Abstract

Objective

To examine the nature of the relationship between the use of skilled attendance around the time of delivery and maternal and perinatal mortality.

Methods

We analysed health and demographic surveillance system data collected between 1987 and 2005 by the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR,B) in Matlab, Bangladesh.

Findings

The study recorded 59 165 pregnancies, 173 maternal deaths, 1661 stillbirths and 1418 early neonatal deaths in its service area over the study period. During that time, the use of skilled attendance during childbirth increased from 5.2% to 52.6%. More than half (57.8%) of the women who died and one-third (33.7%) of those who experienced a perinatal death (i.e. a stillbirth or early neonatal death) had sought skilled attendance. Maternal mortality was low among women who did not seek skilled care (160 per 100 000 pregnancies) and was nearly 32 times higher (adjusted odds ratio, OR: 31.66; 95% confidence interval, CI: 22.03–45.48) among women who came into contact with comprehensive emergency obstetric care. Over time, the strength of the association between skilled obstetric care and maternal mortality declined as more women sought such care. Perinatal death rates were also higher for those who sought skilled care than for those who did not, although the strength of association was much weaker.

Conclusion

Given the high maternal mortality ratio and perinatal mortality rate among women who sought obstetric care, more work is needed to ensure that women and their neonates receive timely and effective obstetric care. Reductions in perinatal mortality will require strategies such as early detection and management of health problems during pregnancy.

ملخص

الغرض

فحص طبيعة العلاقة بين اللجوء إلى الإشراف الماهر المحيط بفترة الولادة ووقوع وفيات الأمهات والوفيات في الفترة المحيطة بالولادة.

الطريقة

حلل الباحثون معطيات نظام الترصد الصحي والديموغرافي التي جُمعت خلال الفترة بين عامي 1987 و 2005 من قبل المركز الدولي لبحوث أمراض الإسهال، في مطلب ببنغلاديش.

الموجودات

سجلت الدراسة في منطقة خدمات المركز خلال فترة الدراسة 59165 حملاً، و 173 وفاة للأمهات، و 1661 ولادة وليد ميت، و 1418 وفاة ولدان مبكرة. ازداد، خلال هذا الوقت، اللجوء إلى الإشراف الماهر أثناء الولادة من 5.2% إلى 52.6%. أكثر من نصف النساء المتوفيات (57.8%) وثلث الأطفال المتوفين (33.7%) في الفترة المحيطة بالولادة (أي ولادة الوليد الميت أو وفاة الولدان المبكرة) قد سعوا إلى الإشراف الماهر على الولادة. وكانت وفيات الأمهات أقل بين النساء اللاتي لم تسعين إلى الإشراف الماهر (160 وفاة لكل 100 ألف حمل) وكانت الوفيات أعلى بـ 32 مرة (معدل الأرجحية المصحح، OR: 31.66؛ فترة الثقة 95%، CI: 22.03 – 45.48) بين النساء اللاتي سعين إلى الرعاية التوليدية الطارئة والشاملة. ومع مرور الوقت، قلت قوة الارتباط بين الرعاية التوليدية الماهرة ووفيات الأمهات نظراً لأن المزيد من النساء سعين إلى هذه الرعاية. وكانت معدلات الوفيات المحيطة بالولادة هي الأخرى أعلى بين من سعين إلى الإشراف الماهر على الولادة مقارنة بمن لم تسعين إلى هذه الرعاية، بالرغم من أن قوة الارتباط كانت أضعف بكثير.

الاستنتاج

نظراً لارتفاع نسبة وفيات الأمهات ومعدل الوفيات المحيطة بالولادة بين النساء اللاتي سعين إلى الرعاية التوليدية، هناك حاجة للمزيد لضمان حصول النساء ومواليدهن على رعاية توليدية فعّالة وفي وقتها المناسب. ويتطلب الحد من الوفيات المحيطة بالولادة استراتيجيات مثل الاكتشاف المبكر والتدبير العلاجي للمشاكل الصحية أثناء الحمل.

Résumé

Objectif

Étudier la nature de la relation entre le recours à une assistance qualifiée vers le moment de l'accouchement et la mortalité maternelle et périnatale.

Méthodes

Nous avons analysé les données de surveillance sanitaire et démographique recueillies entre 1987 et 2005 par le Centre international de recherche sur les maladies diarrhéiques (ICDDR, B) de Matlab, au Bangladesh.

Résultats

Sur la période étudiée, l'étude a enregistré 59 165 grossesses, 173 décès maternels, 1661 mortinaissances et 1418 décès néonatals précoces dans sa zone de desserte. Pendant cette période, la fréquence du recours à une assistance qualifiée est passée de 5,2 à 52,6 %. Plus de la moitié (57,8 %) des femmes décédées en couche et un tiers (33,7 %) de celles ayant subi un décès périnatal (mortinaissance ou décès néonatal précoce) avaient sollicité une assistance qualifiée. La mortalité maternelle était faible parmi les femmes n'ayant pas recouru à des soins qualifiés (160 pour 100 000 grossesses) et était près de 32 fois supérieure (Odds ratio ajusté, OR : 31,66 ; intervalle de confiance à 95 %, IC : 22,03-45,48) chez les femmes ayant reçu des soins obstétricaux d'urgence complets. Au cours du temps, la force de l'association entre soins obstétricaux qualifiés et mortalité maternelle a diminué car davantage de femmes sollicitaient de tels soins. Les taux de mortalité périnatale étaient également plus élevés pour les femmes qui avaient bénéficié de ces soins que pour celles qui n'en n'avaient pas reçu, même si la force de cette association était nettement plus faible.

Conclusion

Compte tenu des niveaux élevés du ratio de mortalité maternelle et du taux de mortalité périnatale pour les femmes ayant sollicité des soins obstétricaux, il faut œuvrer davantage pour s'assurer que les femmes et leurs nouveau-nés bénéficient de soins obstétricaux efficaces et administrés en temps utile. Réduire la mortalité périnatale nécessitera l'application de stratégies telles que la détection et la prise en charge précoces des problèmes de santé pendant la grossesse.

Resumen

Objetivo

Estudiar la naturaleza de la relación entre el recurso a asistencia calificada en torno al momento del parto y la mortalidad materna y perinatal.

Métodos

Analizamos datos del sistema de vigilancia sanitaria y demográfica reunidos entre 1987 y 2005 por el Centro Internacional de Investigación de Enfermedades Diarreicas de Bangladesh en Matlab, Bangladesh.

Resultados

El estudio registró 59 165 embarazos, 173 muertes maternas, 1661 defunciones prenatales y 1418 muertes neonatales tempranas en su zona de influencia a lo largo del periodo de estudio. Durante ese tiempo, el recurso a asistencia calificada durante el parto aumentó del 5,2% al 52,6%. Más de la mitad (57,8%) de las mujeres que murieron y una tercera parte (33,7%) de las que tuvieron un problema de mortalidad perinatal (esto es, de los casos de mortinatalidad o mortalidad neonatal precoz) habían buscado asistencia especializada. La mortalidad materna fue baja entre las mujeres que no buscaron atención especializada (160 por 100 000 embarazos) y unas 32 veces superior (razón de posibilidades ajustada, OR: 31,66; intervalo de confianza del 95%: 22,03-45,48) entre las que entraron en contacto con servicios de atención obstétrica integral de emergencia. A lo largo del tiempo, la solidez de la relación entre atención obstétrica calificada y mortalidad materna disminuyó paralelamente al aumento del número de mujeres que buscaban atención. La mortalidad perinatal fue también más alta entre las mujeres que buscaron atención especializada que entre las que no lo hicieron, aunque en este caso la asociación fue mucho más débil.

Conclusión

Considerando los elevados valores de las razones de mortalidad materna y las tasas de mortalidad perinatal entre las mujeres que buscaron atención obstétrica, es necesario hacer un mayor esfuerzo para lograr que las mujeres y sus recién nacidos reciban una atención obstétrica eficaz a su debido tiempo. Para reducir la mortalidad perinatal se requerirán estrategias como la detección y el tratamiento tempranos de los problemas de salud durante el embarazo.

Introduction

The United Nation’s fourth and fifth Millennium Development Goals set targets for reducing child and maternal mortality by 2015.1 Child survival has shown some improvement globally, but progress has been slow for maternal, perinatal and neonatal health.2,3 Better monitoring and management of labour, delivery and the immediate postpartum period are thought to be critical to reducing rates of maternal mortality and perinatal mortality (i.e. a stillbirth or early neonatal death).2–6 Ensuring that labour and the first 24 hours postpartum are managed by a skilled care provider is one of the keys to achieving this aim.4,5

There have been few rigorous studies of the effects on maternal or perinatal mortality of various levels and configurations of skilled care or of the size of the effect on maternal or perinatal mortality that could be achieved by such care.4,7–9 Ecological studies have shown that populations with a greater per cent of births attended by a skilled professional also have higher maternal and perinatal mortality,9–12 but causal inferences cannot be robustly drawn.13 Few studies have assessed whether the use of a skilled provider reduces the risk of maternal or perinatal death for individual women and their offspring.13,14

This paper examines whether skilled attendance around the time of birth is associated with the risk of maternal and perinatal death for individual women and neonates. The Matlab study area in rural Bangladesh offers a unique opportunity to examine this relationship because the uptake of skilled care at birth improved dramatically over the study period and prospective surveillance through the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR,B) ensures high-quality data on maternal and perinatal mortality.15–17 By separating basic from comprehensive obstetric care and by examining the outcomes for both mother and neonate, we provide insights into the nature of the relationship between skilled birth attendance and health outcomes around the time of birth.

Methods

Study population

The study was conducted in Matlab, a rural area in Bangladesh, south-east of the capital Dhaka. In this predominantly Muslim society, women are traditionally restricted from seeking care outside their home, although dramatic changes occurred over the study period.18,19 The study took place in the ICDDR,B service area, which has a population of about 110 000.20

Safe motherhood programme

In 1987, a safe motherhood programme was introduced in the ICDDR,B surveillance area.15 The programme aimed to increase the coverage of home births involving a skilled professional. Eight trained midwives were posted in the area, and transport was provided for the women who were referred to a basic obstetric care facility in Matlab town, or to a private or public comprehensive obstetric care facility in a town outside the ICDDR,B area. The midwives provided antenatal care, basic obstetric care and neonatal care, including monitoring the progress of labour, drying and wrapping the baby, placing the baby on the mother’s breast to facilitate immediate breastfeeding, providing antibiotic prophylaxis for eye infections, and administering suction to clear the neonate’s airway when necessary. The home-birth strategy continued until 1996, after which it was redesigned to be facility based.16 Between 1996 and 2001, all four health centres were upgraded and equipped to perform basic obstetric care; home births with midwives were no longer offered.16 In the health centres, midwives routinely used the partograph (a tool for assessing the progress of labour and identifying when intervention is necessary) for delivery, actively managed the third stage of labour to prevent postpartum haemorrhage, and administered sedatives for management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia and antibiotics for infection control. At the Matlab clinic during the same period, care was more advanced; it included magnesium sulfate for pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, assisted deliveries, manual removal of the placenta and blood transfusion.

Data collection

We used multiple data sources collected by the ICDDR,B between 1987 and 2005; these included the routine health and demographic surveillance system (HDSS), periodic censuses, special studies on maternal mortality, a geographic information system and the safe motherhood programme.

The HDSS maintains data on all births, deaths, marriages and migrations since 1966, and each individual has a unique identifier.20 From the HDSS we extracted data on all stillbirths and live births, birth order and maternal age. Information on maternal deaths was available from studies that involved detailed verbal autopsies of all deaths in women of reproductive age.15,16 Data on asset ownership and maternal education were obtained from the 1996 and 2005 censuses. Wealth was measured by an asset index.16 Linear distance from the health centre to the woman’s home was obtained from the geographic information system.

Data on care seeking around the time of pregnancy termination, birth or death were obtained from programme records. For each pregnancy, the midwives maintain a record (in the form of a card) of all visits performed. Between 1987 and 1993, this card was given only to women who had seen a midwife at any time during or after pregnancy. From 1996 onwards, community workers completed a card for all pregnant women in their area and, if contacted, the midwife completed relevant sections. The cards included information on the place of birth, attendant at delivery and referral. Service use information from the cards was supplemented by data available from registers kept in the Matlab clinic (1987–2005) and by the midwives (1996–2005) and from a study on met need for life-saving surgery conducted between 1990 and 2001.19 For maternal deaths, additional information on care seeking before death was available from verbal autopsies.20

Definitions

Women were classified as having received basic obstetric care if the ICDDR,B midwife was present at any time during pregnancy termination, labour, delivery or the immediate postpartum period, or near the time of death, whether or not they actually assisted with the termination or birth. Similarly, women were classified as having received care from a comprehensive obstetric care facility if they received care from private or public hospitals outside the ICDDR,B surveillance area near the time of pregnancy termination, labour, delivery or the immediate postpartum period, or near the time of death. For maternal mortality we repeated the analysis, restricting the sample to women who had given birth.

A maternal death was defined as the death of a woman while pregnant or within 90 days of pregnancy termination, irrespective of pregnancy duration or termination method. A stillbirth was defined as a death of a fetus after 28 weeks’ gestation but before delivery of the baby’s head. An early neonatal death was defined as the death of a live born infant within one week (seven complete days) after birth. Perinatal deaths included stillbirths and early neonatal deaths.

Data analysis

Denominators for the maternal mortality ratio, stillbirth rate and early neonatal mortality rate included all pregnancies, all births and all live births, respectively, between 1987 and 2005. Multiple births were recorded as a single pregnancy, and the outcome was considered a perinatal death if one or more of the neonates was stillborn or died within one week of birth. We estimated odds ratios (ORs) by logistic regression, using Stata version 10 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). We present crude and adjusted ORs, adjusted for year of birth, distance to basic obstetric facility, asset quintile, maternal education, maternal age and birth order. For stillbirths and early neonatal mortality, we adjusted the analysis for clustering of births in one woman. We also examined whether the relationship between skilled care and mortality changed over time by introducing an interaction term between skilled care and time of pregnancy termination or birth.

Results

The study sample consisted of 59 165 pregnancies, 173 maternal deaths, 1661 stillbirths and 1418 early neonatal deaths between 1987 and 2005. The stillbirth rate (3074 per 100 000 births) and early neonatal mortality rate (2707 per 100 000 live births) were much higher than the maternal mortality ratio (292 per 100 000 pregnancies). Nearly two-thirds of the women who died (63.0%) did so after giving birth, and more than one-third (41.3%) of those who gave birth and died had a perinatal death (stillbirth in 30.3% and early neonatal death in 11.0%).

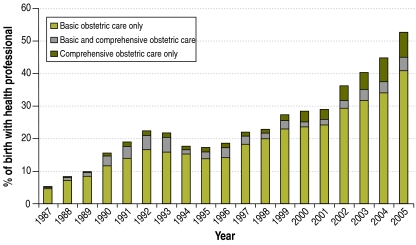

Uptake of skilled care at birth increased dramatically over the study period, from 5.2% in 1987 to 52.6% in 2005 (Fig. 1). Most contacts with a skilled professional were at the basic obstetric care level, but birth in a comprehensive obstetric care facility also increased considerably over the study period, from 0.5% in 1987 to 11.7% in 2005. The proportion of women who sought care from a comprehensive obstetric care facility without prior contact at the basic obstetric care level also increased significantly, from 35.3% in 1987 to 71.3% in 2005 (P = 0.002).

Fig. 1.

Trend in seeking basic and comprehensive obstetric care among women in the ICDDR,B service area, Matlab, Bangladesh, 1987–2005

ICDDR,B, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh.

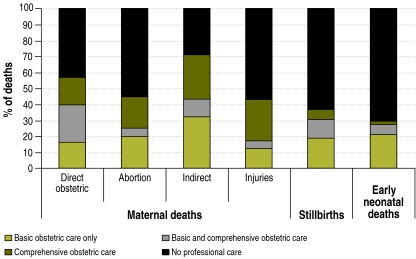

The proportion of women seeking skilled care around the time of pregnancy termination, birth or death was much higher among those who suffered a maternal death than among those who experienced a perinatal death. More than half (57.8%) of the women who died had sought care from a skilled professional (37.0% from a comprehensive obstetric care facility and 20.8% from a basic obstetric care facility only), compared to only one-third (33.7%) of women who experienced a perinatal death (13.3% from a comprehensive obstetric care facility and 20.5% from a basic obstetric care facility only). The proportions seeking care were higher for women who had a stillbirth (37.3%) than for women who experienced an early neonatal death (29.6%) (P = 0.000) and differed somewhat by cause of maternal death (Fig. 2). Skilled care seeking before death was lowest among women dying after a pregnancy termination (45.0%) or injury (43.5%), and highest among those dying from indirect causes (71.7%) (P = 0.073) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Care seeking and maternal death, stillbirth or early neonatal death, Matlab, Bangladesh, 1987–2005

As shown in Table 1, maternal mortality was remarkably low among women who did not seek skilled care (160 per 100 000 pregnancies) but was extremely high among those seeking care from a comprehensive obstetric care facility (2188 per 100 000 pregnancies; crude OR: 13.97 (95% CI: 9.97–19.59)). Stillbirth and early neonatal death rates also varied depending on where care was sought, although the gap between those seeking care from a comprehensive obstetric care facility and those not seeking skilled care was relatively small (OR: 5.07 for stillbirths and 2.08 for early neonatal deaths). These patterns became more pronounced after adjusting the analysis for year of birth, distance to basic obstetric facility, asset quintile, maternal education, maternal age and birth order (Table 1). Restricting the analysis of maternal mortality to women who died after giving birth did not change the findings (crude OR: 1.96; 95% CI: 1.19–3.23 for women seeking basic obstetric care; crude OR: 13.66; 95% CI: 8.92–20.93 for women seeking comprehensive obstetric care).

Table 1. Maternal mortality, stillbirth and early neonatal mortality, in rates and absolute figures, and corresponding odds ratios for highest level of care at pregnancy termination, birth or death, Matlab, Bangladesh, 1987–2005.

| No skilled obstetric care | Basic obstetric care only | Comprehensive obstetric care | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal mortality | |||

| Maternal mortality ratioa (no. of deaths) | 160 (73) | 340 (36) | 2188 (64) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 2.13 (1.43–3.18) | 13.97 (9.97–19.59) |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | 1.00 | 3.92 (2.63–6.01) | 31.66 (22.03–45.48) |

| Stillbirth | |||

| Stillbirth ratec (no. of deaths) | 2528 (1042) | 3143 (323) | 11 653 (296) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.25 (1.09–1.42) | 5.07 (4.42–5.81) |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | 1.00 | 1.51(1.31–1.73) | 6.61 (5.62–7.79) |

| Early neonatal mortality | |||

| Early neonatal mortality rated (no. of deaths) | 2484 (998) | 3084 (307) | 5036 (113) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.25 (1.10–1.42) | 2.08 (1.70–2.55) |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | 1.00 | 1.47 (1.27–1.69) | 2.69 (2.16–3.37) |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

a Maternal deaths per 100 000 pregnancies.

b Adjusted for year of birth, distance to basic obstetric facility, asset quintile, maternal education, maternal age and birth order.

c Stillbirths per 100 000 births.

d Early neonatal deaths per 100 000 live births.

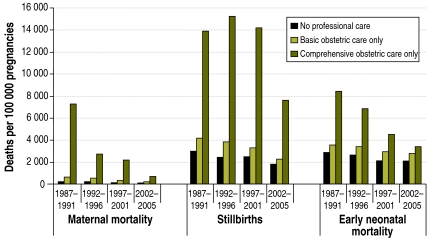

The associations between maternal mortality and early neonatal mortality and care seeking around pregnancy termination, birth or death differed by year of birth (interaction between care seeking and year of birth: P = 0.0642 for maternal mortality and 0.0520 for early neonatal deaths), although there was no interaction between care seeking and stillbirths (P = 0.3186). In the period 1987–91, when few women sought skilled care around the time of labour and delivery, mortality among those seeking care from a comprehensive obstetric care facility was extremely high (maternal mortality 7263 per 100 000 pregnancies and early neonatal mortality 8389 per 100 000 live births) (Table 2, Table 3, Fig. 3). As more women sought care at these facilities, mortality among those seeking care from a comprehensive obstetric care facility gradually declined, but it was still high in the later years of the programme (maternal mortality 653 per 100 000 pregnancies and early neonatal mortality 3398 per 100 000 live births) (Table 2, Table 3). In 2002–2005, there were low levels of maternal mortality (68 per 100 000 pregnancies) among women giving birth at home without a skilled professional, but stillbirths and early neonatal mortality remained high (stillbirths 1766 per 100 000 births; early neonatal mortality 2101 per 100 000 live births) (Table 4, Table 3).

Table 2. Maternal mortality by year of birth and highest level of care at pregnancy termination, birth or death, Matlab, Bangladesh, 1987–2005.

| Year of birth | No skilled obstetric care |

Basic obstetric care only |

Comprehensive obstetric care |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of pregnancies | Maternal mortality ratioa (95% CI) | % of pregnancies | Maternal mortality ratioa (95% CI) | % of pregnancies | Maternal mortality ratioa (95% CI) | |||

| 1987–1991 | 89.5 | 207 (141–294) | 8.3 | 644 (295–1223) | 2.1 | 7263 (4745–10 641) | ||

| 1992–1996 | 81.8 | 219 (143–321) | 14.1 | 538 (268–962) | 4.1 | 2707 (1548–4396) | ||

| 1997–2001 | 75.9 | 96 (48–172) | 20.2 | 296 (136–563) | 4.0 | 2174 (1158–3717) | ||

| 2002–2005 | 57.4 | 68 (22–158) | 31.9 | 171 (69–352) | 10.7 | 653 (299–1240) | ||

| Yearly trend | – | 0.92 (0.88–0.96) | – | 0.90 (0.85–0.96) | – | 0.85 (0.81–0.89) | ||

CI, confidence interval.

a Maternal deaths per 100 000 pregnancies.

Table 3. Early neonatal mortality by year of birth and highest level of care at pregnancy termination, birth or death, Matlab, Bangladesh, 1987–2005.

| Year of birth | No skilled obstetric care |

Basic obstetric care only |

Comprehensive obstetric care |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of live births | Early neonatal mortality ratea (95% CI) | % of live births | Early neonatal mortality ratea (95% CI) | % of live births | Early neonatal mortality ratea (95% CI) | |||

| 1987–1991 | 89.1 | 2869 (2592–3167) | 8.9 | 3901 (2927–5084) | 2.0 | 8389 (5503–1213) | ||

| 1992–1996 | 81.1 | 2602 (2306–2924) | 15.1 | 3359 (2607–4253) | 3.7 | 6804 (4730–9423) | ||

| 1997–2001 | 74.6 | 2090 (1819–2389) | 21.8 | 2932 (2352–3609) | 3.6 | 4490 (2835–6719) | ||

| 2002–2005 | 57.2 | 2101 (1761–2486) | 33.9 | 2766 (2263–3344) | 8.8 | 3398 (2351–4740) | ||

| Yearly trend | – | 0.97 (0.96–0.99) | – | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | – | 0.93 (0.90–0.96) | ||

CI, confidence interval.

a Early neonatal deaths per 100 000 live births.

Fig. 3.

Maternal mortality, stillbirths and early neonatal mortality by year and by care seeking patterns, Matlab, Bangladesh, 1987–2005

Table 4. Stillbirths by year of birth and highest level of care at pregnancy termination, birth or death, Matlab, Bangladesh, 1987–2005.

| Year of birth | No skilled obstetric care |

Basic obstetric care only |

Comprehensive obstetric care |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of births | Stillbirth ratea (95% CI) | % of births | Stillbirth ratea (95% CI) | % of births | Stillbirth ratea (95% CI) | |||

| 1987–1991 | 88.8 | 3015 (2732–3320) | 9.0 | 4170 (3166–5390) | 2.2 | 13 873 (10 229–18 393) | ||

| 1992–1996 | 80.5 | 2427 (2142–2740) | 15.2 | 3818 (3018–4765) | 4.3 | 15 210 (12 182–18 761) | ||

| 1997–2001 | 74.1 | 2456 (2163–2778) | 21.8 | 3297 (2683–4010) | 4.1 | 14 186 (11 265–17 631) | ||

| 2002–2005 | 56.8 | 1766 (1455–2123) | 33.8 | 2283 (1828–2816) | 9.3 | 7 612 (6 036–9 474) | ||

| Yearly trend | – | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | – | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | – | 0.95 (0.93–0.97) | ||

CI, confidence interval.

a Stillbirths per 100 000 births.

Discussion

In this study, maternal and perinatal mortality were higher among women seeking skilled obstetric care around the time of pregnancy termination, birth or death than among women who did not seek such care. Mortality among those seeking care was particularly high in the early years of the safe motherhood programme, when few women sought skilled obstetric care. At that time, 7% of the women who sought care from a hospital died, and 21% had a stillbirth or lost their child within seven days of birth. As uptake of skilled obstetric care increased, more women and neonates survived, though maternal and perinatal mortality remained high among those seeking care from a hospital.

The high levels of maternal or perinatal mortality among those receiving skilled care is perhaps not surprising in settings where few births are managed by a skilled birth attendant. Similar patterns of high maternal mortality among those seeking care were seen in Nepal and Indonesia, where births involving a skilled birth attendant were only 8% and 33%, respectively.14,21 When uptake of skilled birth attendance or comprehensive obstetric care is low, women will only seek skilled care when they are ill, and they may do so too late for a midwife or doctor to be able to save the lives of the mothers or neonates. As coverage increases, more women who are less at risk will seek care; thus, average mortality in those seeking care will decrease.

Lack of timely and adequate care once women reach the health facility may also explain the high mortality among those seeking skilled obstetric care. In the last five years of the programme, when more than half of women sought care from a skilled professional, maternal mortality among those seeking care from hospitals was still over 600 per 100 000 pregnancies and more than 10% of the women lost their baby. This suggests that they may have received substandard care. Little is known about the quality of obstetric care in hospitals in Bangladesh, but there is some evidence of substandard care within public facilities.22,23 There are substantial constraints on human resources, and some staffing positions may be left unfilled. The costs of care to patients are high; patients invariably have to buy some medicines – particularly for obstetric surgery – and evidence-based practices, such as the use of magnesium sulfate or the partograph, are far from universal. The quality of care in private hospitals is not known, even though an increasing share of comprehensive obstetric care is covered by the private sector.24

Most stillbirths and early neonatal deaths occurred at home, without a skilled birth attendant. Since many such deaths are experienced by apparently healthy women, this raises important questions about how to best organize care for mothers, to ensure perinatal survival. The causes of stillbirths are largely unknown, while early neonatal deaths are mostly related to birth asphyxia, premature birth and low birth weight.3,6,9,17 Stillbirth and early neonatal mortality rates are falling in Matlab, but there is little evidence that this is related to the safe motherhood programme.17 Lack of antenatal care may be associated with stillbirths, although it is not clear which antenatal interventions are effective in preventing such deaths in a community setting.8 Although it seems plausible that nutritional interventions would be effective in reducing perinatal mortality in malnourished populations, robust studies of the effect of such interventions are lacking.8 Interventions known to be effective, such as malaria prophylaxis or treatment of maternal syphilis, do not apply to the population in Matlab because there is no malaria and the prevalence of sexually transmitted infections is low.25 Prevention of early neonatal deaths and stillbirths clearly represents an important area for research.

Observational data are susceptible to bias. However, the demographic surveillance data we used are likely to be accurate because of in-built rigorous supervision to ensure data quality. Stillbirths are notoriously difficult to quantify26 and thus may have been underreported; however, the prospective ascertainment of pregnancies (discussed below) will have helped to limit the underreporting. The rates of stillbirth, early and late neonatal death also match those reported in the region.6 We are confident that the study identified most pregnancy-related deaths because pregnancies are ascertained prospectively in Matlab and the families of all deceased women of reproductive age are interviewed; thus, few pregnancies are missed.15,16

We may have missed some data on women who gave birth in health facilities, particularly if the facility was far away from the surveillance area. In addition, not all private and public hospitals provided comprehensive obstetric care, particularly in the early years of the safe motherhood programme. Blood transfusion and Caesarean sections may be unavailable in some hospitals, and this may in part explain the high mortality rate seen. Moreover, private facilities often refuse to accept patients who are in a critical condition and instead refer them to public facilities, thereby further delaying care.

Lastly, the ICDDR,B services receive greater funding and supervision than parallel government services; thus, the findings may not be generalizable. However, a recent review of the literature found little evidence that giving birth with a skilled birth attendant reduces a woman’s risk of dying.27 In fact, in settings where access to care is low, birth with a skilled attendant appears to be associated with an increased risk of death, largely because the sickest women seek professional care.

ICDDR,B midwives were trained and equipped to use parenteral antibiotics, oxytocic drugs and sedatives for eclampsia; they were also trained to manually remove the placenta or retained products. Vacuum extraction was only performed in the large health centre in Matlab town. The quality of the actual care provided, however, is not known. Midwives found it difficult to perform adequately when care was given in the women’s home,28 and it is plausible that the shift to facility-based care may have resulted in improvements in the quality of care. The declining trends in maternal mortality among those seeking care from midwives supports this view.

We were unable to empirically verify the hypothesis that sicker women self-select into giving birth with a skilled birth attendant or in a health facility. Studies examining near-miss morbidity have shown that, in poor countries, most near-miss cases arrive at a health facility in a critical state, suggesting that the decision to seek skilled care is often made too late.29,30 One way to gain information about the self-selection process may be to examine the proportion of near-miss cases admitted in a critical state in relation to the proportion of births attended by a skilled professional. Furthermore, comparing maternal mortality among those planning to give birth with a skilled birth attendant (the so-called “booked women”)31 and those giving birth without a skilled attendant may account, at least in part, for the self-selection of women with medical problems into the group seeking skilled obstetric care. However, such data were not available to us.

The concurrent analysis of maternal and perinatal mortality has several advantages. First, it corroborates the fact that unborn infants and neonates are always at greater risk of dying than pregnant women or women who have just given birth, and that the combined burden of maternal and perinatal mortality is extremely high in Matlab, Bangladesh. Overall, 5% of pregnancies resulted in either the mother or the neonate dying, although this proportion declined over time (from 6% in 1987–91 to 4% in 2002–05; data not shown). Second, monitoring the mother and the neonate in a health facility for at least 24 hours after birth – as has been recommended for maternal health4 – will benefit both the mother and the neonate, provided the skilled birth attendants are knowledgeable and skilled in early neonatal care. Third, the concurrent analysis of maternal and perinatal mortality draws attention to the important role of antenatal care, which may be overlooked if only maternal outcomes are examined.4

Mothers and their neonates are at greatest risk of death in late pregnancy, during childbirth and within the first 24 hours after birth. Offspring of mothers who die are also at greatest risk of stillbirth and early neonatal death and need to be managed by a skilled health professional in a health facility. Many women with life-threatening conditions seek professional care from a health facility, even when skilled-care seeking for birth is low.2 On the other hand, women whose babies died often do not seek skilled obstetric care. Thus, to achieve a healthy outcome for both mothers and neonates, efforts to ensure timely access to adequate emergency obstetric care will have to be supported by early detection and management of problems during pregnancy.

Acknowledgements

ICDDR,B acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of the Department for International Development, the United States Agency for International Development and the Belgian Directorate General for Development Cooperation to the Centre’s research efforts.

Funding:

This study was funded by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID), grant number GR#00335 and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), grant number GR#00089. The salary of Dr Chowdhury and Dr Ronsmans was supported by DFID through a Research Programme Consortium, grant number GR#00458. The verbal autopsies between 1990 and 2001 were funded by the Belgian Directorate General for Development Cooperation (BDGDC), grant number GR#00052.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Sachs JD, McArthur JW. The Millennium Project: a plan for meeting the Millennium Development Goals. Lancet. 2005;365:347–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17791-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ronsmans C, Graham WJ, Lancet Maternal Survival Series Steering Group Maternal mortality: who, when, where and why. Lancet. 2006;368:1189–200. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69380-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J, Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team Four million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet. 2005;365:891–900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell OMR, Graham WJ, The Lancet Maternal Survival Series Steering Group Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet. 2006;368:1284–1299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, Taghreed A, Walker N, de Bernis L, Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet. 2005;365:977–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baqui AH, Darmstadt GL, Williams EK, Kumar V, Kiran TU, Panwar D, et al. Rates, timing and causes of neonatal deaths in rural India: implications for neonatal health programmes. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:706–13. doi: 10.2471/BLT.05.026443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatt L, Stanton C, Adisasmita A, Ronsmans C. Did professional attendance at home births improve early neonatal survival in Indonesia? Health Policy Plan. 2009;24:270–8. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL, Hasan BS, Haws RA. Community-based interventions for improving perinatal and neonatal health outcomes in developing countries: a review of the evidence. Pediatrics. 2005;115:519–617. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woods R. Long-term trends in fetal mortality: implications for developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:460–6. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.043471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anand S, Bernighausen T. Human resources and health outcomes: cross-country econometric study. Lancet. 2004;364:1603–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClure EM, Goldenburg RL, Bann CM. Maternal mortality, stillbirth and measures of obstetric care in developing and developed countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;96:139–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ronsmans C, Etard JF, Walraven G, , Høj L, Dumont A, de Bernis L, et al. Maternal mortality and access to obstetric services in West Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:940–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham W, Bell J, Bullough C. Can skilled attendance at delivery reduce maternal mortality in developing countries? Safe motherhood strategies: a review of the evidence. Stud Health Serv Organ Policy. 2001;17:97–130. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ronsmans C, Scott S, Qomariyah SN, Achadi E, Braunholz D, Marshall T, et al. Midwife-led community care and maternal mortality in Indonesia. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:416–23. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.051581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fauveau V, Stewart K, Khan SA, Chakraborty J. Effect on mortality of community-based maternity-care programme in rural Bangladesh. Lancet. 1991;338:1183–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92041-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chowdhury ME, Botlero R, Koblinsky M, Saha S, Dieltiens G, Ronsmans C. Determinants of reduction in maternal mortality Matlab, Bangladesh: a 30-year cohort study. Lancet. 2007;370:1320–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61573-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ronsmans C, Chowdhury ME, Alam N, Koblinsky M, El Arifeen S. Trends in stillbirths, early and late neonatal mortality in rural Bangladesh: the role of socio-demographic factors and health interventions. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008;22:269–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fauveau V, ed. Matlab: women children and health Dhaka: ICDDR,B and Centre for Health and Population Research; 1994 (Special Publication No. 35). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dieltiens G, Dewan H, Botlero R, Alam N, Chowdhury E, Ronsmans C. Pregnancy-related mortality and access to obstetric services in Matlab, Bangladesh Tours: International Union for the Scientific Study of Population; 2005.

- 20.International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research. Health and demographic surveillance system Matlab: registration of health and demographic events. Dhaka: ICDDR,B; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christian P, Katz J, Wu L, Kimbrough-Pradhan E, Khatry SK, LeClercq SC, et al. Risk factors for pregnancy-related mortality: a prospective study in rural Nepal. Public Health. 2008;122:161–72. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koblinsky M, Anwar I, Mridha MK, Chowdhury ME, Botlero R. Reducing maternal mortality and improving maternal health: Bangladesh and MDG 5. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26:280–94. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v26i3.1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anwar I, Kalim N, Koblinsky M. Quality of obstetric care in public-sector facilities and constraints to implementing emergency obstetric care services: evidence from high and low performing districts of Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009;27:139–55. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v27i2.3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institute of Population Research and Training. Mitra and Associates, and Macro International. Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2007 Dhaka and Calverton: National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, and Macro International; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawkes S, Morison L, Chakraborty J, Gausia K, Ahmed F, Islam SS, et al. Reproductive tract infections: prevalence and risk factors in rural Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:180–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanton C, Lawn JE, Rahman H, Wilczynska-Ketende K, Hill K. Stillbirth rates: delivering estimates in 190 countries. Lancet. 2006;367:1487–94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68586-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott S, Ronsmans C.The relationship between birth with a health professional and maternal mortality in observational studies: a review of the literature. Trop Med Int Health 2009141523–33.PMID:19793070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blum LS, Sharmin T, Ronsmans C. Performing home-based deliveries: understanding the perspective of skilled birthing attendants. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14:51–60. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)27234-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adisasmita A, Deviany PE, Nandiaty F, Stanton C, Ronsmans C. Obstetric near miss and deaths in public and private hospitals in Indonesia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008;8:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Filippi V, Ronsmans C, Gohou V, Goufodji S, Lardi M, Sahel A, et al. Maternity wards or emergency obstetric rooms? Incidence of near-miss events in African hospitals. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:11–6. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pokharel HP, Lama GJ, Banerjee B, Paudel LS, Pokharel PK. Maternal and perinatal outcome among the booked and unbooked pregnancies from catchments area of BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2007;5:173–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]