Abstract

Both interferon-γ-producing type 1 T helper (Th1)- and interleukin-17 (IL-17)-producing Th17 cells have been proposed to be involved in anti-fungal host defence. Although invasive aspergillosis is one of the most severe human fungal infections, little is known regarding the relative importance of the Th1 versus Th17 cellular immune pathways for the human anti-Aspergillus host defence. Using human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and a system consisting of monocyte-derived macrophages with lymphocytes, we found that Aspergillus fumigatus is a weak inducer of human IL-17 but induces a strong Th1 response. These data were validated by the very low IL-17 levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and serum of patients with invasive aspergillosis. Surprisingly, live A. fumigatus reduced IL-17 production induced by mitogenic stimuli. This effect was mediated through the propensity of A. fumigatus to metabolize tryptophan and release kynurenine, which modulates the inflammatory response through inhibition of IL-17 production. In conclusion, A. fumigatus does not stimulate production of IL-17 and human host defence against aspergillosis may not rely on potent Th17 responses.

Keywords: Aspergillus, interleukin-17, interferon-γ, kynurenine, macrophages

Introduction

Aspergillus fumigatus, an opportunistic ubiquitous mould, causes invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised hosts with high rates of mortality and morbidity.1,2 Until recently, the paradigm of the type 1 T helper (Th1) and type 2 T helper (Th2) cells was traditionally the model upon which knowledge of the host immune response to fungal infection was based.3,4 These CD4+ T-cell subtypes mediate distinct immune responses. Th1 cells produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ), which induces protective antifungal defence mechanisms, whereas Th2 cells release interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-10, which evoke a humoral response and in turn down-regulate Th1-dependent mechanisms.5 It is the balance between Th1 and Th2 responses that has been perceived as critical in determining the outcome of invasive fungal diseases.6

However, the recent discovery in both mice and man of a novel member of the CD4+ effector T-cell family (Th17 cells) producing IL-17 has provided novel insights into the immune mechanisms that are responsible for both protection from infections and immunopathology in autoimmune diseases.7–9 Differentiation of murine and human naive CD4+ T cells into either Th1, Th2 or Th17 cells depends on the cytokine milieu present at the time of initial engagement of the T-cell receptor and co-stimulatory receptors.10 Homology between human and murine IL-17 is high and the major function of IL-17 is to promote recruitment and activation of neutrophils.11 As a result of these effects, IL-17 is generally perceived as having a protective role against fungal infection, as demonstrated by an increased susceptibility to disseminated candidiasis of mice lacking the IL-17 receptor.12 However, human Th17 cells have a different origin from those in mice,13 and the cytokines that direct Th17 development exert their effect differently in the two hosts.14

Few and conflicting data are available regarding the potential role of IL-17 for the host defence against A. fumigatus. On the one hand, IL-17 was recently reported to hamper neutrophil-mediated killing of A. fumigatus and the in vivo clearance of the organism in non-immunosuppressed mice.15 In contrast, other data suggest a protective role for IL-17 in host defence against A. fumigatus. Neutralization of IL-17 early in host defence against A. fumigatus infection in non-immunosuppressed mice resulted in an increased pulmonary fungal burden.16 Very little is known regarding the role of IL-17 for the host defence against Aspergillus infections in humans.

On this background and with the understanding that regulation of the Th17 pathway may differ between murine and human cells, we studied the IL-17 host response to A. fumigatus in human leucocytes and in patients with invasive aspergillosis.

Materials and methods

Micro-organisms

The A. fumigatus strain V05-27 is a previously characterized clinical isolate.17 Live conidia and heat-killed hyphae were obtained as previously described.18 For the experiments involving Aspergillus-conditioned medium, live V05-27 A. fumigatus (at concentrations as specified) was grown in RPMI-1640 DM (ICN Biomedicals, Costa Mesa, CA) supplemented with 10 μg/ml gentamicin, 10 mm l-glutamine and 10 mm pyruvate at 37°. After 3 days, the culture suspension was centrifuged and the supernatant was passed through a 0·2-μm filter (Whatman GmbH, Dassel, Germany). In addition, conidia arrested at the different growth phases were prepared from A. fumigatus B-5233, another well-characterized strain.19 After incubation on Aspergillus minimal agar media for 1 week, both resting and germinating conidia (following incubation for 4 hr at 37° in liquid broth yeast nitrogen base; Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ) were harvested in 0·01% Tween-20/phosphate-buffered saline, washed with sterile distilled water and resuspended in Hanks’ balanced saline solution without Ca2+and Mg2+. Conidia were heat-inactivated by incubation at 65°.20 The treatment was repeated until no viable conidia were detected on the malt agar plates. All specimens were kept frozen at − 20° until use.

Heat-killed Candida albicans blastoconidia, strain American Type Culture Collection MYA-3573 (UC820) were used as a positive control.21,22 Experiments involving heat-killed C. albicans blastoconidia at a concentration of 106 micro-organisms/ml were performed in a similar manner to that described above.

Reagents

Anti-CD3/anti-CD28-coated beads (to mimic the action of antigen-presenting cells for T-cell activation) were purchased from Miltenyi-Biotech (Utrecht, the Netherlands) and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Recombinant human IL-1β (rIL-1β; 50 ng/ml) from Biosource (Etten-Leur, the Netherlands), IL-6 (rIL-6; 50 ng/ml) and IL-23 (rIL-23; 50 ng/ml) from R&D Systems (Abingdon, UK) were used. Rabbit anti-human anti-IFN-γ (10 μg/ml) was purchased from U-CyTech (Utrecht, the Netherlands) and corresponding isotype control, rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG), from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). Kynurenine and tryptophan were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Zwijndrecht, the Netherlands). The dectin-1 receptor antagonist, laminarin, was kindly provided by Dr David Williams (University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN). Anti-human monoclonal antibody against mannose receptor CD206 (α-MR) and the corresponding isotype control were purchased from BD Pharmingen (Breda, the Netherlands).

In vitro cytokine production

Separation and stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) was performed as described previously.23 Briefly, venous blood was drawn into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes from healthy volunteers after informed consent. The PBMC were isolated by density centrifugation on Ficoll–Hypaque (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). Cells were washed twice in saline, counted and the number adjusted to 5 × 106 cells/ml. For experiments involving monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM),24 PBMC were maintained in culture medium (RPMI-1640 DM supplemented with gentamicin, l-glutamine and pyruvate) in the presence of 10% human pooled serum in humidified atmosphere (5% CO2) at 37° for 6–7 days to permit differentiation with the lymphocyte component in situ. Culture medium was refreshed after 3 days. Stimulation assays were performed in 96-well plates (Greiner, Alphen a/d Rijn, the Netherlands) using 100 μl volume of PBMC or MDM with lymphocytes (abbreviated as MDM/lymphocytes), and the various stimuli to a total volume of 200 μl/well. For the investigation of Th17 responses, the cells were incubated with the pathogen at 37° for 3 or 7 days.25 After incubation, the supernatants were collected and stored at − 20° until assay.

Flow cytometry

The MDM/lymphocytes were stimulated for 4–6 hr with 13-phorbol 12-myristate acetate (50 ng/ml; Sigma) and ionomycin (1 μg/ml; Sigma) in the presence of Golgiplug (BD Biosciences, Breda, the Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were first stained extracellularly using an allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody (BD Biosciences). Subsequently the cells were fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences) and then intracellularly stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-IL-17 (eBiosciences, Halle-Zoersel, Belgium). Samples were measured on a FACSCalibur and data were analysed using the FlowJo software (version 7.2.5.).

Patients

Serum from haematology patients diagnosed with proven or probable invasive aspergillosis (IA)26 and bronchoalveolar lavages (BALs) of IA patients as per European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer criteria27 were obtained before the initiation of appropriate treatment and in line with the respective institutional guidelines. Matched controls comprised similar patient cohorts with underlying haematological malignancies who did not have IA.

Cytokine assay

Interleukin-6, IL-10 and IFN-γ were measured using commercial enzyme-linked immunsorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Pelikine Sanquin Compact, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Interleukin-17 was measured by the appropriate commercial ELISA kit (R&D Systems). Detection limits were 8 pg/ml (IL-6 and IL-10), 20 pg/ml (IFN-γ) and 16 pg/ml (IL-17).

Tryptophan and kynurenine measurement

Levels of tryptophan and kynurenine produced by live A. fumigatus in Aspergillus-conditioned medium were quantified by ultraviolet detection with high-performance liquid chromatography. This was performed on a SpectraSYSTEM autosampler and pump (Thermo Separation Products, San Jose, CA). Chromatographic separation was performed using an Inertsil 5 ODS-2 column (100 mm × 3·0 I.D.) (Varian Inc., Middelburg, the Netherlands). Absorbance was monitored with a diode-array detector (UV6000LP; Thermo Separation Products, San Jose, CA) at wavelength of 280 nm for tryptophan and 360 nm for kynurenine.28 The mobile phase for isocratic elution was made by dissolving 40 mm sodium acetate. The pH of the eluent was adjusted to pH 4·5 with a solution of 40 mm citric acid and 2% acetonitrile of the total volume buffer was added. The continuous flow rate was 0·3 ml/min.29 For calibration, the standard was diluted in RPMI-1640 in the concentration range of 0–72 μm for tryptophan, and 0–42 μm for kynurenine. 50 μl of the standard or sample was injected into the column for measurement.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed in duplicates. For the in vitro experiments, results from three sets of separate experiments (involving five or more distinct healthy volunteers) were pooled and analysed using spss 16.0 statistical software. Data as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) and the Wilcoxon signed rank test were used to compare differences between groups (unless otherwise stated). The level of significance was set at P < 0·05.

Results

Aspergillus fumigatus is a poor inducer of human IL-17 by PBMC and MDM/lymphocytes systems

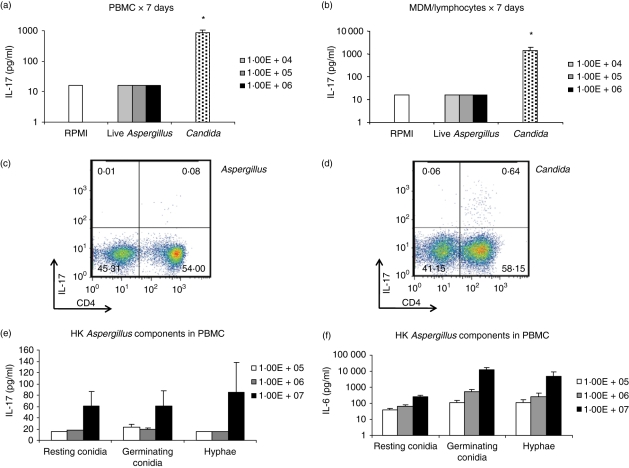

We investigated the capacity of A. fumigatus to induce production of IL-17 by human PBMC. Incubation of live A. fumigatus V05-27 conidia (at doses of 104–106 micro-organisms/ml) with PBMC over 7 days induced little IL-17, in contrast to C. albicans, a known inducer of IL-17 (Fig. 1a).25 We also assessed the capacity of the MDM/lymphocytes system to mediate IL-17 induction. However, IL-17 production upon incubation with live Aspergillus conidia was also almost undetectable in this system (Fig. 1b). Flow cytometric analysis further corroborated the low propensity of live Aspergillus conidia to induce IL-17, in contrast to C. albicans, as illustrated by the absence of IL-17-producing CD4+cells (Fig. 1c,d).

Figure 1.

(a, b) Interleukin-17 (IL-17) -inducing capacity of 104–106 micro-organisms/ml Aspergillus fumigatus in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM)/lymphocytes systems over 7 days with Candida albicans as positive control. (c, d) Flow cytometry of MDM/lymphocytes stimulated by A. fumigatus and C. albicans, respectively. The cells were labelled with anti-CD4-allophycocyanin and anti-IL-17-fluorescein isothiocyanate. Density plots show surface staining of CD4 (x-axis) and intracellular staining of IL-17 (y-axis). Numbers on the plots represent percentage of cells bearing positivity for the respective markers. Results from a representative experiment are shown. (e, f) IL-17 and IL-6 induced by 105–107 micro-organisms/ml of heat-killed A. fumigatus components: resting conidia, germinating conidia and hyphae in PBMC. Stimulation studies are cumulative from three sets of experiments. *P < 0·05 compared with control (RPMI-1640). Aspergillus: live A. fumigatus conidia (unless otherwise stated), Candida: heat-killed C. albicans blastoconidia (as positive control), HK: heat-killed.

To validate these findings and to demonstrate that the observed phenomenon was not strain-specific, we repeated the experiments using either heat-inactivated conidia of a different, well-characterized A. fumigatus strain B-5233 that were arrested at the resting and germinating conidial growth stage, or with heat-killed V05-27 A. fumigatus hyphae. All of the above Aspergillus preparations showed limited IL-17 responses across the concentration range of 105–107 micro-organisms/ml (Fig. 1e). In contrast, the Aspergillus components induced a distinct dose-dependent trend in IL-6 production, excluding significant cellular toxicity as the primary cause of the limited IL-17 production (Fig. 1f). In line with this, lactate dehydrogenase levels in supernatants of cells stimulated with live Aspergillus conidia were not elevated compared with vehicle-stimulated controls. Hence, both live and heat-inactivated A. fumigatus at different stadia were poor inducers of IL-17 in human cells.

Aspergillus fumigatus induces strong Th1 responses

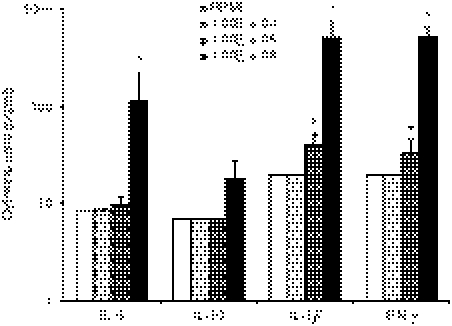

It has been described that host immune response to A. fumigatus is primarily Th1-mediated, accompanied by the production of IFN-γ.30,31 We have also demonstrated the propensity of live A. fumigatus conidia to induce a robust IFN-γ response in contrast to the absence of IL-17, or the limited IL-6 and IL-10 production in the MDM/lymphocytes system (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-10, interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and IL-1β production by monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) following stimulation by live Aspergillus fumigatus at incremental concentrations. IFN--γ and IL-1β responses are robust compared with IL-6 and IL-10. *P < 0·05 compared with RPMI-1640 control, n = 8 subjects.

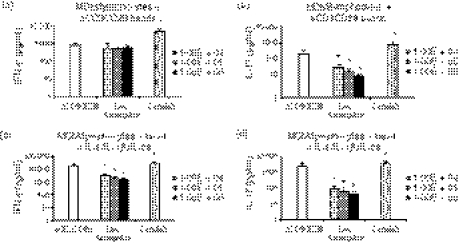

Live Aspergillus attenuates IL-17 production

As other studies have used mitogenic stimulation with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies to induce Th17 responses, live Aspergillus conidia were added to MDM/lymphocytes in the presence of anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads. Surprisingly, IL-17 levels remained low in the presence of A. fumigatus compared with the mitogenic stimulation alone and even showed a dose-dependent inverse relationship to the concentration of the pathogen. (Fig. 3a,b). Adding recombinant IL-6, IL-1β and IL-23 to the anti-CD3/anti-CD28-activated cells failed to increase IL-17 induction by A. fumigatus (Fig. 3c,d). IFN-γ production showed a trend towards inhibition by Aspergillus but this was not as markedly attenuated as the IL-17 response.

Figure 3.

(a, b) Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-17 (IL-17) produced by monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM)/lymphocytes stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads alone and with incremental amounts of Aspergillus fumigatus or Candida albicans (positive control) over 3 days (c, d) In addition to anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads, recombinant IL-6 (rIL-6) + rIL-1β + rIL-23 were added to MDM/lymphocytes stimulated with A. fumigatus or C. albicans (positive control) over 3 days. *P < 0·05 compared with stimulated MDM/lymphocytes but without pathogen, n = 6 subjects. Aspergillus: live A. fumigatus conidia, Candida: heat-killed C. albicans blastoconidia, aCD3CD28: anti-CD3/anti-CD28-coated beads.

Weak IL-17 response is not linked to the pro-Th1 propensity of A. fumigatus

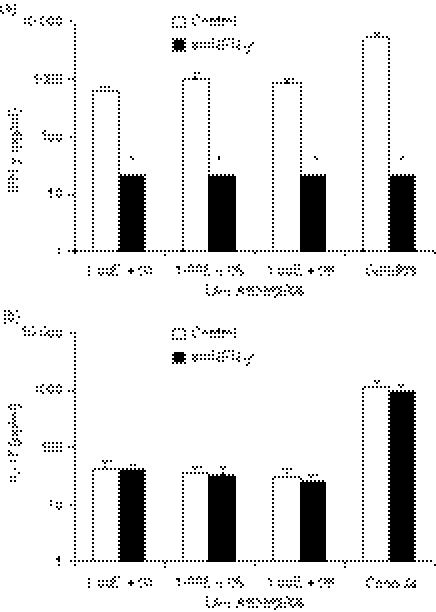

Interferon-γ can suppress Th17 responses and shift cellular responses towards a Th1 bias. We attempted to silence the Th1 response with anti-human IFN-γ antibodies and investigate its effect on IL-17 induction by Aspergillus. As shown in Fig. 4(a,b), although IFN-γ production was effectively inhibited, there was no significant rescue of IL-17 production induced by anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies in the presence of A. fumigatus. Hence, the weak IL-17 response seen in A. fumigatus is not related to its pro-Th1-inducing propensity.

Figure 4.

Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-17 (IL-17) from monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM)/lymphocytes stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads and incremental amounts of Aspergillus fumigatus or Candida albicans (positive control) in the presence of anti-IFN-γ (a, b). *P < 0·05 compared with respective control (white bar) without anti-IFN-γ, n = 6 subjects. Aspergillus: live A. fumigatus conidia, Candida: heat-killed C. albicans blastoconidia (as positive control).

Secreted products from live Aspergillus attenuate IL-17 production

The inhibitory effects of A. fumigatus on the IL-17 response induced by mitogens may be exerted directly through cell–cell contact, or indirectly through products released by Aspergillus. To investigate this, Aspergillus-conditioned medium was added to the activated cells. As observed in Fig. 5(a,b), IL-17 production was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by the conditioned media on which A. fumigatus conidia had grown. The IL-17-attenuating effects induced by Aspergillus-conditioned medium could not be assigned to shed β-glucan or mannan-derivatives from the Aspergillus cell wall, as the addition of laminarin (inhibitor of dectin-1, the β-glucan receptor) and anti-MR antibodies (which block the mannose receptor) did not reverse the effects of the conditioned medium (data not shown).

Figure 5.

(a, b) Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-17 (IL-17) produced by anti-CD3/anti-CD28-stimulated monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM)/lymphocytes over 3 days in the presence of conditioned medium in which the respective concentrations of live Aspergillus fumigatus had previously been grown over 72 hr. *P < 0·05 compared with anti-CD3/anti-CD28-stimulated MDM/lymphocytes in the presence of conditioned medium in which no Aspergillus had been grown (control; first bar), n = 6 subjects. (c) IL-17 production by anti-CD3/anti-CD28-stimulated MDM/lymphocytes over 3 days in the presence of increasing concentrations of kynurenine compared with control (without kynurenine). *P < 0·05 compared with control, n = 6 subjects. Aspergillus: live A. fumigatus conidia, aCD3CD28: anti-CD3/anti-CD28-coated beads.

The tryptophan metabolism pathway has recently been implicated for its role in regulating the Th17 response to fungal infection.32 Tryptophan and kynurenine concentrations were measured in the Aspergillus-conditioned media. Kynurenine concentrations in the Aspergillus-conditioned media were increased (as compared with control) across the concentration range of live A. fumigatus conidia. This correlated with a drop in the concentration of the substrate, tryptophan, in the conditioned medium (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tryptophan and kynurenine levels of conditioned media in which live Aspergillus fumigatus (of incremental concentrations) had been grown over 3 days compared with levels in conditioned medium incubated over 3 days without Aspergillus (RPMI-1640 control)

| Conditioned medium |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live Aspergillus conidia (micro-organisms/ml) |

||||

| RPMI-1640 control | 104 | 105 | 106 | |

| Tryptophan (μm) | 28·38 ± 0·17 | 20·14 ± 4·46 | 18·95 ± 4·10 | 17·98 ± 3·48 |

| Kynurenine (μm) | 0 | 0·12 ± 0·01 | 0·18 ± 0·05 | 0·26 ± 0·04 |

Tryptophan and kynurenine levels were measured using high-performance liquid chromatography. The analysis was performed on three sets of assays and is presented as means ± SD.

The effect of kynurenine was assessed on the IL-17 production induced by anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies. As depicted in Fig. 5(c), kynurenine inhibited IL-17 production in a dose-dependent manner compared with control stimulation.

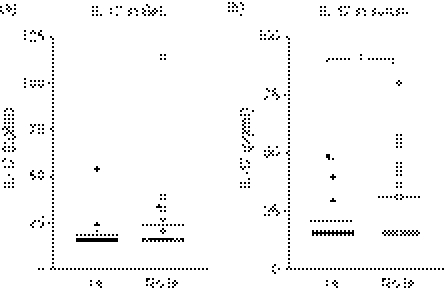

IL-17 concentrations are low in patients with invasive aspergillosis

To assess the capacity of Aspergillus to stimulate Th17 responses in vivo, we measured IL-17 concentrations in clinical specimens of patients with underlying haematological malignancies diagnosed with IA. This consisted of BALs from 17 distinct patients diagnosed with proven/probable IA and another 20 BALs from corresponding control patients without IA (i.e. patients with similar underlying disease, but without IA). The same analysis was performed on the serum of 19 patients with IA (specimen obtained at the point of diagnosis of disease) and also 15 other control patients without IA. As seen in Fig. 6(a), IL-17 levels are generally low in BALs of patients at risk of IA, and not higher than the concentrations found in patients without IA. Similarly, IL-17 concentrations were low in the circulation of patients with IA, and even decreased compared with controls (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6.

(a) Interleukin-17 (IL-17) levels in bronchoalveolar lavage of patients diagnosed with proven/probable invasive aspergillosis (IA) compared with a corresponding patient cohort without IA (No IA): n = 17 in IA group (eight proven IA cases and nine probable IA cases), n = 20 in No IA group. (b) IL-17 levels in serum of IA patients (IA) and corresponding patient controls (No IA): n = 19 in IA group (eight proven IA cases and 11 probable IA cases), and n = 15 in No IA group. *P < 0·05 (unpaired t-test).

Discussion

In the present study we investigated the activation of T-helper cellular responses activated by A. fumigatus. We demonstrate that A. fumigatus induces a very limited Th17 response in humans, both in vitro and in vivo. In contrast, A. fumigatus induces robust stimulation of IFN-γ production, implying that Th1 responses probably represent the cornerstone of T helper-dependent immunity against Aspergillus species.

Few studies have investigated the role of IL-17 in host defence against Aspergillus infection. The studies performed to date involved murine knockout models, and reported contradicting results, with some studies suggesting a deleterious role of IL-17,15,33 whereas others suggested that IL-17 is beneficial for anti-Aspergillus host defence.16 In addition, induction of Th17 cells in humans may differ from that in mice.34,35 No studies have assessed the induction of Th17 responses in human cells. Moreover, patients with IA represent a unique susceptible cohort who have primarily haematological malignancies and are profoundly immunocompromised: being recipients of high-dose, long-term steroid therapy, chemotherapy, stem-cell transplantation and having prolonged agranulocytosis. Such mitigating conditions are difficult to simulate in the above-studied mice models. Therefore, studies in primary human cells are the only viable alternative for the study of Th17 responses in humans. Pulmonary alveolar macrophages form the first line of immune defence against inhaled A. fumigatus conidia. Because host immune responses to live and killed A. fumigatus conidia at the different stadia are known to be different,20,36 and in order to closely mimic the physiological conditions in which the host immune cells encounter the pathogen, the stimulation of MDM/lymphocytes and live A. fumigatus conidia was investigated.

In the present study we report that A. fumigatus is a poor inducer of IL-17 in human cells with both PBMC and in a macrophage/T-cell system. Based on the current understanding of the Th17 activation pathway in other fungal infections such as C. albicans,25 this can be attributed to either the absence of specific memory T cells against A. fumigatus or to a sub-optimal induction of the endogenous cytokines necessary for the induction of a Th17 response (e.g. IL-23, IL-1β, IL-6). However, even mimicking T-cell activation by the use of anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads, as well as adding a ‘pro-Th17 cytokine cocktail’ consisting of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-23,34,37,38 failed to significantly augment IL-17 production in response to Aspergillus.

In contrast to the failure to induce IL-17 production, A. fumigatus induced robust Th1 IFN-γ responses.3,30,39 It has been suggested by some studies that Th1 and Th17 differentiation can be mutually exclusive.10,15 If this would be indeed the case, the strong induction of IFN-γ by Aspergillus, may inhibit the Th17 responses and account for the lack of IL-17 induction in the presence of a predominant Th1 response. However, when we neutralized IFN-γ bioactivity with anti-human IFN-γ antibodies, this failed to stimulate IL-17, arguing for an intrinsic incapacity to stimulate Th17 responses, rather than indirect effects through Th1 induction. Similar to Aspergillus, the inhibition of IFN-γ during stimulation with C. albicans did not up-regulate IL-17 release, arguing against a major role of IFN-γ as a modulator of Th17 responses in fungal infections.

Interestingly, not only was A. fumigatus unable to induce much IL-17 production, it even actively inhibited the IL-17 release induced by mitogenic stimuli such as anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies. The tryptophan metabolism pathway has recently been implicated for its role in regulating the Th17 response to fungal infection.32 Tryptophan can be metabolized by the enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) into the catabolite kynurenine. Kynurenine and IDO have been shown to inhibit Th17 differentiation in mice;33 IDO is also involved in modulation of Th1 differentiation.40,41 Interestingly, A. fumigatus also possesses an IDO-family enzyme,42 and we show that A. fumigatus can induce metabolization of tryptophan into kynurenine. We investigated whether kynurenine is able to modulate Th17 also in human cells, and we have observed inhibitory effects. Therefore, it seems rational to hypothesize that the observed inhibitory effect of A. fumigatus on the induction of IL-17 is at least in part mediated through its effects on tryptophan metabolites, via the generation of the inhibitory product kynurenine. However, besides kynurenine, we cannot exclude that additional factors may also mediate inhibition of Th17 induction by Aspergillus. Nonetheless, in our hands, these additional IL-17-modulating effects were probably not linked to innate signalling via the macrophage mannose receptor 43 or dectin-1 β-glucan receptor.16

The importance of IL-17 in the pathogenesis of invasive aspergillosis remains to be proven. Recently it has been reported that IL-17 receptor-deficient mice, despite an initially elevated fungal burden, were eventually able to efficiently control aspergillosis.44 This raises the question on the perceived non-redundancy of IL-17. From the clinical perspective, patients with hyper-IgE syndrome are known to be deficienct for Th17 cells because of mutations in signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT-3)45,46 and are susceptible to secondary Aspergillus infection of pneumatoceles, but not to primary invasive aspergillosis.47 Although colonization of pneumatocoeles with Aspergillus in hyper-IgE syndrome patients would seemingly support the notion of a protective role of IL-17 against fungal infections, one will need to keep in mind that the pathogenic mechanism behind an ‘opportunistic colonization’ of a lung cavity in a patient with hyper-IgE is perceivably distinct from that of invasive aspergillosis in a bone marrow transplant patient. Therefore, the clinical picture in Th17-defective patients with hyper-IgE syndrome does not dispute the notion that Th17 responses may not be essential in the host defence against invasive aspergillosis.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that A. fumigatus is a poor inducer of the IL-17 response in humans, and this may be at least partly attributable to the pathogen’s ability to metabolize tryptophan and secrete kynurenine which, in turn, down-regulates the Th17 pathway. The importance of IL-17 in the pathogenesis of invasive aspergillosis remains therefore in question, as the Th1 response is likely to be the predominant T helper-dependent immunity mounted by the host against Aspergillus species. It is hence difficult to envisage a dominant role for IL-17 in host defence against Aspergillus at this juncture.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Peter Troke, June Kwon-Chung and Janyce Sugui for providing study specimens. L.C. was supported by the Health Manpower Development Plan (HMDP) Fellowship, Ministry of Health, Singapore and the International Fellowship, Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR)/National Medical Research Council (NMRC), Singapore. M.G.N. was supported by a Vidi grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

Disclosures

The authors have no potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Patterson TF, Kirkpatrick WR, White M, et al. Invasive aspergillosis. Disease spectrum, treatment practices, and outcomes. Aspergillus Study Group. Medicine (Balt) 2000;79:250–60. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200007000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denning DW. Invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:781–803. doi: 10.1086/513943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevens DA. Th1/Th2 in aspergillosis. Med Mycol. 2006;1:229–35. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romani L. Immunity to Candida albicans: Th1, Th2 cells and beyond. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:363–7. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chai LY, Netea MG, Vonk AG, Kullberg BJ. Fungal strategies for overcoming host innate immune response. Med Mycol. 2009;47:227–36. doi: 10.1080/13693780802209082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Netea MG, Van der Meer JW, Sutmuller RP, Adema GJ, Kullberg BJ. From the Th1/Th2 paradigm towards a Toll-like receptor/T-helper bias. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3991–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.10.3991-3996.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Turner H, Murphy TL, Murphy KM, Weaver CT. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1123–32. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bettelli E, Korn T, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. Induction and effector functions of Th17 cells. Nature. 2008;453:1051–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Awasthi A, Kuchroo VK. Th17 cells: from precursors to players in inflammation and infection. Int Immunol. 2009;21:489–98. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong C. Th17 cells in development: an updated view of their molecular identity and genetic programming. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:337–48. doi: 10.1038/nri2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolls JK, Linden A. Interleukin-17 family members and inflammation. Immunity. 2004;21:467–76. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang W, Na L, Fidel PL, Schwarzenberger P. Requirement of interleukin-17A for systemic anti-Candida albicans host defense in mice. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:624–31. doi: 10.1086/422329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romagnani S, Maggi E, Liotta F, Cosmi L, Annunziato F. Properties and origin of human Th17 cells. Mol Immunol. 2009;47:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romagnani S. Human Th17 cells. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10:206. doi: 10.1186/ar2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zelante T, De Luca A, Bonifazi P, et al. IL-23 and the Th17 pathway promote inflammation and impair antifungal immune resistance. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2695–706. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werner JL, Metz AE, Horn D, et al. Requisite role for the dectin-1 β-glucan receptor in pulmonary defense against Aspergillus fumigatus. J Immunol. 2009;182:4938–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Netea MG, Warris A, Van der Meer JW, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus evades immune recognition during germination through loss of toll-like receptor-4-mediated signal transduction. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:320–6. doi: 10.1086/376456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chai LY, Kullberg BJ, Vonk AG, et al. Modulation of Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR4 responses by Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect Immun. 2009;77:2184–92. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01455-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai HF, Chang YC, Washburn RG, Wheeler MH, Kwon-Chung KJ. The developmentally regulated alb1 gene of Aspergillus fumigatus: its role in modulation of conidial morphology and virulence. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3031–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3031-3038.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gersuk GM, Underhill DM, Zhu L, Marr KA. Dectin-1 and TLRs permit macrophages to distinguish between different Aspergillus fumigatus cellular states. J Immunol. 2006;176:3717–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gow NA, Netea MG, Munro CA, et al. Immune recognition of Candida albicansβ-glucan by dectin-1. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1565–71. doi: 10.1086/523110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehrer RI, Cline MJ. Interaction of Candida albicans with human leukocytes and serum. J Bacteriol. 1969;98:996–1004. doi: 10.1128/jb.98.3.996-1004.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Netea MG, Gow NA, Munro CA, et al. Immune sensing of Candida albicans requires cooperative recognition of mannans and glucans by lectin and Toll-like receptors. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1642–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI27114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferwerda G, Meyer-Wentrup F, Kullberg BJ, Netea MG, Adema GJ. Dectin-1 synergizes with TLR2 and TLR4 for cytokine production in human primary monocytes and macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2058–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van de Veerdonk FL, Marijnissen RJ, Kullberg BJ, et al. The macrophage mannose receptor induces IL-17 in response to Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:329–40. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, et al. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:408–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1813–21. doi: 10.1086/588660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zucchelli GC, Pilo A, Chiesa MR, Cohen R, Bizollon CA. Analytical performance of free PSA immunoassays: results from an interlaboratory survey. Clin Chem. 1997;43:2426–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krstulovic AM, Friedman MJ, Colin H, Guiochon G, Gaspar M, Pajer KA. Analytical methodology for assays of serum tryptophan metabolites in control subjects and newly abstinent alcoholics: preliminary investigation by liquid chromatography with amperometric detection. J Chromatogr. 1984;297:271–81. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)89048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rivera A, Ro G, Van Epps HL, Simpson T, Leiner I, Sant’Angelo DB, Pamer EG. Innate immune activation and CD4+ T cell priming during respiratory fungal infection. Immunity. 2006;25:665–75. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zelante T, Bozza S, De Luca A, et al. Th17 cells in the setting of Aspergillus infection and pathology. Med Mycol. 2009;47(Suppl. 1):S162–9. doi: 10.1080/13693780802140766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romani L, Zelante T, De Luca A, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) in inflammation and allergy to Aspergillus. Med Mycol. 2009;47(Suppl. 1):S154–61. doi: 10.1080/13693780802139867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romani L, Zelante T, De Luca A, Fallarino F, Puccetti P. IL-17 and therapeutic kynurenines in pathogenic inflammation to fungi. J Immunol. 2008;180:5157–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Napolitani G, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Interleukins 1β and 6 but not transforming growth factor-β are essential for the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing human T helper cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:942–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Z, Tato CM, Muul L, Laurence A, O’Shea JJ. Distinct regulation of interleukin-17 in human T helper lymphocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2936–46. doi: 10.1002/art.22866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steele C, Rapaka RR, Metz A, Pop SM, Williams DL, Gordon S, Kolls JK, Brown GD. The β-glucan receptor dectin-1 recognizes specific morphologies of Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:e42. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koenen HJ, Smeets RL, Vink PM, van Rijssen E, Boots AM, Joosten I. Human CD25highFoxp3+ regulatory T cells differentiate into IL-17-producing cells. Blood. 2008;112:2340–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-133967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson NJ, Boniface K, Chan JR, et al. Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:950–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hebart H, Bollinger C, Fisch P, et al. Analysis of T-cell responses to Aspergillus fumigatus antigens in healthy individuals and patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2002;100:4521–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu H, Oriss TB, Fei M, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in lung dendritic cells promotes Th2 responses and allergic inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6690–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708809105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kong QF, Sun B, Wang GY, et al. BM stromal cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis by altering the balance of Th cells through the secretion of IDO. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:800–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanehisa Laboratories UoK, Japan . Tryptophan metabolism –Aspergillus fumigatus. Kyoto: Kanehisa Laboratories UoK; 2009. Vol. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 43.LeibundGut-Landmann S, Gross O, Robinson MJ, et al. Syk- and CARD9-dependent coupling of innate immunity to the induction of T helper cells that produce interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:630–8. doi: 10.1038/ni1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zelante T, De Luca A, D’Angelo C, Moretti S, Romani L. IL-17/Th17 in anti-fungal immunity: what’s new? Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:645–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holland SM, DeLeo FR, Elloumi HZ, et al. STAT3 mutations in the hyper-IgE syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1608–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma CS, Chew GY, Simpson N, et al. Deficiency of Th17 cells in hyper IgE syndrome due to mutations in STAT3. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1551–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Freeman AF, Holland SM. The hyper-IgE syndromes. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2008;28:277–91. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]