Abstract

AIM(S)

To examine Primary Care Trust (PCT) demographics influencing general practitioner (GP) involvement in pharmacovigilance.

METHODS

PCT adverse drug reaction (ADR) reports to the Yellow Card scheme between April 2004 and March 2006 were obtained for the UK West Midlands region. Reports were analysed by all drugs, and most commonly reported drugs (‘top drugs’). PCT data, adjusted for population size, were aggregated. Prescribing statistics and other characteristics were obtained for each PCT, and associations between these characteristics and ADR reporting rates were examined.

RESULTS

During 2004–06, 1175 reports were received from PCTs. Two hundred and eighty (24%) of these reports were for 14 ‘top drugs’. The mean rate of reporting for PCTs was 213 reports per million population. A total of 153 million items were prescribed during 2004–06, of which 33% were ‘top drugs’. Reports for all drugs and ‘top drugs’ were inversely correlated with the number of prescriptions issued per thousand population (rs=−0.413, 95% CI −0.673, −0.062, P < 0.05, and r=−0.420, 95% CI −0.678, −0.071, P < 0.05, respectively). Reporting was significantly negatively correlated with the percentages of male GPs within a PCT, GPs over 55 years of age, single-handed GPs within a PCT, the average list size of a GP within a PCT, the overall deprivation scores and average QOF total points. ADR reports did not correlate significantly with the proportion of the population over 65 years old.

CONCLUSIONS

Some PCT characteristics appear to be associated with low levels of ADR reporting. The association of low prescribing areas with high ADR reporting rates replicates previous findings.

Keywords: adverse drug reactions, pharmacovigilance, prescribing, spontaneous reporting

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions to regulatory authorities is common, and there is concern about falling numbers of general practitioner reports.

Although previous work has suggested high prescribers are less interested in pharmacovigilance, a recent examination of reporting to the Yellow Card scheme has suggested ADR reporting is correlated with high prescribing rates.

This study aimed to examine influences on the reporting of ADRs to the Yellow Card scheme in primary care.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

High prescribing rates within primary care are correlated with low ADR reporting rates.

Several Primary Care Trust characteristics related to general practitioners, such as increased proportions of single-handed general practitioners and larger list sizes, are associated with low ADR reporting rates.

Introduction

Spontaneous reports of suspected adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are an important source of pharmacovigilance data [1, 2]. However, there is widespread under-reporting of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) [3]. In the UK, the House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts [4], a National Audit Office report [5], an independent review of the Yellow Card scheme [6], a House of Commons Health Committee [7] and the British Medical Association [8] have all noted concerns about falling numbers of ADRs reported to the Yellow Card scheme.

The Yellow Card scheme solicits reports of novel, serious, or medically significant ADRs to established medicines, and reports of all reactions to medicines under intensive surveillance (indicated with a black triangle [▾]). These are most commonly newly marketed products. Historically, general practitioners (GPs) have submitted more reports than any other reporter group, but there has been a marked decline in the number of GP reports: in the West Midlands region of the United Kingdom the number of reports from GPs fell by 58% between 1994 and 2005.

The West Midlands Centre for Adverse Drug Reactions, in its role as Yellow Card Centre West Midlands (YCCWM), acts as a regional outreach centre of the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), which administers the Yellow Card scheme jointly with the Commission on Human Medicines. Until April 2006, this centre also processed Yellow Cards reports from within the West Midlands region.

We wished to examine the association of various Primary Care Trust (PCT) characteristics on reporting rates to the Yellow Card Scheme within the West Midlands Strategic Health Authority (SHA).

Methods

Study population and data sources

The West Midlands Region of the United Kingdom is covered by the West Midlands SHA. During the period 2004–06, the SHA included 30 PCTs responsible for general practitioner services. The estimated 2004 population of the West Midlands region was 5 268 319, similar to that of Scotland (2001 Census, population size 5 064 200), with an average PCT population of 177 860 (range 87 900–366 800; median 164 950).

Data on PCT ADR reporting rates and reported drugs were obtained from the YCCWM database. All reports for the period from 1 April 2004–31 March 2006 were extracted to produce aggregated data for each PCT.

Estimated PCT population data for 2004, based on projections from the 2001 census data, were obtained from the West Midlands Public Health Observatory (http://www.wmpho.org.uk), and the proportion of the population over the age of 65 years of age was calculated for each PCT. Index of deprivation scores for PCT areas in 2004 were obtained from the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister.

Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) performance information for PCTs was obtained from the NHS Information Service website (http://www.ic.nhs.uk). QOF is a contractual arrangement used by the NHS to performance-manage GPs. It measures a number of practice and organizational indicators and each practice can accumulate up to 1050 ‘QOF points’. QOF data for 2005–06 were used for analysis.

Statistics on the GP workforce within the West Midlands region were obtained from the NHS Information Centre in Leeds. Data for each PCT included: the proportion of GPs over 55 years of age, the proportion of female GPs, the average list size, and the proportion of GPs in single-handed practice.

Data analysis

We listed the 10 drugs for which most reports were received by the YCCWM during 2004–05 and separately for 2005–06. The two lists were then combined to create a set of ‘top drugs’ (n= 14) for the 2004–06 period. Vaccines were excluded from these tables because they are supplied centrally, and etanercept was excluded because it requires specialist administration in hospital and was not likely to have been prescribed in primary care. Data on prescribing for these drugs within West Midlands PCTs were obtained from the NHS Information Centre in Leeds for the period from 1 April 2004–31 March 2006. The total number of prescribed items was also obtained for each PCT for each year.

Data were imported into STATA (STATA 10.0, College Station, Texas: Statacorp) for statistical analysis.

Variables were examined to ensure that they followed a normal distribution using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and z-scores were calculated to test for skewness and kurtosis. If indicated, and when possible, skewed data were transformed.

Correlations were performed to examine associations between PCT characteristics and Yellow Card reporting rates. Where parametric data were available, the Pearson correlation coefficient, r, was used. To explore correlations with non-parametric data, Spearman's correlation coefficient, rs, was used. Two-tailed tests were used, and P < 0.05 was taken to be statistically significant. Fisher's transformation was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals for correlations.

Results

During the period 2004–06, 1175 Yellow Card reports were submitted within the West Midlands region from PCTs. The mean rate of reporting was 213 reports per million population (SD 101.28, median 208, range 58–553). There were 14 reports of death associated with ADRs. The top drugs list (consisting of 14 drugs) for 2004–06 is presented in Table 1. These drugs accounted for 24% of the total number of reports received. Thirteen of the 14 ‘top drugs’ were black triangle [▾] drugs. Therefore, the reporting rate for ‘top drugs’ can be considered a marker for the reporting of reactions to black triangle drugs.

Table 1.

Combined ADR reports for ‘top drugs’ for 2004–06

| Drug name | Number of reports |

|---|---|

| Pregabalin▾ | 32 |

| Simvastatin | 29 |

| Ezetimibe▾ | 28 |

| Bupropion▾ | 24 |

| Escitalopram▾ | 24 |

| Duloxetine▾ | 19 |

| Etoricoxib▾ | 19 |

| Rosuvastatin▾ | 18 |

| Rofecoxib▾ | 17 |

| Sibutramine▾ | 16 |

| Rosiglitazone▾ | 15 |

| Strontium ranelate▾ | 15 |

| Tiotropium▾ | 15 |

| Solifenacin▾ | 9 |

Altogether 153 050 187 prescriptions were issued in the West Midlands during 2004–06; the list of top drugs accounted for 5 007 259 prescriptions (3.3%).

The PCT population measured in 2004 was significantly correlated with the number of reports for all drugs (square root transformation, r= 0.815, 95% CI 0.644, 0.908, P < 0.001) and ‘top drugs’ (square root transformation r= 0.644, 95% CI 0.369, 0.185, P < 0.001). We therefore used an ADR reporting rate normalized per million population. PCT characteristics are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

West Midlands Primary Care Trust characteristics related to general practice

| PCT characteristic | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage of male GPs | 65.7% (5.9%) | 54.2–75.4% |

| Percentage of single-handed practices | 26.0% (17.2%) | 0–58.8% |

| Percentage of GPs over 55 years of age* | 22.8% (median 22.2%) | 8–50% |

| Average list size | 1699 (177) | 1349–2035 |

| Total QOF points | 1013 (22) | 972–1044 |

| Proportion of population over 65 years of age* | 16.3% (median 16.8%) | 9.8–19.9% |

| Index of multiple deprivation score* | 24 (median 19.7) | 10.8–52.2 |

Non-parametric data (median reported instead of SD).

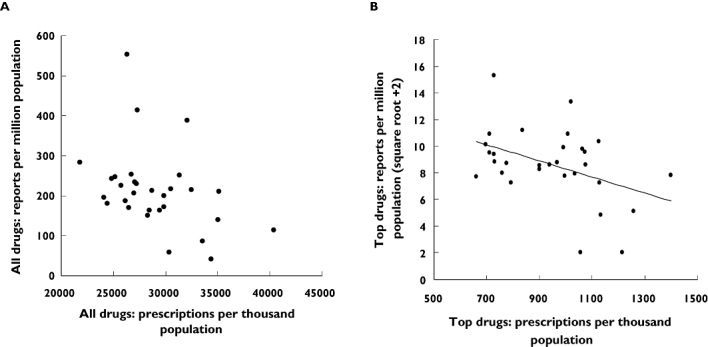

Reports for all drugs (Figure 1A) and ‘top drugs’ per million population (Figure 1B) correlated negatively with the number of prescriptions issued for all drugs per thousand population (Table 3). The square of the correlation coefficient (r2) was 0.18 for ‘top drugs’ per million population, suggesting that the prescribing rate was responsible for 18% of the variability in the ADR reporting rate.

Figure 1.

ADR reports per million population vs. number of prescriptions per thousand population in the West Midlands during the financial years 2004–05 and 2005–06. A) ADR reports per million population for all drugs and prescriptions per thousand population for all drugs (rs=−0.413, P < 0.05). B) ADR reports per million population (square root + 2 transform) for ‘top drugs’ and prescription per thousand population for ‘top drugs’ with fitted line (r= -0.420, P (two-tailed) < 0.05, r2= 0.18)

Table 3.

Correlates between ADR reporting rates and PCT variables

| PCT variable | ADR reports per million population* | ADR reports per million population (square root +2 transform) for ‘top drugs’ |

|---|---|---|

| Prescriptions per thousand population | rs=−0.413, P < 0.05 95% CI −0.673, −0.062 | r=−0.420, P < 0.05 95% CI −0.678, −0.071 |

| Percentage of male GPs within PCT | rs=−0.482, P < 0.01 95% CI −0.717, −0.147 | r=−0.50, P < 0.01 95% CI −0.729, −0.171 |

| Percentage of single handed practitioners | rs=−0.734, P < 0.001 95% CI −0.865, −0.508 | r=−0.663, P < 0.001 95% CI −0.826, −0.398 |

| Average list size | rs=−0.519, P= 0.003 95% CI −0.741, −0.196 | r=−0.434, P < 0.05 95% CI −0.687, −0.088 |

| Proportion of GPs over 55 years of age (square root transform) | rs=−0.566, P < 0.01 95% CI −0.769, −0.258 | r=−0.485, P < 0.01 95% CI −0.720, −0.151 |

| Average total QOF points | rs= 0.484, P < 0.01 95% CI 0.150, 0.719 | r= 0.491, P < 0.01 95% CI 0.158, 0.723 |

| Overall deprivation score* | rs=−0.550, P < 0.01 95% CI −0.760, −0.236 | rs=−0.570, P < 0.01 95% CI −0.769, −0.258 |

| Proportion of population over 65 years of age* | rs= 0.147, P= 0.438 95% CI −0.225, 0.482 | rs= 0.128, P= 0.502 95% CI −0.244, 0.466 |

Non-parametric rs= Spearman's ranking correlation (rs), two tailed. r= Pearson's correlation (r), two tailed.

Reporting of ADRs to all drugs and ‘top drugs’ per million population correlated negatively with the percentage of male GPs within a PCT, the percentage of GPs over 55 years of age, the percentage of single-handed GPs within a PCT and the average list size of a GP within a PCT (Table 3). The proportion of single-handed GPs was significantly associated with list size (r= 0.726, 95% CI 0.495, 0.861, P < 0.001).

Reporting of ADRs to all drugs and ‘top drugs’ per million population was correlated with average QOF total points. PCTs with a higher proportion of single-handed GPs had a significantly lower average QOF performance (r=−0.758, 95% CI −0.879, −0.548, P < 0.001).

No statistically significant correlation was found between the proportion of the PCT population over 65 years of age and the number of reports per million population for all drugs (rs= 0.147, 95% CI −0.225, 0.482, P= 0.438) or ‘top drugs’ (rs= 0.128, 95% CI −0.244, 0.466, P= 0.502).

Overall deprivation scores correlated negatively with reporting rate per million population for all drugs (rs=−0.550, 95% CI −0.760, −0.236, P < 0.01) and ‘top drugs’ (rs=−0.570, 95% CI −0.769, −0.258, P < 0.01). This relationship held when the health component of the deprivation index was analysed independently for all drugs (rs=−0.542, 95% CI −0.755, −0.226, P < 0.01) and ‘top drugs’ (rs=−0.598, 95% CI −0.768, −0.303, P < 0.001). Higher deprivation scores were significantly associated with increased list size (rs= 0.523, 95% CI 0.201, 0.744, P= 0.003); however, they correlated strongly with increases in the proportion of the single-handed GPs (rs= 0.777, 95% CI 0.578, 0.888, P < 0.001).

Discussion

Prescribing rates and ADR reporting

Our results indicate that PCTs with higher prescribing GPs are less likely to report ADRs to ‘top drugs’, 13 out of 14 of which were black triangle drugs. This may indicate that those GPs who are more likely to take up the use of black triangle drugs (‘early adopters’) are least likely to submit Yellow Cards. The corollary is that those who are therapeutically conservative are more likely to use the Yellow Card scheme, but correspondingly less likely to prescribe those drugs whose ADRs are least well defined, and where ADR reports are most helpful in defining drug safety. However, the fact that all prescribing was also negatively correlated with Yellow Card reporting rates, may mean that a propensity to reach for the prescription pad was associated with a reluctance to report adverse drug reactions, perhaps because of a positive view of drug safety, or perhaps because of a disinterest in drug safety issues.

In contrast with our study, Clark and co-workers examined reports to the Scottish Yellow Card centre, and found higher rates of prescribing were associated with higher numbers of ADR reports [9]. They found a significant positive correlation (r= 0.66, P= 0.04) between reports per million of the population and prescriptions per 1000 population, suggesting that 44% of the observed variation in reporting rates was attributed to variations in prescribing rates. There were some important differences between their study and ours. They examined all Yellow Card reports, including those from acute NHS trusts, while their prescribing data were from primary care alone. Although the populations of Scotland and the West Midlands are of similar size, the number of Scottish health boards is fewer than the number of PCTs in the West Midlands region, and they differ more widely in population size (range 26 450–2 210 390) than West Midlands PCTs (87 900–366 800). Yellow Card reporting from hospitals sited within the Scottish health boards may also have skewed the reporting rates of health boards.

Other evidence supports our study's finding that higher prescribers are less likely to report ADRs. Inman & Pearce examined 28 402 general practitioners in the UK identified through (prescription event monitoring) studies, calculating their return rates for post-marketing drug safety information requests from the Drug Safety Research Unit's green card [10].Their major finding was that the 10% of doctors with the highest rates of prescribing were responsible for 44% of total prescribing of new drugs after the first 6 months of their introduction, with a consistent inverse relationship between the number of prescriptions and the response rate to PEM studies. High prescribers were less likely to engage with pharmacovigilance.

The finding from our study of a negative correlation between the number of reports per million population and the number of prescriptions per thousand population for both the ‘top drugs’ and ‘all drugs’ would appear to provide a similar message. Higher prescribers are less likely to report the adverse effects of the drugs they prescribed. Whether this is because of a lack of awareness of the harm caused by prescribed medicines or a general positive view of the pharmaceutical industry is not known.

A study by Florentinus and co-workers [11] examined the dispensing data of 103 Dutch GPs, selecting five new drugs that had achieved rapid market penetration as study cases: salmeterol/fluticasone, rofecoxib, esomeprazole, tiotropium and rosuvastatin. A minority of GPs was responsible for 50% of prescribing of each drug, for example 10.9% of GPs were responsible for prescribing 50% of rofecoxib prescriptions. A positive attitude towards new drugs was positively associated with the prescribing of new drugs (OR = 1.65; 95% CI 1.26, 2.15). GPs who were more industry orientated were also more likely to prescribe new drugs (OR = 1.37; 95% CI 1.17, 1.61) compared with those less interested in pharmaceutical industry relationships. More recently, an examination of the early adoption of newly approved selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors by Danish GPs found a small subset of high-volume prescribers was responsible for the majority of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug initiations [12].

General practice characteristics

Our study also found that the reporting rate per million population for all drugs and ‘top drugs’ correlated negatively with the proportion of male GPs, the proportion of single-handed GPs, the average list size and the percentage of GPs over 55 years old. The finding that an increasing proportion of female GPs was associated with higher levels of reporting may arise from gender differences in the introduction of new therapies and differing views on risk management of medication [11]. It is not clear why PCTs with higher proportions of older GPs were poorer reporting areas, although younger GPs may have received more education about pharmacovigilance during their undergraduate and postgraduate training. The proportion of female GPs will also be higher in the younger age group than the over 55 year olds.

The proportion of single-handed GPs was a particularly strong correlate with a low ADR reporting rate. Examination of single-handed GPs' prescribing rates gives inconsistent results [13, 14], with arguments that group practices can be high prescribers. Florentinus et al. found single-handed GPs were higher prescribers (OR = 2.55; 95% CI 1.70, 3.83) [11]. Our findings support this. However, PCTs containing higher proportions of single-handed GPs were also more likely to have bigger list sizes, be based in more deprived areas and have lower QOF scores. This perhaps reflects pressures on single-handed GPs, which may inhibit ADR reporting.

Our study did not examine individual GP ADR performance, but the association of higher prescribing leading to lower reporting rates within PCTs is interesting in the context of the Florentinus' group results [11]. We suspect high prescribing GPs may be more easily influenced by the pharmaceutical industry, and correspondingly less interested in pharmacovigilance.

There was no correlation between the proportions of the population of a PCT over 65 years of age, and the ADR reporting rate for ‘all drugs’ and ‘top drugs’. This could be considered surprising given that older patients are the largest consumers of prescribed medicines. However, this was a crude ‘geographic’ characteristic based on the population data, rather than the characteristics of the individuals' prescribed medicines. Deprivation scores were negatively correlated with ADR reporting rates for ‘all drugs’ and ‘top drugs’. As noted already, deprived areas were also strongly correlated with increases in the proportion of single-handed GPs. Struggling inner city health services, with a diverse population, may find ADR reporting a challenge. Alternatively, general practitioners based in more affluent areas may be influenced by a more demanding and well-informed patient population.

Targets for Yellow Card reporting?

Our finding that average QOF performance of PCTs was significantly correlated with increased Yellow Card reporting may have implications for promoting the Yellow Card scheme. It has been suggested that the use of a quality indicator in the GP contract could be used as a ‘carrot’ to increase Yellow Card reporting rates [15]. However, our data suggest that GP practices performing well under QOF are already engaged with the Yellow Card scheme. It is possible that a QOF target for Yellow Card reporting would be viewed by poor performers as punishment by way of loss of earnings. Attributing negative consequences to the Yellow Card scheme could change the perception that GPs have of the Yellow Card scheme, and crowd out the historically altruistic nature of the scheme. Future changes in the GP contract under different governments, or even increased private provision, could see the Yellow Card scheme returning to voluntary non-fee driven reporting with unpredictable consequences, if a new reporting culture based on financially driven targets had been developed. Additionally, informing a contractual department of the NHS of an individual GP's reporting performance statistics might be perceived as breaking the confidential nature of the Yellow Card scheme.

Limitations

There are limitations to our study. Correlations are based on pooled reporting data within an individual PCT. Only limited information was available on PCT characteristics. A future examination of more detailed individual GP characteristics and Yellow Card reporting would provide a more comprehensive picture. Pooled PCT reporting data do include reports from other healthcare professionals. However, the majority of reports from these PCTs during the study period (69%) were submitted by general practitioners.

It could be argued that the correlations between prescribing rates and reporting rates are closer to zero than they are to one. However, the correlations are statistically significant, and r2 values suggest that they explain an important proportion of the variance of ADR reporting rates, although probably not the major part.

Another limitation is that a number of Yellow Cards may have been submitted directly to the MHRA, bypassing the West Midlands unit. During 1997–2005 an average of 19% of reports per year (range 13.2–26%) bypassed the YCCWM. Although the addition of bypass data did not change underlying trends in reporting in the region, we cannot discount the chance that our results would have been altered by including bypass reports. However, we feel it is unlikely that the reporting rate for a particular PCT has been skewed.

In conclusion, characteristics of PCTs, such as the proportion of single-handed GPs, the proportion of male GPs, and the proportion of GPs over 55 years old and deprivation were negatively correlated with ADR reporting. The finding that areas associated with lower prescribing rates were associated with high ADR reporting rates in PCTs, suggests that high reporters to the Yellow Card scheme are therapeutically cautious individuals. This study also supports previous work showing that high prescribers are less engaged in pharmacovigilance.

Competing interests

None declared.

The authors would like to thank Roger Holder, Head of the Statistics, Primary Care Clinical Sciences, Birmingham University, for his statistical advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Olivier P, Montastruc JL. The nature of the scientific evidence leading to drug withdrawals for pharmacovigilance reasons in France. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:808–12. doi: 10.1002/pds.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke A, Deeks J, Shakir SAW. An assessment of the publically desseminated evdience of safety used in decisions to withdraw medicinal products from the UK and US markets. Drug Saf. 2006;29:175–81. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200629020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hazell L, Shakir SAW. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2006;29:385–96. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200629050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts. London: The Stationery Office; 2003. Safety, Quality, Efficacy: Regulating Medicines in the UK. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safety, Quality, Efficacy: Regulating Medicines in the UK. London: National Audit Office; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metters J. Report of an Independent Review of Access to the Yellow Card Scheme. London: The Stationery Office; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.House of Commons Health Committee. The Influence of the Pharmaceutical Industry. London: The Stationery Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.BMA Board of Science. Reporting adverse drug reactions: a guide for healthcare professionals. London: BMA; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark RC, Maxwell SR, Kerr S, Cuthbert M, Buchanan D, Steinke D, Webb DJ, Bateman ND. The influence of primary care prescribing rates for new drugs on spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions. Drug Saf. 2007;30:357–66. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200730040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inman W, Pearce GL. Prescriber profile and post-marketing surveillance. Lancet. 1993;342:658–61. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91763-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Florentinus SR, Heerdink ER, Groenewegen PP, de Bakker D, van Dijk L, Fabiënne Greins AMG, Leufkins HGM. Who are the early prescribers of new drugs? In: Florentinus SR, editor. New drugs in general practice: prescribing patterns and external influences. Utrecht: Utrecht University; 2006. pp. 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Layton D, Souverein PC, Heerdink ER, Shakir SAW, Egberts AGC. Prescriber adoption of newly approved selective COX-2 inhibitors. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17:1168–74. doi: 10.1002/pds.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williamson PM. The adoption of new drugs by doctors practising in group and solo practice. Soc Sci Med. 1975;9:233–6. doi: 10.1016/0037-7856(75)90027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steffensen FH, Sorenson HT, Oleson F. Diffusion of drugs in Danish general practice. Family Prac. 1999;16:407–13. doi: 10.1093/fampra/16.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dean T. Time for carrots and sticks on ADR reporting? Prescriber. 2006;17:9. [Google Scholar]