Abstract

Chandipura virus (CHPV) is an emerging human pathogen associated with acute encephalitis and is related closely to vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), a prototype rhabdovirus. Here, we demonstrate that the RNA polymerase L protein of CHPV exhibits a VSV-like RNA : GDP polyribonucleotidyltransferase (PRNTase) activity, which transfers the 5′-monophosphorylated (p-) viral mRNA start sequence to GDP to produce a capped RNA, and that the conserved HR motif in the CHPV L protein is essential for the PRNTase activity. Interestingly, the CHPV L protein was found to form two distinct SDS-resistant complexes with the CHPV mRNA and leader RNA start sequences; mutations in the HR motif significantly reduced the formation of the former complex (a putative covalent enzyme–pRNA intermediate in the PRNTase reaction), but not the latter complex. These results suggest that the rhabdoviral L proteins universally use the active-site HR motif for the PRNTase reaction at the step of the enzyme–pRNA intermediate formation.

Unconventional mRNA capping of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV, Indiana), a prototype non-segmented, negative-strand (NNS) RNA virus belonging to the genus Vesiculovirus of the family Rhabdoviridae in the order Mononegavirales, is catalysed by the multifunctional RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) L protein (Ogino & Banerjee, 2007, 2008). At the first step, the guanosine 5′-triphosphatase (GTPase) activity of the VSV L protein produces GDP (an RNA acceptor) by hydrolysis of GTP (Ogino & Banerjee, 2007, 2008). Subsequently, the RNA : GDP polyribonucleotidyltransferase (PRNTase) domain in the VSV L protein transfers the 5′-monophosphorylated (p-) RNA moiety of the 5′-triphosphorylated (ppp-) RNA with the conserved VSV mRNA start sequence (AACAG) to GDP to generate the GpppA capped RNA through a covalent enzyme–pRNA intermediate (Ogino & Banerjee, 2007, 2008; Ogino et al., 2010). The latter intermediate is composed of pRNA linked covalently to the active-site histidine residue at position 1227 (H1227) within the conserved HR (H1227–R1228) motif via a phosphoamide bond (Ogino et al., 2010). By mutational analyses, we have recently demonstrated that the HR motif and a basic amino acid residue (R1221) in the vicinity of the HR motif are necessary for the PRNTase activity of the VSV L protein at the step of the enzyme–pRNA intermediate formation (Ogino et al., 2010). The HR motif is strikingly conserved in the L proteins of >80 NNS RNA viruses (e.g. rabies, measles, mumps, Ebola and Borna disease viruses) belonging to different families, whilst the R1221 residue is conserved only in the L proteins of vesiculoviruses [e.g. VSV, Chandipura virus (CHPV)], lyssaviruses (e.g. rabies virus) and an ephemerovirus (bovine ephemeral fever virus) belonging to the family Rhabdoviridae (Ogino et al., 2010).

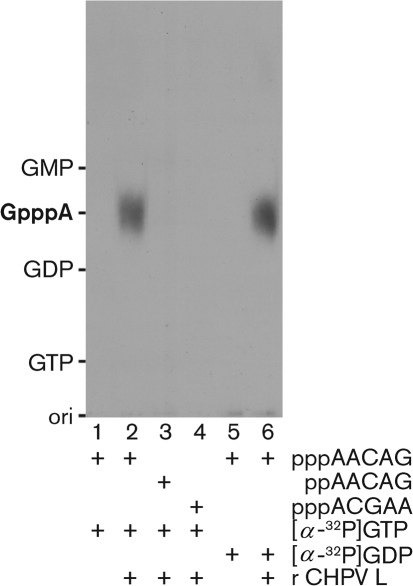

To examine the universality of the RNA-capping mechanism by the rhabdoviral L proteins, we generated the recombinant L protein of CHPV, an emerging vesiculovirus that causes acute viral encephalitis with high mortality in children in India (Chadha et al., 2005; Rao et al., 2004). The recombinant CHPV L protein was expressed as a carboxyl-terminal octahistidine-tagged form [2092+10 (SRHHHHHHHH) aa] in Sf21 insect cells infected with a recombinant baculovirus carrying a cDNA encoding the CHPV L protein (Marriott, 2005) and purified by chromatography using nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Qiagen), as described for the recombinant VSV L protein (Ogino & Banerjee, 2007; Ogino et al., 2010). First, we measured the RNA-capping activity of the CHPV L protein (Fig. 1) according to the method developed for the VSV L protein (Ogino & Banerjee, 2007, 2008; Ogino et al., 2010). To analyse the substrate specificity of the CHPV L protein (PRNTase), we used 5′-tri- (ppp-) or di- (pp-) phosphorylated oligoRNAs corresponding to the CHPV mRNA and leader RNA start sequences (AACAG and ACGAA, respectively), which are the same as in VSV (Marriott, 2005), and [α-32P]GTP or [α-32P]GDP. When pppAACAG was incubated with [α-32P]GTP in the presence of the CHPV L protein, a distinct GpppA cap structure was produced (Fig. 1, lane 2). Similar to the VSV L protein, ppAACAG and pppACGAA did not serve as the substrate for the CHPV L protein (lanes 3 and 4). As the cellular capping enzyme composed of RNA 5′-triphosphatase and GTP : RNA guanylyltransferase can use ppp- or ppRNA with any sequence as the substrate to produce GpppRNA (Furuichi & Shatkin, 2000; Shuman, 2001), the capping activity associated with the CHPV L protein is different from the cellular activity; thus, it is thought to be intrinsic to the viral protein. Furthermore, the CHPV L protein was found to produce the GpppA cap structure with [α-32P]GDP (an inert substrate for the cellular capping enzyme) instead of [α-32P]GTP (lane 6), indicating that the CHPV L protein catalyses a similar unconventional RNA-capping reaction to VSV by the PRNTase activity. Under standard conditions, the CHPV L protein (0.3 μg) produced 0.74±0.04 fmol (mean±sd of three independent determinations) of GpppA with [α-32P]GDP. The specific activity of the CHPV L protein in RNA capping with GDP [2.5 fmol GpppA (μg protein)−1] was approximately 800-fold lower than that of the VSV L protein [2.1 pmol GpppA (μg protein)−1] (Ogino et al., 2010), despite its 60 % amino acid sequence identity to the VSV L protein (Marriott, 2005). It is noteworthy that the transcriptase activity of CHPV is significantly lower than that of VSV (Chang et al., 1974).

Fig. 1.

RNA-capping activity of the CHPV L protein. The recombinant CHPV L protein (0.3 μg) was subjected to RNA-capping reactions with the indicated substrates. Calf intestine alkaline phosphatase- and nuclease P1-resistant products were analysed by PEI–cellulose thin-layer chromatography followed by autoradiography. Lanes 1 and 5 indicate no L protein. The positions of standard marker compounds, visualized under UV light at a wavelength of 254 nm, are shown on the left.

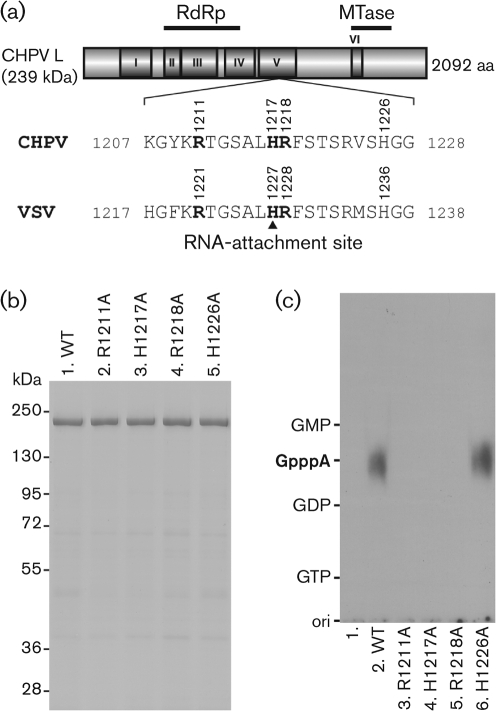

To ascertain the significance of the R1211, H1217 and R1218 residues in the CHPV L protein [the counterparts of the R1221, H1227 and R1228 residues of the VSV L protein (Fig. 2a)] in the PRNTase activity, these residues were replaced with alanine (Fig. 2b, lanes 2–4). In addition, we prepared a CHPV L mutant with an alanine substitution for the non-conserved H1226 residue (the counterpart of the non-essential H1236 residue of the VSV L protein; Fig. 2a, b, lane 5). As shown in Fig. 2c (lanes 3–6), the R1211A, H1217A and R1218A mutants, but not the H1226A mutant, were completely inactive in RNA capping with pppAACAG and [α-32P]GDP, indicating that the CHPV L protein uses these active-site amino acid residues (R1211, H1217 and R1218), which are identical to those in the VSV L protein, for the VSV-like PRNTase activity.

Fig. 2.

The HR motif is essential for the PRNTase activity of the CHPV L protein. (a) A schematic structure of the CHPV L protein (2092 aa) is shown, with six amino acid sequence blocks (I–VI) conserved in the NNS RNA viral L proteins. The positions of the putative RdRp and cap methyltransferase (MTase) domains are indicated. The local sequence containing the HR motif in the CHPV L protein is compared with that in the VSV L protein (H1227, the covalent RNA-attachment site). (b) Wild-type (WT) and mutant CHPV L proteins with indicated amino acid substitutions (0.7 μg) were analysed by SDS-PAGE (7.5 % gel) followed by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue. The positions of marker proteins are indicated on the left. (c) The WT and mutant CHPV L proteins (0.3 μg) were subjected to RNA-capping reactions with pppAACAG and [α-32P]GDP as substrates. Lane 1 indicates no L protein.

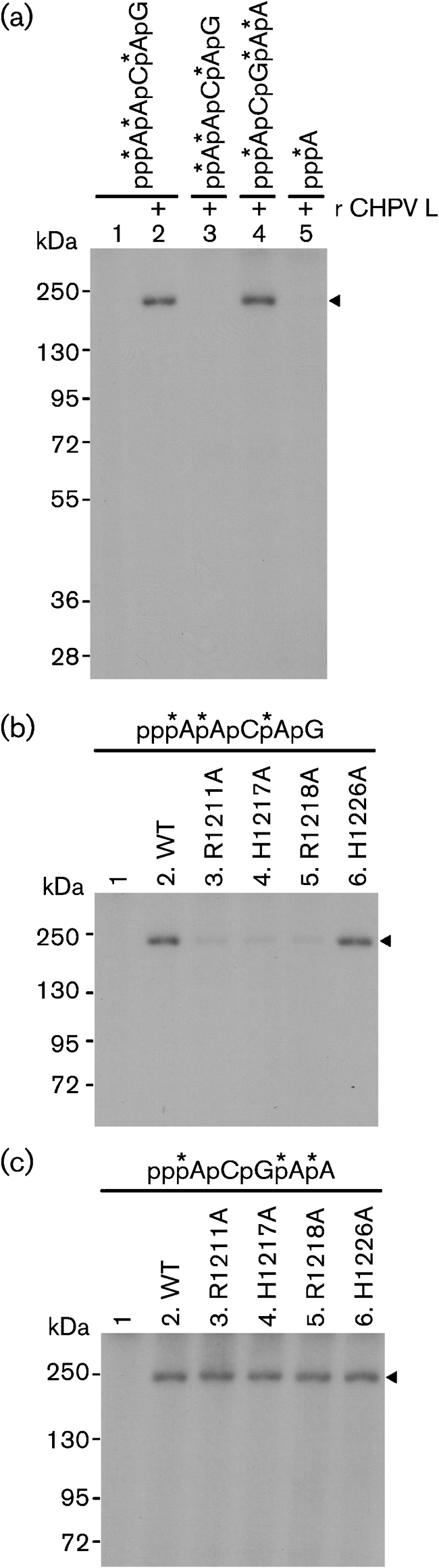

Our demonstration that the CHPV L protein exhibits the capping (PRNTase) activity prompted us to detect a covalent CHPV L protein–pRNA complex, an enzyme–pRNA intermediate in the PRNTase reaction. As described for the VSV L protein (Ogino & Banerjee, 2007; Ogino et al., 2010), the enzyme–pRNA intermediate (L–pRNA complex) formation assay was performed using the purified recombinant CHPV L protein. Briefly, the CHPV L protein was incubated with 32P-labelled pppRNA, and the resulting complexes were analysed by SDS-PAGE (7.5 % gel) followed by autoradiography. As shown in Fig. 3(a) (lane 2), the CHPV L protein reacted with pppAACAG (mRNA start sequence), resulting in generation of an SDS-resistant L–RNA complex, but not with ppAACAG (lane 3). Interestingly, the CHPV L protein formed an L–RNA complex with pppACGAA (leader RNA start sequence, lane 4) to an extent similar to that formed with the mRNA start sequence (lane 2). This result is in contrast to the VSV L protein, which reacts with pppAACAG to a greater extent than with pppACGAA to form the covalent L–pRNA complex (the intermediate in the PRNTase reaction) (Ogino & Banerjee, 2007). On the other hand, the CHPV L protein did not form a complex with [α-32P]ATP (lane 5), indicating that the SDS-resistant complex formation is specific to polynucleotides, similar to the VSV L protein (Ogino & Banerjee, 2007). Finally, we examined effects of the mutations in the PRNTase active site of the CHPV L protein on the formation of the SDS-resistant L–RNA complexes with the mRNA and leader RNA sequences. As shown in Fig. 3(b) (lanes 3–5), the R1211A, H1217A and R1218A mutations greatly reduced the L–RNA complex formation activity with the pppAACAG mRNA start sequence, but the H1226A mutation did not (lane 6). In contrast, all mutations (R1211A, H1217A, R1218A and H1226A) did not affect L–RNA complex formation with the pppACGAA leader RNA start sequence (Fig. 3c, lanes 3–6). Therefore, complex formation between the CHPV L protein and the pppACGAA leader RNA start sequence does not appear to be involved in the RNA-capping reaction. Thus, we conclude that the conserved HR motif in the CHPV L protein is essential for the PRNTase activity at the step of the enzyme–pRNA intermediate (L–pRNA complex) formation. The H1217 residue in the HR motif is strongly suggested to be a covalent RNA-attachment site in the PRNTase domain of the CHPV L protein, because the histidine residue in the HR motif of the VSV L protein has been identified as the covalent RNA-attachment site (Ogino et al., 2010). On the other hand, as the R1211 residue (a counterpart of the R1221 residue in the VSV L protein) is conserved only in the L proteins of some rhabdoviruses (vesiculo-, lyssa- and ephemeroviruses), it is suggested to be involved in some important step of the enzyme–pRNA intermediate formation that is specific for the above rhabdoviruses, e.g. sequence-specific recognition of the 5′-triphosphorylated RNA substrate. Interestingly, the mRNAs of above rhabdoviruses contain conserved mRNA start sequences (5′-AACA) (Bourhy et al., 1993; Hoffmann et al., 2002; Marriott, 2005; McWilliam et al., 1997), whereas mRNAs of other NNS RNA viruses have unique sets of mRNA start sequences. It should also be noted that all cap-deficient mutants (R1211A, H1217A and R1218A) of the CHPV L protein retained very weak activities of binding with the mRNA start sequence (Fig. 3b, lanes 3–5). It is thus conceivable that the CHPV L protein contains, in addition to the HR motif, other RNA-attachment sites that are probably not involved in RNA capping. Further studies are needed to define the roles, if any, of such putative RNA-attachment sites in RNA synthesis.

Fig. 3.

The HR motif in the CHPV L protein is required for the formation of the enzyme–pRNA intermediate in the PRNTase reaction. (a) Recombinant CHPV L protein (0.3 μg) was incubated with the indicated mono- or polyribonucleotide labelled with 32P (shown by asterisks), and then analysed by SDS-PAGE (7.5 % gel) followed by autoradiography. Note that all nucleotide probes had the same specific radioactivities. Lane 1 indicates no L protein. The position of covalent L–RNA complexes is indicated by the arrowhead. (b, c) The WT and mutant CHPV L proteins (0.3 μg) were incubated with pppAACAG [mRNA start sequence (b)] or pppACGAA [leader RNA start sequence (c)] labelled with 32P (shown by asterisks). The resulting covalent L–RNA complexes were analysed by SDS-PAGE (7.5 % gel) followed by autoradiography. Lane 1 indicates no L protein.

Here, we showed that the CHPV L protein selectively uses pppAACAG (the CHPV mRNA start sequence) and GDP as the substrates to produce the GpppA cap structure, indicating that the CHPV L protein also carries out the unconventional mRNA-capping mechanism involving the PRNTase activity. Furthermore, as in the case of the VSV L protein, the HR motif in the CHPV L protein was shown to be crucial for the PRNTase activity at the step of the enzyme–pRNA intermediate formation. Our findings provide the second example of an RNA-transfer enzyme with the conserved HR motif that catalyses unconventional capping of rhabdoviral mRNA, thus offering a common target for developing anti-rhabdoviral agents.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anthony C. Marriott (University of Warwick, UK) for the plasmid encoding the CHPV L protein. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (AI26585 to A. K. B.).

References

- Bourhy, H., Kissi, B. & Tordo, N. (1993). Molecular diversity of the Lyssavirus genus. Virology 194, 70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadha, M. S., Arankalle, V. A., Jadi, R. S., Joshi, M. V., Thakare, J. P., Mahadev, P. V. & Mishra, A. C. (2005). An outbreak of Chandipura virus encephalitis in the eastern districts of Gujarat state, India. Am J Trop Med Hyg 73, 566–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S. H., Hefti, E., Obijeski, J. F. & Bishop, D. H. (1974). RNA transcription by the virion polymerases of five rhabdoviruses. J Virol 13, 652–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuichi, Y. & Shatkin, A. J. (2000). Viral and cellular mRNA capping: past and prospects. Adv Virus Res 55, 135–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, B., Schutze, H. & Mettenleiter, T. C. (2002). Determination of the complete genomic sequence and analysis of the gene products of the virus of spring viremia of carp, a fish rhabdovirus. Virus Res 84, 89–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marriott, A. C. (2005). Complete genome sequences of Chandipura and Isfahan vesiculoviruses. Arch Virol 150, 671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam, S. M., Kongsuwan, K., Cowley, J. A., Byrne, K. A. & Walker, P. J. (1997). Genome organization and transcription strategy in the complex GNS–L intergenic region of bovine ephemeral fever rhabdovirus. J Gen Virol 78, 1309–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogino, T. & Banerjee, A. K. (2007). Unconventional mechanism of mRNA capping by the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of vesicular stomatitis virus. Mol Cell 25, 85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogino, T. & Banerjee, A. K. (2008). Formation of guanosine(5′)tetraphospho(5′)adenosine cap structure by an unconventional mRNA capping enzyme of vesicular stomatitis virus. J Virol 82, 7729–7734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogino, T., Yadav, S. P. & Banerjee, A. K. (2010). Histidine-mediated RNA transfer to GDP for unique mRNA capping by vesicular stomatitis virus RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 3463–3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao, B. L., Basu, A., Wairagkar, N. S., Gore, M. M., Arankalle, V. A., Thakare, J. P., Jadi, R. S., Rao, K. A. & Mishra, A. C. (2004). A large outbreak of acute encephalitis with high fatality rate in children in Andhra Pradesh, India, in 2003, associated with Chandipura virus. Lancet 364, 869–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuman, S. (2001). Structure, mechanism, and evolution of the mRNA capping apparatus. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 66, 1–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]