Abstract

Head-to-head assembly of two spectrin heterodimers to form an actin-cross-linking tetramer is a physiologically dynamic interaction that contributes to red cell membrane integrity. Recombinant β-spectrin C-terminal and α-spectrin N-terminal peptides can form tetramer-like univalent complexes, but they cannot evaluate effects of the open-closed dimer interactions or lateral associations of the two-spectrin strands on tetramer formation. In this study we produced and characterized a fused “mini-spectrin dimer” containing the β-spectrin C-terminal region linked to the α-spectrin N-terminal region. This fused mini-spectrin mimics structural and functional properties of intact, full-length dimers and tetramers, including lateral association of the α and β subunits in the dimer and formation of a closed dimer. High performance liquid chromatography gel filtration analyses of this mini-spectrin provide the first direct non-imaging experimental evidence for open and closed spectrin dimers and show that dimer-tetramer-oligomer interconversion is slow at low temperatures and accelerated at 30 °C, analogous to full-length spectrin. This protein exhibits wild type dimer-tetramer dissociation constants of ∼1 μm at 30 °C, independent of initial oligomeric state. Conformational states of the mini-spectrin dimer were probed further using chemical cross-linking, which identified distinct groups of cross-links for “open” and “closed” dimers and confirmed the N-terminal region of α-spectrin remains highly flexible in the complex, exhibiting closely analogous structures to those observed for the isolated α-spectrin N-terminal using NMR (Park, S., Caffrey, M. S., Johnson, M. E., and Fung, L. W. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 21837–21844). This fusion protein should serve as a useful template for structural and functional studies of the divalent tetramer site.

Keywords: Cytoskeleton, Erythrocyte, Membrane Proteins, Molecular Dynamics, Plasma Membrane, Protein Assembly, Protein Conformation, Protein Cross-linking, Protein Self-Assembly, Spectrin

Introduction

Erythrocyte spectrin is a major component of the red cell membrane cytoskeleton, a two-dimensional latticework of proteins associated with the cytoplasmic face of the red cell membrane. This protein network maintains the red cell biconcave shape and simultaneously provides the elasticity and deformability that is required as red blood cells travel through the capillaries of the splenic microcirculation. The membrane skeleton consists of spectrin tetramers that cross-link complexes containing short actin oligomers, protein 4.1R, adducin, band 4.9, tropomyosin, tropomodulin, p55, and other proteins. The membrane skeleton is attached to the lipid bilayer through two major linkage sites, namely, a β-spectrin/ankyrin/band 3 attachment site near the spectrin tetramer region (1, 2) and the spectrin-actin complex, which has multiple linkages to transmembrane proteins that include glycophorin and the glucose transporter (3, 4). In addition to providing structural support to the cell membrane, spectrin more recently has been shown to promote the assembly of specialized membrane domains both in erythrocytes and other cell types (5). The ability of spectrin to cluster these membrane domains highlights the importance in understanding the spectrin tetramerization process. The properties of this protein have recently been reviewed (5).

Spectrin is a heterodimer comprised of a 280-kDa α- and 246-kDa β-chain, and two heterodimers associate in a head-to-head orientation to form an actin cross-linking tetramer. The majority of the spectrin dimer is composed of many tandem homologous arrays of ∼106 amino acids, 3-helix-bundle domains commonly referred to as spectrin-type motifs or repeats (6). Previous studies have shown that formation of antiparallel spectrin heterodimers is a rapid process that requires the presence of a dimer nucleation or initiation site, specifically the last two repeats of α spectrin and the first two spectrin-type repeats of β spectrin (7, 8). These early studies showed that any spectrin fragments that contained both α20–21 and β1–2 could associate with high affinity; however, fragments that lacked this critical site could not laterally assemble. The “zipper” model of spectrin assembly includes this initial rapid, high affinity binding at the dimer nucleation site followed by rapid, low affinity lateral associations along the length of the spectrin dimer and, finally, locking of the zipper by formation of a moderate affinity, closed-dimer structure where the longer α-subunit flips back upon itself and binds head-to-head with the β17 repeat (7, 9). Spectrin dimers can further associate head to head to predominately form tetramers, although higher order oligomers can occur, especially in solutions at high spectrin concentrations (10). The tetramer binding site involves a partial repeat near the N terminus of α-spectrin (α0) and a partial repeat (β17) near the C terminus of β-spectrin (Fig. 1) (7, 9, 11).

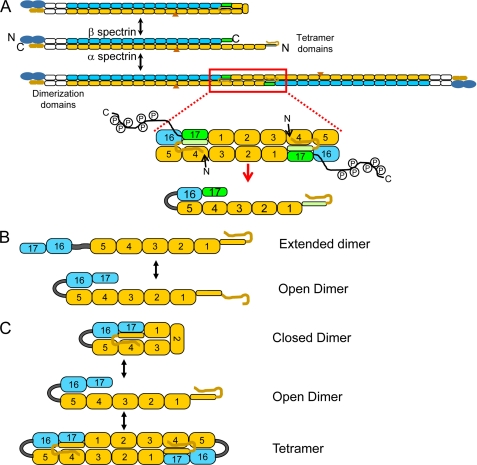

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the interconversion between spectrin dimers and tetramers and the related fused mini-spectrin dimer. A, the equilibrium between spectrin dimers and tetramers involves opening the closed spectrin dimer followed by head-to-head association of two open spectrin dimers to form a tetramer. The repetitive spectrin-type domains are shown as rounded rectangles, with the β chain in blue, and the α chain in yellow. The domains necessary for initiating spectrin heterodimer formation are shown in white, and the complementary partial domains involved in tetramer formation are shown in green. The large blue ovals represent the actin binding domain at the N terminus of β spectrin, and the yellow hexagons represent the C-terminal EF hands of α spectrin. The orange triangle is traditionally referred to as the 10th motif of α spectrin but is actually an SH-3 type motif inserted into the BC loop of helix 9 of α spectrin. The region of the spectrin tetramer that was used to create the mini-spectrin tetramer is outlined in red and shown in greater detail including the relative location of the phosphorylated C-terminal domain of β spectrin. The actual domains used to create the construct for this study, which do not include the protease-sensitive non-homologous β spectrin C-terminal tail, are indicated below the red arrow. The β16–17 and α0–5 repeats are tethered together by a short linker comprised of the sequence GGGGGGIEGRGGGGGG, represented by an arc in the diagram. B, shown are two major possible conformations that the mini-spectrin tetramers could adopt, depending upon the capacity to form lateral α and β associations. C, shown is a schematic representation of the interconversion of the mini-spectrin dimer from closed dimer to open dimer to tetramer.

The spectrin dimer-tetramer equilibrium is of critical importance for maintaining red blood cell stability. It has been hypothesized that the moderate affinity tetramer interaction (12, 13) enables dynamic rearrangements of the membrane cytoskeleton when red cells are deformed due to shear stress through a “breathing” action of spectrin tetramer dissociation/re-association (14). Although the dimer-tetramer interaction has been extensively studied using sedimentation equilibrium as well as other methods, the roles of open and closed dimers in spectrin tetramer assembly and membrane stability are poorly understood. Opening of the closed dimer is an obligatory intermediate in conversion of closed dimers to tetramers, and this closed-open transition has a high energy of activation that is responsible for “freezing” of the dimer-tetramer interconversion at low temperatures (7). That is, intact spectrin dimers or tetramers at non-equilibrium concentrations interconvert very slowly below room temperature, whereas equilibrium is typically reached within 30–45 min at 37 °C. Although electron micrograph images indicative of open and closed spectrin dimers have been observed, their roles in spectrin assembly are poorly defined because direct biochemical methods for detecting and quantifying open and closed spectrin dimers have not existed. For example, sedimentation equilibrium studies, which have been used most extensively to study the dimer-tetramer equilibrium, measure the aggregate pool of closed and open dimers as a single species.

Most cases of hereditary elliptocytosis and hereditary pyropoikilocytosis involve defects in spectrin tetramer formation, and in many cases the mutations responsible for the disorder are single amino acid mutations located directly within the tetramer binding site. We recently showed that most hereditary elliptocytosis/hereditary pyropoikilocytosis mutations located in the α0 domain exhibited either decreased tetramer assembly or no detectable tetramer formation when a tetramer binding assay involving formation of univalent head-to-head complexes was used (15). Interestingly, two α0 mutants exhibited wild type binding, which suggested that these mutations might destabilize tetramer formation by perturbing interstrand interactions in divalent tetramers. In addition to point mutations located directly in the tetramer binding site, a number of common hereditary elliptocytosis/hereditary pyropoikilocytosis mutations are located at distal sites that are, in some cases, several hundred angstroms from the tetramer binding site. Preliminary studies assaying univalent tetramer binding between recombinant α0–5 and wild type β16–17 exhibited wild type binding affinity for a number of distal mutations located in the α0–5 recombinant protein. This suggests that these distal mutations destabilize the spectrin membrane skeleton by an alternative mechanism such as perturbing the closed-open dimer equilibrium, affecting interstrand lateral interactions in the tetramer site region, or affecting another property of tetramer formation that cannot be measured using the univalent tetramer binding assay.

In this study we expressed and evaluated a mini-spectrin recombinant protein as a potential template for further investigating the effects of distal mutations on the α-subunit hairpin loop and the associated closed-open dimer equilibrium. This mini-spectrin also was used to evaluate structural and functional properties of the weak lateral associations between strands in the tetramer binding site region. The fused dimer was designed to retain the normal lateral register between subunits, and because the dimer initiation site was deleted, a flexible glycine linker was used to determine whether sequestering the α and β chains in close proximity would be sufficient to enable the weak lateral association between subunits. Although this fusion protein is technically a monomer (single polypeptide chain), we will refer to it as a mini-spectrin “dimer” and head-to-head complexes as “tetramers,” as they recapitulate structures equivalent to truncated spectrin dimers and tetramers. This mini-spectrin dimer is well folded, forms predicted lateral associations, and closely mimics the dimer-tetramer equilibrium of full-length spectrin. It enables the first, direct, biochemical detection of the open and closed dimer states and should serve as a useful template for future studies that will explore the effects of distal mutations on the closed-open dimer equilibrium and destabilization of spectrin complexes in the red cell membrane.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construction and Expression of the Mini-spectrin Expression Plasmid

The following fused α-β mini-spectrin recombinant protein was constructed for use in this study: α0–5 (repeats 0–5 of the human red cell α-spectrin subunit, residues 1–584) followed by a flexible glycine linker with a factor Xa cleavage site inserted in the middle consisting of the sequence GGGGGGIEGRGGGGGG followed by β16–17 (repeats 16 and 17 of the human red cell β-spectrin subunit, residues 1902–2080). The boundaries for the repeats are based on the structural phasing of the first available spectrin crystal structure described by Yan et al. (16). The fused α-β spectrin gene was inserted into a pGEX-2T expression plasmid using the BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites using standard molecular biology techniques (17). In addition to the wild type protein, site-directed mutagenesis was used to introduce the R28S mutation into the C helix of α0. The plasmids were transformed into the BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL strain of Escherichia coli (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) for protein expression.

Expression and purification of wild type and mutant protein followed identical protocols. The glutathione S-transferase mini-spectrin fusion protein was expressed at 18 °C and purified from the soluble fraction after cell lysis using established methods (18). After initial purification on a glutathione-Sepharose column, the mini-spectrin was cleaved from the glutathione S-transferase moiety using bovine thrombin (Sigma) at an enzyme-to-substrate ratio of 12 units of enzyme/mg of protein with incubation for 3 h at 37 °C. NaCl was added to a final concentration of 0.5 m to decrease the formation of secondary cleavage products. After enzyme inactivation with PMSF,3 the sample was concentrated and purified by HPLC gel filtration on a HiLoad 200 column (GE Healthcare) in 10 mm sodium phosphate, 130 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.15 mm PMSF, 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.4.

Analytical Gel Filtration

Mini-spectrin oligomers, tetramers, open dimers, and closed dimers were evaluated using analytical gel filtration using two BioAssist G4000SWXL (Tosoh Corp., Tokyo, Japan) columns connected in series, equilibrated in 20 mm sodium phosphate, 130 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.15 mm PMSF, 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol pH 7.4. Analysis was performed in either a refrigerated chromatography cabinet maintained at 4 °C using a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min or at ambient temperature using a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. Detection of protein was by absorbance at 280 nm.

Sedimentation Equilibrium

Mini-spectrin oligomers, tetramers, or dimers were analyzed using sedimentation equilibrium in a Beckman XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge. The samples were isolated by gel filtration chromatography using two BioAssist G4000SWXL columns connected in series equilibrated in 20 mm Tris, 130 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.15 mm PMSF, 1 mm Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, pH 7.4, and maintained at 4 °C. For the oligomer and tetramer forms, samples were concentrated using an Amicon Ultra concentration device (Millipore™ Corp., Bellerica, MA) immediately before gel filtration. Fractions corresponding to the mini-spectrin oligomer or tetramer were used for analysis. Isolation of the dimer required dilution of the sample to 0.05 mg/ml and heating at 37 °C for 1 h followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C. The sample was then concentrated to a moderate volume using an Amicon Ultra concentration device (Millipore™) immediately before gel filtration. A fraction corresponding to the mini-spectrin closed dimer was used for analysis. The loading cells were assembled with 12-mm Epon double sector Yphantis-style centerpieces and sapphire windows. All sample volumes were 110 μl, and interference optics were used for data collection. A minimum of three different initial loading concentrations was used for each experiment. Experiments were performed at 30 °C using multiple rotor speeds. Fringe displacement data were collected every 4 h until equilibrium was attained as determined from comparison of successive scans using the WinMATCH Version 0.99 program.4 Before each run, a blank scan with distilled water was taken to correct for window distortion on the fringe displacement data (19). Data were edited using the WinREED v0.999 program.4 Sedimentation equilibrium data were analyzed using the WinNONLIN Version 1.06 program (20). The reduced molecular weight of the protein was defined as σ = Mr(1 − v̄ρ)ω2/RT, where Mr is the sequence molecular weight, v̄ is the partial specific volume of the protein, ρ is the solvent density, ω is the angular velocity in radians/s, R is the gas constant, and T is the temperature in Kelvin. The program SEDNTERP v1.09 was used to calculate Mr and v̄ from the amino acid composition of the mini-spectrin recombinant protein and ρ for the solvent. Data from a minimum of three different initial loading concentrations were fitted simultaneously. The data were fitted well by a “dimer-tetramer” model of association. Examination of residuals and minimization of the variance were used to determine goodness of fit. The dimer-tetramer association constants returned by WinNONLIN were converted to the molar scale using the sequence molecular weight of the protein and a specific fringe displacement of 3.26 fringes for each gram/liter of protein (21).

Cross-linking Reactions

Cross-linking reactions using 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC)/sulfo-N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (sulfo-NHS) were performed using 5 μl of a freshly prepared aqueous cross-linker solution added to 300 μl of mini-spectrin dimer (0.38 mg/ml) in phosphate-buffered saline. The final concentrations of EDC and sulfo-NHS were 10 and 5 mm, respectively. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 4 °C, and 100-μl aliquots were removed after 1, 2, and 4 h. The reactions were quenched by the addition of 20 mm dithiothreitol (final concentration). Before SDS-PAGE, the solutions were concentrated using a Microcon YM-10 filter unit (Millipore™).

SDS-PAGE and Trypsin Digestion

The cross-linked samples were separated using a 3–8% Tris acetate mini-gel (Invitrogen), and the gel was stained with colloidal Coomassie Blue. The cross-linked dimer band was excised and digested using modified trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) as described previously (22).

Liquid Chromatography and Tandem Mass Spectrometry

The locations of cross-linked residues were determined by LC-MS/MS on a hybrid linear quadrupole ion trap/FT-ICR (LTQ-FT Ultra™) mass spectrometer (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) equipped with a NanoLC pump and autosampler (Eksigent Technologies, Livermore, CA). Tryptic peptides were separated by reverse phase-HPLC on a nanocapillary column, 75-μm inner diameter × 15 cm PicoFrit® (New Objective, Woburn, MA), packed with MAGIC C18 resin, 5-μm particle size (Michrom Bioresources, Auburn, CA). Solvent A was 0.1% formic acid in Milli-Q® (Millipore™) water, and solvent B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. Peptides were eluted at 200 nl/min using an acetonitrile gradient consisting of 3–28% B over 42 min, 28–50% B over 26 min, 50–80% B over 5 min, and 80% B for 5 min before returning to 3% B in 1 min. To minimize sample carryover to the next LC-MS/MS run, a blank HPLC gradient was run between each sample. The LTQ-FT Ultra mass spectrometer was set to perform a full MS scan (m/z 400–2000) in the FT-ICR cell. The resolution at 400 m/z was set to 1 × 105 for the MS scan, and the six most intense ions exceeding a minimum threshold of 800 were selected for MS/MS in the linear trap using an isolation width of 2.5 Da. The monoisotopic precursor selection was disabled, and singly charged ions were excluded from MS/MS analysis. Ions subjected to MS/MS were excluded from repeated analysis for 45 s.

Identification of Cross-linked Peptides

Cross-linked mini-spectrin dimer peptides were identified using Elucidator software (Rosetta Biosoftware, Seattle, WA). This software compares LC/MS patterns of cross-linked samples versus uncross-linked control samples to identify possible ions associated with peptides generated after sample treatment with EDC/sulfo-NHS. The MH+ values for features with a charge >2 and specific to the cross-linked sample were compared with a list of theoretical MH+ values for all theoretical cross-linked peptides, which were calculated using the software package GPMAW (General Protein Mass Analysis for Windows) software, Version 7.10 (Lighthouse Data, Odense, Denmark). The ions that were specific to the cross-linked samples and were within 2 ppm of the theoretical cross-linked peptide were selected for further analysis. The Fuzzy Ions program (Thermo-Fisher, Pittsburg, PA) combined with manual de novo sequencing were used to identify the cross-linked peptides and the amino acid residues involved in forming the cross-link.

RESULTS

Design and Expression of a Mini-spectrin Molecule

Fig. 1A shows a model of human red cell spectrin in its closed dimer, open dimer, and tetramer forms and the dynamic equilibrium between the two dimer states and tetramers. The minimum region required to recapitulate the divalent head-to-head interaction is composed of repeats α0–5 and β16–17 as highlighted by the red box. Because lateral association of the α and β chains is normally driven by unique spectrin repeats in the dimer initiation site at the other end of the molecule, we tested the feasibility of forming the predicted lateral interactions between the α5 and β16 repeats by connecting the two chains via a short tether. The length of the linker, which consisted of 12 Gly residues and an internal factor X cleavage site (see “Experimental Procedures”), was intended to provide flexibility to allow correct lateral pairing of the α and β repeats while still restraining motifs that should laterally associate in close proximity.

The mini-spectrin was expressed and purified as a glutathione S-transferase fusion protein; the tag was removed with thrombin, and the protein was further purified to homogeneity by gel filtration. The final product yield was ∼ 5.5 mg/liter of bacterial culture. The protein was ≥95% pure based on Coomassie Blue staining of SDS-PAGE gels and migrated consistent with the calculated molecular mass of 90,432 Da (Fig. 2D). Circular dichroism results showed the mini-spectrin tetramer contained 87% α-helix (supplemental Fig. 1), which is in good agreement with the α-helix content of its component parts and those reported for other spectrin recombinant proteins (23, 24).

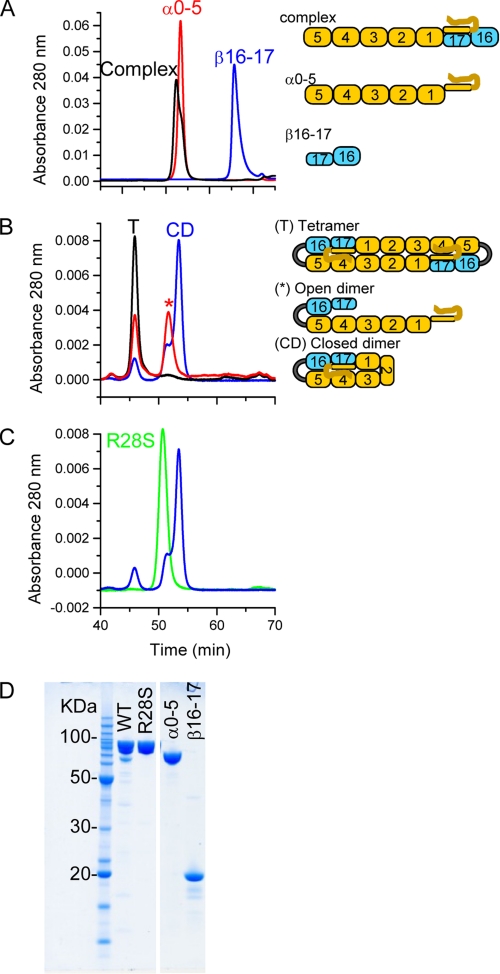

FIGURE 2.

HPLC gel filtration analysis of mini-spectrin. A, the elution profiles of recombinant α0–5 (red), β16–17 (blue), and a complex of α0–5/β16–17 (black) are shown. Schematic representations of the constructs are shown for comparison. B, the elution profiles of the mini-spectrin sample under different conditions are the mini-spectrin dimer fraction isolated at 4 °C and rerun on the gel filtration columns at 4 °C (blue), the mini-spectrin tetramer fraction isolated then rerun on the gel filtration columns at 4 °C (black), and the mini-spectrin dimer fraction rerun at room temperature after incubation at 30 °C (red). The proposed conformation of each eluted peak is indicated by T (tetramer), * (open dimer), and CD (closed dimer) and are shown schematically. C, the elution profile of the mini-spectrin R28S mutant is shown in comparison to the mini-spectrin dimer shown in B. D, SDS-PAGE gel of the purified recombinant spectrin samples were separated by SDS-PAGE using a 10% Bis-Tris mini-gel (Invitrogen) and stained with colloidal Coomassie Blue. Selected molecular weight markers are indicated. WT, wild type.

Initial analysis by analytical gel filtration showed that the mini-spectrin eluted in discreet peaks and did not form long linear polymers. This was an important observation because it was predicted that the fused mini-spectrin would adopt one of two conformations as illustrated in Fig. 1B or a combination of both based upon the extent of lateral interaction between α5 and β16 and possibly between α4 and β17 (depending upon which specific helices dock laterally in these repeats). The extended and open dimer conformations are easily distinguished because the extended dimer would be capable of forming long linear polymers, as functional tetramer binding sites would be present at opposite ends of the molecule. Because no polymerization was detected by either HPLC gel filtration or sedimentation equilibrium analysis (see below), this indicated that the fused dimer did not exist in the extended dimer form at detectable levels, and lateral associations occurred between the α-subunit and β-subunit portions of the fused dimer. Furthermore, the resulting open dimer should be capable of interconversion between open dimers and closed dimers as well as between open dimers and tetramers as shown in Fig. 1C.

Hydrodynamic Properties of Mini-spectrin

Gel filtration was used to determine the Stokes radius of the mini-spectrin and other recombinant spectrin proteins. The columns were calibrated using proteins with known Stokes radii. Subsequently, individual recombinant spectrin proteins comprised of various numbers of repeats were evaluated. A linear relationship was observed between the number of spectrin repeats and the measured Stokes radii. In addition to individual recombinant proteins, complexes of 2- or 4-repeat spectrin proteins were used to evaluate the Stokes radii of laterally associated dimeric complexes. A linear relationship was also observed for lateral dimers (see supplemental Fig. 2). A representative elution profile for spectrin recombinants α0–5, β16–17, and equimolar amounts of α0–5 and β16–17 are shown in Fig. 2A. The univalent head-to-head complex formed between α0–5 and β16–17 shows a modest increase in Stokes radius (64 Å) relative to the α0–5 recombinant (59 Å), as expected for a modest extension of molecular length.

Representative gel filtration results for the mini-spectrin construct are shown in Fig. 2B. After purification, concentration, and storage at 4 °C, the mini-spectrin protein elutes in a position most consistent with tetramer based on correlation with the Stokes radii of other spectrin recombinants of varying lengths (see supplemental Fig. 2). Upon heating to either 30 or 37 °C for 1 h, the mini-spectrin protein eluted in 2 peaks corresponding to the tetramer (101 Å) and dimer (56 Å) fractions. A fraction corresponding to the mini-spectrin dimer was reinjected onto the gel filtration columns. The predominant species in this fraction was the closed dimer and a small amount of open dimer (65 Å) and tetramer (see Fig. 2B). If the sample was stored at 4 °C and injected onto a column equilibrated at room temperature, approximately equal amounts of tetramer and open dimer were observed (see Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the mini-spectrin R28S mutant elutes as a single peak consistent with an open dimer (see Fig. 2C).

Analysis of Dimer-Tetramer Interconversion Using Analytical Gel Filtration

Fractions corresponding to mini-spectrin oligomers, tetramers, and closed dimers were isolated by preparative gel filtration at 4 °C. Each individual oligomeric species was then diluted to a concentration of 0.2, 0.05, or 0.02 mg/ml and stored at 0 °C. 100 pmol of each sample was then injected onto the gel filtration columns at various time points over a period of several weeks. Fig. 3A shows that the tetramer fraction is stable and remains tetramer at this concentration, indicating very tight association at 0 °C. The closed dimer fraction, shown in Fig. 3B, slowly converts to tetramer over a period of many weeks. The oligomer fraction also slowly interconverts to the tetramer form (data not shown). This behavior for all oligomer states is qualitatively analogous to the observed very slow interconversion of full-length spectrin dimers and tetramers at 0–4 °C. Only the 0.05 mg/ml concentration data are shown in Fig. 3. At higher concentrations, the conversion of closed dimers to tetramer occurs more rapidly, and conversely, at lower protein concentration the rate of interconversion between dimers and tetramers is slowed.

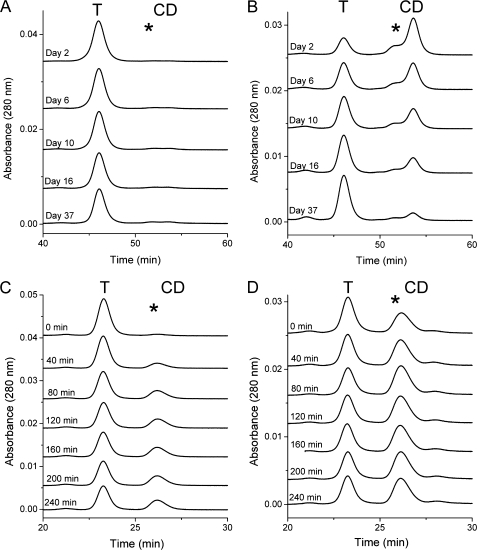

FIGURE 3.

Kinetics of interconversion of mini-spectrin dimers and tetramers. For all samples, 100 pmol at a concentration of 0.05 mg/ml were injected onto the gel filtration columns. The relative positions of tetramer (T), open dimer (*), and closed dimer (CD) are indicated. A, tetramer was isolated and incubated at 4 °C and re-injected at indicated time points. B, dimer was isolated and incubated at 4 °C and re-injected at the indicated time points. C, tetramer was isolated at room temperature, heated to 30 °C, and re-injected at room temperature in 40-min intervals. D, dimer was isolated at room temperature, heated to 30 °C, and re-injected at room temperature in 40-min intervals.

A similar oligomer state interconversion time course experiment was performed at 30 °C. In this case, fractions corresponding to oligomers, tetramers, or open dimers were isolated at room temperature and diluted to a concentration of 0.05 or 0.02 mg/ml, 100 pmol was immediately injected onto the gel filtration columns, and the remaining sample was incubated at 30 °C before injecting 100-pmol aliquots onto the gel filtration columns at 40-min intervals. The tetramer and dimer fractions reached equilibrium within ∼80 min (Fig. 3, C and D) at 0.05 mg/ml, although the relative ratios in dimer/tetramer were somewhat different depending upon the initial fraction used. Interestingly, the form of the dimer observed at 30 °C was primarily the open form. As expected, the lower concentration of protein resulted in slightly slower kinetics and an increased proportion of dimer relative to tetramer.

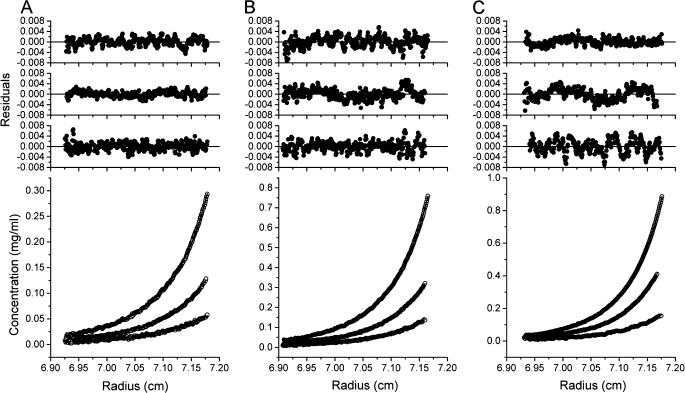

Analysis of Dimer-Tetramer Equilibrium Using Sedimentation Equilibrium

Mini-spectrin oligomers, tetramers, and dimers were isolated by gel filtration chromatography. Each of these samples was then analyzed by sedimentation equilibrium using a minimum of three different initial loading concentrations and speeds of 9,800, 13,800, and 19,500 rpm at 30 °C. In all cases, the data could be fit well by a spectrin dimer-tetramer model, enabling an estimation of the dissociation constant to be 1 μm. Results for a single experiment for each initial oligomeric state are shown in Fig. 4, and Table 1 lists the average value for several experiments. Analysis of the mini-spectrin R28S mutant shows only a single species consistent with the molecular weight of a dimer (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Sedimentation equilibrium analysis of mini-spectrin. Isolated fractions from gel filtration chromatography corresponding to mini-spectrin oligomer, tetramer, or dimer were subjected to sedimentation equilibrium. Samples at three different initial loading concentrations were run in 20 mm Tris, 130 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.15 mm PMSF, 1 mm Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, pH 7.4, at 4 °C and 13,000 RPM. A, isolated oligomer at starting concentrations of 0.13, 0.065, and 0.033 mg/ml are shown. B, isolated tetramer at starting concentrations of 0.34, 0.17, and 0.085 mg/ml are shown. C, isolated dimer at starting concentrations of 0.28, 0.14, and 0.07 mg/ml are shown. Lower panels, raw data are indicated as circles, and a global fit corresponding to a dimer-tetramer model is indicated as lines. Upper panels, shown are the residuals of the fitted curve to the data points from highest to lowest concentration, top to bottom, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Dimer-tetramer equilibrium as determined by sedimentation equilibrium

| Initial state | Speed | Temperature | Dimer-tetramer Kd | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpm | °C | μm | ||

| Oligomer | 13,000 | 30 | 1.1 ± 2.1 | 5 |

| Tetramer | 13,000 | 30 | 1.5 ± 4.2 | 5 |

| Dimer | 13,000 | 30 | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 6 |

Chemical Cross-linking of Mini-spectrin Dimer

The mini-spectrin dimer was isolated by gel filtration chromatography and cross-linked using the “zero-length” cross-linking reagent EDC/sulfo-NHS. In this reaction, amine groups (ϵ-amino group of Lys and the N terminus) create an amide bond with acid groups (Asp, Glu, and the C terminus) that are within close proximity. It was not possible to isolate pure populations of open and closed dimers in adequate yields for cross-linking experiments because the isolated fractions would establish new equilibria after isolation at both low and high temperatures. Hence, pools of the entire dimer region were used for cross-linking. After cross-linking, the sample was separated by SDS-PAGE (see supplemental Fig. 3), and the dimer band from the 1-h time point was excised from the gel, digested with trypsin, and analyzed on a hybrid linear quadrupole ion trap/FT-ICR (LTQ-FT Ultra) mass spectrometer.

Characterization of Intramolecular Cross-links Found in Mini-spectrin Dimers

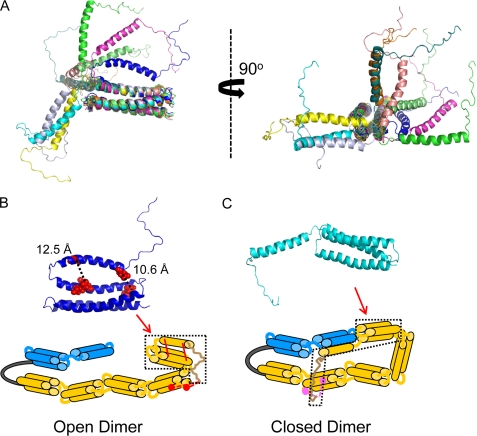

Use of a mass spectrometer with high mass accuracy (<2 ppm mass error) and the Elucidator program to compare MS patterns from LC-MS analyses of cross-linked and control samples reduced the number of MS/MS spectra that needed to be analyzed using manual de novo sequencing from greater than 2000 to less than 100 per run. The selected spectra identified six cross-linked peptides in the mini-spectrin dimer (Table 2). The MS/MS spectra and MS/MS assignments associated with each spectrum of the identified cross-linked peptides can be found in the supplemental materials (supplemental Tables 1–6 and supplemental Figs. 4–9). Four of the cross-linked peptides mapped to the N-terminal residue of α-spectrin. In addition, two cross-linked peptides were identified that cross-linked the helix in α0 to residues in the first complete repeat (α1). These cross-links are mapped onto schematic representations of closed and open mini-spectrin dimers in Fig. 5. As illustrated, the cross-links identified between the α0 and α1 repeats correlate closely with one of the structures observed in the NMR analysis (25) of the isolated α0–1 recombinant (Fig. 5B). Similarly, the capacity of the first residue of the α-subunit to cross-link to multiple residues is consistent with the extended flexible structure of the first 15 residues indicated in the NMR structure. Two of the cross-links involving the N-terminal residue are consistent with an open dimer, whereas the other two cross-links are only consistent with a closed dimer (Fig. 5).

TABLE 2.

Cross-links that support open or closed mini-spectrin dimers

*, cross-linked residue (multiple labeled residues in a single peptide indicate ambiguous assignment). #, methionine oxidation; @, cysteine carboxyamidomethylation.

| Cross-links | MH+ | m/z | Charge | Mass error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ppm | ||||

| Cross-links that support an open dimer conformation | ||||

| DAD*D*LGK ↔ YQSFK*ER | 1671.7984 | 557.9376 | 3 | 0.7 |

| FQQYVQEC@ADILE*WIGDK ↔ G*SMEQFPK | 3146.4613 | 1049.4920 | 3 | 0.5 |

| VNILTDK*SYEDPTNIQGK ↔ VLETAE*EIQER | 3332.6897 | 833.9279 | 4 | 1.2 |

| G*SMEQFPK ↔ VVEVNQYANEC@AEE*NHPDLPLIQS | 3800.7849 | 950.9517 | 4 | −1.2 |

| Cross-links that support a closed dimer conformation | ||||

| G*SMEQFPK ↔ TAAINAD*E*LPTDVAGGEVLLDR | 3144.5513 | 1048.8553 | 3 | −0.2 |

| G*SM#EQFPK ↔ FQSADE*TGQDLVNANHEASDEVR | 3452.5325 | 1151.5157/863.8886 | 3/4 | 0.9 |

FIGURE 5.

Chemical cross-links identified in mini-spectrin dimer. A, shown is a side view of the 10 conformations (PDB 1OWA) reported for the α1–156 NMR structure (25) and a perpendicular view that highlights the highly flexible nature of the N-terminal 15 amino acids as well as the connector between α0 and α1. B, the locations of two identified cross-link sites in the mini-spectrin dimer are superimposed on one of the available NMR structures (shown in A), and distances between the cross-links are shown. An arrow indicates the location of this α0–1 motif (enclosed by a dotted line) in a schematic representation of the mini-spectrin dimer in an open conformation. The cross-links that support this conformation are indicated by red lines (the same intrachain cross-links superimposed on the ribbon model of the NMR structure). The red dashed lines indicate cross-links between the α-amine of the N-terminal residue and residues (large red dots) in the α2 repeat. C, shown is an alternative NMR structure for the α1–156 repeat (shown in A). An arrow indicates the location of the α0–1 motif (enclosed by a dotted line) in a schematic representation of the mini-spectrin dimer in a closed conformation. The cross-links that support this conformation are shown with magenta dashed lines to indicate cross-links between the α-amine of the N-terminal residue and residues (large magenta dots) in the α4 repeat.

DISCUSSION

In addition to providing a useful template for further studies of divalent tetramer association, the mini-spectrin described herein provides a number of novel insights into structural and functional properties of spectrin. One previous ambiguity concerning spectrin heterodimer assembly has been whether the high affinity dimer initiation site simply sequesters the remaining α and β repeats in close proximity so that they can form weak lateral associations or if more complex mechanisms such as transmission of conformational changes along the chain or cooperative binding of sequential repeats propagating out from the dimer initiation site are required (7, 8, 26, 27). Evaluation of this mini-spectrin demonstrates that simply sequestering α and β repeats in close proximity is sufficient for the weak lateral associations in the heterodimer to occur. Furthermore, these interactions may not be quite as weak as previously thought as only one to two weak lateral associations (α5–β16 and α4–β17) are apparently sufficient to lock the protein into this laterally paired conformation. If a significant amount of the mini-spectrin would exist in the extended form, even transiently in equilibrium with the laterally paired conformation (Fig. 1B), polymers of linear chains should quickly form at the concentrations used for most of our studies. However, no evidence of polymers was detected in either the sedimentation equilibrium analyses or the HPLC gel filtration experiments, no turbidity or precipitation of mini-spectrin preparations were observed, and essentially quantitative recoveries of total proteins were consistently obtained as non-polymeric species. Furthermore, when the α0–5 recombinant protein was combined with mini-spectrin dimers, the complex formed rapidly and exhibited a Stokes radius indicative of a side-to-side complex rather than an extended structure (data not shown). This further supports the model where the weak lateral associations between α5-β16 and α4-β17 are sufficient to prevent an extended dimer structure.

The Stokes radii of the mini-spectrin dimer and tetramer are in good agreement with the sizes predicted based upon other well characterized spectrin single- and double-strand (laterally associated dimers) recombinant proteins and our predicted schematic models. For example, comparison of the models shown in Fig. 2 with the data in supplemental Fig. 2 shows that the α0–5 recombinant has a Stokes radius equivalent to a 5.5 repeat spectrin monomer as expected, whereas the laterally paired open dimer is slightly larger than the α0–5 monomeric recombinant (single strand), due to a similar molecular length to that of α0–5 but with two laterally associated repeats. In contrast, the closed dimer is slightly more compact, as would be expected because the longer α-chain folds back upon itself and forms a shorter, completely two-stranded structure. Consistent with the model for a closed dimer (Fig. 2B), its observed Stokes radius (data point c in supplemental Fig. 2) matches a 3.5 repeat two-stranded spectrin recombinant. Finally, the tetramer with seven laterally associated repeats (data point d in supplemental Fig. 2) is only slightly larger than predicted by the curve for laterally associated seven repeat spectrin complexes. Taken together, these data are consistent with the predicted molecular shapes and intramolecular arrangements illustrated in. Further confirmation of our interpretation of the predicted molecular shapes comes from the mini-spectrin R28S mutant. Previous studies showed this mutation was incapable of forming tetrameric type complexes in a univalent head-to-head binding assay (15). The mini-spectrin R28S mutant elution position is similar to the open dimer conformation of the wild type mini-spectrin dimer (Fig. 2C), indicating the R28S mutant cannot form closed dimers. This is consistent with its inability to form head-to-head associations in univalent tetramer binding assays. Although a direct correlation between head-to-head tetramer binding and formation of closed dimers has been previously hypothesized; this is the first experimental evidence that single site mutations similarly perturb both sites.

As described above, the mini-spectrin undergoes head-to-head self-association at the tetramer site, and the dimer-tetramer interconversion is concentration- and temperature-dependent, similar to intact red cell spectrin (7, 28). At higher protein concentrations, the mini-spectrin equilibrium is shifted to predominately the tetramer as well as hexamers and larger oligomer species as has been observed for highly purified full-length spectrin in vitro (10). Most importantly, the mini-spectrin exhibits wild type tetramer binding at elevated temperatures. For example, the tetramer dissociation constant using sedimentation equilibrium analysis at 30 °C is 1 μm, regardless of the initial oligomeric state of the sample analyzed. This is in excellent agreement with the equilibrium constants reported by others for intact red cell spectrin using several methods including sedimentation equilibrium (12, 29).

Although the existence of a closed spectrin dimer has been hypothesized based on electron microscopic images and biochemical assays that indirectly probed the open or closed state, quantitative estimates of the relative amounts of the two forms and assays for evaluating their interconversion have not previously existed. Because of the reduced size of the mini-spectrin, we can now visualize and partially resolve these two forms of the dimer as shown in Fig. 2. Depending on the experimental temperature, the mini-spectrin dimer is either primarily open (room temperature or higher) or primarily closed (4 °C). This strong shift of the closed-open dimer equilibrium toward the closed state at low temperatures and open state at elevated temperatures is the same trend we observed using indirect, more cumbersome, less precise assays of full-length spectrin dimers (7). Furthermore, as summarized above, this assay allows us to independently evaluate the effects of hereditary elliptocytosis/hereditary pyropoikilocytosis mutations such as R28S on the closed-open dimer equilibrium and tetramer formation.

Further confirmation of the presence of closed and open dimers and our interpretations of motif arrangements in these states are provided by analysis of chemical cross-links using a zero-length cross-linker combined with very high mass accuracy mass spectrometry. We previously used this powerful approach for probing protein structures to confirm and refine molecular models and docking interfaces in the red cell spectrin dimer initiation site (27). As shown in Fig. 5, it was readily apparent that the observed cross-links identified two mutually exclusive structures that were consistent with the proposed schematic motif representations of the open dimer and closed dimer states. Furthermore, the observed cross-links are highly consistent with the published NMR structure of the α0–1 repeat (25), which showed the first 15 residues form a highly flexible extended structure (Fig. 5A), and in some orientations the α0 C-helix flips back onto the three-helix bundle of the α1 repeat (Fig. 5B). This latter NMR structure is highly consistent with the four cross-links observed for the open dimer form. The two cross-links observed between α0 and α1 are shown superimposed upon the NMR structure in Fig. 5B, and in the NMR structure these side chains are 12.5 and 10.6 Å apart. In this context, note that although EDC is considered a zero-length cross-linker because no extra atoms are introduced between the cross-linked residues, analyses of proteins with known crystal structures have shown residues up to about 10 Å apart are cross-linked by EDC due to side-chain flexibility (30). Furthermore, the two cross-links shown in Fig. 5B that involve the N-terminal residue and sites in the α2 repeat are consistent with an open dimer, but not a closed dimer, based upon distance constraints defined by the N-terminal flexible “tail” in the NMR structure. Hence, the observed cross-links indicate that the structure of the N-terminal region of the open dimer in mini-spectrin closely matches the NMR structure of the isolated α0–1 recombinant.

Interestingly, further NMR studies showed that the linker region between the α0 and α1 motif becomes helical when complexed with a β16–17 binding partner, but mobility is still retained for ∼15 amino acids at the N terminus (31). These results are consistent with two cross-links observed in the mini-spectrin that would only fit a closed dimer conformation as shown by the comparison between one of the NMR structural orientations and a corresponding motif schematic of the closed dimer as shown in Fig. 5C. This conclusion is based upon the observations that the distance from the N terminus to the start of the α0 helix indicated in the NMR structures is ∼50 Å, and the length of each spectrin repeat is about 50 × 25 Å as determined from crystallography structures (16, 32). Therefore, for a cross-link to form between the N terminus of α spectrin and repeat 2, the mini-spectrin would have to be in an open conformation, and cross-links between the N terminus and repeat 4 could only occur if the mini-spectrin is in a closed conformation. Taken together, our data together with the NMR structures provide a compelling argument for facile interconversion of an interrepeat linker region between helical and highly flexible conformations in large recombinant constructs capable of physiological bivalent tetramer-open dimer-closed dimer equilibria.

As described above, the mini-spectrin described in this study closely mimics most structural and functional properties of the full-length spectrin tetramer region. There are however, two fairly subtle differences. First, compared with intact red cell spectrin, the mini-spectrin shows an increased propensity to form oligomers larger than tetramers at high concentrations, possibly due to the much smaller number of weak laterally associated repeats in the open dimer conformation compared with full-length dimers. Interestingly, it is now well known that formation of very large spectrin oligomers only occurs in vitro, and poorly understood constraints on intact red cell membranes limit the in vivo oligomer state to primarily tetramers with a few hexamers. Further exploration of structural factors that influence formation of higher oligomers using mini-spectrin constructs may provide insights into the forces that constrain higher oligomer formation in vivo. The second variation between full-length and mini-spectrin is that although both show dramatically reduced kinetics of interconversion of dimers and tetramers at low temperatures, the low temperature freezing of non-equilibrium states is less effective for mini-spectrin. We had previously hypothesized that preferential conversion of dimers to the closed form at low temperatures and a high energy of activation for the closed-open dimer transition were responsible for the low temperature freezing of non-equilibrium states. The current results indicate that closed dimers are partially, but not completely, responsible for the low temperature freezing of non-equilibrium states. Additional factors that may contribute to the low temperature freezing are the non-homologous C-terminal region, phosphorylation of the non-homologous C-terminal region, or indirect contributions of additional, more distal laterally paired repeats.

In summary, these studies show that the mini-spectrin fusion protein is a well folded fully functional spectrin dimer that retains most of the properties of full-length intact spectrin dimers. It is a good model for bivalent tetramer formation at physiological temperatures as it exhibits tetramer dissociation constants indistinguishable from full-length spectrin. Analysis of this protein has shown that a short flexible linker between the α- and β-subunits is sufficient to induce lateral pairing of repeats near the tetramer site. Specifically, the short linker sequence is able to sequester β16–17 next to α4–5 to form weak lateral associations. HPLC gel filtration assays and chemical cross-linking experiments show that the dimer exists in open and closed conformations and the HPLC assay provides the first biochemical detection of the two forms, which should enable more facile monitoring of their interconversion. Interestingly, the N-terminal region in both the closed and open forms is highly flexible, and other structural features defined by chemical cross-links closely correlate with NMR structures of the isolated α0–1 recombinant.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL38794 (to D. W. S.) and HL65448 (to P. G. G.). This work was also supported by institutional grant to the Wistar Institute Grant CA10815.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–9 and Tables 1–6.

WinMATCH, Win REED, and WinNONLIN are available from the Analytical Ultracentrifugation Facility at the University of Connecticut via the FTP site. The program SEDNTERP was written by T. Laue, J. Hayes, and J. Philo, and is available on the Reversible Associations in Structural and Molecular Biology website.

- PMSF

- phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- HPLC

- high performance liquid chromatography

- EDC

- 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide

- sulfo-NHS

- sulfo-N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide

- FT-ICR

- Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance

- LC

- liquid chromatography

- MS

- mass spectroscopy

- Bis-Tris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bennett V., Baines A. J. (2001) Physiol. Rev. 81, 1353–1392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett V., Gilligan D. M. (1993) Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 9, 27–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohanian V., Wolfe L. C., John K. M., Pinder J. C., Lux S. E., Gratzer W. B. (1984) Biochemistry 23, 4416–4420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan A. A., Hanada T., Mohseni M., Jeong J. J., Zeng L., Gaetani M., Li D., Reed B. C., Speicher D. W., Chishti A. H. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14600–14609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baines A. J. (2009) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37, 796–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Speicher D. W., Marchesi V. T. (1984) Nature 311, 177–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeSilva T. M., Peng K. C., Speicher K. D., Speicher D. W. (1992) Biochemistry 31, 10872–10878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ursitti J. A., Kotula L., DeSilva T. M., Curtis P. J., Speicher D. W. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 6636–6644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Speicher D. W., DeSilva T. M., Speicher K. D., Ursitti J. A., Hembach P., Weglarz L. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 4227–4235 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrow J. S., Marchesi V. T. (1981) J. Cell Biol. 88, 463–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tse W. T., Lecomte M. C., Costa F. F., Garbarz M., Feo C., Boivin P., Dhermy D., Forget B. G. (1990) J. Clin. Invest. 86, 909–916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ungewickell E., Gratzer W. (1978) Eur. J. Biochem. 88, 379–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ralston G. B. (1978) J. Supramol. Struct. 8, 361–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.An X., Lecomte M. C., Chasis J. A., Mohandas N., Gratzer W. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 31796–31800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaetani M., Mootien S., Harper S., Gallagher P. G., Speicher D. W. (2008) Blood 111, 5712–5720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan Y., Winograd E., Viel A., Cronin T., Harrison S. C., Branton D. (1993) Science 262, 2027–2030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambrook J., Russell D. (2001) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratroy Manual, 3rd Ed., pp. 5.1–5.90; 8.1,–8.80; 13.1,–13.105; and 15.1–15.65, Cold Spring Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harper S., Speicher D. W. (1998) in Current Protocols in Protein Science (Coligan J. E., Dunn B. M., Ploegh H. L., Speicher D. W., Wingfield P. T. eds) pp 6.6.1–6.6.21, John Wiley & Sons, New York [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yphantis D. A. (1964) Biochemistry 3, 297–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson M. L., Correia J. J., Yphantis D. A., Halvorson H. R. (1981) Biophys. J. 36, 575–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luckow E. A., Lyons D. A., Ridgeway T. M., Esmon C. T., Laue T. M. (1989) Biochemistry 28, 2348–2354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Speicher K., Kolbas O., Harper S., Speicher D. (2000) J. Biomol. Tech. 11, 74–86 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lecomte M. C., Nicolas G., Dhermy D., Pinder J. C., Gratzer W. B. (1999) Eur. Biophys. J. 28, 208–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehboob S., Luo B. H., Patel B. M., Fung L. W. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 12457–12464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park S., Caffrey M. S., Johnson M. E., Fung L. W. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 21837–21844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li D., Harper S., Speicher D. W. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 10585–10594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li D., Tang H. Y., Speicher D. W. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1553–1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris M., Ralston G. B. (1989) Biochemistry 28, 8561–8567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shahbakhti F., Gratzer W. B. (1986) Biochemistry 25, 5969–5975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Shafey A., Tolic N., Young M. M., Sale K., Smith R. D., Kery V. (2006) Protein Sci. 15, 429–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long F., McElheny D., Jiang S., Park S., Caffrey M. S., Fung L. W. (2007) Protein Sci. 16, 2519–2530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grum V. L., Li D., MacDonald R. I., Mondragón A. (1999) Cell 98, 523–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.