Abstract

A number of forms of congenital muscular dystrophy (CMD) have been identified that involve defects in the glycosylation of dystroglycan with O-mannosyl-linked glycans. There are at least six genes that can affect this type of glycosylation, and defects in these genes give rise to disorders that have many aspects of muscle and brain pathology in common. Overexpression of one gene implicated in CMD, LARGE, was recently shown to increase dystroglycan glycosylation and restore its function in cells taken from CMD patients. Overexpression of Galgt2, a glycosyltransferase not implicated in CMD, also alters dystroglycan glycosylation and inhibits muscular dystrophy in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. These findings suggest that a common approach to therapy in muscular dystrophies may be to increase the glycosylation of dystroglycan with particular glycan structures.

Glycosylation is a powerful class of posttranslational modifications that can modulate both the chemical and biological properties of proteins and lipids. The number of potential modifications that can be achieved by glycosylation is vast. This is primarily due to the chemical nature of the glycans themselves. Carbohydrates may be attached to each other at multiple positions and in differing anomeric linkages. Carbohydrate chains may also be elongated to varying lengths and be further altered by sulfation, acetylation, phosphorylation, or other modifications. Many carbohydrate modifications are common to large numbers of proteins. For example, a number of human congenital disorders involve defects in the glycosylation pathway for the synthesis of N-linked glycans [1]. Because these glycans are present in all tissues, these disorders often present with complex groups of symptoms that can make diagnosis difficult. What is often lost on those uninitiated in the glycobiology literature is that there are also glycans that are highly specific for one or a handful of molecules. Polysialic acid, for example, is a relatively specific modification of NCAM in a number of vertebrate species, and loss of polysialic acid synthesis in mice can mimic loss of NCAM protein. Another such example, which is the topic of this review, involves the modification of dystroglycan by O-mannosyl-linked glycans. Like polysialic acid, O-linked mannose appears to be relatively specific modification for dystroglycan in mammals, and loss of O-mannosyl glycans in mice mimics loss of dystroglycan protein. Unlike congenital disorders of glycosylation involving the N-linked pathway, defects in the O-mannose pathway give rise to a distinct group of clinical findings. The clinical hallmark of all of these disorders is muscular dystrophy. A number of excellent reviews have been written on this topic in the past few years [2-8]. Therefore, this review will focus only on very recent literature and on the issues that remain in the field.

Dystroglycan

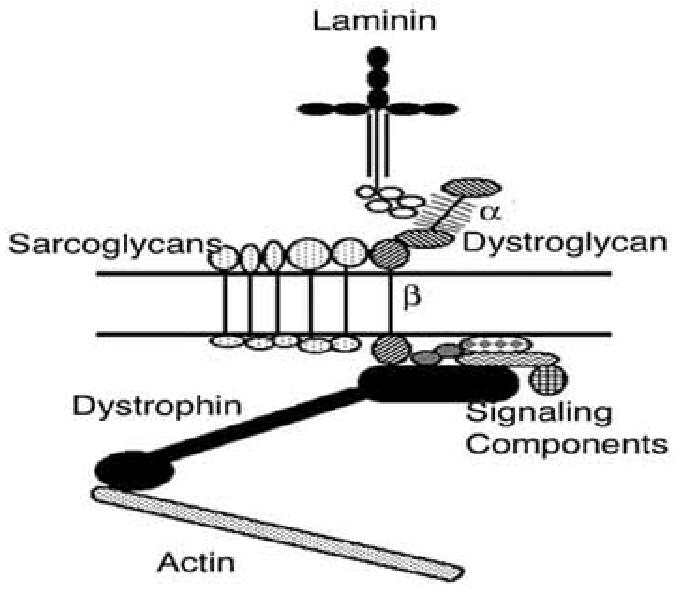

The glycosylation-dependent congenital muscular dystrophies (CMDs) are a class of neuromuscular disorders that all are defined by alterations in the glycosylation of alpha dystroglycan. Dystroglycan protein is synthesized as a single polypeptide that is then post-translationally cleaved into an alpha and a beta chain [9]. Alpha dystroglycan is a densely glycosylated peripheral membrane protein that binds to components of the extracellular matrix including laminin, agrin, and perlecan, as well as to membrane proteins such as neurexins and to infectious agents such as viruses and bacteria [10] (Fig. 1). The glycan chains comprising the O-linked structures in the middle third of alpha dystroglycan are necessary for the binding of extracellular ligands. Alpha dystroglycan also binds tightly to beta dystroglycan, a transmembrane glycoprotein. The intracellular domain of beta dystroglycan, in turn, binds dystrophin or its autosomal homologue utrophin. Dystrophin (and utrophin) bind to filamentous actin as well as to a myriad of potential structural and signaling components, including dystrobrevins, syntrophins, and neuronal nitric oxide synthase, amongst others. The sarcoglycans are additional transmembrane components of this protein complex. This group of proteins is collectively referred to as the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex, with the intracellular components sometimes referred to as dystrophin-associated proteins.

Fig. (1). Dystroglycan glycosylation and its place in the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex.

Laminin, which is present in the extracellular matrix surrounding the myofiber membrane, binds to α dystroglycan. This interaction requires the O-mannosyl-linked glycans present in the middle third of the α dystroglycan molecule. α dystroglycan binds to β dystroglycan, which spans the muscle membrane. The intracellular domain of β dystroglycan binds to dystrophin, which links the complex both to actin and to number of signaling components. The sarcoglycans are additional transmembrane components within the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex.

Loss of expression of most proteins within the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex causes muscular dystrophy [11]. Muscular dystrophy is a term that collectively refers to a neuromuscular disorders associated with the wasting of skeletal muscles. Other tissues, cardiac muscle in particular, can also be severely affected. Loss of dystrophin protein expression causes Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a severe X-linked myopathy. Becker muscular dystrophy, which has a milder disease progression, results from partial loss of dystrophin expression or function. Loss of sarcoglycans cause forms of Limb-Girdle muscular dystrophy, and loss of laminin alpha 2 expression results in congenital muscular dystrophy MDC1A.

New components in the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex are still being discovered, and how these new proteins relate to neuromuscular disease is a subject of intense interest. Of particular note here is the recent demonstration that the dystrophin-associated protein syntrophin can bind to the beta gamma subunits of trimeric G proteins, including those that modulate Gs [12]. The same study goes on to show that laminin binding to dystroglycan serves to recruit beta-gamma to the membrane and inhibit Gs activity. Gs can activate the dihydropyridine receptors in the skeletal muscle membrane that stimulate calcium entry. Thus, loss of the laminin linkage in dystrophic muscles may elevate cytoplasmic calcium levels, which is a well reported finding in dystrophic muscle cells [13]. Dystroglycan also interacts with other signal transduction cascades that could have pleiotropic effects on skeletal muscle, including ERK-MAP kinases [14], and PI3-Akt kinases [15], and Rac-JNK [16]. Thus, dystroglycan may play an important role not only in maintaining the structure of the plasma membrane via its ability to connect extracellular matrix proteins through the membrane to actin-binding proteins, but may also be involved in transmembrane signaling events initiated by extracellular ligands.

Dystroglycan is at the center of the dystrophin-associated complex and is essential for its function in maintaining muscle membrane stability. The proper glycosylation of dystroglycan protein with O-linked glycans is essential for its function in binding to the extracellular matrix [17], which is in turn central to its role in maintaining membrane stability. These O-linked glycans structures are a mix of O-linked mannose chains of the type NeuAcα2,3Galβ1, 4GlcNAcβ1,2Manα-O and O-linked GalNAc structures of the type Galβ1,3GalNAcα-O [18-20]. While glycans that are O-linked via GalNAc are common on many mammalian glycoproteins, there are only several glycoproteins reported to have O-linked mannose [see 10]. There are roughly 50 sites for O-linked glycosylation in the middle third of the dystroglycan molecule [9, 10]. Thus, this region is intensely glycosylated with such structures, much as is seen with other mucin-like proteins, and this explains why dystroglycan is about 50% carbohydrate by molecular weight. The expression of these two types of O-linked glycan chains has been found on all three forms of dystroglycan protein where glycan sequencing has been reported [18-20]. Additional glycan structures that may exist on these O-linked chains are α1,3 linked fucose [20], terminal β1,4 linked GalNAc [21], which is normally confined to expression at the neuromuscular junction [22], and HNK-1 [18]. Ervasti and Campbell showed in the early 1990's that removal of the O-linked chains on alpha dystroglycan inhibits the ability of laminin to bind to the protein, effectively divorcing the extracellular matrix from the muscle membrane [17]. Removal of N-linked chains, by contrast, had no effect [17]. This early biochemical demonstration of the importance of the O-linked glycan chains has been confirmed in a dramatic way by the discovery that defects in genes that modify this aspect of dystroglycan glycosylation also inhibit the binding of laminin [23] and cause muscular dystrophy [24-30].

Glycosylation-Dependent Muscular Dystrophies

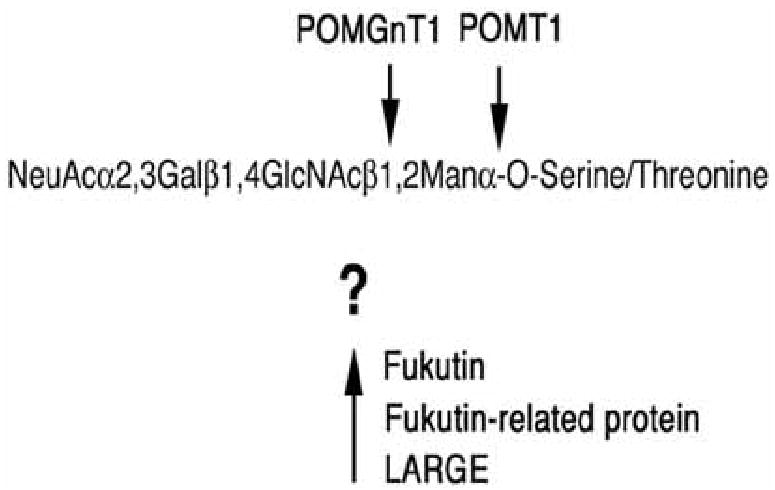

Thusfar, six genes have been shown to cause forms of human congenital muscular dystrophy where dystroglycan glycosylation is affected. These include POMT1 and POMT2 - Walker Warburg syndrome (WWS) [24,30], POMGnT1-Muscle Eye Brain Disease (MEB) [25], Fukutin- Fukuyama congenital muscular dystrophy (FCMD) [26], Fukutin-related protein (FKRP)-Congenital muscular dystrophy 1C (MDC1C) [27], Limb Girdle Muscular dystrophy 2I (LGMD2I) [28], and WWS [31], and LARGE-Congenital muscular dystrophy 1D (MDC1D) [29] (Fig. 2). All of these are autosomal recessive disorders. POMT1 (Protein O- mannosyltransferase I) was identified in WWS by a candidate gene approach based on its homology with yeast O-mannosyltransferases [24]. The enzymes encoded by these genes transfer mannose in an O-linkage to serine or threonine residues of proteins. In the original report, nonsense, frameshift, and missense mutations were identified in POMT1 in 6 of 30 unrelated WWS patients [24]. Mutations in POMT2 also are identified with WWS [30]. POMT1 and POMT2 mutations only account for a fraction of WWS cases, and this means that defects in other genes must also cause this disease. POMT1 encodes a 3.1kB mRNA that is predicted to produce an integral membrane protein of the endoplasmic reticulum. POMT1 transcripts are ubiquitously expressed, with highest expression in testes and fetal brain, and the POMT1 gene has been localized to human chromosome 9q34.1. POMT2 is localized to human chromosome 14q24.3. Base substitutions, deletions, and frameshift mutations in the POMGnT1 (Protein O mannosyl β1,2 N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase I) gene have been shown to cause muscle-eye-brain disease (MEB) [25]. POMGnT1 gene defects associated with disease are all loss of function changes [32, 33]. POMGnT1 encodes a 3kBa mRNA that is ubiquitously expressed, as well as a 3.4 kB transcript that is expressed in spinal cord, lymph node and trachea. POMGnT1 is predicted to be a Golgi-associated type II transmembrane protein and the gene has been mapped to human chromosome 1p33-34. Fukutin defects give rise to FCMD, a disease found almost exclusively in Japan [26]. Patients of Japanese descent usually carry a retrotransposonal insertion in the 3′ untranslated region of the fukutin gene [26], though other point mutations have also been described [34]. Fukutin encodes a 4 kb mRNA is most highly expressed in fetal brain, but it is present in many adult tissues, including skeletal muscle, and the gene has been mapped to human chromosome 9q31. Fukutin-related protein (FKRP) mutations cause either a severe form of congenital muscular dystrophy (MDC1C) [27] or limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 2I (LGMD2I) [28], which is more variable in its clinical presentation. FKRP mutations also can give rise to WWS [31]. FKRP encodes a 4kb transcript that is highly expressed in brain, muscle, placenta, and heart, and is weakly expressed in numerous other tissues. FKRP has been mapped to human chromosome 19q13.3. A single compound mutation/deletion in the LARGE gene has been reported in a child with severe mental retardation, white matter changes, and congenital muscular dystrophy, termed MDC1D [29]. LARGE encodes a 4.3kb cDNA that is predicted to be a transmembrane tandem glycosyltransferase (i.e., it has two potential glycosyltransferase domains). A deletion in LARGE is also the genetic defect in the myodystrophy (myd) mouse [35], a mouse with muscular dystrophy and brain pathology. The LARGE gene has been mapped to human chromosome 22q12.3-q13.1.

Fig. (2). Genes affecting dystroglycan glycosylation associated with congenital muscular dystrophy.

The O-mannosyl linked glycans on α dystroglycan are comprised of linear chain of four carbohydrates. There are six genes known to cause congenital muscular dystrophy that alter the glycosylation of dystroglycan on its O-linked chains. POMT1 and POMT2 (defective in Walker Warburg syndrome) are both required to synthesize the O-mannosyl linkage and POMGnT1 (defective in muscle-eye-brain disease) synthesizes the β1,2GlcNAc linkage. Three other genes also likely affect this pathway; fukutin (defective in Fukuyama congenital muscular dystrophy, fukutin-related protein (FKRP, defective in congenital muscular dystrophy 1C, Limb Girdle muscular dystrophy 2I, and WWS), and LARGE (defective in congenital muscular dystrophy 1D). The function of these three genes is not currently known.

There are two findings that are common to all of the congenital muscular dystrophies caused by defects in these six genes; First, all are associated with an apparent underglycosylation of alpha dystroglycan in skeletal muscle. Second, all have muscular dystrophy as a main clinical finding. There are features of these disorders that are also quite distinct. WWS, MEB, and FCMD patients have a myriad of brain and eye abnormalities in addition to muscular dystrophy. Brain findings include coarse gyri with an abnormally nodular surface (“cobblestone cortex”, which can be agyric in the extreme), cerebellar cysts, pontocerebellar hypoplasia, absent or reduced corpus collosum, hydrocephalus, and hypomyelination of the white matter. The defective migration of cortical neurons that gives rise to the aberrant patterning of the cortex is most likely secondary to defects in the pial glia-limitans membrane. Eye abnormalities include congenital glaucoma, retinal dysplasia or detachment, microopthalmia, myopia, atrophy of the optic nerve, buphthalmos, and anterior chamber defects. These findings are distinct from the more classical muscular dystrophies like Duchenne, which have few neurological findings. The muscular dystrophies caused by fukutin-related protein also appear to be distinct in that MDC1C and LGMD2I typically do not present with this spectrum of brain and eye findings [27, 28]. A recent report by Muntoni and colleagues, however, demonstrates severe CNS defects in several patients with FKRP mutations, and these defects mimic those observed in WWS and MEB [36]. Thus, the lesser brain and eye pathology in most MDC1C (and LGMD2I) cases may merely be a reflection of the fact that those patients maintain partial FKRP function. Until more patients with LARGE mutations are reported, it is difficult to know the extent to which this report places LARGE in the spectrum of findings found in WWS, MEB, FCMD, and MDC1C. However, the myd mouse contains a deletion in LARGE that is most likely a loss of LARGE function [35]. These mice have defects in cortical migration that are similar, though not nearly as severe, as WWS.

A key question in the field is the extent to which glycoyslation defects in CMDs are due to loss of dystroglycan function. After all, glycosylation usually affects more than one protein. Therefore, loss of a glycan structure typically affects multiple protein functions. Almost all the data thusfar, however, support the contention that defects in O-mannosylation are entirely due to loss of dystroglycan function, and this is consistent with the biochemical evidence suggesting that O-mannosylation is restricted to a small number of proteins in mammals. Loss of dystroglycan is lethal in the mouse at an early embryonic stage of development due to loss of Reichert's membrane [37]. Recent reports demonstrate that loss of fukutin [38] and POMT1 [39] also result in embryonic lethality in the same time period, with POMT1 having defects in Reichert's membrane [39]. Reichert's membrane is a rodent-specific structure. As such, the embryonic lethality in these animals is probably not relevant to human disease. Nevertheless, the similar phenotype of fukutin, POMT1, and dystroglycan in mice suggests that fukutin and POMT1 are essential to dystroglycan function. Chimeric mice lacking fukutin in some cells also mimicked the spectrum of findings in FCMD, including disorganization of the laminar pattern of the cortex, intrahemispheric fusion, hippocampal and cerebellar dysgenesis, retinal detachment, and severe muscular dystrophy [38]. In addition, loss of dystroglycan protein in mouse brain [40], peripheral nerve [41], and skeletal muscle [42] at later developmental stages also give rise to most of the findings in WWS, MEB, and FCMD. Collectively, these results strongly suggest that most of the spectrum of clinical findings in these disorders are caused by the direct impact of the glycosylation defect on dystroglycan function. Consistent with this hypothesis, Campbell and colleagues have shown that hypoglycosylated dystroglycan taken from skeletal muscle of FCMD, MEB, and WWS patients, as well as from the myd mouse, does not bind laminin or other matrix components with significant affinity [23].

There are several results, however, that are inconsistent with this model. The first is the fact that myd mice, which have a deletion in LARGE, survive to adulthood, despite the fact that dystroglycan taken from these mice appears to be equally poor at binding laminin as compared with dystroglycan taken from muscles of other CMD types. One would expect myd mice to be as impaired as fukutin and POMGnT1 null mice, based on their laminin binding defect, but those mice die at embryonic day 6-7, while myd mice are born and live for several months. Second, the expression of fukutin, POMGnT1, and dystroglycan is not always coincident in various cells and tissues [43-45]. This suggests that there may be glycoproteins other than dystroglycan that are modified by these genes. For example, fukutin, POMGnT1 and dystroglycan are all highly expressed in late embryonic and early postnatal development within the external granule cell layer of the cerebellum, including granule cell neurons [45]. Only POMGnT1 and fukutin, however, are highly expressed in the internal granule cell layer after granule neuron migration has occurred, while dystroglycan mRNA is highly down-regulated [45]. Third, defects in genes other than dystroglycan can give rise to defects such as those found in WWS. For example, loss of laminin γ 1, integrin β1, or FAK, a tyrosine kinase that phosphorylates integrins, all cause defects in the pial-glia limitans membrane [46, 47]. Thus, defects in these proteins may also alter the migration of cortical neurons as is seen in WWS, MEB, and FCMD.

Because LARGE, Fukutin, FKRP, POMT1, POMT2, and POMGnT1 all affect dystroglycan glycosylation and cause human disease, there is intense interest in understanding how these genes function to affect the glycosylation of the dystroglycan protein. It is clear from recent studies that POMT1 and POMGnT1 are glycosyltransferases that can respectively synthesize the first two O-linked glycans of the O-mannosyl glycan chains on alpha dystroglycan. Based on homology with yeast, two O-mannosyltransferase genes have been identified in humans, POMT1 and POMT2 [8]. Recently, POMT1 was shown to modify a recombinant form of alpha dystroglycan with O-linked mannose [48]. POMT2 co-expression was necessary for the induction of O-mannosyltransferase activity, suggesting that these two proteins work in an oligomeric complex. This is consistent with a recent RNAi study in flies that also showed that the phenotype of POMT2 knockdown mutant flies was the same (twisted abdomen) as classical POMT1 mutant flies [49]. Moreover, the POMT1/POMT2 double mutant flies had a more pronounced phenotype than either single mutant. Thus, POMT1 and POMT2 both appear to be essential for expression of O-mannose on alpha dystroglycan. The fly story, however, is clearly is different than the story in humans and mice. Mutant dystroglycan in flies does not give a twisted abdomen phenotype. Moreover, there is no orthologue of POMGnT1 in flies to suggest that the O-mannose chains are elongated as they are in mammals. Thus, both the O-mannose glycosylation pathway and the glycoproteins affected by it appear to be different in flies and mammals.

POMGnT1 was shown be Schachter and colleagues [50] and by Endo and colleagues [25] to be a UDP-GlcNAc: β1,2Manα-O-N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase. This enzyme is highly specific for O-linked mannose and does not transfer GlcNAc onto the mannose linkages typically found on N-linked oligosaccharides. Thus, POMGnT1, like POMT1, is relatively specific for dystroglycan, as dystroglycan is one of only several mammalian proteins shown to contain O-linked mannose. Reductions in POMGnT1 activity occur in muscle-eye-brain disease (MEB) [32,33]. Thus, there is no doubt that this gene functions to affect the glycosylation of alpha dystroglycan and that this activity is lost in MEB. The subsequent two linkages that decorate the O-linked mannose chains on dystroglycan, NeuAcα2, 3Galβ1,4, would be made by sialyltransferases and galactosyltransferases, respectively. Many of the genes that encode these two classes of enzymes have been cloned and studied for many years, and none of these genes are implicated in CMDs. Because fukutin, FKRP, and LARGE do not have any homology to known α2,3 sialyltransferase or β1,4 galactosyltransferase genes, they are not likely to possess such activities. Moreover, because many proteins contain the types of sialic acid and galactose linkages found on the O-mannose chains of dystroglycan, it is unlikely that the defective synthesis of these glycans would give rise to the relatively specific muscle, eye, and brain findings found in these CMDs.

The data to suggest that LARGE is a glycosyltransferase are far from clear, and there is no evidence fukutin and FKRP directly synthesize glycans. LARGE has a domain structure that suggests that it has two glycosyltransferase domains. More importantly, overexpression of LARGE in muscle cells taken from patients with MEB, WWS, or FCMD can increase the glycosylation of alpha dystroglycan and rescue laminin binding [51]. This result narrows the possible roles of LARGE in the glycosylation pathway. If the O-mannosyl glycan chains are reduced in amount on alpha dystroglycan taken from WWS muscle, as one would expect, then LARGE would not be able to further modify those chains with GlcNAc or other glycans. LARGE, however, is clearly able to increase dystroglycan glycosylation in WWS muscle cells to a level that is equivalent to or even greater than that seen in wild type muscle. The high degree of alpha dystroglycan glycosylation in these experiments suggests one of five possibilities: 1. LARGE could be affecting glycans (eg. Sialic acid) that come later in the O-mannose pathway and that could still be present in WWS muscle. 2. LARGE could modify other kinds of O-linked chains on dystroglycan (such as O-linked GalNAc). 3. LARGE could utilize linkages that are not via an O-linkage at all (eg N-linked glycans or glycosaminoglycans). 4. LARGE could modify a glycoprotein other than dystroglycan, or 5. LARGE could replace POMT1 in activating POMT2 or related glycosyltransferase activities, thereby overcoming the O-mannose defect in WWS.

The tandem glycosyltransferase domain structure of LARGE is reminiscent of enzymes involved in disaccharide synthesis of glycosaminoglycans [52]. While alpha dystroglycan has been reported not to have glycosaminoglycans, it is possible that the high induction of glycosylation resulting from LARGE overexpression could be due to synthesis of a polydisaccharide repeat such as poly-N-acetyllactosamine. Mouse laminin-1 from the Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm (EHS) tumor, for example, has such chains [10]. The synthesis of disaccharide repeats by LARGE would allow it to glycosylate dystroglycan to a very high degree, much as can occur with glycosoaminoglycan synthesis. Indeed, overexpression of LARGE in WWS muscle cells increases dystroglycan glycosylation beyond wild type levels [51], which would be consistent with this mode of glycosylation.

LARGE has been reported to interact with the N-terminal domain of dystroglycan, opening up the possibility that dystroglycan itself may regulate LARGE activity [53]. In the same study, Campbell and colleagues provided evidence suggesting that the N-terminal domain of dystroglycan, which is separate from the region containing O-linked glycans, was required for ligand binding. This study suggests that the model for laminin binding to dystroglycan is more complex than a simple binding to the O-linked mannose glycan chains. The evidence in this regard comes from an analysis of laminin binding to recombinant fragments of dystroglycan containing deletions of its various protein domains, and is very similar to results on the mapping of arenavirus binding to dystroglycan, which also found a requirement for both the N-terminal domain and the mucin region [54]. The authors interpret this data to mean that O-linked glycans alone are insufficient for laminin binding in the absence of the N-terminal fragment. Unfortunately, since no data was presented as to the glycosylation state of these recombinant fragments, it is equally possible that the N-terminus is required for proper glycosylation of the mucin domain, and that this is its role in affecting ligand-binding interactions. This would be consistent with the demonstrated interaction of the N-terminal domain with LARGE. Indeed, there are other examples where a non-mucin domain is required for the proper glycosylation of a mucin fragment on the same glycoprotein [55]. Cleavage of the N-terminus on an already glycosylated full-length alpha dystroglycan protein by furin, an endoprotease, was recently shown not to inhibit laminin binding [56], which again would be consistent with this possibility.

While loss of fukutin and FKRP expression clearly alter the extent of dystroglycan glycosylation, the primary sequence of these genes is not homologous to other known glycosyltransferases. Thus, their role in the O-mannose pathway is very unclear. Fukutin and FKRP are expressed either in the endoplasmic reticulum or Golgi apparatus. There is disagreement in the literature as to which protein is in which compartment [57, 58]. Regardless, their expression in these organelles is consistent with their ability to interact with and potentially modulate POMT1, POMGnT1, LARGE, or other glycosyltransferases. How they accomplish this is an important aspect of the glycosylation puzzle that remains to be solved. One obvious possibility is that FKRP or fukutin are required for POMT1, POMT2, POMGnT1, or LARGE activity. FKRP and/or fukutin could alter the processivity of these enzymes or binding of these enzymes to substrates such as UDP-GlcNAc or GDP-Man. Either of these scenarios could lower the density of glycans present on alpha dystroglycan. Loss of fukutin or FKRP could also cause the appropriate capping of the four carbohydrate O-mannose chains with glycans that could not be further modified. Another possibility is that loss of fukutin or FKRP function would alter the migration time of dystroglycan through the secretory pathway. This could lower the extent of glycosylation by reducing the time in which POMT1 or related enzymes could act on dystroglycan.

Glycotherapy For Muscular Dystrophy

There are two recent and dramatic examples where overexpression of a gene involved in muscle glycosylation inhibited the development of muscular dystrophy. In one study, Campbell and colleagues showed that overexpression of LARGE in primary cells from patients with MEB, FCMD, and WWS increased the glycosylation of alpha dystroglycan and its ability to bind laminin and that overexpression of LARGE in myofibers of the myd mouse inhibited the development of muscular dystrophy [51]. In the other, increased expression of Galgt2, a glycosyltransferase that can modify alpha dystroglycan, altered the expression of dystrophin-associated glycoproteins including utrophin in skeletal muscle and inhibited muscular dystrophy in the mdx model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy [59]. These two studies suggest that modulation or mimicry of glycosyltransferase activities that act on dystroglycan may be an important target for the development of therapies in several forms of muscular dystrophy. This may not only be the case in glycosylation-dependent CMDs, but also in forms of muscular dystrophy such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy where defective glycosylation is not a causative factor.

The recent demonstration that overexpression of LARGE can improve dystroglycan function in all glycosylation-dependent CMDs is very exciting [51]. The inference of this work is that LARGE is epistatic to all other genes in the O-mannose pathway, and thus can overcome all glycosylation defects caused by their absence. The authors first showed that overexpression of LARGE using adenovirus-mediated transfer in the myd mouse (which is deleted for the LARGE gene) can restore alpha dystroglycan glycosylation, laminin binding to dystroglycan, and sarcolemmal membrane integrity. While this should not come as a surprise (that expression of a normal gene can overcome its own absence), it is nevertheless significant as it shows that the defects caused by LARGE, including muscular dystrophy, are preventable. They then went on to show that overexpression of LARGE in cells taken from patients with FCMD (myoblasts), MEB (fibroblasts), and WWS (myoblasts) increased both dystroglycan glycosylation and laminin binding. Equally important, overexpression of POMGnT1 in FCMD myoblasts had no effect on dystroglycan glycosylation. This shows that the effects seen with LARGE are not common to all of the genes that affect the O-mannose pathway. Moreover, it suggests that fukutin may act at the same point in the glycosylation pathway as POMT1. This would explain why POMGnT1 overexpression would be ineffective in FCMD cells, as there would be no O-mannose present as a substrate for it to act on. Unlike POMGnT1, LARGE appears not to require POMT1 for its activity, and thus has a unique status in this pathway. The possibility that LARGE could be used as a target for all of these diseases is a profound observation.

There is one caveat, however, that should raise some suspicion as to therapeutic efficacy of LARGE, and that is that overexpression of LARGE causes glycosylation of alpha dystroglycan beyond what normally occurs in wild type muscle, both in cell lines and in mice [51]. Thus, total content of glycosylation on dystroglycan and also likely the length of the glycan chains is not normal in these experiments. This could give rise to autoantibody responses against glycan chains that spread beyond the normal glycocalyx of the muscle membrane or to the inappropriate binding of extracellular ligands. Indeed, LARGE overexpression in primary cells was associated with significant (15%) toxicity [51]. Thus, the stimulation of LARGE expression or activity may not be simple to put into practice regarding therapy, but such factors could presumably be addressed by calibrating gene or drug dosing.

Another gene that can inhibit the development of muscular dystrophy is Galgt2. Galgt2 is the gene that encodes the cytotoxic T cell (CT) UDP-GalNAc:N-acetylgalactosaminyl (GalNAc) transferase. This gene was cloned based on its activity in transferring GalNAc in a β1,4 linkage from UDP-GalNAc onto sialyl-N-acetyllactosamine (NeuAcα2, 3Galβ1,4GlcNAc) and related substrates [60]. The antigen created by this (GalNAcβ1,4[NeuAcα2,3] Galβ1,4GlcNAc is called the cytotoxic T cell (CT) antigen. This name comes from the original finding by Lefrancois and colleagues that antibodies that recognize this type of glycan structure specifically bind to the activated state of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in the mouse [61]. The CT antigen, however, is expressed in a number of other tissues [62]. In skeletal muscle, the CT carbohydrate antigen is confined to the neuromuscular junction [22], as is all terminal GalNAc [63, 64]. The synaptic expression of the CT carbohydrate antigen in skeletal muscle likely comes from local synthesis by Galgt2 [21]. The substrate that Galgt2 acts on, NeuAcα2,3Galβ1,4GlcNAc, contains three of the four glycans found on the O-mannose chains of alpha dystroglycan [18-20]. Thus, it is not surprising that overexpression of Galgt2 in skeletal muscles causes glycosylation of alpha dystroglycan with the CT antigen [21]. What is surprising is that alpha dystroglycan is the only glycoprotein identified with the CT antigen in such overexpression experiments [21]. This was similar to the original studies in CD8+ T cells, where the mucin-containing protein CD45 was the only glycoprotein modified by the CT antigen [61]. Thus Galgt2 activity, like the O-mannose pathway itself, may be relatively specific for a small number of proteins.

Dystroglycan interacts with proteins at the neuromuscular junction that are different from the ones it interacts with on the rest of the myofiber membrane. These include novel synaptic forms of laminin (α4 and α5) and utrophin [10]. These proteins are highly homologous to proteins that bind dystroglycan in the extrasynaptic membrane of muscle (laminin α2 and dystrophin). Since glycosylation is required for dystroglycan function, synaptic modifications such as the CT antigen are likely to play a role in altering dystroglycan's interactions with synaptic proteins. Consistent with this idea, transgenic mice that overexpress Galgt2 in their skeletal muscles have ectopic expression of synaptic laminins and utrophin [21]. In Galgt2 transgenic mdx mice, where dystrophin is not present, there was no evidence of muscle cell degeneration many months after such degeneration was evident in non-transgenic mdx littermates. Thus, altering dystroglycan such that it contains a normally synaptic carbohydrate modification alters its function such that it can overcome dystrophin-deficiency. While the mechanism for the inhibition of muscular dystrophy remains to be elucidated, this data clearly suggests that modification of dystroglycan may be an approach to therapy even in forms of muscular dystrophy where glycosylation defects are not causing the disease.

Conclusions

There is a wealth of biochemical and genetic data to show that genes involved in the O-mannose glycosylation pathway cause forms of congenital muscular dystrophy. Since these glycans are required for the binding of ligands such as laminin to dystroglycan, these gene defects are likely act to cause disease by severing the binding of extracellular matrix proteins in the muscle basal lamina to dystroglycan in the muscle membrane. Both brain and eye defects in these disorders are also likely come from defective binding of proteins to dystroglycan. In the coming years, there will be new genes identified in this pathway that cause CMDs, and much work remains on understanding the function of the already known genes and their relationship to one another. Since defects in glycosylation pathways are often highly pleiotropic due to the common nature of this type of posttranslational modification, the relatively specific nature of the O-mannose pathway to dystroglycan makes it one of the best systems in which to understand not only the contribution of glycosylation to disease but the mechanisms involved in the fundamentally important process of protein glycosylation. The demonstration that manipulations of protein glycosylation can also have a therapeutic benefit in models of these disorders makes the understanding of these processes all the more important.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (AR050202 and AR049722) and the Muscular Dystrophy Association to PTM.

References

- 1.Freeze HH. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7(4):???–???. doi: 10.2174/156652407780831566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin PT, Freeze HH. Glycobiology. 2003;13:67R–75R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michele DE, Campbell KP. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15457–15460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muntoni F, Brockington M, Torelli S, Brown SC. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004;17:205–209. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200404000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Endo T, Toda T. Biol Pharm Bull. 2003;26:1641–1647. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grewall PK, Hewitt JE. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:R259–264. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schachter H, Vajsar J, Zhang W. Glycoconj J. 2004;20:291–300. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000033626.65127.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willer T, Camern Valero M, Tanner W, Cruces J, Strahl S. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:621–630. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, Ervasti JM, Leveille CJ, Slaughter CA, Sernett SW, Campbell KP. Nature. 1992;355:696–702. doi: 10.1038/355696a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin PT. Glycobiology. 2003;13:55R–66R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blake DJ, Weir A, Newey SE, Davies KE. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:291–329. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou YW, Oak SA, Senogles SE, Jarrett HW. Am J Physiol. 2004;288:C377–388. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00279.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopf FW, Turner PR, Denetclaw WF, Reddy P, Steinhardt RA. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C1325–1339. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.4.C1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spence HJ, Dhillon AS, James M, Winder SJ. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:484–489. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langenbach KJ, Rando TA. Muscle Nerve. 2002;26:644–653. doi: 10.1002/mus.10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oak SW, Zhou YW, Jarrett HW. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39287–39295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ervasti JM, Campbell KP. Cell. 1991;66:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90035-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiba A, Matsumura K, Yamada H, Inazu T, Shimizu T, Kusonoki S, Kanazawa I, Kobata A, Endo T. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2156–2162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sasaki T, Yamada H, Matsumura K, Shimizu T, Kobata A, Endo T. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1998;1425:599–606. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smalheiser NR, Haslam SM, Sutton-Smith M, Morris HR, Dell A. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23689–23703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia B, Hoyte K, Kammesheidt A, Deerinck T, Ellisman M, Martin PT. Dev Biol. 2002;242:58–73. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin PT, Scott LJC, Porter BE, Sanes JR. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;13:105–118. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michele DE, Barresi R, Kanagawa M, Saito F, Cohn RD, Satz JS, Dollar J, Nishino I, Kelley RI, Somer H, Straub V, Mathews KD, Moore SA, Campbell KP. Nature. 2002;418:417–422. doi: 10.1038/nature00837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beltran-Valero de Bernabe D, Currier S, Steinbrecher A, Celli J, Beusekom E, van er Zwaag B, Kayersili H, Merlini L, Chitayat D, Dobyns WB, Cormand B, Lehesjoki AE, Cruces J, Voit T, Walsh CA, van Bokhoven H, Brunner HG. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:1033–1043. doi: 10.1086/342975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida A, Kobayashi K, Manya H, Taniguchi K, Kano H, Mizuno M, Inazu T, Mitsuhashi M, Takahashi S, Takeuchi M, Hermann R, Straub V, Talim B, Voit T, Topaloglu H, Toda T, Endo T. Dev Cell. 2001;1:717–724. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi K, Nakahori Y, Miyake M, Matsumura K, Kondo-Iida E, Nomura Y, Segawa M, Yoshioka M, Saito K, Osawa M, Hamano K, Sakakihara Y, Nonaka I, Nakagome Y, Kanazawa I, Nakamura Y, Tokunaga K, Toda T. Nature. 1998;394:388–392. doi: 10.1038/28653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brockington M, Blake DJ, Prandini P, Brown SC, Torelli S, Benson MA, Ponting CP, Estournet B, Romero NB, Mercuri E, Voit T, Sewry CA, Guicheney P, Muntoni F. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1198–1209. doi: 10.1086/324412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brockington M, Yuva Y, Prandini P, Torelli S, Benson MA, Hermann R, Anderson LV, Bashir R, Burgunder JM, Fallet S, Romero N, Fargeau M, Straub V, Storey G, Pollit C, Richard I, Sewry CA, Bushby K, Voit T, Blake DJ, Muntoni F. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:2851–2859. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.25.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Longman C, Brockington M, Torelli S, Jimenez-Mallebrera C, Kennedy C, Khalil N, Feng L, Saran RK, Voit T, Merlini L, Sewry CA, Brown SC, Muntoni F. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2853–2861. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Reeuwijk J, Janssen M, van den Elzen C, Beltran-Valero de Bernabe D, Sabatelli P, Merlini L, Boon M, Scheffer H, Brockington M, Muntoni F, Huynen MA, Verrips A, Walsh CA, Barth PG, Brunner HG, van Bokhoven H. J Med Genet. 2005;42:907–912. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.031963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beltran-Valero de Bernabe D, Voit T, Longman C, Steinbrecher A, Straub V, Yuva Y, Hermann R, Sperner J, Korenke C, Diesen C, Dobyns WB, Brunner HG, van Bokhoven H, Brockington M, Muntoni F. J Med Genet. 2004;41:e61. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.013870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang W, Vajsar J, Cao P, Breningstall G, Diesen C, Dobyns W, Hermann R, Leheshoki AE, Steinbrecher A, Talim B, Toda T, Topaloglu H, Voit T, Schachter H. Clin Biochem. 2003;36:339–344. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(03)00036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manya H, Sakai K, Kobayashi K, Taniguchi K, Kawakita M, Toda T, Endo T. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;306:93–97. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00924-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kondo-Iida E, Kobayashi K, Watanabe M, Sasaki J, Kumagai T, Koide H, Saito K, Osawa M, Nakamura Y, Toda T. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2303–2309. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.12.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grewal PK, Holzfeind PJ, Bittner RJ, Hewitt JE. Nature Genet. 2001;28:151–154. doi: 10.1038/88865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beltran Valero de Benrae D, Voit T, Longman C, Steinbrecher A, Straub V, Yuva Y, Hermann R, Sperner J, Korenke C, Diesen C, Dobyns WB, Brunner HG, van Bokhoven H, Brockington M, Muntoni F. J Med Gen. 2004;41:e61. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.013870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williamson RA, Henry MD, Daniels KJ, Hrstka RF, Lee JC, Sunada Y, Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, Campbell KP. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:831–841. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.6.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takeda S, Kondo M, Sasaki J, Kurahashi H, Kano H, Arai K, Misaki K, Fukui T, Kobayashi K, Tachikawa M, Imamura M, Nakamura Y, Shimizu T, Murakami T, Sunada Y, Fujikado T, Matsumura K, Terashima T, Toda T. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1449–1459. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willer T, Prados B, Falcon-Perez JM, Renner-Muller I, Przemeck GKH, Lommel M, Coloma A, Camen Valero M, Hrabe de Angelis M, Tanner W, Wolf E, Strahl S, Cruces J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14126–14131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405899101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore SA, Saito F, Chen J, Michele DE, Henry MD, Messing A, Cohn RD, Ross-Barta SE, Westra S, Williamson RA, Hoshi T, Campbell KP. Nature. 2002;418:422–425. doi: 10.1038/nature00838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saito F, Moore SA, Barresi R, Henry MD, Messing A, Ross-Barta SE, Cohn RD, Williamson RA, Sluka KA, Sherman DL, Brophy PJ, Schmelzer JD, Low PA, Wrabetz L, Feltri ML, Campbell KP. Neuron. 2003;38:747–758. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohn RD, Henry MD, Michele DE, Barresi R, Saito F, Moore SA, Flanagan JD, Skwarchuk MW, Robbins ME, Mendell JR, Williamson RD, Campbell KP. Cell. 2002;110:639–648. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00907-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamamoto T, Kato Y, Karita M, Kawaguchi M, Shibata N, Kobayashi M. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;31:183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saito Y, Yamamoto T, Ohtsuka-Tsurumi E, Oka A, Mizuguchi M, Itoh M, Voit T, Kato Y, Kobayashi M, Saito K, Osawa M. Brain Dev. 2004;26:69–479. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henion TR, Qu Q, Smith FL. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;112:177–181. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montanaro F, Carbonetto S. Neuron. 2003;37:193–196. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beggs HE, Schahin-Reed D, Zang K, Goebbels S, Nave K, Gorski J, Jones KR, Sretavan D, Reichardt LF. Neuron. 2003;40:501–514. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00666-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manya H, Chiba A, Yoshida A, Wang X, Chiba Y, Jaigami Y, Margolis R, Endo T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:500–505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307228101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ichimiya T, Manya H, Ohmae Y, Yoshida H, Takahashi K, Ueda R, Endo T, Nishihara S. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:42638–42647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang W, Betel D, Schachter H. Biochem J. 2002;361:153–162. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3610153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barresi R, Michele DE, Kanagawa M, Harper HA, Dovico SA, Satz JS, Moore SA, Zhang W, Schachter H, Dumanski JP, Cohn RD, Nishino I, Campbell KP. Nat Med. 2004;10:696–703. doi: 10.1038/nm1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Esko JD, Selleck SB. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;71:435–471. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kanagawa M, Saito F, Kunz S, Yoshida-Moriguchi T, Barresi R, Kobayashi YM, Muschler J, Dumanski JP, Michele DE, Oldstone MBA, Campbell KP. Cell. 2004;117:953–964. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuntz S, Sevilla N, McGavern DB, Campbell KP, Oldstone MBA. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:301–310. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xia B, Martin PT. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;19:539–551. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh J, Itahana Y, Knight-Krajewski S, Kanagawa M, Campbell KP, Bissel MJ, Muschler J. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6152–6159. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matsumoto H, Noguchi S, Sugie K, Ogawa M, Murayama K, Hayashi YK, Nishino I. J Biochem. 2004;135:709–712. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Esapa CT, Benson MA, Schroder JE, Martin-Rendon E, Brockington M, Brown SC, Muntoni F, Kroger S, Blake DJ. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:3319–3331. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.26.3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nguyen HH, Jayasinha V, Xia B, Hoyte K, Martin PT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5616–5621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082613599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith PL, Lowe JB. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15162–15171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lefrancois L, Bevan MJ. J Immunol. 1985;135:567–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hoyte K, Kang C, Martin PT. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;109:146–160. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00551-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sanes JR, Cheney JM. Nature. 1982;300:646–647. doi: 10.1038/300646a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martin PT. J Neurocytol. 2003;32:915–929. doi: 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000020632.41508.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]