Abstract

The geometric complexity and variability of the human cerebral cortex has long intrigued the scientific community. As a result, quantitative description of cortical folding patterns and the understanding of underlying folding mechanisms have emerged as important research goals. This paper presents a computational 3-dimensional geometric model of cerebral cortex folding initialized by MRI data of a human fetal brain and deformed under the governance of a partial differential equation modeling cortical growth. By applying different simulation parameters, our model is able to generate folding convolutions and shape dynamics of the cerebral cortex. The simulations of this 3D geometric model provide computational experimental support to the following hypotheses: 1) Mechanical constraints of the skull regulate the cortical folding process. 2) The cortical folding pattern is dependent on the global cell growth rate of the whole cortex. 3) The cortical folding pattern is dependent on relative rates of cell growth in different cortical areas. 4) The cortical folding pattern is dependent on the initial geometry of the cortex.

1. Introduction

Anatomy is an excellent window into the mystery of the human brain because it can be thought of as an intermediate phenotype that is partly determined by the genome and that partly determines the mind and behavior. The anatomy of the human cerebral cortex itself is extremely variable across individuals in terms of its size, shape and structure pattern (Talairach and Tournoux, 1988; Van Essen et al., 1998; Fischl et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2004). An essential characteristic of the cerebral cortex geometry is its folding, which has intrigued the scientific community for years (Le Gros Clark, 1945; Richman, et al., 1975; Rakic, 1988; Welker 1990; Van Essen, 1997). Recently, quantitative description of folding pattern (Zilles et al., 1988; Yu, 2007a; Toro et al., 2008) and understanding of the underlying mechanisms (Van Essen, 1997; Raghavan et al., 1997; Toro and Burnod, 2005; Geng et al., 2007; Geng et al., 2009) have emerged as important research goals.

Human brains grow from similarly shaped neuronal tubes (Brown et al., 2002). Aside from the development of primary cortical convolutions, such as the calcarine and central sulci, the major cortical folding variations of the human cerebral cortex emerge after approximately 8 months of fetal development (Brown et al., 2002). Many developmental processes are involved in cortical folding, including neuronal proliferation, migration and differentiation, glial cell proliferation, programmed cell death, axonal development and synaptogenesis. How these developmental processes interact with each other and dynamically accomplish cortical gyrification or folding is still largely unknown (Van Essen, 1997; Monuki and Walsh, 2001; O'Leary and Nakagawa, 2002; Grove and Fukuchi-Shimogori, 2003; Sur and Rubenstein, 2005; Rakic, 2006).

In the neuroscience community, several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the gyrification or folding of the cerebral cortex (e.g., Le Gros Clark, 1945; Connolly, 1950; Malamud and Hirano, 1974; Rakic, 1988; Ono et al., 1990; Welker 1990; Van Essen, 1997). Mechanical constraint was the first major factor considered when investigating the determinants of cortical folding (Le Gros Clark, 1945). This hypothesis claims that since the cortical area is almost three times larger than the cranial area, the cortex had to convolve to fit into a relatively small cranial volume. However, later experiments have shown that the limitation imposed by cranial volume is not the only determinant factor of cortical folding (Barron, 1950; Goldman and Galkin, 1978; Rakic, 1988; Dehay et al., 1996; Haydar et al., 1999; Chenn and Walsh, 2002; Kingsbury et al., 2003). Other mechanical factors could also be involved in distributing the folding pattern to its neighboring regions (Richman et al. 1975; Todd, 1982; Connolly, 1950). For example, the corpus callosum, which forms early in fetal development, influences the folding pattern of the cingulate gyrus (Le Gros Clark, 1945; Malamud and Hirano, 1974; Ono et al., 1990).

In the protomap hypothesis (Rakic, 1988), the cortical primordium is patterned as it is generated. Intrinsic areal differences, as specified by molecular determinants, are first set up in the ventricular zone. Emerging neurons then migrate out of the ventricular zone to form the cortical plate, based on protomap designations. As such, the areal difference, especially the cytoarchitectonic difference that causes regional mechanical property variation is considered the determinant factor in gyrification. In human cerebral cortex, many different cytoarchitectonic regions are separated by sulcal fundi such as the central sulcus, which separates the primary somatosensory cortex and the primary motor cortex, and the lunate sulcus, which separates the striate and extrastriate cortex (Connolly, 1950; Welker 1990). However, areal differentiation only approximately corresponds to sulcal fundi (Rademacher et al., 2001). The protocortex hypothesis, on the other hand, suggests that the cortical primordium is homogeneous as it is generated and subsequently patterned by cues originating from innervating thalamic neurons (O'Leary, 1989). According to this theory, the gyrification process highly interacts with the areal differentiation process, meaning that it might partly determine the resulting areal differentiation.

Axongenesis, which may cause areal differentiation (O'Leary, 1989; Walsh and Cepko, 1988; Walsh and Cepko, 1992), is also a determining factor in gyral pattern development. The axogenesis hypothesis posits that cortical and sensory connections drive the convolution of the cerebral cortex. It seems, then, that the “development of cortical areas involves a rich array of signals, with considerable interplay between mechanisms intrinsic to cortical progenitors and neurons and mechanisms extrinsic to the cortex, including those requiring neural activity” (Sur and Rubenstein, 2005).

Other hypotheses of cortical folding mechanisms include differential growth of cortical layers (Richman, et al., 1975), modulation of tangential neuron migration by chemical activation and inhibition (Cartwright, 2002), different rates of cell division in particular loci (Brown et al., 2002), relative degrees of tethering of different areas (Brown et al., 2002), and the genesis of glial cells, oligodendrocytes and astrocytes (Vaccarino et al., 2007). Other reviews of existing hypotheses of cortical folding mechanisms can be found in the literature, e.g., in Hilgetag and Barbas, 2005, Toro and Burnod, 2005, and Geng et al., 2009.

Current evidence shows that human cerebral cortex morphogenesis entails a complex interaction of physical forces that influence the growth and displacement of different brain tissues (Grove and Fukuchi-Shimogori, 2003; Sur and Rubenstein, 2005; Rakic, 2006). Cortical shape dynamics would largely reflect factors that dictate the connectivity, geometry and topology of the underlying neural circuitry and anatomy. It seems that computational modeling would potentially provide a unique and effective strategy for investigating how genetic, molecular, cellular, organic, and environmental factors influence cortical shape dynamics, as well as how aberrances of these factors could result in disease or psychopathology. We further believe computational modeling can provide important insights into the complexities of cortical folding by providing a testable platform to investigate mechanisms driving the folding processes as well as how these mechanisms interact in different stages of cortical neurodevelopment. Given the availability of cortical folding models, their computational simulations can be conducted to test whether specific cortical shape dynamics, which occur during development of particular cerebral cortex regions, can be replicated using plausible assumptions about forces and boundary conditions in the different cortical folding mechanisms. Collectively, these simulations would be able to test and evaluate different hypotheses of cortical gyrification or folding, e.g., the hypothesis of tension-based morphogenesis and compact wiring (Van Essen, 1997).

In the literature, there have been several attempts to develop computational models to understand the cortical folding process. For example, in Raghavan et al., 1997, the authors proposed a continuum mechanics-based model of growth to synthesize cortical shapes by using physical laws. At each instant of the growth process, the shape of the object corresponds to a minimum of the energy function and the growth is taken to be a quasistatic process; the model was used to simulate the growth of a 2-dimensional brain cortex. Toro and Burnod (2005), proposed a computational morphogenetic model to study the fundamental mechanisms of cortical folding. In this model, the 2-dimensional annular cortex and radial glial fibers were modeled by finite-elements, and cortical growth, which later developed to convolution, was modeled as the expansion of finite elements. More recently, Geng et al. (2009) proposed two 3-dimensional biomechanical models of cortical folding for the sheep brain. The first model used Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) data of the fetal sheep brain as a cue to model the tension forces that regulated cortical folding. The second model described tangential cortical growth using osmotic expansion of the tissue and used inhomogeneous white matter rigidity as a biomechanism for cortical folding. It was demonstrated that structural MRI and DTI data can be combined with a finite element modeling technique to generate biologically meaningful models of the cortical folding process (Geng et al., 2009).

Due to the complex neurobiological processes involved in cortical folding, computational modeling is quite challenging. Our strategy is to implement and test individual theories or hypotheses one by one and later integrate these different theories/hypotheses into a general framework in order to evaluate the interactions between different mechanisms. In this paper, a three dimensional morphogenetic model is proposed to study the mechanisms of human cortical gyrification. Since the human cerebral cortex can be conceptualized as a highly convoluted, thin shell (Van Essen and Maunsell, 1980; Xu et al., 1999; Fischl et al., 1999), a triangulated surface of the developing cortex is adopted as its representation. This geometric surface model is driven by the mechanical forces occurring in the growing brain in order to properly simulate the shape dynamics of the developing human cerebral cortex. Parametric surface models of the cortex are then initialized by fetal structural MRI data (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 2007) acquired across 22 to 36 week-old gestating fetuses. Deformation of the morphogenetic model occurs under the governance of partial differential equations. The mechanical forces and boundary conditions are similarly guided by MR imaging data. Advanced techniques for the prevention of self-intersection are employed in the larger deformations of the brain surface meshes. After applying the mechanical and growth properties on each triangular element, our time-varying system is solved by the Newmark scheme (Newmark, 1959). By applying different simulation parameters, our model is able to generate convolutions and simulate the shape dynamics of the cerebral cortex. The simulations of this proposed model provide computational experimental support to the following hypothesis: 1) Mechanical constraints of the skull influence the cortical folding process. 2) The cortical folding pattern is dependent on the global cell growth rate in the whole cortex. 3) The cortical folding pattern is dependent on relative rates of cell growth in different areas. 4) The cortical folding pattern is dependent on the initial geometry of the cortex.

2. Methods

The modeling of human brain cortical gyrification is a challenging endeavor. Firstly, due to the difficulty of imaging a developing fetal brain, the dynamic observation of human gyral development is limited. Secondly, soft tissue modeling for brain tissue is still an open problem (Mohamed et al., 2006) and so is the huge convolution developed from smooth brain tube. Because of the highly non-linear mechanical features of the convoluted thin shell, it is very challenging to apply the finite element method to model the 3D cortex (Mohamed et al., 2006). Instead, surface models are widely used in computer graphics to model soft thin shells such as clothes in real time (Baraff and Witkin, 1998; Grinspun et al., 2003), which has certain mechanical similarities to convoluted cortex. Hence, in this paper, surface modeling is used to represent the cerebral cortex, and development of more realistic volumetric model is left to our future work.

2.1 Materials and pre-processing

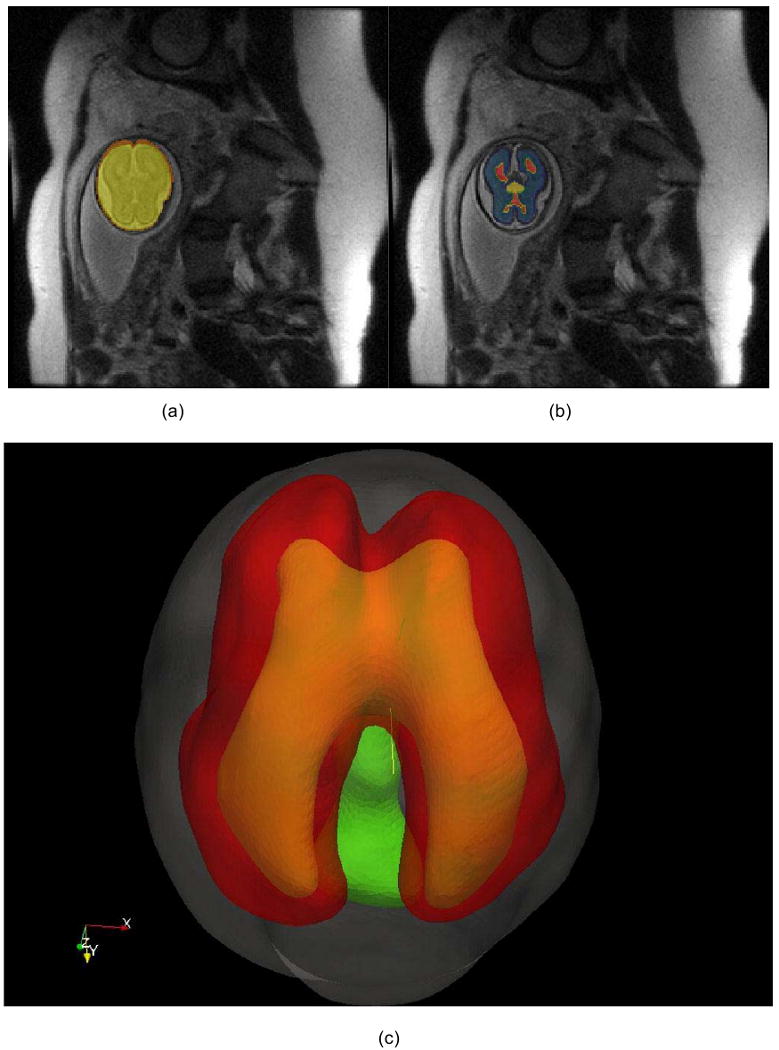

In-vivo T2 MRI data of 22 weeks gestation fetal brains (SE sequence TR=1329.88ms and TE=88.256ms; Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 2007) were used for the cortical surface reconstruction and folding model initialization. Fetal brain images were segmented by semi-automatic methods using ITK-SNAP (Yushkevich et al., 2006). Firstly, the fetal brains were brain extracted (Figure 1a). Secondly, the skull, cortical plate, white matter zones (including subplate and intermediate zones; Dubois et al., 2008), ventricle zones, basal ganglia, thalami, and cortex were identified/segmented (Figure 1b). Lastly, the inner surface of the skull and outer surface of the cortical plate were reconstructed using the methods in Liu et al., 2008 (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Fetal brain structure reconstruction. a) The fetal brain (yellow) is extracted from a torso MRI scan. b) The brain tissues are segmented, including cortical plate and white matter zone (blue), ventricular zone (red), and basal ganglia/thalami (yellow). c) The reconstructed surface of the skull (grey), cortex plate (red), ventricular zone (yellow) and basal ganglia/thalami (green).

2.2 Computational model

The proposed computational model of human cerebral cortex folding is composed of four key components: 1) A deformable model of the cortex: This model provides a geometric representation of the cortex that can be deformed into dynamic shapes via mechanical forces. The surface model is reconstructed using the data and methods described in Section 2.1. 2) Forces driving the folding: The mechanical driving forces are inferred from the cortical growth model and deform the cortical surface under partial differential equations. 3) Geometric constraints: Cortical growth is constrained by the geometrical relationship constraints of the brain structures, as well as boundary conditions. 4) Model solvers: The numerical solution to the partial differential equations guides the dynamic evolution of the geometric surface model of the cortex.

2.2.1 Deformable model

To model the mechanical properties of the developing cortex, the elasto-plasticity model was adopted in our methods. The elasticity property drives the surface model to restore it to its original shape while, at the same time, the plasticity property is forcing it to maintain the deformed shape permanently.

The developing cortex is represented as tens of thousands of triangle elements (21,136 in our experiments, as shown in Figure 1), each of which presents a small cortical region. During the development or growth of cortex, the elastic and plastic properties could be obtained from the deformed and reference coordinates of the triangle corner. The elastic force of each triangle element is defined along each edge of the triangle as:

| (1) |

where i and j are the triangle vertex indices, is the rest length of edge, and Kc is the elastic constant that determines the tangential elasticity of the cortex. As plasticity plays an important role in soft tissue deformation, in our model, the plasticity of the cortex is modeled as an adaptation of the reference configuration to the deformed configuration:

| (2) |

where τce is the time constant for the plasticity (Toro and Burnod, 2005) and is the current distance between vertices i and j.

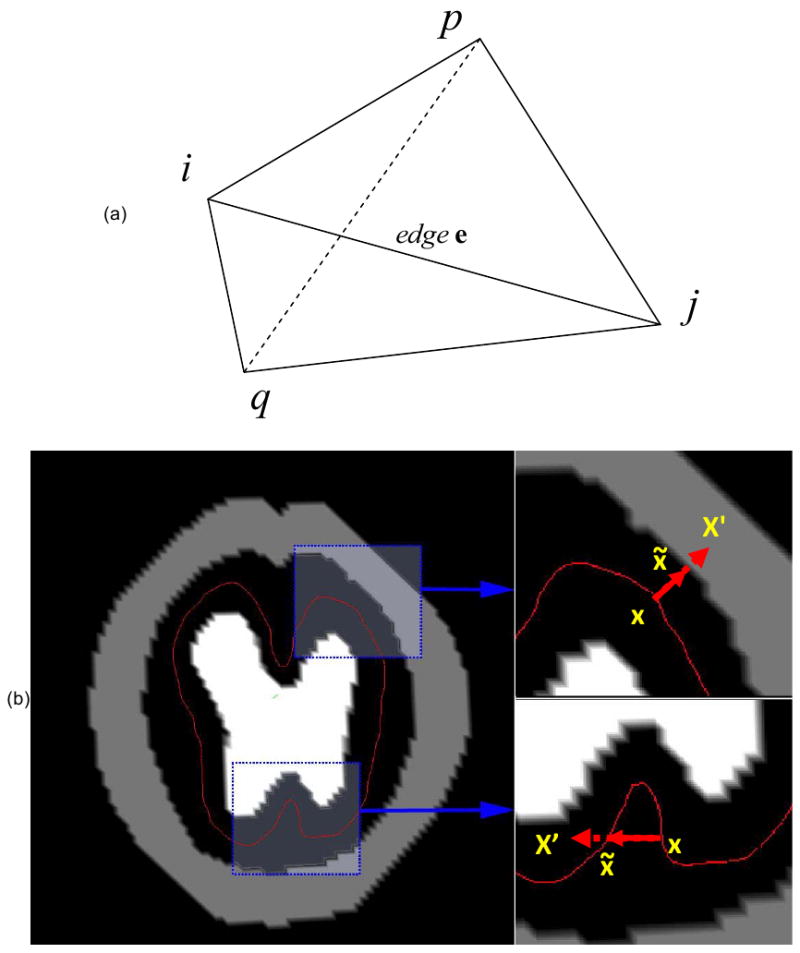

Since the cortex is modeled as a zero thickness surface, the rigidity of cortex is represented as a bending energy (Terzopoulos et al., 1987; Grinspun et al., 2003). In this paper, bending energy is defined as the squared difference of mean curvature of the deformed and reference surfaces (Grinspun et al., 2003). As computing mean curvature on the triangulated surface is computationally expensive, the simplified version of bending stress is defined on each edge of the surface triangle:

| (3) |

where i and j are the two vertices of edge e, p and q are the vertices that share the same triangle with edge e as illustrated in Figure 2(a), is the rest distance between vertices p and q and Kb is the elastic constant that determines the bending elasticity of the cortex. Furthermore, to a certain extent, Kb can be said to represent the thickness of cortex. The larger Kb is, the sharper the cortex can fold, indicating a thinner cortex. Also, the bending energy decreases with the plasticity of :

Figure 2.

(a) Illustration of bending energy. The change of the angle between 2 surfaces, Spji and Sqij, usually will cause the change of the distance between vertex p and q. (b) The two conditions that constrain cortical development. When cortical point x is trying to deform to the new position, x′, two conditions should be satisfied: 1) In the upper-right, x′ should not be inside other brain tissues; 2) in the bottom-right, x′ should not be cross the cortex itself. Otherwise, another position for this point that satisfies these two conditions, x̃, should be identified.

| (4) |

where τcb is the time constant for the plasticity of bending energy and is the current distance between vertices p and q.

2.2.2 Cortex growth model

Several biological processes are involved in the growth of the cerebral cortex, including neuron proliferation, programmed cell death, neuronal migration from the ventricular zone, dendritic projection, and so on (Brown et al., 2002). Evidence has shown that most or all neuronal migration is completed prior to the cortical folding (Childs et al., 2001; Lan et al., 2000) and that neuronal proliferation rarely happens inside the cortex. Thus, cortical neuronal populations may only increase for a short period of time following folding initiation and will later decrease due to apoptosis. Therefore, with the resulting limited variability of cortical neuronal populations, further cortical growth and gyrification should result from synapse development, neuron dendritic projection, and so on; mechanisms which can be considered to increase overall neuronal “size”.

Thus, by defining the “average size” of each neuron, the growth pattern of each small cortical element is defined as:

| (5) |

Where S̅c0(t) is the average size of neurons in the element, M(t) is the number of neurons in the element, and D(t) is the number of predefined apoptotic neurons. Since modeling and quantification of the average size of neurons at the cellular level is still an open problem in the computational neuroscience field, we adopt the classic logistic-growth function (Murray, 1993) to describe the growth of cortical tissues:

| (6) |

where m is known as the Malthusian parameter and k is the carrying capacity of the system (Murray, 1993). By changing the rest area of the triangular element, the growth of cortex will generate mechanical stress that partly drives the deformation of the cerebral cortex surface.

2.2.3 Constraints

Cortical development is limited by mechanical or boundary conditions such as cranial volume and self-collision (Le Gros Clark, 1945). To prevent the cortex from developing into the skull or other brain tissues, a volumetric constraint model is maintained during the simulated folding of the cortex. Voxels from the skull, basal ganglia/thalami and ventricular zone are extracted from the scanned 3D MRI image and grouped into a new image as a mask. Subsequently, the cortical growth model is limited to deformation outside of masked regions.

We have applied similar techniques (Liu et al., 2004) to prevent the self-intersection of deformed cortical surfaces. Specifically, the currently deformed cortex surface is rasterized to a volumetric model. When any vertex of the surface is being deformed to a new position x′, two conditions (Figure 2(b)) should be satisfied:

The new position of the vertex cannot be inside the developing skull or other brain tissue volume.

Deformation of the current vertex should not cause its neighboring triangles to intersect with rasterized surfaces in other neighborhoods.

If either of these two conditions are not satisfied, a new position that does satisfy them, x̃, is identified for the vertex. After determining the new position the vertex is deformed to the new position and its neighborhood is re-rasterized.

To simulate skull growth during the cortical folding process, the intracranial volume was dynamically modulated by the developing cortex. Similar to the volumetric constraint model, a constraint function, L(n), was defined on each voxel of the deformable space, where n is the iteration number. And when L(n) ≤ 0, the voxel is defined as a deformable voxel where the cortical surface can deform at the nth iteration; otherwise, it is defined as a constraint voxel. When n = 0, L(n) is the initial skull constraint that is acquired from MRI image segmentation. When n > 0, L(n) is interacting with the cortical folding process by:

| (7) |

where λL controls the growth speed of the skull and I(n) is also defined on each voxel. At iteration n, if any vertex or triangle on the cortex surface is trying to deform to this voxel, the value of I(n) is set to one, otherwise it is zero, meaning that cortical deformation into a skull voxel will cause an increase in intracranial volume.

2.2.4 Model Solver

Though the simulation of the cortical folding model is different in certain aspects from other physical models and simulations, the proposed system can still be formulated as a time-varying partial differential equation, which is commonly adopted in many deformable model approaches (Terzopoulos et al., 1987; Baraff and Witkin, 1998; Grinspun et al., 2003). Specifically, the dynamics of each cortical surface vertex can be simply formulated as ẍi = fi / mi, where ẍi is the acceleration of the vertex i, fi is the force that combines all forces affecting vertex i and mi is the mass of vertex i, which is usually defined as the sum of one thirds of the masses of all triangles around vertex i. By combining all equations on the cortical surface together, we have the discrete form of developing cerebral cortex as:

| (8) |

where x, ẋ and ẍ are the vertex's position, velocity, and acceleration, respectively, M is a 3n × 3n (n is the number of vertices) diagonal mass matrix on vertices where diag(M) = (m1, m1, m1, m2, m2, m2, …, mn, mn, mn) and F(x, ẍ) is the net force vector that combines all forces on cortical surface vertices.

The Newmark scheme (Newmark, 1959), which is widely used for solving ODE (ordinary differential equation) integration problems, was adopted in our implementation. Using the position and velocity given in the previous iteration, the deformed configuration at the next step can be estimated as:

| (9) |

| (10) |

where β ∈ [0, 0.5] and γ ∈ [0, 1] are adjustable parameters that are closely related to the accuracy and stability of the solver. Though implicit integrators can reduce the iteration number and minimize numerical damping (Grinspun et al., 2003), the amount of required computer memory is much higher than in explicit methods. In addition, since the number of vertices on the cortical surface should be set densely enough to represent the convoluted cortex, the explicit scheme was adopted in our implementation, that is β = 0 and γ = 0.

3. Results

3.1 Development of Convolutions and Skull Constraint

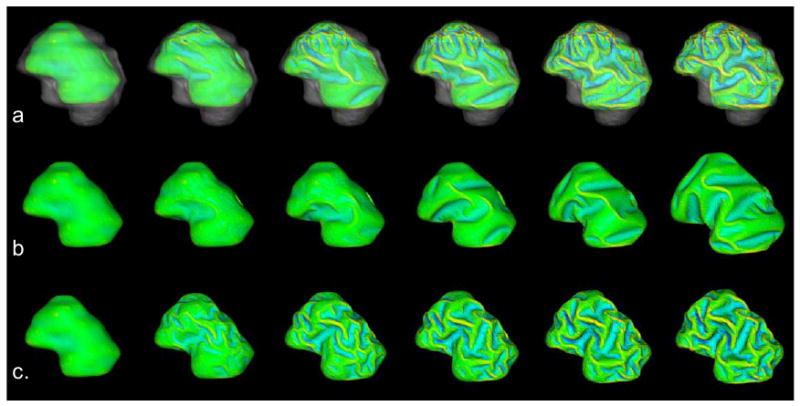

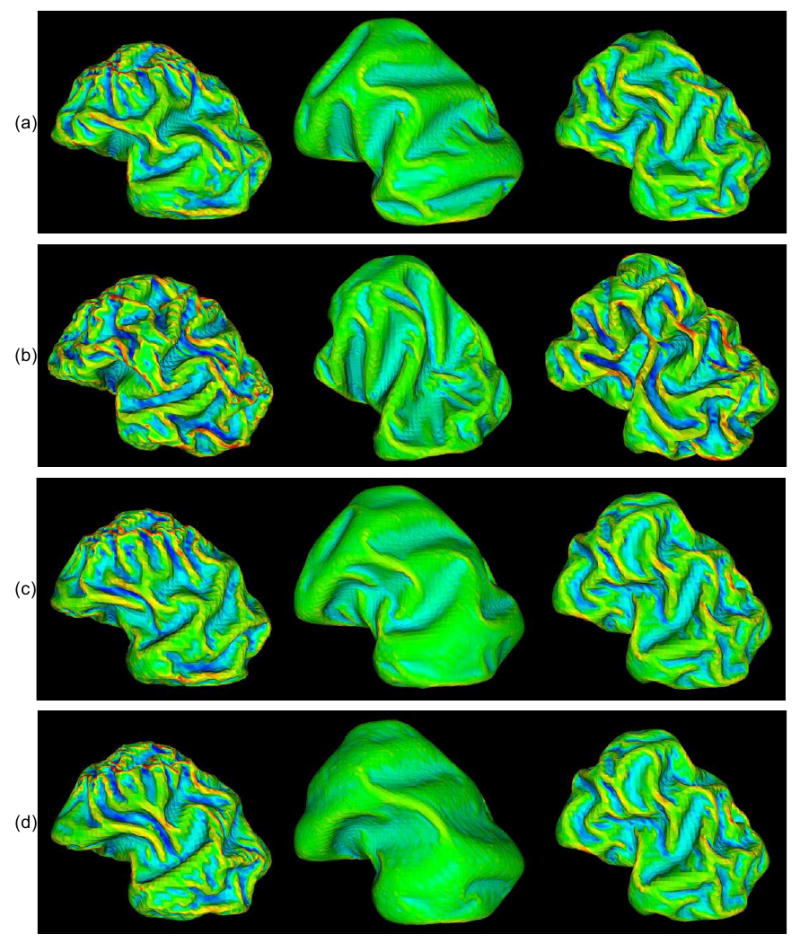

We simulated the computational models of cortical folding introduced in Section 2. The parameters in the deformable and growth models were the same in the simulations with and without skull constraints, and were set as: Kc = 1, τce = 1000, Kb = 5, τcb = 1000, m = 0.002, k = 3, Δt = 0.05, λL = 0.1. The folding development results of the 3-dimensional morphogenetic model are illustrated in Figure 3. Figures 3a, b and, c show snapshots of cortical development at iterations 0, 40, 80, 120, 160, and 200, with skull constraints set as static, none, or dynamic, respectively. Visual evaluation suggested that convolutions were generated during these simulations.

Figure 3.

Cortical development with and without skull constraints. The simulated results use sagittal views with anterior-posterior from left to right, and superior-inferior from top to bottom. (a), (b) and (c) show snapshots of cortical development at iteration numbers 0, 40, 80, 120, 160, and 200, with skull constraint settings as static, none and dynamic respectively. The parameters are set as: Kc = 1, τce = 1000, Kb = 5, τcb = 1000, m = 0.002, k = 3, λL =0.1. Mean curvature bar: -0.6  0.8

0.8

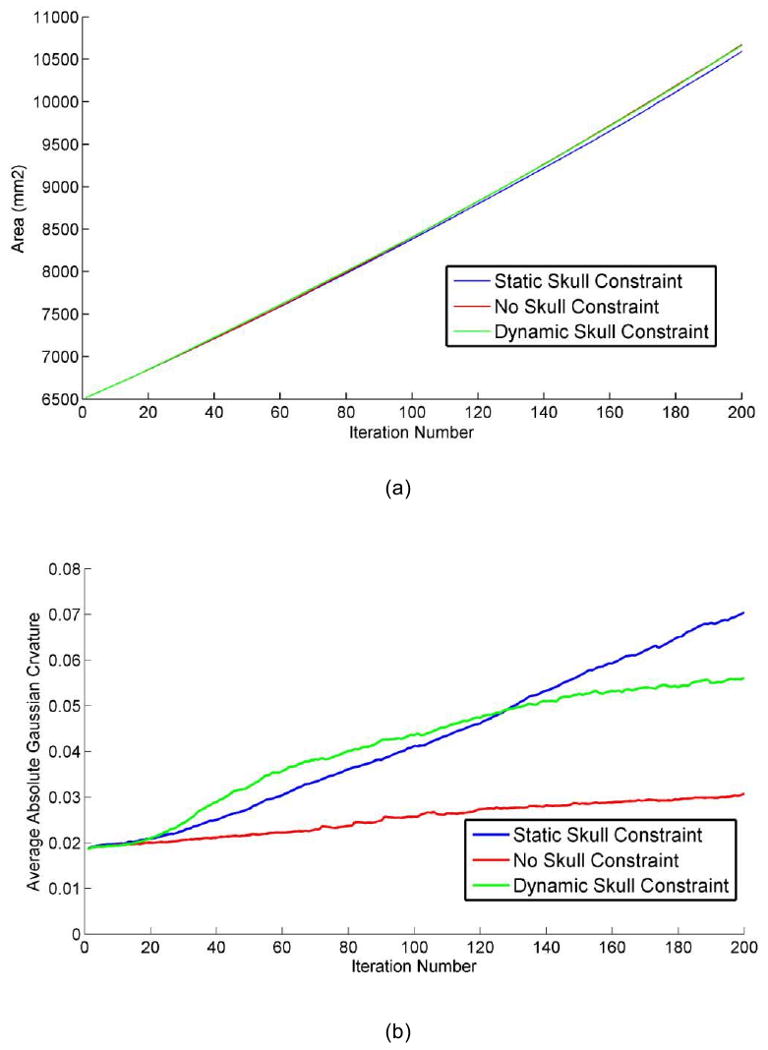

To quantitatively evaluate the produced convolutions, we used curvature as the measurement of cortical folding. The advantage in using this parameter is that it is easy to calculate and can characterize folding with reasonably good performance (Cachia et al., 2003). Also, we used the total surface area of the developing cortex to measure its growth rate. The dynamic variation of the total area of the cortex and the average absolute Gaussian curvature of the cortical surface are illustrated in Figure 4a and Figure 4b respectively. Figure 4a shows that the cortical surface area increases almost linearly with the simulation iterations, irrespective of what skull constraint is adopted. The results in Figure 4a indicate that the cortex increases its surface area and convolutes itself to reduce the fast growing internal tension with or without skull constraint. More importantly, as shown in Figure 4b, the increase in speed of average curvature in simulations with both static and dynamic skull constraints is much higher than the one without skull constraint, meaning that cortical development with a skull constraint is much more convoluted than without. This computational simulation result provides direct evidence to support the following hypothesis: mechanical constraints of the brain skull influence the cortical folding process.

Figure 4.

The differences of (a) total cortical area and (b) average absolute Gaussian curvature of the cortical surface during convolution development. The parameters are set as: Kc = 1, τce = 1000, Kb =5, τcb = 1000, m = 0.002, k = 3, λL = 0.1.

The results in Figures 3 and 4 also indicate that the skull constraint greatly influenced cortical growth patterns. Without the skull constraint, cortical expansion maintained a similar shape to the original cortical configuration during the first 40 iterations and small shape changes began to appear during iterations 40∼80. Subsequently, primary sulci rapidly developed during iterations 80∼160 and secondary sulci developed between major sulci shortly thereafter. In this non-skull constrained simulation, smaller tertiary gyri and sulci were not evidenced. Additionally, since most of the primary sulci developed were long but not deep, the average absolute Gaussian curvature slowly increased during the cortical development process.

The resulting cortical growth patterns with skull constrained simulations are strikingly different. That is, the primary and secondary sulci developed much earlier and faster, e.g., during iterations 40∼120. Also, smaller tertiary gyri and sulci developed during the last iterations (120∼200). Resulting sulci were also deeper, compared to those simulations without skull constraint. Thus, the average absolute Gaussian curvature increased faster as shown in Figure 4b. The strikingly different cortical growth patterns evidenced by Figures 3 and 4 further demonstrate that mechanical constraints of the skull significantly influence the cortical folding process.

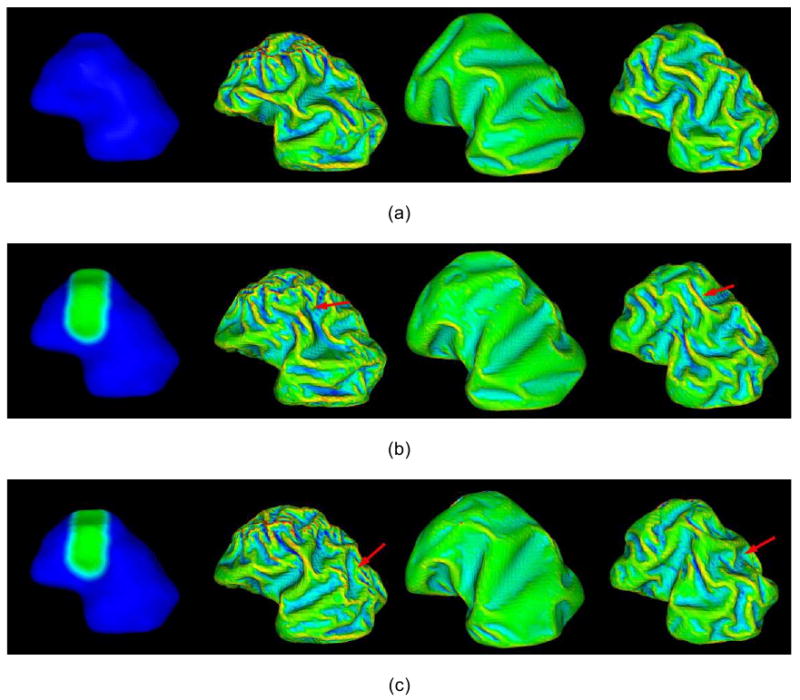

3.2 Effect of Global Cell Growth Rate on Folding

The experiments in this subsection investigated the effect of global cell growth rate on the cortical folding process. The Malthusian growth parameter, m, in Eq.(6) models the cell growth rate. According to Eq. (6) when m is increased from 0.002 (Figure 5(a)) to 0.004 (Figure 5(b)), the cortical growth speed is almost doubled. As a result, deeper sulci and smaller gyri were found in the simulated folding (Figure 5(b)). As shown in Table 1, the 3 dimensional GI (Gyrification Index, Zilles et al., 1988) of the static skull constraint simulation was significantly increased from 1.19 to 1.3, and increased from 1.18 to 1.32 in the dynamic skull constraint simulation. These simulation results provide experimental computational support for the following hypothesis: cortical folding patterns are dependent on global cortical cell growth rates. Lending further support to our model are statistical measurements of human fetal brain MRI data acquired during gestation weeks 23 to 26 (Batchelor et al., 2002). Batchelor and colleagues demonstrated that the average GI value increased from 1.13 to 1.37 during this period, similar to our simulation results in Table 1, demonstrating increases in GI values from 1.08 to 1.32.

Figure 5.

Results of the influence of skull constraint on convolution development. The skull constraints are set as static, none and dynamic from left to right columns. All simulated results are in the sagittal plane with anterior-posterior from left to right, and superior-inferior from top to bottom. (a) Parameters are set as those in Figure 4. (b) Malthusian parameter (m), which controls the growth rate, is changed to 0.004. (c) Kc is changed to 4. (d) Kc is changed to 4 and Kb is changed to 10. Mean curvature bar: -0.6  0.8

0.8

Table 1.

3D Gyrification Index (GI) results of the development of convolutions and skull constraint.

| Skull Constraint | (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | (e) | (f) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static | 1.191 | 1.300 | 1.194 | 1.192 | 1.183 | 1.163 |

| None | 1.111 | 1.174 | 1.104 | 1.084 | 1.111 | 1.112 |

| Dynamic | 1.180 | 1.324 | 1.178 | 1.165 | 1.170 | 1.174 |

Column (a) - (d) are the 3D gyrification index of the results in Figure 6 (a) - (d) respectively. Column (e) and (f) are the 3D gyrificaiton index of the results in Figure 7 (b) and (c) respectively.

In addition to m, the tangential elasticity (Kc) and bending elasticity (Kb) parameters can also indirectly influence the effect of the global cell growth rate. For example, a larger elastic constant, which determines the Kc and Kb of the cortex, could slow down gyral and sulcal development, especially that of secondary (Figure 5(c)) and tertiary (Figure 5(d)) sulci, and can also slightly decrease the GI value, as shown in Table 1.

Furthermore, as shown in the second column of Figure 5, it is interesting that the effect of global cell growth rate on the cortical folding process is much less significant in the simulations without skull constraint. For example, even though m is increased from 0.002 to 0.004, the increased GI value is not as significant as the results with the skull constraint shown in Table 1. This result further demonstrates that the skull constraint is an important modulator of cortical folding pattern formation. Figure 5 summarizes the different folding patterns mentioned above and obtained by changing the growth and mechanical parameters, with different skull constraints respectively. In the future, simulations using non-uniform cell growth rates should be considered and investigated.

3.3 Effect of Area Differentiation on Folding

It has been previously reported that the areal differentiation of the cerebral cortex is a strong factor influencing cortical folding patterns (Connolly, 1950; Welker 1990). To test this hypothesis we manually selected a cortical region of interest and decided to change its growth parameter, m (please refer to Eq. (6)), as illustrated in Figure 6. The green region on the left of Figure 6(b), which was expected to develop into the central sulcus, was manually labeled on the initial cortical surface. Then its m was set to half of the global m value. As shown in Figure 6(b), with the skull constraint in place the simulated folding pattern in the inhomogeneous parameter setting was notably different from the simulation with a homogeneous parameter setting. It should be noted that since the region of interest is along a superior-inferior direction, more sulci and/or gyri in this direction can be seen in the corresponding developed cortical area, as highlighted by the red arrows in Figure 6(b). This result demonstrates that cortical area differentiation has a significant influence on cortical folding development. However, with no skull constraint in place, a less appreciable difference is evident when comparing simulations with and without homogenous parameters. Again, this result demonstrates that skull constraint is an important modulator of cortical folding pattern development.

Figure 6.

Effect of area differentiation and initial cortical shape on the development and distribution of convolution. All the simulated results are in the sagittal plane with anterior-posterior from left to right, and superior-inferior from top to bottom. The first column is the initial cortical surface, and the results from second to fourth column are with skull constraints setting as static, none, and dynamic, respectively. All the parameters are set as those in Figure 4. (a) The original results without area differentiation and initial cortical shape change. (b) Area differentiation: the growth parameter (m) is set to be 0.001 in the green region and is set to be 0.002 in blue region. (c) Initial cortical change: the green region on the initial cortex is internally deformed about 2mm. Mean curvature bar: -0.6  0.8

0.8

3.4. Effect of Initial Geometry on Folding

It was hypothezied that initial cortical geometry would have a significant influence on cortical folding patterns (Brown et al., 2002). To examine the effect of initial cortical shape on convolution development and distribution, a small artificial deformation was applied to the originally reconstructed cortex surface as illustrated in Figure 6(c). The green region on the superior right cortex, which is the same region manually labeled in Section 3.3, is deformed around 2mm towards the ventricular zone. The cortical folding simulation results (Figure 6(c)) demonstrate that initial cortical geometry has a significant influence on the resulting cortical folding pattern. However, without a skull constraint the intial cortical geometry had a lesser impact. It is also apparent from the results in Figure 6(c) that local shape differences not only cause folding pattern variations near the locally deformed region, but also have global influences on cortical folding patterns across the cortex, as denoted by red arrows in Figure 6(c). These results demonstrate that local variation in folding shapes will propagate to the entire cortical surface via the Eq. (8), indicating that the cortical folding process is a globally oriented process and not only a localized procedure. Also, molecular and genetic mechanisms involved in the determination of initial geometry should be investigated in the future, e.g., in Striegel and Hurdal, 2009.

4. Discussion and conclusion

Our 4D simulation results have shown that 1) Mechanical constraints imposed by the skull significantly influence the cortical folding process; 2) the cortical folding pattern is dependent on the global cortical cell growth rate; 3) the cortical folding pattern is dependent on relative rates of cell growth in different regions; and 4) the cortical folding pattern is dependent on initial cortical geometry. However, our simulation results show that cortical folding pattern is sensitive to factors mentioned above, and they might not be the determinative factors that regulate cortical folding patterns. Previous studies have provided theoretical analysis (Le Gros Clark, 1945; Connolly, 1950; Malamud and Hirano, 1974; Rakic, 1988; Ono et al., 1990; Welker 1990; Van Essen, 1997; Brown et al., 2002) or computational experimental results in 2D space (e.g., Raghavan et al., 1997; Toro and Burnod, 2005) for the above mentioned results. However, we believe that the 3D representation and 4D simulation of the cortical folding process presented in this paper is important to fully understand the intrinsically 4D process of cortical folding.

In the experiments in Section 3, our simulations demonstrated that mechanical constraints imposed by the skull are important regulators of cortical folding. However, it should be noted that our simulations indicated that skull constraint is not necessarily the dominant or initializing mechanism. Previous experimental observation has also shown that it is difficult to conclude that skull restraint initiates the development of cortical folding (Barron, 1950). Our current model of neuronal growth also assumes isometric deformation. However, it should be noted that this isometric model is insufficient, as Hilgetag and Barbas, 2006, demonstrated that there are systematic variations in absolute thickness and cell number across the cortical landscape, e.g., the gyral columns contain significantly more neurons than sulcal columns. Currently, the growth parameter, m, for our simulations are either homogenous or set differently in manually selected regions. In future work we plan to infer or estimate growth parameters from MRI data of the developing brain by measuring cortical thickness or gray matter density (Fischl et al., 1999; Yu, et al., 2007b). Those cortical measurements will then be mapped to the simulation space via cortical surface registration algorithms (Yeo, 2008a) allowing us to investigate how multiple, locally intrinsic areal differentiations influence the cortical folding process.

At this stage, the computational cortical folding model in this paper is simplistic. The only driving force that deforms the geometric cortical surface model is the cortex neuron growth, as presented in Section 2.2.2. In the future, there are more hypotheses regarding cortex folding mechanisms yet to be modeled and simulated. For example, and as previously stated in the tension-based theory of morphogenesis (Van Essen, 1997), cortical patterns are considered to be the result of minimization of global tension energy along axons, dendrites, and neuroglia. In this model, the cortical and sensory connections are considered the driving forces behind the convolution of the cerebral cortex. Strong connections in outward folding regions and weak connections in inward regions have been found to support this hypothesis, especially in visual, auditory, and somato-sensory areas. Given the recent advancements in high-resolution Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI), it may be possible to measure how white matter fiber orientation in the fetal brain possibly influences the tension forces that may regulate folding (Geng et al., 2007; Geng et al., 2009). Also, the availability of a common and verifiable 3D/4D computational modeling framework will be very important for future investigations of the effects of genetic, molecular, cellular, organic, and environmental factors' influence on the folding of a normal cerebral cortex (Monuki and Walsh, 2001; O'Leary and Nakagawa, 2002; Grove and Fukuchi-Shimogori, 2003; Sur and Rubenstein, 2005; Rakic, 2006; Striegel and Hurdal, 2009), as well as future investigations into how these factors interact with each other. Our future work will extend the computational system to a more general framework that could easily plug-in new mechanical force models, implemented according to different biological hypotheses. In this way, different computational models of cortical folding mechanisms could be independently developed, and could be easily integrated to study their interactions. After reaching this stage, it would be possible to simulate more realistic cortical folding patterns that are similar to those of a real, human cerebral cortex.

Imaging has been used in a small number of studies to investigate gyrification or folding of the cerebral cortex in animals (Neal, et al., 2007; Geng, et al., 2009). With the advancements of in-vivo noninvasive neuroimaging techniques, e.g., MRI and DTI, it is now possible to quantitate the shape dynamics of the cerebral cortex of developing human fetal brains with mathematical computation models (Levine and Bames, 1999). In the future, it will be very interesting to acquire longitudinal brain MRI data from the same developing fetus brain. In this case, it would be possible and feasible to develop computational cortex folding models based on such real longitudinal MRI data, as well as to evaluate such computational models using real fetal MRI brain data.

In the cortical folding simulations in this paper, only one fetal MRI brain data set was used as the initialization surface, due to the limited availability of such datasets. That is, all simulations were performed on this single subject's coordinate system. However, it will be important to simulate cortical folding process in the coordinate systems of different individual brains in the future. To perform such simulations, more MRI datasets from fetal brains will of course be needed, and the simulation parameters will need to be set in each individual coordinate system as well. It will also be interesting to compare, either quantitatively or qualitatively, the cortical shape dynamics simulated in different coordinate systems with different parameter settings.

Finally, we envision potential applications of the computational modeling and simulation of cortical folding. From technical and computational perspectives, the simulated cortical shape dynamics and surfaces could be used as testing or ground-truth data for the evaluation and validation of many cortical surface shape analysis algorithms and techniques, e.g., surface parcellation algorithms (Lohmann and Cramon, 2000; Rettmann, 2002; Yang and Kruggel, 2008; Li, et al., 2009), brain landmark detection algorithms (Miller, et al., 1999; Tu, 2007; Shi, et al., 2008; Li et al., 2008), conformal mapping algorithms (Angenent, et al., 1999; Bowers and Hurdal, 2003; Gu, et al., 2004; Nie, et al., 2007), surface registration algorithms (Van Essen et al., 1998; Fischl et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2004; Yeo, 2008a), and shape analysis algorithms (Cachia et al., 2003; Mangin, et al., 2004; Yu, et al., 2007a; Yeo, et al., 2008b).

From a biological perspective, it has been shown that the combination of computational modeling and quantitative experimentation can provide useful answers to many morphogenesis questions in developmental biology, e.g., how molecular signals control structural pattern formation in space and time (Lewis, 2008). To better understand cerebral cortical development from a neurobiological perspective, we believe that the combination of computational simulations of cortical folding and in-vivo neuroimaging data of fetal brain development will be truly helpful. This will provide insight into the mechanisms of cortical folding, as well as the interactions between different mechanisms. Also, in the long term, the combination of computational modeling and neuroimaging might be helpful in understanding the mechanisms of abnormal cortical folding resulting in neurological disorders (Levine and Barnes, 1999; Mochida and Walsh, 2004) such as Down's syndrome (Venita, 1996), the Donnai-Barrow syndrome (Kantarci et al., 2007) and lissencephaly, in which brain folds are less numerous and smaller (Clark, 2004). Results from our computational experiments demonstrate that cortical overgrowth will increase the cortical folding and convolution. This simulation result might provide theoretical clues or linkages to the following two independent studies in Autism: 1) In a MRI study of Autism (Hardan, et al., 2004), it was reported that in autistic patients the frontal cortical folding of the left hemisphere is significantly increased in and that there is also a significant inverse relationship between amount of frontal folding and age; and 2) It was reported that autistic patients demonstrate brain overgrowth at the beginning of life and slowed, or arrested, growth during early childhood (Courchesne, et al., 2007). In the future, it might be interesting to combine our folding simulation studies with longitudinal MRI studies of autistic brains and normal controls to further elucidate the relationship between brain growth and cortical folding in both Autism and normal neurodevelopment.

Acknowledgments

J Nie, L Guo and G Li were supported by the NWPU Foundation for Fundamental Research. T Liu was supported by the NIH Career Award (NIH EB 006878) and the University of Georgia start-up research funding. We would like to thank Dr. Deborah Levine (Harvard Medical School) for providing the human fetus brain MRI data in this paper. We would like to thank Dr. Lexing Ying (University of Texas, Austin) and Dr. Hui-Chen Lu (Baylor College of Medicine) for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Angenent S, Haker S, Kikinis R, Tannenbaum A. Harmonic analysis and flattening the brain surface. Proceedings of MICCAI.1999. [Google Scholar]

- Baraff B, Witkin A. Large steps in cloth simulation. SIGGRAPH. 1988;98:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Barron D. An experimental analysis of some factors involved in the development of the fissure pattern of the cerebral cortex. J Exp Zool. 1950;113:553–581. [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor PhG, Smith ADC, Hill DLG, Hawkes DJ, Cox TCS. Measures of Folding Applied to the Development of the Human Fetal Brain. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2002;21(8):953–963. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2002.803108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. 2007 http://radnet.bidmc.harvard.edu/fetalatlas/atlas.html.

- Bonnici HM, Williama T, Moorhead J, Stanfielda AC, Harris JM, Owens DG, Johnstone EC, Lawrie SM. Pre-frontal lobe gyrification index in schizophrenia, mental retardation and comorbid groups: An automated study. NeuroImage. 2007;35:648–654. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers PL, Hurdal MK. Planar Conformal Mappings of Piecewise Flat Surfaces. In: Hege HC, Polthier K, editors. Visualization and Mathematics III. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 2003. pp. 3–34. Mathematics and Visualization. [Google Scholar]

- Brown M, Keynes R, Lumsden A. The developing brain. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cachia A, Mangin JF, Riviere D, Papadopoulos-Orfanos D, Kherif F, Bloch I, Regis J. A primal sketch of the cortex mean curvature: a morphogenesis based approach to study the variability of the folding patterns. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2003;22:754–765. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.814781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright J. Labyrinthine Turing pattern formation in the cerebral cortex. J Theor Biol. 2002;217(1):97–103. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2002.3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenn A, Walsh C. Regulation of cerebral cortical size by control of cell cycle exit in neural precursors. Science. 2002;297:365–369. doi: 10.1126/science.1074192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs AM, Ramenghi LA, Cornette L, Tanner SF, Arthur RJ, Martinez D, Levene MI. Cerebral maturation in premature infants: quantitative assessment using MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(8):1577–1582. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark GD. The classification of cortical dysplasias through molecular genetics. Brain Dev. 2004;26(6):351–362. doi: 10.1016/S0387-7604(03)00093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly C. External morphology of the primate brain. Springfield: 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne E, Pierce K, Schumann CM, Redcay E, Buckwalter JA, Kennedy DP, Morgan J. Mapping early brain development in autism. Neuron. 2007;56(2):399–413. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehay C, Giroud P, Berland M, Killackey H, Kennedy H. Contribution of thalamic input to the specification of cytoarchitectonic cortical fields in the primate: effects of bilateral enuclation in the fetal monkey on the boundaries, dimensions, and gyrification of striate and extrastriate cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1996;367:70–89. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960325)367:1<70::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delingette H. Toward realistic soft-tissue modeling in medical simulation. Proceedings of the IEEE Special Issue On Surgery Simulation. 1988;86(3):512–523. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois J, Benders M, Cachia A, Lazeyras F, Ha-Vinh Leuchter R, Sizonenko SV, Borradori-Tolsa C, Mangin JF, Hüppi PS. Mapping the early cortical folding process in the preterm newborn brain. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18(6):1444–1454. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias H, Schwartz D. Surface areas of the cerebral cortex of mammals determined by stereological methods. Science. 1969;166:111–113. doi: 10.1126/science.166.3901.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis II: inflation, flattening and a surface-based coordinate system. NeuroImage. 1999;9:195–207. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Rajendran N, Busa E, Augustinack J, Hinds O, Yeo BTT, Mohlberg H, Amunts K, Zilles K. Cortical Folding Patterns and Predicting Cytoarchitecture. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18(8):1973–1980. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng G, Johnston L, Yan E, Walker D, Egan G. Modelling cerebral cortical folding. Proceedings of Workshop on Computational Biomechanisms. Int Conf Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv; 2007. pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Geng G, Johnston LA, Yan E, Britto JM, Smith DW, Walker DW, Egan GF. Biomechanisms for Modelling Cerebral Cortical Folding. Med Image Anal. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.media.2008.12.005. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman P, Galkin T. Prenatal removal of frontal association cortex in the fetal rhesus monkey: anatomical and functional consequences in postnatal life. Brain Res. 1978;152:451–485. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)91103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinspun E, Hirani AN, Desbrun M, Schröder P. Discrete Shells. ACM SIGGRAPH/Eurographics symposium on Computer animation; 2003. pp. 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Grove EA, Fukuchi-Shimogori T. Generating the cerebral cortical area map. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2003;26:355–380. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Wang Y, Chan TF, Thompson PM, Yau ST. Genus Zero Surface Conformal Mapping and Its Application to Brain Surface Mapping. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2004;23(8):949–958. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2004.831226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardan Antonio Y, Jou Roger J, Keshavan Matcheri S, Varma Ravi, Minshew Nancy J. Increased frontal cortical folding in autism: a preliminary MRI study. Psychiatry Research. 2004;131(3):263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydar T, Kuan C, Flavell R, Rakic P. The role of cell death in regulating the size and shape of the mammalian forebrain. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:621–626. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.6.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgetag Claus C, Barbas Helen. Developmental mechanics of the primate cerebral cortex. Anat Embryol. 2005;210:411–417. doi: 10.1007/s00429-005-0041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgetag Claus C, Barbas Helen. Role of Mechanical Factors in the Morphology of the Primate Cerebral Cortex. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2(3):e22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarci S, Al-Gazali L, Hill RS, Donnai D, Black GCM, Bieth E, Chassaing N, Lacombe D, Devriendt K, Teebi A, Loscertales M, Robson C, Liu T, MacLaughlin DT, Noonan KM, Russell MK, Walsh CA, Donahoe PK, Pober BR. Mutations in megalin, a multi-ligand receptor, cause Donnai-Barrow syndrome characterized by corpus callosum, ocular, neurosensory, craniofacial, and diaphragmatic defects. Nature Genetics. 2007;39:957–959. doi: 10.1038/ng2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury M, Rehen S, Contos J, Higgins C, Chun J. Nonproliferative effects of lysophosphatidic acid enhance cortical growth and folding. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1292–1299. doi: 10.1038/nn1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan LM, Yamashita Y, Tang Y, Sugahara T, Takahashi M, Ohba T, Okamura H. Normal Fetal Brain Development: MR Imaging with a Half-Fourier Rapid Acquisition with Relaxation Enhancement Sequence. Radiology. 2000;215:205–210. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.1.r00ap05205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gros Clark W. essays on growth and form. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1945. Deformation patterns on the cerebral cortex; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Levine D, Barnes PD. Cortical maturation in normal and abnormal fetuses as assessed with prenatal MR imaging. Radiology. 1999;210:751–758. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.3.r99mr47751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J. From signals to patterns: space, time, and mathematics in developmental biology. Science. 2008;322(5900):399–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1166154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Liu T, Nie J, Guo L, Wong STC. A Novel Method for Cortical Sulcal Fundi Extraction. Int Conf Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv; 2008. pp. 270–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Guo L, Nie J, Liu T. Automatic cortical sulcal parcellation based on surface principal direction flow field tracking. NeuroImage. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.039. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Guo L, Li G, Nie J, Faraco C, Zhao Q, L Miller SL, Liu T. Gyral folding pattern analysis via surface profiling, Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (MICCAI) 2009 doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-04268-3_39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Shen D, Davatzikos C. Deformable Registration of Cortical Structures via Hybrid Volumetric and Surface Warping. NeuroImage. 2004;22(4):1790–801. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Nie J, Tarokh A, Guo L, Wong STC. Reconstruction of Central Cortical Surface from MRI Brain Images: Method and Application. NeuroImage. 2008;40(3):991–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann G, Von Cramon DY. Automatic labelling of the human cortical surface using sulcal basins. Med Image Anal. 2000;4(3):179–188. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(00)00024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamud N, Hirano A. Atlas of neuropathology. 2nd rev. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Mangin JF, Riviére D, Cachia A, Duchesnay E, Cointepas Y, Papadopoulos-Orfanos D, Collins DL, Evans AC, Régis J. Object-based morphometry of the cerebral cortex. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2004;24(8):968–982. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2004.831204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MI, Josh SC, Christensen GE. Brain Warping. Academic Press (Elsevier Science & Technology Books); 1999. Large Deformation Fluid Diffeomorphisms for Landmark and Image Matching; pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Mochida GH, Walsh CA. Genetic basis of developmental malformations of the cerebral cortex. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(5):637–640. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.5.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed A, Zacharaki E, Shen D, Davatzikos C. Deformable registration of brain tumor images via a statistical model of tumor-induced deformation. Med Image Anal. 2006;10:752–763. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monuki ES, Walsh CA. Mechanisms of cerebral cortical patterning in mice and humans. Nature Neuroscience. 2001;4(1):199–1206. doi: 10.1038/nn752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J. Mathematical biology. 2nd. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Neal J, Takahashi M, Silva M, Tiao G, Walsh CA, Sheen VL. Insights into the gyrification of developing ferret brain by magnetic resonance imaging. J Anat. 2007;210(1):66–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark NM. A method of computation for structural dynamics. ASCE J Engineering Mechanics Division. 1959;85(EM 3):67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Nie J, Liu T, Li G, Young G, Tarokh A, Guo L, Wong STC. Least-Square Conformal Brain Mapping with Spring Energy. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2007;31(8):656–664. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary DD. Do cortical areas emerge from a protocortex? Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:400–406. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary DD, Nakagawa Y. Patterning centers, regulatory genes and extrinsic mechanisms controlling arealization of the neocortex. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2002;12:14–25. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00285-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Kubik S, Abernathy C. Atlas of the cerebral sulci. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rademacher J, Morosan P, Schormann T, Schleicher A, Werner C, Freund H, Zilles K. Probabilistic mapping and volume measurement of human primary auditory cortex. NeuroImage. 2001;13:669–683. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan R, Lawton W, Ranjan SR, Viswanathan RR. A continuum mechanics-based model for cortical. Growth J Theor Biol. 1997;187:285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. Specification of cerebral cortical areas. Science. 1988;241:170–176. doi: 10.1126/science.3291116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. A Century of Progress in Corticoneurogenesis: From Silver Impregnation to Genetic Engineering. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:i3–i17. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhk036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettmann ME, Han X, Xu C, Prince JL. Automated sulcal segmentation using watersheds on the cortical surface. NeuroImage. 2002;15(2):329–344. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman D, Stewart R, Hutchinson J, Caviness V., Jr Mechanical model of brain convolutional development. Science. 1975;189:18–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1135626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaer M, Schmitt JE, Glaser B, Lazeyras F, Delavelle J, Eliez S. Abnormal patterns of cortical gyrification in velo-cardio-facial syndrome (deletion 22q11.2): An MRI study. Psychiatry Research. 2006;146(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Thompson PM, Dinov I, Toga AW. Hamilton-Jacobi skeleton on cortical surfaces. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2008;27(5):664–673. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2007.913279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel DA, Hurdal MK. Chemically based mathematical model for development of cerebral cortical folding patterns. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009 Sep;5(9):e1000524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sur M, Rubenstein JL. Patterning and Plasticity of the Cerebral Cortex. Science. 2005;310:805–810. doi: 10.1126/science.1112070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planar Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Brain. Thieme; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Terzopoulos D, Platt J, Barr A, Fleischer K. Elastically Deformable Models. Computer Graphics. 1987;21:205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Todd P. A geometric model for the cortical folding pattern of simple folded brains. J Theor Biol. 1982;97:529–538. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(82)90380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro R, Burnod Y. A Morphogenetic Model of the Development of Cortical Convolutions. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1900–1913. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro R, Perron M, Pike B, Richer L, Veillette S, Pausova Z, Paus T. Brain Size and Folding of the Human Cerebral Cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18(10):2352–2357. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z, Zheng S, Yuille AL, Reiss AL, Dutton RA, Lee AD, Galaburda AM, Dinov I, Thompson PM, Toga AW. Automated extraction of the cortical sulci based on a supervised learning approach. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2007;26(4):541–552. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2007.892506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccarino FM, Fagel DM, Ganat Y, Maragnoli ME, Ment LR, Ohkubo Y, Schwartz ML, Silbereis J, Smith KM. Astroglial cells in development, regeneration, and repair. The Neuroscientist. 2007;13:173–185. doi: 10.1177/1073858406298336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen DC, Maunsell JHR. Two-dimensional maps of the cerebral cortex. J Comput Neurology. 1980;191:255–281. doi: 10.1002/cne.901910208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen DC. A tension-based theory of morphogenesis and compact wiring in the central nervous system. Nature. 1997;385:313–318. doi: 10.1038/385313a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen DC, Drury HA, Joshi S, Miller MI. Functional and structural mapping of human cerebral cortex: solutions are in the surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:788–795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venita J. Pathology in an infant with Down's syndrome and Tuberous Sclerosis. Pediatrics Neurology. 1996;15:57–59. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(96)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C, Cepko CL. Clonally related cortical cells show several migration patterns. Science. 1988;241:1342–45. doi: 10.1126/science.3137660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C, Cepko CL. Widespread dispersion of neuronal clones across functional regions of the cerebral cortex. Science. 1992;255:434–440. doi: 10.1126/science.1734520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker W. Why does cerebral cortex fissure and fold? A review of determinants of gyri and sulci. Cereb cortex. 1990;8:3–136. [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Pham DL, Pettmann ME, Yu DN, Prince JL. Reconstruction of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 1999;18(6):467–480. doi: 10.1109/42.781013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Kruggel F. Automatic segmentation of human brain sulci. Med Image Anal. 2008;12(4):442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo BTT, Sabuncu M, Vercauteren T, Ayache N, Fischl B, Golland P. Spherical Demons: Fast Surface Registration. Int Conf Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv; 2008. pp. 745–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo BTT, Yu P, Grant PE, Fischl B, Golland P. Shape Analysis with Overcomplete Spherical Wavelets. Int Conf Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv; 2008. pp. 468–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P, Yeo BTT, Grant PE, Fischl B, Golland P. Cortical Folding Development Study based on Over-complete Spherical Wavelets. Int Conf Computer Vision ICCV; 2007. pp. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P, Han X, Segonne F, Pienaar R, Buckner RL, Golland P, Grant PE, Fischl B. Cortical Surface Shape Analysis Based on Spherical Wavelets. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2007;26(4):582–597. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2007.892499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, Smith RG, Ho S, Gee JC, Gerig G. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: Significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1116–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X, Staib LH, Schultz RT, Duncan JS. Segmentation and Measurement of the Cortex from 3D MR Images Using Coupled Surfaces Propagation. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1999;18(10):927–937. doi: 10.1109/42.811276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Guo L, Li G, Nie J, Liu T. Parametric representation of cortical surface folding via polynomials, Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (MICCAI) 2009 doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-04271-3_23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilles K, Armstrong E, Schleicher A, Kretschmann HJ. The human pattern of gyrification in the cerebral cortex. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1988;179(2):173–179. doi: 10.1007/BF00304699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]