Abstract

The cytosolic nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 1 (NOD1)/CARD4 and NOD2/CARD15 proteins are members of NOD-like receptors recognizing specific motifs within peptidoglycans of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. NOD1 and NOD2 signal via the downstream adaptor serine/threonine kinase RIP2/CARDIAK/RICK to initiate NF-κB activation and the release of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines. In this report, we show that 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA), a cell-permeable, small molecule that has anti-tumor activity, can also activate NOD1 and NOD2. This was demonstrated: 1) by using human embryonic kidney epithelial (HEK) 293 cells transfected with a NF-κB reporter plasmid in combination with NOD1 or NOD2 expression plasmids; 2) by inhibiting DMXAA-induced chemokine (CXCL10) mRNA and protein production in the AB12 mesothelioma cell line using a pharmacological inhibitor of RICK kinase, SB20358; and 3) by using small interfering RNA to knock down NOD2 and lentiviral short hairpin RNA to knock down RICK. These findings expand the potential ligands for the NOD-like receptors, suggesting that other xanthone compounds may act similarly and could be developed as anti-tumor agents. This information also expands our knowledge on the mechanisms of action of the anti-tumor agent DMXAA (currently in clinical trials) and may be important for its biological activity.

Keywords: Diseases/Cancer/Therapy, Immunology/Innate Immunity, Immunology/Toll Receptors, Transcription/NF-κB, Tumor/Therapy, Nucleotide Binding Oligomerization Domain, Macrophage

Introduction

The innate immune system recognizes conserved microbial structures known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns through innate immune receptors termed pathogen recognition receptors. There are at least three major classes of pathogen recognition receptors: 1) the Toll-like receptors, which are transmembrane proteins with an extra-membranous domain involved in ligand recognition on either the extracellular surface or within endosomes and a cytoplasmic domain involved in signal transduction, 2) the nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD)2-like receptors, which are intracellular, cytoplasmic sensors, and 3) the retinoid acid-inducible gene 1-like receptors, which are cytosolic helicases that primarily sense viruses (1).

The NOD1 (also known as CARD4) and NOD2 (also known as CARD15) proteins are members of the NOD-like receptor family, defined by a tripartite structure consisting of a variable N-terminal caspase-recruitment domain (CARD), a central NOD domain, and a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat that detects pathogen-associated molecular patterns (1, 2). NOD1 is widely expressed in mammals but seems to be especially important in epithelial and mesothelial cells (3). NOD2 has a more restricted expression pattern, primarily expressed in leukocytes and intestinal epithelial cells. Information to date indicates that NOD1 and NOD2 sense bacterial molecules produced during the synthesis and/or degradation of cell wall peptidoglycans (PGNs). NOD1 recognizes PGN-related molecules containing the γ-d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid moiety (iE-DAP) that is produced by most Gram-negative and specific Gram-positive bacteria. NOD2 is activated by muramyl dipeptide (MDP), which is a conserved structure in virtually all types of PGN (1–6). Once the receptors recognize their specific agonists, both NOD1 and NOD2 self-oligomerize to recruit and activate the adaptor protein RICK (also known as RIP2), that is essential for the activation of both NF-κB and the MAPKs (1, 3, 7). RICK is a serine-threonine kinase that becomes polyubiquitinated upon interaction with NOD1 or NOD2 through homotypic CARD-CARD interactions (7) and ultimately recruits the kinase TAK1, which activates the NF-κB-activating complex (7). NF-κB subsequently activates transcription of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The Toll-like receptor adaptor MyD88 is not involved with NOD signaling, but interestingly, the activity of NOD1 and NOD2 ligands is markedly enhanced in the presence of Toll-like receptor agonists, such as lipopolysaccharide (8, 9).

Our group and others have been studying 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA, now called Vadimezan), a small molecule (classified as a xanthone) that was developed from flavone acetic acid (FAA, a flavanoid) (Fig. 1). DMXAA has strong anti-tumor activity through its ability to activate dendritic cells and macrophages (and to a lesser extent lymphocytes) via release of a variety of immunostimulatory cytokines and chemokines (10, 11). It has been established that DMXAA activates at least two key pathways in these cells. DMXAA can activate NF-κB, and this activation is markedly augmented by co-administration or priming with lipopolysaccharide (12). This appears to occur through a pathway that does not require the Toll-like receptor adaptor molecule MyD88 (11, 13). In addition to NF-κB activation, DMXAA activates the TANK-binding kinase 1-interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) pathway in macrophages through an unknown receptor (13). However, it should be noted that IRF3 activation does not explain the observed NF-κB activation (13). Despite almost two decades of research, the receptor for DMXAA that activates NF-κB has never been identified, although some evidence suggests it may be cytoplasmic (14).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representative of the chemical structures of MDP, iE-DAP, the flavone backbone, the parent flavanoid, FAA, DMXAA, and the xanthone parent backbone.

The ability of DMXAA to activate NF-κB in macrophages in a MyD88-independent fashion through a cytoplasmic process that is primed by lipopolysaccharide is reminiscent of the activities of MDP acting through NOD2. This similarity suggested the hypothesis that DMXAA might be a potential ligand for NOD2 and/or NOD1 that would then signal via the downstream adaptor serine/threonine kinase RIP2/RICK to activate NF-κB and induce the release of chemokines and cytokines. The purpose of this report was to test this hypothesis using transfected cell lines, pharmacologic inhibitors, and siRNA.

When we tested this hypothesis, we found that, like MDP or iE-DAP, DMXAA could stimulate NF-κB activation in human embryonic kidney epithelial (HEK) 293 cells, but only after transfection of NOD1 or NOD2 expression plasmids. Further support for the importance of the NOD proteins in DMXAA response was obtained by showing the RICK dependence of this process using the pharmacological inhibitor, SB203580. We also used lentiviral short hairpin RNA (shRNA) for RICK and small interfering RNA (siRNA) for NOD2 to inhibit DMXAA-induced chemokine release in a murine tumor cell line lacking an interferon response system. These studies thus identify DMXAA as a cell-permeable, non-bacterially derived compound that activates the NOD1 and NOD2 pattern receptors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Reagents

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were cultured and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mm glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (15, 16). AB12, a murine malignant mesothelioma cell line, derived from an asbestos-induced tumor in a Balb/c mouse, has been previously described in detail (17, 18). AB12 cells were cultured and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mm glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The cultures were maintained at 37 °C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. All cell lines were regularly tested and maintained negative for Mycoplasma contamination. FAA was obtained from the NCI, National Institutes of Health. DMXAA, SB203580, and polymyxin B were purchased from Sigma. DMXAA was dissolved in sterile, distilled, and deionized water. iE-DAP and MDP were purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). BIRB796 was purchased from Axon Medchem BV (Groningen, Netherlands).

Transient Transfection and NF-κB Promoter-Luciferase Reporter Assays

1 × 105 HEK 293 cells were plated in 24-well plates and transfected using LipofectAMINE 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. For NF-κB reporter assays, cells were co-transfected with 1–3 ng of mNOD2 or mNOD1 plasmids (InvivoGen) along with 50–70 ng of the NF-κB firefly luciferase reporter plasmid (Biomyx, San Diego, CA). Total plasmid DNA was equalized at 200 ng by addition of appropriate amounts of pcDNA control plasmid (6, 19). 18 h after transfection, cells were exposed to DMXAA, MDP (in conjunction with calcium phosphate to facilitate cell entry), and iE-DAP (with CaPO4). Luciferase activity was measured from cell extracts 24 and 42 h after addition of ligand using the luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI).

Permanent Transfections

HEK293 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and transfected at 50–70% confluence with 2.0 μg of NF-κB firefly luciferase reporter plasmid using LipofectAMINE 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. After 24 h, transfected cells were selected in the presence of 100 μg/ml hygromycin until stable clones were obtained. The 293/NF-κB-luc cells were then transfected with 2.0 μg of mNOD2 plasmids as above. Selection of the doubly transfected clones was performed with 100 μg/ml hygromycin and 10 μg/ml blasticidin. Empty vectors were transfected to generate control cell lines. To optimize our responses, we cloned individual 293/NF-κB-luc/mNOD2 cells and screened by exposing to MDP plus calcium phosphate. Cells were treated with various stimulators as described in the figure legends.

Hydrolysis Analysis

In some experiments, DMXAA, iE-DAP, MDP, and mouse tumor necrosis factor α were hydrolyzed in 6 m HCl at 95 °C for 16 h to physically dissociate DMXAA from potential PGN, amino acid, amino sugar compositions, and protein contaminants (6). The pH levels of the solutions were then brought to pH 7.4 using ammonium hydroxide.

Protein Studies for Chemokine Levels

The amount of IFN-inducible protein-10 (IP10)/CXCL10 secreted by cells activated by DMXAA was quantified using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit to detect murine IP10 (DuoSet Mouse CXCL10/IP10/CRG-2, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the instructions of the manufacturer (11).

siRNA, shRNA, and Immunoblotting

AB12 cells were seeded in 6-well tissue culture plates with antibiotic-free normal growth medium overnight. Transfection of siRNA control and NOD2-duplexed RNA oligonucleotides (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was performed using siRNA transfection reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After varying amounts of time, cells were stimulated with DMXAA (100 μg/ml) for 6 h, supernatants were collected for IP10 ELISA, and cells were harvested for RNA isolation as described below. RICK knockdown was performed by RNA interference using lentiviral shRNA plasmids (SuperArray, Frederick, MD) for mouse Ripk2 (TNFRSF, Receptor-interacting serine-threonine kinase 2). Five representative sequences were used to design the enclosed shRNA, GTAGTGCAGAAGTTGAAAGAT, CAGAGTTCCTCAAGTACTATT, CCAGTGTGAAGCATGATATAT, TGCTCTTGGTGTAAATTATCT, and GGAATCTCATTCGATGCATAC. Stable transfection of RICK shRNA plasmids was described as above. Knockdown of RICK protein expression in two representative cell lines was confirmed by immunoblotting. RICK protein levels were detected using polyclonal RIP2 antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). The membranes were reprobed with a β-actin antibody (Sigma) after stripping by Restore Plus Western blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Scientific, Philadelphia, PA) to verify equal loading.

RNA Isolation and Real-time, Reverse Transcription-PCR

Quantitation of mRNA levels was done as previously described (10, 11). Cells from control (phosphate-buffered saline) and DMXAA-treated cultures were harvested after 1- and 6-h treatment and homogenized in TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen). Three micrograms of RNA from each condition was reverse-transcribed using 0.5 μg of oligo(dT) (Promega), 10 mm deoxynucleotide triphosphates (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), and 1 unit of SuperScript III reverse transcriptase in 1× First-Strand Buffer and 10 mm dithiothreitol (Clontech) for 60 min at 50 °C. Equal amounts of cDNA from each condition were pooled. Primers were obtained from the literature or designed using standard protocols. Primer sequences can be obtained from the authors on request. Semi-quantitative analysis of gene expression was done using a Cepheid Smart Cycler (Sunnyvale, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol for SYBR Green kit supplied by Roche Applied Science. cDNA concentrations from each pool were normalized using β-actin or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase as a control gene. Relative levels of expression of each of the selected genes (-fold change versus saline control) were determined. Each sample was run in triplicate or quadruplicate, and the experiment was repeated at least three times. PCR products were electrophoresed in a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide.

Statistical Analysis

Unless otherwise noted, data comparing differences between two groups were assessed using an unpaired Student's t test. For comparisons with three or more groups, analysis of variance with appropriate post-hoc testing was used. Differences were considered significant when p was <0.05. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. Results are representative of two to four independent experiments.

RESULTS

DMXAA Stimulates NF-κB Activation in 293 Cells Only in the Presence of NOD2 or NOD1

To determine if DMXAA could engage NOD1 or NOD2, we employed the same HEK293 cell reporter system originally described to identify the peptidoglycan ligands of the NODs (2, 6). HEK293 cells (which do not express NOD1 or NOD2) were transiently co-transfected with nanogram amounts of NOD2, NOD1, or control plasmids at the same time as a NF-κB firefly luciferase reporter plasmid. Very low amounts of the NOD plasmids were used, because higher amounts can self-dimerize and activate NF-κB activity. The cells were then exposed to: 1) MDP, a known NOD2 agonist, at a concentration of 100 ng/ml; 2) iE-DAP, a known NOD1 agonist, at a concentration of 50 ng/ml; or 3) DMXAA. Because MDP and iE-DAP are not cell-permeable, they were added in the presence of calcium phosphate to enhance intracellular uptake, as previously described (2, 6, 19).

Fig. 2A shows that neither calcium phosphate, MDP plus calcium phosphate, nor low amounts of mNOD2 plasmid (1 ng) with calcium phosphate induced significant NF-κB activity in 293 cells transiently transfected with the NF-κB-sensitive firefly luciferase reporter plasmid. However, a significant (p < 0.01) 5-fold increase in NF-κB activity was seen when cells that had been transiently transfected with the mNOD2 plasmid and the NF-κB firefly luciferase reporter plasmid were exposed to MDP plus calcium phosphate. These data are consistent with previous reports (6, 19) (although the strength of response was somewhat lower) and demonstrate the system is operative in our hands.

FIGURE 2.

DMXAA stimulates NF-κB activity only in the presence of mNOD2, mNOD1. A, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with an NF-κB firefly luciferase reporter plasmid. Some cells were co-transfected with a control plasmid (first three bars) or with an mNOD2 plasmid (last two bars). 18 h after transfection, cells were exposed to calcium phosphate alone or the NOD2 ligand, MDP (100 ng/ml), in conjunction with calcium phosphate to facilitate cell entry. After 24 h, NF-κB promoter activation was measured by firefly luciferase activity normalized to control cells. Each transfection was performed in triplicate. Data are shown as the mean ± S.E. for one of three representative experiments with similar results. A 5.2-fold increase in activity was seen in the mNOD2 + MDP + calcium group (*, p < 0.01, versus all other groups). B, HEK293 cells were transiently co-transfected NF-κB firefly luciferase reporter plasmid and with control vector (first two bars) or mNOD2 plasmid (last two bars) as above. 18 h after transfection, cells were exposed to DMXAA (100 μg/ml) for 24 h, and then NF-κB promoter activation was measured as described above. Data shown are the mean ± S.E. for one of three representative experiments with similar results with each transfection performed in triplicate. DMXAA induced a small (1.9-fold), but significant (*, p < 0.05) increase in activity in the absence of NOD2 plasmid. However, a 6.9-fold increase in activity was seen in the mNOD2 + DMXAA group (**, p < 0.01 versus all other groups). C, HEK293 cells were transiently co-transfected with NF-κB firefly luciferase reporter plasmid and co-transfected with control vector (first three bars) or mNOD1 plasmid (last three bars). 18 h after transfection, cells were exposed to iE-DAP (50 ng/ml) in conjunction with calcium phosphate or DMXAA (100 μg/ml) for 42 h, and then NF-κB promoter activation was measured as described above. Data are shown as the mean ± S.E. for one of three representative experiments with similar results. Each transfection was performed in triplicate (*, p < 0.01, mNOD1 (1 ng) + DMXAA or mNOD1 + iE-DAP versus mNOD1 (1 ng alone).

We then tested the ability of DMXAA to engage mNOD2. Fig. 2B shows that in 293 cells transiently transfected with the NF-κB-sensitive firefly luciferase reporter plasmid low amounts of mNOD2 plasmid did not induce significant increased amounts of NF-κB activity. A small amount of stimulation of NF-κB activity (1.87-fold) was seen with DMXAA (p < 0.05). In contrast, a significant (p < 0.01) 6.9-fold increase in NF-κB activity was seen when cells transiently transfected with mNOD2 and NF-κB firefly luciferase reporter plasmid were exposed to DMXAA. DMXAA also activated NF-κB activity to a similar degree after transfection of hNOD2 in the same system (supplemental Fig. S1).

To determine whether DMXAA could also activate mNOD1, similar studies were undertaken, except the NOD1 ligand, iE-DAP, was used as a positive control (6). As shown in Fig. 2C, minimal NF-κB activity above control was seen in 293 cells transiently transfected with NF-κB firefly luciferase reporter plasmid that were exposed to DMXAA or iE-DAP. Co-transfection with even 1 ng of mNOD1 increased activity to 2-fold above control. However, these doubly transfected 293 cells showed significant (p < 0.01) increases in NF-κB activity of ∼5-fold over control after exposure to iE-DAP (consistent with previous studies (6)) and 8-fold over control after exposure to DMXAA.

To confirm and extend the results of the transient transfection system, studies were repeated using 293 cells that had been permanently transfected with the NF-κB luciferase reporter (HEK293/NF-κB-luc cells) or the NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid plus mNOD2 (HEK293/NF-κB-luc/mNOD2 cells). Consistent with transient transfection data, DMXAA up-regulated luciferase activity in the HEK293/NF-κB-luc/mNOD2 cells in a dose-dependent manner with optimal expression at a concentration of 100 μg/ml (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Dose and time course of up-regulation of luciferase activity in stably transfected HEK293/NF-κB-luc/mNOD2 cells. A, HEK293/NFκB-luc/mNOD2 cells were stimulated with increasing doses of DMXAA for 24 h and then NF-κB promoter activation was measured as described above. Data are shown as the mean ± S.E. for one of three representative experiments with similar results. Each sample was performed in triplicate (*, p < 0.01, DMXAA (100 μg/ml) or DMXAA (300 μg/ml) versus control (CTR)). B, HEK293/NF-κB-luc/mNOD2 cells were exposed to DMXAA or FAA (in conjunction with calcium phosphate), for 24 h with the indicated doses, and then NF-κB promoter activation was measured as described above. Data are shown as the mean ± S.E. for one of three representative experiments with similar results. Each sample was performed in triplicate (*, p < 0.01, DMXAA (100 μg/ml) versus CTR; **, p < 0.05, FAA (100 μg/ml) versus CTR). C, HEK293/NF-κB-luc/mNOD2 cells were pretreated for 24 h with control media, SB203580 (10 μm), or BIRB796 (0.1 μm). The cells were then stimulated with MDP (0.01 μg/ml, in conjunction with calcium phosphate), DMXAA (100 μg/ml), or TNFα (0.5 ng/ml). After 24 h, NF-κB promoter activation was measured as described above. The results are presented as mean ± S.E. SB203580 significantly decreased the response to MDP and DMXAA (*, p < 0.01, versus control). There was no effect on TNF-stimulated NF-κB promoter activation. Data are shown from one of three representative experiments with similar results; each sample was performed in triplicate. In D: right panel, HEK293/NF-κB-luc/mNOD2 cells were exposed to iE-DAP (0.1 μg/ml), MDP (0.01 μg/ml, in conjunction with calcium phosphate), TNFα (1 ng/ml), DMXAA (100 μg/ml), or 8-methyl-XAA (100 μg/ml). Left panel, cells were treated with the same agents that had been hydrolyzed in 6 m HCl at 95 °C for 16 h and then brought back to pH 7.0. 24 h after drug exposure, NF-κB promoter activation was measured as described above. Data shown are the means ± S.E. for one of three representative experiments with similar results. Each sample was performed in triplicate. Native MDP, TNFα, and DMXAA all significantly increased NF-κB activity compared with control (*, p < 0.01 compared with control-treated cells). However, after hydrolysis, only DMXAA significantly increased NF-κB activity compared with control. E, HEK293/NF-κB-luc/mNOD2 cells were exposed to polymyxin B (1 μg/ml), DMXAA (100 μg/ml), DMXAA (100 μg/ml) plus polymyxin B (1 μg/ml) for 24 h, and NF-κB promoter activation was measured as described above. Data are shown as the mean ± S.E. for one of three representative experiments with similar results. Each sample was performed in triplicate (*, p < 0.01, DMXAA or DMXAA plus polymyxin B versus control).

We also tested FAA, the parent flavonoid compound from which DMXAA was developed, (Fig. 1). Although slightly less potent than DMXAA, FAA was also able to induce luciferase activity (Fig. 3B).

To confirm the importance of RICK in this system, we treated the HEK293/NF-κB-luc/mNOD2 cells with the inhibitor SB203580 at a concentration of 10 μm for 24 h. SB203580 is a known inhibitor of RICK, along with p38 MAPK (20). Of course, there is an issue of specificity in all pharmacological inhibitors, and in this case, we therefore used a newly available compound, BIRB796, a highly selective inhibitor of all p38 MAPK isoforms (21) as a control at 0.1 μm for 24 h. MDP-stimulated NF-κB activity was inhibited by 57%, and DMXAA-stimulated NF-κB activity was inhibited by 55% using this dose of SB203580 (Fig. 3C). In contrast, TNFα-induced activation of NF-κB, which uses a different pathway from that of NOD/RICK, was unaffected (Fig. 3C). BIRB796 had no effects.

Taken together, we have reproduced the published HEK293/NOD/NF-κB luciferase promoter transfection system (6, 19) and shown that DMXAA was able to activate NF-κB promoter activity, but only in the presence of mNOD2 or mNOD1.

To study specificity, we exposed the NOD-2 transfected cells to iE-DAP (a NOD1 ligand), MDP, DMXAA, and 8-methyl-XAA, an analogue of DMXAA that has similar physicochemical properties with DMXAA. As shown in the left-hand side of Fig. 3D, MDP and DMXAA triggered clear NF-κB activation, whereas iE-DAP and 8-methyl-XAA had only minimal effects.

To rule out any sort of potential contamination of DMXAA with PGN, amino acids, amino sugars, proteins, or lipopolysaccharide contaminants, experiments were performed comparing effects of MDP, TNFα, and DMXAA before and after hydrolysis in 6 m HCl at 95 °C for 16 h, conditions previously shown to inactivate known NOD ligands (6). Hydrolysis completely blocked MDP- and TNFα-induced NF-κB activity, but had no effect on DMXAA-stimulated NF-κB activity (Fig. 3D). To further rule out endotoxin contamination, the lipopolysaccharide-binding antibiotic polymyxin B (11) did not block DMXAA-stimulated NF-κB activity (Fig. 3E).

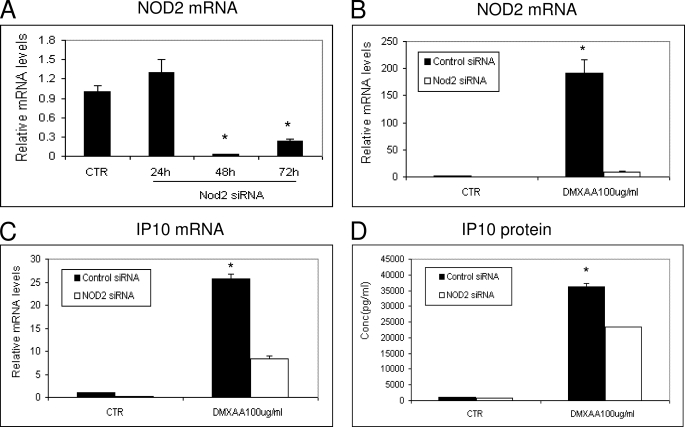

Inhibition of NOD2 with siRNA Reduces the Ability of DMXAA to Induce IP10 Message and Protein in AB12 Tumor Cells

We next wanted to demonstrate that DMXAA could not only activate a NF-κB luciferase reporter, but could also induce chemokine production via the NOD2 pathway. These experiments were complicated by the ability of DMXAA to strongly activate the IRF3/IFN pathway in most cell lines (13), making interpretation of results difficult. We therefore tested a number of murine cell lines to find one that had a defective interferon pathway, had high levels of NODs, responded to DMXAA by the production of a measurable chemokine, and was easily transfectable. We found one murine mesothelioma cell line (AB12) that met all these criteria. AB12 cells failed to up-regulate IFN-sensitive genes after treatment with IFN-β or produce IFN mRNA after exposure to an IFN-inducing virus (vesicular stomatitis virus) (data not shown). When compared with other murine tumors, this cell line expressed relatively high levels of NOD2 mRNA, and treatment of AB12 cells with DMXAA for 6 h induced a strong increase in the mRNA and secreted protein levels of the chemokine CXCL10 (IP10).

AB12 cells were thus transfected with NOD2 siRNA. Total RNA was extracted and quantified by RT-PCR at three time points. NOD2 siRNA was highly effective in down-regulating baseline levels of NOD2 mRNA at the 48- and 72-h time points (Fig. 4A). PCR was used because no antibody against mouse NOD2 with sufficient specificity was available. AB12 cells were thus treated with NOD2 siRNA or control siRNA for 48 h and then exposed to DMXAA for 6 h. Total cellular RNA was isolated for RT-PCR, and the supernatants were harvested for IP10 ELISA. Fig. 4B shows that the NOD2 siRNA significantly “knocked down” baseline NOD2 mRNA levels. Interestingly, DMXAA markedly up-regulated NOD2 mRNA, however the NOD2 siRNA clearly blunted this increase in NOD2 message (Fig. 4B). Importantly, knockdown of NOD2 mRNA significantly (p < 0.05) inhibited the response of AB12 cells to DMXAA; mRNA levels of IP10 were reduced by 70% (Fig. 4C), and secreted levels of IP10 protein were reduced by 40% after exposure to DMXAA (Fig. 4D). This partial response could be due to incomplete knockdown of NOD2, NOD1 activity, or DMXAA-induced stimulation of other pathways, such as IRF3.

FIGURE 4.

DMXAA-induced IP10 expression was inhibited by NOD2 siRNA. A, AB12 mesothelioma cells were transfected with control siRNA (CTR) or NOD2 siRNA. Total RNA was extracted at three time points, and the relative NOD2 mRNA levels were measured by RT-PCR (*, p < 0.01, CTR versus 48 or 72 h, data are shown as the mean ± S.E.). B, AB12 cells were transfected with control siRNA or NOD2 siRNA for 48 h, then cells were further incubated with or without DMXAA (100 μg/ml) for 6 h. The total RNA was isolated, and the relative NOD2 mRNA levels were measured as above. DMXAA strongly induced NOD2 mRNA expression levels, but this increase was markedly blunted by the siRNA (*, p < 0.01, control siRNA versus NOD2 siRNA in DMXAA groups, data are shown as the mean ± S.E.). C and D, AB12 cells were transfected with control siRNA or NOD2 siRNA for 48 h, then cells were further incubated with or without DMXAA (100 μg/ml) for 6 h. At this time point, the total RNA was isolated and the relative IP10 mRNA levels were measured by real-time RT-PCR (C), or the supernatants were removed and IP10 levels were measured by ELISA (D). The results are presented as mean ± S.E. (*, p < 0.01 CTR versus other groups) from one of four representative experiments with similar results.

Inhibition of RICK with shRNA Reduces the Ability of DMXAA Induce IP10 Message and Protein in AB12 Tumor Cells

To confirm the involvement of the RICK in this pathway of DMXAA-induced IP10 expression, we also performed studies in which we knocked down the NOD adaptor protein RICK (RIP2) using a plasmid expressing an shRNA inhibitor of RICK in AB12 cells. After transfection and selection, cells expressing the RICK shRNA had decreased levels of RICK mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 5, A and B). Transfected and control AB12 cells were then treated with IFNγ, iE-DAP, MDP, and DMXAA for 6 h. The supernatants were harvested for an IP10 ELISA and the cells for total RNA. As expected in the knockdown cells, the effects of MDP and iE-DAP were markedly and significantly inhibited. However, there was no inhibition of the IFNγ response, which is RICK-independent (Fig. 5, C and D, left panels). Importantly, RICK shRNA significantly (p < 0.05) blocked the response of the cells to DMXAA; mRNA levels of IP10 were reduced by 62% (Fig. 5C), and secreted levels of IP10 protein were reduced by 66% after exposure to DMXAA (Fig. 5D).

FIGURE 5.

DMXAA-induced IP10 expression after RICK knockdown or pharmacological inhibition of cellular kinase activity of RICK with SB203580. A and B, AB12 cells, stably transfected with control shRNA or RICK shRNA plasmids, were seeded and allowed to grow for 48 h in cell culture medium. Total RNA was extracted from cells, and baseline mRNA levels of RICK were measured by RT-PCR (A) (*, p < 0.01, control versus RICK shRNA, data are shown as the mean ± S.E.). Cells were lysed, and RICK protein levels were analyzed by immunoblot using an anti-RICK antibody (B). Expression levels of β-actin show equal loading of the lanes. C and D, AB12 cells, stably transfected with control shRNA or RICK shRNA plasmids, were incubated with or without IFNγ (5 ng/ml) iE-DAP (0.1 μg/ml) + CaPO4, MDP (0.01 μg/ml) + CaPO4, and DMXAA (10 μg/ml) for 6 h. The total RNA was isolated, and the relative IP10 mRNA levels were measured (C). IP10 protein was determined from the supernatant by ELISA kit (D). The results are presented as mean ± S.E. (*, p < 0.01, RICK shRNA versus control shRNA in iE-DAP, MDP, DMXAA groups) from one of three representative experiments with similar results. E and F, AB12 cells were pretreated for 24 h with medium alone, SB203580 (10 μm), or BIRB796 (0.1uM) and then stimulated with DMXAA for 6 h. Total RNA was isolated, and the relative IP10 mRNA levels were measured as above (E). IP10 protein was determined from the supernatant by ELISA kit (F). The results are presented as mean ± S.E. (*, p < 0.01, SB203580 versus control or BIRB796) from one of two representative experiments with similar results.

Pharmacological Inhibition of Cellular Kinase Activity of RICK with SB203580 Reduces DMXAA Responses

Finally, we investigated whether pharmacological blockade of RICK kinase activity would inhibit DMXAA-induced IP10 expression. AB12 cells were incubated with medium alone or SB203580 at 10 μm or BIRB796 at 0.1 μm for 24 h and then stimulated with DMXAA for 6 h. No significant inhibition of proliferation was detected (data not shown). The supernatants were harvested for IP10 ELISA, and total RNA was isolated for RT-PCR. SB203580 significantly (p < 0.05) down-regulated IP10 mRNA (Fig. 5E) and secreted levels of IP10 protein (Fig. 5F) by ∼72%. BIRB796 had no effect.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here demonstrate that DMXAA has the ability to permeate cells and activate murine (and human) NOD2 and NOD1 resulting in RICK/RIP2-dependent NF-κB activation and chemokine secretion. This is the first report that DMXAA signals through the NOD pathway, and to our knowledge, this is only the second report of activation of NOD signaling through a non-microbial molecule; the other example is the observation that lauric acid (C12:0 fatty acid) could also signal through the NODs (22).

Our conclusions are based on a number of experiments using approaches similar to those employed by others identifying NOD ligands (2, 5, 19, 20). We first reproduced the original HEK293 transient transfection assays employed by Girardin et al. (5–6) and Inohara et al. (2) in our laboratory using the NOD2 ligand MDP or the NOD1 ligand iE-DAP (along with calcium phosphate to facilitate cell entry). Similar to these agents, DMXAA induced only a very slight activation of the NF-κB-luciferase reporter plasmid until the NOD2 or NOD1 plasmids were also co-transfected (Fig. 2). The degree of activation we noted was somewhat less than others have noted (8-fold versus 20-fold), however, this may be due to technical issues, cell line differences, or differences due to the use of the murine versus human NOD plasmids. Dose-response issues may also be important. It appears that bacterial products such as MDP or iE-DAP are much more potent activators of NODs, with activity seen in the 50–100 ng/ml range. In contrast, DMXAA (like lauric acid) (22), has activity in the 10–100 μg/ml range. It is important to point out, however, that this concentration of DMXAA is quite “pharmacologically” relevant in that these plasma levels are observed in animal experiments and human trials (23).

To rule out any issues related to transient transfection, we also made stable HEK293 cell transfectants that expressed either the NF-κB-luciferase reporter plasmid alone or in combination with the NOD2 plasmid. As expected, the baseline levels of NF-κB-luciferase activity were higher (data not shown), however, addition of DMXAA increased activity only in the doubly transfected cell line in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 3).

We also wanted to extend these studies to a more physiological situation, where we could use inhibitors and siRNA to evaluate the role of DMXAA-induced NOD activation to induce chemokine mRNA and protein secretion. Finding an appropriate cell line proved to be challenging, because DMXAA is a strong activator of the IRF3 pathway (13), and thus induces an array of cytokines and chemokines through this pathway, thus complicating interpretation of results. We were able to find a mouse mesothelioma cell line, AB12, which had high levels of NOD2, a defective IFN-response pathway, was highly transfectable, and yet was still able to produce large amounts of the chemokine CXCL10 (IP10) after stimulation with DMXAA. Using this line, we were able to show inhibition of DMXAA-induced IP10 mRNA and protein secretion using siRNA to NOD2 and shRNA for RICK (Figs. 4 and 5).

As an additional approach, we also conducted experiments using the drug SB203580. SB203580 is a protein kinase inhibitor of the MAPK p38, casein kinase1, and cyclin G-associated protein kinase, but has been found to inhibit RICK activity with even greater potency (24–27). SB203580 reduced the activation of WT-RICK to a level similar to that of a kinase inactive (KI)-RICK, and MDP-stimulated activation of NF-κB gene transcription in NOD2-transfected HEK-293 cells was prevented by SB203580 (25). We validated this by showing inhibition of DMXAA-induced NF-κB activity in NF-κB/NOD2-stably transfected HEK-293 cells (Fig. 3C). Our finding that SB203580 significantly inhibited DMXAA-induced IP10 mRNA and IP10 protein in AB12 cells (Fig. 5, E and F), is thus consistent with the role of NOD2/RICK in this pathway. This effect was not due to MAPK activation, because we saw no inhibitory activity using the specific p38 MAPK inhibitor BIRB796. Of course, this inhibitor data alone would not be sufficient to support our hypothesis, if not confirmed by the more specific siRNA and shRNA data (Figs. 4 and 5).

The finding that a non-bacterial compound could activate NOD proteins is somewhat surprising given the reports of fairly stringent structural requirements of peptidoglycan fragments (6), although as mentioned above, there is one report of activation by lauric acid (22). To ensure that our DMXAA preparation was not contaminated by bacterial components, we showed the failure of the lipopolysaccharide-binding antibiotic polymyxin B to blunt the DMXAA response (Fig. 3E), and more convincingly, showed that the activity of DMXAA was not abolished by exposure to severe hydrolytic conditions that completely inactivated TNF-α or MDP (Fig. 3D).

The freely permeable nature of DMXAA has some potentially interesting implications. A series of reports in the 1990s showed that the ligand for NOD2, MDP (and the related derivative muramyl tri-peptide), had promise as an anti-cancer agent, and in fact Phase 3 clinical trials have been conducted in sarcoma (28). A major limitation, however, in this approach is the fact that neither MDP nor muramyl tri-peptide are cell-permeable, thus requiring packaging in liposomes to target tumor macrophages (29). When these preclinical studies of MDP were conducted, the mechanism of MDP signaling was not known. Based on current knowledge, we can now postulate that agents that activate inflammatory responses via NOD2 might be useful drug targets in the context of anti-tumor therapy. Identification of soluble NOD1 or NOD2 ligands (like DMXAA) could thus bypass the permeability issue, making such drugs more therapeutically valuable.

DMXAA was developed over 20 years ago (30) from FAA, a flavonoid compound that was initially synthesized by Lipha Pharmaceutical (Lyon, France) as part of their anti-inflammatory program (31). FAA was screened at the NCI, NIH for anti-cancer activity and was shown to be curative against a number of transplantable murine tumors (32). FAA, however, failed to demonstrate significant activity in a number of Phase I and II clinical trials as a single agent (33–35). FAA is shown here to activate NOD2 (Fig. 3B), although with less potency than DMXAA.

DMXAA is related to FAA but belongs to a class of oxygenated tricyclic ring heterocycles called xanthones (see Fig. 1) (36). The role of xanthones is well known in medicinal chemistry. They are widely distributed in plants, and natural or synthetic xanthone derivatives (like DMXAA) have a range of biological targets that include enzyme systems, cell surface receptors and calcium channels (36). They have been used as antimicrobials, anti-convulsants, anti-hypertensives, anti-platelet agents, anti-inflammatory drugs, and as anti-tumor agents. Other xanthones in clinical trials include Mangiferin, used as an anti-inflammatory agent, and psorospermin, a topoisomerase poison (36).

Although often classified as a “vascular disrupting agent,” our previous studies suggest that DMXAA functions primarily in mice as an immune modulator that requires a biphasic effect on innate and acquired immunity for efficacy and can activate macrophages and dendritic cells (10, 11). These inflammatory activities of DMXAA appear to be stronger in mouse cells compared with human cells (37, 38)3; however, the precise mechanisms of action are incompletely understood despite extensive preclinical and clinical investigations (12–14). Our data raise the possibility that activation of the NOD/RICK system (like the macrophage activator muramyl tri-peptide), may explain some of its clinical activity, however, species-specific NOD activation ability does not appear to explain the differences seen in mouse versus human cells, given that DMXAA was equally effective in activating human NOD2 as mouse NOD2 (supplemental Fig. S1).

We thus believe that DMXAA activates cells by at least two pathways: a TANK-binding kinase 1/IRF3 pathway and a NOD/RICK/NF-κB pathway (Fig. 6). We have no direct evidence that DMXAA binds to the NODs, however, we can show that DMXAA was not inducing NOD activation by merely increasing NOD levels within the 293 cells (supplemental Fig. S2). We do not know for certain how important the NOD pathways versus IRF3 or other activating pathways are in different cell types (i.e. macrophages). Studies using genetically altered mice will help answer these questions.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic diagram of signaling pathways activated by DMXAA. Previous work (13) has shown that DMXAA can activate TANK-binding kinase 1 to initiate IRF3 signaling. Our data indicate that DMXAA also activates NOD-like receptors NOD2 and NOD1 that interact with RICK to activate NF-κB signal pathways that regulate production of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines.

In summary, our results demonstrate that DMXAA is a non-bacterially derived, cell-permeable, small molecule activator of the intracellular pathogen recognition receptors NOD1 and NOD2. These findings expand the potential ligands for the important NOD-like receptors, perhaps indicating that other flavanoid or xanthone compounds may act similarly and could be developed as anti-tumor agents. It is also conceivable that such compounds may interact with NOD receptors in the intestine. This information also expands our knowledge on the mechanisms of action of the anti-tumor agent DMXAA (currently in clinical trials) (39) and may be important for its biological activity.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant PO1 CA 66726 from NCI.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

G. Cheng, J. Sun, Z. G. Fridlender, L.-C. S. Wang, L.-M. Ching, and S. M. Albelda, unpublished data.

- NOD

- nucleotide-oligomerization domain

- DMXAA

- 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid

- FAA

- flavone-8-acetic acid

- CARD

- caspase recruitment domain

- RICK

- rip-like interacting caspase-like apoptosis-regulatory protein (CLARP) kinase

- PGN

- peptidoglycan

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor κB

- MDP

- muramyl dipeptide

- iE-DAP

- γ-d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid

- TNFα

- tumor necrosis factor α

- wt

- wild type

- RT

- reverse transcription

- HEK293

- human kidney embryo 293

- IFN

- interferon

- IRF3

- IFN regulatory factor 3

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- IP10

- IFN-inducible protein-10

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- 8-methyl-XAA

- 8-methyl-xanthenone-4-acetic acid (XAA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen G., Shaw M. H., Kim Y. G., Nuñez G. (2009) Annu. Rev. Pathol. 4, 365–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inohara N., Ogura Y., Fontalba A., Gutierrez O., Pons F., Crespo J., Fukase K., Inamura S., Kusumoto S., Hashimoto M., Foster S. J., Moran A. P., Fernandez-Luna J. L., Nuñez G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 5509–5512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park J. H., Kim Y. G., McDonald C., Kanneganti T. D., Hasegawa M., Body-Malapel M., Inohara N., Nuñez G. (2007) J. Immunol. 178, 2380–2386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chamaillard M., Hashimoto M., Horie Y., Masumoto J., Qiu S., Saab L., Ogura Y., Kawasaki A., Fukase K., Kusumoto S., Valvano M. A., Foster S. J., Mak T. W., Nuñez G., Inohara N. (2003) Nat. Immunol. 4, 702–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girardin S. E., Boneca I. G., Carneiro L. A., Antignac A., Jéhanno M., Viala J., Tedin K., Taha M. K., Labigne A., Zähringer U., Coyle A. J., DiStefano P. S., Bertin J., Sansonetti P. J., Philpott D. J. (2003) Science 300, 1584–1587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Girardin S. E., Travassos L. H., Hervé M., Blanot D., Boneca I. G., Philpott D. J., Sansonetti P. J., Mengin-Lecreulx D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41702–41708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasegawa M., Fujimoto Y., Lucas P. C., Nakano H., Fukase K., Nuñez G., Inohara N. (2008) EMBO J. 27, 373–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Netea M. G., Ferwerda G., de Jong D. J., Werts C., Boneca I. G., Jéhanno M., Van Der Meer J. W. M., Mengin-Lecreulx D., Sansonetti P. J., Philpott D. J., Dharancy S., Girardin S. E. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 35859–35867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolfert M. A., Murray T. F., Boons G. J., Moore J. N. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 39179–39186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jassar A. S., Suzuki E., Kapoor V., Sun J., Silverberg M. B., Cheung L., Burdick M. D., Strieter R. M., Ching L. M., Kaiser L. R., Albelda S. M. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 11752–11761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace A., LaRosa D. F., Kapoor V., Sun J., Cheng G., Jassar A., Blouin A., Ching L. M., Albelda S. M. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 7011–7019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L. C., Woon S. T., Baguley B. C., Ching L. M. (2006) Oncol. Res. 16, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts Z. J., Goutagny N., Perera P. Y., Kato H., Kumar H., Kawai T., Akira S., Savan R., van Echo D., Fitzgerald K. A., Young H. A., Ching L. M., Vogel S. N. (2007) J. Exp. Med. 204, 1559–1569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woon S. T., Baguley B. C., Palmer B. D., Fraser J. D., Ching L. M. (2002) Oncol. Res. 13, 95–101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medvedev A. E., Piao W., Shoenfelt J., Rhee S. H., Chen H., Basu S., Wahl L. M., Fenton M. J., Vogel S. N. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 16042–16053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inohara N., Ogura Y., Chen F. F., Muto A., Nuñez G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 2551–2554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odaka M., Sterman D. H., Wiewrodt R., Zhang Y., Kiefer M., Amin K. M., Gao G. P., Wilson J. M., Barsoum J., Kaiser L. R., Albelda S. M. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 6201–6212 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim S., Buchlis G., Fridlender Z. G., Sun J., Kapoor V., Cheng G., Haas A., Cheung H. K., Zhang X., Corbley M., Kaiser L. R., Ling L., Albelda S. M. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 10247–10256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Opitz B., Püschel A., Schmeck B., Hocke A. C., Rosseau S., Hammerschmidt S., Schumann R. R., Suttorp N., Hippenstiel S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36426–36432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Windheim M., Lang C., Peggie M., Plater L. A., Cohen P. (2007) Biochem. J. 404, 179–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuma Y., Sabio G., Bain J., Shapiro N., Márquez R., Cuenda A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 19472–19479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao L., Kwon M. J., Huang S., Lee J. Y., Fukase K., Inohara N., Hwang D. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 11618–11628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J., Jameson M. B., Baguley B. C., Pili R., Baker S. D. (2008) Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 2102–2110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Godl K., Wissing J., Kurtenbach A., Habenberger P., Blencke S., Gutbrod H., Salassidis K., Stein-Gerlach M., Missio A., Cotten M., Daub H. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 15434–15439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pargellis C., Tong L., Churchill L., Cirillo P. F., Gilmore T., Graham A. G., Grob P. M., Hickey E. R., Moss N., Pav S., Regan J. (2002) Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 268–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hollenbach E., Vieth M., Roessner A., Neumann M., Malfertheiner P., Naumann M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 14981–14988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hollenbach E., Neumann M., Vieth M., Roessner A., Malfertheiner P., Naumann M. (2004) FASEB J. 18, 1550–1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyers P. A., Schwartz C. L., Krailo M. D., Healey J. H., Bernstein M. L., Betcher D., Ferguson W. S., Gebhardt M. C., Goorin A. M., Harris M., Kleinerman E., Link M. P., Nadel H., Nieder M., Siegal G. P., Weiner M. A., Wells R. J., Womer R. B., Grier H. E., Children's Oncology G. (2008) J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 633–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fidler I. J. (1994) Adv. Pharmacol. 30, 271–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rewcastle G. W., Atwell G. J., Baguley B. C., Calveley S. B., Denny W. A. (1989) J. Med. Chem. 32, 793–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atassi G., Briet P., Berthelon J. J., Collones F. (1985) Eur. J. Med. Chem. 20, 293–402 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corbet T. H., Bissert M. C., Wozniak A., Plowman J., Polin L., Tapzoglou E., Dieckman J., Valeriote F. (1986) Invest. New Drugs 4, 207–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Havlin K. A., Juhn J. G., Craig J. B., Boldt D. H., Weiss G. R., Koeller J., Harman G., Schwartz R., Clark G. N., van Hoff D. D. (1991) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 83, 124–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerr D. J., Kaye S. B., Cassidy J., Bradley C., Rankin E. M., Adams L., Setanoians A., Young T., Forrest G., Soukop M., Clavel M. (1987) Cancer Res. 47, 6776–6781 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kerr D. J., Maughan T., Newlands E., Rustin G., Bleehen N. M., Lewis C., Kaye S. B. (1989) Br. J. Cancer 60, 104–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinto M. M., Sousa M. E., Nascimento M. S. J. (2005) Curr. Med. Chem. 12, 2517–2538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barbera M., Kettunen M. I., Caputo A., Hu D. E., Gobbi S., Brindle K. M., Carrara M. (2009) Int. J. Oncol. 34, 273–279 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang L. C., Thomsen L., Sutherland R., Reddy C. B., Tijono S. M., Chen C. J., Angel C. E., Dunbar P. R., Ching L. M. (2009) Neoplasia 11, 793–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKeage M. J., Von Pawel J., Reck M., Jameson M. B., Rosenthal M. A., Sullivan R., Gibbs D., Mainwaring P. N., Serke M., Lafitte J. J., Chouaid C., Freitag L., Quoix E. (2008) Br. J. Cancer 99, 2006–2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.