Abstract

There are numerous detection methods available for methods are being put to use for detection on these miniaturized systems, with the analyte of interest driving the choice of detection method. In this article, we summarize microfluidic 2 years. More focus is given to unconventional approaches to detection routes and novel strategies for performing high-sensitivity detection.

Microfluidic devices are becoming a common fixture in many laboratories. Besides the well-known advantages of reduced sample volumes and decreased analysis times when compared with macro-sized components, these devices also offer significant advantages in other ways. For instance, the ability to couple multiple channels together with minimal dead volume allows for easy handling of low mass samples. Also, the ability to easily and accurately control fluid flow has prompted researchers in other areas, such as biology or biochemistry, to use these devices.

Regardless of the nature of the analysis, the end result of the reactions, separations and other processes that occur on these miniaturized devices must be detected. In this article, we aim to provide a review of detection methods for use with microfluidic devices. Due to the ever-growing popularity of microfluidic devices, we have limited the timeframe of this review to papers published after 2007. We refer the readers to previous reviews on detection schemes used in microfluidic systems for earlier time-frames and more specific applications [1–3]. We have not attempted a comprehensive review of the literature, but have selectively chosen a sample of the articles that we believe present unique approaches to the three most common detection methods (optical, electrochemical and mass spectrometric).

Optical detection methods

The most predominant detection method in microfluidic analyses by far has been with optical means. Within this broad class, fluorescence-based detection can be considered routine. The popularity of this technique is mostlikely due to the simplicity with which microfluidic devices can be coupled to fluorescence excitation and detection schemes, as well as their ability to detect from low volume samples. There have been multiple examples of advances in detection using fluorescence-based methods as applied to microfluidic devices. Recent advances have included fluorescence lifetime-imaging (FLIM), high-throughput single-molecule imaging, multicolor analyses, surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) detection.

Fluorescence lifetime-imaging resonance was presented in 2007 as a detection method for monitoring nonequilibrium mixtures in a continuous-flow microfluidic system [4]. In this work, the authors monitored the time-resolved interaction of the DNA-intercalating dye Hoechst 33258® (H33258) with a 5.8-kbp DNA plasmid in a microfluidic reactor consisting of two inlet channels converging at a mixing channel. The two-photon fluorescence imaging system employed an ultrafast time-gated charged coupled device (CCD) to resolve the fluorescence decay of unbound H33258 (300 ps) from that of the intercalated H33258 (3.5 ns). Furthermore, the system employed a two-channel imager, which acquired fluorescence data at orthogonal polarizations allowing for calculation of time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy data. Both FLIM and time-resolved anisotropy measurements corroborated the time-dependent diffusional mixing of H33258 with DNA plasmid in the microfluidic reactor. The combination of FLIM with time-resolved anisotropy might allow for the investigation of increasingly complex molecular interactions on a microfluidic platform.

Other advancements in fluorescence-based detection have been aimed at high-throughput single-molecule imaging. Recently, the Soper group demonstrated the application of a CCD toward detection of single molecules in solution on a microfluidic platform with the aim of high-throughput DNA analysis [5]. In this work, a poly(methyl methacrylate) device incorporating an array of microchannels was illuminated by a 635-nm diode laser incident on the side of the device. In this configuration, the excitation beam passed through all microchannels and was perpendicular to the axis of observation through the microscope objective. Samples of 48.5 and 4.3 kbp DNA, labeled with the intercalating dye TOTO-3™, were electrokinetically driven through the microchannel array and fluorescence was collected by a CCD in the time integration mode, which allowed for detection of single DNA molecules. The system was capable of differentiating different-sized DNA molecules on the basis of fluorescence intensity, since TOTO-3 intercalates in a stoichiometric manner with DNA. The system demonstrated a sample throughput of 2208 molecules per second with a theoretical capacity of 1.7 × 107 molecules per second, although inefficiencies in the optical set-up made the detection of single fluorophores with this system impossible. The same group later refined this system to allow detection of singly labeled DNA molecules [6]. The principle refinements of this work included use of an electron-multiplying CCD operated in frame transfer mode and a wide field epi-illumination fluorescence system. In this configuration, the system was capable of detecting single molecules of λ-DNA labeled with AlexaFluor 660® with a calculated sample throughput of 4.02 × 105 molecules per second.

One avenue toward broadening the quantity of information that can be attained in a single fluorescence-based assay is present in multi-wavelength detection techniques. Recently, our group has developed a two-color electrophoretic competitive immunoassay for simultaneous quantification of insulin and glucagon from islets of Langerhans [7]. The assay employed fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled insulin (λex = 488 nm, λem = 520 nm) and Cy5-labeled glucagon (λex = 635 nm, λ em = 680 nm) as labeled antigens and allowed independent measurement of insulin and glucagon, even with insulin immunoassay reagents in 20-fold higher concentration than those of glucagon reagents. The presented method offered limits of detection of 7 nM insulin and 3 nM glucagon. Initially, this work was performed in capillary-based formats, but it is now being moved to microfluidic systems.

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering poses an attractive detection method for microfluidic devices due to its ability to qualitatively identify analytes. Recently, three unique approaches to SERS detection on microfluidic devices have been presented.

In 2008, Connatser et al. optimized factors to improve selectivity, sensitivity and dynamic range of their microfluidic SERS device that incorporated arrays of nanopillars derivatized with either gold or silver by surface vapor deposition [8]. The authors found that, among the series of small organic molecules tested, the chemical selectivity of the SERS system could be affected by the choice of metal for deposition on the micropillar arrays, with gold displaying a greater response for molecules containing nitro or amine moieties while silver was more responsive towards carbonyl or hydroxyl functional groups. Nanopillar geometry was presented as a critical factor affecting sensitivity, with arrays of pillars each presenting an elliptical cross-section offering the greatest response of the four geometries examined. Saturation of the SERS detector by analyte concentrations exceeding 20 μM posed a significant limit to the dynamic range of the detection system; however, the authors suggested a method of mathematically inferring peak intensities for concentrations beyond the saturation limit, thus extending the dynamic range beyond 40 μM. In an application of their system, electrophoretic separation of three endocrine-disrupting chemicals was performed, with detection accomplished by monitoring three unique Raman bands. While this data was obtained with an offline Raman detection system, the authors stated that online analysis was possible.

A recent communication demonstrated an approach to chip-based SERS that employed colloidal silver in solution, requiring no stationary support for the Raman-enhancing metal surface [9]. With this method, thiophenol or 2-naphthalenethiol were combined with colloidal silver and mixed online in the polydimethyl siloxane (PDMS) microfluidic device. Silver aggregates were formed by optical trapping of the colloidal silver in the sample mixture. SERS spectra of the analytes adsorbed onto the silver aggregates were then taken. The spectral intensities were shown to increase with increasing colloidal silver incubation time of the analyte. The authors further demonstrated the potential of the system towards high-throughput analysis by perfusing alternating sample plugs of the thiophenol and 2-naphthalenethiol analytes and recording Raman spectra for each sample plug, with minimal carryover evident from previous sample plugs. The authors state that future work will focus on functionalization of the gold surface so that analytes other than thiols can also be detected.

Another approach to localizing metal surfaces for SERS analysis was presented recently [10]. In this work, microwells with integrated electrodes were employed both in aiding the mixing of analytes with silver nanoparticles and with concentrating the nanoparticles for subsequent Raman analysis. Surfaces of silver nanoparticles were derivatized with DNA sequences complementary to a portion of the Dengue virus stereotype 2 (DENV2). The viral DNA was 5′-labeled with tertramethylrhodamine (TAMRA). The TAMRA-labeled DNA hybridized to the nanoparticle-immobilized DNA, which facilitated SERS detection of the TAMRA label.

The viral DNA was combined with the functionalized nanoparticles in a microfluidic flow channel that incorporated 10-μm-diameter microwells. A voltage applied to the microwells drew the nanoparticles and sample mixture into the microwells. The polarity of the applied potential was subsequently reversed, repelling the mixture from the microwell. Repeating this process several times facilitated mixing of the nanoparticles with the viral DNA. Finally, the particles were drawn into the microwells and the SERS spectra of captured TAMRA-labeled DENV2 DNA were recorded. The authors examined the effect of the duration and number of mixing cycles, as well as performing concentration calibrations that indicated that their system had a 30-pM limit of detection for TAMRA-labeled DENV2 DNA.

Surface plasmon resonance has become an attractive detection method for biological assays because it allows for the study of binding interactions, such as substrate–ligand binding, without the use of labels that may alter natural binding processes. Although challenged by the need to regenerate derivatized surfaces, the utility of SPR detection in biological assays makes the application of SPR detection to microfluidic devices an attractive scheme.

A communication in 2007 described the application of SPR detection to binding studies in microdroplets [11]. The specific focus of this work was the use of surface acoustic waves (SAW) in overcoming mass transport limitations, which may arise in droplet-based analyses where the volume of the droplet is large relative to the area of the liquid–solid interface where SPR is performed. The authors applied SAW to transport streptavidin from within a droplet to a biotinylated surface, while monitoring binding by SPR. One challenge of this approach was in the effect of temperature on the refractive index of an aqueous sample mixture. Continuous SAW-mediated mixing led to a temperature increase of as much as 40°C, which itself altered the refractive index and the subsequent surface plasmon signal. The authors pulsed the SAW mixing at 500 Hz, which resulted in minimal temperature elevation and, subsequently, minimal effect on SPR signal intensity, while still reducing the amount of time needed to transport streptavidin to the surface. Using this method, the authors demonstrated a twofold decrease in the time needed for complete binding of streptavidin to the surface compared with the droplet assay without SAW mixing.

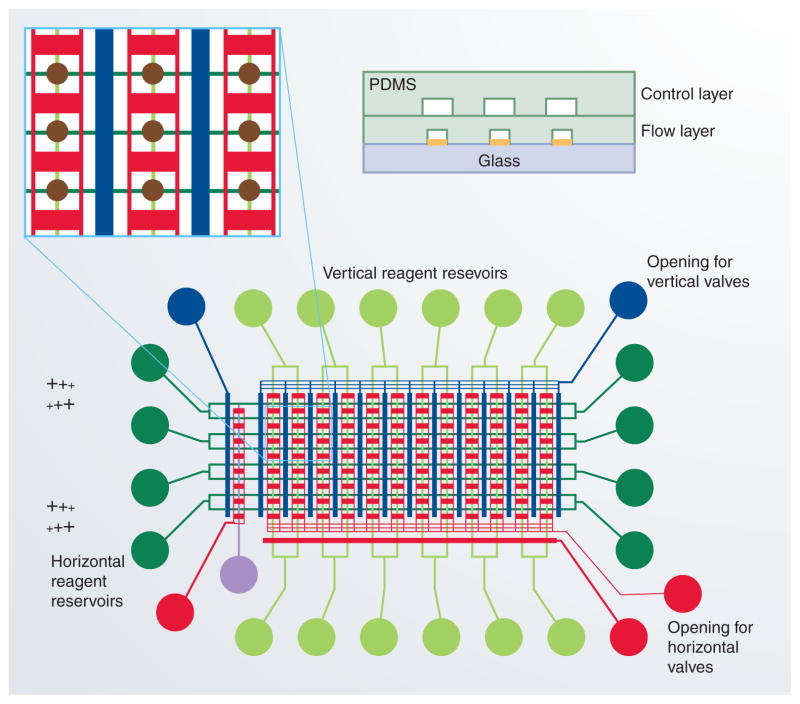

Zare’s group presented a multilayer, multi-channel microfluidic device for performing several immunoassays in parallel with detection by SPR imaging [12]. The device (Figure 1) incorporated intersecting arrays of flow channels in PDMS. The flow layer was bonded to a glass slide patterned with gold spots, such that the intersections of the flow channels were exposed to these gold spots, which acted as the SPR detection site. A second PDMS layer acted as a control layer for pneumatic valving of reagents into the flow channels. The authors applied the system to both single- and two-step immunoassays for biotin. Biotinylated bovine serum albumin was deposited onto the gold SPR detection surface by adsorption. Antibiotin antibody was then added to form an immunocomplex in a single-step immunoassay. A two-step immunoassay was then performed by adding a secondary antibody, labeled with silver nanoparticles, forming a three-component immunocomplex. A limit of detection of 210 pM was reported, which, the authors stated, approached the sensitivity of comparable enzyme-labeled immunoassays. Furthermore, the authors demonstrated the utility of real-time SPR imaging in resolving binding kinetics of both antibiotin antibody with biotin and that of the secondary antibody with the immunocomplex.

Figure 1. Microfluidic device for surface plasmon resonance imaging studies.

The blue and red channels represent valves cast in the PDMS control layer, which is shown in the cross-section inset at top right. The green channels represent flow channels cast in the PDMS flow layer. Brown spots at the intersection of flow channels represent the silver surface plasmon resonance detection spots deposited on the glass substrate. PDMS: Polydimethyl siloxane.

Reproduced with permission from [12], The Royal Society of Chemistry, © 2008.

Electrochemical detection methods

Electrochemical detection on microchip platforms has become a popular technique for implementing field-portable devices. Electrochemical detection is especially attractive for these platforms due to the high sensitivity and ease of miniaturization. Such easy-to-use and sensitive analytical tools are necessary for detecting very low concentrations of analyte in complex samples such as food, biological or environmental matrices.

Detecting nitrates in drinking water has long been a challenge for chemists. Since excessive nitrate in drinking water can lead to health problems, the US Environmental Protection Agency has set a maximum contaminant level for nitrate at 700 μM. Kim et al. has developed a microfabricated nitrate sensor using an amperometric technique capable of detecting nitrates in the range of 4 μM to 2 mM [13]. Double-potential-step chronocoulometry was used to separate non-Faradaic components from the signal, thereby increasing the signal-to-noise ratio. This technique is especially useful for water samples because it is able to separate the oxygen background current from the signal. Double-potential-step chronocoulometry integrates the current over 1 s at two potentials to determine the nitrate-reduction charge. The current is first integrated at −0.5 V, where the oxygen-reduction current reaches a small steady state, to determine the oxygen-reduction charge. The potential is then stepped to −0.98 V, where the oxygen reduction remains at a steady state and nitrate reduction begins. The difference between the two charges gives the nitrate-reduction charge. The overall microfluidic chip was designed with ease of fabrication, low cost and high sensitivity in mind. The platinum counter electrode, silver sensing and reference electrodes were patterned with a lift-off process, with the reference electrode in the center of concentric sensing and counter electrodes. The concentric design allowed for uniform current distribution between electrodes. The sensor exhibited high linearity and little chip-to-chip variability. Although corrosion of the thin-film gold-sensing electrode after repeated tests led to current spikes, the authors proposed that a thick-film sensor could increase the lifetime of the sensor, potentially making this a valuable tool for fast assays in the field.

Hormones and other biomolecules present similar challenges to analyses due to their small size and low abundance in biological samples. A nanoscale interdigitated array electrode (IDAE) was developed to detect the catecholamine L-adrenaline [14]. Adrenaline is difficult to detect by cyclic voltammetry because the oxidized product, adrenaline quinone, is easily cyclized to leucoadrenochrome, which is more easily oxidized than adrenaline. By decreasing the distance between the oxidation and reduction electrodes, adrenaline quinone can be reduced before cyclizing. Decreasing the space between electrodes and increasing the number of arrays is also beneficial as it increases the current from the IDAE. In this study, several IDAEs were fabricated with electrode widths ranging from 250 nm to 2 μm; the space between electrodes was equal to the electrode widths. Photoresist was coated onto an oxidized silicon wafer and the IDAEs (total area of 1 × 1 mm) were formed with electron beam lithography by sputtering a 50-nm thick gold film electrode over a 10-nm thick titanium buffer layer. Studies of micro-IDAEs showed that the magnitude of the limiting current increased as electrode line and space width decreased and can thus be theoretically approximated. The nano-IDAEs, however, exhibited limiting currents that were increasingly shifted to higher currents from theoretical values as line and space widths were decreased. Because the only parameter not factored into the theoretical approximation was the electrode thickness, it was determined that, upon decreasing electrode line width to the nanoscale, electrode thickness would become a factor that must be taken into account.

Conductivity detection is a common means of detecting inorganic ions in solution. Contactless conductivity detection is beneficial as the electronics are isolated from voltages applied to the separation channels. Additionally, separating electrodes from the solution prevents the formation of gas bubbles at the electrodes. To increase the capability of this detection technique, Kang et al. have bridged a miniaturized capacitively coupled contactless conductivity detector (C4D) to a piezoelectric quartz crystal [15]. The high capacitive impedance between the two contactless electrodes was effectively balanced by the inductive impedance of the piezoelectric quartz crystal to obtain minimal impedance. The electrodes were fixed to the outside of the glass lid of the chip with a gap distance of 0.25 mm. By decreasing the thickness of the microchip lid from 1.0 to 0.20 mm, the LOD was reduced from 1.6 to 0.38 μM. This low-impedence C4D offers an advantage over uncoupled C4D in the high sensitivity to solution conductance and simplicity in design and fabrication.

Single- and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNT and MWCNT, respectively) are a new group of nanomaterials that have been widely used in electroanalysis, yet scarcely applied to microdevices. In one application of these devices in microfluidic platforms, the working electrode of an amperometric detector was a carbon thick-film screen-printed electrode (SPE) [16]. The bare SPE was tested against SWCNT- and MWCNT-modified SPEs to determine the effects of nanotubes on the detection of dietary antioxidants. MWCNT-modified SPEs gave higher sensitivity and lower noise than bare SPEs and SWCNT SPEs and were therefore used in analysis of dietary anti-oxidants. LODs were in the micromolar range with relative size distribution values of less than 11% for all antioxidants. A high degree of linear correlation was observed between calibration plots of both unmodified and MWCNT-modified detectors. MWCNT-SPEs had four- to 16-fold enhanced sensitivity over the unmodified detector, as well as improved resolution in the detection of antioxidants in food samples.

One of the main advantages of microfluidics is the ability to both process and analyze samples with little sample handling. Adams et al. developed a microfluidic device that was able to selectively isolate and detect circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in whole-blood samples [17]. CTCs are responsible for generating metastatic tumors, yet the extremely low abundance of these cells in whole blood samples makes quantitation of CTCs difficult. A high-throughput microsampling unit was developed to effectively isolate CTCs using antibodies specific to integral membrane proteins expressed in CTCs. Captured cells were released upon enzymatic digestion of antigen–antibody complexes and detected with an integrated conductivity sensor that specifically detected the CTC electrical signature. CTCs have low membrane potential due to the intracellular migration of sodium ions and the increased negative charge on the membrane surface, due to the increased number of sialic acids, which cap integral proteins. Platinum wires were positioned perpendicular to the 50 μm wide microfluidic channel, producing a cell constant of K = 0.01 μ/m (where K is defined as the ratio of the space between electrodes to the electrode area). The cell constant was specific for CTCs due to their larger size with respect to other cells circulating in the blood. When CTCs passed between the electrodes, a positive signal relative to the background was produced; the variable-response signal was dependant on the mitosis phase of the cell. The sensor selectively detected single CTCs with nearly 100% recovery, while also being capable of processing large volumes in under 30 min.

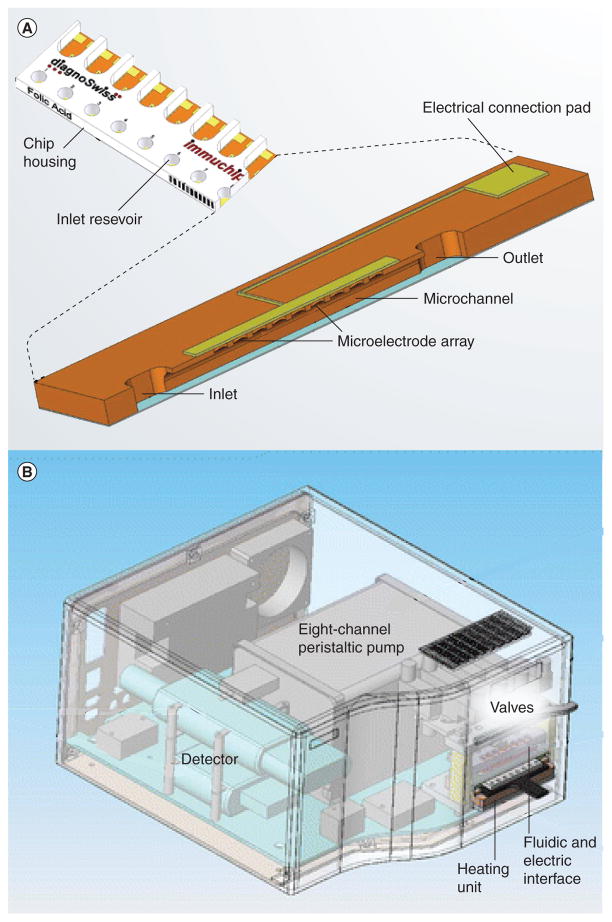

The lab-on-a-chip concept has led researchers to alter popular assays to chip formats to decrease run time and reagent consumption. The ELISA is a popular assay in clinical diagnostics as well as in quality control of regulated products. Hoegger et al. reduced the scale of an ELISA to allow up to eight assays to run in parallel in a few minutes with a microelectrode array [18]. The microelectrode array detected enzymatic product and was also able to monitor flow rate. The chip was composed of a 1-cm long channel with a peristaltic pump connected to the outlet to control the flow (Figure 2). Separate valves allowed individual access to the microchannels. Each channel contained an array of 48-gold working electrodes, a counter electrode and Ag/AgCl reference electrode that was located at the bottom of the inlet reservoir. After coating the surface of the channel with BSA-conjugated folic acid, a mixture of the sample containing folic acid and an antifolic acid antibody conjugated with alkaline phosphatase were loaded into the channel. This solution was pumped through the device and the flow rate was monitored by detecting dissolved oxygen at −800 mV versus Ag/AgCl. Although the concentration of an electroactive species would decrease rapidly in the area of an electrode in a closed environment, because fresh solution was constantly passing the electrode, the local concentration of the redox species increased to its maximum value, which increased the resultant current. Once the reagents had been allowed to react for 4 s, flow was stopped and the enzymatic substrate was aspirated into the channel. Amperometric detection was performed at 250 mV versus Ag/AgCl to detect the product, p-aminophenol, as a function of time. This system demonstrated a fast competitive immunoassay with an embedded flow sensor capable of running several different assays in parallel.

Figure 2. Multichannel microfluidic ELISA.

(A) Each of the eight channels contains inlet and outlet reservoirs, allowing access to the microfluidic channels. A 48-gold working electrode array located along the top of each channel is connected via the connection pad to the detector. (B) The measuring instrument contained an eight-channel peristaltic pump and eight separate valves, which allowed individual access to the microchannels. The instrument also included circuitry for amperometric detection.

Reproduced with permission from [18], © Springer Publishing Company, 2007.

MS detection methods

Microfluidic integration of separation with MS is attractive because of the potential ease of parallel and multiple analyses. In interfacing microfluidic devices to any mass analyzer, ESI and MALDI interfaces are two of the most commonly used methods for ionization of large bio-molecules [19]. Therefore, recent developments in interfacing microchips to MS focus on these two ionization methods.

A simple and rugged electrospray tip was integrated to a microchip in which ionization was performed from the corner of the rectangular glass device [20]. The tested chip design included a gated-injection tee with a separation channel that extended to one corner of the device. All of these channels, except for a side channel located 200 μm from the end of the separation channel, were coated with a polyamine solution to reverse electro-osmotic flow. By applying a higher positive potential at the reservoir of the side channel than the potential at the injection cross, the 200-μm length of channel after the intersection of the side channel was made field free. The analytes were thus effectively pumped down this field-free region at 40 nl/min and sprayed to the MS. The group demonstrated that the field-free region did not significantly contribute to peak band broadening. The mass spectrum from the integrated ESI source produced half of the baseline noise compared with a commercial nanospray capillary emitter. Separation efficiency was demonstrated through injection of mixtures of proteins and peptides with separation peaks yielding 106 plates/m. A promising prospect of the integrated ESI includes applications in top-down and bottom-up proteomic strategies.

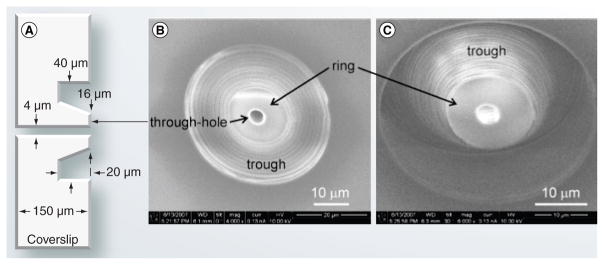

Another example of ESI integration into microfluidic devices was made by the Jacobson group using water-assisted laser machining to fabricate single and multiple electrospray nozzles over any microchannel at any location in the assembled microfluidic devices [21]. Each nozzle consisted of a through-hole, ring and trough (Figure 3). The through-hole was made using 60 nJ/pulse to drill through a microfluidic device over 1 mm thick. A ring was located between the through-hole and the trough with the trough confining the electrospray and preventing liquid from wicking across the glass surface. Stable electrospray was maintained with and without pressure-driven flow through the microfluidic device with the integrated nozzle.

Figure 3. Laser-machined electrospray nozzle.

(A) Side-view of the nozzle with typical nominal values. (B) Top view of the fabricated nozzle. (C) Side view of the nozzle at 30°.

Reproduced with permission from [21], © 2008, Optical Society of America.

Kim et al. had a unique approach to fabrication of ESI nozzles, in that an array of monolithic, integrated and biocompatible multinozzle electrospray emitters (M3) at the end of microfluidic channels was fabricated [22]. Densities of 100 nozzles/mm were fabricated using a silicon/silica-based microfabrication process. Fabrication involved the initial photolithographic patterning of microfluidic channels design onto a p-type silicon wafer, where the channels were etched via deep reactive-ion etching. Once the patterned wafer was cleaned, it was annealed to another unfeatured wafer to form closed channels. Both ends of the channels were cut with a saw so that wet oxidation could be used to grow a layer of protective SiO2. Then, 2–3 mm of the wafer was cut off from the side where the nozzles were fabricated, in order to expose the silicon layer to be etched with XeF2. By etching the exposed silicon, protruding SiO2 nozzles of 200 μm in length were made. Electrical contact from the M3 emitters was made through aluminum tape attached to the side of the channel. In terms of resolution and sensitivity for the peptide Glu-fibrinopeptide B and the protein BSA, it was found that the M3 performances were comparable to commercial pulled fused-silica capillary nanoelectrospray tips. By fabricating the emitters from hydrophilic silicon dioxide, the group has made multinozzle electrospray emitters more compatible with biomolecular applications.

Although microfluidic integration to ESI–MS is useful for analysis of large proteins and polymers, biological samples are often in high-salt buffers that are not compatible with ESI. Hence, integration of microfluidic to online MALDI–MS is attractive in that high-salt sample solutions can be used and sample clean-up can be integrated with target preparation. Murray and colleagues increased throughput of offline sample droplet deposition onto MALDI target plates by constructing a plastic microfluidic device that contained an automated proteolytic digestion bioreactor and droplet-deposition system [23]. After the tryptic digestion in the bioreactor, the digestion products were mixed on-chip with MALDI matrix in sealed coaxial tubes and each fraction was then deposited onto a target plate in 20 s. The droplets were reproducible, with sizes of 1.5 mm in diameter and standard deviations within 0.2 mm, producing a total volume of approximately 2.0 μl.

Similar to the array of ESI tips, Lee et al. used arrays of microfluidic nozzles to deposit droplets onto MALDI target plates [24]. These droplets, a few hundred nanoliters each, were produced from various biochemical reactions performed on their hybrid silicon/PDMS microfluidic device. This report demonstrated the utility of their microfluidic device, which could potentially be used for a large variety of reactions.

Future perspective

Microfluidic devices are only as useful as the detection methods used in analyses. Fluorescence-based detection is still the most common means of detection in microfluidic devices, although there are disadvantages to using this scheme – namely, the analyte must be fluorescent or fluorescently tagged. New means of detection that will allow high sensitivity, low LODs and qualitative information will be needed for the field of micro-fluidics to continue to flourish. The papers presented in this review are some of the first examples of unique detection approaches in microfluidic analyses, although much more work is needed in the future for successful incorporation of these methods to real-world samples.

In the future, it is expected that more information-rich optical detection methods will be utilized that can provide both qualitative and quantitative information on the analyte. Electrochemical analyses will continue to be miniaturized and may be a driving force for true micrototal analysis systems. However, as more analyses are being performed by MS, the difficulties in coupling this method to microfluidic devices must be overcome to reap all the benefits of this detection scheme.

Executive summary

Optical detection methods

Advances in fluorescence detection are moving towards information-rich techniques, such as fluorescence lifetime-imaging microscopy or multicolor analyses.

Surface-enhanced Ramon spectroscopy offers the potential for both qualitative and quantitative characterization of analytes.

Surface plasmon resonance analysis allows for optical detection of analytes without labeling or derivatization.

Electrochemical detection methods

Microelectrodes are easily integrated into portable microfluidic devices allowing in-field sample analyses.

Common electrochemical detection methods are coupled with novel electrochemical detection materials for analyses of a variety of samples

MS detection methods

Microfluidic electrospray ionization and MALDI interfaced with offline mass spectrometers are the most popular techniques used.

While the coupling of MS to microfluidics is difficult, this analysis method can provide substantial information.

Acknowledgments

Michael G Roper acknowledges support from the NIH (R01 DK080714) and the American Heart Association Greater Southeast Affiliate.

- Fluorescence lifetime-imaging

Visualization of fluorescence decay rates can provide spectral discrimination

- Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy

High-sensitivity vibrational spectroscopy of molecules adsorbed to a metal surface

- Double-potential-step chronocoulometry

Initial potential is instantaneously stepped to first potential and held for a length of time before being ramped to a second potential

- Contactless conductivity detection

Detection of inorganic or organic ions where electrodes are separated form ions by an insulating film

- M3

Monolithic multinozzle emitters developed to integrate electrospray nozzle with microfluidic channels

Footnotes

For reprint orders, please contact reprints@future-science.com

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪▪of considerable interest

- 1.Gotz S, Karst U. Recent developments in optical detection methods for microchip separations. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;387:183–192. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0820-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams KL, Puchades M, Ewing AG. In vitro electrochemistry of biological systems. Ann Rev Anal Chem. 2008;1:329–355. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.113038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazar IM. Recent advances in capillary and microfluidic platforms with MS detection for the analysis of phosphoproteins. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:262–275. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4▪▪.Benninger RKP, Hoffman O, Önfelt B, et al. Fluorescence-lifetime imaging of DNA–dye intercalations within continuous-flow microfluidic systems. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:2228–2231. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604112. Significant demonstration of the breadth of information attainable from microfluidic fluorescence-lifetime-imaging detection. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emory JM, Soper SA. Charge-coupled device operated in time-delayed integration mode as an approach to high-throughput flow-based single molecule analysis. Anal Chem. 2008;80:3897–3903. doi: 10.1021/ac800447x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okabare PI, Soper SA. High throughput single molecule detection for monitoring biochemical reactions. Analyst. 2009;134:97–106. doi: 10.1039/b816383a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guillo C, Roper MG. Two color electrophoretic immunoassay for simultaneous measurement of insulin and glucagon content in islets of Langerhans. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:410–416. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connaster RM, Cochran M, Harrison RJ, Sepaniak MJ. Analytical optimization of nanocomposite surface-enhanced Raman specetroscopy/scattering detection in microfluidic separation devices. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:1441–1450. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tong L, Righini M, Gonzalez MU, Quidant R, Käll M. Optical aggregation of metal nanoparticles in a microfluidic channel for surface-enhanced Raman scattering analysis. Lab Chip. 2009;9:193–195. doi: 10.1039/b813204f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huh YS, Chung AJ, Cordovez B, Erickson D. Enhanced on-chip SERS based biomolecular detection using electrokinetically active microwells. Lab Chip. 2009;9:433–439. doi: 10.1039/b809702j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galopin E, Beaugeois M, Pinchemel B, Camart JC, Bouazaoui M, Thomy V. SPR biosensing coupled to a digital microfluidic microstreaming system. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;23:746–750. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12▪.Luo Y, Yu F, Zare RN. Microfluidic device for immunossays based on surface plasmon resonance imaging. Lab Chip. 2008;8:694–700. doi: 10.1039/b800606g. Novel device design incorporating vapor-deposited metal-detection spots with the microfluidic architecture. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim D, Goldberg IB, Judy JW. Microfabricated electrochemical nitrate sensor using double-potential-step chronocoulometry. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2009;135:618–624. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi K, Takahashi J, Horiuchi T, Iwasaki Y, Haga TJ. Development of nanoscale interdigitated array electrode as and electrochemical sensor platform for highly sensitive detection of biomolecules. Electrochem Soc. 2008;155:J240–J243. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang Q, Shen D, Li Q, et al. Reduction of the impedance of a contactless conductivity detector for microchip capillary electrophoresis: compensation of the electrode impedance by addition of a series inductance from a piezoelectric quartz crystal. Anal Chem. 2008;80:7826–7832. doi: 10.1021/ac800380g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16▪.Crevillén AG, Avila M, Pumera M, Gonzalez MC, Escarpa A. Food analysis on microfluidic devices using ultrasensitive carbon nanotubes detectors. Anal Chem. 2007;79:7408–7415. doi: 10.1021/ac071247i. One of the first studies to explore carbon nanotubes as an electrochemical detection material on the microfludic scale. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams AA, Okagbare PI, Feng J, et al. Highly efficient circulating tumor cell isolation from whole blood and label-free enumeration using polymer-based microfluidics with an integrated conductivity sensor. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8633–8641. doi: 10.1021/ja8015022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoegger D, Morier P, Vollet C, Heini D, Reymond F, Rossier JS. Disposable microfluidic ELISA for the rapid determination of folic acid content in food products. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;387:267–275. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0948-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19▪▪.Lazar IM, Grym J, Foret F. Microfabricated devices: a new sample introduction approach to mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2006;25:573–594. doi: 10.1002/mas.20081. Fairly recent, comprehensive review of microfluidic MS for proteomics samples. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mellors JS, Gorbounov V, Ramsey RS, Ramsey JM. Fully integrated glass microfluidic device for performing high-efficiency capillary electrophoresis and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2008;80:6881–6887. doi: 10.1021/ac800428w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.An R, Hoffman MD, Donoghue MA, Hunt AJ, Jacobson SC. Water-assisted femtosecond laser machining of electrospray nozzles on glass microfluidic devices. Opt Express. 2008;16:15206–15211. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.015206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim W, Guo M, Yang P, Wang D. Microfabricated monolithic multinozzles emitters for nanoelectrospray mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2007;79:3703–3707. doi: 10.1021/ac070010j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee J, Musyimi HK, Soper SA, Murray KK. Development of an automated digestion and droplet deposition microfluidic chip for MALDI–TOF MS. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2008;19:964–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S, Lee C, Kim B, Kim Y. An integrated microfluidic chip for the analysis of biochemical reactions by MALDI mass spectrometry. Biomed Microdevices. 2008;10:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10544-007-9104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]