Abstract

Chemokines promote lymphocyte motility by triggering F-actin rearrangements and inducing cellular polarization. Chemokines can also enhance cell-cell adhesion and co-stimulate T cells. Here we establish a requirement for the actin-bundling protein L-plastin (LPL) in CCR7- and S1P1-mediated T cell chemotaxis using LPL−/− mice. Disrupted motility of mature LPL−/− thymocytes manifested in vivo as diminished thymic egress. Two-photon microscopy of LPL−/− lymphocytes revealed reduced velocity and motility in lymph nodes. Defective migration resulted from defective cellular polarization following CCR7 ligation, as CCR7 did not polarize to the leading edge in chemokine-stimulated LPL−/− T cells. However, CCR7 signaling to F-actin polymerization and CCR7-mediated co-stimulation was intact in LPL−/− lymphocytes. The differential requirement for LPL in CCR7-induced cellular adhesion and CCR7-induced motility allowed assessment of the contribution of CCR7-mediated motility to thymocyte positive selection and lineage commitment. Results suggest that normal motility is not required for CCR7 to function in positive selection and lineage commitment. We thus identify LPL as a molecule critical for CCR7-mediated motility but dispensable for early CCR7 signaling. The requirement for actin-bundling by LPL for polarization reveals a novel mechanism of regulating actin dynamics during T cell motility.

Keywords: T cells, chemokines, actin-binding proteins, chemotaxis

Introduction

Lymphocyte motility is critical for the development and function of T cells. Receptors for chemoattractants, such as CCR7 and the receptor for sphingosine-1-phosphate, S1P1, regulate appropriate migration of T cells through and out of lymphoid organs. In thymic development, CCR7 is upregulated during positive selection and is thought to mediate the cortico-medullary migration of positively-selected thymocytes (1). Overexpression of CCR7 promotes commitment to the CD8 single positive (SP) lineage (2). CCR7−/− thymocytes also demonstrate defective negative selection (3). Following maturation of SP thymocytes, CCR7 and S1P1 enable thymic egress (4–10). In the periphery, CCL19 and CCL21, the ligands for CCR7, decorate dendritic cells in lymph nodes and induce the intranodal motility of T cells. CCR7−/− T cells demonstrate defects in intranodal velocity and motility (6, 11, 12). In addition to promoting T cell motility, CCR7 can mediate TCR costimulation by increasing T cell-APC conjugation (13, 14). Whether CCR7 participates in positive selection and/or lineage commitment through increasing cellular adhesion or inducing thymocyte motility is currently unclear.

T cells move towards chemoattractants by polarizing and protruding lamellipodia at the leading edge, while formation of uropods at the trailing edge provide contractile force (15–17). Chemoattractant receptors signal through the activation of small GTPases, such as Rac, that trigger actin polymerization, formation of lamellipodia and subsequent T cell polarization. Several cytoskeletal elements, such as mDia1 and coronin, have been identified as molecules required for actin polymerization and subsequent lymphocyte motility (18–22). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying actin rearrangement and cellular polarization have not been fully elucidated.

Although the actin-bundling protein L-plastin (LPL) is upregulated during positive selection and is expressed in mature T cells (23), participation of LPL in T cell motility has not been previously described. LPL is one of three isoforms of the widely-conserved actin-bundling protein plastin (also called fimbrin) found in humans. LPL expression is restricted to leukocytes and some transformed cell lines (24). Plastin-mediated bundling of actin filaments enables the maintenance of structures such as lamellipodia and filopodia (25). Different cell types use LPL in a variety of cellular processes. We have previously described a requirement for LPL in integrin signaling in neutrophils using LPL−/− mice. Generation of an adhesion-dependent respiratory burst was absent in LPL−/− neutrophils, while integrin-mediated adhesion and neutrophil chemotaxis to fMLP was intact (26). In contrast to its function in neutrophils, ectopically expressed LPL has been linked to motility in cancer cells through stabilization of filopodia (27).

Here we report that LPL is required for CCR7- and S1P1-induced motility of SP thymocytes and naive T cells, without a role in chemokine-induced cell adhesion. LPL−/− thymocytes failed to exit the thymus normally, leading to increased mature single-positive thymocytes in LPL−/− mice. LPL−/− mature T cells demonstrated defects in intranodal motility strikingly similar to those of CCR7−/− T cells. Despite normal expression of the receptors CCR7 and S1P1, LPL−/− thymocytes exhibited diminished chemotaxis in vitro towards the ligands CCL19 and S1P, and mature LPL−/− T cells did not move efficiently towards CCL19. Defective migration resulted from defective cellular polarization following CCR7 ligation. LPL is thus required for the establishment or maintenance of cellular polarity that enables directed chemotaxis, without being required for initial adhesion that is required for cell motility.

The differential requirement for LPL in CCR7-induced cellular adhesion and CCR7-induced motility allowed assessment of the contribution of CCR7-mediated motility to positive selection and lineage commitment. Results suggest that normal motility is not required for CCR7 to function in positive selection and lineage commitment. We thus identify LPL as a molecule critical for CCR7-mediated motility but dispensable for early CCR7 signaling. Furthermore, the requirement for the actin-bundling protein LPL for polarization following CCR7 ligation reveals a novel mechanism of regulation of actin dynamics, at a step downstream from actin polymerization and the cytoskeletal changes required for adhesion, but nonetheless necessary for T cell motility.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The generation of mice deficient for LPL has been previously described (26). Mice were back-crossed in to generate LPL−/− mice on a B6 background. n3.L2 transgenic mice are on the background B6.AKR-H-2k (B6.K) (28). The n3.L2 TCR recognizes the d allele of the hemoglobin peptide 64–76 bound to I-Ek. LPL−/− mice were crossed with established TCR transgenic lines to generate n3.L2 LPL−/− mice (H-2k) and OT-1 LPL−/− mice (H-2b). B6.AKR mice congenic at the Ly5 locus (B6.AKR.Ly5.1) were generated and RAG1−/− mice (C57BL/6J-RAG1tm1 Mom) were originally obtained from the The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). C57BL/6 mice expressing YFP under the CD11c promoter (CD11c-YFP mice) were originally obtained from M. Nussenzweig (29). All animals were maintained in specific pathogen-free housing and all experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee.

Flow cytometry

The antibody against S1P1 was generously provided by J. Cyster (UCSF, San Francisco, CA) (30). The clonotypic Ab (Cab) for the n3.L2 TCR has been described (31). Directly conjugated antibodies were commercially available: CD8-FITC, CD45.2-allophycocyanin (APC), CD4-APC/AlexaFluor750, CD45.1-PE/Cy7 (eBioscience), Vα2-FITC, CD24-PE, CD62L-PE, CD69-PE, CCR7-PE, CD4-APC, (Biolegend), β7-integrin-PE, CD8-PerCP (BDBiosciences). Staining for CCR7 was performed either at RT or at 37°C, according to manufacturer’s recommendations. All other staining was performed on ice. Cells were acquired either with FACScan, FACSCalibur, or FACSCanto (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar Inc., Ashland, OR).

Intrathymic FITC injection

Intrathymic FITC injections were performed as described (32), with injection of 10 µl of FITC (1 mg/ml in sterile PBS) into one lobe of the directly visualized thymus of anesthetized mice aged 6–10 wks. Thymus, lymph nodes, spleens and 100 µl of blood were harvested 48 hours after injection. Cell numbers were counted by hemocytometer and subpopulations and FITC labeling determined by flow cytometry. To control for the variability intrinsic to intrathymic injection, data are presented as percentages normalized to the total number of FITC+ thymocytes and peripheral cells isolated. Percentages were calculated by dividing the number of cells per organ, gated as indicated, by the sum total number of equivalently gated cells from the thymus, lymph nodes, spleen and blood from each mouse. Each experiment was performed on a single pair of age-matched mice with the indicated number of replicate experiments.

Transwell assays

Transmigration assays were performed as described (8) using 5 µM transwell filters (Corning Costar, Lowell, MA) with CCL19 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or S1P (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at the indicated concentrations. After incubation for 3 h at 37°C, cells were recovered from the lower chamber and counted using a hemocytometer with subpopulations determined by flow cytometry. Percentage of migrated cells was determined by dividing the number of migrated cells, gated as indicated, by the total number of equivalently gated input cells.

Two photon microscopy

CD8+ T cells were purified from the lymph nodes of OT-1 WT and OT-1 LPL−/− mice by MACS-bead negative selection (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn, CA), then labeled for 30 m at 37°C with 20–50 µM CMAC or 10 µM CMTPX (Invitrogen). In the experiment depicted in 4a, OT-1 WT cells were labeled blue (CMAC) and OT-1 LPL−/− T cells were labeled red (CMTPX). In a replicate experiment, OT-1 WT T cells were labeled red (CMTPX) and OT-1 LPL−/− T cells were labeled blue (CMAC) without any alteration in results. T cells (3 × 106–20 × 106) were resuspended in 200 µl of PBS, adoptively transferred by tail vein injection into CD11c-YFP mice (29) and allowed to home for 2 hours. Explanted lymph nodes were secured to coverslips with a thin film of VetBond (3M) and placed in a flow chamber and maintained at 37°C by perfusion with warm, high-glucose DMEM bubbled with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Time-lapse imaging was performed with a custom-built two-photon microscope, fitted with two Chameleon Ti:Sapphire lasers (Coherent) and an Olympus XLUMPlanFI 20× objective (water immersed; numerical aperture, 0.95) and controlled and acquired with ImageWarp (A&B software). For imaging of YFP, the excitation wavelength was 890–915 nm; for CMTPX and CMAC, 780–800 nm was used. Signals from fluorescent dyes and YFP were separated by dichroic mirrors (490 nm, 515 nm, and 560 nm). To create time-lapse sequences, we typically scanned with 31 Z-steps of 2.5 µm each at 45–55 s intervals for up to 60 min. For data analysis, cells were detected based on fluorescence intensity and cell tracks obtained with Volocity (Improvision) or Imaris (Bitplane) software. Only cells that could be tracked for at least 8 time points were included in the analysis. The median of instantaneous velocities in each cell track was reported as the velocity for that cell. Motility coefficients (mm2 min−1) were calculated for individual tracks by linear regression of displacement2 versus time plots with T Cell Analysis (John Dempster, University of Strathclyde).

Generation of bone marrow chimeras

Bone marrow was harvested from WT and LPL−/− mice, mixed in a 1:1 ratio and injected retro-orbitally into sublethally irradiated (500 rads) RAG1−/− mice. After 5–6 wks, mice were sacrificed and thymocytes, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, lymph node cells and splenocytes were assessed for expression of CD4, CD8, CD45.1, CD45.2, CD69, and CD24 by flow cytometry.

Rac assays

CD4+ T cells isolated from WT and LPL−/− mice were rested overnight in reduced serum medium (OptiMem), then stimulated with CCL19 and CCL21 (100 ng/ml; R&D Systems) for 15 s. Cell lysates were generated and assayed for GTP-Rac using the Rac1,2,3 Activation Assay G-LISA kit (Cytoskeleton Inc., Denver, CO).

F-actin content

CD4+ T cells were isolated from lymph nodes with magnetic beads (Miltenyi) and were stimulated in suspension with CCL19 (100 ng/ml). Thymocytes were stained with CD8-PerCP and CD4-APC and sorted (FACSAria) to isolate CD4SP cells, which were then stimulated in suspension with CCL19 and CCL21 (100 ng/ml each). Cells were fixed in 3.6% paraformaldehyde, then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X 100. F-actin content was determined by incubation with AlexaFluor488-phalloidin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) followed by flow cytometry (33).

Cell conjugation assays

Cell conjugation assays were performed as described (13) with minor modifications. CH27 B cells (H-2a, I-Ek) were used as antigen-presenting cells (34). MACS-bead purified CD4+ T cells from n3.L2 WT and n3.L2 LPL−/− mice were labeled with CellTrace Far Red DDAO (Invitrogen) and CH27 cells were labeled with CFSE (Invitrogen). Cells were mixed and incubated with or without Hb(64–76) peptide, with or without CCL21 (100 ng/ml), and with or without blocking anti-LFA-1 antibody (anti-CD11a clone M17/4; Biolegend; 10 µg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and percentage of T cells that formed conjugates determined by flow cytometry.

CD69 upregulation

The agonist Hb(64–76) peptide, sequence GKKVITAFNEGLK, was synthesized, purified, and analyzed as previously described (31). MACS-bead purified CD4+ T cells isolated from n3.L2 WT and n3.L2 LPL−/− lymph nodes were incubated overnight with congenic splenocytes with or without the indicated concentration of Hb peptide and with or without the chemokines CCL21 or CCL19 (100 ng/ml). Upregulation of CD69 on n3.L2+ CD4+ T cells was assessed by flow cytometry.

Confocal microscopy

Coverslips were coated with 10 µg/ml rmICAM-1/Fc chimera (R&D Systems). Cells were incubated on coated coverslips with or without CCL19 as indicated, then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 m at RT. Cells were stained with anti-CD43 (unconjugated; BD Pharmingen) or anti-CCR7 (either unconjugated (eBioscience) or biotinylated (Biolegend)) for a minimum of 30 min at room temperature prior to permeabilization. Either goat anti-rat Ig AlexaFluor546 (Invitrogen) or streptavidin-AlexaFluor546 was used as a secondary. Cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 4–5 min at RT. Actin was stained with AlexaFluor488-phalloidin (Invitrogen). LPL was stained with mAb 12A2 (16.5 µg/ml). The mAb 12A2 was generated by immunizing LPL−/− mice with recombinant human LPL and screened for binding to recombinant murine LPL by ELISA. Specificity of binding was confirmed by immunoblot and immunofluorescence, with WT and LPL−/− cells as positive and negative controls (data not shown). The secondary antibody for anti-LPL was goat anti-mouse-AlexaFluor546. Confocal and differential interference contrast images were acquired using the Zeiss LSM 510 microscope (Zeiss) fitted with a 1.3-narrow aperture (NA) x40 Fluar objective. For quantitation, images of each cell in at least 2 randomly selected fields of each sample were acquired. Cells that appeared dead or were in contact with other cells were excluded from analysis. Images were randomized and polarization of each cell was determined by an independent, blinded observer.

Statistics

For normally distributed data, either paired or unpaired Student’s t-test was used to determine statistical significance, with p < 0.05 considered significant. If data were not normally distributed, then the Mann-Whitney or Wilcoxon ranked sum test was used. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 4 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Results

Mature thymocytes accumulated in n3.L2 LPL−/− mice due to diminished thymocyte egress

LPL is upregulated as thymocytes successfully undergo positive selection along with CCR7 and other molecules associated with motility, such as gelsolin (23). Neutrophil migration was not affected in LPL−/− mice (26), but no role for LPL in T cell motility and development has yet been explored. To determine how LPL might be required for thymocyte maturation and subsequent lymphocyte motility, LPL−/− mice transgenic for the n3.L2 TCR were generated. Use of a transgenic TCR model enabled a more detailed analysis of the maturation of thymocytes with a defined TCR specificity. The n3.L2 TCR recognizes Hb(64–76)/I-Ek, and thymocyte development in n3.L2 mice has been well characterized (28, 31).

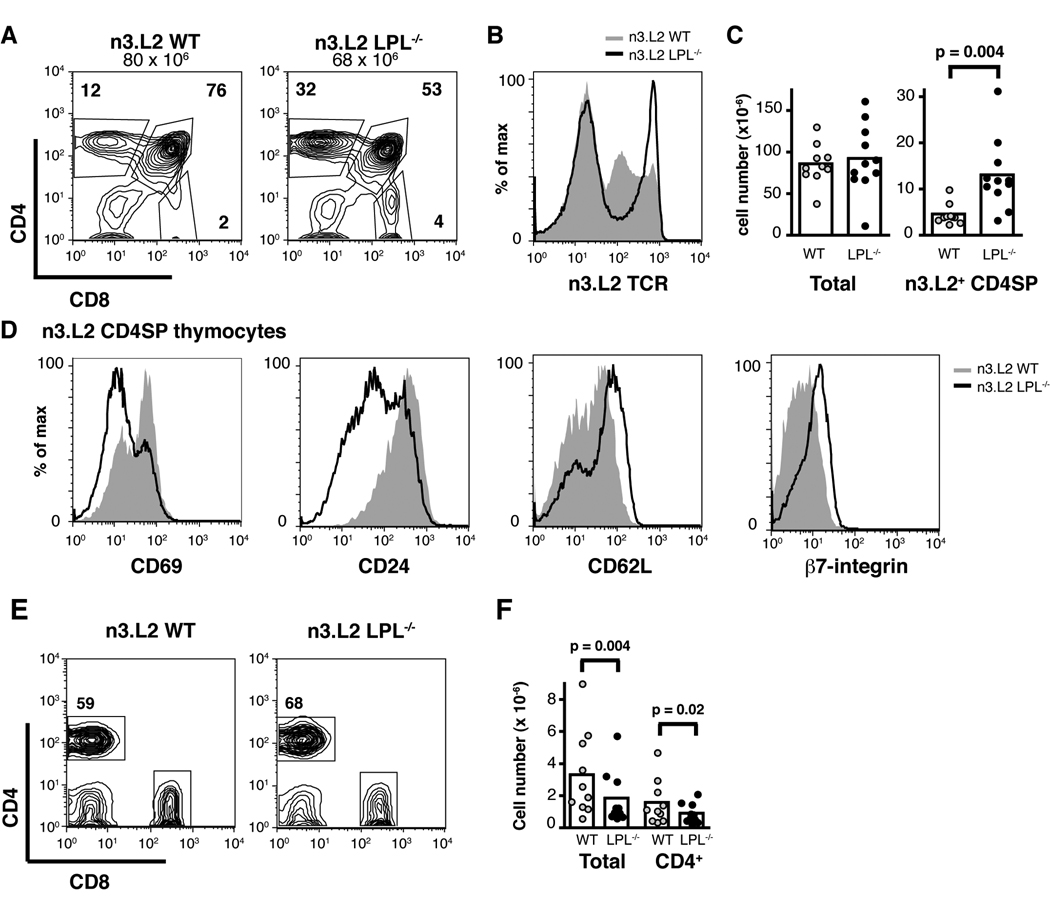

The number and percentage of CD4SP, TCR-high thymocytes was dramatically increased in n3.L2 LPL−/− mice, compared to n3.L2 WT mice, though the total number of thymocytes was not affected (Fig. 1A, 1B, 1C). The accumulated n3.L2 CD4SP LPL−/− thymocytes were more phenotypically mature than n3.L2 CD4SP WT thymocytes, as they were CD69neg, CD24low, CD62Lhigh and β7-integrinhigh (Fig. 1D). The accumulation of phenotypically mature, TCR-high, CD4SP thymocytes in n3.L2 LPL−/− mice suggested a defect in thymocyte egress, as the same phenotype has been observed in other systems in which thymic egress is diminished (7, 8, 33, 35). The finding of smaller lymph nodes and fewer mature CD4+ T cells in n3.L2 LPL−/− mice was consistent with diminished, though not completely inhibited, thymocyte egress (Fig. 1E, 1F).

Figure 1.

Mature n3.L2 CD4SP thymocytes accumulate in n3.L2 LPL−/− mice. (A, B) Flow cytometry of (A) CD4 and CD8 and (B) n3.L2 TCR expression on thymocytes from n3.L2 WT (grey histogram) and n3.L2 LPL−/− (solid line) mice. (C) Number of total and n3.L2+ CD4SP thymocytes from n3.L2 WT (grey, n=10) and n3.L2 LPL−/− (filled, n=11) mice analyzed in 10 independent experiments. Each symbol represents the value for an individual mouse, mean indicated by bar, p value determined with Wilcoxon signed rank test. (D) Expression of the maturation markers CD69, CD24, CD62L and β7-integrin on n3.L2 CD4SP thymocytes from n3.L2 WT (grey histogram) and n3.L2 LPL−/− (solid line) mice. (E) CD4 and CD8 expression of lymphocytes from peripheral lymph nodes of n3.L2 WT and n3.L2 LPL−/− mice. (F) Number of total and CD4+ cells isolated from 4 lymph nodes of n3.L2 WT (grey, n=10) and n3.L2 LPL−/− (filled, n=10) mice, analyzed in 10 independent experiments. Each symbol represents the value for an individual mouse, mean indicated by bar, p values determined using Wilcoxon signed rank test. (A, B, D, E) Flow cytometry representative of at least 7 pairs of mice analyzed in 7 independent experiments.

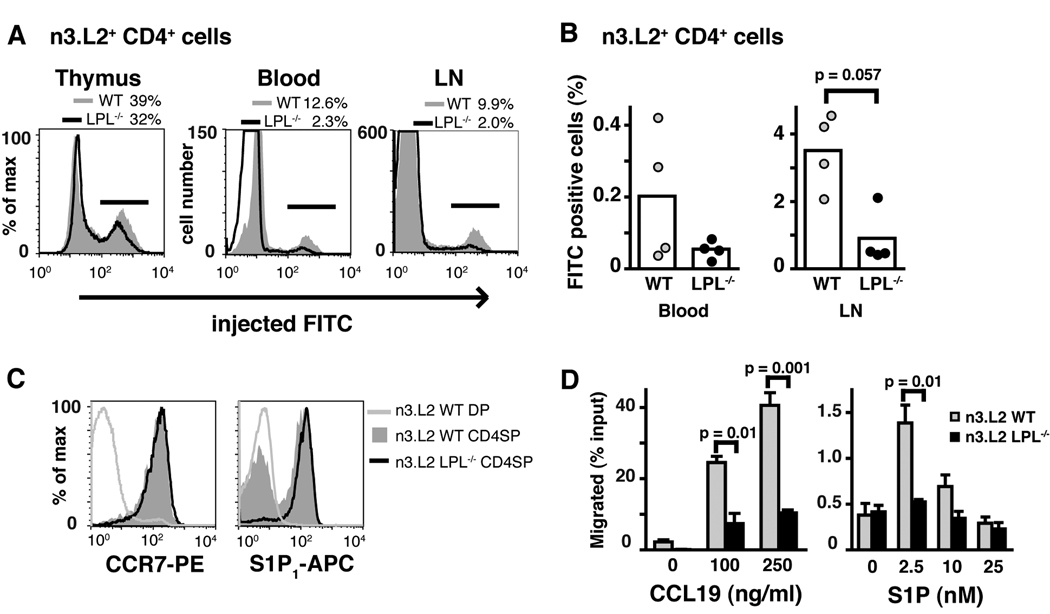

Intrathymic injection of FITC confirmed that LPL deficiency resulted in diminished thymic egress. The percentage and number of FITC-labeled n3.L2 CD4+ T cells recovered from peripheral blood, lymph nodes, and spleens of intrathymically injected n3.L2 LPL−/− mice were reduced (Fig. 2A, 2B and data not shown). Reduction of the number of FITC-labeled cells from peripheral blood suggests that the accumulation of n3.L2 CD4SP thymocytes and relative paucity of CD4+ T cells in n3.L2 LPL−/− mice was due to decreased thymocyte egress, and not to reduced entry into peripheral lymphoid organs. B cells recovered from the spleens of mice injected intrathymically with FITC were not labeled with FITC (data not shown), indicating that FITC-positive T cells from the peripheral lymphoid organs were recent thymic emigrants and not non-specifically labeled during injection. Thus, intrathymic FITC injection confirmed diminished thymocyte egress in n3.L2 LPL−/− mice.

Figure 2.

Diminished thymic egress and diminished in vitro motility of n3.L2 CD4SP LPL−/− thymocytes. (A) Labeling of n3.L2+ CD4SP thymocytes and mature T cells recovered from n3.L2 WT and n3.L2 LPL−/− mice 48 hrs after intrathymic injection of FITC (representative of 4 independent experiments). (B) Normalized percentage of FITC+ n3.L2+ CD4+ T cells recovered from the blood and lymph nodes of mice injected with FITC intrathymically. Each symbol represents the value from one mouse, mean represented by bar, p value determined using Mann-Whitney test, data from 4 independent experiments each with a pair of age-matched mice. (C) Equivalent expression of S1P1 and CCR7 on n3.L2+ CD4SP thymocytes from n3.L2 WT and n3.L2 LPL−/− mice. Expression of S1P1 and CCR7 on DP thymocytes from n3.L2 WT mice included as negative control. Representative of at least 2 independent experiments. (D) Transwell migration of mature (CD62Lhigh) CD4SP thymocytes from n3.L2 WT (grey bars) and n3.L2 LPL−/− (filled bars) mice towards the chemoattractants CCL19 and S1P. Data shown are mean ± S.E.M. of duplicate or triplicate samples within a single experiment; representative of at least 3 independent experiments, p value determined by unpaired t-test.

Diminished in vitro motility of n3.L2 LPL−/− thymocytes

CCR7 and the chemokine ligand CCL19 regulate thymic egress in newborn mice (4), and S1P1 and its ligand S1P are absolutely required for thymocyte egress (7, 8). Thymocytes from n3.L2 LPL−/− mice expressed normal levels of the receptors S1P 1 and CCR7 (Fig. 2C). We hypothesized that the failure of thymic egress in n3.L2 LPL−/− mice was due to a failure to migrate towards S1P and CCL19, and therefore assessed in vitro motility of mature CD4SP thymocytes using transwell chemotaxis assays. Mature (CD62Lhigh) CD4SP thymocytes from n3.L2 WT mice migrated towards CCL19 and S1P as expected, based on previously published reports (8, 36). In contrast, mature CD4SP thymocytes from n3.L2 LPL−/−mice demonstrated a severe defect in migration towards both chemoattractants (Fig. 2D). Defective migration towards chemoattractants explains the observed defect in thymic egress.

Diminished motility of mature OT-1 LPL−/− T cells

CCR7 and its ligands have been demonstrated to regulate the motility of mature T cells in lymph nodes, as both the velocity and motility coefficient of T cells was reduced in the absence of the receptor CCR7 or its ligands CCL19 and CCL21(5, 6). If LPL is required for naive T cell motility in response to CCR7 ligands, then LPL−/− lymphocytes should demonstrate intranodal motility defects similar to those found in CCR7−/− lymphocytes. To test this hypothesis we generated OT-1 LPL−/− mice. The OT-1 receptor is restricted to the H-2b background, which enabled the use of the CD11c-YFP H-2b mouse and allowed simultaneous visualization of lymphocytes and dendritic cells.

We first determined that the OT-1 LPL−/− mouse exhibited a similar phenotype to the n3.L2 LPL−/− mouse. There was a relative increase in mature (CD62Lhigh) TCR-high, CD8SP cells in the OT-1 LPL−/− thymus (Fig. 3A, 3B, 3C). TCRhigh CD8SP thymocytes from OT-1 LPL−/− mice were phenotypically more mature (CD69neg, CD24low) than those isolated from the OT-1 WT mouse (Fig. 3D). Fewer mature CD8+ T cells were isolated from the periphery of OT-1 LPL−/− mice (Fig. 3E). Intrathymic FITC injection demonstrated diminished thymic egress in OT-1 LPL−/− mice (Fig. 3F). CD8SP thymocytes from OT-1 LPL−/− mice exhibited defective in vitro motility towards CCL19 and S1P, despite comparable levels of expression of the receptors CCR7 and S1P1. (Fig. 3G and data not shown). LPL is thus required for motility of both CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes.

Figure 3.

OT-1 LPL−/− mice exhibit similar phenotypic defects as n3.L2 LPL−/− mice and OT-1 LPL−/− lymphocytes exhibit diminished intranodal motility. (A, B) Expression of (A) CD4 and CD8 and (B) Va2 on thymocytes from OT-1 WT (grey) and OT-1 LPL−/− mice (solid line). (C) Number of total, CD62Llow Vα2high CD8SP and CD62Lhigh Vα2high CD8SP thymocytes from OT-1 WT (grey, n=11 or 10) and OT-1 LPL−/− (filled, n =12 or 11) mice. Each symbol represents value from an individual mouse, p value from unpaired t-test. (D) Expression of CD69 and CD24 on Vα2high CD8SP thymocytes from OT-1 WT (grey) and OT-1 LPL−/− (solid line) mice. (A, B, C, D) Data from at least 6 independent experiments. (E) Numbers of total and CD8+ T cells from lymph nodes of OT-1 WT (grey, n = 8) and OT-1 LPL−/− (filled, n = 8) mice analyzed in 4 independent experiments, p value determined using Mann-Whitney. (F) Normalized percentage of FITC-labeled Vα2 CD8+ cells recovered from peripheral blood and lymph nodes of OT-1 WT and OT-1 LPL−/− mice 48 hrs after intrathymic FITC injection. Each symbol represents value from individual mouse; data from 4 independent experiments, p value determined using Mann-Whitney test. (G) Vα2 CD8SP thymocytes from OT-1 LPL−/− mice did not migrate efficiently in transwell assays towards CCL19 or S1P. Data shown are mean ± S.E.M. of duplicate or triplicate samples with p values determined by unpaired t-test; representative of 2 independent experiments. (H) Two-photon time-lapse image sequences of CD8+ OT-1 WT (blue) and CD8+ OT-1 LPL−/− (red) cells in naive lymph nodes 2 h after injection into CD11c-YFP mice. Dendritic cells appear green. Representative cell tracks are shown (white lines). Time stamp in lower right-hand corners. Scale bar represents 20 µm. Corresponds with supplemental video. (I) Velocity (mean OT-1 WT, 7.8 µm/min; mean OT-1 LPL−/−, 5.3 µm/min), motility (mean OT-1 WT, 104 µm2/min; mean OT-1 LPL−/−, 61 µm2/min) and meandering index of CD8+ cells from OT-1 WT (grey circles, n= 56) and OT-1 LPL−/− (filled circles, n=55) mice. Each point represents a single cell tracked for a minimum of 8 frames. Mean of each population is indicated, with p values determined by Mann-Whitney test. Data pooled from two independent experiments.

Intranodal motility of OT-1 LPL−/− T cells and OT-1 WT T cells was then compared using two-photon microscopy (Fig. 3H, 3I and Supplemental Movie). As predicted, CD8+ T cells isolated from OT-1 LPL−/− mice demonstrated reduced velocity and motility. The degree to which the velocity and motility of LPL−/− lymphocytes was reduced was comparable to published findings with CCR7−/− lymphocytes (6). CCR7−/− lymphocytes demonstrated a minor but statistically significant reduction in the meandering index, which measures the degree to which a cell’s movement varies from a straight line. We observed a very slight decrease in the meandering index of LPL−/− lymphocytes, though the difference was not significant. LPL was thus required for normal mature CD8+ T cell motility in lymph nodes, and the reduction in LPL−/− lymphocyte motility was consistent with loss of CCR7-mediated motility.

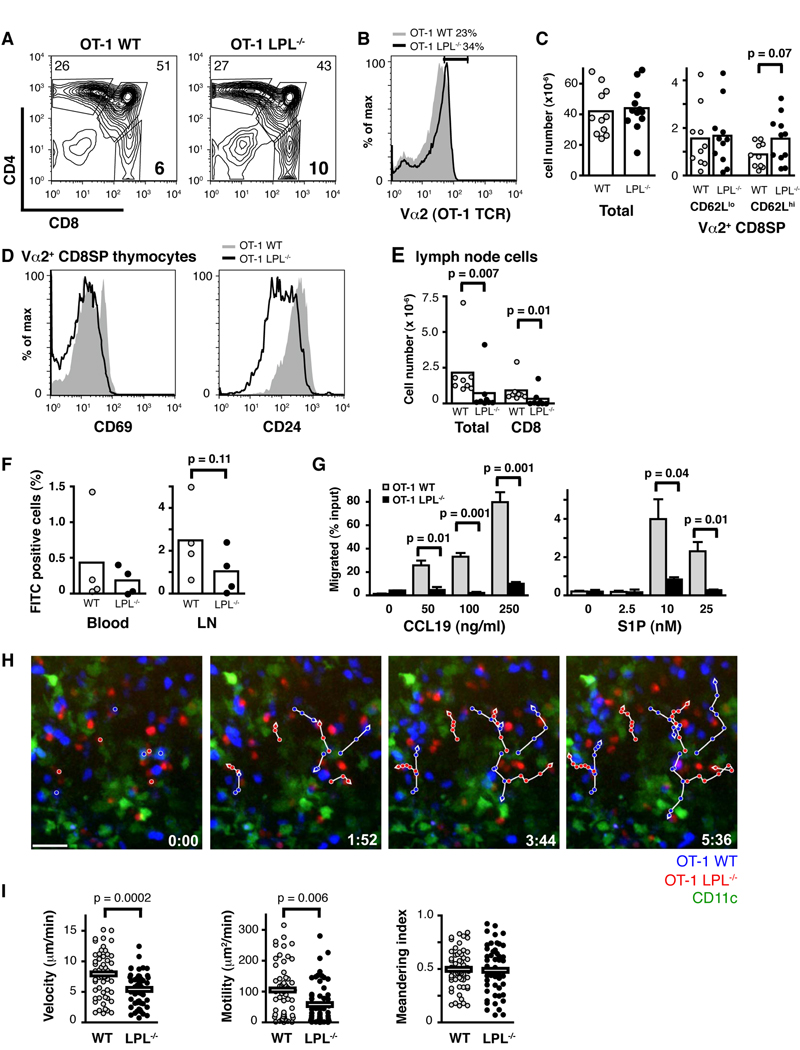

Non-transgenic T cells are defective in CCR7-mediated motility

The motility of non-transgenic lymphocytes was also examined (Fig. 4). Both CD4+ and CD8+ mature T cells from non-transgenic LPL−/− mice demonstrated diminished motility towards CCL19 in chemotaxis transwell assays (Fig. 4A), indicating that defective motility in LPL−/− cells was not due to the transgenic system. However, the in vivo phenotype of non-transgenic LPL−/− mice differed slightly from that of the transgenic mice, in that the total number of thymocytes recovered from LPL−/− mice was reduced (Fig. 4B) and the percentage of CD4SP and CD8SP thymocytes was not increased (Fig. 4C). Similar to LPL−/− mice expressing transgenic TCRs, the SP thymocytes recovered from non-transgenic LPL−/− mice were CD69neg, CD24low, CD62Lhigh, and thus phenotypically more mature (Fig. 4D). This phenotype was observed with temporary inhibition of S1P1. Treatment with the S1P1-selective agonist SEW2871 increased the proportion of SP thymocytes exhibiting a mature phenotype without changing the total percentage of SP thymocytes (10). Furthermore, there was a paucity of mature T cells isolated from the lymph nodes of non-transgenic LPL−/− mice (Fig. 4E). Although the in vivo phenotype differed in some respects in the non-transgenic LPL−/− mouse, the core findings of the increase of phenotypically mature thymocytes, smaller lymph nodes, and defective in vitro CCR7-mediated motility remained constant across n3.L2, OT-1, and non-transgenic LPL−/− mice.

Figure 4.

Nontransgenic LPL−/− cells demonstrate in vitro motility defects, though the in vivo phenotype of nontransgenic LPL−/− mice varies from that of transgenic LPL−/− mice. (A) Peripheral T cells isolated from LN of non-transgenic LPL−/− mice do not migrate efficiently in transwell assays towards CCL19 (100 ng/ml). Data shown are the mean ± S.E.M of triplicate samples in an individual experiment; representative of 3 independent experiments, p values determined by unpaired t-test. (B) Number of total, CD4SP, and CD8SP thymocytes recovered from non-transgenic WT (grey circles, n = 6) and LPL−/− (filled circles, n = 6) mice. Each symbol represents the value from one mouse, data from 6 independent analyses, mean represented by bar. (C) Expression of CD4 and CD8 on thymocytes from non-transgenic WT and LPL−/− mice. (D) Expression of the maturation markers CD69, CD24 and CD62L on CD4SP and CD8SP thymocytes from non-transgenic LPL−/− (solid line) and WT (grey histogram) mice. (E) Number of total, CD4+ and CD8+ cells recovered from 4 lymph nodes of non-transgenic WT (grey circles, n = 7) and LPL−/− (filled circles, n = 7) mice. Each symbol represents the value from one mouse, mean represented by bar, data from 7 independent analyses. Flow cytometry in (C and D) represents at least 4 pairs of mice.

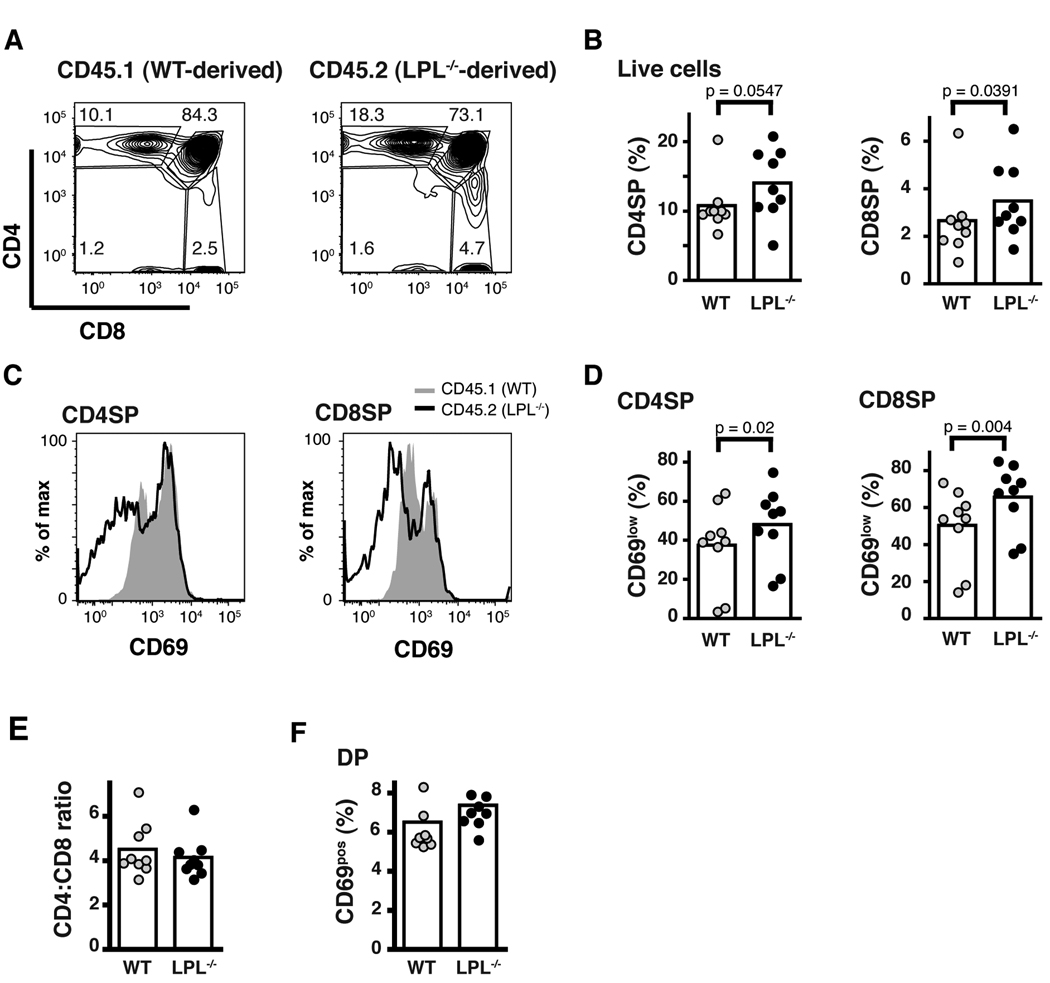

The participation of CCR7 in positive selection and subsequent maturation of thymocytes has been described (1, 2). Overexpression of CCR7 in thymocytes increased the commitment of positively–selected thymocytes to the CD8SP lineage. Increased motility generated by increased CCR7 expression was hypothesized to contribute to the increase in commitment to the CD8SP lineage (2). To reveal stages of thymocyte development and maturation that might be affected by diminished motility towards CCR7, we generated mixed bone marrow chimeric mice (Fig. 5). From these prior studies, we predicted that diminished CCR7-mediated motility would result in decreased commitment to the CD8SP lineage of LPL−/− thymocytes, and thus an increase in the CD4:CD8 ratio in non-transgenic LPL−/− thymocytes. Also we wished to assess whether direct competition between WT and LPL−/− thymocytes would reveal a requirement for CCR7-mediated motility during positive selection.

Figure 5.

LPL−/− SP thymocytes are at a competitive disadvantage during thymic egress. (A) CD4 and CD8 expression of thymocytes isolated from sub-lethally irradiated RAG1−/− mouse reconstituted with bone marrow from WT (CD45.1+) and LPL−/− (CD45.2+) mice mixed in a 1:1 ratio. (B) Percentage of thymocytes derived from either WT (CD45.1+) or LPL−/− (CD45.2+) donors that were CD4SP or CD8SP. (C) CD69 expression on CD4SP or CD8SP thymocytes derived from either WT (CD45.1+) or LPL−/− (CD45.2+) donors. (D) Percentage of CD4SP or CD8SP thymcoytes that were CD69neg derived from either WT (CD45.1+) or LPL−/− (CD45.2+) donors. (E) Ratio of CD4SP:CD8SP thymocytes derived from WT (CD45.1+) or LPL−/− (CD45.2+) donors. (F) Percentage of DP thymocytes that were CD69pos derived from either WT (CD45.1+) or LPL−/− (CD45.2+) donors. (A and C) Representative data from 1 of 9 chimeric mice shown. (C, D-F) Each symbol represents data from one chimeric mouse, mean represented by bar, data from 4 independent experiments p values determined using Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Mixed bone marrow chimeras recapitulated the thymic phenotype seen in the transgenic and non-transgenic LPL−/− mice. Thymocytes derived from LPL−/− bone marrow accumulated as phenotypically mature CD4SP and CD8SP cells (Fig. 5A, 5B, 5C, 5D). The accumulation of LPL−/− thymocytes was accentuated in the competitive environment compared to the noncompetitive environment (Fig. 5B, Fig. 4). LPL−/− SP thymocytes were phenotypically more mature than WT thymocytes, with increased percentages that were CD69neg and CD24low (Fig. 5C, 5D and data not shown). Total cell numbers for thymocytes and lymph nodes for each reconstituted mouse are provided (Table). Mature CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from both WT and LPL−/− donors could be found in the periphery, consistent with the observation that thymic egress is not completely dependent upon LPL (Table). Increased accumulation of SP thymocytes from LPL−/− donors in WT recipients also demonstrated that defective thymic egress in LPL−/− mice is cell-intrinsic.

Table.

Mature T cells derived from both WT and LPL−/− bone marrow could be found in mixed bone marrow chimeras following reconstitution.a

| Thymus | Lymph nodes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT-derived | LPL−/−-derived | WT-derived | LPL−/−-derived | |||||

| CD4SP |

CD8SP |

CD4SP |

CD8SP |

CD4SP |

CD8SP |

CD4SP |

CD8SP |

|

| Mouse 1 | 3.57 | 0.87 | 2.86 | 0.64 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.57 | 0.34 |

| Mouse 2 | 1.94 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.20 | 0.62 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.29 |

| Mouse 3 | 8.57 | 2.11 | 5.04 | 1.31 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| Mouse 4 | 2.48 | 0.48 | 1.42 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| Mouse 5 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.97 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.07 |

| Mouse 6 | 3.18 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.09 | 0.64 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.03 |

| Mouse 7 | 1.88 | 0.34 | 9.38 | 2.30 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.90 | 0.27 |

| Mouse 8 | 5.93 | 1.50 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 1.13 | 0.27 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Mouse 9 | 4.87 | 1.52 | 1.09 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

Given are the number of cells (x 10−6) gated as indicated derived from the thymuses and lymph nodes of sub-lethally irradiated RAG1−/− mice reconstituted with bone marrow from WT (CD45.1+) and LPL−/− (CD45.2+) mice mixed in a 1:1 ratio.

Contrary to our prediction that LPL−/− thymocytes would shift towards the CD4SP lineage in a competitive environment due to decreased motility towards CCR7 ligands, there was no change in the CD4:CD8 ratio of thymocytes derived from LPL−/− bone marrow (Fig. 5E). Furthermore there was no decrease in the efficiency of positive selection of LPL−/− thymocytes in a competitive environment, as assessed by the percentage of DP thymocytes positive for CD69 (Fig. 5F). While LPL−/− thymocytes exhibited clear defective motility towards CCR7 ligands, not all processes during thymic development in which CCR7 has been demonstrated to play a role were affected by LPL deficiency. These results suggest that LPL is required for some, but not all, functions of CCR7.

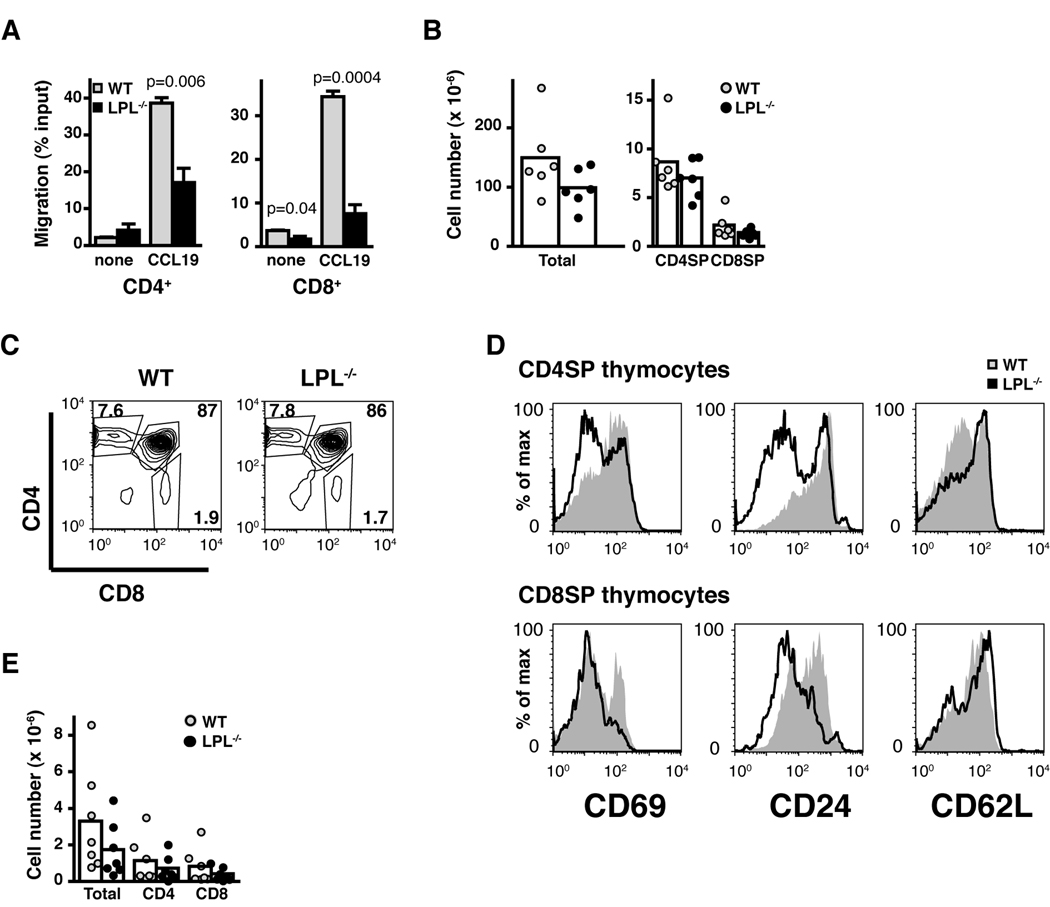

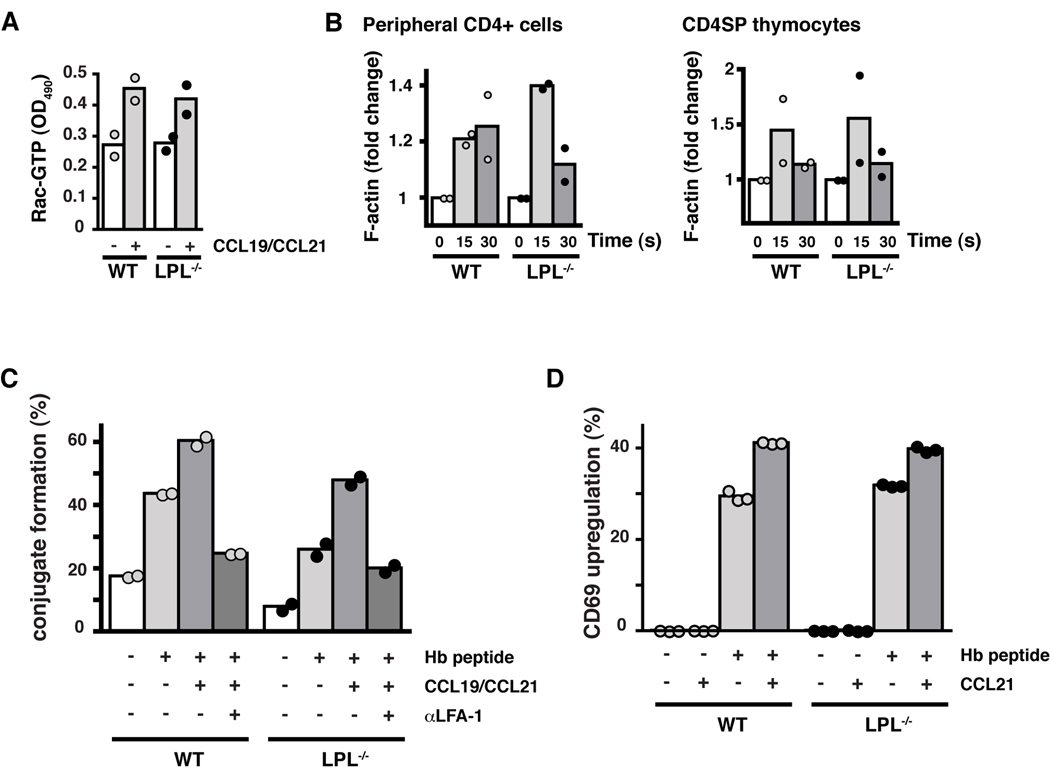

Proximal CCR7 signaling to Rac activation is intact in LPL−/− T cells

Ligation of G-protein coupled receptors by chemoattractants results in a rapid burst of actin polymerization. This initial burst of polymerization is dependent upon signaling through the small GTPase Rac. Cells unable to activate Rac in response to chemoattractant ligation demonstrate deficient initiation of F-actin polymerization and defective motility (33, 37, 38). Rapid activation of Rac following CCR7 stimulation with CCL19 was not inhibited in LPL−/− T cells (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, the rapid burst of F-actin polymerization following CCL19 ligation was observed in LPL−/− CD4+ T cells and CD4SP thymocytes (Fig. 6B). LPL deficiency did not disrupt signaling immediately proximal to CCR7 ligation, nor did it prevent the initiation of F-actin polymerization.

Figure 6.

Early CCR7 signaling and CCR7-mediated TCR costimulation are not dependent upon LPL. (A) Levels of GTP-Rac in CD4+ T cells from WT (grey circles) and LPL−/− (filled circles) mice incubated with or without CCR7 ligands for 15 s. Duplicate samples indicated with symbols and mean indicated by bars; representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) F-actin content of CD4+ cells isolated from peripheral LN of WT (grey circles) and LPL−/− (filled circles) mice stimulated with CCL19 (100 ng/ml) and of CD4SP thymocytes sorted by FACS from WT (grey circles) and LPL−/− (filled circles) mice stimulated with CCL19 and CCL21 (100 ng/ml each). Data normalized to unstimulated cells. Each symbol represents result from 1 of 2 independent experiments with mean indicated by bars. (C) Conjugate formation of CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells and DDAO-labeled CH27 cells incubated ± cognate peptide and ± CCL19 + CCL21. Data shown as percentage of T cells that formed conjugates. (D) Percent of cells positive for CD69 following overnight stimulation with APCs ± cognate peptide and ± CCL21. (C, D) Symbols represent replicate samples within one experiment and bars represent means. Representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

Co-stimulation of TCR signaling is intact in LPL−/− T cells

Ligation of CCR7 has been demonstrated to co-stimulate TCR signaling (13, 39). CCR7 co-stimulation depends upon CCR7-mediated increases in LFA-1 affinity. Increased affinity of LFA-1 increases the likelihood and/or duration of T cell-DC contacts that then enable TCR engagement and signaling (13). In both WT and LPL−/− n3.L2 T cells, CCR7 ligation enhanced the formation of peptide-specific T cell-APC conjugates (Fig. 6C) and increased the upregulation of CD69 following TCR engagement (Fig. 6D). The function of CCR7 as a co-stimulatory molecule did not depend upon LPL.

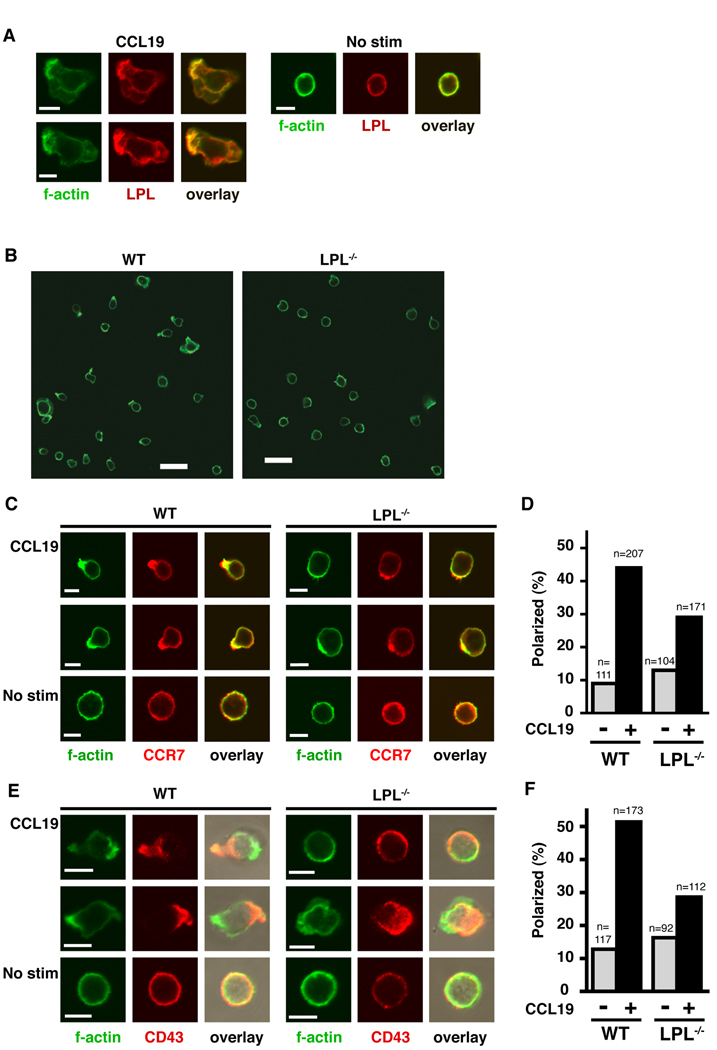

Failure of CCR7 polarization in LPL−/− T cells following CCL19 stimulation

Acquisition of a motile phenotype correlates with polarization of the T cell. Chemokine receptors, activated integrins and a concentration of F-actin can be found at the lamellipod of the polarized T cell, while markers such as CD43 and CD44 are found in the uropod (16, 40–43). Cells unable to polarize in response to chemokine stimulation exhibit motility defects (16, 43). Following chemokine stimulation, LPL colocalized with F-actin and appeared to be concentrated with F-actin in the lamellipod of CCL19-stimulated T cells (Fig. 7A). LPL was also present in the uropod and was therefore not itself polarized. However, in the absence of LPL, many fewer T cells exhibited polarized F-actin (Fig. 7B) upon CCL19 stimulation. Colocalization of polarizaed CCR7 and f-actin was determined in WT and LPL−/− cells stimulated with CCL19 (Fig. 7C). Fewer LPL−/− stimulated cells demonstrated polarized, colocalized CCR7 and F-actin (Fig. 7D). Cellular polarization was further assessed in LPL−/− T cells by staining for F-actin and the uropod marker CD43 (Fig. 7E). While some polarization of LPL−/− T cells occurred in response to CCL19 stimulation, the percentage was reduced (Fig. 7F). Without affecting Rac activation or F-actin polymerization, LPL deficiency resulted in diminished CCR7-mediated polarization of T cells. Failure to polarize in response to chemokine stimulation would explain the defective motility observed in LPL−/− T cells.

Figure 7.

LPL−/− T cells do not polarize efficiently in response to CCR7 ligation. (A) LPL (red) and F-actin (green) localization in non-transgenic WT CD4+ T cells incubated with or without CCL19 (100 ng/ml) on Fc/ICAM-1-coated coverslips for 1 hr. Representative images from 1 of 2 independent experiments. Scale bar, 5 µM. (B) F-actin staining of CD4+ cells from nontransgenic WT and LPL−/− mice plated on Fc/ICAM-1-coated coverslips for 1 hr then stimulated for 5 m with CCL19 (250 ng/ml). Representative fields from 1 of at least 4 independent experiments. Scale bar, 20 µM. (C) CCR7 (red) and F-actin (green) localization in nontransgenic CD4+ T cells from WT or LPL−/− mice incubated for 1 hr on Fc/ICAM-1-coated coverslips then stimulated for 5 m with CCL19 (250 ng/ml). Examples of stimulated cells that were counted as “polarized” are shown for both WT and LPL−/− samples. Scale bar, 5 µM. (D) Percentage of cells with colocalization and polarization of CCR7 and F-actin (n=number of cells counted for each group; every cell in multiple fields captured in 2 independent experiments). (E) F-actin (green) and CD43 (red) localization in nontransgenic CD4+ T cells from WT or LPL−/− mice incubated with or without CCL19 (100 ng/ml) for 1 hr on coverslips coated with Fc/ICAM-1. Examples of stimulated cells that were counted as “polarized” are shown for both WT and LPL−/− samples. Scale bar, 5 µM. (F) Percentage of cells with polarization of CD43 and F-actin (n=number of cells counted for each group; every cell in multiple fields captured in 2 independent experiments).

Discussion

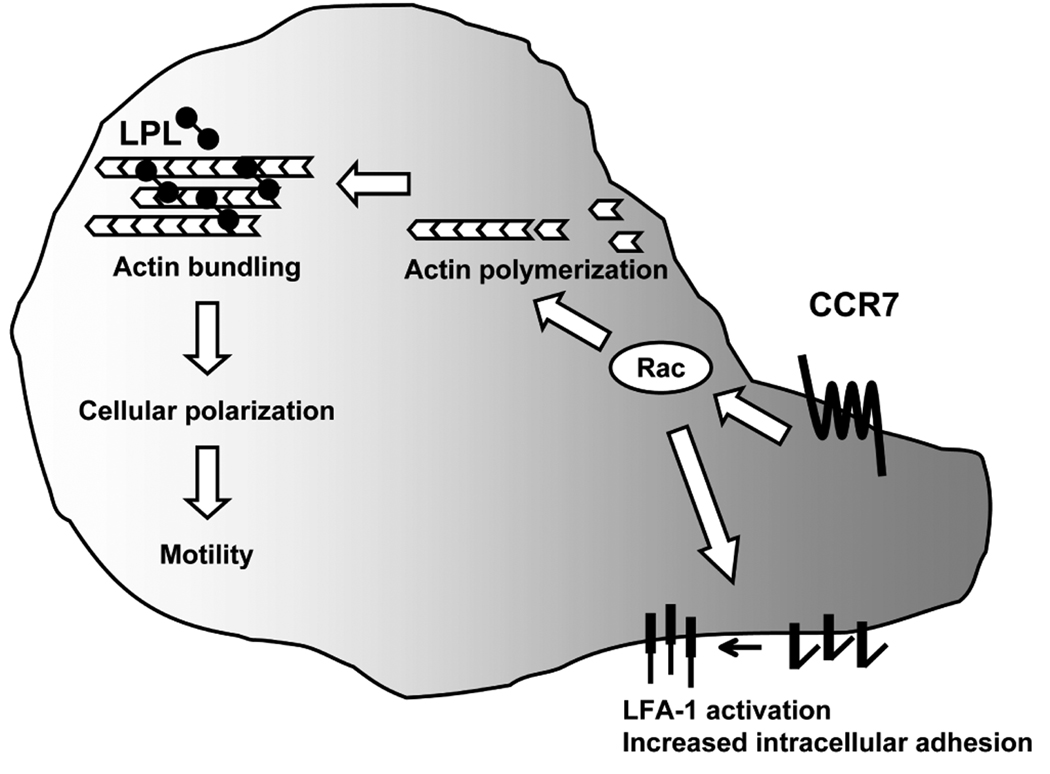

The actin-bundling protein LPL has no previously identified function beyond stabilization of higher-order structures of F-actin microfilaments. Here we demonstrate that LPL is required for CCR7-mediated polarization and T cell motility, but not early CCR7 signaling and CCR7-mediated increased intracellular adhesion (Fig. 8). The function of LPL as an actin-bundling protein distinguishes LPL from other actin-binding proteins required for lymphocyte motility that primarily regulate early chemokine receptor signaling (17). For instance, knockdown of cortactin resulted in diminished ERK signaling and diminished motility upon CXCR4 ligation (44). Mice deficient for the formin mDia1, which promotes F-actin polymerization, exhibited defective thymic egress and impaired lymphocyte trafficking (20). A mutation in coronin1A, a protein that regulates the Arp2/3 complex and thus actin polymerization, has recently been described as the molecular defect underlying the phenotype of delayed thymic egress in the cataract Shionogi (CTS) mouse strain (19, 22). LPL differed from these actin-binding proteins as LPL was not required for proximal CCR7 signaling to the initiation of F-actin polymerization. Instead, LPL deficiency resulted in a failure to either generate or maintain T cell polarization. Phalloidin staining of total cellular F-actin has been sufficiently sensitive to detect the defects in actin polymerization associated with impaired chemokine receptor proximal signaling (33). However, subtle defects in actin dynamics in LPL−/− cells have not been excluded. It is possible that actin-bundling is required for local maintenance or regulation of actin polymerization that is not apparent at the whole-cell level. The disruption of higher-order microfilament structures in the presence of intact Rac activation and initiation of F-actin polymerization in LPL−/− lymphocytes illustrates a previously unrecognized level of regulation of actin dynamics.

Figure 8.

LPL is required for CCR7-mediated motility but is dispensable for early CCR7 signaling to Rac activation and increased intracellular adhesion. After ligation of CCR7, activation of Rac and the initial burst of F-actin polymerization occur in LPL−/− cells. The co-stimulatory function of CCR7 is also intact in LPL−/− cells. The dependence of CCR7 costimulation upon Rac activation has been previously demonstrated (14). However, CCR7-induced cellular polarization and chemotaxis is impaired in LPL−/− cells. Impairment of chemotaxis resulted in the delayed thymic egress and reduced intranodal lymphocyte motility observed in LPL−/− mice.

Defective motility of LPL−/− lymphocytes manifested in vivo as diminished thymic egress and reduced intranodal velocity and motility. Thymic egress is regulated by at least two chemoattractant receptors, S1P1 and CCR7. Consistent with a defect in thymocyte egress, non-transgenic, n3.L2 and OT-1 LPL−/− mice all demonstrated a shift of single positive thymocytes to a more mature phenotype (CD69low, CD24low, CD62Lhigh), (7, 10). The most dramatic phenotype was noted in n3.L2 LPL−/− mice, with a tripling of the number of n3.L2+ CD4SP thymocytes recovered from n3.L2 LPL−/− mice. There was no increase in percentage or number of CD4SP or CD8SP thymocytes in non-transgenic LPL−/− mice. Selective agonism of S1P1 with SEW2871 also resulted in a shift of SP thymocytes to a more mature phenotype without an overall increase in the percentage or number of SP thymocytes (10). Mixed bone marrow chimeras revealed a competitive disadvantage during egress for mature SP thymocytes derived from non-transgenic LPL−/− donors, as the percentage of LPL−/−-derived mature SP thymocytes was increased compared to WT-derived mature SP thymocytes. Defective thymocyte egress was confirmed by intrathymic FITC injection in both n3.L2 and OT-1 LPL−/− mice. Use of two distinct and well-characterized transgenic models makes it unlikely that the observed defect in thymocyte egress in LPL−/− mice is unique to a single transgenic system or restricted to the CD4 or CD8 lineage. Cells deficient for LPL from both transgenic and non-transgenic mice failed to migrate normally in transwell assays to the chemoattractants CCL19 and S1P, so it is unlikely that expression of transgenic TCRs altered cell-intrinsic actin dynamics. More likely, altered actin dynamics manifested differently during thymic maturation in the presence of transgenic TCRs.

Two-photon microscopy of LPL−/− mature T lymphocytes revealed motility defects that phenocopied the defects in velocity and motility of CCR7−/− T lymphocytes in lymph nodes. Velocity and motility of LPL−/− T cells were reduced to a similar degree as CCR7−/− T cells (6). We did not find as great a decrease in meandering index in LPL−/− T cells as was seen in CCR7−/− T cells. This difference in results may be dependent on different experimental conditions, or possibly that LPL is required for the cytoskeletal apparatus that functions in speed or forward motion mediated by CCR7, but is not required for the apparatus required for changes in direction. In support of this latter possibility is the observation that proximal CCR7 signaling was not impaired in LPL−/− T cells. LPL was also dispensable for CCR7-mediated promotion of cell-cell interactions and costimulation of TCR signaling. LPL was required, however, for efficient polarization of T cells downstream of CCR7 ligation. Thus, LPL is essential for normal in vivo motility of T cells and for CCR7-induced cellular polarization required for directed motility.

In addition to regulating thymocyte egress in some systems and intranodal motility of mature T cells, CCR7 and its ligands CCL19 and CCL21 have been implicated in other processes critical to thymocyte development, such as positive selection, corticomedullary migration of positively-selected thymocytes, lineage commitment, and negative selection (1, 2, 45–48). CCR7 is upregulated during positive selection and appears to promote thymic-DC contacts during this process (1). Overexpression of CCR7 promoted commitment to the CD8SP lineage and increased motility due to CCR7 overexpression was hypothesized to drive this lineage choice (2). We used the ability of LPL to dissociate CCR7-mediated cell-cell interactions from CCR7-induced motility (Fig. 8) to probe which downstream functions of CCR7 were critical to positive selection and lineage commitment. In competitive bone marrow chimeric mice, we found no inhibition of positive selection or alteration of lineage commitment of LPL−/− thymocytes. These results indicate that cell-cell interactions promoted by CCR7 ligation contribute to the processes of positive selection and lineage commitment. Intact positive selection in LPL−/− thymocytes confirms results in which CCR7 overexpression increased thymic-DC interaction during positive selection but did not increase the motility of positively-selected thymocytes (1).

While many of the molecules required for chemokine signaling and T cell polarization have been identified, the mechanisms by which proximal signaling is linked to cytoskeletal rearrangements and later stages of T cell polarization remain unclear (17, 21). Initial signaling pathways dependent upon small GTPases such as Rap1, Rac and cdc42 have been described. Rac activation results in the formation of lamellipodia. Polarization occurs after the stabilization of one of the lamellipodia and establishment of an anterior-posterior axis (17). The localization of LPL to the lamellipod suggests that a possible function for LPL is the stabilization of the lamellipod that then allows the generation of polarity. In the absence of LPL, lamellipodia cannot be adequately stabilized and polarity cannot be established or maintained. Alternatively, LPL may be required to stabilize the actomyosin cytoskeleton that supports retrograde flow towards the uropod (49). Further work will be required to investigate these possibilities. Interestingly, some polarization occurs in the absence of LPL. This partial reduction of polarization is reflected in the phenotype of LPL−/− mice, as thymic egress is reduced, as is seen in mice treated with FTY720 or SEW2871, but not completely ablated, as is seen in either KLF2−/− or S1P1−/− mice (7, 8, 10, 35). Either other actin-binding proteins can partially compensate for the loss of LPL, or polarization is less stable in LPL−/− cells.

Whether LPL has a general role in T cell polarization and is therefore required for other functions dependent upon polarization, such as cytokine secretion and delivery of cytotoxic granules, is also under study. In mature human T cells, phosphorylation of LPL enabled the upregulation of activation markers following TCR stimulation (50). We did not see a requirement for LPL in the upregulation of CD69 following TCR ligation, as might have been predicted (50). The difference in observed results is likely due to different experimental systems, as the previous work was performed by overexpression of a non-phosphorylatable LPL mutant in human PBLs and we are examining murine cells genetically deficient for LPL.

While T lymphocytes deficient for LPL demonstrated both in vivo and in vitro motility defects, neutrophils deficient for LPL did not (26). In fact, LPL was not required for adhesion, spreading, or in vivo or in vitro migration of neutrophils. LPL is thus similar to several other proteins involved in chemokine signaling or motility, such as ERK or DOCK2, that is utilized differently by neutrophils than by lymphocytes (17, 51). Nonetheless, it is intriguing to speculate that the role for LPL in cell polarization demonstrated here underlies the integrin signaling defect previously demonstrated in LPL−/− neutrophils.

In summary, LPL is required for maximal polarization of the chemokine receptor CCR7 in T lymphocytes in response to stimulation with ligand CCL19. In the absence of CCR7 polarization, T cells fail to fully polarize and fail to migrate towards chemokine. Failure to respond to the chemoattractants CCL19 and S1P in vitro correlated with in vivo motility defects; LPL−/− T cells demonstrated reduced intranodal motility and thymic emigration of mature LPL−/− thymocytes was diminished. The requirement for the actin-bundling protein LPL in normal T cell motility reveals a mechanism beyond actin polymerization for regulating actin dynamics at the level of higher-order actin structures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Wojciech Swat, David Haslam, Robyn S. Klein and Robert Heuckeroth for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Jen Racz for technical assistance with flow cytometric analysis and Darren Kreamalmeyer for technical assistance with maintenance of the mouse colony.

Abbreviations

- LPL

L-plastin

- SP

single positive

- DP

double positive

- Cab

clonotypic antibody

- S1P

sphingosine-1-phosphate

- B6.K

B6.AKR-H-2k

- APC

allophycocyanin

Footnotes

This work was supported by the NIH grant AI-24157 (PMA), Genentech (CW and EJB), the NIH grant K08AI081751-01 (SCM), and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society-St. Jude’s Award for Basic Research (SCM). SCM is a Scholar of the Child Health Research Center of Excellence in Developmental Biology at Washington University School of Medicine (K12-HD01487).

Publisher's Disclaimer: "This is an author-produced version of a manuscript accepted for publication in The Journal of Immunology (The JI). The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. (AAI), publisher of The JI, holds the copyright to this manuscript. This version of the manuscript has not yet been copyedited or subjected to editorial proofreading by The JI; hence, it may differ from the final version published in The JI (online and in print). AAI (The JI) is not liable for errors or omissions in this author-produced version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by the U.S. National Institutes of Health or any other third party. The final, citable version of record can be found at http://www.jimmunol.org."

References

- 1.Ladi E, Schwickert TA, Chtanova T, Chen Y, Herzmark P, Yin X, Aaron H, Chan SW, Lipp M, Roysam B, Robey EA. Thymocyte-dendritic cell interactions near sources of CCR7 ligands in the thymic cortex. J. Immunol. 2008;181:7014–7023. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yin X, Ladi E, Chan SW, Li O, Killeen N, Kappes DJ, Robey EA. CCR7 expression in developing thymocytes is linked to the CD4 versus CD8 lineage decision. J. Immunol. 2007;179:7358–7364. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davalos-Misslitz AC, Worbs T, Willenzon S, Bernhardt G, Forster R. Impaired responsiveness to T-cell receptor stimulation and defective negative selection of thymocytes in CCR7-deficient mice. Blood. 2007;110:4351–4359. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-070284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ueno T, Hara K, Willis MS, Malin MA, Hopken UE, Gray DH, Matsushima K, Lipp M, Springer TA, Boyd RL, Yoshie O, Takahama Y. Role for CCR7 ligands in the emigration of newly generated T lymphocytes from the neonatal thymus. Immunity. 2002;16:205–218. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asperti-Boursin F, Real E, Bismuth G, Trautmann A, Donnadieu E. CCR7 ligands control basal T cell motility within lymph node slices in a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-independent manner. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1167–1179. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Worbs T, Mempel TR, Bolter J, von Andrian UH, Forster R. CCR7 ligands stimulate the intranodal motility of T lymphocytes in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:489–495. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yagi H, Kamba R, Chiba K, Soga H, Yaguchi K, Nakamura M, Itoh T. Immunosuppressant FTY720 inhibits thymocyte emigration. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000;30:1435–1444. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(200005)30:5<1435::AID-IMMU1435>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cinamon G, Lesneski MJ, Xu Y, Brinkmann V, Allende ML, Proia RL, Cyster JG. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 2004;427:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei SH, Rosen H, Matheu MP, Sanna MG, Wang SK, Jo E, Wong CH, Parker I, Cahalan MD. Sphingosine 1-phosphate type 1 receptor agonism inhibits transendothelial migration of medullary T cells to lymphatic sinuses. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:1228–1235. doi: 10.1038/ni1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alfonso C, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Rosen H. CD69 down-modulation and inhibition of thymic egress by short- and long-term selective chemical agonism of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006;36:149–159. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okada T, Cyster JG. CC chemokine receptor 7 contributes to Gi-dependent T cell motility in the lymph node. J. Immunol. 2007;178:2973–2978. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woolf E, Grigorova I, Sagiv A, Grabovsky V, Feigelson SW, Shulman Z, Hartmann T, Sixt M, Cyster JG, Alon R. Lymph node chemokines promote sustained T lymphocyte motility without triggering stable integrin adhesiveness in the absence of shear forces. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:1076–1085. doi: 10.1038/ni1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman RS, Jacobelli J, Krummel MF. Surface-bound chemokines capture and prime T cells for synapse formation. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/ni1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gollmer K, Asperti-Boursin F, Tanaka Y, Okkenhaug K, Vanhaesebroeck B, Peterson JR, Fukui Y, Donnadieu E, Stein JV. CCL21 mediates CD4+ T-cell costimulation via a DOCK2/Rac-dependent pathway. Blood. 2009;114:580–588. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-200923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vicente-Manzanares M, Sanchez-Madrid F. Role of the cytoskeleton during leukocyte responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:110–122. doi: 10.1038/nri1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Real E, Faure S, Donnadieu E, Delon J. Cutting edge: Atypical PKCs regulate T lymphocyte polarity and scanning behavior. J. Immunol. 2007;179:5649–5652. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.5649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thelen M, Stein JV. How chemokines invite leukocytes to dance. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:953–959. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vicente-Manzanares M, Rey M, Perez-Martinez M, Yanez-Mo M, Sancho D, Cabrero JR, Barreiro O, de la Fuente H, Itoh K, Sanchez-Madrid F. The RhoA effector mDia is induced during T cell activation and regulates actin polymerization and cell migration in T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 2003;171:1023–1034. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foger N, Rangell L, Danilenko DM, Chan AC. Requirement for coronin 1 in T lymphocyte trafficking and cellular homeostasis. Science. 2006;313:839–842. doi: 10.1126/science.1130563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakata D, Taniguchi H, Yasuda S, Adachi-Morishima A, Hamazaki Y, Nakayama R, Miki T, Minato N, Narumiya S. Impaired T lymphocyte trafficking in mice deficient in an actin-nucleating protein, mDia1. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:2031–2038. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burkhardt JK, Carrizosa E, Shaffer MH. The actin cytoskeleton in T cell activation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008;26:233–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiow LR, Roadcap DW, Paris K, Watson SR, Grigorova IL, Lebet T, An J, Xu Y, Jenne CN, Foger N, Sorensen RU, Goodnow CC, Bear JE, Puck JM, Cyster JG. The actin regulator coronin 1A is mutant in a thymic egress-deficient mouse strain and in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:1307–1315. doi: 10.1038/ni.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mick VE, Starr TK, McCaughtry TM, McNeil LK, Hogquist KA. The regulated expression of a diverse set of genes during thymocyte positive selection in vivo. J. Immunol. 2004;173:5434–5444. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones SL, Brown EJ. FcgammaRII-mediated adhesion and phagocytosis induce L-plastin phosphorylation in human neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:14623–14630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arpin M, Friederich E, Algrain M, Vernel F, Louvard D. Functional differences between L- and T-plastin isoforms. J. Cell Biol. 1994;127:1995–2008. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen H, Mocsai A, Zhang H, Ding RX, Morisaki JH, White M, Rothfork JM, Heiser P, Colucci-Guyon E, Lowell CA, Gresham HD, Allen PM, Brown EJ. Role for plastin in host defense distinguishes integrin signaling from cell adhesion and spreading. Immunity. 2003;19:95–104. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delanote V, Vanloo B, Catillon M, Friederich E, Vandekerckhove J, Gettemans J. An alpaca single-domain antibody blocks filopodia formation by obstructing L-plastin-mediated F-actin bundling. FASEB J. 2009 doi: 10.1096/fj.09-134304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hailman E, Burack WR, Shaw AS, Dustin ML, Allen PM. Immature CD4(+)CD8(+) thymocytes form a multifocal immunological synapse with sustained tyrosine phosphorylation. Immunity. 2002;16:839–848. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindquist RL, Shakhar G, Dudziak D, Wardemann H, Eisenreich T, Dustin ML, Nussenzweig MC. Visualizing dendritic cell networks in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:1243–1250. doi: 10.1038/ni1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lo CG, Xu Y, Proia RL, Cyster JG. Cyclical modulation of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 surface expression during lymphocyte recirculation and relationship to lymphoid organ transit. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:291–301. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kersh GJ, Donermeyer DL, Frederick KE, White JM, Hsu BL, Allen PM. TCR transgenic mice in which usage of transgenic alpha- and beta-chains is highly dependent on the level of selecting ligand. J. Immunol. 1998;161:585–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yagi H, Matsumoto M, Nakamura M, Makino S, Suzuki R, Harada M, Itoh T. Defect of thymocyte emigration in a T cell deficiency strain (CTS) of the mouse. J. Immunol. 1996;157:3412–3419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukui Y, Hashimoto O, Sanui T, Oono T, Koga H, Abe M, Inayoshi A, Noda M, Oike M, Shirai T, Sasazuki T. Haematopoietic cell-specific CDM family protein DOCK2 is essential for lymphocyte migration. Nature. 2001;412:826–831. doi: 10.1038/35090591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Felix NJ, Donermeyer DL, Horvath S, Walters JJ, Gross ML, Suri A, Allen PM. Alloreactive T cells respond specifically to multiple distinct peptide-MHC complexes. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:388–397. doi: 10.1038/ni1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carlson CM, Endrizzi BT, Wu J, Ding X, Weinreich MA, Walsh ER, Wani MA, Lingrel JB, Hogquist KA, Jameson SC. Kruppel-like factor 2 regulates thymocyte and T-cell migration. Nature. 2006;442:299–302. doi: 10.1038/nature04882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell JJ, Pan J, Butcher EC. Cutting edge: developmental switches in chemokine responses during T cell maturation. J. Immunol. 1999;163:2353–2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takesono A, Horai R, Mandai M, Dombroski D, Schwartzberg PL. Requirement for Tec kinases in chemokine-induced migration and activation of Cdc42 and Rac. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:917–922. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nombela-Arrieta C, Mempel TR, Soriano SF, Mazo I, Wymann MP, Hirsch E, Martinez AC, Fukui Y, von Andrian UH, Stein JV. A central role for DOCK2 during interstitial lymphocyte motility and sphingosine-1-phosphate-mediated egress. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:497–510. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flanagan K, Moroziewicz D, Kwak H, Horig H, Kaufman HL. The lymphoid chemokine CCL21 costimulates naive T cell expansion and Th1 polarization of non-regulatory CD4+ T cells. Cell. Immunol. 2004;231:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.del Pozo MA, Sanchez-Mateos P, Sanchez-Madrid F. Cellular polarization induced by chemokines: a mechanism for leukocyte recruitment? Immunol. Today. 1996;17:127–131. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nieto M, Frade JM, Sancho D, Mellado M, Martinez AC, Sanchez-Madrid F. Polarization of chemokine receptors to the leading edge during lymphocyte chemotaxis. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:153–158. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanchez-Madrid F, del Pozo MA. Leukocyte polarization in cell migration and immune interactions. EMBO J. 1999;18:501–511. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gerard A, Mertens AE, van der Kammen RA, Collard JG. The Par polarity complex regulates Rap1- and chemokine-induced T cell polarization. J. Cell Biol. 2007;176:863–875. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo C, Pan H, Mines M, Watson K, Zhang J, Fan GH. CXCL12 induces tyrosine phosphorylation of cortactin, which plays a role in CXC chemokine receptor 4-mediated extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation and chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:30081–30093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605837200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kwan J, Killeen N. CCR7 directs the migration of thymocytes into the thymic medulla. J. Immunol. 2004;172:3999–4007. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ueno T, Saito F, Gray DH, Kuse S, Hieshima K, Nakano H, Kakiuchi T, Lipp M, Boyd RL, Takahama Y. CCR7 signals are essential for cortex-medulla migration of developing thymocytes. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:493–505. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kurobe H, Liu C, Ueno T, Saito F, Ohigashi I, Seach N, Arakaki R, Hayashi Y, Kitagawa T, Lipp M, Boyd RL, Takahama Y. CCR7-dependent cortex-to-medulla migration of positively selected thymocytes is essential for establishing central tolerance. Immunity. 2006;24:165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davalos-Misslitz AC, Rieckenberg J, Willenzon S, Worbs T, Kremmer E, Bernhardt G, Forster R. Generalized multi-organ autoimmunity in CCR7-deficient mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007;37:613–622. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krummel MF, Macara I. Maintenance and modulation of T cell polarity. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:1143–1149. doi: 10.1038/ni1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wabnitz GH, Kocher T, Lohneis P, Stober C, Konstandin MH, Funk B, Sester U, Wilm M, Klemke M, Samstag Y. Costimulation induced phosphorylation of L-plastin facilitates surface transport of the T cell activation molecules CD69 and CD25. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007;37:649–662. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gomez TS, Billadeau DD. T cell activation and the cytoskeleton: you can't have one without the other. Adv. Immunol. 2008;97:1–64. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)00001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.