Abstract

AIM: To investigate the procedure, feasibility and effects of laparoscope-assisted continuous circulatory hyperthermic intraperitoneal perfusion chemotherapy (CHIPC) in treatment of malignant ascites induced by peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancers.

METHODS: From August 2006 to March 2008, the laparoscopic approach was used to perform CHIPC on 16 patients with malignant ascites induced by gastric cancer or postoperative intraperitoneal seeding. Each patient underwent CHIPC three times after laparoscope-assisted perfusion catheters placing. The first session was completed in operative room under general anesthesia, 5% glucose solution was selected as perfusion liquid, and 1500 mg 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and 200 mg oxaliplatin were added in the perfusion solution. The second and third sessions were performed in intensive care unit, 0.9% sodium chloride solution was selected as perfusion liquid, and 1500 mg 5-FU was added in the perfusion solution alone. CHIPC was performed for 90 min at a velocity of 450-600 mL/min and an inflow temperature of 43 ± 0.2°C.

RESULTS: The intraoperative course was uneventful in all cases, and the mean operative period for laparoscope-assisted perfusion catheters placing was 80 min for each case. No postoperative deaths or complications related to laparoscope-assisted CHIPC occurred in this study. Clinically complete remission of ascites and related symptoms were achieved in 14 patients, and partial remission was achieved in 2 patients. During the follow-up, 13 patients died 2-9 mo after CHIPC, with a median survival time of 5 mo. Two patients with partial remission suffered from port site seeding and tumor metastasis,and died 2 and 3 mo after treatment. Three patients who are still alive today survived 4, 6 and 7 mo, respectively. The Karnofsky marks of patients (50-90) increased significantly (P < 0.01) and the general status improved after CHIPC. Thus satisfactory clinical efficacy has been achieved in these patients treated by laparoscopic CHIPC.

CONCLUSION: Laparoscope-assisted CHIPC is a safe, feasible and effective procedure in the treatment of debilitating malignant ascites induced by unresectable gastric cancers.

Keywords: Intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion, Laparoscopy, Chemotherapy, Gastric cancer, Malignant ascites

INTRODUCTION

Malignant ascites are a common complication induced mainly by advanced ovarian cancer and also by gastrointestinal cancers (e.g. gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, and liver cancer). Once vast malignant ascites occur in patients with advanced gastric carcinoma or postoperative peritoneal seeding, disseminated seeding metastasis can be observed. Patients would lose the opportunity to undergo surgery, and nothing can be done except treating the pyloric obstruction or other complications. In addition, the prognosis is extremely poor and the survival time is generally as low as less than 2 mo[1].

In recent years, continuous circulatory hyperthermic intraperitoneal perfusion chemotherapy (CHIPC) has appeared as a new auxiliary chemotherapy for abdominal malignant tumors. Preliminary clinical efficacy has been achieved in the prevention and treatment of malignant tumor metastasis[2-4].

Currently, laparoscope-assisted CHIPC has been used clinically to treat malignant ascites in a few medical institutions in the United States, France and Italy. In comparison with traditional CHIPC, laparoscope-assisted CHIPC has a good clinical profile and carries the benefits of definitive palliation of ascites with a minimal invasion, fewer traumas, less pain, shorter recovery time and more stable efficacy, thus avoiding the abdominal laparotomy and large incision necessary in patients with unresectable tumors[5-8]. However, little information related to the facilities, therapeutic temperature, velocity of drug perfusion or complications involved in laparoscope-assisted CHIPC has been available. This limits the widespread use of laparoscope-assisted CHIPC in clinical chemotherapy. Therefore, in this study, we present a detailed report on the use of laparoscope-assisted CHIPC in treatment of patients with malignant ascites induced by advanced gastric cancers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inclusion criteria and clinical data

This protocol was approved by Cancer Hospital of Guangzhou Medical College. From August 2006 to March 2008, 16 patients with malignant ascites induced by advanced gastric cancers were treated via laparoscope-assisted CHIPC.

The diagnosis of primary gastric cancer complicated by malignant ascites was established and existence of peritoneal diffusive seeding was verified by laparoscopic examination. Thus these patients were not well suited for the tumor resection. They had no serious cardiopulmonary diseases. Informed consent of CHIPC and laparoscopic surgery was obtained from all the patients.

As shown in Table 1, of the 16 patients in this study, there were 7 men and 9 women aged 43-74 years (median age, 56 years). Karnofsky (KPS) marks ranged from 40 to 70 points and the course of disease ranged from 5-30 d (15 d on average). There were 7 primary cases of gastric cancer and 9 cases of postoperative gastric cancer, which were diagnosed by laparotomy, gastric fiberoptic endoscopy, serum tumor markers (CEA and CA199) and ascite cytology. Ultrasonic B and laparoscopic examinations displayed 4000-9000 mL seroperitoneum in all the patients. Five patients had obvious abdominal distention, abdominal pain and oliguria or anuria with high intraperitoneal pressure caused by ascites, and no apparent palliation was found after repeated abdominal puncture drainage, 11 patients had numerous free cancer cells within the ascites, 2 cases presented obvious bloody ascites, and 1 case presented chyle-like ascites.

Table 1.

Clinical data of patients undergoing laparoscope-assisted CHIPC in gastric cancer complicated by malignant ascites

| Case No. | Gender | Age (yr) | Disease course (d) | Ascite volume (mL) [free cancer cells (+/-)] | Diagnosis | Examination | Pathology |

| 1 | F | 46 | 17 | 7000 (+) | GC | GSB | MAC |

| 2 | M | 58 | 21 | 4500 (+) | PGC | PP | M-LDAC |

| 3 | F | 73 | 18 | 6000 (-) | GC | GSB | MDAC |

| 4 | F | 58 | 12 | 4000 (+) | PGC | PP | MAC |

| 5 | M | 76 | 7 | 4800 (+) | PGC | GSB | LDAC |

| 6 | M | 58 | 9 | 9000 (+) | PGC | PP | SRCC |

| 7 | F | 45 | 12 | 7000 (-) | GC | GSB | LDAC |

| 8 | F | 59 | 80 | 4000 (+) | PGC | PP | SRCC |

| 9 | M | 60 | 21 | 4500 (+) | PGC | PP | LDAC |

| 10 | M | 67 | 13 | 4800 (-) | PGC | PP | M-LDAC |

| 11 | F | 61 | 15 | 5000 (+) | GC | GSB | LDAC |

| 12 | M | 52 | 14 | 6000 (+) | PGC | PP | MAC |

| 13 | F | 68 | 9 | 5500 (+) | PGC | PP | LDAC |

| 14 | F | 45 | 5 | 5800 (+) | GC | GSB | SRCC |

| 15 | M | 59 | 12 | 6000 (-) | PG | PP | LDAC |

| 16 | F | 72 | 16 | 7200 (-) | PGC | GSB | M-LDAC |

CHIPC: Circulatory hyperthermic intraperitoneal perfusion chemotherapy; GC: Gastric cancer; PGC: Postoperative gastric cancer; GSB: Gastroscopic biopsy; PP: Postoperative pathology; MAC: Mucinous adenocarcinoma; M-LDAC: Medium-low differentiated adenocarcinoma; SRCC: Signet ring cell cancer.

Laparoscopic examination and chemotherapeutic catheter placement

After endotracheal anesthesia, a transverse cut (10 mm long) was performed at the belly, 5 mm below the umbilicus. The seroperitoneum was extracted as completely as possible; artificial pneumoperitoneum was established via an open procedure with a pressure of 13 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa); a 10-mm Trocar was inserted into the abdominal cavity via the working port. Thereafter, the laparoscope (10 mm and 30°) was inserted via the 10 mm Trocar to examine the abdominal viscera and tumors. The site, size and clinical stages of tumors were examined laparoscopically. Patients with peritoneal diffusive seeding and unresectable tumors were advised to receive laparoscope-assisted CHIPC.

In the process of laparoscope-assisted CHIPC, three new ports were prepared under the guidance of a laparoscope. On the right side, the second and third ports (both 10 mm long) were prepared at the cross-point of the mid-clavicular line and transverse surfaces, with two finger spaces above and below the umbilicus, respectively. On the left side, the fourth port (10 mm long) was prepared at the cross-point of the mid-clavicular line and transverse surface, with two finger spaces below the umbilicus. Thereafter, under the guidance of laparoscope, a 10 mm Trocar was inserted into the abdominal cavity via the working port. Two perfusion catheters were placed in the right superior abdominal cavity via the third and fourth working ports, respectively. One drainage catheter was placed in the Douglas’ cavity of the lowest place in the pelvic cavity via the second working port. Then, the laparoscope was placed in the inferior abdomen and the Trocar was inserted. Subsequently, the laparoscope was pulled out, and the perfusion catheter was placed in the Douglas’ cavity of the lowest place in the pelvic cavity under the guidance of the Trocar.

CHIPC procedures

CHIPC was performed by our self-developed “BR TRG II type high- precision hyperthermic perfusion intraperitoneal treatment system” (authorized by two patents from China: Intraperitoneal Hyperthermic Perfusion Treatment System with patent number ZL2006200613779 and Continuous Intraperitoneal Hyperthermic Perfusion Treatment Apparatus with patent number ZL2006200613764) with precise ± 0.2°C temperature control, ± 5% flow control accuracy, and an automatic cooling function.

Patients completed the first session of CHIPC in the operating room under general anesthesia. The second and third sessions were performed in the intensive care unit on the first and second day after the operation. At the first session, 5-fluorine (1500 mg) and oxaliplatin (200 mg) were added into the 5% glucose solution (4500-6000 mL) as perfusion liquid. Then CHIPC was performed for 90 min with a velocity of 450-600 mL/min and an inflow temperature of 43 ± 0.2°C.

At the second and third sessions, pethidine hydrochloride (75 mg) and promethazine hydrochloride (25 mg) were administered by intramuscular injection less than 10 min before CHIPC. Propofol (3-8 mL/h, iv) as an anesthetic agent with a continuous vein pump. The dose was continuously adjusted according to patient status. The temperature and duration of CHIPC were the same as for the first session; 5-fluorine (1500 mg) was added to the 0.9% saline solution (4500-6000 mL) as perfusion liquid. When the third session of CHIPC was completed, the intra-abdominal perfusate and ascites were drained out. Two perfusion catheters were then pulled out, and a drainage catheter was remained most frequently in the body.

Evaluation and determination of efficacy

Two weeks later, malignant ascites were collected for the last time; the remained drainage catheter was withdrawn; and ultrasonic B reexamination was performed to evaluate ascite remission status. Thereafter, ultrasonic B or computed tomography (CT) was performed for follow-up, at least once a month. Ascite status and tumor progression were assessed. Karnofsky marks were used to evaluate ascite remission and patient quality of life before CHIPC and one and two weeks after the last CHIPC, respectively. All data were statistically analyzed using SPSS13.0 statistical software.

According to the modified WHO criteria of efficacy assessment in malignant tumors[1], clinical efficacy was divided into three grades: (1) complete remission (CR): ascites are completely absorbed after treatment sustained over 4 wk; (2) partial remission (PR): ascites are reduced by 50% and sustained over 4 wk; and (3) no consequence (NC): ascites reduced no obvious or increased after treatment.

RESULTS

Clinical efficacy

The intraoperative course was uneventful in all cases; mean operative period for laparoscope-assisted perfusion catheters placing was 80 min; no postoperative deaths or complications related to the laparoscope-assisted CHIPC procedure occurred in this study. After the first laparoscope-assisted CHIPC, the daily amount of ascite outflow was 100-300 mL. After the first day, ascite outflow gradually decreased. A week later, daily outflow was 0-30 mL. During the period from two weeks after laparoscope-assisted CHIPC to the end of follow-up, clinical CR of ascites and related symptoms were achieved in 14 of the 16 treated patients (90.5%), and PR was achieved in 2 patients (9.5%). Thus the objective remission rate (ORR = CR + PR) was 100%. The Karnofsky mark indicating patient quality of life was 50-90, which was increased significantly in comparison with before laparoscope-assisted CHIPC (P < 0.01).

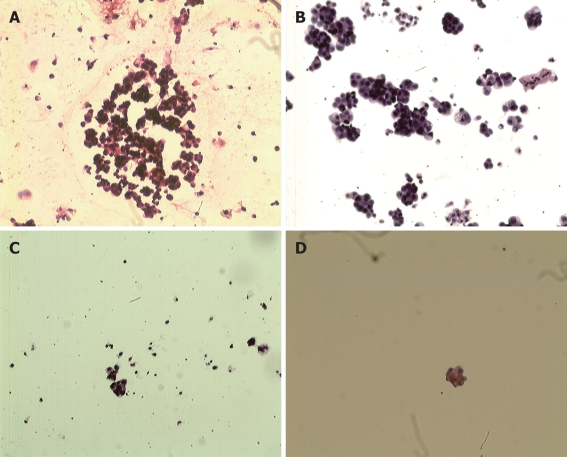

Before laparoscope-assisted CHIPC, free cancer cells were found in the ascites of 11 patients (Figure 1A). However, free cancer cells degenerated and necrotized after the first CHIPC (Figure 1B). No intact free cancer cells were found in ascites after the second laparoscope-assisted CHIPC, but degenerated and necrotized cancer cells were observed (Figure 1C). No intact free cancer cells were found in the abdomen after the third CHIPC (Figure 1D). In addition, bloody ascites in two cases and chyle-like ascites in 1 case turned clear after the first laparoscope-assisted CHIPC. In addition, the general status of patients improved after the third laparoscope-assisted CHIPC. Mental status, appetite and body weight improved, and symptoms of anemia were obviously alleviated. Thus, satisfactory initial clinical efficacy has been achieved in these patients treated by laparoscope-assisted CHIPC.

Figure 1.

Cancer cells ascites. A: Numerous free cancer cells were found in ascites before circulatory hyperthermic intraperitoneal perfusion chemotherapy (CHIPC) (HE, × 100 ); B: Intact free cancer cells in ascites clearly reduced in number, and some degenerated and necrotized after the first CHIPC (HE, × 100); C: No intact free cancer cells but rather degenerated and necrotized cells were found in ascites after the second CHIPC; D: No free cancer cells were found in ascites after the third CHIPC.

Side effects

In the course of laparoscope-assisted CHIPC, patients had no obviously abnormal vital signs except for transient fever, abdominal distension and bellyache. Dynamic reexamination in the anterior, median and posterior phases of laparoscope-assisted CHIPC revealed no anomalies in hepatorenal functions. Bone marrow suppression of I-II degrees was observed in three cases and slight gastrointestinal reaction in one case; and symptoms were remitted after symptomatic treatment. In addition, there were no complications, such as abdominal incision infection or adhesive ileus, after the laparoscope-assisted CHIPC operation.

Follow-up and prognosis

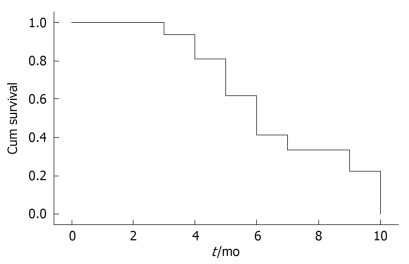

Clinical efficacies of laparoscope-assisted CHIPC in patients with gastric cancer complicated by malignant ascites are summarized in Table 2. All patients had complete follow-up data. During the follow-up (2-9 mo), 13 patients survived from 2 to 9 mo with a median survival time of 5 mo. The causes of death were intestinal obstruction (7 cases), gastrointestinal bleeding (3 cases), or cachexia (3 cases). Two patients with partial remission suffered from port-site seeding of the tumor and died within 2 and 3 mo after treatment, respectively. Three patients still alive today survived 4, 6 and 7 mo, respectively. Five patients failed in resection of the primary lesions in the re-laparotomy, and cecal fistula or ileal fistula was made in 4 patients for treatment of intestinal obstruction induced by tumor infiltration. The diagramed survival curves are shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Clinical efficacy of laparoscope-assisted CHIPC in patients with gastric cancer complicated by malignant ascites

| Case No. | Therapeutic outcome | Port-site seeding (+/-) |

KPS mark |

Survival time (mo) | Death/living | |

| Before treatment | After treatment | |||||

| 1 | CR | - | 40 | 80 | 9 | Death |

| 2 | CR | - | 60 | 90 | 7 | Death |

| 3 | CR | - | 60 | 70 | 5 | Death |

| 4 | CR | - | 50 | 80 | 5 | Death |

| 5 | CR | - | 70 | 90 | 7 | Death |

| 6 | CR | - | 50 | 70 | 4 | Death |

| 7 | PR | + | 40 | 60 | 2 | Death |

| 8 | CR | - | 50 | 70 | 4 | Death |

| 9 | CR | - | 50 | 90 | 5 | Death |

| 10 | CR | - | 60 | 80 | 5 | Death |

| 11 | CR | - | 60 | 80 | 4 | Death |

| 12 | PR | + | 50 | 70 | 3 | Death |

| 13 | CR | - | 40 | 80 | 7 | Death |

| 14 | CR | - | 70 | 80 | 7 | Living |

| 15 | CR | - | 60 | 70 | 4 | Living |

| 16 | CR | - | 60 | 80 | 6 | Living |

KPS: Karnofsky; CR: Complete remission; PR: Partial remission.

Figure 2.

Diagrammed survival curves of patients undergoing laparoscopic CHIPC in gastric cancer complicated by malignant ascites.

DISCUSSION

Malignant ascites induced by malignant tumors in the abdominal cavity (e.g. ovarian cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, and other intra-abdominal cavity) are a common complication of intraperitoneal malignant tumors. The prognosis is extremely poor and the survival time is very short[1]. Gastric cancer is one of the most common intraperitoneal malignant tumors complicated by malignant ascites. Patients with gastric cancer complicated by malignant ascites suffer mostly from the rapid increase in ascites in addition to the clinical symptoms, vital signs and cachexia of primary diseases. However, diuretic treatment is not effective; single-puncture drainage of ascites leads to rapid re-growth; and multiple puncture drainage of ascites can cause severe complications such as hypoalbuminemia and hydrogen electrolyte disturbance. The ascites cause abdominal distention, abdominal pain and oliguria or anuria, which strongly impact the quality of life and render clinical treatment difficult. Therefore, suppressing or eliminating the rapid growth of ascites has great significance in the comprehensive treatment of patients with advanced gastric carcinoma or postoperative celiac diffusive seeding[1].

In recent years, CHIPC has appeared as a new auxiliary chemotherapy for intraperitoneal malignant tumors. Hyperthermic chemotherapeutic liquid at large doses facilitates a full and effective reach of the drugs to the tiny celiac carcinoma metastases. Perfusion chemotherapy affects mechanical removal of intra-abdominal free cancer cells. During the perfusion, chemotherapeutic drugs are locally administered to the abdominal cavity, which leads to a high, constant and sustained local drug concentration. However, fewer drugs enter into the systemic circulation, which reduces the systemic side-effects. Therefore, CHIPC has obvious advantages in comparison with simple intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the treatment of malignant ascites. Preliminary efficacy has been achieved in the prevention and treatment of the peritoneal seeding of malignant tumors[5-8].

In the process of laparoscope-assisted CHIPC, the site, size and clinical stages of tumors are laparoscopically examined. Patients with peritoneal diffusive seeding and unresectable tumors are advised to undergo laparoscope-assisted CHIPC. Laparoscope-assisted CHIPC integrates the benefits of a definitive palliation of ascites with a minimal invasion, which leads to fewer traumas, less pain, shorter recovery time and solid efficacy, thus avoiding the abdominal laparotomy and large incision necessary in patients with unresectable tumors. Therefore, laparoscope-assisted CHIPC is a potential therapy for malignant ascites[9-12].

Ferron et al[13] performed laparoscope-assisted CHIPC on five adult pigs in France. Trocar was placed in the four celiac corners; omental total resection was performed. The final Trocar below the umbilicus was positioned using Dapdics, which is helpful in operating upon the ansa intestinalis. The abdominal cavity was filled with hot saline for 30 min at 43°C. As a result, the liquid was well distributed in the intra-abdomen with the appropriate temperature, and no surgical complications occurred. Therefore, the authors suggest that laparoscope-assisted CHIPC is safe and feasible for chemotherapy of malignant ascites.

Gesson-Paute et al [14] performed laparoscope-assisted CHIPC on ten adult pigs to investigate the changes in pharmacokinetics. In the experiment, perfusion and drainage catheters were laparoscopically placed in the upper and lower abdominal quadrants. In control animals, drainage catheters were placed laparotomically. CHIPC was performed with perfusion liquid containing oxaliplatin (460 mg/m2) for 30 min at 41-43°C. The perfusion liquid was sampled every minute to determine the drug concentration. The results showed that the operation was performed smoothly without complications. Drug absorption rate was 41.5% in the experimental group but 33.4% in the control. This difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.0543, n = 5). The half-life of oxaliplatin in laparoscope-assisted CHIPC was significantly shorter than that in laparotomic CHIPC (37.5 min vs 59.3 min, P = 0.02), which indicates that the adsorption of oxaliplatin in laparotomic CHIPC is significantly faster than that in laparotomic CHIPC, leading to increased clinical efficacy. In addition, the celiac drug kinetic curvature for laparoscopic and laparotomic CHIPC was 16.3 vs 28.1, P = 0.02, respectively, which reflects intraperitoneal barrier penetration of oxaliplatin. Therefore, the authors believed that laparoscope-assisted CHIPC-associated pharmacokinetics elucidate intraperitoneal drug adsorption and support the viewpoint that laparoscope-assisted CHIPC is safe, with robust clinical efficacy.

Facchiano et al [15] treated five patients with malignant ascites after palliative resection of gastric cancer by laparoscope-assisted CHIPC in a hospital affiliated to the Paris University. Celiac perfusion and drainage catheters were laparoscopically placed in the upper and lower abdominal quadrants, and laparoscope-assisted CHIPC was performed with perfusion liquid containing mitomycin plus platinum for 60-90 min at an inflow temperature of 45°C. The results showed that the operation went on smoothly without related complications for a mean 181 min; malignant ascites were eliminated in all 5 cases. The authors suggest that laparoscope-assisted CHIPC in patients with malignant ascites after palliative resection of gastric cancer is safe and feasible, with robust clinical effect.

Garofalo et al[16] performed laparoscope-assisted CHIPC on 14 cases of malignant ascites and five cases of gastric cancer, three cases of colorectal cancer, three cases of ovarian cancer, two cases of breast cancer and one case of intraperitoneal pseudomyxoma, respectively. Laparoscope-assisted CHIPC was performed with chemotherapeutic drugs (e.g. carboplatin, cisplatin and mitomycin according to the primary tumor type) for 90 min at inflow temperature of 42°C. Four drainage catheters were laparoscopically placed in the upper and lower abdominal quadrants and were pulled out after perfusion. The results indicated that malignant ascites had been well controlled in all 14 cases, and postoperative CT scanning confirmed pelvic effusion in one case. The authors conclude that laparoscope-assisted CHIPC is safe and efficient for chemotherapy of patients who suffer from advanced malignant tumors complicated by ascites and peritoneal seeding and who are not suited for cytoreductive surgery. However, the prerequisites are surgeon’s experience with laparoscopic tumor staging and patient’s capacity to undergo laparoscope-assisted CHIPC.

Knutsen et al[17] performed laparoscope-assisted CHIPC on five patients who underwent laparotomic cytoreductive surgery three to eight weeks earlier. The primary diseases included adenocarcinoma of the cecum in one case, appendiceal adenocarcinoma in three cases and gallbladder adenocarcinoma in one case. The inflow temperature was 42.1°C and outflow temperature was 40.5°C. After the operation, one patient exhibited port-site seeding, one patient died of tumor progression, and three patients survived without tumor progression and enjoyed a normal quality of life within four months after laparoscope-assisted CHIPC. The author suggests that laparoscope-assisted CHIPC after laparotomic cytoreductive surgery can guarantee the constant velocity of perfusion and maintain a stable intra-abdominal temperature.

In the process of CHIPC, drainage tubes tend to be plugged up by the great omentum or intestinal canals, so unobstructed drainage is the key to successful CHIPC. Through the long-term observation of clinical practice, we have mastered reliable means to place laparoscope-assisted CHIPC tubes and prevent jamming of the drainage tube. Drainage tubes which pass through the perforations of the right upper quadrant or left upper quadrant are placed in the lowest pelvic cavity (Douglas’ cavity), and perfusion tubes are placed in the abdominal hepatorenal recess and the splenic recess through the perforations of the right lower quadrant or left lower quadrant, respectively. When undergoing laparoscope-assisted CHIPC, the patient is placed in the supine or head-high-foot-low (15º) positions. After the abdominal cavity is full of liquid, drainage tubes are open to drain the liquid, with help of the body position. The great omentum and intestinal canals are difficult to position within the pelvic cavity and therefore unlikely to plug up the drainage tube, thus unobstructed circulatory perfusion is needed. If pelvic drainage tubes are plugged up, smooth drainage can be ensured by changing infusion tube from the right upper quadrant (hepatorenal recess) into drainage tube to the lower quadrant (Douglas’ cavity) and changing the patient,s position from head low to supine position. In this study, all the patients suffered from gastric cancer-induced malignant ascites and their great omentums were all excised or contracted into clumps. The abdominal cavity volume was big enough to ensure smooth drainage; there was no failure in the drainage tube jam in laparoscope-assisted CHIPC.

We have successfully developed a High Precision Intraperitoneal Hyperthermic Perfusion Treatment system with independent intellectual property rights. In this study, we used this machine for laparoscope-assisted CHIPC to treat 16 patients with malignant ascites induced by peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancers.All patients with ascites have remitted which indicates a 100% effective rate as reported by other authors[15,17]. Bloody ascites in two cases and chyle-like malignant ascites in one case turned clear very quickly after the first laparoscope-assisted CHIPC. The median survival time was 5 mo, which is prolonged as compared with the traditional therapy, and other reports as well[16,17]. General status, mental status, appetite and body weight improved, symptoms of anemia were alleviated, and initial clinical efficacy was satisfactory in the patients. All these results imply that laparoscope-assisted CHIPC has good clinical efficacy.

In addition, our clinical observations indicate that the primary tumors remain or even that peritoneal seeding foci are aggravated after laparoscope-assisted CHIPC. However, the symptoms associated with malignant ascites decreased or disappeared completely and ultrasonic B examination has not revealed ascite recurrence. The theory of this system remains to be elucidated. At the same time, bloody and chylous ascites became clear very quickly after laparoscope-assisted CHIPC, a process which also requires further studies.

Port-site seeding is a frequent problem for laparoscopic doctors. Patients who undergo laparoscope-assisted CHIPC have many free cancer cells in the abdominal cavity and more severe port-site seeding. Two patients with port-site seeding are included in this study and exhibited only partial remission after laparoscope-assisted CHIPC, which indicates poor clinical efficacy. However, this study includes only a limited number of cases, and the influence of laparoscope-assisted CHIPC on the quality of life and long-term survival of patients requires further researches.

In conclusion, laparoscope-assisted continuous circulatory intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion chemotherapy (CHIPC) in gastric cancer complicated by malignant ascites guarantees the uniform velocity of perfusion liquid, maintains the stable intra-abdominal temperature, facilitates a full and effective reach of the drugs to the celiac cancers, and has advantages such as minimal invasion, less pain and short recovery time. These factors contribute to achieving a good clinical efficacy, including improved quality of life and prolonged survival. Therefore, laparoscope-assisted CHIPC is safe and feasible for a widespread clinical use.

COMMENTS

Background

Malignant ascites is a common complication of advanced peritoneal malignant tumors, and treatment of this malady is very difficult clinically. Continuous circulatory hyperthermic intraperitoneal perfusion chemotherapy (CHIPC) has achieved satisfactory therapeutic effects in treatment of malignant ascites.

Research frontiers

Laparoscope-assisted CHIPC integrates the benefits of definitive palliation of gastric cancer complicated by malignant ascites with fewer traumas, less pain, shorter recovery time and more stable efficacy, thus avoiding the abdominal laparotomy and large incision necessary in patients with unrespectable tumors.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Laparoscope-assisted CHIPC is a safe, feasible and effective procedure to treat debilitating malignant ascites induced by unresectable intraperitoneal carcinomatosis of gastric cancers.

Applications

Laparoscope-assisted CHIPC for gastric cancer complicated by malignant ascites has advantages such as minimal invasion, less pain and short recovery time. These factors contribute to achieving a good clinical efficacy, including improved quality of life and prolonged survival.

Terminology

CHIPC is a novel adjuvant therapy for intra-abdominal malignancies. High-doses of warm chemotherapy liquid are administered intra-abdominally so that chemotherapy drugs can have a full contact with the tumor metastases. Chemotherapeutic agents administered into the abdominal cavity have a higher, constant, and persistent drug concentration but less drugs entering the circulatory system, and few systemic toxic side effects.

Peer review

The scientific and innovative contents as well as readability of this paper can reflect the advanced levels of the clinical research in gastroenterology both at home and abroad.

Footnotes

Supported by Funds for Breakthroughs in Key Areas of Guangdong and Hong Kong Projects, No. 2006Z1-E6041; funds for Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Programs, No. 2009A030301013

Peer reviewers: Dusan M Jovanovic, Professor, Institute of Oncology, Institutski Put 4, Sremska Kamenica 21204, Serbia; Dr. Thomas Wild, Department of Surgery, Paracelsus Medical University, Feldgasse 88, Kapellerfeld 2201, Austria

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Patriti A, Cavazzoni E, Graziosi L, Pisciaroli A, Luzi D, Gullà N, Donini A. Successful palliation of malignant ascites from peritoneal mesothelioma by laparoscopic intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18:426–428. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e318173a61e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kusamura S, Younan R, Baratti D, Costanzo P, Favaro M, Gavazzi C, Deraco M. Cytoreductive surgery followed by intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion: analysis of morbidity and mortality in 209 peritoneal surface malignancies treated with closed abdomen technique. Cancer. 2006;106:1144–1153. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deraco M, Casali P, Inglese MG, Baratti D, Pennacchioli E, Bertulli R, Kusamura S. Peritoneal mesothelioma treated by induction chemotherapy, cytoreductive surgery, and intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion. J Surg Oncol. 2003;83:147–153. doi: 10.1002/jso.10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aarts F, Hendriks T, Boerman OC, Koppe MJ, Oyen WJ, Bleichrodt RP. A comparison between radioimmunotherapy and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis of colonic origin in rats. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3274–3282. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9509-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine EA, Stewart JH 4th, Russell GB, Geisinger KR, Loggie BL, Shen P. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancy: experience with 501 procedures. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:943–953; discussion 953-955. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Shammaa HA, Li Y, Yonemura Y. Current status and future strategies of cytoreductive surgery plus intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1159–1166. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esquivel J. Cytoreductive surgery for peritoneal malignancies--development of standards of care for the community. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2007;16:653–666, x. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valle M, Garofalo A, Federici O, Cavaliere F. [Laparoscopic intraperitoneal antiblastic hyperthermic chemoperfusion in the treatment of refractory neoplastic ascites. Preliminary results] Suppl Tumori. 2005;4:S122–S123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laterza B, Kusamura S, Baratti D, Oliva GD, Deraco M. Role of explorative laparoscopy to evaluate optimal candidates for cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in patients with peritoneal mesothelioma. In Vivo. 2009;23:187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valle M, Garofalo A. Laparoscopic staging of peritoneal surface malignancies. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:625–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pomel C, Appleyard TL, Gouy S, Rouzier R, Elias D. The role of laparoscopy to evaluate candidates for complete cytoreduction of peritoneal carcinomatosis and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:540–543. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benoit L, Cheynel N, Ortega-Deballon P, Giacomo GD, Chauffert B, Rat P. Closed hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy with open abdomen: a novel technique to reduce exposure of the surgical team to chemotherapy drugs. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:542–546. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9635-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferron G, Gesson-Paute A, Classe JM, Querleu D. Feasibility of laparoscopic peritonectomy followed by intra-peritoneal chemohyperthermia: an experimental study. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:358–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gesson-Paute A, Ferron G, Thomas F, de Lara EC, Chatelut E, Querleu D. Pharmacokinetics of oxaliplatin during open versus laparoscopically assisted heated intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC): an experimental study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:339–344. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9571-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Facchiano E, Scaringi S, Kianmanesh R, Sabate JM, Castel B, Flamant Y, Coffin B, Msika S. Laparoscopic hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for the treatment of malignant ascites secondary to unresectable peritoneal carcinomatosis from advanced gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:154–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garofalo A, Valle M, Garcia J, Sugarbaker PH. Laparoscopic intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy for palliation of debilitating malignant ascites. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:682–685. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knutsen A, Sielaff TD, Greeno E, Tuttle TM. Staged laparoscopic infusion of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy after cytoreductive surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1038–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]