Abstract

Our laboratory has recently described a stability control region in the two-stranded α-helical coiled-coil α-tropomyosin that accounts for overall protein stability but is not required for folding. We have used a synthetic peptide approach to investigate three stability control sites within the stability control region (residues 97-118). Two of the sites, electrostatic cluster 1 (97-104, EELDRAQE) and electrostatic cluster 2 (112-118, KLEEAEK), feature sequences with unusually high charge density and the potential to form multiple intrachain and interchain salt bridges (ionic attractions). A third site (105-111, RLATALQ) features an e position Leu residue, an arrangement known previously to enhance coiled-coil stability modestly. A native peptide and 7 peptide analogs of the tropomyosin sequence 85-119 were prepared by Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis. Thermal stability measurements by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy revealed the following Tm values for the native peptide and three key analogs: 52.9°C (Native), 46.0°C (R101A), 45.3°C (K112A/K118A), and 27.9°C (L110A). The corresponding ΔTm values for the anlaogs, relative to the native peptide, are -6.9°C, -7.6°C, and -25.0°C, respectively. The dramatic contribution to stability made by L110e is three times greater than the contribution of either electrostatic cluster 1 or 2, likely resulting from a novel hydrophobic interaction not previously observed. These thermal stability results were corroborated by temperature profiling analyses using reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). We believe that the combined contributions of the interactions within the three stability control sites are responsible for the effect of the stability control region in tropomyosin, with the Leu110e contribution being most critical.

Keywords: protein stability, tropomyosin, two-stranded α-helical coiled-coil, stability control region, stability control site(s), protein folding

Introduction

For many years, the coiled-coil protein structural motif has served as a model in which protein folding, stability, and function have been investigated. The study of coiled-coils and their utility as model proteins is well established and has been extensively reviewed (Kohn et al., 1997a; Kohn and Hodges, 1998; Burkhard et al., 2001; Lupas and Gruber, 2005). However, our understanding of the rules that govern coiled-coil folding continues to broaden. Accordingly, our knowledge of coiled-coil protein function has increased, as has the practical application of coiled-coil proteins as design elements (Hodges, 1996; Woolfson, 2005; Mason et al., 2007; Grigoryan and Keating, 2008). It seems apparent that well-designed model coiled-coils will continue to provide valuable information applicable to protein folding and function. This can be attributed to the simplicity of a very familiar motif of right-handed α-helices wrapped around each other in a rope-like left-handed supercoil (Hodges, 1992). The driving force for the formation of this structure comes from the specific interactions of hydrophobic core residues (Crick, 1953) within each 3-4 or 4-3 hydrophobic repeat sequence (NXXNXXXNXXNXXXN...where N is a nonpolar residue) (Hodges et al., 1972), denoted [abcdefg]n (McLachlan and Stewart, 1975). These interactions depend on the amino acid composition at each heptad position, where the a and d positions are frequently occupied by hydrophobic residues, the e and g positions are often charged residues, and the b, c, and f positions are usually polar or charged residues (Hodges et al., 1972; Lupas et al., 1991; Woolfson, 2005). The result is a rod-like structure of amphipathic α-helices that bury their “hydrophobic faces” of a and d positions against each other in a hydrophobic core while exposing their polar “faces” (b, c, e, f, g positions) to the surrounding aqueous solvent, as shown in the first high resolution X-ray structure of a two-stranded α-helical coiled-coil, GCN4, (O'Shea et al., 1991).

Coiled-coil stability depends on a series of characteristics that contribute collectively to the overall structure. Considering the importance of hydrophobic interactions in protein folding (Pace, 1992), it follows that the interactions of residues in the core a and d positions of coiled-coils would be critical for stability (Zhou et al., 1992a,b; Thompson et al., 1993; Wagschal et al., 1999a,b; Tripet et al., 2000). Measurement of the stability contributions of 20 amino acids substituted at these positions have supported this view, with energetic differences between the most stabilizing substitutions and the most destabilizing substitutions of 6.6 kcal/mole for position a and 7.4 kcal/mol for position d (Wagschal et al., 1999a,b; Tripet et al., 2000). Furthermore, hydrophobic core stability correlates with a general trend of increasing hydrophobicity of each substituted residue side-chain (Kovacs et al., 2006), with non-polar, β-branched residues (Val and Ile) preferred at position a and non-polar (Leu) preferred at position d for optimal side-chain packing effects in two-stranded α-helical coiled-coils (O'Shea et al., 1991; Zhu et al., 1993; Moitra et al., 1997; Tripet et al., 2000). However, destabilizing residues also occur in the hydrophobic core (Lupas et al., 1991; Harbury et al., 1993; Woolfson and Alber, 1995; Akey et al., 2001; Acharya et al., 2006). Some participate in noncanonical interactions, while other destabilizing residues occur in conjunction with stabilizing contributions from surface residues at b, c, e, f, and g positions (Hodges et al., 1981; Conway and Parry, 1990; Kwok and Hodges, 2004a). For example, salt bridges (ionic / electrostatic attractions) provide stability through oppositely charged, surface-exposed residues on the same helix (intrachain, i to i+3 or i to i+4) and on different helices (interchain, i to i′+5) (Perutz, 1978; Huyghues-Despointes et al., 1993; Scholtz et al., 1993; Kohn et al., 1997b; Kohn et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2003a; Matousek et al., 2007). Both types were present in the X-ray crystallographic structure of GCN4 (O'Shea et al., 1991) and contribute 0.4 - 0.5 kcal/mol to stability (Zhou et al., 1994a,b; Kohn et al., 1997b). Another surface residue stabilizing effect occurs when Leu occupies position e or g and packs against the hydrophobic core, contributing 0.69 kcal/mol to 0.74 kcal/mol (Lee et al., 2003a). In addition to these interactions, all residues, except for proline, make individual contributions to coiled-coil stability through side-chain helical propensity (Zhou et al., 1994c). Relative helical propensity has been determined by statistical analyses of amino acid frequencies of occurrence in helical structures (Chou and Fasman, 1974; Williams et al., 1987) and by physicochemical analyses (Sueki et al., 1984, O'Neil and DeGrado, 1990). Ultimately, the intrinsic helical propensities of amino acid side-chains were shown to span an energetic range of 0.96 kcal/mol in 20 amino acid substitutions into the hydrophobic face of a model peptide amphipathic α-helix (Zhou et al., 1994c; Monera et al., 1995). Finally, interactions from residues at each heptad position culminate in a chain-length contribution to coiled-coil stability. For instance, three heptads were shown to be sufficient for the formation of a stable coiled-coil when positions a and d are occupied by five consecutive large hydrophobes (three Ile residues at position a and two Leu residues at position d) (Su et al., 1994), and providing these heptads with the interactions necessary to exceed a threshold stability value (Kwok and Hodges, 2004b; Kohn et al., 1998). Beyond this threshold, the enthalpic benefit of favorable interactions must outweigh the entropic cost of increasing helical chain length (Kwok and Hodges, 2003, 2004b). Burkhard and coworkers (2000; 2002) were able to design a two heptad coiled-coil peptide that was stabilized by a complex network of inter- and intrahelical salt-bridges in addition to the hydrophobic core interactions of Ile and Leu at positions a and d, respectively. This short peptide did contain an N-terminal succinilation motif to further stabilze the coiled-coil structure. In tropomyosin, regions of stability are distributed throughout the length of the molecule with destabilizing regions in between. Specifically, stabilizing and destabilizing clusters have been identified where three or more consecutive hydrophobic core positions are occupied by stabilizing (L, I, V, M, Y, F) or destabilizing (A, C, D, E, G, H, K, N, P, Q, R, S, T, W) residues, respectively (Kwok and Hodges, 2004a).

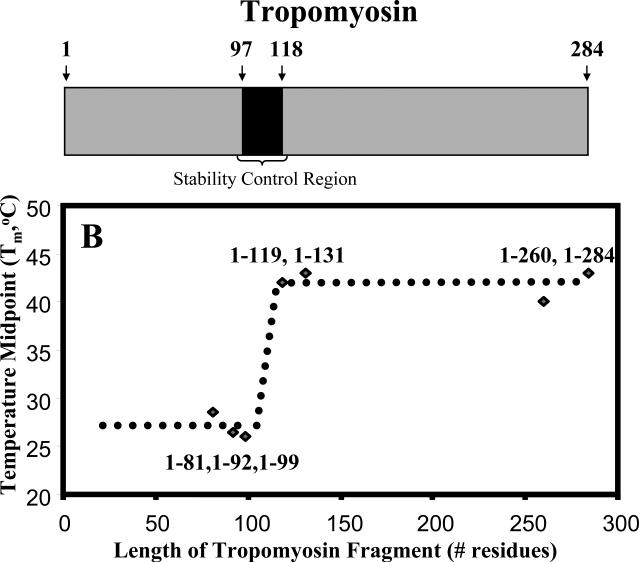

Trigger sites are another type of protein sequence element believed to affect the folding of coiled-coils (Kammerer et al., 1998). These 13-residue to 16-residue sequence regions act as nucleation domains that initiate protein folding in several coiled-coil proteins (Lupas and Gruber, 2005; Parry, 2005; Burkhard et al., 2001; Mason and Arndt, 2004), including two-stranded (Kammerer et al., 1998) and three-stranded (Frank et al., 2000) coiled-coils. Trigger sites do not require a consensus sequence if a critical threshold stability value is exceeded through any combination of the stabilizing effects previously discussed (Lee et al., 2001; Steinmetz et. al., 2007). Instead, sequences of varying amino acid composition will suffice, provided that they can form a unique hydrogen-bonding network that stabilizes α-helical monomers and promotes hydrophobic core residue interactions for coiled-coil formation (Steinmetz et. al., 2007). The existence of trigger sites is well established and, indeed, critical in some cases. For example, polypeptide fragments of the human macrophage scavenger protein oligomerization domain do not fold without a trigger site despite having a heptad repeat sequence (Frank et al., 2000). However, a defining property of the trigger site concept is its absolute effect; that is, for those proteins in which they are required, folding only occurs when a trigger site is present. This stands in contrast to a protein sequence element that does not govern folding, but instead confers final protein stability. We recently identified a stability control region in tropomyosin (97-118) that behaves in this manner (Hodges et al., 2009). We showed that C-terminal deletion fragments of tropomyosin, both with (1-119, 1-131, 1-260, 1-284) and without (1-81, 1-92, 1-99) the stability control region, were fully folded. However, these two populations exhibited a 16°C difference in thermal stability (Tm) according to thermal denaturation profiles from circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy (Hodges et al., 2009) (Figure 1). Therefore, the stability control region of tropomyosin 97-118 is not a nucleation domain that triggers folding (trigger site), but instead is a region that confers final stability on the native tropomyosin protein. We aim to further our understanding of the rules that govern coiled-coil stability through a study of the key interactions in the stability control region that are responsible for the large increase in stability when this region is added to the coiled-coil.

Figure 1.

Plot of Tm values versus fragment length for tropomyosin C-terminal deletion fragments. A distinct increase in Tm value occurs upon the addition of the TM100-119 sequence region. The sequence TM97-118 includes all the electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions that are believed to compose a stability control region in α-tropomyosin (Hodges et. al., 2009). Tm is the temperature midpoint determined from temperature unfolding experiments using circular dichroism spectroscopy (see methods).

We have investigated the stabilizing features of the α-tropomyosin stability control region 97-118 using synthetic peptides containing this sequence. The contribution of the stability control region to tropomyosin final stability is achieved by interchain and intrachain ionic attractions and a unique hydrophobic interaction from Leu residue at position 110e. These interactions reside in three stability control site sequences (two 7-mers and one 8-mer) within the stability control region. The key interactions in each of these sequences involve residues outside the hydrophobic core. Furthermore, the stability control region includes a destabilized hydrophobic core intervening sequence (Kwok and Hodges, 2004a), a surprising feature considering that this region is required for final protein stability. Although the presence of both ionic attractions and destabilized hydrophobic core residues in tropomyosin have been previously described, (Brown et al., 2001; Kwok and Hodges, 2003,2004a), these features have never been suggested as tandem components of a stability-enhancing element, nor have they been indicated as a requirement for an appropriate final tropomyosin stability. In addition, the unique hydrophobic interaction from Leu 110e is presented as a novel stabilizing interaction with a dramatic effect on regional tropomyosin stability not previously observed. Although salt bridge contributions to coiled-coil protein stability are well documented (Krylov et al., 1994; Kohn et al., 1995,1998; Krylov et al., 1998; Meier et al., 2002), their significance has also been questioned (Lumb and Kim, 1995; Lavigne et al., 1996; Phelan et al., 2002; Bosshard et al., 2004). Nevertheless, we propose that the stabilizing contributions from the salt bridge interactions and the unique Leu110e hydrophobic interaction in the stability control region of tropomyosin are critical for α-helical coiled-coil stability and are therefore likely to be significant for tropomyosin function.

Results

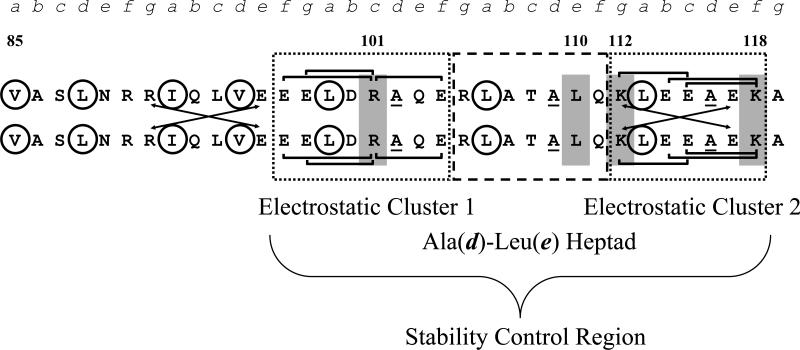

Inspection of the TM sequence region 97-118 finds Ala residues at three consecutive d positions within the hydrophobic core (Ala 102, Ala 109, and Ala 116), a destabilizing feature that is unexpectedly present in a region associated with stability (Figure 2). Since, each Ala residue at a d position is known to contribute a 3.8 kcal/mol decrease in stability compared to the more canonical d position Leu residue (Tripet et. al., 2000), the stabilizing effect of this sequence region seems counterintuitive. Furthermore, this pattern of a destabilizing residue at every other hydrophobic core position over three consecutive heptads has been previously described as an intervening sequence, having significantly less stability than a sequence composition of stabilizing hydrophobic residues (Kwok and Hodges, 2004a). Interestingly, the tropomyosin sequence region 85-99 contains a stabilizing hydrophobic cluster of five large hydrophobic residues occupying consecutive a and d positions (Kwok and Hodges, 2004a) immediately preceding the stability control region 97-118 (Figure 2). However, C-terminal deletion fragments (1-81, 1-92, and 1-99) that include this hydrophobic cluster (85-99) but lack the stability control region 97-118 do not exhibit final tropomyosin stability (Hodges et. al., 2009). Contained within the tropomyosin stability control region are three smaller sequences, two of which are enriched in charged residues and are referred to as electrostatic clusters 1 and 2 (Figure 2). The first site, 97-104, is an 8-residue sequence with five charged residues out of eight (EELDRAQE). The second site, 112-118, is a 7-residue sequence with five charged residues out of seven (KLEEAEK). Both sites were regarded as likely sources of the contributions that result in the stability observed in full-length tropomyosin. Both electrostatic clusters include a multitude of possible intrachain i to i+3 (g to c and c to f) and i to i+4 (b to f) electrostatic attractions. In addition, electrostatic cluster 2 contains interchain i to i′+5 electrostatic attractions (g to e′) that can exist simultaneously with i to i+3 or i to i+4 electrostatic attractions in the same cluster (Figures 2 and 3). Although the presence of intrachain and interchain interactions in coiled-coils is well described (O'shea et al., 1991; Kohn et al., 1997b; Kohn et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2003a) and their individual contributions to coiled-coil stability are known (0.45 kcal/mol) (Kohn et. al., 1998), the unique abundance and conservation of ionic attractions in these electrostatic cluster sequences were only recently noted (Hodges, et. al., 2009). The heptad 105-111 is present in the stability control region between electrostatic clusters 1 and 2 and contains a Leu residue at position 110e (Figure 2). This heptad is also interesting since previous experiments showed that when Leu residues occupy adjacent positions e and d or g and a, stability is increased in two-stranded α-helical coiled-coils by 0.7 kcal/mol (Lee et al., 2003a). Each of the three sites in the stability control region of tropomyosin is among the ten most conserved heptads in a database of unique heptads derived from all tropomyosin sequences (Hodges et. al., 2009).

Figure 2.

Tropomyosin sequence 85-119 used to prepare synthetic two-stranded α-helical coiled-coils. The large, stabilizing hydrophobes in the core positions are circled. Underlined Ala residues occupy three consecutive d positions (102,109,116) in this region, which usually constitutes a destabilized coiled-coil sequence. The dotted and dashed boxes highlight the tropomyosin stability control region TM97-118. The dotted boxes show electrostatic clusters 1 and 2, with a large number of intrachain and interchain ionic attractions. The dashed box shows the Ala(d)-Leu(e) heptad. The brackets denote i to i+3 and i to i+4 intrachain electrostatic attractions. The arrows denote i to i′+5 interchain electrostatic attractions. The TM85-96 sequence was included in the synthetic peptides to ensure adequate coiled-coil stability to measure the effects of amino acid substitutions in the region 97-119. R101c, Leu110e, K112g, and K118f are shaded.

Figure 3.

Cross-sectional representation of the two-stranded α-helical coiled-coil interactions in the heptad TM112-118. The unique aspect of this heptad is the multitude of ionic interactions, both intrachain and interchain. Each Lys residue has more than one possible ionic attraction. Dotted arrows show i to i+3 and i to i+4 intrachain electrostatic attractions. Dashed arrows show i to i′+5 interchain electrostatic attractions. The heptad sequence is shown at the bottom of the figure with brackets indicating the intrachain electrostatic attractions.

In order to investigate the significance of electrostatic clusters 1 and 2, and Leu 110e in controlling protein stability, a series of synthetic coiled-coil peptides was prepared (Figure 4). The peptides included the native tropomyosin 85-119 coiled-coil sequence, and seven analogs containing either single substitutions (R101A, L110A, K112A, K118A), double substitutions (R101A/L110A, K112A/K118A), or multiple substitutions (R101A/L110A/K112A/K118A). Each of these synthetic peptides contained the stabilizing contributions of a hydrophobic cluster of large hydrophobes at positions a and d (V85, L88, I92, V95, and L99) in the 85-99 region and an N-terminal Cys-Gly-Gly linker. The flexible Cys-Gly-Gly linker allows the formation of an N-terminal disulfide-bridged two-stranded coiled-coil monomer (Zhou et al., 1992a,b, 1993; Wagschal et al., 1999b). This design eliminates the monomer-dimer equilibrium that can obscure accurate comparison of analogs due to variations in concentration. It also attempts to ensure that the native peptide sequence and analogs will have a measurable stability, such that the stability of the analogs can be compared to the native sequence and to each other. Ala is the preferred substituting residue because it readily adopts α-helical structure and its small, hydrophobic side-chain cannot participate in the interactions of interest in the native sequence. For example, the K112A substitution removes an interchain i to i′+5 attraction with E117 and an intrachain i to i+3 attraction with E115, whereas, the K118A substitution removes an intrachain i to i+3 attraction with E115 and an intrachain i to i+4 attraction with E114. Together, the K112A/K118A analog lacks all electrostatic attractions associated with electrostatic cluster 2 (Figures 2 & 3). In contrast, the R101A single substitution eliminates all i to i +3 intrachain electrostatic attractions with E98 and E104 and the i to i + 4 intrachain electrostatic attraction with E97 in each polypeptide chain associated with electrostatic cluster 1 (Figure 2). Finally, the L110A substitution removes any stabilizing hydrophobic contribution from Leu at position e in each polypeptide chain of the coiled-coil.

Figure 4.

Sequences of synthetic two-stranded α-helical coiled-coils used in this study. Native residues substituted with Ala residues are bolded. An N-terminal C-G-G linker was designed into the sequences for disulfide bond formation in order to eliminate monomer-dimer equilibrium effects and provide additional stability. All peptides were N-terminally acetylated and C-terminally amidated to eliminate end/end charge repulsions during biophysical analysis. The heptad positions are labeled a,b,c,d,e,f,g.

The native peptide CD spectrum in benign conditions (100mM KCl, 50mM PO4, pH 7) shows a molar ellipticity of a larger negative value at 222nm than the value at 208nm. The resulting [θ]222/[θ]208 ratio is greater than 1 (Figure 5, Panel A; Table 1) and indicates a folded coiled-coil (Chen et al., 1974; Cooper and Woody, 1990; Zhou et al., 1992b). In the presence of 50% TFE, α-helical peptides yield a [θ]222/[θ]208 ratio that is less than 1, which indicates predominant monomeric α-helical structure (Table 1) (Chen et al., 1974; Cooper and Woody, 1990; Lau et al., 1984a,b). The use of TFE in the study of protein folding and stability has been thoroughly described (Sönnichsen et al., 1992). The native TM85-119 peptide showed no induction of ellipticity in the presence of 50% trifluoroethanol (TFE), indicating that it is fully folded (Figure 5, Panel A; Table 1). Compared to the native peptide, all analogs but two (R101A/L110A and R101A/L110A/K112A/K118A) yielded a [θ]222/[θ]208 ratio greater than 1 in benign conditions, but all analogs had less negative ellipticity values than the native peptide at [θ]222 (Figure 5, Panel B; Table 1). The [θ]222/[θ]208 ratios suggest that the native peptide and 5 of 7 analogs are folded as coiled-coils, but the extent of analog folding progressively decreases in a manner consistent with the expected destabilizing effects of the analog substitutions in these coiled-coils. Compared to the native peptide ellipticty value at [θ]222 (-36,213 deg·cm2·dmol-1) , the R101A, K112A/K118A, and L110A analogs had less negative ellipticity values of -34,390, -29,457, and -25,057 deg·cm2·dmol-1, respectively (Table 1). The ellipticity results shown in Table 1 suggest a fundamental difference in the L110A analog that prevents it from folding to the same extent as the R101A, K112A/K118A, and native peptide, even in the presence of 50% TFE. The most significant losses of folding were observed for the double substituted analog, R101A/L110A, and the quadruple substituted analog, R101A/L110A/K112A/K118A, where they were only partially folded in benign conditions. These peptides demonstrated a dramatic increase in α-helical content in the presence of 50% TFE (Table 1). The R101A/L110A/K112A/K118A analog resulted in the most dramatic effect, yielding a [θ]222 value that was significantly less negative than the native peptide and all other analogs in benign conditions (Table 1).

Figure 5.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra showing molar ellipiticity versus wavelength for native TM85-119 and key analogs at 5°C. Panel A shows overlaid spectra of the native TM85-119 in benign conditions (100mM KCl, 50mM PO4, pH7) and in buffer containing 50% trifluoroethanol (TFE) (v/v). Panel B shows CD spectra of three analogs compared to TM85-119 in benign conditions. Panel C shows CD spectra of three analogs compared to TM85-119 in 50% TFE.

Table 1.

Biophysical data for the disulfide-bridged two-stranded α-helical coiled-coils native TM85-119 and analogs.

| TM85-119 | [θ]222a (deg cm2 dmol-1) | [θ]222/[θ]208b (deg cm2 dmol-1) | Benignc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | Substitution(s) | Benign | 50% TFE | Benign | 50% TFE | %Helix | Tmd | ΔTme | PA,Maxf |

| Native | None | -36,213 | -30,062 | 1.08 | 0.96 | 104 | 52.9 | - | 3.4 |

| TM1 | K112A | -31,691 | -28,644 | 1.09 | 0.96 | 91 | 49.3 | 3.6 | 2.7 |

| TM2 | K118A | -30,548 | -29,381 | 1.08 | 0.97 | 87 | 48.7 | 4.2 | 2.7 |

| TM3 | K112A/K118A | -29,457 | -29,105 | 1.08 | 0.97 | 84 | 45.3 | 7.6 | 2.4 |

| TM4 | R101A | -34,390 | -29,099 | 1.08 | 0.96 | 98 | 46.0 | 6.9 | 1.8 |

| TM5 | L110A | -25,057 | -25,158 | 1.04 | 0.97 | 72 | 27.9 | 25.0 | 0.7 |

| TM6 | R101A/L110A | -18,239 | -31,366 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 52 | <5 | - | 0 |

| TM7 | R101A/L110A/K112A/K118A | -9,578 | -24,131 | 0.86 | 0.97 | 27 | <5 | - | 0 |

Mean residue ellipticity from CD spectra at 222 nm in benign buffer (100mM KCl, 50mM PO4, pH 7) and in 50/50 benign buffer/2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (v/v). Peptide concentrations ranged from 211μm to 265μm. Spectra were measured at 5°C.

Ratio of mean residue ellipticity at 222 nm and 208 nm (same conditions as ina).

Percent helix is calculated from [θ]nH = [θ]∞H(1 - k/n) where [θ]∞H = -37,400 deg·cm2·dmol-1 for a helix of infinite length, n is the number of residues in the helix, and k is a wavelength dependant constant (2.5 at 222 nm). For a 38-residue peptide, the theoretical value for 100% helix is -34,939 deg·cm2·dmol-1 (Chen et al., 1974).

Tm is the temperature at which 50% of the peptide is unfolded. Measured by circular dichroism spectroscopy.

Change in Tm relative to the native peptide.

Maximum association parameter is a measure of polypeptide chain self-association to form the disulfide-bridged two-stranded α-helical coiled-coil (see methods for calculation).

In order to compare the thermal stabilities of the native TM85-119 peptide and analogs, thermal denaturation profiles of the native synthetic coiled-coil and three analogs were generated by CD spectroscopic analysis at 222 nm over a temperature range of 5°C to 85°C (Figure 6). Compared to the native sequence, the removal of the ionic attractions from electrostatic clusters 1 (R101A) and 2 (K112A/K118A) resulted in 6.9°C and 7.6°C reductions (ΔTm) in thermal stability, respectively (Table 1). However, we were surprised to find that the modification of the hydrophobic residue L110e (L110A), resulted in the largest decrease in stability (ΔTm = -25.0°C) compared to the native sequence, despite its location outside the hydrophobic core at position e (Table 1). While the loss of electrostatic clusters 1 and 2 did result in a very significant decrease in thermal stability in TM85-119, the stability contribution of the L110e in this sequence is three times greater than the contribution of either electrostatic cluster 1 or 2 (R101A and K112A/K118A) (Table 1). The thermal denaturation profile suggests that L110 has a dramatic effect on thermal stability in this region of TM unlike any previously observed. The significance of all three stability control sites is further confirmed by the stabilities of the double (R101A/L110A) and quadruple (R101A/L110A/K112A/K118A) substituted analogs, whose Tm values were less than 5°C, since these coiled-coils were only ~50% and 25% folded, respectively, at 5°C. For these peptide analogs, the loss of stabilizing interactions from 2 or 3 stability control sites dramatically disrupts their folding.

Figure 6.

Thermal denaturation profile of native TM85-119 and key analogs by circular dichroism spectroscopy. The key analogs R101A, K112A/K118A, and L110A, were predicted to eliminate all stabilizing electrostatic interactions associated with electrostatic cluster 1 and electrostatic cluster 2, as well as the hydrophobic interactions associated with the Ala(d)-Leu(e) heptad, respectively, within the α-TM stability control region.

In addition to CD spectroscopy based experiments, we used a reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) temperature profiling technique developed by the Hodges laboratory (Lee et al., 2003b; Mant et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2005). This approach utilizes RP-HPLC analyses of samples at different temperatures to evaluate peptide self-association, where the amount of thermal energy required to disrupt peptide self-association can be related to peptide stability in terms of changes in retention time (tR). These changes depend on two equilibria within the system, one that describes the partitioning of the peptide on and off the column stationary phase (K1) and another (K2) that describes the structural changes of the peptide in the mobile phase during partitioning (Figure 7). In order for coiled-coil peptides to be retained, the helices must dissociate to allow the hydrophobic core residues to bind the stationary phase (K1). However, increased stability favors peptide self-association and coiled-coil formation, allowing the peptide to have a lower retention time. The change in retention time normalized to 5°C, with respect to temperature, is called the association parameter, PA. The maximum PA value, PA,Max, corresponds to the highest temperature at which peptide self-association (coiled-coil structure) is maintained (Figure 7 and 8). Beyond this critical temperature, the peptide incurs no further coiled-coil formation and exhibits a linear decrease in tR with increasing temperature (Mant et al., 2003). Therefore, a larger PA,Max value corresponds to greater peptide self-association and higher stability, whereas, a peptide with a PA,Max value of zero or less indicates that peptide self-association never occurs. The native peptide displayed the largest PA,Max value, followed by the peptide analogs, in order of decreasing stability, in a manner consistent with the CD results (Figure 8; Table 1). Among the peptides with a PA,Max value greater than zero (peptides that exhibit self-association), the most dramatic reduction in PA,Max was observed for the L110A analog, relative to the native peptide. As with the CD results, these data show that the effect of the L110A substitution was much greater than the effect of either the R101A or the K112A/K118A analog (Table 1). The R101A/L110A and R101A/L110A/K112A/K118A analogs yielded PA,Max values of zero, indicating very little or no structural change during the temperature profile analysis. This was also consistent with the CD results, which showed that these analogs had Tm values that were less than 5°C (Table 1). Collectively, our results show that the systematic loss of stability control sites leads to a progressive loss of stability throughout the stability control region of TM, with the L110e stability control site (RLATALQ) being most critical to stability.

Figure 7.

A schematic example of the changes in peptide self-association during reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) temperature profiling. RP-HPLC profiles were generated for the coiled-coil peptides in 3°C increments between 5°C and 80°C for a total of 25 runs (see methods). During peptide elution, the hydrophobicity of the reversed-phase matrix dissociates the helices of the coiled-coil so that the hydrophobic surfaces of the amphipathic α-helices can interact with the matrix. This partitioning between the stationary phase and the mobile phase can be described by two equilibria, K1 and K2. K1 represents the equilibrium between the matrix-bound and unbound forms of the peptide. K2 represents the equilibrium between folded, coiled-coil peptides and peptides with dissociated helices. As temperature increases from 5°C to 80°C over multiple RP-HPLC runs in a temperature profile, the partitioning mechanism progresses from stage 1 through stage 4. Stage 1: The K2 equilibrium favors coiled-coil formation in the mobile phase and less peptide retention. Stage 2: The K2 equilibrium favors the formation of peptides with dissociated helices, less coiled-coil formation, and increased retention. Stage 3: The K2 equilibrium still favors peptides with dissociated helices, but also marks beginning of the temperature unfolding of the α-helices and the appearance of random coil peptide. At this temperature no folded coiled-coil is observed. Stage 4: The K2 equilibrium strongly favors a higher concentration of random coil peptide at the higher temperature.

Figure 8.

A plot of peptide self-association by RP-HPLC temperature profiling. RP-HPLC runs of native TM85-119, four analogs, and a random coil control peptide were performed at increasing temperatures ranging from 5°C to 80°C and their retention times were normalized to 5°C (Panel A, see methods for details). The normalized random coil control peptide data were subtracted from the profile data of native TM85-119 and analogs to generate the plots shown in Panel B. The native peptide showed the greatest tendency to self-associate while the L110A analog showed the least amount of measurable self-association. The multiple substituted analog R101A/L110A/K112A/K118A does not associate at 5°C. The degree of self-association directly correlates with coiled-coil stability. The PA,Max values for two of the coiled-coil peptides are indicated by the arrows. The dotted line at zero represents the random coil control peptide which shows a linear decrease in retention time with increasing temperature (Panel A) and no self-association or change in conformation over the temperature range 5°C to 80°C.

An outstanding feature of the L110e stability control site (RLATALQ) is the presence of a destabilizing Ala residue at position 109d. In order to understand the effect of the Ala at position d, we examined the crystal structures of tropomyosin 1-81 (PDB ID: 1IC2) and 89-203 (PBD ID: 2B9C) (Brown et al., 2001; Brown et al., 2005). Using the coiled-coil analysis program TWISTER (Strelkov and Burkhard, 2002), we examined the coiled-coil radius in various regions of tropomyosin compared to our stability control region to see if a decrease in radius might lead to improved packing in the hydrophobic core and explain the enhanced stability. The results of our analysis are shown in Table 2. The canonical sequence regions L39d, L43a, L46d, and L50a (Region A), and L193d, L197a, V200d, L204a, and L207d (Region B) have average radii of 5.02 Å and 4.99 Å, respectively. Similarly, non-canonical sequence regions like L64a, A67d, L71a, and A74a (Region C) and the stability control region L106a, A109d, L113a, and A116d (Region D) have average radii of 4.86 Å and 4.74 Å, respectively. We believe, this very small difference in the hydrophobic core radius of the stability control region, in which alternating Ala residues are present in the hydrophobic core (Region D), compared to the canonical sequences with all Leu residues in the hydrophobic core (Regions A and B), is not significant to account for any change in stability. The radius of tropomyosin is essentially the same in our critical interactions sequence as that found for a canonical TM sequence. However, the sequence region of A151d, A155a, and A158d (Region E) has an average radius of 4.27 Å (Table 2). This clear difference in coiled-coil radius, surrounding consecutive Ala residues in the hydrophobic core, is significant. The collapsing of the radius in this region allows for an increase in van der Waals interactions, exclusion of water from the core, and the destablizing effect of Ala residues in the core are less destructive than a single Leu to Ala substitution where the radius is larger in the canonical sequences.

Table 2.

Comparison of coiled-coil radii at hydrophobic core a and d positions in selected regions of tropomyosin.

| Region Ab | Region Bb | Region Cb | Region Db | Region Eb | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residue | Pos.c | Radiusa | Residue | Pos.c | Radiusa | Residue | Pos.c | Radiusa | Residue | Pos.c | Radiusa | Residue | Pos.c | Radiusa |

| L39 | d | 4.82 | L193 | d | 5.01 | L64 | a | 4.73 | L106 | a | 4.73 | A151 | d | 4.33 |

| L43 | a | 5.10 | L197 | a | 5.04 | A67 | d | 4.78 | A109 | d | 4.76 | A155 | a | 4.22 |

| L46 | d | 5.19 | V200 | d | 5.04 | L71 | a | 5.00 | L113 | a | 4.70 | A158 | d | 4.27 |

| L50 | a | 4.98 | L204 | a | 4.89 | A74 | d | 4.92 | A116 | d | 4.75 | |||

| L207 | d | 4.99 | ||||||||||||

| AVGd | 5.02 | 4.99 | 4.86 | 4.74 | 4.27 | |||||||||

Radii were calculated using the coiled-coil analysis program Twister (Strelkov and Burkhard, 2002).

Sequence regions A-E are labeled according to similar composition rather than tropomyosin sequence order.

Heptad position (abcdefg)n where a and d are the hydrophobic core residues.

Average Radius.

Considering the stabilizing effect of Leu110e, it is reasonable to conclude that this Leu residue somehow promotes a more favorable coiled-coil packing, resulting in the enhanced stability observed. To evaluate this idea, we performed accessible surface area calculations for specific residues throughout the tropomyosin sequence, including the stability control region. We used the areaimol program from the CCP4 suite of protein crystallographic tools to evaluate the PDB files 1IC2 and 2B9C. The packing of hydrophobic surface area for selected tropomyosin residues and regions were deduced from these calculations. Furthermore, both of these PDB files were modified and separately saved to create additional PDB files containing chain A or chain B coordinates only. In this way we could evaluate both monomeric and dimeric hydrophobic accessible surface area and observe any changes between the two upon coiled-coil formation. Table 3 shows our comparison of monomeric and dimeric hydrophobic accessible surface area and buried hydrophobic surface area values for individual residues in sequence regions 1-3, for all residues in sequence regions 1-3, and for all residues in the L110A analog sequence region 1*. We first wanted to demonstrate that buried hydrophobic surface area correlates with coiled-coil stability. For example, if we compare region 2 (L43a, L46d, L50d ) with region 3 (L64a, A67d, L71d) the buried hydrophobic surface areas in the coiled-coil dimers are 724.8 Å2 and 571.0 Å2, respectively (Table 3). This difference of 153.8 Å2 in buried hydrophobic surface area at 24 cal/Å2 (Raschke et al., 2001) accounts for 3.69 kcal/mol, which agrees with the experimental value determined by Tripet et al (2000) of 3.8 kcal/mol for the decrease in coiled-coil stability of a Leu at position d being substituted by an Ala at position d. L46d is an example of a Leu residue within a canonical tropomyosin sequence region which is surrounded by Leu residues on each side in the hydrophobic core (L43a, L46d, and L50a). L46d buries 55.2 Å2 in the monomer and 227.4 Å2 in the dimer. In contrast, L110e buries double the hydrophobic area in the monomer (109.3 Å2) and slightly more than half of the hydrophobic surface are in the dimer (143.3 Å2), or 63%, compared L46d. The percent increase in buried hydrophobic surface area for L46d, in going from the monomer to the dimer, was 62.9%, whereas, for L110e the percent increase in buried area in going from the monomer to the dimer was 12.4%. This strongly suggests that L110e is more important for stabilizing the monomeric α-helices rather than the coiled-coil dimer compared to a Leu residue at position d.

Table 3.

Hydrophobic accessible surface area changes for residues of interest in tropomyosin.

| Sequence Region | Residues/Positions of Interest | Residues Evaluated | Theoretical Hydrophobic Accessible Surface Areaa | Monomerb Observed ASA | Monomer Buried Area | Monomer % Buried | Dimerb Observed ASA | Dimer Buried Area | Dimer % Buried | % Increase Buried Areac | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | d | e | a | ||||||||||

| 1 | L106 | A109 | L110 | L113 | L110e | 274 | 164.7 | 109.3 | 39.9 | 130.7 | 143.3 | 52.3 | 12.4 |

| 2 | L43 | L46 | L50 | L46d | 274 | 218.8 | 55.2 | 20.1 | 46.6 | 227.4 | 83.0 | 62.9 | |

| 3 | L64 | A67 | L71 | Ala67d | 134 | 86.3 | 47.7 | 35.6 | 11.6 | 122.4 | 91.3 | 55.7 | |

| 1 | L106 | A109 | L110 | L113 | All | 956 | 682.3 | 273.7 | 28.6 | 265.3 | 690.7 | 72.2 | 43.6 |

| 2 | L43 | L46 | L50 | All | 822 | 618.5 | 203.5 | 24.8 | 97.2 | 724.8 | 88.2 | 63.4 | |

| 3 | L64 | A67 | L71 | All | 682 | 514.7 | 167.3 | 24.5 | 111 | 571.0 | 83.7 | 59.2 | |

| 1* | L106 | A109 | A110 | L113 | All | 816 | 655.5 | 160.5 | 19.7 | 250 | 566.0 | 69.4 | 49.7 |

Accessible surface area (ASA) values (Å2) for individual amino acid residue side chains (Leu, 137 Å2; Ala, 67 Å2) were obtained from Miller et al., 1987 (see methods). The theoretical ASA is the sum of the ASA values for the noted residue(s), multiplied by 2 to account for the two coiled-coil chains.

Observed ASA (Å2) was determined using the areaimol program from the CCP4 suite of protein crystallography tools (Acta Cryst., 1994) and coordinates from PDB files for structures of tropomyosin 1-81 (1IC2) and 98-208 (2B9C). Monomer calculations were performed for chain A and Chain B coordinates individually. Dimer calculations were performed for both chain A and chain B coordinates simultaneously within the coiled-coil (see methods). Buried Area = Theoretical ASA - Observed ASA

% Increase Buried Area = [(Dimer Buried Area/Theoretical ASA) - (Monomer Buried Area/Theoretical ASA)]*100. This describes the change in hydrophobic surface area between monomer and dimer.

L110A substitution.

We also determined the hydrophobic accessible and buried surface areas for multiple hydrophobic residues in defined regions of tropomyosin (Table 3). To understand the contribution of L110e to stability, we compared the buried surface area in the monomer and the dimer of the L106a, A109d, L110e, and L113a (Region 1) to the A110e analog (L106a, A109d, A110e, and L113a, Region 1*). For Region 1, the hydrophobic surface area buried in the monomer was 273.7 Å2, compared to 160.6 Å2 for the A110e analog. This difference of 113.2 Å2 (2.7 kcal/mol, Table 4) shows the importance of L110e in stabilizing the monomeric α-helix. For Region 1, the hydrophobic surface area buried in the dimer was 690.7 Å2, compared to 566.0 Å2 for the A110e analog. This difference of 124.7 Å2 again shows the importance of L110e in stabilizing the coiled-coil dimer. A buried surface area of 124.7 Å2 can account for 3.0 kcal/mol in stability (Table 4). Thus, 91% of the stability increase by L110e is arising from stabilizing the monmeric α-helices.

Table 4.

Hydrophobic transfer free energy associated with selected regions in tropomyosin.

| Selected Sequencea | Comparison Sequence | Δ Buried Surface Area Monomeric α-Helices (Å2) | ΔΔGtr Monomeric α-Helices (kcal/mol) | Δ Buried Surface Area Dimeric Coiled-Coil (Å2) | ΔΔGtr Dimeric Coiled-Coil (kcal/mol) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | d | e | a | a | d | e | a | ||||

| L106 | A109 | L110 | L113 | L106 | A109 | A110 | L113 | 113.2 | 2.70 | 124.7 | 3.00 |

| L106 | A109 | L110 | L113 | L64 | A67 | --- | L71 | 106.4 | 2.55 | 119.7 | 2.87 |

| L43 | L46 | --- | L50 | L64 | A67 | --- | L71 | 36.2 | 0.87 | 153.8 | 3.69 |

| L106 | A109 | L110 | L113 | L43 | L46 | --- | L50 | 70.2 | 1.68 | -34.1 | -0.82 |

The buried surface area for the monomeric α-helices or dimeric coiled-coil of the comparison sequence are subtracted from the selected sequence. Thus, a positive value is a greater surface area buried in the selected sequence. Similarly, a positive value for ΔΔGtr means that the selected sequence is more stable than the comparison sequence. A negative ΔΔGtr value means that the comparison sequence is more stable than the selected sequence.

When the L110e (L106a, A109d, L110e, and L113a, Region 1; Table 3) is compared to the canonical sequence region 2, which also has three Leu residues to stabilize the coiled-coil (L43a, L46d, and L50a). The buried surface area in the monomer for the L110e region is 273.7 Å2, compared to region 2 of 203.5 Å2, for a difference of 70.2 Å2. This suggests that the monomer of the L110e region (region 1; Table 3) is more stable than the canonical sequence monomer by 1.68 kcal/mol (Table 4). However, the surface area buried in the dimer is greater for the canonical sequence compared to the L110e sequence (724.8 Å2 for region 2 compared to 690.7 Å2 for region 1; Table 3). In other words, the coiled-coil with A109d/L110e is less stable by 34.1 Å2 (0.8 kcal/mol) than the canonical Leu at 109d. This suggests that there is no advantage of the A109d/L110e sequence over the canonical sequence (Leu at 109d), as far as overall coiled-coil stability is concerned; except that A109d/L110e does provide a dramatic increase in stability of the monmeric α-helices (Table 4).

The comparison in Table 3 of region 1 (L106a, A109d, L110e, and L113a) to region 3, which has 3 of 4 residues in region 1 (L64a, A67d, and L113a), provides an estimate of the contribution of L110e. The monomeric buried surface area for region 1 is 273.7 Å2, compared to 167.3 Å2 for region 3, a difference of 106.4 Å2. This suggests that region 1 would be more stable in the monmeric α-helices by 2.55 kcal/mol. On the other hand, the buried surface area in the dimer of region 1 is 690.7 Å2, compared to 571.0 Å2 for region 3, for a difference of 119.7 Å2 which is equivalent to 2.87 kcal/mol (Table 4). Thus, adding an additional Leu residue at position e (La, Ad, Le, La) dramatically increased coiled-coil stability compared to an La, Ad, La sequence. However, 89% of the stability increase in arising from stabilizing the monomeric α-helices.

Overall, these results support the concept of stabilization of the monomeric helices by the Leu at position e, which translates into increased coiled-coil stability. The difference is, that the individual α-helices can breath or fluctuate without destabilizing the coiled-coil.

Discussion

Previously reported chain length (Kwok and Hodges, 2004b) and stability studies (Wagschal et. al., 1999a,b; Tripet et. al., 2000) clearly predict the TM stability control region 97-118 to be destabilized, with three alanine residues present at consecutive hydrophobic core d positions 102, 109, and 116. Since the opposite was found to be true (Hodges et. al., 2009), we know that the stability control sites within this region are not only able to overcome the destabilizing effects of the alanine residues in the hydrophobic core but also increase the stability of the coiled-coil. Electrostatic clusters 1 and 2 were initially suspected as the key stabilizing elements because of their high charge density, multiple potential salt bridge interactions per stability control site, conservation among all tropomyosin sequences (Hodges et. al., 2009), and a multitude of previous conclusions attesting to salt bridge contributions to stability (Zhou et al., 1994a,b; Kohn et al., 1997b; Kohn et al., 1998; Meier et al., 2002; Burkhard et al., 2000, 2002). This is consistent with the abundance of salt bridge networks found in thermophilic proteins, where functional structure must be maintained in the presence of larger disordering forces (Nussinov and Kumar, 2002). In addition, molecular dynamics calculations show that as temperature increases, computed root mean square fluctuations of backbone and side-chain atoms (configurational entropies) are distinctly less in salt bridges than in neutral amino acids, indicating that well designed salt bridge networks effectively accommodate the disorder of increased thermal motion (Missimer et al., 2007). However, controversy remains over the significance of salt bridge interactions and their contribution to stability, due in part to conflicting experimental results and a concern that there is no definitive experimental approach to quantify salt bridge energetics precisely (Lumb and Kim, 1995; Lavigne et al., 1996; Lumb and Kim, 1996; Phelan et al., 2002; Bosshard et al., 2004). One way to avoid this issue is by using a statistical analysis of a database of coiled-coil structures known to contain salt bridges, where salt bridge configurations occurring most frequently and with the highest probability of formation are considered to be the most stabilizing (Meier and Burkhard, 2006; Matousek et al., 2007). However, the stabilizing effect may be just as significant between an ion and its environment as it is from an ion pair (Matousek et al., 2007). Regardless of persisting differences in scientific approach or interpretation of results, our peptide analogs indicate that electrostatic clusters 1 and 2 are significant to the contribution of the stability control region in tropomyosin, since R101A and K112A/K118A account for changes in Tm of 6.9°C and 7.6°C, respectively (Table 1). However, we were surprised to observe the dramatically larger stabilizing effect of the Leu at postion 110e, which makes a 3-fold greater contribution to stability than either of the electrostatic clusters, as L110A resulted in a change in Tm of 25°C. Although it had been shown previously that Leu residues in positions e and g of coiled-coils can contribute to protein stability (Lee et. al., 2003a), the magnitude of the effect observed here was far more than previously reported and is unprecedented to our knowledge. One explanation for this observation is that the Ala109d-Leu110e arrangement in tropomyosin allows for a unique packing that is critical for the stability of the individual α-helices, and presumably, function. This sequence region of tropomyosin was included in a construct that yielded a crystal structure of a tropomyosin fragment (89-208) fused to GCN4 (8-33) at the C-terminus of the tropomyosin fragment (Brown et. al., 2005). Residues 89-105 were unfortunately disordered or only partially modeled in the structure, thus we could not observe the complete stability control region 97-118. However, the sequence 106-118 is shown as a two-stranded coiled-coil, allowing us to examine the interactions surrounding the critical Leu110 (Figures 9 and 10). Figure 9 shows a graphic representation of the α-tropomyosin two-stranded α-helical coiled-coil region 106-113 (L106ATAL110QKL113) (top left and bottom left) compared to the Leu110Ala mutant (top right and bottom right). The packing of Leu 106 and Leu 113 at positions a show excellent van der Waals interaction between the two chains, as expected for coiled-coils. The closest carbon-carbon distance for Leu 110e chain 1 to Leu 110e chain 2 is 8.12Å, suggesting no interactions between the two chains (top left, Figure 9). However, the intrachain interactions along the individual α-helices are most appropriate to create a continuous hydrophobic surface (Leu 106δ to Leu 110δ of 3.47Å and Leu 110δ to Leu 113δ of 4.44Å). This is best shown in the space-filling representation in the bottom left of Figure 9. The mutant coiled-coil Leu110Ala (top right and bottom right, Figure 9) shows the loss of hydrophobic interactions along the α-helix of each chain and the resulting increased distances (Ala 110β to Leu 106δ of 5.74Å and Ala 110β to Leu 113δ of 5.66Å (top right and bottom right, Figure 9). These distances are considerably larger than in the native sequence (see above). Figure 10 clearly shows the hydrophobic surface created on each α-helix between Leu 106, Leu 110, Leu 113 (left side). This hydrophobic surface is clearly disrupted in the Leu110Ala mutant (right side).

Figure 9.

Graphic representation of the α-tropomyosin two-stranded α-helical coiled-coil region 106-113 from the X-ray structure determined by Brown et al., 2005 (PDB ID code 2B9C). Top left: Stick representation of the native structure denoted Leu 110. The closest interchain carbon-carbon distances are shown between Leu 106δ chain 1 and Leu 106δ chain 2 of 3.27Å, Leu 113δ chain 1 and Leu 113δ chain 2 of 3.75Å, and Leu 110δ chain 1 to Leu 110δ chain 2 of 8.12Å. The closest intrachain carbon-carbon distances are shown between Leu 110δ and Leu 106δ of 3.47Å and Leu 110δ and Leu 113δ of 4.44Å. Top right: Stick representation of the Leu110Ala mutant. The closest interchain carbon-carbon distances are shown between Ala 110β chain 1 and Ala 110β chain 2 of 8.76Å. The closest intrachain carbon-carbon distances are shown between Ala 110β and Leu 106δ of 5.74Å and Ala 110β and Leu 113δ of 5.66Å. Bottom left: Space-filling representation of the native structure denoted Leu 110. The side-chains of Leu 106, Ala 109, Leu 110, and Leu 113 in each chain are shown as spheres. Bottom right: Space-filling representation of the Leu110Ala mutant. The side-chains Leu 106, Ala 109, Ala 110, and Leu 113 in each chain are shown as spheres.

Figure 10.

Graphic representation of the hydrophobic surface of one α-helical strand of the coiled-coil region 106-113. Space-filling representation of the native sequence where the side-chains of Leu 106, Ala 109, Leu 110, and Leu 113 are shown as spheres (left side) and the side-chains of the mutant Leu110Ala of Leu 106, Ala 109, Ala 110, and Leu 113 are shown as spheres (right side).

What is the basis of the preference for Alad-Leue over a more canonical, and certainly more stable, Leud arrangement that is most often encountered in coiled-coils? It may be that a Leud arrangement would make this region too stable, considering that local destabilization and flexibility have been shown to be required for tropomyosin and actin binding (Brown et al., 2001; Singh and Hitchcock-DeGregori, 2003; Brown et al., 2005; Singh and Hitchcock-DeGregori, 2006). Accordingly, we envision that the interactions within the stability control region stabilize the individual α-helices of the tropomyosin coiled-coil within this region while allowing the two α-helices to breath or fluctuate due to the presence of three consecutive Ala residues at positions d (Ala 102, Ala 109, Ala 116). Thus, nature stabilizes the individual α-helices with electrostatic clusters 1 and 2 (stability control sites, Figure 2) and by hydrophobic surface stabilization through interactions with Leu 110e. This allows the α-helices to move independently of one another without extensive hydrophobic core stabilization. With the canonical packing of hydrophobes at positions a and d, the α-helices are “locked” into a coiled-coil structure, instead of α-helices that can fluctuate or separate as required for interactions with other proteins in the context of function.

We are promoting the idea that variations in regional protein stability are required for proper tropomyosin function. For instance, globular proteins exhibit regional protein stability in the form of two types of observed flexibility: first, systemic flexibility, from small-scale side-chain and main-chain fluctuations that are propagated throughout a structure; second, segmental flexibility, where the motion of one part of a protein with respect to another is restricted to a small region of the protein and is associated with function (Nussinov and Kumar 2002). We propose that the stability control region provides segmental flexibility to tropomyosin in this region, while maintaining stabilized, individual α-helices.

Materials and Methods

Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis

Solid-phase peptide synthesis was performed manually in the manner first described by Merrifield (Erickson and Merrifield, 1976) using Fmoc chemistry (Fields and Noble, 1990). Briefly, 150mg - 300mg of Rink amide MBHA (4-methylbenzhydrylamine) resin (EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ) with 0.66 mmol/g substitution was used for each synthesized peptide. Active ester formation and coupling of N-terminally protected amino acids (5 fold excess to the α-amino groups of the growing peptide chains) was achieved using diisopropylcarbodiimide and N-hydroxybenzotriazole (1:1:1) in dimethylformamide (DMF), followed by washing with DMF, isopropanol, and dichloromethane. Coupling reactions were monitored using the Kaiser test (Kaiser et al., 1970). The Fmoc group on each N-terminal amino acid of the growing peptide chain was deprotected with 20% piperidine in DMF prior to each subsequent coupling reaction. Upon completion of the synthesis, the peptides were treated with acetic anhydride and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (2:1 molar ratio) with a 10 fold molar excess of acetic anhydride to the free amino groups on the growing peptide chain to acetylate the N-terminus. Peptides were cleaved from the resin and amino acid side chain protecting groups were removed using 90% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), 5% water, 2.5% ethanedithol, and 2.5% triisopropylsilane, leaving a peptide with a Nα-acetylated N-terminus and a Cα-amidated C-terminus.

Disulfide Bond Formation

A disulfide bond was formed through the N-terminal Cys residue in the C-G-G sequence engineered into each peptide by air oxidation, resulting in a disulfide-bridged two-stranded monomer (Zhou et al., 1992a; Wagschal et al., 1999b). Peptide solutions of 5mg/mL in 100mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.3, were allowed to stir (unsealed) overnight at 4°C. The oxidized, disulfide-bridged peptides were verified by analytical reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatograhy (RP-HPLC) and Electrospray Ionization (ESI) - Time of Flight (TOF) - Mass Spectrometry (MS) (see below).

Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

Peptides were purified using an Agilent 1100 Series liquid chromatograph (Little Falls, DE) with a Zorbax 300SB-C8 column (250 × 9.6 mm I.D., 5μm particle size, 300Å pore size) from Agilent Technologies (Little Falls, DE) and a linear AB gradient. Eluent A was aqueous 0.2% TFA and eluent B was 0.2% TFA in acetonitrile (Chen et al., 2006; Mills et al., 2006). The gradient initially proceeded from 0-30%B over 15 minutes (2%B per minute) but was followed by a shallower gradient from 30%-55%B over 166 minutes (0.15%B per minute). Fractions were collected and screened by analytical RP-HPLC (Zorbax 300 SB C8 column, 150 × 2.1 mm I.D., 5μm particle size, 300Å pore size) (Agilent Technologies, Little Falls, DE) using a gradient rate of 1%B per minute from the starting conditions of 100% eluent A (aqueous 0.2% TFA) and ESI-TOF-MS. Fractions containing pure material were pooled and lyophilized.

Mass Spectrometry

Peptides were diluted 1:20 to 1:50 in MS solution (49.5% methanol, 49.5% water, 1% acetic acid) and directly injected (10μL - 20μL) for analysis by ESI-TOF-MS (Applied Biosystems Bio-Spec Workstation, Foster City, CA). The resulting charged species (+1, +2, +3, etc) were monitored for confirmation of the appropriate mass.

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

Peptide solutions were analyzed by CD spectroscopy using a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Inc., Easton, MD) with the Jasco DP-500/PS2 system software (version 1.33a) running on a Dell Dimension 4100, Pentium III. A Lauda model RMS circulating water bath (LAUDA-Brinkman, Delran, NJ) was used to maintain temperature control of the optical cell. Results are expressed as mean molar ellipticity [θ] (deg·cm2·dmol-1) as calculated from the equation

where θobs is the observed ellipticity in millidegrees, MRW is the mean residue weight of the peptide (peptide molecular weight/number of residues), l is the optical path length of the cell in centimeters, and c is the peptide concentration in mg/ml. Peptide concentrations were determined by amino acid analysis using a Beckman 6300 amino acid analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Stock solutions of disulfide-bridged peptides of 2mg/mL were prepared in benign CD buffer (100mM KCl, 50mM PO4, pH 7). The stocks were used to prepare peptide dilutions of 0.2 mg/ml in either benign CD buffer or CD buffer with 50% trifluoroethanol (TFE) for analyses in a 1 mm pathlength cell. Variable wavelength measurements of peptide solutions were scanned at 5°C from 190 nm to 255 nm, in 0.5 nm increments, and a scan rate 50 nm per minute. The average of 6 scans was reported. Variable temperature measurements of peptides in benign CD buffer were scanned at 222 nm from 5°C to 90°C in 0.5°C increments with a scan rate of 60°C/hour. The fraction of folded peptide present over this temperature range was calculated according to the equation

where [θ]obs is the observed molar ellipticity at a given temperature, [θ]u is the molar ellipticity of the fully unfolded species, and [θ]f is the molar ellipticity of the fully folded species. The temperature midpoint (Tm) corresponds to an ff value of 0.5, or 50% folded peptide, and was determined from a plot of fraction folded versus temperature. Short coiled-coils are known to exhibit pre- and post-transitions that occur in a concentration-independent manner because of end-fraying and other molecular motion that does not lead to helix unfolding (Dragan and Privalov, 2002).

RP-HPLC Temperature Profiling

Temperature profiling was performed in the manner previously described (Lee et al., 2003b; Mant et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2005). Briefly, solutions of the native peptide, analog peptides, and a random coil control peptide (Ac-ELEKGGLEGEKGGKELEK-amide) were prepared in buffer A (aqueous 100mM NaClO4, 10mM NH4H2PO4, pH 7) at 1.7mg/ml. Analytical RP-HPLC runs were performed for each peptide solution using an Agilent 1100 series liquid chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Little Falls, DE, USA), a Phenomonex (Torrance, CA) Gemini C18 column (250 × 3 mm I.D., 5μm particle size, 110Å pore size), and a linear AB gradient of 0-100%B over 50 minutes (2%B per minute), where eluent A is an aqueous solution of 100mM NaClO4, 10mM NH4H2PO4, pH 7, and eluent B is solution of 50/50 (v/v) H2O/CH3CN containing 100mM NaClO4, 10mM NH4H2PO4, pH 7. The runs were performed at 26 different column temperatures, in 3°C increments, between 5°C - 80°C. Retention times were normalized to 5°C for all peptides according to the general equation

where tR5N is the retention time normalized to 5°C or the difference between a peptide retention time, tRT, at temperature T, and its retention time at 5°C, tR5. The normalized retention times were then used to calculate the association parameter (PA) for each peptide according to the equation

where tR5NP refers to the peptide of interest and tR5NC refers to a random coil control peptide. A large maximum PA value (PA,Max) indicates greater peptide self-association and higher stability. Accessible Surface Area and Coiled-Coil Radius Calculations. Miller et al., 1987, describes accessible surface area (ASA) values for both non-polar and polar side chains of all amino acids. These values are based on a residue X in a Gly-X-Gly tripeptide with an extended main chain conformation. For our purposes, only non-polar side chain ASA values were used to determine Theoretical ASA. Residues with polar side chain ASA values were not considered. For example, the documented side-chain ASA for a Leu residue is 137 Å2 × 2 (for each coiled-coil chain) = 274, the Theoretical ASA. Monomer and dimer ASA values were determined from areaimol calulations using the CCP4 suite of programs for protein crystallograpy (Acta Cryst. D50:760-763, 1994). For dimeric coiled-coil calculations, unmodified PDB files were used except for 1IC2 (tropomyosin 1-81), which contains two coiled-coils (chains A-D) in the asymmetric unit. In this case, chains C and D were deleted and a new PDB file was created containing chains A and B only. This file was used for residues considered in the tropomyosin sequence region 1-81. To determine monomer ASA values from areaimol calculations, modified pdb files were created by deleting the coordinates for either chain A or chain B and saving these as new pdb files. Separate areaimol calculations were performed for each modified pdb file and then summed to give Observed ASA values the consider both coiled-coil chains. All tabulated values for observed ASA are the sum of the values for the noted residue(s) in both chains A and B, either from two separate areaimol calulations (monomer) or from one areaimol calculation (dimer). Buried area was determined from the difference between the Theoretical ASA and Observed ASA.

Coiled-coil radius calculations were performed using the program TWISTER as described previously (Strelkov and Burkhard, 2002).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant RO1GM061855) and the John Stewart Chair in Peptide Chemistry to Robert S. Hodges. We would like to thank Sergie Strelkov for his generous assitance with the use of the TWISTER coiled-coil analysis program. We also thank Rui Zhao for assistance with the use of the areaimol program from the CCP4 suite of protein crystallographic tools.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acharya A, Rishi V, Vinson C. Stability of 100 homo and heterotypic coiled-coil a-a′ pairs for ten amino acids (A, L, I, V, N, K, S, T, E, and R). Biochemistry. 2006;45:11324–11332. doi: 10.1021/bi060822u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akey DL, Malashkevich VN, Kim PS. Buried polar residues in coiled-coil interfaces. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6352–6360. doi: 10.1021/bi002829w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JH, Kim K-H, Jun G, Greenfield NJ, Dominguez R, Volkmann N, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE, Cohen C. Deciphering the design of the tropomyosin molecule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:8496–8501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131219198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JH, Zhou Z, Reshetnikova L, Robinson H, Yammani RD, Tobacman LS, Cohen C. Structure of the mid-region of tropomyosin: Bending and binding sites for actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:18878–18883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509269102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosshard HR, Marti DN, Jelesarov I. Protein stabilization by salt bridges: concepts, experimental approaches and clarification of some misunderstandings. J. Mol. Recognit. 2004;17:1–16. doi: 10.1002/jmr.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhard P, Meier M, Lustig A. Design of a minimal protein oligomerization domain by a structural approach. Protein Sci. 2000;9:2294–2301. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.12.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhard P, Stetefeld J, Strelkov SV. Coiled-coils: a highly versatile protein folding motif. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:82–88. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01898-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhard P, Ivaninskii S, Lustig A. Improving coiled-coil stability by optimizing ionic interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;318:901–910. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-H, Yang JT, Chau KH. Determination of the helix and β form of proteins in aqueous solution by circular dichroism. Biochemistry. 1974;13:3350–3359. doi: 10.1021/bi00713a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Mant CT, Hodges RS. Preparative reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography collection efficiency for an antimicrobial peptide on columns of varying diameters (1 mm to 9.4 mm I.D.). J. Chromatogr. A. 2006;1140:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Mant CT, Farmer SW, Hancock REW, Vasil ML, Hodges RS. Rational design of α-helical antimicrobial peptides with enhanced activities and specificity/therapeutic index. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:12316–12329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413406200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou PY, Fasman GD. Conformational parameters for amino acids in helical, α-sheet, and random coil regions calculated from proteins. Biochemistry. 1974;13:211–222. doi: 10.1021/bi00699a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 “The CCP4 Suite: Programs for Protein Crystallography”. Acta Cryst. 1994;D50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway JF, Parry DA. Structural features in the heptad substructure and longer range repeats of two-stranded α-fibrous proteins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1990;12:328–334. doi: 10.1016/0141-8130(90)90023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper T, Woody R. The effect of conformation on the CD of interacting helices: a theoretical study of tropomyosin. Biopolymers. 1990;30:657–676. doi: 10.1002/bip.360300703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick FHC. The packing of α-helices: simple coiled-coils. Acta Crystallogr. 1953;6:689–697. [Google Scholar]

- Dragan and Privalov Unfolding of a leucine zipper is not a simple two-state transition. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;321:891–908. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00699-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson BW, Merrifield RB. Solid-phase peptide synthesis. In: Neurath H, Hill RL, editors. The Proteins. Third Edition II. Academic Press, Inc.; New York, NY: 1976. pp. 255–527. [Google Scholar]

- Fields GB, Noble RL. Solid-phase peptide synthesis utilizing 9-fluoroenylmethoxycarbonyl amino acids. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1990;35:161–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1990.tb00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank S, Lustig A, Schulthess T, Engel J, Kammerer RA. A distinct seven residue trigger sequence is indispensable for proper coiled-coil formation of the human macrophage scavenger receptor oligomerization domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:11672–11677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoryan G, Keating AE. Structural specificity in coiled-coil interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbury PB, Zhang T, Kim PS, Alber T. A switch between two, three, and four-stranded coiled-coils in GCN4 leucine zipper mutants. Science. 1993;262:1401–1407. doi: 10.1126/science.8248779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges RS. De novo design of α-helical proteins: Basic research to medical applications. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1996;74:133–154. doi: 10.1139/o96-015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges RS. Unzipping the secrets of coiled-coils. Curr. Biol. 1992;2:122–124. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(92)90241-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges RS, Sodek J, Smillie LB, Jurasek L. Tropomyosin: amino acid sequence and coiled-coil structure. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 1972;37:299–310. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges RS, Amrit KS, Chong PCS, St.-Pierre SA, Reid RE. Synthetic model for two-stranded α-helical coiled-coils. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:1214–1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges RS, Mills J, McReynolds S, Kirwan JP, Tripet B, Osguthorpe David. Identification of a unique stability control region that controls protein stability of tropomyosin: a two-stranded α-helical coiled-coil. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;392:747–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyghues-Despointes BM, Scholtz JM, Baldwin RL. Helical peptides with three pairs of Asp-Arg and Glu-Arg residues in different orientations and spacings. Protein Sci. 1993;2:80–85. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser E, Colescott RL, Bossinger CD, Cook PI. Color test for detection of free terminal amino groups in the solid-phase synthesis of peptides. Anal. Biochem. 1970;34:595–598. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammerer T. Schulthess, Landwehr R, Lustig A, Engel J, Aebi U, Steinmetz MO. An autonomous folding unit mediates the assembly of two-stranded coiled coils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:13419–13424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn WD, Monera OD, Kay CM, Hodges RS. The effects of interhelical electrostatic repulsions between glutamic acid residues in controlling the dimerization and stability of two-stranded α-helical coiled-coils. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:25495–25506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn WD, Mant CT, Hodges RS. α-Helical protein assembly motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 1997a;272:2583–2586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn WD, Kay CM, Hodges RS. Salt effects on protein stability: two-stranded α-helical coiled-coils containing inter- or intrahelical ion pairs. J. Mol. Biol. 1997b;267:1039–1052. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn WD, Kay CM, Hodges RS. Orientation, positional, additivity, and oligomerization-state effects of interhelical ion pairs in α-helical coiled-coils. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;283:993–1012. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn WD, Hodges RS. De novo design of α-helical coiled-coils and bundles: models for the development of protein-design principles. Trends in Biotechnology. 1998;16:379–389. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs JM, Mant CT, Hodges RS. Determination of intrinsic hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity of amino acid side-chains in peptides in the absence of nearest neighbor or conformational effects. Biopolymers (Peptide Science) 2006;84:283–297. doi: 10.1002/bip.20417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krylov D, Mikhailenko I, Vinson C. A thermodynamic scale for leucine zipper stability and dimerization specificity: e and g interhelical interactions. EMBO J. 1994;13:2849–2861. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06579.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krylov D, Barchi J, Vinson C. Inter-helical interactions in the leucine zipper coiled-coil dimer: pH and salt dependence of coupling energy between charged amino acids. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;279:959–972. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok SC, Hodges RS. Clustering of large hydrophobes in the hydrophobic core of two-stranded α-helical coiled-coils controls protein folding and stability. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:35248–35254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok SC, Hodges RS. Stabilizing and Destabilizing Clusters in the Hydrophobic Core of Long Two-stranded α-Helical Coiled-Coils. J. Biol. Chem. 2004a;279:21576–21588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401074200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok SC, Hodges RS. Effect of chain length on coiled-coil stability: decreasing stability with increasing chain length. Biopolymers (Peptide Science) 2004b;76:378–390. doi: 10.1002/bip.20141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne P, Sönnichsen FD, Kay CM, Hodges RS. Interhelical salt bridges, coiled-coil stability, and specificity of dimerization. Science. 1996;271:1136–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau SYM, Taneja AK, Hodges RS. Synthesis of a model protein of defined secondary and quaternary structure: effect of chain length on the stabilization and formation of two-stranded α-helical coiled-coils. J. Biol. Chem. 1984a;259:13253–13261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau SYM, Taneja AK, Hodges RS. Effects of high-performance liquid chromatographic solvents and hydrophobic matrices on the secondary and quanternary structure of a model protein: Reversed-phase and size exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A. 1984b;317:129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Lee DL, Lavigne P, Hodges RS. Are trigger sequences essential in the folding of two-stranded α-helical coiled-coils? J. Mol. Biol. 2001;306:539–553. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DL, Ivaninskii S, Burkhard P, Hodges RS. Unique stabilizing interactions identified in the two-stranded α-helical coiled-coils: Crystal structure of a cortexillin I/GCN4 hybrid coiled-coil peptide. Protein Sci. 2003a;12:1395–1405. doi: 10.1110/ps.0241403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DL, Mant CT, Hodges RS. A novel method to measure self-association of small amphipathic molecules. J. Biol. Chem. 2003b;278:22918–22927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301777200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumb KJ, Kim PS. Measurement of interhelical electrostatic interactions in the GCN4 leucine zipper. Science. 1995;268:436–439. doi: 10.1126/science.7716550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumb KJ, Kim PS. Interhelical salt bridges, coiled-coil stability, and specificity of dimerization - Response. Science. 1996;271:1137–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas AN, Gruber M. The structure of α-helical coiled-coils. Adv. Prot. Chem. 2005;70:37–78. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J. Predicting coiled-coils from protein sequences. Science. 1991;252:1162–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mant CT, Tripet B, Hodges RS. Temperature profiling of polypeptides in reversed-phase liquid chromatography II. Monitoring of folding and stability of two-stranded α-helical coiled-coils. J. Chromatogr. A. 2003;1009:45–59. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(03)00919-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matousek WM, Ciani B, Fitch CA, Garcia-Moreno E. B, Kammerer RA, Alexandrescu AT. Electrostatic contributions to the stability of the GCN4 leucine zipper structure. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;374:206–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason JM, Arndt KM. Coiled-coil domains: stability, specificity, and biological implications. Chembiochem. 2004;5:170–176. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason JM, Muller KM, Arndt KM. Considerations in the design and optimization of coiled-coil structures. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007;352:35–70. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-187-8:35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan AD, Stewart M. Tropomyosin coiled-coil interactions: evidence for an unstaggered structure. J. Mol. Biol. 1975;98:293–304. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier M, Lustig A, Aebi U, Burkhard P. Removing an interhelical salt bridge abolishes coiled-coil formation in a de novo designed peptide. J. Struct. Biol. 2002;137:65–72. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2002.4467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier M, Burkhard P. Statistical analysis of intrahelical ionic interactions in α-helices and coiled-coils. J. Struct. Biol. 2006;155:116–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills JB, Mant CT, Hodges RS. One-step purification of a recombinant protein from a whole cell extract by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A. 2006;1133:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]