Abstract

Background

General internists and other generalist physicians have traditionally cared for their patients during both ambulatory visits and hospitalizations. It has been suggested that the expansion of hospitalists since the mid-1990s has “crowded out” generalists from inpatient care. However, it is also possible that declining hospital utilization relative to the size of the generalist workforce reduced the incentives for generalists to continue providing hospital care.

Objective

To examine trends in hospital utilization and the generalist workforce before and after the emergence of hospitalists in the U.S. and to investigate factors contributing to these trends.

Design

Using data from 1980–2005 on inpatient visits from the National Hospital Discharge Survey, and physician manpower data from the American Medical Association, we identified national trends before and after the emergence of hospitalists in the annual number of inpatient encounters relative to the number of generalists.

Results

Inpatient encounters relative to the number of generalists declined steadily before the emergence of hospitalists. Declines in inpatient encounters relative to the number of generalists were driven primarily by reduced hospital length of stay and increased numbers of generalists.

Conclusions

Hospital utilization relative to generalist workforce declined before the emergence of hospitalists, largely due to declining length of stay and rising generalist workforce. This likely weakened generalist incentives to provide hospital care. Models of care that seek to preserve dual-setting generalist care spanning ambulatory and inpatient settings are most likely to be viable if they focus on patients at high risk of hospitalization.

KEY WORDS: hospital medicine, hospitalists, general internal medicine, historical trends, workforce, organization of work, national hospital discharge data, national ambulatory medical care data

INTRODUCTION

General internists and other primary care physicians (PCPs) in the United States have traditionally cared for patients both in ambulatory settings and in the hospital. Such comprehensive care across settings has been a defining characteristic of the practice of general internal medicine, and both patients and physicians have come to expect PCPs to be leaders in coordinating care across settings.1, 2 Over the past decade, the tremendous growth in the use of hospitalists has generated concern that inpatient specialization may erode this traditional dual-setting model of the practice of general internal medicine.1–6 However, while there has been much speculation about the potential effects of hospitalists on the engagement of generalist physicians in inpatient care, there has been little examination of broader forces that may have affected the role of generalist physicians in inpatient care, for example increasing use of hospitalists due to hospital cost-containment efforts following the establishment of the Medicare Prospective Payment System,7–9 and perhaps long-term changes in the incentives for PCPs to expend the time and effort needed to provide care in both settings.

In this paper we focus on one set of factors that could have influenced the growth of hospitalists, the rate of hospitalization relative to the size of the generalist physician workforce. This is motivated by the idea that, if PCPs need to travel from their offices to see their patients when they are hospitalized, whether as the physician of record, as a consultant, or for an uncompensated “social visit,” falling hospitalization rates relative to the size of generalist workforce would imply that each physician would have fewer patients in the hospital on average and decreased incentives to travel to see their patients when hospitalized. For such trends to contribute to the emergence of hospitalists, they would need to have existed prior to the rapid growth in the use of hospitalists.

To describe patterns over time in hospitalization rates relative to generalist workforce and assess whether these patterns may have influenced the growth of hospitalists, we used national data on inpatient utilization and data on generalist physician manpower to construct historical trends in generalist inpatient activity from 1980–2005. We compared trends in these variables during the Pre-Hospitalist Era in the U.S., from 1980–1994, and during the Post-Hospitalist Era, from 1995–2005. We also examined the effects of changing numbers of hospitalizations, hospital length of stay, and numbers of generalists on these trends. We also used data on the probability of admission to the hospital following a generalist ambulatory visit to assess whether this suggested similar trends in hospitalization relative to generalist activity.

METHODS

Data

We used data on hospital discharges in the U.S. from the National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS) for 1980–2005. The NHDS is a multi-stage probability sample of discharges from non-federal short-term acute care hospitals in the U.S. conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics. Data on physician office visits came from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) for all years in which NAMCS was executed from 1980–2005. The NAMCS is a multi-stage probability sample of outpatient encounters between patients and medical and surgical physicians. Finally, data on physician manpower from 1980–2005 came from the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the U.S., a published series that summarizes data from the AMA Physician Masterfile on a nearly annual basis.

Measures

Pre-Hospitalist and Post-Hospitalist Eras in the U.S. were defined as 1984–1994 and 1995–2005 based on the publication in 1996 of an article in the New England Journal of Medicine in which Wachter and Goldman coined the term “hospitalist” to identify a “new breed” of physicians specializing in inpatient care.9 Unpublished data from the Society of Hospital Medicine suggest that 1994 was the beginning of rapid diffusion of the hospitalist model among its membership population.

Total number of inpatient discharges in each year was calculated using all inpatient discharge data from the NHDS for persons aged 18 or older, excluding discharges for newborns and deliveries, and using NCHS sampling weights to obtain national population estimates.

Average hospital length of stay (ALOS) in days for each year was calculated from weighted NHDS data.

Total Inpatient Encounters for each year was calculated by multiplying the total number of hospital admissions by average hospital length of stay. We used all admissions in calculating this measure—rather than just admissions for which the attending of record was a generalist physician. Although we chose this measure partially because we could not identify attending specialty from our data, including all admissions regardless of attending specialty is probably more appropriate because ambulatory physicians may also see their patients as a consultant or visit their hospitalized patients for social reasons or to confer with other providers even when they are not the inpatient attending. This suggests that all hospitalizations can be viewed as contributing to the incentives for a PCP to have ongoing inpatient involvement.

Total number of generalist physicians was defined to include all office-based and hospital-based full-time staff physicians in general internal medicine, family practice, and general practice in the U.S. and territories. These data were obtained from data published nearly annually by the AMA, with missing years (1984, 1987–88, 1991) interpolated by linear approximation from immediately adjacent years. We excluded physicians who were residents, fellows, or in self-designated non-patient-care roles (e.g., administration, teaching and research).

Average Annual Inpatient Encounters Relative to Generalist Workforce The average number of inpatient encounters relative to generalist workforce is an estimate of the maximum annual number of inpatient encounters a generalist would have if they saw all their patients, either as the attending physician, a consultant, or for social reasons, every day the patient is hospitalized. It therefore provides a measure of the maximum incentive they would have over a year to see their patients when they are hospitalized. Eq. 1 provides the mathematical expression and the source of data used in estimating this measure.

|

This measure of maximum potential generalist inpatient activity will rise or fall depending on admissions rates and average length of stay relative to the number of generalists.

Probability of Hospital Admission from a Generalist Office Visit was calculated as an alternative measure of generalist inpatient activity. This was calculated using weighted NAMCS data on disposition status in all years except 1997–1998. We identified all adult visits to generalist offices that were coded with a disposition of hospital admission, and divided by the total number of visits to obtain an estimate of the probability of admission conditional on an office visit. This measure of the inpatient activity of generalists does not account for patients whose hospital admissions are not associated with a generalist office visit (e.g. when a patient presents directly to the emergency department) and does not identify the inpatient attending of record, and may therefore under- or overestimate actual inpatient activity of generalist physicians. It may, however, provide a useful additional measure of hospitalization rates relative to generalist activity over time and a way to validate the trends observed in Average Annual Inpatient Encounters Relative to Generalist Workforce.

Empirical Analyses

To understand trends in the inpatient activity of generalists in the Pre- and Post-Hospitalist Eras, we plotted Average Annual Inpatient Encounters Relative to Generalist Workforce and the Probability of Admission from a Generalist Office Visit from 1980–2005 and visually compared the trends in these measures over these periods. To assess the association of these two measures of generalist inpatient activity, we plotted them versus each other and calculated their correlation. Finally, to understand components of change in the average annual total inpatient encounters per generalist, we plotted trends in total inpatient admissions, ALOS, and total number of generalists.

RESULTS

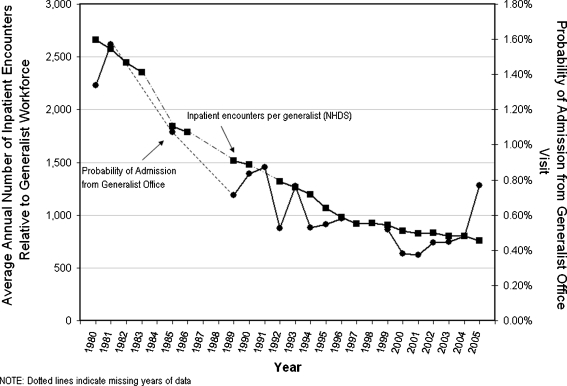

Figure 1 plots trends in average annual inpatient encounters relative to generalist workforce and the probability of admission from a generalist office visit in the U.S. from 1980–2005. Both measures decline steadily over the period, with the steepest decline during the Pre-Hospitalist (1980–1994) Era, suggesting that inpatient activity of generalists was decreasing well before the advent of hospitalists.

Figure 1.

Trends in average annual inpatient encounters relative to generalist workforce and probability of admission from generalist office visit: U.S., 1980–2005.

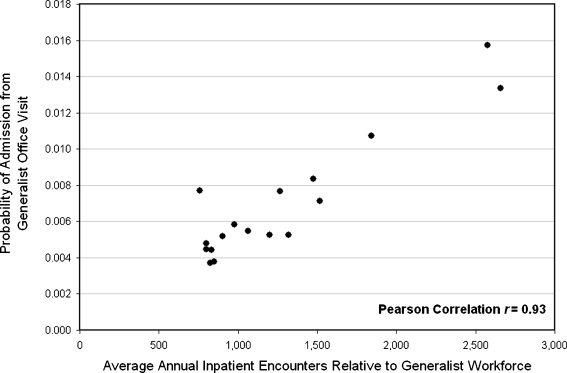

Figure 2 shows an X-Y plot of the average annual inpatient encounters relative to generalist workforce and the probability of admission from a generalist office visit. This figure shows the high correspondence between these measures of inpatient activity relative to generalist ambulatory activity. The Pearson correlation coefficient between these measures was 0.93 (p <0.01). This suggests a high degree of convergent validity of these measures in inferring changes in hospitalization rates relative to generalist ambulatory activity.

Figure 2.

Correlation between average annual inpatient encounters relative to generalist workforce and probability of admission from generalist office visit.

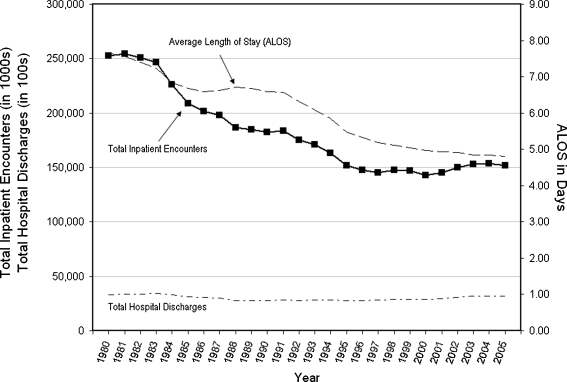

The dramatic decline in annual inpatient encounters relative to the numbers of generalists may have been driven by a decline in total inpatient encounters, a rise in the number of generalists, or both. Figure 3 describes the trends in average annual inpatient encounters relative to generalist workforce, the total annual number of inpatient encounters (numerator), and the number of generalists (denominator). Total inpatient encounters fell 35% during the Pre-Hospitalist Era, from 253,000,000 in 1980 to 163,000,000 in 1994, but remained relatively flat during the Post-Hospitalist Era. The number of generalists grew steadily over the period, approximately doubling from below 100,000 to over 200,000.

Figure 3.

Average annual inpatient encounters relative to generalist workforce and components of change.

To understand the decline in hospital encounters over this period, we plotted trends in the total number of hospital discharges and the average length of stay (ALOS). Figure 4 shows that the total number of discharges remained relatively flat from 1980–2005, but ALOS declined steadily over the period, for a total decline of about 1/3 over the period studied.

Figure 4.

Total inpatient encounters and components of change.

To summarize, both our measures of inpatient activity relative to ambulatory activity—average annual inpatient encounters relative to generalist workforce and the rate of hospital admission from generalist office visits—declined from 1980–2005, with the greatest decline during the Pre-Hospitalist Era. Inpatient encounters relative to generalist workforce fell by about half because of doubling of the number of generalists and another third by declines in inpatient encounters, which were most strongly influenced by shorter ALOS rather than decreasing hospital admissions.

Secondary Analyses and Results

Finding declines over time in hospital admissions relative to generalist supply and in admissions rates from generalist ambulatory visits, we sought to determine whether they might be explained by shifts in the reasons for office visits towards conditions that are unlikely to result in hospital admission (e.g., preventive care) or declines in the probability of admission within diagnoses, e.g., if patients with community-acquired pneumonia were more likely to be managed as outpatients, or some combination of these potential explanations. To explore these hypotheses, we divided the total number of adult office visits in 1980 and 2005 into the top 25 principal diagnoses (defined using the first three digits of ICD-9CM code) with the greatest hospital admissions rate in 1980 and a category for the remaining diagnoses. We then used the method of Das Gupta (1978)10 to decompose the difference in admission rates into: changes in each diagnostic category’s share of visits (diagnosis-specific probability of admission held constant); changes in the diagnosis-specific probability of admission (share of visits by diagnosis held constant); and changes due to the interaction of changes in the mix of diagnoses and changes in the diagnosis-specific probability of admission.

From 1980–2005, the percent of generalist office visits ending in hospital admission declined from 1.34% to 0.77%. We decomposed this 0.57 percentage point decline into a 0.06 percentage point decline due to changes in the distribution of ambulatory diagnoses, a 0.51 percentage point decline due to changes in the probability of admission given ambulatory diagnosis, and a 1.76(10−5) percentage point gain due to the interaction of these changes. Thus, these declines in admission rates following ambulatory encounters with generalists were driven by changes in the probability of hospitalization given a diagnosis rather than by changes in the distribution of generalist ambulatory visits between more and less hospitalization-prone diagnoses.

CONCLUSION

The trends we have shown in inpatient activity relative to generalist workforce and the probability of hospital admission following a generalist office encounter both suggest that the inpatient activity of generalist physicians declined tremendously after 1980 but flattened in the Post-Hospitalist Era. These findings suggest that the declining inpatient activity of generalist physicians has not resulted primarily from hospitalists “crowding out” traditional generalists from inpatient care. Instead, our findings suggest that increases in the number of generalists and declines in hospitalization and length of stay reduced the volume of, and likely incentives for, generalist inpatient activity over the 15 years before the rapid growth of hospitalists.

Limitations

While it seems apparent that a decreasing volume of hospitalization would decrease the incentives for PCPs to travel to care for their patients when hospitalized, our analysis does not directly measure these incentives, which would be influenced by many factors including the rates at which these physicians serve as attendings, consultants, or unpaid “visitors”, and the economic and non-economic incentives to serve in these roles. Estimating such incentives directly is prevented by the lack of data on the rates at which primary care physicians assume these roles and the economic and noneconomic incentives for doing so, which could be extremely complex. Therefore, the total volume of inpatient care may be the most appropriate measure of the overall incentives for generalist physicians to see their patients when they are hospitalized that can be measured nationally and over time. Future studies might seek to measure these economic and non-economic incentives in settings where data is available.

DISCUSSION

Future trends in generalist inpatient activity may diverge from the past trends described here. Nevertheless, changes in the number of generalist physicians, hospitalization rates, and length of stay may influence future trends in generalist inpatient activity. For example, though the relatively rapid growth in the number of generalist physicians during the 1980s and 1990s has not continued in recent years, if current efforts at physician payment reform succeed in encouraging entry into generalist specialties, then inpatient activity relative to the generalist workforce could decline further.11 Continuing declines in hospitalization rates and length of stay also seem likely with continuing pressures to control hospital costs, for example by reducing readmissions and by greater emphasis on disease management for patients at greatest risk of hospitalization.12

Many patients and generalist physicians may consider the decline in inpatient activity of generalists undesirable because of the potential for generalists to make valuable contributions to the care of their patients when hospitalized. However, the cost of maintaining skills in inpatient medicine and of traveling to the hospital to see a declining number of hospitalized patients may make decreased inpatient activity economically attractive for many generalists. The tension between these perspectives is an example of a more general challenge in the division of labor between the advantages of experience that comes with specialization and the costs of coordination that comes with greater division of labor.13–15 Accordingly, solutions to these problems could involve approaches to diminish the need for experience or reduce the costs of coordination. There is no data suggesting that there are reliable substitutes for inpatient experience but there is a large literature on improving care transitions involving hospitalists16–18 and physician accountability which could reduce coordination costs. Medical home models may also potentially improve coordination by rewarding generalists for devoting effort to better coordination of care.19

Medical home models could also provide incentives for PCPs to see patients in the inpatient setting.19 However, the fact that integrated health systems, such as Kaiser, have broadly adopted the use of hospitalists suggests that capitated payment systems alone will not greatly increase the inpatient activity of generalists.20 This could change if PCPs had greater numbers of patients in the hospital at any time so that the economic and clinical incentives to travel to the hospital to see those patients were increased. One way this could happen is if care were provided through team models of care in which non-physician providers could see patients for care that does not require physician involvement. This would allow PCPs to carry a larger panel of patients, and therefore have more patients hospitalized at any time. This might, however, weaken the ties between physicians and their patients as they had less ambulatory engagement with each other.

Alternatively, physicians wishing to have enough hospitalized patients to make combining ambulatory and inpatient care economically viable could select a patient population at high risk of hospitalization. Practical tools to identify patients at high risk of hospitalization based on characteristics such as age, diagnoses, and medications exist. For example, Putnam et al. describe a model that identifies 10% of patients in eight HMOs with an annual risk of hospitalization approaching 30%.21 With a 30% annual admission rate, a PCP with a panel of 1200 patients, about half the size of typical primary care panels in the U.S,. would admit about one patient to the hospital each day, resulting in an average inpatient census of 4–5 patients given typical hospital lengths of stay.22 Physicians such as these, whose jobs would resemble those of traditional internists of earlier eras, might be drawn from the ranks of general internists or hospitalists, but would seem likely to develop identities somewhat different than either, perhaps as “hospital-focused general internists” or “primary care hospitalists”. Such physicians might be preferred by some patients at high risk of hospitalization. They might also be preferred by payers if they were able to reduce costs for these likely high-cost patients. As a result, patients and/or payers might be willing to pay premia for physicians willing to assume these responsibilities.

Our analysis suggests that changes in the healthcare sector over the past quarter century have made specialization in either inpatient or ambulatory settings increasingly attractive to generalist physicians. There is also evidence that hospitalists who spend a larger fraction of their time in inpatient care may reduce costs while at least maintaining outcomes compared to non-hospitalist physicians who do not have a prior relationship with the patient.23,24 However, there is not good data that hospitalists improve outcomes or reduce costs compared to patients’ own PCPs. Given this, care models that encourage some generalist physicians to focus on patients at high risk of hospitalization may be especially attractive, addressing the economic incentives of providers and the broader health care system, and the clinical needs of patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge financial support for this work by Robert Wood Johnson Investigator Program (Grant # 63910, Meltzer, PI), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality through the Hospital Medicine and Economics Center for Education and Research in Therapeutics (CERT) U18 HS016967-01 (Meltzer, PI), and a National Institute of Aging Midcareer Career Development Award from the National Institute of Aging K24-AG31326 (Meltzer, PI).

Conflict of Intereset None disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lo B. Ethical and policy implications of hospitalist systems. Am J Med. 2001;111(9B):48–52. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00972-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sox HC. The hospitalist model: perspectives of the patient, the internist, and internal medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(4 Pt 2):368–72. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-4-199902161-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auerbach AD, Nelson EA, Lindenauer PK, Pantilat SZ, Katz PP, Wachter RM. Physician attitudes toward and prevalence of the hospitalist model of care: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2000;109(8):648–53. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00597-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez A, Grumbach K, Goitein L, Vranizan K, Osmond DH, Bindman AB. Friend or foe? How primary care physicians perceive hospitalists. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(19):2902–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.19.2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schroeder SA, Schapiro R. The hospitalist: new boon for internal medicine or retreat. Ann Intern Med. 1999;30(4):382–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-4-199902161-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolan JP. Internal medicine in the current health care environment: a need for reaffirmation. Ann Intern Med. 1988;128(10):857–62. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-10-199805150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamel MB, Drazen JM, Epstein AM. The growth of hospitalists and the changing face of primary care. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1141–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0900796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pham HH, Grossman JM, Cohen G, Bodenheimer T. Hospitalists and care transitions: the divorce of inpatient and outpatient care. Health Aff. 2008;27(5):1315–27. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das Gupta P. A general method of decomposing a difference between two rates into several components. Demography. 1978;15(1):99–112. doi: 10.2307/2060493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodenheimer T, Berenson RA, Rudolf P. The primary care-specialty income gap: why it matters. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(4):301–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-4-200702200-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stille CJ, Jerant A, Bell D, Meltzer D, Elmore JG. Coordinating care across diseases, settings, and clinicians: a key role for the generalist practice. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(8):700–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-8-200504190-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker GS, Murphy KM. The division of labor, coordination costs and knowledge. Q j econ. 1992;107(4):1137–1160. doi: 10.2307/2118383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williamson OE. The economics of organization: the transaction cost approach. Am J Sociol. 87:548–577.

- 15.Meltzer D. Hospitalists and the doctor-patient relationship. J Legal Stud. 2001;30(2):589–606. doi: 10.1086/339294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pham HH, Grossman JM, Cohen G, Bodenheimer T. Hospitalists and care transitions: the divorce of inpatient and outpatient care. Health Aff. 2008;27(5):1315–27. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arora VM, Farnan JM. Care transitions for hospitalized patients. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(2):315–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of care consensus policy statement American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College of Emergency Physicians, Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0969-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craig DE, et al. Implementation of a hospitalist system in a large health maintenance organization : the Kaiser Permanente experience. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(4 Pt 2):355–359. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-4-199902161-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Putnam KG, Buist DSM, Fishman P, Andrade SE, Boles M, Chase GA, Goodman MJ, Gurwitz JH, Platt R, Raebel MA, Chan KA. Chronic disease score as a predictor of hospitalization epidemiology, Vol. 13, No. 3 (May, 2002), pp. 340–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Bodenheimer T. Primary care – will it survive? NEJM. 2006;355:861–864. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866–74. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parekh V, Saint S, Furney S, Kaufman S, McMahon L. What effect does inpatient physician specialty and experience have on clinical outcomes and resource utilization on a general medicine service? J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(5 Pt 1):395–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]