Abstract

Small GTPase RHEB binds and activates the key metabolic regulator mTORC1, which has an important role in cancer cells, but the role of RHEB in cancer pathogenesis has not been demonstrated. By performing a meta-analysis of published cancer cytogenetic and transcriptome databases, we defined a gain of chromosome 7q36.1-q36.3 containing the RHEB locus; an overexpression of RHEB mRNA in several different carcinoma histotypes; and an association between RHEB upregulation and poor prognosis in breast and head and neck cancers. To model gain-of-function in epithelial malignancy, we targeted Rheb expression to murine basal keratinocytes of transgenic mice at levels similar to those that occur in human squamous cancer cell lines. Juvenile transgenic epidermis displayed constitutive mTORC1 pathway activation, elevated cyclin D1 protein, and diffuse skin hyperplasia. Skin tumors subsequently developed with concomitant stromal angio-inflammatory foci, evidencing induction of an epidermal HIF-1 transcriptional program, and paracrine feed-forward activation of the IL6-STAT3 pathway. Rheb-induced tumor persistence and neoplastic molecular alterations were mTORC1-dependent. Rheb markedly sensitized transgenic epidermis to squamous carcinoma induction following a single dose of ras-activating carcinogen DMBA. Our findings offer direct evidence that RHEB facilitates multistage carcinogenesis through induction of multiple oncogenic mechanisms, perhaps contributing to the poor prognosis of patients with cancers overexpressing RHEB.

Keywords: RHEB, mTORC1, tumorigenesis

Introduction

The pathway integrating diverse mammalian cell growth signals engages the heterotrimeric protein kinase mTORC1, which, when induced, stimulates growth by promoting ribosomal biogenesis and protein synthesis through effectors p70S6K and eIF-4E-BP (1–3). Growth pathways converge on the negative regulator of mTORC1, tuberous sclerosis complex 1/2 (TSC1/2). As a GTPase activating protein (GAP) toward the small G protein Ras homolog enriched in brain (RHEB), TSC1/2 inhibits RHEB function. GTP-bound RHEB is a direct mTORC1 activator, which is essential for cell growth in Drosophila and mammalian cells (3–5). Growth factor receptor activation triggers the PI3K/AKT cascade stimulating mTORC1 by repressing TSC1/2, whereas a sufficiency of cellular energy (i.e. high ATP/ADP ratio) suppresses LKB1 and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling, which inhibits mTORC1 by activating TSC1/2. Both growth factor, bioenergetic, and nutrient pathways also regulate mTORC1 through TSC1/2-independent mechanisms (6–8).

MTORC1 hyperactivation occurs in most human cancers via PI3K/AKT signaling, which is induced by either mutation or amplification of genes encoding growth factor receptors, the PI3K catalytic subunit (PIK3CA), or AKT; or loss of function of pathway negative regulators including the tumor suppressors NF1, PTEN, and TSC1/2 (3–5). Dysregulated mTORC1 signaling is present in the tumor-prone Peutz-Jeghers syndrome due to LKB1 inactivating mutations and in human colorectal cancers with APC loss of function (9; and reference therein). Many pre-clinical studies demonstrate that mTORC1 blockade by rapamycin and its derivatives is anti-neoplastic in lesions induced by a variety of oncogenic signaling inputs, suggesting that mTORC1 is a relevant common effector of cancer development (9–14).

RHEB cytogenetic and expression data are limited in human cancers. Unlike other mTORC1 upstream genes, RHEB or mTOR mutations have not been discovered (15, 16). RHEB is located on chromosome 7q36. A recent study showed low-frequency whole chromosome 7 amplification in a cohort of CGH-analyzed human prostate cancers (17), however, RHEB locus amplification or association between RHEB expression and human cancer prognosis has not been investigated. Recently, two animal studies demonstrated that Rheb gain-of-function was tumorigenic. Rheb overexpression enhanced Eμ-Myc-mediated lymphomagenesis in a mouse bone marrow transplantation model (18), and produced low-grade prostatic intra-epithelial hyperplasia (17). However, the lymphoma model did not test Rheb tumorigenicity as a monogenetic perturbation, and the nature of a secondary cooperating hit responsible for the long latency and low penetrance of Rheb-mediated prostatic hyperproliferation was not elucidated. Thus, despite progress, important questions remain regarding RHEB expression and function in tumorigenesis.

Here, we demonstrate RHEB overexpression and chromosomal locus amplification in a broad spectrum of human cancers and prognostic association in breast and head and neck squamous cancer. Using a transgenic mouse model of Rheb overexpression and mTORC1 hyperactivation in skin epidermis recapitulating RHEB expression in human cancer cells, we show that Rheb gain-of-function facilitates cancer progression through multiple mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Cancer transcriptome database mining

We queried Oncomine and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) listing all datasets containing RHEB expression data, and downloaded those trending toward differential expression between cancers and normal tissues or between cancer types/grades. Unpaired two-tailed t-tests determined statistical significance associated with differential expression (p<0.05). This analysis identified the Oncomine Chen_Liver cancer (normal vs. cancer), Blaveri_Bladder_2 cancer (low-grade vs. high-grade), Chung_Head and neck cancer (normal vs. cancer), and GEO GDS1650 Lung adenocarcinoma (normal vs. cancer) datasets. The Mann Whitney U-test was used to determine high-RHEB-expressing outliers in stage-3 versus stage-1 breast cancers from the Oncomine vantVeer Breast cancer cohort. A second breast cancer dataset, Oncomine Minn_Breast_2 cancer, was analyzed as validation for the vantVeer_Breast cancer set. The two breast and one head-and-neck cancer cohorts were further analyzed for correlation between cancer RHEB expression and clinical outcome. Specifically, each of the three cancer datasets were divided into quartiles based on RHEB mRNA levels, and a survival curves for the upper 25th (RHEB-Hi) versus the lower 25th quartiles were compared for the statistical significance using the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

Mouse experiments

Myc-mouse Rheb cDNA was cloned into a 2-kb fragment of human K14 promoter (19). The transgene was used for pronuclear microinjection of FVB/n embryos. A total of eight transgenic founders were generated, and two transmitted the transgene through the germline. In the chemoprevention trial, 8 week-old transgenic mice were treated with 10μg/g of RAD001 or vehicle (Novartis Corporation, Basel, Switzerland) by gavage once per week for 13–15 weeks. In the therapeutic trial, tumor-bearing mice between 15–25 weeks were treated with 7.5 μg/g RAD001 or vehicle three times per week for four weeks. For skin carcinogenesis, the back skin of 8 week-old mice was shaved and topically treated with a single dose of DMBA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 100 μg in acetone. The Animal Studies Committee of Washington University in St. Louis approved all animal work.

Histology, immunofluorescence, and immunohistochemistry

Tissues were obtained from 10% sucrose/10% formalin perfused mice, and microwave-processed (20), or immersed in zinc fixative (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for 24 hours. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (20). For immunofluorescence, rehydrated sections were blocked with Dako Protein Block (Dako North America, Carpinteria, CA). Antigen retrieval was performed in citrate- or EDTA-based buffer using a pressure cooker (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA). Primary and fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies were diluted in Dako antibody diluent. For immunohistochemical detection, sections were incubated with biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies followed by immunoperoxidase staining using Vectastain ABC Elite kit (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA), and diaminobenzidine (Dako North America). BrdU mouse pulse labeling and tissue immunostaining was performed as previously described (21). Antibodies used for immunostaining are listed in Supplemental Materials and Methods. The following antibodies used in immuno-staining were from Cell Signaling Technologies: rabbit antibodies against phsopho-S6 ribosomal proteinS235/236 (1:500), phospho-eIF-4GS1108 (1:100), phospho-RBS780 (1:100), Rheb (1:400), Myc-tag (1:500), activated caspase 3 (1:500), phospho-STAT3Y705 (1:50), survivin (1:100), phsopho-ERK1/2 T202/Y204 (1:100), and E-cadherin (1:200). Additional antibodies used were: rabbit anti-loricrin, anti-keratin 8, and anti-keratin 10 (1:500, 1:5000, and 1:50 respectively, Covance, Princeton, NJ), anti-cyclin D1 (1:100, Abcam), rat anti-CD45, anti-meca32, anti-CD4, anti-CD8a, anti-Gr-1 (1:50, 1:20, 1:20, 1:20, 1:20 respectively, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), anti-FoxP3 (1:200, eBioscience, San Diego, CA), anti-F4/80 (Serotec, Raleigh, NC) antibodies, and biotinylated mouse antibody against keratin 14 (1:1000, Lab Vision, Fremont, CA). For immunofluorescence, slides were incubated with corresponding fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:400, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). BrdU labeling was detected with Alexa Fluor 594-congujgated anti-BrdU antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Keratinocyte culture

Primary mouse keratinocytes were established from one day-old neonatal epidermis as described previously (21). For serum starvation, keratinocytes were cultured overnight in serum-free media. For mIL-6 stimulation, serum-starved keratinocytes were treated with 10ng/ml rmIL-6 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) for various durations of time.

Immunoblotting

Frozen tissues and pelleted cultured keratinocytes were lysed with ice-cold lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 40mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 120mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 10mM pyrophosphate, 10mM glycerophosphate, 50mM NaF, 0.5mM orthovanadate, and 1:50 diluted protease inhibitor cocktail [Sigma-Aldrich]). Protein sample preparation and immunoblotting were according to a standard procedure (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). Antibodies used for immunoblotting are listed in Supplemental Materials and Methods. The following antibodies were used in Western blotting (all at 1:1,000, and all from Cell Signaling Technology): anti-mTOR, anti-phospho-mTORS2448, anti-S6K1, anti-phospho-S6K1T389, anti-S6 ribosomal protein, anti-phospho-S6 ribosomal proteinS235/236, anti-eIF-4G, anti-phospho-eIF-4GS1108, anti-AKT, andti-phospho-AKTT308, anti-phospho-AKTS473, anti-JAK2, anti-phospho-JAK2Y1007/1008, anti-STAT3, anti-phospho-STAT3Y705, anti-phospho-STAT3S727, anti-RB, anti-phospho-RBS780, anti-Myc tag, anti-Rheb, anti-Bcl-xl, anti-eIF-4E, and anti-cyclin D1. We also used anti-β-tubulin (1:35,000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-keratin 14 (1:2000, Covance, Princeton, NJ), anti-HIF-1α (1:1,000, Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX), anti-VEGF (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-IL-6 (1:400, Abcam), and horseradish peroxidase (HPR)-conjugated IgG secondary antibodies (1:1000, Santa Cruz).

Quantitative Real-time RT PCR and ELISA

Total RNA was prepared from mouse back skin using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Messenger RNA expression was measured by real-time quantitative PCR using a TaqMan Gold PCR kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Cytokines in keratinocyte cell culture media supernatants and/or skin lysates were measured by ELISA according to manufacturer’s instructions (BD Biosciences).

Tissue Microarray Analysis

Cancer specimens were collected in the Department of General Surgery & Pathology, Hongqi Hospital, Mudanjiang Medical College, China. Specimens included: (a) stage I or II breast cancer (n = 74; 12 cases of ductal carcinoma in situ, and 62 cases of invasive ductal cancer). Normal breast tissue cores from 13 reduction mammoplasty patients from University of California San Diego Medical Center were included to the TMA. (b) Duke’s stage B colorectal cancer (n = 48; 31 also with normal colon from the same patient); and (c) stage T2N0M0 or T3N0M0 gastric cancer (n = 24; 16 also with adjacent normal stomach epithelium) assessed according to the International Union Against Cancer criteria (22). The research was approved by an institutional review board of the Mudanjiang Medical College, China, and University of California, San Diego. Tissue microarrays (TMAs) were previously described (23). Typically, two-to-three cancer cores and one adjacent normal tissue core were obtained from each specimen. In addition, normal tissue cores were also obtained from reduction mammoplasties as breast cancer TMA controls. Tissue core procurement details are provided in Supplementary Methods. TMA immunohistochemical analysis was performed as previously described (23). Rheb antibody (AB-2; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) or non-immune rabbit serum was applied at a 1:2,000 dilution (v/v), and a qualitative immunostaining scoring system (immunoscore) was used for RHEB expression quantification (24).

Reverse phase protein array (RPPA)

RHEB protein expression in a collection of human cancer cell lines was surveyed using high through-put reverse-phase protein assay (RPPA) as previously described (25). Briefly, the conditions of RHEB antibody (AB-2; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) usage were optimized for RHEB specificity by immunoblotting. Cell lysates prepared for immunoblotting were transferred to SDS sample buffer, incubated for 5 minutes at 95°C, and printed onto nitrocellulose-coated glass slides with an automated robotic GeneTac arrayer (Genomic Solutions, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI). The same stringent conditions for slide blocking, blotting, and antibody incubation, which were used for immunoblotting, were applied.

Statistical Methods

Data were presented as the mean +/− standard deviation, and statistical significance determined using the two-tailed unpaired Student t-, Mann Whitney U, or Chi Square tests (GraphPad Prism, San Diego, CA), and Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) analysis.

Results

RHEB dysregulation was a novel prognostic factor in human cancer

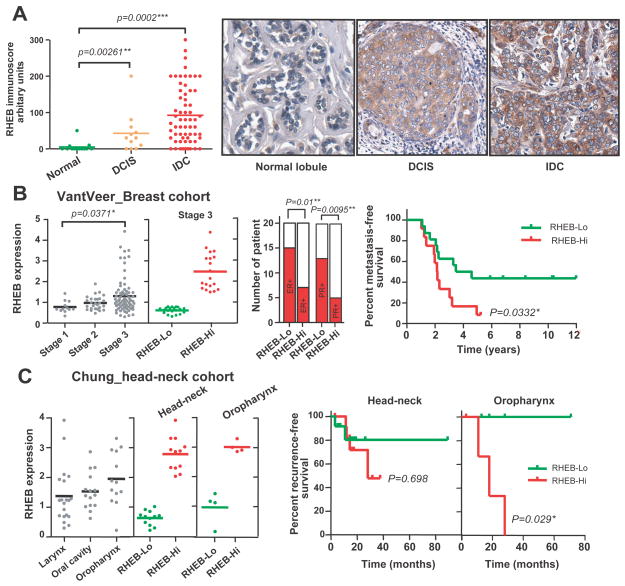

Interrogation of published human cancer cytogenetic data revealed frequent gain/amplification of a minimally overlapping chromosomal 7q36.1-q36.3 region harboring the RHEB locus in diverse human cancer histotypes (sTable I). Of 491 total cancer genomes, 45 (9.2%) contained gain of 7q32-qter or a smaller region. Amongst these genomes, 16 harbored gain of the 7q36 region. Analysis of cancer transcriptome databases (26, 27) uncovered increased RHEB expression in liver, lung, and bladder cancers (sFigure 1A). Differential RHEB protein elevation was evident in TMAs of stomach and colorectal adenocarcinomas compared to respective adjacent histologically normal mucosa (sFigure 1B). A striking incremental RHEB induction during breast carcinogenesis with moderate overexpression in ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS), followed by marked malignant epithelial protein expression in invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) was detected in a multi-stage breast TMA (Figure 1A). Microarray database mining confirmed a statistically significant association between high-level RHEB mRNA upregulation and breast cancer progression, most evident in Stage 3 disease, and more frequent in the aggressive ER− and/or PR− cases (Figure 1B) (28). Quartile analysis of Stage 3 cancers revealed that RHEB-High expression exhibited a worse metastasis-free survival compared to RHEB-Low Stage 3 counterparts (Figure 1B). Elevated RHEB expression in a second breast cancer cohort was independent of PTEN or HER2 expression, and was also significantly associated with either ERor PR negativity, and an increased frequency of metastasis (sFigure 1C, and data not shown). RHEB mRNA overexpression was also detected in head and neck (HN) cancer originating in several different sites of the oropharyngeal squamous mucosa (29) (Figure 1C). Quartile analysis revealed that the RHEB-Hi group possessed a trend for reduced recurrence-free survival versus the RHEB-Lo group (Figure 1C, middle panel). These data were independent of EGFR status (data not shown). Among HN cancer site-specific subtypes, RHEB-Hi oropharyngeal carcinomas had a worse disease outcome than RHEB-Lo counterparts (Figure 1C, right panel, p=0.029). Collectively, these data for the first time, suggested a functional linkage between RHEB overexpression and progression of human cancers originated from several different organ sites in general and squamous cancers in particular.

Figure 1. RHEB overexpression is associated with poor prognosis in several different human epithelial malignancies.

(A) Tissue microarray immunoscores for RHEB protein levels in normal breast tissues, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), and invasive ductal carcinomas (IDC). (B) Microarray RHEB mRNA level for stage 1–3 breast cancers, and quartile analysis of Stage-3 patients based on RHEB expression (“RHEB-High”, upper quartile, versus “RHEB-Low”, lower quartile). Distribution of ER+/ER−, PR+/PR− cases (middle panel) and Kaplan-Meier survival curve (right panel) in Stage-3 RHEB-Hi versus RHEB-Lo breast cancers. (C) RHEB expression in human head-and-neck cancer subtypes (left panel), the Kaplan-Meier recurrence-free survival curves for RHEB-Hi versus RHEB-Lo head-and-neck cancers (middle panel) and for RHEB-Hi versus RHEB-Lo oropharynx cancers (right panel). Statistical analyses: two-tailed unpaired t-tests (left panel 1A); Mann-Whitney test (left panel 1B); Chi-square tests (middle panel 1B); Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests (survival data in panels 1B and 1C).

Next, we surveyed RHEB expression in a collection of human cancer cell lines using high throughput reverse-phase protein assay (RPPA) (25). RHEB high-expressing subsets were identified amongst mammary (highest level compared with lowest level or Hi/Lo=7.7), lung (Hi/Lo=4.7), ovarian (Hi/Lo=6.1), and HN cell lines (Hi/Lo=4.4) (sFigure 2A). Analysis of human and mouse cancer cell lines by immunoblotting revealed that human SiHa and C33A, and mouse C5N squamous carcinomas exhibited the highest RHEB abundance, about 3.1- to 4.7-fold elevated compared to RHEB levels in wild-type mouse skin epidermis (sFigure 2B).

RHEB induced mTORC1 hyperactivation in transgenic epidermis and cultured keratinocytes resistant to serum and amino acid starvation

To develop a general model for studying RHEB overexpression in epithelial carcinogenesis, and a model of squamous carcinogenesis in particular, two independent transgenic mouse lines (K14-Rheb#8 and #4) were created targeting murine Rheb overexpression to basal epidermal keratinocytes. Epidermal RHEB expression was elevated four-fold in K14-Rheb#8 mice compared to wild-type littermate controls, matching expression in SiHa and C33A cell lines (sFigure 2B, RHEB versus WT). K14-Rheb#8 mice displayed phenotypes at full-penetrance, and were used for all studies in this report. K14-Rheb#4 mice expressed the Rheb transgene at endogenous levels (data not shown), and 10% developed skin pathology identical to line #8 counterparts.

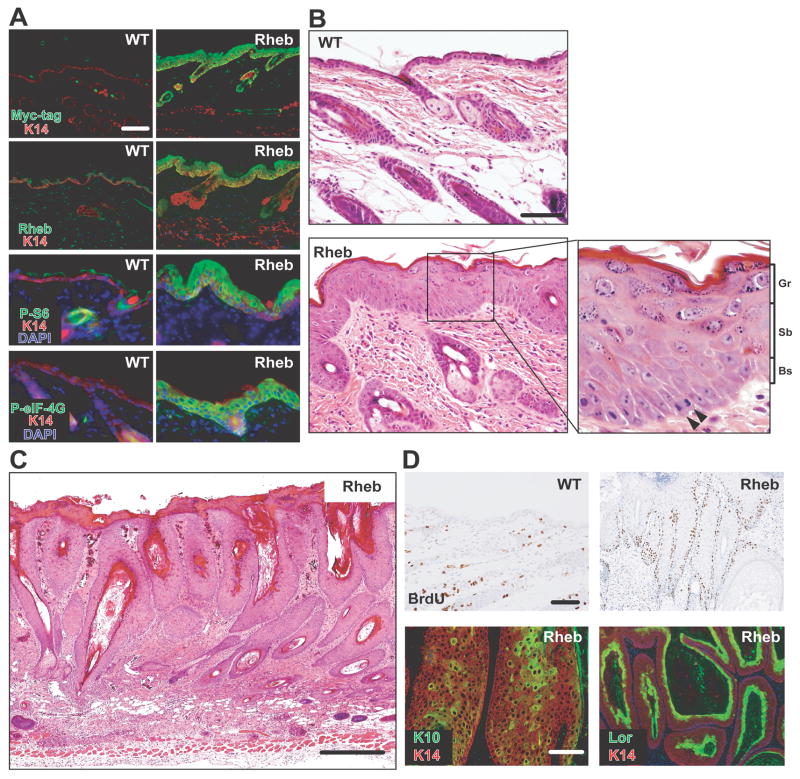

Immunoblotting revealed mTORC1 target activation (phospho-p70S6K1T389 and phospho-eIF-4GS1108) and elevated p70S6K1, S6, and eIF-4G expression in transgenic epidermal extracts compared with wild-type controls (sFigure 3A). The Myc-RHEB fusion protein, phospho-S6S235/236, and phospho-eIF-4GS1108 were markedly upregulated in the epidermal basal, suprabasal, and granular layers (Figure 2A, Myc-tag and RHEB), suggesting RHEB persistence accompanying epidermal differentiation. Neither phospho-AKTS473 (mTORC2 kinase site) nor phospho-AKTT308 levels (PDK1 kinase site) were differentially altered in transgenic epidermis (sFigure 3A). Serum-starved keratinocyte cultures derived from neonatal transgenic epidermis revealed persistently elevated mTORC1 signaling (sFigure 3B) but similar mTORC2 activity compared to wild type keratinocytes (sFigure 3C). These data suggested lack of S6K-mediated negative feedback in this model (30). MTORC1 activity was resistant to combined serum and amino acid starvation in transgenic keratinocytes, but completely repressed in controls (sFigure 3D).

Figure 2. Rheb induced mTORC1 hyperactivation and produced epidermal neoplasia.

(A) Expression of Myc-RHEB transgene, RHEB, pS6 and peIF-4G. (B) Histological analyses of 3 week-old wild-type (WT) and transgenic back skin (arrowhead: mitotic basal cell). Gr, Sb, Bs: granular, suprabasal, and basal layer. (C) Histology of a large transgenic back skin papilloma. (D) Analysis of proliferation in wild-type versus transgenic papilloma (upper panels) and epidermal differentiation in transgenic papillomas (lower panels). Bars (A, B upper panel, D): 100μm, (B lower panel): 50μm, (C): 200μm.

Juvenile epidermal hyperplasia and universal adult onset neoplasia in K14-Rheb transgenic mice

Neonatal transgenic mice exhibited wrinkled back skin, reddened tails and paws, and thickened ears (sFigure 4A–B). Histological analysis of 3-week old transgenic back skins revealed diffuse epidermal hyperplasia (sFigure 4C), and marked keratinocyte hypertrophy in all epidermal layers (Figure 2B). Spontaneous neoplasia first appeared in transgenic mice at 12 weeks of age, predominantly located on the posterior neck and between the shoulder blades, and reached 100% penetrance by 32 weeks of age (N=42; sFigure 4D). Tumor burden ranged from 1 to 20 (7.8 ± 5.3) per mouse. In contrast, none of the wild-type littermates (N=36) evidenced skin pathology. All transgenic tumors were benign, composed of hyperplastic hair follicles and hypertrophic sebaceous glands (Figure 2C). BrdU incorporation was elevated in the basal and immediate-suprabasal layers of hyperplasias and neoplasias (Figure 2D), and both pathologies retained cytokeratin 10 and loricrin expression (Figure 2D, K10 and Lor). Thus, monogenetic Rheb overexpression, while tumorigenic, did not dysregulate epithelial differentiation.

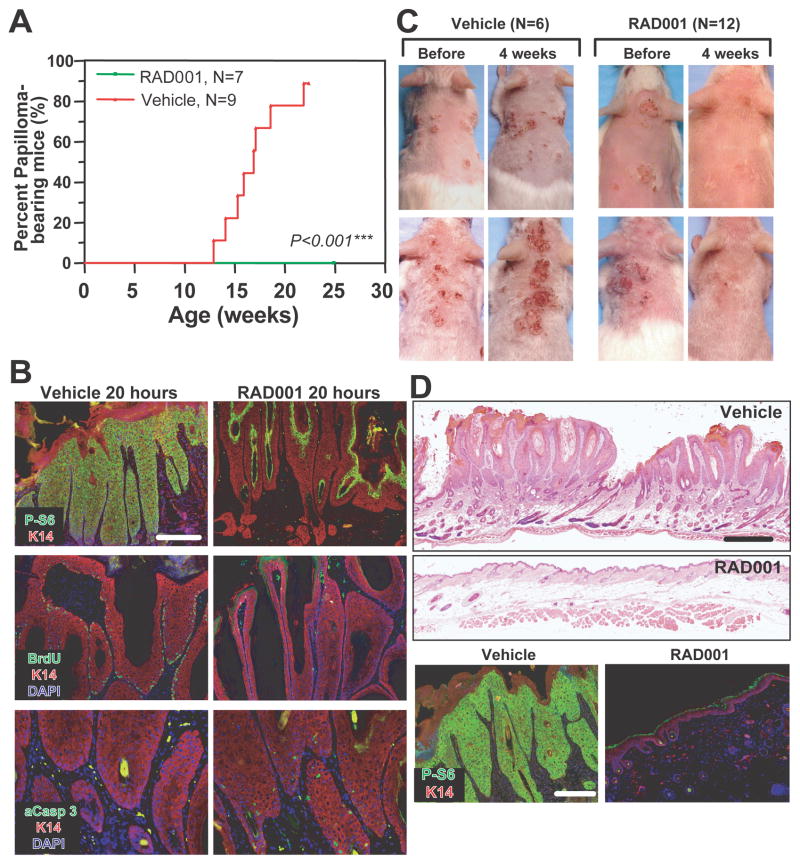

Formation or maintenance of Rheb-mediated epidermal neoplasia was mTORC1-dependent

To determine whether mTORC1 activity was required for Rheb-induced papilloma formation, 8- to 10-week-old transgenic mice were treated with the mTORC1 inhibitor RAD001 (everolimus), an orally bioavailable derivative of rapamycin, for 13 to 15 weeks. RAD001 completely prevented tumor formation, in contrast to an 88% incidence of neoplasia in vehicle-treated mice (Figure 3A). Specific inactivation of mTORC1 but not mTORC2 in back skin of RAD001-treated transgenic mice was confirmed by phospho-S6S235/236 (mTORC1 marker) and phospho-AKTS473 (canonical direct mTORC2 site) immunofluorescence, respectively (data not shown). Next, we tested whether established transgenic papillomas could be reversed by RAD001. RAD001 treatment for 20h inactivated mTORC1-mediated S6 phosphorylation in tumor basal and suprabasal cells, markedly decreased proliferation (BrdU), and induced apoptosis (activated caspase 3) (Figure 3B). Four weeks of inhibitor treatment produced a drastic visual (Figures 3C, RAD001, upper panel) and histological (Figures 3D, RAD001, 4w) resolution of all papillomas in six transgenic mice. The other six transgenic mice, which exhibited papilloma-associated ulceration, almost completely resolved both wounding and neoplastic pathologies after RAD001 treatment (Figure 3C, RAD001, lower panel). In contrast, papilloma number and size increased in vehicle-treated mice. Abrogation of ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation consequent to 4 week RAD001 treatment was consistent with potent mTORC1 inhibition in papilloma-bearing transgenic mice (Figure 3D, lower panel and data not shown).

Figure 3. Formation/maintenance of transgenic papilloma was mTORC1-dependent.

(A) Time course of papilloma appearance in K14-Rheb mice treated with vehicle or RAD001. (B) Rapid mMTORC1 activity inhibition concomitant with proliferation abrogation and apoptosis induction in RAD001-treated transgenic papillomas for 20 hours. (C) Papilloma regression in 4-week RAD001-treated transgenic mice. (D) Histological (upper panel) and mTORC1 target (lower panel) response to 4-week RAD001 treatment. Bars (B, lower panel D): 100μm, (upper panel D): 750μm.

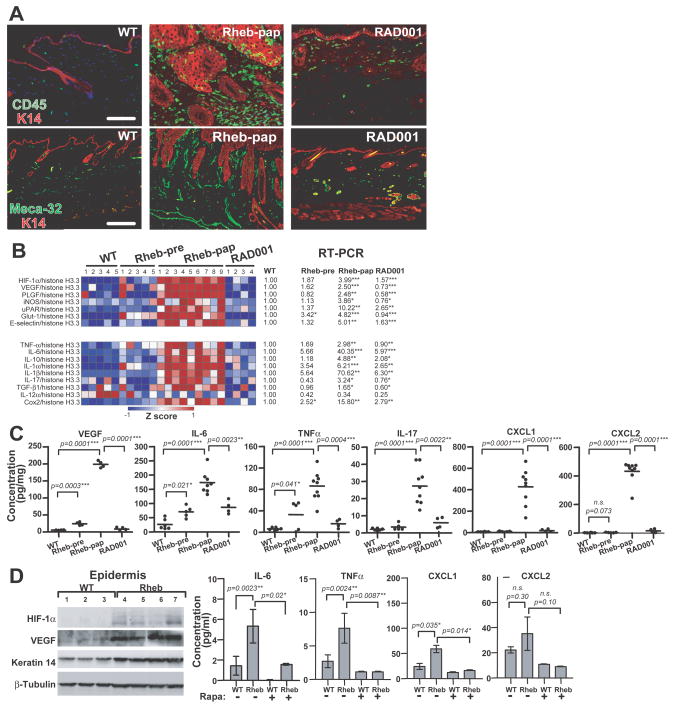

Rheb triggered an mTORC1-mediated angio-inflammatory switch in transgenic papillomas

As histological analysis revealed markedly increased stromal cellularity in transgenic papillomas, we determined their inflammatory cell repertoire and vasculature. Tumor stroma contained near confluent CD45+ cells and greatly increased blood vessel area and frequency (Figure 4A). The stromal CD45+ cell population was composed of Gr-1+ neutrophils, F4/80+ macrophages, as well as CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (sFigure 5). CD4 and CD8 cells additionally infiltrated the neoplastic epidermis (sFigure 5). Four week RAD001 papilloma treatment greatly reduced blood microvessel density, Gr-1+ and F4/80+ cells, and partially diminished CD4+ and CD8+ stromal infiltration (Figure 4A and sFigure 5). Thus, epidermal Rheb dysregulation triggered an mTORC1-dependent “angio-inflammatory” switch in association with neoplastic progression.

Figure 4. An mTORC1-dependent angio-inflammatory switch in Rheb transgenic skin.

(A) Inflammatory cell stromal and epidermal infiltration and induction of neovascularization in transgenic papillomas, both inhibited by 4-week RAD001 treatment. (B) Real-time RT-PCR of mRNAs encoding for angiogenic and inflammatory factors in wild-type, transgenic hyperplasia, and papilloma, and RAD001-treated transgenic back skin. Data were normalized as Z-score values and presented in a heat map using a blue-white-red (low-to-high expression) scale (left panel), and the ratio of mean values of hyperplastic, papilloma, and RAD001-treated transgenic back skin samples to the mean value of wild-type levels (right panel). (C) Tissue ELISAs of inflammatory chemo- and cytokines and VEGF in wild type, pre-neoplastic, papilloma, and RAD001-treated transgenic back skin. (D) HIF-1α and VEGF protein expression from wild-type back skin epidermis and transgenic papilloma (left panel), and ELISAs of conditioned media from keratinocyte cultures in 8% serum, without serum, or without serum in the presence of rapamycin. Shown are the means with standard deviations (N=4 mice per group). *p<0.05, two-tailed Student’s t-test (4B–D). Bar (A): 100μm.

We screened lysates from transgenic hyperplastic and neoplastic skin for expression of candidate factors potentially responsible for the angio-inflammatory switch. IL-1α, IL-1β mRNA levels, and mRNA and protein abundance for VEGF, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-17, CXCL1, CXCL2, TGF-β, and COX2 were increased in hyperplasia, markedly elevated in neoplasia, but greatly reduced by RAD001 (Figures 4B–C, [TGF-β and COX2 protein data not shown]). Consistent with the RAD001-responsive HIF-1 mRNA signature detected in neoplasia (Figure 4B), HIF-1α and VEGF levels were differentially increased in transgenic hyperplastic epidermis as early as three weeks of age (Figure 4D), suggesting mTORC1-mediated HIF-1α stabilization (31). We next determined transgenic keratinocyte paracrine factor expression potentially underlying stromal activation. IL-6, TNF-α, CXCL1, and CXCL2 were differentially elevated in a rapamycin-sensitive fashion in transgenic keratinocyte-conditioned media (Figure 4D).

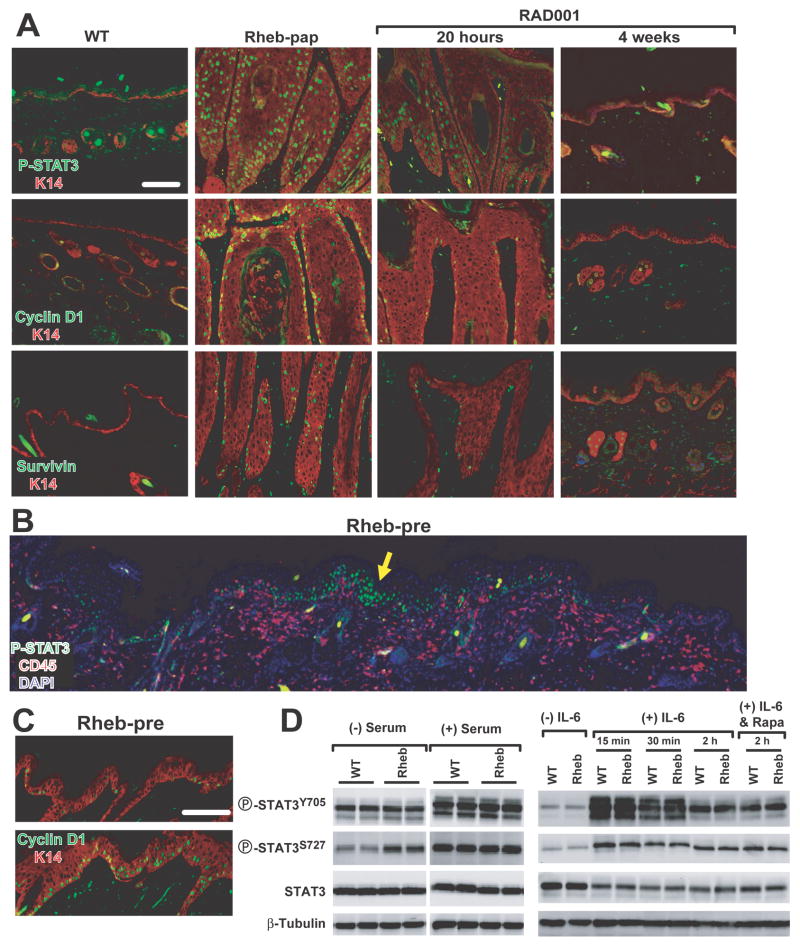

MTORC1-dependent STAT3 activation coincident with induction of the angio-inflammatory switch in transgenic epidermis

We interrogated activation and consequent downstream target gene induction of the transcription factor STAT3 in Rheb-mediated tumorigenesis, as it was a known direct target of both mTORC1 (32), and inflammatory cytokines, and its dysregulation was required for multistage skin carcinogenesis. There was a marked elevated frequency of cells positive for nuclear phospho-STAT3Y705 and increased expression of the STAT3 transcriptional targets, cyclin D1 and survivin, in transgenic papillomas (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. STAT3 pathway activation in transgenic epidermis required intact skin.

(A) STAT3 pathway activation in wild-type back skin, transgenic papilloma, and transgenic papillomas following RAD001 treatment for either 20 hours or 4 weeks. (B) Focal epidermal STAT3 activation (yellow arrow) with concomitant stromal inflammatory cell infiltration in hyperplastic transgenic back skin. (C) Induction of cyclin D1 expression in hyperplasia (upper panel) to nascent papilloma transition (lower panel). (D) STAT3 activation in wild-type and transgenic keratinocytes cultured for 16 hours without or with serum. Serum-starved transgenic and nontransgenic keratinocytes stimulated with 10ng/ml IL-6 for the indicated intervals alone or pretreated with rapamycin 4h before IL-6 stimulation. Bars (A, C): 100μm.

To determine a causal role for STAT3 in Rheb-mediated tumorigenesis, precursor skin hyperplasias were analyzed for STAT3 and stromal inflammatory cell expression patterns (Figure 5B and sFigure 6A). Precursor skin hyperplasias appeared to be the site of nascent papillomas as their epidermis was thicker and the lesions had an undulating appearance suggesting exophytic growth initiation (Figure 5B, C). Strikingly, pSTAT3Y705 was focally detectable in the epidermis concurrent with subjacent stromal inflammatory cell accumulations in these lesions (Figure 5B and sFigure 6A, yellow arrows). Immunoblotting confirmed that pJAK2Y1007/1008, pSTAT3Y705, and pSTAT3S727 levels were differentially elevated (sFigure 6B), and clustered cyclin D1-positive epithelial cells, were present in these nascent neoplastic foci, in contrast to their low frequency in diffuse hyperplasia (Figure 5C, cyclin D1, lower- versus upper-panel). Collectively these data support a role for progressive STAT3 activation and consequent incremental cyclin D1 dysregulation in the hyperplasia to neoplasia transition.

Next, we determined that pSTAT3Y705 was not activated in keratinocytes cultured in serum-free media (Figure 5D) despite the low-level upregulation of a repertoire of cytokines and chemokines (Figure 4D). In contrast, addition of the STAT3 activator IL6 to the culture at a papilloma-associated concentration, 10ng/ml, markedly activated pSTAT3Y705 and pSTAT3S727 in both transgenic and wild type keratinocytes. Rapamycin pre-treatment did not blunt phosphorylation of either STAT3 site induced by exogenous IL-6 (Figure 5D). Collectively, these data support the hypothesis that the paracrine signaling from the angio-inflammatory switch was necessary in order for IL-6 to attain a level sufficient to breach the epithelial STAT3 activation threshold.

We next tested the specificity of mTORC1-STAT3 regulation in Rheb neoplasia. Diminution in STAT3 activation occurred as early as 20 hours after RAD001 treatment with coordinate reduction of cyclin D1 and survivin protein (Figure 5A, RAD001, 20 hours). Four weeks of RAD001 reduced neoplastic epithelial phospho-STAT3Y705 to near wild type levels (Figure 5A, RAD001, 4 weeks). In contrast, a six-week trial of the EGFR inhibitor gefitinib had no effect on STAT3 activation or papilloma histology (data not shown). Moreover, four week celecoxib, a COX2 inhibitor, therapy also failed to affect papilloma persistence (data not shown). Collectively these data conclusively demonstrate that STAT3 activation in transgenic neoplasia was mTORC1-dependent and subject to feed-forward stromal-epithelial inflammatory amplification (sFigure 7).

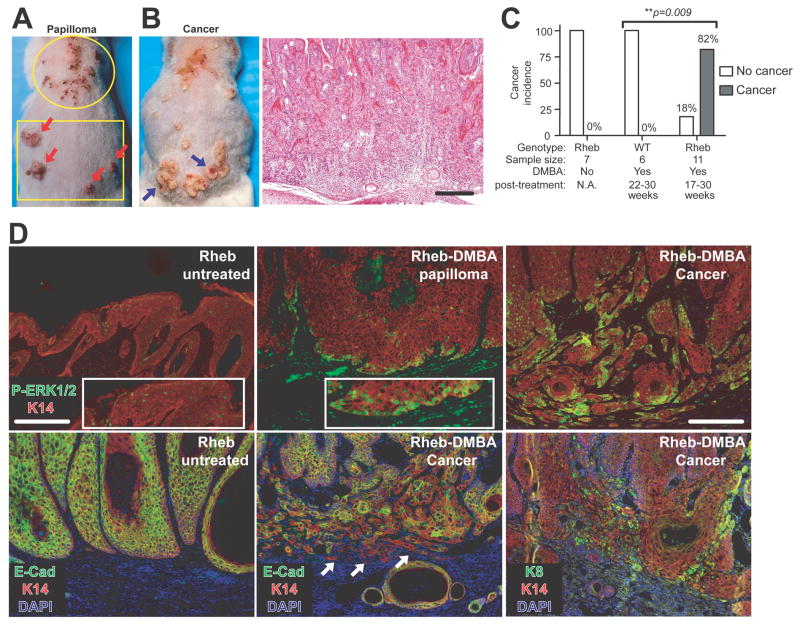

Rheb cooperation with DMBA in epidermal squamous carcinogenesis

To test whether Rheb gain-of-function could serve as a cooperative event in carcinogenesis, a single topical application of the tobacco carcinogen 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]-anthracene (DMBA) was administered to 8-week-old wild type and pre-neoplastic transgenic mice. Rheb-DMBA papillomas developed in both cephalic and caudal back skin (Figure 6A; Rheb-DMBA papilloma). A total of 9/11 transgenic mice between 17–30 weeks post-DMBA application developed invasive squamous cell carcinomas (Figures 6B–C). In contrast, 6 DMBA-treated wild-type mice, while universally developing sebaceous gland adenomas, did not evidence either papillomas or squamous carcinomas (data not shown). Elevated nuclear pERK1/2T202/Y204 immunoreactivity was uniformly detectable in basal cells of premalignant Rheb-DMBA papillomas (Figure 6D, upper-middle panel), in contrast to its sporadic incidence in terminally differentiated suprabasal cells in vehicle-treated transgenic papillomas (Figure 6D, upper-left panel). There was a further marked increase in nuclear pERK1/2T202/Y204 levels in nests of squamous carcinoma cells at the invasive front of Rheb-DMBA malignancies (Figure 6D, upper-right panel). While E-cadherin was expressed all Rheb papillomas, its expression was markedly reduced or absent in the invasive nests of Rheb-DMBA carcinomas (Figure 6D, lower-middle versus lower-left panel). Malignant invasive cells also expressed the primitive keratin-8 marker of poorly differentiated squamous carcinoma (Figure 6D, lower-right panel).

Figure 6. Rheb cooperates with carcinogen in the development of skin cancer.

(A) Expansion of regional susceptibility of transgenic papillomatosis by single-dose DMBA treatment (typical transgenic papilloma localization, circled area versus Rheb-DMBA papillomas, squared area [red arrows]). (B) Rheb-DMBA malignant conversion (blue arrows left panel), with corroborative histopathology (right panel). (C) Cancer incidence in aged DMBA-treated wild-type versus transgenic mice. Chi-square analysis with indicated p value. (D) ERK activation, loss of E-cadherin, and keratin-8 induction at the invasive front of a DMBA-Rheb squamous carcinoma. Bars (A): 250μm, (D): 100μm.

Discussion

Here, we provide evidence for RHEB locus gain/amplification in diverse human cancers, and association of RHEB overexpression with poor disease outcome. Transgenic mice overexpressing Rheb in basal epidermal keratinocytes develop multi-stage epithelial tumorigenesis, with rapalog sensitive neoplasias. Systemic RAD001 efficiently inhibited mTORC1 signaling in cultured keratinocytes and neoplasias arising in transgenic mice with lack of mTORC2 negative feedback (30). Rheb gain-of-function produced mTORC1-mediated overexpression of a collection of growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines triggering a focal stromal angio-inflammatory switch in hyperplasia that was dispersed throughout the stroma in neoplasia. We provided several lines of evidence supporting a pathway wherein mTORC1 induced HIF-1α and HIF-1 downstream angiogenic factors along with cell autonomous production of cytokines and chemokines. These factors produced a focal “angio-inflammatory switch” that in turn elevated the levels of cytokines such as IL6 to a level sufficient to activate epidermal STAT3 and trigger a feed-forward paracrine stromal-epithelial cross talk culminating in neoplasia (sFigure 7). Collectively, these data suggested that multiple mechanisms may be responsible for the selective advantages of RHEB locus amplification in human cancers, including adaptive growth in a sub-optimal tumor microenvironment, enhanced tumor nutrient/oxygen perfusion through angiogenesis, stimulation of tumor cell growth through paracrine regulation, and increased sensitivity to carcinogens, such as tobacco.

Chronic inflammation is a risk factor for various forms of human cancer, including breast and HN cancers (33, 34). Prolonged non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug usage (aspirin or COX2 inhibitors) reduces the incidence of several different types of neoplasia [31,33]. Here, RHEB/mTORC1 hyperactivation in cultured keratinocytes and intact skin upregulated HIF-1α, VEGF, IL-6, TNF-α, CXCL1, CXCL2, and COX2 mRNA and protein expression. Aggregate induction of these direct and indirect downstream targets was a likely mechanism for initiation and maintenance of the mTORC1-mediated “angio-inflammatory switch”. Our result thus extended a previous study showing an mTORC1/HIF-1/VEGF signaling cascade in prostate tumor cells (10), and our recent report on HIF-1 upregulation of TNF-α, CXCL1, and CXCL2 mRNA and protein levels in mouse epidermis (21).

A striking finding in the K14-Rheb transgenic model was that coordinate IL6 upregulation and STAT3 activation were solely detectable in hyperplasia and neoplasia but absent in cultured keratinocytes, which required exogenous IL6 to recapitulate in-vivo signaling. These experiments demonstrated the necessity of in-vivo epithelial-stromal juxtaposition for epithelial RHEB/mTORC1-mediated feed-forward stromal crosstalk culminating in tumorigenesis. Consistent with this notion, nascent transgenic papillomatosis was tightly associated with nuclear pSTAT3Y705 activation in squamous basal cells overlying focal inflammatory cell accumulations. Exquisite sensitivity of epidermal STAT3 activity to short-term RAD001 treatment was evidence for potent and rapid stromal inhibition by mTORC1 blockade. Two recent reports demonstrated a requirement for stromal-epithelial IL-6 and STAT3 activation axis in carcinogenesis associated with inflammatory bowel disease (35, 36). Moreover, both loss- and gain-of-function mouse models of epidermal STAT3 signaling highlighted a requirement for STAT3 activation in epidermal carcinogenesis (37, 38).

RHEB overexpression in breast and HN cancers was a risk factor for cancer progression independent of HER2 amplification or PTEN loss of function in breast cancer, or EGFR amplification/overexpression in HN cancer. RHEB overexpression could also underlie PI3K/AKT-independent mTORC1 activation in human cancers, previously identified in a subgroup from a large HN cancer cohort (39). Carcinogen exposure via smoking is a known risk factor for HN cancer (40), however cooperation between RHEB and smoke carcinogens has not been reported. Here, Rheb potently sensitized transgenic mice to a single dose of the DMBA producing multistage squamous carcinogenesis accompanied by coordinate induction of ERK1/2. These data suggest that these two signaling modules may collaborate in human carcinogenesis. Collectively, the combination of the transgenic, DMBA carcinogen, TMA, and in-silico transcriptome data, strongly support a functional contribution of RHEB gene to human carcinogenesis, particularly in malignancies in relation to environmental carcinogens, such as tobacco-associated carcinogens. Our K14-Rheb transgenic mice can be a platform for further dissection of mTORC1’s contribution to H&N and breast carcinogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robert Abraham for initial discussions, Heidi Lane for the gift of RAD001 from Novartis, and Rebecca Sohn for animal husbandry. This work was supported by NCI R01-101012 to JMA and GGC, and Beatrice Roe Urologic Cancer Fund to JMA.

References

- 1.Lee CH, Inoki K, Guan KL. mTOR pathway as a target in tissue hypertrophy. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:443–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18(16):1926–45. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12(1):9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;441(7092):424–30. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas GV. mTOR and cancer: reason for dancing at the crossroads? Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16(1):78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sancak Y, Thoreen CC, Peterson TR, et al. PRAS40 is an insulin-regulated inhibitor of the mTORC1 protein kinase. Mol Cell. 2007;25(6):903–15. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vander Haar E, Lee SI, Bandhakavi S, Griffin TJ, Kim DH. Insulin signalling to mTOR mediated by the Akt/PKB substrate PRAS40. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(3):316–23. doi: 10.1038/ncb1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30(2):214–26. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujishita T, Aoki K, Lane HA, Aoki M, Taketo MM. Inhibition of the mTORC1 pathway suppresses intestinal polyp formation and reduces mortality in ApcDelta716 mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(36):13544–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800041105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Majumder PK, Febbo PG, Bikoff R, et al. mTOR inhibition reverses Akt-dependent prostate intraepithelial neoplasia through regulation of apoptotic and HIF-1-dependent pathways. Nat Med. 2004;10(6):594–601. doi: 10.1038/nm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johannessen CM, Johnson BW, Williams SM, et al. TORC1 is essential for NF1-associated malignancies. Curr Biol. 2008;18(1):56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei C, Amos CI, Zhang N, et al. Suppression of Peutz-Jeghers polyposis by targeting mammalian target of rapamycin signaling. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(4):1167–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Podsypanina K, Lee RT, Politis C, et al. An inhibitor of mTOR reduces neoplasia and normalizes p70/S6 kinase activity in Pten+/− mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(18):10320–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171060098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neshat MS, Mellinghoff IK, Tran C, et al. Enhanced sensitivity of PTEN-deficient tumors to inhibition of FRAP/mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(18):10314–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171076798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robb VA, Karbowniczek M, Klein-Szanto AJ, Henske EP. Activation of the mTOR signaling pathway in renal clear cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2007;177(1):346–52. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Cancer Genome Project. Hinxton (Cambridge, UK): Wellcome Trust Genome Campus; [cited 2009 Jan 4]. Available from: http://www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nardella C, Chen Z, Salmena L, et al. Aberrant Rheb-mediated mTORC1 activation and Pten haploinsufficiency are cooperative oncogenic events. Genes Dev. 2008;22(16):2172–7. doi: 10.1101/gad.1699608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mavrakis KJ, Zhu H, Silva RL, et al. Tumorigenic activity and therapeutic inhibition of Rheb GTPase. Genes Dev. 2008;22(16):2178–88. doi: 10.1101/gad.1690808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elson DA, Thurston G, Huang LE, et al. Induction of hypervascularity without leakage or inflammation in transgenic mice overexpressing hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Genes Dev. 2001;15(19):2520–32. doi: 10.1101/gad.914801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu ZH, Wright JD, Belt B, Cardiff RD, Arbeit JM. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 facilitates cervical cancer progression in human papillomavirus type 16 transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(2):667–81. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scortegagna M, Cataisson C, Martin RJ, et al. HIF-1alpha regulates epithelial inflammation by cell autonomous NFkappaB activation and paracrine stromal remodeling. Blood. 2008;111(7):3343–54. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-115758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sobin LH, Fleming ID. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors, fifth edition (1997). Union Internationale Contre le Cancer and the American Joint Committee on Cancer. Cancer. 1997;80(9):1803–4. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971101)80:9<1803::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krajewska M, Zapata JM, Meinhold-Heerlein I, et al. Expression of Bcl-2 family member Bid in normal and malignant tissues. Neoplasia. 2002;4(2):129–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krajewska M, Smith LH, Rong J, et al. Image Analysis Algorithms for Immunohistochemical Assessment of Cell Death Events and Fibrosis in Tissue Sections. J Histochem Cytochem. 2009 doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.952812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tibes R, Qiu Y, Lu Y, et al. Reverse phase protein array: validation of a novel proteomic technology and utility for analysis of primary leukemia specimens and hematopoietic stem cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(10):2512–21. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oncomine database [Internet] Ann Arbor (MI): Compendia Bioscience, Inc; 2008. [cited 2009 Jan 4]. Available from: http://www.oncomine.com. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gene Expression Omnibus [Internet] Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information; [cited 2009 Jan 4 ]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rakha EA, Ellis IO. Triple-negative/basal-like breast cancer: review. Pathology. 2009;41(1):40–7. doi: 10.1080/00313020802563510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung CH, Parker JS, Karaca G, et al. Molecular classification of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas using patterns of gene expression. Cancer Cell. 2004;5(5):489–500. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Reilly KE, Rojo F, She QB, et al. mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates Akt. Cancer Res. 2006;66(3):1500–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faivre S, Kroemer G, Raymond E. Current development of mTOR inhibitors as anticancer agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5(8):671–88. doi: 10.1038/nrd2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yokogami K, Wakisaka S, Avruch J, Reeves SA. Serine phosphorylation and maximal activation of STAT3 during CNTF signaling is mediated by the rapamycin target mTOR. Curr Biol. 2000;10(1):47–50. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)00268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan TT, Coussens LM. Humoral immunity, inflammation and cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19(2):209–16. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeNardo DG, Coussens LM. Inflammation and breast cancer. Balancing immune response: crosstalk between adaptive and innate immune cells during breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(4):212. doi: 10.1186/bcr1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bollrath J, Phesse TJ, von Burstin VA, et al. gp130-mediated Stat3 activation in enterocytes regulates cell survival and cell-cycle progression during colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(2):91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grivennikov S, Karin E, Terzic J, et al. IL-6 and Stat3 are required for survival of intestinal epithelial cells and development of colitis-associated cancer. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(2):103–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan KS, Sano S, Kiguchi K, et al. Disruption of Stat3 reveals a critical role in both the initiation and the promotion stages of epithelial carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(5):720–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI21032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sano S, Chan KS, Carbajal S, et al. Stat3 links activated keratinocytes and immunocytes required for development of psoriasis in a novel transgenic mouse model. Nat Med. 2005;11(1):43–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molinolo AA, Hewitt SM, Amornphimoltham P, et al. Dissecting the Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling network: emerging results from the head and neck cancer tissue array initiative. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(17):4964–73. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deshpande AM, Wong DT. Molecular mechanisms of head and neck cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008;8(5):799–809. doi: 10.1586/14737140.8.5.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.