Abstract

In the cycle of photosynthetic reaction centers, the initially oxidized special pair of bacteriochlorophyll molecules is subsequently reduced by an electron transferred over a chain of four hemes of the complex. Here, we examine the kinetics of electron transfer between the proximal heme c-559 of the chain and the oxidized special pair in the reaction center from Rps. sulfoviridis in the range of temperatures from 294 to 40 K. The experimental data were obtained for three redox states of the reaction center, in which one, two, or three nearest hemes of the chain are reduced prior to special pair oxidation. The experimental kinetic data are analyzed in terms of a Sumi–Marcus-type model developed in our previous paper,1 in which similar measurements were reported on the reaction centers from Rps. viridis. The model allows us to establish a connection between the observed nonexponential electron-transfer kinetics and the local structural relaxation dynamics of the reaction center protein on the microsecond time scale. The activation energy for relaxation dynamics of the protein medium has been found to be around 0.1 eV for all three redox states, which is in contrast to a value around 0.4–0.6 eV in Rps. viridis.1 The possible nature of the difference between the reaction centers from Rps. viridis and Rps. sulfoviridis, which are believed to be very similar, is discussed. The role of the protein glass transition at low temperatures and that of internal water molecules in the process are analyzed.

1. Introduction

Biological electron-transfer (ET) reactions are very sensitive to the conformational state of the protein in which they occur. The protein conformational dynamics, therefore, if it occurs on the time-scale comparable to that of the electron transfer or slower, can affect or even control the kinetics of the ET reaction. This can lead to the effects such as conformational gating2,3 or nonexponential kinetics.1

Numerous examples of the reactions whose rates are modulated by slow medium reorganization have been found experimentally; for example, see refs 4–14. Several theoretical approaches have been developed to model such reactions (see excellent review by Cherepanov et al.15). However, because of practical difficulties, the theory has rarely been used to extract information on the medium dynamics from any particular experimental data. A few examples of such approach are described in refs 10–12 and 15.

For example, Nienhaus and co-workers10–12 measured the kinetics of a relatively slow reaction (10−1−10−2 s) of electron transfer from the primary quinone to the special pair of the photosynthetic bacterial reaction center from Rb. sphaeroides. They applied the spin-boson model and the maximum entropy method to describe the observed kinetics in terms of rate distributions,16 which enabled them to obtain valuable information on the relaxation processes in a wide range of temperatures. In particular, they found that relaxations did not stop below the glass transition temperature, with characteristic times ranging from 10−1 to 104 s.

Cherepanov et al.15 applied the stochastic Langevin equation to model the oscillating subpicosecond kinetics of the primary charge separation in the reaction center from Rb. sphaeroides. For the slower reactions of electron transfer from the prereduced cytochrome or primary quinone to the oxidized special pair in the reaction centers from Rps. viridis and Rb. sphaeroides, respectively, Cherepanov et al. derived relations expressing the amplitudes of the initial fast nonadiabatic portion of the observed kinetics and the slow kinetics governed by the medium reorganization in terms of the driving force and the energy of slow reorganization, which enabled them to estimate the latter from the experimental data. However, the kinetics of these reactions on the microsecond and longer time scales were not modeled, probably because of the impossibility to run a large number of stochastic trajectories over such long periods of time.

Theoretical analysis of the microsecond reaction of electron transfer from proximal heme c-559 to the oxidized bacteriochlorophyll dimer in the reaction center from the photosynthetic bacterium Rps. viridis has been described in our previous paper of this series,1 where we developed an approach based on the diffusion-reaction equation.17–27 This approach enabled us to explore the protein dynamics on the microsecond time scale, which is intermediate between the time scales studied in the above-cited works. To the best of our knowledge, the diffusion-reaction equation has never been used previously to derive the characteristic relaxation time of a protein from experimental data on the kinetics of an ET reaction.

Recently, the diffusion-reaction equation was applied in the analysis of experimental data on the kinetics of the initial charge separation in the wild type and mutant reaction centers from Rb. sphaeroides.13,14 However, the protein relaxation characteristics were obtained in that study from independent of ET measurements, namely, from time-dependent tryptophan absorption spectroscopy. It was shown that the initial charge separation in the reaction center developing on the picosecond time scale is controlled by protein dynamics.

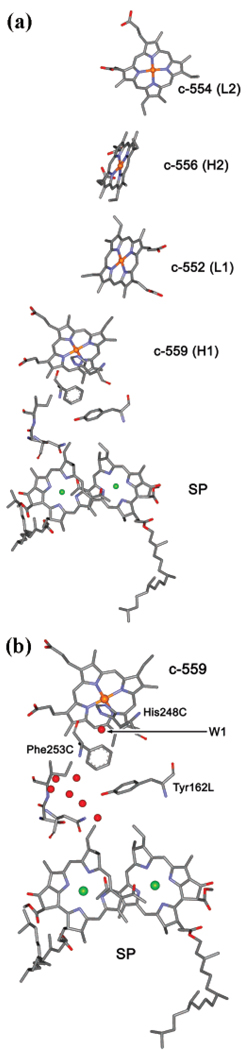

In the present paper, we report on the experimental measurements and theoretical analysis of the kinetics of electron transfer in the reaction centers from Rps. sulfoviridis, a species closely related to Rps. viridis from our previous study. We apply our method to treat experimental data and to deduce from it information on the protein dynamics. Unfortunately, the structure of the reaction center from this bacterium has not been resolved yet; however, it is believed that it should closely resemble that of the reaction center from Rps. viridis. In Figure 1, the main redox components involved in electron transfer in Rps. viridis are shown; they include the special pair (SP) and four hemes, of which two are high potential hemes (H1, H2) and two are low potential hemes (L1, L2). The high potential hemes are also labeled here as c-559 (H1) and c-556 (H2), while the low potential hemes are designated as c-552 (L1) and c-554 (L2).

Figure 1.

(a) The structure of redox components of electron-transfer chain discussed in this paper: the special pair (SP) and four hemes. H1 and H2 are two high-potential hemes, L1 and L2 are two low-potential hemes. The electron transfer between the proximal heme, c-559, and oxidized SP is considered in detail in this paper for three redox states of the system: In state 1, c-559 (H1) is reduced; in state 2, c-559 (H1) and c-556 (H2) are reduced; and in state 3, c-559 (H1), c-552 (L1), and c-556 (H2) are reduced prior to oxidation of SP. The actual structure shown is that of the reaction center from Rps. viridis (PDB code, 1PRC), which is believed to be closely related to that of Rps. sulfoviridis studied in this paper. (b) Internal water molecules in Rps. viridis structure between heme c-559 and SP. One water molecule W1 (HOH38) is H bonded to His ligand of heme c-559 and to the backbone of the nearby Phe residue and therefore can have a particularly strongly effect on the ET reaction. Also shown is a small part of the backbone stretching between Phe253C and SP, which might work as a wire for electron tunneling, c-559 → His248C → W1 → Phe253C → backbone → SP, in addition to the most likely ET pathway, c-559 → His248C → W1 → Phe253C → Tyr162L → SP.

Midpoint redox potentials of hemes in Rps. sulfoviridis and Rps. viridis (data for the latter are in parentheses) are equal to H1, +390 (+380); H2, +310 (+310); L1, +40 (+20); and L2, −40 (−60) mV.28 The redox potential of oxidized SP in Rps. viridis is +520 mV.6

The measurements were performed at three levels of the medium redox potential: Eh = +360 mV (state 1 of the enzyme), Eh = +250 mV (state 2), and Eh = −20 mV (state 3). Thus, in state 1, only heme H1 is reduced; in state 2, hemes H1 and H2 are reduced; and in state 3, hemes H1, H2, and L1 are reduced before the electron-transfer reaction is initiated; the electron transfer is initiated by photoejecting the electron from SP, and we study the process of its reduction in states 1, 2, and 3.

2. Experimental Procedures

Cultures of Rhodopseudomonas sulfoviridis cells were grown and reaction centers were prepared according to Verméglio et al.28 Purified reaction centers were handled as described by Ortega and Mathis5 for Rps. viridis. The RC concentration was determined spectrophotometrically using the value ε = 300 mM−1 cm−1 at 830 nm.29

The redox potential of the medium was measured with a platinum electrode versus a Calomel reference electrode. The solution potential was varied by additions of ferricyanide and ascorbate.

For spectroscopic measurements at high redox potential (Eh about +360 mV), samples were prepared with 2 µM reaction centers in 40 mM Tris-buffer (pH 8.0) and the redox mediators diaminodurene (100 µM), vitamine K3 (100 µM), N,N′-phenilenediamine (50 µM), and ferricyanide (approximately 100 µM). At moderate redox potential (Eh about +250 mV), samples were prepared with 2 µM reaction centers in 40 mM Tris-buffer (pH 8.0) and 100 µM of the redox mediators diaminodurene, vitamine K3, and ascorbate. For spectroscopic measurements at low redox potential (Eh about −20 mV), samples were prepared with 2 µM reaction centers in 40 mM Tris-buffer (pH 8.0) and 100 µM of the redox mediators diaminodurene, duroquinone, vitamine K3, and 2,5-dihydroxi-p-benzoquinone. After degassing the sample for 15 min, solid ascorbate was added to an approximate final concentration of 30 mM prior to another degassing for the same time period. For low-temperature measurements under the three redox conditions above-described, glycerol was added to the reaction mixture to a final concentration of 60% (v/v).

The flash absorption kinetics of the electron transfer from cytochrome to P+ were measured by following the P+ absorbance changes essentially as in ref 5. To measure the P+ formation and re-reduction, we used a CW-laser diode emitting at 1283 nm where P+ has a broad absorption band peaking around 1320 nm and where P has no absorption, a feature which avoids any actinic effect of the measuring light. The cuvette was excited by short flashes (10 ns, 694 nm) provided by a ruby laser. The measuring light was focused through the cuvette onto a germanium photodiode (Ø = 0.1 mm), the output of which was amplified and measured with transient digitizer. When needed (i.e., for measurements at 1283 nm at low temperature), the 2048 channels of the memory were grouped with different times/channel in order to cover an appropriate span with enough time resolution. The time resolution of the measurements was 40 ns. The good signal-to-noise ratio allowed us to obtain single-turnover traces of sufficient quality without averaging. The cuvette, with optical paths of 10 mm for the measuring light and 4 mm for excitation, was inserted in a cryostat cooled with helium gas (250 to 7 K) or with a thermostated water–ethylene glycol mixture (305–240 K). Measurements below 243 K are the result of a single flash given to a dark-adapted (2 min at room temperature) sample cooled in darkness. At higher temperature, the measurements are the average of 4 single flashes, with time spacing sufficient to allow a return to equilibrium (1 to 5 min).

The data were acquired as described by Ortega and Mathis5 and analyzed using the model described below.

3. Model

The model that we use here is essentially the same as in our previous study on Rps. viridis, and was discussed in detail in ref 1. Briefly, the conformational state of the protein relevant to the ET reaction is described by a phenomenological generalized coordinate X; for X we introduce a time-dependent probability distribution, P(X;t); we assume that X has a thermal equilibrium value 〈X〉, and its dynamics can be described as diffusive motion around its equilibrium value. The equilibrium value 〈X〉 (taken to be zero in the reagents state) is determined by the minimum of the free energy profile of X; in the vicinity of its minimum, the free energy profile V(X) is assumed to be harmonic. The distribution P(X;t) obeys the classical diffusionreaction equation,

| (1) |

where V(X) = (1/2)X2 is the harmonic (free energy) potential along the diffusive X coordinate in the reagents state, and τ is the relaxation time of X, one of the key parameters of the model. The ET reaction can occur at any value X; however, the reaction rate strongly depends on the conformational state of the protein X. The reaction is described by the last term in the above equation, and the rate k(X) at a given X is taken to be

| (2) |

which depends in a familiar way on the electron-transfer matrix element, HDA, on the driving force ΔG(X), which is a function of the conformational state of the protein X, and on two reorganization energies, λ1 and λ2.

The above formula looks like a standard classical ET rate expression, but in fact it takes into account quantum effects by introducing two reorganization energies, λ1 and λ2. This formula was derived by Lee et al.30 using a model in which the vibrational dynamics of the protein is described by one quantum and one classical effective harmonic oscillators characterized by their respective frequencies and reorganization energies, ωq,λq and ωcl,λcl. The expressions for λ1 and λ2 are

| (3) |

Equation 2 is of course an approximation, but a good one, which works well in a vide range of ΔG around the maximum of the rate. The relation of eq 2 and eq 3 to the familiar Jortner formulation31 is discussed in detail by Lee et al.30 Mainly, the approximation of eq 2 and eq 3 neglects the asymmetry (with respect to the maximum) of the log rate versus ΔG dependence present in (exact) Jortner’s formula.

The validity of the reaction-diffusion eq 1 is restricted, first, by the requirement that the conformational dynamics along the X coordinate be classical in the whole temperature range where it is applied. In particular, the dynamics should be classical at least above the glass transition temperature, which imposes the limitation on the X mode frequency, ℏωX ≪ 2kBTg (in this limit, ωX does not enter the theory explicitly). Second, eq 1 assumes a single relaxation time whereas the spectrum of relaxation times in proteins is known to be very wide, from picoseconds to seconds, so that in general there are conformational motions with widely varying relaxation times. Obviously, those motions whose times are short on the time-scale of the electron transfer under study are in thermal equilibrium, and those with long relaxation times are “frozen” during the ET reaction. Both rapid and slow modes define the state of the reaction center and its environment, that is, the static parameters governing the electron transfer, such as the driving force and reorganization energy. Only those modes whose relaxation times are in the range of the characteristic ET time actually affect the kinetics of the ET reaction. Yet, there may be quite a few such modes rather than a single one. Taking this fact into account would make the theory intractable, however. Instead, we describe all possible motions by a single coordinate and derive information on its relaxation time, which thereby represents some average, “effective” relaxation time characteristic of the process under study.

The dependence of ΔG on the conformational coordinate X is written as

| (4) |

where ΔG0 is the free energy of the reaction, X0 is the shift of equilibrium upon electron transfer, and is the reorganization energy associated with conformational coordinate X. The above expression is written in a standard way treating X as a classical harmonic oscillator coupled to the electron-transfer reaction.

Thus, our model contains six “static” temperature-independent parameters,32

| (5) |

and one structural dynamics parameter, τ, which depends on temperature, T. The quantity measured in experiment is the survival probability of the initial state,

| (6) |

The above theory allows us to calculate the survival probability Q(t) and directly compare it with experimental data. Our goal is to use experimental kinetic data on the reaction at various conditions in order to extract information about the relaxation dynamics parameter τ (along with the static parameters of the model, which, however, are of a lesser interest, see below).

At temperatures where the structural diffusion is much slower or much faster than the reaction, the survival probability, Q(t), for the initial reactant state is independent of τ; the experimental data for such conditions will be used for determining the static parameters (5). The theoretical expressions for survival probability in the limits of slow and fast diffusion are given by25

| (7) |

and

| (8) |

respectively, where

| (9) |

is the average reaction rate over all conformational states and

| (10) |

is the initial equilibrium distribution of the conformational states.33 As one can see, in this case, the ET kinetics does not depend on the conformational dynamic parameters, and one does not need to solve the diffusion eq 1. The harmonic form of the conformational potential assumed in eq 10 is approximately valid near the free energy minimum,34 that is, at equilibrium, where the system is initially prepared.

When the diffusion rate of X is comparable with the ET rate, the reaction is controlled by the dynamics of X. In this case, the kinetics of the ET reaction is nonexponential. In order to obtain theoretical values of the survival probability Q(t) in this case, the diffusion-reaction equation is solved numerically. With the static parameters determined as described above, the only parameter to fit the experimental kinetics is τ; the nonexponential kinetics at various temperatures allows for determination of τ as function of temperature. This function is represented in the Arrhenius form,

| (11) |

where Ea is the activation energy for dipole reorientation and is the frequency prefactor. The details of the fitting procedure are given in ref 1.

4. Results

The overall reaction is initiated by a laser pulse that creates a charge-separated state, P+QA−, in which P is oxidized, with its electron transferred to QA. The subsequent reduction of P+, at various levels of the initial reduction of hemes H1-L2 (see Figure 1) is monitored in the experiment.

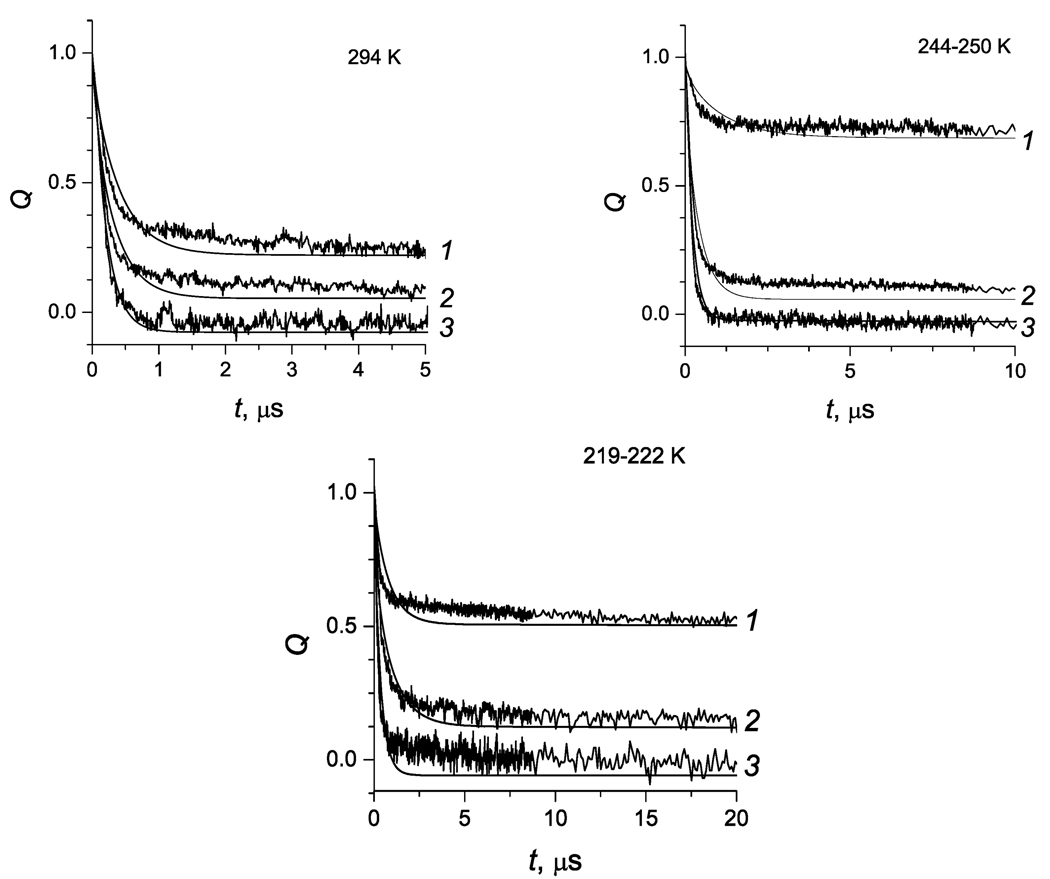

The reaction kinetics observed in this study for reaction centers from Rps. sulfoviridis are similar to those of Rps. viridis described in refs 4 and 5. Typical kinetic curves are shown in Figure 2. The initial decay of the population of oxidized P occurs on the microsecond time scale and is ascribed to the electron transfer from the proximal heme c-559 to P+; see Figure 1. The kinetics of this phase is nonexponential at all temperatures. This reaction occurs only in a fraction f of the initially prepared P+ state of the enzyme. The remaining fraction (1 − f) of the oxidized P, which appears as a plateau on the time-scale shown in Figure 2, is reduced on the millisecond time scale35 because of back electron transfer from QA−. The fraction f depends on the experimental conditions, for example, redox state of the enzyme and temperature; see Figure 2. For a discussion of such assignment and experimental support, see refs 4, 5, and 36–39.

Figure 2.

Survival probability as a function of time for states 1, 2, and 3. Solid lines, fittings with parameters from Table 2. State 3 is displaced down by 0.1 for clarity.

As noted above, the c-559 to P+ reaction occurs only in a fraction of the initially prepared P+ population, even at room temperature. We consider two possible reasons for such behavior. First, a fraction of the reaction centers may have c-559 oxidized before the initial laser flash.5 This is likely the case for state 1, in which the redox potential of the medium (Eh = +360 mV) is close to the midpoint potential of c-559 (Em = +390 mV). Second, as suggested in ref 1, the reaction itself appears to be arrested (or significantly slowed down) in a fraction of the reaction centers. We call this fraction “the slow population” of the ensemble. A possible reason for the slow ET reaction between c-559 and P+ in a fraction of the enzymes was proposed1 to be due to partial protonation of an unknown group located in a vicinity of c-559, which either modulates redox potential of c-559 or forms H bonds with a water molecule(s) and hinders the dipole reorientations in the protein, and thus hinders the ET reaction.1 Such a possibility is further examined in the present study below. Both the slow population and the c-559-oxidized fractions of the enzyme are contributing to QA− to P+ back reaction, which forms the millisecond (very slow, VS) phase of the observed kinetics.

Determination of the Parameters of the Slow Population

In order to treat the kinetics of the c-559 to P+ reaction, we have first to remove the contribution of the back ET reaction, from the experimental kinetic curves. The procedure is described in ref 1. The total amplitude of the VS component can be written as a sum of two terms,

| (12) |

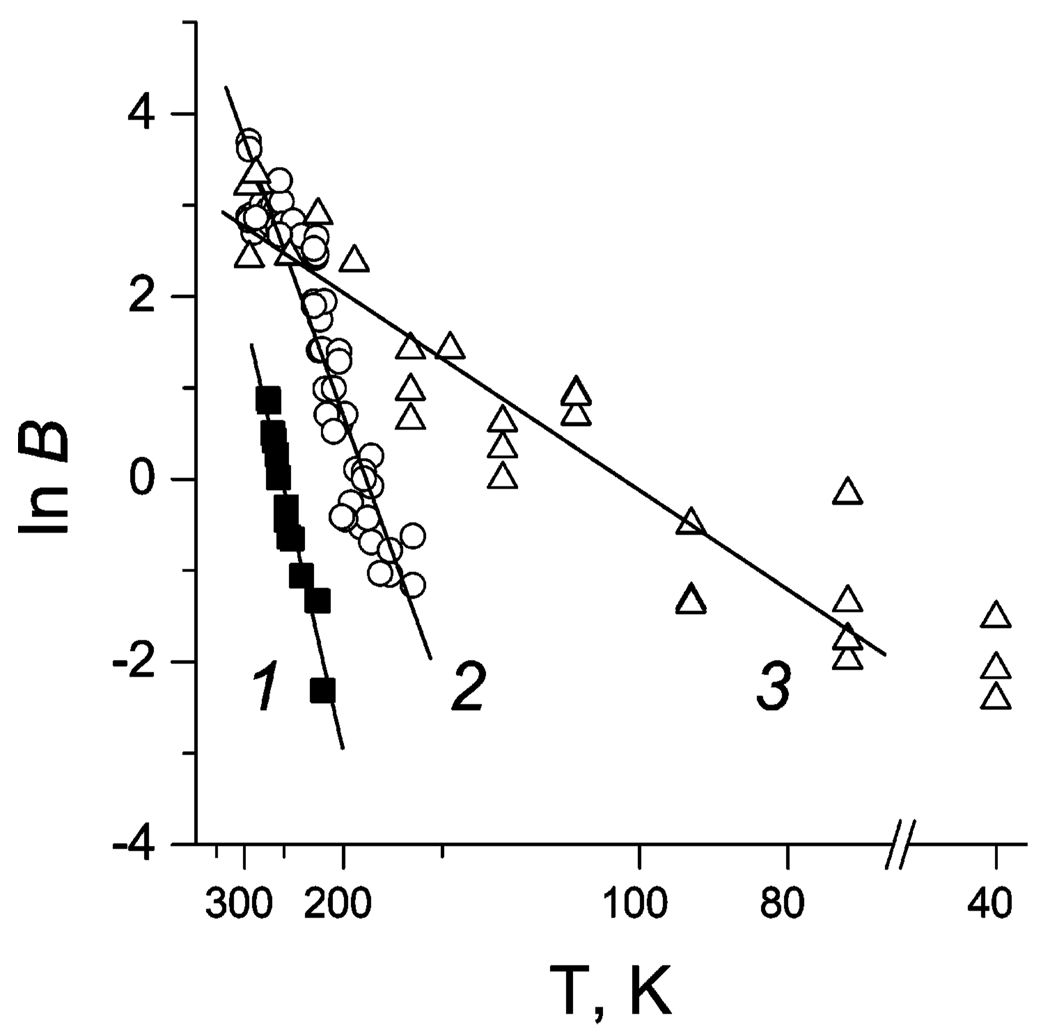

where the first term, A′s, is the relative population of the reaction centers with c-559 oxidized and the second one, As, represents the slow population; ΔS and ΔE are changes in entropy and energy between the deprotonated and protonated states of the group responsible for the reaction arrest in the slow population. Figure 3 shows the plot of

| (13) |

as a function of inverse temperature for three states of reduction.40

Figure 3.

Plot of experimental values of ln B, eq 13, as a function of inverse temperature for three states of reduction. Filled squares, state 1; open circles, state 2; open triangles, state 3. Lines, least-squares fits to determine ΔS and ΔE. Three points at T = 40 K were not accounted for in the state 3 fitting.

The values of ΔS and ΔE found from the intercepts and slopes of the straight lines are summarized in Table 1, where the values of pKa for the protolytic group responsible for the arrest of the dipole reorientation calculated by the equation

| (14) |

at pH 8 and T = 294 K are also given. The value of pKa depends on the state of reduction, which may indicate that the protolytic group is located in a vicinity of the cytochrome. We should note that at present there is no direct evidence that the conformational gating indeed arises from a protonation event. The above results show, however, that this possibility cannot be excluded.

TABLE 1.

Parameters Found from Linear Fits to the Experimental Data in Figure 3

| state | ΔE, meV | ΔS, meV/K | pKa |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 250 | 0.98 | 7.3 |

| 2 | 160 | 0.84 | 6.4 |

| 2a | 190 | 1.0 | 6.0 |

| 3 | 37 | 0.36 | 6.8 |

Data for Rps. Viridis.1

Determination of the Static Parameters

In the case of Rps. viridis, the static parameters, eq 5, were determined from the low- and high-(room) temperature data where the respective kinetics approximately corresponded to the slow and fast diffusion limits, eq 7 and eq 8, where the kinetics is independent of the dynamic parameter τ. However, as we will see below, this is not the case for Rps. sulfoviridis. In fact, now we find that the experimental kinetic curves correspond neither to slow nor to fast diffusion at all temperatures. As in ref 1, we used variable sets of static parameters in order to define τ(T) and to ensure that the final result, that is, the activation energy for protein relaxation, is not very sensitive to the specific choice of the static parameters provided that the experimental kinetic curves are fitted satisfactorily.

The parameters used in the fittings are given in Table 2 along with the ones for state 2 in Rps. viridis. As explained in ref 1, the model does not permit determination of a unique set of the static parameters since the fits to the experimental kinetic curves were of comparable quality for various sets of parameters. For instance, ωq only weakly affected the fits and was set equal to 800 cm−1 in all cases; ΔG0 entered only in a combination with other parameters, so that a limited change in ΔG0 could be compensated by reasonable changes in other parameters without worsening the quality of the fit. Therefore, Table 2 only roughly represents the actual physical properties of the protein system under study. It is worth mentioning that a large contribution of the classical modes to the reorganization energy was noted in ref 1 for Rps. viridis; this trend is also maintained in Rps. sulfoviridis.

TABLE 2.

Static Parameters of the Model in Centimeter− 1 (1 meV ≈ 8 cm−1)

| state | HDA | ΔG0 | ωq | λq | λcl | λX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.3 | −1130 | 800 | 70 | 1570 | 1880 |

| 2 | 0.25 | −1450 | 800 | 80 | 1750 | 1630 |

| 2a | 2.2 | −1100 | 800 | 280 | 6180 | 720 |

| 3 | 0.3 | −2340 | 800 | 130 | 2770 | 2060 |

Data for Rps. Viridis.1

The robustness of the model parameters derived from the experiment deserves special discussion because it relates to reliability of the obtained results. The theory contains six static temperature-independent parameters shown in Table 2 and one dynamic parameter, the relaxation time τ, which is a function of temperature. At first glance it may seem that the number of parameters is so large that fitting experimental curves is always possible. In fact, however, this is not true, given some peculiarities of the theory.

First, the theory actually contains only four independent combinations of the six static parameters (see ref 1); hence, only these combinations affect the fitting results. Thus, varying the six original parameters while keeping the four independent combinations unchanged does not affect the calculated curves. Hence, all six parameters cannot be determined in principle, given there are only four independent combinations. The data shown in Table 2 were obtained by fixing ΔG0 at the values calculated by Frolov et al.41 for Rps. viridis, and fixing ωq at a reasonable but otherwise arbitrarily selected value 800 cm−1. If ΔG0 and ωq were different, the reorganization energies and the coupling matrix element would be different too. Therefore, one cannot assign all of these parameters independent specific values. Yet, one still can make some qualitative conclusions about the reaction center based on this model. For instance, as mentioned above, the large reorganization energy of classical modes seems to be a common feature of both Rps. viridis and Rps. sulfoirids.

Second, two of the four independent combinations of parameter could be directly found from the initial (i.e., at t = 0) slopes of the experimental curves at T = 294 and 193 K. The other two combinations were therefore the only two freely variable static parameters.

Third, the set of static parameters was selected only once and then was used for all three states of reduction and all temperatures above Tg; that is, the total of more than 50 experimental curves were fitted with a common set of static parameters. The only parameter that was varied to fit each experimental curve individually was the relaxation time τ. In this way, the function τ(T) was obtained, which is the main result of the present study to be discussed later.

The following aspects of the curve fitting procedure are also relevant to the above discussion. After the removal of the contribution of the slow population, the kinetics of the fast population shown in Figure 2 consists in its turn of the fast and slow components. Both components are assumed to be due to a single process in which electron transfer occurs at incomplete medium relaxation. The initial (short-time kinetic component) SP reduction occurs in such conformations X for which the rate constant k(X) is largest. This leads to a quick depletion of the fast population of the initial distribution in X and to slowing down the ET reaction (long-time component) due to incomplete equilibration between the fast and the slow populations. It is impossible to fit both the short-time and the long-time components of the kinetic curves equally well, because changing any parameter affects both components simultaneously. Therefore, one has to balance the qualities of the fitting at short and long times. The results of such balanced fitting are shown in Figure 2, where some moderate deviation of the theoretical curves from the respective experimental curves occurs both at short and long times.

The above considerations show that there are limitations on the ability of the theory to extract precise values of τ from experimental data on the ET kinetics. Our approach assumes that the τ values calculated from numerous experimental curves at various temperatures will permit us to determine some statistically meaningful effective activation energy for the dipole reorientation in the protein, which in turn will provide a basis to discuss a possible mechanism of this process and compare with similar data obtained for Rps. viridis.

Fitting the Experimental Kinetic Curves

The fittings for three temperatures are shown in Figure 2.

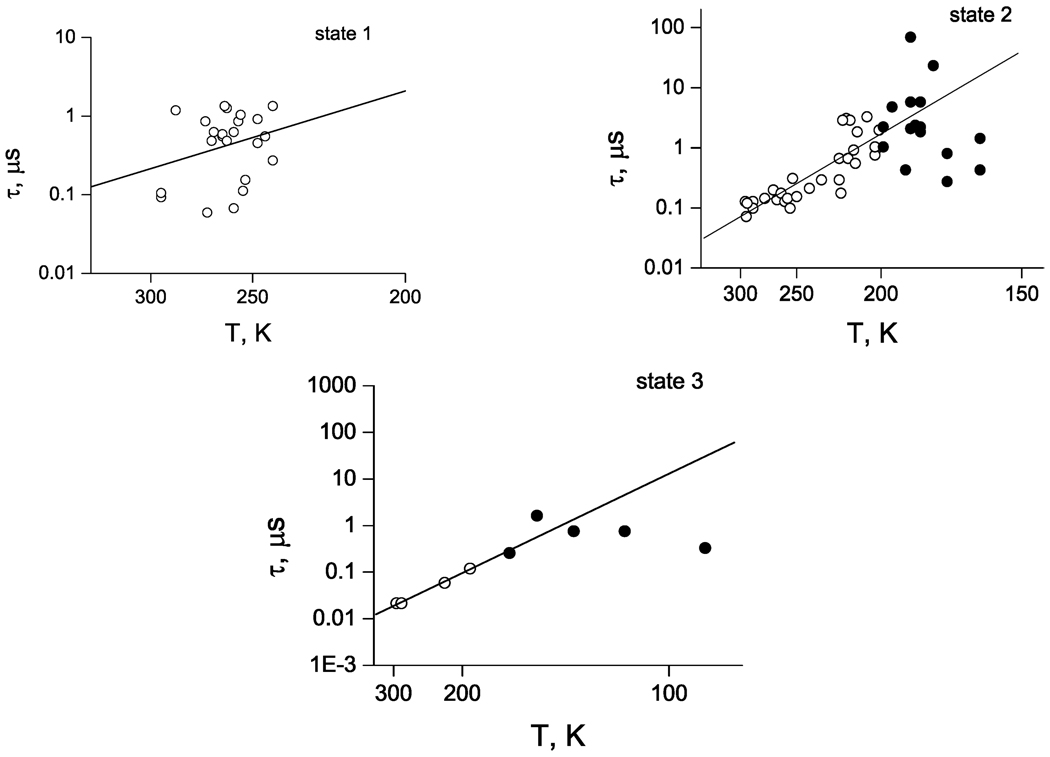

For all three redox states of the enzyme, we used one and the same set of static parameters shown in Table 2, whereas τ was an adjustable parameter to fit each experimental curve individually. In this way, the values of τ were found for all states of reduction and for several different temperatures in a wide range, as shown in Figure 4. Open circles in Figure 4 are data for temperatures above the glass transition temperature Tg; the lines are the least-squares fits. The values for τ could be also found below Tg. These data are shown in Figure 4 by filled circles for states 2 and 3. For T > Tg, the data for relaxation time are reasonably well described by the Arrhenius form, eq 11, at least for states 2 and 3, where a straight line can be drawn for ln τ(T), while for temperatures below Tg, we find no such simple dependence. For state 1, a straight line is drawn to show that the same parameters that are found for states 2 and 3 can be also adopted here; one can see, however, that the data found for state 1 have a significant degree of uncertainty and can be treated only qualitatively, if the Arrhenius form is enforced.

Figure 4.

Calculated temperature dependence of the relaxation time for three states of reduction. Open and closed circles are data obtained above and below the glass transition temperature, respectively. Lines are least-squares fits to points above Tg to give the activation energies and prefactors shown in Table 3.

In Table 3, possible ranges of activation energies and frequency prefactors are listed for all three states. The uncertainty of the results naturally stems from that of experimental data on the ET kinetics, from the difficulty of assigning unambiguously all parameters of the model, and from an obvious simplification that we introduced assuming that the relaxation dynamics can be described in terms of a single relaxation time in the Arrhenius form of eq 11. Despite a significant scatter, from Table 3 and Figure 4, one can see that we can talk about typical characteristics of the relaxation dynamics (above Tg) of the protein within the adopted Arrhenius model.

TABLE 3.

Activation Energies and Prefactors Obtained from Fittings in Figure 4

| state | Ea, eV | , s−1 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (−0.05) ÷ (+0.12) | 105 ÷ 108 |

| 2 | 0.10 ÷ 0.20 | 109 ÷ 1011 |

| 2aa | 0.42 ÷ 0.54 | 1015 ÷ 1017 |

| 3 | 0.08 ÷ 0.11 | 106 ÷ 107 |

For all three states, Table 3 shows that the activation energy for structural relaxation in the reaction centers from Rps. sulfoviridis is in the range (0.1 ± 0.1) eV, while the best estimate for frequency prefactor, common for all three states, is approximately 108 s−1. Earlier, we found that for the reaction centers from a closely related bacteria Rps. viridis, for state 2, the activation energy is significantly higher, and the corresponding frequency pre-factor is higher as well, while the relaxation time is in the same range of 0.1–1.0 µs. These data are also shown in Table 3 for comparison. Possible reasons for such a discrepancy will be discussed in the next section.

5. Discussion

The main effort of this work was to extract information about the structural relaxation dynamics of the protein from the kinetics of ET reactions; the main results are presented in Table 3 and Figure 4. The relaxation parameter τ(T), for temperatures above Tg, was assumed to have the Arrhenius form, eq 11, and for all three redox states of the protein that were examined in the experiment, we were able to determine the range of possible values for the activation energy Ea and the corresponding frequency prefactor. From the scatter of the obtained data seen in Table 3 and Figure 4, one can conclude that even above the glass transition temperature, the Arrhenius form (i.e., the process with a single activation energy) is only a rough approximation for relaxation dynamics of the protein; in particular, the problem is obvious for state 1, while for states 2 and 3 the Arrhenius form holds relatively well. We take it as an indication that in fact the relaxation process in microsecond time domain is more complicated than the one with single relaxation time and single activation energy, and likely involves a mixture of different timescales as was found experimentally13 for relaxation of a RC protein in picosecond time domain.

The relaxation parameters of the protein medium should not strongly depend on the redox state of the protein; therefore, if the Arrhenius form holds, we expect that the activation energy and the frequency pre-factor should be similar for all three states. This can be considered as an additional independent test of the Arrhenius assumption. As seen from Table 3, although there is an overlap of possible ranges for activation energy and frequency pre-factor, the variation of possible values is significant. This indicates again that the Arrhenius form is likely only a rough approximation of the actual relaxation dynamics of the protein.

With qualification stated above, we can assign a characteristic value of the activation energy common for all three redox states as 0.1 eV, while for the frequency prefactor, one can take 108 s−1. These characteristic values can be used for a qualitative discussion of the underlying protein dynamics.

A similar analysis was performed earlier on the reaction center from Rps. viridis.1 The data obtained now for two bacteria allow one to speculate about the possible nature of the protein relaxation dynamics involved in regulation of electron transfer in these systems. We believe one of the main contributors to such dynamics is the process of breaking and making hydrogen bonds of internal water molecules in the protein and the protein structure itself.

In Rps. viridis, in state 2 (hemes H1 and H2 are reduced),the activation energy was found be around 0.5 eV (48 kJ/mol).This activation energy is high compared with the strength of typical H bonds in proteins, 8–29 kJ/mol.42 Thus, the process of structural relaxation in this case should involve either breaking unusually strong H bonds or other kinds of barriers. In contrast, in Rps. sulfoviridis, the activation energies are much lower, less than 10 kJ/mol. This can be interpreted as due to breaking only weak H bonds, for example, of internal water molecules. A large number of such water molecules is seen in the crystal structure of the protein from Rps. viridis;43–47 see Figure 1a (Brookhaven Protein Databank, 1PRC).

The exact reason for the difference in relaxation parameters between Rps. viridis and Rps. sulfoviridis is difficult to pinpoint without an additional study. It could be, for example, that a different amount of internal water molecules were present in the RC samples from Rps. viridis and Rps. sulfoviridis. Figure 1b shows some water molecules detected in the crystal structure of Rps. virdis between heme c-559 and the special pair. These water molecules are likely to be involved in electron tunneling and in activation process of the ET reaction. In particular, interesting is one molecule, HOH38 (W1). This internal water molecule is completely embedded in subunit C, which is a globular protein docked to the top of the reaction center. Moreover, it is located in an enclosed compartment made by several residues, thus not being exposed to the external solvent. Based on the angle (90°) and distances between the corresponding atoms (~ 3 Å), it is reasonable to suggest that this water molecule can form a total of four hydrogen bonds (two as protons donor and additional two as protons acceptor): one is to the Nδ1 atom of His248C (axially ligated to iron of heme c-559), the other is to the backbone oxygen of the carbonyl group of Phe253C, and two more are to the backbone nitrogen and carbonyl oxygen of Asn249C and Thr252C, respectively. Additionally, carbonyl oxygens of Asn249C and Lys259C may also contribute to somewhat weaker electrostatic interactions with HOH38 molecule. This means that the degrees of freedom of this particular water molecule are severely restraint by its environment. All other water molecules shown in Figure 1b and several others (not shown) belong to the interface between subunit C (containing the tetraheme cytochrome) and subunits M and L of the reaction center.

Thus, the water molecule HOH38 near c-559 in Rps. viridis can be strongly H bonded to nearby residues, thereby creating a high barrier for reorientation of its dipole moment caused by electron transfer from c-559 to P+. It is likely that this particular molecule significantly contributes to the activation process in Rps. viridis. If this particular single molecule is absent in Rps. sulfoviridis, the electron-transfer dynamics will be significantly altered. The presence or absence of specific molecules at standard conditions can depend on small structural differences between the two proteins. Our results indicate a pronounced difference in relaxation dynamics between Rps. viridis and Rps. sulfoviridis; we therefore suspect that this one important internal water HOH38 may be absent in the structure of Rps. sulfoviridis. Since other HOH molecules near c-559 are not expected to form any strong H bonds, they are able to rotate more freely so that their dipoles reorient in barrierless fashion, which could explain nearby barrierless, temperature-independent dipole reorientation revealed in our analysis of the Rps. sulfoviridis kinetic data. Needless to say that such a hypothesis should be examined in further computational studies.

The behavior of the relaxation parameters for Rps. sulfoviridis is in the range of what is expected from the Transition State Theory treatment of an activation process, namely, a reasonable activation energy 0.1 eV and a frequency prefactor 108 s−1, which is below kT/2πℏ ≃ 1013s−1 at room temperature. On the other hand, for Rps. viridis, the frequency prefactor was found to be unusually high (1016 s−1), which is a strong indication that relaxation dynamics is inhomogeneous and cannot be described within a simple TST picture. This could be due to a closeness of the system to the glass transition, for example, which in turn can depend on the hydration level of Rps. viridis compared with Rps. sulfoviridis. As we indicated above, the actual relaxation process is likely more complicated than that described by our model with a single relaxation time τ in both Rps. viridis and Rps. sulfoviridis.

As we mentioned, the reorientation of polar groups of the protein structure and dipole moments of internal water molecules are likely the main contributors to structural relaxation that we observe here. Indeed such processes can involve a wide range of various strong and weak H bonds in the protein, contributing to inhomogeneity of the relaxation dynamics. Also, individual internal water molecules that are not H bonded to any residues in the protein can freely rotate and therefore can contribute to relaxation dynamics of the protein even at very low temperatures. Such water molecules, for example, could explain the observed relaxation dynamics at low temperatures in our experiments. The direct experimental evidence for the role of individual freely rotating water molecules in electron transfer in RC proteins was recently presented in the literature. Using the methods of femtochemistry, Shuvalov with co-workers48 have discovered a water molecule between P and BA cofactors in pheophytin-modified reaction centers from Rb. sphaeroides R-26 that was freely rotating at 90 K at a frequency of 32 cm−1 close to the H2O rotation frequency in the gas phase.

Black circles in Figure 4 stand for the relaxation times calculated from the ET kinetic curves below Tg. It is seen that they first approximately follow the trend at high temperature above Tg but then tend to saturate at lower temperatures. Thus, the relaxation dynamics continues well below the glass transition temperature Tg. Here, however, the deviation from the Arrhenius form is obvious.

At low-temperatures, which were examined in the experiments, the applicability of our classical diffusion-reaction equation to the description of the relaxation process may be questioned and an extension of the theory that includes the quantum effect in diffusion may be required. Such theory should be based on a quantum equation that will describe the random walk among the discrete quantum levels of our harmonic oscillator representing the conformational coordinate, X. Also, a fully quantum expression for electron-transfer rate from a given level will be necessary for a correct description of the electron-transfer process under nonequilibrium conditions. Both these factors introduce new parameters and make the theory more complicated if not intractable. On the other hand, the accuracy of the experiment at low temperatures is insufficient to justify the above refinements of the theory. For instance, the kinetics are poorly reproduced between successive flashes, which indicates that a fraction of the reaction centers do not return to the initial state.

In state 2, where two high-potential hemes are reduced prior to the initial laser flash that prepares P+ state, electron transfer from c-556 to c-559 could contribute to the observed re-reduction kinetics of P+, which was not considered in this paper. It was shown experimentally5,49 that there is no direct transfer from c-556 to P+ and that oxidation of c-556 is ten times slower than that of c-559. The slow rate of this reaction was also confirmed by measurements of the P+ re-reduction kinetics.50 Therefore, the electron transfer from c-556 to c-559 merely reduces heme c-559 after the reaction under study, that is, the electron transfer from c-559 to P+, is completed.

In state 3, where three highest-potential hemes are reduced prior to the initial flash, the conclusion of ref 5 was that the electron transfer from c-552 to c-559 is very fast as compared with the electron transfer from c-559 to P+, so that any transient oxidation of c-559 due to the latter reaction could not be detected. The direct transfer from c-552 to P+ is ruled out by a too large donor–acceptor separation. Then, the observed kinetics of the P+ re-reduction is fully due to the reaction under study. However, during this reaction heme c-559 remains reduced whereas heme c-552 is oxidized, which should affect the observed kinetics of the P+ re-reduction. The pair c-552 and c-559 can be considered as a united donor center with the parameters different from those for the c-559 center alone. Taking account of these details would be beyond the accuracy of the present model. Therefore, we applied our approach to the data for state 3 in the same manner as for states 1 and 2. More detailed consideration is required, however, to accurately address the question of the effect of the fast exchange between c-552 and c-559 on the kinetics of the observed reduction of P+.

6. Conclusion

In summary, this and the previous studies1 have demonstrated how the information about the structural protein dynamics occurring on the microsecond time-scale can be extracted from the kinetics of electron-transfer reactions in a protein using our theoretical method of the diffusion-reaction equation and a Sumi–Marcus-type model. These studies suggest a new approach to probe the dynamics of proteins, which can be complementary to other existing techniques in this area such as one reported recently by Wang et al.13

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grants from the Civil Research and Development Foundation (RUC2-2658-MO-05) and the Russian Foundation for Fundamental Research (05-03-32104, 05-03-33127). Partial support (to AAS and DMP) is due to NSF and NIH (GM54052) and (to J.M.O.) to the Ministry of Education and Culture of Spain (BFU2004-04914-C02-01/BMC) and Andalusia Government (PAI CVI-261).

References and Notes

- 1.Medvedev ES, Kotelnikov AI, Goryachev NS, Psikha BL, Ortega JM, Stuchebrukhov AA. Mol. Simul. 2006;32:735. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman BM, Ratner MA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:6237. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cartling B. J. Chem. Phys. 1991;95:317. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ortega JM, Mathis P. FEBS Lett. 1992;301:45. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80207-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ortega JM, Mathis P. Biochemistry. 1993;32:1141. doi: 10.1021/bi00055a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dohse B, Mathis P, Wachtweitl J, Laussermair E, Iwata S, Michel H, Oesterhelt D. Biochemistry. 1995;34:11335. doi: 10.1021/bi00036a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortega JM, Dohse B, Oesterhelt D, Mathis P. FEBS Lett. 1997;401:153. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortega JM, Dohse B, Oesterhelt D, Mathis P. Biophys. J. 1998;74:1135. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77831-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okamura MY, Paddock ML, Graige MS, Feher G. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1458:148. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMahon BH, Müller JD, Wraight CA, Nienhaus GU. Biophys. J. 1998;74:2567. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77964-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kriegl JM, Forster FK, Nienhaus GU. Biophys. J. 2003;85:1851. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74613-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kriegl JM, Nienhaus GU. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434740100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, Lin S, Allen JP, Williams JC, Blankert S, Laser C, Woodbury NW. Science. 2007;316:747. doi: 10.1126/science.1140030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skourtis SS, Beratan DN. Science. 2007;316:703. doi: 10.1126/science.1142330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherepanov DA, Krishtalik LI, Mulkidjanian AY. Biophys. J. 2001;80:1033. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinbach PJ, Chu K, Frauenfelder H, Johnson JB, Lamb DC, Nienhaus GU, Sauke TB, Young RD. Biophys. J. 1992;61:235. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81830-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zusman LD. Chem. Phys. 1980;49:295. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexandrov IV. Chem. Phys. 1980;51:449. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ovchinnikova MY. Teor. Eksp. Khim. (Russian) 1981;17:651. [Google Scholar]; Theor. Exper. Chem.(Engl. Transl.) 1982;17:507. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helman AB. Chem. Phys. 1982;65:271. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaitan KV, Rubin AB. Biofizika (Russian) 1982;27:386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Biophysics (USSR) (Engl. Transl.) 1982;27:393. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agmon N, Hopfield JJ. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;78:6947. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agmon N, Hopfield JJ. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:2042. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cartling B. J. Chem. Phys. 1985;83:5231. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sumi H, Marcus RA. J. Chem. Phys. 1986;84:4894. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nadler W, Marcus RA. J. Chem. Phys. 1987;86:3906. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nadler W, Marcus RA. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1988;144:24. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verméglio A, Garcia D, Breton J. Cytochrome arrangements in reaction centers of different species of photosynthetic bacteria. In: Michel-Beyerle ME, editor. Reaction Centers of Photosyntetic Bacteria. Vol. 6. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1989. p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clayton RK, Clayton B. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1978;501:478. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(78)90115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee E, Medvedev ES, Stuchebrukhov AA. J. Chem. Phys. 2000;112:9015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jortner J. J. Chem. Phys. 1976;64:4860. [Google Scholar]

- 32.ωcl does not enter the rate assuming ℏωcl ≪ 2kBT.

- 33.The initial population after the laser flash corresponds to the neutral P in the ground electronic state and may differ from the Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the oxidized P+ state, which would result in an initial lag of the decay kinetics (see ref 24) due to fast equilibration in the initial (charge-separated) state before the reaction starts. Here, we assume that this lag is not observable on the experimental microsecond time scale.

- 34.Kuharski RA, Bader JS, Chandler D, Sprik M, Klein ML, Impey RW. J. Chem. Phys. 1988;89:3248. [Google Scholar]

- 35.One more component, the slow (ref 5) or intermediate (ref 6) phase of the kinetics observed in state 3 is ascribed to the triplet state, 3P, which has strong absorption at 1300 nm (ref 5).

- 36.Shopes RJ, Levine LMA, Holten D, Wraight CA. Photosynth. Res. 1987;12:165. doi: 10.1007/BF00047946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shopes RJ, Wraight CA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1987;893:409. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(87)90093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sebban P, Wraight CA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1989;974:54. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(89)80171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao JL, Shopes RJ, Wraight CA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1990;1015:96. [Google Scholar]

- 40.In state 1, three sets of successive measurements showed successively increasing amplitudes of the VS component, which was presumably due to the appearance of damaged centers in which c-559 was irreversibly oxidized before the flash. Therefore, only the first set of data is shown in Figure 1 for state 1.

- 41.Frolov EN, Goldanskii VI, Birk A, Parak F. Eur. Biophys. J. 1996;24:433. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jeffrey GA. An introduction to hydrogen bonding (Topics in physical chemistry) New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deisenhofer J, Epp O, Miki K, Huber R, Michel H. J. Mol. Biol. 1984;180:385. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(84)80011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deisenhofer J, Epp O, Miki K, Huber R, Michel H. Nature. 1985;318:618. doi: 10.1038/318618a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deisenhofer J, Michel H. EMBO J. 1989;8:2149. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deisenhofer J, Michel H. Science. 1989;245:1463. doi: 10.1126/science.245.4925.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deisenhofer J, Epp O, Sinning I, Michel H. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;246:429. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shuvalov VA, Yakovlev AG. FEBS Lett. 2003;540:26. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00237-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dracheva SM, Drachev LA, Konstantinov AA, Semenov AY, Skulachev VP, Arutyunyan AM, Shuvalov VA, Zaberezhnaya SM. Eur. J. Biochem. 1988;171:253. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen I-P, Mathis P, Koepke J, Michel H. Biochemistry. 2000;39:3592. doi: 10.1021/bi992443p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]