Abstract

The multidrug-binding transcription regulator, BmrR, from Bacillus subtilis is a MerR family member that binds to a wide array of cationic lipophilic toxins to activate transcription of the multidrug efflux pump gene, bmr. Transcription activation from the σA-dependent bmr operator requires BmrR to remodel the nonoptimal 19 base pair spacer between the −10 and −35 promoter elements in order to facilitate productive RNA polymerase binding. Despite the availability of several structures of BmrR bound to DNA and drugs, the lack of a BmrR structure in its unliganded or apo, (DNA and drug-free) state hinders our full understanding of the structural transitions required for DNA binding and transcription activation. Here, we report the crystal structure of the constitutively active, unliganded BmrR mutant, BmrR(E253Q/R275E). Superposition of the ligand-free (apo BmrR(E253Q/R275E)) and DNA-bound BmrR structures reveals that apo BmrR must undergo significant rearrangement in order to assume the DNA-bound conformation, including an outward rotation of the minor groove binding wings, an inward movement of the helix-turn-helix motifs and a downward relocation of the pliable coiled coil helices. Computational analysis of the DNA-free and DNA-bound structures reveals a flexible joint that is located at the center of the coiled coil helices. This region, which is composed of residues 94 through 98, overlaps the helical bulge that is observed only in the apo BmrR structure. This conformational hinge is likely common to other MerR family members with large effector binding domains, but appears to be missing from the smaller metal-binding MerR family members. Interestingly the center-to-center distance of the recognition helices of apo BmrR is 34 Å and suggests that the conformational change from the apo BmrR structure to the bmr operator-bound BmrR structure is initiated by the binding of this transcription activator to a more B-DNA like conformation.

Keywords: BmrR, MerR family, coiled coil, transcription regulation, multidrug-binding protein

INTRODUCTION

The mercury resistance operon repressor (MerR) family of proteins regulates transcription in response to a variety of stresses including exposure to heavy metals, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and antimicrobials.[1] and [2] Members of the MerR family are categorized into two subgroups based on the nature of their effector molecules and the architecture of their ligand binding sites.[1] and [2] The first group is composed of the founding member of the family, MerR3 as well as other metal sensing regulators such as CueR, ZntR and PbrR and the oxidative stress sensor, SoxR[4; 5; 6], whilst the second group includes BmrR, BltR, Mta and TipAL[7; 8; 9; 10; 11], which have larger C-terminal effector binding domains and recognize various aromatic and organic compounds that are often toxic. MerR members share a high degree of sequence and structural homology within their first 100 amino acid residues. These residues form the DNA-binding domain, which contains a winged helix-turn-helix (wHTH) motif, and a long helix involved in formation of an antiparallel coiled coil that plays a key role in dimerization. [1; 2; 12; 13] The C-terminal ligand-binding domains vary significantly in length, composition, and fold amongst the family members.[4; 8; 14; 15] Whereas the metal sensing regulators generally possess a shorter ligand-binding domain[1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6], the second subpopulation has a much larger well defined ligand-binding pocket with varying structural folds.[8; 10; 15]

Over the years, a wealth of structural data have been accumulated for several members of this family[4; 6; 8; 9; 10; 15; 16; 17] with the BmrR protein from Bacillus subtilis being one of the better studied members. BmrR is composed of three structural components: an N-terminal DNA-binding wHTH motif plus two additional helices, one of which makes critical DNA phosphate backbone contacts; an 11 turn α helix that forms an antiparallel coiled coil with the other protomer and links the N and C-terminal domains; and a C-terminal α/β multidrug-binding domain. [10; 15; 17]

BmrR activates transcription of the multidrug efflux transporter gene bmr upon exposure to increased concentrations of various cationic aromatic antimicrobials.7 Structures of BmrR bound to various toxins and the bmr operator provided insight into the mechanism of transcription activation and multidrug recognition.[9; 15; 17] The bmr operator, like most of the operator sequences bound by MerR family members, is characterized by the presence of canonical, hexameric −10 and −35 promoter elements that are separated by a nonoptimal 19 base pair (bp) spacer. σ70 and σA controlled bacterial promoters with 19 or 20 bp spacers deviate from the typical 17 bp spacer whereby the extra base pairs causes the spatial misalignment of the promoter elements and prevents the formation of transcriptionally competent RNA polymerase initiation complexes.7 BmrR and other MerR-family proteins bind as dimers to the inverted repeats located within the spacer region and activate transcription upon binding their respective inducers. Structural distortion of the bmr operator DNA by drug-bound BmrR involves unwinding and shortening of the distance between the −10 and −35 hexamers and results in the proper alignment of these promoter elements to allow productive RNA polymerase binding.[18; 19; 20; 21] A similar DNA distortion transcription activation mechanism of the soxS and mta operators by SoxR and MtaN, respectively, has been observed in the crystal structures of SoxR-cognate operator4 and MtaN-mta operator complexes supporting the likely universality of this mechanism amongst the members of MerR family.9

Currently, only structures of the transcriptionally active conformation of full length BmrR bound to its cognate operator DNA are available.[10; 15; 17] In order to understand fully the structural transitions that occur between the different functional states of BmrR, high resolution views of each state must be obtained. Thus, the structure of the drug-free, DNA-free BmrR(E253Q/R275E) double mutant was determined to 2.8 Å resolution. This structure reveals the conformational flexibility of BmrR and pinpoints those structural changes that are necessary for the high affinity binding of BmrR to the bmr operator.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structure determination of DNA-free BmrR

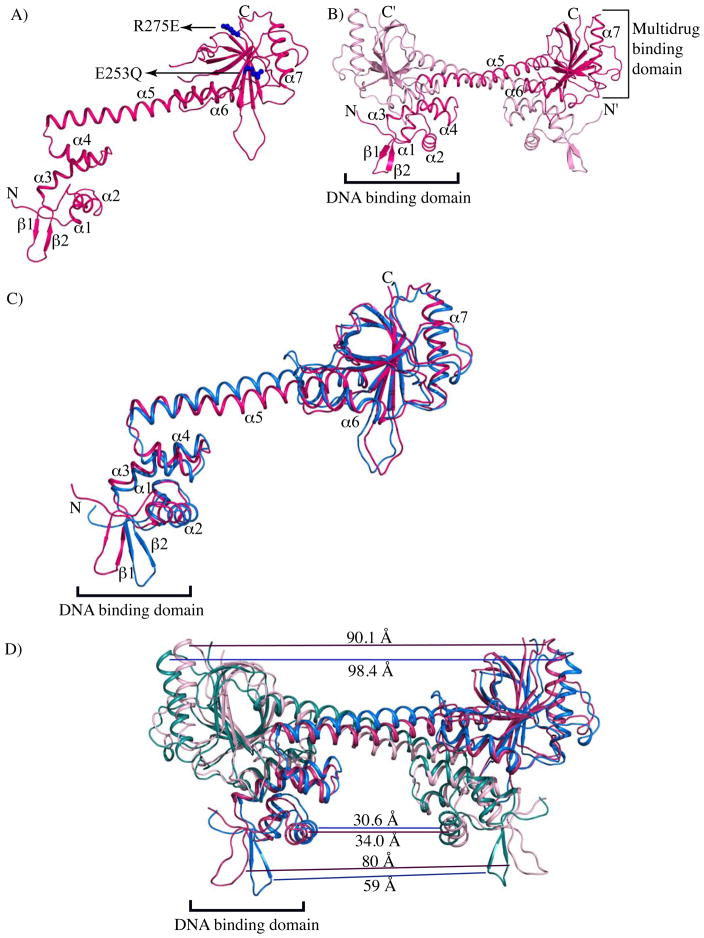

The drug-free, DNA-free BmrR(E253/R275E) protein was crystallized from solutions of 30% polyethylene glycol 4000, 0.2 M lithium sulfate, and 0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 8.5. This double mutant contains a glutamate to glutamine change at position 253, which results in a constitutively active protein, as well as a solubility enhancing substitution, arginine to glutamate, at residue 275.10 This latter substitution has no effect on DNA or drug-binding affinity (data not shown). The structure of drug-free, DNA-free BmrR(E253Q/R275E) or apo or unliganded BmrR was determined to 2.80 Å resolution by molecular replacement using the structure of full length DNA-bound BmrR as the search model after the removal of all solvent and ligands.15 The structure was refined to an Rfree of 27.4% and Rwork of 24.0% with excellent stereochemistry and geometry (Table 1). The final model of the apo BmrR structure contains residues 1-197 and 201-277 and 180 water molecules. The overall topology of secondary structure elements of the apo and DNA-bound forms of BmrR remains the same with the following arrangement: α1-α2-β1-β2-α3-α4-α5-β3-β4-α6-β5-β6-β7-β8-α7-β9-β10 (Fig. 1A and 1B). The asymmetric unit contains one protomer of BmrR and the biologically relevant dimer is formed by a crystallographic two-fold axis (Fig. 1A and 1B). As a control for the constitutive activation property of E253Q substituted BmrR and its possible effect on BmrR structure, we also crystallized and determined the structure of DNA-free BmrR(R275E) protein to 3.2 Å resolution. No major differences were observed between the ligand-free BmrR(E253Q/R275E) and BmrR(R275E) crystal structures (the root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d. ~0.1 Å) (Supplemental Fig. 1). Hence only the higher resolution apo BmrR(E253Q/R275E) structure was used for all subsequent structural analyses and comparisons.

Table 1.

Selected crystallographic data and statistics.

| Data Collection and Phasing | |

| BmrR(E253Q/R275E) | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.12 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0 - 2.80 (2.95-2.80)b |

| Overall Rsyma | 0.075 (0.46)b |

| Overall I/σ(I) | 28.3 (3.5) |

| Total Reflections (#) | 88542 |

| Unique Reflections (#) | 11336 |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) |

| Redundancy | 4.1 |

| Refinement Statistics | |

| Rwork/Rfree(%)c | 24.0/27.4 |

| Atoms | |

| Protein (#) | 2239 |

| Solvent (#) | 180 |

| B factors (Å2) | 38.0 |

| r.m.s.d. | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.38 |

| B for bonded main-chain atoms (Å2) | 1.4 |

| Ramachandran analysis | |

| Most favoured (%) | 81.1 |

| Add. allowed (%) | 18.9 |

| Gen. allowed (%) | 0.0 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.0 |

Rsym = ΣΣ|Ihkl−Ihkl(j)|/ΣIhkl, where Ihkl(j) is the observed intensity and Ihkl is the final average intensity value.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

Rwork = Σ||Fobs| − |Fcalc||/Σ|Fobs| and Rfree = Σ||Fobs| − |Fcalc||/Σ|Fobs|; where all reflections belong to a test set of 5% randomly selected reflections.

Figure 1. The structure of apo BmrR differs from that of DNA-bound BmrR.

(A) Ribbon diagram of a protomer of apo BmrR. The secondary structure elements are labelled except for the β strands of the C-terminal domain (β3 - β9) for the purposes of clarity. The positions of the E253Q and R275E substitutions are indicated by blue spheres and labelled. (B) The dimer structure of apo BmrR. The individual protomers are coloured red and pink. The DNA-binding and multidrug-binding domains are denoted and labelled accordingly. (C) Superposition of the main chains of the apo BmrR (red) and DNA-bound BmrR (blue) protomers. The DNA-bound BmrR structure was used as the reference molecule and the superposition of the apo BmrR structure was optimized for the entire chain using LSQKAB.22 (D) Superimposition of the apo BmrR and DNA-bound BmrR dimers. The apo BmrR protomers are coloured red and light pink whereas the DNA-bound BmrR protomers are blue and teal. The distances between the C-terminal domains (α7(R243Cα-R243′Cα)α7′), recognition helices (α2(Y24Cα-Y24′Cα)α2′) and the wings (β2(D39Cα-D39′Cα)-β2′) of the apo BmrR and bmr operator-bound BmrR dimers are indicated with colour-coded lines and given in ängstrom (Å). The DNA-bound BmrR was used as the reference molecule for the superposition.

Structural comparisons of apo and DNA-bound BmrR

The individual protomers of apo and DNA-bound BmrR can be superposed with an r.m.s.d. of 1.9 Å over 263 corresponding Cα atoms out of a possible 277 Cα atoms indicating significant differences between the two conformers. Changes include the relative orientation of the helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif, the wing (β2-turn-β3), the helix that forms the coiled coil (α5) and the loop preceding helix α5 (Fig. 1C). When cast in terms of the biological dimer, the recognition helix (α2) of the HTH motif has moved away from the position of DNA-bound α2 by 3.4 Å (Cα(Y24) - Cα(Y24′)) (Fig. 1D). More strikingly, the wings shift outward by 21.0 Å (Cα(D39) - Cα(D39′)) relative to their positions in the DNA-bound state, which results in a protein conformation that is unsuitable for DNA binding (Fig. 1D). Differences between the coiled coil helices (α5) of apo and DNA-bound BmrR are also found and are quite intriguing whereby the first two turns overlay well despite noticeable differences in the preceding loop (the Cα atoms of apo and DNA-bound loop residue E76 are 4.8 Å apart) and the middle six turns of α5 diverge significantly but converge over the last few turns as α5 enters the ligand-binding domain (Fig. 1D). Thus, the α5 helix of the apo BmrR has a bulge in the middle, centered near residue L95 that is not present in the structures of DNA-bound BmrR. The change is underscored by the displacement of the Cα atom of the apo residue L95 towards the DNA-binding domain by 3.4 Å (Fig. 1C and 1D). The possibility that crystal packing influences the helix α5 conformation cannot be ruled out completely. However, inspection of the packing failed to reveal any direct protein-protein interactions involving residue L95.

As might be anticipated, there are no significant differences in the overall arrangement of the secondary structure elements of the inducer-binding domains of the protomers of apo BmrR(E253Q/R275E), drug-bound, DNA-bound wild type BmrR and the constitutively active, DNA-bound BmrR(E253Q).10 Thus, the multidrug-binding pocket of the BmrR(E253Q/R275E) protein is open and resembles that of the drug-bound active conformation. Though there are slight shifts in the positions of secondary structure elements amongst the three, rhodamine 6G can be docked into the multidrug-binding pocket of BmrR(E253Q/R275Q) without steric clash or additional main chain or side chain movements (data not shown). Moreover, the previously identified “inactivating contacts” between residues Y152 and E253 appear to be broken and the “activating contacts” between residues Y170, K156, and D54′ (where the prime indicates the other protomer) are made.10

Conformational plasticity of the coiled coil

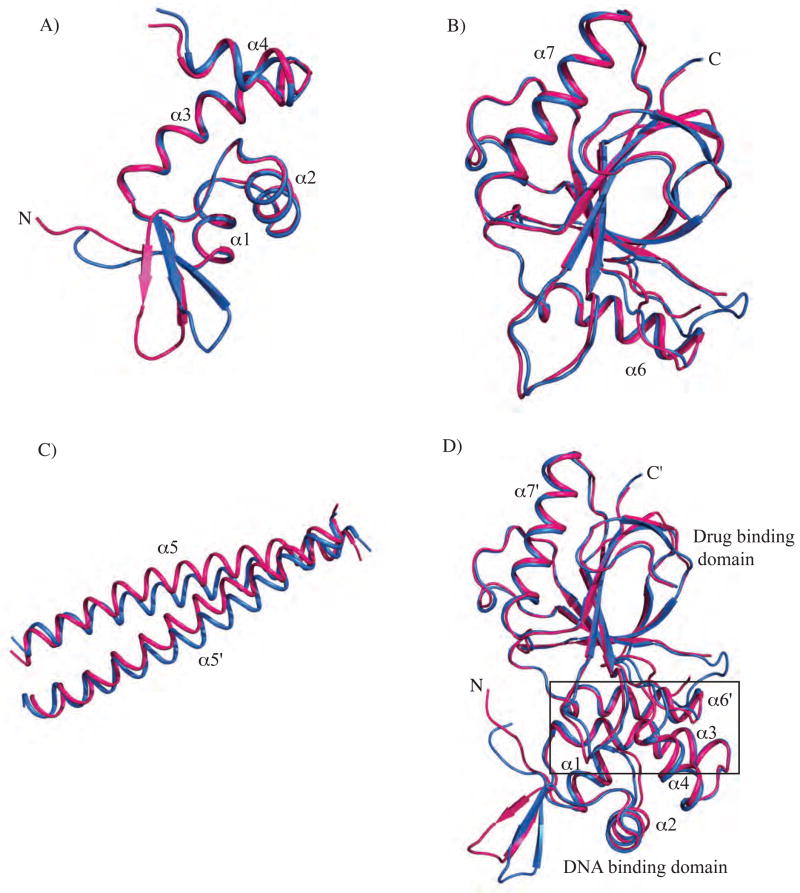

Comparisons of the individual DNA-binding and drug-binding domains of apo and DNA-bound BmrR using LSQKAB22 did not show any significant structural differences as the N-terminal domains (residues 3-77), excluding the flexible wings (residues 28-46), can be superposed onto each other with an r.m.s.d. of 0.8 Å and the C-terminal domains (residues 122-273) can be aligned with a r.m.s.d. of 0.8 Å (Fig. 2A and 2B). By contrast, the overlay of the coiled coil helices of apo and DNA-bound protomers reveals remarkable differences in their positions and orientations and superposition of the individual α5 helices (residues 78-116) results in an r.m.s.d. of 1.6 Å (Fig. 2C and Fig. 3A). Such a change in the coiled coil conformation might be expected to disturb the interfaces of the DNA-binding domain of one protomer and the multidrug-binding domain of the other protomer (and vice versa). Interestingly, this is not the case and the essentially identical interface and orientation of these two domains is preserved between the apo and DNA-bound conformations. Indeed, these interacting domains can be superposed with an r.m.s.d. of 0.6 Å (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Superposition of the individual domains of apo and DNA-bound BmrR and the interface between the DNA-binding and drug-binding domains.

All the superpositions were performed with LSQKAB22 using the DNA-bound BmrR structure as the reference molecule (A) Superposition of residues 3-77 of the N-terminal domain with the winged helix-turn-helix (wHTH) motif of the apo (coloured red) and DNA-bound BmrR (coloured blue). The wings (residues 29-47) were not included in the superposition. The helical structural elements are labelled and the position of the N-terminus (N) is indicated. (B) Superposition of residues 122-277 of the C-terminal drug-binding domain of apo (red) and DNA-bound BmrR (blue). For clarity, the β strands of the drug-binding pocket are not labelled, whereas the α helices and C-termini (C) are labelled. (C) Residues 78 through 116 of the coiled coil helices (α5 and α5′) of apo (red) and DNA-bound BmrR (blue) are superposed and labelled. (D) Superposition of the interfaces between the DNA-binding domain (residues 3-77), not including the wings (residues 29-47), and drug-binding domains (residues 122′-277′) of the apo (red) and the DNA-bound conformers of BmrR (blue). The individual domains are denoted and selected secondary structure elements are labelled. The α helices of the drug-binding domain from the other protomer are indicated by a prime (′). The interface between these domains is indicated by a rectangle.

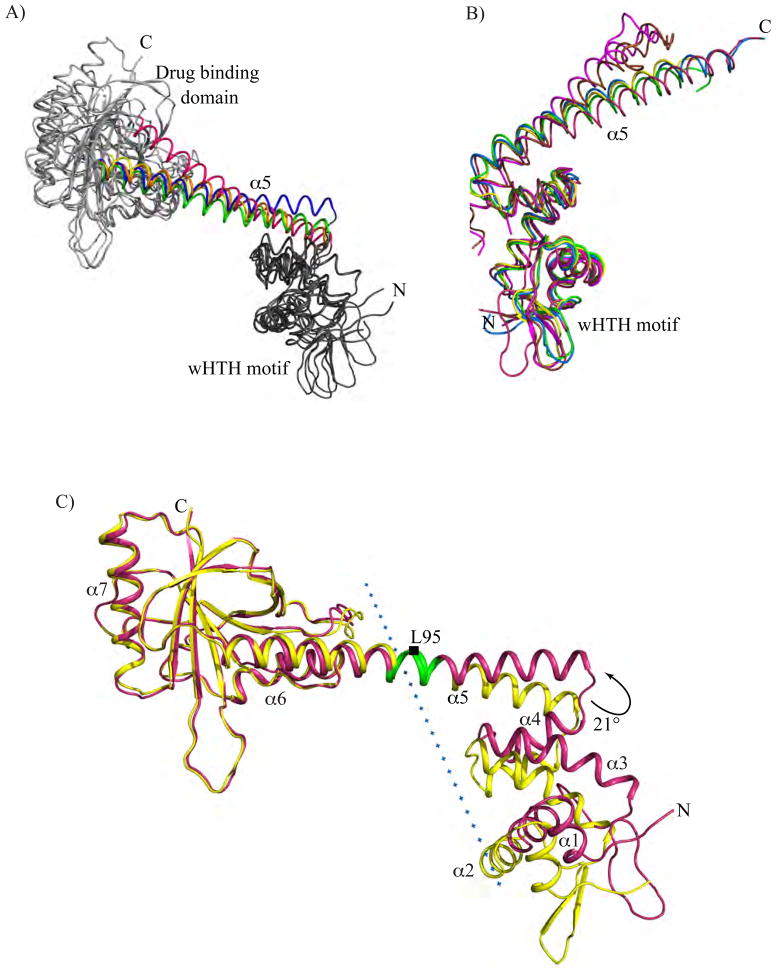

Figure 3. Conformational plasticity of the α5 coiled coil helix.

(A) Individual DNA-binding domains (residues 3-77) and drug-binding domains (residues 122-277) of a protomer from apo BmrR were superposed onto DNA-bound BmrR using LSQKAB22 and the resulting changes in the location and orientation of the coiled coil helix α5 displayed. The DNA- bound BmrR structure was used as reference molecule. The wHTH motif (in dark gray) and drug-binding domain (in light gray) are labelled. The α5 helices of DNA-bound (orange), apo (green), fixed DNA-binding domain of apo (pink), fixed drug binding-domain of apo (blue), and fixed coiled coil helix of apo (yellow) are colour coded and labelled. The N and C-termini are labelled as N and C, respectively. (B) Comparison of the positions of the α5 helices of protomers from selected structurally determined members of the MerR family. The four α helices of the DNA-binding domains (residues 3-77 of BmrR) of the protomers of different MerR family members are superposed and colour coded as follows: apo BmrR (pink), DNA bound BmrR (blue), apo MtaN (green), apo SoxR (brown), and DNA bound SoxR (magenta). The N- and C-termini are labelled as N and C, respectively. (C) A ribbon diagram depicting the two structural domains and hinge region of BmrR identified by DynDom.[26; 27; 28; 29] The protomers of apo (pink) and DNA-bound BmrR (yellow) are superposed using the drug-binding domain of each as the reference (left). The interdomain axis of rotation is indicated by a blue dotted line and the ~21° right-handed rotation angle required to superpose these two domain structures is shown by a bent black arrow. The hinge residues as identified by DynDom, where the transition between the two structures occurs, are located on helix α5 and coloured green. The helical structural elements of the protomers are labelled and the N- and C-termini are indicated. The Cα atom of residue L95 is marked with a black rectangle and labelled.

These structural data indicate that the transition from the apo to DNA-bound BmrR conformation requires the coiled coil to be conformationally plastic. Consistent with this notion is the finding that when the individual DNA-binding and multidrug-binding domains of the apo and DNA-bound structures of BmrR are analyzed, the positions of each α5 changes significantly (Fig. 3A). When the C-terminal drug-binding domains of the apo and DNA-bound BmrR are overlaid, α5 of apo BmrR must undergo an ~14° rotation to match the corresponding orientation of α5 of the DNA-bound activated state. The analogous analysis but aligning the DNA-binding domains reveals that an ~15° right handed rotation of the coiled coil helix is needed to overlay the drug-binding domains of apo and DNA-bound BmrR. Collectively, these data indicate that the DNA-binding domain of one protomer and drug-binding domain of the other protomer move as a rigid body that is tethered to their two-fold related domains by the conformationally flexible coiled coil.

Interestingly, no equivalent conformational change appears to be required for MerR family member SoxR to bind DNA. Indeed, the apo activated SoxR and DNA-bound SoxR proteins display a high degree of structural similarity with an r.m.s.d. of 0.9 Å for 105 Cα atoms out of a possible 119 atoms. Moreover, the differences between DNA-bound and DNA-free, [Fe-S]-SoxR structures are limited to a 9° outward rotation of the DNA-binding domain and a 6° outward movement of the Fe-S cluster binding domain. The end result of which is a 2.2 Å increase in the center-to-center distance between the DNA-binding recognition helices.4 Although movements centered on the SoxR α5 helix were proposed to mediate the small structural changes required for SoxR-DNA binding, the observed rotation in the coiled coil helices of SoxR is far less pronounced relative to that of BmrR.4 It is possible that the crystal structure of apo SoxR was “caught” in a conformation closer to the activated DNA-bound conformation and that similar changes in its α5 might be necessary to convert the apo, Fe-S containing conformer to the DNA-bound conformation.[23; 24; 25] Analysis of MerR family member, MtaN, shows that when the DNA-binding domains of the apo MtaN and DNA-bound MtaN are fixed, an 18° rotation of the α5 helix of apo MtaN is required to attain the DNA-bound conformation (Supplemental Fig. 2). Though the flexibility required for the MtaN conformational transition is proposed to arise from a hinge region, a five residue loop preceding the α5 helix, rotation about the coiled coil helices cannot be ruled out as the main driving force or at the least as a supplement to the hinge region movement especially in the context of the full length Mta protein.9 Structural analyses of other MerR family members, excluding CueR and ZntR, indicate that the conformational heterogeneity between structures comes from the coiled coil domain, as their DNA-binding domains, including helices α1 - α4 but excluding their wings, can be superimposed with small r.m.s.d.s ranging from 0.4 to 1.3 Å (Fig. 3B).

Domain movement analysis in BmrR by DynDom

Further analyses of the conformational changes that are required for the conversion of the DNA-free BmrR structure to the DNA-bound BmrR structure were carried out using “DynDom”.[26; 27; 28; 29] This program identifies domains on the basis of differences in their rotational properties, determines the position of the screw axis between the identified “rigid” domains and locates those residues at which the transition occurs between these domains. Two dynamic domains were identified for BmrR by DynDom: domain 1, which is composed of residues 5-94 and domain 2, which contains residues 95-275. The first of these domains contains the DNA-binding domain and approximately half of helix α5 and the second contains the second half of helix α5 and the multidrug-binding domain. Using the C-terminal domain (residues 95-275) as the fixed domain, apo BmrR must undergo a right handed rotation of ~21° to superpose its DNA-binding domain onto that of the DNA-bound protein (Fig. 3C). The hinge, about which the rotation occurs, is centered in the middle of helix α5 near residues K94 through L98. These residues display significant conformational changes in the apo BmrR structure (Fig. 1A and 3C). The interdomain screw axis identified by DynDom is located 2.1 Å from these bulged residues and runs in a plane approximately perpendicular to the helical axis of α5 (Fig. 3C). Essentially all domain movement comes from rotation, as the translation component of the screw operation is only 0.2 Å. Although the deviation of the peptide backbones between the apo and DNA-bound BmrR structures are most prominent between L95 and D96, the differences in their phi and psi angles are only, 12° and −9.7°, respectively, indicating a smooth conformational transition takes place between the two end states.

Similar DynDom analyses of other MerR family members show different results. When the apo and DNA bound structures of MerR family member MtaN were analyzed for domain movements, DynDom revealed that the apo MtaN undergoes an 11° rotation and −0.5 Å translation to match the orientation of the DNA-bound conformation (Supplemental Fig. 2). Though it involves significant rotation of the coiled coil, the origin of the screw axis and bending residues are located at the hinge region (residues 71-75) that precedes the α5 helix and originally identified in a comparison between the apo and DNA MtaN structures (Supplemental Fig. 2).[9] Since the current MtaN structures lack the large C-terminal domain, it remains to be seen whether the full length Mta employs a BmrR-like conformational changes, which occurs in the middle of the coiled coil domain. Intriguingly, a similar analysis with the apo and DNA-bound SoxR structures failed to identify two rotationally independent domains due to the lack of a significant difference between the two conformations, again pointing towards the possibilities that either the DNA-free form of SoxR takes the DNA-binding ready conformation or that crystal packing fortuitously imposed the same conformation as seen in the DNA-bound form of SoxR.

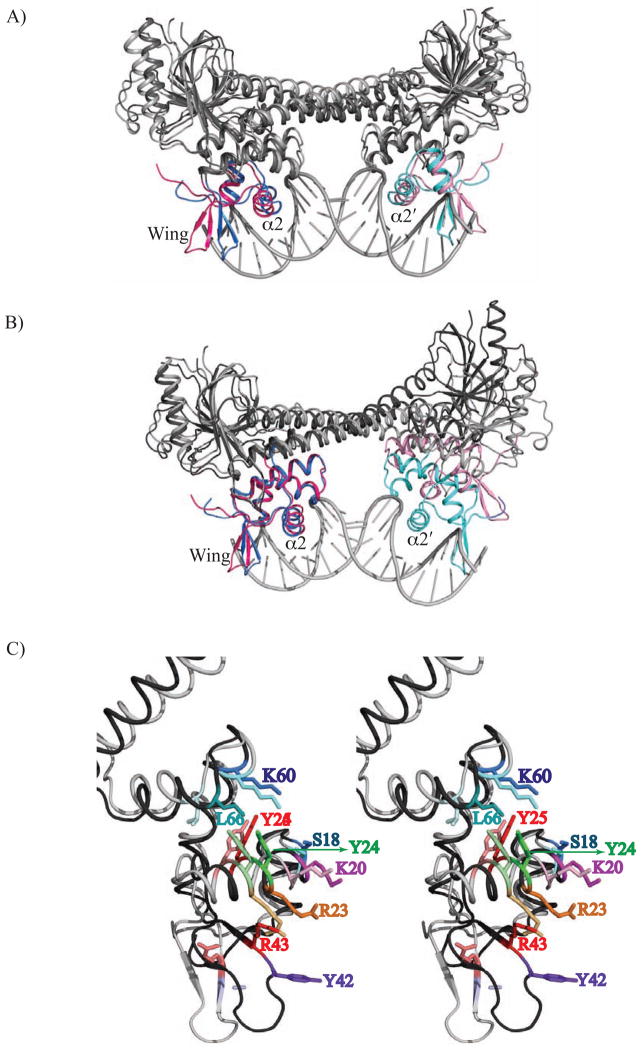

The apo BmrR conformation, activated but unsuitable for DNA binding

Superposition of the apo and DNA-bound BmrR dimers results in an r.m.s.d of 2.4 Å over 510 corresponding Cα atoms (out of a total of 554 Cα atoms). A symmetric outward displacement of the recognition helices and the minor groove binding wings is immediately evident (Fig. 4A). Indeed, an 18.8° inward rotation of each wing of apo BmrR is required to match the orientation of the wings of DNA-bound BmrR. Consequently, the wings of the apo BmrR are not only out of position to interact with bmr operator DNA productively but would clash with the DNA (Fig. 4A). Conformational flexibility of wings is not unusual in DNA-free wHTH proteins and has been documented in several transcription activators and repressors.[30; 31; 32; 33] A more dramatic visualization of the incompatibility of the apo BmrR conformation to bind the distorted bmr operator is obtained upon the superposition of the DNA-binding domain of one protomer of apo BmrR (residues 3 through 77) onto the DNA-binding domain of the DNA-bound BmrR structures (Fig. 4B). In this superposition, the DNA-binding domain of the second protomer of apo BmrR is moved upwards by approximately 9.6 Å (Cα(Y24) - Cα(Y24) distance) resulting in the displacement of its HTH motif from the major groove of the bmr operator and clearly precluding high affinity binding to this distorted DNA structure. The superposition of the apo and DNA-bound BmrR dimers also reveals a significant misalignment of the C-terminal multidrug-binding domains, which in the apo conformation are pulled as rigid bodies ~8.3 Å (Cα(R243) - Cα(R243′)) inward towards the molecular two fold axis of the dimer (Fig. 1D and Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. Apo BmrR is incompatible with high affinity binding to the transcriptionally active bmr operator or B-DNA.

(A) The structures of apo BmrR superposed onto the BmrR-bmr operator complex. The winged helix-turn-helix motifs of each protomer of apo and DNA-bound BmrR are shaded in red/pink and blue/cyan, respectively, whereas the remaining structural elements of apo BmrR are coloured dark grey and the DNA-bound BmrR, coloured light grey. The bmr operator DNA is shown as a ribbon with the bases shown as grey tubes. The DNA bound-BmrR dimer structure was used as a reference molecule and LSQKAB22 for the superposition of 510 corresponding Cα carbon atoms of apo BmrR dimer. (B) A ribbon diagram showing the results from the superposition of one DNA-binding domain of apo BmrR and DNA bound BmrR. The superposition utilised all Cα carbon atoms of the DNA-binding domain except those of the wings (residues 29-47) and LSQKAB.22 The colour coding is similar to Fig. 4A. (C) Enlarged stereoview of the relative positions of the base-specific and DNA-backbone contacting residues of apo and DNA-bound BmrR resulting from the superposition of Fig. 4A. The side chains of the amino acid residues that contact the bmr operator are shown as sticks and labelled. The side chains from DNA-bound BmrR are coloured in a dark shade and apo BmrR, in a light shade of the same colour.

The previously described BmrR-bmr operator contacts are characterized by only a few base-specific contacts, which involve primarily residues from the recognition helix, and several DNA conformation stabilizing contacts to the phosphate backbone that include residues Y24, Y25, Y42, K60 and L66.[9; 15] Interestingly, despite the 3.4 Å widening of the distance between the α2 recognition helices of apo BmrR, these helices can be placed into consecutive major grooves of the bmr operator DNA without significant steric clash (Fig. 4A). Modelling suggests that the side chain of residue K20 of the apo protein is still in position to make the base specific contacts as seen in the DNA-bound conformation (Fig. 4C). However, the BmrR recognition helices alone do not provide all the interactions that contribute to the binding affinity and likely specificity. Indeed, in the apo BmrR conformation the phosphate backbone buttressing contacts of helix α4 would be displaced significantly with the highly conserved residue L66, which is located at the amino terminus of α4 pulled away from the DNA by 7.1 Å. Such repositioning results not only in the loss of the hydrogen bond between the amide nitrogen of residue L66 and the phosphate backbone of the central T:A base pair but also abrogates the favourable α helix dipole-phosphate backbone interaction (Fig. 4C). Residues Y42 and R43, which are located in the wings, move outward by more than 7 Å and are no longer in position to contact the DNA leading to the disordering of the tyrosine side chain. DNA contacts from the side chains of residues Y24 and Y25 of the α2 recognition helix are also precluded as they shift ~2.5 Å from their positions in the transcriptionally active, DNA-bound conformation (Fig. 4C). By contrast, the side chains of R23 and K60 moved closer to their contacts in the DNA without any steric clash (Fig. 4C). Thus, despite its ability to maintain some DNA contacts, the conformation of the DNA-binding domain of apo BmrR cannot support high affinity binding to the unusually bent activated operator DNA in large part due to the loss of DNA contacts from the wings and helix α4.

Docking the apo and DNA-bound BmrR structures onto a canonical B-DNA was also done. Neither protein conformer could be superposed onto this DNA without major steric clash with the bases and sugar phosphate backbone (Supplemental Fig. 3). Thus, our structural and modelling studies suggest that apo BmrR would bind preferentially to a non B-DNA. However, given that the center-to-center distance between the recognition helices of apo BmrR is 34 Å, which matches the distance between consecutive major grooves of B-DNA, it is possible that apo BmrR employs its recognition helices to scan the mostly B-DNA bacterial chromosome to find its high affinity bmr binding site. Once located, additional codependent conformational changes in the protein and cognate DNA would follow in order to effect a high affinity complex. A similar interdependent, high affinity binding mechanism is utilised by MerR family member MtaN.9 This structure-based inference is consistent with the finding that there are no detectable differences observed in the DNase I footprints of the apo and drug-bound BmrR when bound to the bmr operator.[7] Perhaps drug binding to BmrR only results in small changes in the twist of an already bent DNA bound by drug-free BmrR that might not be detected by DNase I footprinting. It is also possible that drug-free and drug-bound BmrR bind to the bmr operator in an identical fashion. This would imply that the mechanism by which drug binding to BmrR activates transcription is perhaps through recruitment of RNA polymerase to the promoter or by changing the already bound RNA polymerase from a transcriptionally inactive to an active conformation. By sharp contrast, the metal binding MerR family members, MerR, ZntR and SoxR, generate distinct DNase I footprints upon binding cognate metals indicating that metal binding to the protein introduces structural changes in the DNA and most likely in each protein.[1; 4; 18; 25]

Conclusion

In conclusion, the structure of apo BmrR reveals the conformational plasticity of the antiparallel coiled coil, which in the absence of cognate DNA is displaced towards the DNA- binding domains and results in the rigid body displacement of the DNA-binding domains and their interfacial drug-binding domains. In addition, the pliable wings of the winged HTH motif also undergo conformational changes and take extended structures that are incapable of binding to the DNA minor groove. Conformational flexibility of the coiled coil helices and wings is likely required for the structural transitions between different functional states of the other members of the MerR family, which have larger effector binding domains. Thus, in order to bind cognate DNA apo BmrR must undergo two major conformational changes: 1) the remodelling of the α5 helices of the coiled coil and 2) a large inward movement of the wings. These changes likely require the active participation of the high affinity bmr binding site in an interdependent conformational switching mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein overexpression, purification and crystallization

Protein overexpression and Ni-NTA affinity chromatography purification of the BmrR (E253Q/R275E) protein were performed as described previously for the wild type BmrR protein.15 This protein contains the solubility enhancing R275E substitution, which made crystallisation of apo BmrR possible, and an E253Q change, which results in a constitutively active protein.10 Apo BmrR(E253Q/R275E) was crystallized at 22 °C from reservoir solutions containing 30% polyethylene glycol 4000, 0.2 M lithium sulphate, and 0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 8.5. Crystallisation was carried out using the hanging drop vapour diffusion method by mixing equal volumes of the protein and reservoir solution. Crystals appeared within a few days and stopped growing within a week. The crystals take space group I422 with cell dimensions: a = b = 168.0 Å, c = 63.1 Å. Crystallisation experiments, using the singly substituted BmrR(R275E) protein, resulted in crystals that diffract at best to only 3.2 Å.

Data collection, structure determination and refinement

X-ray intensity data were collected at the Advanced Light Source (ALS) beamline 8.3.1, Berkeley, CA, at 100 K. Data were collected using 10% glycerol as a cryoprotectant to a resolution of 2.8 Å and 3.2 Å for the BmrR(E253Q/R275E) and BmrR(R275E) proteins, respectively. Intensity data processing and scaling were done using MOSFLM and SCALA. [34; 35; 36] The structure of the BmrR(E253Q/R275E) protein (also referred to as apo BmrR) was determined by molecular replacement using the high resolution transcriptionally activated BmrR structure (DNA and gratuitous drug-bound BmrR – PDB code 3D71) as a search model and the molecular replacement program EPMR. [37; 38] Model fitting and iterative rounds of model rebuilding were done using ‘O’39 and ‘Coot’.40 All refinement was carried out using CNS.41 The structure was refined to a final Rfree of 0.274 and Rwork of 0.240 for all data in the resolution range of 50.0–2.80 Å. Selected data collection and refinement statistics are given in Table 1. The structure of the apo BmrR(R275E) protein was also determined by molecular replacement but due to its low resolution was not refined fully. Regardless no structural differences are observed between the BmrR(R275E) and BmrR(E253Q/R275E) proteins (Supplemental Fig. 1). Structure validation of the final model of the apo BmrR(E253Q/R275E) protein was assessed by PROCHECK.42 All figures were created with PyMol.43

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funds from the National Institutes of Health (grant AI048593 to R.G.B.) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (grant G-0040 to R.G.B.). We thank the beamline scientists at ALS BL 8.3.1 for their great help with data collection. We also acknowledge the Advanced Light Source supported by the Director, Office of science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Material Sciences Division, of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract No. DE-AC03-76SF00098 at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Footnotes

Accession Number

Structure factors and coordinates of BmrR(E253Q/R275E) have been deposited in the PDB and assigned code 3IAO.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brown NL, Stoyanov JV, Kidd SP, Hobman JL. The MerR family of transcriptional regulators. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2003;27:145–163. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Summers AO. Untwist and shout: a heavy metal-responsive transcriptional regulator. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3097–3101. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3097-3101.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lund PA, Brown NL. Regulation of transcription in Escherichia coli from the mer and merR promoters in the transposon Tn501. J Mol Biol. 1989;205:343–353. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90345-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watanabe S, Kita A, Kobayashi K, Miki K. Crystal structure of the [2Fe-2S] oxidative-stress sensor SoxR bound to DNA. PNAS. 2008;105:4121–4126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709188105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hobman JL, Wilkie J, Brown NL. A Design for Life: Prokaryotic Metal-binding MerR Family Regulators. BioMetals. 2005;18:429–436. doi: 10.1007/s10534-005-3717-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Changela A, Chen K, Xue Y, Holschen J, Outten CE, O’Halloran TV, Mondragon A. Molecular Basis of Metal-Ion Selectivity and Zeptomolar Sensitivity by CueR. Science. 2003;301:1383–1387. doi: 10.1126/science.1085950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed M, Borsch CM, Taylor SS, Vazquez-Laslop N, Neyfakh AA. A protein that activates expression of a multidrug efflux transporter upon binding the transporter substrates. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28506–28513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahmann JD, Sass H-J, Allan MG, Haruo S, Thompson CJ, Grzesiek S. Structural basis for antibiotic recognition by the TipA class of multidrug-resistance transcriptional regulators. EMBO J. 2003;22:1824–1834. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newberry KJ, Brennan RG. The Structural Mechanism for Transcription Activation by MerR Family Member Multidrug Transporter Activation, N Terminus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20356–20362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newberry KJ, Huffman JL, Miller MC, Vazquez-Laslop N, Neyfakh AA, Brennan RG. Structures of BmrR-Drug Complexes Reveal a Rigid Multidrug Binding Pocket and Transcription Activation through Tyrosine Expulsion. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26795–26804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804191200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baranova NN, Danchin A, Neyfakh AA. Mta, a global MerR-type regulator of the Bacillus subtilis multidrug-efflux transporters. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1549–1559. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caguiat JJ, Watson AL, Summers AO. Cd(II)-Responsive and Constitutive Mutants Implicate a Novel Domain in MerR. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3462–3471. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3462-3471.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng Q, Stalhandske C, Anderson MC, Scott RA, Summers AO. The Core Metal-Recognition Domain of MerR. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15885–15895. doi: 10.1021/bi9817562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiu ML, Viollier PH, Katoh T, Ramsden JJ, Thompson CJ. Ligand-Induced Changes in the Streptomyces lividans TipAL Protein Imply an Alternative Mechanism of Transcriptional Activation for MerR-Like Proteins. Biochemistry. 2001;40:12950–12958. doi: 10.1021/bi010328k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heldwein EEZ, Brennan RG. Crystal structure of the transcription activator BmrR bound to DNA and a drug. Nature. 2001;409:378–382. doi: 10.1038/35053138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godsey MH, Baranova NN, Neyfakh AA, Brennan RG. Crystal Structure of MtaN, a Global Multidrug Transporter Gene Activator. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47178–47184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheleznova EE, Markham PN, Neyfakh AA, Brennan RG. Structural Basis of Multidrug Recognition by BmrR, a Transcription Activator of a Multidrug Transporter. Cell. 1999;96:353–362. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80548-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Outten CE, Outten FW, O’Halloran TV. DNA Distortion Mechanism for Transcriptional Activation by ZntR, a Zn(II)-responsive MerR Homologue in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37517–37524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frantz B, O’Halloran TV. DNA distortion accompanies transcriptional activation by the metal-responsive gene-regulatory protein MerR. Biochemistry. 1990;29:4747–4751. doi: 10.1021/bi00472a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heltzel A, Lee IW, Totis PA, Summers AO. Activator-dependent preinduction binding of sigma.-70 RNA polymerase at the metal-regulated mer promoter. Biochemistry. 1990;29:9572–9584. doi: 10.1021/bi00493a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rutherford JC, Cavet JS, Robinson NJ. Cobalt-dependent Transcriptional Switching by a Dual-effector MerR-like Protein Regulates a Cobalt-exporting Variant CPx-type ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25827–25832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kabsch W. Acta Cryst. 1976;A32:922–923. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hidalgo E, Bollinger JM, Jr, Bradley TM, Walsh CT, Demple B. Binuclear [2Fe-2S] Clusters in the Escherichia coli SoxR Protein and Role of the Metal Centers in Transcription. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20908–20914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.20908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hidalgo E, Demple B. An iron-sulfur center essential for transcriptional activation by the redox-sensing SoxR protein. EMBO J. 1994;13:138–146. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hidalgo E, Demple B. Spacing of promoter elements regulates the basal expression of the soxS gene and converts SoxR from a transcriptional activator into a repressor. EMBO J. 1997;16:1056–1065. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee RA, Razaz M, Hayward S. The DynDom database of protein domain motions. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1290–1291. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayward S, Lee RA. Improvements in the analysis of domain motions in proteins from conformational change: DynDom version 1.50. Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling. 2002;21:181–183. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(02)00140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayward S. Structural principles governing domain motions in proteins. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Genetics. 1999;36:425–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steven Hayward HJCB. Systematic analysis of domain motions in proteins from conformational change: New results on citrate synthase and T4 lysozyme. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Genetics. 1998;30:144–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newberry KJ, Fuangthong M, Panmanee W, Mongkolsuk S, Brennan RG. Structural Mechanism of Organic Hydroperoxide Induction of the Transcription Regulator OhrR. Mol Cell. 2007;28:652–664. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumaraswami M, Schuman JT, Seo SM, Kaatz GW, Brennan RG. Structural and biochemical characterization of MepR, a multidrug binding transcription regulator of the Staphylococcus aureus multidrug efflux pump MepA. Nucl Acids Res. 2009;37:1211–1224. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Silva RS, Kovacikova G, Lin W, Taylor RK, Skorupski K, Kull FJ. Crystal Structure of the Virulence Gene Activator AphA from Vibrio cholerae Reveals It Is a Novel Member of the Winged Helix Transcription Factor Superfamily. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13779–13783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413781200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall DR, Gourley DG, Leonard GA, Duke EM, Anderson LA, Boxer DH, Hunter WN. The high-resolution crystal structure of the molybdate-dependent transcriptional regulator (ModE) from Escherichia coli: a novel combination of domain folds. EMBO J. 1999;18:1435–1446. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leslie A. Recent changes to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Joint CCP4 + ESF-EAMCB Newsletter on Protein Crystallography. 1992:26. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leslie A. The integration of macromolecular diffraction data. Acta Crystallographica Section D. 2006;62:48–57. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905039107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collaborative. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallographica Section D. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kissinger CR, Gehlhaar DK, Fogel DB. Rapid automated molecular replacement by evolutionary search. Acta Crystallographica Section D. 1999;55:484–491. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998012517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kissinger CR, Gehlhaar DK, Smith BA, Bouzida D. Molecular replacement by evolutionary search. Acta Crystallographica Section D. 2001;57:1474–1479. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901012458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallographica Section A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallographica Section D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR System: A New Software Suite for Macromolecular Structure Determination. Acta Crystallographica Section D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laskowski RA, Moss DS, Thornton JM. Main-chain Bond Lengths and Bond Angles in Protein Structures. J Mol Biol. 1993;231:1049–1067. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeLano WL. The PyMol Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific; Palo Alto, CA, USA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.