Abstract

CCN6 is a secreted cysteine rich matricellular protein (36.9 kDa) that exerts growth inhibitory functions in breast cancer. Reduction or loss of CCN6 protein has been reported in invasive carcinomas of the breast with lymph node metastasis and in inflammatory breast cancer. However, the mechanism by which CCN6 loss promotes breast cancer growth remains to be defined. In the present study we developed lentiviral mediated shRNA CCN6 knockdown (KD) in nontumorigenic mammary epithelial cells MCF10A and HME. We discovered that CCN6 KD protects mammary epithelial cells from apoptosis and activates growth factor-independent survival. In the absence of exogenous growth factors, CCN6 KD was able to promote growth under anchorage independent conditions and triggered resistance to detachment-induced cell death (anoikis). Upon serum starvation, CCN6 KD was sufficient for activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Growth factor-independent cell survival was stunted in CCN6 KD cells when treated with either human recombinant CCN6 protein or the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor LY294002. Targeted inhibition of Akt isoforms revealed that the survival advantage rendered by CCN6 KD requires specific activation of Akt-1. The relevance of our studies to human breast cancer is highlighted by the finding that low CCN6 protein levels are associated with upregulated expression of phospho-Akt-1 (Ser473) expression in 21% of invasive breast carcinomas. These results enable us to pinpoint one mechanism by which CCN6 controls survival of breast cells mediated by the PI3K/Akt-1 pathway.

Keywords: CCN6, WISP3, AKT, growth factor independent, survival, apoptosis, breast cancer, anoikis, apoptosis

INTRODUCTION

CCN6 is a cysteine-rich protein that belongs to the CCN (Cyr61, CTGF, Nov) family of matricellular proteins, with developmental functions (1–3). Recent studies have shown that the CCN protein family members also play important roles in tumorigenesis, including cancer cell proliferation, survival, adhesion, and invasion (4–9). CCN proteins are mostly secreted and extracellular-matrix associated, and have been proposed to connect signaling pathways and facilitate cross-talks between epithelium and stroma (1, 10).

CCN6 is a tumor suppressor gene found to be downregulated in the most aggressive form of locally advanced breast cancer, inflammatory breast cancer, as well as in non-inflammatory breast cancers with lymph node metastasis (5, 11). Immunohistochemical studies of human breast tissue samples have shown that whereas normal epithelium expresses CCN6 protein, CCN6 is reduced or lost in 60% of invasive carcinomas (5, 6). The high frequency of reduction or loss of CCN6 in breast cancer suggests a potential role in initiation and/or progression of human breast cancer.

Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and protein kinase b (Akt) is a frequent alteration in human cancer, including carcinomas of the breast (12–15). Although PI3K/Akt activation is a common pathway for several extracellular growth factors, PI3K/Akt signaling can be activated by growth factor-independent mechanisms. A major function of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is the promotion of cell survival and resistance to apoptosis and anoikis (12–14, 16–19). Anoikis, or detachment-induced apoptosis, is a protective mechanism by which epithelial cells die upon loosing contact with the extracellular matrix. The acquisition of anoikis resistance has been shown to promote breast cancer progression and metastasis by enabling cancer cells to survive in the vascular or lymphatic channels (20, 21).

CCN6 has been proposed to participate in cell survival and it has been studied to modulate insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)-mediated growth and proliferation (6, 22). However, no studies have been carried out to investigate the growth factor- independent functions of CCN6 and the link between CCN6 and survival signaling pathways. In the present study we demonstrate that CCN6 blockade confers a distinct survival advantage to nontumorigenic breast epithelial cells, MCF10A and HME. CCN6 downregulation leads to growth factor-independent survival and proliferation, and is sufficient to trigger anchorage-independent growth of mammary epithelial cells. We show that CCN6 KD protects cells from apoptosis and anoikis. Mechanistically, our data show that growth factor-independent survival and anoikis resistance conferred by CCN6 knockdown require activation of the PI3K/Akt-1 signaling pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

HME cell line was developed and provided by S.P. Ethier (Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, MI); spontaneously immortalized human mammary epithelial cells, MCF10A were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (AATC, Manassas, VA) and maintained as described previously (5). Serum deprivation medium consisted of DMEM/F12 (MCF10A cells) or F-12 (HME cells) supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. This medium was deprived of exogenous factors and serum. Cells were maintained in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2.

Transfections and Transductions

Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequence (5′-CGGCCATTA GATACAACACCTGA ACTCGAGTTCAGGTGTTGTA -3′) targeting human CCN6 (NM_003880) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, Cat No. shDNAC-TRCN0000033361) and shRNA sequence (5′-CCGGGCATCGCT TCTTTGCCGGTATCTCGAGATACCGGCAAA GAAGCGATGCTTTTTG-3′) targeting human Akt-1 (NM_00104031) (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL; Cat. No. RHS3979-9607185) were cloned into pLKO.1-puro vectors. Both shRNA-containing plasmids were packaged into lentiviral particles at the Vector Core (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI). Human Akt-1 siRNA oligonucleotides (sense: 5′-CCAAGCACCGCGUGACCAU-3′; antisense: 5′-AUGGUCACGCGGUGCUUGG-3′), human Akt-2 siRNA oligonucleotides (sense: 5′-CAGAAUGCCAGCUGAUGAA-3′; antisense: 5′-UUCAUCAGCUGGCAUUCUG-3′) and human siRNA negative control oligonucleotides were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

To generate stable MCF10A and HME cell lines with CCN6 or Akt1-knockdown, 1×106 cells per 100mm plate were transduced with the corresponding lentivirus-containing supernatant diluted 1:1 with fresh serum free medium for 48 hours. Stable clones were selected for antibiotic resistance with10μg/ml puromycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 3 weeks. For siRNA oligonucleotide transfections, cells were split into complete medium for 24h before subconfluence. siRNA oligos were transfected into subconfluent cells with Oligofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48h of growth in serum deprivation medium, cells were harvested by trypsinization and utilized for the experiments described below.

Western Blot Analysis

Cell lysates were collected using Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer containing 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Nonidet P-40 and a mixture of protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Samples were boiled in 1×SDS loading buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred onto a nitrocellulose (NC) membrane. For immunoblot analysis, NC membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk and were incubated with corresponding primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Immunoblot signals were visualized by a chemiluminescence system as described by the manufacturer (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ). Blots were re-probed with β-actin to confirm the equal loading of samples.

Primary antibodies including anti-CCN6, anti-Akt-2, and anti-phospho-Akt-2 (Ser474), anti-Cdc25A, anti-Cdc25C (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); anti-Akt, anti-Akt-1, anti-Akt-3, anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473), anti-phospho-Akt-3 (Ser472), anti-GSK-3β, anti-phospho-GSK-3β (Ser9), anti-Cdc2, anti-Cyclin D1 (Cell Signaling, Boston, MA); anti-phospho-Akt-1 (Ser473) (Upstate Biotechnology, Billerica, MA); anti- β-actin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were used at the manufacturers’ recommended dilutions.

Proliferation and Viability Assays

For Trypan blue staining (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA), 2×105 cells were seeded into each well of 6-well plates in complete culture media. For the WST -1 assay (Roche, Indianpolis, IN) 5×103cells were seeded into 96 well microplates in complete culture media. For both assays, the next day, culture media were replaced with serum deprivation medium for 18 h. Subsequently, cells were treated with recombinant CCN6 (200 ng/ml, Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) or with the PI3K/Akt inhibitor LY294002 (20 μM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Each treatment was performed in triplicate. Cell viability was determined by counting cells at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours after treatment. Proliferation using the WST-1 assay was determined at the same time points following the manufacturers’ protocols. Data points represent the mean±SD.

Cell Synchronization and Flow Cytometry

CCN6 KD cells and control cells of HME and MCF10A cell lines were maintained in complete medium serum until they reach 50% confluence. At this time cells were washed, switched to serum deprivation medium and synchronized at the G1/S boundary with double thymidine block. Synchronized cells were released to progress through the cell cycle over the next 12 hours. Cell cycle was analyzed at indicated time points by flow cytometry after staining with propidium iodide (50μg/ml). The percentage of cells in G1, S, or G2 phase is presented as the mean of three independent experiments. Whole cell lysates were collected at the same time points and analyzed by immunoblot to determine CCN6, Cyclin A and Cyclin B1 expression profile through the cell cycle. β-actin served as loading control.

Apoptosis assay

2×106cells or 5×103 cells/well were seeded into each 100mm plate or each well of 96-well microplates in complete culture media respectively. The next day, culture media were switched to serum deprivation media for 18 hours before treatment with recombinant CCN6 (200ng/ml) or LY294002 (20μmol/L) for 24 hours. Caspase activity was quantified using Apo-ONE homogenous Caspase 3/7 assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Annexin V/PI staining (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) of cells in 100mm plates was performed to demonstrate apoptotic cells. The Annexin V/PI staining was analyzed by flow cytometry at the Flow Cytometry Core of the University of Michigan.

Anoikis Assay

Anoikis was induced by culturing cells in polyHEMA-coated plates according to published procedures (23). Briefly, a 12% solution of poly-HEMA in 95% ethanol was mixed overnight, clarified by centrifugation at 2500 rpm and diluted 1:10 in 95% ethanol. Dishes were coated with the diluted poly-HEMA solution (4 ml per 100-mm plate or 100μl per well of 96-well microplate). 1×104 cells in 100μl serum deprived medium were seeded into each well. WST-1 and Caspase 3/7 activity assays were performed after 24 h as described above.

Anchorage-independent Growth Assay

Soft agar assay was performed in 6-well microplate using a 2ml basal layer of 0.6% agarose in Ham’s F-12 medium. 5×103 MCF10A cells (stable CCN6-KD cells or control cells) were seeded in 1ml cell layer containing 0.3% agarose in complete or serum deprived medium. Plates were maintained at 37°C for 3 weeks. To quantify the colonies, the plates were stained with 0.5ml of 0.005% Crystal Violet for 2 hours and observed under an inverted microscope (Leica Microsystems, Houston, TX). Each condition was performed in triplicates. Colonies were quantified under 250×magnification using NIH Image J.

Invasion assay

In vitro invasion was performed using 24-well plate Biocoat Growth Factor Reduced Matrigel Invasion Chambers (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) according to the manufacturer’s procedures, in triplicate.

Human breast tissue samples, immunohistochemistry and statistical analyses

A high-density tissue microarray (TMA) containing 118 primary invasive carcinomas of the breast developed and characterized by our group was employed (24). A 5μ-thick section was co-immunostained with rabbit polyclonal anti-CCN6 antibody (Orbigen, Cat# PAB-11197, 1:300) and rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-Akt-1 (Ser473) (Millipore, Cat# 07-310, 1:150) following standard biotin-avidin complex technique (24). Staining for CCN6 was visualized in red with Vulcan Red (Biocare Medical); and staining for phospho-Akt-1 (Ser473) was visualized brown with the DAB+ Kit (DakoCytomation). Expression of CCN6 and phospho-Akt-1 (Ser473) was evaluated as either low or high based on intensity of staining and percentage of staining cells, and following published literature (5, 6, 25). Chi-Square test was performed to analyze the association between phospho-Akt-1 (Ser473) and CCN6 protein expression. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

CCN6 knockdown confers growth factor-independent survival to mammary epithelial cells

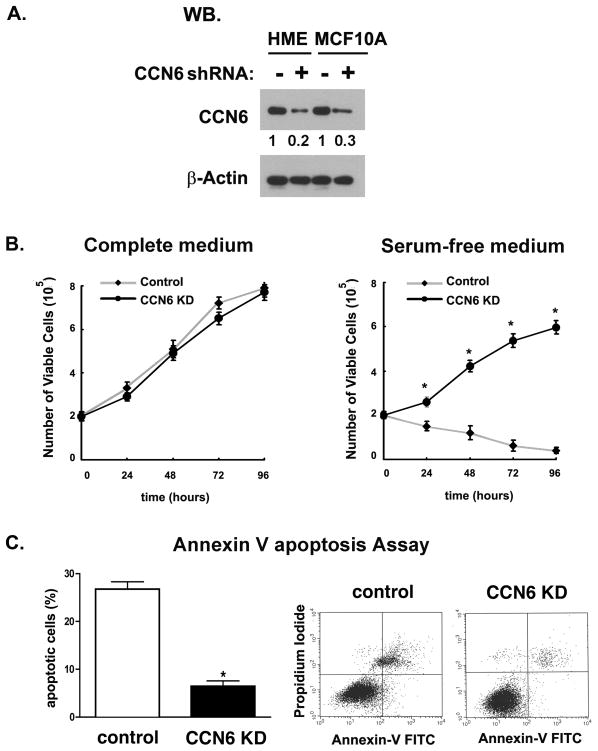

To determine the oncogenic phenotype of reduced or absent CCN6 expression in human breast epithelial cells, we generated stable CCN6 KDs in MCF10A and HME cells using short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) in lentiviral vectors. Control cells were transduced with a lentivirus containing scrambled shRNA sequences (Figure 1A). MCF10A and HME cell lines were chosen for CCN6 downregulation because they are human, mostly diploid, and nontumorigenic. A well-known characteristic of MCF10A and HME mammary epithelial cells is their growth factor requirement for cellular proliferation (26). Growth factor–independent proliferation is a common hallmark in cancer cells containing oncogenic phenotypes and aberrantly activated signaling (26). We analyzed cell survival in MCF10A CCN6 KD and control cells at 0, 24, 36, 72, and 96 hours employing a Trypan blue assay. While CCN6 KD and control mammary epithelial cells were able to grow at similar levels in complete medium, only CCN6 KD cells survived under serum deprivation (Figure 1B). This result was further strengthened by analysis of apoptosis with the Annexin V assay and flow cytometry. Under serum deprivation, CCN6 downregulation caused a 5-fold reduction in the percentage of apoptotic cells compared to controls (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. CCN6 knockdown confers growth factor independent survival to mammary epithelial cells.

A. Western blot analysis of CCN6 protein level on nontumorigenic mammary epithelial cells following lentiviral transduction with shRNA-CCN6 or scrambled controls. β-Actin was used as loading control. The numbers underneath each band indicate the fold change in intensity of the corresponding band relative to the control. B. Effect of CCN6 KD on cell viability of MCF10A cells cultured in complete medium and in serum deprivation medium by the Trypan blue assay. C. MCF10A CCN6 KD and control cells were incubated in serum deprivation medium for 24h. Cell apoptosis assay was performed by Annexin V/PI assay and analyzed by flow cytometry. The number of apoptotic cells is shown by the histogram (left) and two pictograms (right). Each bar represents the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate samples. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. * p< 0.001 (CCN6 KD cells vs. control).

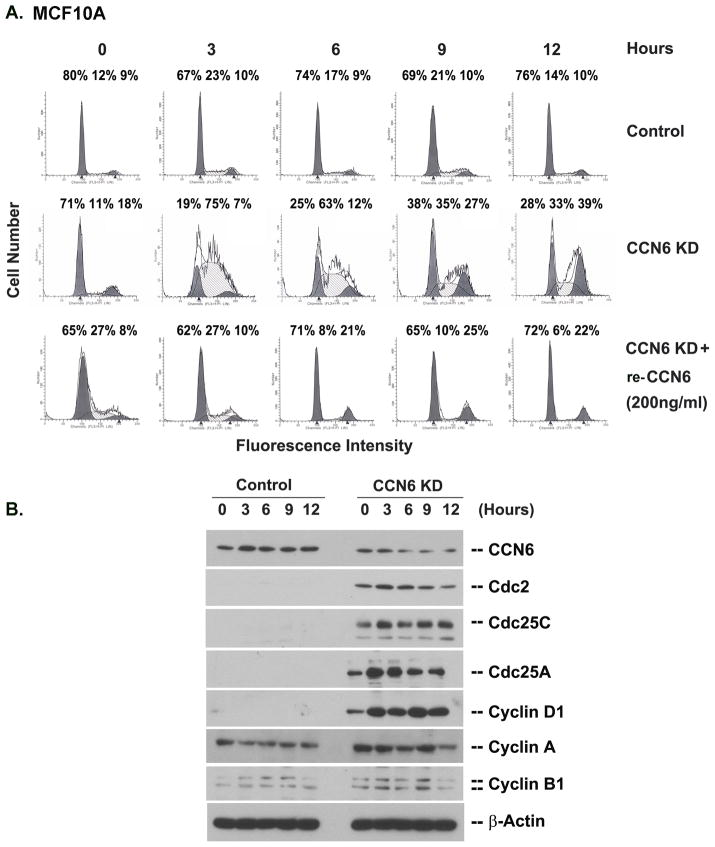

To determine if the improved cell growth of CCN6 KD cells under serum deprivation was associated with differences in cell cycling, we performed DNA content analysis by flow cytometry. As expected, synchronized, serum starved control MCF10A cells exhibited a block at the G1/S boundary. In contrast, CCN6 KD cells failed to arrest and progressed through the cell cycle overcoming the growth arrest conditions (Figure 2A). Treatment with recombinant CCN6 protein blocked the cell cycle progression induced by CCN6 KD. The growth factor independent cell cycle progression of CCN6 KD cells was associated with increased levels of G1/S transition regulatory proteins (Figure 2B). Similar results were obtained with HME cells (Supplementary Fig. 1). Collectively, these data show that the increased viability and proliferation of CCN6 KD mammary epithelial cells under serum deprivation result from both resistance to apoptosis and cell cycle progression.

Figure 2. Mammary epithelial cells with CCN6 KD fail to arrest under serum deprivation.

A. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of serum starved MCF10A CCN6 KD cells and controls, with or without CCN6 recombinant protein (200ng/ml) based on PI staining at increasing collection times (0–12 h). DNA histograms for each specified time point are representative of three independent cell cycle analyses. Corresponding values for each cell population (G1, S, and G2) are expressed as percentages of cells found within each phase of the cell cycle. Note the failure of CCN6 KD MCF10A cells to arrest under serum deprivation, which was reverted by treatment with CCN6 protein. B. Lysates of G1/S-synchronized MCF10A CCN6 KD and controls were analyzed by immunoblot with antibodies against the G1/S transition regulators shown in the figure. β-Actin serves as the loading control.

CCN6 knockdown protects cells from anoikis and promotes anchorage independent growth under serum deprivation

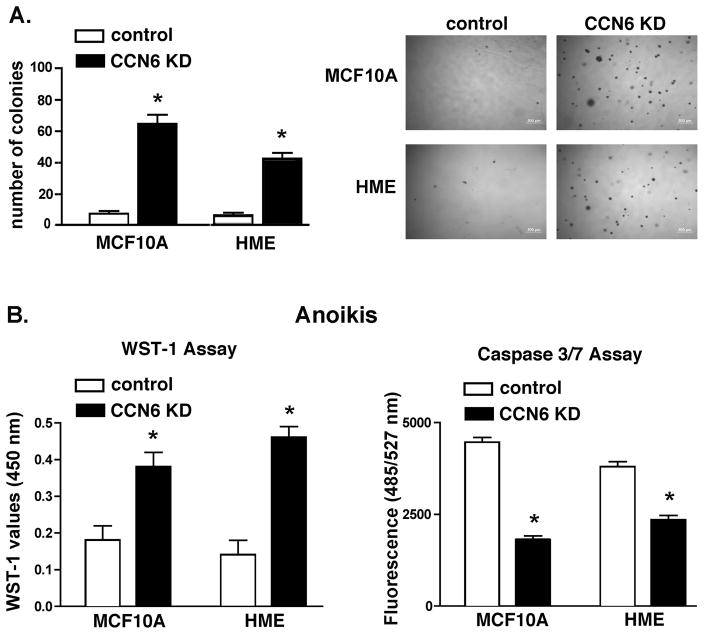

We next investigated the effect of CCN6 downregulation on anchorage independent growth, a characteristic of neoplastic transformation. MCF10A and HME CCN6 KD cells and controls were plated in soft agar and incubated for 21 days in serum deprivation medium. CCN6 KD significantly increased the number of colonies in soft agar (Figure 3A), indicating that besides enhancing survival, CCN6 loss promotes anchorage independent growth in the absence of exogenous growth factors in the media.

Figure 3. CCN6 reduction promotes anchorage independent growth and protects mammary epithelial cells from anoikis under serum deprivation.

A. MCF10A and HME cells were tested for their ability to grow in soft agar under serum deprivation. Colonies greater than or equal to 100 μm in diameter were counted utilizing Image J software. Bar graph shows the mean number of colonies ± standard deviation. Each assay was performed in triplicate. Representative images from soft agar assay plates are shown. B. Above cell lines were grown in serum deprivation medium using poly-HEMA-coated plates for 24h. Cell survival was analyzed by WST-1 assay (left). Cell apoptosis was determined by Caspase 3/7 activity assay (right). Bars show the mean ± standard deviation; experiments were performed in triplicate. * represents p<0.001 (CCN6 KD vs. controls).

We reasoned that the ability to grow under anchorage-independent conditions may be a direct consequence of anoikis resistance, critical to breast cancer progression and metastasis (21). CCN6 KD and controls were placed on poly-HEMA coated plates to prevent cell attachment, and analyzed for cell proliferation and apoptosis using WST-1 and Caspase 3/7 assays. Figure 3B shows that CCN6 KD induced anoikis resistance in MCF10A and HME cells after 48 h in suspension under serum deprivation.

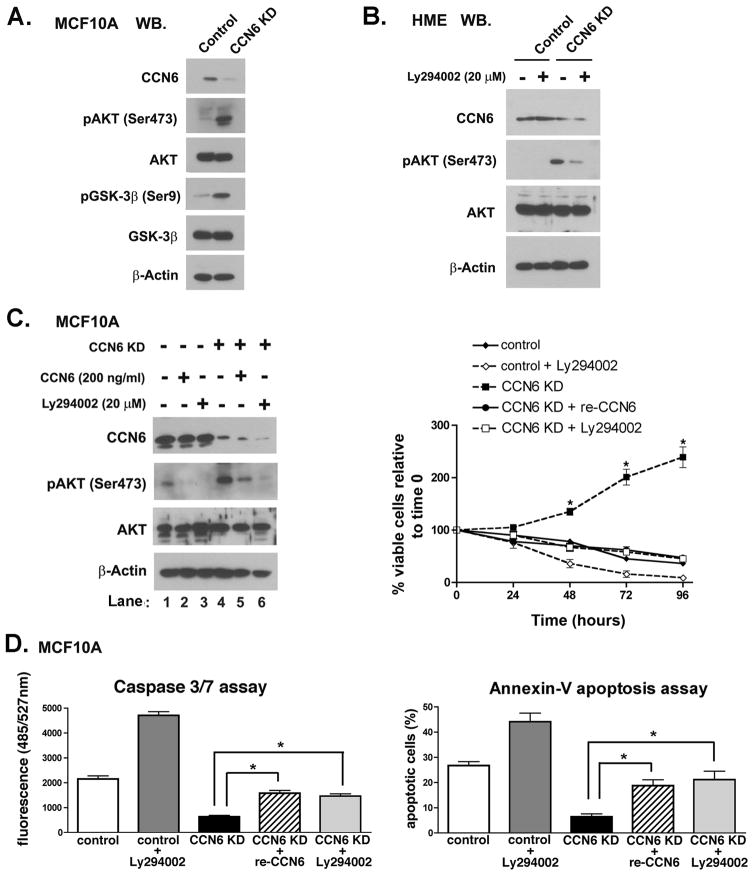

Growth factor-independent survival due to CCN6 knockdown requires activation of PI3K/Akt

As the PI3K/Akt pathway plays a central role in breast cancer cell survival (14, 16–19), we hypothesized that its activation may mediate the observed survival advantage upon CCN6 downregulation. As shown in Figure 4A and B, CCN6 KD in HME and MCF10A cells caused increased phosphorylation at serine 473 of Akt, which is required to promote its maximal activation. The increased Akt (Ser473) phosphorylation induced by CCN6 KD was also evident when cells were cultured in low-attachment poly-HEMA coated plates (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 4. CCN6 knockdown requires activation of PI3K/Akt pathway to increase cell survival and inhibit apoptosis.

A. Immunoblot analyses of MCF10A cells with CCN6 KD and controls reveals increased phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 and one of its downstream molecules. B. Immunoblot of HME cells with CCN6 KD shows increased p-Akt Ser473, similar to MCF10A cells. Specific inhibition of PI3K/Akt pathway with LY294002 (20μM) can reverse the upregulation of p-Akt Ser473 induced by CCN6 KD. C. Immunoblots of MCF10A CCN6 KD cells and controls under serum deprivation for 48 h, in the absence or presence of recombinant CCN6 (200ng/ml) or LY294002 (20μM). CCN6 KD upregulates pAkt Ser473 (lane 4). Treatment with CCN6 protein (lane 5) reduces pAkt Ser473 in CCN6 KD cells. Addition of LY294002 (lane 6) reduces pAkt Ser473 to nearly undetectable levels. Cells were tested for their ability to survive by the Trypan blue assay in serum deprivation at the specified time points. Treatment with recombinant CCN6 protein or Ly294002 rescue the survival advantage of CCN6 KD. D. Cells were subjected to Caspase 3/7 and Annexin V assays. Treatment with recombinant CCN6 protein or Ly294002 rescue the apoptosis resistance of CCN6 KD. Bars show the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. * represents p<0.001 (CCN6 KD vs. all of other experimental groups).

The significance of the PI3K/Akt pathway for cell survival of CCN6 KD mammary epithelial cells was next evaluated in a series of time course experiments measuring cell viability in serum-free medium, in the presence or absence of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 and/or recombinant CCN6 protein. To verify inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway by LY294002 and recombinant CCN6 protein, immunoblots were carried out. In the absence of the PI3K inhibitor or CCN6 recombinant protein, CCN6 KD displayed high levels of pAkt Ser473 (Figure 4C, lane 4). Following LY294002 treatment, pAkt expression dropped to almost undetectable levels (Figure 4C, lane 6). After treatment with recombinant CCN6 protein, CCN6 KD cells showed a significant decrease in pAkt levels (Figure 4C, lane 5).

Survival curves for MCF10A CCN6 KD and controls in the presence of LY294002 (20 μM) and/or recombinant CCN6 protein (200 ng/ml) show that treatment with LY294002 abrogated the CCN6 KD-induced cell survival effects. Likewise, addition of recombinant CCN6 protein compromised the survival advantage conferred by CCN6 KD on mammary epithelial cells (Figure 4C).

We next tested the hypothesis that PI3K/Akt is also required for the resistance to apoptosis induced by CCN6 KD. We performed two apoptosis assays; Annexin V and Caspase 3/7 cleavage in the absence and presence of LY294002 and/or recombinant CCN6 protein. Given the multiple functions of PI3K/Akt in cell survival, it is not surprising that treatment with LY294002 increased apoptosis of MCF10A control cells. However, LY294002 treatment of CCN6 KD cells rescued the effects of CCN6 KD on apoptosis to levels similar to controls and to cells treated with recombinant CCN6 protein (Figure 4D). Altogether, these results demonstrate that CCN6 protein can rescue the survival and apoptotic effects of CCN6 KD in mammary epithelial cells, and that the activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway is essential in the cell survival mechanism of CCN6.

Akt-1 is the main Akt isoform mediating CCN6 effect on survival

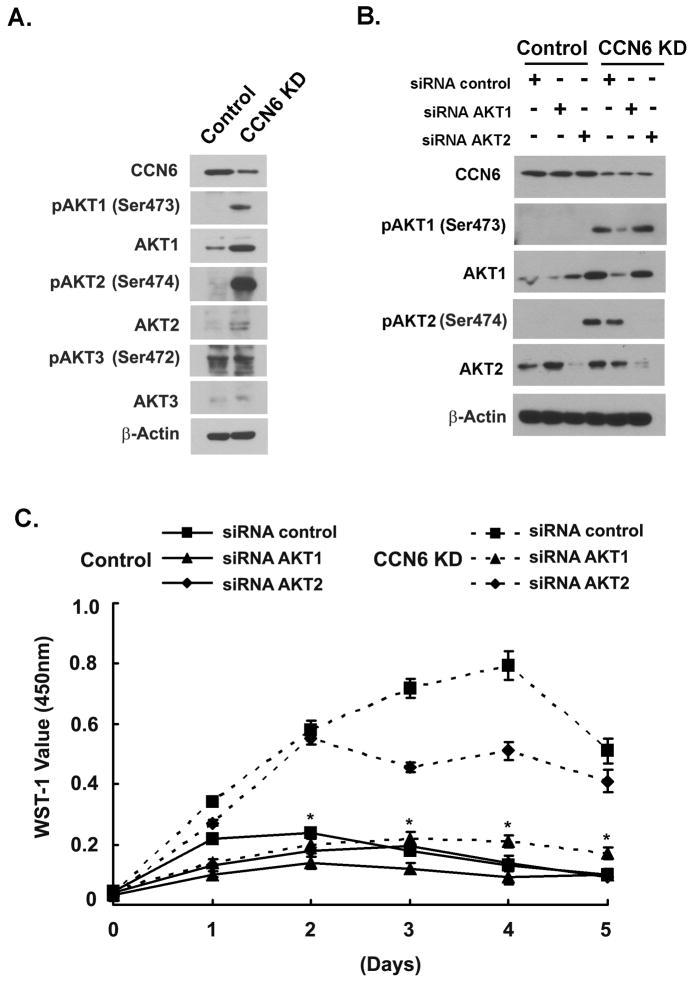

Three Akt isoforms have been characterized to date in mammalian cells: Akt-1 (PKBα), Akt-2 (PKBβ), and Akt-3 (PKBγ) (27, 28), all of which are serine-threonine kinases. Studies have shown that the physiological relevance and function of the individual isoforms are distinct (27, 28). To further define which Akt isoform transduced the survival signal of CCN6 downregulation, we investigated the effect of CCN6 KD on the levels and phosphorylation of Akt-1, Akt-2, and Akt-3. CCN6 KD in mammary epithelial cells increased the levels of Akt-1 and Akt-2 but did not influence Akt-3 expression or phosphorylation, compared to controls (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Inhibition of Akt-1 suppresses proliferation of CCN6 knockdown mammary epithelial cells in serum deprivation medium.

A. MCF10A CCN6 KD and controls were grown in serum deprivation medium for 24h. Expression of the mammalian Akt isoforms: Akt-1, Akt-2 and Akt-3, and their respective phosphorylated forms were analyzed by isoform-specific antibodies. β-Actin was used as loading control. B. Immunoblot analysis of Akt isoforms and their phosphorylated proteins following transient transfection for 48 h under serum deprivation with the indicated siRNA oligos and scrambled controls. C. Cells described in B were re-seeded in 96-well plates and analyzed for cell proliferation using the WST-1 assay. Viable cell number was monitored at specified time points. Note that siRNA inhibition of Akt-1, but not Akt-2, is able to completely revert the proliferation advantage of CCN6 KD MCF10A cells transfected with the scrambled siRNA control. The assay was repeated three independent times. Points, mean of three independent experiments done in triplicate ± standard deviation. * represents p<0.001 (CCN6 KD/siRNA controls vs. CCN6 KD/siRNA Akt-1).

Studies in cultured cells and murine models have identified potentially specific actions of each Akt isoform in breast cancer (29–32). It has been recently shown that while Akt-1 plays an important role in mammary tumor growth, Akt-2 is mainly involved in breast cancer invasion and metastasis (30–32). We hypothesized that CCN6 KD may promote survival of mammary epithelial cells through specific activation of Akt-1. We further hypothesized that Akt-2 may mediate the previously reported invasion effects of CCN6 (5, 7, 22, 33). To test these hypotheses, we employed siRNAs to transiently downregulate Akt-1 or Akt-2 on CCN6 KD mammary epithelial cells and controls. Specific blockade of Akt-1 completely reverted the increased growth factor- independent proliferation of CCN6 KD cells compared to siRNA control cells (Figure 5B and C, and Supplementary Figure 3). This contrasts with the modest decrease in proliferation observed upon Akt-2 inhibition on CCN6 KD cells compared to siRNA control cells (Figure 5B and C, and Supplementary Figure 3). These data show that the survival mechanism induced by CCN6 KD requires principally Akt-1. We also noted that inhibition of Akt-1 and Akt-2 decreased at least in part CCN6 KD-mediated invasion in mammary epithelial cells (Supplementary Figure 4).

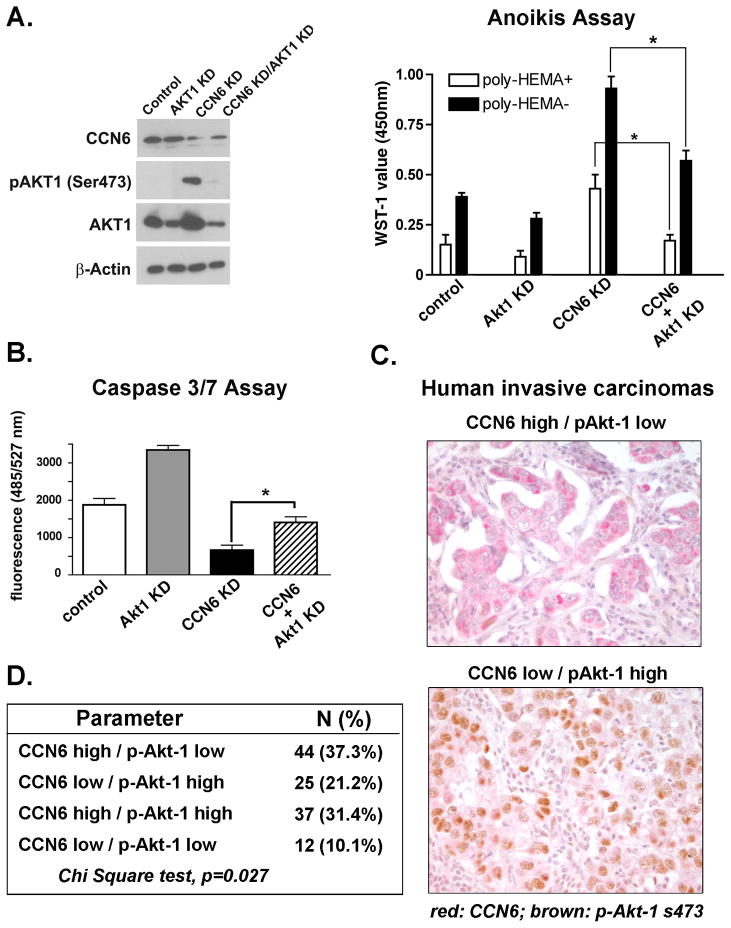

To provide further evidence for a role for Akt-1 in the increased cell survival conferred by CCN6 KD, we developed stable short hairpin shRNAs targeting Akt-1 in lentivirus and stably transduced them into CCN6 KD cells and controls. Effective shRNA downregulation of Akt-1 was confirmed by immunoblots (Figure 6A). Akt-1 shRNA significantly reduced the proliferation of CCN6 KD cells either attached or when grown in poly-HEMA coated plates (Figure 6A). Akt-1 shRNA also reverted the reduced levels of cleaved Caspase 3 and 7 resulting from CCN6 KD (Figure 6B). Taken together, these results indicate that Akt-1 is the principal isoform mediating the growth advantage of CCN6 KD in mammary epithelial cells. Our data show that the ability of CCN6 KD cells to resist anoikis and survive in suspension necessitates Akt-1.

Figure 6. Inhibition of Akt-1 rescues anoikis and apoptosis resistance in CCN6 knockdown mammary epithelial cells.

A. MCF10A cells with CCN6 KD, Akt-1 KD, CCN6/Akt-1 double KD, and corresponding control cells were grown in serum deprivation medium for 24h. Western blot analyses of phospho-Akt-1 and total Akt-1 levels are shown. Cell lines were grown in serum deprivation medium, with or without poly-HEMA-coated treatment, for 24h. Cell survival was assayed by WST-1 assay. Akt-1 KD rescues the increased proliferation conferred by CCN6 KD in attached or detached mammary epithelial cells. B. Cell apoptosis was determined by Caspase 3/7 activity assay. Akt-1 KD rescues the decrease in apoptosis induced by CCN6 KD in mammary epithelial cells to levels similar to controls. Error bars represent means± standard deviation. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. * p< 0.001 (CCN6 KD cells vs. control or CCN6 KD/Akt-1 double KD cells). C. Human breast cancer tissue samples (n=118) co-immunostained for CCN6 (red) and phosphoAkt-1 Ser473 (brown). Representative invasive ductal carcinoma with high CCN6 expression and low phospho-Akt-1 (LEFT), and another tumor with low CCN6 protein and high phospho-Akt-1 (RIGHT). D. This table shows the distribution of CCN6 and phospho-Akt-1 protein expression in our cohort of 118 consecutive primary invasive carcinomas of the breast. We discovered a significant association between CCN6 and phopho-Akt-1 proteins, Chi Square test, p=0.027.

CCN6 downregulation is associated with increased Akt-1 phosphorylation in human invasive breast carcinomas

To assess the relevance of our in vitro studies to human breast cancer, we simultaneously investigated the expression of CCN6 and phospho-Akt-1 proteins in 118 primary invasive carcinoma tissue samples arrayed in a tissue microarray (24). Double immunohistochemical analysis showed that when present, CCN6 protein was predominantly cytoplasmic and that phospho-Akt-1 protein was localized to the nuclei of breast cancer cells (Figure 6C) (5, 6, 25). CCN6 and phospho-Akt-1 were scored as high when over 10% of the cancer cells showed moderate or strong staining and were scored as low when staining was present in less than 10% of tumor cells (5, 6, 25). We found a novel significant association between CCN6 and phospo-Akt-1 protein expression in invasive carcinomas of the breast. Of the 118 tumors, 69 (58.5%) exhibited reciprocal expression of CCN6 and phosphor-Akt-1 proteins (37.3% had high CCN6 and low phospho-Akt-1, and 21.2% had low CCN6 and high phospho-Akt-1), Chi Square test, p=0.027. Expression of both proteins was seen in 37 of 118 tumors (31.4%), and absent CCN6 and phospho-Akt-1 expression occurred in 12 of 118 tumors (10.1%) (Figure 6C and D).

DISCUSSION

This study reveals that CCN6 downregulation provides survival advantage to mammary epithelial cells and point to a new mechanism by which CCN6 downregulation triggers growth factor-independent survival and protects mammary epithelial cells from detachment-induced apoptosis (anoikis). This mechanism implicates the activation of PI3K/Akt-1 signaling pathway.

A fundamental difference between normal and cancer cells is their requirement for extracellular signals (26). While normal cells die upon deprivation of extracellular growth factors, cancer cells have the ability to survive and proliferate in their absence (26). We observed that CCN6 KD was sufficient to increase survival of mammary epithelial cells in serum free conditions. To elaborate these conclusions we investigated the effect of CCN6 on survival under serum deprivation utilizing two complementary approaches, downregulation of CCN6 by shRNAs and treatment with human recombinant CCN6 protein. By measuring cell viability at different time points, it was concluded that mammary epithelial cells transduced with the scrambled shRNA were unable to proliferate under serum deprivation; rather, they underwent apoptosis. In contrast, CCN6 KD cells not only survived under serum deprivation but continued to grow after 4 days, while exhibiting significantly decreased apoptosis. Treatment with recombinant CCN6 protein completely reverted the growth and survival effects of CCN6 KD.

CCN6 KD had a striking effect on cell cycle progression. CCN6 downregulation resulted in failure to cell cycle block under growth arrest conditions. Treatment of CCN6 KD cells with recombinant CCN6 protein rescued this effect and restored the G1/S boundary block in serum deprived mammary epithelial cells. These data not only reveal a novel cell cycle function of CCN6, but strongly suggest that the cell cycle delay function may be important for the reported tumor suppressive role of CCN6 in breast cancer (7).

Our group has previously reported that CCN6 loss is associated with a highly metastatic form of invasive breast carcinoma termed inflammatory breast cancer, as well as with non-inflammatory invasive breast cancers with lymph node metastasis (5, 11). Data presented here show that CCN6 regulates a crucial step in metastatic dissemination: the acquisition of resistance to detachment-induced apoptosis (anoikis). Resistance to anoikis allows cancer cells to survive after detachment from the matrix and facilitates survival in lymphatic and blood vessels (21, 34). CCN6 KD in MCF10A and HME cells is sufficient to prevent anoikis and promote growth under anchorage independent conditions in the absence of exogenous growth factors. The induction of anoikis resistance may contribute to the enhanced metastases observed in invasive carcinomas with low CCN6 protein expression.

The serine/threonine kinase Akt has been identified as a major effector of PI3K in the promotion and maintenance of cell survival, being able to act on cell proliferation and on the suppression of apoptosis and anoikis pathways (14, 16–19). By utilizing independent and complementary strategies including pharmacologic, transient and stable RNA interference we provide compelling evidence that the survival advantage and resistance to apoptosis and anoikis induced by CCN6 KD necessitate the activation of PI3K/Akt signaling. To understand the specific contribution of each Akt isoform on the survival mechanism triggered by CCN6 downregulation, we undertook two approaches: transient and stable downregulation of Akt-1 and Akt-2 in CCN6 KD cells and controls. Our data show that the growth factor-independent survival triggered by CCN6 KD requires principally phosphorylation of Akt-1. Both transient and stable Akt-1 inhibition reverted the pro-survival and anti-apoptotic and anoikis effects of CCN6 KD in mammary epithelial cells. The relevance of the novel mechanistic association between CCN6 and phospho-Akt-1 proteins to human breast cancer is highlighted by the finding that 37.3% of primary invasive carcinomas exhibited high CCN6 and low phospho-Akt-1, and that 21.2 % exhibited low CCN6 and high phospho-Akt-1 proteins. We found that 31.4% had high levels and 10.1 % had low levels of both proteins.

Despite the observation that CCN6KD induced upregulation of Akt-2 phosphorylation at Ser472, our experiments show that Akt-2 appears to have a dispensable role in mediating the survival effects of CCN6. Although more work is needed for further understand the contribution of Akt-2 to CCN6 function, our preliminary studies suggest that Akt-2 may play a role in mediating the invasive phenotype of CCN6 KD cells.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate a previously undescribed function of CCN6 during breast tumorigenesis. We have identified that CCN6 KD promotes growth factor independent survival of benign breast cells, and is sufficient to induce anchorage independent growth and anoikis resistance under serum deprivation. Our results enable us to pinpoint one mechanism by which CCN6 controls survival of breast cells, implicating the PI3K/Akt-1 pathway. We show that Akt-1 activation is indispensable for driving CCN6-mediated growth factor- independent survival of mammary epithelial cells. In view of our results and based on the profound effects of exogenously added recombinant CCN6 protein, we propose that modulation of CCN6 levels may be a valid strategy to prevent or halt neoplastic progression in the breast.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by NIH grants CA090876 (CGK), CA107469 (CGK), a grant from the Avon Foundation (CGK), and support from the Fashion Footwear Charitable Foundation of New York/QVC Presents Shoes on Sale™.

References

- 1.Holbourn KP, Acharya KR, Perbal B. The CCN family of proteins: structure-function relationships. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:461–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perbal B. NOV (nephroblastoma overexpressed) and the CCN family of genes: structural and functional issues. Mol Pathol. 2001;54:57–79. doi: 10.1136/mp.54.2.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perbal B. The CCN3 protein and cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;587:23–40. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-5133-3_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleau AM, Planque N, Perbal B. CCN proteins and cancer: two to tango. Front Biosci. 2005;10:998–1009. doi: 10.2741/1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang W, Zhang Y, Varambally S, et al. Inhibition of CCN6 (Wnt-1-induced signaling protein 3) down-regulates E-cadherin in the breast epithelium through induction of snail and ZEB1. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:893–904. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleer CG, Zhang Y, Pan Q, Merajver SD. WISP3 (CCN6) is a secreted tumor-suppressor protein that modulates IGF signaling in inflammatory breast cancer. Neoplasia. 2004;6:179–85. doi: 10.1593/neo.03316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kleer CG, Zhang Y, Pan Q, et al. WISP3 is a novel tumor suppressor gene of inflammatory breast cancer. Oncogene. 2002;21:3172–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franzen CA, Chen CC, Todorovic V, Juric V, Monzon RI, Lau LF. Matrix protein CCN1 is critical for prostate carcinoma cell proliferation and TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1045–55. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin MT, Kuo IH, Chang CC, et al. Involvement of hypoxia-inducing factor-1alpha-dependent plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 up-regulation in Cyr61/CCN1-induced gastric cancer cell invasion. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15807–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708933200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 10.Vallacchi V, Rodolfo M. Regulatory role of CCN3 in melanoma cell interaction with the extracellular matrix. Cell Adh Migr. 2009:3. doi: 10.4161/cam.3.1.6836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Golen KL, Davies S, Wu ZF, et al. A novel putative low-affinity insulin-like growth factor-binding protein, LIBC (lost in inflammatory breast cancer), and RhoC GTPase correlate with the inflammatory breast cancer phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2511–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dudek H, Datta SR, Franke TF, et al. Regulation of neuronal survival by the serine-threonine protein kinase Akt. Science. 1997;275:661–5. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennedy SG, Kandel ES, Cross TK, Hay N. Akt/Protein kinase B inhibits cell death by preventing the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5800–10. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dillon RL, White DE, Muller WJ. The phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase signaling network: implications for human breast cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:1338–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cully M, You H, Levine AJ, Mak TW. Beyond PTEN mutations: the PI3K pathway as an integrator of multiple inputs during tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:184–92. doi: 10.1038/nrc1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gottlieb TM, Leal JF, Seger R, Taya Y, Oren M. Cross-talk between Akt, p53 and Mdm2: possible implications for the regulation of apoptosis. Oncogene. 2002;21:1299–303. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khwaja A, Rodriguez-Viciana P, Wennstrom S, Warne PH, Downward J. Matrix adhesion and Ras transformation both activate a phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase and protein kinase B/Akt cellular survival pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:2783–93. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu Y, Lin YZ, LaPushin R, et al. The PTEN/MMAC1/TEP tumor suppressor gene decreases cell growth and induces apoptosis and anoikis in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:7034–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frisch SM, Screaton RA. Anoikis mechanisms. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:555–62. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moro L, Arbini AA, Yao JL, di Sant’Agnese PA, Marra E, Greco M. Mitochondrial DNA depletion in prostate epithelial cells promotes anoikis resistance and invasion through activation of PI3K/Akt2. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:571–83. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Douma S, Van Laar T, Zevenhoven J, Meuwissen R, Van Garderen E, Peeper DS. Suppression of anoikis and induction of metastasis by the neurotrophic receptor TrkB. Nature. 2004;430:1034–9. doi: 10.1038/nature02765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Pan Q, Zhong H, Merajver SD, Kleer CG. Inhibition of CCN6 (WISP3) expression promotes neoplastic progression and enhances the effects of insulin-like growth factor-1 on breast epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Research. 2005;7:R1080–89. doi: 10.1186/bcr1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu LH, Yang X, Bradham CA, et al. The focal adhesion kinase suppresses transformation-associated, anchorage-independent apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Involvement of death receptor-related signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30597–604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910027199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleer CG, Cao Q, Varambally S, et al. EZH2 is a marker of aggressive breast cancer and promotes neoplastic transformation of breast epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11606–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1933744100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stal O, Perez-Tenorio G, Akerberg L, et al. Akt kinases in breast cancer and the results of adjuvant therapy. Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5:R37–44. doi: 10.1186/bcr569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Testa JR, Bellacosa A. AKT plays a central role in tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10983–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211430998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Datta SR, Brunet A, Greenberg ME. Cellular survival: a play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2905–27. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ju X, Katiyar S, Wang C, et al. Akt1 governs breast cancer progression in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7438–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605874104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dillon RL, Marcotte R, Hennessy BT, Woodgett JR, Mills GB, Muller WJ. Akt1 and akt2 play distinct roles in the initiation and metastatic phases of mammary tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5057–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hutchinson J, Jin J, Cardiff RD, Woodgett JR, Muller WJ. Activation of Akt (protein kinase B) in mammary epithelium provides a critical cell survival signal required for tumor progression. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2203–12. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.6.2203-2212.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hutchinson JN, Jin J, Cardiff RD, Woodgett JR, Muller WJ. Activation of Akt-1 (PKB-alpha) can accelerate ErbB-2-mediated mammary tumorigenesis but suppresses tumor invasion. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3171–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleer CG, Zhang Y, Merajver SD. CCN6 (WISP3) as a new regulator of the epithelial phenotype in breast cancer. Cells Tissues Organs. 2007;185:95–9. doi: 10.1159/000101308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freedman VH, Shin SI. Cellular tumorigenicity in nude mice: correlation with cell growth in semi-solid medium. Cell. 1974;3:355–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.