Abstract

We show that the local spike timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) rule has the effect of regulating the trans-synaptic weights of loops of any length within a simulated network of neurons. We show that depending on STDP's polarity, functional loops are formed or eliminated in networks driven to normal spiking conditions by random, partially correlated inputs, where functional loops comprise synaptic weights that exceed a positive threshold. We further prove that STDP is a form of loop-regulating plasticity for the case of a linear network driven by noise. Thus a notable local synaptic learning rule makes a specific prediction about synapses in the brain in which standard STDP is present: that under normal spiking conditions, they should participate in predominantly feed-forward connections at all scales. Our model implies that any deviations from this prediction would require a substantial modification to the hypothesized role for standard STDP. Given its widespread occurrence in the brain, we predict that STDP could also regulate long range functional loops among individual neurons across all brain scales, up to, and including, the scale of global brain network topology.

Keywords: STDP, microcircuitry, network, topology, neuromodulation, synfire, neocortex, striatum

Introduction

Connections between individual neurons in the brain are constrained first by the spatial distribution of axons and dendrites within the neuropil (Braitenberg and Schuz, 1998; Stepanyants et al., 2007). Global brain networks comprise dense connections within tissues, the gross structures in which these tissues are embedded, and the bidirectional long-range projections joining these structures. The topology of these networks is not yet fully specified at the level of microcircuitry, however1. One theoretical constraint on this level of organization, the “no strong loops hypothesis,” considered only developmentally determined area to area connectivity patterns to implement its specific neuron to neuron network topological constraint (Crick and Koch, 1998). While local synaptic modifications are known to directly shape the pattern of connectivity in local neural tissue and thus local microcircuit topology (Le Be and Markram, 2006), our understanding of global brain network topology still derives largely from this developmentally patterned, area to area connectivity. Furthermore, measuring simultaneously the relative strengths of specific microcircuit connections remains technically challenging, and virtually impossible for even medium sized (100–200 neurons, 0.05–0.1 mm) microcircuits. For these reasons, it is not yet known how large scale, long range microcircuit topology and the computation it supports emerges through synaptic modifications in the brain.

We wondered whether a synaptic modification commonly observed in local circuit preparations and widely hypothesized to shape local dynamics in brain structures, spike timing-dependent plasticity (STDP; Markram et al., 1997), could be analyzed to yield an understanding of what topology it predicts for microcircuits of any scale. The STDP model is a departure from traditional Hebbian models of learning, which state that neurons that fire action potentials together will have their interconnections strengthened. Instead, STDP takes into account the particular temporal order of pre- and post-synaptic neuronal firing (Morrison et al., 2008), such that the rule modifies synapses anti-symmetrically, depending on whether the pre- or post-synaptic neuron fires first (Figure 1). The basic question we then aimed to answer is: what is the influence of this anti-symmetry on brain microcircuit topology?

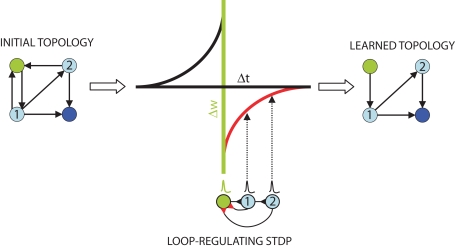

Figure 1.

Schematic of the topological effect of STDP. Feedback connections in an initial topology (left) from first (1) and second (2) order “follower” neurons (light blue) to a “trigger” neuron (green) create loops of length k = 2 and k = 3. These connections are selectively penalized by the STDP learning rule (lower middle, red). The plot (middle) depicts this rule, with the time difference between follower (black) and trigger (green) action potentials on the x-axis, and the expected synaptic modification on the y-axis. When spikes successfully propagate through the loopy network they feed back to the trigger, arriving at the follower–trigger synapse immediately after the trigger neuron fired and resulting in synaptic depression (red). Through repeated spike propagation events, STDP results in a completely feed forward learned topology (right) to the output neuron (dark blue).

Consider first if a pre-synaptic “trigger” neuron causes a post-synaptic, first-order “follower” neuron to fire. If this follower makes a direct feedback connection onto the trigger, the feedback connection will be weakened, since the spike generated by the follower will arrive at the follower–trigger synapse immediately after the trigger neuron's backward propagating action potential (Figure 1). The principle that STDP is suitable for eliminating strong recurrent connections between two neurons was originally proposed by Abbott and Nelson (2000). Here we expand on the principle with the observation that it holds for all polysynaptic loops connecting triggers and followers: if some nth-order follower's action potential produces in the original trigger a subthreshold potential after the trigger has fired, the functional loop will be broken by spike timing-dependent synaptic weakening of the feedback connection. With this intuition, we set out to prove analytically and by means of numerical simulation that network topology, and specifically the occurrence of functional loops in highly connected networks, is directly and necessarily regulated by STDP.

This theory paper provides clear predictions about STDP's effect on neural circuit topology. The proof and simulations dictate strong constraints on local and long range microcircuit connectivity. We propose that if these constraints are not obeyed by real neural circuits, the hypothesis that standard STDP shapes the structure and function of real nervous systems must be revised. Our approach suggests that similar analyses of other learning rules may impose similar constraints on neural circuit topology and that the hypothetical significance of these rules may similarly be tested.

Methods

Simulation

The simulation methods of Song et al. (2000) were used to simulate each neuron in our 100 neuron network. We observed the reported topological results in each simulation after 10 s of network activity. In some cases, we performed additional, longer simulations of network activity to explore the convergence and stability of these topological measures under various conditions. Briefly, each neuron model was integrate-and-fire, with membrane potential determined as in Song et al. (2000), by τm(dV/dt) = Vrest − V + gexc(t)(Eexc − V) + ginh(t)(Einh−V), with τm = 20 ms, Vrest = −60 mV, Eexc = 0 mV, Einh = −70 mV, Vthresh = −54 mV, and the reset voltage following a spike, Vreset = −60 mV.

The synaptic conductances gexc and ginh were modified by the arrival of a presynaptic spike, as in Song et al. (2000), such that and In the absence of a spike, these quantities decay by τexc(dgexc/dt) = −gexc, and τinh(dginh/dt) = −ginh, with τexc = τinh = 5.0 ms, and We initialized to different values for intra-network and extra-network inputs.

For extra-network inputs, excitatory homogeneous Poisson spike trains were generated at a constant rate rexc = 20 Hz. Inhibitory, inhomogeneous Poisson spike trains that model fast local inhibition were generated at a rate rinh, where rmin ≤ rinh ≤rmax, rmin = 5 Hz, and rmax = 1000 Hz. On each time step, dt = 0.1 ms, rinh decays with a time constant, τr = 2.0 ms, then is incremented by an amount proportional to the fraction, γ, of network neurons that spiked during that timestep, such that τr(drinh/dt) = −rinh, and rinh(t) → rinh(t)+(rmax − rmin) γ (t).

For all simulations we report here, the STDP update rule for a synapse from neuron j to neuron i was for synaptic depression, and for synaptic potentiation, μ = 0.1 ( is maintained in the interval As in Song et al. (2000), M(i) and Pa(i, j) decay exponentially, such that τ−(dM/dt) = −M(i) and τ+(dPa/dt) = −Pa, τ+ = τ− = 20 ms. Also as in Song et al. (2000), M(i) is decremented by A− every time a neuron i generates an action potential, A− = 0.00035, and Pa(i, j) is incremented by A+ every time a synapse onto neuron i from neuron j receives an action potential, A+ = 0.00035. This update rule effectively implements the anti-symmetric function of STDP (see Figure 1).

Analysis

To randomize our networks for analysis (Figures 2B,C, 4C and 5), we created a random sequence of indices ranging uniquely from 1 to n, where n was the number of off diagonal elements in our network's weight matrix. We used these indices to shuffle uniquely the positions of all off diagonal elements in the matrix, thus preserving the network's learned weight matrix, while destroying its learned topology.

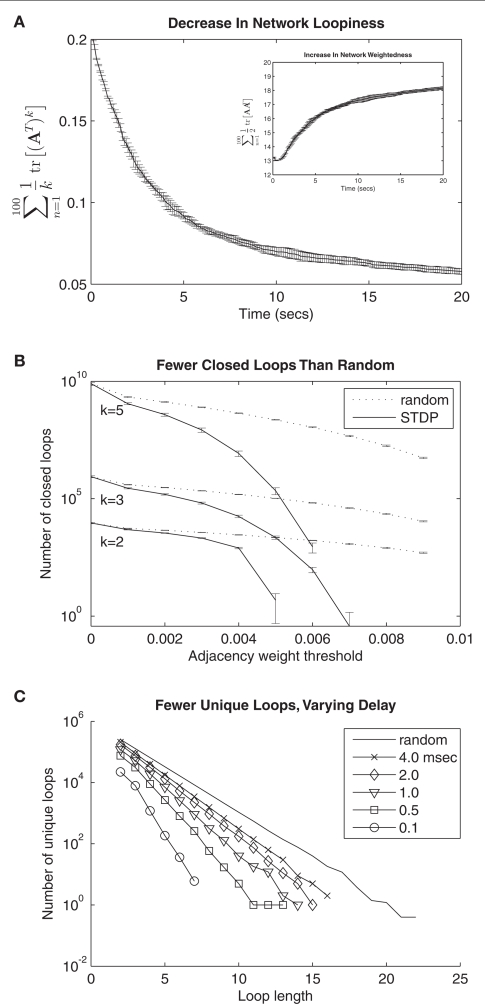

Figure 2.

Global topological effects of STDP. (A) A monotonic decrease in the loopiness measure (see Eq. 2, first term) over time is observed in a simulated network of 100 neurons undergoing STDP. Simultaneously, STDP results in a net increase in the weightedness of the network (inset, see Eq. 2, second term). Shown here and in (B) is the average of eight separate simulations of 20 s of network activity; error bars are standard deviation. (B) Number of closed loops of length 5, 3, and 2, decreases as a function of weight threshold for network connections. Dotted lines show counts for randomized networks with same number of total connections. (C) Number of unique loops sampled from five networks with varying synaptic delays following 10 s of simulated activity, and from a random network with 5000 connections. Number of loops is shown as a function of loop length. Loops were sampled across different learned networks while maintaining the number of network connections at 5000 by varying the weight threshold (from 0.003 to 0.0046) for each delay. Greater synaptic delays decreases the loop-eliminating topological effect of standard STDP.

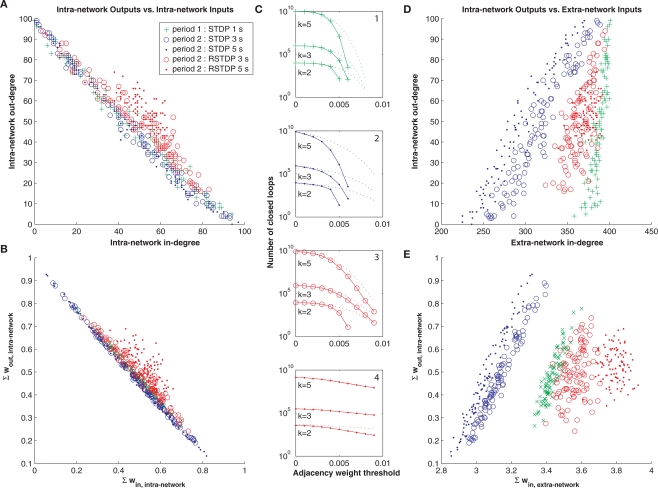

Figure 4.

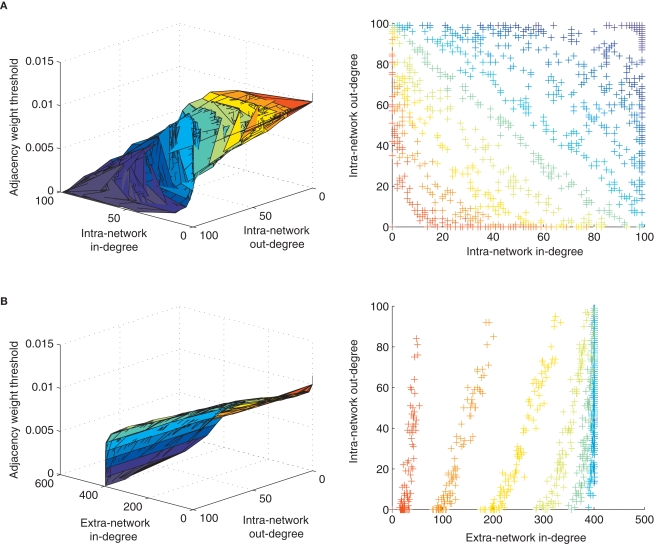

Effect of reverse STDP. (A) In-degree versus out-degree of intra-network connections following different durations and polarities of STDP, shows a strong inverse relationship for standard STDP. Adjacency weight threshold was 0.005. Markers correspond to the network after a period of 1 second of standard STDP (green), followed by periods of 3 seconds or 5 seconds of standard STDP (blue) or reverse STDP (RSTDP, red). (B) Total synaptic input versus output for intra-network connections shows a similar inverse relationship for standard STDP. (C) Number of closed loops of length 5, 3, and 2, is decreased by standard STDP, and restored with reverse STDP (plotted as in Figure 2B). (D) In-degree of extra-network inputs versus out-degree of intra-network outputs, plotted as in (A), shows a strong positive correlation for standard STDP. Adjacency weight threshold was 0.007 for extra-network inputs and 0.005 for intra-network outputs. (E) Total synaptic extra-network input versus total synaptic intra-network output, plotted as in (B), shows a similar positive correlation. In each panel the topological effects of STDP are reversed by reverse STDP.

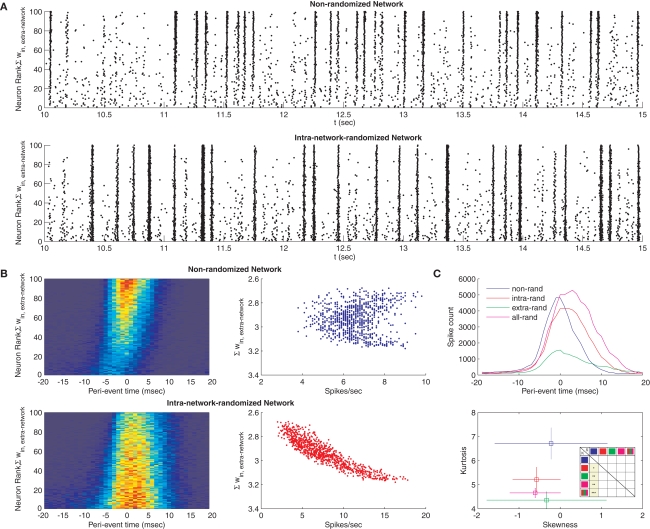

Figure 5.

Dynamical effects of STDP. (A) Raster plot of the spiking activity for a network after STDP (top), and for a surrogate network where intra-network weights were reassigned randomly to network connections, thus destroying STDP-learned topology (bottom). Each point corresponds to a spike for each neuron. Each neuron was assigned a rank according to the sum of its extra-network input weights, with the lowest rank corresponding to the highest sum. (B) Peri-event time histograms for each neuron in the STDP network (top left) and its surrogate (bottom left), pooled across eight separate simulations (bin width, 2 ms). Histograms show different network propagation properties. Spike counts and extra-network weights for the same networks do not co-vary in the STDP-learned topology (top right), but are highly correlated for the surrogate (bottom right). (C) Peri-event time histograms summed across all simulations and all neurons for the STDP network (blue) and three surrogates, in which the intra-network connections (red), extra-network connections (green) or both (magenta) were randomized (top). Skewness versus kurtosis of these histograms averaged across eight separate simulations each (bottom, error bars show standard deviation) indicates the network distribution of spikes is more peaked with more spread for the STDP-learned topology. Inset table shows P-values of unpaired t-tests of skew (upper right triangle) and kurtosis (lower left triangle) measurement distributions from each of eight simulations between each of the four conditions, plus the entire distribution of randomized networks (red, green, magenta, icons). Squares colored yellow are significant, with stars indicating P-values’ orders of magnitude (from P < 0.05–0.0005).

We chose to sample unique loops (Figure 2C) in the networks rather than enumerating them, since for long loops (k > 20) the number of possible paths to search would exceed 1020. To this end, for each loop length k, we therefore constructed one million random paths of length k − 1. We term these paths “unique” because we sampled neurons within each path without substitution (i.e., no paths containing sub-loops were generated such that a single neuron is traversed more than once). However, we allowed that each path could be represented more than once in the one million constructed paths. In fact, for the shortest paths constructed (k ≤ 3) this was necessarily the case since the total number of possible unique paths is less than one million.

We sampled unique loops from adjacency matrices constructed such that the weight threshold produced a matrix that was precisely half-full (for 100 neurons, a matrix with 5000 ones and 5000 zeros). For 4.0, 2.0, 1.0, 0.5, and 0.1 ms delays, these thresholds were 0.0032, 0.0030, 0.0033, 0.0037, and 0.0046. In this way, we controlled across experiments for varying weight distributions, and sampled loops from the same number of links across all experiments. Counts were compared against the randomized network constructed from 5000 links.

To detect network events (Figures 5B,C), we employed the method described by Thivierge and Cisek (2008). Briefly, for each simulation in which network events were detected, we generated spike trains at 1 ms resolution for each neuron, equal in duration to the time series analyzed and comprising the same number of spikes as observed for that neuron. We constructed network spike time histograms of these spike trains across all neurons using a bin width of 10 ms. We then determined a threshold for the network equal to a count which 5% of these bins exceeded. Thresholds were determined 1000 times for each network and each simulation, and the mean of these 1000 values used as the threshold above which network events were detected in network spike time histograms for each simulation.

Results

A proof of STDP as a form of loop-regulating plasticity

First, we represent STDP acting on a weight w associated with the connection between two neurons and their output variables x(t) to y(t), in the adiabatic approximation (i.e. small learning rate), as:

| (1) |

where Cxy(t) = ∫ x(t′ − t)y(t′) is the correlator, and S(t) is the anti-symmetric STDP update function, S(t < 0) = exp(λt), S(t > 0) = −exp(−λt). Consider this function operating over connections within a linear network driven by uncorrelated Gaussian inputs, ξ, such that where x is a vector of activities with components denoted by xi, the weight connection matrix has components Wij, and the input satisfies We show (see Section “Update Rule for the Weight Matrix” in Appendix) that the learning rule defined in Eq. 1 results in an update for the network weight matrix of the form ΔW = ΔW(W, τ, C0) where τ is the time constant of the STDP's exponential, and C0 is the instantaneous correlator C(0). This update rule influences global network topology in a very specific way.

To formalize our original intuition analytically, consider a linear network with only excitatory connections, such that the dynamics may be expressed as where Aij ≥ 0 is the network connectivity matrix (comprising the off-diagonal elements of the weight matrix and zeros on the diagonal), and −I represents a self-decay term. Next, we introduce a “loopiness” measure that estimates the strength of all loops of all sizes that occur in the network, The function tr [·] stands for the trace operation; this operation, when acting on the k-exponentiation of the adjacency matrix (comprising ones and zeros, where the nonzero entry aij represents a connection from network node i to network node j), counts the total number of closed paths of length exactly equal to k, i.e. k-loops2. When applied to the network connectivity matrix A, the operation counts loops weighted by the product of the synaptic strengths of the looping connections, resulting in a slightly different, but still useful, measure of loopiness.

It is possible, however, to reduce this measure without actually regulating topology by simply reducing the weights of all connections. A topological loopiness measure should therefore include a penalty to the weights’ vanishing; we choose −1/2tr [AAT], (T stands for the transpose operation) which, for weighted graphs, measures the sum of the squares of all network weights, and for a binary graph, counts the number of links. We then define the total topological loopiness as:

| (2) |

We show analytically that for any stable weight matrix W = −I + A, the change in this energy under random noise as a function of the evolution of the network under STDP, Δε ∼ tr [∂AεΔAT], is strictly semi-negative, and therefore STDP necessarily regulates this measure, resulting in a decrease in topological loopiness (see Section “Update Rule for the Weight Matrix” in Appendix). We therefore use the term STDP and “loop-regulating plasticity” interchangeably throughout.

Loop-regulating plasticity in a network of simulated neurons

What are the effects of this form of plasticity on network topology (and specifically on the number of functional loops) in nonlinear networks, such as those found in neural microcircuits? Because our proof of STDP as a form of loop-regulating plasticity applies only to linear networks or nonlinear networks that may be linearized, we aimed to show, using simulation, that the same principle extends to a biologically relevant, nonlinear regime. We replicated the simulation of Song et al. (2000), extending it in three ways (see Simulation). First, we created a network of 100 neurons, each receiving excitatory synapses from all other 99 “intra-network” input sources and from 401 randomly spiking “extra-network” input sources selected at random from 2500 homogeneous Poisson processes. All excitatory synapses underwent STDP. Second, we provided 250 inhibitory synapses to each neuron, sampled from 1250 spiking sources; the inhibitory inputs modeled fast local inhibition to the network using inhomogeneous Poisson processes with rates modulated by the instantaneous aggregate firing rate of the network (see Simulation). Third, we explored four different forms of STDP update (Burkitt et al., 2004) and observed robust loop-regulating plasticity for each; the results presented here used the STDP update rule of Gütig et al. (2003).

We initialized our network with maximum extra-network weights, and intra-network weights at half maximum. This caused the network to spike vigorously when extra-network inputs became active, but spiking rates were limited by the fast local-inhibition. After 20 s of simulated network activity, STDP had a profound effect on topological loopiness as defined in Eq. 2, measured over loops of length 2 ≤ k ≤ 100 for convenience (Figure 2A). We counted the number of closed, functional loops of varying length using tr [⌈A⌉k], where ⌈A⌉ was constructed by applying a sliding threshold to the network connectivity matrix (Figure 2B). We compared this quantity to the same, measured for a randomized network, constructed by randomly reassigning weights from the learned weight distribution to synapses in the network (see Analysis). These results are representative of all loop lengths measured (2 ≤ n ≤ 100) and show that as the weight threshold grows, the number of closed, functional loops in the STDP-learned network decreases more than in the randomized network. This form of loop-regulating plasticity can therefore be described as loop-eliminating.

The effect of synaptic delays on loop-regulating plasticity

We wondered what effect synaptic delays would have on this result, since we expected follower feedback spikes to cause less anti-loop learning as they fell further from the zero time difference maxima in the STDP update function. We also wondered if the decrease in the number of closed, functional loops compared to a randomized network also applied to unique, functional loops, in which no neuron is traversed more than once. We therefore sampled the number of unique, functional loops through networks simulated with synaptic delays from 0.1 to 4.0 ms. For each loop length 2 ≤ k ≤ 25, we constructed one million random paths of length k − 1, and for the learned and randomized networks (see Analysis). We searched for each path across all networks studied, and if the path and the kth link completing the functional loop existed in the network, we counted it for that network (see Analysis). The result is similar to that for closed loops, and, as expected, longer synaptic delays resulted in an exponential decrease in the number of loops as a function of loop length that deviated less from the same function for randomized networks, indicating weaker loop-regulating plasticity (Figure 2C).

Network in-hubs, out-hubs, and loop-regulating plasticity

Next, we asked if other topological measures of the STDP-learned networks may be correlated with our observation of STDP's effect on loopiness, since many different topological properties might coincide with or support this effect. For example, one means to create networks poor in loops is to ensure that nodes in the network are either “out-hubs” or “in-hubs,” but not both (Ma'ayan et al., 2008). An out-hub in a network of neurons has many strong postsynaptic connections but few strong presynaptic connections, and an in-hub has many strong presynaptic connections but few strong postsynaptic connections. We applied a sliding threshold to the network connectivity matrix learned by STDP, and examined the manifold, colored according to each applied threshold, which correlated in-degree versus out-degree for each neuron in our network (Degree refers to the number of weights which exceed the threshold). This showed a clear inverse relationship between in- and out-degrees that varied in form with weight threshold (Figure 3A). In contrast, by examining the in-degree from extra-network inputs, we found a positive correlation (Figure 3B), indicating that out-hubs were more likely to be in-hubs within the larger extra-network topology, and that in-hubs in our network were more likely to receive only the weakest extra-network inputs.

Figure 3.

Local topological effects of STDP. (A) Inverse relationship of in-degree versus out-degree of intra-network connections for each neuron in a network after 10 s of STDP across multiple weight thresholds for network connections. Colors in left and right panels correspond to a weight threshold used to construct the network over which degrees were measured. The color key can be read from the left panels’ vertical axes and corresponding color found along each manifold. (B) Correlated extra-network in-degree and intra-network out-degree indicate an opposite effect of STDP on extra-network inputs.

Reverse STDP restored loops after loop-eliminating plasticity

Beyond these standard topological analyses, we also examined biological properties of the network. We measured total synaptic input as a function of total synaptic output for all neurons in the STDP-learned network. In the same experiment, we asked if reversing the polarity of the standard STDP function might undo the effects of loop-regulating plasticity that results from standard STDP, since under this “reverse” condition, follower spikes would cause strengthening of closed-loop feedback connections. This reversal of polarity is biologically relevant, since it occurs at the synaptic interface between major brain structures such as neocortex and striatum (Fino et al., 2008), arises specifically at synapses between certain cell types, and is controlled by cholinergic and adrenergic neuromodulation, for example in the neocortical microcircuit (Seol et al., 2007). We found the same inverse relationship between in-degree versus out-degree for each neuron in our network (Figure 4A, green markers), as well as an inverse relationship between total synaptic input and output following 1.5 s of standard STDP (Figure 4B, green markers). These effects contributed to a reduction in the number of closed loops (Figure 4C, depicted as in Figure 2B), and each of these relationships could be largely abolished by 3 to 5 additional seconds of reverse STDP (Figure 4, red markers), in contrast to 3 to 5 additional seconds of standard STDP (Figure 4, blue markers), which strengthened them. We also found the same positive correlation between in-degree from extra-network inputs and out-degree within the network (Figure 4D), and between total extra-network synaptic input and total intra-network synaptic output (Figure 4E). This effect was also largely abolished by 3–5 s of reverse loop-regulating plasticity, but reinforced by 3–5 s of standard loop-regulating plasticity.

Dynamical effects of loop-regulating plasticity

What are the consequences of this form of network plasticity beyond topology? In the case of a linear network, reducing the number of loops implies more stable dynamics. Consider the stability of the unforced system the eigenvalues λ of W = −I + A can be expressed as:

| (3) |

which emphasizes the contribution of loops to system instability (Prasolov, 1994). Such a simple observation, however, does not make clear predictions about the effects of loop-regulating plasticity on nonlinear neural circuit function. We were surprised to find that raster plots of network spiking activity, when sorted according to certain topological metrics (e.g., the sum of extra-network input weights, the sum of intra-network output weights, in-degree, or out-degree) consistently revealed network events that originate with weak synchronization among out-hubs, followed by strong synchronization among in-hubs (Figure 5A, top), across eight independent simulations of the phenomenon. This effect was altered by randomizing the intra-network weights, such that synchronization events became stronger, more frequently global, and more frequent among out-hubs alone (Figure 5A, bottom). Peri-event time histograms constructed across eight independent simulations reveal this same effect (Figure 5B, left panels), with synchronization arising strongly among in-hubs after weak out-hub activation in the STDP-learned network, and globally in the randomized network (see Analysis for a description of how network events were detected). In the STDP-learned network, both in-hubs and out-hubs sustain spiking rates ranging from 4−9 Hz that are not correlated with in-degree, whereas in the randomized network, spiking rates range more broadly (3−16 Hz) and are highly correlated with extra-network in-degree (Figure 5B, right panels). We examined the summed network peri-event time histograms for the STDP-learned network and for networks that underwent randomization of their intra-network weights, their extra-network weights, or both (Figure 5C, top), across eight simulations for each condition. The resulting distributions, as well as a pooled distribution of times from all randomized networks, each differed from each of the others based on paired Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests (P ≈ 0). To examine what properties of these distributions distinguished them, we measured kurtosis and skew for each distribution from each simulation, and compared the distributions of kurtosis and skew measures between each group. Kurtosis differed significantly between the STDP-learned network topology and the randomized topologies (intra-network randomized, extra-network randomized, both randomized, Figure 5C, bottom). Results from unpaired t-tests of the distributions of skew and kurtosis measurements between four simulation conditions (calculated separately for each of the eight simulations) are shown in table inset (Figure 5C, bottom). These differences indicate that the effect of standard loop-regulating plasticity is to generate network topologies that support network events with greater spread and sharper peaks in time.

Discussion

Based on our simulations and analytical results, we propose that standard STDP must produce a network topology in real neural tissues that is conspicuously poor in both closed and unique loops, and that it will segregate neurons into out- and in-hubs to achieve this. Such a prediction can easily be tested by analyzing correlations between the number of functional input connections and the number of functional output connections made by neurons recorded during multi-patch clamp experiments in a structure in which STDP has been observed (e.g., Song et al., 2005; Le Be and Markram, 2006). Our theory predicts this correlation should be negative.

The network that emerges in such tissues will organize its relationship to inputs from other structures in an orderly fashion, making local out-hubs the primary target for long range inputs, and thus establishing a feed forward relationship between the network and its pool of inputs. In a larger system, we anticipate that local in-hubs would become long range outputs. This prediction may also be tested by correlating the local topological relationships of a neuron with its identified role as either an input, output, or interneuron within that structure.

We also make a clear prediction for the effect of synaptic delays on modulating the topological effects of STDP. Correlations between these delays and functional connectivity data from multi-patch clamp recordings from connected neurons undergoing STDP can also be measured to determine if synaptic delays predict the strength of reciprocal connections. Furthermore, we observe that at interfaces between brain structures where STDP is reversed by neuromodulation, circuit dynamics can be predicted from the expected change in network topology. For example, changes in STDP at the cortico-striatal synapse (Fino et al., 2005) resulting in reverse STDP would favor the emergence of strong cortico-striatal-thalamocortical loops resulting in oscillations in this circuit.

Interestingly, the depletion of loops and the separation of nodes into out-hubs and in-hubs has recently been reported in a variety of complex biological systems, including functional networks at the level of spatio-temporal resolution of fMRI, and the neural network of C. elegans (Ma'ayan et al., 2008), suggesting a general principle of organization and dynamical stability for entire classes of functional networks. These observations suggest quantitative measurements of topology in vertebrate microcircuits could produce similarly interesting results.

It has been observed in local circuit preparations that a bias exists among layer 5 pyramidal neurons of rat neocortex towards strong reciprocal connectivity (Song et al., 2005; Le Be and Markram, 2006), and towards looping motifs among triplets of this neuronal class (Song et al., 2005). Furthermore, cyclic connections are strongest among those neurons connected by the strongest synaptic weights. These same neurons also exhibit STDP at the excitatory synapses that join them (Markram et al., 1997). Given our analysis, it is now clear that these observations contradict each other; specifically, we have shown that standard STDP under normal spiking conditions with random, weakly correlated inputs is loop-eliminating. Therefore, other mechanisms and constraints than those we have analyzed must be at play.

Consider the case of networks that have recently spiked at abnormally high rates, either due to increased excitability within the network (e.g., due to injury, epilepsy, etc.) or due to otherwise elevated extra-network inputs. If the majority of post-synaptic potentials derived from loop feedback immediately cause action potentials, standard STDP may have the effect of strengthening loops. Also, a network driven by highly and specifically correlated inputs may spike in temporal patterns conducive to loop-strengthening by STDP (a hypothesis we are currently studying). Finally, as we have shown, a spiking network that has recently experienced a reversal of the polarity of STDP will also show an increase in the number of loops observed. Clearly more experiments and observation would be required in order to confirm or rule out each of these mechanisms.

We observe that network activity propagates smoothly through the feed-forward topology generated by STDP (Figure 5A, top panel) without segregating neurons by average spike-rates (Figure 5B, upper right panel). The effect on global brain function of such properties would include stable average firing rates shared among all neurons, regardless of their topological position, and robust signal propagation, similar to “synfire chains” (Abeles, 1991; Hosaka et al., 2008). Finally, our theory holds that the reversal of STDP's polarity represents a local switch for the modification of both global brain network topology and global brain dynamics. Thus sources of modulation (Pawlak and Kerr, 2008) that accomplish this reversal locally are in fact regulating global brain function by means of this switch.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the helpful contributions of Lucas Monzón, University of Colorado at Boulder, and Gustavo Stolovitzky, IBM Research, to the mathematical analysis, and the careful attention of the reviewers of the manuscript.

Appendix

Update rule for the weight matrix

The classical definition of Hebbian learning for the weight w connecting two dynamical variables x(t) and y(t) can be written, in its simplest form, as:

| (A1) |

| (A2) |

where η is the learning constant, which for exposition's sake will be set to 1. It is important, however, to keep in mind that in order to write Eqs. A1–A2 we are assuming an adiabatic approximation, i.e. the learning is small enough that the system can be considered to be in steady-state for the purpose of computing the correlation.

A natural extension of Eqs. A1–A2 is to introduce time, i.e. to consider delayed as well as instantaneous correlations:

| (A3) |

| (A4) |

It is assumed that the time-dependent weight function vanishes for long delays, limt→±∞ S(t) = 0; the classical learning rule is recovered when S(t) = δ(t). If, as some experimental results describing STDP suggest (Markram et al., 1997), the weight function displays strict temporal anti-symmetry, i.e. S(t) = −S(−t), then,

| (A5) |

| (A6) |

A multi-dimensional linear system driven by uncorrelated inputs can be described as:

| (A7) |

where each unit is independently subject to Gaussian white noise ξ(t), a vector whose components satisfy 〈ξi(t)ξj(s)〉 = σ2δijδ(t − s). The lagged correlator is related to the zero-lagged correlator by Risken (1996):

| (A8) |

where for notational convenience we name C0 = ∫ xT(t)x(t)dt, i.e. the correlator at zero lag, by construction a symmetric matrix. Hence the expression for the learning update is

| (A9) |

The temporal behavior of the weight function has been approximated by a piece-wise exponential form:

| (A10) |

where τ is STDP's time-constant, i.e. it expresses the window over which the plastic changes due to temporal coincidence are significant. Assuming that the network connections are only excitatory, and expressing without further loss of generality W = −I + A, we derive the synaptic weight update ΔW = ΔA as follows:

| (A11) |

Given that

| (A12) |

We obtain

| (A13) |

Leading finally to

| (A14) |

after dropping the multiplying constant τ/(1 + τ). From this expression it is possible to derive that the weight update is anti-symmetric, and that a perfectly symmetric system would not be modified, as C0 would commute with A (see below, Eq. A20). Of course, any small initial asymmetry will eventually be blown up. We can also see that STDP's time constant also introduces the same multiplying factor τ/(1 + τ) for A, which can be absorbed by a renormalization; we will assume therefore τ/(1 + τ) → 1 for the remaining of the exposition. Consistently, the limiting behavior of Eq. A14 implies ΔA(τ → 0) = 0.

Minimization of loops and dynamics

Now we can estimate the effect of the synaptic time-dependent plasticity expressed by Eq. A14 on the topology of the network. For this, we will postulate a penalty or energy function for what we will call “loopiness” of the network. A measure of the number of loops occurring in the network can be obtained by summing the trace of the exponentiation of the network connectivity matrix, This loop density can be simply minimized by making the connections vanish, so we need to introduce a regularization penalty to avoid this effect; an obvious measure of the strength of the connections in a network is which in a binary graph would be equivalent to the total number of links. We postulate then the following “loopiness” energy:

| (A15) |

The change in this energy upon small changes ΔA is expressed as it can be easily verified that and therefore:

| (A16) |

We will demonstrate in what follows that the traces of K1 and K2 are strictly semi-positive under the synaptic changes elicited by STDP (i.e. Eq. A14), and therefore the loopiness energy can only decrease over time. This will be the case for any stable weight matrix, i.e. as long as all the eigenvalues have negative real components, and under the assumption that the system is driven by gaussian noise.

Let us consider tr [K1], rewritten as:

| (A17) |

and which is of the form

| (A18) |

For any matrix P,

which upon expanding leads to

| (A19) |

and ensures the positivity of tr [K1], under the assumption C0 ≈ I. Moreover, we can show that this is valid for an arbitrary C0. Under the assumption of stability and homogeneous Gaussian noise, the correlation and weight matrices are related by the Lyapunov equation (Risken, 1996; DelSole, 1999):

| (A20) |

where QQT is the generalized temperature tensor of the noise, whose components are the corresponding noise variances. For the case we are considering, QQT = I, a symmetric system W = WT has the solution C0 = −W−1/2. A formal solution for the general case is (Horn and Johnson, 1991):

| (A21) |

which reduces to

| (A22) |

Following the derivation in Eqs. A18–A19, the full expression for tr [K1] can be written as:

| (A23) |

Given that

| (A24) |

It follows through Eq. A22 that tr [K1] ≥ 0

Similarly, the second term in Eq. A16, tr [K2], can be rewritten as:

which can be reduced to

Replacing A(I − A)−1 by (I − A)−1 − I, the term can be transformed to

| (A25) |

Assuming that QQT = I in Eq. A20, and pre-multiplying by W−1, we obtain,

| (A26) |

| (A27) |

from which we derive:

| (A28) |

Now we can use the formal solution of the Lyapunov equation, Eq. A21, and the fact that for a stable matrix such as W we can write:

and modify Eq. A28 accordingly:

| (A29) |

The eigenvalues of any matrix satisfy λ(eW) = eλ(W); hence,

| (A30) |

where λk are the N eigenvalues of W. Calling λk = −μk + iγk, μ > 0, the first term in the r.h.s. above is

Now we can compare both terms in the r.h.s. of Eq. A30 for each k and t: which leads directly to tr [K2] ≥ 0 and completes the proof of the semi-negativity of the changes in the energy function (Eq. A16).

Interestingly, this result is related to a property of M-matrices. A matrix is an M-matrix when: (1) the off-diagonal elements are semi-negative, Mij ≤ 0∀i ≠ j, and (2) it is “positive stable,” Re [λi (M)] > 0∀i. It can be shown that for any M-matrix of dimension N (Th. 5.7.23 in Horn and Johnson, 1991) tr [MT M− ] ≤ tr [I] = N. Choosing −W as an M-matrix, the theorem leads to a similar result for the non-negativity of tr [K2] when C0 is close to the identity.

We have assumed throughout that the system is in a regime of dynamical stability, and presented a case for the stabilizing effect of STDP by linking loops and eigenvalues in Eq. 3. It follows that loopiness minimization (Eq. 2) is equivalent to maximization of stability (as defined by the l.h.s. of Eq. 3), constrained by the total matrix weight. We can further understand this by explicitly expanding to first order the update Eq. A14 to see the effect on Assuming again that QQT = I, the solution to the Lyapunov equation (Eq. A21) can be approximated by a series expansion in powers of A (Horn and Johnson, 1991); to first approximation C0≃ I + 1/2(A + AT), leading to ΔA ~ A − AT. Through Eq. 3 we obtain δU . 1/2tr [AδA + δAA], and in turn δU . (tr [A2] − tr [AAT]) ≤ 0, making the system more stable.

Footnotes

1We use “microcircuitry” to refer to neural circuitry observed at the level of neurons and synapses and not necessarily in reference to a restricted spatial extent of these neurons (e.g., a “column”). For this reason, we view every brain connection as part of some microcircuit topology.

2Note that paths that traverse the same network node more than once are also counted.

References

- Abbott L. F., Nelson S. B. (2000). Synaptic plasticity: taming the beast. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 1178–1183 10.1038/81453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abeles M. (1991). Corticonics: Neural Circuits of the Cerebral Cortex. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Braitenberg V., Schuz A. (1998). Cortex: Statistics and Geometry of Neuronal Connectivity, 2nd edn.Berlin, Springer-Verlag [Google Scholar]

- Burkitt A. N., Meffin H., Grayden D. B. (2004). Spike-timing-dependent plasticity: the relationship to rate-based learning for models with weight dynamics determined by a stable fixed point. Neural Comput. 16, 885–940 10.1162/089976604773135041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick F., Koch C. (1998). Constraints on cortical and thalamic projections: the no-strong-loops hypothesis. Nature 391, 245–250 10.1038/34584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelSole T. (1999). Stochastic models of shear-flow turbulence with enstrophy transfer to subgrid scales. J. Atmos. Sci. 56, 3692–3703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fino E., Deniau J.-M., Venance L. (2008). Cell-specific spike-timing-dependent plasticity in gabaergic and cholinergic interneurons in corticostriatal rat brain slices. J. Physiol. 586, 265–282 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.144501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fino E., Glowinski J., Venance L. (2005). Bidirectional activity-dependent plasticity at cortico-striatal synapses. J. Neurosci. 25, 11279–11287 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4476-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gütig R., Aharonov R., Rotter S., Sompolinsky H. (2003). Learning input correlations through nonlinear temporally asymmetric hebbian plasticity. J. Neurosci. 23, 3697–3714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn R. A., Johnson C. R. J. (1991). Topics in Matrix Analysis. New York, Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka R., Araki O., Ikeguchi T. (2008). STDP provides the substrate for igniting synfire chains by spatiotemporal input patterns. Neural Comput. 20, 415–435 10.1162/neco.2007.11-05-043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Be J.-V., Markram H. (2006). Spontaneous and evoked synaptic rewiring in the neonatal neocortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 13214–13219 10.1073/pnas.0604691103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma'ayan A., Cecchi G. A., Wagner J., Rao A. R., Iyengar R., Stolovitzky G. (2008). Ordered cyclic motifs contributes to dynamic stability in biological and engineered networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 19235–19240 10.1073/pnas.0805344105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H., Lubke J., Frotscher M., Sakmann B. (1997). Regulation of synaptic efficacy by coincidence of postsynaptic APs and EPSPs. Science 275, 213–215 10.1126/science.275.5297.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison A., Diesmann M., Gerstner W. (2008). Phenomenological models of synaptic plasticity based on spike timing. Biol. Cybern. 98, 459–478 10.1007/s00422-008-0233-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak V., Kerr J. N. D. (2008). Dopamine receptor activation is required for corticostriatal spike-timing dependent plasticity. J. Neurosci. 28, 2435–2446 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4402-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasolov V. V. (1994). Problems and Theorems in Linear Algebra. Providence, American Mathematical Society [Google Scholar]

- Risken H. (1996). The Fokker Planck Equation: Methods of Solutions and Applications, 2nd edn Springer, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- Seol G. H., Ziburkus J., Huang S., Song L., Kim I. T., Takamiya K. (2007). Neuromodulators control the polarity of spike-timing-dependent synaptic plasticity. Cell 55, 919–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S., Miller K. D., Abbott L. F. (2000). Competitive hebbian learning through spike-timing-dependent synaptic plasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 919–926 10.1038/78829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S., Sjöström P. J., Reigl M., Nelson S., Chklovskii D. B. (2005). Highly nonrandom features of synaptic connectivity in local cortical circuits. PLoS Biol. 3, e68 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanyants A., Hirsch J. A., Martinez L. M., Kisvárday Z. F., Ferecskó A. S., Chklovskii D. B. (2007). Local potential connectivity in cat primary visual cortex. Cereb. Cortex 18, 13–28 10.1093/cercor/bhm027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thivierge J. P., Cisek P. (2008). Nonperiodic synchronization in heterogeneous networks of spiking neurons. J. Neurosci 28, 7968–7978 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0870-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]