Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of diets, drug treatment, and behavioural interventions on infantile colic in trials with crying or the presence of colic as the primary outcome measure.

Data sources: Controlled clinical trials identified by a highly sensitive search strategy in Medline (1966-96), Embase (1986-95), and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, in combination with reference checking for further relevant publications. Keywords were crying and colic.

Study selection: Two independent assessors selected controlled trials with interventions lasting at least 3 days that included infants younger than 6 months who cried excessively.

Data synthesis: Methodological quality was assessed by two assessors independently with a quality assessment scale (range 0-5). Effect sizes were calculated as percentage success. Effect sizes of trials using identical interventions were pooled using a random effects model.

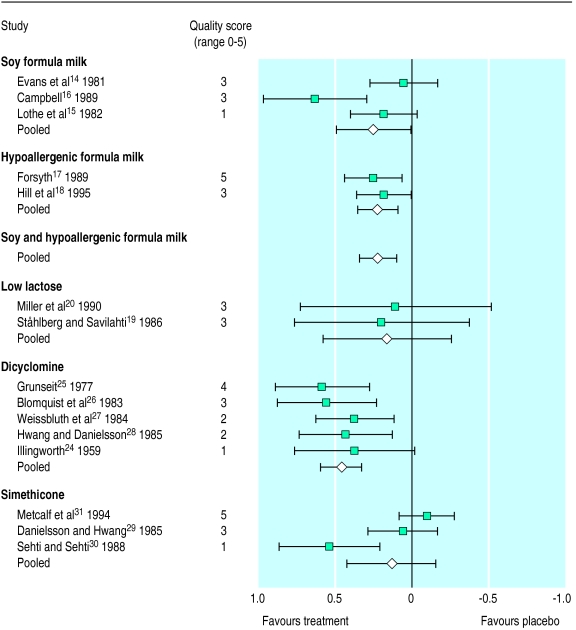

Results: 27 controlled trials were identified. Elimination of cows’ milk protein was effective when substituted by hypoallergenic formula milks (effect size 0.22 (95% confidence interval 0.09 to 0.34)). The effectiveness of substitution by soy formula milks was unclear when only trials of good methodological quality were considered. The benefit of eliminating cows’ milk protein was not restricted to highly selected populations. Dicyclomine was effective (effect size 0.46 ( 0.33 to 0.60)), but serious side effects have been reported. The advice to reduce stimulation was beneficial (effect size 0.48 (0.23 to 0.74)), whereas the advice to increase carrying and holding seemed not to reduce crying. No benefit was shown for simethicone. Uncertainty remained about the effectiveness of low lactose formula milks.

Conclusions: Infantile colic should preferably be treated by advising carers to reduce stimulation and with a one week trial of a hypoallergenic formula milk.

Key messages

Infantile colic is common during the first months of life, but its cause is unknown

A definite diagnosis of infantile colic should be followed by a one week trial of substituting cows’ milk with hypoallergenic formula milk

Dietary intervention should be combined with behavioural interventions: general advice, reassurance, reduction in stimuli, and sensitive differential responding (teaching parents to be more appropriately responsive to their infants with less overstimulation and more effective soothing)

Anticholinergic drugs are not recommended because of their serious side effects

Introduction

Infantile colic—excessive crying in healthy, thriving infants—is a common problem during the first months of childhood. Crying typically occurs in the evenings, episodes starting in the first weeks of life and ending at the age of 4-5 months.1 In studies this crying is arbitrarily defined as lasting at least 3 hours a day, on at least 3 days a week, for at least 3 weeks.2 However, the validity of this criterion is disputed.3 Moreover, whether the symptoms described by Illingworth—high pitched, inconsolable crying accompanied by flushing of the face, drawing up of the legs, passing of gas, and difficulties in passing stools—are unimportant additional features or an integral part of a syndrome is not clear.4

Despite over 40 years of research, the aetiology of infantile colic remains unclear. Four main causes emerge from the literature. Firstly, infantile colic may be a problem with the gut in which excessive crying is the main symptom.5 According to this view, excessive crying is the result of painful gut contractions caused by allergy to cows’ milk, lactose intolerance, or excess gas. Secondly, it may be a behavioural problem resulting from a less than optimal parent-infant interaction, with a difficult temperament of the infant as a possible explanation for inadequate parental reactions.6 Thirdly, the excessive crying in a child with infantile colic could be regarded as merely the extreme end of normal crying.4 Fourthly, infantile colic is just a collection of aetiologically different entities that are not easy to discern clinically.7

Because of the many possible causes, many interventions have been studied. The gut hypothesis has led to interventions such as substituting cows’ milk with soy milk or protein hydrolysate (hypoallergenic), low lactose, or fibre enriched formula milk; using herbal tea; and using drugs to reduce painful gut contractions (dicyclomine) or the formation of intraluminal gas (simethicone). The behavioural hypothesis has led to interventions such as modifying parents’ responsiveness, using motion and sound to calm the baby, and reducing stimuli.

Despite the favourable clinical course of infantile colic—most infants are free of symptoms by the age of 4-5 months—many parents seek medical help. Moreover, although serious somatic problems are absent in most cases, doctors and nurses believe that that they have to do something because of the trouble parents are experiencing. However, so far, it is not clear which of the treatments is the most effective. Neither is it clear whether some infants will benefit more than others from a specific intervention.

We therefore conducted a systematic review of all experimental studies to evaluate the effectiveness of diets, drug treatment, behavioural interventions, and other treatments for infantile colic.

Methods

Study selection

A highly sensitive search in Medline (1966-96),8 an analogue search in Embase (1986-95), and a search in the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register9 were performed. Search headings were “colic” and “crying.” In addition, “crying” and “colic” were separately used as free textwords with an age restriction (<2 years). This search strategy was supplemented with checking the references for missing publications. We selected identified publications on the treatment of infantile colic that used reduction in crying or colic as the main outcome measure. We did not include abstracts or letters. To cover the entire clinical range of infantile colic, we decided to include trials that did not use a time criterion as well. We excluded trials whose authors said that they had studied infants with a normal crying pattern and whose mothers had not complained of the crying. Other reasons for exclusion were that the interventions lasted less than 3 days, a concurrent control group was lacking, and the infants were older than 6 months. AKN and PL independently applied the exclusion criteria and reached a consensus in cases of disagreement.

Methodological quality

We evaluated the methodological quality of all included trials with the quality assessment scale developed by Jadad et al.10 Each trial was scored on adequacy of randomisation, double blinding, and completeness of follow up. We calculated the percentages of the maximum score on each item to estimate the mean quality of all trials. The total quality score of each trial is given in round numbers from 0 to 5. Trials scoring 0 or 1 were at the outset considered to be of too low quality to be included in the evidence. WvG and PL scored all trials independently but they were not blind about information on authors and journals because PL was well acquainted with the material. Consensus was reached in cases of disagreement. The degree of agreement before the consensus meeting was expressed as percentage agreement and as kappa.11,12

Presentation of data

Data are presented on age (mean, range), male to female ratio, age at onset of infantile colic, baseline crying (number of hours daily), percentage of infants who were being breast fed, percentage of infants who were the firstborn, numbers of infants completing the trial, drop out rates, effect sizes, quality scores, and family history of atopy.

Statistics

The main outcome measurement in all trials was the duration of crying or the presence of colic, measured on dichotomous, ordinal, or continuous scales. We calculated effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals as percentage success, using specific modifications for crossover studies and for different levels of measurement (details available on web at www.bmj. com). We estimated outcome from figures for studies that gave results only in figures but not in numbers.

We pooled the effect sizes in trials with comparable interventions: elimination of cows’ milk protein, use of low lactose formula milks, treatment with dicyclomine, and treatment with simethicone. We decided at the outset not to pool all dietary trials or trials of behavioural interventions, herbal tea, two active treatments, or other drug treatments because the interventions differed too much. Because of clinical heterogeneity we used a random effects model in which weight is given to the inverse variance.13 Thus, smaller studies (with larger variances) contribute less than larger studies to the pooled effect. As a sensitivity analysis we repeated the pooling process after removing trials with quality scores of 0 or 1.

Results

Selected trials

The Medline search yielded 187 publications, the Embase search 312, and the search in the Cochrane database 220. Searching this output resulted in 34 trials. Reference checking yielded another 16 trials, two abstracts, and one letter. Thus 50 complete publications were located, of which 23 were excluded, mainly because a control group was lacking and crying was labelled normal. Six of the excluded trials studied a dietary intervention, six a behavioural intervention, five drug treatment, three motion and sound, two chiropractic, and one the use of a dummy (details available on the web at www.bmj.com). Before the consensus discussions on exclusion criteria, there was disagreement on 10 out of 200 items (50 publications, four items per publication; agreement 95%). Consensus was reached in all cases.

Twenty seven trials were included.14–40 One letter41 gave additional information about a trial.23 Twelve of the trials used a parallel design and 15 a crossover design. The table shows the baseline characteristics of patients included in the 27 trials. The trials in this review included infants who are typical of those with infantile colic. Information about the presence of atopic features or a positive family history for atopy was given in four trials.14–16,37 Twelve out of 27 trials were conducted in general practice or community based health services. We included 10 trials of diet or herbal tea, of which five studied the elimination of cows’ milk protein and two low lactose formula milk; 10 trials of drug treatment, particularly with dicyclomine and simethicone; four trials of behavioural interventions; and three trials comparing two active treatments (for details see tables A-E on the web at www.bmj.com). The figure shows the pooled results and how quality influences the pooled effect.

Methodological quality

The quality score according to the scale of Jadad et al10 ranged from 0 to 5 (median 3). The percentage of the maximum score of all trials on the item “adequacy of randomisation” was 61%, on “double blinding” 31%, and on “follow up” 31%. Nine trials scored 0 or 1, indicating insufficient quality.15,21,24,30,32,33,37,38,40 Interrater agreement on the scale was good (agreement 86%, kappa 0.71). Most disagreement was caused by slight differences in interpretation and was resolved easily. Finally, consensus was reached in all cases. Quality score and effect measure were not correlated (r=−0.02, P=0.92), indicating that there was no relation between the quality of the study and the magnitude of the effects.

Results from diet trials

Interventions in trials using soy, hypoallergenic, or low lactose formula milks lasted 6-8 days; follow up in parallel trials was 6-8 days and in crossover trials 12-16 days. Drop out rates were not reported in three trials; four trials reported drop out rates of 20-47%. Concomitant interventions were not mentioned.

Five trials studied the effect of eliminating cows’ milk protein on excessive crying. Two trials were performed in non-specialist settings. Three trials used soy milk as a substitute,14,15,16 and two a hypoallergenic formula milk (casein hydrolysate).17,18 The pooled effect size of eliminating cows’ milk was 0.22 (95% confidence interval 0.10 to 0.34) (fig 1). Substitution of cows’ milk by soy or hypoallergenic formula milk showed a different effect. Hypoallergenic formula milk had a clear effect on infantile colic (effect size 0.22 (0.09 to 0.35)). The effect of soy formula milk was clear only when the quality of the trial was not considered (effect size 0.25 (0.00 to 0.50)). The significance of the pooled effect of the soy trials disappeared when calculations were made with methodologically sound trials alone (effect size 0.32 (0.17 to 0.81)). Comparison of breast milk with standard cows’ milk in infants who were already weaned showed no significant differences (effect size −0.40 (−0.83 to −0.03)).19

The trials, including those of soy formula milk, reported no adverse events. One trial reported no influence of maternal atopy on outcome of treatment14; the other publications did not report whether infants with atopic features reacted better than those without atopy to the elimination of cows’ milk protein.

There was no evidence of effect on excessive crying of lowering the lactose content of the formula milk. Adding fibre to the formula was not effective either. Herbal tea containing chamomile, vervain, liquorice, fennel, and balm mint seemed to be effective in treating excessive crying (table).

Trials of drug treatment

Drug treatment was given for 1 week in all but one trial. Drop out rates were not reported in three trials; five trials reported drop out rates of between 10% and 20%. No concomitant interventions were mentioned.

The anticholinergic drugs dicyclomine and dicycloverine showed a clear benefit in the treatment of excessive crying. The pooled results show a clinically significant improvement (effect size 0.46 (0.33 to 0.60)) (figure). This result did not change when low quality trials were excluded from the calculations. In the trials reporting on the effectiveness of dicyclomine and dicycloverine 177 infants were given the active substance. Three trials did not report adverse effects.24,26,40 Nine out of 177 infants (5%) showed adverse reactions; one of these infants received higher than the recommended dose, whereas the other infants were given normal doses. Reported side effects were a wide eyed, dopey, drugged look followed by sleep within 30 minutes (one child), loose motions (one child), constipation (two children), and drowsiness (four children).

Simethicone treatment showed no benefit (figure). This result did not change when only trials of sufficient quality were analysed.

Trials of behavioural interventions

Trials of behavioural interventions had durations of follow up ranging from 2 weeks to 3 months. Drop out rates varied from 0 to 16%. Neither concomitant treatments nor side effects were reported.

Increased carrying did not reduce crying.34 On the contrary, the advice to reduce stimulation in combination with permission to leave the infant when the carer thought that the crying was no longer tolerable was effective when compared with the control treatment—an empathic interview whose content was not clear.35 Specific management techniques (early response to the crying, gentle soothing motion, avoidance of overstimulation, use of a dummy, prophylactic holding and carrying, use of an infant carrier, and maintenance of day-night orientation) in combination with general information and reassurance proved to be worse than the control treatment (general information and reassurance). A combination of general information and reassurance with vibration in a device simulating riding in a car together with sound elicited no better result than control treatment alone.36

Trials comparing two active treatments

Taubman found that increasing parental responsiveness was better than eliminating cows’ milk protein and substituting it with hypoallergenic formula milk.39 The studies by Westphal and Medin38 and Oggero et al40 are of low quality and therefore not included in the evidence.

Discussion

We conclude that the elimination of cows’ milk protein, certain behavioural interventions, and dicyclomine are effective treatments for infantile colic. The clinical importance of the effect sizes in the figure is shown by the congruence of an effect size of 0.18 with a number needed to treat of 6.18 There is no evidence that low lactose formula milks, fibre enriched formula milks, simethicone, and increased carrying and holding are effective. The power of the studies of low lactose milks is too low to make definitive conclusions. The effectiveness of herbal tea is not definitely established because only one trial was performed. Because trials on the use of motion and sound and chiropractic were uncontrolled, no judgments can be made about these treatments.

Eliminating cows’ milk protein

Elimination of cows’ milk protein is effective not only in highly selected subgroups of infants but also in primary care settings. This finding contradicts former reviews.7,42 One trial was not considered in these reviews16 and one trial was published after them.18 Elimination of cows’ milk protein raises the question of which substitute to use—a soy or a protein hydrolysate formula milk. If a hydrolysate is chosen should it be a whey or a casein hydrolysate?

The use of soy formula milks is debatable. Although the American Academy of Pediatrics’ committee on nutrition recommends against the use of soy protein formula milks for routinely managing colic,43 Businco et al believe that they are the best treatment for children with allergy to cows’ milk mediated by IgE.44 The argument against soy formula milks is that infants with allergy to cows’ milk are more prone to developing allergy to soya. Our review does not establish the effectiveness of soy formula milks in infantile colic. Therefore, a protein hydrolysate is the preferred treatment for colicky infants with allergic features. Our review contains only trials of casein hydrolysates, but whey protein has a role in infantile colic.45,46 There seems to be little reason to dismiss whey protein hydrolysates from the treatment of infantile colic, provided that extensively hydrolysated preparations are used. An advantage of whey protein hydrolysates over casein hydrolysates is their better taste and favourable cost.

It is probable, but not proved, that infants who cry excessively and have one or more atopic features benefit more than those without atopy from the elimination of cows’ milk protein.

Breast fed infants have similar rates of colic as formula fed infants.4 This might be because breast milk contains intact proteins from cows’ milk. To test the possible role of cows’ milk proteins, lactating mothers of colicky babies are advised to eliminate cows’ milk from their diet and replace it with soy14 or hypoallergenic formula milk.18 As already stated, the use of soy is debatable because of the risk of developing allergy to soy proteins.

Dicyclomine and side effects

Dicyclomine is effective in treating infantile colic, but 5% of the treated infants had side effects. The manufacturer reports breathing difficulties, seizures, syncope, asphyxia, muscular hypotonia, and coma as side effects.47 In addition, apnoea of short duration was reported in two infants.47 Although these side effects are probably rare, there seems to be sufficient reason not to use these substances to treat infantile colic, a condition with a favourable clinical course and without serious somatic consequences.

Behavioural interventions

The results of the three trials of behavioural interventions that were of sufficient quality were not comparable at first sight. However, sensitive differential responding by parents48 may be the corresponding feature in at least two of the three trials. Both standard treatment in the study by Barr et al and advice about reducing stimulation in that of McKenzie contain items fitting with sensitive differential responding. Unfortunately, the fit was far from perfect as all treatments contain items that could also lead to overstimulation. The results of the trial of Parkin et al are not in accord with this concept.36 A possible explanation is that their specific management techniques led to overstimulation and thus did not diminish crying. In short, stimulating responsiveness in the parent-child interaction may be beneficial in treating infantile colic.

The trials targeted the reduction of crying and fussing behaviour. This is valuable as it reduces tension and exhaustion in the family. The question is whether the goals should be increased with this approach. When the crying stops after several weeks, either spontaneously or as a result of some intervention, the parent-child relationship could be disturbed. As a consequence, further development may be suboptimal. In fact, children who had infantile colic continued to have more interactional and behavioural problems at the age of 3 and were still seen as more difficult at that age by their mothers.49,50 So, attention to the parent-child interaction at an early age is important. In addition, interventions directed at maternal responsiveness continue to be effective during the following years. In particular, children for whom the intervention happened remained more securely attached to their mother.51,52

The quality scores of the trials of behavioural interventions were not fully comparable with the quality scores of the trials of diet or drug treatment as double blinding is not possible in the behavioural trials. Consequently, the maximum quality score in these trials is 3 instead of 5.

Methodological concerns

At first sight the selected trials show considerable clinical heterogeneity in design, outcome measure, type of intervention, effect size, and quality. Therefore, we decided at the outset to pool only the trials with the same intervention and to use a random effects model, which gives a more conservative estimate of the effect sizes. The risk of not selecting trials properly for this review is low because we used a highly sensitive search strategy in combination with extensive reference checking. As there was no significant correlation between sample size and effect size (r=−0.34, P=0.08), we could not show publication bias.53 However, a funnel plot54 was not possible without larger trials. Moreover, removing one trial of low quality21 changed r to −0.52 (P=0.01). In general, trial quality was low, mainly because of the low scores for double blinding and completeness of follow up. Obviously, in trials of a behavioural intervention double blinding is not possible.

The use of a control group in trials on infantile colic is important because the condition is self limiting and generally has a favourable outcome within several weeks to months. Without comparing the results of an intervention with those in a control group every treatment seems beneficial. The criterion of the duration of the intervention was based on the large day to day variability in the amount of crying. Therefore, neither the efficacy of the treatment nor its effectiveness (including side effects) can correctly be assessed in trials using interventions applied for too short a time. Three trials were excluded on this criterion.45,46,55 Two of them did not use a control group either.45,46

Recommendations for practice and future research

Healthcare workers in primary care faced with parents complaining about their excessively crying infants should check some common explanations first. Can hunger or cold explain the crying? Is feeding technique adequate? Is there any somatic problem causing pain or itch?42 Having excluded these common explanations of crying, a detailed history should be taken about the timing and the amount of crying, measures parents have already tried, ideas and fears of the parents, the care taking routines, and the ways parents handle the child when crying. The amount of crying is important because the results of this review apply only to infants crying more than 3 hours a day.

The first step in treating a child with infantile colic is general advice and reassurance. This should include the information that infantile colic is a self limiting condition resolving by 3-4 months of age and is not due to a disease or to anything parents have or have not done to their infant. Next, parents’ responsiveness (sensitive differential responding48) should be stimulated: check for hunger when crying, check nappy, avoid carrying and holding for long periods, try to establish a regular pattern during the day, do not intervene immediately when the infant cries. There is some evidence for these measures. However, the advice is mainly based on everyday practice. The recommendations should be accompanied by advising the parents not to exhaust themselves and to leave their baby with others when necessary. A one week trial with a hypoallergenic formula milk based on whey or casein is recommended. We think that drug treatment of infantile colic has no place in primary care. Follow up consultations are desirable for discussion of the results of the proposed measures.

More research is necessary on dietary treatment. A large trial comparing casein and whey hydrolysates should be performed in sufficient numbers of infants with atopic features or atopic family history. The low lactose formula milks have not proved to be effective and should be investigated further. The finding that herbal tea is effective23 needs confirmation by other trials. Research is needed to further refine the concept of sensitive differential responding, with special emphasis on how parents practise the interventions.

We recommend that modified anticholinergic drugs be developed that have the beneficial effects of dicyclomine but not its adverse effects. Randomised controlled trials with a parallel instead of a crossover design are preferable in studying infantile colic. Trials with a crossover design are most suitable in chronic, stable conditions in which the condition is not changed by the intervention.56 Thus, the short duration of infantile colic, its favourable clinical course, and its marked day to day variability are reasons to prefer trials with a parallel design.

Figure.

Effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals of included trials

Table.

Baseline characteristics, effect sizes, and quality scores of included trials

| Study | Intervention* | No who completed trial | Drop out rate (%) | Boys (%) | Mean age (weeks) (range) | Age at onset of colic (weeks) | Breast fed (%)† | Firstborn (%) | Baseline crying (h/day) | Effect size (%) (95% CI) | Quality score (range 0-5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evans et al14 | Soy formula milk | 20 | NR | 40 | 7 (3-18) | 3 | 100 | 0.05 (−0.01 to 0.11) | 3 | ||

| Lothe et al15 | Soy formula milk | 60 | 8 | 38 | (2-13) | 8 | 0.18 (0.08 to 0.28) | 1 | |||

| Campbell16 | Soy formula milk | 19 | NR | 58 | 7 (3-14) | 2 | 0 | 21 | 0.63 (0.29 to 0.97) | 3 | |

| Forsyth17 | Hypoallergenic formula milk | 17 | 47 | 65 | 5 (<8) | 0 | 3-4 | 0.25 (0.07 to 0.44) | 5 | ||

| Hill et al18 | Hypoallergenic formula milk | 115 | 24 | 7 (4-16)‡ | 2 | 67 | 51 | 0.18 (0.01 to 0.36) | 3 | ||

| Ståhlberg and Savilahti19 | Low lactase | 10 | NR | 12 | 4 | 0 | 0.20 (−0.37 to 0.77) | 3 | |||

| Miller et al20 | Low lactase | 12 | 20 | 42 | 7-8 (3-9)‡ | 0 | 0.11 (−0.59 to 0.80) | 3 | |||

| Jain and Tripathi21 | Herbal mixture | 100 | NR | 0.76 (0.62 to 0.89) | 0 | ||||||

| Treem et al22 | Fibre | 27 | 18 | 48 | 5 (1-8) | 2 | 0 | 56 | 5-6 | 0.26 (−0.11 to 0.63) | 3 |

| Weizman et al23 | Herbal tea | 68 | 6 | 38 | 3 (2-8)‡ | 69 | 63 | 3-4§ | 0.32 (0.10 to 0.54) | 5 | |

| Illingworth24 | Dicyclomine | 16 | 20 | 0.38 (−0.02 to 0.77) | 1 | ||||||

| Grunseit25 | Dicycloverine | 22 | 12 | 41 | 5 (3-12) | 73 | 0.59 (0.28 to 0.90) | 4 | |||

| Blomquist et al26 | Dicyclomine | 18 | NR | 44 | (2-14) | 89 | 33 | 0.56 (0.23 to 0.88) | 3 | ||

| Weissbluth et al27 | Dicyclomine | 48 | 13 | 58 | 5 | 2 | 50 | 50 | 0.38 (0.12 to 0.63) | 2 | |

| Hwang and Danielsson28 | Dicyclomine | 30 | NR | 4.5 | 4.9 | 0.43 (0.13 to 0.74) | 2 | ||||

| Danielsson and Hwang29 | Simethicone | 27 | 16 | 44 | 5 (2-8) | 96 | 6.3 | 0.06 (−0.17 to 0.28) | 3 | ||

| Sehti and Sehti30 | Simethicone | 26 | 10 | 38 | (1-12) | 0.54 (0.21 to 0.87) | 1 | ||||

| Metcalf et al31 | Simethicone | 83 | NR | 49 | (2-8)‡ | 49 | −0.10 (−0.27 to 0.08) | 5 | |||

| Illingworth32 | Other drug treatment | 40 | NR | 55 | 5 | 80 | 63 | −0.10 (−0.37 to 0.17) | 1 | ||

| O’Donovan and Bradstock33 | Other drug treatment | 97 | 12 | 49 | (2-6)‡ | 7 | −0.15 (−0.39 to 0.09) | 1 | |||

| Barr et al34 | Behavioural | 66 | 7 | 36 | 3 | 68 | 77 | 3.4 (SD 1.7) | 0.12 (−0.03 to 0.27) | 3 | |

| McKenzie35 | Behavioural | 42 | 7 | 10¶ | 0.48 (0.23 to 0.74) | 3 | |||||

| Parkin et al36 | Behavioural | 38 | 16 | 68 | 7 | 55 | 66 | 5.7 (SD 2.4) | −0.37 (−0.69 to −0.05) | 3 | |

| Wolke et al37 | Behavioural | 92 | 0 | 50 | 13 (<26)‡ | 39 | 59 | 5.8 | 0.16 (0.02 to 0.30) | 1 | |

| Westphal and Medin38 | Simethicone, methylscopolamine | 24 | 8 | 6-7 | 54 | 0.33 (0.11 to 0.56) | 1 | ||||

| Taubman39 | Behavioural, hypoallergenic formula milk | 20 | 5 | 6 (<12)‡ | 35 | 30 | 3.2 | 0.30 (0.06 to 0.55) | 3 | ||

| Oggero et al40 | Dicyclomine, diet soy or hypoallergenic formula milk | 120 | NR | 7 (3-12) | 26 | >3 | −0.42 (−0.58 to −0.26) | 1 |

NR=not reported.

All trials used placebo or standard treatment except references 38-40.

Total or partial breast feeding.

Age not given in results, but stated in inclusion criteria.

Data obtained from published letter from authors.41

Median.

Acknowledgments

We thank H Rothuis-ter Haar and Anja van Guluck for their help in the hospital library and in performing the computerised search; Rosemarie Tomes for linguistic revision of the manuscript; and Iris Pasternack for a translation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

Funding: The part of the project dealing with the treatment of infantile colic with hypoallergenic formula milk was funded by the Praeventie Fonds (grant No 002824560).

References

- 1.Illingworth RS. Infantile colic revisited. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60:981–985. doi: 10.1136/adc.60.10.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wessel MA, Cobb JC, Jackson EB, Harris GS, Detwiler AC. Paroxysmal fussing in infancy, sometimes called “colic.”. Pediatrics. 1954;14:421–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.St James-Roberts I. Persistent infant crying. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66:653–655. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.5.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barr RG. Colic and gas. In: Walker WA, Durie PR, Hamilton JR, editors. Pediatric gastrointestinal disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Philadelphia: Decker; 1991. pp. 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller AR, Barr RG. Infantile colic. Is it a gut issue? Pediatr Clin North Am. 1991;38:1407–1423. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38227-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carey WB. “Colic”—primary excessive crying as an infant-environment interaction. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1984;31:993–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)34681-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Treem WR. Infant colic. A pediatric gastroenterologist’s perspective. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1994;41:1121–1138. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38848-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickersin K, Scherer R, Lefebvre C. Identifying relevant studies for systematic reviews. BMJ. 1994;309:1286–1291. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6964.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cochrane Controlled Trials Register. The Cochrane library (database on CD-Rom). Oxford: Update Software; 1997. (Cochrane Collaboration; issue 1). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds JM, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Controlled Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman and Hall; 1991. pp. 404–408. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brennan P, Silman A. Statistical methods for assessing observer variability in clinical measures. BMJ. 1992;304:1491–1494. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6840.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shadish WR, Haddock CK. Combining estimates of effect size. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, editors. The handbook of research synthesis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1994. pp. 261–281. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans RW, Fergusson DM, Allardyce RA, Taylor B. Maternal diet and infantile colic in breast-fed infants. Lancet. 1981;i:1340–1342. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92519-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lothe L, Lindberg T, Jakobsson I. Cow’s milk formula as a cause of infantile colic: a double-blind study. Pediatrics. 1982;70:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell JPM. Dietary treatment of infant colic: a double-blind study. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1989;39:11–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forsyth BWC. Colic and the effect of changing formulas: a double-blind, multiple-crossover study. J Pediatr. 1989;115:521–526. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill DJ, Hudson IL, Sheffield LJ, Shelton MJ, Menahem S, Hosking CS. A low allergen diet is a significant intervention in infantile colic: results of a community-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96:886–892. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ståhlberg MR, Savilahti E. Infantile colic and feeding. Arch Dis Child. 1986;61:1232–1233. doi: 10.1136/adc.61.12.1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller JJ, McVeagh P, Fleet GH, Petocz P, Brand JC. Effect of yeast lactase enzyme on “colic” in infants fed human milk. J Pediatr. 1990;117:261–263. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain SL, Tripathi SN. Clinical assessment of Elcarim drops on colics, regurgitation, griping pain and constipation in infants in the age group below six months. Med Surg. 1987;27:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Treem WR, Hyams JS, Blankschen E, Etienne N, Paule CL, Borschel MW. Evaluation of the effect of a fiber-enriched formula on infantile colic. J Pediatr. 1991;119:695–701. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80282-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weizman Z, Alkrinawi S, Goldfarb D, Bitran C. Efficacy of herbal tea preparation in infantile colic. J Pediatr. 1993;122:650–652. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Illingworth RS. Evening colic in infants. A double-blind trial on dicyclomine hydrochloride. Lancet. 1959;2:1119–1120. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grunseit F. Evaluation of the efficacy of dicyclomine hydrochloride (“Merbentyl”) syrup in the treatment of infantile colic. Curr Med Res Opin. 1977;5:258–261. doi: 10.1185/03007997709110175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blomquist HK, Mjörndal T, Tiger G. Dicykloverinkloridlösning - hjälp vid svår spädbarnskolik. Läkartidningen. 1983;80:116–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weissbluth M, Christoffel KK, Davis AT. Treatment of infantile colic with dicyclomine hydrochloride. J Pediatr. 1984;104:951–955. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hwang CP, Danielsson B. Dicyclomine hydrochloride in infantile colic. BMJ. 1985;291:1014. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6501.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danielsson B, Hwang CP. Treatment of infantile colic with surface active substance (simethicone) Acta Paediatr Scand. 1985;74:446–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1985.tb11001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sehti KS, Sehti JK. Simethicone in the management of infantile colic. Practitioner. 1988;232:508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Metcalf TJ, Irons TG, Sher LD, Young PC. Simethicone in the treatment of infantile colic: a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Pediatrics. 1994;94:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Illingworth RS. Three months’ colic. Treatment by methylscopolamine nitrate (“Skopyl”) Acta Paediatr. 1955;44:203–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1955.tb04133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Donovan JC, Bradstock AS. The failure of conventional drug therapy in the management of infantile colic. Am J Dis Child. 1979;133:999–1001. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1979.02130100023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barr RG, McMullan SJ, Spiess H, Leduc DG, Yaremko J, Barfield R, et al. Carrying as colic “therapy”: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 1991;87:623–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKenzie S. Troublesome crying in infants: effect of advice to reduce stimulation. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66:1416–1420. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.12.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parkin PC, Schwartz CJ, Manuel BA. Randomized controlled trial of three interventions in the management of persistent crying of infancy. Pediatrics. 1993;92:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolke D, Gray P, Meyer R. Excessive infant crying: a controlled study of mothers helping mothers. Pediatrics. 1994;94:322–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Westphal O, Medin S. Behandling av 3-månaderskolik med yaktiv substans. Läkartidningen. 1972;69:3331–3334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taubman B. Parental counseling compared with elimination of cow’s milk or soy milk protein for the treatment of infant colic syndrome: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 1988;81:756–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oggero R, Garbo G, Savino F, Mostert M. Dietary modifications versus dicyclomine hydrochloride treatment of severe infantile colics. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83:222–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weizman Z, Alkrinawi S, Goldfarb D, Bitran C. Herbal teas for infantile colic. J Pediatr. 1993;123:670–671. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolke D. The treatment of problem crying behavior. In: St James-Roberts I, Harris G, Messer D, editors. Infant crying, feeding and sleeping. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf; 1993. pp. 47–79. [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Academy of Pediatrics; Committee on Nutrition. Soy protein formulas: recommendations for use in infant feeding. Pediatrics. 1983;72:359–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Businco L, Bruno G, Giampietro PG, Cantani A. Allergenicity and nutritional adequacy of soy protein formulas. J Pediatr. 1992;121:S21–S28. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jakobsson I, Lindberg T. Cow’s milk proteins cause infantile colic in breast-fed infants: a double-blind crossover study. Pediatrics. 1983;71:268–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lothe L, Lindberg T. Cow’s milk whey protein elicits symptoms of infantile colic in colicky formula-fed infants: a double-blind crossover study. Pediatrics. 1989;83:262–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams J, Watkin-Jones R. Dicyclomine: worrying symptoms associated with its use in some small babies. BMJ. 1984;288:901. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6421.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carey WB. The effectiveness of parental counseling in managing colic. Pediatrics. 1994;94:333–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Forsyth BWC, Canny PF. Perception of vulnerability 3½ years after problems of feeding and crying behavior in early infancy. Pediatrics. 1991;88:757–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rautava P, Lehtonen L, Helenius H, Silanpää M. Infantile colic: child and family three years later. Pediatrics. 1995;96:43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van den Boom DC. The influence of temperament and mothering on attachment and exploration: an experimental manipulation of sensitive responsiveness among lower-class mothers with irritable infants. Child Dev. 1994;65:1457–1477. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van den Boom DC. Do first-year intervention effects endure? Follow-up during toddlerhood of a sample of Dutch irritable infants. Child Dev. 1995;66:1798–1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991;337:867–872. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moher D, Olkin I. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. A concern for standards. JAMA. 1995;274:1962–1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iacono G, Carroccio A, Montalto G, Cavataio F, Bragion E, Lorello D, et al. Severe infantile colic and food intolerance: a long-term prospective study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1991;12:332–335. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199104000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pocock SJ. Clinical trials. A practical approach. Chichester: Wiley; 1988. p. 111. [Google Scholar]