Abstract

Background

Medical student interest in internal medicine is decreasing. Whether the internal medicine sub-internship affects intent to pursue internal medicine is unknown.

Objective

Determine the immediate and longer-term effect of the medicine sub-internship on students’ decision to pursue internal medicine residency.

Design

Mixed method, single institution, prospective cohort study.

PARTICIPANTS

Ninety-two students completing an internal medicine sub-internship in 2006.

Measurements

Survey administered prior to and immediately after the sub-internship and prior to the match. Questions included likelihood of applying in internal medicine and perceived impact of the sub-internship on career choice.

Main Results

Seventy-seven percent of students (N = 63) completed the first two surveys; 63% (N = 58) completed the second and third. Immediately post sub-internship, 21% (N = 13) were less likely to apply in internal medicine and 11% (N = 7) were more likely to apply (net change in plans was not significant, p = 0.38). There was a significant relationship between the perceived impact of the sub-internship and likelihood of applying in medicine (ANOVA comparison across means, p < 0.001). Compared to the second survey, on the third survey more students (41%, N = 24) believed the sub-internship positively impacted their decision to apply in medicine, though overall shifting was not significant (p = 0.39). Key themes describing sub-internship impact included the intense workload, value of experiencing internship, rewards of assuming the physician role, and education received (30%, 25%, 20% and 16% of comments, respectively).

Conclusions

Overall, there was not a significant effect of the sub-internship on students’ decision to apply in internal medicine. Additional research about the relative impact of the sub-internship in relationship to other career choice predictors is needed to better address factors that may encourage or dissuade students from pursuing internal medicine.

KEY WORDS: undergraduate medical education, career choice, internal medicine, sub-internship

BACKGROUND

The number of medical students choosing internal medicine careers is decreasing1, and the number of US medical students matching into internal medicine residency has decreased from 30% in 1975 to 20% in 20082. A complex set of factors influences medical students’ career decisions including gender, race, indebtedness, temperament, and relationship styles3–6. Although specialty preference upon medical school matriculation predicts ultimate career choice,7 many medical school experiences, especially during clinical rotations, are also influential8–10. For example, first-year preceptorships with internal medicine faculty and identification of a primary care role model during medical school are associated with a primary care career choice11,12. Student satisfaction with the inpatient clerkship and exposure to highly rated internal medicine attendings and residents also predicts internal medicine residency choice10,13,15. However, a significant amount of the variance in students’ specialty choice can be explained by their perceptions regarding how controllable the lifestyle is of different specialties16. Internal medicine is perceived as “uncontrollable” given long work hours and lack of control over patient care16.

Most United States medical schools require that students complete a sub-internship during their third or fourth year17, and the American College of Physicians has identified the importance of every student having at least one high intensity sub-internship experience prior to residency18. Nationally, approximately 75% of students complete an internal medicine sub-internship, and in approximately half of these sub-internships students are intern substitutes17. For many students, the sub-internship coincides with the time period they are contemplating their residency pathway.

Internship, and hence the sub-internship, is an intense, rigorous experience. This intensity could negatively impact medical students’ career decisions, especially if they believe (correctly or incorrectly) that internship represents the life of a practicing internist. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the immediate and longer-term impact of the internal medicine sub-internship on medical students’ decision to pursue internal medicine residency. We hypothesized that the sub-internship would have an immediate small but negative impact on the desire to pursue internal medicine which would persist over time.

METHODS

Participants

All medical students at our institution are required to complete either a four-week internal medicine sub-internship (students substitute for an intern) or an externship in internal medicine or pediatrics (students assume intern level responsibility but are an addition to the team). The medicine sub-internship is required for students planning to apply for internal medicine residency and is also taken by students contemplating a career in internal medicine. In 2006, 158 students took the medicine (n = 34) or pediatrics (n = 34) externship, or the medicine sub-internship (n = 97) (seven students took both a medicine sub-internship and pediatric externship). This study focuses on the 92 students enrolled in the internal medicine sub-internship between March and October 2006 (five students taking the rotation outside the study period were excluded). Students were asked to participate at the sub-internship orientation that occurred at the start of the rotation. They were told that responses were confidential and would not be reviewed until after the residency match and that a decision to not participate would not affect their grade. The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Each year, the sub-internship is offered at one of two university hospitals or a VA Medical Center. At the time of the study, sub-interns took overnight call every fourth night, could admit up to five patients per call and had a census cap of ten. Two of the three sites had a short call day in which the sub-intern could admit an additional patient. A night float system was in place for admissions after 9:30 pm. On call, sub-interns had cross-cover responsibility for the patients of three other sub-interns. Sub-interns were required to abide by Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education Resident Duty Hours, and systems were in place to assist with post-call workload.

MEASURES

At the sub-internship orientation, students completed a survey asking them to rate their likelihood of applying for residency in 15 different disciplines on a five-point scale (1 = definitely not, 2 = probably not, 3 = unsure, 4 = probably, and 5 = definitely). To assess the short-term impact of the sub-internship, a second survey was administered electronically immediately after students completed their sub-internship. This second survey repeated the initial question, asked how the sub-internship impacted their decision to apply in internal medicine (1 = greatly decreased, 2 = slightly decreased, 3 = had no effect, 4 = slightly increased, and 5 = greatly increased), and had an open-ended question: “How did the internal medicine sub-internship affect your decision to apply in internal medicine?” The longer-term impact of the sub-internship was assessed with a third survey administered electronically in February 2007 (prior to Match Day) again asking students how the sub-internship impacted their decision to apply in internal medicine. Two reminders were sent for the second and third surveys to maximize the response rate. Participants’ ultimate career choices were obtained from the School of Medicine after the match.

ANALYSIS

All survey responses were identified to allow for matching of responses and residency selection and for the analysis that was done at the individual student level. However, no demographic data were collected. We examined the change in reported likelihood of applying in internal medicine before and immediately after the sub-internship looking at the cross tabulated data, using gamma to look at the association between responses over time and the McNemar–Bowker test to examine the symmetry of pre-post changes. The likelihoods of “definitely not” and “probably not” were combined as were “definitely” and “probably;” the former students were considered “unlikely” to apply in internal medicine and the latter “likely.” Analysis of variance was used to estimate the relationship between the direction of impact (away from medicine, the same, or towards medicine) and students’ report of likelihood of entering medicine, using the original 5-point scale. Post-hoc comparison of means was performed using Duncan’s test. We also did cross-tabulation and statistical comparisons for the perceived impact between the second and third surveys (McNemar–Bowker and gamma), and the perceptions of the likelihood of applying to medicine pre and post sub-internship with actual residency placement (only gamma as the tables were not symmetrical). The impact question was recoded so that “greatly decreased” and “slightly decreased” indicated negative impact and “slightly increased” and “greatly increased” indicated positive impact.

Content analysis was performed on the responses to the open-ended question on the second survey. Two authors (FC, JK) independently reviewed the responses and created themes. These themes were then compared to create a final list of themes. Comments, defined as discrete ideas, were independently re-coded with authors blinded to students’ responses to other survey questions. All coding differences were discussed to reach consensus. Differences in comment content between students indicating the sub-internship had a positive, negative or no impact on their likelihood for applying in medicine were examined.

RESULTS

The response rates for the first, second and third surveys were 79% (n = 65), 91% (n = 84) and 65% (n = 60), respectively. Of note, the first survey was not given to students in one month due to a holiday conflict. Sixty-three students (77%) completed the first two surveys; 58 (63%) completed the second and third; 45 (55%) completed all three.

Of the students completing the first two surveys, on the first survey (prior to starting the sub-internship), 34 (54%) indicated that they were likely, 10 (16%) unsure, and 19 (30%) unlikely to apply in internal medicine. On the second survey, completed approximately 5 days (median 5.4 days) after the last day of the sub-internship, 31 (49%) of students indicated they were likely, 7 (11%) unsure, and 25 (40%) unlikely to apply in internal medicine (Table 1). Responses to the first and second survey were strongly associated (gamma = 0.80, p < 0.001), and the net effect of the changes in plans was not statistically significant (McNemar–Bowker test of symmetry = 3.09, p = 0.38). After the sub-internship, 68% of students (n = 43) showed no change in the likelihood of applying in internal medicine, 21% (n = 13) were less likely to apply, and 11% (n = 7) were more likely to. Of the 34 students who reported they would likely enter medicine prior to the sub-internship, nine (26%) indicated they either were unlikely or unsure after. Of the ten students unsure prior to the sub-internship, four became likely, two remained unsure, and four became unlikely to apply in medicine.

Table 1.

Changes in Students’ (n = 63) Likelihood of Applying in Internal Medicine Pre- and Immediately Post Sub-internship

| Post Sub-internship # students (%)* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre sub-internship # students (%)a | Unlikely | Unsure | Likely | |

| Unlikely | 16 (25) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | |

| Unsure | 4 (6) | 2 (3) | 4 (6) | |

| Likely | 5 (8) | 4 (6) | 25 (40) | |

aPercentages refer to the entire table (n = 63), not to individual columns or rows. Responses to the first and second survey were strongly associated (gamma = 0.80, p < .001), but the net effect of the changes in plans not statistically significant (p = 0.38).

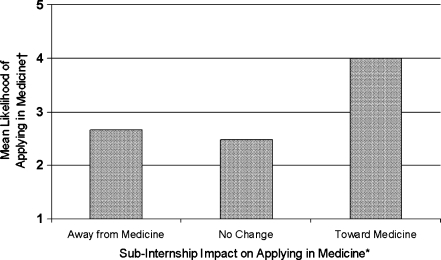

When asked a slightly different question, how the sub-internship impacted their decision to apply for an internal medicine residency, 31% reported a positive impact; 40% reported no impact and 29% reported a negative impact. There was a significant relationship between the perception of how the sub-internship impacted career decisions and the likelihood of applying in internal medicine. On the 5-point scale (1 = definitely not, 5 = definitely), the mean (SD) likelihood was 2.7 (1.8) for those reporting a negative impact, 2.5 (1.7) for those reporting neutral impact, and 4.0 (1.1) for those reporting positive impact (F = 8.901, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Duncan’s post hoc comparison of means showed that the group for whom the sub-internship had a positive impact were significantly different from the groups for which the sub-internship had a negative or no impact.

Fig. 1.

Relationship between likelihood of applying in medicine post sub-internship and perceived sub-internship impact *Impact of sub-internship (x axis) originally measured on a 5-point scale (1 = greatly decreased, 2= slightly decreased, 3 = had no effect, 4 = slightly increased, 5 = greatly increased) but shown here with the end scores collapsed to three groups. † Post-sub-internship likelihood of applying in medicine (y axis) measured on 5-point scale (1= definitely not, 2 = probably not, 3 = unsure, 4 = probably, and 5 = definitely). There was a statistically significant association between impact on applying in medicine and the likelihood of applying in medicine (p < 0.001); see text for details.

Of the 58 students completing the second and third survey, at the time of the third survey, 41% reported the sub-internship had a positive impact on applying in internal medicine whereas 26% felt it had a negative impact and 33% felt it had no impact. Again, responses to the second and third survey were strongly associated, (gamma = 0.78, p < 0.001), and the overall net change was not statistically significant (McNemar–Bowker = 3.00, p = 0.39).

In the total cohort who entered residency, 48% (n = 42/88) matched in internal medicine categorical, internal medicine primary care or medicine/pediatrics programs. This was similar among those who did (46%, n = 30/65) and did not (52%, n = 12/23) complete the first survey, and among those who completed the second survey (49%, n = 41/ 84). Among the 65 who responded pre-sub-internship, 90% (n = 18/20) of those unlikely to apply in medicine in fact applied to some other specialty; 60% (n = 6/10) of those unsure selected fields other than medicine; and 79% (n = 24/35) who thought they would enter medicine ultimately did (gamma = 0.79, p < .001). Second survey likelihoods for 84 students were very similar: 94% (n = 31/33) who indicated a low likelihood did not select medicine; 67% (n = 6/9) who were unsure did not enter medicine whereas 86% (n = 36/42) of those who were likely to select medicine did match in medicine (gamma = 0.94, p < 0.01).

CONTENT ANALYSIS

Fifty-five students (87%) completing the first two surveys answered the open-ended question on the second survey asking how the sub-internship impacted their decision to apply in medicine. Twenty-seven students provided only a brief comment that the sub-internship increased (n = 9), decreased (n = 2), or did not change (n = 16) their desire to pursue internal medicine residency without further explanation. Twenty-eight students provided an explanation (44 comments) about how the sub-internship impacted their career decision. Key themes included the intense workload (30% of comments), the value of experiencing internship (25% of comments), the rewards of assuming the physician role (20% of comments), education received during the rotation (16% of comments), and the influence of patient types cared for (9% of comments). Overall, 64% of these explanations described positive aspects of the sub-internship; 36% described negative ones.

Comment content was explored in relation to perceived impact of the sub-internship on career choice. Of the students reporting that the sub-internship had a negative impact on the decision to apply in medicine, 11 of 12 answered the open-ended question (14 comments). The most common comment (n = 9) related to intense workload. For example, one student less likely to apply in medicine post sub-internship wrote:

“I felt as though I was unable to participate in what was previously the fun part about medicine- thinking through differential diagnosis. . . reading . . . and affecting patient care through targeted therapies . . . . One is so busy surviving the daily role of an intern . . . that there is little time for rest.”

Of the students reporting that the sub-internship had a positive impact on their decision to apply in medicine, 26 of 27 answered the open-ended question (26 comments). Compared with students less likely to apply in medicine, students more likely to apply were less likely to describe the negative workload (4/26 comments). These students described the rewards of assuming the physician role (8/26 comments) and the inherent value of experiencing an internship (9/26 comments).

“It was a great experience having responsibility for my patients, feeling ownership over them and being allowed to participate in their care. I enjoyed building bonds with my patients and feeling like I was helping them understand their diseases better and achieve their goals.”

“It was a good experience and made me realize I could actually be an internal medicine intern and enjoy it and survive.”

Students whose interest in medicine decreased post sub-internship did not mention these themes.

DISCUSSION

Although research has described the influence of clerkship experiences on medical student career choice10,11,13,15,19, to our knowledge, this is one of the first published studies examining the impact of the internal medicine sub-internship. Overall, we found strong associations between students’ responses over time (high gamma values), and no significant net change in students’ career plans from pre to post sub-internship (non-significant McNemar–Bowker test of symmetry). For many, the sub-internship had a neutral or positive effect on internal medicine career choice. Students whose interest in medicine increased post sub-internship felt the rotation helped prepare them for internship and provided increased autonomy and patient responsibility, all established sub-internship goals20. However, for some, the sub-internship had a moderate negative impact on internal medicine career choice. After the sub-internship, 30% of students were less likely to apply in internal medicine and 21% felt it negatively impacted their decision to apply in medicine. In this small sample, the net change in perceived likelihood was not significant. However, many students reported that the sub-internship had a negative impact, the direction of impact was related to the perceived likelihood of entering medicine, and this, in turn, was related to actual career choice.

Students who were less likely to apply in medicine after the sub-internship often described the intense workload. This corroborates prior research suggesting that although students are attracted to internal medicine for its intellectual challenge, teaching, and patient care responsibilities, they are dissuaded from pursuing it, compared with other specialties, because of perceptions about the intense workload10 and challenging practice environment15. Internship is intense and demanding20, and sleep deprivation21, emotional exhaustion and burnout22,23 are common, despite duty hour restriction24. Duty hour regulation has led to re-distributed rather than relinquished work and has been associated with less participation in educational conferences25. Sub-interns perceptions about work intensity, at the expense of education, also may contribute to workload perceptions.

Given that sub-internships often coincide with career decision making, exposing students to the realities of internal medicine is important so that students can make informed career choices and pursue alternative training if dissatisfied with internal medicine. A career plan change during medical school poses less of a challenge than a career plan change during post-graduate training or beyond. A more nuanced understanding of the sub-internship experience as it relates to career choice may ultimately facilitate career counseling and mentoring so that students can find the career path that best suits their interests, skills and long-term goals. Therefore, exploring in larger samples and across more institutions sub-internship features that may attract and or dissuade students from medicine is important in order examine the accuracy of these perceptions. For example, students may believe that the job of the “intern” represents the job of a practicing “internist,” and students might not fully appreciate the breadth of internal medicine, the diversity of patient problems encountered, and the outpatient focus of many general and specialty physicians, factors that may enhance students’ interest26. Ensuring the accuracy of perceptions of features that attract initially less interested students to internal medicine is equally important. Of course, the impact of students’ educational experiences may pale in the context of more influential issues such as lifestyle, perceived (and real) compensation gaps, and disgruntled role models that currently dissuade students from medicine10.

There are several limitations to this small, single institution study. The response rate, although acceptable for the first two surveys, was only 71% for the third survey and only 54% for all three. The effect of the sub-internship on career choice may also depend on the medical school and specific sub-internship characteristics (i.e. case mix, team structure, responsibilities, availability of ancillary support). Data derive primarily from self-reported information which is susceptible to social desirability bias. Timing of the third survey raises the possibility of recall bias. Because we did not measure other sub-internship (i.e., team dynamics, perceived level of support, and sub-internship preparation) and non-sub-internship factors (i.e., other rotations) potentially impacting career choice, we were unable to determine their relative impact. Our qualitative analysis was limited by the small number of available comments.

There is much ongoing discussion about medical students’ declining interest in internal medicine and strategies to reverse this trend. The goal of the sub-internship is not to recruit students, but rather to provide students with a clinical experience that prepares them for the next step in clinical training while educating them about the job of internists and the breadth of internal medicine. Yet, given the continued interest in understanding factors impacting medical student career choice, it may be important to look more closely at how the sub-internship experience as well as other clinical experiences in Departments of Medicine influence perceptions of Internal Medicine. Additional research is needed to better understand sub-internship features that not only dissuade students from medicine but also those features that encourage students to pursue it.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment Presented as a poster presentation at the 2007 Mid-Atlantic Regional and National Society of General Internal Medicine meetings.

Conflict of Interest Statement There were no funding sources, grants, or other financial support for this work.

Footnotes

Dr. Ciminiello was at the University of Pennsylvania at the time this study was conducted.

References

- 1.Match newsletter: Internal Medicine Programs in NRMP 1993-2007. Available at: http://www.im.org/Resources/SurveysandData/MatchData/Documents/APDIM_Match1993-2008.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2010.

- 2.Results and Data. 2008 Main Residency Match. Available at: http://www.nrmp.org/data/resultsanddata2008.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2010.

- 3.Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CH. The impact of U.S. medical students’ debt on their choice of primary care careers: an analysis of data from the 2002 medical school graduation questionnaire. Acad Med. 2005;80:815–819. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200509000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newton DA, Grayson MS, Thompson LF. The variable influence of lifestyle and income on medical students’ career specialty choices: data from two U.S. medical schools, 1998-2004. Acad Med. 2005;80:809–814. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200509000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaidya NA, Sierles FS, Raida MD, Fakhoury FJ, Przybeck TR, Cloninger CR. Relationship between specialty choice and medical student temperament and character assessed with the Cloninger Inventory. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16:150–156. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1602_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciechanowski PS, Russo JE, Katon WJ, Walker EA. Attachment theory in health care: the influence of relationship style on medical students’ specialty choice. Med Ed. 2004;38:262–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2004.01767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabinowitz HK. The role of the medical school admission process in the production of generalist physicians. Acad Med. 1999;74(1Suppl):S39–44. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199901001-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mihalynuk T, Leung G, Fraser J, Bates J, Snadden D. Free choice and career choice: clerkship electives in medical education. Med Ed. 2006;40:1065–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grayson MS, Klein M, Franke KB. Impact of a first-year primary care experience on residency choice. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:860–833. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.10117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauer KE, Durning SJ, Kernan WN, et al. Factors associated with medical students’ career choices regarding internal medicine. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1154–1164. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elnicki DM, Halbritter KA, Antonelli MA, Linger B. Educational and career outcomes of an internal medicine preceptorship for first year medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:341–346. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00352.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connelly MT, Sullivan AM, Peters AS, et al. Variation in predictors of primary care career choice by year and stage of training. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:159–169. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.01208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffith CH, III, Georgesen JC, Wilson JF. Specialty choices of students who actually have choices: the influence of excellent clinical teachers. Acad Med. 2000;75:278–282. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200003000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arora V, Wetterneck TB, Schnipper JL, et al. Effect of the inpatient general medicine rotation on student pursuit of a generalist career. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:471–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauer KE, Fagan MJ, Kernan W, Mintz M, Durning SJ. Internal medicine clerkship directors’ perceptions about student interest in internal medicine careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1101–1104. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0640-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorsey ER, Jarjoura D, Rutecki GW. The influence of controllable lifestyle and sex on the specialty choices of graduating U.S. medical students, 1996-2003. Acad Med. 2005;80:791–796. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200509000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sidlow R. The structure and content of the medical subinternship: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:550–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016008550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinberger SE, Smith LG, Collier VU. Education committee of the American College of Physicians. Redesigning training for internal medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2006;114:927–932. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-12-200606200-00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meurer LN. Influence of medical school curriculum on primary care specialty choice: analysis and synthesis of the literature. Acad Med. 1995;70:388–397. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199505000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fagan MJ, Curry RH, Gallagher SJ. The evolving role of the acting internship in the medical school curriculum. Am J Medicine. 1998;104:409–412. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(98)00121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosen IM, Gimotty PA, Shea JA, Bellini LM. Evolution of sleep quantity, sleep deprivation, mood disturbances, empathy, and burnout among interns. Acad Med. 2006;81:82–85. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200601000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas NK. Resident burnout. JAMA. 2004;292:2880–2889. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.23.2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:358–367. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goitein L, Shanafelt TD, Wipf JE, Slatore CG, Back AL. The effects of work-hour limitations on resident well-being, patient care, and education in an internal medicine residency program. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2601–2606. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horwitz LI, Krumholz HM, Huot SJ, Green ML. Internal medicine residents’ clinical and didactic experiences after work hour regulations: a survey of chief residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:961–965. doi: 10.1007/BF02743145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hauer KE, Alper EJ, Clayton CP, Hershman WY, Whelan AJ. Woolliscroft. Educational responses to declining student interest in internal medicine careers. Am J Med. 2005;118:1164–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]