Abstract

Insulin fibrillation provides a model for a broad class of amyloidogenic diseases. Conformational distortion of the native monomer leads to aggregation-coupled misfolding. Whereas β-cells are protected from proteotoxicity by hexamer assembly, fibrillation limits the storage and use of insulin at elevated temperatures. Here, we have investigated conformational distortions of an engineered insulin monomer in relation to the structure of an insulin fibril. Anomalous 13C NMR chemical shifts and rapid 15N-detected 1H-2H amide-proton exchange were observed in one of the three classical α-helices (residues A1–A8) of the hormone, suggesting a conformational equilibrium between locally folded and unfolded A-chain segments. Whereas hexamer assembly resolves these anomalies in accordance with its protective role, solid-state 13C NMR studies suggest that the A-chain segment participates in a fibril-specific β-sheet. Accordingly, we investigated whether helicogenic substitutions in the A1–A8 segment might delay fibrillation. Simultaneous substitution of three β-branched residues (IleA2 → Leu, ValA3 → Leu, and ThrA8 → His) yielded an analog with reduced thermodynamic stability but marked resistance to fibrillation. Whereas amide-proton exchange in the A1–A8 segment remained rapid, 13Cα chemical shifts exhibited a more helical pattern. This analog is essentially without activity, however, as IleA2 and ValA3 define conserved receptor contacts. To obtain active analogs, substitutions were restricted to A8. These analogs exhibit high receptor-binding affinity; representative potency in a rodent model of diabetes mellitus was similar to wild-type insulin. Although 13Cα chemical shifts remain anomalous, significant protection from fibrillation is retained. Together, our studies define an “Achilles' heel” in a globular protein whose repair may enhance the stability of pharmaceutical formulations and broaden their therapeutic deployment in the developing world.

Keywords: Amyloid, Insulin, NMR, Peptide Hormones, Protein Stability, Amyloidogenic, Insulin Dynamics, Insulin Fibrillation, Protein Misfolding, Therapeutic Design

Introduction

Insulin, a hormone central to the regulation of metabolism (Fig. 1), is a prototypical amyloidogenic protein. In pathological amyloid deposits, such proteins undergo non-native cross-β-assembly to form linear polymers (fibrils) (1), a hallmark of diseases of toxic misfolding (2). Fibrillation of insulin when stored above room temperature has long complicated its use in the treatment of diabetes mellitus (DM)4 (3). Why is insulin susceptible to fibrillation, and how may such degradation be prevented? These questions are of both basic and applied interest. In this study, we employ 13C and 15N NMR spectroscopy to identify a dynamic anomaly in an engineered insulin monomer (4). Molecular repair of an unstable polypeptide segment (its “Achilles' heel”) provides evidence of a link to the mechanism of fibrillation and yields novel analogs that may enhance the stability, efficacy, and safety of insulin replacement therapy in the treatment of DM in the developed and developing world.

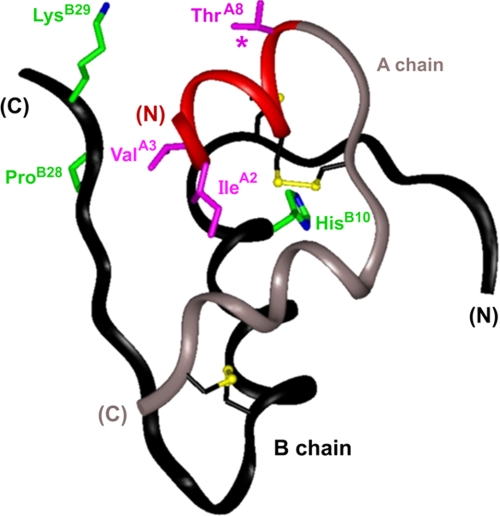

FIGURE 1.

Ribbon model of human insulin. Conformation of an insulin monomer as observed in a crystallographic T state protomer (2-Zn molecule 1; Protein Data Bank accession code 4INS). The A-chain is shown in red (residues A1–A8) and light gray (A9–A21); the B-chain is dark gray. Analog design focuses on residues IleA2, ValA3, and ThrA8 (magenta); active analogs have A8 substitutions (asterisk). NMR studies employed an engineered insulin monomer (DKP-insulin) with substitutions of wild-type residues HisB10, ProB28, and LysB29 (green). Also shown are cystines A7–B7 (largely obscured at top), A6–A11 (middle), and A20–B19 (bottom); sulfur atoms are depicted as gold spheres.

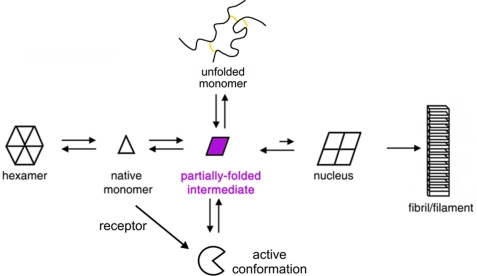

The mechanism of insulin fibrillation is outlined in Fig. 2. Of signal importance is conformational distortion of the monomer (Fig. 2, purple rhombus). Whereas native insulin (Fig. 2, triangle) may be sequestered within storage hexamers (left), non-native aggregation of distorted monomers leads to successive formation of amyloidogenic nuclei, protofilaments, and fibrils (right). The fact that susceptibility to fibrillation is conserved among vertebrate insulins5 may be a side consequence of the mechanism of action of the hormone (5); induced fit on receptor binding requires partial unfolding (Fig. 2, bottom), proposed to mimic, at least in part, the conformational distortions of an amyloidogenic intermediate (5–7). Because fibrillation does not require global unfolding (Fig. 2, top) (8), relative rates of fibrillation among extensive collections of insulin analogs (9) are uncorrelated with native-state stabilities as measured by chemical denaturation studies (ΔGu) (5). Whereas a large number of amino acid substitutions have been found that accelerate fibrillation (9), modifications compatible with biological activity that protect insulin from fibrillation are apparently rare.

FIGURE 2.

Mechanism of insulin fibrillation. Proposed pathway of insulin fibrillation via partial unfolding of monomer (9). The native state is protected by classical self-assembly (far left). Disassembly leads to equilibrium between native and partially folded monomers (open triangle and purple rhombus, respectively). This partial fold may unfold completely as an off-pathway event (open circle) or aggregate to form a nucleus en route to a protofilament (far right). This figure was adapted from Fink and co-workers (9).

Our study has three parts. First, to map sites of conformational distortability in an insulin monomer, we sought to exploit the 13C NMR chemical shift index (CSI) (10, 11) as a probe of ensemble-averaged protein dynamics. Based on associations between secondary structure and trends among 1Hα, 13Cα, 13Cβ, and 13CO chemical shifts, the CSI provides a rapid and sensitive method to identify α-helices, β-strands, and disordered segments in a protein without analysis of nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs) (10, 11). Application to an insulin monomer (12) uncovered a discrepancy between CSI- and NOE-based models. These results suggested that, despite maintenance of helix-related NOEs, the N-terminal segment of the A-chain (red in Fig. 1) undergoes conformational fluctuations between helical and nonhelical conformations in accordance with its rapid 1H-2H amide proton exchange in D2O (13). Second, to test whether this or other segments of insulin participate in a fibril-specific β-sheet, we employed 13C-based solid-state NMR to measure 13Cα, 13Cβ, and 13CO chemical shifts at selected sites in a powder sample (14). The probes suggested that on fibrillation the fluctuating A1–A8 α-helix undergoes an α → β transition as part of a global change in protein conformation. The solid-state NMR results are in accordance with prior evidence of an overall α → β transition obtained by infra-red and Raman spectroscopy (7, 15–17).

In the third and final part of this study, we sought to repair the A1–A8 segment as a test of its relationship to fibrillation and as a potential route to novel insulin analogs of clinical interest. Because this segment contains unfavorable β-branched residues at three positions (IleA2, ValA3, and ThrA8), an analog was prepared containing only non-β-branched residues at these sites to augment α-helical propensity (18–20). Together, the substitutions (IleA2 → Leu, ValA3 → Leu, and ThrA8 → His) impair thermodynamic stability (presumably due to perturbed tertiary packing by LeuA2 and LeuA3) and yet extend the lag time prior to fibrillation by 5-fold. Such extension is associated with a more helical pattern of 13Cα chemical shifts in the A1–A8 segment. Although these findings suggest that the intrinsic helical propensity of fluctuating α-helix can indeed modulate amyloidogenicity, the affinity of the analog for the insulin receptor (IR) is reduced by 100-fold, precluding its clinical utility. To obtain potential therapeutic analogs, substitutions were therefore restricted to the solvent-exposed position A8 at which site a variety of non-β-branched substitutions are well tolerated (21). Models were provided by rapid-acting insulin analogs in current clinical use (22–25).6 We have found that the A8 substitutions extend the lag time by between 2- and 3-fold. Although such protection is less marked than that of the above analog, the A8-modified insulin analogs exhibit high receptor-binding affinities. Such an analog exhibits native hypoglycemic potency in a rodent model of type 1 DM.

Our study is of dual basic and translational significance. From a biophysical perspective, it is remarkable that the anomalous 13C-based CSI signature of a globular protein correlates with both classical patterns of structural variability among crystal forms (26, 27) and its propensity for fibrillation. Furthermore, application of 13C NMR methods combined with protein engineering implies that a relationship exists between the intrinsic α-helical propensity of a peptide segment and fibrillation lag time. From a therapeutic perspective, mutagenesis of a fluctuating α-helix may augment the stability of rapid-acting insulin formulations, a potential benefit of particular relevance to continuous pump infusion (28). Because fibrillation-associated occlusion of the delivery system can cause metabolic decompensation leading to diabetic ketoacidosis (25), A8-modified rapid-acting insulin analogs may enhance the efficacy and safety of such devices. Whereas pump-based therapy is a technology of affluent societies, in the developing world, thermal fibrillation poses a barrier to the storage and use of insulin for treatment of DM. Together, these results suggest that joint 13C chemical shift mapping by solution- and solid-state 13C NMR may provide a general approach to detect sites of conformational distortability in amyloidogenic proteins as a foundation for their rational repair and therapeutic application.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Expression of DKP-Proinsulin

DKP-human proinsulin, containing substitutions HisB10 → Asp, ProB28 → Lys, and LysB29 → Pro, was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as described previously (29). The sites of substitution in the B-chain are illustrated in Fig. 1 (green). The protein was isotopically labeled by fermentation in M9 minimal medium containing [13C]glucose as the sole carbon source and [15N]ammonium chloride as the sole nitrogen source.

Proteolysis of DKP-Proinsulin

Conversion of DKP-proinsulin to a two-chain analog was accomplished by tryptic digestion. The isotopically labeled proinsulin (1 mg/ml) was dissolved in 100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). Sequencing-grade trypsin (Roche, Nutley, NJ) was added at a ratio of 1:500 (w/w). The digestion was performed at room temperature for 3 h and then applied to a C8 analytical column (25 × 0.46 cm; Vydac, Hesperia, CA) for separation by reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (rp-HPLC). Reactants and products were resolved with a methanol gradient (in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) from 45 to 70% over 60 min; peaks were pooled and identified by mass spectrometry. Whereas proinsulin yielded a symmetrical HPLC peak with retention time of 53 min, on trypsin digestion this fraction progressively disappeared, and two new peaks appeared with elution times of 32 and 45 min; each exhibited a small shoulder (supplemental Fig. S1). Mass spectrometry indicated that the C-peptide and related fragments eluted at 32 min, whereas a two-chain insulin analog eluted at 45 min (supplemental Fig. S2). This analog (52 residues) retains ArgB31 and so differs from DKP-insulin by one residue. NMR analysis indicated that the additional residue is disordered.

Chemical Synthesis of Insulin Analogs

Variant B-chains containing substitutions AspB28 or LysB28,ProB29 were obtained by oxidative sulfitolysis of insulin aspart (NovoLog®; Novo-Nordisk A/S, Bagsværd Denmark) or insulin lispro (Humalog®; Lilly) as described previously (30). Unlabeled or isotopically labeled DKP B-chains and the labeled wild-type A-chain were prepared by N-tert-butoxycarbonyl-based manual peptide synthesis as described previously (5); uniformly (13C,15N)-enriched N-tert-butoxycarbonyl amino acids (Ala, Gly, Ile, Leu, and Val) were obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. (Woburn, MA). Variant A-chains containing A8 substitutions were prepared by automated Fmoc (9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl)-based synthesis and derivatized by S-sulfonation. Insulin chain combination was effected as described previously (5). Purification of insulin analogs was accomplished by cation-exchange chromatography with carboxymethyl cellulose (CM-52, Whatman) (24 × 1.2 cm) using acetate buffer (pH 3.3) and a NaCl gradient. Final purification was by rp-HPLC using a C18 column (25 × 1 cm) with a 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid/acetonitrile solvent system. Combination of 20 mg of A-chain and 10 mg of the variant B-chain typically resulted in a final yield of 2 mg similar to that of wild-type chain combination. The purified analogs were observed to be a single component on analytical rp-HPLC (C18 column, 25 × 0.46 cm) using an acetonitrile elution gradient in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. Matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization mass spectra of the products were in accordance with predicted values.

Solution NMR Spectroscopy

Samples were prepared in nitrogen-purged H2O solutions (7% D2O) in 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.1 or 7.8) and 50 mm NaCl in a 300-μl Shigemi NMR tube; the protein concentration was ∼0.2 mm. Spectra were obtained between pH 7 and 8 due to progressive aggregation as the pH is reduced below 7, leading to macroscopic precipitation below pH 5.5. Restriction of NMR conditions to pH values >7 is associated with base-catalyzed amide proton exchange. Reverse-phase HPLC excluded detectable disulfide rearrangement during the course of data acquisition. NMR spectra were acquired at 25 °C and 700 MHz using a Bruker AVANCE spectrometer equipped with triple-resonance cryoprobe. Methods for heteronuclear resonance assignment and analysis of amide proton exchange are provided as supplemental material.

NMR Resonance Assignments

Homonuclear resonance assignment of [LeuA2,LeuA3,HisA8]DKP-insulin was obtained by standard two-dimensional methods as described previously (31). Heteronuclear main-chain (1H, 13C, and 15N) NMR resonance assignments were obtained by combined use of through-bond correlation spectra (HNCACB and CBCA(CO)NH). 13Cα and 13Cβ chemical shifts are provided in supplemental Table S2. In HNCACB spectra, amide resonances are correlated with intra-residue and preceding inter-residue 13Cα and 13Cβ resonances, whereas in CBCA(CO)NH spectra, a subset of connectivities is established only to the inter-residue 13Cα and 13Cβ resonances. Such correlations are illustrated in supplemental Fig. S3. Connectivities are broken at β-turn residues B7–B9 and B21 due to rapid amide solvent exchange.7 Side-chain spin systems were assigned by analysis of a series of isotope-directed TOCSY spectra (C(CO)NH-TOCSY, H(CCO)NH-TOCSY, and HCCH-TOCSY). Spin system classification was in each case consistent with main-chain assignments. Gaps or ambiguities in analysis of main-chain (through bond) correlation spectra were overcome by analysis of (through-space) NOEs as follows: three-dimensional 15N-NOESY and 13C-NOESY spectra as described in supplemental “Methods” (see supplemental Fig. S4).

Secondary Structural Propensities

Secondary structural propensities (SSP) were calculated using 13Cα and 13Cβ chemical shifts using the program SSP (32). For display, SSP scores were color-coded on a ribbon model of insulin using the program GRASP (33).

Solid-state NMR Spectroscopy

Two-dimensional solid-state 13C-13C NMR spectra of DKP-insulin fibrils (with uniform (15N,13C) labeling at specific sites (sample A, ValA3, IleA10, and LeuA16 in the A-chain; sample B, ValB2, GlyB8, and AlaB14 in the B-chain) were obtained at a 13C NMR frequency of 100.83 MHz and room temperature, using a Varian Infinity spectrometer and a Varian 3.2-mm magic angle spinning (MAS) probe. The finite pulse radio frequency-driven recoupling technique (34–36) was used for 13C-13C polarization transfer, with 23.3–23.6-kHz MAS frequencies, 12.72–12.88 μs 13C π pulses, and a 1.356–1.373-ms mixing period. 512 complex points were acquired in the t1 dimension, with a t1 increment of 18.88 μs, a 1.5-s recycle delay, and 160–320 scans per free-induction decay. 1H decoupling fields in the t1 and t2 dimensions were 106 kHz, with two-pulse phase modulation (37). Continuous-wave decoupling at 100 kHz without modulation was applied in the mixing period. Data were processed with NMRPipe software (38). 13C chemical shifts in solid-state NMR spectra were defined relative to tetramethylsilane, based on an external adamantane reference. Analysis of site-specific secondary structure based on 13C chemical shifts of uniformly 15N-13C-labeled residues in the fibrillar samples followed the approach used in studies of β-amyloid fibrils (14, 34, 39), where β-strand and non-β-strand segments were identified from secondary shifts relative to tabulated random-coil values (40).

Analysis of Crystal Structures

Thirteen T state crystallographic protomers (obtained from Protein Data Bank entries 4INS, 1APH, 1EV3, 1MPJ, 3MTH, 1TRZ, 1TYL, 1TYM, 2INS, 1ZNI, 2TCI, 1G7A, and 1BPH) were employed for analysis of conformational variability. Atoms omitted in deposited coordinates were built using InsightII (Molecular Simulations, Inc.). Structures were aligned based on the main-chain atoms of residues A1–A21 and B9–B28; segmental root-mean-square deviations (r.m.s.d.) were calculated as described in supplemental Table S1 and displayed using GRASP (33).

Preparation of Fibrils

Fibrillation was monitored by thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence on gentle agitation in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. Samples were prepared immediately prior to fibrillation. Proteins were made 60 μm in degassed buffer with 0.01% sodium azide at pH 7.4 and incubated in pre-sterilized glass vials with airtight sealed caps. Vials were rocked at 60 rpm. Aliquots were withdrawn at successive times and added to a ThT solution for fluorescence assay. Samples for solid-state NMR studies were prepared from DKP-insulin as described previously (17) by gentle agitation at 37 °C in 250 mm sodium chloride and 10 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.4) in a solution containing 60% ethanol (added to expedite fibrillation). In each case the presence of linear fibrils was verified by transmission electron microscopy as described previously (17).

Fluorescence Spectroscopy

ThT was made 1 mm in double-distilled water and stored at 4 °C in the dark. To monitor fibrillation, 5-μl aliquots obtained at the indicated time points were mixed with 3 ml of ThT assay buffer (5 μm ThT in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 100 mm NaCl). Fluorescence measurements were performed using an Aviv spectrofluorometer in 1-cm quartz cuvettes. Emission spectra were collected from 470 to 500 nm following excitation at 450 nm. The fibrillation lag time is defined as the time required to observe 2-fold enhancement of ThT emission.

Circular Dichroism

Far-UV CD was employed to monitor denaturant-induced unfolding as a probe of thermodynamic stability. Spectra were recorded using an Aviv spectropolarimeter (Aviv Biomedical, Inc., Lakewood, NJ) in 10 mm potassium phosphate and 50 mm KCl at pH 7.4. The protein concentration was ∼25–50 μm. Guanidine denaturation was monitored by ellipticity at 222 nm and fitted by nonlinear least square regression to a two-state model to extract apparent free energies (ΔGu) (7). Data were acquired at 25 °C.

Receptor Binding Assay

Studies employed a FLAG epitope-tagged holoreceptor (either IR isoform B or the homologous type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGFR)) transiently expressed in human 293 PEAK cells (American Tissue Culture Collection CRL-2828) (41, 42). The protocol is illustrated in supplemental Fig. S5. Receptors were partially purified by wheat germ agglutinin chromatography and further fractionated on binding to polystyrene 96-well plates (Nunc Maxisorb) coated with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (FLAG M2 immunoglobulin G; Sigma). Plates were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the immunoglobulin (100 μl/well of 40 μg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline). This protocol circumvents confounding binding of insulin or insulin analogs to endogenous IGFR; 293 PEAK cells do not express detectable endogenous IR. Additional experimental details are provided as supplemental material. Relative activity is defined as the ratio of specific dissociation constants as determined by competitive displacement of bound 125I-TyrA14 human insulin (in the case of IR) or 125I-Tyr31 human IGF-I (in the case of IGFR). In all assays the percentage of tracer bound in the absence of competing ligand was <15% to avoid ligand-depletion artifacts (41). To obtain high affinity analog-receptor dissociation constants, binding data were analyzed by nonlinear regression analysis using the model of Wang (43), which employs an exact mathematical expression to describe competitive binding of two different ligands to a protein molecule. Control studies using untransfected PEAK cell lysates demonstrated that this microtiter plate antibody-capture assay has negligible endogenous background.

Rodent Assay

Male Lewis rats (mean body mass ∼300 g) were rendered diabetic by treatment with streptozotocin as described previously (44). To test the in vivo potency of a representative insulin analog in relation to wild-type human insulin, protein solutions containing wild-type human insulin, a representative A8-modified insulin analog ([HisA8,AspB28]human insulin), or buffer alone (protein-free sterile diluent obtained from Lilly; composed of 16 mg of glycerin, 1.6 mg of meta-cresol, 0.65 mg of phenol, and 3.8 mg of sodium phosphate (pH 7.4 per ml)) were injected subcutaneously, and the resulting changes in blood glucose were monitored by serial measurements using a clinical glucometer (Hypoguard Advance Micro-Draw meter). To ensure uniformity of formulation, insulin analogs were each re-purified by rp-HPLC, dried to powder, dissolved in diluent at the same maximum protein concentration (300 μg/ml), and re-quantified by analytical C4 rp-HPLC; dilutions were made using the above buffer. Rats were injected subcutaneously at time t = 0 with 20 μg of insulin in 100 μl of buffer per 300-g rat. This dose corresponds to ∼67 μg/kg body weight, which corresponds in international units to 2 IU/kg body weight. Dose-response studies of wild-type insulin indicated that at this dose a near-maximal rate of glucose disposal during the 1st h following injection was achieved. Blood was obtained from clipped tip of the tail at time 0 and every 10 min up to 90 min. The efficacy of insulin action to reduce blood glucose concentration was calculated using the change in concentration over time (using least mean squares and initial region of linear fall) divided by the concentration of insulin injected.

RESULTS

Our results are presented in three parts. We first describe heteronuclear NMR studies to identify an anomaly in the 13C chemical shifts of an engineered insulin monomer. We next extend these findings by solid-state NMR to insoluble insulin fibrils containing selective isotopic labels in the A- or B-chains. Finally, based on these results, we describe the design of fibrillation-resistant insulin analogs. Together, these findings provide evidence for a relationship between the intrinsic α-helical propensity of a peptide segment and the amyloidogenicity of the intact protein.

Solution NMR Chemical Shift Mapping

Chemical Shift Index and Core-related NOEs

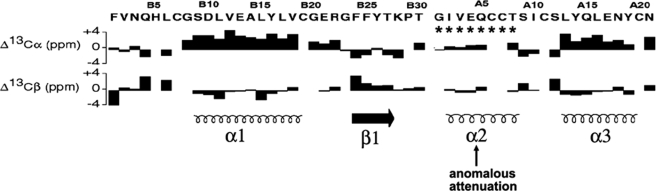

Secondary chemical shifts of Cα- and Cβ-carbons (the differences between observed and random-coil values) are sensitive to secondary structure (10, 11). CSI values are summarized by the histogram in Fig. 3 in relation to canonical elements of secondary structure (bottom). Positive (or negative) values correspond to resonances that are downfield (or upfield) of expected random-coil values. Whereas CSI values are in accordance with maintenance of α-helices 1 and 3 (residues B9–B19 and A13–A19, respectively) and the C-terminal B-chain β-strand (B24–B28), the A1–A8 segment exhibits marked attenuation of CSI values (Fig. 3, arrow and asterisks).

FIGURE 3.

Chemical shift index of DKP-insulin. Histograms show 13C NMR secondary shifts by residue in B-chain (left) and A-chain (right); sequences are provided at top. Upper histogram refers to Cα shifts, and lower histogram refers to Cβ shifts. Positive (negative) values indicate that the observed chemical shift is downfield (upfield) of expected random-coil frequency (10, 11). Canonical secondary structure of insulin is indicated at bottom: helix (spiral) or β-strand (arrow). CSI values in the A1–A8 segment (asterisk) are attenuated relative to α-helices 1 and 3. The sequence of insulin is shown with B-chain at left and A-chain at right to correspond to the N- to C-terminal order of B and A domains in proinsulin.

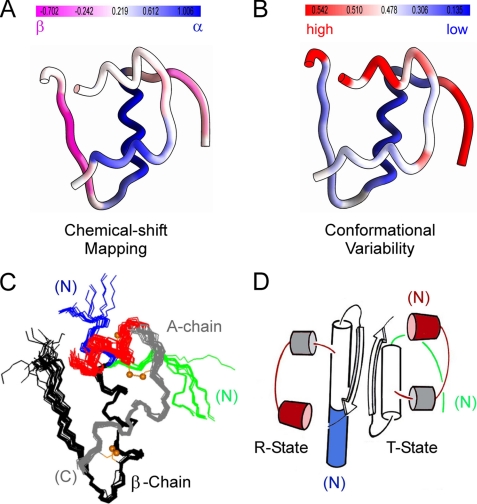

Heteronuclear resonance assignment also enabled application of an algorithm to convert chemical shift data to a single residue-specific SSP score (32). This score predicts at each residue the percentage of stably folded conformers with canonical secondary structure (α-helical or β-strand) in an ensemble. Limiting SSP scores of 1 or −1 imply formation of a fully formed α-helix or β-strand, respectively; intermediate scores (±0.5) imply 50% local occupancy; no information is provided regarding the nature of alternative noncanonical conformations. The SSP score of each residue in DKP-insulin (supplemental Table S2) is mapped onto the structure of an insulin monomer in Fig. 4A. Ribbon color in Fig. 4A ranges from violet (highest β-strand character) to white (no predominant secondary structure) to blue (highest α-helical character). Mean segment-specific SSP scores are ∼20% (N-terminal A-chain segment), 75% (C-terminal A-chain α-helix), and 100% (central B-chain α-helix). Strikingly, these segmental scores correlate with structural variability among crystallographic protomers as probed by main-chain atomic r.m.s.d. (mapped onto the structure in Fig. 4B; see “Discussion”). An alignment of crystallographic protomers is shown in Fig. 4C. With respect to strands, the N-terminal segment of the B-chain (residues B1–B6; light violet in Fig. 4A) exhibits attenuated β-character relative to its C-terminal segment (residues B24–B28; violet). The latter is thus pre-organized to engage its 2-fold-related partner to form a dimer-specific β-sheet, whereas the flexibility of the N-terminal segment foreshadows its conformational transition to α-helix in the TR transition (Fig. 4D).8

FIGURE 4.

Structure of insulin and relationship between conformational variability and chemical shift mapping. A, color-coded ribbon model of insulin T state indicating SSP score derived from 13C-secondary chemical shift (32). B, ribbon model of insulin T state color-coded according to main-chain r.m.s.d. values among collection of T state protomers aligned according to the main-chain atoms of B9–B24 and A1–A21. Red indicates greatest variability and blue indicates least variability. Quantitative scales in A and B are shown above each structure. C, superposition of crystallographic protomers (15 T states and 15 R (or Rf) states). The structures were aligned according to the main-chain atoms of residues B9–B24 and A12–A21. The A1–A8 α-helix in each protomer is shown in red; the variable secondary structure of the N-terminal segment of the B-chain is shown in green (extended in T state; right) or blue (extended α-helix in R state; left). D, ribbon model of wild-type insulin dimer in crystallographic T and R states. The color code is as in C. Structures in C were obtained from the following entries in the Protein Data Bank: T states: 4INS, 1APH, 1BPH, 1CPH, 1DPH, 1TRZ, 1TYL, 1TYM, 2INS, 1ZNI, 1LPH, 1G7A, 1MSO; R states: 1EV6, 1ZNJ, 1TRZ, 1ZNI, 1LPH.

Although its SSP score implies that the N-terminal A-chain segment undergoes significant main-chain conformational fluctuations, the core structure of insulin is not disrupted as indicated by maintenance of strong NOEs from the side chain of IleA2 to the core side chain of TyrA19. Native-like contacts are likewise maintained between the side chains of ValA3 and TyrB26 within an inter-chain crevice. The N-terminal A1–A8 segment also retains a subset of canonical α-helical NOEs. Such NOEs, exemplified by an (i, i + 3) contact between A2-Hα and A5-Hβ, are weaker than corresponding NOEs in other helices (31). Such attenuation presumably reflects nonhelical local conformations; the signal-to-noise ratio is further reduced by line broadening in this segment, itself a consequence of conformational exchange (45). We imagine that core side chains in the B-chain and C-terminal A-chain α-helix provide a nonpolar template for folding of the molten N-terminal A-chain segment as an amphipathic helix (see “Discussion”).

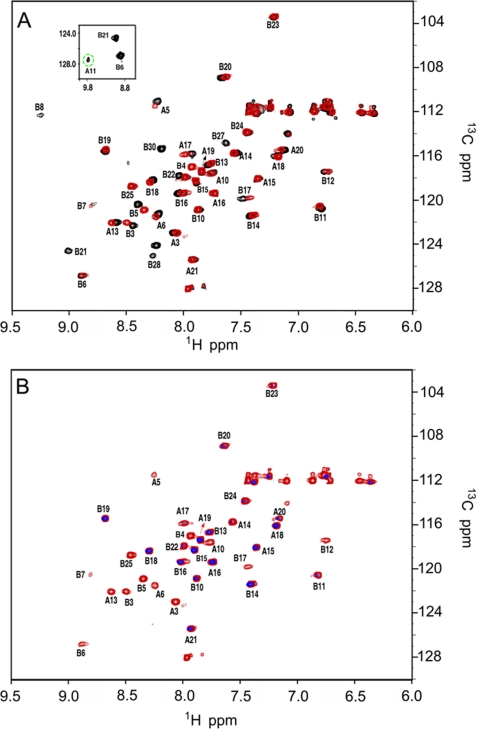

Amide Proton Exchange

Base-catalyzed amide exchange in DKP-insulin is too rapid to investigate by the standard D2O exchange method. We therefore employed the heteronuclear solvent presaturation 1H-15N HSQC method at 25 °C in H2O. Base-line HSQC spectra of DKP-insulin at pH 7.1 or 7.8 (Fig. 5A) exhibit favorable chemical shift dispersion in both 1H- and 15N dimensions; the inset shows the weak cross-peak of CysA11 (green dashed circle), observable only at the lower pH following prolonged acquisition (14 h). Although spectra acquired at pH 7.8 (Fig. 5A, red) or pH 7.1 (black) exhibit only slight changes in cross-peak positions, six additional cross-peaks (residues A11, B8, B21, B26, B27, and B28) are observed at the lower pH. Although for residues B26–B28 (lying at the edge of a β-strand), this pH effect is presumably due to less efficient base-catalyzed exchange, and for residues A11 and B8 (participating in chain reversals) the change in pH may also be affecting the extent of conformational broadening as these amide resonances exhibit unusually large 1H line widths.9

FIGURE 5.

1H-15N HSQC spectra of DKP-insulin and amide proton exchange. A, HSQC spectra at pH 7.8 (red) and 7.1 (black) and 25 °C; inset box contains weak cross-peak of A11 (green dashed circle) observable only at the lower pH following prolonged acquisition. Although only slight changes are observed in cross-peak positions, six additional cross-peaks are observed at the lower pH. B, amide-proton exchange in H2O probed by solvent presaturation for 2 s (black) relative to control irradiation (red) downfield of any protein resonances (12 ppm). Spectra were obtained at pH 7.8 and 25 °C. Disproportionate attenuation due to solvent presaturation is observed at sites not engaged in hydrogen bonding.

Additional 1H-15N HSQC spectra were acquired following 2 s of presaturation at either the solvent frequency or a control downfield of protein resonances (Fig. 5B). Disproportionate attenuation due to solvent presaturation is observed at multiple sites. These include sites both predicted and not predicted by the structure of DKP-insulin to be engaged in hydrogen bonding. Of its three α-helices, only the N-terminal A-chain segment lacks observable cross-peaks following solvent presaturation. Comparison of this limiting observation with predicted intrinsic rates of solvent exchange indicates that protection factors in the A1–A8 segment are very low (for example, <2.8 at position A4 relative to a predicted global protection factor base line of 880 ± 75; see supplemental material). Because the global stability of DKP-insulin (as inferred from guanidine denaturation experiments) (46) is 4.4 kcal/mol at 25 °C, amide proton exchange must be mediated by local or subglobal conformational fluctuations (13). The majority of residues in other α-helices (but not all) exhibit reduced cross-peak intensities (relative to the control spectrum), implying intermediate protection factors generally less than 200 and thus exchange via a subglobal mechanism. These observations imply that a large fraction of hydrogen bonds in the native state undergo transient breakage leading to amide proton exchange. Absence of protected amide protons in the A1–A8 segment and a broad range of lifetimes in the other helical segments have previously been observed at pD 1.9 in 20% deuterioacetic and 80% D2O (47).

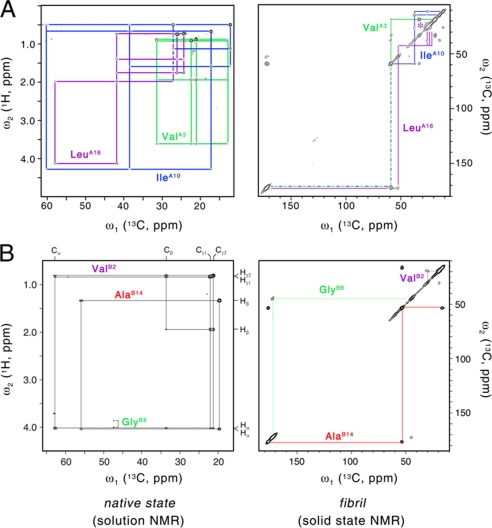

Solid-state NMR Chemical Shift Mapping

Uniformly enriched (13C, 15N) amino acids were incorporated into DKP-insulin at three positions in the A-chain (ValA3, IleA10, and LeuA16; sample A) or B-chain (ValB2, GlyB8, and AlaB14; sample B). These residues were chosen for their distinctive spin systems, interesting locations, and economy of labeling. In native insulin, these sites lie either in an extended and flexible N-terminal segment (ValB2), noncanonical turns (GlyB8 and IleA10), or α-helix (ValA3, LeuA16, and AlaB14). Whereas previous optical spectroscopic studies of insulin fibrils demonstrated a predominance of β-sheet (7, 15–17), such probes could not resolve residue-specific conformations. By contrast, two-dimensional solid-state 13C-13C NMR MAS correlation spectroscopy (14, 34, 39) can provide evidence for β-strand-associated isotropic chemical shifts relative to random-coil values (40).

Solution 13C NMR spectra are shown at left in Fig. 6; two-dimensional 13C-13C cross-polarization MAS spectra are shown at right. A-chain spin systems in sample A are shown in Fig. 6A (top), and B-chain spin systems in sample B are shown in Fig. 6B (bottom). Resonance assignment in the native state is in accordance with the general heteronuclear analysis of DKP-insulin (part I) and was verified by analysis of 1H-13C HSQC and 1H-13C HMQC-TOCSY spectra of samples A and B. Resonance assignment in the fibrillar powder was obtained by inspection of the two-dimensional 13C-13C MAS chemical shift correlation spectra (supplemental Table S3). In the fibril, residues A3, A10, A16, B2, and B8 exhibit β-sheet-associated Cα and Cβ chemical shift signatures. The chemical shifts of AlaB14 by contrast retain α-helical positions. Nonuniformity of A- or B-chain β-strands (or both) would be in accordance with the incongruent spacing between inter-chain disulfide bridges A7–B7 and A20–B19; CysA7 and CysA20 are separated by an even number of residues, and CysB7 and CysB19 are separated by an odd number. The 13C NMR solid-state MAS line widths at the labeled sites are in general similar to those observed in well ordered peptide fibrils (14, 34) with additional broadening observed at positions B2 and A16 (supplemental Fig. S6).

FIGURE 6.

Solid-state NMR studies of insulin fibrils. Assignment of unique labeled spin systems in DKP-insulin in native state in solution (left) and fibrillar state as powder (right). A, analysis of 13C-labeled residues A3, A10, and A16 in the two states. B, analysis of residues B2, B8, and B14 in the two states. NMR spectra: left panels, 1H-13C HMQC-TOCSY spectra at 32 °C and pH 7.6; right panels, 13C-13C two-dimensional MAS chemical shift correlation spectra in solid state. In fibrils, the resonances of ValB2 and LeuA16 are broader than those of the other labeled sites (see supplemental Fig. S6).

Design of Fibrillation-resistant Analogs

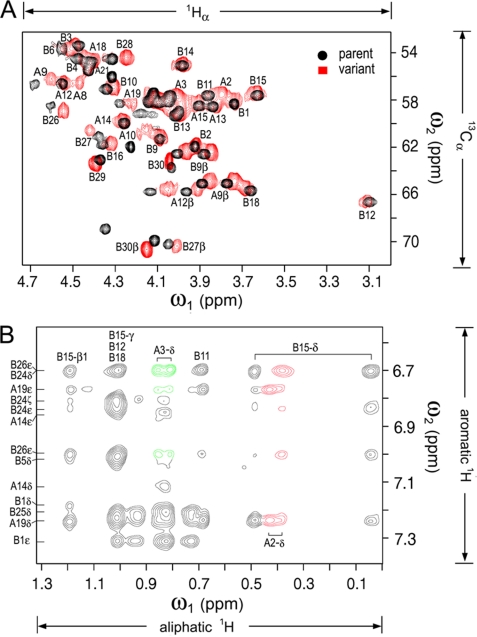

The sequence of the N-terminal segment of the A-chain (GIVEQCCT) contains three β-branched residues (underlined; magenta in Fig. 1) and so exhibits low intrinsic α-helical propensity. The side chain of IleA2 packs near the side chains of LeuA16, TyrA19, LeuB11, and LeuB15 in the hydrophobic core; the side chain of ValA3 projects into an inter-chain crevice near ValB12 and TyrB26; and the side chain of ThrA8 projects into solvent (Fig. 1, asterisk). To test whether simultaneous substitution of these residues by non-β-branched side chains would delay fibrillation by a mechanism unrelated to global thermodynamic stability, an analog of DKP-insulin was prepared with substitutions IleA2 → Leu, ValA3 → Leu, and ThrA8 → His. The analog is less stable than DKP-insulin (ΔΔGu −0.5 ± 0.2 kcal/mol; supplemental Fig. S7) and yet exhibits a lag time prior to fibrillation 5-fold longer than that of DKP-insulin as follows: 65 ± 9 versus 12.4 ± 2.5 days (DKP-insulin exhibits a base-line lag time longer than that of wild-type insulin (below) due to the stabilizing AspB10 substitution). Fibrillation was provoked by gentle agitation at 37 °C under neutral pH conditions as a model for the physical degradation of pharmaceutical formulations in a pump or challenged region of the developing world. The pattern of 13Cα chemical shifts, obtained at natural abundance by analysis of its two-dimensional 1H-13C-HSQC spectrum in D2O (Fig. 7A), exhibits a more α-helical pattern (supplemental Table S4). Despite the reduced thermodynamic stability of the analog, NOESY spectra exhibit a native-like pattern of inter-residue contacts, including the side chains of LeuA2 and LeuA3 (Fig. 7B). As in DKP-insulin, protected amide resonances are not observed in the A1–A8 segment (data not shown). The three-dimensional structure of [LeuA2,LeuA3,HisA8]DKP-insulin will be described elsewhere.10

FIGURE 7.

NMR studies of a fibrillation-resistant but inactive insulin analog. A, comparison of 1H-13C HSQC spectra of labeled DKP-insulin (black) and unlabeled [LeuA2,LeuA3,HisA8]DKP-insulin as observed at natural abundance (red). In the A1–A8 segment, 13Cα chemical shifts and SSP values exhibit a more α-helical pattern in the absence of segmental β-branched residues (see supplemental Table S4). B, NOESY spectrum of [LeuA2,LeuA3,HisA8]DKP-insulin in D2O (pD 7.6) exhibits a native-like pattern of inter-residue contacts involving the side chains of LeuA2 and LeuA3 (red and green, respectively). Assignments are as shown. The vertical axis (ω1) contains aromatic resonances, and the horizontal axis (ω2) aliphatic resonances.

Insulin analogs containing substitutions LeuA2, LeuA3, and HisA8 would be without clinical benefit due to low activity; binding of the above DKP-insulin variant is 100-fold lower than that of DKP-insulin (supplemental Fig. S8). Such impaired affinity is in accordance with previous studies showing that IleA2 and ValA3 are singly required for receptor binding (48).11 Because ThrA8 is by contrast not conserved and because diverse side chains at A8 are readily accommodated on the surface of insulin (21), we investigated whether non-β-branched substitutions only at A8 would protect, at least partially, insulin from fibrillation.12 Our studies employed rapid-acting insulin analogs in current clinical use. We chose His and Lys due to their natural occurrence among vertebrate insulin sequences12 and previous structural characterization of HisA8-insulin and LysA8-insulin as analogs with enhanced receptor-binding affinity (21, 49). In isolated peptides, His and Lys exhibit greater intrinsic α-helical propensity and C-capping potential than does Thr (20).

We chose to test A8 substitutions in the context of AspB28-insulin (insulin aspart, the active component of NovoLog®; Novo-Nordisk A/S) and [LysB28,ProB29]insulin (KP-insulin, also designated insulin lispro, the active component of Humalog®; Lilly) (23, 50). These rapid-acting analogs are less stable than wild-type insulin, but their pharmacokinetic properties are advantageous for pump-based continuous infusion in patients with DM (24, 51, 52). Insulin solutions in external pumps may experience agitation at elevated ambient temperatures, conditions conducive to fibrillation. The stability of insulin within pumps and catheters is of clinical concern as fibril plugs can occlude delivery, exposing patients with type 1 DM to rapid metabolic decompensation (diabetic ketoacidosis) (25). The risk of occlusion of current insulin analog formulations is ordinarily mitigated by zinc-mediated hexamer assembly (1, 3, 53).

Lag times prior to fibrillation were measured in zinc-free protein solutions in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) on gentle agitation at 37 °C in the presence of an air-water interface. Under these conditions, the rapid-acting analogs AspB28-insulin and [LysB28,ProB29]insulin form fibrils more quickly (1.7 ± 0.3 and 2.6 ± 0.3 days, respectively) than does native human insulin (3.5 ± 0.6 days; column 4 in Table 1). Whereas the analogs are monomeric under conditions of study, the delay in wild-type fibrillation may be due in part to its partial dimerization and in part to intrinsic difference between corresponding monomers. Strikingly, the A8-modified analogs exhibit prolonged lag times (∼6 days). The lag time of TrpA8-modified insulin lispro is also prolonged but to a lesser extent (4.2 ± 0.3 days). Natural abundance 1H-13C HSQC spectrum of a representative analog (LysA8-KP-insulin) revealed no significant changes in A1–A8 SSP scores (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Physical and biological properties of insulin analogs

| Protein | Activitya | Stabilityb | Fibr. lag timec |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin | 1.0 | 3.3 | 3.5 ± 0.6 |

| KP-insulind | 0.9 | 2.8 | 2.6 ± 0.3 |

| HisA8-KP-insulin | 2.9 | 3.9 | 6.2 ± 0.8 |

| LysA8-KP-insulin | 3.1 | 3.2 | 6.3 ± 0.6 |

| AspB28-insuline | 1.2 | 2.9 | 1.7 ± 0.3 |

| HisA8-AspB28-insulin | 3.4 | 3.7 | 5.8 ± 0.3 |

a Activity is defined as relative affinity of the analog at room temperature for an immobilized C-terminal (FLAG)3 epitope-tagged and detergent-solubilized IR (isoform B). Values shown have uncertainties of ±15% based on estimates of means ± S.E. The hormone-receptor dissociation constant under these conditions is ∼0.060 ± 0.009 nm.

b The stability (kcal/mol) is defined as the free energy of unfolding (ΔGu) at 25 °C as inferred (in the absence of zinc ions) from guanidine denaturation studies by application of a two-state model (74) Uncertainties are ±0.1 kcal/mol.

c Fibrillation (Fibr.) lag time (days) is defined by the onset of amyloid-enhanced fluorescence of ThT as described (7). Proteins were made 60 μm zinc-free in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and gently rocked at 37 °C in a glass vial in the presence of an air-water interface.

d KP indicates substitutions ProB28 → Lys and LysB29 → Pro as employed in the rapid-acting insulin product Humalog® (Lilly).

e AspB28-insulin (also known as insulin aspart) is the active component of the rapid-acting insulin product NovaLog® (Novo-Nordisk A/S).

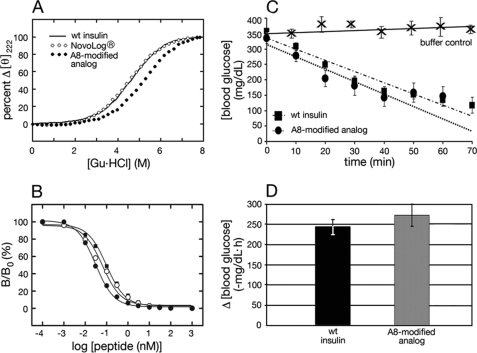

Analogs were characterized with respect to receptor-binding affinity and thermodynamic stability (columns 2 and 3 in Table 1) as illustrated in Fig. 8A (CD-detected guanidine denaturation studies) and Fig. 8B (IR competitive-displacement binding assay; isoform B). The A8-modified analogs each exhibit enhanced affinities and stabilities relative to respective parent analogs. Although the stability of LysA8-KP-insulin (ΔGu 3.2 ± 0.1 kcal/mol) is similar to that of wild-type insulin (3.3 ± 0.1 kcal/mol) under conditions in which both are monomeric, the fibrillation lag time of the LysA8 analog is prolonged by almost 2-fold. The A8 substitutions do not augment cross-binding to IGFR (data not shown).

FIGURE 8.

Stability and activity of a representative insulin analog. A, protein denaturation studies. CD-detected protein denaturation studies demonstrate that AspB28-insulin (○) is less stable than wild-type insulin (solid line), whereas [HisA8,AspB28]insulin (●) is more stable than wild type (wt). In each case fractional change in ellipticity is plotted as a function of concentration of guanidine HCl at 25 °C. Analysis by a two-state model (74) yields estimates of ΔGu (see Table 1). B, receptor-binding assay. Competitive displacement of 125I-labeled insulin from the insulin receptor (isoform B; IR-B) in the presence of varying concentrations of wild-type human insulin (■), AspB28 analog (○, or A8-modified analog ([HisA8,AspB28]insulin; ●). C, initial rate of decline of blood glucose following subcutaneous injection of wild-type human insulin (■), the A8-modified analog ([HisA8,AspB28]insulin; ●), or control diluent injection (×). Human insulin or the insulin analog was given at dose 20 μg per rat (∼300 g body weight). Mean initial values of blood glucose (n = 5 for each group) were similar in sets of rats treated with the analog or wild-type insulin. Error bars represent S.D. Control studies were performed at a different date using rats of similar body mass and degree of hyperglycemia. D, histogram showing initial rate of decline (mean ± S.D.) among the two groups of diabetic rats (n = 5 for each group). Although the in vitro IR-binding affinity of [HisA8,AspB28]human insulin is higher than that of human insulin (Table 1), their biological potencies in this rat assay are indistinguishable.

The hypoglycemic potency of a representative A8-modified rapid-acting analog ([HisA8,AspB28]insulin) was tested in a streptozotocin-induced rat model of DM. Five rats were treated with wild-type insulin, and five rats with the analog at a standard dose of 20 μg per rat (mean body weight ∼300 g). Following subcutaneous injection, the rate of fall in blood glucose concentration was indistinguishable (Fig. 8, C and D), 243 ± 19 mg/dl/h (wild type) and 272 ± 27 mg/dl/h (analog). This difference is not statistically significant. In control studies injection of buffer alone did not cause a reduction in blood sugar (Fig. 8C, top trace).

DISCUSSION

Insulin provides a classical model for studies of protein folding and assembly (27). Stored in β-cells as zinc hexamers, insulin dissociates in the bloodstream to function as a zinc-free monomer (54). Amino acid substitutions have widely been investigated for possible favorable effects on the pharmacokinetics of insulin action following subcutaneous injection. Such substitutions (such as those in NovoLog® and Humalog®) can be associated with more rapid fibrillation and poorer physical stability. Indeed, in a series of 10 analogs tested by Fink and co-workers (9) for susceptibility to fibrillation, each was found to be more susceptible to fibrillation (at pH 7.4 and 37 °C) than human insulin. Because the substitutions were at diverse sites and presumably associated with a wide range of changes in thermodynamic stability, no structural criteria or rules emerged for the screening or design of fibrillation-resistant insulin analogs. If obtained, such analogs would be of interest in relation to the safety and efficacy of insulin replacement therapy in DM.

This study sought to augment the resistance of insulin to fibrillation based on foundational biophysical principles. Our approach built on the crystallographic data base of insulin structures to investigate sites of conformational variability in an engineered monomer as probed by anomalous CSI attenuation and amide proton exchange in solution. These results focused attention of the A1–A8 segment, next shown by solid-state NMR to participate in formation of a fibril-specific β-sheet. Finally, the NMR observations suggested a strategy to protect insulin from fibrillation by replacement of β-branched side chains in this segment. We discuss the progression of these ideas in turn below. Although our present efforts are ultimately motivated by the goal of improved therapy for DM, we envisage that distinct conformations of insulin are required at discrete steps of biosynthesis and receptor binding. Conformational variation is thus likely to foreshadow the complementary structural requirements of these diverse processes (see supplemental “Discussion”).

SSP Scores and Crystallographic Data Base

Crystal structures of insulin (26, 27) contain canonical architectural elements (i.e. globular packing of α-helices, β-turns, and β-sheets to define polar surfaces and a hydrophobic core). A complementary view has emerged from NMR (31, 55). Although conventional NMR-derived models (12, 31, 55) are similar to crystallographic T states (right-hand protomer in Fig. 4A) (27), this study provides evidence for unequal segment-specific helical stabilities. An anomalous pattern of 13C chemical shifts in the native state provides evidence of a breakdown of the cooperativity of folding in the α-helical domain (56).

The first part of our study exploited an empirical correlation between secondary structure and the 13C CSI, an NOE-independent structural probe (10, 11), to investigate conformational variability. The 13Cα secondary shift is most sensitive to helical structure, whereas the 13Cβ secondary shift is most sensitive to the folding of a β-strand. A generalization of the index has led to the development of the SSP algorithm (32), which at a given position predicts the percentage of conformers in an ensemble that are helical or strand. Correlation was observed between SSP and conformational variability among crystallographic protomers.

The crystallographic data base provides information regarding sites of mobility and conformational change. Although each individual structure is conventionally organized, comparison of multiple protomers reveals local and nonlocal differences, including variation in main-chain dihedral angles, rigid-body displacement of secondary structural elements, alternate secondary structures, and propagated changes in core packing. Evidence for the flexibility of the monomer in solution was previously obtained from Raman spectroscopy (17). In the monomer, β-sheet- and α-helix-specific vibrational bands (amide I) are anomalously broadened relative to corresponding bands in insulin dimers and hexamers, suggesting that conformational excursions in the monomer are dampened on assembly. Complementary evidence for assembly-dependent stabilization has been provided by CD (57). Unlike the monomer, the phenol-stabilized R6 zinc insulin hexamer exhibits spectroscopic features characteristic of well organized globular proteins (including standard Raman line widths (17), CD amplitudes (58), 1H NMR line widths (59), and 13C NMR chemical shifts (60)). The solution structure of an R6 hexamer is essentially identical to corresponding crystal structures (60, 61).

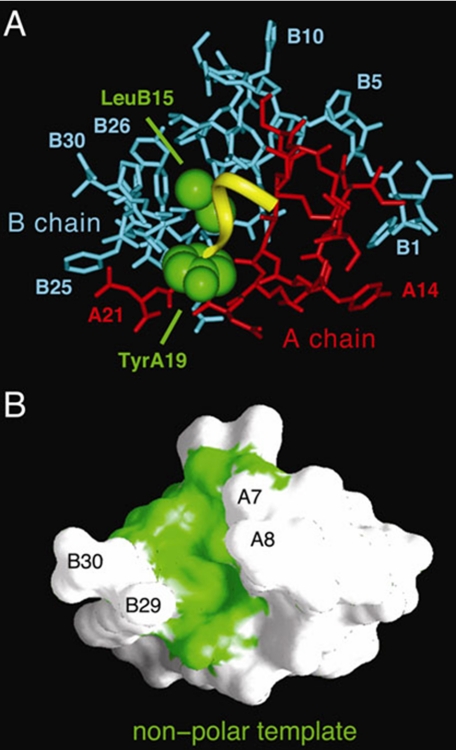

We imagine that the A1–A8 segment (Fig. 9A, yellow ribbon) flexibly packs against nonpolar template provided by the underlying core of the insulin (Fig. 9B, green surface). Quantitative insight is provided by analysis of segment-specific variation in degree of structural uniformity (or nonuniformity) among α-helices. Because an insulin monomer in solution resembles the crystallographic T state (12, 30, 55), we have focused on a collection of 13 such protomers; representative T state structures were extracted from T6 and T3Rf3 zinc hexamers (27, 62) and the T2 dimer (63). This collection exhibits significant structural variation. Global alignment based on the main-chain atoms of A1–A21 and B9–B28 yields r.m.s.d. of 0.46 Å for aligned atoms and 1.20 Å for side chains. In this alignment, the three constituent α-helices (residues A1–A8, A12–A18, and B9–B19) differ in overall position. A segment-specific measure of structural uniformity is provided by the mean main-chain r.m.s.d. within a given helix as follows: low for the central B-chain α-helix (0.25 ± 0.10 Å), intermediate for the C-terminal A-chain helix (0.47 ± 0.33 Å), and high for the N-terminal A-chain helix (0.64 ± 0.55 Å).

FIGURE 9.

Environment of the A1–A8 α-helix and underlying nonpolar template. A, stick-and-ribbon model of wild-type insulin monomer (protomer 1 in T6 crystal structure 4INS) showing the A1–A6 helical segment (yellow ribbon) and underlying nonpolar side chains of TyrA19 and LeuB15 (space-filling representation; green) relative to the remainder of the A-chain (red) and B-chain (blue). Selective other residues are as labeled. B, surface topology of insulin with A1–A6 segment removed exhibits a hydrophobic groove (green) into which the A1–A6 segment docks as an amphipathic α-helix constrained by the A6–A11 and A7–B7 disulfide bridges (not shown). The groove is bordered by residues A7 and A8 on one side and B29 and B30 on the other.

The correlation between NMR-based SSP scores and crystallography-based r.m.s.d. values among α-helices is shown in schematic form in Fig. 4, A and B. An SSP score near zero (white in Fig. 4A) indicates significant conformational averaging in solution, corresponding to regions of marked conformational variability among crystal structures (Fig. 4B, red). Outside of the helices, the isolated C-terminal B-chain β-strand in DKP-insulin (Fig. 4A, violet) correlates with the uniformity of this segment in crystal structures (Fig. 4B, blue); this uniformity is in part imposed by the dimer-related anti-parallel β-sheet (Fig. 4D). Discordance between SSP and crystallographic r.m.s.d. values is observed at the N-terminal B-chain segment, whose positioning in crystal structures is influenced by lattice packing. More marked reorganization of the N-terminal segment occurs in the TR transition (Fig. 4D) (62, 64), excluded from the present analysis.

Crystal structures also exhibit variability in residue-specific helical geometry. Whereas the above segment-specific r.m.s.d. values in principle reflect both local differences and global structural variation (i.e. rigid-body rotation or displacement of helices), a strictly local measure of variation is provided by main-chain (ϕ, ψ) dihedral angles. For any one residue, the collection of T state structures yields 13 (ϕ, ψ) values, permitting calculation of their mean values and standard deviation. A segment-specific measure of local conformational variability is provided by the average of the standard deviations (S.D.) for residues within a given helix. The corresponding values (S.D.ϕ and S.D.ψ) are 4.82° and 5.33° for the central B-chain α-helix, 6.41° and 8.31° for the C-terminal A-chain helix, and 8.96° and 9.95° for the N-terminal A-chain helix. This measure of (ϕ, ψ) variability thus yields the same rank order of conformational variability as segment-specific r.m.s.d. values (supplemental Table S2). A similar trend is observed among main-chain thermal B-factors of the T6 hexamer refined at a resolution of 1.9 Å: mean segmental values are 9.4 Å for the central B-chain α-helix, 15.2 Å for the C-terminal A-chain helix, and 19.8 Å for the N-terminal A-chain helix (27).

Conformational variability among crystal structures also affects rigid-body positioning of the A1–A8 α-helix and local main-chain conformations without disruption of main-chain hydrogen bonds or lengthening of key (i, i + 3) and (i, i + 4) inter-proton distances beyond the 5-Å cut-off for observable NOEs. Although such NOEs are retained in DKP-insulin, it is possible that the range of fluctuations in solution exceeds that seen among crystallographic protomers, thereby rationalizing rapid amide proton exchange in this segment. Helix-related hydrogen bonds are likewise maintained in the C-terminal A-chain segment despite its intermediate level of variability (25% attenuation of 13C-SSP score relative to the central B-chain α-helix).

SSP analysis of the insulin monomer is reminiscent of the partial folds of protein-folding intermediates (45). Unlike conventional ground states (supplemental Fig. S9A), such intermediates are characterized by broad free-energy landscapes. By analogy, we suggest that the ground-state ensemble of the insulin monomer likewise lacks structural specificity (supplemental Fig. S9B). Indeed, the segmental SSP scores of the three native-state helices are in accordance with the intrinsic helical propensities of their respective amino acid sequences as calculated by the Agadir algorithm (65). Because the A1–A8 sequence contains two internal β-branched residues (IleA2 and ValA3) and an unfavorable β-branched C-cap residue (ThrA8), its predicted helical propensity is low (0.06). As in SSP scores, the Agadir score of the C-terminal A-chain α-helix is intermediate (0.19) whereas that of the central B-chain α-helix is high (3.46). These intrinsic propensities reflect local sequence-dependent conformational biases in an unfolded polypeptide, which can be overridden in the native state (66). Although such scores have been used as a basis to optimize the thermodynamic stability of the native state (21, 67), the present correlation with SSP scores pertains to non-native conformational fluctuations. 13C NMR studies of the R6 insulin hexamer (supplemental Fig. S9C) by Led and co-workers (60) demonstrate that such assembly restores an α-helical pattern of A1–A8 Cα and Cβ chemical shifts, leading to canonical SSP scores (supplemental Fig. S9D and supplemental Table 2).

Insulin Fibrillation

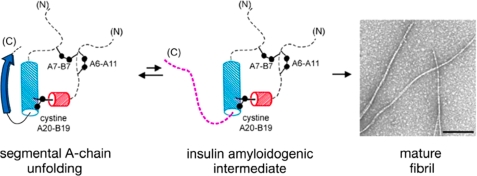

Insulin is susceptible to fibrillation, leading to formation of a cross-β-assembly analogous to pathological amyloids (1). Although long an issue in pharmaceutical applications, fibrillation is prevented in vivo by storage of insulin in the β-cell as microcrystalline zinc hexamers and by the short lifetime and low concentration of the susceptible monomer in the circulation (54). The majority of pharmaceutical formulations are likewise stabilized by zinc insulin assembly. Can our finding of segmental unfolding of the A-chain in the “native” insulin monomer (Fig. 10, left) point to another strategy to mitigate the risk of fibrillation? This question is of translational interest as mats of linear fibrils (Fig. 10, right) can occlude pumps and catheters used in the treatment of type 1 DM by continuous insulin infusion (25). Fibrillation is also the predominant mode of thermal degradation pertinent to the transport, storage, and use of insulin in the developing world.

FIGURE 10.

Proposed mechanism of fibrillation based on NMR studies. Segmental conformational fluctuation of the A1–A8 α-helix (left) leads to partial unfolding of native insulin to form an insulin amyloidogenic intermediate (center). Detachment of C-terminal B-chain β-strand (dashed purple line) may lead to putative amyloidogenic intermediate (center) (6) and formation of fibrils (EM photomicrograph; right). In the model of partial fold, cylinders indicate helical substructure (blue, residues B9–B19; and red, residues A16–A20). Dashed lines indicate disordered regions; disulfide bridges are indicated by black balls (sulfur atoms). Black bar (inset in EM photomicrograph) indicates 200 nm.

Fibrillation of globular proteins is mediated by aggregation of partially unfolded intermediates (68). In the case of insulin, a variety of evidence supports such a mechanism (6, 8, 69). Under classical amyloidogenic conditions (pH 2 and 60 °C) (9, 70), a novel partial fold (Fig. 10, center) has been observed by NMR in which the N-terminal segments of the A- and B-chains detach from the core; unfolding of the N-terminal α-helix of the A-chain exposes a hydrophobic surface formed by native-like packing of the remaining α-helices (6). The C-terminal segment of the B-chain, although not well ordered, remains tethered to this partial core (6). Segmental flexibility of the N-terminal A-chain segment, even under native conditions, suggests that its local unfolding facilitates formation of an amyloidogenic intermediate. Such unfolding would presumably be constrained in fibrillation-resistant but inactive single-chain insulin analogs in which a tether between residues B30 and A1 dampens conformational fluctuations and blocks fibrillation (7).13

Segmental unfolding of the N-terminal A-chain segment may contribute to formation of amyloid, either by itself mediating non-native aggregation or by exposing underlying nonpolar surfaces that do so. It is possible that direct and indirect mechanisms are each operative as both insulin chains participates in cross-β-assembly (present solid-state NMR results; see also Ref. 71), and each isolated chain is itself amyloidogenic (72). Although our studies focused on only three sites in each chain, the β-sheet-associated 13Cα and 13Cβ chemical shifts of ValA3, IleA10, and LeuA16 suggest an extensive α → β transition, including in part or in whole the A1–A8 segment. Enhancing the predicted helical propensity of this segment by replacement of its three native β-branched side chains reduces the stability of the insulin monomer (presumably via nonoptimal core packing involving LeuA2 and LeuA3) but protects the analog from fibrillation by a factor of 5 in lag time. Such protection is associated with a more α-helical pattern of 13Cα chemical shifts. This association was not significant in a less well protected A8 analog. Although our perspective focuses on conformational distortions in the native state, it is also possible that protective substitutions destabilize non-native oligomeric intermediates, the protofilament or mature fibril.

Although β-branched residues IleA2 and ValA3 are required for biological activity, optimization of the C-cap of the unstable A1–A8 α-helix can also delay fibrillation without loss of activity (Table 1). It is likely that the A8 modified α-helix is stabilized by removal of a β-branched residue, by favorable (i, i + 4) side-chain interactions with a GluA4, and by (in the case of LysA8) electrostatic compensation of the helical dipole. The lag time of the TrpA8 analog, intermediate between ThrA8 and HisA8 or LysA8, suggests the removal of the β-branch is itself advantageous in accordance with model peptide studies. Because patients with type 1 DM managed by continuous insulin infusion routinely replace the insulin in the pump reservoir every 3 days, this improvement may enhance the safety of such devices at summer temperatures. With current technology, external pumps exposed to direct sunlight (as can occur during summertime outdoor activities) can expose the insulin solution with the reservoir to temperatures significantly higher than ambient. Risk of occlusion leading to ketoacidosis can be magnified by delays in automated pump detectors of reduced flow (which can sound only after onset of hyperglycemia) and further exacerbated in childhood and adolescence if the unsupervised patient chooses to ignore or disable the alarm. The degree of protection from thermal fibrillation provided by A8-modified insulin analogs, although less marked than that of the “β-branchless” LeuA2,LeuA3,HisA8 biophysical model, may be sufficient to make existing pump alarm systems robust to the lifestyle demands of adolescence.

Although pump-based insulin therapy is a technology of affluent societies, a pandemic of DM is emerging in the developing world. Indigent populations are at risk in regions exposed to seasonal temperatures >35 °C and lacking consistent access to electricity and refrigeration. Mechanism-based studies of insulin fibrillation and further development of ultra-stable insulin analog formulations may be of humanitarian use in such regions.14

Concluding Remarks

This study is of both technical and mechanistic interest. Segment flexibility of an engineered insulin monomer highlights a limitation of conventional protocols for calculation of NMR structures. Such protocols ordinarily require that each model obey each restraint simultaneously. Reported solution structures of insulin and insulin analogs (including from this laboratory) thus exhibit three α-helices with similar apparent precisions (7, 31, 55). Such idealized ensembles are likely to underestimate conformational sampling. Newly described approaches to characterize the extent of fluctuations in proteins (73) may be informative. It would also be of interest to investigate whether motions in insulin are correlated and, if so, might provide a mechanism of allostery among crystallographic hexamers (26). The present results also suggest that further application of solid-state NMR methods to insulin fibrils would be feasible. In the future, systematic measurements of main-chain dihedral angles and distances between labeled sites could enable construction of a three-dimensional model.

The mechanism of fibrillation by disulfide cross-linked globular proteins poses an important general problem. Despite the broad biological utility of segmental flexibility in proteins, an associated breakdown in cooperativity may lead to an amyloidogenic partial fold (2). Segmental unfolding is likely to contribute to the exquisite susceptibility of insulin to fibrillation. The anomalous pattern of 13C NMR chemical shifts thus suggested a strategy to protect the monomer based on a general principle of peptide chemistry. We imagine that the likelihood of formation of an amyloidogenic nucleus is increased by segmental unfolding to enable non-native interactions by β-strand conformations. This model predicts that the risk of fibrillation would be decreased by optimization of intrinsic α-helical propensities (18–20) as demonstrated by the inactive [LeuA2,LeuA3,HisA8]DKP-insulin analog.

Application to clinical insulin analogs may prevent occlusion-related metabolic decompensation during continuous insulin infusion (25) and facilitate the transport, storage, and use of insulin in the developing world. Rapid-acting A8-modified insulin analogs thus exemplify the promise of foundational biophysics to enhance protein therapeutics. Comparative 13C NMR chemical shift mapping in the native state and in a fibril may provide a general method to identify amyloid-related “Achilles' heels” in globular proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Solid-state NMR measurements were supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIDDK, National Institutes of Health. We thank Drs. P. Carey, G. M. Clore, G. G. Dodson, R. Levy, D. F. Steiner, and B. Sykes for discussion; and we thank M. Choquette for technical assistance in generating the labeled DKP-proinsulin. M. A. W. thanks Drs. D. Jacobson (Case Western Reserve University Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences), M. R. Miah (Director, Southern Illinois University Carbondale School of Social Work), M. O. Rahman (Provost, Independent University of Bangladesh), and B. M. Chowdhury (Vice Chancellor, Independent University of Bangladesh) for sponsorship of a student-faculty trip to study poverty, micro-finance, and medical needs in the developing world.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK52085 (to R. B. M.) and DK079233, DK04949, and DK054662 (to M. A. W.). This work was also supported by Grant 0530067N from the American Heart Association (to Y. Y.) and a grant from the American Diabetes Association (to N. B. P.). This paper is a contribution from the Cleveland Center for Membrane and Structural Biology. M. A. W. has equity in and consults to Thermalin Diabetes, Inc. (Cleveland, OH).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Methods,” “Discussion,” Figs. S1–S9, Tables S1–S4, and additional references.

A striking exception to the general susceptibility of vertebrate insulins to fibrillation is provided by synthetic single-chain insulin analogs (“mini-proinsulins”), in which the C terminus of the B-chain is connected to the N terminus of the A-chain (1, 7). Such peptide tethers (0–3 residues) are compatible with native-like structure (75) but markedly impair receptor binding (76, 77). Such tethers may prevent conformational distortion of both the N-terminal A-chain α-helix and the C-terminal B-chain β-strand.

Rapid-acting insulin analogs, preferred for pump therapy in type 1 DM, are so named due to their accelerated absorption (relative to wild-type insulin) from a subcutaneous depot. Insulin aspart and insulin lispro are formulated as zinc insulin hexamers whose dimer interface is destabilized by mutations (78, 79), facilitating their rapid disassembly. In zinc-free monomers, the mutations are also destabilizing in terms of free energy of unfolding (see Table 1).

In 1H-15N HSQC spectra, the cross-peak of residue B7 is anomalously broad at both pH 7.8 and 7.1; cross-peaks of B8 and B21 are observable only at the lower pH values, whereas B9 is absent under either condition.

The crystallographic T → R transition, an allosteric reorganization of insulin hexamers (64, 80), is remarkable for a change in the secondary structure of the B1–B8 segment from extended (T state) to α-helix (R state). Segmental reorganization is coupled to changes in the conformation of GlyB8, core packing, and handedness of cystine A7–B7. The latter sulfur atoms are exposed in the T state but buried in a nonpolar crevice in the R state. The superscript Rf refers to N-terminal fraying of the B1–B19 α-helix. The T → R transition has been analyzed as a model for the long range transmission of conformational change (26).

Raising the temperature from 25 to 40 °C, which would be expected to accelerate amide proton exchange, leads to partial narrowing of A11 and B8 1HN resonances and their detectability in 1H-15N HSQC spectra.

I-J. Ye, K. Huang, Q. X. Hua, S. Q. Hu, and M. A. Weiss, manuscript in preparation.

Mutational and photocross-linking studies suggest that these conserved side chains contact the IR (81, 82). In classical structures, the C-terminal B-chain β-strand covers IleA2 and ValA3. Analogs containing allo-IleA2, in which the chirality of the β carbon is inverted (48), or LeuA3 exhibit native structure but low activity (83, 84). Destabilization of the B-chain β-strand by substitution of PheB24 by d-Phe enhances activity (85).

Although the HisA8 substitution was reported at pH 2 to promote fibrillation (9), this result does not exclude a protective effect at neutral pH. HisA8 is observed in the insulins in a variety of birds, fish, and reptiles, whereas LysA8 occurs in the platypus (86).

The A1–B30 tether in mini-proinsulins would hinder both direct and indirect contributions of segmental unfolding of the N-terminal A-chain segment to such aggregation (7).

While this manuscript was in review, one of the authors (M. A. W.) had the opportunity to visit the rural poor of Bangladesh under the auspices of the Independent University of Bangladesh and with the encouragement of Prof. Muhammad Yunus, recipient of the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize for pioneering programs of micro-finance as a mechanism of poverty alleviation (87). In Bangladesh as in other regions of the developing world, many villages may share a single refrigerator, hindering operation of a therapeutic cold chain. The A8 modifications described here may provide a design element in construction of ultra-stable single-chain insulin analogs (88).

- DM

- diabetes mellitus

- CSI

- chemical shift index

- DKP-insulin

- insulin analog containing three substitutions in B-chain (AspB10, LysB28, and ProB29)

- KP-insulin

- KP-insulin contains the substitutions ProB28 to Lys and LysB29 to Pro

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single-quantum coherence

- IGFR

- insulin-like growth factor receptor

- IR

- insulin receptor

- MAS

- magic-angle spinning

- NOE

- nuclear Overhauser enhancements

- NOESY

- NOE spectroscopy

- r.m.s.d.

- root-mean-square deviation

- rp-HPLC

- reverse-phase HPLC

- ThT

- thioflavin T

- TOCSY

- total correlation spectroscopy

- SSP

- secondary structural propensities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brange J., Andersen L., Laursen E. D., Meyn G., Rasmussen E. (1997) J. Pharm. Sci. 86, 517–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobson C. M. (2003) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2, 154–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brange J. (1987) Galenics of Insulin: The Physicochemical and Pharmaceutical Aspects of Insulin and Insulin Preparations, pp. 52–68, Springer-Verlag, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss M. A., Hua Q. X., Lynch C. S., Frank B. H., Shoelson S. E. (1991) Biochemistry 30, 7373–7389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hua Q. X., Xu B., Huang K., Hu S. Q., Nakagawa S., Jia W., Wang S., Whittaker J., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14586–14596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hua Q. X., Weiss M. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 21449–21460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang K., Dong J., Phillips N. B., Carey P. R., Weiss M. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42345–42355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmad A., Millett I. S., Doniach S., Uversky V. N., Fink A. L. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 11404–11416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen L., Frokjaer S., Brange J., Uversky V. N., Fink A. L. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 8397–8409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wishart D. S., Sykes B. D., Richards F. M. (1992) Biochemistry 31, 1647–1651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wishart D. S., Sykes B. D. (1994) J. Biomol. NMR 4, 171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hua Q. X., Shoelson S. E., Kochoyan M., Weiss M. A. (1991) Nature 354, 238–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishna M. M., Hoang L., Lin Y., Englander S. W. (2004) Methods 34, 51–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petkova A. T., Ishii Y., Balbach J. J., Antzutkin O. N., Leapman R. D., Delaglio F., Tycko R. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 16742–16747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu N. T., Jo B. H., Chang R. C., Huber J. D. (1974) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 160, 614–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouchard M., Zurdo J., Nettleton E. J., Dobson C. M., Robinson C. V. (2000) Protein Sci. 9, 1960–1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong J., Wan Z., Popov M., Carey P. R., Weiss M. A. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 330, 431–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Neil K. T., DeGrado W. F. (1990) Science 250, 646–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakrabartty A., Doig A. J., Baldwin R. L. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 11332–11336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doig A. J., Baldwin R. L. (1995) Protein Sci. 4, 1325–1336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss M. A., Wan Z., Zhao M., Chu Y. C., Nakagawa S. H., Burke G. T., Jia W., Hellmich R., Katsoyannis P. G. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 315, 103–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demirdjian S., Bardin C., Savin S., Zirinis P., Chast F., Slama G., Sélam J. L. (1998) Diabetes Care 21, 867–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mudaliar S. R., Lindberg F. A., Joyce M., Beerdsen P., Strange P., Lin A., Henry R. R. (1999) Diabetes Care 22, 1501–1506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bode B. W., Strange P. (2001) Diabetes Care 24, 69–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolpert H. A., Faradji R. N., Bonner-Weir S., Lipes M. A. (2002) British Medical Journal 324, 1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chothia C., Lesk A. M., Dodson G. G., Hodgkin D. C. (1983) Nature 302, 500–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker E. N., Blundell T. L., Cutfield J. F., Cutfield S. M., Dodson E. J., Dodson G. G., Hodgkin D. M., Hubbard R. E., Isaacs N. W., Reynolds C. D. (1988) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 319, 369–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bode B. W., Sabbah H. T., Gross T. M., Fredrickson L. P., Davidson P. C. (2002) Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 18, S14–S20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackin R. B., Choquette M. H. (2003) Protein Expr. Purif. 27, 210–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hua Q. X., Liu M., Hu S. Q., Jia W., Arvan P., Weiss M. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 24889–24899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hua Q. X., Hu S. Q., Frank B. H., Jia W., Chu Y. C., Wang S. H., Burke G. T., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 264, 390–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marsh J. A., Singh V. K., Jia Z., Forman-Kay J. D. (2006) Protein Sci. 15, 2795–2804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicholls A., Bharadwaj R., Honig B. (1993) Biophys. J. 64, A166 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balbach J. J., Ishii Y., Antzutkin O. N., Leapman R. D., Rizzo N. W., Dyda F., Reed J., Tycko R. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 13748–13759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishii Y. (2001) J. Chem. Phys. 114, 8473–8483 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bennett A. E., Rienstra C. M., Griffiths J. M., Zhen W. G., Lansbury P. T., Griffin R. G. (1998) J. Chem. Phys. 108, 9463–9479 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bennett A. E., Rienstra C. M., Auger M., Lakshmi K. V., Griffin R. G. (1995) J. Chem. Phys. 103, 6951–6958 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paravastu A. K., Leapman R. D., Yau W. M., Tycko R. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 18349–18354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wishart D. S., Bigam C. G., Holm A., Hodges R. S., Sykes B. D. (1995) J. Biomol. NMR 5, 67–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whittaker J., Whittaker L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 20932–20936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whittaker J., Groth A. V., Mynarcik D. C., Pluzek L., Gadsbøll V. L., Whittaker L. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 43980–43986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Z. X. (1995) FEBS Lett. 360, 111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saker F., Ybarra J., Leahy P., Hanson R. W., Kalhan S. C., Ismail-Beigi F. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. 274, E984–E991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hua Q. X., Ladbury J. E., Weiss M. A. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 1433–1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hua Q. X., Nakagawa S. H., Jia W., Hu S. Q., Chu Y. C., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 12299–12311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hua Q. X., Weiss M. A. (1991) Biochemistry 30, 5505–5515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakagawa S. H., Tager H. S. (1992) Biochemistry 31, 3204–3214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wan Z., Xu B., Huang K., Chu Y. C., Li B., Nakagawa S. H., Qu Y., Hu S. Q., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 16119–16133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holleman F., Hoekstra J. B. (1997) N. Engl. J. Med. 337, 176–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Renner R., Pfützner A., Trautmann M., Harzer O., Sauter K., Landgraf R. (1999) Diabetes Care 22, 784–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Radermecker R. P., Scheen A. J. (2004) Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 20, 178–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brange J., Langkjaer L. (1997) Pharm. Biotechnol. 10, 343–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dodson G., Steiner D. (1998) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8, 189–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olsen H. B., Ludvigsen S., Kaarsholm N. C. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 8836–8845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dumoulin M., Canet D., Last A. M., Pardon E., Archer D. B., Muyldermans S., Wyns L., Matagne A., Robinson C. V., Redfield C., Dobson C. M. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 346, 773–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pocker Y., Biswas S. B. (1980) Biochemistry 19, 5043–5049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]