Abstract

We investigated the potential for gene flow in a dependent lineage (DL) system of the harvester ant Pogonomyrmex. Each DL system is composed of 2 reproductively isolated lineages that are locked in an obligate mutualism. The genetic components that produce the worker phenotype are acquired by hybridizing with the partner lineage. In the mating flight, queens of both lineages mate with multiple males from each lineage. During colony growth and reproduction, eggs fertilized by partner-lineage sperm produce F1 hybrid workers with interlineage genomes, whereas eggs fertilized by same-lineage sperm result in the development of new queens with intralineage genomes. New males are typically produced from unfertilized eggs laid by the pure-lineage queen but in her absence may be produced by interlineage F1 workers. We investigated the potential for interlineage gene flow in this system using 2 classes of lineage-specific nuclear markers to identify hybrid genome combinations. We confirmed the production of viable interlineage F1 reproductive females in field colonies, the occurrence of which is associated with the relative frequencies of each lineage in the population: interlineage F1 queens occurred only in the rare lineage of the population with dramatically skewed lineage frequencies. In laboratory colonies, we detected fair meiosis in interlineage F1 workers leading to the production of viable and haploid interlineage F2 males. We conclude that the genomes of each lineage recombine freely, suggesting that extrinsic postzygotic selection maintains the integrity of each lineage genome. We compare our findings with those of the H1/H2 DL system.

Keywords: gene flow, Pogonomyrmex, postzygotic selection, reproductive isolation, symmetrical social hybridogenesis, worker-produced males

Ant colonies possess a reproductive division of labor wherein one or a few individuals produce offspring (queens), but most individuals are nonreproductive helpers (workers) that perform other tasks vital to colony growth and survival (Hölldobler and Wilson 1990). Whether an individual develops as a new unfertilized queen (gyne) or a worker is known as reproductive caste determination. The historical understanding of this developmental process emphasized the influence of environmental rather than genetic factors (Michener 1974; Wheeler 1986). Probably the best known example comes from honeybees where larvae fed an excess of royal jelly develop as queen phenotypes regardless of genotype. Recently, however, molecular methods have revealed that caste determination in many social insects is a complex phenotype, likely influenced by multiple interacting genetic and environmental factors. In the extreme case, the expression of the reproductive caste can be determined strictly according to genotype (see Anderson, Linksvayer, and Smith 2008 for a review).

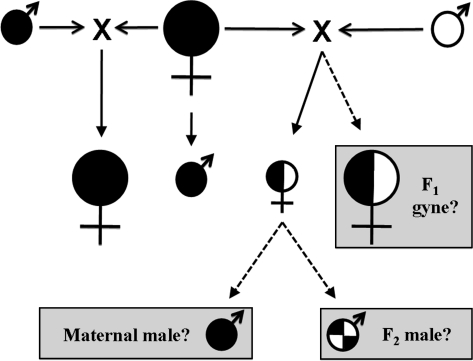

Although the genetic factors that underlie caste determination in ants are just beginning to be explored (Anderson, Novak, and Smith 2008; Feldhaar et al. 2008; Hughes and Boomsma 2008; Smith et al. 2008), one key study on Pogonomyrmex seed-harvester ants reveals that the interaction between maternal and paternal genomes can have a significant influence on whether an individual develops as a queen or a worker (Schwander and Keller 2008). In fact, certain populations of Pogonomyrmex barbatus and Pogonomyrmex rugosus may represent one extreme evolutionary result of genome interactions mediating caste determination. Here, individuals develop as gyne or worker phenotypes based almost entirely on diploid genome combinations (Helms Cahan et al. 2002; Julian et al. 2002; Volny and Gordon 2002b). These populations are termed dependent lineage (DL) systems (Anderson, Gadau, et al. 2006) because each “population” is actually composed of 2 reproductively isolated and perpetually hybridizing lineages that obligately co-occur at a site. Each lineage is unable to produce workers independent of its partner lineage (Helms Cahan et al. 2004). Mating is synchronized between the 2 lineages, and gynes mate randomly, often acquiring sperm stores from multiple males of each lineage. Eggs fertilized with interlineage sperm generate the interlineage F1 worker phenotype, eggs fertilized with intralineage sperm result in new gynes, and new males are produced from unfertilized (haploid) eggs produced by the pure-lineage queen (Figure 1). Thus, multiple mating by the queen is obligate for DL system persistence because producing the next generation of reproductive forms requires that the colony first produce a large number of interlineage F1 workers. There are 2 DL pairs; H1/H2, with the morphology of P. rugosus, and J1/J2, with the morphology of P. barbatus (Helms Cahan and Keller 2003).

Figure 1.

Mating structure representing one-half of a DL system. Black indicates the genome of lineage 1 and white is lineage 2. Large female symbols are reproductive females (gynes), small female symbols are functionally sterile workers, and small male symbols are reproductive males. Solid arrows represent the parental crosses and offspring that are typical of the DL system. Dashed arrows and gray boxes denote the potential for interlineage reproductive offspring. F1 interlineage workers are functionally sterile in the presence of the queen but in her absence can produce males via parthenogenesis. If problems with chromosome pairing occur during meiosis, males may inherit only the maternal or paternal genome, but if meiosis is fair, males will inherit genetic material in relatively equal proportions from both the matriline and patriline (interlineage F2 male).

In DL systems, the expression of the worker phenotype is thought to be caused by allelic interactions between the genomes of each lineage, whereas the expression of the queen phenotype is hardwired within each lineage (Helms Cahan and Keller 2003; Linksvayer et al. 2006). Because the caste determining genetic factors appear rigidly fixed within each lineage, gene flow between the interacting lineages could interfere with the allelic interactions that govern reproductive caste determination via any mechanism that allows independent assortment or recombination of homologous chromosomes between the haploid genomes of each lineage (Figure 1). If interlineage F1 gynes are produced, they could mate with pure-lineage males, potentially resulting in reproductive forms with introgressed genomes. Additionally, workers in most eusocial Hymenoptera still retain functional ovaries, and in the absence of the queen will often reproduce via arrhenotokous parthenogenesis in which unfertilized haploid eggs develop into males (Lin and Michener 1972). In this study, we explore the potential for gene flow between lineage J1 and lineage J2 by documenting the production of interlineage F1 gynes and the potential for male production by interlineage F1 workers. Such males also provide an opportunity to determine whether chromosomes of the different lineages pair up accurately and undergo fair meiosis in interlineage F1 workers. Meiosis is considered “fair” if independent assortment of chromosomes and/or crossing over between homologous chromosomes occurs between the 2 lineage haploid genomes, such that alleles diagnostic for each lineage are detected in interlineage F2 individuals in relatively equal proportions. In the extreme case, meiosis in interlineage F1 workers may eliminate either the male or female genome resulting in a pure-lineage male rather than an interlineage F2 recombined genome (Figure 1).

Materials and Methods

Males Produced by F1 Workers

We used laboratory colonies of the J1/J2 lineage pair to observe the potential for interlineage F2 male production by interlineage F1 workers and to investigate the cytological mechanism that underlies parthenogenetic male production. Laboratory colonies were grown from founding queens collected near Scottsdale, (33°31′N, 111°53′W; 386 m) or Sahuarita, Arizona, USA (31°57′N, 110°57′W; 824 m). Colonies were raised at 30 °C and fed cockroaches and Kentucky bluegrass seeds. Water was provided in test tubes to maintain humidity. After 1.5 years of colony growth, we induced male production by removing queens and their developing offspring from 11 colonies that were still productive and possessed at least 40 workers (hereafter referred to as “queen-less” colonies). As a control, we monitored male production in 23 colonies that possessed a fecund queen and at least 40 workers (queen-right colonies). Colonies were observed for male production over a period of 4 months.

We predict that the inability of the 2 genomes to pair accurately during meiosis is responsible for the apparent lack of introgressed forms in the J1/J2 lineage pair (Schwander et al. 2007; Suni et al. 2007). To this end, we used microsatellites to genotype one laboratory colony of each maternal lineage including the previously removed queen, interlineage F1 workers, and interlineage F1 worker-produced males (interlineage F2 males). In the colony headed by a lineage J1 queen, we genotyped 26 workers and 21 males, and in the colony headed by a lineage J2 queen, we genotyped 20 workers and 18 males. We amplified 3 informative microsatellite loci for each individual: Po8 (Wiernasz et al. 2004), Pb5 (Volny and Gordon 2002a), and Pr-1 (Gadau et al. 2003), according to the procedure described in Smith et al. (2008). We identified paternal alleles harbored in interlineage F1 workers by comparing the genotypes of F1 workers to that of their queen using the program matesoft (Moilanen et al. 2004). We then pooled all informative maternal and paternal alleles to examine independent assortment in interlineage F1 workers. If the genomes of each lineage do not pair up accurately during gametogenesis in F1 workers, then the alleles inherited by F2 males are predicted to assort nonindependently, and in the extreme case, worker-produced males may completely lack maternal or paternal alleles. At each locus, we performed a Chi-square test of independence. Because unlinked loci are an assumption of these analyses, we first tested for linkage between the 3 microsatellite loci by analyzing the inheritance of alleles in worker-produced males using the program genepop (Raymond and Rousset 1995).

F1 Gyne Development

In a different DL system (H1/H2), interlineage F1 gynes develop primarily in colonies headed by queens which have apparently mated only with males of the partner lineage (Helms Cahan et al. 2002; Helms Cahan and Keller 2003; Schwander et al. 2007; Anderson, Linksvayer, and Smith 2008; Anderson et al. 2009). Because mating is random, queens from a lineage at low frequency (a rare lineage) are more likely to acquire exclusively common (partner) lineage sperm, and thus be incapable of interlineage F1 gyne production (Anderson, Hölldobler, et al. 2006; Schwander et al. 2007; Anderson et al. 2009). Interestingly, it appears that in the absence of competition with intralineage brood, a small number of interlineage F1 (H1/H2) eggs can develop as fertile gynes, which later mate with pure-lineage males to produce colonies composed of backcrossed (B1) workers (Schwander et al. 2007). Based on these findings, we predict that interlineage F1 gynes may also occur in the J1/J2 system and that their frequency should also increase with lineage rarity.

We estimated the frequency of interlineage F1 gyne development in the J1/J2 lineage pair by sampling virgin queens (gynes) from field colonies during the reproductive season. Just prior to the yearly mating flights, we sampled 4–8 gynes from each of 75 colonies for a total of 346 individuals. Gynes were sampled at 2 different sites in Arizona (see Anderson et al. 2009); From Sahuarita, (31°57′N, 110°57′W; 824 m), we sampled 39 colonies where the relative frequency of each lineage is approximately equal (J1 = 0.46, J2 = 0.54), and from Queen Creek Road, (33°15′N, 111°58′W; 352 m), we sampled 36 colonies where relative lineage frequency is very unequal (J1 = 0.19, J2 = 0.81).

We used 2 different lineage-specific nuclear markers to detect the production of interlineage F1 gynes sampled from field colonies. For the Queen Creek Road population, we genotyped individuals at the Phosphoglucose isomerase allozyme locus according to the methods of Anderson, Gadau, et al. (2006). At this locus, each lineage is fixed at a single allele such that heterozygosity indicates an interlineage F1 genome (Helms Cahan et al. 2002, 2004; Anderson, Gadau, et al. 2006; Anderson, Hölldobler, et al. 2006). In the Sahuarita population, we used the Myrt3 (Evans 1993) microsatellite locus. In the J1/J2 lineage pair, there are 4 alleles at this locus, one is fixed in lineage J2 and the other 3 alleles occur at varying frequency in lineage J1 (Volny and Gordon 2002b; Clark et al. 2006; Schwander et al. 2007). Thus gynes are of interlineage ancestry if they are heterozygous at this locus and also possess the single allele diagnostic for lineage J2.

Reproductive Morphology

We compared the reproductive systems of nonhybrid (queen-produced) males with those of interlineage F2 hybrid (worker-produced) male offspring. We also examined the effect of queen removal on the reproductive development of interlineage F1 workers. Reproductive organs were stained with methyl blue and observed in 5% NaCl solution under ×25 magnification. In males, we examined the accessory glands, seminal vesicles, and testis for abnormalities. In workers, we examined ovariole number and the opacity of oocytes as an indicator of vitellogenin uptake, a protein precursor linked to reproductive potential in the Hymenoptera (Martinez and Wheeler 1991) Four months after queen removal, interlineage F1 workers from one queen-right colony and one queen-less and male-producing colony were examined for ovariole development. For worker comparisons, we recorded the number of oocytes and the presence/absence of opaque oocytes. The number of oocytes was compared using a t-test, and the presence of opaque oocytes was compared with a Chi-square test.

Results

Fair Meiosis in Interlineage F1 Workers Produces Interlineage F2 Males

Over a 6-month time period, no males were produced in 23 queen-right colonies, whereas male production occurred in 7 of 11 queen-less colonies (Fisher's Exact test, 2-tailed P = 0.001). Two of the male-producing colonies had been headed previously by J1 queens and 5 by J2 queens. From one male-producing colony of each lineage, we genotyped the queen, interlineage F1 workers, and worker-produced inter-lineage F2 males at 3 microsatellite loci. According to the program implemented in Genepop, none of the 3 loci showed linkage disequilibrium in worker-produced males of either maternal lineage. Three patrilines were deduced in the 26 analyzed interlineage F1 workers of maternal lineage J1, and 4 patrilines were deduced in 20 interlineage F1 workers of maternal lineage J2 (Table 1). Typical for lineage-specific alleles in the DL system (Helms Cahan and Keller 2003; Schwander et al. 2007; Suni et al. 2007), worker genotypes at the Pr1 locus were heterozygous (385/397) for all interlineage F1 workers of both maternal lineages, whereas the queens’ genotypes were homozygous (385/385 for lineage J1 and 397/397 for lineage J2). Similarly, at the Pb5 locus, queens from colonies of both lineages were homozygous (233/233) but all interlineage F1 worker offspring were heterozygous, inheriting alleles from 1 of 3 (maternal lineage J1) or 4 (maternal lineage J2) distinct fathers. Analysis based on all 3 loci indicates that fair meiosis occurs between the genomes of each lineage as both paternal and maternal alleles were present at statistically equal proportions in the interlineage F2 males resulting from parthenogenesis in interlineage F1 workers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Genotypes of colony members headed by queens of lineage J1 and J2

| Pata | Po8 locus | Pr1 locus | Pb5 locus | |

| Colony headed by J1 queen | ||||

| Lineage J1 matriline genotype | 241/247 | 385/385 | 233/233 | |

| Lineage J2 patriline genotypes (3 patrilines deduced from n = 26 workers) | 1 | 241 | 397 | 223 |

| 2 | 241 | 397 | 225 | |

| 3 | 241 | 397 | 229 | |

| Source of alleles in F2 males produced by F1 workers (M/P)b | — | 11/8 | 9/8 | |

| Chi square (1 df)/P value | — | 0.45/0.50 | 0.03/0.86 | |

| Colony headed by J2 queen | ||||

| Lineage J2 matriline genotype | 241/244 | 397/397 | 233/233 | |

| Lineage J1 patriline genotypes (4 patrilines deduced from n = 20 workers) | 1 | 238 | 385 | 235 |

| 2 | 250 | 385 | 235 | |

| 3 | 238 | 385 | 237 | |

| 4 | 250 | 385 | 243 | |

| Source of alleles in F2 males produced by F1 workers (M/P)b | 7/11 | 13/5 | 9/8 | |

| Chi square (1 df)/P value | 0.89/0.35 | 3.56/0.06 | 0.05/0.81 | |

The Chi-Square test examines the inheritance of maternal versus paternal alleles from interlineage F1 workers to interlineage F2 males.

Patriline designation.

Matriline/Patriline.

Interlineage F1 Gynes Occur in Field Colonies

The production of interlineage gynes from larvae that typically become workers occurs only in rare circumstances in the H1/H2 lineage pair (see Discussion). We documented the occurrence of interlineage gyne production in the J1/J2 lineage pair by examining diagnostic nuclear loci from 2 populations. In the population with significantly unequal lineage frequencies (Queen Creek Road; J1 = 0.18, J2 = 0.82), interlineage F1 gynes occurred only in the rare lineage (J1), only in small numbers (one colony produced 3 and the other produced 4), and only in colonies with no intralineage gyne production. In the rare lineage, 7 of the 42 (17%) genotyped gynes were of interlineage F1 ancestry. From the same population, no interlineage F1 gynes were detected in 29 colonies of the common lineage J2 (n = 164 gynes). In the population with relatively equal lineage frequencies (Sauhuarita; J1 = 0.46, J2 = 0.54), we detected no interlineage F1 gynes from 39 sampled colonies (Lineage J1; n = 90 gynes from 18 colonies, Lineage J2; n = 92 gynes from 21 colonies).

Reproductive Potential and Morphology

Over the 6-month time period, a total of 87 males were produced by interlineage F1 workers from 7 of 11 dequeened laboratory colonies (mean ± standard error [SE]; 12.4 ± 2.4, N = 7). In the male-producing colonies, >90% of all males emerged from their pupal casings demonstrating the viability of interlineage F2 eggs produced by interlineage F1 workers. As measured by oocyte number, interlineage F1 workers from one randomly selected male-producing colony showed significantly greater reproductive development than did interlineage F1 workers from one queen-right colony (t-test, t75 = −5.5, P < 0.0001, mean ± SE; queen-right = 2.8 ± 0.38; N = 30, queen-less = 7.5 ± 0.65; N = 47). Furthermore, the presence of opaque oocytes was significantly greater in interlineage F1 workers of queen-less colonies (χ2 = 14.6, 1 degrees of freedom [df], P < 0.0001). The frequency of queen-less interlineage F1 workers (n = 47) possessing opaque oocytes was 0.64, compared with 0.17 for queen-right inter-lineage F1 workers (n = 30).

Each of the 21 dissected males produced by queen-less colonies contained at least 2 accessory glands, seminal vesicles, and testis. Reproductive organs of worker-produced males were compared with those of males from 3 different field colonies, all of which were likely queen-produced (see Suni et al. 2007). The reproductive organs from 17 of 21 laboratory-reared interlineage F2 males were indistinguishable from those of queen-produced (pure-lineage) males. On examination under ×400 magnification, sperm also appeared normal when compared with that of males produced by pure-lineage queens. Four interlineage F2 males exhibited reproductive deformities. One interlineage F2 male had 3 symmetric and robust testes. Deformities in the other 3 interlineage F2 males were confined to the accessory glands. In each case one accessory gland appeared normal, whereas the other had a growth-like (bulbous) projection.

Discussion

DL systems are obligate mutualisms occurring between 2 reproductively isolated lineages of ants. Intralineage genomes have lost the ability to develop as workers, such that a DL system can only persist if each lineage can acquire worker development genes harbored within the genome of its partner lineage. Caste determination (whether an individual develops as a queen or a worker) in this system is thought to be governed by genetic compatibility such that intralineage diploid genomes are hardwired to develop as reproductive females, whereas interlineage F1 genomes nearly always develop as nonreproductive workers (Helms Cahan and Keller 2003; Linksvayer et al. 2006; Schwander et al. 2008, Figure 1). Due to the rigid nature of this genome expression, gene flow between lineages mitigated by reproductive forms of mixed-lineage ancestry may interfere with the compatibility of caste development genes provided by each lineage, eroding the stability of the DL system (Linksvayer et al. 2006; Suni et al. 2007; Anderson, Linksvayer, and Smith 2008). The results of the present study show that both F1 and F2 interlineage genomes can develop as viable reproductive forms in the J1/J2 lineage pair, suggesting that extrinsic postzygotic selection on interlineage (introgressed) reproductive forms or their worker offspring may be an important mechanism for maintaining the genome compatibility necessary for the production of functional worker and reproductive castes in the J1/J2 system.

Our molecular results for the worker-produced interlineage F2 males are consistent with fair meiosis occurring between the genomes of lineage J1 and lineage J2 regardless of lineage maternity. This finding has major implications for earlier results wherein no worker-produced males were detected in 184 field colonies of the J1/J2 lineage pair (Suni et al. 2007). If meiosis is unfair in workers (i.e., classic hybridogenesis; Schultz 1969), then worker-produced males could possess the same molecular signature as males produced by the queen, and remain undetected (Figure 1). As seen with other well-studied Pogonomyrmex species (Smith et al. 2007; Anderson KE, personal observation), our results show that males are not produced by workers in queen-right colonies. Queen removal, however, activated the reproductive systems of interlineage F1 workers, resulting in a dramatic increase (4×) in the percentage of workers possessing opaque oocytes within a colony, an indicator of reproductive potential (Martinez and Wheeler 1991). Thus, the lack of worker-produced interlineage F2 males seen in field samples (Suni et al. 2007) is largely due to queen presence, rather than the lack of reproductive potential in interlineage F1 workers.

Less than 5% of J1/J2 colonies become queen-less each year (Gordon and Kulig 1998) and the timing of queen death may play an important role in determining whether worker-produced interlineage F2 males are fully developed at the time of the mating flight. Indeed, Suni et al. (2007) did not detect a single worker-produced male of 758 males sampled just prior to the mating flight. However, given that a mean of 12.4 males were produced by our laboratory colonies consisting of 20–40 workers, it is possible that a single large field colony (10 000 workers) could generate many hundreds of worker-produced interlineage F2 males which then participate in the mating flight, although such occurrences may be rare. Conversely, queens produce offspring using the sperm of many different males, and the vast majority of colony resources are allocated to functionally sterile worker production. Under these conditions, the rare cohort of worker-produced males may have little impact on the stability of a DL system because the gametes of such introgressed males may only be expressed in workers, and contribute little to the reproductive gene pool.

Extrinsic postzygotic selection limiting gene flow is also implicated in a different lineage pair (H1/H2) wherein interlineage F1 gynes are produced and then backcross with pure-lineage males (see Schwander et al. 2007). During the first few months of colony founding by the H1/H2 lineage pair under laboratory conditions, the production of interlineage B1 workers by interlineage F1 queens was significantly lower than the production of interlineage F1 workers by pure-lineage queens. Thus, although interlineage B1 workers are viable, most colonies headed by interlineage F1 queens may be unable to compete with the interlineage F1 workforce of neighboring colonies under field conditions and be selected out prior to reproduction. Indeed, none of the 267 sampled field colonies of H1/H2 contained genotypes that could be clearly attributed to interlineage B1 workers (Schwander et al. 2007). It was speculated by the same study that a different mechanism must restrict gene flow between lineage J1 and J2 because interlineage F1 gyne production was completely absent across 6 sampled populations of J1/J2 considering a total of 117 genotyped gynes (Schwander et al. 2007). The study further concluded that interlineage F1 gynes are absent in the J1/J2 lineage pair because they retain no environmentally mediated developmental plasticity, and thus the strict association between genotype and caste development in interlineage F1 individuals invariably produces workers. However, our results reveal that interlineage F1 gynes are produced by the J1/J2 lineage pair. Similar to the H1/H2 system (Helms Cahan et al. 2002; Schwander et al. 2007), F1 gynes of J1/J2 are produced only in very small numbers and only in colonies that lacked intralineage gynes. That interlineage F1 gynes are produced in both DL systems under identical circumstances strongly suggests that similar postzygotic mechanisms are at work in both systems.

In the present study, 2 J1/J2 populations were assayed for interlineage F1 gyne development, which occurred only in the population with very unequal lineage frequencies (J1 = 0.19/J2 = 0.81) and only in colonies of the rare (J1) lineage. This finding is again consistent with the conditions under which H1/H2 lineages produce interlineage F1 gynes (Schwander et al. 2007) and strongly suggests that the production of F1 interlineage gynes is associated with lineage rarity in both systems. This pattern occurs because the probability that queens of a particular lineage will randomly acquire intralineage (gyne-destined) sperm declines dramatically as that lineage becomes infrequent in the population (Anderson et al. 2009). Thus when relative lineage frequency is very unequal, it results in a severe deficit of gyne production in the rare lineage and increases the chance of sampling interlineage F1 gynes in field colonies. When no intralineage (gyne-destined) offspring are available for rearing, it appears that some diminutive portion of the interlineage F1 genomes can develop as gynes (Helms Cahan et al. 2002; Schwander et al. 2007). Thus the inability of the Schwander et al. (2007) study to detect interlineage F1 gynes in the J1/J2 system is likely an artifact of random sampling because apriori knowledge of relative lineage frequency appears to have great utility when attempting to detect a very small number of individuals in colonies of the rare lineage.

The mechanism allowing interlineage F1 genotypes to develop as gynes is unknown, but the process may involve a maternal effect on gyne production (Schwander et al. 2008) or workers preferentially nurturing certain interlineage F1 genotypes (Clark et al. 2006). It is possible that the majority of interlineage F1 genotypes do not possess the genetic basis to respond to the maternal hormone signal, and may simply mature as workers, or abort gyne development as a result of developmental failure (Anderson et al. 2009).

Our results cannot reject the hypothesis that the J1/J2 lineage pair produces fewer interlineage F1 gynes than the H1/H2 lineage pair, a difference that may be due to the relative age of each system (Anderson, Gadau, et al. 2006) or to historical gene flow among the lineages which could preserve some degree of interlocus communication for genes that determine the reproductive caste (Schwander et al. 2007). Lineages H1 and H2 from neighboring populations can share identical mitochondrial haplotypes suggesting relatively recent horizontal gene flow has occurred between this lineage pair (Schwander et al. 2007). On the other hand, mitochondrial sequences between lineages J1 and J2 differ by as much as 8% and similar mitochondrial haplotypes are never found in the alternate lineage (Helms Cahan and Keller 2003; Anderson, Gadau, et al. 2006; Schwander et al. 2007). It is possible that the age of each DL system reflects the relative strength of the extrinsic postzygotic barriers inhibiting gene flow between the lineages. By some estimates, the J1/J2 lineage system is older than the H1/H2 system and thus has had more time to accrue genetic differences that may further reduce compatibility between the lineages at caste loci resulting in decreased interlineage F1 gyne production and decreased opportunity for gene flow (Anderson, Linksvayer, and Smith 2008).

Funding

National Institutes of Health—Institutional Research and Academic Career Development Award (5K-12-GM000708 to K.E.A.).

Acknowledgments

We thank Norman Buck and Sebastian Zeltzer for laboratory assistance and constructive discussion.

References

- Anderson KE, Gadau J, Morr BM, Johnson RA, Altamirano A, Strehl C, Fewell JF. Distribution and evolution of genetic caste determination in Pogonomyrmex seed-harvester ants. Ecology. 2006;87:2171–2184. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[2171:daeogc]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KE, Hölldobler B, Fewell JH, Mott BM, Gadau J. Population-wide lineage frequencies predict genetic load in the seed-harvester ant Pogonomyrmex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13433–13438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606055103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KE, Linksvayer TA, Smith CR. The causes and consequences of genetic caste determination in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Myrmecol News. 2008;11:119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KE, Novak SJ, Smith JF. Populations composed entirely of hybrid colonies: bidirectional hybridization and polyandry in harvester ants. Biol J Linn Soc. 2008;95:320–336. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KE, Smith CR, Linksvayer TA, Mott BM, Gadau J, Fewell JH Forthcoming. Modeling the maintenance of a dependent lineage system: the influence of positive frequency dependent selection on sex ratio. Evolution. 2009;63:2142–2152. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RM, Anderson KE, Gadau J, Fewell JH. Behavioral regulation of genetic caste determination in a Pogonomyrmex population with dependent lineages. Ecology. 2006;87:2201–2206. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[2201:brogcd]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JD. Parentage analyses in ant colonies using simple sequence repeat loci. Mol Ecol. 1993;2:393–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1993.tb00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldhaar H, Foitzik S, Heinze J. Lifelong commitment to the wrong partner: hybridization in ants. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2008;363:2891–2899. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadau J, Strehl CP, Oettler J, Hölldobler B. Determinants of intracolonial relatedness in Pogonomyrmex rugosus (Hymenoptera; Formicidae): mating frequency and brood raids. Mol Ecol. 2003;12:1931–1938. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon DM, Kulig AW. The effect of neighbors on the mortality of harvester ant colonies. J Anim Ecol. 1998;67:141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Helms Cahan S, Julian GE, Rissing SW, Schwander T, Parker JD, Keller L. Loss of phenotypic plasticity generates genotype-caste association in harvester ants. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2277–2282. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms Cahan S, Keller L. Complex hybrid origin of genetic caste determination in harvester ants. Nature. 2003;424:306–309. doi: 10.1038/nature01744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms Cahan S, Parker JD, Rissing SW, Johnson RA, Polony TS, Weiser MD, Smith DR. Extreme genetic differences between queens and workers in hybridizing Pogonomyrmex harvester ants. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;269:1871–1877. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölldobler B, Wilson EO. The ants. 1st ed. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes WOH, Boomsma JJ. Genetic royal cheats in leaf-cutting ant societies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5150–5153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710262105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian GE, Fewell JH, Gadau J, Johnson RA, Larrabee D. Genetic determination of the queen caste in an ant hybrid zone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8157–8160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112222099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N, Michener CD. Evolution of sociality in insects. Q Rev Biol. 1972;47:131–159. [Google Scholar]

- Linksvayer TA, Wade MJ, Gordon DM. Genetic caste determination in harvester ant: possible origin and maintenance by cyto-nuclear interactions. Ecology. 2006;87:2185–2193. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[2185:gcdiha]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez T, Wheeler DE. Identification of vitellogenin in the ant, Camponotus festinatus: changes in hemolymph proteins and fat body development in workers. Arch Int Physiol Biochim. 1991;17:143–155. doi: 10.1002/arch.940170208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michener CD. The social behavior of the bees: a comparative study. Cambridge (MA): Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1974. p. 404. [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen A, Sundström L, Pedersen JS. MateSoft: a program for deducing parental genotypes and estimating mating system statistics in haplodiploid species. Mol Ecol Notes. 2004;4:795–797. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond M, Rousset F. Genepop (version 1.2): population genetics software for exact tests and ecumenicism. J Heredity. 1995;86:248–249. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz RJ. Hybridization, unisexuality, and polyploidy in the teleost Poeciliopsis (Poeciliidae) and other vertebrates. Am Nat. 1969;103:606–619. [Google Scholar]

- Schwander T, Humbert J, Brent CS, Helms Cahan S, Chapuis L, Renai E, Keller L. Maternal effect on female caste determination in a social insect. Curr Biol. 2008;18:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwander T, Keller L. Genetic compatibility affects queen and worker caste determination. Science. 2008;322:552. doi: 10.1126/science.1162590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwander T, Keller L, Helms Cahan S. Two alternate mechanisms contribute to the persistence of interdependent lineages in Pogonomyrmex harvester ants. Mol Ecol. 2007;16:3533–3543. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CR, Anderson KE, Tillberg CV, Gadau J, Suarez AV. Caste determination in a polymorphic social insect: nutritional, social, and genetic factors. Am Nat. 2008;172:497–507. doi: 10.1086/590961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CR, Schoenick C, Anderson KE, Gadau J, Suarez AV. Potential and actual reproduction by different worker castes in queen-less and queen-right colonies of Pogonomyrmex badius. Insectes Soc. 2007;54:260–267. [Google Scholar]

- Suni SS, Gignoux C, Gordon DM. Male parentage in dependent-lineage populations of the harvester ant Pogonomyrmex barbatus. Mol Ecol. 2007;16:5149–5155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volny VP, Gordon DM. Characterization of the polymorphic microsatellite loci in the red harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex barbatus. Mol Ecol Notes. 2002a;2:302–303. [Google Scholar]

- Volny VP, Gordon DM. Genetic basis for queen-worker dimorphism in a social insect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002b;99:6108–6111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092066699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DE. Developmental and physiological determinants of caste in social hymenoptera: evolutionary implications. Am Nat. 1986;128:13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wiernasz DC, Perroni CL, Cole BJ. Polyandry and fitness in the western harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex occidentalis. Mol Ecol. 2004;13:1601–1606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]