Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Alcohol abuse and chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections are the major etiologic factors for chronic liver disease/cirrhosis (CLD) in the United States. These CLD risk factors are highly prevalent in US adult incarcerated populations, but CLD-related mortality data from these populations are lacking. The primary objective of this study was to assess CLD-related mortality over time and across categories of race–ethnicity from 1989 through 2003 among male inmates in the Texas state prison system. The secondary objective was to examine patterns of recorded underlying, intervening, and contributing causes of death for CLD-related deaths.

METHODS

Prisoner decedent data were linked with Texas Vital Statistics multiple-cause-of-death data. Deaths were considered CLD-related if CLD or common sequelae were recorded as the underlying, intervening, or contributing causes of death. CLD-related crude annual death rates, 5-year average annual death rates, and average annual percentage changes were estimated.

RESULTS

Among male Texas prisoners from 1989 to 2003, CLD-related deaths accounted for 16% of deaths (688/4,316). CLD-related crude annual death rates were high and increased over the study period by an average of 4.5% annually, with similar rate increases across categories of race–ethnicity. CLD-related average annual death rates were higher among Hispanic prisoners than among black prisoners in each 5-year period, and were higher than those for white prisoners in the 1994–1998 and 1999–2003 periods. HBV or HCV was identified as a causal factor in more than a third (34%) of CLD-related deaths.

CONCLUSIONS

From 1989 to 2003, CLD-related death rates among male Texas prisoners were high and increased over time, particularly among Hispanics. Targeted prevention, screening, and treatment of CLD risk factors, especially HCV, and early detection and treatment of CLD should be considered as priorities of the US prison healthcare systems.

INTRODUCTION

Despite declines in chronic liver disease/cirrhosis (CLD) mortality over the last several decades, CLD has remained consistently among the 15 leading causes of death in the United States (1,2). CLD accounts for more than 25,000 deaths annually (1,2), and for more than a billion dollars in health-care costs and lost wages annually in the United States (3,4). CLD disproportionately affects men, Hispanic Americans, American Indians, and persons of low socioeconomic status, usually in their prime working years (35–64 years) (2,5,6).

Prevalence estimates of viral hepatitis and history of alcohol abuse, the primary risk factors for CLD in the United States, are substantially higher in prison populations compared with that in the non-incarcerated, general population. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in the nation’s prison population has been estimated to be as high as 10–20 times that of the general population (7–14). Similarly, the prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in prison populations has been estimated to be as much as five-fold higher than in the general population (11–14). Prevalence estimates of alcohol abuse or dependence are also relatively high in prison populations, ranging from 18 to 30% in male prisoners (15). Additionally, recent studies have suggested an elevated prevalence of liver cancer in prison populations (16), which is often comorbid with CLD.

Despite the high prevalence of CLD risk factors and related conditions in incarcerated populations (7–16), studies describing CLD-related mortality in US prison populations are lacking (17). As CLD-related mortality data may serve as a useful starting point for correctional healthcare planners and policymakers in assessing, predicting, and addressing the burden of these conditions, we conducted a study to assess the extent of CLD-related mortality in the nation’s largest prison system (18). Decedent data obtained from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) were linked with Texas Vital Statistics multiple-cause-of-death data. Linked data were used to examine trends in CLD-related death rates from 1989 through 2003 among male prisoners in TDCJ custody, and also to compare these death rates across racial–ethnic categories. CLD-related deaths were defined as deaths for which CLD was identified as the underlying cause or as an intervening or contributing cause of death. Because recent evidence suggests that the prevalence of chronic HCV infection increased over the study period in the Texas prison population (unpublished data, Harzke), and that Hispanic prisoners may be affected disproportionately by end-stage liver disease (17), our hypotheses were as follows: CLD-related death rates would show an increase over the study period; CLD-related death rates would be elevated in Hispanic prisoners compared with that in prisoners of other racial–ethnic groups; and viral hepatitis would be a causal factor in a substantial proportion (>30%) of CLD-related deaths.

METHODS

Sources of prisoner death and census data

A database, containing information on all prisoners who died in TDCJ custody during the 1989–2003 period, was maintained by the Director of the TDCJ Office of Preventive Medicine. From this database, demographic and other identifying information on decedents were extracted by the first author. These data were then linked to a multiple-cause-of-death database obtained from the Texas Bureau of Vital Statistics. Vital statistics data had been obtained from death certificates, and then corrected for common data entry errors and certifier errors in delineating multiple causes of death according to current selection rules (19). Causes of death were recorded on the death certificate by prison healthcare providers after being ascertained by autopsy, chart reviews, narrative death summaries, and/or findings of the Mortality Review Committee. As in non-correctional medical settings autopsy rates declined over the study period from ≥90% of prisoner deaths for 1989–1997 to an average of 50% for 1998–2003 (J. Pulvino, unpublished data, December 2008); however, these autopsy rates were considerably higher than those reported in non-correctional medical settings for the entire study period (20). Referencing rigorous protocols for recording deaths and determining their causes, the Director of the TDCJ Office of Preventive Medicine estimated that 100% of prisoner deaths were captured by the TDCJ decedent database, and also suggested that cause-of-death data recorded on the death certificate in TDCJ met or exceeded the quality of such data in non-correctional settings (M.F. Kelley, personal communication, October 2006). The National Center for Health Statistics estimates that state vital statistics bureaus capture ~99% of deaths (21). Use of the TDCJ and vital statistics data was approved by two institutional review boards (university and state) with prisoner advocate members and was subsequently approved by the TDCJ.

TDCJ Executive Services provided the data for calculating the average prisoner census, which was used as the denominator for calculating annual death rates. TDCJ Executive Services takes a “snapshot” census of the in-custody population on the last day of each month. For each year, the average of the 12 monthly “snapshot” censuses for males within each stratum (race–ethnicity by 10-year age categories) was calculated.

Data linkage

Six personal identifiers (first, middle, and last names, race–ethnicity, dates of birth and death) representing 10 separate codes were used to link the TDCJ decedent dataset with the State multiple-cause-of-death dataset. Linkage was accomplished using the select query function in Microsoft Access in an iterative fashion (i.e., linkage was attempted with all 10 codes, then with 9 codes, then with a different set of 9 codes, etc.). Individual links were checked for quality. A successful link required a 90% match (9 of 10 codes) with at least 7 identical codes and no more than 2 codes reflecting an apparent match, defined as non-identical codes that appeared subjectively to be due to common coding errors (e.g., inversion of first and last names, inversion of numbers in birth or death dates). Of the total number of prisoner deaths recorded in the TDCJ database (N = 4,684), 99% (N = 4,655) were linked successfully with the state multiple-cause-of-death data.

Definition of dependent variables

CLD was defined as chronic liver disease/cirrhosis and their common sequelae (e.g., hepatic coma, portal hypertension, and hepatorenal syndromes). CLD was identified by ICD-9 codes 571 and 572, and by ICD-10 codes K70, K72, K74, K75, and K76, including all subordinate codes. Deaths were considered “CLD-related ” when CLD was identified either as the underlying cause or as an intervening or contributing cause of death in vital statistics data. Defining CLD-related deaths using multiple-cause-of-death data serves to diminish the potential for two common biases that can result when relying solely on the underlying cause-of-death data. Studies that rely solely on the underlying cause of death may underestimate CLD-related deaths by defining them according to CLD-specific codes or, conversely, may overestimate CLD-related deaths by including numerous codes that represent broad disease categories (e.g., all viral hepatitis, which may include acute cases in addition to chronic cases) (22,23).

CLD-related deaths were not delineated according to whether or not they were alcohol related. Preliminary analyses indicated that, from 1999 to 2003, nearly all CLD-related deaths were unspecified with respect to alcohol use. This limitation in the data could have resulted from the change from ICD-9 to ICD-10 codes in 1999, or possibly from aforementioned changes in TDCJ protocols for ascertainment of causes of death around the same time.

Analysis

Analyses for this study were limited to male prisoners aged 25–84 years (N = 4,316). Preliminary analyses showed that only a small number of linked deaths were among females (N = 186) and among males under the age of 25 or over the age of 84 (N = 153). In these groups, few deaths were due to the causes of interest (N = 26 and N = 6, respectively). Thus, deaths among the youngest and oldest males were excluded from analyses, because they are low-risk subgroups for CLD and their inclusion would have likely produced misleading results. Separate analyses for female prisoners were not conducted because small numbers would have produced imprecise, unreliable estimates of trends and crude average annual rates.

CLD-related annual death rates per 100,000 population along with 95% exact Poisson confidence intervals (CIs) (24) were estimated for male decedents aged 25–84 years and stratified by race–ethnicity. The average census of male prisoners aged 25–84 years was used as the denominator for the calculation of crude annual death rates. It was not feasible to obtain the exact entry and exit dates for all prisoners over the study period, which would have allowed for a more accurate calculation of person-time at risk for each year. However, because similar numbers of persons enter and exit the prison population each year (25–29), and because the average census for each year was calculated on the basis of 12 monthly censuses, the average census for a given year should have closely approximated the total person-time for that year (30,31).

Poisson regression on a log normal scale was used to model changes over time in crude annual CLD-related death rates. Regression coefficients were estimated using weighted least squares, in which the weights were equal to the death count for each year or an adjusted count of 0.5, if the observed death count was zero. Trends in crude CLD death rates were described by calculating the average annual percent change (AAPC) with 95% CIs. The AAPC, over any fixed interval, is a weighted average of the slope coefficients of the underlying regression line with the weights equal to the number of years covered by the interval (32). If the 95% CI for the AAPC did not contain zero, this supported the hypothesis that the true AAPC was different from zero at the 0.05 alpha level. The AAPC can be advantageous over the more traditional annual percent change, particularly when data are sparse or highly variable over a specified time interval, because the AAPC does not assume linearity over time and produces more stable estimates with narrower CIs (32).

CLD-related average annual death rates for 5-year periods per 100,000 population along with 95% exact Poisson CIs (24) were estimated for male decedents aged 25–84 years and stratified by race–ethnicity. Because significant differences between crude death rates may exist even when the CIs of the rates overlap (33), we calculated rate differences (RDs) with 95% CIs (34), rate ratios (RRs) with exact 95% CIs, and P values (35) for cases in which 95% CIs overlapped across race–ethnicity categories.

Finally, we calculated frequencies and proportions of CLD-related deaths stratified by the recorded underlying cause of death. Additionally, for deaths with CLD recorded as the underlying cause, we calculated the frequencies and proportions of intervening and contributing causes.

All frequencies and proportions were calculated using SPSS 16.0 (36). Poisson regression models and AAPCs were produced using Joinpoint 3.3, which has been used widely for analysis of cancer mortality rates (32,37,38). The exact 95% CIs for average annual death rates, RDs, and RRs were calculated using StatsDirect (39).

RESULTS

Prisoner census

The average daily census of male prisoners in Texas, aged 25–84 years, more than quadrupled from 1989 to 2003, growing from 27,904 to 117,147 prisoners. The proportion of white prisoners remained fairly steady (~30%); the proportion of black prisoners declined from 45 to 40%; and the proportion of Hispanic prisoners increased monotonically from 21 to 28%. Prisoners aged 25–34 years accounted for 64% of the prison population in 1989 and declined monotonically to 38% in 2003. Conversely, the proportion of prisoners aged 35–54 years increased from 32% of the prison population in 1989 to 56% in 2003, and prisoners aged 55–84 years from 3% in 1989 to 6% in 2003. The proportion of inmates in the two youngest age categories (25–34 and 35–44 years) was slightly higher in Hispanic prisoners (81%) and black prisoners (79%) compared with that in white prisoners (73%) in the 1999–2003 period (data not shown). Thus, over the study period, the size of the prison population grew considerably, and the proportions of older prisoners and Hispanic prisoners increased, while the proportion of black prisoners decreased.

Prisoner CLD-related deaths over time and by race–ethnicity

Over the entire study period, CLD-related deaths accounted for 16% of prisoner deaths (688/4,316). The largest proportion of CLD-related deaths was among Hispanic prisoners (41%), followed by white prisoners (34%) and black prisoners (25%). CLD-related deaths accounted for an increasing proportion of deaths over time, from 10% during 1989–1993 (72/693) to 19% (260/1994) during 1999–2003 (data not shown).

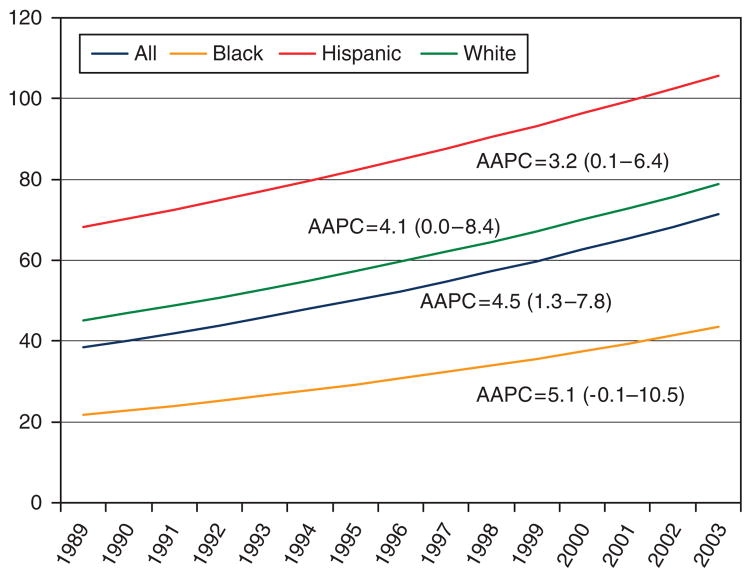

From 1989 to 2003, CLD-related annual death rates increased in the study population overall (Figure 1). The AAPCs indicated an average annual increase of 4.5% in CLD-related death rates in this prisoner population from 1989 to 2003 (Figure 1). Although 95% CIs for the AAPCs were somewhat wide, suggesting a lack of precision, the AAPCs indicated that average annual increases in CLD-related deaths were significant at the 0.05 level for the total prison population and for Hispanic prisoners. Average annual increases in CLD-related death rates were similar across categories of race–ethnicity.

Figure 1.

Trends in crude CLD-related annual death rates per 100,000 population by race–ethnicity among male prisoners, aged 25–84 years, TDCJ, 1989–2003. Trends are described by the AAPCs, which were based on the Poisson-modeled values on a log normal scale and produced using Joinpoint 3.3. (32). AAPC, average annual percentage change; CLD, chronic liver disease/cirrhosis; TDCJ, Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

As shown in Table 1, CLD-related average annual death rates for the 1989–1993 period were higher among Hispanic prisoners compared with black prisoners. Rates were higher among Hispanic and white prisoners compared with black prisoners for the 1994–1998 and 1999–2003 periods. In these later time periods, 95% CIs for crude average annual CLD-related death rates among Hispanic and white prisoners were slightly overlapping, but RDs and RRs indicated that CLD-related death rates were significantly higher among Hispanic prisoners than among white prisoners (1994–1998, RD = 25.5 (5.4–45.6), RR = 1.46 (1.07–2.01), P = 0.014; 1999–2003, RD = 28.3 (8.2–48.4), RR = 1.38 (1.09–1.76), P = 0.006).

Table 1.

Frequency of CLD-relateda deaths and average annual crude death ratesb per 100,000 by race–ethnicity among male prisoners aged 25–84 yearsc, TDCJ, 1989–2003

| Years | Black–African American | Hispanic–Latino | White–Caucasian | All | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths | Rate | 95% CI | Deaths | Rate | 95% CI | Deaths | Rate | 95% CI | Deaths | Rate | 95% CI | |

| 1989–1993 | 19 | 21.2 | 12.7–33.0 | 27 | 63.7 | 42.0–92.7 | 26 | 43.7 | 28.5–64.0 | 72 | 37.5 | 29.3–47.2 |

| 1994–1998 | 58 | 26.7 | 20.3–34.5 | 95 | 80.5 | 65.1–98.4 | 76 | 55.0 | 43.4–68.9 | 229 | 49.2 | 43.0–56.0 |

| 1999–2003 | 98 | 40.6 | 32.9–49.4 | 154 | 102.2 | 86.7–119.6 | 134 | 73.9 | 61.9–87.5 | 387 | 67.2 | 60.7–74.2 |

CI, confidence interval; CLD, chronic liver disease/cirrhosis; TDCJ, Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

CLD was identified by ICD-9 codes 571 and 572, and by ICD-10 codes K70, K72, K74, K75, and K76, including all subordinate codes. Deaths were considered “CLD-related” when CLD was identified as either the underlying cause or an intervening or contributing cause of death in vital statistics data.

CIs are 95% exact Poisson (24). The denominator for the calculation of rates was the average male prisoner census, which represents an average of monthly “snapshot” censuses for males within each stratum of race–ethnicity by 10-year age categories, rounded to the nearest integer.

Only one death event over the study period was of an individual whose racial–ethnic designation was other than black, white, or Hispanic. Analyses were limited to prisoners aged 25–84 years at the time of death because of the small number of prisoner decedents outside this age range.

Prisoner CLD-related deaths by underlying cause of death

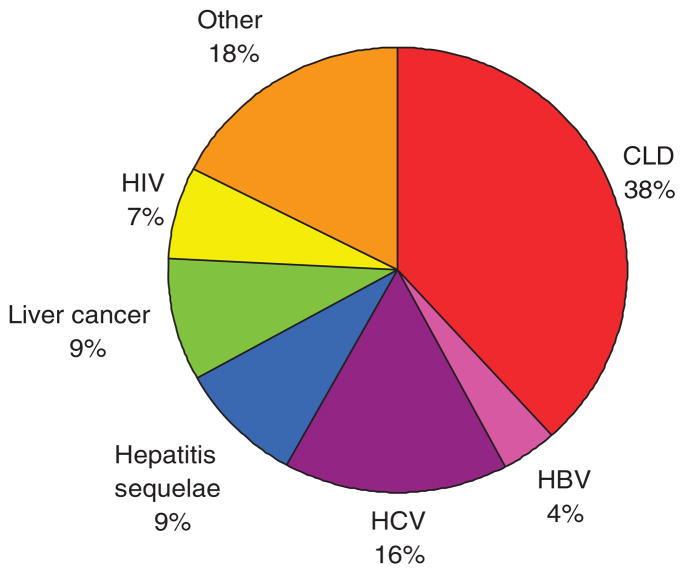

As shown in Figure 2, nearly two-third of CLD-related deaths did not have CLD recorded as the underlying cause. Of these, the underlying causes were recorded as chronic hepatitis or its sequelae (29%), liver cancer (9%), human immunodeficiency virus (7%), or other causes (18%). CLD was identified as an intervening or contributing cause for 93% of HBV deaths (27/29), 83% of HCV deaths (109/131), 45% of liver cancer deaths (61/137), and 6% of human immunodeficiency virus deaths (46/712). Notably, of these deaths for which CLD was identified as the underlying cause, 15% (40/263) had HBV or HCV recorded as an intervening or contributing cause of death. Overall, HBV or HCV was a causal factor in 34% of CLD-related deaths (237/688) (data not shown).

Figure 2.

The underlying causes of CLD-related deaths (N = 688). CLD was identified by ICD-9 codes 571 and 572, and by ICD-10 codes K70, K72, K74, K75, and K76, including all subordinate codes. Deaths were considered “CLD-related” when CLD was identified either as the underlying cause or as an intervening or contributing cause of death in vital statistics data. The ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for other underlying causes shown were as follows: HCV = 070.4, 70.5, B17.1, B18.2; CLD = 571.0–571.3, 571.8, 571.9, K70.09, K74.6; PLC = 155.0, 155.2, C22.0, C22.2, C22.9; HBV = 070.2–070.3, B16.0–16.9, B18.0–B18.1; HIV = 042–044, B20–B23. Total >100% due to rounding. CLD, chronic liver disease/cirrhosis; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PLC, primary liver cancer.

DISCUSSION

These data indicate a growing burden of CLD-related deaths among male prisoners in Texas. CLD-related crude annual death rates increased in this prison population by an average of 4.5% annually over the study period. Although increases in CLD-related death rates were statistically similar across categories of race–ethnicity, CLD-related death rates were higher among Hispanic prisoners than among black prisoners in each 5-year period and were higher than white prisoners in the later time periods, 1994–1998 and 1999–2003.

Elevated CLD-related death rates among male prisoners may be explained largely by their higher prevalence of HBV and HCV infections and history of alcohol use (7–15). Earlier studies have shown a high prevalence of HCV in this particular prison population (9), and HBV or HCV was a causal factor in 34% of CLD-related deaths during the study period. A history of high-volume, extended use of alcohol among prisoners may be particularly important in this population, because up to 30% of newly admitted male inmates in Texas meet the diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence (15).

Elevated CLD-related mortality among Hispanic male prisoners is more difficult to explain. The prevalence of HBV among male Hispanic prisoners has been lower than among other racial–ethnic groups in some studies, but higher in other studies (11–13,40,41). In most prison studies, HCV prevalence among male Hispanic prisoners has been higher than among black prisoners, but slightly lower or similar to that of white prisoners (9–13,40). This variation across prison studies may be due, in part, to regional differences in the distribution of subgroups within Hispanic populations. Hispanic subgroups are known to vary considerably in terms of the distribution of CLD risk factors and general health status. Overall, however, Hispanics appear to initiate HCV risk behaviors at younger ages and, as a result, become HCV-infected earlier (42–44). Studies in non-incarcerated populations have also shown more frequent or heavier-volume alcohol use among Hispanic males, particularly Mexican-American males, compared with white or black males (5,45–47). Additionally, it has been suggested that Mexican-American males may be at an increased risk of developing CLD because of a genetic predisposition, gene–environment interactions, or interaction of primary risk factors with lesser risk factors, such as obesity or diabetes (5,48–50). In Texas, Hispanic prisoners are predominantly Mexican-American, so all of these factors may have contributed to an elevated risk of CLD-related mortality among male Hispanic prisoners observed in our study.

Our findings must be interpreted in light of common problems with mortality data based on death certificates, particularly non-specificity of codes and under-reporting or over-reporting of conditions on the death certificate by certifying physicians (51,52). The extent to which CLD-deaths were alcohol related could not be examined, because this was not specified in the multiple-cause-of-death data for a non-trivial number of deaths. This is recognized as a major limitation of this study, given the high prevalence of a history of alcohol abuse in prison populations (15) and the etiologic importance of this risk factor for CLD (2,5).

Additionally, increased awareness of the problem of HCV among US prisoners prompted changes in the TDCJ screening policies in 1998, which resulted in increased HCV screening at that time, and may have also resulted in increased identification or selection of HCV as a cause of death for prisoners. Thus, apparent increases in HCV-related prisoner mortality around this time, and CLD-related prisoner mortality, may reflect some combination of changes in screening and/or certification practices along with real trends. However, HCV screening protocols have remained consistent since 1998, so one would not expect changes in screening procedures to account entirely for the sizable increases in HCV-related mortality since that time.

Other study limitations should be noted as well. The average census of male prisoners aged 25–84 years for each year was used as the denominator for the calculation of crude annual death rates. More accurate rates would have been obtained if person-time at risk for each year had been calculated and used as the denominator for the calculation of annual death rates. However, it was not feasible to obtain the data needed for such calculations, and for previously stated reasons, the average census of male prisoners for a given year should have closely approximated person-time for that year. CLD-related average annual death rates by categories of race–ethnicity were not age-adjusted, because small numbers of death events by race–ethnicity and age categories would have produced unreliable age-adjusted rates. However, changes over time in the age distribution of the population were minimal, and differences in the age distribution across race–ethnicity categories were modest. Multiple-cause-of-death data from males in Texas or in the US general population were not obtained for this study, which precluded explicit comparison of CLD-related death rates in the prison population with these referent populations. Owing to the heterogeneity of prison populations with respect to prevalence of CLD risk factors (9–15), our findings may not generalize to other male state prison populations.

Despite these limitations, our study is the first to use existing multiple-cause-of-death data to assess CLD-related mortality among prisoners. Our use of multiple-cause-of-death data to define CLD-related mortality represents an improvement over earlier studies. Studies that rely solely on the underlying cause of death may underestimate CLD-related deaths by defining them according to the CLD-specific codes, or may overestimate CLD-related deaths by including numerous codes that represent overly broad disease categories (e.g., all viral hepatitis).

More importantly, our study represents an important step toward assessing the burden of CLD-related conditions on a large correctional healthcare system. Of course, any study of CLD-related mortality among male prisoners likely captures only the “tip of the iceberg” of the total burden of CLD-related disease in a large prison system. It is probable that far fewer prisoners die from CLD-related conditions when in custody than are treated for these conditions and ultimately released to their communities. In a recent study of Texas prisoners incarcerated between 2003 and 2006, Baillargeon et al. (17) found that the number of inmates diagnosed with end-stage liver disease (N = 484) was approximately two times greater than the number of patients who died of end-stage liver disease (N = 213) when in prison. Moreover, from 1994 to 2003, an average of 63 ill prisoners was released annually on “special needs parole” or “ medically related intensive supervision,” but the proportion of these releases that was CLD-related could not be ascertained.

With these considerations in mind, if the CLD-related mortality data presented here are viewed as reflective of the extent of severe morbidity in the prison population and as indicative of future trends, then these data suggest that the burden of CLD-related conditions and associated costs in prisons are substantial and can be expected to increase. Although annual costs per case of asymptomatic chronic hepatitis infection or mild cirrhosis have been estimated at $145, annual per case treatment costs for compensated cirrhosis have been estimated at $1,053 ($US, 2007) (53). Costs of severe cirrhosis complications, such as ascites, variceal hemorrhage, or hepatic encephalopathy were estimated at $3,765, $20,822, and $13,365 per case, respectively, for the first year alone ($US, 2001) (54), and annual per case costs of hepatocellular carcinoma have been estimated at $42,255 per case ($US, 2007) (53).

Targeted prevention, screening, and treatment for CLD risk factors have been recommended for prison populations (5) and would likely avert or lessen the costs of CLD-related morbidity and mortality (53–56). However, prison healthcare systems vary widely with respect to CLD-related policies and practices, such as substance and alcohol abuse treatment, behavioral risk reduction education, HBV vaccination, HBV and HCV screening, and early detection and treatment of liver disease (57,58). In determining prison healthcare priorities and policy directions, the costs of preventive and therapeutic services for CLD-related conditions must be considered alongside the costs associated with other causes of morbidity and mortality in the prison population. Because state prison healthcare systems are typically under-funded, other public funding may be required to provide preventive and therapeutic services that meet community standards in the future. As prison populations continue to age and increase in size (59,60), and as the number of prisoners released annually increases (14), the growing role of prison healthcare systems in preventing and treating CLD-related conditions must be addressed.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

✓ Alcohol abuse and chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections are the major etiologic factors for chronic liver disease/cirrhosis (CLD) in the United States.

✓ These CLD risk factors are highly prevalent in the US adult incarcerated populations, but CLD-related mortality data from these populations are lacking.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

✓ Among male Texas prisoners from 1989 to 2003, CLD-related deaths accounted for a substantial proportion (16%) of total deaths.

✓ CLD-related crude average annual death rates were high and increased over the 15-year study period by an average of 4.5% annually, with similar rate increases across categories of race–ethnicity.

✓ CLD-related average annual death rates were higher among Hispanic prisoners than among black prisoners in each 5-year period, and were higher than those for white prisoners in the later time periods, 1994–1998 and 1999–2003.

✓ HBV or HCV was identified as a causal factor in more than a third (34%) of CLD-related deaths.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Amy Jo Harzke was funded by a Pre-doctoral Cancer Prevention and Control Fellowship during the early phases of this research (NIH/NCI R25 CA 57712 to Patricia Dolan Mullen, University of Texas, School of Public Health).

Dr. David Ramsey at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Houston provided technical assistance in data linkage. Leonard Pechacek, from Correctional Managed Care at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, provided editorial assistance. The research described herein was coordinated in part by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ), research agreement no. 470-RM05. The contents of this paper reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the TDCJ.

Footnotes

Guarantor of the article: Amy Jo Harzke, MDiv, MPH, DrPH.

Specific author contributions: Conceiving this study, leading the analyses, interpretation of findings, and writing of this paper: Amy Jo Harzke; assisting with study design, interpretation of findings, and critical revisions of this paper: Jacques Baillargeon; providing information specific to healthcare delivery and policies in the Texas prison system and contributing to critical revisions of this paper: David Paar, John Pulvino, and Owen Murray. All authors made substantive contributions to this paper. All authors have approved the final draft of this paper.

Potential competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu JQ, et al. Deaths: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008;56:1–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh GK, Hoyert DL. Social epidemiology of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis mortality in the United States, 1935–1997: trends and differentials by ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and alcohol consumption. Hum Biol. 2000;72:801–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed October 2008.];Disease Burden from Viral Hepatitis A, B, and C in the United States. 2002 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Statistics.htm#section3.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47 (RR-19):1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flores YN, Yee HF, Leng M, et al. Risk factors for chronic liver disease in blacks, Mexican-Americans, and whites in the United States: results from NHANES IV, 1999–2004. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2231–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstrong GL, Alter MJ, McQuillan GM, et al. The past incidence of hepatitis C virus infection: implications for the future burden of chronic liver disease in the United States. Hepatology. 2000;31:777–82. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:705–14. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solomon L, Flynn C, Muck K, et al. Prevalence of HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C among entrants to Maryland correctional facilities. J Urban Health. 2004;81:25–37. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baillargeon J, Wu H, Kelley MF, et al. Hepatitis C seroprevalence among newly incarcerated inmates in the Texas correctional system. Public Health. 2003;17:43–8. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(02)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox RK, Currie SL, Evans J, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection among prisoners in the California state correctional system. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:177–86. doi: 10.1086/430913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruiz JD, Mikanda J. Seroprevalence of HIV, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, and Risk Behaviors Among Inmates Entering the California Correctional System. California Department of Health Services; 1996. [Accessed October 2008.]. Available at: http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/AIDS/Documents/RPT1996SeroHIVHepBHepCRiskAmongInmates.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruiz JD, Chang JS, Bernstein K, et al. Prevalence of HIV Infection, Sexually Transmitted Diseases, Hepatitis, and Risk Behaviors Among Inmates Entering Prison at the California Department of Corrections, 1999. California Department of Health Services; 2001. [Accessed October 2008.]. Available at: http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/AIDS/Documents/RPT2001PrevofHIVInfectSTDCorrections1999.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macalino GE, Vlahov D, Sandford-Colby S, et al. Prevalence and incidence of HIV, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus infections among males in Rhode Island prisons. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1218–23. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammett TM, Harmon MP, Rhodes W. The burden of infectious disease among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1789–94. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fazel S, Bains P, Doll H. Substance abuse and dependence in prisoners: a systematic review. Addiction. 2006;101:181–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baillargeon J, Snyder N, Paar D, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma prevalence and mortality in a male state prison population. Public Health Rep. 2009;124:120–6. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baillargeon J, Soloway RD, Paar D, et al. End-stage liver disease in a state prison population. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:808–13. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.One in 100: Behind Bars in America 2008. Pew Center on the States. Washington, DC: 2008. [Accessed October 2008.]. Available at: http://www.pewcenteronthestates.org/report_detail.aspx?id=35904. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Center for Health Statistics/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Instructions for Classifying the Underlying Cause-of-death. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Hyattsville, MD: 2008. [Accessed October 2008.]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/2a2008Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shojania KG, Burton EC, McDonald KM, et al. Changes in rates of autopsy-detected diagnostic errors over time: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289:2849–56. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.21.2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mortality data from the National Vital Statistics system. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1989;38:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vong S, Bell BP. Chronic liver disease mortality in the United States, 1990–1998. Hepatology. 2004;39:476–83. doi: 10.1002/hep.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas AR, Zaman A, Bell BP. Deaths from chronic liver disease and viral hepatitis, Multnomah County, Oregon, 2000. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:859–62. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31802df0fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ulm K. A simple method to calculate the confidence interval of a standardized mortality ratio. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131:373–5. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Executive Services, Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) Texas Department of Criminal Justice Statistical Report Fiscal Year 2003. TDCJ; Austin, TX: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Executive Services, Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Texas Department of Criminal Justice Statistical Report Fiscal Year 2004. TDCJ: Austin, TX; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Executive Services, Author: Texas Department of Criminal Justice. [Accessed December 2008.];Texas Department of Criminal Justice Statistical Report Fiscal Year. 2005 Available at: http://www.tdcj.state.tx.us/publications/publications-home.htm.

- 28.Executive Services, Texas Department of Criminal Justice. [Accessed December 2008.];Texas Department of Criminal Justice Statistical Report Fiscal Year. 2006 Available at: http://www.tdcj.state.tx.us/publications/publications-home.htm.

- 29.Executive Services, Texas Department of Criminal Justice. [Accessed December 2008.];Texas Department of Criminal Justice Statistical Report Fiscal Year. 2007 Available at: http://www.tdcj.state.tx.us/publications/publications-home.htm.

- 30.Elandt-Johnson RC. Definition of rates: some remarks on their use and misuse. Am J Epidemiol. 1975;102:267–71. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenland S, Rothman KJ, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. 3. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Cancer Institute. Statistical Research and Applications, Joinpoint Regression Program. [Accessed October 2008.];Average Annual Percent Change. Available at: http://srab.cancer.gov/joinpoint/aapc.html.

- 33.Esteve J, Benhamou E, Raymond L. Descriptive Epidemiology. IV. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon, France: 1994. Statistical Methods in Cancer Research; pp. 1–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sahai H, Khurshid A. Statistics in Epidemiology: Methods, Techniques, and Applications. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin DO, Austin H. Exact estimates for a rate ratio. Epidemiology. 1996;7:29–33. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Statistical Software. SPSS for Windows, Release 16.0.1. SPSS, Inc; Chicago, IL: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh GK, Miller BA, Hankey BF. Changing area socioeconomic patterns in U.S cancer mortality, 1950–1998. Part II—Lung and colorectal cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:916–25. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.12.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weir HK, Thun MJ, Hankey BF, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2000, featuring the uses of surveillance data for cancer prevention and control. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1276–99. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Statistical Software. StatsDirect Statistical Software, Version 2.7.2. Stats-Direct Ltd; Cheshire, WA, UK: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baillargeon J, Black SA, Leach CT, et al. The infectious disease profile of Texas prison inmates. Prev Med. 2004;38:607–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khan AJ, Simard EP, Bower WA, et al. Ongoing transmission of hepatitis B virus infection among inmates at a state correctional facility. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1793–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steuve A, O’Donnell LN. Early alcohol initiation and subsequent sexual and alcohol risk behaviors among urban youths. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:87–93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.026567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Delva J, Wallace JM, Jr, O’Malley PM, et al. The epidemiology of alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine use among Mexican American, Puerto Rican, Cuban American, and other Latin American eighth-grade students in the United States: 1991–2002. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:696–702. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.037051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheung RC, Currie S, Shen H, et al. Chronic hepatitis C in Latinos: natural history, treatment eligibility, acceptance, and outcomes. Am J Gasteroenterol. 2005;100:2186–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caetano R. Alcohol use among Hispanic groups in the United States. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1988;14:293–308. doi: 10.3109/00952998809001552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Randolph WM, Stroup-Benham C, Black SA, et al. Alcohol use among Cuban-Americans, Mexican-Americans, and Puerto Ricans. Alcohol Health Res World. 1998;22:265–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nielsen AL. Examining drinking patterns and problems among Hispanic groups: results from a national survey. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:301–10. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meltzer AA, Everhart JE. Association between diabetes and elevated serum alanine aminotransferase activity among Mexican Americans. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;46:565–71. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arya R, Duggirala R, Almasy L, et al. Linkage of high-density lipoprotein- cholesterol concentrations to a locus on chromosom 9p in Mexican Americans. Nat Genet. 2002;30:102–5. doi: 10.1038/ng810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clark JM, Brancati FL, Diehl AM. The prevalence and etiology of elevated aminotransferase levels in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:960–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Israel RA, Rosenberg HM, Curtin IR. Analytical potential for multiple cause-of-death data. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124:161–79. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenberg HM. Improving cause-of-death statistics. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:563–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.5.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan JA, Joseph TA, Saab S. Treating hepatitis C in the prison population is cost-saving. Hepatology. 2008;48:1387–95. doi: 10.1002/hep.22509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salomon JA, Weinstein MC, Hammitt JK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treatment for chronic hepatitis C infection in an evolving patient population. JAMA. 2003;290:228–37. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weinbaum C, Lyerla R, Margolis HS Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of infections with hepatitis viruses in correctional settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52 (RR-1):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Quinn PG, Johnston DE. Detection of chronic liver disease: costs and benefits. Gastroenterologist. 1997;5:58–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beck AJ, Maruschak LM. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report (NCJ 199173C) US Department of Justice; Washington, DC: 2004. Hepatitis Testing and Treatment in State Prisons. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mumola CJ. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report (NCJ 172871) US Department of Justice; Washington, DC: 1999. Substance Abuse and Treatment, State and Federal Prisoners, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mitka M. Aging prisoners stressing health care system. JAMA. 2004;292:423–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harrison PM, Karberg JC. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin (NCJ 203947) US Department of Justice; Washington, DC: 2004. Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear 2003. [Google Scholar]