative care, and hopefully improve their quality of life.

Acknowledgments

Research support: EB is supported in part by National Institutes of Health (grant numbers RO1CA1RO10162-01A1, RO1CA1222292-01 and RO1CA124481-01). DH is funded by the Clinician Investigator Program, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

We thank Ms. Olubumi Akiwumi for her assistance with database management, and Ms. Tamara Locke for review of manuscript.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures from any authors.

References

- 1.Rees E, Hardy J, Ling J, Broadley K, A’Hern R. The use of the edmonton symptom assessment scale (ESAS) within a palliative care unit in the UK. Palliat Med. 1998;12:75–82. doi: 10.1191/026921698674135173. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lam PT, Leung MW, Tse CY. Identifying prognostic factors for survival in advanced cancer patients: A prospective study. Hong Kong Med J. 2007;13:453–459. [serial online] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moro C, Brunelli C, Miccinesi G, et al. Edmonton symptom assessment scale: Italian validation in two palliative care settings. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:30–37. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0834-3. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costantini M, Toscani F, Gallucci M, et al. Terminal cancer patients and timing of referral to palliative care: A multicenter prospective cohort study. italian cooperative research group on palliative medicine. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00084-6. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paci E, Miccinesi G, Toscani F, et al. Quality of life assessment and outcome of palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21:179–188. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00263-9. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Browner I, Carducci MA. Palliative chemotherapy: Historical perspective, applications, and controversies. Semin Oncol. 2005;32:145–155. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.11.014. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuyama R, Reddy S, Smith TJ. Why do patients choose chemotherapy near the end of life? A review of the perspective of those facing death from cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3490–3496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyers FJ, Linder J, Beckett L, Christensen S, Blais J, Gandara DR. Simultaneous care: A model approach to the perceived conflict between investigational therapy and palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:548–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.03.002. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyers FJ, Linder J. Simultaneous care: Disease treatment and palliative care throughout illness. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1412–1415. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.104. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lagman R, Walsh D. Integration of palliative medicine into comprehensive cancer care. Semin Oncol. 2005;32:134–138. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.11.015. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lagman R, Rivera N, Walsh D, LeGrand S, Davis MP. Acute inpatient palliative medicine in a cancer center: Clinical problems and medical interventions--a prospective study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2007;24:20–28. doi: 10.1177/1049909106295292. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sato K, Miyashita M, Morita T, Sanjo M, Shima Y, Uchitomi Y. Quality of end-of-life treatment for cancer patients in general wards and the palliative care unit at a regional cancer center in japan: A retrospective chart review. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:113–122. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0332-x. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elsayem A, Swint K, Fisch MJ, et al. Palliative care inpatient service in a comprehensive cancer center: Clinical and financial outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2008–2014. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.003. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mintzer DM, Zagrabbe K. On how increasing numbers of newer cancer therapies further delay referral to hospice: The increasing palliative care imperative. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2007;24:126–130. doi: 10.1177/1049909106297363. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng WW, Willey J, Palmer JL, Zhang T, Bruera E. Interval between palliative care referral and death among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:1025–1032. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1025. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, Zhang T, Braiteh F, Bruera E. Predictors of access to palliative care services among patients who died at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:1146–1152. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0259. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGrath P. Are we making progress? not in haematology! Omega (Westport) 2002;45:331–348. doi: 10.2190/KU5Q-LL8M-FPPA-LT3W. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cancer care during the last phase of life. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1986–1996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNiff KK, Neuss MN, Jacobson JO, Eisenberg PD, Kadlubek P, Simone JV. Measuring supportive care in medical oncology practice: Lessons learned from the quality oncology practice initiative. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3832–3837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Earle CC, Park ER, Lai B, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ, Block S. Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative data. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1133–1138. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.059. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality. Washington, USA: National Quality Forum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamont EB, Christakis NA. Some elements of prognosis in terminal cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 1999;13:1165–70. [serial online] discussion 1172–4, 1179–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamont EB, Christakis NA. Physician factors in the timing of cancer patient referral to hospice palliative care. Cancer. 2002;94:2733–2737. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10530. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glare PA, Sinclair CT. Palliative medicine review: Prognostication. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:84–103. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9992. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maltoni M, Caraceni A, Brunelli C, et al. Prognostic factors in advanced cancer patients: Evidence-based clinical recommendations--a study by the steering committee of the european association for palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6240–6248. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA, McNair DS, Malila FM. Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) IV: Hospital mortality assessment for today’s critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1297–1310. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000215112.84523.F0. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grunfeld EA, Ramirez AJ, Maher EJ, et al. Chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer: What influences oncologists’ decision-making? Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1172–1178. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1733. [serial online] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doyle C, Crump M, Pintilie M, Oza AM. Does palliative chemotherapy palliate? evaluation of expectations, outcomes, and costs in women receiving chemotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1266–1274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1266. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koedoot CG, De Haes JC, Heisterkamp SH, Bakker PJ, De Graeff A, De Haan RJ. Palliative chemotherapy or watchful waiting? A vignettes study among oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3658–3664. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.12.012. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geels P, Eisenhauer E, Bezjak A, Zee B, Day A. Palliative effect of chemotherapy: Objective tumor response is associated with symptom improvement in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2395–2405. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.12.2395. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shanafelt TD, Loprinzi C, Marks R, Novotny P, Sloan J. Are chemotherapy response rates related to treatment-induced survival prolongations in patients with advanced cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1966–1974. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.176. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grunfeld EA, Maher EJ, Browne S, et al. Advanced breast cancer patients’ perceptions of decision making for palliative chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1090–1098. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.9208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koedoot CG, de Haan RJ, Stiggelbout AM, et al. Palliative chemotherapy or best supportive care? A prospective study explaining patients’ treatment preference and choice. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:2219–2226. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601445. [serial online] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrington SE, Smith TJ. The role of chemotherapy at the end of life: “when is enough, enough?”. JAMA. 2008;299:2667–2678. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.22.2667. [serial online] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ford DW, Nietert PJ, Zapka J, Zoller JS, Silvestri GA. Barriers to hospice enrollment among lung cancer patients: A survey of family members and physicians. Palliat Support Care. 2008;6:357–362. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000564. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Golan H, Bielorai B, Grebler D, Izraeli S, Rechavi G, Toren A. Integration of a palliative and terminal care center into a comprehensive pediatric oncology department. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:949–955. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21476. [serial online] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]