On February 17, 2006, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) announced the release of the revised Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree that became effective on July 1, 2007.1 Although there are numerous differences between Standards 2007 and previous versions, the general core areas remain similar but are condensed into 6 groupings of the Standards and Guidelines: Mission, Planning, and Evaluation; Organization and Administration; Curriculum; Students; Faculty and Staff; and Facilities and Resources.2 Within these core areas, significant changes have occurred, including the reorganization of standards to include institutional accreditation, student complaint policies, and more specific requirements for areas such as experiential education hours. Review procedures are more defined with an emphasis on the evaluation form/rubric, use of standardized survey instruments, and broad participation by faculty members and other key groups.3

Implementation of Standards 2007 presents several unknowns to schools and colleges undergoing accreditation for the first time under the new standards. Ramifications for being partially or non-compliant with the standards include a limited (2-year) time period to become compliant, potential probation, public availability of a college/school's status, and potential adverse accreditation action.4 Clearly, colleges/schools need to have their stakeholders knowledgeable and involved in the self-study to assure success.

The self-study process also changed, including the use of a self-study template supplied by ACPE. The template offers a consistent format to self-study reports, additional direction on sources of information to be used, and specific requirements for each standard and guideline. The template includes sections for both a summary of self-study process and a formal rating of the overall organization and clarity of the self-study process. The latter addition adds further evidence of the need for broad and inclusive participation during the self-study process.

Within the Overall Organization and Clarity section of the template, colleges and schools of pharmacy are rated on 6 general areas, 3 of which are linked directly to the involvement of stakeholders in the self-study process and their awareness of the subsequent findings. These 3 areas are:

Participation: the self-study report was written and reviewed with broad-based input from students, faculty members, preceptors, staff members, administrators, and a range of other stakeholders, such as patients, practitioners, and employers.

Completeness and transparency: all narratives and supporting documentation are thorough, clear, and concise. The content appears thoughtful and honest. Interviews match the self-study findings.

Knowledge of the self-study: students, faculty members, preceptors, and staff members are conversant in the major themes of the report and how the program intends to address any deficiencies.

Little information has been published on how schools and colleges of pharmacy approach the self-study process or the new Standards 2007. Although one program published their experiences using a project management approach, no other information is available.5 To our knowledge, no literature focuses on garnering widespread stakeholder involvement in the accreditation process. This paper describes several practices that may aid programs in achieving such involvement in the self-study process.

PARTICIPATION IN THE SELF-STUDY PROCESS

When possible, colleges and schools of pharmacy should consider attending a program such as the AACP Institute that can help focus and plan the self-study process. The 2007 AACP Institute coincided with the start of our self-study, and included a topic related to accreditation.6 Programs like this allow the faculty to begin planning and discussing their self-study, including the main ideals to promote throughout the process.

We began our discussions with how inclusive to make the self-study, balanced with the amount and division of work that would be asked of our stakeholders. We also established that our self-study committee would model inclusiveness and broad representation. Our committee was comprised of faculty members, staff members, students, alumni, preceptors, a state association staff member, and a university institutional research officer; however, the addition of civic leaders and patients would have been more inclusive.

In addition to the leadership and coordination charges set forth by ACPE, this committee was charged further with creating and integrating a communications plan.7 This charge helped identify additional opportunities for input to inform larger numbers of people about the self-study.

While both internal and external involvement is critical to a self-study, external stakeholders, such as alumni, preceptors, health care and research partners, government and professional associations, patients, and special interest groups can be more difficult to involve. Many of these groups were represented on our self-study committee as well as on our college standing committees that worked on various sections of the self-study.

External groups were also targeted by our communication plan. Several thousand alumni and other external stakeholders received updates and requests for input, either through college publications, e-mails, or direct invitations by the self-study committee. All contacts were encouraged to participate in the self-study process, and each was provided with an e-mail address, telephone number, and/or mailing address to use to send their questions or comments.

FOLLOW A TIMELINE OF INVOLVEMENT

After the Institute, we started the formal self-study process by planning 3 specific retreats. The first retreat occurred roughly 18 months prior to our site visit. Over 50 stakeholders attended this retreat, including faculty members, staff members, students, alumni, preceptors, and university staff members. It was a time to review assessment data, identify areas of need for the accreditation process, and develop an action plan for the self-study process.

The second retreat occurred 10 months later and focused on reviewing the work of the subcommittees. A complete draft of the self-study report was reviewed, focusing on the following questions: “What information or themes had surfaced?” “What findings needed to be stressed in the final report?” “What new information or updates needed to be included in a second draft?” “Did the report truly represent the college?” Because this retreat occurred during the summer break, people who were on 9-month contracts received a per diem allotment to participate. Participants again exceeded 50, and included faculty members, staff members, student leaders, alumni, preceptors, and institutional research staff members. The last retreat occurred 4 months later and finalized the self-study report. Both faculty and staff members attended this last formal meeting to discuss the content of the self-study report prior to a formal faculty vote on the final version.

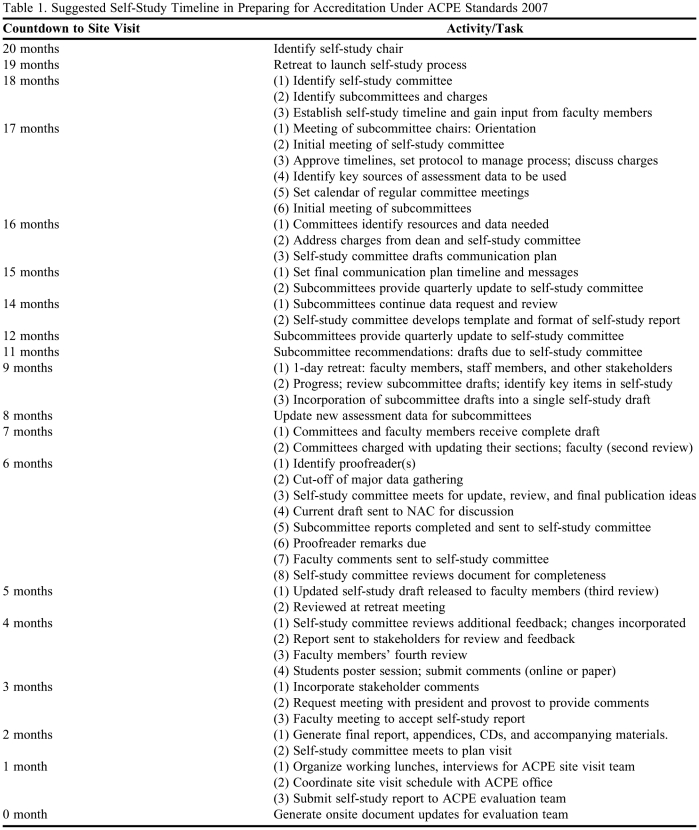

In addition to the retreats, deadlines were established as part of the self-study timeline. Some deadlines related to procedural issues such as establishing committee charges and due dates for various drafts, setting deadlines for gathering new data, and establishing outside reviewers. Others dealt with inclusiveness such as dissemination of the report to stakeholders, formal faculty voting, and publishing and releasing the final report (Table 1.)

Table 1.

Suggested Self-Study Timeline in Preparing for Accreditation Under ACPE Standards 2007

Balance the Workload

More than in earlier versions, Standards 2007 stresses the involvement of internal stakeholders, particularly faculty members, staff members, and students. Making them active participants while appreciating their regular workloads is important. To balance the amount and division of work for faculty members, the college's standing committees were used as subcommittees of the self-study committee. Each subcommittee chair was a member of the self-study committee. Using college committees in this way can ensure wide participation by faculty members, students, staff members, alumni, and preceptors because they are generally represented on most college standing committees.

Our college standing committees correlated well with the main sections of the self-study template (Academic Affairs Committee for the curriculum section, Student Affairs Committee for the students section, etc). Thus, each subcommittee was charged with drafting sections of the report that coincided with the standards and guidelines associated with areas normally under their purview. Committees communicated and shared progress by providing updates during faculty meetings and by posting drafts and quarterly updates to a shared Web-based portal.

Using the college committees as subcommittees also minimized additional service commitments and workloads. Rather than working on another committee, annual charges were altered to include self-study work. Assigning them a portion of the report to draft also drew upon their expertise and enhanced the report. It provided them the opportunity to be involved in a meaningful way and ensured that the report was not written by a select few.

Provide Support

Recognizing that many faculty members, including committee chairs, may never have been part of a self-study is important. To address this, we provided an orientation session for subcommittee chairs to orient them to the accreditation process, the self-study template, and deadlines established by the self-study committee. This orientation session also provided an opportunity for chairs to make suggestions and ask questions. Each subcommittee was also provided support tools, including the self-study template and our own formatting guidelines for drafting sections of the report. Subcommittees also received a document that allowed them to search the standards assigned to their committee, and the corresponding assessment data available from the college.

COMPLETENESS AND TRANSPARENCY OF THE SELF-STUDY REPORT

Be Transparent and Share All Data

The self-study committee made several decisions early in the process regarding transparency. As an example, the committee decided that broad transparency of data would include complete access by committee members and other select groups, such as the college's National Advisory Council (NAC). This was accomplished through the use of a college Web-based portal where all data, timelines, and reports were located. Self-study drafts were made available to students and the public throughout the process. These drafts were posted on the open-access college Web site and the college portal.

Communicate Information

We fostered awareness of the self-study and the report by creating a self-study communication plan. The plan included completion of the following steps:

A self-study theme was designed to drive ownership of the process: Our Future, Our Self-Study.

Online survey instruments, comment requests related to the organization of the process, and drafts of the report were sent to all students, faculty members, staff members, alumni, our NAC, the state board, the state pharmacy association, key stakeholders for health systems, and other deans on campus.

A poster session at the retreat used 6 posters to highlight both the noteworthy and the areas needing improvement under the 6 general areas of standards. This facilitated discussion at the retreat.

Posters in the main pharmacy building and computer laboratories provided students and others with information on the self-study, accreditation visit, key assessment data, and how to become involved.

Posters at our annual pharmacy and health sciences day, a college-wide event for students and faculty members, provided an overview of the accreditation process.

A quiz for students at a college-wide student event highlighted key elements of the self-study report and awarded a prize.

An online quiz for faculty members and staff members built awareness and awarded a prize.

Verbal updates were presented at the dean's Student Advisory Council meetings, faculty meetings, and monthly meetings of campus leaders.

Updates to students, faculty members, and staff members were provided via the college's weekly e-mail announcements.

Updates were sent to alumni via e-mails and annual publications.

Several parts of the plan were ideas generated by stakeholders at our first retreat. Student groups also provided feedback on the best ways to disseminate information to the entire student body.

KNOWLEDGE OF THE SELF-STUDY REPORT

Be Deliberate in Seeking the Input of Alumni

NAC meetings provided a venue to gain alumni input. Significant portions of 2 meetings were devoted to reviewing assessment findings, providing input, and reviewing the self-study report. Each NAC member was assigned a section and asked to summarize it for the rest of the group. They also were asked to report on what they had learned from reviewing the self-study. In addition, all alumni were invited to read and comment on the self-study and/or volunteer to be part of the process. This was accomplished through our alumni magazine and newsletters. Although we received only a few online comments, alumni were given the opportunity to be aware of the process and stay connected to the college.

Actively Seek Student and Faculty Input

Posters were displayed throughout the college buildings for faculty members and students to view. This provided information as well as a location to solicit their input. Calls for feedback were also placed in weekly college e-mail announcements. Additionally, the college's student government body was used as a sounding board to review and edit sections of the report that pertained to students and student government. Late in the self-study process, Web-based surveys collected comments on report drafts. Surveys also helped us judge our progress in seeking input and involvement.

Throughout this process, we asked that people focus on the content and issues of the report rather than grammatical issues. To decrease the need for faculty editorial review, we used 2 outside editors. A dean from another college of pharmacy reviewed the draft report for content issues and errors directly related to the Standards; and a second reviewer, from outside of pharmacy, reviewed the document for grammatical errors, flow, and clarity. Using these individuals reduced the amount of editing performed by college faculty members and staff members, and allowed us to focus on content and message.

SHARING DRAFTS AND COMMENTS

Each subcommittee was asked to provide quarterly reports to the self-study committee to keep groups on task and ensure that data was being analyzed and incorporated into their drafts. Faculty members and staff members were kept up-to-date on the progress of the study and given information during several venues, including retreats, subcommittee meetings, and general faculty and staff meetings. As with alumni and students, these groups were asked to provide comments in these meetings, but also anonymously via the online comment/survey mechanisms.

The broader university also was kept informed. Our dean met monthly with the provost, as well as bimonthly with the provost and other campus deans. The progress of the self-study was discussed periodically during these meetings.

CONCLUDING THE PROCESS, PRAISING THE STAKEHOLDERS

The accreditation/self-study process is time-consuming and requires a tremendous amount of work by all involved. To conclude the process and thank everyone, we invited all participants to a reception immediately following the site visit, sent an e-mail outlining the general tone of the exit interview, and mailed a personalized thank-you note to the participants acknowledging their work and dedication to the college.

BENEFITS OF THIS PROCESS

Maintaining active involvement and information flow among all stakeholders during the self-study has many positive benefits for a school or college of pharmacy. One of the most notable in our case was the engagement of stakeholders, providing the opportunity to hear and discuss multiple perspectives. Those involved in the study perceived more ownership and influence in the process, and had stronger commitment to planned changes. In addition, stronger outcomes and actions are likely when multiple perspectives are gathered.

To judge our success in engaging stakeholders, an anonymous survey was conducted asking stakeholders to rate the process. The survey instrument incorporated the 6 questions from the ACPE rubric for “Organization and Clarity,” as well as a question to identify the responder (student, staff member, faculty member, alumni, other, prefer not to answer). This survey instrument was administered just prior to final approval of the self-study report. A majority (85%) of the 39 respondents rated the college as “commendable” for participation in the self-study. Fifty-nine percent rated the process as “commendable” for their knowledge of the self-study, while 87% rated it “commendable” for completeness and transparency. Staff members and alumni rated these categories as commendable at an even higher rate than faculty members, thus, we achieved success in engaging our stakeholders and garnering widespread input and knowledge of the self-study.

Although we had strong alumni involvement on the self-study committees, there were several thousand other alumni and external stakeholders who were offered the chance to comment but chose not to. While asking individuals to read and comment on a self-study report in which they were not involved directly may be asking a lot, inviting their input may reinforce positive feelings toward the college.

Using college standing committees as self-study subcommittees can limit both the workload and perspective of any single individual or group. Thus, the final report tends to be a group project in both content and effort. In the end, there was little debate over our final report and faculty approval of the self-study report was unanimous.

Engaging all stakeholders in the self-study also promotes self-reflection and the opportunity to improve the program by using assessment data. For example, faculty members used information presented during the self-study to identify issues and implement changes to the curriculum. Similarly, college committees and service groups indentified better methods of carrying out their charges, as they reflected on the data reviewed during the self-study.

An ancillary benefit to broad involvement is that the different perspectives of the stakeholders were represented during the review of our program and our current strategic plan. As a result, their perspectives are now feeding directly into our latest college strategic planning.

Finally, we cannot discount the positive relations and pride built by involving and updating the many stakeholders. Stakeholders stated that they learned new and exciting information about the college by being part of the self-study. They also gained perspectives of the roles and challenges of each stakeholder group. Thus, the process was unifying and directly supported the culture of our institution while promoting involvement and ownership by our stakeholders.

SUMMARY

One major point of emphasis in the comprehensive self-analysis required for accreditation by ACPE involves assessing broad participation and knowledge by key stakeholders. This paper describes a comprehensive plan aimed at maximizing involvement and knowledge to create a broad and inclusive self-study. Benefits of this process include: multiple perspectives being represented, widespread buy-in and knowledge of the report, shared workload, self-reflection, and positive relations with stakeholders.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank the other members of the college's self-study committee for their ideas on creating an inclusive review: Carter Birkel, Rachel Boon, Elizabeth Cardello, Michael Case-Haub, June F. Johnson, Jennifer Moulton, and Roxanne Ruden. Thanks to all who participated in the self-study by serving on committees, participating in retreats, and/or providing perspectives, comments, and ideas.

The ideas expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and in no way are intended to represent the position of ACPE or other accrediting bodies.

REFERENCES

- 1. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/standards/default.asp. Accessed February 10, 2010.

- 2. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Mapping of ACPE Standards: Standards 2000 vs. Standards 2007, http://www.acpe-accredit.org/deans/standards.asp. Accessed February 10, 2010.

- 3.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Chicago, IL: August 2008. ACPE Self-Study Workshop. [Google Scholar]

- 4. US Department of Education. Accreditation in the United States. Part 602, Secretary's Recognition of Accrediting Agencies, Subpart B: The criteria for recognition, 602.20 Enforcement of standards. http://www2.ed.gov/admins/finaid/accred/index.html. Accessed February 10, 2010.

- 5.Dominelli A, Iwanowicz SL, Bailie GR, Clarke DW, McGraw PS. A project management approach to an ACPE accreditation self-study. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2):23–33. doi: 10.5688/aj710223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacKinnon GE., III PhD Evaluation, assessment, and outcomes in pharmacy education: The 2007 AACP Institute. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5) doi: 10.5688/aj720596. Article 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Standards 2007 Self-Study Guide, V 1.1, February 15, 2007. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/deans/resources.asp. Accessed February 10, 2010.