Abstract

Using 10 nationally representative surveys conducted between 1993 and 2005 we assess the extent to which the vulnerability of orphans to poorer educational outcomes has changed over time as the AIDS crisis deepens in South Africa. In line with the existing literature we find that at every point in time orphans are at risk of poorer educational outcomes with maternal deaths generally having stronger negative effects than paternal deaths. However, despite a significant increase in the number of orphans over the last decade, we find no evidence of a systematic strengthening of these negative effects. In order to understand this we explore patterns of care giving for orphans. We find that these patterns have shifted over time. While orphans are still absorbed into extended families, single orphans are increasingly less likely to live with the surviving parent and there is an increasing reliance on grandparents as caregivers. Up to this point, these changing patterns of care giving within extended families seem to have avoided further worsening in the educational outcomes for the increasing number of orphans.

1. Introduction

The rapid growth in the number of orphans in sub-Saharan Africa due to the HIV/AIDS pandemic has received much attention in the literature, with UNAIDS (2004) estimating that fifty million children under the age of 15 will have lost at least one parent by 2010. Since the early 1990s the percentage of children in South Africa who have lost mothers and fathers has tripled and doubled respectively and further increases in the prevalence of orphanhood are expected for the next decade (Ardington 2008, Johnson and Dorrington 2001).

The extended family has been the predominant social safety net mechanism in sub-Saharan Africa with children who lose their parents being absorbed into their relatives’ families leading to the traditional assertion that “there is no such thing as an orphan in Africa” (Foster 2002:1907). There is increasing concern among a number of researchers and international agencies that extended family networks are already overwhelmed by the magnitude of the orphan crisis and that these traditional coping mechanisms may not be adequate in the face of the ever growing number of orphans (Kelly 2000, Foster 2000 & 2002, UNICEF 2003, Guarcello et al. 2004:2). The consequence has been a growing body of research on the prevalence of orphanhood and the living arrangements, health and education outcomes of orphans. Education has received special attention. Recent empirical evidence suggests that children who have suffered parental loss are at risk of poorer educational outcomes with the death of a mother generally having greater impacts on children’s schooling than the death of a father (Bicego, Rustein and Johnson 2003, Case, Paxson and Ableidinger 2004, Monash and Boerma 2004, Guarcello et al. 2004, Case and Ardington 2006, Beegle, de Weerdt and Dercon 2006, Evans and Miguel 2007). This empirical work challenges the assertion that ‘there is no such thing as an orphan in Africa’. While this statement may be true in the sense that the vast majority of African orphans are absorbed into their extended family networks, orphans are not indistinguishable from non-orphaned children in that they are vulnerable to poorer outcomes. Yet, in spite of the concerns around the capacity of extended family networks to cope with the ever increasing number of orphans, surprisingly little is known about whether the vulnerabilities of orphans are changing as the AIDS crisis deepens.

The critical importance of education to many of the issues facing sub-Saharan Africa is widely acknowledged. Education lies at the foundation of “lifelong learning and human development” (UNESCO 1990) and is key to understanding the intergenerational transmission of inequality. Poor educational outcomes in childhood are likely to have a lasting effect into adulthood. It is no surprise, therefore that educational outcomes have featured prominently in assessing the impact of orphanhood.

This paper adds South African evidence; showing orphans to be especially vulnerable to poor schooling outcomes. The key contribution is to assess the extent to which this vulnerability has changed over time as the AIDS crisis deepens in South Africa. We examine the impact of orphanhood on both enrolment and attainment. Much of the research to date has focused on enrolment rather than educational attainment. Ainsworth and Filmer (2006:1107) claim that “the countries most affected by the AIDS epidemic have among the lowest enrolment rates in the world.” For Africa at least their claim is not borne out in the data. There does not appear to be a negative association between HIV prevalence and enrolment. Indeed some of the countries with the highest HIV prevalence have the highest enrolment rates. In the literature the contrast between enrolment of orphans and non-orphans is greatest in countries where enrolment is already low (UNICEF 2003). For countries with high enrolment any educational deficits that orphans may experience are more likely to be apparent when looking at educational attainment.

South Africa is a particularly interesting case study for a number of reasons. Most importantly, rates of orphanhood have risen sharply and will continue to do so for the next decade. Adult mortality prior to the AIDS epidemic was much lower in South Africa than elsewhere in the region. This combined with high and rapidly rising HIV prevalence means that South Africa is expected to experience among the highest growth in the rate of orphanhood in sub-Saharan Africa (Johnson and Dorrington 2001, Anderson and Phillips 2006). In addition, South Africa has an interesting educational context. Although South Africa has almost universal enrolment in primary school, the schooling system is still characterized by racial inequities and high rates of grade repetition with many African students never completing secondary school. Unlike many other high prevalence countries, South Africa has not seen any substantial increases in enrolment over the last fifteen years. Completion of secondary school and tertiary education are strongly associated with the probability of employment and there are strong convexities in the returns to education for those in employment (Anderson, Case and Lam 2001, Keswell and Poswell 2003). Education is key, therefore, to understanding persisting racial differences in income and employment and the intergenerational transmission of inequality.

Given the combination of high unemployment, a history of labour migration, the impact of HIV/AIDS on the working age population, and a welfare policy that is dominated by an extensive state old-age non-contributory pension, family support structures in South Africa are unusually complex. Monash and Boerma (2004) suggest that coping strategies that rely on the extended family may be less resilient than elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa due to high levels of work related migration and associated high rates of child fostering. On the other hand, South Africa has a well developed system of social grants that may strengthen traditional support mechanisms. A number of researchers (Case and Deaton 1998 and Duflo 2003 for example) have found that living with a pensioner has positive benefits for poor children.

All-in-all the combination of South Africa’s HIV/AIDS prevalence, education system and family support structures make it an especially interesting context in which to explore the relationship between orphanhood and educational outcomes and how these have changed over the time. Despite this and the availability of over a decade of large nationally representative datasets, there is very little nationally representative research on orphanhood.1 We seek to rectify this and use 10 nationally representative surveys conducted between 1993 and 2005 to investigate the relationship between parental death and schooling outcomes. At every point in time, cross-sectional evidence suggests that orphans are still absorbed into extended families. However, children who have lost one parent are increasingly less likely to live with the surviving parent and there is an increasing reliance on grandparents as caregivers. Orphans throughout the period of the study, are at risk of poorer educational outcomes with maternal deaths having stronger negative effects than paternal deaths.2 Results for maternal deaths are not affected by the inclusion of controls for socio-economic status suggesting that maternal death is directly associated with poorer schooling outcomes rather than channeled through socio-economic status. In contrast much of the schooling deficit for paternal orphans is explained by their relative poverty. Looking for evidence of changes over time we find no evidence of a systematic deterioration in the educational outcomes of oprhans. The evidence of this paper suggests that, stressed as they may be and despite a significant increase in the number of orphans to be absorbed, extended family networks have still managed to provide similar levels of support in recent years as a decade ago.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section describes the data and definitions used in this study and presents trends in rates of orphanhood. Section 3 begins with a brief summary of the living arrangements and economic well-being of orphans and non-orphaned children. This provides the necessary background to the key sub-section, assessing the extent to which the relationship between orphanhood and schooling outcomes (educational attainment and enrolment) has changed over time. In each sub-section we discuss results from each of the ten cross-sections as well as from pooled data sets. Section 4 summarizes the key results and discusses policy implications.

2. Data, definitions and rates of orphanhood

Data and definitions

The analysis in this paper is based on all publicly available nationally representative South African datasets that include questions on parents’ vital status. We use the 1993 Project for Statistics on Living Standards (PSLSD), the 1995, 1997 and 1998 October Household Surveys (OHS), the 1996 and 2001 Censuses, and the 2002-2005 General Household Surveys (GHS). In addition to data on parents’ vital status all of these surveys collected data on years of completed education, current enrolment status, household living arrangements and a range of variables capturing the household’s living conditions.

The samples for all surveys other than the censuses were multi-stage stratified random samples of non-institutionalized households in the case of the PSLSD, OHSs and DHSs and households and hostels in the case of the GHSs. Hostels are not identified in the GHS data but the analyses in this paper focus on children of schooling going age and are unlikely to include many hostel dwellers. The sample sizes vary from 9,000 to 30,000 households. The census data used in this paper are 10% samples of the censuses with weights to adjust for the undercount. These sample sizes are large with 846,478 and 905,748 households in 1996 and 2001 respectively.

All of these surveys are conducted at the household level and ask a knowledgeable adult to list all individuals who usually live in this household. A question identifying co-resident parents was included in the household roster of all surveys other than the 1996 Census and the 1997 and 1998 OHSs.

Our results are weighted to be nationally representative and standard errors and statistical tests take the survey design (stratification and clustering) into account. The basis for the sampling and weights differ between the surveys.3 This could result in inconsistent series of various population estimates. The primary objective of this paper is however not to estimate the size of the orphan population but rather the association between parental death and schooling outcomes. Our concern is therefore limited to any biases that may be introduced into the estimates on orphan vulnerabilities and how this is changing over time. Ardington (2008) provides a much more detailed description of the idiosyncrasies of the data and the comparability of key variables of interest across surveys. Here we restrict our attention to the consistency across surveys in defining orphans and educational enrollment and attainment.

The question about parents’ vital status was not consistently asked across all of the surveys. In the 1993 PSLSD, 1995 OHS and the 2002 and 2003 GHS the question did not explicitly refer to biological parents. In other years the terms biological, own, own by birth or natural were included in the question or as a note to the interviewer on the questionnaire. Examining the estimated percentage of children who have lost a parent in Figure 1, there does not seem to be any clear indication that surveys that did not mention biological parents produced under-estimates of the rate of orphanhood. The questions on educational attainment were very similar across survey years. In the 1993 PSLSD and the 1995 OHS grades one to three were considered as one category. Children in this category were coded as having completed three years of education. The education of younger children will therefore be biased upwards in these two surveys. It is not clear what effect this will have on estimates of orphan deficits in educational attainment. Orphans in this category who are in grades one and two and who are not at the correct grade for age will be indistinguishable from non-orphans in grade three. On the other hand as the risk of orphanhood increases with age, an over-estimate of educational attainment at younger ages may bias estimates of an orphan deficit upwards (in absolute terms). The estimates of enrolment are substantially lower for the 1996 Census compared to all other surveys. According to the meta-data it appears that some respondents may have thought the question pertained to post-school institutions only due to the ordering of questions.

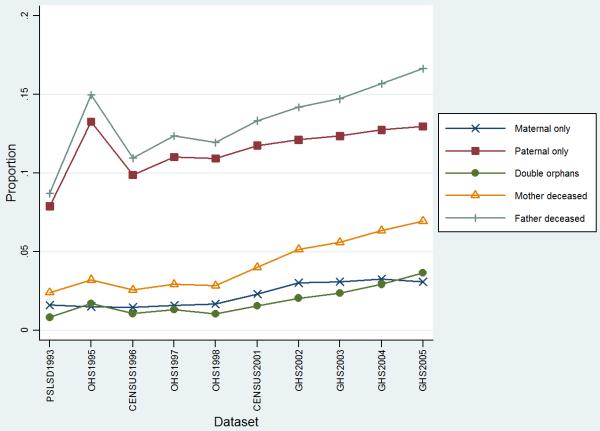

Figure 1.

Parental death by survey for Africans aged 0-17

A maternal orphan is defined as a child whose mother is deceased and whose father is known to be alive, a paternal orphan as a child whose father is deceased and whose mother is known to be alive and a double orphan as a child whose mother and father are both deceased. Single orphans refer collectively to maternal and paternal orphans. Orphans refer to children who have lost at least one parent and non-orphans have two surviving parents. Following Case et al. (2004) we also define a “virtual” double orphan as a child who has lost one parent and does not live with the surviving parent. A foster child has two living parents but does not co-reside with either of them.

In the analyses that follow we focus on African children of school going age. 4 The paper focuses on African children for three reasons. Firstly, HIV prevalence amongst non-Africans is low.5 Secondly while there is growing within race inequality, Africans differ substantially from the other racial groups on a range of socioeconomic indicators that are likely to affect schooling outcomes. Finally response rates for Africans in South African surveys are typically much higher than for other racial groups. All results shown below were replicated for the whole of South Africa with no resulting differences in any of the substantive findings.

Rates of orphanhood

Figure 1 shows for each survey the proportion of African children under the age of 18 who are maternal, paternal and double orphans and those whose mother is deceased and father is deceased. The increase in parental death over the twelve years from 1993 to 2005 is clear - the percentage of children whose mother is deceased has risen from 2.4% to 6.9% and the percentage whose father is deceased has risen from 8.7% to 16.6%. The most recent estimates from 2005 indicate that by the age of 17 over a quarter (29.4%) of children have lost their father, 12.9% have lost their mother and 7.4% are double orphans. It is evident from the graph that the greatest increase has been in the percentage of double orphans which has occurred since 1998. The percentage of children who are maternal, paternal and double orphans has risen by 94%, 64% and 348% respectively. The percentage of children who have lost at least one parent who are double orphans has increased from 7.9% in 1993 to 18.5% in 2005.

There are no data on the cause or timing of parental death so one cannot distinguish AIDS orphans from other orphans. It is not clear how much of the increase in orphanhood can be attributed to HIV/AIDS although the disproportionate increase in the number of double orphans “is largely attributable to the dependency between paternal and maternal mortality that is introduced by AIDS” (Johnson and Dorrington 2001:i).

3. Orphan status, living arrangements, poverty and schooling outcomes

Orphan status and living arrangements

Child headed households will be under-represented in the data as interviewers are typically instructed to interview a knowledgeable adult about the household. Children living on the streets and in institutionalized settings are also excluded by design. The percentage of children living in institutions is negligible. Using the 2001 Census Anderson and Phillips (2006:18) estimate that 1.3% of children aged 0 to 14 live in an institution and that orphans are no more likely to live in an institution than non-orphaned children. Table 1 presents information on the living arrangements of African children aged 8 to 17 for each of the surveys. Non-orphaned children are substantially more likely to be living with their mothers than their fathers and child fostering is common. In the most recent survey (2005) 73% of non-orphans lived with their mother, 41% with their father and nearly a quarter (23%) with neither parent. Only 38% of non-orphans lived with both parents. These child-parent co-residency patterns for non-orphans seem to be fairly stable over the period 1993 to 2005.

Table 1. Living Arrangements of Africans aged 8 to 17 - 1993 to 2005.

| Year | 1993 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset | PSLSD | OHS | CENSUS | OHS | OHS | CENSUS | GHS | GHS | GHS | GHS |

| Observations | 8,059 | 22,858 | 636,977 | 28,494 | 16,376 | 635,914 | 19,805 | 19,092 | 18,353 | 21,296 |

| Children with two living parents | ||||||||||

| Fraction of children | 0.851 | 0.809 | 0.84027 | 0.8174 | 0.8238 | 0.796 | 0.775 | 0.771 | 0.750 | 0.733 |

| Mother is co-resident | 0.757 | 0.812 | 0.589 | 0.730 | 0.726 | 0.735 | 0.727 | |||

| Father is co-resident | 0.451 | 0.581 | 0.365 | 0.433 | 0.423 | 0.421 | 0.413 | |||

| Living with both | 0.424 | 0.561 | 0.313 | 0.401 | 0.389 | 0.389 | 0.380 | |||

| Living with mother only | 0.333 | 0.251 | 0.276 | 0.328 | 0.337 | 0.346 | 0.346 | |||

| Living with father only | 0.027 | 0.020 | 0.052 | 0.032 | 0.034 | 0.032 | 0.032 | |||

| Living with neither | 0.214 | 0.167 | 0.314 | 0.219 | 0.225 | 0.217 | 0.228 | |||

| Relationship to head - child | 0.654 | 0.726 | 0.684 | 0.622 | 0.623 | 0.651 | 0.625 | 0.630 | 0.627 | 0.629 |

| Relationship to head - grandchild | 0.279 | 0.215 | 0.219 | 0.280 | 0.276 | 0.232 | 0.280 | 0.277 | 0.290 | 0.272 |

| Relationship to head - other relative | 0.059 | 0.054 | 0.072 | 0.089 | 0.094 | 0.092 | 0.082 | 0.083 | 0.073 | 0.081 |

| Relationship to head - non-relative | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.010 |

| Relationship to head - self | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.007 |

| Maternal orphans | ||||||||||

| Fraction of children | 0.023 | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.022 | 0.023 | 0.030 | 0.040 | 0.038 | 0.041 | 0.042 |

| Living with father | 0.352 | 0.419 | 0.245 | 0.290 | 0.236 | 0.228 | 0.269 | |||

| Relationship to head - child | 0.349 | 0.325 | 0.372 | 0.314 | 0.315 | 0.260 | 0.249 | 0.197 | 0.192 | 0.217 |

| Relationship to head - grandchild | 0.366 | 0.362 | 0.283 | 0.352 | 0.385 | 0.430 | 0.468 | 0.483 | 0.537 | 0.484 |

| Relationship to head - other relative | 0.242 | 0.161 | 0.177 | 0.276 | 0.242 | 0.252 | 0.238 | 0.275 | 0.227 | 0.237 |

| Relationship to head - non-relative | 0.043 | 0.016 | 0.023 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.016 | 0.010 | 0.015 |

| Relationship to head - adoptive/foster child | 0.132 | 0.123 | 0.035 | 0.035 | 0.026 | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.036 | |

| Relationship to head - self | 0.003 | 0.022 | 0.010 | 0.012 | 0.022 | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.014 | 0.011 | |

| Paternal orphans | ||||||||||

| Fraction of children | 0.112 | 0.152 | 0.128 | 0.141 | 0.137 | 0.148 | 0.154 | 0.155 | 0.163 | 0.168 |

| Living with mother | 0.783 | 0.763 | 0.733 | 0.551 | 0.685 | 0.654 | 0.693 | 0.671 | ||

| Relationship to head - child | 0.692 | 0.587 | 0.590 | 0.538 | 0.552 | 0.515 | 0.503 | 0.503 | 0.533 | 0.524 |

| Relationship to head - grandchild | 0.173 | 0.297 | 0.239 | 0.285 | 0.261 | 0.276 | 0.330 | 0.325 | 0.306 | 0.306 |

| Relationship to head - other relative | 0.073 | 0.097 | 0.122 | 0.139 | 0.158 | 0.152 | 0.133 | 0.150 | 0.131 | 0.130 |

| Relationship to head - non-relative | 0.014 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.012 |

| Relationship to head - adoptive/foster child | 0.047 | 0.014 | 0.038 | 0.023 | 0.016 | 0.033 | 0.018 | 0.009 | 0.017 | 0.019 |

| Relationship to head - self | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.016 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.009 |

| Double orphans | ||||||||||

| Fraction of children | 0.014 | 0.021 | 0.012 | 0.018 | 0.014 | 0.021 | 0.029 | 0.033 | 0.043 | 0.054 |

| Relationship to head - grandchild | 0.433 | 0.435 | 0.384 | 0.426 | 0.511 | 0.500 | 0.540 | 0.539 | 0.553 | 0.512 |

| Relationship to head - other relative | 0.499 | 0.310 | 0.460 | 0.372 | 0.350 | 0.408 | 0.381 | 0.354 | 0.352 | 0.403 |

| Relationship to head - non-relative | 0.037 | 0.039 | 0.014 | 0.003 | 0.017 | 0.019 | 0.024 | 0.017 | 0.016 | |

| Relationship to head - adoptive/foster child | 0.031 | 0.216 | 0.096 | 0.183 | 0.136 | 0.046 | 0.045 | 0.063 | 0.071 | 0.054 |

| Relationship to head - self | 0.061 | 0.005 | 0.030 | 0.015 | 0.020 | 0.008 | 0.014 | |||

| Mother is deceased - maternal and double orphans | ||||||||||

| Fraction of children | 0.037 | 0.040 | 0.030 | 0.040 | 0.038 | 0.053 | 0.070 | 0.073 | 0.085 | 0.098 |

| Fraction who are double orphans | 0.367 | 0.530 | 0.416 | 0.456 | 0.406 | 0.428 | 0.427 | 0.478 | 0.522 | 0.573 |

| Fraction who are “virtual” double orphans | 0.410 | 0.273 | 0.372 | 0.544 | 0.594 | 0.432 | 0.407 | 0.399 | 0.369 | 0.312 |

| Fraction who live with their father | 0.223 | 0.197 | 0.212 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.140 | 0.166 | 0.123 | 0.109 | 0.115 |

| Father is deceased - paternal and double orphans | ||||||||||

| Fraction of children | 0.125 | 0.173 | 0.134 | 0.155 | 0.145 | 0.162 | 0.179 | 0.185 | 0.203 | 0.218 |

| Fraction who are double orphans | 0.108 | 0.121 | 0.067 | 0.089 | 0.054 | 0.091 | 0.141 | 0.162 | 0.193 | 0.232 |

| Fraction who are “virtual” double orphans | 0.193 | 0.208 | 0.933 | 0.911 | 0.946 | 0.408 | 0.270 | 0.290 | 0.248 | 0.253 |

| Fraction who live with their father | 0.699 | 0.670 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.501 | 0.589 | 0.548 | 0.559 | 0.515 |

Children who have lost one parent are less likely than non-orphans to live with the surviving parent and this appears to be increasingly true over time. The percentage of maternal orphans who are “virtual” double orphans increased from 65% in 1993 to 73% in 2005. Paternal orphans are at much lower risk of being “virtual” double orphans but the percentage living with their mother has decreased from 78% in 1993 to 67% in 2005. The difference between children who have lost a mother and those who have lost a father is highlighted by the following categorization. In 2005 57% percent of children whose mother had died were double orphans, 31% are “virtual” double orphans and 12% live with their father. In contrast among children whose father had died, 23% are double orphans, 25% are “virtual” double orphans and 52% are living with their mother.

In 2005 the majority of non-orphans (63%) lived in a household headed by a parent. Twenty seven percent (27%) lived in households headed by a grandparent, 8% lived in a household headed by another relative and 1% in a household headed by a non related person. This pattern in the relationship to the household head for non-orphans has not changed over the 13 year period of this study. The living arrangements of orphans, however, do appear to have shifted over time. There has been a substantial increase in the percentage of maternal, paternal and double orphans living in households headed by a grandparent - the increasing numbers of “virtual” double orphans are mostly accommodated in these households. In 2005 only around 1% of single orphans and 2% of double orphans lived in a household headed by a non-relative and for paternal orphans the mother is co-resident in many of these households.

All this suggests that extended family networks are being asked to accommodate the increasing number of orphans with no increase in the percentage of orphans living in households headed by a non related person.6 However, within the family networks there appear to have been some shifts in the living arrangement of orphans with single parent orphans being less likely to co-reside with the surviving parent and all orphans more likely to live in a household headed by a grandparent. Bicego et al. (2003) document a similar increasing reliance on grandparents in Tanzania, Namibia and Zimbabwe.

Orphan status and economic well-being

Before considering the relationship between orphanhood and schooling we briefly examine the economic well-being of orphans and non-orphaned children. This is contextually important as orphans are not necessarily concentrated in the poorest households. The empirical evidence for sub-Saharan Africa on the relationship between orphanhood and poverty is mixed and results tend to differ for maternal and paternal deaths (Ainsworth and Filmer 2006, Bicego et al. 2003, Case et al. 2004, Case and Ardington 2006).

The relationship between parental death and household economic well-being is investigated in Table 2. Indicators that the child’s mother/father is deceased are regressed on a range of measures of economic well-being. These include expenditure per capita, access to piped water, access to a hygienic toilet and electricity from the main supply. The regressions control for the child’s age using a full set of dummy variables and include an indicator for gender.

Table 2.

Orphanhood and household socio-economic status

| Dataset | Mother deceased | Father deceased | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A electricity | ||||

| PSLSD1993 | −0.019 | (0.032) | −0.042 | (0.022) |

| OHS1995 | −0.034 | (0.023) | −0.03 | (0.015)* |

| CENSUS1996 | 0.009 | (0.004)** | −0.045 | (0.002)** |

| OHS1997 | 0.001 | (0.021) | −0.054 | (0.013)** |

| OHS1998 | 0.024 | (0.022) | −0.04 | (0.012)** |

| CENSUS2001 | 0.009 | (0.003)** | −0.044 | (0.002)** |

| GHS2002 | 0.01 | (0.019) | −0.057 | (0.014)** |

| GHS2003 | 0.003 | (0.02) | −0.045 | (0.015)** |

| GHS2004 | 0.036 | (0.019) | −0.039 | (0.015)** |

| GHS2005 | 0.015 | (0.017) | −0.036 | (0.015)* |

| Panel B logarithm of per capita expenditure | ||||

| PSLSD1993 | −0.071 | (0.064) | −0.145 | (0.038)** |

| OHS1995 | 0.04 | (0.041) | −0.227 | (0.027)** |

| CENSUS1996 | 0.139 | (0.022)** | −0.653 | (0.012)** |

| OHS1997 | 0.005 | (0.039) | −0.14 | (0.022)** |

| OHS1998 | −0.088 | (0.035)* | −0.112 | (0.021)** |

| CENSUS2001 | 0.123 | (0.014)** | −0.459 | (0.009)** |

| GHS2002 | −0.09 | (0.033)** | −0.18 | (0.027)** |

| GHS2003 | 0.005 | (0.036) | −0.246 | (0.027)** |

| GHS2004 | −0.059 | (0.033) | −0.229 | (0.027)** |

| GHS2005 | 0.005 | (0.032) | −0.232 | (0.032)** |

| Panel C piped water | ||||

| PSLSD1993 | −0.027 | (0.039) | −0.038 | (0.026) |

| OHS1995 | −0.023 | (0.024) | −0.035 | (0.015)* |

| CENSUS1996 | 0.016 | (0.003)** | −0.047 | (0.002)** |

| OHS1997 | 0.043 | (0.022)* | −0.066 | (0.013)** |

| OHS1998 | 0.053 | (0.022)* | −0.057 | (0.012)** |

| CENSUS2001 | 0.011 | (0.003)** | −0.053 | (0.002)** |

| GHS2002 | 0.004 | (0.02) | −0.065 | (0.014)** |

| GHS2003 | 0.024 | (0.021) | −0.069 | (0.015)** |

| GHS2004 | 0.009 | (0.021) | −0.028 | (0.015) |

| GHS2005 | 0.061 | (0.020)** | −0.051 | (0.015)** |

| Panel D toilet | ||||

| PSLSD1993 | 0.002 | (0.037) | −0.019 | (0.023) |

| OHS1995 | −0.013 | (0.024) | −0.037 | (0.015)* |

| CENSUS1996 | −0.008 | (0.003)** | −0.036 | (0.002)** |

| OHS1997 | 0.052 | (0.022)* | −0.014 | (0.013) |

| OHS1998 | 0.006 | (0.022) | −0.016 | (0.012) |

| CENSUS2001 | 0.017 | (0.003)** | −0.034 | (0.002)** |

| GHS2002 | 0.009 | (0.019) | −0.037 | (0.014)** |

| GHS2003 | 0.031 | (0.021) | −0.041 | (0.015)** |

| GHS2004 | −0.027 | (0.019) | −0.03 | (0.014)* |

| GHS2005 | −0.003 | (0.019) | −0.037 | (0.016)* |

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%

Each row presents selected coefficients and standard errors in parentheses from a single regression.

A full set of indicators for age, an indicator for sex and indicators that parents’ vital status is missing included in all regressions.

These regressions indicate a strong relationship between paternal death and economic well-being. Children whose fathers are deceased are significantly more likely to live in households without access to electricity, piped water and hygienic toilets and with significantly lower per capita expenditure. Children whose mothers have died do not live in households that are systematically richer or poorer than other children’s households. These findings for paternal and maternal deaths are very similar to those of Case et al. (2004), Ainsworth and Filmer (2006) and Case and Ardington (2006). There does not appear to be any evidence of a systematic improvement or deterioration over time in the economic well-being of households in which orphans live relative to non-orphans’ households.

If children are fostered into better resourced households in an extended family network then one may over-estimate the impact of orphanhood when comparing them to children with whom they live. We find no evidence that households that take in orphans are systematically better off. Following Case et al. (2004) we refer to households with both orphans and non-orphans as “blended” households. “Blended” households are significantly larger (by about two members) and have lower well-being, on all measures than non-“blended” households. These “blended” households will enable us to compare outcomes for orphans to those of non-orphaned children with whom they live.

The next section turns to examine our key research question; the vulnerabilities of orphans with respect to educational outcomes.

Orphan status and schooling

Under apartheid educational institutions were racially segregated and “all aspects of education - governance, funding, professional training and curriculum - were defined and operated along racial lines in an egregiously unequal manner (Fiske and Ladd 2004:3).” Despite substantial equalization of government budget allocation by race in the post-apartheid era, major racial disparities in the quantity and particularly the quality of education persist. Post-apartheid education policy has given school governing bodies considerable latitude in setting school fees with the results that more affluent communities supplement school resources and privately employ more teachers. In addition to school fees, sending a child to school generally entails expenses for books, stationery, uniforms and often transport. These other expenses can be considerable.7

The South African Schools Act of 1996 made schooling compulsory from the ages of 7 to 15. While there is some evidence of delays in starting school, enrolment is almost universal in this age group. Over the period 1993 to 2005 enrolment rates among African children aged 8 to 17 remained fairly constant at around 92 to 95%. Despite this high enrolment, there are large and persistent racial and socio-economic gaps in educational attainment driven primarily by high rates of grade repetition amongst Africans (Anderson et al. 2001, Lam et al. 2007). The rate of progression through school for African children aged 8 to 17 has increased from around 0.74 grades per year in 1996 to around 0.85 grades per year in 2005. Enrolment among Africans remains high into the late teens but students do begin to drop out before completing their secondary schooling. In 2005 for example, 16% of 16 to 18 year olds who had not completed secondary school were not enrolled. Case and Ardington (2006:417) distinguish between “a child’s educational “stock” (years of completed education) and educational “flow” (enrolment and current spending on children’s schooling).” Given that the South African schooling system is characterised by high enrolment and high rates of grade repetition we look at both enrolment and grades completed in the analyses that follow.

Parent’s vital status is missing for a number of cases. The regressions that follow include an indicator that the parent’s vital status is missing and the orphan status indicators are set to zero. We experimented with a variety of approaches to missing data and found that results were robust with all specifications generating negative estimates of the association between parental death and schooling.8 The regressions include separate indicators for maternal and paternal deaths as the literature suggests that there are different effects for the death of a mother relative to the death of a father.

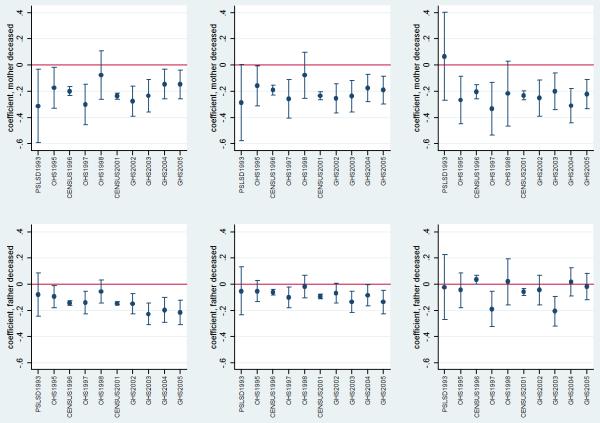

Figure 2 shows coefficient estimates and 95% confidence intervals for regressions of years of completed education on indicators that the child’s mother and father are deceased for African children aged 8 to 17. The sample is restricted to children aged 8 and older as there have been small changes in the age of admission in the period under study and in all surveys these children should have completed at least 1 year of education if they were making normal progress at school. The first column controls for the child’s sex and age using a full set of age dummies. The second column includes the following household controls: age, sex and education level of the household head, indicators for each of 9 provinces, an indicator that the area is urban, logarithm of per capita household expenditure, indicators that the household has a hygienic toilet facility, access to piped water and electricity, the logarithm of household size, the fraction of residents who are less than 14 years old and indicators that there is at least one female/male resident who is age eligible for the social pension. The third column estimates household fixed effects. Coefficients for maternal and paternal death are presented in the first and second row respectively of Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Coefficient estimates and 95% confidence intervals from regressions of years of completed education on indicators that mother and father are deceased for Africans aged 8-17

Starting with the first column we find that for all surveys other than the 1998 OHS there is a significant negative effect of maternal death. 9 The point estimates of the deficit range from 0.15 to 0.31 of a year less completed education than children of the same age and sex whose mothers are alive. The un-weighted average deficit is 0.21. There does not appear to be any clear trend in this deficit over time. Children whose father has died are also at a significant disadvantage with respect to educational attainment although the average magnitude of the deficit (0.14) is slightly lower than that for a maternal death. As with maternal deaths, there does not appear to be any clear evidence of systematic deterioration or improvement in the deficit that children who have lost their father face with respect to educational attainment.

The next two columns of Figure 2 investigate how much of this disadvantage is driven by poverty and whether orphans are at greater disadvantage than other poor children. The second column introduces controls for household characteristics with the result that the coefficients on paternal death are substantially reduced (the average coefficient drops from 0.14 to 0.079) while the results for maternal death are not affected. Around half of the disadvantage associated with paternal death is accounted for by the socio-economic conditions of the household. One cannot distinguish between an indirect causal effect of paternal death on schooling outcomes operating through economic status and a spurious correlation between paternal death, household poverty and schooling. Without longitudinal data one also cannot estimate whether a maternal death has a causal effect on the child’s schooling but the results do suggest that maternal death is directly associated with poorer schooling outcomes rather than being channelled through socio-economic status.

Over a quarter of orphans and 12% of non-orphans live in “blended” households. This enables us to move beyond comparing orphans to children of similar socio-economic status to comparing orphans to non-orphans within the same household. Household fixed effect models allow us to examine whether there are intra-household differences and avoid empirical problems associated with the mis-measurement of household characteristics. The third column of Figure 2 presents estimates from household fixed effects models. The coefficient for maternal death remains unchanged suggesting that on average children whose mothers have died have completed 0.22 years less education than the children with whom they live whose mothers are alive. The coefficient is significant at the 5% level or better for all surveys other than the 1993 PSLSD and the 1998 OHS (significant at the 10% level). The coefficient on paternal death is further diminished (the average coefficient is 0.051) and is statistically significant in only 3 surveys.

In order to assess whether the effect of losing both parents is merely equal to the additive effect of losing a mother and a father an interaction term between the maternal and paternal death indicators was included in the regressions. Table 3 presents estimated coefficients and standard errors for the maternal and paternal death indicators and the interaction between them. The interaction term is insignificant with and without household controls and in the fixed effect models suggesting that the simpler specification without the interaction term adequately captures the effect of parental death on schooling. This may be due to the fact that almost ninety percent of children whose mother has died are either double orphans or “virtual” double orphans. Parental death is relatively rare, which often results in insufficient statistical precision to reliably estimate effects especially when one includes interactions to examine whether effects are homogenous among all orphans. We therefore do not distinguish between paternal, maternal and double orphans but prefer the simpler specification of maternal death and paternal death for most of the analyses that follow.

Table 3. Educational attainment of Africans aged 8 to 17. Interaction between maternal and paternal death.

| Dataset | Mother deceased | Father deceased | Double orphan | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A - No household controls | ||||||

| PSLSD1993 | −0.188 | (0.152) | −0.052 | (0.09) | −0.356 | (0.296) |

| OHS1995 | −0.122 | (0.109) | −0.087 | (0.045) | −0.102 | (0.153) |

| CENSUS1996 | −0.189 | (0.021)** | −0.141 | (0.009)** | −0.025 | (0.036) |

| OHS1997 | −0.348 | (0.100)** | −0.147 | (0.045)** | 0.115 | (0.156) |

| OHS1998 | −0.107 | (0.109) | −0.061 | (0.046) | 0.097 | (0.187) |

| CENSUS2001 | −0.235 | (0.014)** | −0.143 | (0.007)** | −0.015 | (0.025) |

| GHS2002 | −0.276 | (0.070)** | −0.151 | (0.043)** | 0.026 | (0.114) |

| GHS2003 | −0.186 | (0.078)* | −0.217 | (0.046)** | −0.085 | (0.128) |

| GHS2004 | −0.161 | (0.072)* | −0.202 | (0.053)** | 0.036 | (0.114) |

| GHS2005 | −0.227 | (0.073)** | −0.24 | (0.051)** | 0.16 | (0.108) |

| Panel B - Household controls | ||||||

| PSLSD1993 | −0.136 | (0.158) | −0.015 | (0.097) | −0.485 | (0.339) |

| OHS1995 | −0.112 | (0.108) | −0.044 | (0.044) | −0.092 | (0.152) |

| CENSUS1996 | −0.134 | (0.021)** | −0.059 | (0.009)** | −0.114 | (0.036)** |

| OHS1997 | −0.272 | (0.091)** | −0.093 | (0.043)* | 0.017 | (0.146) |

| OHS1998 | −0.032 | (0.106) | 0 | (0.045) | −0.149 | (0.18) |

| CENSUS2001 | −0.218 | (0.015)** | −0.092 | (0.007)** | −0.051 | (0.026)* |

| GHS2002 | −0.202 | (0.068)** | −0.052 | (0.041) | −0.114 | (0.107) |

| GHS2003 | −0.162 | (0.076)* | −0.115 | (0.044)** | −0.152 | (0.12) |

| GHS2004 | −0.148 | (0.069)* | −0.072 | (0.045) | −0.062 | (0.108) |

| GHS2005 | −0.226 | (0.071)** | −0.149 | (0.047)** | 0.08 | (0.103) |

| Panel C - Household fixed effects | ||||||

| PSLSD1993 | 0.389 | (0.2) | 0.124 | (0.135) | −0.992 | (0.355)** |

| OHS1995 | −0.209 | (0.135) | −0.026 | (0.076) | −0.127 | (0.195) |

| CENSUS1996 | −0.082 | (0.034)* | 0.063 | (0.018)** | −0.306 | (0.051)** |

| OHS1997 | −0.231 | (0.131) | −0.14 | (0.070)* | −0.149 | (0.197) |

| OHS1998 | −0.302 | (0.149)* | 0.088 | (0.091) | −0.016 | (0.246) |

| CENSUS2001 | −0.191 | (0.021)** | −0.042 | (0.014)** | −0.108 | (0.034)** |

| GHS2002 | −0.324 | (0.085)** | −0.08 | (0.061) | 0.196 | (0.137) |

| GHS2003 | −0.212 | (0.089)* | −0.236 | (0.064)** | −0.117 | (0.137) |

| GHS2004 | −0.116 | (0.086) | 0.115 | (0.062) | −0.38 | (0.125)** |

| GHS2005 | −0.194 | (0.080)* | −0.044 | (0.056) | −0.015 | (0.116) |

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%.

Each row presents selected coefficients and standard errors in parentheses from a single regression.

A full set of indicators for age, and indicator for sex and indicators that parents’ vital status is missing included in all regressions.

The primary objective of this paper is to document the extent to which the vulnerability of orphans to poorer educational outcomes is changing over time. We have shown in Figure 2 that when we estimate orphan deficits for each survey separately we consistently find evidence that orphans are at risk for poorer educational outcomes. We now run the same regressions using pooled samples. Pooling improves statistical precision and also allows for easier identification of any trends in the data. Looking back to Figure 1, rates of orphanhood and particularly double orphanhood were fairly flat in the 1980s and then rose substantially after 1998. Data were pooled to create a 1993 to 1998 sample and a 2002 to 2005 sample. Weights in each survey were scaled to sum to one so that within each pooled sample each survey receives equal weight. Expenditures were inflated to 2005 Rands and indicators for the year of the survey were included in all regressions. Table 4 presents estimates analogous to those in Figure 2 for two pooled samples and the 2001 Census. Each row in Table 4 presents selected coefficients and their standard errors from a single regression model. As with Figure 2 we estimate models with individual level controls only (Panel A), individual and household level controls (Panel B) and household fixed effects models with individual level controls (Panel C).

Table 4. Educational attainment of Africans aged 8 to 17.

| Mother deceased | Father deceased | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A - No household controls | ||||

| 1993 to 1998 | −0.221 | (0.037)** | −0.104 | (0.019)** |

| 2001 | −0.236 | (0.012)** | −0.143 | (0.007)** |

| 2002 to 2005 | −0.189 | (0.025)** | −0.197 | (0.019)** |

| Panel B - Household controls | ||||

| 1993 to 1998 | −0.209 | (0.038)** | −0.065 | (0.020)** |

| 2001 | −0.241 | (0.014)** | −0.092 | (0.009)** |

| 2002 to 2005 | −0.203 | (0.025)** | −0.104 | (0.018)** |

| Panel C - Household fixed effects | ||||

| 1993 to 1998 | −0.196 | (0.020)** | −0.008 | (0.014) |

| 2001 | −0.232 | (0.017)** | −0.059 | (0.013)** |

| 2002 to 2005 | −0.239 | (0.033)** | −0.069 | (0.027)* |

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%

Each row presents selected coefficients and standard errors in parentheses from a single regression.

A full set of indicators for age, an indicator for sex and indicators that parents’ vital status is missing included in all expressions.

Starting with Panel A we see a slight, although not significant, decrease in the effect of maternal death. As with the results for each survey individually, adding household controls (panel B) has very little effect on the maternal death coefficients. There is a slight decrease in the coefficient for the earlier sample and a slight increase for the two more recent samples when household controls are included. The magnitude of the gap in schooling attainment between children who have lost their mother and other children with whom they live whose mothers are alive (panel C) has increased slightly over the period under study.

Changes for paternal death effects in Panel A are more marked than for maternal deaths. The deficit in grades completed increases from 0.104 in the first sample to 0.197 in the most recent sample. Estimates for paternal death without household controls are actually slightly larger than for maternal death in the most recent sample. The coefficients on paternal death are greatly reduced however when household controls are added. The household fixed effect estimates for father’s deaths are further diminished. Compared to other children with whom they live children who have lost a father are on average only 0.07 years behind in school. In the regressions that control for household socio-economic status and the household fixed effects models the effect of paternal deaths, although small, does appear to increase between 1993 and 2005.

The pooled data are helpful in summarising effects across surveys and in identifying any trends in the data. The estimates from each survey are also useful in that they give a sense of the consistency of findings. Looking back at Figure 2, conclusions about the association between orphanhood and educational attainment could vary considerably depending on the survey selected, highlighting the advantage of having multiple observations over time to build a comprehensive picture of orphan vulnerabilities.

We now turn our attention away from educational attainment to enrolment. Estimates of the effect of parental death on enrolment for the pooled samples and the 2001 Census are shown in Table 5. As with the previous table, each row presents selected coefficients and their standard errors from a single regression model. Panel A presents results for models with only individual level controls, Panel B also includes household control and Panel C presents estimates from household fixed effects models. The first two columns show results for African children aged 7 to 15 - the age group for whom schooling is compulsory. There is very close to universal enrolment in this age group and as expected effects of parental death are small. Estimates for maternal and paternal death in models with and without household controls are always negative but are significant only in 4 and 5 of the individual surveys (results not shown) for maternal and paternal deaths respectively. There are small but significant deficits in enrolment for paternal deaths in 6 of the household fixed effects regressions. Maternal death deficits are only significant for 3 surveys. Children whose mothers are deceased are on average 2 percentage points less likely to attend school while those who have lost fathers are 1 percentage point less likely to attend school. Enrolment deficits for maternal deaths have halved between the first and last pooled sample. This is consistently so across models without household controls, models with household controls and household fixed effect models. Enrolment deficits for paternal deaths appear to be fairly consistent over time although they are insignificantly different from zero in the most recent sample for the household fixed effects model.

Table 5. Enrolment.

| (1) | (2) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africans aged 7 to 15 | Africans aged 16 to 18 without Grade 12 | |||||||

| Mother deceased | Father deceased | Mother deceased | Father deceased | |||||

| Panel A - No household controls | ||||||||

| 1993 to 1998 | −0.023 | (0.005)** | −0.009 | (0.003)** | −0.065 | (0.013)** | −0.034 | (0.007)** |

| 2001 | −0.026 | (0.002)** | −0.013 | (0.001)** | −0.065 | (0.004)** | −0.046 | (0.002)** |

| 2002 to 2005 | −0.011 | (0.003)** | −0.011 | (0.002)** | −0.035 | (0.011)** | −0.043 | (0.007)** |

|

Panel B - Household controls |

||||||||

| 1993 to 1998 | −0.023 | (0.006)** | −0.01 | (0.003)** | −0.048 | (0.013)** | −0.04 | (0.007)** |

| 2001 | −0.019 | (0.002)** | −0.01 | (0.001)** | −0.053 | (0.005)** | −0.046 | (0.003)** |

| 2002 to 2005 | −0.009 | (0.003)** | −0.009 | (0.002)** | −0.036 | (0.010)** | −0.035 | (0.008)** |

| Panel C - Household fixed effects | ||||||||

| 1993 to 1998 | −0.026 | (0.003)** | −0.019 | (0.002)** | −0.086 | (0.011)** | −0.054 | (0.008)** |

| 2001 | −0.023 | (0.003)** | −0.011 | (0.002)** | −0.032 | (0.010)** | −0.031 | (0.008)** |

| 2002 to 2005 | −0.012 | (0.003)* | −0.004 | (0.004) | 0.029 | (0.022) | −0.035 | (0.019) |

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%

Each row presents selected coefficients and standard errors in parenthesis from a single regression.

A full set of indicators for age, an indicator for sex and indicators that parents’ vital status is missing included in all expressions.

The third and fourth column of Table 5 examines enrolment for children aged 16 to 18 who have not yet completed secondary school. Generally, parental death is seen to put late teens at risk of dropping out of school before completion of Grade 12. For models with household controls the maternal death coefficients are significantly negative in 7 out of the 10 surveys and the average deficit is 4.4 percentage points. Paternal death also has significant negative effects in 8 of the 10 surveys with an average deficit of 3.8 percentage points. The average estimated deficits do not change in the household fixed effects models but estimates are now significantly different from zero in only 4 of the surveys for both maternal and paternal death. In contrast to the results for attainment paternal death effects on enrolment do not seem to be explained by household socio-economic status although the magnitude of effects is small. The trends over time for children aged 16 to 18 are similar to those observed for 7 to 15 year olds. The disadvantage in enrolment associated with maternal death appears to have declined considerably and in the household fixed effects model the estimate ranges from a deficit of 8.9 percentage point to an advantage of 3.3 percentage points (although this advantage is not statistically significant). The trend for paternal deaths is less clear although the household fixed effect estimates have declined from 5.4 percentage points in the earliest sample to 3.8 percentage points in the most recent sample.

Figure 2 and Tables 4 and 5 show orphans to have poorer educational outcomes throughout the period under study. Before concluding we turn our attention to the increasing number of non-orphaned children who live with orphans and consider the interaction of parental death and parental absence.

The effect on orphanhood on other children in the household

The household fixed effects models shown in Figure 2 and Tables 4 and 5 allow us to investigate intra-household differences and to side-step empirical problems around mis-measurement of household socioeconomic status. One is however restricted to comparing orphans to children with whom they currently live. This may result in an over or under estimation of the effect of parental death on schooling outcomes. To the extent that children are fostered into the better off households within a family network orphan effects may be over estimated. Alternatively, if the education of all children in a household suffers when the household absorbs orphans the effect of parental death may be hidden. The percentage of non-orphaned children living in “blended” households has more than doubled between 1993 and 2005. To investigate the effect on children in households that absorb orphans we regressed educational attainment on interactions between orphan status indicators and indicators that the child lives in a “blended” household. Specifically, with respect to mother’s status children were divided into five mutually exclusive categories namely; mother’s vital status unknown, mother deceased and child lives with other children whose mother is alive, mother deceased and child does not live with other children whose mother is alive, mother alive and child lives with other children whose mother is deceased and mother alive and child does not live with other children whose mother is deceased. Similarly, children were divided into five mutually exclusive categories with respect to their father’s status. Results are presented in Table 6 for each survey and the two pooled samples with the last group for both mothers and fathers being the omitted categories. There is no evidence that children whose mother is alive are at any particular disadvantage if they live in a household with children whose mother is deceased. The evidence on the effect of living with children whose father is deceased is more mixed. In five of the surveys they are significantly behind children with living fathers in non-“blended” households. This result is consistent with Case and Ardington’s (2006) findings that paternal death was a marker for lower socioeconomic status. There does not appear to be any systematic change in the effect of living with orphans over time. We tested for significant differences between orphans in “blended” and non-“blended” households and between orphans and non-orphans in “blended” households. There is no consistent evidence that outcomes for orphans differ if they live in “blended” or non-“blended” households.

Table 6. Educational attainment of Africans aged 8 to 17. “Blended” and non -“blended” households.

| Dataset | Mother deceased -blend | Mother deceased - non blend |

Father deceased - blend |

Father deceased - non blend |

Mother alive - blend |

Father alive- blend | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSLSD1993 | 0.175 | (0.22) | −0.533 | (0.185)** | −0.007 | (0.196) | −0.041 | (0.101) | 0.010 | (0.151) | 0.137 | (0.129) |

| OHS1995 | −0.254 | (0.114)* | −0.091 | (0.102) | −0.071 | (0.074) | −0.054 | (0.049) | −0.031 | (0.1) | −0.067 | (0.071) |

| CENSUS1996 | −0.224 | (0.031)** | −0.166 | (0.024)** | −0.098 | (0.019)** | −0.057 | (0.011)** | −0.016 | (0.023) | −0.115 | (0.015)** |

| OHS1997 | −0.294 | (0.121)* | −0.230 | (0.093)* | −0.257 | (0.076)** | −0.044 | (0.048) | −0.166 | (0.095) | −0.102 | (0.062) |

| OHS1998 | −0.293 | (0.119)* | 0.121 | (0.12) | −0.154 | (0.083) | 0.022 | (0.05) | 0.025 | (0.095) | −0.188 | (0.077)* |

| CENSUS2001 | −0.241 | (0.021)** | −0.234 | (0.018)** | −0.152 | (0.015)** | −0.081 | (0.010)** | −0.009 | (0.016) | −0.101 | (0.013)** |

| GHS2002 | −0.275 | (0.078)** | −0.235 | (0.078)** | −0.047 | (0.063) | −0.069 | (0.048) | −0.090 | (0.075) | 0.025 | (0.062) |

| GHS2003 | −0.246 | (0.090)** | −0.189 | (0.079)* | −0.243 | (0.071)** | −0.1 | (0.048)* | −0.002 | (0.075) | −0.047 | (0.061) |

| GHS2004 | −0.206 | (0.079)** | −0.138 | (0.071) | 0.005 | (0.065) | −0.141 | (0.051)** | 0.103 | (0.074) | −0.127 | (0.058)* |

| GHS2005 | −0.173 | (0.076)* | −0.178 | (0.070)* | −0.158 | (0.081) | −0.16 | (0.050)** | 0.092 | (0.064) | −0.201 | (0.062)** |

| Average | −0.203 | −0.187 | −0.118 | −0.073 | −0.008 | −0.079 | ||||||

| 1993 to 1998 | −0.243 | (0.058)** | −0.173 | (0.049)** | −0.128 | (0.037)** | −0.048 | (0.022)* | −0.040 | (0.042) | −0.065 | (0.029)* |

| 2002 to 2005 | −0.209 | (0.030)** | −0.185 | (0.042)** | −0.100 | (0.024)** | −0.145 | (0.025)** | −0.011 | (0.023) | −0.067 | (0.019)** |

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%.

Each row presents selected coefficients and standard errors in parentheses from a single regression.

Individual level and household controls and indicators that parents vital status is missing included in all regressions.

Parental death and parental presence

Table 7 presents selected coefficients and standard errors from regressions that allow for the interaction between parents’ vital and residency status. Children are divided into five mutually exclusive categories - children with two living parents who co-reside with at least one parent, foster children, single orphans who co-reside with the surviving parent, “virtual” double orphans and double orphans.

Table 7. Educational attainment of Africans aged 8 to 17. Parent’s vital status and residency.

| Dataset | Foster child | Single orphan living with surviving parent |

“Virtual” double orphan |

Double orphan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A - No household controls | ||||||||

| PSLSD1993 | −0.177 | (0.070)* | −0.128 | (0.098) | −0.077 | (0.132) | −0.635 | (0.244)** |

| OHS1995 | −0.216 | (0.043)** | −0.026 | (0.046) | −0.39 | (0.088)** | −0.347 | (0.106)** |

| CENSUS2001 | −0.122 | (0.006)** | −0.134 | (0.009)** | −0.26 | (0.009)** | −0.432 | (0.020)** |

| GHS2002 | −0.218 | (0.036)** | −0.137 | (0.050)** | −0.378 | (0.053)** | −0.451 | (0.086)** |

| GHS2003 | −0.155 | (0.041)** | −0.158 | (0.056)** | −0.375 | (0.057)** | −0.524 | (0.097)** |

| GHS2004 | −0.144 | (0.040)** | −0.211 | (0.063)** | −0.245 | (0.059)** | −0.358 | (0.076)** |

| GHS2005 | −0.179 | (0.042)** | −0.216 | (0.056)** | −0.373 | (0.061)** | −0.349 | (0.071)** |

| Average | −0.173 | −0.144 | −0.300 | −0.442 | ||||

| Panel B - Household controls | ||||||||

| PSLSD1993 | −0.21 | (0.076)** | −0.092 | (0.1) | −0.134 | (0.172) | −0.697 | (0.291)* |

| OHS1995 | −0.127 | (0.043)** | 0.007 | (0.046) | −0.302 | (0.083)** | −0.279 | (0.104)** |

| CENSUS2001 | −0.084 | (0.007)** | −0.063 | (0.011)** | −0.203 | (0.012)** | −0.413 | (0.024)** |

| GHS2002 | −0.12 | (0.036)** | −0.06 | (0.049) | −0.218 | (0.052)** | −0.405 | (0.081)** |

| GHS2003 | −0.035 | (0.042) | −0.065 | (0.056) | −0.236 | (0.054)** | −0.442 | (0.093)** |

| GHS2004 | −0.048 | (0.039) | −0.07 | (0.053) | −0.144 | (0.057)* | −0.296 | (0.076)** |

| GHS2005 | −0.117 | (0.042)** | −0.139 | (0.052)** | −0.285 | (0.058)** | −0.33 | (0.071)** |

| Average | −0.106 | −0.069 | −0.217 | −0.409 | ||||

| Panel C - Household fixed effects | ||||||||

| PSLSD1993 | −0.202 | (0.083)* | 0.16 | (0.163) | 0.06 | (0.164) | −0.566 | (0.282)* |

| OHS1995 | −0.149 | (0.065)* | −0.091 | (0.087) | −0.154 | (0.098) | −0.412 | (0.131)** |

| CENSUS2001 | −0.195 | (0.011)** | −0.038 | (0.02) | −0.26 | (0.015)** | −0.441 | (0.026)** |

| GHS2002 | −0.145 | (0.054)** | −0.164 | (0.079)* | −0.273 | (0.069)** | −0.262 | (0.104)* |

| GHS2003 | −0.196 | (0.056)** | −0.201 | (0.084)* | −0.351 | (0.070)** | −0.627 | (0.103)** |

| GHS2004 | −0.202 | (0.056)** | 0.165 | (0.079)* | −0.179 | (0.070)* | −0.454 | (0.088)** |

| GHS2005 | −0.009 | (0.051) | 0.088 | (0.074) | −0.227 | (0.064)** | −0.26 | (0.077)** |

| Average | −0.157 | −0.012 | −0.198 | −0.432 | ||||

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%.

Each row presents selected coefficients and standard errors in parentheses from a single regression.

A full set of indicators for age, an indicator for sex and indicators that parents’ vital status is missing included in all regressions. Reference category is a child with two living parents co-residing with at least one parent.

From the table it can be seen that, single orphans who live with the surviving parent are only at a small disadvantage once the household’s socio-economic status is taken into account. Foster children fare significantly worse than non-orphaned children who co-reside with at least one parent and results are not affected by controlling for socio-economic status. Foster children are however at less of a disadvantage than “virtual” double orphans who in turn are better off than double orphans. On average double orphans have completed around 0.43 fewer years of education than non-orphaned children who co-reside with at least one of their parents. Given the disadvantage to being a “virtual” double orphan it is interesting that, despite an increase in the percentage of single orphans who are “virtual” double orphans, we do not see an increase in the vulnerability of orphans to poorer educational outcomes over time. In general, the results support an interpretation that parental absence has a detrimental effect on children’s schooling but that living parents are able to exert some influence through, for example, the provision of financial and emotional support.

Spatial variation in the vulnerability of orphans

Overall the results in this paper provide no evidence of a systematic deterioration in orphan schooling deficits across time. Orphan vulnerabilities may however vary across space. If family support networks are indeed struggling to cope in the face of ever-increasing numbers of orphans one may expect that orphans would fare worse in areas with higher concentrations of orphans. We regressed educational attainment on interactions between orphan status indicators with the percentage of orphans by rural/urban location within each province (results not shown). There is no evidence that orphans fare significantly worse in communities with higher orphan rates.

4. Conclusion

This paper has presented a wealth of empirical information on orphans and educational attainment and enrollment. At every point in time cross-sectional evidence suggests that that orphans are at risk of poorer educational outcomes with maternal deaths generally having stronger negative effects than paternal deaths. Paternal deaths are strongly associated with poorer socio-economic status and much of the deficit experienced by children who have lost a father is explained by the relative poverty of their current household. In contrast maternal deaths appear to be directly associated with poorer schooling outcomes rather than channeled through socio-economic status. Among the multiple pathways through which parental death affects a child’s schooling the results in this paper suggest that parental involvement and relatedness to the household are important.

Despite a significant increase in the number of orphans over the last decade we find no evidence of a systematic deterioration over time in traditional coping strategies with respect to orphan’s educational outcomes. Analysis of spatial variation in the vulnerability of orphans also suggests that orphans fare no worse in communities with higher concentrations of orphans. Patterns of care giving for orphans do appear to be shifting over time but these changes are taking place within the extended family safety net. Orphans are still absorbed into extended families but single orphans are increasingly less likely to live with the surviving parent and there is an increasing reliance on grandparents as caregivers. Thus, the family safety net has continued to adjust and to cope. These findings are similar to those of Fortson (2007) and Evans and Miguel (2007: 49) who conclude “that recent claims in the popular media that social networks in rural Africa are rapidly breaking down under the strain of HIV/AIDS deaths - and that as a result, neither orphans nor other children can be adequately taken care of by surviving relatives - are probably overstated.”

However, this in no way diminishes the fact that there has been increased pressure on this safety net and we are not arguing that there is no tipping point. Indeed, within the limits of an analysis of repeated cross-sections, we have demonstrated ongoing adjustments of the safety net. Although HIV prevalence in South Africa is already high the rates of orphanhood are expected to continue to rise until 2015 thereby placing additional strain on the extended family safety net. Ongoing monitoring of the vulnerability of orphans to poor outcomes is essential as the AIDS crisis further deepens.

Without longitudinal data we cannot identify whether there is a causal effect of parental death and we are only ever able to control for concurrent household characteristics. There are no nationally representative longitudinal datasets nor do any national surveys address spatial mobility and family networks in sufficient detail for us to examine which children move following the death of a parent or whether indeed orphans are strategically placed in the better off households within a family network. All of the cross-sectional results in this paper are entirely consistent with and of a similar magnitude to those of Case and Ardington (2006) who use data from a large longitudinal study in northern KwaZulu-Natal. They use the timing of mothers’ deaths and employ individual fixed effects models to argue that these deaths have a causal effect on children’s education. They find that the correlation between father’s deaths and children’s schooling outcomes appear to be driven entirely by their link to household socio-economic status. The consistency of results between both papers suggest that Case and Ardington’s findings are generalizable beyond their field site and that the biases introduced by comparing orphans to children with whom they currently live are not substantial.

The South African government responded to the growing orphanhood crisis by launching a Policy Framework and National Action Plan for orphans and other children affected by HIV/AIDS in 2005. Within this framework, the policies and programmes most pertinent to the schooling of orphans are social assistance through cash grants and school fee exemptions. Ardington (2008) provides a detailed discussion of these policies and the problems orphans face in accessing these social grants. Social assistance through cash grants and fee exemptions are more likely to have a direct effect on enrolment than attainment. However, the magnitude of enrolment deficits relative to gaps in educational attainment presented in this paper suggests that attendance is less of an issue than performance at school. For older children parental loss has a larger impact on enrolment but these children are excluded from the cash grant most widely available to children and the newly introduced No-Fees Schools policy. It seems clear then that in the South African context appropriate policies to address orphan deficits depend importantly on the mechanisms through which orphanhood affects performance in school. More research is needed to understand these multiple pathways in order to ensure that government policies effectively target orphans and reduce their risk of poor schooling outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Ardington and Leibbrandt acknowledge funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Development and the National Institute of Aging R01 HD045581-01. Ardington acknowledges funding from NIH Fogarty International Center, Grant Number 2 D43 TW000657. Financial support for the working paper version of this article is acknowledged from Economic Research Southern Africa (ERSA). We thank Anne Case, the UNAIDS/World Bank Economics Reference Group, an ERSA referee and two EDCC referees for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Monash and Boerma (2004) include the 1998 South African DHS in their analysis but only present results aggregated at a regional level, Ainsworth and Filmer (2006) include the 1998 DHS and the 1995 and 1998 OHSs but do not analyze changes, Case and Ardington (2006) estimate enrolment and attainment deficits using the 2001 Census.

Unless explicitly stated, the term effect does not imply a causal effect but rather reflects an association.

The sample was based on the 1991 Population Census enumerator areas for the 1993 PSLSD and the 1995 OHS. The 1997 and 1998 OHSs and the 2002, 2003 and 2004 GHSs were drawn for the database of enumerator areas for the 1996 Census while the 2005 GHS was base on the 2001 Census. The PSLSD was designed as a self-weighting sample. Weighting for all OHSs was based on the 1996 Census figures, adjusted for growth. The population estimate for the 2002 GHS was based on an exponential extrapolation from the 1996 and 2001 Census estimates. Weights for the 2003, 2004 and 2005 GHSs were based on Statistics South Africa’s mid-year population estimates.

Under Apartheid South Africans were categorized into four racial groups, namely African, Coloured, Asian and White. Currently Africans represent over 80% of the South African population.

The Nelson Mandela HSRC Study of HIV/AIDS in 2005 found for those aged 15 to 49 the percentage HIV positive was 19.9% of Africans, 0.5% of whites, 3.2% of coloureds and 1.0% of Indian/Asians. (Shisana et al. 2005:40)

One caveat to this finding that orphans are still absorbed by the extended family is that street children are excluded from the samples by design so there is no way of knowing whether increasing numbers of orphans are living on the streets. Despite extensive searching, we were unable to find reliable statistics on the number of children living on the street. Email correspondence with Helen Meintjes and Katharine Hall from the Children’s Institute at the University of Cape Town confirmed that there are no reliable estimates of the number of children living on the street in South Africa.

In the 2005 GHS African children reported average school fees of R298 and R471 per annum for primary and secondary schooling respectively. The average per capita monthly household expenditure for these children was R228. One US Dollar was equivalent to around 6.5 South African Rands at the time of the 2005 GHS. The South African Schools Act of 1996 provided for a fee exemption to parents whose income is less than 10 times the annual school fees. However, in practice the fee exemption policy has not been successfully implemented due to poor awareness, no monitoring or enforcement and most importantly no budget to compensate for loss of revenue through the exemption policy. In 2007 the No-Fee Schools policy was introduced. This policy abolishes school fees in the poorest 40% of schools nationally from Grade R to Grade 9. These schools will be compensated for the loss of revenue from fees through a larger allocation from the Department of Education.

See Figures A1 and A2 in Ardington (2008).

The 1998 OHS is a smaller sample than previous years and is the only survey where the results are sensitive to the inclusion or exclusion of sampling weights. The 1998 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) was excluded from the analysis because the survey did not include a race variable in the household roster and only asked questions of parents’ vital status for children under fifteen years of age. Estimates for all South Africans aged 8 to 14 from the 1998 DHS show significant negative effects of a mother’s death on educational attainment (coefficient = −0.275, standard error = 0.106).

Contributor Information

Cally Ardington, South African Labour Development Research Unit, University of Cape Town.

Murray Leibbrandt, School of Economics and South African Labour Development Research Unit, University of Cape Town.

References

- Ainsworth M, Filmer D. Inequalities in Children’s Schooling: AIDS, Orphanhood, Poverty and Gender. World Development. 2006;34(6):1099–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B, Phillips H. Trends in the percentage of children who are orphaned in South Africa: 1995-2005. Statistics South Africa; Pretoria: 2006. Report No. 03-09-06. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KG, Case A, Lam D. Causes and Consequences of Schooling Outcomes in South Africa: Evidence from Survey Data. Social Dynamics. 2001;27(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ardington C. Orphanhood and Schooling in South Africa: Trends in the vulnerability of orphans between 1993 and 2005. University of Cape Town; 2008. SALDRU Working Paper No. 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beegle K, de Weerdt J, Dercon S. Orphanhood and the Long-Run Impact on Children. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2006;5:1266–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Bicego G, Rutstein S, Johnson K. Dimensions of the emerging orphan crisis in sub-Saharan Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;56:1235–1247. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Ardington C. The Impact of Parental Death on School Outcomes: Longitudinal Evidence from South Africa. Demography. 2006;43(3):401–420. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Deaton A. Large Cash Transfers to the Elderly in South Africa. Economic Journal. 1998;108(450):1330–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Paxson C, Ableidinger J. Orphans in Africa: Parental Death, Poverty and School Enrollment. Demography. 2004;41(3):483–508. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duflo E. Grandmothers and Granddaughters: Old-Age Pensions and Intrahousehold Allocation in South Africa. World Bank Economic Review. 2003;17(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Evans D, Miguel E. Orphans and Schooling in Africa: A Longitudinal Analysis. Demography. 2007;44(1):35–57. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske E, Ladd H. Elusive Equity. Education Reform in Post-Apartheid South Africa. Brookings Institute Press; Washing, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fortson J. Mortality Risk and Human Capital Investment: The Impact of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Princeton University; 2007. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Foster G. The capacity of the extended family safety net for orphans in Africa. Psychology, Health and Medicine. 2000;5(1):55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Foster G. Supporting Community Efforts to Assist Orphans in Africa. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(24):1907–1910. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb020718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarcello L, Lyon S, Rosati F, Valdivia CA. The influence of Orphanhood on Children’s Schooling and Labour: Evidence from Sub Saharan Africa. UNICEF; 2004. UCW Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L, Dorrington R. The Impact of AIDS on Orphanhood in South Africa: A Quantitative Analysis. University of Cape Town; 2001. Centre for Actuarial Research Monograph No. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly M. Planning for Education in the Context of HIV/AIDS. UNESCO; Paris: 2000. IIEP Fundamentals of Educational Planning, No. 66. [Google Scholar]

- Keswell M, Poswell L. How important is education for getting ahead in South Africa? Vol. 22. University of Cape Town; 2003. pp. 1–22. CSSR Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Lam D, Ardington C, Leibbrandt M. Schooling as a Lottery: Racial Differences in School Advancement in Urban South Africa. University of Cape Town; 2007. ERSA Working Paper 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monasch R, Boerma JT. Orphanhood and childcare patterns in sub-Saharan Africa: an analysis of national surveys from 40 countries. AIDS. 2004;18(suppl 2):S55–S65. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200406002-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, Parker W, Zuma K, Bhana A, Connoly C, Jooste S, Pillay V, editors. South African national HIV prevalence, HIV incidence, behaviours and Communication Survey, 2005. HSRC Press; Cape Town: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. UNICEF. USAID Children on the Brink 2004, A Joint Report of New Orphan Estimates and a Framework for Action. 2004 Available online at www.unaids.org.

- UNICEF Africa’s Orphaned Generation. 2003 Available online at www.unicef.org.

- UNESCO . World Declaration on Education for All. New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]