Abstract

Uncontrolled growth of malignant cells produces hypoxic regions in locally advanced tumors. Recently we showed that tumor hypoxia-induced transcription of multiple genes involved in glycan synthesis, leading to expression of useful glycolipid tumor markers, such as gangliosides having N-glycolyl sialic acid. Our subsequent studies indicated that the ceramide portion of glycolipids, as well as their glycan moiety, was also significantly affected by hypoxia. Tumor hypoxia induced marked accumulation of sphinganine (dihydrosphingosine) long chain base, and significant reduction of unsaturated very-long-chain fatty acids in the ceramide moiety. Mass-spectrometry, which yields information on both glycan- and ceramide moieties, is expected to be clinically useful in detecting such distinct molecular species of cancer-associated glycolipids having combined alteration in both glycan- and ceramide moieties.

Keywords: N-glycolyl sialic acid (NeuGc), dihydroceramide synthesis, fatty acid 2-hydroxylase (FA2H), dihydroceramide Delta4-desaturase-1/2 (DES1/2), hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), unsaturated very long-chain fatty acid (VLCFA)

1. Introduction

Cell surface glycolipids are known to undergo drastic changes upon malignant transformation [1,2]. Glycolipids appearing in cancer cells are shown to serve as good tumor markers, and applied also as therapeutic targets of cancers [3,4]. The mechanisms underlying tumor-associated changes of glycolipids, however, are complicated and remain elusive. Some changes occur at the relatively early stages of carcinogenesis, while some other changes become apparent only in the advanced stages along with progression of cancers. In the stages of locally advanced cancers, uncontrolled growth of tumor cells produces hypoxic areas in expanded cancer cell nests. Tumor hypoxia affects various aspects of intracellular metabolisms of cancer cells, and recently it was disclosed to be one of the major mechanisms for induction of cancer-associated glycans in glycolipids and glycoproteins. Here we introduce the notion that tumor hypoxia affects not only the glycan moiety of glycolipids, but also their ceramide moiety.

2. Hypoxia and cancer-associated glycolipids

Recently we showed that tumor hypoxia leads to enhanced expression of some cell-surface glycans, that had been well-known to be associated with cancers, such as sialyl Lewis X and sialyl Lewis A. This turned out to be due to induction of the transcription of the genes involved in the synthesis of these glycans by hypoxia as analyzed by DNA microarray [5]. Since then, it is becoming clearer year after year that tumor hypoxia affects a wide variety of genes involved in the expression of cell surface glycoconjugates, and induces profound changes in the expression of glycolipids and glycoproteins in cancers.

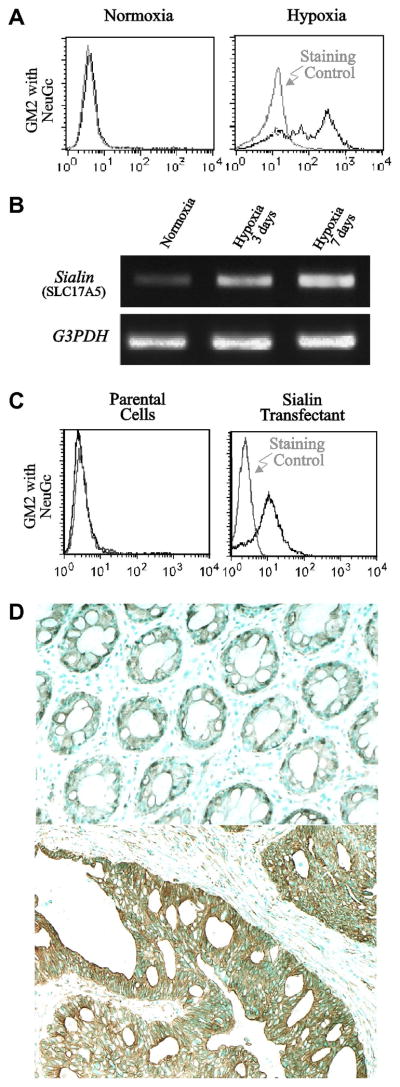

For instance, it has long been known that gangliosides carrying N-glycolyl sialic acid increases in human cancers. Such gangliosides are sometimes called Hanganatziu-Deicher antigens [6,7]. Recently we have shown that hypoxia-induced up-regulation of a gene for the sialic acid transporter, Sialin, is closely related to the enhanced expression of gangliosides carrying N-glycolyl sialic acid (Fig. 1) [8]. Humans lack the gene for CMP-neuraminic acid hydroxylase, the enzyme required to synthesize NeuGc, and most NeuGc in the human body is thought to be acquired from the external milieu, mainly of dietary origin [9,10]. Tumor hypoxia induces transcription of Sialin, and enhances incorporation of exogenous sialic acid. This leads to enhanced incorporation of NeuGc as well as NeuAc, and results in significant accumulation of unusual gangliosides carrying N-glycolyl sialic acid in cancers. Such gangliosides serve as surrogate markers for the presence of cell masses suffering from chronic hypoxia.

Fig. 1.

Hypoxia-induced expression of ganglioside GM2 having N-glycolyl sialic acid. Panel A, flow-cytometric analysis of a clone of human cultured colon cancer cells Caco-2M using monoclonal antibody specific to NeuGc-GM2 (MK2–34) indicating prominent induction of the ganglioside by hypoxia. Panel B, RT-PCR analysis of transcriptional induction of the gene for a sialic acid transporter, Sialin, by hypoxia in Caco-2M cells. Panel C, results of flow-cytometric analysis of Caco-2M cells indicating transfection of Sialin gene confers significant NeuGc-GM2 expression. Panel D, immunohistochemical staining of NeuGc-GM2 in a colon cancer tissue using specific monoclonal antibody, indicating the ganglioside serves as a good marker for advanced stage cancer cells. Advanced cancer cells acquire hypoxia-tolerance, and this accompanies sustained Sialin expression. Upper panel, non-malignant colonic epithelial cells; lower panel, cancer cell nests.

De novo synthesis of N-glycolyl sialic acid is based on oxidative hydroxylation of N-acetyl sialic acid catalyzed by CMP-NeuAc hydroxylase, a specific oxidase, expression of which is phylogenetically well controlled; it is present in mammals up to higher apes, but absent in humans [11–13]. As the conversion of N-acetyl to N-glycolyl sialic acid is based on oxidative hydroxylation, production of NeuGc through de novo synthesis may be suppressed under hypoxic conditions in mammals up to higher apes. In contrast, the expression of NeuGc rather increases under hypoxic conditions in humans, where its level is determined by its salvaging through the transporter Sialin, instead of de novo synthesis.

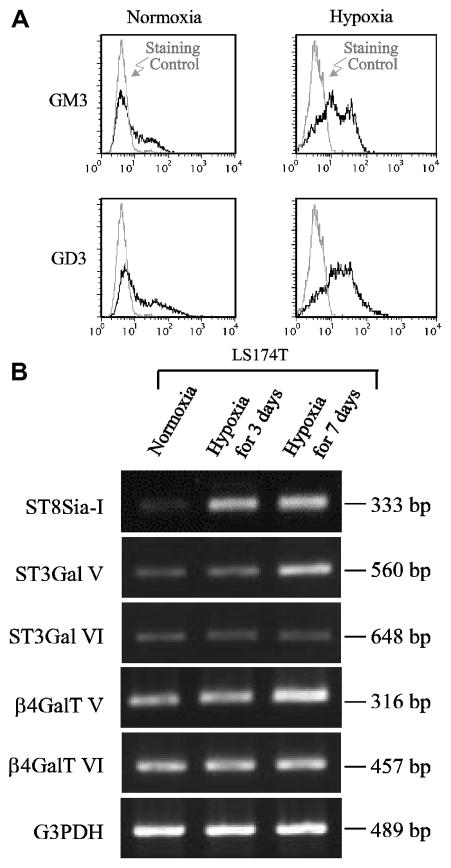

Effects of hypoxia are not limited to changes in sialic acid molecular species, but sometimes extend to the glycan backbone of gangliosides. Marked induction of GD3 expression and moderate induction of that of GM3 were observed in this cell line after hypoxic culture (Fig. 2A). This was accompanied by a prominent induction of ST8Sia-I transcription (Fig. 2B). The ST3GalV gene shows a delayed moderate induction, while genes for other glycosyltransferases show only minimal changes.

Fig. 2.

Hypoxia-induced induction of ganglioside GD3. Panel A, flow-cytometric analysis of a cultured human colon cancer cell line, LS174T, using monoclonal antibodies specific to GD3 (GMR19) and GM3 (M2590). Panel B, RT-PCR analysis of transcriptional induction of genes involved in GD3 synthesis by hypoxia in LS174T cells.

3. Ceramide composition and tumor hypoxia

During the course of study of tumor-associated gangliosides, we have noticed that significant changes occur at the ceramide moiety as well as carbohydrate moiety of the gangliosides during hypoxia. This was initially noticed from changes in the mobilities of ganglioside bands in TLC-immunostaining with specific anti-ganglioside antibodies after hypoxic culture. Broadening of the main band and appearance of additional slow-migrating band were frequently observed, which implied altered ceramide composition in gangliosides by hypoxia.

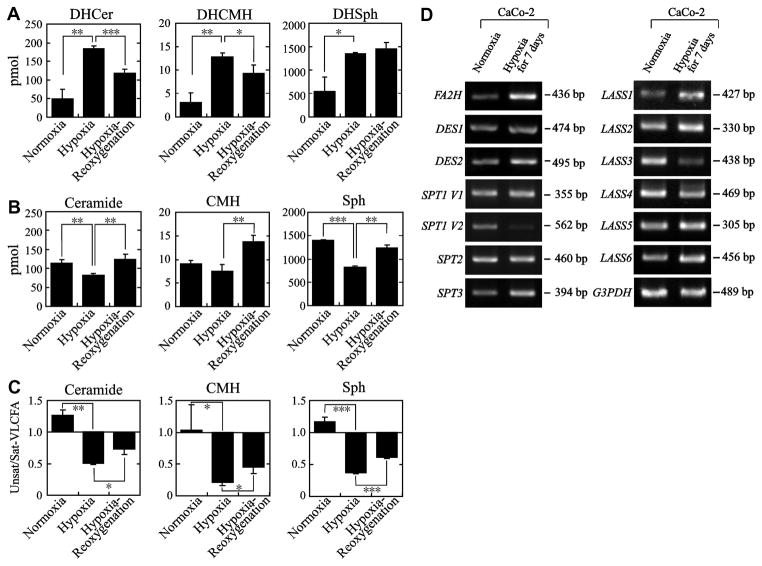

Analyses of sphingolipid molecular species by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS indicated a significant accumulation of dihydroceramide under hypoxia (Fig. 3A). A similar accumulation of dihydroceramide moiety was detected also in the glycolipid and sphingomyelin fraction (Fig. 3A). This was accompanied with the decrease in ceramide moiety with d18:1 LCB (Fig. 3B). It is interesting to note that the ratio of sphingosine/sphinganine is reportedly decreased in certain tumors both in ceramide and sphingomyelin fractions in the literature [14,15].

Fig. 3.

Hypoxia-induced changes in ceramide moieties of sphingolipids in cultured human colon cancer cells. Caco-2M cells [8] was cultured under normoxic conditions (normoxia), hypoxic conditions (1% O2) for 7 days (hypoxia), or hypoxic conditions for 7 days followed by normoxic conditions for 24 hrs (hypoxia+reoxygenation). Lipids were extracted and analyzed by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS according to the protocol shown in [35]. Panel A, effects of hypoxia on sphingolipids having dihydrosphingosine LCB (d18:0, sphinganine); Panel B, effects of hypoxia on sphingolipids having sphingosine LCB (d18:1) with ceramides; Panel C, effects of hypoxia on the ratio of monounsaturated/saturated VLCFAs (sum of monounsaturated C20:1~C26:1/sum of saturated C20~26) in the ceramide moiety of sphingolipids. *, Significant at p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. Panel D indicates the results of RT-PCR analyses of gene transcription involved in sphingolipid synthesis indicating significant transcriptional induction of LASS1 (CerS1) and FA2H by hypoxia. Transcription of LASS3 (CerS3) was markedly reduced. Only modest changes were observed in transcription of other genes.

Another notable finding was a sharp decrease in the amount of unsaturated very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) in the ceramide moiety by hypoxia. C24:1 was the major unsaturated acyl chain in the given cells, and its amount exhibited a marked decrease by hypoxia, and tended to recover after reoxygenation. This was accompanied by an increase of saturated VLCFAs by hypoxia, which was most prominent with C22:0 species. Accordingly, the ratio of unsaturated/saturated VLCFAs showed a sharp reduction upon hypoxic culture, and tended to recover after reoxygenation in all tested sphingolipid fractions (Fig. 3C), reflecting impaired desaturase reaction for VLCFAs under hypoxic condition.

Subsequent RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 3D) indicated a significant enhancement of transcription of FA2H, while only marginal changes were observed with DES1/2 transcription. Lack of DES1 induction indicated that the impaired dihydroceramide desaturation due to paucity of oxygen is not going to be compensated by the induction of gene transcription. The increase of dihydroceramide species in sphingolipids by hypoxia seems to simply reflect the uncompensated result of oxygen deprivation. At this moment the relationship between changes in LASS (CerS) and SPTLC (SPT) transcription and alteration of ceramide acyl chain composition is not clear. The increase in FA2H may be related to the appearance of slow-migrating band in TLC-immunostaining.

The FA2H and DES1/2 products require oxygen in their catalytic action. It is highly conceivable that such enzymes requiring oxygen would increase under hypoxic conditions to cope and compensate for the paucity of oxygen. It, however, seems to apply to only a part of such enzymes, in this case, FA2H, and does not apply to others such as DES1/2. In the latter case, the deficiency of oxygen would be straightforwardly reflected in changes in the ceramide composition of glycolipids.

4. Pathophysiological significance of hypoxia-induced alteration of glycolipids

Cancer cells must cope with hypoxic environment to survive and expand the size of tumors. Thomlinson-Gray’s equation on tissue oxygen diffusion [16] indicates that cancer cells in an area more than 75 μm distant from a blood vessel suffers from hypoxia, where oxygen tension becomes less than 10 mmHg. The major metabolic change in cancer cells induced by hypoxia is known to be elevated anaerobic glycolysis, accompanied by increased production of angiogenic factors. Enhanced expression of selectin ligand glycans such as sialyl Lewis A and sialyl Lewis X confers a growth advantage to cancer cells under hypoxic environment, because they mediate adhesion of cancer cells to endothelial cells expressing selectins. Induction of genes involved in sialyl Lewis A and sialyl Lewis X by hypoxia is closely involved in tumor angiogenesis [17] and hematogenous metastasis [18–20]. Hypoxia is known to also induce sphingosine kinase-1, and enhances synthesis of sphingosine-1-phosphate, which reportedly has a strong angiogenic activity [21,22].

The advantage for cancer cells of enhanced sialic acid transport through sialin is not clear at this moment. Cancer cells generally have enhanced cell surface sialylation, and have increased demand for sialic acid donors for use in the synthesis of sialylated glycans. Uptake and reuse of sialic acids through the transporter may economize on energy required for their de novo synthesis.

The accumulation of ceramide moieties having a d18:0 long-chain base, and decrease in unsaturated N-acyl chains seems to reflect a passive consequence of oxygen deprivation, rather than an active accomodation of the cells to hypoxic environments. In addition, the difference between cancers and normal cells is usually only quantitative, and not qualitative. Still it is noteworthy that dihydroceramide has been known to have much reduced activity in inhibiting cell growth and inducing apoptosis [23]. This may confer an additional growth advantage to cancer cells accumulating dihydroceramide.

Hypoxia-induced alteration in long-chain base and acyl chain composition of ceramide moiety may also influence the physicochemical properties and affect microdomain formation and signal transduction of cancer cells [24–28]. Accumulation of sphinganine long-chain base and decrease in unsaturated very long-chain fatty acids seem to favor more enhanced segregation of sphingolipid-enriched domains.

5. Mechanisms for gene transcription induced by tumor hypoxia

A transcription factor called hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) figures heavily in gene transcription induced by hypoxia. Although several genes are known to be induced by hypoxia independent of HIF, HIF is the major player in the gene transcription in hypoxia. The α-subunit of HIF usually resides in cytoplasm, and is rapidly ubiquitinated and degraded in proteasomes under normoxic conditions. Ubiquitination stops under hypoxic conditions due to oxygen sensing by proline hydroxylases and several other molecules, and this leads to nuclear translocation of α-subunit, where it forms an active heterodimer with the β-subunit present in the nucleus, and induces transcription of genes having a hypoxia-responsive element (HRE). Transcription of many cellular genes is thus induced, which are beneficial for cells to adapt to, or to cope with, hypoxic environments. Some genes, especially those with multiple HREs in their regulatory region, are readily induced by HIF alone, while other genes require cooperation of transcription factors other than HIF for maximal induction of transcription; thus, the set of genes induced by hypoxia is not the same in every cell and tissue. This results in the enhanced expression of various glycolipids and gangliosides upon hypoxic culture depending on the cells used in experiments.

6. Paradoxical effects of hypoxia-induced genes in cancers

Hypoxia-induced gene transcription is usually reversible in normal cells, since re-oxygenation rapidly restores ubiquitination of the α-subunit of HIF in normal cells. On the other hand, cancer cells acquire hypoxia resistance through sustained HIF expression, in most cases by irreversibly interfering with HIF ubiquitination. For instance, loss of anti-oncogenes such as p53 or VHL inhibits ubiquitination of HIF and leads to its sustained nuclear translocation. Tumor hypoxia promotes malignant progression by facilitating selection and clonal expansion of the more aggressive cancer cells, which can overcome oxygen deprivation or escape the hypoxic environments. Such cancer cells have constitutively elevated transcription of hypoxia-inducible genes even if under the normoxic condition. Once HIF is irreversibly activated, cancer cells tend to exhibit enhanced expression of sialyl Lewis A/X or Hanganatziu-Deicher gangliosides, irrespective of oxygen tension in their environments.

This sometimes leads to paradoxical consequences, especially when the enzymes require oxygen for their catalytic activity. Some of the genes for enzymes requiring oxygen are induced under hypoxic conditions in normal cells, but enzymatic products are not effectively generated because of paucity of oxygen. On the other hand, when genes for such enzymes are irreversibly induced in cancer cells, this sometimes leads to an abnormal overproduction of primary enzymatic metabolites, because of sustained gene transcription even under normoxic conditions. There are not many enzymes requiring oxygen for glycan synthesis, while many such enzymes are involved in lipid synthesis, such as in biosynthesis of sphingolipids and plasmalogens, or in hydroxylation and unsaturation of fatty acids, where the paradoxical effects may be observed in cancers.

7. Increase of cancer specificity by combination of multiple tumor-associated changes

Malignant transformation affects cell surface glycan expression through various mechanisms [29]. One of the major mechanisms is so-called incomplete synthesis of glycans. For instance, mature nerve cells express higher gangliosides such as GD1a and GM1, but malignant neuroblastoma cells frequently express shorter gangliosides such as GM2 or GD3. Cancer cells tend to express shorter chain glycolipids compared to the corresponding non-malignant cells of the same tissue origin, and this is mainly due to epigenetic silencing of a part of the genes required for the synthesis of normal complex gangliosides (Fig. 4). Similarly, normal epithelial cells express sialyl 6-sulfo Lewis X and disialyl Lewis A, the glycans having more complex structures than cancer-associated glycans, sialyl Lewis X and sialyl Lewis A. Epigenetic silencing of genes involved in GlcNAc 6-sulfation or α2–6 sialylation upon carcinogenesis results in the appearance of sialyl Lewis X and sialyl Lewis A in cancer cells [30–32]. This mechanism affects cancer cell glycans at the relatively early stages of carcinogenesis. This mechanism, however, is not strictly cancer-specific, since a similar set of genes is sometimes silenced epigenetically also under non-malignant conditions such as in inflammatory diseases.

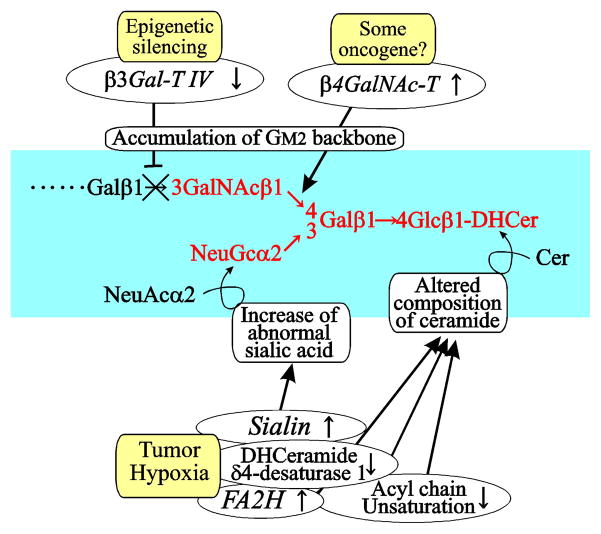

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of cancer-associated changes of glycolipids, exemplified by GM2. Epigenetic silencing of a part of genes required for normal complex glycolipids results in accumulation of shorter glycolipids such as GM2 at the relatively early stages of carcinogenesis. Elevated transcription of the gene forβ GalNAc transferase is also noted in cancers [48], which occurs independent of tumor hypoxia. Cancer cells acquire hypoxia tolerance in the locally advanced stages, and this leads to alterations in both glycan moiety and ceramide moiety of glycolipid. The molecular species of glycolipids exhibiting combination of multiple tumor-associated changes are expected to have higher cancer specificity.

Later in the locally advanced tumor stages, cancer cells cope and overcome hypoxic environments by acquiring hypoxia-resistance. This process further promotes changes in cell surface glycans. These hypoxia-induced changes are also not strictly cancer-specific, since a similar set of genes is also induced by hypoxia in non-malignant diseases such as ischemic disorders. It means that the Hanganatziu-Deicher gangliosides are not strictly specific to cancers, but can appear in non-malignant cells under chronic hypoxic conditions. Normal gangliosides would acquire N-glycolyl sialic acid under hypoxic conditions, and such gangliosides may not serve as specific markers for cancers.

When, however, well-known cancer-associated gangliosides, such as GM2 or GD3, are modified by N-glycolyl sialic acid, such gangliosides exhibit higher cancer specificity, and are competent to serve as excellent markers of cancer cells. If normal neural tissues were attacked by hypoxia, normal gangliosides such as GM1 and GD1a would be mainly modified by N-glycolyl sialic acid. It is noteworthy that the glycan molecules reflecting the combined effects of both epigenetic silencing and tumor hypoxia have relatively higher cancer specificity. The GM2 ganglioside having N-glycolyl sialic acid could be one of such examples.

The same principle can be applied to other cancer-associated glycans such as sialyl Lewis X and sialyl Lewis A carrying N-glycolyl sialic acid. Modification of cancer-associated glycans by N-glycolyl sialic acid would further improve their cancer specificity. In contrast, if normal epithelial cells were subjected to hypoxic condition, normal glycans in epithelial cells such as sialyl 6-sulfo Lewis X and disialyl Lewis A would be mainly modified by N-glycolyl sialic acid.

8. Cancer-associated changes affect both glycan and ceramide moieties of glycolipids

Our results as described here indicated that tumor hypoxia affects not only glycan moiety, but also the ceramide moiety of tumor-associated glycolipids. For instance, it could be suggested that the tumor-associated glycolipids having dihydroceramide moiety with less unsaturated very long-chain fatty acids would have higher cancer specificity.

To date detection of cancer-associated glycans largely relied on the use of specific monoclonal antibodies. A good example is an antibody specific to the GM2 ganglioside having N-glycolyl sialic acid. Such a ganglioside having dihydroceramide would be more specific to hypoxia-resistant clones of cancer cells. Although the ceramide moiety of glycolipid is known to significantly affect its antigenicity [33], it is difficult to expect anti-glycolipid antibodies to specifically detect glycolipids having definite molecular species of ceramide. In contrast, mass-spectrometry is theoretically best fit for this purpose, because it directly detects molecular species of ceramide moiety of given glycolipids [34,35].

9. Clinical application of glycolipids as future cancer markers detected by mass spectrometry

An increasing number of papers has reported examples of successful large-scale routine determination of glycolipids from small amounts of clinical samples using mass-spectrometry. A significant increase in plasma ceramide levels was detected in type 2 diabetic patients accompanied with C18:1 and C18:0 subspecies [36]. An increased plasma level of ceramide was shown to be a risk factor also for early atherosclerosis using LC-MS/MS [37]. Determination of urinary globotriaosylceramide levels by LC-MS/MS is used for screening of Fabry disease [38]. Matrix-assisted laser desorption mass-spectrometry (MALDI-MS) is successfully applied for detection of ceramides or non-sialylated glycolipids such as monohexosyl ceramide and sulfatide [39–41]. Although these methods utilizing mass spectrometry supply precious information on the ceramide composition, the pathophysiological significance and clinical utility of such information do not seem to be widely appreciated. Recent methods applying mass spectrometry for detection of disease-marker glycolipids in patients sera or tissue samples sometimes include procedures to isolate the glycan portion from glycolipids through chemical or enzymatic cleavage [42–44]. Information on ceramide moiety becomes unavailable by such procedures.

Quality of tissue imaging by matrix-assisted laser desorption mass-spectrometry (MALDI-MS) is significantly improved recently [45–47]. At present the sensitivity and resolution are not enough for detection of minor molecular species, but ultimately, the imaging MALDI-MS should be able to demonstrate hypoxic lesions in tissue sections, which are occupied by cancer cells expressing the cancer-associated glycolipids exhibiting a distinct long-chain base and amide-linked fatty acid composition. Differential display of the ratio of hypoxia-related molecular species of ceramide moiety of a given cancer-associated glycolipid to those non-related normoxic constituents using appropriate software will help to obtain more clear imaging of tumor cell nests composed of hypoxia-resistant cancer cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (21590324), grants-in-aid for the Third-Term Comprehensive Ten-year Strategy for Cancer Control from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, a grant from Uehara Memorial Foundation, a grant from Mitsubishi Pharma Research Foundation, a grant from Life Science Foundation of Japan (to R.K.), and an NIH grant GM069338 (to A.M.).

Abbreviations used

- CerS

ceramide synthase

- CMH

ceramide monohexose

- DHCer

dihydroceramide

- DHCMH

dihydroceramide monohexose

- DHSph

dihydrosphingomyelin

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- HPLC-ESI-MS/MS

high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry

- HRE

hypoxia-responsive element

- LCB

long-chain base

- MALDI-MS

matrix-assisted laser desorption mass spectrometry

- NeuAc

N-acetyl sialic acid

- NeuGc

N-glycolyl sialic acid

- SPT

serine palmitoyl transferase

- Sph

sphingomyelin

- VLCFA

very long-chain fatty acid

References

- 1.Hakomori S. Glycosylation defining cancer malignancy: new wine in an old bottle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10231–10233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172380699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hakomori S. Tumor-associated carbohydrate antigens defining tumor malignancy: basis for development of anti-cancer vaccines. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;491:369–402. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1267-7_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabbatini PJ, Ragupathi G, Hood C, Aghajanian CA, Juretzka M, Iasonos A, Hensley ML, Spassova MK, Ouerfelli O, Spriggs DR, Tew WP, Konner J, Clausen H, Abu RN, Dansihefsky SJ, Livingston PO. Pilot study of a heptavalent vaccine-keyhole limpet hemocyanin conjugate plus QS21 in patients with epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4170–4177. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Livingston PO, Hood C, Krug LM, Warren N, Kris MG, Brezicka T, Ragupathi G. Selection of GM2, fucosyl GM1, globo H and polysialic acid as targets on small cell lung cancers for antibody-mediated immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:1018–1025. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0663-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koike T, Kimura N, Miyazaki K, Yabuta T, Kumamoto K, Takenoshita S, Chen J, Kobayashi M, Hosokawa M, Taniguchi A, Kojima T, Ishida N, Kawakita M, Yamamoto H, Takematsu H, Kozutsumi Y, Suzuki A, Kannagi R. Hypoxia induces adhesion molecules on cancer cells-a missing link between Warburg effect and induction of selectin ligand carbohydrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8132–8137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402088101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higashi H, Hirabayashi Y, Fukui Y, Naiki M, Matsumoto M, Ueda S, Kato S. Characterization of N-glycolylneuraminic acid-containing gangliosides as tumor-associated Hanganutziu-Deicher antigen in human colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1985;45:3796–3802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawai T, Kato A, Higashi H, Kato S, Naiki M. Quantitative determination of N-glycolylneuraminic acid expression in human cancerous tissues and avian lymphoma cell lines as a tumor-associated sialic acid by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Cancer Res. 1991;51:1242–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yin J, Hashimoto A, Izawa M, Miyazaki K, Chen GY, Takematsu H, Kozutsumi Y, Suzuki A, Furuhata K, Cheng FL, Lin CH, Sato C, Kitajima K, Kannagi R. Hypoxic culture induces expression of sialin, a sialic acid transporter, and cancer-associated gangliosides containing non-human sialic acid on human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2937–2945. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz SL, Padler-Karavani V, Ghaderi D, Hurtado-Ziola N, Yu H, Chen X, Brinkman-Van der Linden EC, Varki A, Varki NM. Sensitive and specific detection of the non-human sialic acid N-glycolylneuraminic acid in human tissues and biotherapeutic products. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byres E, Paton AW, Paton JC, Lofling JC, Smith DF, Wilce MC, Talbot UM, Chong DC, Yu H, Huang S, Chen X, Varki NM, Varki A, Rossjohn J, Beddoe T. Incorporation of a non-human glycan mediates human susceptibility to a bacterial toxin. Nature. 2008;456:648–652. doi: 10.1038/nature07428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irie A, Suzuki A. CMP-N-Acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase is exclusively inactive in humans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;248:330–333. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chou HH, Takematsu H, Diaz S, Iber J, Nickerson E, Wright KL, Muchmore EA, Nelson DL, Warren ST, Varki A. A mutation in human CMP-sialic acid hydroxylase occurred after the Homo-Pan divergence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11751–11756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou HH, Hayakawa T, Diaz S, Krings M, Indriati E, Leakey M, Paabo S, Satta Y, Takahata N, Varki A. Inactivation of CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase occurred prior to brain expansion during human evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11736–11741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182257399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kandyba AG, Kobliakov VA, Kozlov AM, Nagaev IY, Shevchenko VP, Dyatlovitskaya EV. Dihydroceramide desaturase activity in tumors. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2002;67:597–599. doi: 10.1023/a:1015562615341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kandyba AG, Somova OG, Kozlov AM, Zubova ES, Dudnik LB, Alessenko AV, Shvetz VI, Dyatlovitskaya EV. Sphingolipids of transplantable rat nephroma-RA. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2000;65:703–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomlinson RH, Gray LH. The histological structure of some human lung cancers and the possible implications for radiotherapy. Br J Cancer. 1955;9:539–549. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1955.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tei K, Kawakami-Kimura N, Taguchi O, Kumamoto K, Higashiyama S, Taniguchi N, Toda K, Kawata R, Hisa Y, Kannagi R. Roles of cell adhesion molecules in tumor angiogenesis induced by co-transplantation of cancer and endothelial cells to nude rats. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6289–6296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takada A, Ohmori K, Takahashi N, Tsuyuoka K, Yago K, Zenita K, Hasegawa A, Kannagi R. Adhesion of human cancer cells to vascular endothelium mediated by a carbohydrate antigen, sialyl Lewis A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;179:713–719. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91875-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takada A, Ohmori K, Yoneda T, Tsuyuoka K, Hasegawa A, Kiso M, Kannagi R. Contribution of carbohydrate antigens sialyl Lewis A and sialyl Lewis X to adhesion of human cancer cells to vascular endothelium. Cancer Res. 1993;53:354–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kannagi R. Carbohydrate-mediated cell adhesion involved in hematogenous metastasis of cancer. Glycoconj J. 1997;14:577–584. doi: 10.1023/a:1018532409041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwalm S, Doll F, Romer I, Bubnova S, Pfeilschifter J, Huwiler A. Sphingosine kinase-1 is a hypoxia-regulated gene that stimulates migration of human endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;368:1020–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anelli V, Gault CR, Cheng AB, Obeid LM. Sphingosine kinase 1 is up-regulated during hypoxia in U87MG glioma cells. Role of hypoxia-inducible factors 1 and 2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3365–3375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bielawska A, Crane HM, Liotta D, Obeid LM, Hannun YA. Selectivity of ceramide-mediated biology. Lack of activity of erythro-dihydroceramide. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26226–26232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hakomori SI. Structure and function of glycosphingolipids and sphingolipids: recollections and future trends. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780:325–346. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sonnino S, Mauri L, Chigorno V, Prinetti A. Gangliosides as components of lipid membrane domains. Glycobiology. 2007;17:1R–13R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwl052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonnino S, Prinetti A, Mauri L, Chigorno V, Tettamanti G. Dynamic and structural properties of sphingolipids as driving forces for the formation of membrane domains. Chem Rev. 2006;106:2111–2125. doi: 10.1021/cr0100446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hakomori S. Structure, organization, and function of glycosphingolipids in membrane. Curr Opin Hematol. 2003;10:16–24. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200301000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hakomori S, Handa K, Iwabuchi K, Yamamura S, Prinetti A. New insights in glycosphingolipid function: “glycosignaling domain,” a cell surface assembly of glycosphingolipids with signal transducer molecules, involved in cell adhesion coupled with signaling. Glycobiology. 1998;8:xi–xix. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.glycob.a018822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kannagi R, Yin J, Miyazaki K, Izawa M. Current relevance of incomplete synthesis and neo-synthesis for cancer-associated alteration of carbohydrate determinants-Hakomori’s concepts revisited. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780:525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Izawa M, Kumamoto K, Mitsuoka C, Kanamori A, Ohmori K, Ishida H, Nakamura S, Kurata-Miura K, Sasaki K, Nishi T, Kannagi R. Expression of sialyl 6-sulfo Lewis x is inversely correlated with conventional sialyl Lewis x expression in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1410–1416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyazaki K, Ohmori K, Izawa M, Koike T, Kumamoto K, Furukawa K, Ando T, Kiso M, Yamaji T, Hashimoto Y, Suzuki A, Yoshida A, Takeuchi M, Kannagi R. Loss of disialyl Lewisa, the ligand for lymphocyte inhibitory receptor Siglec-7, associated with increased sialyl Lewisa expression on human colon cancers. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4498–4505. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kannagi R, Izawa M, Koike T, Miyazaki K, Kimura N. Carbohydrate-mediated cell adhesion in cancer metastasis and angiogenesis. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:377–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kannagi R, Stroup R, Cochran NA, Urdal DL, Young WW, Jr, Hakomori S. Factors affecting expression of glycolipid tumor antigens: Influence of ceramide composition and coexisting glycolipid on the antigenicity of gangliotriaosylceramide in murine lymphoma cells. Cancer Res. 1983;43:4997–5005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merrill AH, Jr, Stokes TH, Momin A, Park H, Portz BJ, Kelly S, Wang E, Sullards MC, Wang MD. Sphingolipidomics: a valuable tool for understanding the roles of sphingolipids in biology and disease. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S97–S102. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800073-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullards MC, Allegood JC, Kelly S, Wang E, Haynes CA, Park H, Chen Y, Merrill AH., Jr Structure-specific, quantitative methods for analysis of sphingolipids by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: “inside-out” sphingolipidomics. Methods Enzymol. 2007;432:83–115. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)32004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haus JM, Kashyap SR, Kasumov T, Zhang R, Kelly KR, DeFronzo RA, Kirwan JP. Plasma ceramides are elevated in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes and correlate with the severity of insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2009;58:337–343. doi: 10.2337/db08-1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ichi I, Nakahara K, Miyashita Y, Hidaka A, Kutsukake S, Inoue K, Maruyama T, Miwa Y, Harada-Shiba M, Tsushima M, Kojo S. Association of ceramides in human plasma with risk factors of atherosclerosis. Lipids. 2006;41:859–863. doi: 10.1007/s11745-006-5041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Auray-Blais C, Cyr D, Ntwari A, West ML, Cox-Brinkman J, Bichet DG, Germain DP, Laframboise R, Melancon SB, Stockley T, Clarke JT, Drouin R. Urinary globotriaosylceramide excretion correlates with the genotype in children and adults with Fabry disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;93:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drobnik W, Liebisch G, Audebert FX, Frohlich D, Gluck T, Vogel P, Rothe G, Schmitz G. Plasma ceramide and lysophosphatidylcholine inversely correlate with mortality in sepsis patients. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:754–761. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200401-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kyogashima M, Tamiya-Koizumi K, Ehara T, Li G, Hu R, Hara A, Aoyama T, Kannagi R. Rapid demonstration of diversity of sulfatide molecular species from biological materials by MALDI-TOF MS. Glycobiology. 2006;16:719–728. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu R, Li G, Kamijo Y, Aoyama T, Nakajima T, Inoue T, Node K, Kannagi R, Kyogashima M, Hara A. Serum sulfatides as a novel biomarker for cardiovascular disease in patients with end-stage renal failure. Glycoconj J. 2007;24:565–571. doi: 10.1007/s10719-007-9053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Misonou Y, Shida K, Korekane H, Seki Y, Noura S, Ohue M, Miyamoto Y. Comprehensive clinico-glycomic study of 16 colorectal cancer specimens: elucidation of aberrant glycosylation and its mechanistic causes in colorectal cancer cells. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:2990–3005. doi: 10.1021/pr900092r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wing DR, Garner B, Hunnam V, Reinkensmeier G, Andersson U, Harvey DJ, Dwek RA, Platt FM, Butters TD. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of ganglioside carbohydrates at the picomole level after ceramide glycanase digestion and fluorescent labeling with 2-aminobenzamide. Anal Biochem. 2001;298:207–217. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagahori N, Abe M, Nishimura S. Structural and functional glycosphingolipidomics by glycoblotting with an aminooxy-functionalized gold nanoparticle. Biochemistry. 2009;48:583–594. doi: 10.1021/bi801640n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Y, Allegood J, Liu Y, Wang E, Cachon-Gonzalez B, Cox TM, Merrill AH, Jr, Sullards MC. Imaging MALDI mass spectrometry using an oscillating capillary nebulizer matrix coating system and its application to analysis of lipids in brain from a mouse model of Tay-Sachs/Sandhoff disease. Anal Chem. 2008;80:2780–2788. doi: 10.1021/ac702350g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sugiura Y, Shimma S, Konishi Y, Yamada MK, Setou M. Imaging mass spectrometry technology and application on ganglioside study; visualization of age-dependent accumulation of C20-ganglioside molecular species in the mouse hippocampus. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan K, Lanthier P, Liu X, Sandhu JK, Stanimirovic D, Li J. MALDI mass spectrometry imaging of gangliosides in mouse brain using ionic liquid matrix. Anal Chim Acta. 2009;639:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuyama Y, Dohi T, Morita H, Furukawa K, Oshima M. Enhanced expression of GM2/GD2 synthase mRNA in human gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer. 1995;75:1273–1280. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950315)75:6<1273::aid-cncr2820750609>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]