Abstract

Objective

To measure progress in implementing co-trimoxazole prophylaxis (CTXp) (trimethoprim plus sulfamethoxazole) and isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) policy recommendations, identify barriers to the development of national policies and pinpoint challenges to implementation.

Methods

In 2007 we conducted by e-mail a cross-sectional survey of World Health Organization (WHO) HIV/AIDS programme officers in 69 selected countries having a high burden of infection with HIV or HIV-associated tuberculosis (TB). The specially-designed, self-administered questionnaire contained items covering national policies for CTXp and IPT in people living with HIV, current level of implementation and barriers to developing or implementing these policies.

Findings

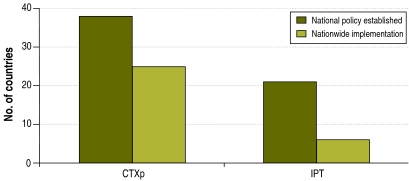

The 41 (59%) respondent countries, representing all WHO regions, comprised 85% of the global burden of HIV-associated TB and 82% of the global burden of HIV infection. Thirty-eight countries (93%) had an established national policy for CTXp, but only 66% of them (25/38) had achieved nationwide implementation. For IPT, 21 of 41 countries (51%) had a national policy but only 28% of them (6/21) had achieved nationwide implementation. Despite significant progress in the development of CTXp policy, the limited availability of co-trimoxazole for this indication and inadequate systems to manage drug supply impeded nationwide implementation. Inadequate intensified tuberculosis case-finding and concerns regarding isoniazid resistance were challenges to the development and implementation of national IPT policies.

Conclusion

Despite progress in implementing WHO-recommended CTXp and IPT policies, these interventions remain underused. Urgent steps are required to facilitate the development and implementation of these policies.

ملخص

الغرض: قياس مدى التقدم المحزر في تطبيق التوصيات الخاصة بالمعالجة الوقائية بالكوتريموكسازول (التريمثوبريم والسلفاميثوكسازول) والمعالجة الوقائية بالإيزونيازيد، والتعرف على المعوقات التي تحول دون وضع السياسات الوطنية مع تحديد التحديات التي تعوق التطبيق.

الطريقة: في عام 2007 قام الباحثون، عن طريق البريد الإلكتروني، بإجراء مسح مستعرض لمسؤولي برنامج مكافحة الإيدز والعدوى بفيروسه التابع لمنظمة الصحة العالمية. وقد أجري المسح في 69 بلداً اختيروا من البلدان ذات العبء المرتفع للعدوى بفيروس الإيدز أو العدوى المشتركة بفيروس الإيدز والسل. وقد تضمن استبيان المسح الذي صمم لهذا الغرض بنوداً غطت السياسات الوطنية الخاصة بالمعالجة الوقائية بالكوتريموكسازول (التريمثوبريم والسلفاميثوكسازول) والمعالجة الوقائية بالإيزونيازيد للمعايشين لفيروس الإيدز، إضافة إلى المستوى الحالي من تطبيق هذه المعالجة والعوائق التي تحول دون تنفيذها.

الموجودات: استجابت41 بلداً (بنسبة 59%)، ممثلة جميع أقاليم منظمة الصحة العالمية، شملت 85% من العبء العالمي للعدوى المشتركة بفيروس الإيدز والسل، و82% من العبء العالمي للإصابة بالفيروس وحده. وكان هناك 38 بلداً (93%) قد أعد بالفعل سياسات وطنية لتنفيذ المعالجة الوقائية بالكوتريموكسازول (التريمثوبريم والسلفاميثوكسازول)، غير أن 66% منها (25/38) طبقها بالفعل على مستوى القطر. أما بالنسبة للمعالجة الوقائية بالإيزونيازيد، فقد كان لدى 21 بلداً من 41 بلداً (51%) سياسات وطنية غير أن تطبيق هذه السياسات على المستوى القطري لم ينفذ سوى في 28% منها فقط (6/21). وبالرغم من التقدم الكبير الذي أحرز في تطوير سياسات المعالجة الوقائية بالكوتريموكسازول (التريمثوبريم والسلفاميثوكسازول)، إلا أن التوافر المحدود للكوتريموكسازول بالنسبة لهذا الغرض مع النظم غير المؤهلة لإدارة إمدادات الدواء أعاقت تطبيق هذه المعالجة على المستوى القطري. أما التحديات التي واجهت تطوير السياسات الوطنية الخاصة بالمعالجة الوقائية بالإيزونيازيد وتطبيقها، فتمثلت في قصور الاكتشاف المكثف لحالات الإصابة بالسل والقلق من المقاومة الدوائية للإيزونيازيد.

الاستنتاج: لايزال استخدام هذه المداخلات ضعيفاً وغير مستغل على الرغم من التقدم المحرز في تطبيق توصيات منظمة الصحة العالمية الخاصة بالمعالجة الإتقائية بالكوتريموكسازول الإتقائي (التريمثوبريم والسلفاميثوكسازول) والمعالجة الوقائية بالإيزونيازيد. وهناك حاجة إلى إحراز خطوات سريعة وفورية لتيسير تطوير وتنفيذ هذه السياسات.

Résumé

Objectif

Mesurer les progrès dans la mise en œuvre des politiques préconisées concernant la prophylaxie par le co-trimoxazole (triméthoprime + sulfaméthoxazole) et le traitement préventif par l'isoniazide (TPI), identifier les obstacles au développement de politiques nationales et mettre le doigt sur les difficultés dans cette mise en œuvre.

Méthodes

En 2007, nous avons mené une enquête transversale par messagerie électronique auprès des responsables des programmes contre le VIH/sida de l'Organisation mondiale de la Santé (OMS), dans 69 pays sélectionnés comme supportant une forte charge d'infection par le VIH ou de tuberculose associée au VIH. Le questionnaire spécialement conçu à cet effet et auto-administré comprenait des points couvrant les politiques nationales concernant la prophylaxie par le co-trimoxazole et le TPI chez les personnes vivant avec le VIH, les niveaux actuels de mise en œuvre de ces politiques et les obstacles s'opposant à leur développement ou à leur application.

Résultats

Les 41 pays (59 %) ayant répondu, représentant toutes les Régions de l'OMS, totalisaient 85 % de la charge mondiale de tuberculose associée au VIH et 82 % de la charge mondiale d'infection à VIH. Trente-huit pays (93 %) disposaient d'une politique nationale établie pour la prophylaxie par le co-trimoxazole, mais seulement 66 % d'entre eux (25/38) étaient parvenus à mettre en œuvre cette politique à l'échelle du pays. S'agissant du TPI, 21 pays sur 41 (51 %) disposaient d'une politique nationale, mais 28 % seulement d'entre eux (6/21) avaient réussi à la mettre en œuvre à l'échelon national. Malgré les progrès importants dans le développement d'une politique pour la prophylaxie par le co-trimoxazole, la disponibilité limitée de ce médicament pour cette indication et la déficience des systèmes de gestion de l'approvisionnement en médicaments ont fait obstacles à l'application de cette politique à l'échelle nationale. Une intensification insuffisante de la recherche des cas de tuberculose et des préoccupations concernant la résistance à l'isoniazide ont nui au développement et à la mise en oeuvre des politiques nationales relatives au TPI.

Conclusion

En dépit des progrès enregistrés dans l'application des politiques concernant la prophylaxie par le co-trimoxazole et le TPI préconisées par l'OMS, ces interventions restent sous-utilisées. Il faut d'urgence prendre des mesures pour faciliter le développement et la mise en œuvre de ces politiques.

Resumen

Objetivo

Medir los progresos realizados en la aplicación de las recomendaciones de política sobre la profilaxis con cotrimoxazol (trimetoprim más sulfametoxazol) (CTXp) y la terapia preventiva con isoniazida (TPI), determinar los obstáculos a la formulación de políticas nacionales y poner de relieve los problemas con que tropieza su aplicación.

Métodos

En 2007 realizamos por e-mail una encuesta transversal entre funcionarios del programa de VIH/sida de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) en 69 países con alta carga de infección por VIH o tuberculosis asociada a VIH. El cuestionario autoadministrado especialmente diseñado contenía preguntas referentes a las políticas nacionales sobre la CTXp y la TPI en las personas afectadas por el VIH, al nivel actual de aplicación y a los obstáculos a la formulación y aplicación de esas políticas.

Resultados

Los 41 países (59%) que respondieron a la encuesta, representativos de todas las regiones de la OMS, abarcaban el 85% de la carga mundial de tuberculosis asociada al VIH y el 82% de la carga mundial de infección por VIH. 38 países (93%) tenían una política nacional arraigada sobre la CTXp, pero sólo el 66% de ellos (25/38) habían logrado aplicarla a nivel nacional. En cuanto a la TPI, 21 de los 41 países (51%) tenían una política nacional, pero sólo el 28% de ellos (6/21) habían logrado aplicarla a nivel nacional. Pese a los importantes avances del desarrollo de las políticas sobre la CTXp, la limitada disponibilidad de cotrimoxazol para esta indicación y los deficientes sistemas de gestión del suministro de medicamentos entorpecían su aplicación a nivel nacional. La poco intensificada búsqueda de casos de tuberculosis y la preocupación que suscita la resistencia a la isoniazida han dificultado el desarrollo y aplicación de las políticas nacionales de TPI.

Conclusión

Pese a los progresos en la aplicación de las políticas recomendadas por la OMS respecto a la CTXp y la TPI, estas intervenciones siguen estando infrautilizadas. Se requieren medidas urgentes para facilitar el desarrollo y aplicación de esas políticas.

Introduction

At the end of 2007, 33.2 million people worldwide were living with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and 95% of them resided in low- or middle-income countries.1 Approximately 3 million people were receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART),2 but an estimated 6.7 million were still in need of ART.1,2 Although global initiatives such as the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief3 and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria4 have focused on scaling up ART, millions of people living with HIV remain eligible for and could benefit from prophylaxis with co-trimoxazole (trimethoprim plus sulfamethoxazole, CTX), co-trimoxazole prophylaxis (CTXp) and isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT).

CTXp is a simple, well-tolerated and cost-effective intervention which can extend and improve the quality of life for people living with HIV, including those on ART. The value of co-trimoxazole in reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with HIV infection has been well established through clinical trials conducted in industrialized5,6 and developing countries.7–26 CTXp is associated with a 25–46% reduction in mortality among individuals infected with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, even in areas with high bacterial resistance to the antibiotic. These improvements in survival have been accompanied by substantial reductions in severe disease events and in the number of hospital admissions linked to invasive bacterial disease, pneumonia, malaria and diarrhoea. In 2006, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued global recommendations for the use of CTX in children exposed to HIV as well as children, adolescents and adults infected with HIV.27 WHO recommends CTXp for all symptomatic persons living with HIV who have mild, advanced or severe HIV disease (WHO clinical stages 2, 3 or 4) or for all persons living with HIV with a CD4+ lymphocyte (CD4) count < 350 per mm3. WHO also recommends CTXp for all infants exposed to HIV and all symptomatic children with HIV infection (WHO clinical stages 2, 3 or 4) and all children with HIV infection who have a CD4 count < 25%. Despite the proven clinical benefits of CTX and recommendations by WHO, the United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), its routine use in developing countries – particularly sub-Saharan Africa – has remained limited.

Tuberculosis (TB) is the most frequent life-threatening opportunistic disease among people living with HIV and remains a leading cause of mortality, even among persons receiving ART. Clinical trials have shown that IPT dramatically reduces the incidence of TB among people living with HIV.28–36 A 2004 Cochrane Review found that IPT reduced the risk of TB by 33% overall and by 64% when targeted to people living with HIV who had a positive tuberculin skin test.36 A recent retrospective study also showed that IPT significantly reduced the incidence of TB even among people living with HIV and receiving ART.36 In 1998, WHO and UNAIDS issued a statement that recognized the effectiveness of IPT among people living with HIV and recommended its use as part of an essential care package for these patients.37 This statement recommends IPT for all people living with HIV in areas with a prevalence of latent TB infection > 30% and for all people with documented latent TB infection or exposure to an infectious TB case, regardless of where they live. These recommendations were reinforced in a statement released by the TB/HIV working group of the Stop TB Partnership in October 2007.38 WHO guidelines on essential prevention and care interventions for people living with HIV also recommend IPT for these individuals.39 However, countries have been slow to adopt these recommendations and many limitations seem to be delaying effective nationwide implementation. In 2007, only 30 000 (0.1%) people living with HIV worldwide had started IPT.40 Unless major efforts are made to identify, prevent and treat TB among people living with HIV, the progress made with HIV care and treatment may be severely undermined because TB both complicates the management of HIV and increases mortality among people living with HIV.

In 2007, WHO conducted a global survey to assess progress in the establishment and implementation of CTXp and IPT policy recommendations. The objectives of the survey were to measure progress in the implementation of CTXp and IPT recommendations, identify barriers to the development of national policies and ascertain challenges for the implementation of these recommendations.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey of WHO HIV/AIDS programme officers was conducted in 2007. A questionnaire was sent via e-mail to programme officers in 69 selected countries representing all WHO regions. Countries were selected according to their contribution to the global burdens of HIV infection and HIV-associated TB based on 2007 WHO/UNAIDS estimates.1,40 A list of countries in each WHO region was created with estimated numbers of patients with HIV infection and HIV-associated TB in each country. The proportion of the global and regional burdens of HIV infection and HIV-associated TB borne by each country was calculated. Countries with the highest burden, which together accounted for > 95% of the global burdens of HIV infection and HIV-associated TB, were selected for inclusion in the survey. The WHO HIV/AIDS programme officers were instructed to use existing data and to consult with the national HIV/AIDS and TB programme managers if necessary to complete the questionnaire. WHO HIV/AIDS programme officers were asked to use the national TB and HIV programme management and logistic reports, and reports from the medical and drug supply system, as the sources of information to complete the questionnaire.

Data were collected on the existence of national policies for CTXp and IPT for people living with HIV, current level of implementation at various facilities, and barriers to the development or implementation of these policies. Information was collected regarding the proportion of facilities that offered HIV care and treatment or TB services and also provided CTXp and IPT. The recorded level of implementation was based on the HIV programme management reports or information collected about the distribution of CTX and isoniazid through the national drug supply system. Countries that provided either CTXp or IPT to people living with HIV in all the regions and districts within the country were considered to have achieved nationwide implementation of the intervention. Open-ended, descriptive items about barriers to the development and implementation of policies were included, as well as space for respondents to provide suggestions about ways to overcome these barriers. Responses to open-ended text items were classified into different themes (one or more themes per response), and the frequencies of each theme identified were recorded.

Staff members at the WHO headquarters in Geneva and regional offices made phone calls and sent follow-up e-mails to improve the response rate. All data were entered into an Access (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, United States of America) data file. The data were analysed with Epi Info version 3.3.2 software (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA).

Results

The 69 countries selected for the survey represented 98% of the global HIV-associated TB burden and 97% of the global burden of HIV infection. The response rate for the survey was 59% (41/69) (Table 1). The 41 responding countries represented 85% and 82% of the global burdens of HIV-associated TB and HIV infection, respectively. Twenty-eight non-respondent countries did not return the questionnaire because the WHO HIV/AIDS programme officers were unable to complete it on time or because in-country WHO staff were unavailable during the survey period.

Table 1. Development and implementation of policies for co-trimoxazole prophylaxis and isoniazid preventive therapy in World Health Organization regions, 2007.

| Region | Countries receiving survey | Countries responding to survey |

Countries with CTXp policy |

Countries with nationwide implementation of CXTp policya |

Countries with IPT policy |

Countries with nationwide implementation of IPT policya |

Respondent countries | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||||||

| African Region | 31 | 17 | 55 | 16 | 94 | 11 | 69 | 8 | 47 | 1 | 13 | Angola, Botswana, Central African Republic, Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Ghana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa, Swaziland, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe | |||||

| Region of the Americas | 10 | 6 | 60 | 6 | 100 | 4 | 67 | 5 | 83 | 2 | 40 | Bahamas, Brazil, Colombia, Guyana, Haiti, Trinidad and Tobago | |||||

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 5 | 3 | 60 | 3 | 100 | 2 | 67 | 1 | 33 | 1 | 100 | Iran, Somalia, Sudan | |||||

| European Region | 11 | 7 | 64 | 6 | 86 | 3 | 50 | 5 | 71 | 2 | 40 | Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, Republic of Moldova, Russian Federation, Tajikistan, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Ukraine | |||||

| South-East Asia Region | 5 | 4 | 80 | 4 | 100 | 2 | 50 | 2 | 50 | 0 | 0 | India, Indonesia, Nepal, Thailand | |||||

| Western Pacific Region | 7 | 4 | 57 | 3 | 75 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Cambodia, China, Philippines, Viet Nam | |||||

| Total | 69 | 41 | 59 | 38 | 93 | 25 | 66 | 21 | 51 | 6 | 28 | All countries | |||||

CTXp, co-trimoxazole prophylaxis; ITP, isoniazid preventive therapy.

a Countries providing co-trimoxazole prophylaxis and isoniazid preventive therapy to people living with HIV in all the regions and districts in the country were considered to have achieved nationwide implementation.

Of the 41 respondent countries, 38 (93%) had developed a national policy to provide CTXp to people living with HIV, but only 66% (25/38) of the countries with a national policy had implemented it on a nationwide scale (Fig. 1). Respondent countries in all WHO regions have made progress in the development and nationwide implementation of a CTXp policy (Table 1). In the 25 countries with nationwide implementation, a median of 90% of the facilities that provided ART (range: 80–100) and of 75% of the facilities that provided HIV care (range: 60–100) were providing CTXp.

Fig. 1.

Progress in development and implementation of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis and isoniazid preventive therapy policies in 41 countries surveyed in all World Health Organization regions, 2007

CTXp, co-trimoxazole prophylaxis; IPT, isoniazid preventive therapy.

Erratic supply and lack of stocks (“stock-outs”) of CTX at health-care facilities were cited as the major obstacles to nationwide implementation of CTXp policy by 70% (19/27) of the countries that responded to the question. Other obstacles included insufficient health-care worker awareness because of lack of training and supervision, perceived low priority of CTXp because of the absence of a reporting requirement, lack of integration of TB/HIV services and fear that CTX prescription would identify patients as infected with HIV. Several suggestions were provided to improve the coverage of CTXp: (i) the availability of CTX could be ensured by strengthening systems for the management of drug procurement and supply chains; (ii) prescriptions of CTX could be included in the programme monitoring system; (iii) awareness of health workers could be improved through training and supervision; (iv) collaboration between services could be improved; (v) community awareness could be improved through social mobilization and advocacy.

With regard to IPT for people living with HIV, 21 of the 41 respondent countries (51%) had developed a national policy, but only 28% (6/21) of these countries had implemented it on a nationwide scale (Fig. 1). Respondent countries in all WHO regions have experienced delays in the development and nationwide implementation of IPT policy (Table 1). In the six countries with nationwide implementation, a median of 3% (range: 0–5) of the facilities that provided ART and HIV care were also providing IPT. A median of 50% (range: 30–80) of the facilities that provided TB services were providing IPT to people with HIV infection.

Of the 20 countries that reported no national IPT policy, 14 provided reasons for not developing the policy. The main reasons were: (i) inadequate intensified TB case-finding because of the inability to exclude active TB, (ii) logistic difficulties in performing tuberculin skin tests to diagnose latent TB infection, and (iii) concerns regarding inadequate patient adherence potentially leading to isoniazid monoresistance. Other reasons included lack of consensus among policy-makers and experts and uncertainty about the long-term benefits of IPT. Countries that had developed an IPT policy also faced the challenges mentioned above in achieving nationwide implementation. Interventions suggested by the respondent countries to encourage the development of an IPT policy or to improve nationwide implementation included: (i) advocacy for IPT at the national and international level, (ii) dissemination of evidence-based information regarding the benefits and feasibility of IPT, and (iii) developing operational guidelines for the implementation of IPT in HIV care and treatment settings.

Discussion

IPT and CTXp are simple and effective interventions known to reduce morbidity among people living with HIV, and CTXp has also been shown to reduce mortality in this population. Although some countries have made progress in implementing policies to provide these services, many limitations remain to the implementation of these evidence-based, WHO-recommended interventions.

Most countries included in the survey have made progress in the development of CTXp policy; however, nationwide implementation seems to be impeded by the lack of consistent supplies of CTX. Usually CTX is not obtained specifically for prophylaxis, and most national HIV programmes do not have systems in place to accurately estimate CTX needs for prophylactic purposes or to monitor its consumption. Because CTX provided to health facilities is used for both therapeutic and prophylactic purposes, this results in frequent stock-outs which affect the initiation and continuation of CTXp. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and other international funding agencies should consider including in their funding proposals instructions on the importance of CTX procurement specifically for prophylaxis in people living with HIV and on monitoring CTXp implementation. In addition, many countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, have problems with supply-chain management that result in stock-outs of drugs and supplies at health facilities even when sufficient quantities are available at central warehouses. Efforts to enhance systems of drug procurement and supply-chain management can help countries implement this intervention more effectively.

The development and implementation of a national IPT policy remains suboptimal in most of the countries that participated in the survey. Inadequate intensified case-finding, including the inability to rule out active TB, was one of the reasons cited most frequently for not developing and implementing IPT policy. WHO guidelines regarding essential prevention and care interventions for people living with HIV recommend that all such individuals be screened for TB at each contact with care services. Despite these recommendations, WHO reports suggest that in 2007, only 2.2% of people living with HIV worldwide were screened for TB.40 Improvements in routine screening to detect signs and symptoms suggestive of TB in people living with HIV are critical for the early identification and treatment of HIV-associated TB. IPT should not be seen as a separate intervention but as a continuum of TB screening, because candidates eligible for IPT would be identified through this process. Individuals with signs and symptoms suggestive of TB should be further evaluated for TB disease, whereas those without these symptoms should be started on IPT. A recent WHO consultation that focused on intensified TB case-finding, IPT and TB infection control (referred to as “The Three Is”) recommended intensified TB case-finding as the gateway for implementing IPT and infection control and highlighted the need for operational guidance for these interventions. The consultation also recommended that national HIV programmes assume responsibility for implementing The Three Is.41

Lack of monitoring of the implementation of CTXp and IPT was another reported constraint to scale-up of these interventions, a limitation that highlights an urgent need. The “what gets measured, gets done” principle, the benefits of IPT in reducing morbidity and the benefits of CTXp in reducing morbidity and mortality among people living with HIV are worth considering with regard to shortcomings in prophylaxis and preventive therapy programmes. Consequently, indicators that measure CTXp and IPT prescription should be included in systems to monitor patients with HIV in order to record progress in implementation.

Retention of patients in HIV care has been a challenge for most national HIV programmes. Patients diagnosed with relatively early HIV infection are often lost to clinical care only to re-enter the medical care system later, when their disease is advanced. National HIV programmes should focus on improving long-term HIV care for people living with HIV by providing CTXp and IPT. Both treatments can prevent opportunistic infections among people living with HIV, improve their quality of life and improve rates of retention in HIV care. These benefits may facilitate regular monitoring of these patients and timely initiation of ART when needed. Operational aspects of CTXp and IPT are similar and the beneficiary population overlaps; consequently the possibility of co-packaging or co-formulating CTX and isoniazid might be explored to address issues related to logistics, adherence and integration of services.

Our study has a few limitations. First, we could not independently validate the data reported by in-country staff because we did not have access to the national reports. Second, because existing national reports were the source of information for this survey, the results may not reflect recent progress at various facilities in the implementation of these policies.

Conclusion

Strong advocacy and dissemination of evidence-based information regarding the benefits of CTXp and IPT are urgently required at the national and international level. IPT offers potential benefits in reducing morbidity, and CTXp offers potential benefits in reducing both morbidity and mortality among people living with HIV. Moreover, TB represents a potential threat to the significant health benefits achievable by scale-up of HIV care and treatment. In light of these considerations, implementation of The Three Is and CTXp should be central to the delivery of HIV care and treatment.

Acknowledgements

We thank our WHO colleagues and health professionals from the ministries of health for collecting information in the relevant countries, Rogers Busulwa (WHO Country Office, Khartoum, Sudan), Edwin Limbambala (WHO Country Office, Lilongwe, Malawi) for field-testing the survey questionnaire, Cathy Coic (IT Training and Support Department, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland) for designing and maintaining the survey database and the WHO HIV Regional Advisers for supporting this survey in the regions. We also thank Haileyesus Getahun, Christian Gunneberg, Siobhan Crowley and Brad Hersh (WHO, Geneva, Switzerland) and Kevin De Cock, Bess Miller and Stefan Wiktor (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Global AIDS Program, Atlanta, Georgia, USA).

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2008. Available from: http://data.unaids.org/pub/GlobalReport/2008/JC1510_2008GlobalReport_en.zip [accessed 8 October 2009].

- 2.Towards universal access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. Geneva: World Health Organization/United Nation’s Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS/United Nations Children’s Fund; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/towards_universal_access_report_2008.pdfhttp://[accessed 8 October 2009].

- 3.United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief [Internet site]. Available from: http://www.pepfar.gov/ [accessed 8 October 2009].

- 4.Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria [Internet site]. Available from: http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/ [accessed 8 October 2009].

- 5.The Cochrane Collaborative Review Group on HIV Infection and AIDS. Evidence assessment: strategies for HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care. San Francisco: University of California, San Francisco, Institute for Global Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones JL, Hanson DL, Dworkin MS, Alderton DL, Fleming PL, Kaplan JE, et al. Surveillance for AIDS-defining opportunistic illness, 1992–1997. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ 1999481–22.PMID:12412613 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nunn AJ, Mwaba P, Chintu C, Mwinga A, Darbyshire JH, Zumla A, et al. Role of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis in reducing mortality in HIV infected adults being treated for tuberculosis: randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a257. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulenga V, Ford D, Walker A, Mwenya D, Mwansa J, Sinyinza F, et al. Effect of cotrimoxazole on causes of death, hospital admissions and antibiotic use in HIV-infected children. AIDS. 2007;21:77–84. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280114ed7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Schechter M, Boulle A, Miotti P, et al. Antiretroviral Therapy in Lower Income Countries (ART-LINC) Collaboration; ART Cohort Collaboration (ART-CC) groups Mortality of HIV-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet. 2006;367:817–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowrance D, Makombe S, Harries A, Yu J, Aberle-Grasse J, Eiger O, et al. Lower early mortality rates among patients receiving antiretroviral treatment at clinics offering cotrimoxazole prophylaxis in Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiktor SZ, Sassan-Morokro M, Grant AD, Abouya L, Karon JM, Maurice C, et al. Efficacy of trimethoprimsulphamethoxazole prophylaxis to decrease morbidity and mortality in HIV-1-infected patients with tuberculosis in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353:1469–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anglaret X, Chêne G, Attia A, Toure S, Lafont S, Combe P, et al. Early chemoprophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole for HIV-1-infected adults in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:1463–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07399-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badri M, Maartens G, Wood R, Ehrlich R. Co-trimoxazole and HIV-1 infection. Lancet. 1999;354:334–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)75237-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zachariah R, Spielmann M, Chinji C, Gomani P, Arendt V, Hargreaves N, et al. Voluntary counselling, HIV testing and adjunctive cotrimoxazole reduces mortality in tuberculosis patients in Thyolo, Malawi. AIDS. 2003;17:1053–61. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200305020-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zachariah R, Harries A, Arendt V, Wennig R, Schneider S, Spielmann M, et al. Compliance to cotrimoxazole for the prevention of opportunistic infections in HIV infected tuberculosis patients in Thyolo, Malawi. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:843–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mwaungulu FB, Floyd S, Crampin AC, Kasimba S, Malema S, Kanyongoloka H, et al. Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis reduces mortality in human immunodeficiency virus-positive tuberculosis patients in Karonga District, Malawi. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:354–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chimzizi R, Gausi F, Bwanali A, Mbalume D, Teck R, Gomani P, et al. Voluntary counselling, HIV testing and adjunctive cotrimoxazole are associated with improved TB treatment outcomes under routine conditions in Thyolo District, Malawi. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:579–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chimzizi RB, Harries AD, Manda E, Khonyongwa A, Salaniponi FM. Counselling, HIV testing and adjunctive cotrimoxazole for TB patients in Malawi: from research to routine implementation. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:938–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mermin J, Lule J, Ekwaru JP, Malamba S, Downing R, Ransom R, et al. Effect of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis on morbidity, mortality, CD4-cell count, and viral load in HIV infection in rural Uganda. Lancet. 2004;364:1428–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grimwade K, Swingler G. Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis for opportunistic infections in adults with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD003108. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grimwade K, Swingler GH. Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis for opportunistic infections in children with HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD003508. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003508.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grimwade K, Sturm A, Nunn A, Mbatha D, Zungu D, Gilks C. Effectiveness of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis on mortality in adults with tuberculosis in rural South Africa. AIDS. 2005;19:163–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200501280-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chintu C, Bhat G, Walker A, Mulenga V, Sinyinza F, Lishimpi K, et al. Co-trimoxazole as prophylaxis against opportunistic infections in HIV-infected Zambian children (CHAP): a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1865–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creese A, Floyd K, Alban A, Guinness L. Cost effectiveness of HIV/AIDS interventions in Africa; a systematic review of the evidence. Lancet. 2002;359:1635–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08595-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watera C, Todd J, Muwonge R, Whitworth J, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Brink A, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis for HIV-1–infected adults attending an HIV/ AIDS clinic in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:373–8. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000221679.14445.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldie SJ, Yazdanpanah Y, Losina E, Weinstein MC, Anglaret X, Walensky RP, et al. Cost effectiveness of HIV treatment in resource-poor settings – the case of Cote d’Ivoire. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1141–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guidelines on co-trimoxazole prophylaxis for HIV infections among children, adolescents and adults in resource-limited settings: recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whalen CC, Johnson JL, Okwera A, Hom DL, Huebner R, Mugyenyi P, et al. A trial of three regimens to prevent tuberculosis in Ugandan adults infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Uganda–Case Western Reserve University Research Collaboration. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:801–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709183371201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Pinho AM, Santoro-Lopes G, Harrison LH, Schechter M. Chemoprophylaxis for tuberculosis and survival of HIV-infected patients in Brazil. AIDS. 2001;15:2129–35. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200111090-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halsey NA, Coberly JS, Desormeaux J, Losikoff P, Atkinson J, Moulton LH, et al. Randomised trial of isoniazid versus rifampicin and pyrazinamide for prevention of tuberculosis in HIV-1 infection. Lancet. 1998;351:786–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)06532-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pape JW, Jean SS, Ho JL, Hafner A, Johnson W. Effect of isoniazid prophylaxis on incidence of active tuberculosis and progression of HIV infection. Lancet. 1993;342:268–72. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mwinga A, Hosp M, Godfrey-Faussett P, Quigley M, Mwaba P, Mugala B, et al. Twice weekly tuberculosis preventive therapy in HIV infection in Zambia. AIDS. 1998;12:2447–57. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199818000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordin FM, Matts JP, Miller C, Brown LS, Hafner R, John SL, et al. A controlled trial of isoniazid in persons with anergy and human immunodeficiency virus infection who are at high risk for tuberculosis. Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:315–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707313370505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bucher HC, Griffith LE, Guyat GH, Sudre P, Naef M, Sendi P, et al. Isoniazid prophylaxis for tuberculosis in HIV infection: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. AIDS. 1999;13:501–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199903110-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woldehanna S, Volmink J. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in HIV-infected persons. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004:CD000171. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000171.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Golub JE, Saraceni V, Cavalcante SC, Pacheco AG, Moulton LH, King BS, et al. The impact of antiretroviral therapy and isoniazid preventive therapy on tuberculosis incidence in HIV-infected patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. AIDS. 2007;21:1441–8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328216f441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Policy statement on preventive therapy against tuberculosis in people living with HIV. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998 (WHO/TB/98.255). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Consensus statement of the core group of TB/HIV Working Group of STOP TB partnership. Geneva: Stop TB partnership. Available from: http://www.stoptb.org/wg/tb_hiv/assets/documents/IPT%20Consensus%20Statement%20TB%20HIV%20Core%20Group.pdf [accessed 8 October 2009].

- 39.Essential prevention and care interventions for adults and adolescents living with HIV in resource-limited settings. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/prev_care/OMS_EPP_AFF_en.pdf [accessed 8 October 2009].

- 40.Global tuberculosis control surveillance, planning and financing. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009 (WHO/TB/2009.411). Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2009/pdf/full_report.pdf [accessed 8 October 2009].

- 41.Three I’s meeting: intensified TB case finding (ICF), isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) and TB infection control (IC) for people living with HIV. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/meetingreports/WHO_3Is_meeting_report.pdf [accessed 8 October 2009].