Abstract

Species within the class Raphidophyceae were associated with fish kill events in Japanese, European, Canadian, and U.S. coastal waters. Fish mortality was attributable to gill damage with exposure to reactive oxygen species (peroxide, superoxide, and hydroxide radicals), neurotoxins, physical clogging, and hemolytic substances. Morphological identification of these organisms in environmental water samples is difficult, particularly when fixatives are used. Because of this difficulty and the continued global emergence of these species in coastal estuarine waters, we initiated the development and validation of a suite of real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays. Sequencing was used to generate complete data sets for nuclear encoded small-subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA; 18S); internal transcribed spacers 1 and 2, 5.8S; and plastid encoded SSU rRNA (16S) for confirmed raphidophyte cultures from various geographic locations. Sequences for several Chattonella species (C. antiqua, C. marina, C. ovata, C. subsalsa, and C. verruculosa), Heterosigma akashiwo, and Fibrocapsa japonica were generated and used to design rapid and specific PCR assays for several species including C. verruculosa Hara et Chihara, C. subsalsa Biecheler, the complex comprised of C. marina Hara et Chihara, C. antiqua Ono and C. ovata, H. akashiwo Ono, and F. japonica Toriumi et Takano using appropriate loci. With this comprehensive data set, we were also able to perform phylogenetic analyses to determine the relationship between these species.

Key index words: Chattonella, Fibrocapsa, Heterosigma, PCR, Raphidophyceae, Taqman

Worldwide distribution of species belonging to the class Raphidophyceae is well documented (e.g. Tomas 1980, 1998, Hosaka et al. 1991, Honjo 1992, Rhodes et al. 1993, Vrieling et al. 1995, Smayda 1998, Bourdelais et al. 2002), and blooms of these species were associated with kills of captive and wild fish populations. Over 14 million yellowtail (Seriola quinqueradiata) perished during a bloom of Chattonella antiqua in Japan, resulting in a loss of 71 billion yen in 1972 (Okaichi 1987; original morphological description of C. antiqua in Ono and Takano 1980). In spring 1996, 1700 tons of bluefin tuna (Tunnus maccoyii) valued at US$40 million were destroyed in South Australia by a bloom of C. marina (Hallegraeff et al. 1998; original morphological description of C. marina in Hara et al. 1994). Hard et al. (2000) observed selective mortality in a captive population of chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) in response to a natural bloom of Heterosigma akashiwo (original morphological description of H. akashiwo in Hara and Chihara 1987) in Puget Sound, Washington, during 1997. Blooms of C. aff. verruculosa killed over 350 tons of cultured salmon in western Norway in 1998 (Backe-Hansen et al. 2001), while a mixed bloom of H. akashiwo and C. marina was responsible for killing approximately 1100 tons of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) during 2001 (Lars-Johan et al. 2002). Since the mid-1980s, deaths of farmed salmon attributed to blooms of Raphidophytes in the Pacific northwest resulted in economic losses of approximately US$30 million (Rensel et al. 1989).

Although the exact killing mechanisms are some-what unclear, there are several mechanisms thought to lead to gill damage and fish deaths. For example, several species have been documented to produce brevetoxin or brevetoxin-like compounds. Among these are H. akashiwo (Black et al. 1991, Khan et al. 1997), C. marina (Onoue and Nozawa 1989, Khan et al. 1996a), C. antiqua (Onoue and Nozawa 1989, Khan et al. 1996a), an C. verruculosa (Yamamoto and Tanaka 1990, Baba et al. 1995, Tomas unpublished data; and original morphological description of C. verruculosa in Hara et al. 1994). The toxicity of Fibrocapsa japonica has also been explored (Khan et al. 1996b, Bridgers et al. 2004, Fu et al. 2004; original morphological description of F. japonica in Toriumi and Takano 1973). Fish exposed to these toxins had decreased heart rates, resulting in impaired oxygen flow to the gills and, in some instances, mortality. The production of reactive oxygen species such as superoxide, hydroxide, and hydrogen peroxide radicals along with production of hemolytic substances by some species of raphidophytes like H. akashiwo (Ahmed et al. 1995, Yang et al. 1995), F. japonica (Oda et al. 1997), and C. antiqua (Schimada et al. 1983, Tanaka et al. 1994) presumably cause gill damage leading to fish mortality. Toxic polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are yet another active element suggested for raphidophytes (Marshall et al. 2004) and, in combination with reactive oxygen species and neurotoxins, can present a toxin cocktail resulting in the lethal effects observed during some raphidophyte blooms.

To better track and predict the potential for negative effects of raphidophyte species on fish, human health, and local economies, their accurate and rapid identification in environmental monitoring programs is essential. Traditional identification by conventional microscopy is tedious and particularly difficult because these organisms do not preserve well (Heywood 1978, Tomas 1997). These difficulties are compounded when attempting to assess raphidophyte populations within a heterogeneous environmental sample. Tyrrell et al. (2001) used fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) probes for detecting H. akashiwo, but this method proved difficult due to cell disruption and morphology distortion resulting from exposure to fixatives. Small cells were also a problem in that they could easily be confused with small autofluorescent particles inherent in environmental samples. A sandwich hybridization assay (SHA; Scholin et al. 1997, Tyrrell et al. 2001) with species-specific probes targeted to the LSU region of H. akashiwo and F. japonica was developed. Modifying the probe sequences even slightly in an SHA can affect the intensity and specificity of the signal (Fuchs et al. 1988, Tyrrell et al. 2001).

Progress was made in utilizing other molecular methods, which are faster and more cost efficient than traditional microscopy to identify raphidophyte species. Murayama-Kayano et al. (1998) used the random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) technique to determine genetic variability among Chattonella species and strains. This technique is beneficial when characterizing cultures and assessing strain differences; however, it becomes challenging when applied to complex environmental samples. Connell (2002) recently developed several PCR primers targeted to the intertranscribed spacer (ITS) regions of C. antiqua, C. subsalsa (original morphological description of C. subsalsa in Biecheler 1936), F. japonica, H. akashiwo, and O. luteus. These advances in molecular techniques circumvent the problems associated with cell fixation and traditional microscopic methods.

The present work presents the development and validation of real-time PCR assays based on Taqman methodology (Holland et al. 1991, Wittwer et al. 1997) for C. verruculosa; the C. marina, C. antiqua, C. ovata complex (original morphological description of C. ovata in Hara et al. 1994); C. subsalsa; H. akashiwo; and F. japonica. This research not only provides assays for detecting these species in cultures and environmental samples, but it also greatly expands raphidophyte sequence data available to the research community. In particular, this is the first time that sequence data have been presented for C. verruculosa, which is now believed to belong to the family Dictyochophyceae (Fukaya et al. 2002, Bowers et al. 2004, Edvardsen et al. submitted). Recently, a closely related flagellate isolated from the Skagerrak (C. aff. verruculosa) was fully characterized, and a new name has been proposed (Verrucophora verruculosa var. farcima gen. et var. nov.; Edvardsen et al. submitted). Phylogenetic analysis of this organism places it close to C. verruculosa in the Dictyochophyte clade (Edvardsen et al., submitted).

We also explored the previous observations that C. marina, C. antiqua and C. ovata are genetically indistinguishable, although they can be separated based on classical morphology. Sako et al. (2000) proposed that these three species were genetically identical based on nuclear encoded SSU rRNA as well as nuclear encoded large subunit ribosomal RNA (LSU rRNA; 28S) sequences data, while Connell (2000) concluded that C. antiqua and C. marina were identical in the highly variable internal transcribed spacer (ITS1 and 2; 5.8S) locus using one culture of each species. We derived sequence data from three loci utilizing nine different cultures to validate these findings. Connell (2000) also observed that the ITS locus for H. akashiwo was surprisingly conserved among isolates from both the Atlantic and Pacific basins. We also observed this trend for nuclear 18S as well as plastid 16S sequence data from several H. akashiwo cultures, including some of the isolates used in the Connell study. Furthermore, we observed the same phenomenon when we sequenced and compared the three target loci from eight cultures of C. subsalsa isolated from various geographic locations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultures and environmental samples

The raphidophyte cultures used for this study are listed in Table 1. Cultures were obtained from CMSTAC (Center for Marine Science Toxic Algal Collection, University of North Carolina), CCMP (Provasoli–Guillard National Center for Culture of Marine Phytoplankton), CAAE (Center for Applied Aquatic Ecology, North Carolina State University), SCAEL (South Carolina Algal Ecology Laboratories), KAGAWA (Akashiwo Research Institute of Kagawa Prefacture), CAW (The Cawthron Microalgae Culture Collection), and NIES (National Institute for Environmental Studies).

Table 1.

Panel of characterized raphidophyte and dictyochophyte cultures that were sequenced and used for validating real-time PCR assays.

| Real-time PCR assays |

GenBank accession numbers |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species name, strain designation, and location | Isolator (date) | Chattonella verruculosa | C. marina/antiqua/ovata | C. subsalsa | Fibrocapsa japonica | Heterosigma akashiwo | 18S | ITS | 16S |

| Raphidophyceae | |||||||||

| C. verruculosa NIES 670 Harima Nada, Seto Island Sea, Japan | S. Yoshimatsu (1987) | pos. | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | AY788948 | N/D | AY864040 |

| C. verruculosa CAWR21 Kaikoura, New Zealand | L. Rhodes (2003) | pos. | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | AY788947 | N/D | AY864049 |

| C. antiqua CCMP 2050b Harima Nada, Seto Island Sea, Japan | M. Watanabe (1978) | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | neg. | AY788921 | AY858856 | AY864025 |

| C. antiqua CCMP 2052 Mikawa Bay, Japan | S. Toriumi | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | neg. | AY788920 | AY858857 | AY929294 |

| — | |||||||||

| C. antiqua CMSTAC AI-3 (KAGAWAa 59-2) Naoshima Island, Japan | S. Yoshimatsu (1982) | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | neg. | AY788922 | AY858858 | AY864035 |

| C. marina CCMP 2049 (NIES-121) Kagoshima Bay, Japan | T. Aramaki (1982) | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | neg. | AY788928 | AY865604 | AY864026 |

| C. marina CMSTAC AI-6 (KAGAWA 46-7) Harima Nada, Seto Island Sea, Japan | S. Yoshimatsu (1981) | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | neg. | AY788925 | AY858860 | AY864036 |

| C. marina CMSTAC MD 7 St. Martin River, Maryland, USA | C. Tomas (2002) | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | neg. | AY788927 | AY858861 | AY864045 |

| C. marina CMSTAC NR 5 New River, North Carolina, USA | C. Tomas (2000) | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | neg. | AY788926 | AY858862 | AY864027 |

| C. cf. ovata CCMP 216b Kagosima, Japan | T. Okaichi | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | neg. | AY788923 | AY858872 | AY864037 |

| — | |||||||||

| C. ovata NIES 603 Harima Nada, Seto Island Sea, Japan | I. Imai (1984) | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | neg. | AY788924 | AY858863 | AY929295 |

| C. sp. CCMP 218 Harima Nada, Seto Island Sea, Japan | T. Okaichi | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | neg. | AY788930 | AY858865 | AY864046 |

| — | |||||||||

| C. subsalsa CCMP 217 Tampa Bay, Florida, USA | W. Gardner (1982) | neg. | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | U41649 (Potter) | AF210739 (Tyrrell) | AY864038 |

| C. subsalsa CAAE 1662c South Carolina, USA | C. Zhang (2001) | neg. | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | N/D | N/D | N/D |

| C. subsalsa CAAE 1664c North Carolina, USA | C. Zhang (1999) | neg. | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | N/D | N/D | N/D |

| C. subsalsa CMSTAC DE 9 Rehoboth Bay, Delaware, USA | C. Tomas (1997) | neg. | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | AY788938 | AY858867 | AY864047 |

| C. subsalsa CMSTAC SS 4 Salton Sea, California, USA | C. Tomas (1996) | neg. | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | AY788943 | AY858866 | AY864028 |

| C. subsalsa CMSTAC TX 12 Corpus Christi Bay, Texas, USA | C. Tomas (1997) | neg. | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | AY788939 | AY858871 | AY864023 |

| C. subsalsa CMSTAC J04 Seto Island Sea, Japan | Yoshimatsu (1989) | neg. | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | AY788944 | AY858864 | AY864029 |

| C. subsalsa CMSTAC SH-1 Singapore Harbor, Singapore | M. Holmes (1996) | neg. | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | AY788942 | AY858870 | AY864030 |

| C. subsalsa CMSTAC NR 22 New River, North Carolina, USA | C. Tomas (2000) | neg. | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | AY788940 | AY858868 | AY864039 |

| C. subsalsa CMSTAC OL 4 Oristano Lagoon, Sardinia, Italy | C. Tomas (2003) | neg. | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | AY788941 | AY858869 | AY864048 |

| H. akashiwo CCMP 1596 Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, USA | P. Hargraves (1991) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | pos. | AY788932 | AF128237 (Connell) | AY864033 |

| H. akashiwo CCMP 1870 Long Beach, California, USA | R. Anderson (1998) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | pos. | AY788936 | AF157383 (Connell) | AY864042 |

| H. akashiwo CCMP 1912 Kalaloch, Washington, USA | R. Horner (1996) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | pos. | AY788934 | AY858875 | AY864034 |

| H. akashiwo CCMP 302 Milford Sound, New Zealand | F. Chang (1984) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | pos. | AY788935 | AY858876 | AY864024 |

| H. akashiwo CCMP 452 Long Island Sound, New York, USA | R. Conover (1952) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | pos. | U41650 (Potter) | AF096283 (Connell) | AY864041 |

| H. akashiwo CAAE 1665c North Carolina, USA | C. Zhang (2000) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | pos. | N/D | N/D | N/D |

| H. akashiwo CAAE 1660c Delaware, USA | C. Zhang (2000) | N/T | N/T | neg. | neg. | pos. | N/D | N/D | N/D |

| H. akashiwo SCAEL 2B3c South Carolina, USA | J. Wolny (2001) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | pos. | N/D | N/D | N/D |

| H. akashiwo SCAEL 2B2c South Carolina, USA | J. Wolny (2001) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | pos. | N/D | N/D | N/D |

| H. akashiwo CAAE 1650c Canada | C. Zhang (2002) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | pos. | N/D | N/D | N/D |

| H. akashiwo CAAE 1652c NIES 6 Japan | C. Zhang (2002) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | pos. | N/D | N/D | N/D |

| H. akashiwo CAAE 1659c Delaware, USA | C. Zhang (2000) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | pos. | N/D | N/D | N/D |

| H. akashiwo CAAE 1663c South Carolina, USA | C. Zhang (2001) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | pos. | N/D | N/D | N/D |

| H. akashiwo CCMP 1680 Sandy Hook Bay, New Jersey USA | J. Mahoney (1963) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | pos. | AY788933 | AY858874 | AY864032 |

| F. japonica CCMP 1661 Port Phillip Bay, Melbourne Australia | O. Moestrup (1988) | neg. | neg. | neg. | pos. | neg. | AY788931 | N/D | DQ453516 |

| F. japonica CAAE 1661c South Carolina, USA | C. Zhang (2001) | neg. | neg. | neg. | pos. | neg. | N/D | N/D | N/D |

| Dictyochophyceae | |||||||||

| Rhizochromulina sp. CCMP 237 Florida Keys, Florida USA | E. Polk (1984) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | U14388 (Saunders) | N/D | AY929297 |

| Pseudopedinella elastica CCMP 716 Gulf of Maine, Maine USA | R. Selvin (1988) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | U14387 (Saunders) | N/D | AY939780 |

| Apedinella radians CCMP 1767 Musholm Bugt, Denmark | O. Moestrup (1983) | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | N/D | N/D | AY929296 |

GenBank accession numbers listed were deposited as a result of this study, except for those listed with a different author.

KAGAWA, Akashiwo Research Institute of Kagawa Prefacture; CAW, The Cawthron Microalgae Culture Collection; CCMP, Provasoli-Guillard National Center for Culture of Marine Phytoplankton; CMSTAC, Center for Marine Science Toxic Algal Collection University of North Carolina; NIES, National Institute for Environmental Studies; CAAE, Center for Applied Aquatic Ecology; and SCAEL, South Carolina Algal Ecology Laboratories.

Culture is no longer available from CCMP.

Utilized for validating real-time PCR assays only.

N/D, sequence data not determined; N/T, not tested; neg., negative; pos., positive.

All cultures from the CMSTAC were established as single cell pipette isolations from natural bloom samples. C. antiqua was the only culture maintained at CMSTAC that was originally obtained from the Kagawa Culture collection. All cultures were maintained in seawater-enriched media either as Guillard’s F/2 medium (Guillard and Ryther 1962) modified by the elimination of silica and Tris stock solutions or in Erdschriber’s medium as specified by the media recipes of the CCMP. All cultures were kept at 24° C, with 80–100 μmol photons · m−2 · s−1 of cool-white fluorescent light and a 12:12 light : dark (LD) cycle. Raphidophyte cells from each culture were examined using a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 microscope (Carl Zeiss Company, Thornwood, NY, USA) equipped for differential interference contrast and epifluorescence. Morphological observations were made via brightfield/DIC microscopy.

Environmental samples used for validation of assays were obtained from Maryland Department of Natural Resources (MD-DNR) and Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DE-DNREC) as part of their routine monitoring programs during 2005. Microscope counts were performed for raphidophyte species on all samples by trained personnel at the respective agencies.

DNA extraction

Extractions of DNA from cultures were conducted using either a cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) buffer DNA isolation technique (Schaefer 1997) or a Puregene® DNA Isolation Kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). DNA extractions from environmental samples were performed using the Puregene® kit only. When using the Puregene® kit, 50mL of culture was centrifuged at 4000g, and the supernatant was decanted. The pellet was resuspended in 300 μL of cell lysis buffer supplied with the kit, and the manufacturer’s protocol was followed for the remainder of the extraction.

PCR

Table 2 lists all primers used in various combinations to generate overlapping sequence data for nuclear encoded 18S, ITS1-5.8S-ITS2, and partial plastid encoded 16S from raphidophyte cultures (all primers ordered from Qiagen/Operon, Alameda, CA, USA). For each PCR, the 50 μL reaction contained 1.5U of MegaFrag™ Taq polymerase, which is a high fidelity proofreading enzyme (Denville Scientific, Metuchen, NJ, USA); 10 × PCR buffer and 4mM MgCl2 supplied with Taq polymerase; 2mM each dNTP (Invitrogen, Alameda, CA, USA); 0.25mg · mL−1 bovine serum albumin (Idaho Technology, Idaho Falls, ID, USA); 0.8 μM each primer (Qiagen/Operon); 1–5 μL DNA template and molecular biology grade water to a final volume of 50 μL. Cycling was performed on either the Perkin Elmer 9600 (Wellesley, MA, USA) or the DNA Engine Dyad Peltier Thermocycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) as follows: initial denaturation at 94° C for 2min, followed by 45 cycles of 94° C for 30 s (10 s on Dyad), annealing temperature ranging from 55° C to 60° C (based on primer pair used) for 30 s, 68° C for 40–90 s (depending on amplicon size), and a final extension at 68° C for 10 min (6min 20 s for Dyad). The PCR products were examined on a 1% ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel, and bands were extracted from the gel following the procedure supplied with the MinElute kit (Qiagen).

Table 2.

Primers used to generate and sequence overlapping reads for target loci (18S; ITS1-5.8S-ITS2; 16S).

| Sequence 5′–3′ | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|

| 18S primersa | ||

| ChattR | GCTGACGGAGTCGTTGAG | Group (Raphidophyte) specific |

| 4617F | TCCTGCCAGTAGTCATATGC | Eukaryotic general |

| 35F | GTCTCAAAGATTAAGCCATGC | Eukaryotic general |

| 128F/R | TACTGTGAAACTGCGAATGGCTC | Eukaryotic general |

| 516F/R | CACATCTAAGGAAGGCAGCA | Eukaryotic general |

| 683F/R | TTGGAGGGCAAGTCTGGTGCC | Eukaryotic general |

| 1072F | GGGATAGTTGGGGGTATTCGTATT | Eukaryotic general |

| 1416R | TTCAGCCTTGCGACCATACTC | Eukaryotic general |

| 1590F | AACGAGACCCCCGCCTGCTAA | Eukaryotic general |

| 1815F/R | GGAAGTTGGGGGCAATAACAGG | Eukaryotic general |

| 4618Rb | TGATCCTTCTGCAGGTTCACCTAC | Eukaryotic general |

| ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 primersa | ||

| 4618F | GTAGGTGAACCTGCAGAAGGATCA | Eukaryotic general |

| ITSF/R | ATGTCTTGGTTCCCACAACGATG | Semi-eukaryotic specific |

| LSU1R | ATATGCTTAAATTCAGCGGGT | Eukaryotic general |

| 16S primersa,c | ||

| 880F/R | ATAACTGACACTCAGAGACGACA | Plastid specific |

| 1809R | CAGTACGGCTACCTTGTTACGA | Prokaryotic general |

F (forward) and R (reverse) correspond to the direction of the primer.

Additional primers were utilized to generate the plastid sequence for F. japonica CCMP 1661 (Tengs et al. 2000).

Sequencing and phylogenetic analyses

Extracted bands for all three loci derived from cultures were sequenced using the DYEnamic™ ET Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The sequencing reactions contained the following: 2 μL dye (diluted 1:5), 1 μL of desired primer (0.4 μM final concentration), 1.75 μL sterile H2O, and 0.25 μL of gel purified product. Cycling parameters were as follows: 25 cycles of 95° C for 20 s, 55° C for 15 s, and 60° C for 1min. After cycling, sequencing reactions were centrifuged through Sephadex G50 to remove unincorporated dye (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden). Sequencing was performed on either the ABI 377 (Perkin Elmer) or the 3100 capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Several forward and reverse primers were used to sequence various overlapping fragments. These fragments were combined and inspected for nucleotide ambiguities using Sequencher (version 4.1.2, Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and then aligned to other raphidophytes and closely related organisms utilizing the software MacClade (version 4.04; Maddison & Maddison; Sinauer Associates Inc., Sunderland, MA, USA).

Phylogenetic analyses were performed on the 18S and 16S alignments using PAUP* (version 4.0, Swofford 1999). Minimum evolution (ME) distance trees were made for both data sets using Kimura 2-parameter (K2P) distances and heuristic searches [10 × random addition of the sequences and tree-bisection-reconnection (TBR) branch swapping]. These topologies were used by the program Modeltest (Posada and Crandall 1998) to pick the most appropriate models for sequence evolution. For the 18S alignment, a model assuming unequal base frequencies, among-site rate variation (four categories), proportion of invariable sites, and a Tamura-Nei substitution matrix (Tamura and Nei 1993) was chosen. For the 16S data set, the model favored assumed unequal base frequencies, among-site rate variation (four categories), proportion of invariable sites, and a general time reversible substitution matrix (Tavaré 1986). These models with their corresponding parameters were used in ME distance analyses with maximum likelihood distances. Heuristic searches with 10 × random addition of sequences were done using TBR branch swapping. Branch lengths were constrained to be nonnegative, and polytomies were collapsed for distances <e−8. To assess branch stability, 100 bootstrap replicates were analyzed for each data set using the models described above.

Pairwise similarities between sequences were calculated utilizing the “BLAST 2 sequences” tool available through NCBI (Tatusova and Madden 1999). The default penalty values were used for gap opening (5), gap extension (2), and gap × drop-off (50). Expect value was 10, and the filter was inactivated for the analysis.

Real-time PCR assays

Development of real-time assays followed a similar approach as previously described for other harmful algal bloom species (Bowers et al. 2000, Oldach et al. 2000, Tengs et al. 2001). We first compiled a matrix of known raphidophyte sequence data deposited in GenBank and added data we generated from additional cultures. We designed primers to be used in conjunction with species-specific probes in real-time PCR assays based on Taqman technology (Holland et al. 1991, Wittwer et al. 1997). The assay for C. verruculosa was targeted to the 18S rRNA locus, and the assays for C. subsalsa and the C. marina/antiqua/ovata complex were both designed to target the ITS region.

Species-specific assays were designed to target the large subunit (LSU; 28S) rRNA for H. akashiwo and F. japonica. Oligonucleotide primer and probe sequences were selected based on an alignment of available sequences from GenBank: H. akashiwo (AF210744), F. japonica (AF210740), C. antiqua (AF210737), C. subsalsa (AF210736), C. ovata (AF210738), C. marina (AF210739), Vacuolaria virescens (AF210742), Nanochloropsis oculata (AF210744), and Olisthodiscus luteus (AF210743). Sequences were aligned using DNASIS v. 3.6. Candidate primers and probes were then screened against all known sequences in GenBank using the NCBI BLAST program (Altschul et al. 1997).

Primers and HPLC purified probes were synthesized by QIAGEN (Qiagen/Operon) and are presented in Table 3. Each reaction contained the following: 0.1U Taq Pro (Denville Scientific), 1 × PCR buffer, 4mM MgCl2, 0.2 μM forward primer, 0.2 μM reverse primer, 0.3mM each deoxynucleotide triphophosphate (Invitrogen), 0.25mg · mL−1 bovine serum albumin (Idaho Technology), 0.3 μM Taqman probe, molecular grade water to 10 μL or 25μL, and 1 μL DNA template. Assays were performed on either the Lightcycler 32 (Idaho Technology Salt Lake City, Utah, USA) or the Smartcycler (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The following cycling parameters were used: 50 cycles of 94° C for 0 s (i.e. touchdown step; 15 s on Smartcycler) and annealing temperature (varied for each assay; Table 3) for 20 s (30 s on Smartcycler). For Smartcycler reactions, cycling included an initial denaturing step for 2 min at 95° C. Fluorescence acquisition occurred after each cycle.

Table 3.

Primers and probes for species-specific real-time PCR assays targeting various raphidophytes. Five different assays were designed and validated against the panel of cultures listed in Table 1.

| Target organism | Oligo | Primer/probe | Target loci | Sequence 5′–3′ | Amplicon length | Annealing temperature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chattonella verruculosa | 227 | 58° C | ||||

| ChattaqFor | Forward | 18S rRNA | CCGTAGTAATTCTAGAGCTAATACRTGCA | |||

| ChattaqRev | Reverse | 18S rRNA | AATTCTCCGTTACCCGTTAAAGCCAT | |||

| CVerrProbe | Probe | 18S rRNA | [6~FAM]AATGGCGCGCAAGCG-TGTATTATG[TAMRA~Q] | |||

| C. marina | 224 | 60° C | ||||

| C. antiqua | CmarinaFor | Forward | ITS2 rRNA | GGTAGTTGCCGTACATTTTGCTCTT | ||

| C. ovata | CmarinaRev | Reverse | ITS2 rRNA | AAAAGTGGATTCAGCCGAAGCTTC | ||

| CmarinaProbe | Probe | ITS2 rRNA | [6~FAM]TTGAGTTCAACGGGCGTG-GTAGC[BHQ~6~FAM] | |||

| C. subsalsa | 156 | 60° C | ||||

| SubsalsaFor | Forward | ITS2 rRNA | TTGGATTCCGACGGGC | |||

| SubsalsaRev | Reverse | ITS2 rRNA | ATATGCTTAAATTCAGCGGGTTTT | |||

| SubsalsaProbe | Probe | ITS2 rRNA | [6~FAM]TTCGGCCAAGCACACAT-CCTC[TAMRA~6~FAM] | |||

| Fibrocapsa japonica | 167 | 57° C | ||||

| Fjap490For | Forward | 28S rRNA | TGAAAACGGCCCGTACACA | |||

| Fjap657Rev | Reverse | 28S rRNA | CGGGAACAGCTCATGATGT | |||

| Fjap578Probe | Probe | 28S rRNA | [6~FAM]CGGCTGGACACGCTTCTG[BHQ1~Q] | |||

| Heterosigma akashiwo | 228 | 62° C | ||||

| Haka127For | Forward | 28S rRNA | AAAGGTGCGTGCTCAGTCGTGGT | |||

| Haka355Rev | Reverse | 28S rRNA | CAAAAGTCTTTTCATCTTTCCCT | |||

| Haka222Probe | Probe | 28S rRNA | [5TET]TACGAGCCGTTTCCGACGA[BHQ1~Q] |

Loci were chosen based on ability to distinguish target species from others. Amplicon length and annealing temperatures are provided.

Assay validation

All five assays were validated by testing them against a panel of raphidophyte and dictyochophyte cultures (Table 1). The lower limits of detection (copy number of target) were determined by testing each assay against a serial dilution of plasmid containing the target sequence. First, PCR was performed utilizing the primers outlined in Table 3 for each species. The resulting amplicons were gel purified (as described above), ligated into pCR® 2.1 vector and transformed into One Shot® Top 10F′ chemically competent cells following manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Cells were streaked onto LB plates containing ampicillin, X-gal, and IPTG according to the manufacturer’s protocol and incubated overnight at 37° C. Sterile pipet tips were used to transfer white colonies into 3mL of LB broth containing ampicillin. These inoculations were incubated overnight at 37° C on a shaker. Plasmid preps were performed as outlined in the manufacturer’s instruction supplied with the QIAPrep® Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen/Operon) and serial dilutions were prepared.

In order to validate the use of these assays on environmental samples, we tested samples received in 2005 from MD-DNR (n=9) and DE-DNREC (n=21) for which cell counts were available for raphidophyte species. Samples were tested (non-quantitatively) with the H. akashiwo, F. japonica, C. subsalsa, C. marina/antiqua/ovata, and C. verruculosa probes (Table 4). Qualitative results from these assays were compared with cell counts (positive or negative) to calculate percent agreement in Table 4.

Table 4.

Taqman assays for Heterosigma akashiwo, Fibrocapsa japonica, Chattonella subsalsa, and C. antiqua/marina/ovata were deployed on environmental samples collected by Maryland Department of Natural Resources (MD-DNR) and Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DE-DNREC) during their 2005 routine monitoring programs.

| Organism | Total tested | # pos. PCR | # pos. cell count | # neg. PCR/neg. cell count | # pos. PCR/neg. cell count | # neg. PCR/pos cell count | # pos. PCR/pos. cell count | % agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. akashiwo | 30 | 26 (87%) | 17 (57%) | 2 | 11 | 2 | 15 | 57 |

| F. japonica | 30 | 6 (20%) | 2 (7%) | 24 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 87 |

| C. subsalsa | 30 | 18 (60%) | 16 (53%) | 11 | 4 | 1 | 14 | 83 |

| C. ant./mar./ova. | 30 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100a |

Assay results were compared with cell counts (qualitatively) to determine percent agreement between the two methods.

This species complex has not been observed in Maryland or Delaware waters. pos., positive; neg., negative.

RESULTS

Cultures

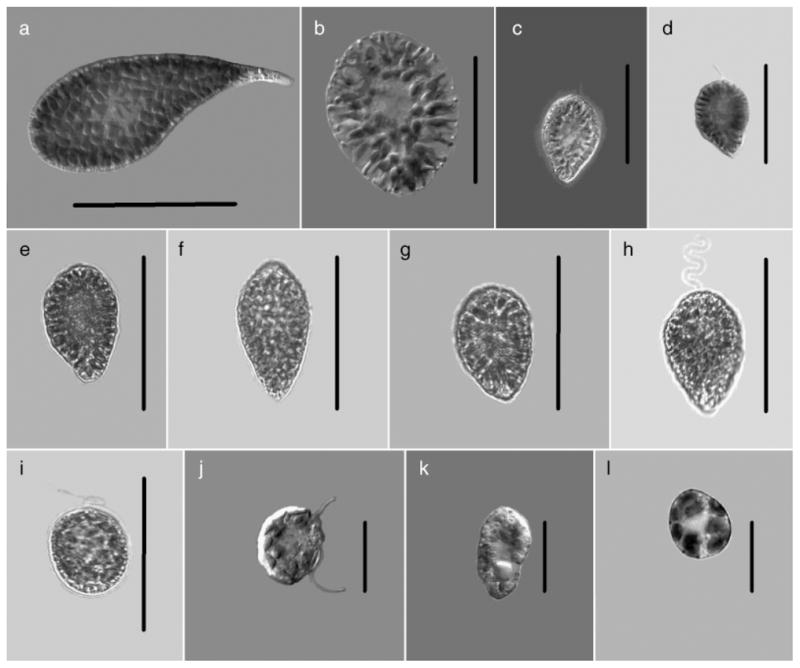

Because raphidophytes lack rigid cell walls, their morphology is somewhat flexible. In general, size, shape, and motion of living cells were the best clues; but as they easily distort with fixation, fixed field samples are the least helpful in identification based on morphology. Of the cells used in this study (Fig. 3), all were observed live from rapidly growing log phase cultures where their morphology tended to be most consistent for the species. All live raphidophytes subjected to stress will become spherical, lose motility, and become indistinguishable from one another except for size. Members of the genus Chattonella showed the widest variability in morphology. C. antiqua (Fig. 3a) was the largest of the species with long (70–155 μm) cells having a large, flattened anterior portion of the cell. This highly motile, serpentine species exhibited some flexibility with its cell capable of bending slightly when making tight turns. It was the easiest member of this genus to identify with a morphology that remained constant in vigorously growing cells. When senescent, shorter, oval, and even rounded cells were seen but always having tightly packed chloroplasts.

Fig. 3.

Cells from clonal raphidophyte cultures used in this study: (a) Chattonella antiqua, (b) C. ovata, (c) C. marina, (d) C. subsalsa (Japan), (e) C. subsalsa (Delaware), (f) C. subsalsa (Salton Sea), (g) C. subsalsa (Sardinia), (h) C. subsalsa (Texas), (i) Fibrocapsa japonica (South Carolina), (j) Heterosigma akashiwo (Japan), (k) H. akashiwo North Carolina, (l) H. akashiwo (Milford). Scale bars: a, b=50 μm, c–i=30 μm, j–l=20μm.

The next largest, C. ovata (Fig. 3b) overlapped in size slightly with C. antiqua (65–84 μm) but was easily distinguished by its broadly oval shape with radiating, loosely packed chloroplasts. Some motile cells were rounded with well-defined flagella, but for the most part, actively moving cells were oval. The loosely packed chloroplasts with clear spaces between them, oval shape, and relatively large size made it difficult to mistake this for other members of this genus. C. marina (Fig. 3c) and C. subsalsa (Fig. 3, d–h) were the two species most likely to be confused. Both had similar sizes (33–46 μm), tightly packed chloroplasts, pyriform cell shapes with broadly rounded anterior and tapering posterior cell regions and both with golden brown coloration. Of the two, C. marina tended to be slightly broader, ending in a blunt, less pointed posterior region with chloroplasts extending to fill the cell entirely. In contrast, C. subsalsa always had chloroplasts ending before the pointed posterior, leaving it colorless or clearly absent of pigmentation. This feature was difficult to observe unless cells were in welled slides with enough liquid to allow free movement. The colorless posteriors were diagnostic in C. subsalsa and were never seen in C. marina. Within those called C. subsalsa (Fig. 3, d–h), no distinguishable morphological features separated them from one another. Aside from the C. subsalsa Japan (Fig. 3d) being slightly smaller, all clones closely resembled each other including the “Mediterranean type” C. subsalsa (Sardinia, Oristano Lagoon).

F. japonica was among the easiest raphidophyte to identify (Fig. 3i) with a clearly oval shape (32–48 μm) packed with golden brown chloroplasts and diagnostic mucocysts in the posterior region of the cell. The extreme posterior area had the greatest number of mucocysts, leaving all cells with a clearly hyaline region at the extreme opposite from where flagella were seen. While F. japonica can be seen as a rounded cell, the majority of the time the cells were oval. Motility was less vigorous than any of the other raphidophytes, and in those cases when exposed to high light intensities, the chloroplasts were highly reduced. This species was less likely to distort with fixation either with Lugol’s solution or with formalin.

The other highly variable morphology was observed in H. akashiwo (Fig. 3, j–l). The smallest of the raphidophytes with cells varying from 18–34 μm, this species showed the greatest variability in morphology. These small, densely packed cells having 18–27 chloroplasts were normally golden brown in coloration. H. akashiwo was highly motile, exhibiting gliding as well as twirling motion. Cells appeared angular, flattened, or completely rounded and exhibited all these shapes within the same culture. This species is highly distorted by fixatives, rendering it almost impossible to identify from morphology alone. There was no significant difference in morphology from cells from Japan (Fig. 3j); North Carolina (Fig. 3k); or Milford, Connecticut (Fig. 3l).

18S sequencing

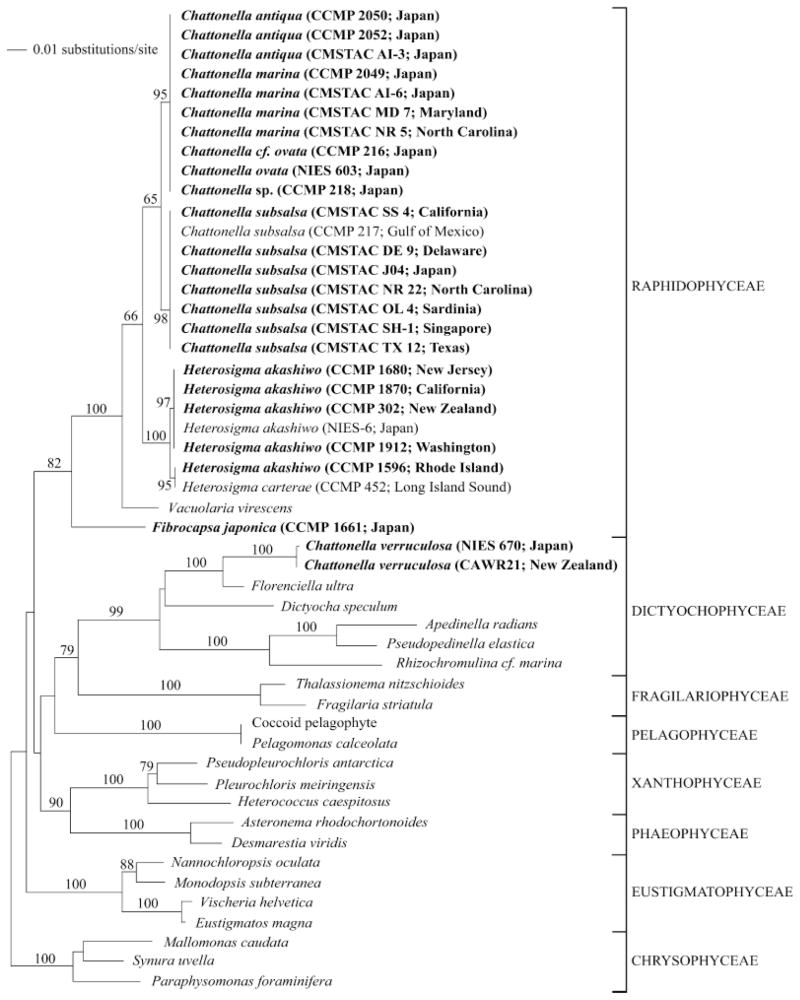

We sequenced the nuclear encoded 18S locus (>1700 bp) of a panel of raphidophyte cultures (n=25; see Table 1 for GenBank accession numbers), including the first published sequence data for C. verruculosa. The two isolates (Japan and New Zealand) shared 99% sequence similarity (number of identical base pairs divided by sequence length) and were genetically closer to the Dictyochophyceae than to Raphidophyceae (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Minimum evolution analysis of the 18S rRNA alignment using maximum likelihood distances (distance score: 1.30857). Bootstrap values above 60% are indicated. The following GenBank accession numbers, not listed in Table 1, were included in the phylogenetic analyses: Chattonella subsalsa U41649; Vacuolaria virescens U41651; Heterosigma akashiwo AB001287; H. carterae U41650; Apedinella radians U14384; Pseudopedinella elastica U14387; Rhizochromulina cf marina U14388; Dictyocha speculum U14385; Florenciella ultra AY254857; Coccoid pelagophyte U40927; Pelagomonas calceolata U14389; Pleurochloris meiringensis AF109728; Pseudopleurochloris antarctica AF109729; Heterococcus caespitosus AF083399; Asteronema rhodochortonoides AB056156; Desmarestia viridis AJ295828; Fragilaria striatula X77704; Thalassionema nitzschioides X77702; Eustigmatos magna U41051; Vischeria helvetica AF045051; Monodopsis subterranea U41054; Nannochloropsis oculata AF045044; Mallomonas caudata U73228; Paraphysomonas foraminifera AF174376; and Synura uvella U73222. Cultures in bold were deposited as part of this study, and collapsed branches indicate identical sequences.

Isolates of C. subsalsa (n=7) collected from a global geographic network had 100% sequence similarity and differed by only two base pairs from the only C. subsalsa 18S sequence previously deposited (U41649). Isolates of C. antiqua, C. ovata, C. marina, and C. sp. (n=10; Fig. 1) had 100% sequence similarity and shared 99% sequence similarity to the C. subsalsa isolates. The 18S locus of H. akashiwo was well conserved among the geographically distinct isolates that we sequenced (n=5). The sequences had a 99%–100% sequence similarity to data previously deposited in GenBank for this organism (n=6; AY788932-AY788936). Sequence data for the 18S locus of F. japonica were also generated (Table 1, Fig. 1). Figure 1 depicts the ME distance tree generated for all raphidophyte sequence data deposited from this study (in bold) as well as sequences downloaded from GenBank.

ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 sequencing

Sequence data spanning the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 region (>550 bp) were derived for several raphidophyte cultures (n=20; see Table 1 for GenBank accession numbers). Cultures of C. subsalsa from eight geographically distinct regions were sequenced. These shared 100% sequence similarity to each other and to the two available sequences in GenBank (AF409126 and AF153196). At this locus, the C. subsalsa isolates more clearly diverged (approximately 10% dissimilarity) from the C. antiqua, C. ovata, and C. marina complex, and we therefore utilized this sequence region in development of a C. subsalsa real-time assay. As with the 18S locus, the ITS locus was 100% conserved for all geographically distinct isolates of C. antiqua, C. ovata, C. marina, and C. sp. (n=10). The sequence representing these various species had 100% sequence similarity to C. marina (AF137074) and one base pair difference from another C. marina (AY704165), C. antiqua (AF136761), and two base pairs difference from C. ovata (AY704166). One culture of C. marina (CCMP 2049) that we sequenced contained a polymorphism at one nucleotide position, which was confirmed by five overlapping sequence reads.

Three H. akashiwo cultures sequenced (Table 1) had 100% sequence similarity to 21 sequences previously deposited (AF409124, AF157381-AF157386, AF163817, AF096283, AF110823, AF112993, AF125579, AF126214, AF128237, AF132296, AF132549, AF134727, AF134728, AF135436, AF135786, AF151016) in GenBank. Two other previously deposited H. akashiwo sequences shared 97% (AF152602) and 98% (AY704164) similarity to the group of sequences listed above. We were unable to obtain a clean consensus sequence from F. japonica for this locus. This was most likely due to sequence polymorphisms.

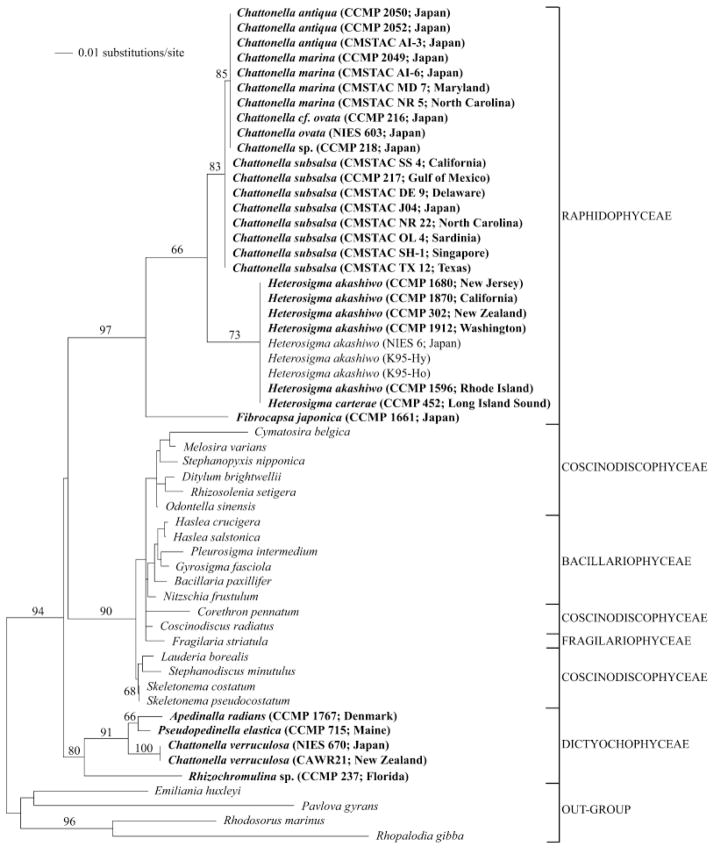

16S sequencing

We partially sequenced the plastid encoded 16S locus (approximately 600 bp) of several raphidophyte (n=26) and dictyochophyte (n=3) cultures (see Table 1 for GenBank accession numbers). The two isolates of C. verruculosa had 100% sequence similarity, and these sequences grouped with the Dictyochophyceae in the phylogenetic analyses performed, as observed with the 18S analysis (Fig. 2). Sufficient variation was present in the 16S locus, as observed with the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 locus, to enable differentiation of C. subsalsa isolates from the C. marina/antiqua/ovata/sp. complex. Again, the conserved nature of this locus for the C. subsalsa isolates from a broad range of geographically distinct locales (n=8) was observed. The members of the C. marina/antiqua/ovata/sp. complex were identical in the 16S plastid locus.

Fig 2.

Minimum evolution analysis of the 16S rRNA alignment using maximum likelihood distances (distance score: 1.05415). Bootstrap values above 60% are indicated. The following GenBank accession numbers, not listed in Table 1, were included in the phylogenetic analyses: Heterosigma akashiwo AB181955, AB181956, AB181958; Cymatosira belgica AJ536456; Melosira varians AJ536464; Stephanopyxis nipponica AJ536465; Ditylum brightwellii AJ536460; Rhizosolenia setigera M87329; Odontella sinensis AJ536457; Haslea crucigera AF514849; Pleurosigma intermedium AF514848; Haslea salstonica AF514854; Bacillaria paxillifer AJ536452; Corethron pennatum AJ536466; Fragilaria striatula AJ536453; Gyrosigma fasciola AF514847; Nitzschia frustulum AY221721; Coscinodiscus radiatus AJ536462; Lauderia borealis AJ536459; Stephanodiscus minutulus AY221720; Skeletonema costatum X82154; Skeletonema pseudocostatum X82155; Rhodosorus marinus AF170719; Rhopalodia gibba AJ582391; Emiliania huxleyi X82156; and Pavlova gyrans AF172715. Cultures in bold were deposited as part of this study, and collapsed branches indicate identical sequences. Because this analysis is based on short sequences (approximately 640 bp), it is shown to depict sequence diversity and should not be used to draw taxonomic conclusions.

Intraspecies conservation was again observed for isolates of H. akashiwo, which were isolated from six different locations. Our H. akashiwo sequences shared 98% similarity to the three H. akashiwo 16S sequences previously deposited (AB181955, AB181956, AB181958). When aligned with the rest of the data in our 16S alignment, the sequence from F. japonica had a large, unique insertion (length: approximately 285 bp).

Taqman assays

Five real-time PCR Taqman assays were developed and validated against the panel of cultures listed in Table 1. The assay for C. verruculosa was successfully validated for specificity. An initial assay designed to target the 18S rRNA of C. subsalsa also detected the C. marina/antiqua/ovata/sp. complex. The assay was further refined and targeted to the ITS region of C. subsalsa, which is genetically distinguishable from the above species complex using this locus. A separate assay was designed to detect the C. marina/antiqua/ovata/sp. complex also based on ITS. The specificity of both assays was confirmed against all cultures listed in Table 1, and both were able to detect isolates across a broad geographic range. The assays for H. akashiwo and F. japonica were also validated against the panel listed in Table 1.

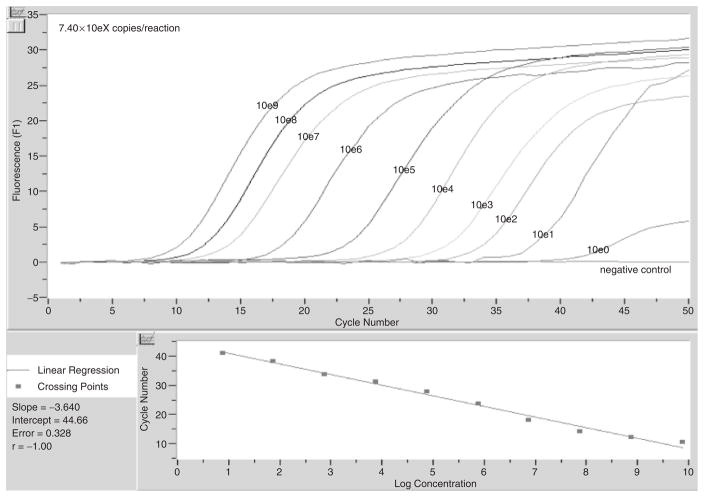

The lower limit of detection was determined for each assay based on serial dilutions of plasmids containing target amplicons. Reaction efficiencies were calculated by the Lightcycler software. Fig. 4 depicts the standard curve generated from the serial dilution of plasmid containing the H. akashiwo target and shows that the last dilution detected represents 7.4 copies of the target in the reaction (reaction efficiency of 93%). The remaining lower limits of detection for each assay were as follows (data not shown): 7.32 copies for C. subsalsa (reaction efficiency of 94%), 7.20 copies for F. japonica (reaction efficiency of 106%), 6.40 copies for C. marina/antiqua/ovata (reaction efficiency of 98%), and 4.6 copies for C. verruculosa (reaction efficiency of 93%).

Fig. 4.

Serial dilution of plasmid containing the 28S rRNA target for the H. akashiwo real-time PCR assay. The plasmid was prepared by ligating the target amplicon into pCR® 2.1 vector and transforming into One Shot® Top 10F′ chemically competent cells. The lower limit of the assay was 7.40 copies of the target in the reaction.

Table 4 shows the correlation of probe results to cell counts for environmental samples collected in 2005 by MD-DNR and DE-DNREC. A total of 30 samples were compared, with 57% of results in agreement for H. akashiwo, 87% for F. japonica, 83% for C. subsalsa and 100% for C. antiqua/marina/ovata (the latter species complex has not been observed via morphology in Maryland or Delaware waters; W. Butler and E. Whereat personal communication). All samples were also tested with the probe for C. verruculosa (all were negative); however, this species has never been observed in mid-Atlantic waters via microscopy or molecular probes. There were 19 cases in which a sample was positive via probe assay, but cell counts for the corresponding species were negative. In three cases, a probe was negative while the corresponding species was detected via microscopy.

DISCUSSION

Work presented here has greatly increased the raphidophyte sequence data available to the scientific community through GenBank. A total of 74 sequences were deposited: 25 18S rRNA, 20 ITS1-5.8S-ITS2, and 26 plastid 16S (plus three additional from Dictyochophyceae cultures). These data allowed us to perform phylogenetic analyses based on nuclear 18S and plastid 16S loci in order to better understand the relationships between members of the family Raphidophyceae and with other stramenopiles. Because the 16S analysis is based on short sequences (approximately 640 bp), Figure 2 is shown to illustrate sequence diversity and does not depict any taxonomic conclusions. In addition, we have provided validated primer and probe sequences for five real-time PCR assays targeting various species; C. verruculosa, C. subsalsa, the C. marina/ovata/antiqua complex, H. akashiwo, and F. japonica.

Early phylogenetic analyses of raphidophyte species were based on morphological characteristics, and it has long been recognized that they belong to the division Heterokonta (Leedale 1974, Moestrup 1982, Heywood 1990). Subsequent analyses utilizing genetic sequence data were limited for this group. The first sequence data for a raphidophyte species were published by Cavalier-Smith and Chao (1996) for the nuclear 18S locus of H. carterae (=H. akashiwo). Potter et al. (1997) combined these data with 18S sequence data from an isolate of C. subsalsa to confirm the Raphidophyceae as a monophyletic group, supporting several previous classifications (Silva 1980, Heywood 1990). Other raphidophyte sequence data for 18S and the ITS region were generated as this early work, including data for several H. akashiwo isolates from the Atlantic and Pacific basins (Connell 2000), data for C. subsalsa and H. akashiwo isolates as part of a study determining the evolutionary relationships among Heterokonts (Ben Ali et al. 2002), and data from several unpublished studies (sequences deposited on GenBank). Where applicable, these sequences were included in our phylogenetic analyses. In order to enhance these early efforts, there was a clear need to fill in gaps for available sequence data and to genetically characterize additional cultures that have been obtained and maintained by several different groups including CMSTAC, CCMP, CAAE, and SCAEL. Furthermore, clarification was needed to determine the relationship of C. verruculosa to members of the Raphidophyceae.

Sequence data (nuclear 18S and plastid 16S) and phylogenetic analyses presented here from two C. verruculosa cultures support the notion that this species belongs to the Dictyochophyceae and not Raphidophyceae (Bowers et al. 2004, Edvardsen et al. submitted). Although one culture was isolated from Japan and the other from New Zealand, they shared 99% sequence similarity in the 18S region and shared 100% sequence similarity with respect to the plastid 16S locus. Sequencing of the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 loci gave mixed sequence reads, and a consensus sequence could not be obtained, an observation that has previously been made by others (B. Edvardsen, personal communication). This could be due to nonclonal cultures or the presence of sequence variation between the multiple copies of this locus in the genome. Because C. verruculosa has been confirmed to produce brevetoxin (C. Tomas, unpublished data), it is important to gain a better understanding of the placement and distribution of this species.

The C. subsalsa isolates used in this study were surprisingly conserved across all three loci sequenced, despite their vast global distribution (East Coast and Gulf Coast of the United States, Japan, Singapore and Sardinia). This is quite remarkable, because genomic ITS sequences, in general, are known for having rapid divergence rates and are commonly targeted in algal genetics research to assess inter-and intraspecies variations, especially across broad geographic locations (Bakker et al. 1992, Coleman et al. 1994, Zechman et al. 1994, Kooistra et al. 2001, Zoller and Lutzoni 2003, Leskinen et al. 2004, Orsini et al. 2004).

Sequencing of all three loci from several isolates of C. marina, C. ovata, and C. antiqua suggests genetic identity consistent with earlier observations by Sako et al. (2000) and Connell (2000, 2002). These original observations were based on sequencing nuclear encoded 18S and ITS of a few cultures. Herein, we have added 18S data from several additional cultures, as well as plastid encoded 16S data to support these findings. Despite marked sequence identity, these organisms can be separated on the basis of morphological criteria (Fig. 3, a–e, and described below). We also determined that C. sp. (CCMP 218) shares identical sequence data to this complex. Ongoing efforts by our laboratory involve the sequencing of other loci in an effort to differentiate these organisms genetically, which will allow us to design species-specific assays.

Earlier work by Connell (2000) determined that several isolates of H. akashiwo from both the Atlantic and Pacific basins were surprisingly conserved in the ITS region. Our work included sequencing 18S, ITS1-5.8S-ITS2, and 16S from several additional cultures, which confirmed this prior observation. These three loci shared 100% sequence similarity among the cultures we used and were either identical or differed by only a few base pairs from sequence data previously deposited in GenBank by others. Interestingly, CCMP 1596 had one base pair difference in the 18S locus from the other H. akashiwo cultures, which was also observed in the early H. carterae (=H. akashiwo; CCMP 452) sequence deposited by Potter et al. (1997).

We derived sequence data for the 18S locus of F. japonica, and Figure 1 depicts its placement among the raphidophytes and other stramenopiles. Sequencing of the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 region identified several polymorphisms. Kooistra et al. (2001) previously described polymorphisms in the same locus from this same isolate; however, only one polymorphism matched between the two laboratories, so current efforts are underway to resolve this discrepancy. Kooistra found that older (approximately 1970) cultures of F. japonica did not contain any polymorphisms, while those collected more recently contained the most. Several theories are suggested, a situation which clearly underlines the need to better understand the genetics of this species. Ongoing research in our laboratory will focus on molecular analyses of several F. japonica strains using various loci. We present the first published sequence data for the 16S locus of F. japonica, and Figure 2 depicts its placement among the raphidophytes and other stramenopiles.

In addition to greatly enhancing the available raphidophyte sequence data, this work also makes available probe and primer sequences for five real-time PCR assays: C. verruculosa, the C. marina/antiqua/ovata complex, C. subsalsa, H. akashiwo, and F. japonica. These assays were validated extensively against other Raphidophyceae, as well as other organisms (data not shown). Because the raphidophytes lack a firm cell wall, they are highly pleomorphic, and this creates problems for identification of living as well as preserved cells. The utility of the real-time PCR assays, particularly with preserved material, offers a great advantage in clearly distinguishing between species of these highly variable cells.

The results presented in Table 4 compare molecular probe results to cell counts for raphidophyte species performed on environmental samples. Overall, there was strong agreement between the two methods. In the case of discrepancies, it was more common for the PCR assay to be positive with corresponding negative cell counts (19 cases) than for PCR assay results to be negative with corresponding positive cell counts (three cases). Interestingly, in those three cases, the cell counts were not unusual (higher or lower) than counts for the other samples. In this study, the molecular probe assays appear to have demonstrated greater sensitivity over microscopy.

There are several caveats associated with bothmethods, which should be considered when performing comparative analyses. Caveats related to microscopy include but are not limited to: analysis of live versus preserved samples (raphidophyte species can be difficult to distinguish after preservation), if live samples are analyzed there may be a shift in algal composition between time of collection and time of analysis, magnification and light source, difficulties inherent to species identification in very heterogeneous samples, the probability of not detecting an organism with only a few cells present, and variability inherent with different levels of personnel expertise.

Molecular methods can overcome many of these obstacles because of increased sensitivity and automation (thus researcher variability is minimized), and because DNA is the target, either live or preserved samples can be analyzed. Given these benefits, there are also caveats associated with the use of this method. For example, presence of inhibitors (e.g. humic acids) in samples can co-extract with DNA and affect assay efficiency, although many kits are designed to overcome this obstacle. A sample containing a very high concentration of cells may also affect reaction efficiency by introducing a large amount of competing DNA in the sample, a problem that can be overcome by diluting the sample and rerunning the assay. Furthermore, molecular probes are limited by the availability of sequence data for various organisms. A probe designed for isolates from one region may or may not detect isolates of the same organism from a different geographic location.

Genetic and morphological variability should also be taken into consideration when using these methods for detecting species and when using those data to make comparisons. For example, some species may appear to have differences in morphology but are the same genetically (as demonstrated with C. marina, C. antiqua, and C. ovata). In contrast, species may appear to be the same morphologically but are genetically distinct. Both of these examples may lead to differences in results obtained from methods. Therefore, the caveats mentioned above need to be taken into consideration when using various methods for species detection and before implementing those methods in a monitoring program.

Blooms of raphidophytes are becoming more recognized, but today there is still a large underestimate of their abundance and appearance due to the distortion related to use of fixatives. The greatest utility of the molecular tools presented here is the identification of preserved samples of raphidophytes. While F. japonica may be well distinguished in preserved form, the same is not true particularly for the Chattonella species and H. akashiwo. All these species easily lyse with fixatives and become unrecognizable. The accuracy and ease of use of the molecular probes described here thus offer a vastly improved capability to estimate the cellular abundances and occurrences of these bloom species. For some, the species distinction may hold an additional significance. For instance, the difference between C. subsalsa and C. marina blooms, which are difficult at best to discern with actively growing cell morphology, signifies the difference between a potentially toxic species (C. marina) and a species not necessarily considered toxic (C. subsalsa). While much work is needed to define toxicity in the raphidophytes and in particular in Chattonella species, molecular probes can serve as a first pass in identifying the presence of these species.

The molecular probes will also offer a huge advantage in being able to process previously collected fixed samples. Archived samples may now be used in retrospective studies to confirmthe presence of toxic species or blooms of noxious raphidophytes. These assays are currently being deployed in monitoring programs in Delaware, Maryland, and South Carolina in order to gain a better understanding of their distributions. The availability of these assays, along with the extensive sequence data deposited as part of this study, will serve to greatly enhance the study of raphidophyte species. Rapid real-time specific PCR assays can easily be incorporated into any monitoring program involving PCR detection of HAB species.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank C. Ono, S. Yoshimatsu, L. Rhodes, and M. Holms for cultures. The authors would also like to thank P. Williams (University of South Carolina) and K. Johnson (Medical University of South Carolina) for technical assistance, as well as SCAEL for sample collection and additional technical assistance. Thanks to F. Diaz-Mendez and S. Goto for sequencing, and to M. Oduori for testing environmental samples. Special thanks also to H. Glasgow, Jr. (Center for Applied Aquatic Ecology) and J. Wolny (Florida Marine Research Institute) for providing culture material for assay development. Thanks to Dr. Antonella Luglié, University of Sassari, Sardinia for samples of C. subsalsa from the Oristano Lagoon and to Dr. Gary Wickfors, NOAA/NMFS Milford, CT for the H. akashiwo culture. Thanks to M. Johnson (UMCES) for plastid primers and phylogenetic assistance. Thanks to E. Humphries (DE-DNREC), E. Whereat (DE Citizen’s Monitoring Group), P. Tango, W. Butler, and all the personnel at MD-DNR who provided environmental samples. We also greatly appreciate the useful comments and suggestions from two anonymous reviewers. This research project was funded by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control (D. Oldach), ECOHAB (NOAA/NSF/EPA/NASA/ONR) grant NA16OP2796 and NOAA grant NA06OA0675 (A. Lewitus), and North Carolina Water Resources Research Institute (WRRI) Project #50337 and NC DHHS/CDC Award #50531 (C. Tomas).

Abbreviations

- CAAE

Center for Applied Aquatic Ecology

- CCMP

Provasoli-Guillard National Center for Culture of Marine Phytoplankton

- CMSTAC

Center for Marine Science Toxic Algal Collection, University of North Carolina

- ITS

internal transcribed spacer

- SCAEL

South Carolina Algal Ecology Laboratories

Contributor Information

Holly A. Bowers, Institute of Human Virology, University of Maryland, 725 West Lombard Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201, USA

Carmelo Tomas, University of North Carolina at Wilmington, 5600 Marvin K. Moss Lane, Wilmington, North Carolina 28409, USA.

Torstein Tengs, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA.

Jason W. Kempton, South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, Marine Resources Research Institute, 331 Fort Johnson Road, Charleston, South Carolina 29422, USA

Alan J. Lewitus, Belle W. Baruch Institute for Marine and Coastal Sciences, University of South Carolina, Georgetown, South Carolina 29442, USA, South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, Marine Resources Research Institute, Hollings Marine Laboratory, 331 Fort Johnson Road, Charleston, South Carolina 29412, USA

David W. Oldach, Institute of Human Virology, University of Maryland, 725 West Lombard Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201, USA.

References

- Ahmed M, Khan S, Arakawa O, Onoue Y. Properties of hemagglutinins newly separated from toxic phytoplankton. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1243:509–12. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(94)00184-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T, Momoyama K, Hiraoka M. A harmful flagellated plankton increased in Tokuyama Bay. Bull Yamaguchi Pref Naikai Fish Exp Stn. 1995;24:1121–2. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Backe-Hansen P, Dahl E, Danielssen D. On a bloom of Chattonella in the North Sea/Skagerrak in April–May 1998. In: Hallegraeff G, Blackburn S, Bolch C, Lewis R, editors. Harmful Algal Blooms 2000. Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO; Paris: 2001. pp. 78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker FT, Olsen JL, Stam WT, van den Hoek C. Nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS1 and ITS2) define discrete biogeographic groups in Cladophora albida (Chlorophyta) J Phycol. 1992;28:839–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ali A, De Baere R, De Wachter R, Van de Peer Y. Evolutionary relationships among heterkont algae (the autotrophic stramenopiles) based on combined analyses of small and large subunit ribosomal RNA. Protist. 2002;153:123–32. doi: 10.1078/1434-4610-00091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biecheler B. Sur une chloromonadine nouvelle d’eau saumâtre Chattonella subsalsa n. gen., n. sp. Arch Zool Exper Gen. 1936;78:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Black E, Whyte J, Bagshaw J, Ginther N. The effects of Heterosigma akashiwo on juvenile Oncorhynchus tshawytscha and its implications for fish culture. J Appl Ichthyol. 1991;7:168–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdelais A, Tomas C, Narr J, Kubanek J, Baden D. New fish-killing alga in coastal Delaware produces neurotoxins. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:465–70. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers H, Tengs T, Goto S, Tomas C, Ono C, Yoshimatsu S, Oldach D. Development of real-time PCR assays for the detection of Chattonella species in culture and environmental samples. In: Steidinger KA, Landsberg JH, Tomas CR, Vargo GA, editors. Proceedings of the Xth International Conference on Harmful Algae; Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO; St. Petersburg, Florida. 2004. pp. 231–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers HA, Tengs T, Glasgow HB, Jr, Burkholder JM, Rublee PA, Oldach DW. Development of real-time PCR assays for rapid detection of Pfiesteria piscicida and related dinoflagellates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:4641–8. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.11.4641-4648.2000. Erratum Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgers A, McConnell E, Narr J, Weidner A, Tomas L, Tomas C. Comparison of regional clones of the genus Chattonella and Fibrocapsa for growth characteristics and potential toxin production. In: Steidinger KA, Landsberg JH, Tomas CR, Vargo GA, editors. Proceedings of the Xth International Conference on Harmful Algae; Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO; St. Petersburg, Florida. 2004. pp. 405–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith T, Chao EE. 18S rRNA sequence of Heterosigma carterae (Raphidophyceae), and the phylogeny of heterkont algae (Ochrophyta) Phycologia. 1996;35:500–10. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman AW, Suarez A, Goff LJ. Molecular delineation of species and syngens in volvocacean green algae (Chlorophyta) J Phycol. 1994;30:80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Connell L. Nuclear ITS region of the alga Heterosigma akashiwo (Chromophyta: Raphidophyceae) is identical in isolates from Atlantic and Pacific basins. Mar Biol. 2000;136:953–60. [Google Scholar]

- Connell L. Rapid identification of marine algae (Raphidophyceae) using three-primer PCR amplification of nuclear internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions from fresh and archived material. Phycologia. 2002;41:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsen B, Eikrem W, Shalchian-Tabrizi K, Riisberg I, Johnsen G, Naustvoll L, Throndsen J. Verrucophora verruculosa var. farcima gen. et var. nov. (Dictyochophyceae, Heterokonta), a bloom forming ichthyotoxic flagellate from Skagerrak, Norway. J Phycol. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Fu M, Koulman A, van Rijssel M, Lützen A, de Boer MK, Tyl MR, Liebezeit G. Chemical characterisation of three haemolytic compounds from the microalgal species Fibrocapsa japonica (Raphidophyceae) Toxicon. 2004;43:355–63. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs BM, Wallner G, Beisker W, Schwippl I, Ludwig W, Amann R. Flow cytometric analysis of the in situ accessibility of Escherichia coli 16S rRNA for fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;64:4973–82. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4973-4982.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukaya S, Honda D, Sako Y. Chattonella verruculosa (Raphidophyceae) is relative to silicoflagellates and pedinellids. Jpn J Protozool. 2002;35:67. [Google Scholar]

- Guillard RRL, Ryther JH. Studies of marine phytoplankton diatoms I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt, and Detonela confervacea (Cleve) Gran. Can J Microbiol. 1962;8:229–39. doi: 10.1139/m62-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallegraeff GM, Munday BL, Baden DG, Whitney PL. Chattonella marina raphidophyte bloom associated with mortality of cultured bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) in South Australia. In: Reguera B, Blanco J, Fernandez ML, Wyatt T, editors. Harmful Algae; Xunta de Galicia and Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO; Vigo, Spain. 1998. pp. 93–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y, Chihara M. Morphology, ultrastructure and taxonomy of the raphidophycean alga Heterosigma akashiwo. Bot Mag Tokyo. 1987;100:151–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y, Doi K, Chihara M. Four new species of Chattonella (Raphidophyceae, Chromophyta) from Japan. Jpn J Phycol. 1994;42:407–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hard J, Connell L, Hershberger W, Harrell L. Genetic variation in mortality of chinook salmon during a bloom of the marine alga Heterosigma akashiwo. J Fish Biol. 2000;56:1387–97. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood P. Systematic position of the Chloromonadophyceae. Br Phycol J. 1978;13:201A. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood P. Phylum Raphidophyta. In: Margulis L, Corliss JO, Melkonian M, Chapman DJ, editors. Handbook of Protista. Jones and Bartlett; Boston: 1990. pp. 318–25. [Google Scholar]

- Holland PM, Abramson RD, Watson R, Gelfand DH. Detection of specific polymerase chain reaction product by utilizing the 5′–3′ exonuclease activity of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:7276–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honjo T. Harmful red tides of Heterosigma akashiwo. NOAA Tech Rep NMFS. 1992;111:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka M, Takayama N, Hirai S, Gonda M, Hara Y. The occurrence of raphidophycean alga Chattonella sp (globular type) in Tokyo Bay, Japan. Bull Plank Soc Jpn. 1991;38:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Arakawa O, Onoue Y. A toxicological study of the marine phytoflagellate, Chattonella antiqua (Raphidophyceae) Phycologia. 1996a;35:239–44. [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Arakawa O, Onoue Y. Neurotoxin production by a chloromonad Fibrocapsa japonica (Raphidophyceae) J World Aquacult Soc. 1996b;27:254–63. [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Arakawa O, Onoue Y. Neurotoxins in a toxic red tide of Heterosigma akashiwo (Raphidophyceae) in Kagoshima Bay, Japan. Aquacult Res. 1997;28:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kooistra WHCF, deBoer MK, Vrieling EG, Connell LB, Gieskes WWC. Variation along ITS markers across strains of Fibrocapsa japonica (Raphidophyceae) suggests hybridization events and recent range expansion. J Sea Res. 2001;46:213–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lars-Johan N, Einar D, Didrik D. A new bloom of Chattonella in Norwegian waters. Harmful Algae News. 2002;(23):3, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Leedale GF. How many are the kingdoms of organisms? Taxon. 1974;23:261–70. [Google Scholar]

- Leskinen E, Alstrom-Rapaport C, Pamilo P. Phylogeographical structure, distribution and genetic variation of the green algae Ulva intestinalis and U. compressa (Chlorophyta) in the Baltic Sea area. Mol Ecol. 2004;13:2257–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JA, Nichols PD, Hallegraeff GM. Icthyotoxicity of Chattonella marina (Raphidophyceae) to damselfish (Acanthochromis polycanthus): the synergistic role of reactive oxygen species and free fatty acids. Harmful Algae. 2004;2:273–81. [Google Scholar]

- Medlin L, Elwood HJ, Stickel S, Sogin ML. The characterization of enzymatically amplified eukaryotic 16S-like rRNA-coding regions. Gene. 1988;71:491–9. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moestrup Ø. Flagellar structure in algae: a review with new observations particularly on the Chrysophyceae, Phaeophyceae (Fucophyceae), Euglenophyceae, and Reckertia. Phycologia. 1982;21:427–528. [Google Scholar]

- Murayama-Kayano E, Yoshimatsu S, Kayano T, Nishio T, Ueda H, Nagamune T. Application of the random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) technique to distinguish species of the red tide phytoplankton Chattonella (Raphidophyceae) J Ferment Bioeng. 1998;85:343–5. [Google Scholar]

- Oda T, Nakamura A, Shikayama M, Kawano I, Ishimatsu A, Muramatsu T. Generation of reactive oxygen species by raphidophycean phytoplankton. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1997;61:1658–62. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okaichi T. Red tide problems in the Seto Inland Sea, Japan. In: Okaichi T, Anderson DM, Nemoto T, editors. Red Tides—Biology, Environmental Science and Toxicology. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1987. pp. 137–9. [Google Scholar]

- Oldach DW, Delwiche CF, Jakobsen KS, Tengs T, Brown EG, Kempton JW, Schaefer EF, Bowers HA, Glasgow HB, Jr, Burkholder JM, Steidinger KA, Rublee PA. Heteroduplex mobility assay-guided sequence discovery: elucidation of the small subunit (18S) rDNA sequences of Pfiesteria piscicida and related dinoflagellates from complex algal culture and environmental sample DNA pools. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4303–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono C, Takano H. Chattonella antiqua (Hada) Ono comb. nov. and its occurrence on the Japanese coast. Bull Tokai Reg Fish Res Lab. 1980;102:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Onoue Y, Nozawa K. Separation of toxins from harmful red tides occurring along the coast of Kagoshima Prefecture. In: Okaichi T, Anderson DM, Nemoto T, editors. Red Tides: Biology, Environmental Science and Toxicology. Elsevier; New York: 1989. pp. 371–4. [Google Scholar]

- Orsini L, Procaccini G, Sarno D, Montresor M. Multiple rDNA ITS-types within the diatom Pseudo-nitzschia delicatissima (Bacillariophyceae) and their relative abundances across a spring bloom in the Gulf of Naples. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2004;271:87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Crandall KA. Modeltest: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter D, Saunders GW, Andersen RA. Phylogenetic relationships of the Raphidophyceae and Xanthophyceae as inferred from nucleotide sequences of the 18S ribosomal RNA gene. Am J Bot. 1997;84:966–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensel JE, Horner RA, Postel JR. Effects of phytoplankton blooms on salmon aquaculture in Puget Sound, Washington: initial research. Northwest Environ J. 1989;5:53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes L, Haywood A, Ballantine W, MacKenzie A. Algal blooms and climate anomalies in northeast New Zealand, August–December 1992. NZ J Mar Fresh Res. 1993;27:419–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sako Y, Otake I, Uchida A. The harmful algae Chattonella antiqua, C. marina and C. ovata (Raphidophyceae) are phylogenetically the same species. IXth International Conference on Harmful Algae; Tasmania. 2000. (abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer EF. Master’s thesis. University of North Carolina; Greensboro: 1997. A DNA assay to detect the toxic dinoflagellate Pfiesteria piscicida, and the application of a PCR based probe; p. 86. [Google Scholar]

- Schimada M, Murakami T, Imahayshi T, Ozaki H, Toyoshima T, Okaichi T. Effects on sea bloom Chattonella antiqua, on gill primary lamellae of the young yellowtail, Seriola quinqueradiata. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 1983;16:232–44. [Google Scholar]

- Scholin CA, Miller PE, Buck KR, Chavez FP, Harris P, Haydock P, Howard J, Cangelosi G. Detection and quantification of Pseudo-nitzschia australis in cultured and natural populations using LSU rRNA-targeted probes. Limnol Oceanogr. 1997;42:1265–72. [Google Scholar]

- Silva PC. Names of classes and families of living algae. Regnum Veg. 1980;103:1–156. [Google Scholar]

- Smayda T. Ecophysiology and bloom dynamics of Heterosigma akashiwo (Raphidophyceae) In: Anderson D, Cembella A, Hallegraeff G, editors. Physiological Ecology of Harmful Algal Blooms. Springer-Verlag; Berlin Heidelberg: 1998. pp. 113–31. [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (* and other methods). Version 4.0. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA 01375, USA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10:512–26. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Muto Y, Shimada M. Generation of superoxide anion radicals by the marine phytoplankton organism Chattonella antiqua. J Plankton Res. 1994;16:161–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tatusova TA, Madden TL. BLAST 2 Sequences, a new tool for comparing protein and nucleotide sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:247–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13575.x. Erratum FEMS Microbiol Lett. 177:187–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavaré S. Some probabilistic and statistical problems in the analysis of DNA sequences. In: Miura RM, editor. Some Mathematical Questions in Biology—DNA Sequence Analysis. American Mathematical Society; Providence, RI: 1986. pp. 57–86. [Google Scholar]

- Tengs T, Bowers HA, Ziman AP, Stoecker DK, Oldach DW. Genetic polymorphism in Gymnodinium galatheanum chloroplast DNA sequences and development of a molecular detection assay. Mol Ecol. 2001;10:515–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tengs T, Dahlberg OJ, Shalchian-Tabrizi K, Klaveness D, Rudi K, Delwiche CF, Jakobsen KS. Phylogenetic analyses indicate that the 19′ Hexanoyloxy-fucoxanthin-containing dinoflagellates have tertiary plastids of haptophyte origin. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:718–29. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomas C. Olisthodiscus luteus (Chrysophyceae) V. Its occurrence, abundance and dynamics in Narragansett Bay. J Phycol. 1980;16:157–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tomas C. The planktonic marine flagellates. In: Tomas C, editor. Identifying Marine Phytoplankton. Academic Press; New York: 1997. pp. 591–729. [Google Scholar]

- Tomas C. Blooms of potentially harmful Raphidophycean flagellates in Florida coastal waters. In: Reguera B, Blanco J, Fernandez M, Wyatt T, editors. Harmful Algae. Xunta de Galicia and Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO; Vigo, Spain: 1998. pp. 101–3. [Google Scholar]

- Toriumi S, Takano H. A new genus in the Chloromonadophyceae from Atsumi Bay, Japan. Bull Tokai Reg Fish Reg Lab. 1973;76:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrrell JV, Bergquist PR, Bergquist PL, Scholin CA. Detection and enumeration of Heterosigma akashiwo and Fibrocapsa japonica (Raphidophyceae) using rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. Phycologia. 2001;40:457–67. [Google Scholar]

- Vrieling E, Koeman R, Nagasaki K, Ishida Y, Peperzak L, Gieskes W, Veenhuis M. Chattonella and Fibrocapsa (Raphidophyceae) novel, potentially harmful red tide organisms in Dutch coastal waters. Neth J Sea Res. 1995;33:183–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wittwer CT, Herrmann MG, Moss AA, Rasmussen RP. Continuous fluorescence monitoring of rapid cycle DNA amplification. BioTechniques. 1997;22:130–8. doi: 10.2144/97221bi01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto C, Tanaka Y. Two species of harmful red tide plankton increased in Fukuoka Bay. Bull Fukuoka Fish Exp Stn. 1990;16:43–44. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Albright L, Yousif A. Oxygen-radical-mediated effects of the toxic phytoplankton Heterosigma carterae on juvenile rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. Dis Aquat Org. 1995;23:101–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zechman FW, Zimmer EA, Theriot EC. Use of ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacers for phylogenetic studies in diatoms. J Phycol. 1994;30:507–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zoller S, Lutzoni F. Slow algae, fast fungi: exceptionally high nucleotide substitution rate differences between lichenized fungi Omphalina and their symbiotic green algae Coccomyxa. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2003;29:629–40. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(03)00215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]