Summary

Objective

Chondrocytes exhibit specific responses to BMPs and TGF-βs. The bioactivity of these growth factors is regulated by numerous mediators. In our previous study, Smad1 was found to interact with the cytoplasmic domain of the hyaluronan receptor CD44. The purpose of this study was to determine the ability of hyaluronan in the pericellular matrix to modulate the chondrocyte responses to BMP-7 or TGF-β1.

Experimental design

Nuclear translocation of Smad1, Smad2 and Smad4 was studied in bovine articular chondrocytes in response to BMP-7 and TGF-β1. The effects of matrix disruption by hyaluronidase treatment and the initiation of matrix repair by the addition of hyaluronan on the nuclear translocation of Smad proteins, Smad1 phosphorylation and luciferase expression by a CD44 reporter construct in response to BMP-7 were also studied.

Results

The disruption of the hyaluronan-dependent pericellular matrix of chondrocytes resulted in diminished nuclear translocation of endogenous Smad1 and Smad4 in response to BMP-7; however, the nuclear translocation of Smad2 and Smad4 in these matrix-depleted chondrocytes in response to TGF-β1 was not diminished. Incubation of the matrix-depleted chondrocytes with exogenous hyaluronan restored Smad1 and Smad4 nuclear translocation and increased pCD44(499)-Luc luciferase expression in response to BMP-7. Both exogenous hyaluronan and matrix re-growth enhanced by HAS2 transfection restored Smad1 phosphorylation.

Conclusions

Disruption of hyaluronan-CD44 interactions has little effect on the TGF-β responses; however, re-establishing CD44-hyaluronan ligation promotes a robust cellular response to BMP-7 by articular chondrocytes. Thus, changes in cell-hyaluronan interactions may serve as a mechanism to modulate cellular responsiveness to BMP-7.

Introduction

In articular cartilage, hyaluronan serves as the core filament of the proteoglycan aggregate; these macromolecular aggregates composed of hyaluronan, link protein and the major cartilage proteoglycan, aggrecan, establish essential biomechanical properties of cartilage1, 2. The ability of hyaluronan to influence cell behavior is due in part to its role in the organization of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and the capacity of hyaluronan to interact directly with cells3. Hyaluronan synthase-2 (HAS2) is primarily responsible for hyaluronan synthesis in articular chondrocytes4. CD44 serves as a primary transmembrane receptor for hyaluronan, providing cells a mechanism for matrix attachment or for sensing changes in the ECM5. CD44 can also serve as a docking protein to organize other molecules in the membrane, the pericellular matrix or the cortical cytoplasm but has no intrinsic kinase activity2,6. Therefore, CD44-hyaluronan interactions link the ECM to elements of the cytoskeleton and other component proteins of signaling pathways.

The transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily includes the three isoforms of TGF-β, the activins and the bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP). These secreted proteins are anabolic morphogens and growth factors with critical functions for the articular joint7. BMP-7 is synthesized by articular chondrocytes8, has been shown to upregulate the expression of CD449,10 as well as the expression of HAS29,10 and aggrecan9-11 by chondrocytes resulting in enhanced ECM deposition and retention.

The receptors for the TGF-β superfamily are serine/threonine kinases, termed type I and type II receptors. The active BMP-7 receptor complex consists of a BMP-7 dimer, two type I (ALK2) receptors and two type II (ActR-II) receptors12. Substrates for type I receptors include members of the Smad protein family13. The common BMPs utilize Smad1, Smad5, Smad8 as signaling partners whereas TGF-βs utilize Smad2 or Smad314 which upon phosphorylation form complexes with Smad4 that undergo nuclear translocation as an early cellular response to stimulation. BMP-7 and BMP-6 activate Smad1 and Smad5 but not Smad815. Signaling is dependent on the bioavailability of BMPs to the cognate receptors16 as well as Smad proteins17.

In our previous study18, a yeast-two hybrid screen and co-immunoprecipitation studies revealed an interaction between Smad1 and CD44, which was reduced after BMP-7 stimulation. The disruption of hyaluronan binding to CD44, either by Streptomyces hyaluronidase treatment or over-expression of a dominant negative CD44HΔ67 or truncated CD44HΔ54, resulted in diminished responses to BMP-7; these results support a functional link between the canonical BMP-7/BMP-R/Smad1 signaling pathway and endogenous hyaluronan-CD44 interactions.

Chondrocytes may sense and respond to changes in the ECM in part via hyaluronan- CD44 interactions. This study investigates hyaluronan-CD44 interactions on the Smad1/4 response initiated in articular chondrocytes by BMP-7 as compared with the Smad2/4 response by chondrocytes after TGF-β1 treatment. Our results suggest that disruption of hyaluronan-chondrocyte interactions has little effect on TGF-β1 responses, but establishing or re-establishing CD44-hyaluronan ligation promotes a robust cellular response to BMP-7 thus distinguishing the effect of the ECM on the response of chondrocytes to these two anabolic factors.

Materials and Methods

CELL CULTURE

Bovine articular chondrocytes were isolated from metacarpophalangeal joints of 18-month-old animals (full thickness slices) by sequential incubation in 0.2% Pronase (Calbiochem) for 1 h and 0.0025% collagenase (Roche) for 16 h. The chondrocytes were cultured in DMEM/F12, with 10% FBS and 1μg/ml ascorbic acid prior to initiation of experimental conditions to allow for optimal recovery19. Prior to stimulation with growth factors, the chondrocytes were cultured in low-serum-containing media (0.5% FBS) for an additional 24 h. Then the chondrocytes were stimulated for 1 h with 100ng/ml BMP-7 or 5ng/ml TGF-β1 (R&D Systems). To determine the effects of matrix removal on growth factor responses, chondrocytes were pretreated with 5 U/ml Streptomyces hyaluronidase (Sigma) 90 min to generate “matrix-depleted” cells19. To determine the effects of exogenous hyaluronan on growth factor responsiveness by matrix-depleted cells, these chondrocytes were incubated with 100 μg/ml high molecular mass hyaluronan (Healon;Pharmacia Upjohn, North Peapack, NJ) prior to stimulation.

IMMUNOCYTOCHEMISTRY

Bovine chondrocytes were plated into chamber slides, at 200,000 cells/chamber, directly following isolation from cartilage. After stimulation with BMP-7 or TGF-β1, with or without hyaluronidase pretreatment or hyaluronan add-back, the cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton-X-100 and then incubated overnight with anti-Smad1, Smad2 or Smad4 polyclonal antibodies (Cell Signaling) in 10% goat serum/1% BSA/PBS. Rhodamine red-X IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) was used for detection and DAPI (Molecular Probes) as a nuclear counterstain. In these studies, the anti-Smad antibodies that recognize both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms were used. To detect BMP receptors, chondrocytes were incubated with the ActR-IIA antibody or the BMPR-IB antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The cells were viewed using a Nikon Ellipse E600 microscope equipped with Y-Fl Epi-fluorescence, PLAN-Apochromat 1.4 NA/60x oil and PLAN 0.5 NA/20x objectives. Images were captured digitally in real time using a Spot-RT camera (Diagnostic Instruments; Sterling Heights, MI) and processed using MetaView imaging software (Molecular Devices; Sunnyvale, CA).

To investigate effects of cell shape on growth factor responsiveness, chondrocytes cultured in alginate beads were stimulated with BMP-7 or TGF-β1, with or without hyaluronidase pretreatment, then also fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton-X-100 prior to release from the alginate beads using 55 mM NaCitrate containing 150 mM NaCl to affect depolymerization of the alginate20. Following immunostaining, these chondrocytes were mounted onto slides in medium containing DAPI.

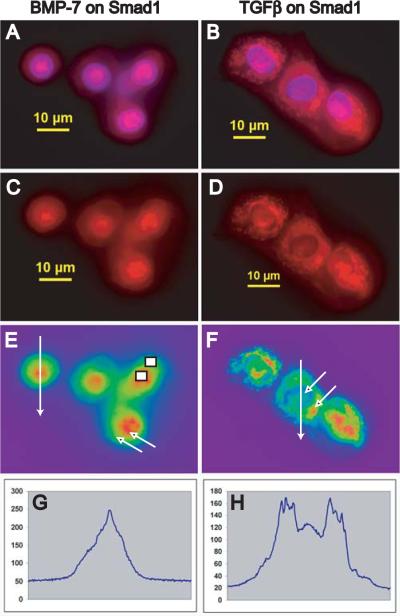

A morphometric analysis of Smad nuclear translocation was performed on single color images (red fluorescence intensity ranging from 30-255 relative units) using NIS-Elements BR2.30 imaging software (Nikon) to determine the ratio of pixel intensity in the nucleus versus pixel intensity in the cytoplasm on a per cell basis. Maximal pixel intensity was determined at point values taken within regions of the nucleus and cytoplasm, equivalent to areas denoted by arrows in Figure 1E and 1F, with nuclear localization confirmed by DAPI-colocalization in overlay images (Ratio #1; Table 1). These data were confirmed by two additional separate observers. As an alternative approach, mean pixel intensity was determined within equivalent rectangular regions of the nucleus and cytoplasm, exemplified by the rectangles in Figure 1E (Ratio #2; Table 1). Images viewed under high power oil typically contained 3-5 cells per field with 12-30 cells counted per condition (therefore ~3-5 fields per condition). For untreated chondrocytes the ratio of nuclear to cytoplasmic staining for Smad1, Smad2 and Smad4 ranged from 1.03 to 1.27 representing a lack of defined nuclear staining or primarily cytoplasmic staining. After treatment with BMP-7, the ratio of nuclear to cytoplasmic staining for Smad1 and Smad4 ranged from 1.57 to 2.16 representing nuclear localization of the Smad immunostaining.

Fig. 1.

Smad1 immunolocalization in bovine articular chondrocytes following BMP-7 or TGF-β1 stimulation. Immunostaining of endogenous Smad1 used a polyclonal antibody that recognizes Smad1 in both a non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated state and a Rhodamine Red-conjugated secondary antibody. Chondrocytes were cultured in media with 0.5% FBS and stimulated for 1 hour with BMP-7 (A,C,E) or TGF-β1 (B,D,F) then stained; DAPI was used as a nuclear marker (A,B). Scale bars equal 10 μm. False colors (E,F) enhance the nuclear/cytoplasmic interface. Maximal pixel intensity was determined at point values taken within regions of the nucleus and cytoplasm, equivalent to areas denoted by arrows (E, F) and mean pixel intensity was determined within equivalent rectangular regions of the nucleus and cytoplasm, exemplified by the rectangles (E). An increase in the ratio of pixel intensity in the nucleus:cytoplasm reflects nuclear translocation of Smad1; see also Table 1. A fluorescent intensity profile along a line segment that intersected the plasma membrane twice and the nucleus twice, with the two endpoints outside the cell (E,F) was plotted along the x-axis (G,H) in the direction indicated by the arrowhead.

Table 1.

Morphometric analysis of Cellular Distribution of Smad1, Smad2 and Smad4 in Bovine Articular Chondrocytes

| Sample | Ratio1 | n-value | Ratio2 | n-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Untreated control chondrocytes | ||||

| Smad1 | 1.03 ± 0.12 | 13 | 1.06 ± 0.16 | 16 |

| Smad2 | 1.21 ± 0.19 | 12 | 1.09 ± 0.08 | 12 |

| Smad4 | 1.27 ± 0.11 | 12 | 1.19 ± 0.14 | 15 |

| B. Chondrocytes treated with BMP-7 | ||||

| Smad1 | 1.78 ± 0.27† | 16 | 1.57 ± 0.22 | 23† |

| Smad4 | 2.16 ± 0.60 † | 18 | 1.80 ± 0.32 | 21† |

| C. Chondrocytes treated with TGF-β1 | ||||

| Smad1 | 1.04 ± 0.19 | 14 | 1.06 ± 0.18 | 13 |

| Smad2 | 1.69 ± 0.29 † | 29 | 1.58 ± 0.21 | 23† |

| Smad4 | 1.51 ± 0.19 † | 19 | 1.29 ± 0.09 (0.0108) | 23† |

| D. Chondrocytes pretreated with S.H'ase | ||||

| Smad1 after BMP-7 | 1.05 ± 0.04 | 13 | 1.06 ± 0.07 | 18 |

| Smad4 after BMP-7 | 1.15 ± 0.17 | 12 | 1.07 ± 0.15 | 17 |

| Smad1 after TGF-β | 1.12 ± 0.07 | 17 | 1.21 ± 0.23 | 18 |

| Smad2 after TGF-β | 1.82 ± 0.21 † | 11 | 1.68 ± 0.27 | 14† |

| Smad4 after TGF-β | 1.62 ± 0.16 † | 19 | 1.40 ± 0.17 (0.0003) | 24† |

| E. Chondrocytes pretreated with S.H'ase followed by HA add-back | ||||

| Smad1 after BMP-7 | 1.58 ± 0.15 † | 15 | 1.57 ± 0.26 | 26† |

| Smad4 after BMP-7 | 1.57 ± 0.20 † | 23 | 1.59 ± 0.21 | 37† |

Values represent the average ratio of maximal pixel intensity (nucleus ÷ cytoplasm) ± S.D. for each cell condition. Maximal pixel intensity was determined at point values taken within regions of the nucleus and cytoplasm, equivalent to areas denoted by arrows in Figure 1E and 1F.

Values represent the average ratio of mean pixel intensity (nucleus ÷ cytoplasm) ± S.D. for each cell condition. Mean pixel intensity was determined within equivalent rectangular regions of the nucleus and cytoplasm as denoted by rectangles in Figure 1E.

Denotes averages that are statistically different from control condition (P<0.0001) as measured using an unpaired Student's t test unless otherwise stated in parentheses.

GENERATION OF CD44 LUCIFERASE REPORTER CONSTRUCTS

The promoter region of the CD44 sequence (GenBank accession number AL356215), intron/exon maps and the 5' untranslated region were identified, mapped and analyzed using Proscan, “TESS” from http://www.cbil.upenn.edy/c-gibin/tess/tess and “MatInspector” from http://www.genomatix.de/products/MatInspector/index.html and potential binding sites for Smad4, Smad3, Smad1 and Egr-1 were identified. Based on these locations, a 5' deletion CD44 gene construct was generated using a sense primer engineered to include the Nhe-1 enzyme restriction site (underlined) on the 5' end: 5' GCT AGC CCA AAG GCT GAA CCC AAT GG 3' and the antisense primer: 5' CTC CTC GAG CAA AAC TTG TCC TTG GTG TCC 3'. This construct, designated pCD44(499)-Luc, is similar to the pBLCD44 construct previously characterized and validated in studies of Egr-1 induction of CD4421, 22. High purity human genomic DNA (Promega) was PCR-amplified using platinum Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) with an annealing temperature of 65°C and an extension temperature of 72°C for 28 cycles. The products were again amplified by PCR using the AmpliTaq polymerase (Roche) and ligated into a TOPO TA Cloning vector (Invitrogen). The CD44 insert was then subcloned into a pGL3 Basic vector (Invitrogen) using enzymes Kpn-1 and Nhe-1. All inserts were verified by restriction digestion analysis and then sequenced (Sequetech; Mountain View, CA). To assure the functional activity of our pCD44(499)-Luc contruct, and to compare its activity to that described for pBLCD4421, 22, it was tested in C-28/I2 cells. Treatment of C-28/I2 cells transfected with pCD44(499)-Luc with BMP-7, IL-1α or IL-1β resulted in a ~50% increase in luciferase activity (data not shown) indicating that responsive elements and the promoter segment were active and capable of driving the expression of luciferase.

TRANSIENT TRANSFECTION AND LUCIFERASE ASSAY

In order to improve transfection efficiency, bovine chondrocytes were passaged twice using trypsin and then transfected in suspension with the pCD44(499)-Luc construct in a 3:1 ratio with Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen). Transfected cells were then subcultured within 3-D alginate bead cultures for 48 h to restore spherical morphology and intact pericellular matrix19. The transfected chondrocytes (within the beads) can be incubated with growth factors or with Streptomyces hyaluronidase prior to release and analysis, however the ability of high molecular mass hyaluronan to penetrate into the alginate beads is limited. Therefore, for hyaluronan add-back experiments, chondrocytes were released from the beads, pre-incubated with or without 100 ug/ml Healon and then treated with 100 ng/ml BMP-7 for 1 h. Cell lysates were prepared with passive lysis buffer (Promega), aliquots were mixed with luciferase assay reagent (Promega) and the relative firefly luciferase units (RLU) were measured on a Sirius luminometer (Zylux Corporation). The RLU values were normalized to total protein in the lysates (Bio-Rad Protein Assay).

WESTERN BLOT ANALYSES

Bovine chondrocytes in high density monolayer cultures in 10% FBS containing media for 5 days and for the subsequent 24 h in 0.5% FBS containing media were left untreated (controls) or pre-treated with 5 U/ml Streptomyces hyaluronidase or 100 U/ml testicular hyaluronidase (Sigma H3506-1G) to remove the pericellular matrix. The matrix-depleted chondrocytes were next either stimulated directly with BMP-7 or incubated for 2 h in the presence of exogenous Healon prior to BMP-7 stimulation for 1 h.

As an alternative to hyaluronan add-back, chondrocytes were transfected with a vector containing cDNA encoding full-length human HAS223 to enhance endogenous hyaluronan synthesis. Briefly, after 5 days of culture, chondrocytes were lifted with 0.1% Pronase/0.1% collagenase, transfected using Lipofectamine2000 and cultured for 2 days of recovery. Control chondrocytes and HAS2-transfected chondrocytes were cultured overnight in serum-free media and then left untreated (controls) or pre-treated with 100 U/ml testicular hyaluronidase to remove the pericellular matrix and then incubated for 2 h for matrix recovery prior to BMP-7 stimulation for 1 h.

Chondrocytes were lysed in 50mM Tris, pH 7.4 with 150mM NaCl, 3mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP-40 buffer, with protease (P2714, Sigma) and phosphatase (P2850, Sigma) inhibitors for western blotting for total Smad1, phosphorylated Smad1 (ser463/465 phosphorylated-Smad1 antibody; Cell Signaling)14,18 and β-actin (AC-15; Sigma). Biotinylated IgG (PIC-4000; Vector Labs), followed by incubation with HRP-Streptavidin (Amersham) and the Luminol Reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used for detection. The resultant band intensities were quantified using a Fluor-S imaging system (Bio-Rad).

Results

NUCLEAR TRANSLOCATION OF SMADS IN ARTICULAR CHONDROCYTES

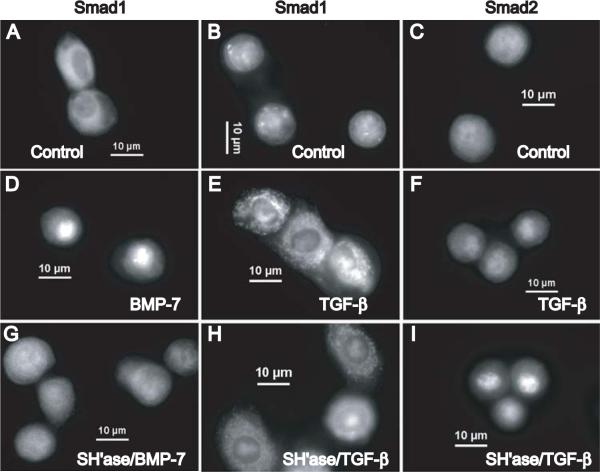

Nuclear translocation of specific receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads) and Smad4 are early cellular responses to stimulation by members of the TGF-β superfamily. Nuclear translocation of Smad1 occurred in response to BMP-7 yielding prominent nuclear immunostaining of Smad1 (Fig. 1A,C,E). However, Smad1 immunostaining remained predominantly in the cytoplasm following TGF-β1 stimulation (Fig. 1B,D,F) indicating the specificity of Smad1 activity. The fluorescence intensity profile along the line segment intersecting the plasma membrane and the nucleus (shown in Fig. 1E, F) shows peak nuclear staining for Smad1 in response to BMP-7 (Fig. 1G) with peak cytosolic staining and low nuclear staining for Smad1 in chondrocytes following TGF-β1 stimulation (Fig. 1H). Endogenous Smad1 (Fig. 2A,B) and Smad2 (Fig. 2C) were both localized in the cytoplasm of quiescent articular chondrocytes. While Smad1 undergoes nuclear translation upon BMP-7 stimulation (Fig. 2D), Smad1 remained cytosolic following TFGβ1 stimulation (Fig. 2E). However, following TFG-β1 stimulation prominent nuclear staining of Smad2 was observed (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Nuclear translocation of Smad1 in response to BMP-7 is matrix-dependent but nuclear translocation of Smad2 in response to TGF-β1 is matrix independent in articular chondrocytes. Panels A,B,D,E,G,H show the immunofluorescence staining of endogenous Smad1 while Panels C,F,I show the staining of endogenous Smad2 in bovine chondrocytes. Chondrocytes were cultured in media with 0.5% FBS (A,B,C) and then stimulated for 1 hour with BMP-7 (D) or TGF-β1 (E,F). In parallel, chondrocytes were pre-treated with Streptomyces hyaluronidase to remove the pericellular matrix and then stimulated for 1 hour with BMP-7 (G) or TGF-β1 (H,I). Scale bars equal 10 μm.

THE PERICELLULAR MATRIX PROMOTES THE CHONDROCYTE RESPONSE TO BMP- 7 YET NOT TGF-β1

Chondrocytes in culture assemble a proteoglycan-rich pericellular matrix that is anchored by CD44-hyaluronan interactions. Treatment of chondrocytes with Streptomyces hyaluronidase to degrade hyaluronan specifically, results in the release of the pericellular matrix, but cell surface expression of CD44, as determined by flow cytometry, is unchanged19. Previously we documented that nuclear translocation of Smad1 in response to BMP-7 occurred in matrix-intact chondrocytes, but not in matrix-depleted chondrocytes18. To address whether the hyaluronan-dependent pericellular matrix also supports the activation of Smad2 resulting in nuclear translocation, chondrocytes were pre-treated with Streptomyces hyaluronidase to remove that matrix, prior to BMP-7 or TFG-β1 treatment. In matrix-depleted chondrocytes, treatment with BMP-7 no longer elicited nuclear translocation of Smad1 (Fig. 2G). However, nuclear translocation of Smad2 after TGF-β1 stimulation was found to occur in matrix-depleted chondrocytes (Fig. 2I). To study the impact of cell shape, these responses were compared with those of chondrocytes cultured for 5 days in alginate beads20. Chondrocytes that were cultured, pre-treated with Streptomyces hyaluronidase and stimulated with TGF-β1 within alginate breads retained specific nuclear translocation of Smad2. However, after Streptomyces hyaluronidase pre-treatment, stimulation of these matrix-depleted chondrocytes within the alginate beads with BMP-7 no longer resulted in Smad1 nuclear translocation (data not shown.) Thus, the cell shape differences between monolayer and alginate suspension culture did not alter the responses to BMP-7 or TGF-β1. However, these data suggest that hyaluronan-chondrocyte interactions do support signaling via Smad1 in the chondrocyte response to BMP-7 but do not affect the Smad2 nuclear translocation in the TGF-β signaling pathway.

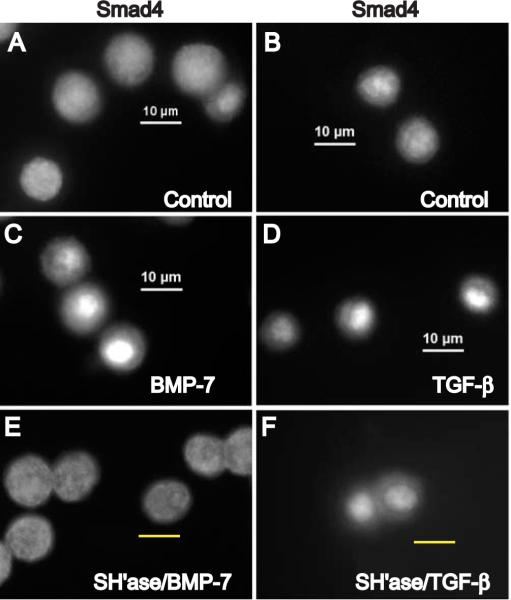

Diffuse cytoplasmic staining of the endogenous co-mediator Smad4 was predominant in chondrocytes cultured under low serum conditions (Fig. 3A,B). Nuclear translocation of Smad4 occurred after a 1 h stimulation with either BMP-7 (Fig. 3C) or TFG-β1 (Fig. 3D). Pre-treatment of chondrocytes with Streptomyces hyaluronidase to remove the pericellular matrix diminished Smad4 nuclear translocation in response to BMP-7 (Fig. 3E). However, nuclear translocation of Smad4 in response to TFGβ1 occurred in matrix-depleted chondrocytes (Fig. 3F) as Smad4 presumably was partnered with Smad2/3. As in previous studies, Streptomyces hyaluronidase treatment did not alter the cell surface immunostaining for CD44, ActRII and BMPR-IB receptors on these bovine articular chondrocytes (data not shown.)

Fig. 3.

Nuclear translocation of Smad4 in chondrocytes. Articular chondrocytes were cultured in media with 0.5% FBS (A,B) and then stimulated for 1 hour with BMP-7 (C) or TGF-β1 (D). In parallel, chondrocytes were pre-treated with Streptomyces hyaluronidase to remove the pericellular matrix and then stimulated for 1 hour with BMP-7 (E) or TGF-β1 (F). Scale bars equal 10 μm. The immunostaining patterns for Smad4 correlated with those for Smad1 and Smad2 under the treatment conditions; nuclear translocation of endogenous Smad4 in response to BMP-7 is matrix-dependent but is matrix-independent in response to TGF-β1.

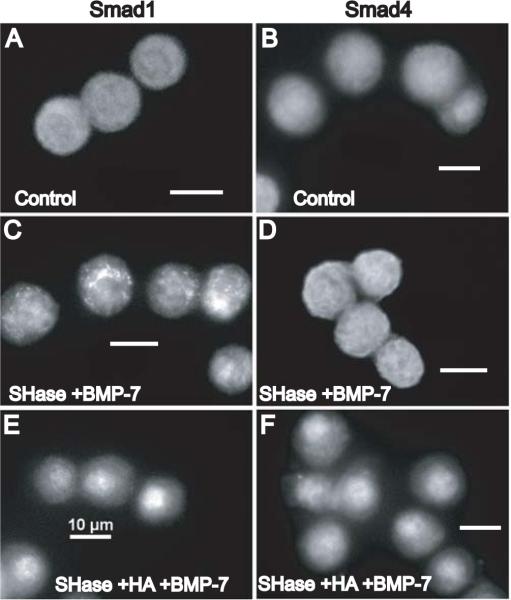

ADDITION OF HYALURONAN TO MATRIX-DEPLETED CHONDROCYTES RESTORES THE RESPONSES TO BMP-7

Attempted matrix repair may occur in early stages of osteoarthritis. Matrix-depleted chondrocytes were incubated for 2 h in the presence or absence of 100 μg/ml Healon to mimic initial matrix repair, and then treated with BMP-7 for 1 h. Untreated bovine articular chondrocytes exhibit diffuse cytoplasmic staining for both Smad1 (Fig. 4A) and Smad4 (Fig. 4B). Chondrocytes pre-treated with Streptomyces hyaluronidase followed by BMP-7 stimulation continued to exhibit diffuse cytoplasmic staining for Smad1 (Fig. 4C) and Smad4 (Fig. 4D). However, the addition of hyaluronan to matrix-depleted chondrocytes restored the nuclear translocation of Smad1 (Fig. 4E) and Smad4 (Fig. 4F) following stimulation with BMP-7. Thus, these results suggest that CD44 receptor occupancy with its ligand, hyaluronan, supports the functional participation of CD44 in the activation of Smads1/4 in the BMP-7 signal transduction pathway resulting in nuclear translocation of Smads1/4.

Fig. 4.

Addition of hyaluronan to matrix-depleted chondrocytes restores Smad1 and Smad4 nuclear translocation in response to BMP-7. Untreated chondrocytes exhibit diffuse cytoplasmic staining for Smad1 (A) and Smad4 (B). Chondrocytes, pre-treated with Streptomyces hyaluronidase to remove the pericellular matrix, continue to exhibit diffuse cytoplasmic staining for Smad1 after BMP-7 stimulation (C) and for Smad4 after BMP-7 stimulation (D). However, addition of high molecular mass hyaluronan for 2 hours to matrix-depleted chondrocytes restored the nuclear translocation of Smad1 (E) as well as the nuclear translocation of Smad4 (F) following stimulation with BMP-7. Scale bars equal 10 μm.

A morphometric analysis of the cellular distribution of Smad1, Smad2 and Smad4 in bovine articular chondrocytes determined the maximal pixel intensity at point values (arrows) or mean pixel intensity (rectangles) within regions of the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 1E and 1F.) This analysis (Table 1) indicated that strong immunostaining for nuclear Smad2 and Smad4 in response to TGF-β persisted even though chondrocytes were pre-treated with Streptomyces hyaluronidase, but that this enzymatic removal of the pericellular matrix reduced nuclear immunostaining of Smad1 and Smad4 in the BMP-7 treatment groups to that observed in untreated controls. The addition of exogenous hyaluronan to matrix-depleted chondrocytes restored the strong nuclear immunostaining for Smad1 and Smad4 in response to BMP-7 stimulation.

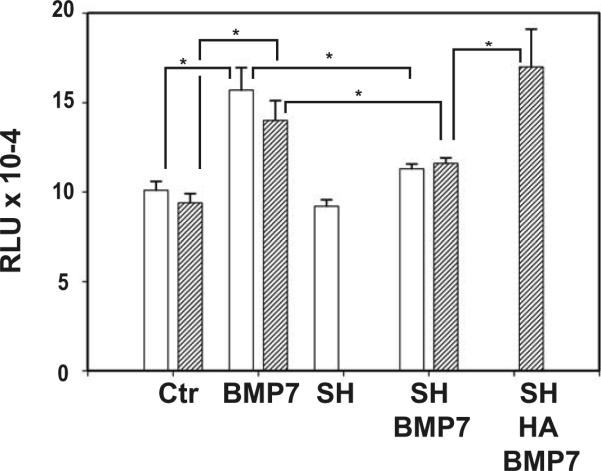

BMP-7 STIMULATION OF CD44 EXPRESSION

Since BMP-7 upregulates CD44 mRNA expression in articular chondrocytes, a 5'-deletion CD44 gene construct containing potential binding sites for Smad4 and Smad1 was generated, designated pCD44(499)-Luc. Bovine chondrocytes were transfected with pCD44(499)-Luc, then established in alginate bead cultures and incubated for 48 h. The transfected chondrocytes within the alginate beads were treated with BMP-7 with or without Streptomyces hyaluronidase pre-treatment (Fig. 5, open bars) to study whether matrix disruption would affect luciferase expression by this CD44 reporter construct in response to BMP-7. Stimulation of matrix-intact chondrocytes with BMP-7 for 1 h resulted in enhanced expression of luciferase. Treatment with Streptomyces hyaluronidase alone did not alter the basal activity; however following matrix disruption, BMP-7 treatment no longer resulted in enhanced luciferase activity. This suggests that disruption of hyaluronan-CD44 interactions reduces the response to BMP-7 stimulation.

Fig. 5.

BMP-7 stimulation of pCD44(499)-Luc in chondrocytes is matrix-dependent.

Open bars; the pCD44(499)-Luc-transfected chondrocytes were cultured and treated within alginate beads. Stimulation of matrix-intact chondrocytes with BMP-7 for 1 hour resulted in enhanced expression of luciferase as compared to non-treated controls (Ctr). Treatment with Streptomyces hyaluronidase alone did not alter the basal activity (SH); however following matrix disruption, BMP-7 treatment no longer resulted in enhanced luciferase activity (SH + BMP7). This suggests that disruption of hyaluronan-CD44 interactions reduces the response to BMP-7 stimulation.

Hatched bars; due to limited penetration of hyaluronan into the alginate beads, pCD44(499)-Luc transfected chondrocytes were released from the beads, pre-incubated with or without high molecular mass hyaluronan and then treated with BMP-7 for 1 hour. Stimulation of matrix-intact chondrocytes with BMP-7 resulted in enhanced expression of luciferase as compared to non-treated controls (Ctr). After pre-treatment with Streptomyces hyaluronidase followed by a 2 hour recovery in media, a reduced response to BMP-7 stimulation was still observed (SH + BMP7). However, the addition of exogenous hyaluronan to the matrix-depleted chondrocytes for 2 hour restored the BMP-7 response of increased luciferase activity (SH + HA + BMP7).

The relative luciferase units (RLU) values were normalized to total protein in the lysates obtained from three replicate experiments of all conditions; average RLU ± S.D. are shown. * P < 0.05 by t test.

To test if responsiveness to BMP-7 could be restored with restoration of hyaluronan-CD44 interactions, exogenous high molecular mass hyaluronan was added to matrix-depleted chondrocytes transfected with pCD44(499)-Luc. However, due to limited penetration of hyaluronan into the alginate beads, for hyaluronan add-back experiments, chondrocytes were released from the beads, pre-incubated with or without hyaluronan and then treated with BMP-7 for 1 h (Fig. 5, hatched bars). A reduced response to BMP-7 stimulation was still observed after pre-treatment with Streptomyces hyaluronidase followed by a 2 h recovery in media. However, the addition of exogenous hyaluronan to the matrix-depleted chondrocytes for 2 h restored the BMP-7 response of increased luciferase activity. This suggests that hyaluronan-CD44 interactions can promote Smad-dependent transcription following BMP-7 stimulation.

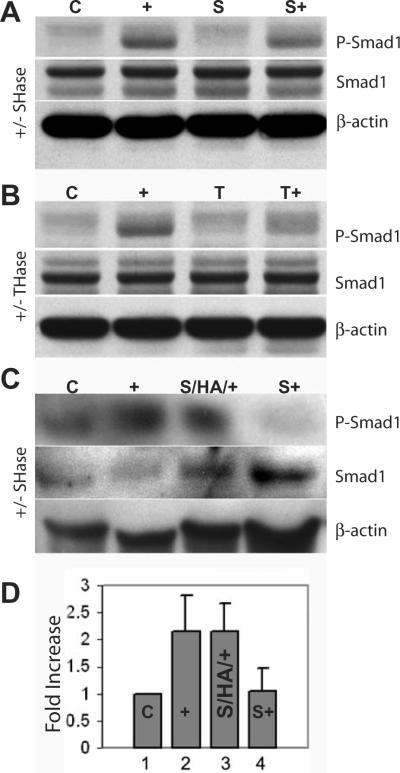

WESTERN BLOT ANALYSIS OF SMAD PHOSPHORYLATION

Signaling initiated by BMP-7 binding to its receptors includes Smad1 phosphorylation as detected studying matrix-intact bovine chondrocytes18. Disruption of hyaluronan-CD44 interactions via Streptomyces hyaluronidase treatment18 or testicular hyaluronidase treatment reduced Smad1 phosphorylation upon BMP-7 stimulation (Fig. 6). The addition of exogenous hyaluronan to matrix-depleted chondrocytes was studied to mimic matrix repair and determine whether Smad1 phosphorylation in response to BMP-7 stimulation would be restored. As shown in Figure 6C, after a pre-incubation of matrix-depleted chondrocytes for 2 h with hyaluronan prior to treatment with BMP-7, these cells exhibited strong signal for the phosphorylated Smad1 band. Setting the ratio of phosphoSmad1:total Smad1 in the control lysates to 1.00, this analysis showed Smad1 phosphorylation in response to BMP-7 in matrix-intact chondrocytes, its reduction following matrix depletion, and the restoration of Smad1 phosphorylation following hyaluronan add-back to matrix-depleted chondrocytes (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Addition of hyaluronan to matrix-depleted chondrocytes restores Smad1 phosphorylation in response to BMP-7.

A, B, C. Total cell lysates were prepared from chondrocytes and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting using an anti-phospho-Smad1 antibody (upper panel), an anti-Smad1 antibody to detect total Smad1 (middle) and an anti-β-actin antibody (lower panel). In each, lysates from control matrix-intact chondrocytes exhibited a weak band for phospho-Smad1 (C), but a stronger band was detected from chondrocytes stimulated by BMP-7 (+).

A. Chondrocytes were pre-treated with Streptomyces hyaluronidase (SHase) to remove the pericellular matrix, and then incubated for 2 hours in the absence (S) or presence (S+) of BMP-7. Smad1 phosphorylation was diminished in matrix-depleted chondrocytes.

B. Chondrocytes were pre-treated with testicular hyaluronidase (THase) to remove the pericellular matrix, and then incubated for 2 hours in the absence (T) or presence (T+) of BMP-7. Smad1 phosphorylation was diminished in matrix-depleted chondrocytes.

C. Streptomyces hyaluronidase (SHase) pre-treated chondrocytes were incubated in the presence (S/HA/+) or absence (S+) of exogenous hyaluronan prior to BMP-7 stimulation. The addition of hyaluronan restored the response to BMP-7 resulting in an increase in phosphoSmad1 (S/HA/+).

D. The band intensities for total Smad1 and phosphoSmad1 were normalized to that of β-actin from each lysate from three separate experiments. Setting the ratio of the band intensity for phosphoSmad1 to total Smad1 in the control (C) lysates to 1.00, the ratios were calculated for the other culture conditions and data are presented as fold-increase. Stimulation by BMP-7 of matrix-intact chondrocytes (+) or matrix-depleted chondrocytes following hyaluronan addback (S/HA/+) resulted in an increase in phosphoSmad1. Matrix-depleted chondrocytes did not exhibit the BMP-7 response of Smad1 phosphorylation (S+).

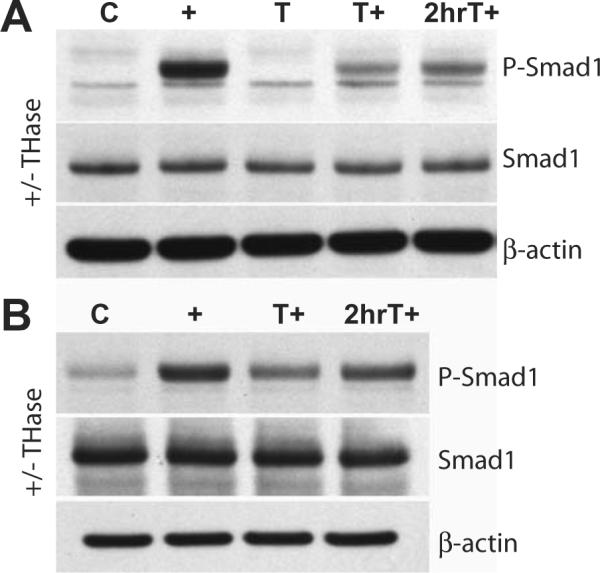

As an alternative to exogenous hyaluronan add-back, chondrocytes were transfected with full-length HAS2 in order to enhance endogenous hyaluronan synthesis. Primary chondrocytes or HAS2-transfected chondrocytes in monolayer culture were striped of matrix with testicular hyaluronidase and then stimulated directly with BMP-7 or incubated for 2 h for the re-growth of endogenous matrix prior to stimulation with BMP-7. When stimulated with BMP-7 directly following matrix depletion, both primary chondrocytes and HAS2-transfected chondrocytes showed reduced Smad1 phosphorylation (Fig. 7). Primary chondrocytes showed little recovery of the Smad1 phosphorylation response, but the HAS2-transfected chondrocyte cultures exhibited a recovery of BMP-7-induced Smad1 phosphorylation given two hours of incubation for endogenous matrix re-growth (Fig. 7). This suggests that matrix repair, especially enhanced matrix repair due to over-expression of HAS2, can restore BMP-7 responsiveness of chondrocytes.

Fig. 7.

Chondrocyte matrix re-growth following hyaluronidase treatment restores Smad1 phosphorylation in response to BMP-7.

As an alternative to exogenous hyaluronan add-back, (A) primary chondrocytes or (B) HAS2-transfected chondrocytes in monolayer culture for 48 hours were striped of matrix with testicular hyaluronidase (T) and then either stimulated directly with BMP-7 (T+) or incubated for 2 hours for the re-growth of endogenous matrix prior to stimulation with BMP-7 (2hrT+). Total cell lysates were prepared from chondrocytes and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting using an anti-phospho-Smad1 antibody (upper panel), an anti-Smad1 antibody to detect total Smad1 (middle) and an anti-β-actin antibody (lower panel).

(A) Matrix-intact cultures of primary chondrocytes exhibited Smad1 phosphorylation after BMP- 7 stimulation (+) compared to non-BMP-7-stimulated control cultures (C). Matrix-depleted chondrocytes stimulated with BMP-7 directly following enzymatic treatment showed a weak Smad1 phosphorylation response (T+). However, after two hours of incubation for endogenous matrix re-growth, primary chondrocytes exhibited a slightly enhanced response to BMP-7 stimulation (2hrT+)

(B) Matrix-intact cultures of HAS2-transfected chondrocytes exhibited increased Smad1 phosphorylation after BMP-7 stimulation (+) compared to non-BMP-7-stimulated control cultures (C). HAS2-transfected chondrocytes showed a weak Smad1 phosphorylation response when stimulated with BMP-7 directly following enzymatic treatment (T+) whereas after two hours of incubation for endogenous matrix re-growth, the HAS2-transfected chondrocytes exhibit a recovery of Smad1 phosphorylation after BMP-7 stimulation (2hrT+).

Discussion

CD44-hyaluronan interactions mediate a variety of cell behaviors, including proliferation, migration and matrix remodeling. Several studies suggest mechanisms by which the formation and/or uncoupling of hyaluronan-CD44 interactions may modulate cell behavior5,18,24-26 and these interactions may impact on cartilage homeostasis as chondrocytes progress through cycles of ECM degradation and attempted repair.

Native hyaluronan reduced mitogen-induced cell cycle progression by smooth muscle cells whereas fragmented hyaluronan was pro-mitogenic by opposite effects on cyclin D1 mRNA expression27. BMP-7 was shown to induce p21 transcription, requiring an intact Smad signaling pathway28. Thus as an alternative biological outcome, we determined p21 expression in matrix-depleted and matrix-intact human articular chondrocytes following BMP-7 stimulation (data not shown). Our initial results suggest that an intact pericellular matrix supports the increase in p21 mRNA following BMP-7 treatment of human chondrocytes whereas p21 mRNA expression was decreased after hyaluronidase treatment plus BMP-7 stimulation as compared to matrix-intact untreated controls. Thus matrix-depletion might enhance proliferation whereas endogenous BMP-7 signaling to maintain an intact pericellular matrix may promote the low proliferative phenotype of articular chondrocytes.

We previously reported the binding of Smad1 with CD44, supporting a functional link between the canonical BMP-7 signaling pathway and endogenous hyaluronan-CD44 interactions18. Hyaluronan-CD44 ligation may promote the presentation of Smad1 to the cytoplasmic domain of the BMP-7 receptor. Alternatively, unoccupied CD44 may sequester Smad1 in an inaccessible pool away from the BMP-7 receptor. Although data at this point do not refute either hypothesis, clearly the disruption of hyaluronan binding to CD44 resulted in diminished responses to BMP-7 while hyaluronan binding to chondrocytes augments the Smad1 phosphorylation that occurs in response to BMP-7 stimulation as well as the subsequent nuclear translocation of Smad1/Smad4. Linking the cytoplasmic domain of CD44 with the actin cytoskeleton through multiple protein interactions may stabilize and/or promote clustering of CD44 in the plasma membrane6, 29 and support efficient CD44-hyaluronan binding. Recently the structural motifs for radixin (FERM domain) binding to CD44 intracellular domain (ICD) were identified30. These authors proposed that the CD44 cytoplasmic tail bound to ERM proteins would still be able to bind to Smad1. They also confirmed our earlier suggestion18 that following proteolysis the cytosolic CD44 ICD together with Smad1 could cooperate with p300/CBP to regulate transcriptional activation. Thus the Smad1 signaling pathway may also be linked to the ICD-dependent pathway of CD44 signaling.

The bioavailability of TGF-β/BMPs is regulated by a variety of mechanisms. Other proteins have been shown to function in the presentation or sequestration of R-Smads13. These include SARA for Smad2/Smad3 in the TGF-β signaling pathway31 and endofin a scaffold protein for the Smad2/Smad4 complex in TGF-β signaling32 that also binds Smad1 enhancing its phosphorylation and signaling33. Soluble extracellular antagonists including noggin, follistatin and chordin bind directly to BMPs to block receptor interactions and endogenous BMP-7 regulates noggin and follistatin expression34. Binding of KCP (Kielin/Chordin-like Protein) increases the binding of BMP-7 to its receptor but KCP binding to TGF-β1 blocks Smad2 phosphorylation35. Matrix molecules including decorin and biglycan and cell surface proteoglycans are not dedicated modulators of TGF-β/BMP signaling, but also contribute to regulation of bioavailability36-38. However, the effective participation of CD44 in Smad1 signaling combines its binding to Smad1 modulated by hyaluronan binding.

Although BMPs and TGF-βs have overlapping anabolic activities and significant interplay, other results suggest a “division of labor” among the various members of the TGFβ/BMP superfamily39. Differences in the potency of BMPs or TGF-β to induce cartilage as well as differential stimulation of proteoglycans and other cartilage matrix components have been reported39,40. Alteration of the relative magnitude of these TGF-β and BMP signals can disturb cartilage homeostasis and induce differentiation or terminal maturation41. In our study, although matrix-depleted chondrocytes exhibited a poor response to BMP-7, these cells remained responsive TGF-β1. Matrix repair, enhanced by hyaluronan or increased expression of HAS2 restored the BMP-7 response. These results suggest that changes in hyaluronan-CD44 interactions may modulate specifically the cellular responsiveness to BMP-7 or other BMPs that signal through the Smad1-dependent canonical pathway thus distinguishing the effect of hyaluronan on the response of chondrocytes to members of the TGF superfamily. Hyaluronan may influence the morphogenetic gradient for BMPs and promote a robust activity perpetuated by a BMP-driven positive feedback loop, with BMP-7 stimulating CD44 and HAS2 synthesis, hyaluronan production and the BMP-7 response through the ligation of hyaluronan with CD44.

The effective local concentration of BMPs and TGF-βs is not merely the amount of the growth factor present, but depends upon ECM components, cell surface receptors and cytosolic signaling cascade molecules that modulate the ability of cells to respond. Subtle changes in the ECM can result in distinct changes in chondrocyte metabolism26,42,43. The underlying mechanism of the diminished response of osteoarthritic chondrocytes to local growth factors may explain, in part, the reduced capacity of these cells to maintain the critical balance of ECM synthesis and degradation7,8. The continuing progression of matrix degeneration would decrease the cell-matrix interactions, including cleavage and shedding of CD4429,44 that could result in a less robust response to BMP-7, thus promoting the downward spiral of osteoarthritis. Conversely, our data suggest that increased synthesis of hyaluronan by HAS2 in chondrocytes expressing CD44 would enhance the assembly and retention of a pericellular coat9,10 and, in turn, promote the chondrocyte response to BMP-7. Thus matrix repair that restores the ligation of hyaluronan with receptors on chondrocytes may restore signaling pathways and cartilage homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mary Goldring (Hospital for Special Surgery, New York) who provided the human immortalized chondrocytes (cell line C-28/I2) and Dr. Melanie A. Simpson (University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE) who provided the HAS-2 expression vector. We thank the donor families and the Gift of Hope Organ and Tissue Donor Network, Elmhurst, IL. The generosity and beneficence of the donor families for access to the human tissues used for the preliminary data in the Discussion section is greatly appreciated. We also thank Dr. Geraldine Chow for helpful discussions during this project. Our study was supported in part by NIH grants R01-AR39507 (to CBK) RO1-AR43384 (to WK) and P50-AR39239 and T32-AR0759 (to Rush University Medical Center).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hardingham TE, Fosang AJ. Proteoglycans: many forms and many functions. FASEB J. 1992;6:861–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knudson W, Knudson C. An update on hyaluronan and CD44 in cartilage. Current Opin Orthop. 2004;15:369–75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knudson CB, Knudson W. Hyaluronan-binding proteins in development, tissue homeostasis and disease. FASEB J. 1993;7:1233–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishida Y, Knudson CB, Nietfeld JJ, Margulis A, Knudson W. Antisense inhibition of hyaluronan synthase-2 in human articular chondrocytes inhibits proteoglycan retention and matrix assembly. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21893–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toole BP. Hyaluronan: from extracellular glue to pericellular cue. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:528–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turley EA, Noble PW, Bourguignon LY. Signaling properties of hyaluronan receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4589–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddi AH. Cartilage morphogenetic proteins: role in joint development, homoeostasis, and regeneration. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(Suppl 2):ii73–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.suppl_2.ii73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chubinskaya S, Kuettner KE. Regulation of osteogenic proteins by chondrocytes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:1323–40. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishida Y, Knudson CB, Kuettner KE, Knudson W. Osteogenic protein-1 promotes the synthesis and retention of extracellular matrix within bovine articular cartilage and chondrocyte cultures. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2000;8:127–36. doi: 10.1053/joca.1999.0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishida Y, Knudson CB, Eger W, Kuettner KE, Knudson W. Osteogenic protein-1 stimulates cell-associated matrix assembly by normal human articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:206–14. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<206::AID-ANR25>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flechtenmacher J, Huch K, Thonar EJMA, Mollenhauer J, Davies SR, Schmid TM, et al. Recombinant human osteogenic protein 1 is a potent stimulator of the synthesis of cartilage proteoglycans and collagens by human articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:478–88. doi: 10.1002/art.1780391117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenwald J, Groppe J, Gray P, Wiater E, Kwiatkowski W, Vale W, et al. The BMP7/ActRII extracellular domain complex provides new insights into the cooperative nature of receptor assembly. Mol Cell. 2003;11:605–17. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyazono K, Maeda S, Imamura T. BMP receptor signaling: transcriptional targets, regulation of signals, and signaling cross-talk. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:251–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macias-Silva M, Hoodless PA, Tang SJ, Buchwald M, Wrana JL. Specific activation of Smad1 signaling pathways by the BMP7 type I receptor, ALK2. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25628–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebisawa T, Tada K, Kitajima I, Tojo K, Sampath TK, Kawabata M, et al. Characterization of bone morphogenetic protein-6 signaling pathways in osteoblast differentiation. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:3519–27. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.20.3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gazzerro E, Canalis E. Bone morphogenetic proteins and their antagonists. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2006;7:51–65. doi: 10.1007/s11154-006-9000-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itoh S, ten Dijke P. Negative regulation of TGF-beta receptor/Smad signal transduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:176–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterson RS, Andhare RA, Rousche KT, Knudson W, Wang W, Grossfield JB, et al. CD44 modulates Smad1 activation in the BMP-7 signaling pathway. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:1081–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200402138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knudson CB, Nofal GA, Pamintuan L, Aguiar DJ. The chondrocyte pericellular matrix: a model for hyaluronan-mediated cell-matrix interactions. Biochem Soc Trans. 1999;27:142–7. doi: 10.1042/bst0270142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chow G, Knudson CB, Homandberg G, Knudson W. Increased expression of CD44 in bovine articular chondrocytes by catabolic cellular mediators. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27734–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maltzman JS, Carman JA, Monroe JG. Role of EGR1 in regulation of stimulus-dependent CD44 transcription in B lymphocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2283–94. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzgerald KA, O'Neill LA. Characterization of CD44 induction by IL-1: a critical role for Egr-1. J Immunol. 1999;162:4920–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson MA, Wilson CM, Furcht LT, Spicer AP, Oegema TR, Jr., McCarthy JB. Manipulation of Hyaluronan Synthase Expression in Prostate Adenocarcinoma Cells Alters Pericellular Matrix Retention and Adhesion to Bone Marrow Endothelial Cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10050–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohno S, Im HJ, Knudson CB, Knudson W. Hyaluronan oligosaccharide-induced activation of transcription factors in bovine articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:800–9. doi: 10.1002/art.20937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iacob S, Knudson CB. Hyaluronan fragments activate nitric oxide synthase and the production of nitric oxide by articular chondrocytes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:123–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohno S, Im HJ, Knudson CB, Knudson W. Hyaluronan oligosaccharides induce matrix metalloproteinase 13 via transcriptional activation of NFkappaB and p38 MAP kinase in articular chondrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17952–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602750200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kothapalli D, Flowers J, Xu T, Pure E, Assoian RK. Differential activation of ERK and Rac mediates the proliferative and anti-proliferative effects of hyaluronan and CD44. J Biol Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802934200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M802934200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pardali K, Kowanetz M, Heldin CH, Moustakas A. Smad pathway-specific transcriptional regulation of the cell cycle inhibitor p21(WAF1/Cip1) J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:260–72. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorne RF, Legg JW, Isacke CM. The role of the CD44 transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains in co-ordinating adhesive and signalling events. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:373–80. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mori T, Kitano K, Terawaki SI, Maesaki R, Fukami Y, Hakoshima T. Structural basis for CD44 recognition by ERM proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29602–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803606200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Runyan CE, Schnaper HW, Poncelet AC. The role of internalization in transforming growth factor beta1-induced Smad2 association with Smad anchor for receptor activation (SARA) and Smad2-dependent signaling in human mesangial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8300–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407939200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen YG, Wang Z, Ma J, Zhang L, Lu Z. Endofin, a FYVE domain protein, interacts with Smad4 and facilitates transforming growth factor-beta signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9688–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611704200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi W, Chang C, Nie S, Xie S, Wan M, Cao X. Endofin acts as a Smad anchor for receptor activation in BMP signaling. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1216–24. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye L, Lewis-Russell JM, Kynaston H, Jiang WG. Endogenous bone morphogenetic protein-7 controls the motility of prostate cancer cells through regulation of bone morphogenetic protein antagonists. J Urol. 2007;178:1086–91. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin J, Patel SR, Wang M, Dressler GR. The cysteine-rich domain protein KCP is a suppressor of transforming growth factor beta/activin signaling in renal epithelia. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4577–85. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02127-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takada T, Katagiri T, Ifuku M, Morimura N, Kobayashi M, Hasegawa K, et al. Sulfated polysaccharides enhance the biological activities of bone morphogenetic proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43229–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300937200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irie A, Habuchi H, Kimata K, Sanai Y. Heparan sulfate is required for bone morphogenetic protein-7 signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;308:858–65. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01500-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paine-Saunders S, Viviano BL, Economides AN, Saunders S. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans retain Noggin at the cell surface: a potential mechanism for shaping bone morphogenetic protein gradients. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2089–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109151200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niikura T, A. Hari Reddi AH. Differential regulation of lubricin/superficial zone protein by transforming growth factor beta/bone morphogenetic protein superfamily members in articular chondrocytes and synoviocytes. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2007;56:2312–21. doi: 10.1002/art.22659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shintani N, Hunziker EB. Chondrogenic differentiation of bovine synovium: bone morphogenetic proteins 2 and 7 and transforming growth factor beta1 induce the formation of different types of cartilaginous tissue. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1869–79. doi: 10.1002/art.22701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li T-F, Darowish M, Zuscik MJ, Chen D, Schwarz EM, Rosier RN, et al. Smad3-Deficient Chondrocytes Have Enhanced BMP Signaling and Accelerated Differentiation. J Bone Mineral Res. 2006;21:4–16. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Homandberg G, Meyers R, Xie DL. Fibronectin fragments cause chondrolysis of bovine articular cartilage slices in culture. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knudson W, Casey B, Nishida Y, Eger W, Kuettner KE, Knudson CB. Hyaluronan oligosaccharides perturb cartilage matrix homeostasis and induce chondrogenic chondrolysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1165–74. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200005)43:5<1165::AID-ANR27>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagano O, Saya H. Mechanism and biological significance of CD44 cleavage. Cancer Science. 2004;95:930–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]