Abstract

In neurons a well-defined source of signaling Ca2+ is the extracellular medium. However, as in all metazoan cells, Ca2+ is also stored in endoplasmic reticular compartments inside neurons. The relevance of these stores in neuronal function has been debatable. The Orai gene encodes a channel that helps refill these stores from the extracellular medium in non-excitable cells through a process called store-operated Ca2+ entry or SOCE. Recent findings have shown that raising the level of Orai or its activator STIM, and consequently SOCE in neurons, can restore flight to varying extents to Drosophila mutants for an intracellular Ca2+-release channel – the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (InsP3R). Both intracellular Ca2+-release and SOCE appear to function in neuro-modulatory domains of the flight circuit during development and acute flight. These findings raise exciting new possibilities for the role of SOCE in vertebrate motor circuit function and the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders where intracellular Ca2+ signaling has been implicated as causative.

Keywords: Orai; STIM; neuromodulators; inositol; 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; central pattern generator

Living forms maintain a complex relationship with ionic calcium (Ca2+). High concentrations of this ion are incompatible with several cellular processes, and lead to the precipitation of phosphates and aggregation of proteins. Since cells evolved in sea water with millimolar quantities of Ca2+, they developed multiple means of maintaining calcium homeostasis including sequestering excess Ca2+ in intracellular membrane bound stores. In parallel, cells also evolved signaling mechanisms which used changes in cytosolic Ca2+, either by entry from extracellular medium or release from intracellular stores, to regulate multiple aspects of cellular function.

In non-excitable cells Ca2+ signals are generated using an extensive ‘Ca2+ toolkit’ that consists of calcium channels and pumps on the plasma membrane and the membrane of intracellular stores that help in assembling signaling systems with varying temporal and spatial dynamics (Berridge et al., 2003). Cell surface receptor stimulation activates two closely coupled components of this toolkit; the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (InsP3R) followed by store-operated Ca2+ (SOC) channels. InsP3Rs rapidly release Ca2+ from intracellular stores such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) while SOC channels function to replenish ER stores from the extracellular milieu and contribute to a longer term Ca2+ signal. The plasma membrane four-trans-membrane spanning Orai protein was recently identified as the long elusive SOC channel (Feske et al., 2006; Vig et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2006), responsible for the Ca2+-release activated Ca2+ current (ICRAC; Hoth and Penner, 1992). The precise mechanism of SOC entry (SOCE) is still under investigation but several reports have established that Ca2+ depletion of ER stores is sensed by (stromal interaction molecule) STIM, an ER membrane protein, which upon store Ca2+ depletion oligomerizes in the ER, translocates close to the plasma membrane and organizes the Orai channel into clusters to bring about SOCE (Liou et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005; Cahalan, 2009). Recent findings strongly suggest that Orai and STIM together are necessary and sufficient for SOCE (Hewavitharana et al., 2007 and references therein). Here we discuss recent evidence for the function of these molecules in excitable cells like neurons and propose a general role for SOCE in neural circuits that co-ordinate rhythmic motor patterns.

Ca2+ signals play an important role in neural activity and it's modulation, as well as the development and maintenance of neural circuits (Berridge, 1998; Spitzer, 2002; Borodinsky et al., 2004). In most cases these signals are generated by rapid entry of extracellular Ca2+ through plasma membrane channels activated directly by voltage changes, ligands or sensory stimuli. The possible role of intracellular Ca2+ release in modifying neuronal excitability is much less understood. The majority of such studies have been at the cellular level where they implicate the ryanodine receptor as the primary source of Ca2+-release from the ER store leading to amplification and modulation of membrane conductances and/or neurotransmitter release. Similar studies of InsP3 -mediated Ca2+ release in neurons are far fewer (Verkhratsky, 2005 and references therein). The impact of Ca2+ -release from neuronal ER stores on physiological function has been best understood from study of mouse and Drosophila mutant phenotypes (Matsumoto et al., 1996; Street et al., 1997; Banerjee et al., 2004). These studies with InsP3R mutants support the idea that InsP3 mediated Ca2+ release is required in specific classes of neurons for co-ordination of rhythmic movement such as walking or flying. Further support for this idea comes from a recent study of the genetic basis for human SCA15 which has been attributed to heterozygosity of the Type 1 InsP3R (van de Leemput et al., 2007).

What has remained controversial is the means by which the ER store is refilled in neurons after intracellular Ca2+-release. Given the range of plasma-membrane Ca2+ entry mechanisms present on neurons it has been widely assumed that one or more of these could contribute to store-refilling. Despite this prevailing idea, the existence of SOCE in neuronal cells was originally demonstrated in the PC12 cell line (Clementi et al., 1992) and later in Aplysia bag cell neurons (Kachoei et al., 2006). It's relevance for development and plasticity of the nervous system has also been demonstrated ex vivo (Nishiyama et al., 2000; Emptage et al., 2001). Direct measurement of ICRAC in neurons has however been confounded by the long-held idea in the field that the Transient Receptor Potential class of membrane channels (TRPs) are the source of SOCE in both excitable and non-excitable cells. This conjecture originally arose from the conformational coupling model which proposed that Ca2+ release through the ER channels (RyR and InsP3R) induces a conformational change in which the ER and PM are closely apposed, leading to activation of the SOC channel on the PM (Irvine, 1990). Genetic studies in Drosophila visual transduction (where TRP channels were first discovered), demonstrated that mutant alleles of Gq and PLCβ have strong deficits in Ca2+ entry through TRP channels. These results initially suggested that InsP3 generated by PLCβ activates ER Ca2+-release through the InsP3R leading to extracellular Ca2+-entry via TRP channels (Hardie and Minke, 1995). The observation that both partial and null alleles of the InsP3R have no effect upon Ca2+ entry through TRP channels in Drosophila photoreceptors essentially put the idea of TRPs as SOC channels to rest in Drosophila neurons (Acharya et al., 1997; Raghu et al., 2000). Consequently, until recently the possible source and role of SOCE in neuronal function remained doubtful.

With the discovery of STIM and Orai, their role in SOCE downstream of InsP3-mediated Ca2+ release has been investigated in Drosophila neurons (Venkiteswaran and Hasan, 2009) in the context of the flight circuit. The importance of the InsP3R and intracellular Ca2+ release in flight circuit development has been demonstrated earlier. itpr gene mutants, in the only Drosophila InsP3R gene, are flightless and unable to generate normal rhythmic action potentials from flight motor neurons despite no observable defects in general synaptic function (Banerjee et al., 2004). Moreover, InsP3R mediated Ca2+ signaling is required at multiple steps for generating the neural circuit responsible for air-puff stimulated Drosophila flight (Banerjee et al., 2006). Adult Drosophila with RNAi knock-down of either STIM or Orai in neurons exhibit phenotypes that are indistinguishable from each other or that of InsP3 receptor mutants. Significantly, the over-expression of either STIM or Orai in InsP3 receptor mutant neurons can suppress flight defects to various extents. These experiments provide the first functional link between Ca2+-release through the InsP3 receptor and store-operated Ca2+ entry through the STIM/Orai pathway in neurons. The temporal and spatial analysis of this mode of intracellular Ca2+ signaling has provided more interesting insights.

A range of mutant phenotypes related to flight are observed upon reduced InsP3 mediated Ca2+-release and SOCE in Drosophila neurons. Through measurements of intracellular Ca2+ signals in primary cultures of neurons from the appropriate genotypes it has been possible to correlate alterations of cellular Ca2+ homeostasis and signaling with systemic changes in flight ability. Amongst these, an abnormal wing position, high frequency of spontaneous firing from the dorsal longitudinal muscles and the inability to initiate flight patterns arise from reduced intracellular Ca2+ release during flight circuit development. The temporal nature of Ca2+ signals that contribute to all of the above phenotypes are such that they can be suppressed by slowing down uptake of cytosolic Ca2+ to the ER store by a dominant mutant in the SERCA pump (Banerjee et al., 2006). This is not so for signals required for maintenance of flight after initiation. Maintenance of flight requires robust SOCE which can be restored in InsP3 receptor mutant neurons by reducing SERCA and increasing Orai function. Through experiments that drive Orai over-expression in adults it appears that the requirement for SOCE is during flight though this needs more rigorous testing (Venkiteswaran and Hasan, 2009).

The ability to express specific transgenes in restricted neuronal domains in Drosophila has helped narrow down the range of neuronal classes where intracellular Ca2+ release and SOCE is important in the context of flight. At present, apart from sensory neurons and flight motoneurons, other neurons that constitute the air-puff induced flight circuit are poorly defined. Flight defects in itpr mutants are rescued by expression of either itpr+ or dSTIM+ (and to a lesser extent dOrai+) transgenes in aminergic and insulin-like peptide (ILP) secreting neurons (Banerjee et al., 2004; Agrawal et al., 2010). These domains are non-overlapping and both are neuro-secretory suggesting that they impact flight circuit formation and function through neuro-modulatory mechanisms that are non-cell autonomous. The relatively mild-phenotypes observed upon knock-down of itpr gene function in either one or both these domains supports this idea and suggests the existence of neuro-modulatory inputs in addition to monoamines and ILPs (Agrawal et al., 2010).

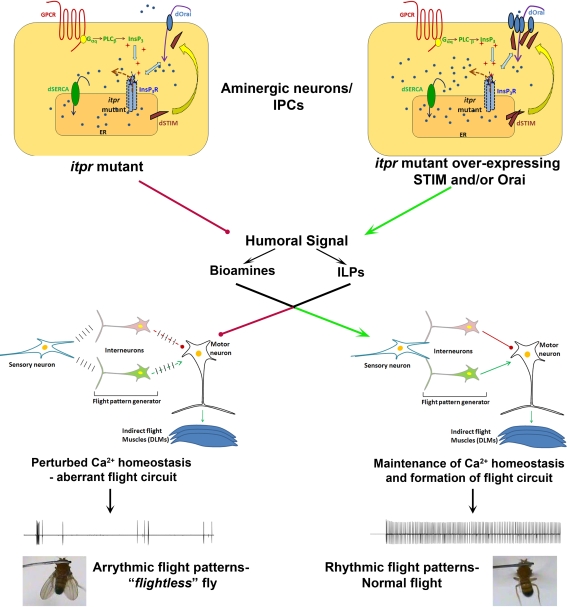

A better understanding of how InsP3 mediated intracellular Ca2+-release and SOCE control the signaling properties of neuro-modulatory neurons will be relevant for understanding the precise role of intracellular Ca2+ signaling in motor circuit function. Neuro-modulation of motor circuits can modify both cellular and synaptic properties of neurons in the circuit (Marder and Bucher, 2001). This is re-inforced by the Drosophila work, where deficits in the flight neural circuit can be rectified by what appears to be an altered balance of neuro-modulators like ILPs and monoamines. Measurements of intracellular Ca2+ at rest and upon cell surface receptor stimulation in Drosophila neurons support the idea that changes in resting Ca2+ levels in itpr mutants (Ca2+ homeostasis) strongly influence the Ca2+ signals generated upon stimulation. Altered Ca2+ homeostasis in itpr mutants is reverted back to normal to a significant extent by over-expression of dOrai and dSTIM (Figure 1). The effect of these cellular properties on the release of neuro-modulators needs to be assessed. Moreover experiments, which distinguish between the need for InsP3R, STIM and Orai in the functioning of single neurons of the flight circuit, as compared with their role in maintaining overall health of the flight circuit, are required. In Drosophila, the use of genetic strategies that allow controlled spatial and temporal expression of siRNAs in smaller subsets of neurons will be informative.

Figure 1.

Normal SOCE in neuromodulator releasing neurons of itpr mutants restores flight circuit function. Both InsP3 receptor function and SOCE are impaired in a Drosophila itpr mutant (left). Over-expression of the SOCE components Orai and/or STIM restores SOCE in Drosophila itpr mutant cells and improves their ability to release Ca2+ in response to an InsP3 generating signal (right). Restoration of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in either monoamine or insulin-like peptide producing neurons drives humoral signals which help in formation of a normal flight circuit and maintenance of adult flight patterns thus conferring free flight ability.

The close coupling observed between InsP3 mediated Ca2+ release and SOCE via the Orai/STIM pathway for maintenance of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in neurons and the proposed role of neuromodulators in this process, suggests novel potential strategies for the treatment of diseases where intracellular Ca2+ dyshomeostasis may be causative or exacerbated. Perturbation of neuronal Ca2+ homeostasis is believed to be one of the underlying causes for several neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer's disease (Bouron et al., 2004), Parkinson's disease (Chan et al., 2009), Huntington's disease (Tang et al., 2003), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS; Appel et al., 2001). It has also been implicated in the progression of several spino-cerebellar ataxia syndromes (Inoue et al., 2001; van de Leemput et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2008). It is thought that dysregulation of Ca2+ homeostasis synergizes with accumulation of mutant proteins in promoting the symptoms and pathology associated with the diseases. The Drosophila work raises the possibility of using drugs that directly modulate Orai function on the cell membrane or providing specific neuro-modulatory compounds to re-set Ca2+ homeostasis in diseased neurons. The hope is that these interventions could slow down the neurodegenerative process. Much needs doing in vertebrate model systems to address these possibilities before application in human disease conditions.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Acharya J. K., Jalink K., Hardy R. W., Hartenstein V., Zuker C. S. (1997). InsP3 receptor is essential for growth and differentiation but not for vision in Drosophila. Neuron 18, 881–887 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80328-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal N., Venkiteswaran G., Sadaf S., Padmanabhan N., Banerjee S., Hasan G. (2010). Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and dSTIM function in Drosophila insulin producing neurons regulates systemic intracellular calcium homeostasis and flight. J. Neurosci. 30, 1301–1313 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3668-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel S. H., Beers D., Siklos L., Engelhardt J. I., Mosier D. R. (2001). Calcium: the Darth Vader of ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Other Motor Neuron Disord 2(Suppl. 1), S47–S54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Joshi R., Venkiteswaran G., Agrawal N., Srikanth S., Alam F., Hasan G. (2006). Compensation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor function by altering sarco-endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase activity in the Drosophila flight circuit. J. Neurosci. 26, 8278–8288 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1231-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Lee J., Venkatesh K., Wu C. F., Hasan G. (2004). Loss of flight and associated neuronal rhythmicity in inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor mutants of Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 24, 7869–7878 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0656-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M. J. (1998). Neuronal calcium signaling. Neuron 21, 13–26 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80510-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M. J., Bootman M. D., Roderick H. L. (2003). Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 517–529 10.1038/nrm1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodinsky L. N., Root C. M., Cronin J. A., Sann S. B., Gu X., Spitzer N. C. (2004). Activity-dependent homeostatic specification of transmitter expression in embryonic neurons. Nature 429, 523–530 10.1038/nature02518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouron A., Mbebi C., Loeffler J. P., De Waard M. (2004). The beta-amyloid precursor protein controls a store-operated Ca2+ entry in cortical neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 20, 2071–2078 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03680.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan M. D. (2009). STIMulating store-operated Ca(2+) entry. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 669–677 10.1038/ncb0609-669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C. S., Gertler T. S., Surmeier D. J. (2009). Calcium homeostasis, selective vulnerability and Parkinson's disease. Trends Neurosci. 32, 249–256 10.1016/j.tins.2009.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Tang T. S., Tu H., Nelson O., Pook M., Hammer R., Nukina N., Bezprozvanny I. (2008). Deranged calcium signaling and neurodegeneration in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. J. Neurosci. 28, 12713–12724 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3909-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementi E., Scheer H., Zacchetti D., Fasolato C., Pozzan T., Meldolesi J. (1992). Receptor-activated Ca2+ influx. Two independently regulated mechanisms of influx stimulation coexist in neurosecretory PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 2164–2172 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emptage N. J., Reid C. A., Fine A. (2001). Calcium stores in hippocampal synaptic boutons mediate short-term plasticity, store-operated Ca2+ entry, and spontaneous transmitter release. Neuron 29, 197–208 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00190-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S., Gwack Y., Prakriya M., Srikanth S., Puppel S. H., Tanasa B., Hogan P. G., Lewis R. S., Daly M., Rao A. (2006). A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature 441, 179–185 10.1038/nature04702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie R. C., Minke B. (1995). Phosphoinositide-mediated phototransduction in Drosophila photoreceptors: the role of Ca2+ and trp. Cell Calcium 18, 256–274 10.1016/0143-4160(95)90023-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewavitharana T., Deng X., Soboloff J., Gill D. L. (2007). Role of STIM and Orai proteins in the store-operated calcium signaling pathway. Cell Calcium 42, 173–182 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoth M., Penner R. (1992). Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates a calcium current in mast cells. Nature 355, 353–356 10.1038/355353a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T., Lin X., Kohlmeier K. A., Orr H. T., Zoghbi H. Y., Ross W. N. (2001). Calcium dynamics and electrophysiological properties of cerebellar Purkinje cells in SCA1 transgenic mice. J. Neurophysiol. 85, 1750–1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine R. F. (1990). ‘Quantal’ Ca2+ release and the control of Ca2+ entry by inositol phosphates--a possible mechanism. FEBS Lett. 263, 5–9 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80692-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachoei B. A., Knox R. J., Uthuza D., Levy S., Kaczmarek L. K., Magoski N. S. (2006). A store-operated Ca(2+) influx pathway in the bag cell neurons of Aplysia. J. Neurophysiol. 96, 2688–2698 10.1152/jn.00118.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J., Kim M. L., Heo W. D., Jones J. T., Myers J. W., Ferrell J. E., Jr., Meyer T. (2005). STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr. Biol. 15, 1235–1241 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E., Bucher D. (2001). Central pattern generators and the control of rhythmic movements. Curr. Biol. 11, R986–R996 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00581-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M., Nakagawa T., Inoue T., Nagata E., Tanaka K., Takano H., Minowa O., Kuno J., Sakakibara S., Yamada M., Yoneshima H., Miyawaki A., Fukuuchi Y., Furuichi T., Okano H., Mikoshiba K., Noda T. (1996). Ataxia and epileptic seizures in mice lacking type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Nature 379, 168–171 10.1038/379168a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama M., Hong K., Mikoshiba K., Poo M-m., Kato K. (2000). Calcium stores regulate the polarity and input specificity of synaptic modification. Nature 408, 584–588 10.1038/35046067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghu P., Colley N. J., Webel R., James T., Hasan G., Danin M., Selinger Z., Hardie R. C. (2000). Normal phototransduction in Drosophila photoreceptors lacking an InsP(3) receptor gene. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 15, 429–445 10.1006/mcne.2000.0846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer N. C. (2002). Activity-dependent neuronal differentiation prior to synapse formation: the functions of calcium transients. J. Physiol. Paris 96, 73–80 10.1016/S0928-4257(01)00082-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street V. A., Bosma M. M., Demas V. P., Regan M. R., Lin D. D., Robinson L. C., Agnew W. S., Tempel B. L. (1997). The type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor gene is altered in the opisthotonos mouse. J. Neurosci. 17, 635–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang T. S., Tu H., Chan E. Y., Maximov A., Wang Z., Wellington C. L., Hayden M. R., Bezprozvanny I. (2003). Huntingtin and huntingtin-associated protein 1 influence neuronal calcium signaling mediated by inositol-(1,4,5) triphosphate receptor type 1. Neuron 39, 227–239 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00366-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Leemput J., Chandran J., Knight M. A., Holtzclaw L. A., Scholz S., Cookson M. R., Houlden H., Gwinn-Hardy K., Fung H. C., Lin X., Hernandez D., Simon-Sanchez J., Wood N. W., Giunti P., Rafferty I., Hardy J., Storey E., Gardner R. J., Forrest S. M., Fisher E. M., Russell J. T., Cai H., Singleton A. B. (2007). Deletion at ITPR1 underlies ataxia in mice and spinocerebellar ataxia 15 in humans. PLoS Genet. 3, e108 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkiteswaran G., Hasan G. (2009). Intracellular Ca2+ signaling and store-operated Ca2+ entry are required in Drosophila neurons for flight. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 10326–10331 10.1073/pnas.0902982106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A. (2005). Physiology and pathophysiology of the calcium store in the endoplasmic reiculum of neurons. Physiol. Rev. 85, 201–279 10.1152/physrev.00004.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig M., Peinelt C., Beck A., Koomoa D. L., Rabah D., Koblan-Huberson M., Kraft S., Turner H., Fleig A., Penner R., Kinet J. P. (2006). CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science 312, 1220–1223 10.1126/science.1127883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. L., Yeromin A. V., Zhang X. H., Yu Y., Safrina O., Penna A., Roos J., Stauderman K. A., Cahalan M. D. (2006). Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca(2+) influx identifies genes that regulate Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 9357–9362 10.1073/pnas.0603161103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. L., Yu Y., Roos J., Kozak J. A., Deerinck T. J., Ellisman M. H., Stauderman K. A., Cahalan M. D. (2005). STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature 437, 902–905 10.1038/nature04147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]