Abstract

Objectives: To compare countries in western Europe with respect to class differences in mortality from specific causes of death and to assess the contributions these causes make to class differences in total mortality.

Design: Comparison of cause of death in manual and non-manual classes, using data on mortality from national studies.

Setting: Eleven western European countries in the period 1980-9.

Subjects: Men aged 45-59 years at death.

Results: A north-south gradient was observed: mortality from ischaemic heart disease was strongly related to occupational class in England and Wales, Ireland, Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, but not in France, Switzerland, and Mediterranean countries. In the latter countries, cancers other than lung cancer and gastrointestinal diseases made a large contribution to class differences in total mortality. Inequalities in lung cancer, cerebrovascular disease, and external causes of death also varied greatly between countries.

Conclusions: These variations in cause specific mortality indicate large differences between countries in the contribution that disease specific risk factors like smoking and alcohol consumption make to socioeconomic inequalities in mortality. The mortality advantage of people in higher occupational classes is independent of the precise diseases and risk factors involved.

Key messages

Socioeconomic inequalities in total mortality among middle aged men are about equally large in most western European countries, with the exception of larger inequalities in France and Finland

Inequalities in mortality from specific causes of death, and the contributions these causes make to inequalities in total mortality, vary between countries

The contribution to inequalities in mortality of disease specific risk factors like smoking and alcohol consumption varies greatly between countries

This variability imposes limits on the exchange of research findings and experiences with health policies between western European countries

The similar size of inequalities in total mortality in most countries underlines the generalised ability of higher occupational classes to better avoid premature death

Introduction

Socioeconomic differences in morbidity and mortality have been observed in all European countries for which data are available.1,2 Health inequalities are a common theme in all European countries, but it is uncertain whether this is a theme with major variations.

There are several reasons for an interest in the degree to which health inequalities are similar or dissimilar in the different European countries. Large dissimilarities would imply that socioeconomic inequalities in health are highly sensitive to specific national circumstances. Further study might show which circumstances are most influential and could identify circumstances that could be modified through intervention.

A second reason relates to the international exchange of research findings and experiences with health policies. An example is the findings from explanatory studies, most of which are from the United Kingdom and Nordic countries.1,2 Combining research findings from different countries can provide a more comprehensive picture of the causes of health inequalities, but this is possible only to the extent that the patterns and causes of health inequalities are similar in these countries. Some degree of similarity is also required when extrapolating these findings to other parts of Europe.

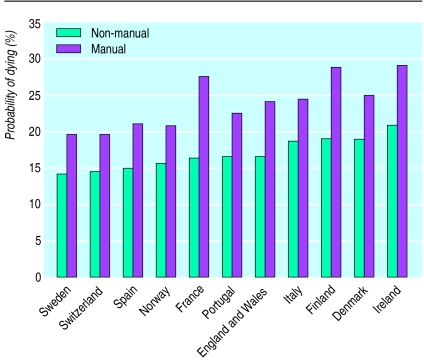

Several studies have compared countries with respect to the magnitude of inequalities in mortality.3–6 We recently found higher mortality in manual classes than non-manual classes in 11 Western European countries.7–9 For men aged 45-59 years, these mortality differences were approximately equal in most countries; larger differences were observed for Finland and, especially, France (fig 1). Larger differences were also observed for Ireland, but only in absolute terms. Class differences in mortality among men aged 30-44 were relatively large in Finland, Sweden, and Norway (no data for France).7–9

Figure 1.

Probability of men in non-manual and manual classes dying between the ages 45 and 657,9

Only a few studies have compared socioeconomic differences in mortality according to cause of death.3,4 A study that compared Hungary to northern Europe found that the association with educational level was relatively weak for cardiovascular disease but relatively strong for other causes of death.3 This suggested that risk factors for cardiovascular disease (for example, tobacco consumption) made a smaller contribution to mortality differences in Hungary than in northern Europe.

The present study compares 11 countries from the northern and southern part of western Europe. It compares occupational class differences in mortality from specific causes of death and assesses the contributions these causes make to class differences in total mortality among men aged 45-59.

Methods

This study is part of a larger project on socioeconomic differences in morbidity and mortality in Europe.7,8 Table 1 shows data sources. Data on mortality by occupational class and cause of death were obtained from longitudinal studies or from cross sectional studies. Longitudinal studies consisted of follow up (of a representative sample) of the national population censuses carried out around 1981. Most follow up studies covered the period 1980-9, but Sweden and Italy had shorter periods. The cross sectional studies were of the “unlinked” type,9 with the death registry providing the number of deaths according to occupational class as registered on death certificates and the population census providing the corresponding number of people at risk according to the same occupational classes. All cross sectional studies were centred on the national population censuses around 1981.

Table 1.

Overview of sources of data

| Country | Design | Period | Populations excluded | Observed No of deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finland | Longitudinal | 1981-90 | None | 39 090 |

| Sweden | Longitudinal | 1980-86 | None | 39 789 |

| Norway | Longitudinal | 1980-90 | None | 22 033 |

| Denmark | Longitudinal | 1981-90 | None | 34 400 |

| England and Wales | Longitudinal | 1981-89 | None | 2 703 |

| Ireland | Cross sectional | 1980-82 | None | 6 348 |

| France | Cross sectional | 1981-83 | French born out of France; foreigners | 133 415 |

| Longitudinal | 1980-89 | French born out of France; foreigners | 15 016 | |

| Switzerland | Cross sectional | 1979-82 | Foreigners | 13 317 |

| Italy | Longitudinal | 1981-82 | Foreigners; people in institutions | 8 325 |

| Spain | Cross sectional | 1980-82 | Military | 70 524 |

| Portugal | Cross sectional | 1980-82 | Military | 22 581 |

The age group 45-59 years was used for studies that classified men according to their age at death. For longitudinal studies with a follow up period of about 10 years, the birth cohort aged 40-54 years at the start of follow up was used

Nine causes of death were distinguished. As shown in table 2, the share of these causes of death in the total number of deaths varies strongly between European countries. Ischaemic heart disease is the largest single cause of death in northern countries. In France and southern countries, cancers other than lung cancer and gastrointestinal diseases are relatively important. Other causes of death have different international patterns.

Table 2.

Proportion of deaths due to specific causes in men aged 45-59

| Country | Lung cancer (ICD 162) | Other cancers (ICD 140-239) | Ischaemic heart disease (ICD 410-414) | Cerebrovascular disease (ICD 430-438) | Other cardiovascular diseases (ICD 390-459) | Respiratory diseases (ICD 460-519) | Gastrointestinal diseases (ICD 520-579) | Other diseases (ICD <800) | External causes (ICD 800-999) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finland (n=39 090) | 7.3 | 13.4 | 35.6 | 6.2 | 6.1 | 3.4 | 4.6 | 5.3 | 18.1 |

| Sweden (n=39 789) | 5.5 | 20.1 | 34.6 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 3.9 | 4.6 | 7.8 | 13.1 |

| Norway (n=22 033) | 7.1 | 19.9 | 34.2 | 4.2 | 5.4 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 10.9 | 11.9 |

| Denmark (n= 34 400) | 9.5 | 19.8 | 26.3 | 4.1 | 5.2 | 3.8 | 5.8 | 14.0 | 11.6 |

| England and Wales (n=2703) | 11.4 | 20.2 | 38.2 | 5.5 | 5.1 | 5.7 | * | 8.0 | 5.8 |

| Ireland (n=6348) | 8.3 | 18.0 | 39.0 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 7.2 | 2.8 | 5.6 | 7.8 |

| France (n=133 415) | 9.2 | 28.8 | 9.9 | 4.5 | 7.4 | 3.4 | 11.3 | 12.4 | 13.2 |

| Switzerland (n=13 317) | 11.9 | 21.5 | 20.7 | 3.5 | 9.8 | 3.4 | 6.4 | 7.8 | 15.0 |

| Italy (n=8325) | ‡ | 36.6 | § | § | 31.8 | 3.3 | 12.8 | 5.7 | 9.6 |

| Spain (n=70 524) | 8.3 | 23.5 | 14.4 | 6.8 | 10.4 | 6.1 | 12.3 | 8.3 | 9.8 |

| Portugal (n=22 581) | 4.2 | 18.7 | 11.3 | 11.4 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 13.2 | 13.4 | 15.4 |

Combined with other diseases.

Combined with other cancers.

Combined with other cardiovascular diseases.

A common occupational class scheme, the EGP (Erikson-Goldthorpe-Portocarero) scheme, was applied to as many countries as possible.10 This scheme was developed to facilitate international comparisons of social stratification and mobility and is therefore particularly suitable for this study. EGP conversion algorithms were applied to individual data on three aspects of jobs: occupational title (by three digit code), employment status (self employed or not), and supervisory status. These conversion schemes could not be applied to the data available for Denmark, Ireland, Italy, Spain, and Portugal, but data from these countries could be made broadly comparable to the EGP scheme at the level of three broad classes: non-manual classes (including self employed men), manual classes, and the class of farmers and farm labourers.

For most countries, there was insufficient information on the former occupation of economically inactive men; these were excluded from the analysis. Because this exclusion is likely to lead to an underestimation of mortality differences between occupational classes, we applied a procedure that gives an approximate correction for this underestimation.8,9 This procedure is based on a formula that calculates correction factors as a function of the population share and the relative mortality level of the men that had to be excluded from analysis. The adjustment was made for each cause of death separately. The formula was found to perform well in several tests.8,9

Mortality differences by occupational class were measured by rate ratios and rate differences. Rate ratios compare mortality in manual classes with mortality in non-manual classes. Rate ratios were estimated by means of Poisson regression. The regression model included a term on the contrast between manual and non-manual classes. A series of terms representing five year age groups were added to control for age.

Rate differences were calculated as the absolute difference between mortality in manual and non-manual classes. Mortality rates were adjusted for age by the indirect method, with national age specific mortality rates as the standard. The rate differences for specific causes of death add up to the rate difference for total mortality. Thus, dividing the rate difference for a specific cause of death by the difference for total mortality yields a measure of the contribution that this cause makes to the rate difference for total mortality.

Results

Table 3 presents manual versus non-manual rate ratios for total mortality and broad groups of cause of death. Rate ratios for total mortality are between 1.33 and 1.44, except for Finland (1.53) and France (1.71). Broad cause of death groups show pronounced variations between countries. Differences are small for neoplasms in Sweden, Norway, Denmark, England and Wales, and Portugal; for cardiovascular diseases in Switzerland and the Mediterranean countries; and for external causes of death in Norway, Denmark, Switzerland, and Italy.

Table 3.

Mortality rate ratio (95% confidence interval) comparing manual classes to non-manual classes for major groups of causes of death in men aged 45-59

| Country | All causes | Neoplasms | Cardiovascular diseases | All other diseases | External causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finland | 1.53 (1.49 to 1.56) | 1.39 (1.32 to 1.47) | 1.48 (1.42 to 1.53) | 1.60 (1.48 to 1.70) | 1.76 (1.66 to 1.87) |

| Sweden | 1.41 (1.38 to 1.44) | 1.18 (1.13 to 1.23) | 1.36 (1.31 to 1.40) | 1.83 (1.72 to 1.93) | 1.76 (1.65 to 1.87) |

| Norway | 1.34 (1.30 to 1.39) | 1.25 (1.18 to 1.33) | 1.34 (1.27 to 1.40) | 1.51 (1.40 to 1.63) | 1.42 (1.29 to 1.54) |

| Denmark | 1.33 (1.30 to 1.36) | 1.21 (1.16 to 1.26) | 1.28 (1.23 to 1.33) | 1.62 (1.54 to 1.70) | 1.36 (1.27 to 1.45) |

| England and Wales | 1.44 (1.33 to 1.56) | 1.21 (1.05 to 1.39) | 1.52 (1.36 to 1.71) | 1.74 (1.40 to 2.16) | 1.74 (1.24 to 2.46) |

| Ireland | 1.38 (1.30 to 1.46) | 1.39 (1.24 to 1.55) | 1.27 (1.17 to 1.38) | 1.66 (1.43 to 1.93) | 1.66 (1.33 to 2.07) |

| France* | 1.71 (1.66 to 1.77) | 1.71 (1.61 to 1.82) | 1.35 (1.26 to 1.45) | 2.09 (1.97 to 2.22) | 1.72 (1.57 to 1.88) |

| Switzerland | 1.35 (1.29 to 1.39) | 1.44 (1.35 to 1.54) | 1.08 (1.01 to 1.15) | 1.75 (1.60 to 1.91) | 1.39 (1.26 to 1.53) |

| Italy | 1.35 (1.28 to 1.42) | 1.43 (1.31 to 1.55) | 1.17 (1.07 to 1.28) | 1.60 (1.43 to 1.80) | 1.22 (1.03 to 1.46) |

| Spain | 1.37 (1.34 to 1.39) | 1.33 (1.29 to 1.38) | 1.19 (1.15 to 1.22) | 1.52 (1.46 to 1.57) | 1.80 (1.68 to 1.93) |

| Portugal | 1.36 (1.31 to 1.40) | 1.12 (1.05 to 1.21) | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.10) | 1.65 (1.55 to 1.76) | 2.15 (1.94 to 2.38) |

Confidence intervals for specific causes of death are estimates.

Table 4 presents manual versus non-manual rate ratios for specific causes of death. Mortality from ischaemic heart disease was strongly related to low occupational class in England and Wales, Ireland, and the Nordic countries. France, Switzerland, and Spain showed large differences for cancers other than lung cancer. Class differences in mortality from lung cancer were largest in Finland and Ireland; differences for cerebrovascular disease were largest in England and Wales; and those for gastrointestinal diseases were largest in France and Italy.

Table 4.

Mortality rate ratio comparing manual classes to non-manual classes for specific causes of death in men aged 45-59

| Country | Lung cancer | Other cancers | Ischaemic heart disease | Cerebrovascular disease | Other cardiovascular disease | Respiratory disease | Gastrointestinal causes | Other diseases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finland | 2.20* | 1.14* | 1.47* | 1.55* | 1.52* | 2.37* | 1.37* | 1.50* |

| Sweden | 1.46* | 1.11* | 1.36* | 1.31* | 1.42* | 1.91* | 1.58* | 1.95* |

| Norway | 1.62* | 1.15* | 1.35* | 1.21* | 1.31* | 1.68* | 1.42* | 1.49* |

| Denmark | 1.51* | 1.09* | 1.28* | 1.28* | 1.28* | 2.30* | 1.65* | 1.48* |

| England and Wales | 1.54* | 1.07 | 1.50* | 1.74* | 1.46* | 2.13* | † | 1.49* |

| Ireland | 1.95* | 1.17* | 1.23* | 1.57* | 1.40 | 2.00* | 1.08 | 1.67* |

| France | 1.65* | 1.75* | 1.14 | 1.61* | 1.54* | 2.63* | 2.20* | 1.89* |

| Switzerland | 1.73* | 1.29* | 0.96 | 1.43* | 1.26 | 2.31* | 1.62* | 1.69* |

| Italy‡ | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | 1.63* | 1.78* | 1.23 |

| Spain | 1.38* | 1.31* | 0.98 | 1.18* | 1.68* | 1.89* | 1.43* | 1.42* |

| Portugal | 1.07 | 1.15* | 0.76* | 1.44* | 1.14 | 2.13* | 1.59* | 1.54* |

P<0.05 for difference from 1.00.

Combined with other diseases.

No distinction could be made between specific neoplasms or specific cardiovascular diseases.

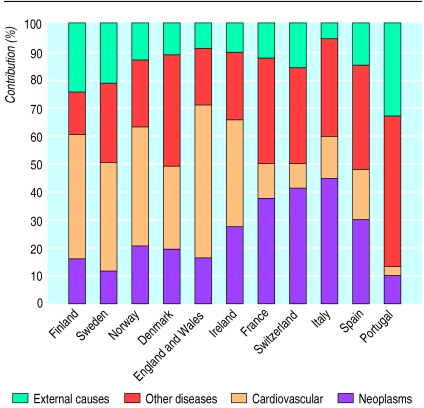

Figure 2 presents the contribution that broad groups of causes of death make to the difference in total mortality between manual and non-manual workers. Neoplasms contribute 27-44% of mortality differences in Ireland, France, Switzerland, Italy, and Spain. Cardiovascular diseases contribute 30-54% of the mortality differences in England and Wales, Ireland, and the Nordic countries. The contribution of external causes ranges from less than 10% in Italy and England and Wales to 21% in Sweden, 24% in Finland, and 33% in Portugal.

Figure 2.

Contribution of broad causes of death to difference in total mortality of men aged 45-59 in manual and non-manual classes

Table 5 shows the contributions made by specific causes of death. The north-south gradient in the contribution of cardiovascular diseases can be attributed to ischaemic heart disease. In southern countries, a large part of the mortality difference between manual and non-manual classes is due to cancers other than lung cancer and gastrointestinal diseases. The contributions made by lung cancer were largest in Ireland and Switzerland; those made by cerebrovascular disease were largest in England and Wales, Ireland, and Portugal; and those made by respiratory diseases were largest in Ireland and Portugal.

Table 5.

Contribution (percentage) of specific causes of death to the difference between manual and non-manual classes in total mortality. Men 45-59 years

| Country | Lung cancer | Other cancers | Ischaemic heart disease | Cerebrovascular disease | Other cardiovascular disease | Respiratory disease | Gastrointestinal disease | Other diseases | External causes | Risk difference for total mortality* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finland | 12.8 | 4.2 | 31.8 | 6.5 | 5.9 | 6.9 | 3.8 | 5.0 | 24.4 | 9.8 |

| Sweden | 5.9 | 6.0 | 30.1 | 3.5 | 5.3 | 6.7 | 5.6 | 15.0 | 21.2 | 5.6 |

| Norway | 11.7 | 9.3 | 34.7 | 2.9 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 14.9 | 13.4 | 5.2 |

| Denmark | 14.0 | 5.8 | 22.0 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 10.2 | 10.3 | 18.6 | 11.9 | 6.3 |

| England and Wales | 13.1 | 3.3 | 41.7 | 8.1 | 5.1 | 11.1 | † | 9.0 | 8.4 | 7.5 |

| Ireland | 18.7 | 8.3 | 25.4 | 7.4 | 5.7 | 14.7 | 0.8 | 8.1 | 11.0 | 8.1 |

| France | 8.6 | 29.2 | 2.7 | 3.9 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 16.7 | 14.7 | 12.4 | 11.5 |

| Switzerland | 22.8 | 19.1 | −0.3 | 4.2 | 7.4 | 9.1 | 10.7 | 13.7 | 16.0 | 5.0 |

| Italy | ‡ | 44.3 | § | § | 15.6 | 5.1 | 24.4 | 3.8 | 6.3 | 6.0 |

| Spain | 8.9 | 20.8 | −0.1 | 4.0 | 17.0 | 11.7 | 15.2 | 9.7 | 14.8 | 5.8 |

| Portugal | 1.3 | 8.9 | −11.3 | 13.0 | 2.6 | 15.0 | 19.8 | 16.3 | 33.1 | 6.1 |

Absolute difference between manual and non-manual classes in the probability (%) of dying between the ages 45 and 64

Combined with other diseases.

Combined with other cancers.

Combined with other cardiovascular diseases.

Discussion

Reliability and comparability of data

We have identified three major problems with the reliability and comparability of the available data on mortality by occupational class: inaccurate distinctions between manual and non-manual classes as defined in the EGP scheme; biases resulting from the exclusion of economically inactive men; and biases inherent in “unlinked” cross sectional studies.8,9 If these data problems are different for different causes of death, they will bias the contribution of causes of death to inequalities in all cause mortality. In a series of evaluations, we quantified the potential effect that these data problems could have on manual versus non-manual rate ratios.8,9 The potential size of error was less than 20% in all countries except Ireland, Spain, and Portugal. The magnitude of error did not vary substantially by cause of death. These errors might explain some of our results, notably those for Ireland, Spain, and Portugal, but cannot account for the large variations between countries seen for several causes of death.

Potentially the largest problem relates to the exclusion of economically inactive men from the datasets of most countries. Their exclusion causes an underestimation of mortality differences by occupational class, and this underestimation is larger for chronic diseases such as respiratory diseases.8 However, we have corrected for the exclusion of inactive men by using correction factors that could be calculated for each cause of death separately.8 It is highly unlikely that any remaining bias can explain the marked variations in the patterns that we found.

The comparability of registrations of the cause of death is another area of concern. Even though there are differences between European countries in the registration of causes of death, this is not necessarily a problem in this study. Registration problems could bias the results only if the degree of misclassification varied by occupational class and, in addition, if this possible association between misclassification and occupational class varied between countries. Perhaps most problematic are deaths registered as caused by ischaemic heart disease, a proportion of which may have been assigned to other disease categories. If misclassification occurs more commonly in deaths among lower occupational classes, the relative mortality of these classes might be underestimated. Can this problem explain the fact that mortality from ischaemic heart disease was not correlated to social class in southern countries? The data presented in table 3 allow estimation of the effect of adding other cardiovascular diseases (but not cerebrovascular disease) to ischaemic heart disease. This more robust group of causes of death also shows a clear north-south gradient.

Explaining variations between countries

Relatively large class differences in total mortality occurred in Finland and, especially, France. Data from a French study showed that the large differences in mortality from cancers other than lung cancer and gastrointestinal diseases in that country can be attributed to cancers of the upper digestive tract and to liver cirrhosis, respectively.11 These diseases have excessive alcohol consumption as a common risk factor. This finding implies that alcohol consumption should be included in explanations of the exceptionally large class differences in mortality in France.

In Finland, external causes of death make a relatively large contribution. This large contribution is also in part related to alcohol consumption. Alcohol related mortality has been estimated to account for at least 24% of the difference in life expectancy between manual classes and upper non-manual classes in Finland.12 Specific drinking patterns, with episodes of drunkenness interspersed with periods of abstinence, increase the incidence of violent deaths (including suicide, homicide, accidental falls, drowning, and alcohol poisoning) rather than deaths from chronic diseases.13

In southern European countries, death rates from ischaemic heart disease hardly differed between manual and non-manual classes. This is probably related to the low mortality from ischaemic heart disease in southern European countries.14 Specific factors have protected men from southern European countries against ischaemic heart disease: the traditional diet, with frequent consumption of fresh vegetables, fruits, fish, and vegetable oil, and the traditionally moderate levels of alcohol consumption.15 There is evidence that these factors have protected lower socioeconomic groups in particular.16,17

Smoking may have had an additional role. Marked inverse social gradients in smoking emerged in northern Europe in the 1960s or before, but in southern Europe these gradients emerged only during the 1980s.16–18 Inverse class gradients in smoking existed in Switzerland in the early 1980s but were weaker than in northern Europe.19

Despite the lack of clear social gradients in smoking in southern Europe in the early 1980s, class differences in deaths from lung cancer were about as large in France, Switzerland, and Spain as they were in northern countries (table 4). Other risk factors for lung cancer (psychosocial factors or high exposure to carcinogenic substances at work) seem to have increased deaths from lung cancer among male manual workers in southern countries.20

In the early 1980s European countries differed in the degree to which health care was accessible to lower occupational classes.21 Financial barriers were generally larger in France, Switzerland, and Spain than in more northern countries.21 If reduced access to health care affected the survival of lower socioeconomic groups, that effect would be clearest for causes of death that are amenable to medical intervention. An example is cerebrovascular disease, in which adequate detection and control of hypertension can lower mortality. However, class differences in mortality from cerebrovascular disease are not larger in France, Switzerland, or Spain than in countries with more equal access to healthcare services.

Implications of crossnational variations

Specific national circumstances seem to be able to strongly influence the magnitude, pattern, and causes of socioeconomic inequalities in health. The prevalence, at the national level, of risk factors that have the potential to strengthen the links between socioeconomic disadvantage and premature death seem to be particularly important. This was illustrated by the alcohol consumption patterns in France and Finland. Conversely, mortality differences in Mediterranean countries seem to have been mitigated by dietary habits and drinking patterns that traditionally protected men from lower classes against ischaemic heart disease.

The international variations observed here impose limits on the exchange of research findings from one country to another. This applies, for example, to studies assessing the extent to which inequalities in mortality can be attributed to risk factors for cardiovascular disease.22 The similarity that was observed among northern European countries supports the frequently made assumption that results of studies from one country apply to other northern countries, but they should not be extended to France, Switzerland, or Mediterranean countries. These countries need their own explanatory studies, which, lamentably, are rare.1,2

The same caution is needed with countries’ exchange of experiences with interventions that aim at improving the health of disadvantaged groups by reducing the prevalence of specific risk factors for disease. Our results for causes of death related to smoking suggest that a reduction in smoking rates may have much larger effects on health inequalities in England and Wales than in Sweden or France. The prevention of alcohol misuse by men in manual classes deserves a higher priority in France and Finland than elsewhere.

Persistence of the gap in premature death

Despite the large variations between countries in class differences in mortality from specific causes of death, differences in total mortality were similar in most western European countries. There is a parallel with trends over time in northern Europe. Large socioeconomic differences in total mortality existed when infectious diseases and other “old” diseases dominated mortality patterns. Later, when “diseases of affluence” and other degenerative diseases became the major causes of premature death, the mortality advantage of higher occupational classes persisted. Higher classes thus seemed to have changed their life styles and living conditions in ways that protected them against the new causes of death. This adjustment process was clearest for ischaemic heart disease.23,24

This paper shows that in southern countries higher occupational classes have also maintained a higher chance of reaching old age. They achieved this not so much by preventing death from ischaemic heart disease but by preventing premature death from diseases that were more important in their own country, such as alcohol related diseases.

The factors that allow the higher occupational classes to avoid premature death can obviously not be restricted to disease specific risk factors alone, but need to involve factors or mechanisms that determine the distribution of these risk factors over occupational classes. These “fundamental causes” 25 can be of various kinds.

Recent literature has emphasised the potential importance of psychosocial stress.26–29 Chronic stress is expected to increase the risk of premature death directly through the immune and neuroendocrine systems and indirectly through adverse behavioural responses such as smoking, excessive drinking, and violence.26–29 Cultural and behavioural responses to chronic stress may vary from country to country, as is suggested by variations between countries in national patterns of causes of death. Similarly, exposure to chronic stress in disadvantaged groups may increase their risk of different causes of death in different parts of Europe.

A complementary perspective emphasises the process of social achievement and access to resources.25,30–33 Members of higher occupational classes have access to a wide array of resources, including the resources that are needed to achieve a desired occupational position (such as higher education and a favourable socioeconomic background) and the resources that accrue to those who have attained a high position (high income, job security, and sense of control).33 This enables higher occupational classes to protect themselves against premature death in a flexible way. Different epidemiological situations need different strategies for survival into old age, with the upper occupational classes being in the best position to identify and pursue the optimal survival strategies.

Acknowledgments

Members of the EU Working Group on Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health who contributed to this paper are Otto Andersen, Danmarks Statistik, Copenhagen, Denmark; Jens-Kristian Borgan, Statistics Norway, Oslo, Norway; Giuseppe Costa, Environmental Protection Agency, Piedmont Region, Italy; Guy Desplanques, INSEE, Lyon, France; Fabrizio Faggiano, University of Torino, Turin, Italy; Seeromanie Harding, Haroulla Filakti, Office for National Statistics, London, United Kingdom; Maria do R Giraldes, National School of Public Health, Lisbon, Portugal; Christoph Junker, Christoph Minder, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland; Brian Nolan, Economic and Social Research Council, Dublin, Ireland; the late Floriano Pagnanelli, National Institute of Statistics, Rome, Italy; Enrique Regidor, Ministry of Health, Madrid, Spain; Denny Vågerö, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden;Pekka Martikainen, Tapani Valkonen, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

Editorial by Donnan

Footnotes

Funding: European Union Biomed-1 programme (grant No CT92-1068).

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Mielck A, Giraldes M do R, editors. Inequalities in health and health care: review of selected publications from 18 western European countries. M. ünster: Waxmann; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Illsley R, Svensson P-G, eds. Social inequalities in health [special issue]. Soc Sci Med 1990;31:223-40.

- 3.Valkonen T. Adult mortality and level of education: a comparison of six countries. In: Fox AJ, editor. Health inequalities in European countries. Aldershot: Gower; 1989. pp. 142–162. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leclerc A, Lert F, Fabien C. Differential mortality: some comparisons between England and Wales, Finland and France, based on inequalities measures. Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19:1001–1010. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.4.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vågerö D, Lundberg O. Health inequalities in Britain and Sweden. Lancet. 1989;ii:35–36. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunst AK, Mackenbach JP. The size of mortality differences associated with educational level in nine industrialized countries. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:932–937. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.6.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackenbach JP, Kunst AK, Cavelaars AEJM, Groenhof F, Geurts JJM EU Working Group on Socio-economic Inequalities in Health. Socio-economic inequalities in morbidity and mortality in Western Europe: a comparative study. Lancet. 1997;349:1655–1659. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07226-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunst AK, Cavelaars AEJM, Groenhof F, Geurts JJM, Mackenbach JP EU Working Group on Socio-economic Inequalities in Health. Socio-economic inequalities in morbidity and mortality in Europe: a comparative study. Rotterdam: Erasmus University; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunst AK, Groenhof F, Mackenbach JP and EU Working Group on Socio-economic Inequalities in Health. Occupational class and mortality among men 30 to 64 years in 11 European countries. Soc Sci Med (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Bartley M, Carpenter L, Dunnell K, Fitzpatrick R. Measuring inequalities in health: an analysis of mortality patterns using two social classifications. Sociology of Health and Illness. 1996;18:455–475. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desplanques G. La mortalité des adults: résultats de 2 etudes longitudinales (période 1955-1980). Paris: INSEE; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mäkelä P, Valkonen T, Martelin T. Contribution of deaths related to alcohol use to socio-economic variation in mortality: register-based follow up study. BMJ (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Poikolainen K. Risk of alcohol-related hospital admission in men as predicted by marital status and social class. J Stud Alcohol. 1983;44:986–995. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1983.44.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uemura K, Pisa Z. Trends in cardiovascular disease mortality in industrialized countries since 1950. World Health Statist Q. 1988;41:155–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kushi LH, Lenart EB, Willett WC. Health implications of Mediterranean diets in light of contemporary knowledge. 1. Plant foods and dairy products. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61(suppl):1407–1415. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.6.1407S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Comisión Científica de Estudios de las Desigualdades Sociales en Salud en España. Desigualdades sociales en salud en España. Madrid: Ministry of Health; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cavelaars AEJM, Kunst AK, Mackenbach JP. Socio-economic inequalities in risk factors of morbidity and mortality in the European Community: an international comparison. J Health Psychol. 1997;2:353–372. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasco AJ, Grizeau D, Pobel D, Chatard O, Danzon M. Tabagisme et classe social en France de 1974 à 1991. Bull Cancer. 1994;81:355–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.La Vecchia C, Gutzweiler F, Wietlisbach V. Sociocultural influences on smoking habits in Switzerland. Int J Epidemiol. 1987;16:624–626. doi: 10.1093/ije/16.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loon AJM van, Goldbohm RA, Brandt PA van den. Lung cancer: is there an association with socio-economic status in the Netherlands? J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49:65–69. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doorslaer E van, Wagstaff A, Rutten F. Equity in the finance and delivery of health care: an international perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan GA, Keil JE. Socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease: a review of the literature. Circulation. 1993;88:1973–1997. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vågerö D, Lundberg O. Socio-economic mortality differentials among adults in Sweden. In: Lopez AD, Casselli G, Valkonen T, editors. Adult mortality in developed countries: from description to explanation. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1995. pp. 223–242. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marmot MG, Adelstein AM, Robinson N, Rose GA. Changing social class distribution of heart disease. BMJ. 1978;ii:1109–1112. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6145.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Social Behaviour 1995;(Special No):80-94. [PubMed]

- 26.Wilkinson RG. Unhealthy societies: the afflictions of inequality. London: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans RG, Hodge M, Pless IB. If not genetics, then what? Biological pathways and population health. In: Evans RG, Barer ML, Marmor TR, editors. Why are some people healthy and others not? New York: Aldin de Gruytere; 1994. pp. 161–188. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunner E. The social and biological basis for cardiovascular disease. In: Blane D, Brunner E, Wilkinson R, editors. Health and social organisation. London: Routledge; 1996. pp. 272–299. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA. Socioeconomic status and health: the challenge of the gradient. Am Psychol. 1994;49:15–24. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carroll D, Davey Smith G. Bennett P. Some observations on health and socioeconomic status. J Health Psychol. 1996;1:23–39. doi: 10.1177/135910539600100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vågerö D, Illsley R. Explaining health inequalities: beyond Black and Barker. A discussion of some issues emerging in the decade following the Black Report. European Sociology Review. 1995;11:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charlton BG, White M. Living on the margin: a salutogenic model for socio-economic differentials in health. Public Health. 1995;109:235–243. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(95)80200-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kunst AK. Rotterdam: Erasmus University; 1997. Cross-national comparisons of socio-economic differences in mortality [dissertation] [Google Scholar]