Abstract

By targeting redox-sensitive amino acids in signaling proteins, the NADPH oxidase (Nox) family of enzymes link reactive oxygen species to physiological processes. We previously analyzed the sequences of 107 Nox enzymes and identified conserved regions that are predicted to have important functions in Nox structure or activation. One such region is the cytosolic B-loop, which in Nox1–4 contains a conserved polybasic region. Previous studies of Nox2 showed that certain basic residues in the B-loop are important for activity and translocation of p47phox/p67phox, suggesting this region participates in subunit assembly. However, conservation of this region in Nox4, which does not require p47phox/p67phox, suggested an additional role for the B-loop in Nox function. Here, we show by mutation of Nox4 B-loop residues that this region is important for Nox4 activity. Fluorescence polarization detected binding between Nox4 B-loop peptide and dehydrogenase domain (Kd = 58 ± 12 nm). This interaction was weakened with Nox4 R96E B-loop corresponding to a mutation that also markedly decreases the activity of holo-Nox4. Truncations of the dehydrogenase domain localize the B-loop-binding site to the N-terminal half of the NADPH-binding subdomain. Similarly, the Nox2 B-loop bound to the Nox2 dehydrogenase domain, and both the Nox2 and Nox4 interactions were dependent on the polybasic region of the B-loop. These data indicate that the B-loop is critical for Nox4 function; we propose that the B-loop, by binding to the dehydrogenase domain, provides the interface between the transmembrane and dehydrogenase domains of Nox enzymes.

Keywords: Electron Transfer, Flavoproteins, Oxidase, Protein Structure, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), NADPH Oxidase, Nox2, Nox4, Fluorescence Polarization, gp91phox

Introduction

The Nox family of NADPH oxidases catalyzes the reduction of molecular oxygen to form superoxide anion and secondary reactive oxygen species (ROS)2 that target redox-sensitive pathways controlling various physiological and pathophysiological processes (1–3). Most mammals express seven isoforms, Nox1, Nox2, Nox3, Nox4, Nox5, Duox1, and Duox2, and homologs of these enzymes are seen throughout the eukaryotic kingdom (4). These isozymes can be grouped based on their mode of regulation into the p22phox-dependent (Nox1–4) and calcium-dependent (Nox5, Duox1/2) Nox subfamilies. Nox5 and Duox1/2 contain EF-hand motifs that sense intracellular calcium concentrations to activate ROS production (5, 6). Nox1–4 form a stable complex with membrane-bound p22phox, and of these, Nox1–3 require additional regulatory subunits, whereas Nox4 is constitutively active (7–9). Nox1 and Nox2 assemble with an organizer subunit (p47phox for Nox2 and NOXO1 for Nox1), an activator subunit (p67phox for Nox2 and NOXA1 for Nox1), and the small GTPase, Rac in its GTP-bound state, to form an active enzyme complex (10–16). Human Nox3, on the other hand, requires only NOXO1 (8, 17).

The cellular events leading to Nox activation have been extensively characterized for the Nox2 system that predominates in phagocytes (reviewed in Refs. 18–20). In response to invading microbes, phagocytes initiate signaling cascades leading to the phosphorylation of p47phox and perhaps other subunits; this relieves its auto-inhibitory conformation and exposes binding domains for both p22phox and membrane lipids, allowing p47phox to translocate to the membrane. Both p67phox and p40phox are in a complex with p47phox, and these components also move to the membrane upon cell activation. Assembly of these components along with GTP-Rac in a complex with Nox2-p22phox results in activation of NADPH-dependent superoxide generation.

Nox4 is unique among the Nox enzymes in that it is constitutively active in the absence of nonmembrane-associated regulatory subunits or calcium-binding regulatory domains (7–9). This isoform is expressed in various cell types, including the kidney, vascular smooth muscle, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and adipocytes (21–25). The constitutive activity of Nox4 suggests that this enzyme exists in or is in equilibrium with an active conformation. Understanding the structural features of Nox4 may therefore provide insights into the active conformation of all of the Nox enzymes, which in other Nox enzymes is induced by regulatory domains or subunits.

The core catalytic unit of Nox enzymes is composed of a heme-binding transmembrane domain and a dehydrogenase (DH) domain that contains the binding sites for both FAD and NADPH (26). Theoretical approaches such as hydropathy plots and secondary structure prediction programs, as well as empirically derived data from epitope mapping, point to a structure in which the transmembrane domain consists of six membrane-spanning α-helices connected by five loops, termed loops A–E (27, 28). Loops A, C, and E face the extracellular or luminal space where oxygen reduction occurs, while loops B and D face the cytoplasm side of the membrane where the DH domain is also located. Histidine residues located in the third and fifth transmembrane helices coordinate two nonidentical hemes (29). Secondary structural prediction programs and significant homology to other flavoproteins indicate that the Nox DH domain consists of the following two subdomains: a β-barrel fold that binds FAD connected by a short linker region to an alternating β-strand/helix domain that binds NADPH (30, 31).

Previously, we carried out an extensive molecular evolution analysis of more than 100 Nox enzymes from a variety of species and identified conserved regions (in addition to the cofactor-binding sites) that were predicted to be important for Nox structure or activity (4). One such region was the cytosolic B-loop. In earlier studies of Nox2, this loop was proposed as a binding site for p47phox, as residues corresponding to a region of this loop from a phage display peptide library bound to recombinant p47phox (32). Furthermore, both mutagenesis of arginine residues in the Nox2 B-loop and peptides corresponding to the Nox2 B-loop inhibited Nox2 activity and prevented p47phox/p67phox translocation to the membrane (32–34).

However, the Nox2 B-loop shares considerable homology with that of Nox4 (see below), suggesting a more general role for this loop in Nox function. This study was undertaken to evaluate the importance of the B-loop in Nox4. We find that Nox B-loops containing a polybasic sequence bind to the DH domains of both Nox4 and Nox2, and data support a model in which this binding mediates the functionally important interaction between the FAD/NADPH-binding DH domain and the heme-containing transmembrane domain of Nox enzymes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

B-loop Sequence Alignment

Nox family B-loop and surrounding sequences were aligned using ClustalW2 available on line from European Bioinformatics Institute (35). Alignments were created using the following: human Nox1 (GenBankTM accession number NM_007052); rat Nox1 (GenBankTM accession number NM_053683); chicken Nox1 (DDBJTM accession number BR000265); dog Nox1 (GenBankTM accession number XM_549136); mouse Nox1 (GenBankTM accession number NM_172203); human Nox2 (GenBankTM accession number NM_000397); mouse Nox2 (GenBankTM accession number NM_007807); rat Nox2 (GenBankTM accession number NM_023965); dog Nox2 (DDBJTM accession number BR000269); chicken Nox2 (DDBJTM accession number BR000270); human Nox3 (GenBankTM accession number NM_015718); mouse Nox3 (GenBankTM accession number AY573240); dog Nox3 (DDBJTM accession number BR000273); chicken Nox3 (GenBankTM accession number XM_426166.1); rat Nox3 (GenBankTM accession number NM_001004216); human Nox4 (GenBankTM accession number. NM_016931.2); mouse Nox4 (GenBankTM accession number NM_015760); rat Nox4 (GenBankTM accession number NM_015760); dog Nox4 (GenBankTM accession number XM_542262.2); frog Nox4 (Ensembl number ENSXETP00000025676); chicken Nox4 (DDBJTM accession number BR000274); human Nox5 (GenBankTM accession number AF353088); dog Nox5 (DDBJTM accession number BR000277); cow Nox5 (DDBJTM accession number BR000276); opossum Nox5 (DDBJTM accession number BR000304); chicken Nox5 (DDBJTM accession number BR000278); frog Nox5 (Ensembl number ENSXETP00000017078); human Duox1(GenBankTM accession number NM_017434); and Duox2 (GenBankTM accession number NM_014080).

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Nox4 point mutations Arg-84 mutated to Ala (denoted R84A) and other mutations (R92A, R93A, R95A, R95E, R96A, and R96E) were generated using site-directed mutagenesis with human Nox4 cDNA with a silent mutation deleting the internal BamHI site. Amplification used a sense Nox4 full-length primer with an N-terminal BamHI site (primer 1, 5′-ttttGGATCCGCCACCATGGCTGTGTCCTGGAGGAGCTGGCTCGCCAACGA-3′) and antisense Nox4 primer with a C-terminal NotI site (primer 2, 5′-ttttGCGGCCGCCTAGCTGAAAGACTCTTTATTGTATTC-3′). Two internal primers were also generated for each point mutation (primer 3, 5′-AGCAGGAGAACCGAGAGATTGTTGGAT-3′, and primer 4, 5′-ATCCAACAATCTCTCGGTTCTCCTGCT-3′) with the R95E-substituted codon underlined. PCRs amplified Nox4 cDNA using primers 1 and 3 and primers 2 and 4, and the products of these two reactions were amplified by primers 1 and 2 to create full-length cDNA containing the appropriate point mutation. PCR products were digested and inserted in the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3 (Invitrogen), and correct sequences were verified by commercial DNA sequencing (Agincourt Bioscience Corp.). A similar strategy was used to create all Nox4 amino acid substitutions. Nox4 C-terminal Myc-tagged constructs were created for immunoprecipitation and Western blots using sense Primer 1 and antisense primer 5 (5′-ttttGTCGACGCTGAAAGACTCTTTATTGTATTCAAATCTTGTCCC-3′), which does not include a stop codon and includes a C-terminal SalI site for insertion into pCMV-Tag 5a vector (Stratagene).

ROS Measurement

HEK 293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) (+4.6 g/liter glucose + l-glutamine) + 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals) supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cells for ROS measurements were plated in 6-well plates, grown for 24 h, and transfected with WT or mutant human Nox4 cDNA in pcDNA3 or empty pcDNA3 using FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science) transfection system according to the manufacturer's instructions. After ∼48 h, cells were harvested in Hanks' balanced salt solution (Invitrogen), and ROS was measured using luminol chemiluminescence with 20 μm luminol and 0.32 unit of horseradish peroxidase in a 200-μl total volume with FluoStarTM luminometer (BMG Labtech). The mean of three separate wells is reported with standard deviation. A minimum of three separate transfection experiments was repeated for each condition.

Co-immunoprecipitation and Western Blot

Nox4-myc-tagged constructs and p22phox cDNA were transfected into HEK 293 cells grown for 24 h in 10-cm culture dishes using the FuGENE 6 transfection system. Cells were harvested in Hanks' balanced salt solution and lysed in 20 mm Tris-HCl, 1% Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl containing protease inhibitor mixture and EDTA (Complete mini, Roche Applied Science), 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 100 μm diisopropyl fluorophosphate, the latter included to improve access of the protease inhibitor to membrane compartments. Lysates were centrifuged, and the protein-containing supernatant fractions were incubated with anti-Myc monoclonal antibodies (Cell Signaling) overnight. Immunoreactive proteins were precipitated with protein G-Sepharose 4B beads (Sigma) and washed 10 times with Tris buffer before addition of Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad) containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot using the previous anti-Myc antibody and anti-p22phox monoclonal antibody 44.1 (a generous gift from M. Quinn and purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and protein was visualized with secondary anti-mouse-conjugated horseradish peroxidase antibodies detected with enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce).

Recombinant Protein Purification

To express and purify recombinant Nox4 and Nox2 dehydrogenase domain proteins, constructs were created starting from the end of the last predicted transmembrane helix to the C terminus consisting of residues Nox4-(304–578) (GenBankTM accession number NM_016931.2) and Nox2-(290–570) (GenBankTM accession number NM_000397) for full-length dehydrogenase domains. Nox4 dehydrogenase domain truncations consisted of the following amino acid sequences: the predicted FAD-binding domain and small hinge, residues 304–420; the hinge region and NADPH-binding domain, residues 411–578; the N-terminal half of the NADPH-binding domain, residues 420–488; and the C-terminal half of the NADPH-binding domain, residues 489–578. The following primers were used to amplify human Nox2 or human Nox4 cDNA; Nox2 sense with BamHI site underlined beginning with residue 290 (5′-TTTTGGATCCCGATCTCAACAGAAGGTGTCATCA-3) and Nox2 antisense with SalI site underlined (5′-TTTTGTCGACTTAGAAGTTTTCCTTGTTGAAAATGAAATGCAC-3′); Nox4 sense beginning with residue 304 (5′-TTTTGGATCCCGGAGCAATAAGCCAGTCACCATCA-3′) and antisense primer ending with residue 578 (5′-TTTTGTCGACCTAGCTGAAAGACTCTTTATTGTATTC-3′); antisense primer ending with residue 420 and added stop codon (5′-TTTTGTCGACTCATGATTCCTCAAATGGACTTC-3′); sense primer with BamHI site beginning with residue 411 (5′-TTTTGGATCCGGTCCTTTTGGAAGTCCATTTGAG-3′); sense primer with BamHI site beginning with residue 420 (5′-TTTTGGATCCTCACTGAACTATGAGGTCAGCCTC-3′) and antisense primer ending with residue 488 and SalI site (5′-TTTTGTCGACTTATCTGTTCTCTTGCCAAAACTTGTTATGC-3′); sense primer beginning with residue 489 with BamHI site (5′-TTTTGGATCCCCTGACTATGTCAACATCCAG-3′). All PCR products were digested with BamHI and SalI and ligated into pGEX 4T3 (GE Healthcare) to generate glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins. Proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 DE3 pLys and cultured at 37 °C until reaching an A600 ∼0.6–0.8. After addition of 200 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, bacteria were induced for 6 h at 25 °C. Cells were lysed in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 10 μm FAD, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 100 μm diisopropyl fluorophosphate, 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20, 1 mm 1,4-dithiothreitol, with Complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). Lysate was sonicated and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 1 h followed by incubation of the supernatant fraction with glutathione-SepharoseTM 4B (GE Healthcare). Following several washes, GST-fused proteins were eluted with reduced glutathione (Sigma) and dialyzed against 10 mm Hepes, 10 mm NaCl, 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20, 1 μm FAD, pH 7.5. All purified proteins were resolved on 12% gel by SDS-PAGE and visualized with Coomassie Blue staining.

Fluorescence Polarization

All proteins were freshly used following dialysis for fluorescence polarization assays. Ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase was obtained from Sigma. All Nox B-loop peptides were synthesized and purified by high pressure liquid chromatography to >98% purity by the Emory University Microchemical Facility, and the correct mass was verified by mass spectroscopy. The following B-loop peptides were used for binding measurements: N-terminally conjugated fluorescein (FITC) Nox4 WT B-loop, FITC-RTLLAYLRGSQKVPSRRTRRLLDKSRTFHI-amide; Nox4 R96E B-loop, FITC-RTLLAYLRGSQKVPSRRTRELLDKSRTFHI-amide; Nox2 WT B-loop, FITC-RNLLSFLRGSSACCSTRVRRQLDRNLTFHK-amide; Nox2 R91E/R92E B-loop, FITC-RNLLSFLRGSSACCSTRVEEQLDRNLTFHK-amide; and Nox5 B-loop, FITC-RRCLTWLRATWLAQVLPLDQNIQFHQ-amide. Nox4 (or Nox2) DH domain proteins in 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 0.05% Tween 20, 1 μm FAD, and NaCl concentration (specified in each figure legend) were titrated into a microplate, and a constant 31 nm fluorescence B-loop peptide (diluted in the same buffer) was added to each well. Fluorescence polarization was measured immediately after adding protein and peptides to the plate at 25 °C in with SynergyTM2 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader and Gen5TM software package (BioTek). The principle behind the method is as follows. The method uses plane polarized light to excite a fluorophore and polarizing filters to monitor the difference in emitted polarized fluorescent light intensity in the parallel versus perpendicular channels. A rapid tumbling small fluorophore (i.e. the peptide) emits depolarized light, because fluorescence emission occurs on a slower time scale than the rotational relaxation time of the molecule, and when the fluorophore is bound to a macromolecule, the rotation of the fluorophore is slowed and light remains polarized. Thus, binding results in an increase in the polarized light channel. FAD at 1 μm did not affect the polarization readings. For the Nox4 DH domain, Nox4 B-loop interaction is stable for >1.5 h. The fluorescence measurements were made with excitation filter 485 nm with bandwidth 20 and emission filter 528 nm with bandwidth 20. Binding curves were generated by a nonlinear least squares fit of the data to a four-parameter binding equation (sigmoidal dose-response curves, variable slope) using GraphPad Prism. The equation models fluorescence polarization versus Nox DH domain protein concentration using four parameters as follows: maximum and minimum polarization values, EC50 values, and slope of the curve. The goodness of the fit for each curve was evaluated by the R2 value. For weakly binding peptides, it was sometimes not possible to achieve saturating levels of binding. Therefore, to estimate binding constants in such cases, the maximum polarization value was constrained to that obtained from Nox4 WT B-loop peptide measurements.

Nox4 B-loop peptides lacking the FITC group were used in some experiments to compete bound FITC-labeled B-loop peptides from the dehydrogenase domains, monitoring competition by fluorescence polarization. Nox4 WT and R96E peptide sequences identical to those listed above were also synthesized without the FITC label by the Emory University Microchemical Facility and were purified and characterized as described above. Nox4 WT short peptide, NH3+-RRTRRLLDKSRT-COO−, was a generous gift from Dr. H. Ogawa (Fujita Health University). Unlabeled peptides of various concentrations were incubated with 60 nm GST-Nox4 DH protein with ∼31 nm FITC-Nox4 WT or R96E full-length B-loop peptides. Data were fit to a one-site competition model to obtain IC50 values and 95% confidence intervals. An unpaired, two-tail t test was used to determine p values for statistical significance.

Cytochrome c Reduction

Recombinant GST-Nox4 dehydrogenase domain protein or GST (100 nm each) was incubated with 300 μm FAD (Sigma), 80 μm cytochrome c (from horse heart, Sigma), and either 20 μm diphenyleneiodonium or 0.2% DMSO in assay buffer containing 120 mm NaCl, 3 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm Hepes, and 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.0. The reaction components were added to a microplate, and the reaction was immediately initiated with 250 μm NADPH (Sigma), and cytochrome c absorbance at 550 nm was measured using SynergyTM2 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader at 37 °C. This concentration of FAD was sufficient to nearly saturate the Nox4 DH domain resulting in ∼80% of Vmax. Most of the cytochrome c reduction was confirmed to be unaffected by 100 units/ml superoxide dismutase (Sigma). The calculation of turnover number uses extinction coefficient of cytochrome c, 21.1 mm−1 cm−1 at 550 nm. The reported turnover number is the average of three independent experiments.

RESULTS

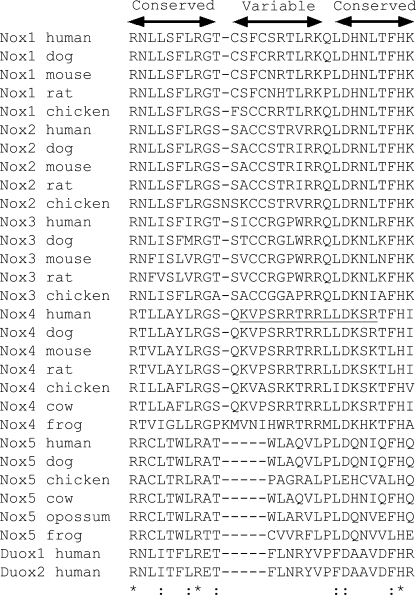

Conservation of the B-loop Region in Vertebrate Nox Enzymes

The boundaries between the transmembrane α-helices and B-loop were estimated using web servers that predict secondary structure. These boundaries are predicted to reside in or near the N- and C-terminal conserved regions labeled in Fig. 1, although exact boundaries cannot be determined with certainty in the absence of a structure (35–37). For the purposes of this paper, we define the B-loop as residues 77–106 (human Nox4 sequence) according to our previously published Nox sequence alignment (4). This includes several additional residues at the C terminus, including histidine 105, one of the heme-iron-ligating histidine residues as a reference. Analysis of multiple sequence alignments of vertebrate Nox B-loops and surrounding regions revealed three distinct subregions of Nox B-loops as follows: 1) a conserved N-terminal region; 2) a variable central region; and 3) a conserved C-terminal region (Fig. 1) (35). The two flanking conserved regions are shared by all Nox isoforms, whereas the central variable region is characteristic of specific Nox isoforms or regulatory classes. In the case of Nox enzymes that require p22phox (but not calcium-regulated Noxes), the variable region contains a polybasic region (PBR) (underlined in human Nox4 sequence Fig. 1). Some of these basic residues in Nox2 have been previously shown by mutagenesis to be necessary for activity (4, 34).

FIGURE 1.

Amino acid sequence alignment of Nox/Duox B-loops. Primary sequences of various Nox/Duox proteins were aligned using ClustalW2. Symbols below the alignment reflect level of conservation as follows: *, identical, :, similar. The polybasic region of the human Nox4 sequence is underlined.

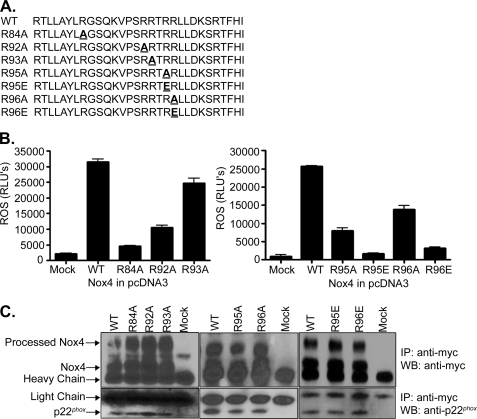

Amino Acids in the Nox4 B-loop Are Important for Nox4 Activity

To determine the importance of the B-loop in Nox4 enzymatic activity, point substitutions of arginine residues were generated by site-directed mutagenesis (indicated in Fig. 2A). Mutant Nox4 was expressed in HEK 293 cells, and ROS-generating activity was monitored (Fig. 2B). Individual mutation of Arg-84, Arg-92, Arg-95, and Arg-96 to alanine all caused a decrease in Nox4 activity, ranging from 50 to <5% of wild-type (WT) activity, whereas the R93A mutation retained ∼80% of WT activity. Individual substitution of Arg-95 and Arg-96 to glutamic acid resulted in nearly complete loss of ROS production (Fig. 2B, right panel).

FIGURE 2.

Arginine residues located in the Nox4 B-loop are important for Nox4 activity. A, Nox4 B-loop sequences are shown with the corresponding arginine mutation underlined. B, Nox4 wild type (WT), the indicated arginine mutations, or empty vector (mock) were expressed in HEK 293 cells, and ROS production was measured by luminol chemiluminescence. Values reported are relative light units (RLU), mean ± S.E. (n = 3). C, Nox4 expression in HEK 293 cells was determined by transfection of C-terminal Myc-tagged Nox4 WT, mutant, or empty vector (mock) followed by immunoprecipitation (IP) using anti-Myc antibodies. Protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting (WB) was carried out using anti-Myc and anti-p22phox antibody as indicated.

The expression of Nox4 WT and mutant proteins was examined by expressing mutated, Myc-tagged Nox4 in HEK 293 cells, followed by immunoprecipitation and Western blotting (Fig. 2C). Similar levels of expression were detected for all Nox4 mutants compared with WT. Wild-type and mutant forms of Nox4 all displayed a band at ∼65 kDa, the predicted molecular mass of unprocessed Nox4 as well as a higher molecular mass band (∼80 kDa), which may represent a glycosylated form of Nox4. A similar higher molecular mass Nox4 band has previously been reported in HeLa cells (38), A549 cells (39), vascular smooth muscle cells (40), and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (41). Nox4 heterodimerizes with p22phox, and this binding is required for activity (8). WT and all mutant forms of Nox4 co-immunoprecipitated p22phox (Fig. 2C). Therefore, the decrease in activity displayed by the Nox4 mutants is not due to altered protein expression, processing, or complex formation with p22phox.

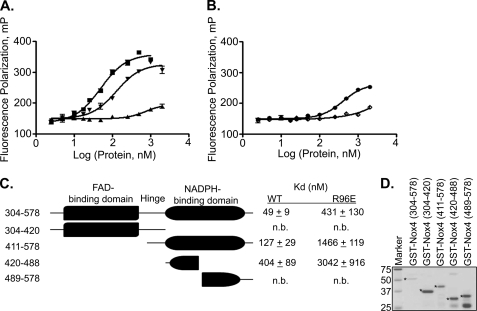

Nox4 B-loop Binds to Recombinant Nox4 DH Domain

The importance of individual B-loop amino acids for Nox4 activity suggested a functional role for this region. Because Nox4 does not require regulatory subunits, other than p22phox (and mutagenesis of the Nox4 B-loop does not affect p22phox-Nox4 interaction, Fig. 2C), we hypothesized that the B-loop binds directly to the DH domain, as both of these regions reside in the cytoplasm. To test this hypothesis, fluorescence polarization was employed; this method provides a sensitive and quantitative approach to investigate protein/peptide interactions (42). Nox4 B-loop peptides conjugated to fluorescein (FITC) at their N termini were titrated with GST-tagged recombinant Nox4 dehydrogenase domain (GST-Nox4 DH), and fluorescence polarization was monitored. GST-Nox4 DH caused a saturable increase in the fluorescence polarization of Nox4 B-loop peptide (Fig. 3A). The polarization change was fit to a binding curve that showed a Kd of 58 ± 12 nm. Nox4 B-loop peptides with the R96E mutation (a mutation that inhibited Nox4 activity, Fig. 2B) showed 10–20-fold decreased affinity (e.g. see Fig. 3A). The expressed GST domain alone failed to bind either B-loop peptide (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Nox4 DH domain binds to Nox4 B-loop peptides. A, binding between expressed, purified recombinant proteins and FITC-conjugated Nox4 WT or R96E B-loop peptides was detected by fluorescence polarization (mP). Data were fit to sigmoidal dose-response curves using GraphPad Prism to obtain the indicated binding constants (95% confidence intervals shown). ■, GST-Nox4 DH + WT B-loop, Kd = 58 ± 12 nm; ●, GST-Nox4 DH + R96E B-loop, Kd = 1341 ± 155 nm; □, GST alone + WT B-loop; ○, GST alone + R96E B-loop. B, ferredoxin NADP+ reductase was incubated with Nox4 WT (▾) and R96E (●) B-loop. C, GST-Nox4 and WT Nox4 B-loop peptides were incubated in buffer containing 10 (■), 75 (▴), 150 (▾), and 500 (♦) mm NaCl. Binding was monitored by fluorescence polarization and converted to percent bound. D, unlabeled WT, R96E, or PBR B-loop peptides were added to GST-Nox4 DH protein (60 nm) plus FITC-conjugated Nox4 WT B-loop. Data were fit to one-site competition curves using GraphPad Prism to obtain IC50 values. Reported are the mean IC50 values of three independent experiments with means ± S.E. ■, holo-B-loop (amino acids 77–106), IC50 = 0.38 ± 0.08 μm; ▴, R96E B-loop (amino acids 77–106), IC50 = 8.7 ± 1.3 μm; □, PBR B-loop (amino acids 92–103), IC50 = 12.5 ± 4 μm. The difference between IC50 values for unlabeled WT B-loop versus unlabeled R96E B-loop showed p < 0.0006; WT B-loop versus PBR B-loop, p < 0.01; no statistically significant difference was seen between binding of unlabeled R96E and unlabeled PBR B-loop. E, cytochrome c reduction activity of GST-Nox4 DH (100 nm) (■, ●) or GST (100 nm) (□, ○) was monitored by the absorbance increase at 550 nm in the presence of 0.2% DMSO squares or 20 μm diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) circles in 0.2% DMSO. F, recombinant GST-Nox4 and GST were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. GST-Nox4 DH (∼5 μg) migrates at ∼50 kDa (shown with asterisk) and GST (∼11 μg) at 25 kDa; molecular weight markers are shown in the 1st lane.

The Nox dehydrogenase domains are structurally related to other NADPH-flavoprotein dehydrogenases such as ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase (26, 31). As a specificity control, ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase was evaluated in the fluorescence polarization assay, and no binding of the Nox4 B-loop to this flavoprotein could be detected (Fig. 3B).

Because of the charged nature of the B-loop and the importance of basic residue Arg-96 in B-loop binding, the salt dependence of this interaction was investigated (Fig. 3C). Increasing sodium chloride weakened the binding, consistent with a role for electrostatic forces in either direct binding or in stabilizing a binding conformation of the B-loop. In the presence of 10 mm NaCl, the binding constant was estimated to be less than 20 nm (this should be considered an upper limit, because accurate calculation of the very low Kd value was not possible due to significant ligand depletion under this condition). No binding was detected in high salt (500 mm NaCl), whereas at 75 and 150 mm NaCl, respective Kd values of 58 ± 12 and 245 ± 71 nm were determined.

The ability of WT Nox4 and R96E B-loop peptides (not fluorescently labeled) to compete with the FITC-conjugated WT B-loop peptide for binding to the DH domain was evaluated at the 75 mm salt concentration. WT B-loop competes with FITC-WT B-loop for GST-Nox4 DH domain with an IC50 of 0.38 ± 0.08 μm, whereas the R96E B-loop competes much less effectively, IC50 = 8.7 ± 1.3 μm (Fig. 3D). A shorter peptide consisting of just the PBR of Nox4 B-loop (residues 92–103, see Fig. 1) is a weaker competitor (IC50 = 12.5 ± 4 μm) compared with full-length B-loop peptide (residues 77–106). Therefore, although mutational data indicate the importance of the PBR for binding (Fig. 3A), high affinity binding requires additional B-loop residues outside of this region.

The Nox4 DH domain catalyzes a relatively robust NADPH- and FAD-dependent direct reduction of cytochrome c, which, unlike cytochrome c reduction by holo-Nox enzymes, is mostly independent of superoxide because it is not inhibited by superoxide dismutase.3 Because this reaction requires an approximately native folding of the DH domain (i.e. FAD- and NADPH-binding sites must remain functional), it can be used to assess whether or not the expressed DH domain retains a folded structure capable of catalysis. Our purified preparations of GST-Nox4 DH (see Fig. 3F) reduced cytochrome c in the presence of FAD and NADPH (turnover numbers averaged ∼100 min−1 in three experiments) (Fig. 3E), and this reduction was abrogated with the addition of the flavoprotein inhibitor diphenyleneiodonium. These data suggest that the expressed DH domain is close to its native conformation. Purified GST displayed only a low background level of cytochrome c reduction that was not decreased by diphenyleneiodonium.

Truncations of the Nox4 DH Domain Identify a B-loop-binding Subdomain

To determine the region of the Nox4 DH domain responsible for B-loop binding, truncated GST-Nox4 proteins were purified and tested for binding to the Nox4 B-loop peptides (Fig. 4, A and B). Full-length DH domain (amino acids 304–578) contains both the FAD- and NADPH-binding subdomains joined by a short connecting sequence termed the hinge region. As shown in Fig. 4C, the full-length Nox4 DH domain (amino acids 304–578) binds the Nox4 B-loop with the highest affinity (Kd = 49 ± 9 nm in this experiment). The expressed NADPH-binding domain (amino acids 411–578) still binds relatively tightly (Kd = 127 ± 29 nm), whereas the FAD- binding domain of Nox4 (amino acids 304–420) showed little or no binding. Approximately nine amino acids comprise the hinge region (amino acids 411–420), a stretch of residues connecting the C terminus of the FAD-binding domain to the N terminus of the NADPH-binding domain. This region was included in the truncated proteins to enhance recombinant protein expression and solubility.4 A less soluble form of the NADPH-binding domain without the hinge region (amino acids 420–578) also bound the Nox4 B-loop (data not shown) with similar affinity as the NADPH-binding domain truncation protein with the hinge (amino acids 411–578). Therefore, the hinge region does not contribute significantly to B-loop binding. To further delineate the B-loop binding region, the NADPH-binding subdomain was further truncated into N-terminal (amino acids 420–488) and C-terminal (amino acids 489–578) halves. The former still showed binding to the B-loop (Kd = 404 ± 89 nm), whereas no binding to the latter was seen. Therefore, the portion of the NADPH-binding subdomain that contributes most to binding the B-loop is contained within the 420–488-amino acid region. Both the NADPH-binding domain and N-terminal half of the NADPH-binding domain bound the R96E peptide with 10–20-fold less affinity than the WT B-loop peptide, similar to the effect of this substitution on binding to the full-length DH domain (amino acids 304–578).

FIGURE 4.

Nox4 B-loop preferentially binds to the NADPH-binding domain. Fluorescence polarization (mP) was monitored as in Fig. 3. A, Nox4 B-loop peptides in 75 mm NaCl were titrated with the following: ■, GST-Nox4 DH (amino acids 304–578); ▴, GST-Nox4 (amino acids 304–420); or ▾, GST-Nox4 (amino acids 411–578). B, binding between the Nox4 B-loop and NADPH-binding domain truncations: ●, GST-Nox4 (amino acids 420–488); GST-Nox4 (amino acids 489–578). C, schematic of GST-tagged DH domain truncations showing residues comprising the FAD-binding domain, short connecting region (hinge), and NADPH-binding domain. Binding constants with 95% confidence intervals are summarized adjacent to the corresponding truncated protein. n.b. means no binding. D, GST-Nox4 DH and truncation proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue for visualization. Molecular weight markers are shown in 1st lane, followed by ∼1 μg of Nox4-(304–578), 2 μg of Nox4-(304–420), 4 μg of Nox4-(411–578), 4 μg of Nox4-(420–488), and 16 μg of Nox4-(489–578). All proteins migrated at the expected molecular weights are denoted by asterisk.

To further identify the B-loop-binding site, we made 13 individual point mutations of candidate-binding site residues within the NADPH-binding domain. Several of these resulted in decreased binding and also affected activity of the expressed holo-Nox4. However, all of the mutations that affected binding also decreased the expression of the Nox4 DH domain, suggesting that these mutations affected protein folding and/or enhanced degradation and were therefore unsuitable for further analysis.

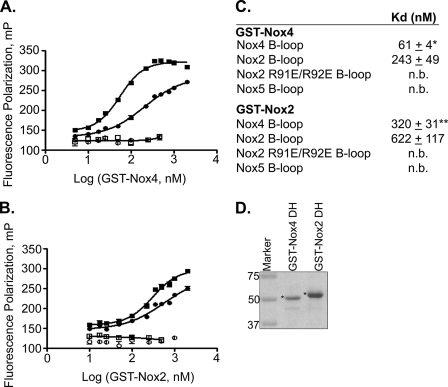

Isoform Specificity of Nox DH Domain/B-loop Interaction

The Nox2 and Nox4 B-loops show a relatively high conservation, including the PBR, whereas the Nox5 B-loop is distinct (Fig. 1). Therefore, FITC-labeled B-loop peptides from Nox2, Nox4, and Nox5 were compared with respect to binding both Nox2 and Nox4 DH domains. It was not possible to prepare the GST-Nox5 DH domain due to poor expression and solubility problems. GST-Nox2 DH bound to the B-loop peptides from both Nox4 and Nox2 with similar affinity (i.e. no statistical significant difference), Kd = 320 ± 31 nm and Kd = 622 ± 117 nm, respectively (Fig. 5, B and C). GST-Nox4 DH also bound to B-loop peptides from Nox2 (Kd = 243 ± 49 nm) and Nox4 (Kd = 61 ± 4 nm). Therefore, in contrast to the Nox2 DH domain, which showed no significant preference for B-loop from Nox2 versus Nox4, Nox4 prefers its cognate B-loop by a factor of ∼4. Also of note, the Nox4 DH domain binds its own B-loop as well as the Nox2 B-loop considerably more tightly than does the Nox2 DH domain. In contrast, neither DH domain bound to either the Nox5 B-loop (which lacks the PBR) or to the Nox2 B-loop containing the double mutation corresponding to R91E/R92E (mutations that nearly abolish Nox2 activity (34)). Therefore, basic residues at these positions in the Nox2 and Nox4 B-loop peptides are necessary for high affinity binding to their DH domains.

FIGURE 5.

Isoform specificity of DH domain/B-loop interaction. A, GST-Nox4 DH. B, GST-Nox2 DH domains were titrated with FITC-conjugated B-loops corresponding to WT Nox4 (■), WT Nox2 (●), Nox2 R91E/R92E (○), and WT Nox5 B-loop □, and fluorescence polarization (mP) was monitored as in Fig. 3. C, data were fit as in Fig. 3 using GraphPad Prism to obtain binding constants. The mean Kd value of three independent experiments is reported with standard error. n.b. means no binding. * indicates a p value < 0.02 comparing the Kd values for GST-Nox4 DH binding to Nox4 B-loop versus Nox2 B-loop. ** indicates no statistical difference between Kd values for GST-Nox2 DH binding to Nox4 B-loop versus Nox2 B-loop. D, recombinant proteins GST-Nox4 DH (∼7 μg) and GST-Nox2 DH (∼6 μg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie Blue stain. Molecular weight markers were loaded in the 1st lane. Both proteins migrated at the expected molecular weights, shown with asterisk.

DISCUSSION

Interactions involving regulatory subunits/domains and/or post-translational modifications of Nox enzymes activate ROS production in the Nox catalytic core (43). Ultimately, this must involve activating one or more steps in the electron transfer from NADPH through the electron carrying groups (FAD and heme) to molecular oxygen. For Nox2, both the reduction of FAD by NADPH and the electron transfer from FAD to heme A have been proposed as steps that are activated by regulatory subunits (44, 45). However, a molecular understanding of how these systems create an active conformation of Nox enzymes remains elusive. Unlike the other mammalian Nox enzymes, exogenously expressed Nox4 is constitutively active; hence, it provides a likely model for the active conformation of other Nox isoforms. In addition, because it does not require activating subunits (other than p22phox), Nox4 provides a more straightforward system in which to understand intramolecular interactions that are important for activity. Investigation of Nox4 structure and function may therefore provide a foundation for understanding functionally important regions of Nox enzymes. However, very little is known about regions in Nox4 (other than the cofactor-binding sites) that govern its activity.

In this study, we used mutagenesis to identify the B-loop as an important region for Nox4 activity. Mutation of Arg-84, Arg-92, Arg-95, and Arg-96 to alanines or glutamic acids (for Arg-95 and Arg-96) all resulted in a marked decrease in Nox4-dependent ROS-generating activity, without significantly altering Nox4 protein expression or binding to p22phox (Fig. 2), suggesting that although the B-loop PBR is a feature of p22phox-dependent Nox isoforms (Nox1–4), this region may not be involved in direct p22phox binding. In a previous study (4), the Nox2 R80E mutation resulted in decreased activity, impaired Nox2 maturation to its glycosylated form, and disrupted complex formation with p22phox. However, Nox4 mutated in the homologous residue (R84A) showed normal expression and p22phox binding but decreased activity, indicating that this position is also important for Nox4 activity (Fig. 1). Dinauer and co-workers (34) mutated residues within the Nox2 B-loop, including Arg-89, Arg-91, and Arg-92, which are homologous to Nox4 Arg-93, Arg-95, and Arg-96, respectively. For Nox2, single mutations to a neutral residue such as R89A had only a minor effect on activity, as with the effect of the homologous Nox4 R93A mutation in the present studies (Fig. 2B, left panel). For Nox2, only the double mutation of Arg-91 and Arg-92 significantly decreased Nox2 activity, whereas for Nox4, single mutations of either of the two homologous positions, Arg-95 or Arg-96, whether to alanine or glutamic acid, markedly decreased Nox4 activity (Fig. 2). Therefore, Nox4 appears to be more sensitive than Nox2 to mutations in these positions. In addition to the arginine mutations, a Nox4 T94E mutant protein inhibited Nox4 activity by ∼50% (data not shown) indicating that residues in the B-loop other than arginines are also important for activity.

The location and structure of the B-loop provide clues as to its possible function. The B-loop connects the second and third transmembrane α-helices in all Nox family members (4). Located within the third helix are two histidine residues that, together with histidines located in the fifth transmembrane helix, coordinate the irons of the two heme moieties (43). The two hemes (referred to as heme A and heme B) are located roughly at the levels of the two leaflets of the membrane bilayer and together form a transmembrane conduit allowing electrons from FAD on one side of the membrane to reduce molecular oxygen on the other (29). Both the B-loop and the cytoplasm-facing ends of transmembrane helices two and three contain charged and polar amino acids and are therefore likely to localize outside of the hydrophobic core of the membrane, toward the cytoplasm where the DH domain is also located. Therefore, we hypothesized that the B-loop provides an interface between the DH and transmembrane domains. In support of this model, this study demonstrates conclusively that the Nox4 B-loop binds directly to the Nox4 DH domain in vitro (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the same B-loop mutation that markedly inhibits holo-Nox4 activity also disrupts binding of the B-loop to the DH domain indicating this interaction is functionally important for Nox4.

The B-loop/DH domain interaction may play several roles in function. First, it may help localize the FAD in close proximity to heme A, thus allowing rapid electron transfer. Calculations (46) place an upper limit on the distance between FAD and heme A of ∼22 Å, because distances larger than this would result in a rate too slow to account for the observed turnover of Nox2 (44, 46). Consistent with this limit, in other flavocytochromes for which structures have been determined, the FAD-to-heme distances are 9.9 Å for flavocytochrome c sulfide dehydrogenase and 6.3 and 5.9 Å for flavohemoglobin from Escherichia coli and Alcaligenes eutrophus, respectively (47, 48). Therefore, we suggest that the B-loop, by binding to the DH domain, can orient and localize the FAD and heme A in close proximity, allowing facile electron transfer. Furthermore, this binding occurs in such a way that the somewhat bulky B-loop itself does not sterically interfere with electron transfer. Consistent with this idea, the NADPH-binding subdomain, rather than the FAD-binding subdomain (Fig. 4), contains the major determinants of B-loop binding. This is consistent with a conceptual model in which the B-loop creates the domain interface but is localized somewhat to the side, allowing close approximation of the redox centers. In addition to maintaining distance requirements for FAD-heme electron transfer, the B-loop might also affect activity more directly, for example, by modulating the midpoint potentials of electron carriers, which is also expected to affect electron transfer rates (49, 50).

The generality of the B-loop/DH domain interface to other Nox isozymes is suggested by the observed binding of Nox2 B-loop peptides to the Nox2 DH domain, an interaction that is abolished in peptides containing the inactivating (34) R91E/R92E substitutions. The B-loop/DH domain binding appears to exhibit some specificity toward regulatory classes of Nox enzymes but only limited isoform specificity within regulatory classes. For example, the B-loop from a calcium-regulated Nox (Nox5) fails to bind to either Nox2 or Nox4 (Fig. 5). However, within the group of p22phox-dependent Noxes, Nox1–4, the Nox4 DH domain binds to B-loops from both Nox2 and Nox4. Similarly, the Nox2 domain binds to B-loops from both Nox2 and Nox4, suggesting the binding regions on the two DH domains are relatively well conserved. However, although Nox2 DH does not show a statistically significant preference for the B-loops from Nox2 versus Nox4, Nox4 DH shows a 4-fold binding preference for its own B-loop. Furthermore, Nox4 DH binds both loops more tightly than does Nox2. We speculate that the relatively tighter association in Nox4 might reflect an active electron transferring conformation in Nox4 and that such a conformation could account in part for the characteristic constitutive activity of Nox4.

The weaker affinity of Nox2 DH domain for Nox2 B-loop peptides suggests that Nox2 may require additional regulatory components to achieve the tighter DH domain/B-loop association seen in Nox4. To test this possibility while at the same time avoiding addition of multiple regulatory proteins, we investigated the effect of the p67N/p47N chimera protein on Nox2 B-loop binding to the Nox2 DH domain. This fusion protein retains the regions of p67phox and p47phox needed to stimulate Nox2 cell-free activity (51). There was no statistically significant difference between binding constants measured in the presence or absence of the chimera (data not shown). Thus, activating regions of p47phox/p67phox do not directly influence the binding of the B-loop, suggesting that a simple cooperative binding model does not apply. However, this does not rule out a more complex cooperative binding model involving one or more additional protein components such as p22phox, because it was not feasible to include this membrane component in the assay system. Alternatively, the B-loop/DH domain interaction may not be a dynamically regulated step in Nox activation (either by subunits or regulatory domains), but rather it represents an important static structural feature of Nox enzymes.

The Nox2 and Nox4 B-loops are able to bind reasonably well to their noncognate DH domains (Fig. 5). The functional consequence of such mismatched B-loop-DH domain pairs in an in vivo Nox ROS generation system can be seen in experiments using Nox2/Nox4 chimera proteins. A recent study demonstrated significant activity in a Nox4 (transmembrane domain, including B-loop)/Nox2 (DH domain) chimera (52). We have also observed significant activity in the reverse chimera, Nox2 (TM including B-loop)/Nox4 (DH domain).3 Taken together, both studies support the idea that the Nox2 and Nox4 B-loops can functionally compensate for each other. When the Nox4 B-loop in the Nox4 (TM domain)/Nox2 (DH domain) chimera was substituted for a Nox2 B-loop (i.e. when the Nox2 B-loop and DH domains were correctly paired), the activity was somewhat reduced (52). This was unexpected because we show that both the Nox4 and Nox2 B-loops bind to the Nox2 DH domain with approximately equal binding affinities (Fig. 5). However, without high resolution structural information, it is not possible to rationalize the structural perturbations that may occur upon switching a single loop within a domain. Although it is not possible to interpret the significance of the decreased activity in the above experiment, these studies point to the complicated nature of interactions at the TM-DH interface.

The theoretical isoelectric points of all B-loop peptides and recombinant protein were determined using the ExPASy proteomic server (53). All B-loop peptides have a calculated pI >8.9, and GST-Nox4 DH (full-length, NADPH-binding domain, and C-terminal half of the NADPH-binding domain) also have a calculated pI > 8. Because all of these species are positively charged at the assay pH, the interaction detected must be due to a discrete binding site rather than to nonspecific electrostatic interactions. GST-Nox2 DH domain, GST-Nox4-(304–420), and the N-terminal half of the Nox4 NADPH-binding site proteins all have calculated pI values of ∼6. Although these proteins are predicted to be negatively charged, they exhibit affinities for the various B-loop peptides that do not correlate with their isoelectric points. Thus, the binding cannot be explained on the basis of nonspecific electrostatic effects.

Previous studies reported inhibitory effects of Nox2 B-loop peptides and mutations on both Nox2 activity and on the assembly of cytosolic regulatory subunits with Nox2 (32–34, 54). These inhibitory effects suggested that the B-loop participates in important regulatory interactions with cytosolic regulatory subunits. This study indicates that B-loop binding to the DH domain is a common feature of both the cytosolic regulatory subunit-dependent Nox (Nox2) and -independent Nox (Nox4). Although it is possible that in Nox2 the B-loop might simultaneously bind both the DH domain and a regulatory subunit, the finding that the same mutations that interfere with subunit translocation also interfere with binding to the DH domain suggest another explanation, i.e. that the B-loop/DH domain interaction in Nox2 indirectly influences the binding of the regulatory subunits.

Our data point to a role of the B-loop in binding the DH domain. Thus, a disruption in this interaction might be predicted to inhibit Nox enzymes. We therefore tested the effect of cell-permeable Tat-fused Nox4 B-loop peptides (WT and R96E) on ROS generation in intact HEK 293 cells expressing Nox4 (data not shown). Significant inhibition was seen with the WT peptide, whereas the R96E and control Tat peptides both showed considerably less inhibition, consistent with in vitro binding results. However, these peptides also had large effects on cell attachment to the plates and possibly on cell viability, which confounded quantitative analysis of the data. Therefore, we feel that these results using Nox4 B-loop Tat peptides should be interpreted with caution, at least in this cell system.

In summary, the B-loop is conserved among all Nox/Duox proteins, and Nox1, Nox2, Nox3, and Nox4 share a conserved PBR within this structure. Mutagenesis reveals that, like earlier studies with Nox2, the PBR is also important for Nox4 activity. Nox4 B-loop peptides bind to the Nox4 DH domain, specifically to the N-terminal half of the NADPH-binding domain. Likewise, Nox2 DH domains bind to Nox2 B-loop peptides, albeit with somewhat weaker affinity than the Nox4 association. Both of these interactions are dependent on basic residues within the Nox2 and Nox4 B-loops, and neither DH domain interacts with the Nox5 B-loop peptide, which lacks a PBR. Taken together, the data support a model in which the B-loop functions as a binding sequence that links the heme-binding transmembrane domain with the FAD- and NADPH-binding DH domain. This binding is likely to affect the electron transfer between electron centers residing in both domains.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M. Quinn (Montana State University) for anti-p22phox antibody (44.1) and Dr. H. Ogawa (Fujita Health University) for providing short WT B-loop peptide.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants CA105116 and CA084138. This work was also supported by American Heart Association Grant 0815088E.

Y. Nisimoto and H. Jackson, manuscript in preparation.

H. Jackson, unpublished observations.

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- DH

- dehydrogenase

- PBR

- polybasic region

- Nox

- NADPH oxidase

- FITC

- fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- WT

- wild type.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bedard K., Krause K. H. (2007) Physiol. Rev. 87, 245–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambeth J. D. (2004) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 181–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambeth J. D., Krause K. H., Clark R. A. (2008) Semin. Immunopathol. 30, 339–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawahara T., Quinn M. T., Lambeth J. D. (2007) BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bánfi B., Molnár G., Maturana A., Steger K., Hegedûs B., Demaurex N., Krause K. H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 37594–37601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dupuy C., Ohayon R., Valent A., Noël-Hudson M. S., Dème D., Virion A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37265–37269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martyn K. D., Frederick L. M., von Loehneysen K., Dinauer M. C., Knaus U. G. (2006) Cell. Signal. 18, 69–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawahara T., Ritsick D., Cheng G., Lambeth J. D. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 31859–31869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ambasta R. K., Kumar P., Griendling K. K., Schmidt H. H., Busse R., Brandes R. P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45935–45941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abo A., Pick E., Hall A., Totty N., Teahan C. G., Segal A. W. (1991) Nature 353, 668–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knaus U. G., Heyworth P. G., Evans T., Curnutte J. T., Bokoch G. M. (1991) Science 254, 1512–1515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bánfi B., Clark R. A., Steger K., Krause K. H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 3510–3513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geiszt M., Lekstrom K., Witta J., Leto T. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 20006–20012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nunoi H., Rotrosen D., Gallin J. I., Malech H. L. (1988) Science 242, 1298–1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leto T. L., Lomax K. J., Volpp B. D., Nunoi H., Sechler J. M., Nauseef W. M., Clark R. A., Gallin J. I., Malech H. L. (1990) Science 248, 727–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lomax K. J., Leto T. L., Nunoi H., Gallin J. I., Malech H. L. (1989) Science 245, 409–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng G., Ritsick D., Lambeth J. D. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 34250–34255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lambeth J. D., Kawahara T., Diebold B. (2007) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43, 319–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nauseef W. M. (2004) Histochem. Cell Biol. 122, 277–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sumimoto H., Miyano K., Takeya R. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338, 677–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng G., Cao Z., Xu X., van Meir E. G., Lambeth J. D. (2001) Gene 269, 131–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geiszt M., Kopp J. B., Várnai P., Leto T. L. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 8010–8014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lassègue B., Sorescu D., Szöcs K., Yin Q., Akers M., Zhang Y., Grant S. L., Lambeth J. D., Griendling K. K. (2001) Circ. Res. 88, 888–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahadev K., Motoshima H., Wu X., Ruddy J. M., Arnold R. S., Cheng G., Lambeth J. D., Goldstein B. J. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 1844–1854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ago T., Kitazono T., Ooboshi H., Iyama T., Han Y. H., Takada J., Wakisaka M., Ibayashi S., Utsumi H., Iida M. (2004) Circulation 109, 227–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Segal A. W., West I., Wientjes F., Nugent J. H., Chavan A. J., Haley B., Garcia R. C., Rosen H., Scrace G. (1992) Biochem. J. 284, 781–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burritt J. B., DeLeo F. R., McDonald C. L., Prigge J. R., Dinauer M. C., Nakamura M., Nauseef W. M., Jesaitis A. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 2053–2061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imajoh-Ohmi S., Tokita K., Ochiai H., Nakamura M., Kanegasaki S. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 180–184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biberstine-Kinkade K. J., DeLeo F. R., Epstein R. I., LeRoy B. A., Nauseef W. M., Dinauer M. C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31105–31112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor W. R., Jones D. T., Segal A. W. (1993) Protein Sci. 2, 1675–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sumimoto H., Sakamoto N., Nozaki M., Sakaki Y., Takeshige K., Minakami S. (1992) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 186, 1368–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeLeo F. R., Yu L., Burritt J. B., Loetterle L. R., Bond C. W., Jesaitis A. J., Quinn M. T. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 7110–7114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park M. Y., Imajoh-Ohmi S., Nunoi H., Kanegasaki S. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 234, 531–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biberstine-Kinkade K. J., Yu L., Dinauer M. C. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 10451–10457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., Valentin F., Wallace I. M., Wilm A., Lopez R., Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Higgins D. G. (2007) Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirokawa T., Boon-Chieng S., Mitaku S. (1998) Bioinformatics 14, 378–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rost B., Yachdav G., Liu J. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W321–W326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiose A., Kuroda J., Tsuruya K., Hirai M., Hirakata H., Naito S., Hattori M., Sakaki Y., Sumimoto H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 1417–1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goyal P., Weissmann N., Rose F., Grimminger F., Schäfers H. J., Seeger W., Hänze J. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 329, 32–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hilenski L. L., Clempus R. E., Quinn M. T., Lambeth J. D., Griendling K. K. (2004) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 677–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hwang J., Kleinhenz D. J., Lassègue B., Griendling K. K., Dikalov S., Hart C. M. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 288, C899–C905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jameson D. M., Seifried S. E. (1999) Methods 19, 222–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vignais P. V. (2002) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59, 1428–1459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nisimoto Y., Motalebi S., Han C. H., Lambeth J. D. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 22999–23005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diebold B. A., Bokoch G. M. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2, 211–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moser C. C., Chobot S. E., Page C. C., Dutton P. L. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 1032–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ilari A., Bonamore A., Farina A., Johnson K. A., Boffi A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 23725–23732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen Z. W., Koh M., Van Driessche G., Van Beeumen J. J., Bartsch R. G., Meyer T. E., Cusanovich M. A., Mathews F. S. (1994) Science 266, 430–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gunner M. R., Honig B. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 9151–9155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moore G. R., Pettigrew G. W., Rogers N. K. (1986) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 4998–4999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ebisu K., Nagasawa T., Watanabe K., Kakinuma K., Miyano K., Tamura M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 24498–24505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.von Lohneysen K., Noack D., Wood M. R., Friedman J. S., Knaus U. G. (2009) Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 961–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gasteiger E., Gattiker A., Hoogland C., Ivanyi I., Appel R. D., Bairoch A. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3784–3788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rey F. E., Cifuentes M. E., Kiarash A., Quinn M. T., Pagano P. J. (2001) Circ. Res. 89, 408–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]