Abstract

Objective

The Dietary Intake Monitoring Application (DIMA) is an electronic dietary self-monitor developed for use on a personal digital assistant (PDA). This paper describes how computer, information, numerical, and visual literacy were considered in development of DIMA.

Methods

An iterative, participatory design approach was used. Forty individuals receiving hemodialysis at an urban inner-city facility, primarily middle-aged and African American, were recruited.

Results

Computer literacy was considered by assessing abilities to complete traditional/nontraditional PDA tasks. Information literacy was enhanced by including a Universal-Product-Code (UPC) scanner, picture icons for food with no UPC code, voice recorder, and culturally sensitive food icons. Numerical literacy was enhanced by designing DIMA to compute real-time totals that allowed individuals to see their consumption relative to their dietary prescription. Visual literacy was considered by designing the graphical interface to convey intake data over a 24-hour period that could be accurately interpreted by patients. Pictorial icons for feedback graphs used objects understood by patients.

Practice Implications

Preliminary data indicate the application is extremely helpful for individuals as they self-monitor their intake. If desired, DIMA could also be used for dietary counseling.

Keywords: informatics, self-management, hemodialysis, health literacy

1.Introduction

Health literacy, defined as “the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” [1], is a growing concern for much of the United States population. Nearly half of U.S. adults, or about 90 million men and women, have trouble understanding and acting on health information [2–3].

Inadequate health literacy is a particular problem for chronically ill persons. Disease self-management, described as the daily decisions and activities individuals perform to live with and control illness [4], requires both knowledge of what to do and the ability to carry out the medical and lifestyle regimen [5]. To successfully self-manage chronic illness, individuals must know how to monitor disease, manage symptoms, carry out daily medical regimens, and interpret results of home-monitoring therapies. Poor health literacy hampers these important tasks. For example, inadequate health literacy has been associated with less asthma-related knowledge and improper use of metered-dose technique in asthma [6], poorer decisions by patients using home peritoneal dialysis [7], fewer diabetes self-management behaviors [8–9], and the inability of heart failure patients to read and understand standard medication labels [10].

Although poor health literacy is associated with problems in self-managing chronic illness [6], it is not associated with an individual’s ability to learn or retain information [11]. When written educational materials are developed for use by individuals with poor literacy skills, they should be readable and understandable by the intended audience; provide associations between new information and what is already known; involve participants in design; provide participants with active learning opportunities; and use visuals to emphasize the main message, reduce the amount of reading in text, provide visual cues, and be motivating [12].

Our research group works with patients who receive hemodialysis and are prescribed a complex dietary prescription. The purpose of this paper is to describe how we considered health literacy in the design of the Dietary Intake Monitoring Application (DIMA).

1.1. Dietary prescription for adults receiving hemodialysis

Individuals receiving hemodialysis are asked to self-manage a complex and restrictive diet and fluid regimen to reduce the accumulation of electrolytes and waste products between treatments. Compared with average American intake of 3.8 grams sodium, 2.8 grams potassium, and 1.4 grams phosphorus [13], a typical prescription for individuals receiving hemodialysis is 2 grams sodium, 2 grams potassium, and 1 gram phosphorus [14], although this may vary depending on individual factors. Individuals are also asked to limit fluid intake to 1000 milliliters per day [14] to prevent an excessive accumulation of body fluid between treatments. In addition to these limitations, current guidelines recommend a protein intake of 1.2 grams per kilogram body weight per day and a dietary energy intake of 35 or 30 to 35 kilocalories per kilogram body weight per day for, respectively, individuals under and over 60 years of age [15]. The difficulty individuals encounter when implementing this complex diet is reflected by estimates of dietary adherence ranging from 33% to 98% [16–20] and of fluid adherence from 7% to 59% [18, 21–23]. Adherence varies because, for example, individuals have different dietary habits, knowledge, geographical climates, living conditions, and personal reactions to prescribed limitations.

1.2 Barriers to self-management

Hemodialysis patients must have certain skills to comply with the complex diet described here, such as the ability to read, interpret, and calculate daily intake on an ongoing basis. Although patients are taught about portion sizes, they must be able to adjust food intake behavior [24]. Even if patients can read labels, they must be able to convert between different units of measure (e.g., milliliters to ounces) or add amounts over the course of a given day, abilities not to be assumed in the target population [25]. Various strategies are suggested to assist patients in limiting fluid intake on a daily basis, such as measuring daily allotted fluids into a pitcher and only taking liquids from that pitcher, but this limits a patient’s drink choice and social activities [26].

Another problem is that food labels do not typically provide all information needed for self-monitoring; for example, phosphorus and potassium are often omitted. Usually patients are simply instructed to limit or avoid foods with high amounts of potassium (e.g., bananas), phosphorus (e.g., milk products), and sodium (e.g., ham). Avoiding or even limiting certain food items is not realistic for patients because many foods are culturally integrated into diets or individuals simply have a strong preference for particular foods [27]. We lack tools, however, that would assist these individuals in making informed food choices.

1.3. Paper and electronic self monitoring

Self-monitoring, that is, recognizing the occurrence of a behavior and systematically recording the observation [28], has traditionally been done using paper diaries. The purpose of self-monitoring food and fluid intake is to increase awareness of consumption. Self-monitoring food intake is one of the most effective non-invasive techniques used in the treatment of obesity [29]. Estimates of actual compliance with completing paper diaries, however, range from 11% to 14% [30–31]. Self-monitoring can be individually accomplished using an electronic device such as a PDA. PDAs have been used to report symptoms in a variety of health contexts [32–34], including to track equipment-generated values such as blood glucose levels in diabetes [35] and to assess situational cues associated with smoking [36–37]. Furthermore, studies have found actual compliance rates with completing electronic diaries to range from 94 to 95%, much higher than for paper diaries [30–31], suggesting that electronic self-monitoring is easier, and patients often prefer this method [38].

When electronically self-monitoring diet, individuals are able to enter and track what they consume and how often they eat. Individuals receiving hemodialysis do not demonstrate impaired cognitive function [39–40] that would interfere with use of electronic devices, and such self-monitoring has shown initial promise for effectively self-managing their dietary and fluid prescription [41–43]. However, these previous studies used commercial products that had some limitations. For example, patients had difficulty using the standard interface widgets – the scrolling bar was too small for them to touch with the stylus and pushing the PDA down button was not intuitive for novice users. In addition, the applications required patients to traverse through many screens and asked for specific values that required memory and high numeracy skills. Finally, everything is in written form, including portion size. Patients often did not understand how to read these values and the concept of subtracting what they consumed from the dietary prescription was confusing to them [43].

The overall goal of our project was to create DIMA to provide dialysis patients with the ability to track their fluid and nutritional consumption by either scanning a UPC on a food item or by selecting an appropriate food icon on a graphical user interface. Developmental details are reported elsewhere [44–45]. The purpose of this paper is to describe how we used an iterative, participatory approach to design an appropriate interface for low literacy users.

2. Methods

2.1 Design

Iterative design is a well recognized, cyclic process in which designers create a prototype of a system, test the prototype with users, analyze the user study findings, modify the prototype based on results, and retest the prototype until all stakeholders are satisfied with it. Stakeholders included not only the dialysis patients, but also our multidisciplinary team. Participatory design is also a well recognized process that attempts to get the target population involved as much as possible in the iterative-design process [46].

All of the developmental studies were in situ – conducted in the dialysis unit or in patients’ everyday lives. Some of our studies were designed based on tasks because we wanted to evaluate how target users would fare trying to complete a specific task using the prototype interface. All of the studies employed a think-aloud protocol and participants were asked to verbalize what they were thinking while completing tasks. For example, when a participant was asked to input what they ate for breakfast and looked at Figure 1, they may say, “I’m not sure where to begin. Well, I had some coffee and that image [pointing to nutritional supplements] is just Boost. I guess I would push this image here [pointing to fluids]. Yep – there it is!”

Figure 1.

Picture Icons for Foods

Dialysis patients were actively involved in this project during user study sessions when we would confirm our analysis of previous findings with the target population. For example, after one prototyping study [27], we showed participants in our next study the top two preferred and readable interfaces. We asked which interfaces they preferred and asked them to complete tasks with each interface to identify which ones were understandable. We also encouraged participants to modify or create their own paper-based interfaces to express their preferences. We verified our findings with unit renal dietitians and nurses by showing them the interfaces and identifying which were preferred by the target population. We recorded the dietitians’ and nurses’ comments and discussed them at our research team meetings to determine how the interfaces should be modified.

2.2 Procedures

The user studies followed a typical, higher-level design approach in which user needs were identified. Based on user needs, the research team brainstormed appropriate technology and input devices and evaluated them through a task-based, think-aloud protocol with dialysis patients [47]. Once an appropriate device was identified, paper pictures, or low fidelity prototypes, of what the interface could look like [48] were generated. Such prototypes provide a quick, inexpensive way to evaluate interface designs before investing the time and effort in implementing a computer version of the interface. Subjects evaluated the low fidelity prototypes and based on their feedback, a high fidelity prototype was created and evaluated in two user studies: (1) a study to verify that they could utilize the system to track intake and (2) a study in which subjects used the application during two week-long periods; a research assistant met with participants every 2–4 days to discuss their remote usage log files, usability issues, and opinions of self management with an electronic device [49–50]. Changes to the prototype were made based on feedback from participants.

3. Results

Sensitivity to health literacy is likely to improve clinical outcomes [51] and we developed DIMA for adults receiving hemodialysis to successfully self-manage dietary intake regardless of health literacy levels. We considered the following literacy skills as outlined by the National Network of Libraries of Medicine [52] when designing the application: (a) computer literacy or the ability to operate a computer, (b) information literacy or the ability to obtain and apply relevant written information, (c) numerical or computational literacy or the ability to calculate or reason numerically, and (d) visual literacy or the ability to understand graphs or other visual information. These four health literacy components and how they were considered as design decisions were made about DIMA are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Health Literacy Components Integrated into DIMA

Components of Health Literacy Integrated into DIMA

| Health Literacy Component | DIMA |

|---|---|

| Computer literacy | PDA with large icons |

| Information literacy | UPC scanner |

| Picture icons | |

| Voice recorder | |

| Culturally sensitive food icons | |

| Numerical literacy | Computes real-time totals for 6 main categories |

| Visual literacy | Graphical interface |

| Graph background changes color when individuals have nearly consumed the prescribed intake of each dietary element. | |

| Pictorial labels |

3.1. Sample

Following approval by the university Institutional Review Board, we iteratively designed DIMA over the course of user studies. We recruited participants who attended an inner-city urban dialysis center and were (a) over 21 years of age, (b) able to make their own food or go out and purchase food, (c) willing to meet with researchers during dialysis sessions for the study, (d) willing to carry the PDA and scanner with them and input food items they consumed. We conducted user studies during dialysis sessions because participants were only available during that time. More information about development is reported elsewhere [53].

Mean age of participants was 52 years (SD 17.5), 85% were African American, and 55% were female. Though literacy levels were not formally measured during development, qualitative data provided some information about the literacy levels of the participants. For example, one participant described how he drew pictures of what he ate for the dietitian.

3.2. Computer literacy

Although prior empirical studies have suggested that the health of an individual is not a barrier to technology use [54–56], an initial concern of our team was the acceptability of a computer-based program to a chronically ill population. We were also concerned about the patients’ physical ability to use a computer because adults receiving hemodialysis often have bone disease [57] that may limit manual dexterity, and half of the national patient population has a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus [58], which may affect visual acuity. These concerns were addressed by conducting a series of user studies prior to developing DIMA. We began by determining whether, relative to younger persons, older healthy adults could use a PDA because we hypothesized that dialysis patients might have acuity and dexterity problems similar to those of many older adults. We found that, although older participants took relatively longer to physically manipulate the PDA, they were able to complete tasks [59].

Our assessment then turned to the target population to determine if they could complete traditional and nontraditional PDA tasks. We compared the dialysis participants’ success rates with our results from younger and older adults. We found dialysis patients were able to press buttons, record messages, and scan bar codes just as well as our healthy adults. Similar to the older adults, however, the dialysis patients preferred 19 millimeter icons. Overall, the dialysis participants found all of the PDA tasks easy to complete [60].

Participants were asked if they used a computer and, if so, how often. In addition, they were asked what type of applications they used on the computer and what, if anything, they accessed on the Internet. Overall, those who used computers typically only used them for playing games and surfing the Internet. Participants were also asked about mobile phone usage and the types of mobile phones they used. The few participants who owned a mobile phone typically had pay-as-you-go plans.

3.3. Information literacy

An individual must be able to read to be information-literate and to self-manage a diet and fluid prescription. Current clinical practices require hemodialysis patients to be able to read lists of foods to avoid and/or to be able to read and interpret food labels. No empirical data about reading levels for this patient population were found; however, the National Assessment of Adult Literacy [61] indicates that 40 to 44 million adults across the United States have low literacy skills. Poor reading skills are particularly prevalent in minority populations and those who are socio-economically disadvantaged [62]. Currently available dietary software programs using the USDA food database require the ability to read and spell when searching the database - skills some of our patients would not have.

The Nutrition Data System for Research [63] was used to specify serving size and nutritional information for DIMA. Dietitians with experience working with dialysis patients reviewed past food diaries from all patients in their caseload. These dietitians also drew from extensive experience to ensure that the DIMA database contained food icons that were culturally relevant to our population, suggesting additions such as chitterlings, ham hocks, pig’s feet, tofu, jicama, couscous, Ramen noodles, and hot sauce. The PDA selected for DIMA included a voice recorder. If individuals could not find a food item in the database, they were asked to voice-record the item so we could add it to our database.

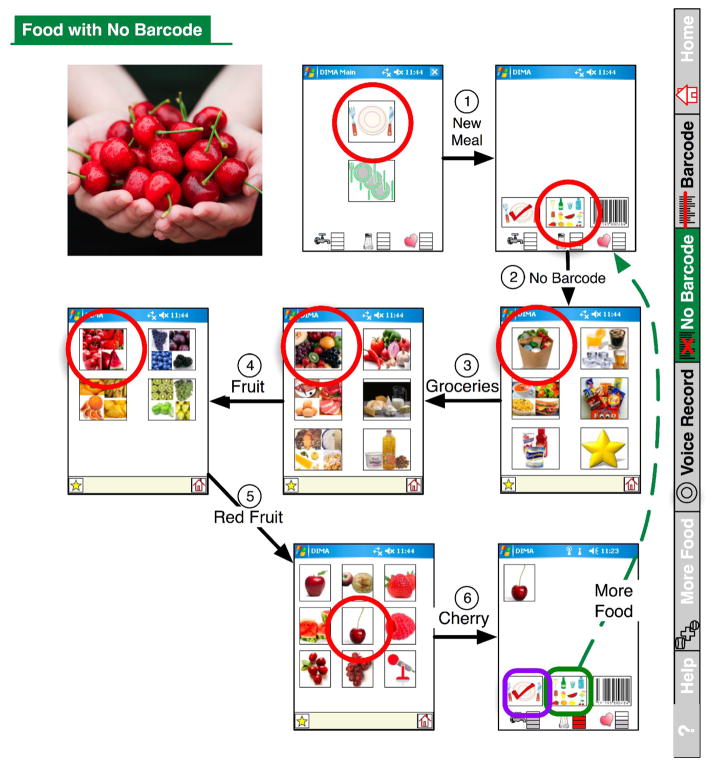

Technology can provide a bridge for individuals with low health literacy skills to overcome the barrier of poor reading skills and successfully self-manage their diets. We did this in two major ways. First, we incorporated a UPC scanner to provide patients with the ability to scan any food item containing a UPC code directly into the PDA. Second, we included picture icons for foods with no UPC code (Figure 1) [64]. To make the application user-friendly, we determined how patients cognitively organized food. We decided that the navigation should be circular, bringing the user back to the same page every time a food is entered. For example, when using this feature patients will see a series of screens displaying picture icons. The first screen shows six pictures that refer to groceries, fluids, prepared foods, snacks, nutritional supplements, and favorites. If, for example, they want to enter cherries, they would select the grocery icon and be taken to the next screen, which would display an additional six categories – fruits, vegetables, meats, breads, dairy, and oils. To reach the cherries, they would select the fruit icon. The next screen depicts red, blue, yellow, and green fruits, and an individual would select red for cherries. The next screen displays a picture of all red fruits and an individual would select cherries to add to his or her intake. This cherry example is shown in Figure 2 - an excerpt from the user manual we developed. Although participants had to traverse many screens, they reported that the number of steps wasn’t a problem if the choice of next step was obvious.

Figure 2.

Interface Screen Shots for Selecting Food Items

3.4. Numerical literacy

Self-managing diet and fluid also depends upon health numeracy skills, defined as the “ability to read and understand numbers and perform basic mathematical computations” [65]. These skills are beyond those of some patients; our past research found that approximately one third of hemodialysis patients had difficulty performing simple calculations [25]. A major feature of DIMA is that it can compute real-time totals, allowing patients to see their intake relative to their dietary prescription for the day for six main categories – sodium, potassium, phosphorus, fluid, protein, and calories – without having to perform any calculations themselves. For example, when a patient selects a food item such as cherries, the program looks up the nutrients associated with a single serving of cherries and updates the daily consumption of each nutrient appropriately. The total amount consumed is then displayed in both graphical and textual form, in comparison to their total daily limits (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Graphical Display for Daily Intake.

NOTE: In this figure, fluid, phosphorus, and potassium intake are well below the dietary prescription. Daily sodium consumption is close to the dietary prescription and the background appears in red. The individual has also consumed enough calories today but has only consumed half of the recommended amount of protein.

3.5. Visual literacy

We assessed patients’ abilities to interpret graphic information about intake to help us select a graphical interface to convey intake data that would be interpreted accurately by patients. The renal diet includes four elements to be restricted and two elements to be consumed in adequate quantity, so we wanted the application to display these two types of information differently. Although many different types of graphical visualizations were tested, the patients could most accurately interpret the display that closely represented what they had used in the past. For example, participants preferred a water consumption icon that looked like a large glass of water. The participants all had received a large, liter-size container when beginning dialysis treatment to help them visualize how much they were allowed to consume. Thus, the digital fluid indicator was informed by the physical artifact participants were already using. As shown in Figure 3, the graphical information for sodium, potassium, phosphorus, and fluid is presented visually using bars in 25% increments. These four graphs were created such that, when individuals have consumed almost the prescribed limit, the background changes to red.

For nutrients that have a minimum to be consumed each day (i.e., calories and protein), a pie graph is used such that a smiling face will be completed when individuals consume 100% of each of these nutrients. The graph will fill in incrementally throughout a 24-hour period to indicate consumption. For example, as shown in Figure 3, this individual has consumed 100% of the minimal requirements for calories and 50% of the protein needed. The intake data for all six components are reset every 24 hours.

Much discussion occurred within the research team and with renal dietitians about how to label the feedback graphs to be understandable to patients and yet avoid the use of words. We selected a salt shaker for sodium, a heart for potassium, a bone for phosphorus, a water spigot for fluid, a steak for protein, and an individual running for calories (Figure 3) to be consistent with educational materials presented in the clinical setting. All participants were able to correctly label the images during later user studies.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

Individuals receiving hemodialysis are prescribed a complex and restrictive diet that requires many cognitive and behavioral skills for successful self-management. We designed DIMA using an iterative participatory design approach that considered computer literacy, information literacy, numerical literacy, and visual literacy skills. The DIMA is an electronic dietary self monitor designed to facilitate self-management and improve clinical outcomes.

We chose to use few words in the application. However, we have learned that some participants would like words associated with food icons to confirm their selection; we will add words in the future. We expected that the UPC scanner would decrease input time and would assist individuals with low literacy skills. However, the scanner frequently fell out of the PDA, frustrating patients. In addition, patients have difficulty using the scanner easily.

When developing written patient educational materials for low literacy individuals, people with adequate literacy skills are satisfied and don’t mind using them [12]. We do not know, however, whether patients with adequate literacy will be satisfied with a technological application developed for individuals with low literacy skills. Will patients with adequate literacy become too frustrated if they have to traverse too many screens? Future research will seek answers to this question.

4.2. Future Research

A pilot study is currently underway to obtain preliminary data about feasibility, usability, and efficacy of DIMA. Anecdotal data collected during this study indicate that the application is helpful and usable. In addition, participants are choosing to use icons more often than the UPC scanner. Several participants have asked to keep the PDA after completing the self-monitoring portion of our pilot study so they could continue self-monitoring after study participation.

A large randomized controlled trial is being planned. Important components that will need to be considered include analysis of cost and patient clinical outcomes. In addition, technological advances progress very quickly over time. Therefore, if DIMA is found to be feasible, usable, and efficacious, in the future we may need to consider the use of other devices that are now available to make integration into daily living more practical for those with chronic illness.

4.3. Limitations

There were several limitations of our developmental work. First, we did not formally measure literacy levels and collected limited demographic data during development. We are measuring literacy levels during the current pilot study to determine whether it is an important moderating variable. Second, the sample size was small during development of DIMA. The sample size, however, was typical for development of software applications. Third, feasibility and usability testing for DIMA has not been completed.

4.4 Practice Implications

If usable and efficacious, the application will provide a powerful tool for patients to use when making daily decisions about diet and fluid intake despite varying health literacy skills. It also has the potential to be a useful tool for patients when they are seeking dietary counseling from health care providers.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant made available by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (R21 EB007083). We would like to thank the members of the Intervention Faculty Research Group and Dr. Phyllis Dexter for their invaluable comments and suggestions during manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Janet L. Welch, School of Nursing, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Katie A. Siek, Department of Computer Science, University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA

Kay H. Connelly, Computer Science Department, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA

Kim S. Astroth, Mennonite College of Nursing, Illinois State University, Normal, IL, USA

M. Sue McManus, School of Nursing, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Linda Scott, School of Nursing, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Seongkum Heo, School of Nursing, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Michael A Kraus, Medical School and Clarian Health Partners, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and improving health. 2. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006–483). US Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moser DK, Watkins JF. Conceptualizing self-care in heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing . 2008;23:205–218. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000305097.09710.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2007;31(suppl 1):S19–S26. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazmararian JA, Williams MW, Peel J, Baker DW. Health literacy and patient knowledge of chronic disease. Patient Educ Couns . 2003;51:267–275. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kleinpeter MA. Health literacy affects peritoneal dialysis performance and outcomes. Advances in Peritoneal Dialysis . 2003;19:115–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavanaugh K, Hulzinga MM, Wallston KA, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Davis D, Gregory RP, Fuchs L, Malone R, Cherrington A, Pignone M, DeWalt DA, Elasy TA, Rothman RL. Association of numeracy and diabetes control. Annals of Internal Medicine . 2008;148:737–746. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thackeray R, Merrill RM, Meiger BL. Disparities in diabetes management practice between racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Diabetes Educator . 2004;30:665–675. doi: 10.1177/014572170403000418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hope CJ, Wu J, Tu W, Young J, Murray MD. Association of medication adherence, knowledge, and skills with emergency department visits by adults 50 years or older with congestive heart failure. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2004;61:2043–2049. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.19.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paasche-Orlow MK, Riekert KA, Bilderback A, Chanmugam A, Hill P, Rand CS, Brancati FL, Krishnan JA. Tailored education may reduce health literacy disparities in asthma self-management. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine . 2005;172:980–986. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1291OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching patients with low literacy skills. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.U. S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Nutrient intakes from food: Mean amounts consumed per individual, one day, 2005–2005. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/12355000/pdf/0506/Table_1_NIF_05.pdf.

- 14.Fouque D. Nutritional requirements in maintenance hemodialysis. Advances in Renal Replacement Therapy . 2003;10:183–193. doi: 10.1053/j.arrt.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for nutrition in chronic renal failure. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2000;35(Suppl 2):S11–S92. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2000.v35.aajkd03517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bame SI, Petersen N, Wray NP. Variation in hemodialysis patient compliance according to demographic characteristics. Social Science & Medicine . 1993;37:1035–43. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90438-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown J, Fitzpatrick R. Factors influencing compliance with dietary restrictions in dialysis patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research . 1988;32:191–6. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(88)90054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cummings KM, Becker MH, Kirscht JP, Levin NW. Psychosocial factors affecting adherence to medical regiments in a group of hemodialysis patients. Medical Care . 1982;20:567–580. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198206000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonsalves-Ebrahim L, Sterin G, Gulledge AD, Gipson WT, Rodgers DA. Noncompliance in younger adults on hemodialysis. Psychosomatics . 1987;28:34–41. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3182(87)72577-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmicker R, Baumbach A. Dietary compliance in hemodialysis patients. Contributions to Nephrology . 1990;81:115–123. doi: 10.1159/000418744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Betts DK, Crotty GD. Response to illness and compliance of long-term hemodialysis patients. American Nephrology Nurses’ Association Journal . 1988;15:96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Welch JL. Fluid management beliefs by stage of fluid adherence. Research in Nursing & Health . 2001;24:105–112. doi: 10.1002/nur.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welch JL, Perkins SM, Evans JD, Bajpai S. Differences in perceptions by stage of fluid adherence. Journal of Renal Nutrition . 2003;13:275–281. doi: 10.1016/s1051-2276(03)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ueland O, Cardello AV, Merrill EP, Lesher LL. Effect of portion size information on food intake. Journal of the American Dietetic Association . 2009;109:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans JD, Wagner CD, Welch JL. Cognitive status in hemodialysis patients as a function of fluid adherence. Renal Failure . 2004;26:575–581. doi: 10.1081/jdi-200031721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welch JL, Davis J. Self-care strategies to reduce fluid intake and control thirst in hemodialysis patients. Nephrology Nursing Journal . 2000;27:393–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siek KA, Connelly KH, Rogers Y. Pride and prejudice: learning how chronically ill people think about food; Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2006. pp. 947–950. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kopp J. Self-monitoring: a literature review of research and practice. Social Work Research & Abstracts. 1988 Winter;:8–20. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker RC, Kirschenbaum DS. Self-monitoring may be necessary for successful weight control. Behavior Therapy . 1993;24:377–394. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stone AA, Shiffman S, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, Hufford MR. Patient non-compliance with paper diaries. British Medical Journal . 2002;324:1193–1194. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7347.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stone AA, Shiffman S, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, Hufford MR. Patient compliance with paper and electronic diaries. Controlled Clinical Trials . 2003;24:182–99. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(02)00320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newman MG, Kenardy J, Herman S, Taylor CB. Comparison of palmtop-computer-assisted brief cognitive-behavioral treatment to cognitive-behavioral treatment for panic disorder. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology . 1997;65:178–83. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Affleck G, Tennen H, Urrows S, Higgins P, Abeles M, Hall C, Karoly P, Newton C. Fibromyalgia and women’s pursuit of personal goals: a daily process analysis. Health Psychology . 1998;17:40–47. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broers S, Van Vliet KP, Everaerd W, Le Cessie S, Radder JK. Modest contribution of psychosocial variables to hypoglycaemic awareness in Type 1 diabetes. Journal of Psychosomatic Research . 2002;52:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clarke WL, Cox DJ, Gonder-Frederick LA, Julian D, Schlundt D, Polonsky W. The relationship between nonroutine use of insulin, food, and exercise and the occurrence of hypoglycemia in adults with IDDM and varying degrees of hypoglycemic awareness and metabolic control. Diabetes Educator . 1997;23:55–8. doi: 10.1177/014572179702300107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Paty JA, Engberg J, Gwaltney CJ, Liu KS, Gnys M, Hickcox M, Paton SM. Dynamic effects of self-efficacy on smoking lapse and relapse. Health Psychology . 2000;19:315–323. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH, Liu KS, Paty JA, Kassel JD, Hickcox M, Gnys M. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: an analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology . 2002;111:531–545. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dale O, Hagen KB. Despite technical problems personal digital assistants outperform pen and paper when collecting patient diary data. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology . 2007;60:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Najafi M. Evaluation of Conner’s continuous performance test in hemodialysis patients. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases & Transplantation. 2008;19:210–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pliskin NH, Yurk HM, Ho LT, Umans JG. Neurocognitive function in chronic hemodialysis patients. Kidney International. 1996;49:1435–1440. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dowell SA, Welch JL. Use of electronic self monitoring for food and fluid intake: a pilot study. Nephrology Nursing Journal . 2006;33:271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sevick MA, Piraino B, Sereika S, Starrett T, Bender C, Bernardini J, Stark S, Burke LE. A preliminary study of PDA-based dietary self-monitoring in hemodialysis patients. Journal of Renal Nutrition . 2005;15:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jrn.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Welch JL, Dowell S, Calley C. Feasibility of using a personal digital assistant to self-monitor diet and fluid intake: a pilot study. Nephrology Nursing Journal . 2007;33:43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Connelly KH, Rogers Y, Siek KA, Jones J, Kraus MA, Perkins SM, Trevino LL, Welch JL. In: Salvendy G, editor. Designing a PDA interface for dialysis patients to monitor diet in their everyday life; Proceedings Human Computer Interaction (HCI) International; Lawrence Erlbaum Associations; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Connelly KH, Faber AM, Rogers Y, Siek KA, Toscos T. Mobile applications that empower people to monitor their personal health. e & i Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik. 2006;123:124–128. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharp H, Rogers Y, Preece J. Interaction design: Beyond human computer interaction. Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moor KA, Connelly KH, Rogers Y. A comparative study of elderly, younger, and chronically ill novice PDA users Technical Report TR 595. Indiana University; 2004. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rettig M. Prototyping for tiny fingers. Commun ACM. 1994 Apr;37(4):21–27. DOI= http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/175276.175288.

- 49.Siek KA, Connelly KH, Rogers Y, Rohwer P, Lambert D, Welch JL. When do we eat? An evaluation of food items input into an electronic food monitoring application. In: Aarts E, Kohno R, Lukowicz P, Trainini JC, editors. PHC 2006: Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare, ICST, IEEE digital library; 2006; 2006. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siek KA, Connelly KH, Chaudry B, Lambert D, Welch JL. Evaluation of two mobile nutrition tracking application for chronically ill populations with low literacy skills. In: Olla P, Tan J, editors. Mobile Health Solutions for Biomedical Applications. Hershey, PA: Medical Information Science Reference; 2009. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Social Science & Medicine . 2008;67:2072–2078. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Network of Libraries of Medicine. Health literacy. 2008 Retrieved October 20, 2008, from http://nnlm.gov/outreach/consumer/hlthlit.html.

- 53.Siek K, Connelly K. Lessons learned conducting user studies in a dialysis ward. Reality Testing: HCI Challenges in Non-Traditional Environments Workshop; 2006. http://www.cs.indiana.edu/surg/CHI2006/WorkshopSchedule.html. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brennan PF, Moore SM, Smyth KA. Alzheimer’s disease caregivers’ uses of a computer network. Western Journal of Nursing Research . 1992;14:662–673. doi: 10.1177/019394599201400508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brennan PF, Overholt JL, Casper G, Calvitti A. Medinfo. Pt 2. Vol. 8. 1995. Elders using a computer network: Profile of a champion; p. 1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Boberg E, Owens BH, Sherbeck C, Wise M, Pingree S, Hawkins RP. Empowering patients using computer based health support systems. Quality in Health Care . 1999;8:49–56. doi: 10.1136/qshc.8.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Bone Metabolism and Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2003;42(suppl 3):S1–S202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.United States Renal Data System. USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report: atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2008. Available at www.usrds.org. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siek KA, Rogers Y, Connelly KH. Fat finger worries: How older and younger users physically interact with PDAs. In: Constable MF, Paterno F, editors. INTERACT 2005 LNCS. Vol. 3585. International Federation for Information Processing; pp. 267–280. Available at www.springerlink.com/content/aphl5wkd04yk3hmq/ [Google Scholar]

- 60.Connelly KH, Rogers Y, Siek KA, Jones J, Kraus MA, Perkins SM, Trevino LL, Welch JL. In: Salvendy G, editor. Designing a PDA interface for dialysis patients to monitor diet in their everyday life; Proceedings Human Computer Interaction (HCI) International; Lawrence Erlbaum Associations; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 61.National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) [Accessed February 4, 2009];National Center for Education Statistics. Available at http://nces.ed.gov/nall/kf_demographics.asp.

- 62.Health Resources and Services Administration. [Accessed February 4, 2009.];Health literacy. Available at http://www.gov/healthliteracy/

- 63.Nutrition Data System for Research software version 2007. Nutrition Coordinating Center (NCC), University of Minnesota; Minneapolis, MN: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grisedale S, Graves M, Grünsteidl A. Designing a graphical user interface for healthcare workers in rural India. In: Pemberton S, editor. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Atlanta, Georgia, United States. March 22 – 27, 1997; New York, NY: ACM; pp. 471–478. CHI ‘97. DOI= http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/258549.258869. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ancker JS, Kaufman D. Rethinking health numeracy: a multidisciplinary literature review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association . 2007;14:713–721. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]