Abstract

Background: It is unclear how well surrogate markers for vitamin D exposure (eg, oral intake of vitamin D and estimates of sunlight exposure), with and without consideration of other potential predictors of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations, similarly rank individuals with respect to 25(OH)D blood concentrations.

Objective: The objective was to determine how much variation in serum 25(OH)D concentrations (nmol/L) could be explained by a predictive model with the use of different vitamin D surrogate markers (latitude of residence, mean annual regional solar irradiance estimates, and oral sources) and other individual characteristics that might influence vitamin D status.

Design: A random sample of 3055 postmenopausal women (aged 50–70 y) participating in 3 nested case-control studies of the Women's Health Initiative Calcium plus Vitamin D Clinical Trial was used. Serum 25(OH)D values, assessed at year 1 (1995–2000), and potential predictors of 25(OH)D concentrations, assessed at year 1 or Women's Health Initiative baseline (1993–1998), were used.

Results: More than half of the women (57.1%) had deficient (<50 nmol/L) concentrations of 25(OH)D. Distributions of 25(OH)D concentrations by level of latitude of residence, mean annual regional solar irradiance, and intake of vitamin D varied considerably. The predictive model for 25(OH)D explained 21% of the variation in 25(OH)D concentrations. After adjustment for month of blood draw, breast cancer status, colorectal cancer status, fracture status, participation in the hormone therapy trial, and randomization to the dietary modification trial, the predictive model included total vitamin D intake from foods and supplements, waist circumference, recreational physical activity, race-ethnicity, regional solar irradiance, and age.

Conclusions: Surrogate markers for 25(OH)D concentrations, although somewhat correlated, do not adequately reflect serum vitamin D measures. These markers and predictive models of blood 25(OH)D concentrations should not be given as much weight in epidemiologic studies of cancer risk.

INTRODUCTION

Ecologic studies have investigated associations between cancer incidence and regional measures of solar irradiance, with the latter as a surrogate marker for vitamin D status (reviewed in reference 1). In parallel, analytic epidemiologic studies have analyzed associations of cancer risk with 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations (the accepted biomarker for determining nutritional vitamin D status in humans (2)) and individually assessed surrogate makers of vitamin D status (eg, oral intake of vitamin D and estimates of sunlight exposure) (3–5). It is not fully understood how well different surrogate measures of vitamin D exposure similarly rank individuals with respect to serum 25(OH)D. A better understanding of the ability of such surrogate markers to predict individual 25(OH)D concentrations, with and without consideration of other potential predictors of vitamin D status, will help researchers better interpret past and future studies using such markers in the study of relation of vitamin D exposure to disease risk.

Using data from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) Calcium plus Vitamin D (CaD) clinical trial, we sought to 1) compare how well surrogate makers of vitamin D status (latitude of residence, mean annual regional solar irradiance estimates, and oral sources) correlate with individually assessed serum 25(OH)D concentrations and 2) develop a predictive model to estimate 25(OH)D concentrations using different surrogate makers for vitamin D status and other individual characteristics that might influence vitamin D status (eg, age, race-ethnicity, body mass index, and physical activity). In particular, we sought to determine how much variation in 25(OH)D concentrations could be explained by this predictive model.

The WHI CaD clinical trial provides a unique opportunity to study predictors of vitamin D in an aging cohort of postmenopausal women. WHI is a rich data source that includes information on many individual characteristics that might influence vitamin D status, such as extensive dietary and supplement intake data. CaD participants, moreover, are from multiple race-ethnicity groups and reside in geographically varied locations, coming from 40 clinic centers nationwide across a range of latitudes.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Sample selection

At the WHI Clinical Trial (WHI-CT) baseline (1993–1998), postmenopausal women (age 50–79 y) were enrolled in the WHI hormone therapy (HT) (n = 27,347) (6) or dietary modification (DM) (n = 48,835) (7) clinical trials. Participants of the HT or DM trials were approached at their year 1 visit to also join the CaD trial. If women agreed to participate, they were randomly assigned to receive active medication or placebo at WHI-CT year 1. All trial participants had a 12-h fasting blood sample drawn at enrollment and again at WHI-CT year 1 (1995–2000) (8). After the year 1 visit, participants in these trials were also invited to enroll in a randomized clinical trial of calcium plus vitamin D compared with placebo, which included a total enrollment of 36,282 women (8).

Within the CaD trial, 3 nested case-control studies were conducted to analyze associations between serum concentrations of 25(OH)D and incidence of colorectal cancer, breast cancer, or hip, spine, or lower wrist fracture (9–11), providing 4785 WHI-CT participants (2792 cases and 1993 matched controls) with year 1 serum 25(OH)D values. Controls were matched to cases on age, race-ethnicity, blood draw date, and clinic center at CaD randomization. The breast cancer nested case-control study was also matched on HT and DM trial arm.

To study predictors of serum 25(OH)D, we excluded participants who, at WHI-CT baseline, self-reported high blood calcium concentrations (n = 23) or conditions that could affect vitamin D absorption in the gut (a history of ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease, surgery to remove part of the intestine, or use of a special diet for malabsorption, celiac sprue, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn disease; n = 115). Participants who self-reported incident cancer between WHI-CT baseline and year 1 (n = 69) were also excluded. This provided a sample size of 4583 women for these analyses. The Institutional Review Boards at each participating institution approved all protocols and consent forms. All women provided signed informed consent.

Data collection

At WHI-CT baseline and year 1, concurrent with the serum 25(OH)D assessment, participants provided self-reported data via questionnaires on demographics, disease risk factors, family and medical history, and physical measurements (eg, blood pressure, height, weight, blood samples) (8).

Dietary and supplement data

At WHI-CT baseline, vitamin D intake from foods was estimated from a self-administered food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) specifically designed for WHI (12), to assess usual dietary intake over the previous 3 mo. The FFQ was also administered at year 1, but only in the DM trial (n = 3142). Therefore, dietary vitamin D data collected at year 1 [concurrent with the time serum was obtained for determining 25(OH)D concentrations] was used when possible; otherwise reported baseline dietary vitamin D intake was used. The Pearson correlation coefficient among DM trial participants, for dietary vitamin D intake at baseline and year 1, was 0.59 (P < 0.0001). A standardized, in-person, interviewer-administered form was used to collect information on the dose, frequency, and duration of current supplement use at year 1 (13, 14). Total vitamin D intake was calculated by summing vitamin D intake from foods and supplements. Dietary and total vitamin D intakes were adjusted for energy by using the residual method (15), because energy-adjusted values explained more variation in serum 25(OH)D concentrations than did crude values.

Region of residence and mean annual regional solar irradiance estimates

Participants were categorized into regional latitude categories corresponding to their WHI-CT clinic center latitude: northern (>40 °N), middle (>37 °N to 40 °N), and southern (≤37 °N) (16). Mean annual regional solar irradiance estimates in measures of Langleys [(g-cal) per cm2] (17) and Watts [(J/s) per m2] (18) were also assigned for each of the 40 WHI clinic centers, as previously described (16). No data were available on individually assessed sunlight exposure.

Additional potential predictor variables

The following variables were also considered as potential predictors of 25(OH)D concentrations based on previous evidence of their association with 25(OH)D concentrations: age (19), race-ethnicity (surrogate for skin pigmentation) (20–22), smoking status (23), estimates of body fatness (weight, body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio) (24–26), recreational physical activity (27, 28), and reported total time spent walking each week (surrogate for individually assessed sun exposure). However, location of walking (indoors compared with outdoors) was not assessed. We also investigated education as a measure of socioeconomic status. When possible, baseline data were used when missing year 1 data were not available for the following covariates: smoking status, recreational physical activity, weight, height, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio. Additional potential predictors of 25(OH)D concentrations included use of certain medications that could affect vitamin D concentrations or metabolism [steroids/corticosteroids, anticoagulants, anticonvulsants, antihypertensive medications, and osteoporosis-related (alendronate, salmon calcitonin, raloxifene, and etidronate)], as in a previous study (29). Hormone therapy use at year 1 (including assignment to the HT active arm) was also assessed as a predictor of 25(OH)D concentrations, because its use has been shown to increase circulating calcitriol concentrations (30, 31). Personal use of these medications was determined from a medication inventory taken at year 1.

Serum 25(OH)D assay

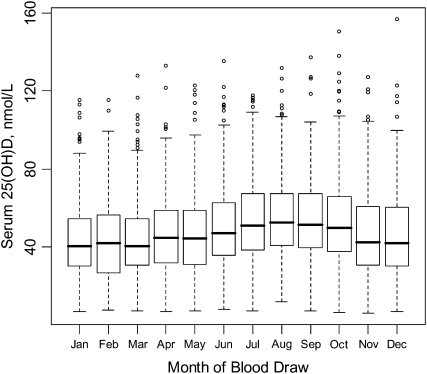

Serum drawn at the year 1 visit was processed and stored at −80°C, as previously described (10). Serum 25(OH)D concentrations (nmol/L) were measured by using the DiaSorin LIAISON chemiluminescence method (DiaSorin, Stillwater, MN), and the CV determined by using blinded controls was 11.8%. Serum 25(OH)D concentrations varied by month of blood draw, as expected (Figure 1); thus, month of blood draw was adjusted for in all statistical analyses.

FIGURE 1.

Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations, adjusted for month of blood draw, in participants of the nested case-control studies of the Women's Health Initiative Calcium plus Vitamin D Clinical Trial (n = 3055). The box plots for each month cover the interquartile range, the horizontal line represents the median, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme point that is ≤1.5 times the interquartile range.

Several thresholds for determining vitamin D status, based on 25(OH)D concentrations, were investigated because there is continued discussion about the concentrations that are considered sufficient: 25(OH)D concentrations <25 nmol/L are considered to be deficient and associated with osteomalacia in adults (reviewed in reference 32). The Institute of Medicine (33) suggests that, in the elderly, concentrations of ≥50 nmol/L are necessary for optimization of parathyroid hormone concentrations. Other investigators (34–37) consider values between ≥50 and <75 nmol/L to be insufficient, and that slightly higher cutoffs (≥75 or ≥80 nmol/L) define optimal concentrations for health. For this analysis, individuals were classified into the following categories: severely deficient (<25 nmol/L), moderately deficient (≥25 to <50 nmol/L), insufficient (≥50 to <75 nmol/L), and sufficient (≥75 nmol/L).

Statistical methods

The relation between actual measured serum 25(OH)D concentrations and potential predictive factors for 25(OH)D concentrations was investigated in a random two-thirds sample of our analysis sample (3055 of 4583). After identifying the best set of predictors, we used the remaining 1528 participants (one-third) to validate the predictive model. In the two-thirds sample, means and SEs of serum 25(OH)D concentrations, with and without adjustment for month of blood draw, were examined by using analysis of variance by noted potential predictors of 25(OH)D concentrations available in the WHI study (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Mean serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations by potential predictors of serum 25(OH)D status with and without adjustment for month of blood draw: sample from the nested case-control studies of the Women's Health Initiative Calcium plus Vitamin D Clinical Trial (n = 3055)1

| 25(OH)D Concentration |

|||

| Characteristic | No. of subjects | Unadjusted | Adjusted for month of blood draw2 |

| mmol/L | |||

| Serum 25(OH)D | |||

| Quintile 1: 6.3–30.2 nmol/L | 616 | 21.5 ± 0.243 | 21.5 ± 0.32 |

| Quintile 2: 30.4–40.6 nmol/L | 598 | 35.8 ± 0.12 | 35.9 ± 0.32 |

| Quintile 3: 40.9–51.4 nmol/L | 615 | 45.9 ± 0.12 | 45.9 ± 0.32 |

| Quintile 4: 51.6–66.8 nmol/L | 620 | 58.5 ± 0.18 | 58.5 ± 0.32 |

| Quintile 5: 67.1–156.6 nmol/L | 606 | 84.7 ± 0.63 | 84.7 ± 0.32 |

| P value4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Estimates of sunlight exposure | |||

| Regional estimate | |||

| Latitude of clinic center °N | |||

| Northern: >40 °N | 1473 | 48.7 ± 0.58 | 48.6 ± 0.59 |

| Middle: >37–40 °N | 651 | 49.0 ± 0.90 | 49.2 ± 0.88 |

| Southern: ≤37 °N | 931 | 50.3 ± 0.77 | 50.4 ± 0.74 |

| P value4 | 0.094 | 0.062 | |

| Langleys of clinical center | |||

| Quintile 1: 300–325 g-cal/cm2 | 936 | 49.0 ± 0.74 | 49.1 ± 0.73 |

| Quintile 2: 350 g-cal/cm2 | 726 | 48.8 ± 0.82 | 48.4 ± 0.84 |

| Quintile 3: 375–380 g-cal/cm2 | 304 | 47.9 ± 1.31 | 47.7 ± 1.29 |

| Quintile 4: 400–430 g-cal/cm2 | 507 | 46.6 ± 0.97 | 47.0 ± 1.00 |

| Quintile 5: 475–500 g-cal/cm2 | 582 | 53.3 ± 1.01 | 53.5 ± 0.93 |

| P value4 | 0.031 | 0.014 | |

| Watts of clinical center | |||

| Quintile 1: 0.4–0.5 (J/s)/m2 | 718 | 48.4 ± 0.85 | 48.3 ± 0.84 |

| Quintile 2: 0.7 (J/s)/m2 | 742 | 49.3 ± 0.80 | 49.0 ± 0.83 |

| Quintile 3: 1.0 (J/s)/m2 | 559 | 48.5 ± 0.96 | 48.5 ± 0.95 |

| Quintile 4: 1.4 (J/s)/m2 | 677 | 49.8 ± 0.90 | 50.2 ± 0.87 |

| Quintile 5: 1.5–1.9 (J/s)/m2 | 359 | 51.3 ± 1.28 | 51.3 ± 1.19 |

| P value4 | 0.073 | 0.026 | |

| Individual estimates | |||

| Total time spent walking each week5 | |||

| 0 h | 1031 | 46.8 ± 0.70 | 47.0 ± 0.70 |

| 0 to <1 h | 453 | 47.5 ± 1.08 | 47.5 ± 1.05 |

| ≥1 to <2 h | 539 | 50.3 ± 0.98 | 50.2 ± 0.96 |

| ≥2 h | 727 | 51.6 ± 0.83 | 51.5 ± 0.83 |

| P value4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Sources of vitamin D from diet and supplements | |||

| Vitamin D intake from foods, energy-adjusted5 | |||

| Quintile 1: 0.12–2.35 μg/d | 601 | 44.3 ± 0.96 | 44.5 ± 0.92 |

| Quintile 2: 2.36–3.23 μg/d | 565 | 48.5 ± 0.97 | 48.3 ± 0.94 |

| Quintile 3: 3.23–4.17 μg/d | 573 | 48.9 ± 0.91 | 49.0 ± 0.94 |

| Quintile 4: 4.18–5.69 μg/d | 576 | 52.3 ± 0.97 | 52.2 ± 0.93 |

| Quintile 5: 5.69–26.27 μg/d | 589 | 54.0 ± 0.91 | 53.9 ± 0.92 |

| P value4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Vitamin D intake from supplements5 | |||

| None | 1598 | 44.0 ± 0.55 | 43.9 ± 0.54 |

| ≤10 μg/d | 1124 | 53.7 ± 0.65 | 53.8 ± 0.65 |

| >10 μg/d | 291 | 61.0 ± 1.38 | 61.4 ± 1.28 |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Vitamin D intake from foods and supplements, energy-adjusted5 | |||

| Quintile 1: 0.09–3.10 μg/d | 596 | 40.9 ± 0.93 | 40.8 ± 0.90 |

| Quintile 2: 3.10–5.28 μg/d | 567 | 45.8 ± 0.93 | 45.8 ± 0.92 |

| Quintile 3: 5.29–10.40 μg/d | 569 | 50.1 ± 0.95 | 50.0 ± 0.92 |

| Quintile 4: 10.40–14.94 μg/d | 554 | 53.3 ± 0.88 | 53.5 ± 0.93 |

| Quintile 5: 14.96–78.77 μg/d | 579 | 58.1 ± 0.95 | 58.2 ± 0.91 |

| P value4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Potential modifiers of vitamin D synthesis from sunlight exposure | |||

| Age at baseline screening | |||

| 50–54 y | 268 | 48.9 ± 1.53 | 48.7 ± 1.38 |

| 55–59 y | 555 | 50.2 ± 0.96 | 49.9 ± 0.96 |

| 60–64 y | 632 | 49.9 ± 0.91 | 49.8 ± 0.90 |

| 65–69 y | 740 | 49.9 ± 0.84 | 50.0 ± 0.83 |

| 70–74 y | 577 | 49.1 ± 0.92 | 49.3 ± 0.94 |

| 75–79 y | 283 | 45.1 ± 1.37 | 45.3 ± 1.34 |

| P value4 | 0.051 | 0.114 | |

| Race-ethnicity | |||

| White | 2726 | 50.4 ± 0.44 | 50.4 ± 0.43 |

| African American | 164 | 34.8 ± 1.32 | 35.1 ± 1.74 |

| Hispanic | 76 | 41.2 ± 2.47 | 40.1 ± 2.56 |

| American Indian | 11 | 42.0 ± 6.92 | 41.3 ± 6.71 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 51 | 47.9 ± 3.35 | 49.0 ± 3.12 |

| Unknown | 27 | 49.9 ± 4.85 | 50.4 ± 4.28 |

| P value4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Anthropometric characteristics that may modify vitamin D status | |||

| Weight | |||

| Quintile 1: 41.2–61.8 kg | 610 | 57.1 ± 1.04 | 56.9 ± 0.89 |

| Quintile 2: 61.9–68.8 kg | 612 | 52.0 ± 0.90 | 51.9 ± 0.89 |

| Quintile 3: 68.9–76.4 kg | 608 | 47.9 ± 0.90 | 48.4 ± 0.90 |

| Quintile 4: 76.5–86.0 kg | 616 | 46.2 ± 0.84 | 46.0 ± 0.89 |

| Quintile 5: 86.1–190.0 kg | 609 | 43.2 ± 0.82 | 43.2 ± 0.89 |

| P value4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Waist circumference5 | |||

| Quintile 1: 56.4–76.4 cm | 604 | 58.4 ± 1.01 | 58.2 ± 0.89 |

| Quintile 2: 76.5–83.5 cm | 617 | 51.8 ± 0.94 | 51.9 ± 0.88 |

| Quintile 3: 83.6–90.2 cm | 604 | 47.0 ± 0.90 | 47.1 ± 0.89 |

| Quintile 4: 90.5–99.5 cm | 623 | 46.2 ± 0.83 | 46.3 ± 0.88 |

| Quintile 5: 99.8–158.9 cm | 606 | 43.0 ± 0.81 | 42.9 ± 0.89 |

| P value4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Waist-to-hip ratio5 | |||

| Quintile 1: 0.43–0.76 | 610 | 54.8 ± 0.97 | 54.8 ± 0.91 |

| Quintile 2: 0.76–0.80 | 610 | 51.2 ± 0.95 | 51.3 ± 0.90 |

| Quintile 3: 0.80–0.83 | 612 | 48.1 ± 0.88 | 48.0 ± 0.90 |

| Quintile 4: 0.83–0.88 | 611 | 46.4 ± 0.91 | 46.4 ± 0.90 |

| Quintile 5: 0.88–2.58 | 611 | 45.9 ± 0.87 | 45.9 ± 0.90 |

| P value4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| BMI5 | |||

| Quintile 1: 15.8–23.8 kg/m2 | 609 | 58.0 ± 1.04 | 58.1 ± 0.89 |

| Quintile 2: 23.8–26.3 kg/m2 | 610 | 52.8 ± 0.88 | 52.5 ± 0.89 |

| Quintile 3: 26.4–29.1 kg/m2 | 610 | 47.2 ± 0.92 | 47.5 ± 0.89 |

| Quintile 4: 29.1–32.7 kg/m2 | 610 | 45.5 ± 0.84 | 45.6 ± 0.89 |

| Quintile 5: 32.7–69.3 kg/m2 | 610 | 42.8 ± 0.80 | 42.7 ± 0.89 |

| P value4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Other health and lifestyle characteristics | |||

| Education5 | |||

| 0–8 y | 25 | 42.4 ± 4.24 | 42.7 ± 4.50 |

| Some high school | 117 | 43.6 ± 2.01 | 43.0 ± 2.08 |

| High school diploma/GED | 599 | 49.8 ± 0.99 | 49.7 ± 0.92 |

| School after high school | 1182 | 48.6 ± 0.66 | 48.8 ± 0.66 |

| College degree or higher | 1116 | 50.5 ± 0.68 | 50.4 ± 0.67 |

| P value4 | 0.011 | 0.008 | |

| Recreational physical activity5 | |||

| Quintile 1: 0–0.5 MET-h/wk | 532 | 44.3 ± 0.90 | 44.6 ± 0.96 |

| Quintile 2: 0.75–4.50 MET-h/wk | 578 | 45.5 ± 0.91 | 45.5 ± 0.92 |

| Quintile 3: 4.54–9.50 MET-h/wk | 528 | 49.6 ± 0.99 | 49.2 ± 0.96 |

| Quintile 4: 9.58–17.42 MET-h/wk | 541 | 50.0 ± 0.98 | 50.1 ± 0.95 |

| Quintile 5: 17.50–113.17 MET-h/wk | 552 | 55.9 ± 1.00 | 55.8 ± 0.94 |

| P value4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Smoking status5 | |||

| Never smoked | 1584 | 49.1 ± 0.56 | 49.0 ± 0.57 |

| Past smoker | 1213 | 50.2 ± 0.66 | 50.2 ± 0.65 |

| Current smoker | 222 | 46.6 ± 1.70 | 46.5 ± 1.51 |

| P value4 | 0.074 | 0.058 | |

| History of osteoporosis56 | |||

| No | 2773 | 49.3 ± 0.43 | 49.3 ± 0.43 |

| Yes | 231 | 49.6 ± 1.56 | 49.5 ± 1.49 |

| P value4 | 0.850 | 0.923 | |

| History of diabetes56 | |||

| No | 2905 | 49.7 ± 0.43 | 49.7 ± 0.42 |

| Yes | 148 | 41.8 ± 1.61 | 41.5 ± 1.85 |

| P value4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Medication use7 | |||

| Hormone therapy use | |||

| None | 1047 | 47.0 ± 0.67 | 47.0 ± 0.69 |

| Past | 469 | 49.0 ± 1.09 | 49.1 ± 1.04 |

| Current estrogen alone | 699 | 49.9 ± 0.88 | 49.9 ± 0.85 |

| Current estrogen + progesterone | 840 | 51.7 ± 0.80 | 51.7 ± 0.78 |

| P value4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Osteoporosis-related medication use8 | |||

| No | 2992 | 49.1 ± 0.42 | 49.2 ± 0.41 |

| Yes | 63 | 55.2 ± 2.98 | 55.1 ± 2.84 |

| P value4 | 0.038 | 0.038 | |

| Antihypertensive medication use | |||

| No | 2680 | 49.8 ± 0.44 | 49.7 ± 0.43 |

| Yes | 375 | 45.8 ± 1.16 | 45.9 ± 1.16 |

| P value4 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |

Quintile ranges appear to overlap because differences in values between quintiles occur at the third decimal place and are not shown in this table. MET-h, metabolic equivalent task hours; GED, general equivalent diploma.

To adjust for month of blood draw, serum 25(OH)D concentrations were regressed on month of blood draw to compute residuals, which were added back to the mean serum 25(OH)D concentration in the sample.

Mean ± SE (all such values).

P values were derived from generalized linear models to estimate least-squares means of serum 25(OH)D, adjusted for month of blood draw, by level of noted characteristic.

Total n does not add up to 3055 because of missing data.

Reported at baseline or during follow-up but before year 1 blood draw.

No statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) by concentration of 25(OH)D were observed for use of the following medications: anticonvulsants, hematopoietic agents, anticoagulants, steroids/corticosteroids, antihyperlipidemic agents, or statins (data not shown).

Reported osteoporosis-related medications were alendronate, salmon calcitonin, raloxifene, and etidronate.

The percentage agreement between individuals ranked by measured serum 25(OH)D concentrations and those ranked by surrogate measures for vitamin D status (latitude, regional solar irradiance estimates, and oral intake of vitamin D) was investigated. Tertiles of 25(OH)D were cross-classified by region of residence (southern, middle, and northern) with tertile 1 having the lowest 25(OH)D concentrations. Quintiles of 25(OH)D were cross-classified by quintiles of mean annual regional solar irradiance estimates and quintiles of total vitamin D, with quintile 1 indicating low 25(OH)D concentrations, low solar irradiance, or low vitamin D intake. A weighted κ statistic, using the Cicchetti-Allison method for computing weights, was computed to compare the agreement (beyond chance) between quantiles of 25(OH)D and the surrogate measures for vitamin D status (38).

Linear regression models were used to examine how well individual factors predicted serum 25(OH)D concentrations. Continuous variables were used, with transformations when distributions were skewed, except for the following categorical variables: race-ethnicity, education, history of diabetes, use of hormone therapy at year 1, and use of osteoporosis-related medications. Total energy-adjusted vitamin D was modeled by using the log base 2 transformed variable, and a quadratic term was added for age (age × age). Stepwise linear regression was implemented to develop the most predictive multivariate model for serum 25(OH)D concentrations (inclusion criteria <0.10 and exclusion criteria >0.05), while adjusting for month of blood draw, breast cancer status (yes, no), colorectal cancer status (yes, no), fracture status (yes, no), participation in the hormone therapy trial (yes, no), and randomization to the dietary modification trial [no, yes (on dietary modification), yes (not on dietary modification)]. Cases were not excluded from the model because samples were taken before case diagnosis as part of the prospective design of the study; therefore, factors associated with the outcome (treatment, change in habits) were unlikely to affect the findings.

The potential predictor variables considered in the building of the predictive model with serum 25(OH)D included the following: Langleys, time spent walking each week, total vitamin D intake, race-ethnicity, waist circumference, education, recreational physical activity, history of diabetes, and use of hormone therapy, antihypertensive, or osteoporosis medications. Age, although not statistically associated with 25(OH)D concentrations in this sample, was still considered because it is a known determinant of 25(OH)D concentrations (19). Some of the potential predictors for 25(OH)D were selected, rather than other variables that measured similar aspects, based on their ability to explain variation in serum vitamin D concentrations (data not shown). For vitamin consumption, the total vitamin D intake provided a higher R2 value than did vitamin D intake from foods or supplements separately. Similarly, waist circumference was chosen as a measure of adiposity instead of body weight, body mass index, or waist-to-hip ratio, and Langleys was used instead of latitude or Watts.

The predictive model was validated by using the remaining one-third (n = 1528) of the 4583 sample by using the β coefficients from the predictive model and individual values in the validation subsample (n = 1528). The predicted 25(OH)D concentrations were compared with the actual measured 25(OH)D concentrations in these participants. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to assess agreement between predicted and actual levels. The ability of the predicted model to classify individuals as severely deficient, moderately deficient, insufficient, or sufficient compared with their actual classification was examined.

RESULTS

The distribution of serum 25(OH)D concentrations in 3055 participants in the two-thirds random sample, ranging from 6.3 to 156.6 nmol/L, varied by month (highest in August and lowest in March) (Figure 1). Seasonal variation was more pronounced at northern and middle, rather than southern, latitudes (data not shown). Of the 3055 participants, 13.5% were severely vitamin D deficient (<25 nmol/L), 43.6% were moderately deficient (≥25 to <50 nmol/L), 29.9% were insufficient (≥50 to <75 nmol/L), and 13.0% were sufficient (≥75 nmol/L).

Serum 25(OH)D concentrations increased with increasing regional solar irradiance estimates, total time spent walking each week, oral intake of vitamin D, education, and recreational physical activity (Table 1). Serum 25(OH)D concentrations were higher in white women of unknown racial ethnic groups, women ever using hormone therapy (either past or current), and individuals who used osteoporosis medications. Serum 25(OH)D concentrations were lower with increasing weight, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and body mass index. Concentrations were also lower in women with a history of diabetes and who used antihypertensive medications. There were no statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) in 25(OH)D concentrations by latitude of clinic center, age (although the oldest group, 75–59 y, had the lowest concentrations), and history of osteoporosis.

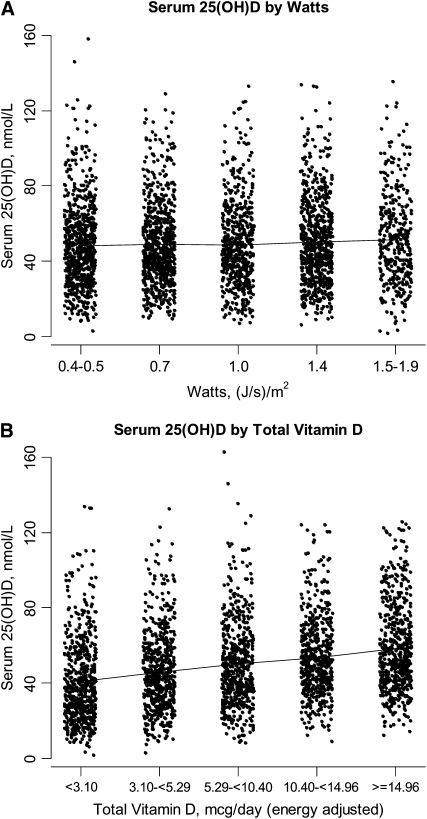

Because epidemiologic studies often compare risk of disease between individuals in high compared with low quantiles (tertiles, quartiles, quintiles, etc) of vitamin D exposure, we investigated how well rankings of surrogate measures of vitamin D (latitude, regional solar irradiance, and oral intake of vitamin D) and 25(OH)D concentrations agree (Table 2). Of women in the lowest tertile for 25(OH)D, <50% were living at a northern latitude. Of women in the highest tertile for 25(OH)D, only 32% were living at a southern latitude, <50% of women in the lowest quintile for 25(OH)D were classified into the lowest quintile for regional solar irradiance or total vitamin D intake, and an even smaller percentage (<30%) of women in the highest quintile for 25(OH)D were also classified into the highest quintile for these surrogate measures. Region of residence and regional solar irradiance estimates were better at classifying women with low rather than high 25(OH)D concentrations. However, distributions of 25(OH)D concentrations among women within each quantile of surrogate measures of vitamin D overlap considerably, as illustrated in Figure 2, A and D. The best agreement was for vitamin D intake from foods and supplements combined (weighted κ = 0.19).

TABLE 2.

Percentages of persons in the lowest and highest quantile for serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], who were classified into specific latitude regions or quintiles of surrogate markers for vitamin D exposure: sample from the nested case-control studies of the Women's Health Initiative Calcium plus Vitamin D Clinical Trial at enrollment (n = 3055)1

| Agreement | Subjects2 | |

| n (%) | ||

| Latitude of clinic center3 | ||

| Lowest tertile of serum 25(OH)D (n = 1018) | ||

| Northern (>40°N) | Good | 498 (48.9) |

| Northern and Middle (>37°N) | Moderate | 720 (70.7) |

| Southern (≤37°N) | Poor | 298 (29.3) |

| Highest tertile of serum 25(OH)D (n = 1018) | ||

| Southern (≤37°N) | Good | 326 (32.0) |

| Southern and Middle (≤40°N) | Moderate | 548 (53.8) |

| Northern (>40°N) | Poor | 470 (46.2) |

| Langleys [(g-cal)/cm2]3 | ||

| Lowest quintile of serum 25(OH)D (n = 611) | ||

| Lowest quintile (300–325) | Good | 179 (29.3) |

| Lowest 2 quintiles (300–350) | Moderate | 327 (53.5) |

| Highest quintile (475–500) | Poor | 95 (15.6) |

| Highest quintile of serum 25(OH)D (n = 611) | ||

| Highest quintile (475–500) | Good | 152 (24.9) |

| Highest 2 quintiles (400–500) | Moderate | 244 (39.9) |

| Lowest quintile (300–325) | Poor | 184 (30.1) |

| Watts [(J/s)/m2]4 | ||

| Lowest quintile of serum 25(OH)D (n = 611) | ||

| Lowest quintile (0.4–0.5) | Good | 158 (25.9) |

| Lowest 2 quintiles (0.4–0.7) | Moderate | 287 (47.0) |

| Highest quintile (1.5–1.9) | Poor | 70 (11.5) |

| Highest quintile of serum 25(OH)D (n = 611) | ||

| Highest quintile (1.5–1.9) | Good | 84 (13.8) |

| Highest 2 quintiles (1.4–1.9) | Moderate | 236 (38.6) |

| Lowest quintile (0.4–0.5) | Poor | 129 (21.1) |

| Total vitamin D, energy-adjusted (μg/d)5 | ||

| Lowest quintile of serum 25(OH)D (n = 566)6 | ||

| Lowest quintile (0.09–3.10) | Good | 229 (40.5) |

| Lowest 2 quintiles (0.09–5.28) | Moderate | 364 (64.3) |

| Highest quintile (14.96–78.77) | Poor | 40 (7.1) |

| Highest quintile of serum 25(OH)D (n = 585)6 | ||

| Highest quintile (14.96–78.77) | Good | 174 (29.7) |

| Highest 2 quintile (>10.40–78.77) | Moderate | 301 (51.5) |

| Lowest quintile (0.09–3.10) | Poor | 76 (13.0) |

Serum vitamin D was adjusted for month of blood draw by regressing 25(OH)D on month of blood draw to compute residuals and adding the residuals to the mean serum 25(OH)D concentration in the sample. A weighted κ statistic, obtained by using the Cicchetti-Allison method for computing weights, was computed to compare the agreement (beyond chance) between quantiles of 25(OH)D and the surrogate measures for vitamin D status (38).

Percentage equals n/total n.

Weighted κ = 0.02

Weighted κ = 0.03

Weighted κ = 0.19

Of 3055 participants, 190 were missing data on total vitamin D intake.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations, adjusted for month of blood draw, at year 1 of the Women's Health Initiative nested case-control studies of the Calcium plus Vitamin D Clinical Trial by Watt quintile of clinic center (A) and quintile of energy-adjusted total vitamin D intake (B). n = 3055. Panel B contains a sample of 2865 women, because 190 women were missing data on total vitamin D intake. The lines connect the mean serum 25(OH)D concentrations by Watt quintiles (quintile 1 = 48.3, quintile 2 = 49.0, quintile 3 = 48.5, quintile 4 = 50.2, quintile 5 = 51.3) in panel A and by total vitamin D quintiles (quintile 1 = 40.8, quintile 2 = 45.8, quintile 3 = 50.1, quintile 4 = 53.5, quintile 5 = 58.2) in panel B. To control for month of blood draw, serum 25(OH)D concentrations were regressed on month of blood draw to compute residuals, which were added back to the mean serum 25(OH)D concentration in the sample.

The predictive model for serum 25(OH)D explained only 21% of the overall variance in 25(OH)D (Table 3). Total vitamin D intake from foods and supplements explained 7% of the variance in 25(OH)D concentrations between participants. In this sample, a doubling of vitamin D intake (eg, 100–200 IU) is estimated to result in a 25(OH)D increase of 5.28 nmol/L. Other predictor variables that accounted for a large amount of variation in 25(OH)D concentrations in the overall model were waist circumference (5%) and month of blood draw (3%). Although significant predictors, physical activity, race-ethnicity, Langleys, and age together only accounted for an additional 4% variance in 25(OH)D. Predictors remained the same when the analyses were limited to controls and after exclusion of diagnosed cases (breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and hip fracture) within the first 2 y of the WHI-CT; the predictive model explained 26% and 22% of the variation in 25(OH)D, respectively. In both models, total vitamin D intake explained most of this variation, followed by waist circumference (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Predictors of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D]: sample from the nested case-control studies of the Women's Health Initiative Calcium plus Vitamin D Clinical Trial (n = 3055)1

| Reduced model2 |

Final 25(OH)D predictive model3 |

|||||||

| No. of subjects | β-coefficient (SE) | P value | Model R2 | β-coefficient (SE) | P value | Partial R2 | Model R2 | |

| Independent variable | ||||||||

| Month of blood draw | 0.05 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.05 | ||||

| January | 260 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| February | 226 | 0.02 (2.04) | 0.99 | 0.26 (1.96) | ||||

| March | 244 | 0.99 (2.00) | 0.62 | 1.93 (1.93) | ||||

| April | 280 | 3.16 (1.93) | 0.10 | 2.52 (1.89) | ||||

| May | 230 | 3.77 (2.03) | 0.06 | 2.32 (2.05) | ||||

| June | 300 | 6.86 (1.90) | 0.0003 | 7.60 (1.87) | ||||

| July | 281 | 10.05 (1.93) | <0.0001 | 10.37 (1.90) | ||||

| August | 248 | 11.35 (1.99) | <0.0001 | 12.15 (2.02) | ||||

| September | 242 | 9.95 (2.00) | <0.0001 | 10.27 (2.07) | ||||

| October | 276 | 10.20 (1.94) | <0.0001 | 10.23 (1.94) | ||||

| November | 234 | 3.97 (2.02) | 0.05 | 4.68 (1.99) | ||||

| December | 234 | 4.46 (2.02) | 0.03 | 5.22 (1.96) | ||||

| Total vitamin D intake, energy-adjusted (μg/d)4,5 | 2865 | 5.28 (0.34) | <0.0001 | 0.12 | 5.05 (0.34) | <0.0001 | 0.07 | 0.12 |

| Waist circumference (cm)4 | 3054 | −0.40 (0.03) | <0.0001 | 0.10 | −0.36 (0.03) | <0.0001 | 0.05 | 0.17 |

| Recreational physical activity (MET-h/wk)4 | 2731 | 0.32 (0.03) | <0.0001 | 0.07 | 0.21 (0.03) | <0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.19 |

| Race-ethnicity | 0.07 | <0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.20 | ||||

| White | 2726 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| African American | 164 | −15.44 (1.79) | <0.0001 | −11.37 (1.92) | ||||

| Hispanic | 76 | −10.31 (2.58) | <0.0001 | −9.22 (2.70) | ||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 51 | −1.50 (3.13) | 0.63 | −8.07 (3.14) | ||||

| American Indian/unknown | 38 | −1.96 (3.62) | 0.59 | −2.68 (3.56) | ||||

| Langleys [(g-cal) per cm2] | 3055 | 0.02 (0.007) | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.04 (0.007) | <0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.21 |

| Age (y) | 3055 | 2.75 (0.98) | 0.005 | 2.59 (1.00) | 0.01 | |||

| Age × age (y)6 | 3055 | −0.02 (0.008) | 0.004 | 0.05 | −0.02 (0.008) | 0.01 | 0.007 | 0.21 |

| Education4 | 0.05 | —7 | ||||||

| ≤High school | 741 | Reference | Reference | |||||

| School after high school | 1182 | 0.25 (1.05) | 0.81 | |||||

| College degree or higher | 1116 | 1.54 (1.07) | 0.15 | |||||

| Total time spent walking each week (h)4 | 2750 | 0.02 (0.005) | <0.0001 | 0.05 | —7 | |||

| History of diabetes5 | 3053 | 0.05 | —7 | |||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | −7.73 (1.89) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Use of hormone therapy at year 1, including randomization | 0.05 | —7 | ||||||

| None | 1047 | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Past use | 469 | 2.18 (1.24) | 0.08 | |||||

| Current estrogen alone use | 699 | 2.10 (1.10) | 0.06 | |||||

| Current estrogen plus progesterone use | 840 | 4.49 (1.05) | <0.0001 | |||||

| Osteoporosis-related medication use8 | 0.04 | 0.05 | —7 | |||||

| No | 2992 | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 63 | 5.98 (2.86) | ||||||

| Use of antihypertensive medications | 0.003 | 0.05 | —7 | |||||

| No | 2680 | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 375 | −3.69 (1.23) | ||||||

| Fully adjusted model R2 | 0.21 | |||||||

The predictive model was built by using a sample size of 3055 participants, but only 2472 were included in the final model because of missing data. MET-h, metabolic equivalent task hours.

Stepwise linear regression was implemented to develop the most predictive multivariate model for serum 25(OH)D concentrations (inclusion criteria <0.10 and exclusion criteria >0.05). The reduced model was adjusted for month of blood draw, breast cancer status (yes, no), colorectal cancer status (yes, no), fracture status (yes, no), participation in the hormone therapy trial (yes, no), and randomization to the dietary modification trial [no, yes (on dietary modification), and yes (not on dietary modification)].

The final predictive model, developed with stepwise linear regression, for 25(OH)D was adjusted for all covariates in the reduced model plus adjustment for determined predictors of vitamin D status (age, race-ethnicity, Langleys, waist circumference, recreational physical activity, and total vitamin D intake).

Total n does not add up to 3055 because of missing data.

Total energy-adjusted vitamin D was modeled by using the log base 2 transformed variable.

Age is a quadratic term, age × age.

Variables determined to not be significant predictors of serum 25(OH)D status.

Reported osteoporosis medications were alendronate, salmon calcitonin, raloxifene, and etidronate.

In the validation subsample, deciles were created by using the predicted 25(OH)D concentrations. Actual mean 25(OH)D concentrations increased with increasing deciles of predicted 25(OH)D concentrations. The difference in mean predicted 25(OH)D concentrations among women in predicted decile 10 compared with decile 1 was 36.9 nmol/L, and the difference in mean actual 25(OH)D concentrations among women in predicted decile 10 compared with decile 1 was 34.9 nmol/L. This showed discrimination of a similar range of 25(OH)D concentrations with the use of the predicted model as the actual concentrations. To test the validity of the predicted model, we calculated the correlation between actual and predicted values (Pearson correlation: 0.45; 95% CI: 0.40, 0.49).

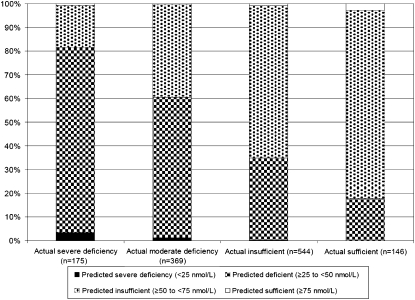

How well the predictive model distinguished between severely deficient, moderately deficient, insufficient, and sufficient 25(OH)D concentrations on an individual basis is shown in Figure 3. Of the 146 women with severe deficiency, only 3% were similarly categorized by the predictive model. Of the 544 women who were moderately deficient, 59% were similarly categorized by the predictive model. Of the women determined to be insufficient (n = 369) and sufficient (n = 175), 64% and 3%, respectively, were similarly categorized with the predictive model.

FIGURE 3.

Percentage of participants categorized as severely vitamin D deficient, moderately deficient, insufficient, and sufficient based on a model used to predict serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations by actual 25(OH)D concentration. Analyses were conducted in a validation sample (n = 1234) of participants in the nested case-control studies of the Women's Health Initiative Calcium plus Vitamin D Clinical Trial.

DISCUSSION

Using data from the WHI CaD clinical trial, we estimated that >50% of a sample of US postmenopausal women were deficient in vitamin D (<50 nmol/L), and 13% were severely deficient (<25 nmol/L). These estimates are slightly higher than estimates obtained from a nationally representative sample, the 1988–1994 third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), in which 29–37% of women aged ≥60 y had serum 25(OH)D concentrations <50 nmol/L (39). However, the vitamin D assay used in NHANES III is reported to have underestimated 25(OH)D concentrations (40). At the same time, the estimate of vitamin D deficiency among WHI participants is within the reported range of vitamin D deficiency among postmenopausal women (reviewed in reference 41). Slight differences in estimates between discrete study samples may be explained by measurement error between different vitamin D assays used (42) and the lack of a standard reference for 25(OH)D concentrations for calibration between laboratories (43).

In our study, surrogate makers of vitamin D status (latitude of residence, mean annual regional solar irradiance estimates, and oral sources) did not correlate strongly with individually assessed serum 25(OH)D concentrations. On average, correlations were in the directions expected; higher concentrations of 25(OH)D correlated with increasing oral intake, regional solar irradiance estimates, and decreasing latitude. We found that these surrogate measures misclassified individuals according to measured 25(OH)D concentrations, with greater misclassification at higher than at lower 25(OH)D concentrations. Thus, the observed relations between cancer outcomes and latitude or regional solar irradiance (1) could be explained by other cancer risk factors that may vary with latitude. It seems likely that, because individuals are increasingly practicing sun avoidance behaviors to prevent skin cancer, location and mean annual solar irradiance estimates of residence may no longer correlate with vitamin D status. This weak correlation between latitude or regional solar irradiance estimates and vitamin D status, assessed with 25(OH)D concentrations, may be one reason why analyses in the WHI did not find an association between breast cancer incidence and latitude or solar irradiance (16).

Despite the WHI's extensive data on potential predictors of 25(OH)D concentrations, our predictive model could explain only 21% of the variation in 25(OH)D after adjustment for clinical trial factors, month of blood draw, estimates of total vitamin D intake from foods and supplements, waist circumference, recreational physical activity, race-ethnicity, mean annual regional solar irradiance, and age. We also found that the predictive model was poor at categorizing women in the extreme (severely deficient and sufficient) ranges of vitamin D status assessed with 25(OH)D concentrations. Of the predictive factors identified, vitamin D intake from diet and supplements accounted for the greatest amount of explainable variation. Although our sample contained women from a wide range of latitudes, mean annual solar irradiance only accounted for a minimal amount (1%) of variation in 25(OH)D. This is consistent with some (27, 44–46), but not all (47), previous studies that incorporated samples from a range of latitudes, which indicated that latitude was not a strong determinant of 25(OH)D concentrations.

Other studies, which focused on aging women, had results similar to ours. Previous studies have explained from 19% to 39% of the variance in blood 25(OH)D concentrations and have reported the following factors as significantly explaining variation in blood 25(OH)D concentrations: measures of sun exposure (48–52), month of blood draw or season (50, 53), supplement use (48, 51, 52, 54), dietary intake of vitamin D (48, 51) or calcium (49), age (48, 49, 53, 54), anthropometric measures (51–54), and physical activity (53). Our results, which showed that we could explain only 21% of the variance in 25(OH)D, suggest that individual sun-related behaviors (not assessed in this study), genetic differences, or other unmeasured variables not yet known account for the remaining variance (79%). Although our study did not have a measure of individually assessed sun exposure, report of recreational physical activity could have captured some of this measure. In previous studies (48–52, 55–57) that considered individually assessed measures of sun exposure in predictive models, the maximum reported explainable variation in 25(OH)D blood concentrations was 39% (51). It appears that either observational studies have not been able to adequately capture individual sun exposure or other factors unaccounted for, such as genetics, play a significant role in determining serum 25(OH)D concentrations. Although studies have investigated vitamin D status related to genetic variants of vitamin D–metabolizing genes (58), no study, to our knowledge, has incorporated genetic variants of vitamin D–metabolizing genes, along with other predictors, into 25(OH)D predictive models. Additionally, errors in the measurement of predictor variables likely reduce the percentage of explainable variance.

Other than a cohort study in male health professionals (27), to our knowledge, this is the only other article to report validating a predictive model of 25(OH)D status and the only study to do so in women. Giovannucci et al (27), using data from the Health Professionals Follow-Up cohort, found that a predictive model including geographic region of residence, skin pigmentation, dietary intake, supplement intake, BMI, and leisure-time physical activity accounted for 28% of the variation in serum 25(OH)D in men. Validation of our model showed that correlations between predicted and actual serum 25(OH)D concentrations were modest (Pearson correlation: 0.45; 95% CI: 0.40, 0.49). Giovannucci et al (27) did not present a correlation between their predicted and actual 25(OH)D concentrations, but they showed that predicted 25(OH)D concentrations were associated with a decreased risk of overall cancer incidence and mortality. They suggested that their predictive model may better estimate long-term, rather than short-term, vitamin D status (27) and that long-term rather than short-term status is more likely to be a stronger risk factor for disease outcomes. Currently, no one has investigated how well a predictive model relates to multiple measures of 25(OH)D concentrations over time. It is possible that a predictive model reflects more of an overall healthy lifestyle score than an accurate vitamin D status (either short- or long-term).

Our study was limited by a lack of data on individually assessed sun exposure, known to be a major determinant of vitamin D status. But, as previously shown (48–52, 55–57), data on this measure may not have greatly improved the predictability of our model. It is also possible that more detailed data on such determinants as body fatness (as obtained with a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scan), and skin pigmentation (as obtained with a reflectometer), would have increased the explainable variance in 25(OH)D concentrations. We had only one measure of serum vitamin D, and it is unclear how these concentrations may vary within individuals over time or if one-time measure of 25(OH)D concentrations reflects long-term vitamin D exposure. Additionally, the WHI consisted of volunteers with somewhat greater than average educational attainment, whose characteristics and health-related behaviors may not generalize to the US population or other cultures.

Our study in the WHI CaD clinical trial illustrated that surrogate markers of vitamin D status, although somewhat correlated with 25(OH)D concentrations, do not adequately reflect serum 25(OH)D concentrations, and a predictive model of vitamin D status explains a minimal amount of variation in 25(OH) concentrations. For this reason, surrogates measures of vitamin D status that are intended to reflect oral sources and/or skin synthesis, and predictive models of blood 25(OH)D concentrations, should be used with caution in making assumptions about the relation between vitamin D status and health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The WHI Investigators are listed as follows: Program Office: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD (Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller). Clinical Coordinating Center: Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA (Ross Prentice, Garnet Anderson, Andrea LaCroix, and Charles L Kooperberg); Medical Research Laboratories, Highland Heights, KY (Evan Stein); and the University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA (Steven Cummings). Clinical Centers: Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY (Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller); Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Haleh Sangi-Haghpeykar); Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA (JoAnn E Manson); Brown University, Providence, RI (Charles B Eaton); Emory University, Atlanta, GA (Lawrence S Phillips); Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA (Shirley Beresford); George Washington University Medical Center, Washington, DC (Lisa Martin); Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor–UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA (Rowan Chlebowski); Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland, OR (Erin LeBlanc); Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, CA (Bette Caan); Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI (Jane Morley Kotchen); MedStar Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC (Barbara V Howard); Northwestern University, Chicago/Evanston, IL (Linda Van Horn); Rush Medical Center, Chicago, IL (Henry Black); Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA (Marcia L Stefanick); State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY (Dorothy Lane); The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH (Rebecca Jackson); University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL (Cora E Lewis); University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, AZ (Cynthia A Thomson); University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY (Jean Wactawski-Wende); University of California at Davis, Sacramento, CA (John Robbins); University of California at Irvine, Irvine, CA (F Allan Hubbell); University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA (Lauren Nathan); University of California at San Diego, La Jolla/Chula Vista, CA (Robert D Langer); University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH (Margery Gass); University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL (Marian Limacher); University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI (J David Curb); University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, IA (Robert Wallace); University of Massachusetts/Fallon Clinic, Worcester, MA (Judith Ockene); University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, NJ (Norman Lasser); University of Miami, Miami, FL (Mary Jo O'Sullivan); University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN (Karen Margolis); University of Nevada, Reno, NV (Robert Brunner); University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC (Gerardo Heiss); University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA (Lewis Kuller); University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN (Karen C Johnson); University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX (Robert Brzyski); University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI (Gloria E Sarto); Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC (Mara Vitolins); Wayne State University School of Medicine/Hutzel Hospital, Detroit, MI (Michael S Simon). Women's Health Initiative Memory Study: Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC (Sally Shumaker).

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—AEM: designed the study, directed the analyses, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript; JW-W: designed the study and contributed to the interpretation of the results and manuscript writing; MP: contributed to the design of the study, conducted all data analyses, and contributed to the interpretation of the results and manuscript writing; and MLM, FAT, SL, RDJ, AZL, MSL, and RDJ: contributed to the design of the study, interpretation of the results, and manuscript writing. None of the authors reported a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grant WB, Mohr SB. Ecological studies of ultraviolet B, vitamin D and cancer since 2000. Ann Epidemiol 2009;19:446–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollis BW, Wagner CL, Drezner MK, Binkley NC. Circulating vitamin D3 and 25-hydroxyvitamin D in humans: an important tool to define adequate nutritional vitamin D status. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2007;103:631–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giovannucci E. The epidemiology of vitamin D and cancer incidence and mortality: a review (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2005;16:83–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertone-Johnson ER. Vitamin D and breast cancer. Ann Epidemiol 2009;19:462–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giovannucci E. Strengths and limitations of current epidemiologic studies: vitamin D as a modifier of colon and prostate cancer risk. Nutr Rev 2007;65:S77–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stefanick ML, Cochrane BB, Hsia J, Barad DH, Liu JH, Johnson SR. The Women's Health Initiative postmenopausal hormone trials: overview and baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol 2003;13:S78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritenbaugh C, Patterson RE, Chlebowski RT, et al. The Women's Health Initiative Dietary Modification trial: overview and baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol 2003;13:S87–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Cauley JA, McGowan J. The Women's Health Initiative calcium-vitamin D trial: overview and baseline characteristics of participants. Ann Epidemiol 2003;13:S98–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med 2006;354:669–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wactawski-Wende J, Kotchen JM, Anderson GL, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;354:684–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chlebowski RT, Johnson KC, Kooperberg C, et al. Calcium plus vitamin Dsupplementation and the risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:1581–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Tinker LF, Carter RA, Bolton MP, Agurs-Collins T. Measurement characteristics of the Women's Health Initiative food frequency questionnaire. Ann Epidemiol 1999;9:178–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Levy L, McLerran D, White E. Validity of methods used to assess vitamin and mineral supplement use. Am J Epidemiol 1998;148:643–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patterson RE, Levy L, Tinker LF, Kristal AR. Evaluation of a simplified vitamin supplement inventory developed for the Women's Health Initiative. Public Health Nutr 1999;2:273–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willett WC, Howe GR, Kushi LH. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65(suppl):1220S–8S; discussion 1229S–31S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millen AE, Pettinger M, Freudenheim JL, et al. Incident invasive breast cancer, geographic location of residence, and reported average time spent outside. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:495–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garland CF, Garland FC. Do sunlight and vitamin D reduce the likelihood of colon cancer? Int J Epidemiol 1980;9:227–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lubin D, Jensen EH, Gies HP. Global surface ultraviolet radiation climatology from TOMS and ERBE data. J Geophys Res 1998;103(D20):26061–91 [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacLaughlin J, Holick MF. Aging decreases the capacity of human skin to produce vitamin D3. J Clin Invest 1985;76:1536–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webb AR. Who, what, where and when-influences on cutaneous vitamin D synthesis. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2006;92:17–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clemens TL, Adams JS, Henderson SL, Holick MF. Increased skin pigment reduces the capacity of skin to synthesise vitamin D3. Lancet 1982;1:74–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawson-Hughes B. Racial/ethnic considerations in making recommendations for vitamin D for adult and elderly men and women. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80(suppl):1763S–6S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brot C, Jorgensen NR, Sorensen OH. The influence of smoking on vitamin D status and calcium metabolism. Eur J Clin Nutr 1999;53:920–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wortsman J, Matsuoka LY, Chen TC, Lu Z, Holick MF. Decreased bioavailability of vitamin D in obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;72:690–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Looker AC. Body fat and vitamin D status in black versus white women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:635–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parikh SJ, Edelman M, Uwaifo GI, et al. The relationship between obesity and serum 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D concentrations in healthy adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:1196–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Rimm EB, et al. Prospective study of predictors of vitamin D status and cancer incidence and mortality in men. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98:451–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scragg R, Camargo CA., Jr Frequency of leisure-time physical activity and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in the US population: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168:577–86, discussion 587–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nesby-O'Dell S, Scanlon KS, Cogswell ME, et al. Hypovitaminosis D prevalence and determinants among African American and white women of reproductive age: third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:187–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heikkinen A, Parviainen MT, Tuppurainen MT, Niskanen L, Komulainen MH, Saarikoski S. Effects of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy with and without vitamin D3 on circulating levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. Calcif Tissue Int 1998;62:26–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Hoof HJ, van der Mooren MJ, Swinkels LM, Sweep CG, Merkus JM, Benraad TJ. Female sex hormone replacement therapy increases serum free 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3: a 1-year prospective study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1999;50:511–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holick MF. High prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy and implications for health. Mayo Clin Proc 2006;81:353–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine Vitamin D. Dietary reference intakes for calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, vitamin D, and fluoride. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1997:250–87 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Human Services and US Department of Agriculture Dietary guidelines for Americans. 2005. Available from: http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/document/pdf/DGA2005.pdf (cited 23 July 2009)

- 35.Hollis BW. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin d levels indicative of vitamin D sufficiency: implications for establishing a new effective dietary intake recommendation for vitamin D. J Nutr 2005;135:317–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dawson-Hughes B, Heaney RP, Holick MF, Lips P, Meunier PJ, Vieth R. Estimates of optimal vitamin D status. Osteoporos Int 2005;16:713–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Dietrich T, Dawson-Hughes B. Estimation of optimal serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D for multiple health outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:18–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armstrong BK, White E, Saracci R. Principles of exposure measurement in epidemiology. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Looker AC, Dawson-Hughes B, Calvo MS, Gunter EW, Sahyoun NR. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status of adolescents and adults in two seasonal subpopulations from NHANES III. Bone 2002;30:771–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Looker AC, Pfeiffer CM, Lacher DA, Schleicher RL, Picciano MF, Yetley EA. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status of the US population: 1988-1994 compared with 2000-2004. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88:1519–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaugris S, Heaney RP, Boonen S, Kurth H, Bentkover JD, Sen SS. Vitamin D inadequacy among post-menopausal women: a systematic review. QJM 2005;98:667–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Binkley N. Vitamin D: clinical measurement and use. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2006;6:338–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phinney KW. Development of a standard reference material for vitamin D in serum. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88(suppl):511S–2S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Mei IA, Ponsonby AL, Engelsen O, et al. The high prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency across Australian populations is only partly explained by season and latitude. Environ Health Perspect 2007;115:1132–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lips P, Duong T, Oleksik A, et al. A global study of vitamin D status and parathyroid function in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: baseline data from the multiple outcomes of raloxifene evaluation clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:1212–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chapuy MC, Schott AM, Garnero P, Hans D, Delmas PD, Meunier PJ. Healthy elderly French women living at home have secondary hyperparathyroidism and high bone turnover in winter. EPIDOS Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996;81:1129–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rizzoli R, Eisman JA, Norquist J, et al. Risk factors for vitamin D inadequacy among women with osteoporosis: an international epidemiological study. Int J Clin Pract 2006;60:1013–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacques PF, Felson DT, Tucker KL, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and its determinants in an elderly population sample. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;66:929–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhattoa HP, Bettembuk P, Ganacharya S, Balogh A. Prevalence and seasonal variation of hypovitaminosis D and its relationship to bone metabolism in community dwelling postmenopausal Hungarian women. Osteoporos Int 2004;15:447–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brustad M, Alsaker E, Engelsen O, Aksnes L, Lund E. Vitamin D status of middle-aged women at 65-71 degrees N in relation to dietary intake and exposure to ultraviolet radiation. Public Health Nutr 2004;7:327–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andersen R, Molgaard C, Skovgaard LT, et al. Teenage girls and elderly women living in northern Europe have low winter vitamin D status. Eur J Clin Nutr 2005;59:533–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burgaz A, Akesson A, Oster A, Michaelsson K, Wolk A. Associations of diet, supplement use, and ultraviolet B radiation exposure with vitamin D status in Swedish women during winter. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86:1399–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lucas JA, Bolland MJ, Grey AB, et al. Determinants of vitamin D status in older women living in a subtropical climate. Osteoporos Int 2005;16:1641–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lappe JM, Davies KM, Travers-Gustafson D, Heaney RP. Vitamin D status in a rural postmenopausal female population. J Am Coll Nutr 2006;25:395–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim JH, Moon SJ. Time spent outdoors and seasonal variation in serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in Korean women. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2000;51:439–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rock CL, Thornquist MD, Kristal AR, et al. Demographic, dietary and lifestyle factors differentially explain variability in serum carotenoids and fat-soluble vitamins: baseline results from the sentinel site of the Olestra Post-Marketing Surveillance Study. J Nutr 1999;129:855–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lips P, van Ginkel FC, Jongen MJ, Rubertus F, van der Vijgh WJ, Netelenbos JC. Determinants of vitamin D status in patients with hip fracture and in elderly control subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 1987;46:1005–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Engelman CD, Fingerlin TE, Langefeld CD, et al. Genetic and environmental determinants of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels in Hispanic and African Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:3381–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]