Abstract

Objective

To estimate the cost to the health system of obstetric complications due to female genital mutilation (FGM) in six African countries.

Methods

A multistate model depicted six cohorts of 100 000 15-year-old girls who survived until the age of 45 years. Cohort members were modelled to have various degrees of FGM, to undergo childbirth according to each country’s mortality and fertility statistics, and to have medically attended deliveries at the frequency observed in the relevant country. The risk of obstetric complications was estimated based on a 2006 study of 28 393 women. The costs of each complication were estimated in purchasing power parity dollars (I$) for 2008 and discounted at 3%. The model also tracked life years lost owing to fatal obstetric haemorrhage. Multivariate sensitivity analysis was used to estimate the uncertainty around the findings.

Findings

The annual costs of FGM-related obstetric complications in the six African countries studied amounted to I$ 3.7 million and ranged from 0.1 to 1% of government spending on health for women aged 15–45 years. In the current population of 2.8 million 15-year-old women in the six African countries, a loss of 130 000 life years is expected owing to FGM’s association with obstetric haemorrhage. This is equivalent to losing half a month from each lifespan.

Conclusion

Beyond the immense psychological trauma it entails, FGM imposes large financial costs and loss of life. The cost of government efforts to prevent FGM will be offset by savings from preventing obstetric complications.

ملخص

الغرض

تقدير التكلفة التي يتحملها النظام الصحي بسبب المضاعفات التوليدية الناجمة عن تشويه الأعضاء التناسلية للنساء في ستة بلدان أفريقية.

الطريقة

اختار الباحثون نموذجاً متعدد البلدان ليصف ست مجموعات أترابية يتكون كل منها من 100 ألف فتاة في عمر 15 سنة عشن حتى وصلن عمر 45 سنة. وضعت عضوات المجموعات الأترابية في نماذج تمثل مختلف درجات تشوه الأعضاء التناسلية، وأجرين ولادات تتوافق مع إحصائيات الوفيات والخصوبة في كل بلد، مع حصولهن على ولادات تحت إشراف طبي بنفس التواتر المشاهد في كل بلد. وقدر الباحثون احتمال الخطر استناداً إلى دراسة أجريت عام 2006 شملت 28393 امرأة. وجرى تقدير تكاليف كل مضاعفة من المضاعفات حسب القدرة الشرائية المكافئة للدولار لعام 2008 وخُصم منها 3%. كما اتبع النموذج سنوات العمر الضائعة بسبب النزف التوليدي الذي أدى إلى الوفاة، وأجرى الباحثون تحليلاً للحساسية متعدد المتغيرات لتقدير عدم اليقين المحيط بالموجودات.

الموجودات

بلغت التكاليف السنوية بسبب المضاعفات التوليدية المتعلقة بتشويه الأعضاء التناسلية للنساء في ست بلدان أفريقية 3.7 مليون دولار مكافئ، وتراوحت التكاليف السنوية بين 0.1 إلى 1% من الإنفاق الحكومي على صحة النساء في عمر 15-45 سنة. وفي السكان الحاليين وعددهم 2.8 مليون امرأة في عمر 15 سنة في ست بلدان أفريقية، يتوقع خسارة 130 ألف سنة من العمر بسبب ارتباط تشوه الأعضاء التناسلية للنساء بالنزف التوليدي. وهذا يكافئ خسارة نصف شهر من مدى حياة كل امرأة.

الاستنتاج

بجانب الصدمة النفسية الشديدة الوطأة التي تنجم عن تشويه الأعضاء التناسلية للمرأة، فإن هذا العمل يؤدي إلى تكاليف مالية وخسائر في الأرواح. وإن تكاليف الجهود التي تبذلها الحكومات لمنع تشويه الأعضاء التناسلية للنساء سيجري تعويضه عن طريق اتقاء المضاعفات التوليدية.

Résumé

Objectif

Estimer le coût pour les systèmes de santés des complications obstétricales des mutilations génitales féminines (MGF) dans six pays d'Afrique.

Méthodes

Un modèle multi-états a permis de décrire six cohortes de 100 000 jeunes filles de 15 ans au départ, destinées à survivre jusqu'à l'âge de 45 ans. Les femmes composant les cohortes ont été modélisées comme subissant divers degrés de MGF, comme donnant naissance à des enfants conformément aux statistiques de mortalité et de fécondité de chacun des pays et comme bénéficiant d'une assistance médicale à l'accouchement selon la fréquence observée dans leur pays. Le risque de complication obstétricale a été estimé à partir d'une étude de 2006 portant sur 28 393 femmes. Les coûts pour chaque complication ont été estimés en dollars de parité de pouvoir d'achat (I$) pour 2008 et ajustés par application d'un facteur de 3 %. Le modèle a également déterminé les années de vie perdues du fait des hémorragies obstétricales mortelles. Les auteurs ont fait appel à une analyse de sensibilité multivariée pour estimer l'incertitude entachant les résultats.

Résultats

Les coûts annuels des complications obstétricales liées aux MGF dans les six pays africains étudiés se montaient à I$ 3,7 millions et représentaient 0,1 à 1 % des dépenses publiques pour la santé des femmes de 15 à 45 ans. Parmi les 2,8 millions de jeunes filles actuellement âgées de 15 ans dans ces six pays africains, on s'attend à une perte de 130 000 années de vie du fait des hémorragies obstétricales associées aux FGM, ce qui équivaut à amputer chaque durée de vie d'un demi-mois.

Conclusion

Au-delà des énormes traumatismes psychologiques qu'elles entraînent, les MGF font supporter à la société des pertes de vie et des coûts financiers importants. Le coût des efforts des Etats pour prévenir ces mutilations sera compensé par les économies résultant des complications obstétricales évitées.

Resumen

Objetivo

Estimar el costo para el sistema de salud de las complicaciones obstétricas causadas por la mutilación genital femenina (MGF) en seis países africanos.

Métodos

Mediante un modelo multiestado se representaron seis cohortes de 100 000 mujeres de 15 años que vivirían hasta los 45 años. En el modelo se contemplaba que las mujeres tendrían diversos grados de MGF, darían a luz de acuerdo con las estadísticas de mortalidad y fecundidad de cada país, y disfrutarían de asistencia médica en el parto con la frecuencia observada en el país en cuestión. El riesgo de complicaciones obstétricas se calculó tomando como base un estudio de 2006 que abarcó 28 393 mujeres. Los costos de cada complicación se estimaron en dólares internacionales (I$) basados en la paridad de poder adquisitivo de 2008, con un descuento del 3%. El modelo determinó además los años de vida perdidos por hemorragia mortal en el parto. Se realizó un análisis de sensibilidad multifactorial para estimar la incertidumbre de los resultados.

Resultados

El costo anual de las complicaciones obstétricas relacionadas con la MGF en los seis países africanos estudiados ascendió a I$ 3,7 millones y varió entre el 0,1% y el 1% del gasto público en salud correspondiente a las mujeres de 15-45 años. En la población de 2,8 millones de mujeres de 15 años que actualmente hay en esos seis países africanos, cabe prever por tanto una pérdida de 130 000 años de vida como consecuencia de la asociación de la MGF a hemorragias obstétricas, lo que equivale a un recorte de medio mes de la esperanza de vida.

Conclusión

Además del enorme trauma psicológico que entraña, la MGF acarrea grandes pérdidas económicas y de vidas. El costo de las actividades que emprendan los poderes públicos para prevenir la MGF se verá compensado por los ahorros logrados al evitar numerosas complicaciones obstétricas.

Introduction

The term “female genital mutilation” (FGM) denotes any procedure involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, as well as injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that between 100 and 140 million girls and women worldwide are presently living with FGM,1 and every year about three million girls are at risk.1,2 FGM is a fundamental violation of human rights. It is not only a severe form of discrimination against women, but also a violation of the rights of girls, on whom it is most commonly performed.1 FGM violates the right to health and to freedom from torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment and, in some cases, even the right to life.1 As a result, support for the abandonment of FGM can be found in numerous international and regional human rights treaties and consensus documents.1

FGM carries serious health consequences both for the girl or woman who undergoes the procedure and for her offspring. The procedure can lead to direct medical complications. In a study of women in Nigeria who had FGM, the most common of these were severe pain and bleeding.3 Infection also poses an immediate risk.1,4,5 Long-term health effects include psychological1,6 and psychosexual1,7 trauma, infertility,1,8 susceptibility to bacterial vaginosis and genital herpes,1,9 and obstetric complications, including perinatal death.1,10–12

This study focuses specifically on the medical costs associated with the obstetric complications of FGM. Prior studies have shown higher rates of Caesarean section, postpartum haemorrhage, prolonged hospitalization and perinatal death among women who have suffered FGM.10 Yet these obstetric complications account for only a small portion of the overall health impact of FGM in a population, and their financial costs are merely one among the many costs associated with FGM. However, when the financial burden that FGM imposes on the health system is measured, it becomes obvious that caring for women who have undergone this procedure imposes an even greater economic burden and that the cost of efforts to prevent FGM can be wholly or partially offset by the savings generated when complications are prevented. The objective of this paper is to build on prior estimates of the obstetric risks linked to FGM so as to estimate how much FGM-related obstetric complications cost the health-care system and society.

A large WHO study quantifying the relative risk of obstetric complications among African women by type of FGM made it possible to carry out this cost study.10 In the WHO study, which was conducted from November 2001 to March 2003 in 28 obstetric centres in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal and the Sudan, women and their neonates were prospectively followed for adverse outcomes from admission before labour or in early labour until discharge. The study was limited to 28 393 women who had a singleton delivery. Women’s FGM status was determined by direct examination of the external genitalia and in accordance with WHO’s four-category classification of FGM (Box 1). The relative risks of adverse maternal and infant health outcomes for each type of FGM (with no FGM as the reference category) were also estimated. These outcomes included Caesarean section, haemorrhage (postpartum blood loss ≥ 500 ml), extended maternal hospital stay (≥ 3 days), low birth weight (< 2500 g), resuscitated infant, and inpatient perinatal death. With the exception of episiotomy, our cost analysis was based on the frequency and relative risk of each complication for each type of FGM as reported in the published WHO study.

Box 1. Types of female genital mutilation as defined by the World Health Organization.

Type 1

Excision of the prepuce, with or without total or partial excision of the clitoris.

Type 2

Excision of the clitoris with partial or total excision of the labia minora.

Type 3

Total or partial excision of the external genitalia and stitching or narrowing of the vaginal opening (infibulation).

Type 4

Unclassified, which includes pricking, piercing or incising the clitoris and/or labia; stretching the clitoris and/or labia; cauterizating the clitoris and surrounding tissue; scraping the tissue surrounding the opening of the vagina (angurya cuts) or cutting the vagina (gishiri cuts); introducing corrosive substances or herbs into the vagina to cause bleeding or to tighten or narrow it; and any other procedure that can be included in the definition of FGM noted above.

FGM, female genital mutilation.

Methods

Multistate model

The model created six simulated cohorts of 100 000 women for each of the six African countries previously mentioned. In the model, the survival and birth history of each woman from age 15 to 45 years was constructed by applying the relevant fertility13 and mortality14 rates for each country. With each birth, the members of the cohort were programmed to seek formal obstetric care with a likelihood consistent with the most recent observations from Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data for the study countries (Appendix A, available at: http://sites.google.com/site/fgmappendix/appendix-1).

Each of the six cohorts was followed under four different FGM scenarios: no FGM, all FGM–1, all FGM–2 and all FGM–3. The respective FGM categories were assigned to every woman at age 15 and retained for life. In each run of the model, each woman’s risks of suffering complications depended on her FGM status and on her choice to have or not have a medically attended delivery (Table 1). Since this study was a secondary analysis of anonymous data and did not involve human subjects, it was exempted from review board approval by the Johns Hopkins University internal review board.

Table 1. Prevalence of obstetric outcomes, by type of female genital mutilation, in a modelled cohort of women of reproductive age (15–45 years) in six African countriesa.

| Parameter | Mean/median | 95% CI | Assumed distributionb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caesarean section prevalence (FGM–0)c | 0.07 | Beta | |

| Caesarean section RR | |||

| FGM–1d | 1.03 | 0.88–1.21 | Truncated normal of log(RR) (−2.5, 2.5) |

| FGM–2e | 1.29 | 1.09–1.52 | |

| FGM–3f | 1.31 | 1.01–1.70 | |

| Haemorrhage prevalence (FGM–0) | 0.06 | Beta | |

| Haemorrhage RR | |||

| FGM–1 | 1.03 | 0.87–1.21 | Truncated normal of log(RR) (−2.5, 2.5) |

| FGM–2 | 1.21 | 1.01–1.43 | |

| FGM–3 | 1.69 | 1.34–2.12 | |

| Inpatient stay prevalence (FGM–0) | 0.06 | Beta | |

| Inpatient stay RR | |||

| FGM–1 | 1.15 | 0.97–1.35 | Truncated normal of log(RR) (−2.5, 2.5) |

| FGM–2 | 1.51 | 1.29–1.76 | |

| FGM–3 | 1.98 | 1.54–2.54 | |

| Inpatient perinatal death prevalence (FGM–0) | 0.04 | Beta | |

| Inpatient perinatal death RR | |||

| FGM–1 | 1.15 | 0.94–1.41 | Truncated normal of log(RR) (−2.5, 2.5) |

| FGM–2 | 1.32 | 1.08–1.62 | |

| FGM–3 | 1.55 | 1.12–2.16 | |

| Resuscitated infant prevalence (FGM–0) | 0.08 | Beta | |

| Resuscitated infant RR | |||

| FGM–1 | 1.11 | 0.95–1.28 | Truncated normal of log(RR) (−2.5, 2.5) |

| FGM–2 | 1.28 | 1.10–1.49 | |

| FGM–3 | 1.66 | 1.31–2.10 | |

| Episiotomy prevalence (FGM–0) | 0.29 | Beta | |

| Episiotomy RR | |||

| FGM–1 | 1.61 | 1.46–1.78 | Truncated normal of log(RR) (−2.5, 2.5) except FGM3 (−2.9, 2.9) |

| FGM–2 | 1.99 | 2.20–1.81 | |

| FGM–3 | 9.87 | 11.29–8.64 |

CI, confidence interval; FGM, female genital mutilation; RR, relative risk.

a Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal and the Sudan.

b Beta distributions were set such that the most likely value occurred slightly below the mean, and the maximum value was set at 0.10 to 0.24 for outcomes other than episiotomy.

c No FGM.

d Excision of the prepuce with or without total or partial excision of the entire clitoris.

e Excision of the clitoris with partial or total excision of the labia minora.

f Complete or partial excision of the external genitalia and stitching or narrowing of the vaginal opening (infibulation).

Based on data from study by the World Health Organization.14

Model outcomes

We calculated the unit costs associated with Caesarean section, maternal haemorrhage, extended maternal hospital stay, infant resuscitation, inpatient perinatal death and episiotomy. (Some suggested that haemorrhage after FGM can be perineal rather than uterine and thus more easy to manage. However, a reanalysis of the WHO data confirmed that most haemorrhage among the women sampled, regardless of FGM type, was caused by an atonic uterus.) For each type of FGM, the relative risk of the first five outcomes was taken from overall risk calculations for all six African countries combined, as given in the aforementioned WHO study. Episiotomy was the only outcome for which the risk was recalculated for each FGM type, since the WHO study presented the relative risk of episiotomy separately for primiparous and multiparous women, rather than for both combined. We estimated the risk of episiotomy by FGM type for all women by reanalysing the WHO data set.

The baseline prevalence of each adverse outcome in women without FGM was modelled with a set of beta distributions, and the log relative risks associated with FGM type were modelled with normal distributions drawn from the WHO study. Outputs included the event counts of each obstetric complication, years of life lost, and differences in discounted costs and discounted life years between a given FGM type and no FGM. The model was run with @RISK version 4.5 (Palisade Corporation, Newfield, NY, USA).

Costs

The model adopts the perspective of the health system and assumes that only medically attended deliveries are likely to impose monetary health system costs. The probability of having an attended delivery was based on country-specific DHS estimates of delivery attendance by a physician in a given country. Using DHS data, we tried to determine if having an attended delivery depended on FGM status but found no statistically significant differences by FGM status for any country except Nigeria.

All costs in this analysis are presented in international (purchasing power parity) dollars (I$), which adjust for the cost of living in each country. The costs associated with Caesarean section and haemorrhage were estimated from the Lancet Neonatal Survival Series and the BMJ CHOICE Series.15,16 For all countries, we estimated the cost of a Caesarean section and a blood transfusion for haemorrhage to be I$ 36.40 and I$ 29.79, respectively.15,16 Country-specific costs per bed day were estimated to be I$ 2.98 for Burkina Faso, I$ 3.71 for Ghana, I$ 4.82 for Kenya, I$ 5.38 for Nigeria, I$ 6.73 for Senegal and I$ 2.69 for the Sudan, based on estimates provided by Adam et al.17

Years of life lost

Years of life lost were calculated for women who died from haemorrhage. We took the case fatality rate of 1.7% (95% confidence interval, CI: 1.2–2.5) that was found among women who experienced a blood loss ≥ 500 ml in the WHO study and applied it in our simulation to attended deliveries. We assumed conservatively that the rate for unattended peripartum haemorrhage patients would be three times higher, or 5.1% (95% CI: 3.6–7.5). These numbers are consistent with those in previous studies.18,19 Life expectancy between the ages of 15 and 45 years was estimated based on WHO life table14 data for women in each country.

The model was constructed for women of reproductive age with a 30-year time horizon. Women entered the model at 15 years of age and exited upon turning 46 years old. Costs and life years were discounted by 3% per annum, so that the estimated lifetime savings from investing to prevent FGM today are equivalent to the present value of future savings.

Results

Table 2 shows the estimated years of life lost and obstetric costs associated with every new case of FGM, as well as the expected cost increments and life year decrements if each type of FGM were imposed on a 15-year-old girl (relative to no FGM). The table shows that, on average, a girl of 15 years who undergoes FGM–3 will lose nearly one-fourth of a year of life and impose on the medical system a cost of I$ 5.82 over her lifetime. Clearly, FGM–3 is both detrimental to health and a waste of money. The other types of FGM also reduce survival and lead to monetary losses over each woman’s lifespan, but to a lesser extent.

Table 2. Incidence-based estimates of costs and years of life lost per incident case of female genital mutilation, by type, in a modelled cohort of women of reproductive age (15–45 years) in six African countries.

| Country | FGM–3 |

FGM–2 |

FGM–1 |

Weighted averageb |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YLLa | Cost (I$) | YLL | Cost (I$) | YLL | Cost (I$) | YLL | Cost (I$) | ||||

| Burkina Faso | 0.31 | 3.81 | 0.09 | 2.91 | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 2.34 | |||

| Ghana | 0.19 | 4.30 | 0.06 | 2.13 | 0.01 | 0.37 | 0.05 | 1.70 | |||

| Kenya | 0.21 | 7.34 | 0.06 | 2.92 | 0.01 | 0.61 | 0.07 | 2.86 | |||

| Nigeria | 0.27 | 4.04 | 0.09 | 2.35 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.70 | |||

| Senegal | 0.26 | 4.13 | 0.08 | 2.49 | 0.01 | 0.40 | 0.06 | 1.86 | |||

| Sudan | 0.23 | 5.81 | 0.07 | 2.56 | 0.01 | 0.49 | 0.21 | 5.33 | |||

| Weighted averageb | 0.23 | 5.82 | 0.08 | 2.50 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 1.71 | |||

FGM, female genital mutilation; I$, international (purchasing power parity) dollars; YLL, years of life lost.

a All losses are estimated relative to a baseline of no FGM.

b Weighted by estimated population of women with corresponding FGM type in each country.

The losses of life and money are different in each country because of differences in fertility rates and in the proportion of medically attended deliveries. Women who have more deliveries are more exposed to the risk of dying and of suffering complications. Countries that have achieved higher rates of medically attended deliveries also incur higher medical costs because of the complications associated with such deliveries. However, the model should not be interpreted to mean that the rate of attended deliveries should be reduced to lower the obstetric costs of FGM, but rather the opposite. Because deaths from complications are more common when births take place at home, reducing attended deliveries would result in higher death rates.

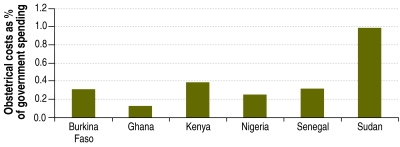

Table 3 shows the estimated annual medical costs for the entire population of women with FGM. The 53 million African women who live in the six countries studied represent a total of I$ 3.7 million in medical costs for the management of the obstetric complications linked to FGM, equivalent to between 0.1% and 1% of total government health spending on women of reproductive age (Fig. 1). Table 4 shows the estimated future loss of life attributable to FGM-related obstetric haemorrhage. The current population of 2.8 million 15-years-old girls in the six African countries studied will lose approximately 130 000 years of life as a result of the FGM procedures that will be performed over the next 12 months.

Table 3. Prevalence-based estimates of costs per prevalent case of female genital mutilation, by type, in a modelled cohort of women of reproductive age in six African countries.

| Country | FGM type | No. of cases | Annual FGM-related cost |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per FGM case (I$) | Total (I$) | As per cent of public health spending on women aged 15–45 yearsa | |||

| Burkina Faso | 0 | 547 558 | Reference | Reference | |

| 1 | 640 374 | 0.02 | 13 458 | ||

| 2 | 1 267 906 | 0.15 | 193 622 | ||

| 3 | 355 504 | 0.20 | 71 348 | ||

| All | 2 811 343 | 278 428 | 0.309 | ||

| Ghana | 0 | 3 133 331 | Reference | Reference | |

| 1 | 598 854 | 0.02 | 12 022 | ||

| 2 | 1 470 841 | 0.11 | 163 334 | ||

| 3 | 55 984 | 0.22 | 12 348 | ||

| All | 5 259 009 | 187 704 | 0.115 | ||

| Kenya | 0 | 3 299 611 | Reference | Reference | |

| 1 | 1 697 896 | 0.03 | 57 125 | ||

| 2 | 2 357 426 | 0.16 | 380 133 | ||

| 3 | 824 412 | 0.40 | 329 557 | ||

| All | 8 179 346 | 766 815 | 0.375 | ||

| Nigeria | 0 | 3 418 855 | Reference | Reference | |

| 1 | 17 829 912 | 0.00 | 15 732 | ||

| 2 | 6 932 973 | 0.12 | 851 480 | ||

| 3 | 216 986 | 0.21 | 46 173 | ||

| All | 28 398 726 | 913 385 | 0.247 | ||

| Senegal | 0 | 604 892 | Reference | Reference | |

| 1 | 690 716 | 0.02 | 12 518 | ||

| 2 | 1 526 673 | 0.13 | 193 066 | ||

| 3 | 23 932 | 0.21 | 5 045 | ||

| All | 2 846 213 | 210 629 | 0.308 | ||

| Sudan | 0 | 1 065 508 | Reference | Reference | |

| 1 | 267 977 | 0.02 | 6 688 | ||

| 2 | 296 774 | 0.13 | 38 540 | ||

| 3 | 4 370 024 | 0.30 | 1 307 444 | ||

| All | 6 000 284 | 1 352 672 | 0.980 | ||

| Total | 53 494 921 | 3 709 632 | |||

FGM, female genital mutilation; I$, international (purchasing power parity) dollars.

a Based on annual per capita government health spending as of 2003 in I$ from The world health report 2006 – working together for health.

Fig. 1.

Annual obstetrical costs related to female genital mutilation as a percentage of all government health spending on women aged 15–49 years

Table 4. Future years of life lost as a result of incident female genital mutilation cases for the 15-year-old population in six African countries.

| Country | FGM type | No. of women aged 15 yearsa | FGM prevalence in women aged < 20 years | No. of women aged 15 years, by FGM type | Future YLL per incident caseb | Future YLL for current female population aged 15 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burkina Faso | 0 | 148 400 | 0.227 | 33 746 | Reference | Reference |

| 1 | 0.256 | 37 946 | 0.01 | 379 | ||

| 2 | 0.391 | 57 965 | 0.09 | 5 217 | ||

| 3 | 0.126 | 18 728 | 0.31 | 5 806 | ||

| All | 11 402 | |||||

| Ghana | 0 | 245 600 | 0.686 | 168 555 | Reference | Reference |

| 1 | 0.074 | 18 199 | 0.01 | 182 | ||

| 2 | 0.222 | 54 572 | 0.06 | 3 274 | ||

| 3 | 0.017 | 4 273 | 0.19 | 812 | ||

| All | 4 268 | |||||

| Kenya | 0 | 418 400 | 0.431 | 180 498 | Reference | Reference |

| 1 | 0.156 | 65 061 | 0.01 | 651 | ||

| 2 | 0.273 | 114 265 | 0.06 | 6 856 | ||

| 3 | 0.140 | 58 618 | 0.21 | 12 310 | ||

| All | 19 816 | |||||

| Nigeria | 0 | 1 448 400 | 0.138 | 199 590 | Reference | Reference |

| 1 | 0.764 | 1 107 157 | 0.02 | 22 143 | ||

| 2 | 0.096 | 138 467 | 0.09 | 12 462 | ||

| 3 | 0.002 | 3 186 | 0.27 | 860 | ||

| All | 35 466 | |||||

| Senegal | 0 | 135 000 | 0.104 | 14 081 | Reference | Reference |

| 1 | 0.254 | 34 290 | 0.01 | 343 | ||

| 2 | 0.623 | 84 146 | 0.08 | 6 732 | ||

| 3 | 0.018 | 2 484 | 0.26 | 646 | ||

| All | 7 720 | |||||

| Sudan | 0 | 374 400 | 0.323 | 120 856 | Reference | Reference |

| 1 | 0.066 | 24 710 | 0.01 | 247 | ||

| 2 | 0.047 | 17 709 | 0.07 | 1 240 | ||

| 3 | 0.564 | 211 087 | 0.23 | 48 550 | ||

| All | 50 037 | |||||

| Total | 2 770 200 | 128 709 |

FGM, female genital mutilation; YLL, years of life lost.

a From United Nations life table for 2005.13

b Heterogeneity between countries in future years of life lost per incident case of FGM is due to differences between countries in the age-specific fertility rate and life expectancy.

Multivariate sensitivity analysis, shown in Appendix A, measures the degree of uncertainty surrounding our central finding that FGM imposes an economic burden on the health system. The proportion of runs in which FGM led to either higher costs, years of life lost or both was 77%, 85% and 93% for FGM–1, –2 and –3, respectively. Thus, we can be fairly confident that every new girl subjected to FGM represents a future stream of preventable obstetric costs and/or a future death from obstetric complications.

Discussion

FGM violates human rights. It is impossible to say how much society should spend to prevent it, but as shown by the results of our study, any money spent on preventing FGM would be partially offset by savings to the health system. Indeed, if the health system were to spend as much as I$ 5.82 per FGM–3 prevented or I$ 2.50 per FGM–2 prevented, the value of avoided obstetric complications would entirely offset the costs of prevention.

An estimated $23 million or more were spent by bilateral, multilateral and private foundation donors in 2007 on activites surrounding the prevention of FGM.20 However, the cost-effectiveness of such spending per case prevented is unknown. Typically, interventions for the prevention of FGM take the form of community-based programmes, media outreach and advocacy and often target religious leaders and excisors.20

Limitations

This study did not address the effects of FGM on a woman’s mental health or any of the medical complications stemming from the initial procedure, namely pain, bleeding and infection.1,3–5 These complications are described elsewhere. In Egypt, Elnashar & Abdelhady found that circumcised women had significantly higher rates of psychological problems than women who were not circumcised.21 Others have also found a higher prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder6 and sexual health problems among circumcised women.1,21 We were unable to include the immediate complications of FGM in our model for lack of quantitative estimates of their frequency.

Our data were limited to a few health centres in each of six countries that participated in an international study, and this could have biased our results. However, we used cluster-specific random effects when possible to produce the best estimates. We may have also over-counted some obstetric costs related to FGM because the cost of some bed days is usually included in the cost of a Caesarean section. It is also possible that some of the estimated costs are paid out of pocket by the families of the women concerned rather than by the health system.

Our analysis may have underestimated the total costs of FGM to the health system because it did not include the treatment of post-delivery complications in women who delivered at home. Costs to the health system are likely to increase in future years as access to health care increases in the poor and rural areas of these countries and a greater percentage of women deliver in health facilities. The estimated costs of treating obstetric complications within the health system may be inaccurate as well, since some costs are extrapolations and thus not country-specific and even those that are were based on assumptions that may not be valid for all parts of the country.

Despite the large size of the WHO study sample, the CIs for many of the parameters of interest remain wide. Additional epidemiological research could narrow the CIs around the known parameters. A further limitation of our study, which applies to virtually all cost studies built on models, is the use of multiple data sources to support the estimates.

Conclusion

Civil society should give the highest priority to addressing the human rights violation inherent in FGM. However, measures to address the problem require financing. Efforts to combat FGM have been traditionally underfunded, but as shown by the results of this study, African health ministries that invest in curbing the practice of FGM are likely to recover a large portion of the investment by saving money from prevented obstetric complications. Societies would also benefit from other reduced costs not measured here, including the costs of treating FGM-related psychological and sexual health problems.

Acknowledgements

The FGM Cost Study Group is composed of Taghreed Adam, Heli Bathija, Dale Huntington and Elise Johansen from the World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland; David Bishai and Yung-Ting Bonnenfant from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA; and Manal Darwish from the Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt. We thank Paul van Look and other reviewers at WHO for their helpful comments on the draft manuscript.

Funding:

The funding source for this study was WHO, and WHO scientists were involved in the writing and decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Eliminating female genital mutilation: an interagency statement Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoder PS, Abderrahim N, Zhuzhuni A. Female genital cutting in the demographic and health surveys: a critical and comparative analysis Calverton, MD: Macro International, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dare FO, Oboro VO, Fadiora SO, Orji EO, Sule-Odu AO, Olabode TO. Female genital mutilation: an analysis of 522 cases in South-Western Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:281–3. doi: 10.1080/01443610410001660850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almroth L, Bedri H, El MS, Satti A, Idris T, Hashim MS, et al. Urogenital complications among girls with genital mutilation: a hospital-based study in Khartoum. Afr J Reprod Health. 2005;9:118–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalmers B, Hashi KO. 432 Somali women's birth experiences in Canada after earlier female genital mutilation. Birth. 2000;27:227–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behrendt A, Moritz S. Posttraumatic stress disorder and memory problems after female genital mutilation. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1000–2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.el-Defrawi MH, Lotfy G, Dandash KF, Refaat AH, Eyada M. Female genital mutilation and its psychosexual impact. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27:465–73. doi: 10.1080/713846810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almroth L, Elmusharaf S, El HN, Obeid A, El Sheikh MA, Elfadil SM, et al. Primary infertility after genital mutilation in girlhood in Sudan: a case-control study. Lancet. 2005;366:385–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morison L, Scherf C, Ekpo G, Paine K, West B, Coleman R, et al. The long-term reproductive health consequences of female genital cutting in rural Gambia: a community-based survey. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:643–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO study group on female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries. Lancet. 2006;367:1835–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68805-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones H, Diop N, Askew I, Kabore I. Female genital cutting practices in Burkina Faso and Mali and their negative health outcomes. Stud Fam Plann. 1999;30:219–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.1999.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen U, Okonofua FE. Female circumcision and obstetric complications. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;77:255–65. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(02)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat. World population prospects: The 2006revision and world urbanization prospects New York; UN Population Division; 2007. Available from: http://esa.un.org/unpp [accessed 3 October 2007].

- 14.Life tables for WHO Member States 2005. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/whosis/database/life_tables/life_tables.cfm [accessed 3 October 2007].

- 15.Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, Adam T, Walker N. Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet. 2005;365:977–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adam T, Lim SS, Mehta S, Bhutta ZA, Fogstad H, Mathai M, et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of strategies for maternal and neonatal health in developing countries. BMJ. 2005;331:1107. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7525.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adam T, Evans DB, Murray CJ. Econometric estimation of country-specific hospital costs. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2003;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martey JO, Djan JO, Twum S, Browne EN, Opoku SA. Maternal mortality due to hemorrhage in Ghana. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1993;42:237–41. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(93)90217-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Etuk SJ, Asuquo EE. Maternal mortality following post-partum haemorrhage in Calabar a 6-year review. West Afr J Med. 1997;16:165–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibbs S. Female genital mutilation/cutting: what are donors doing? Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2008. Available from: http://apha.confex.com/apha/136am/techprogram/paper_185716.htm [accessed 18 January 2010]. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elnashar A, Abdelhady R. The impact of female genital cutting on health of newly married women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;97:238–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]