Abstract

Carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from the aerobic bacterium Oligotropha carboxidovorans catalyzes the oxidation of CO to CO2, yielding two electrons and two H+. The steady-state kinetics of the enzyme exhibit a pH optimum of 7.2 with a kcat of 93.3 s−1 and Km of 10.7 μm at 25 °C. kred for the reductive half-reaction agrees well with kcat and exhibits a similar pH optimum, indicating that the rate-limiting step of overall turnover is likely in the reductive half-reaction. No dependence on CO concentration was observed in the rapid reaction kinetics, however, suggesting that CO initially binds rapidly to the enzyme, possibly at the Cu(I) of the active site, prior to undergoing oxidation. A Mo(V) species that exhibits strong coupling to the copper of the active center (I = 3/2) has been characterized by EPR. The signal is further split when [13C]CO is used to generate it, demonstrating that substrate (or product) is a component of the signal-giving species. Finally, resonance Raman spectra of CODH reveal the presence of FAD, Fe/S clusters, and a [CuSMoO2] coordination in the active site, consistent with earlier x-ray absorption and crystallographic results.

Keywords: Enzymes/Dehydrogenase, Enzymes/Kinetics, Enzymes/Mechanisms, Enzymes/Metallo, Metals/Molybdenum, Protein/Metalloproteins

Introduction

Oligotropha carboxidovorans is a carboxydotrophic bacterium capable of aerobic, chemolithoautotrophic growth using CO as a sole source of carbon and energy (1, 2). The key enzyme involved in this facultative metabolism is an air-stable molybdenum-containing CO dehydrogenase (CODH)2 that catalyzes the oxidation of CO to CO2 according to Equations 1 and 2,

at pH 7. The reducing equivalents obtained from CO are transferred through an electron transfer chain to reduce molecular oxygen. CO2 thus generated is fixed non-photosynthetically via the pentose phosphate cycle (3, 4) with the following overall reaction stoichiometry in Equation 3.

|

This molybdenum-containing CODH is distinct from the highly O2-sensitive, Ni/Fe-containing CODH from obligate anaerobes such as Clostridum thermoaceticum or Methanosarcina barkerii (5). The Mo-containing CODH from O. carboxidovorans and Hydrogenophaga pseudoflava have been structurally characterized (6–10). Both are (αβγ)2 hexamers consisting of a small subunit (CoxS, 17.8 kDa) that has two [2Fe-2S] clusters, a medium subunit (CoxM, 30.2 kDa) that possesses FAD, and a large subunit (CoxL, 88.7 kDa) that has the active site molybdenum center (11, 12).

The Mo-containing CODH exhibits significant structural and sequence homologies to xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) and other molybdenum hydroxylases (13). Given the nature of the reaction catalyzed, however, CODH is of interest to gain a better understanding of the general activity of such molybdenum centers in biology. CODH is also of significant environmental interest as it is involved in the clearance of CO from the environment. Aerobic organisms such as O. carboxidovorans have been estimated to remove ∼2 × 108 metric tons of CO from the atmosphere annually (14).

Despite some initial confusion about the structure of the active site of CODH, the metal center has recently been established by high resolution x-ray crystallography (6, 7) and x-ray absorption spectroscopy (15) to be a binuclear [CuISMoVI] cluster, with the two metal atoms bridged by a μ-sulfido ligand. A reaction mechanism has been proposed involving the formation of an SCO2 intermediate, on the basis of the crystal structure of CODH in complex with the inhibitor n-butylisocyanide (7). However, computational studies suggest that such a thiocarbonate intermediate actually leads to a deep minimum on the potential energy surface, making CO2 release extremely difficult (16, 17). In addition, model compound studies suggest that CO oxidation could occur directly at the Cu(I) site, followed by electron transfer to Mo via the electronic delocalization of the Mo(μ-S)Cu moiety (18). Here, we report a study of the kinetic and spectroscopic properties of CODH to gain better insight into the nature of the active site and the mechanism by which CO is oxidized.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Carbon monoxide gas was obtained from Airgas at a purity of 99.5%. Isotopically enriched 98MoO3 (98Mo, 99%), 13CO (13C, 99%), and D2O (2H, 99.9%) were from Cambridge Isotope Lab, Inc. All other chemicals and reagents were obtained at the highest quality/purity available commercially and were used without further purification.

Bacteria Growth and Enzyme Purification

O. carboxydovorans (ATCC 49405) was cultivated at 30 °C, pH 7 in a 20-liter fermentor (BioFlo 415, New Brunswick) containing carboxydobacterium medium (9), with a gas mixture of 50% CO and 50% air. Cells were harvested in the late exponential phase (A436 >5), washed in 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.2), and stored at −80 °C. 98Mo-enriched CODH was obtained from O. carboxydovorans grown in 98MoO3-substituted medium.

CODH was purified using the procedure described by Meyer et al. (9, 19) with some modifications. All chromatography steps were carried out on an ÄKTA purifier (GE Healthcare) at 4 °C. About 60 g of thawed cells were suspended in 100 ml of 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.2 containing 1 mm EDTA, 0.2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 5 mg of DNase I, and disrupted with a French press (FA-078A, Thermo Electron Co.). Cell debris was removed by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2 h. The supernatant was loaded onto a Q-Sepharose column (40 cm × 2.6 cm) pre-equilibrated with 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, and eluted with seven column volumes of a linear gradient of 0–0.8 m NaCl in 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.2. Fractions possessing CODH activity (see below) were pooled, concentrated in an Amicon concentrator with 100-kDa MW cut-off, and passed through a Sephacryl S-300 column (40 cm × 2.6 cm) equilibrated (and eluted) with 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.2. Fractions were analyzed for both CODH activity and optical spectra, and only those of high activity and spectral purity (as judged by the absence of heme contaminants absorbing at 420 nm) were pooled and concentrated. Purified enzyme had an absorbance ratio of A280/A450 ∼5.5 and A450/A550 ∼2.9, and exhibited only three bands by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (7.5% stacking gel and 12% resolving gel) and a single band by non-denaturing PAGE (5% stacking gel and 7.5% resolving gel). The purified enzyme was stored in liquid nitrogen until needed.

Protein Estimation and Enzyme Assay

Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method (20). The extinction coefficient of purified enzyme at 450 nm was determined to be 70 mm−1 cm−1 for the (αβγ)2 hexamer, very close to the reported value of 72 mm−1 cm−1 (21, 22), which was used to calculate the concentration of enzyme.

CODH activity was monitored spectrophotometrically by the CO-dependent reduction of methylene blue (ϵ615 = 37.11 mm−1 cm−1) at 30 °C (23). A rubber septum-stoppered cuvette containing 50 μm methylene blue in 2 ml of 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.2 was bubbled with 100% CO for 10 min, and then 10 to 20 μl of anaerobic enzyme was injected via Hamilton syringe to initiate the reaction. The absorbance change was monitored at 615 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (HP 8452A). With one unit of activity defined as 1 μmol of CO oxidized per min at 30 °C, pure CODH exhibited a specific activity of 11.3 units/mg with methylene blue as the electron acceptor. Fully functional enzyme was earlier reported to have a specific activity of ∼24 units/mg using 1-phenyl-2-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium chloride (INT) and 1-methoxyphenazine methosulfate (MPMS) as the electron acceptors (7). In our hands, the INT/MPMS assay was >1.5 times faster than that with methylene blue under the same conditions, indicating that our enzyme preparation had comparable activity to that seen previously.

Fe, Mo, Cu, and Se contents were determined by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES, Optima 3000 DV, Perkin Elmer). Analysis of the results revealed 8.05 Fe, 1.82 Mo, and 1.69 Cu per mol of enzyme dimer. Mo and Cu are both essential for CODH activity (15, 22), and these results suggest that ∼15% of our CODH preparation is nonfunctional because of incomplete metal incorporation into apoprotein.

Reductive Titration with Sodium Dithionite

Reductive titrations of CODH were carried out in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.2 or 50 mm CAPS, 0.1 n NaCl, pH 10 at room temperature (22 °C). Enzyme, typically at a concentration of ∼10 μm, was made anaerobic in a sealed cuvette by repeated vacuum-flushing with argon. Sodium dithionite was dissolved in anaerobic buffer and titrated into the enzyme solution via a gas-tight syringe. The concentration of sodium dithionite in the stock solution was determined from the absorbance at 314 nm (ϵ = 8.0 mm−1 cm−1; Ref. 24).

Steady-state Kinetics

Steady-state kinetics was carried out under anaerobic conditions in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.2 at 25 °C using a stopped-flow spectrophotometer (Applied Photophysics). One syringe was loaded with anaerobic CODH (4.4 nm, after mixing), and the other with CO-flushed methylene blue (36 μm) in KH2PO4 buffer. The concentrations of CO were calculated based on a solubility of 1.0 mm at 1 atm and 25 °C (25). CO concentrations of 10–438 μm were obtained by mixing CO-flushed methylene blue with argon-flushed methylene blue. Absorbance changes were monitored at 615 nm, and the initial rates were plotted against CO concentration to obtain kcat and Km.

Rapid Reaction Kinetics

The reductive half-reaction of CODH (i.e., the reaction of Eox with CO under anaerobic conditions) was carried out by stopped-flow at 4 °C, over the pH range 5.5–10. Enzyme concentrations of 6–10 μm were mixed with various concentrations of CO, and the spectral change recorded over an appropriate period of time. The activation energy of CODH reduction by CO was determined at pH 7.2 and pH 10 from the temperature dependence of the reaction of enzyme with 1.0 mm CO over the temperature range 4 to 30 °C. The fast phases of the kinetic traces (see below) were fit to single exponentials using Pro-Kineticist software to obtain the observed rate constant (kobs).

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance and Resonance Raman Spectroscopy

EPR spectra were recorded using a Brüker Instruments ER 300 spectrometer equipped with an ER 035 m gaussmeter and a HP 5352B microwave frequency counter. Temperature was controlled at 150 K using a Brüker ER 4111VT liquid N2 cryostat. In experiments with substoichiometric CO, 200 μl of 50 μm anaerobic CODH in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.2 were added to a sealed EPR tube filled with argon. 10 μl of CO-flushed buffer (containing ∼23 μm CO) were then added and mixed by micropipetting. The solution was incubated for 10 s, then frozen in an acetone/liquid nitrogen bath. Other samples were prepared by reacting CODH with excess reductant (CO or sodium dithionite). A frozen water sample was used for background correction.

The EPR spectrum of reduced CODH in D2O was obtained by exchanging CODH into Tris-D2O buffer (50 mm, pD 7.6) by passage of enzyme through a Sephadex G-25 column equilibrated with that buffer, followed by reaction with excess CO. The EPR spectrum of enzyme reduced with 13CO was obtained simply by reaction with 13C-labeled CO (99%, Cambridge Isotope Lab) in 50 mm Tris, pH 8.0. Simulation of the EPR spectrum of CO-reduced 98Mo-labeled CODH was performed using EasySpin, a free software developed by Stefan Stoll at University of California, Davis.

Resonance Raman spectra were obtained using 514.5 nm excitation from a Coherent Innova 307 argon ion laser. Raman-scattered light was collected and dispersed using a single-stage spectrograph into a Princeton Instruments 1024 KTB, back-thinned, charge-coupled device detector. Calibration was performed using an external indene standard with reported band positions accurate to ±2 cm−1. Data were collected from the surface of a 30-μl sample (∼250 μm, in 50 mm HEPES buffer, pH 7.2) held at 30 K in a custom-built cold finger with a APD Cryogenics closed-cycle helium refrigerator. Samples were illuminated at 30 K for several hours prior to data collection to reduce background fluorescence. This procedure did not demonstrably change the resonance Raman line positions, but simply reduced the background.

RESULTS

Determination of the Extent of Functional CODH

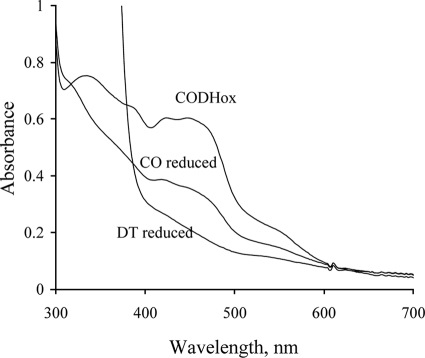

To assess the catalytic competence of the CODH used here, the extent of reduction of the enzyme by CO under anaerobic conditions was compared with that by dithionite (7). As shown in Fig. 1, exposure to CO for 1 min reduced the absorbance at 450 nm by ∼62% in comparison to the dithionite-reduced enzyme, depending on the preparation. Further incubation of the enzyme with CO (∼30 min) resulted in complete reduction, similar to the dithionite-reduced form. Such behavior has been observed with other Mo-containing enzymes, notably xanthine oxidoreductase (13), and has been ascribed to the presence of a certain amount of non-functional enzyme that becomes reduced by slow intermolecular electron transfer from the reduced functional enzyme (which subsequently reacts with more substrate to become fully reduced once again). In all experiments described here, the concentration of functional enzyme was used, correcting the total enzyme concentration for the amount of non-functional enzyme determined as described above.

FIGURE 1.

UV-vis absorption spectra of CODH. Spectra are for the oxidized form, CO-reduced form (1 min after mixing), and sodium dithionite-reduced form. The spectra were recorded in 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.2.

Titration of CODH with Sodium Dithionite

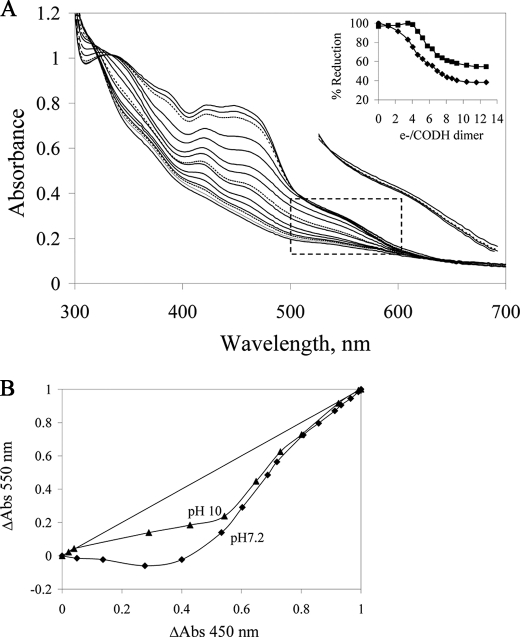

Fig. 2 shows reductive titrations of CODH with sodium dithionite as performed at pH 7.2 and pH 10. In total, approximately twelve reducing equivalents per CODH dimer were required to reach the end point (Fig. 2A, inset), consistent with the constitution of the protein redox-active centers. At pH 7.2, the first four reducing equivalents resulted in a significant decrease in absorbance at 450 nm and a slight increase above 550 nm, suggesting accumulation of the neutral FADH• semiquinone. Further titration resulted in a decrease in absorbance at both 450 nm and 550 nm, consistent with reduction of FADH• on to FADH2 along with additional reduction of the Fe/S clusters.

FIGURE 2.

Reductive titration of CODH with sodium dithionite under anaerobic conditions. A, spectral changes seen on titration of CODH with sodium dithionite in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.2. To the right of the main set of spectra is an enlargement of the boxed area for three spectra early in the titration, demonstrating a transient absorption increase with the earliest additions of reductant. The lowermost spectrum is that of oxidized enzyme, the dashed spectrum the enzyme after addition of the first aliquot of dithionite, and the uppermost spectrum that seen after addition of the second aliquot. Inset, absorbance changes at 450 nm (diamonds) and 550 nm (squares) versus reducing equivalents added per CODH dimer. B, plots of relative absorbance changes at 550 nm versus 450 nm at pH 7.2 (diamonds) and pH 10 (triangles).

The relative reduction potentials of FAD and Fe/S centers were gauged by plotting the fractional absorbance changes at 450 nm (where the FAD and Fe/S centers contribute approximately equally to the absorbance change observed upon reduction of the enzyme) versus 550 nm (where the Fe/S centers are responsible for the entirety of the spectral change) (26, 27). Fig. 2B shows plots of the fractional absorbance change at 550 nm versus that at 450 nm seen in reductive titrations at pH 7.2 and pH 10. The data at pH 7.2 resemble those seen previously with XOR (27). On the other hand, the pH 10 data continue to trend toward the lower right in the plot, whereas with XOR at pH 10 the plot trends strongly to the upper left (27). These results indicate that, particularly at high pH, the midpoint potential of FAD is substantially higher relative to the average of the potentials for the two Fe/S clusters in CODH (we estimate by at least 30 mV), whereas the reverse is true with XOR.

Steady-state Kinetics

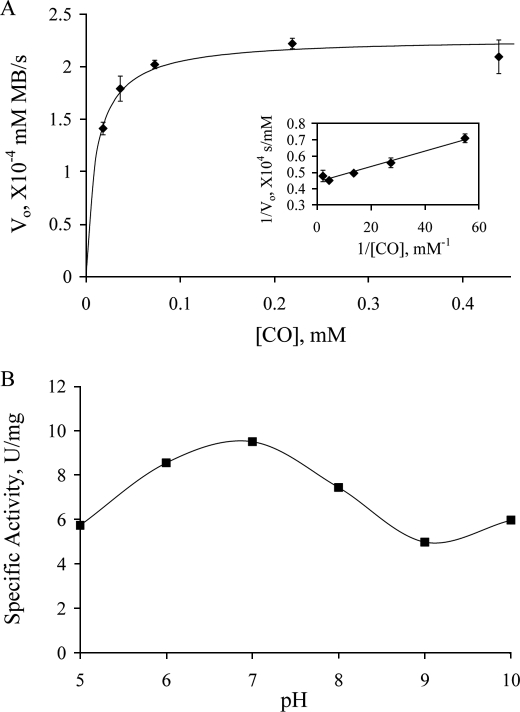

Fig. 3A shows the [CO] dependence of turnover at 25 °C using methylene blue as the electron acceptor. The data yield a kcat of 57.8 s−1 and Km of 10.7 μm, with a kcat/Km of 8.7 × 106 m−1 s−1. As shown in Fig. 1C, the enzyme used in the assay was ∼62% active (as judged by the functionality test described above), and the corrected turnover number for the fully functional enzyme is thus 93.3 s−1. This compares favorably with the value of 107 s−1 at 30 °C seen with INT as the electron acceptor (7), particularly when the 5 °C difference in temperature is taken into account.

FIGURE 3.

Steady-state kinetics of CODH reaction with CO using methylene blue as the electron acceptor. A, plot of initial rate (following the absorbance decrease at 615 nm upon reduction of methylene blue, after mixing 4.4 nm CODH with CO-dissolved (10–438 μm) methylene blue) as a function of [CO] in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, 25 °C. The solid line is the fit with the Michaelis-Menten equation using kinetic parameters obtained from the double-reciprocal plot (inset). B, the pH dependence of CODH activity, with specific activity given in units/mg, and 1 unit is 1 μmol of CO oxidized/min. Buffers used in the experiments are: MES pH 5.5, potassium phosphate pH 6 and 7, Tris pH 8, CHES pH 9, and CAPS pH 10, all at 50 mm.

CODH has a pH optimum of ∼7.2 (Fig. 3B), the pH at which most of the experiments here were carried out. It is noteworthy, however, that even at extremes in pH where the enzyme is only marginally stable CODH retains more than half of its maximal activity (Fig. 3B). The only modest loss of activity at these extreme pHs indicates that ionization of functional groups in the active site is not as critical to catalysis for CODH as has been found for XOR (30).

Reductive Half-reaction of CODH with CO

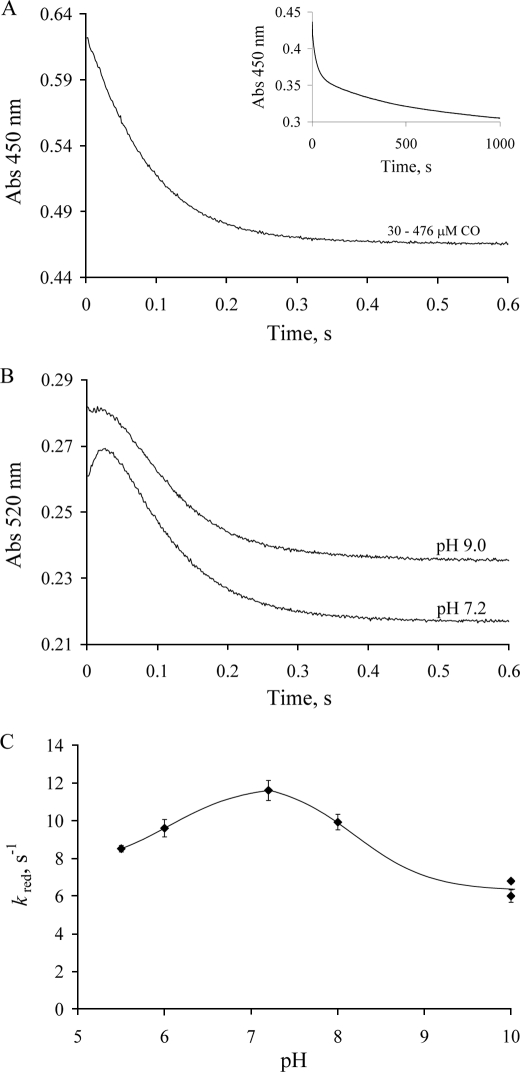

The rapid reaction kinetics of CODH with CO were determined at pH 7.2, 4 °C using stopped-flow spectrophotometry. Enzyme reduction was followed via the spectral change associated with reduction of the (functional) enzyme. Fig. 4A shows the time course seen for the absorption change at 450 nm. The reaction is distinctly biphasic, with a fast phase occurring in the first 500 ms, followed by a much slower reaction on a hundreds of seconds time scale (Fig. 4A, inset). By analogy to the kinetic behavior seen with XOR (31), the initial fast phase of the reaction is attributed to the reduction of the functional portion of the enzyme, after which a slow intermolecular transfer of reducing equivalents to the nonfunctional portion of the enzyme occurs (with subsequent re-reduction of the functional enzyme). The relative amplitudes of the fast and slow phases suggest that the enzyme used was ∼65% functional, in good agreement with the above spectrophotometric results. Surprisingly, at all pH values examined, no [CO] dependence of kobs for the fast phase of the reaction (hereafter referred to as kred) is observed over the concentration range 30 to 476 μm (Fig. 4A). At pH 7.2 and 4 °C, kred is determined to be 11.4 s−1. The rate constant for the slower phase of the reaction is found to be modestly pH-dependent. At higher pH the intermolecular electron transfer becomes somewhat faster (kslowapp = 0.046 and 0.070 s−1 at pH 7 and 9, respectively).

FIGURE 4.

Kinetics of CODH reduction by excess CO under anaerobic conditions. A, the kinetic trace seen at 450 nm upon mixing 12 μm CODH with 30–476 μm CO in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, 4 °C (transients at different CO concentrations are overlapping). Inset, the absorbance change over 1000 s. B, the kinetic traces at 520 nm at pH 7.2 and pH 9 (50 mm CHES). Curves at different CO concentrations (30–476 μm) are overlapping. C, the pH dependence of kred for CODH reduction at 4 °C.

Because kred exhibited no dependence on [CO], no Kd could be determined. This kinetic behavior resembles that seen with XOR and slow substrates, and is consistent with the initial rapid formation of a CuI·CO complex prior to oxidation of substrate, as has been suggested in the literature (16–18). The pH dependence of kred exhibits a maximum at pH 7.2 (Fig. 4C), in agreement with the above steady-state results and suggesting that the rate-limiting step of turnover is in the reductive half-reaction.

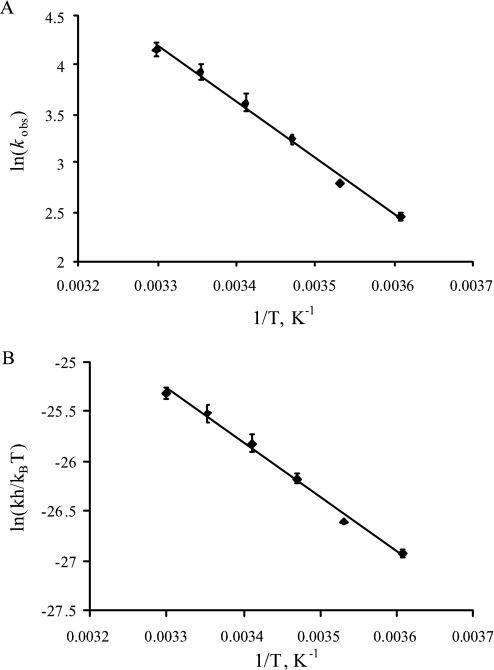

The temperature dependence of kred was investigated at pH 7.2 and pH 10 under CO-saturating conditions. Table 1 lists the activation parameters calculated from both an Arrhenius (Fig. 5A) and an Eyring (Fig. 5B) analysis of the data. The activation energy for the reaction of CODH with CO is 47.8 kJ/mol at pH 7.2 and 43.1 kJ/mol at pH 10.

TABLE 1.

Activation parameters of CODH reduction by CO at pH 7.2 and pH 10

The conditions are the same as in Fig. 5.

| pH 7.2 | pH 10 | |

|---|---|---|

| Ea, kJ/mol | 47.8 | 43.1 |

| ΔH≠, kJ/mol | 45.4 | 40.7 |

| ΔS≠, J/K·mol | −60.4 | −83.9 |

| ΔG, kJ/mol | 63.4 | 65.7 |

FIGURE 5.

The effect of temperature on the reduction of CODH by CO. Observed rate constants were determined at 4–30 °C after mixing 10 μm CODH with CO-saturated potassium phosphate, pH 7.2. An Arrhenius plot (A) or Erying's plot (B) was used to determine the activation energy of CODH reduction.

At 25 °C and pH 7.2, kred is 51.1 s−1, some 4-fold faster than at 4 °C. This value is approximately half the observed kcat of 93.3 s−1 from steady-state kinetics at the same temperature (after correction for nonfunctional enzyme). This disparity has been accounted for previously by Olson et al. (26) in the case of XOR, and is due to the fact that under the present reaction conditions three successive substrate molecules must react with enzyme to achieve complete reduction. The observed kred has been shown to underestimate the actual rate constant for an individual step by a factor of two. Taking this into consideration, kred as determined from the rapid reaction kinetics (51 s−1) agrees well with the steady-state kcat (93 s−1). In conjunction with the similar pH dependence seen for the steady-state and reductive half-reaction kinetics, this indicates that the latter is principally rate-limiting in CODH catalysis.

At pH 7.2 and 4 °C, the kinetic transients at 520 nm exhibit a small initial increase followed by a subsequent decrease (Fig. 4B, lower curve). The amplitude of the first phase is very small, with an apparent rate constant estimated to be 65 s−1. For the second phase kobs is 10.2 s−1, in good agreement with the value of 11.4 s−1 seen at 450 nm. The transient absorbance increase is pH-dependent. At pH 5.5 the initial increase becomes more pronounced; but at pH 9 or 10, only a lag phase is observed, with no transient absorbance increase (Fig. 4B, upper curve). In combination with the reductive titration data discussed above, we conclude that the transient absorption increase is due to FADH• accumulating in partially reduced enzyme forms (CODH2e−, CODH4e−) generated early in the course of the reaction with CO.

Reduction of CODH with Substoichiometric CO

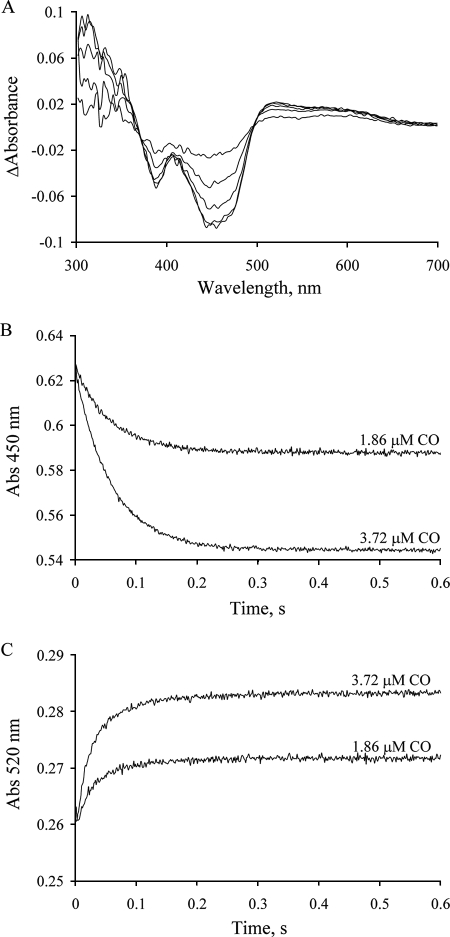

Reaction of enzyme with substoichiometric concentrations of substrate has proven useful in simplifying the observed kinetics of other systems, because under these conditions no enzyme molecule is likely to react with more than one equivalent of substrate (29). Fig. 6A shows the difference spectra (relative to oxidized enzyme) seen in the course of the reaction of 12.5 μm CODH with either 1.86 or 3.72 μm CO in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.2. They exhibit well-maintained isosbestic points at 370 and 496 nm. The absorbance at 450 nm decreases monotonically and in proportion to the substrate concentration (Fig. 6B). The observed rate constant is 16.7 s−1, slightly greater than that with excess CO. Above 520 nm the absorbance increases (kobs = 29.5 s−1) and does not subsequently decrease as is seen in the reaction with excess CO, again reflecting significant accumulation of FADH• in the reaction.

FIGURE 6.

Kinetics of reduction of CODH with substoichiometric CO under anaerobic conditions. A, difference spectra seen in the course of the reaction of 12 μm CODH with 3.72 μm CO (at 0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 1 s after mixing) in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, 4 °C. All absorbance changes are given relative to the oxidized enzyme. B and C, kinetic transients observed at 450 nm and 520 nm, respectively, upon mixing 12 μm CODH with 3.72 or 1.86 μm CO in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, 4 °C.

EPR and Resonance Raman Studies of CODH

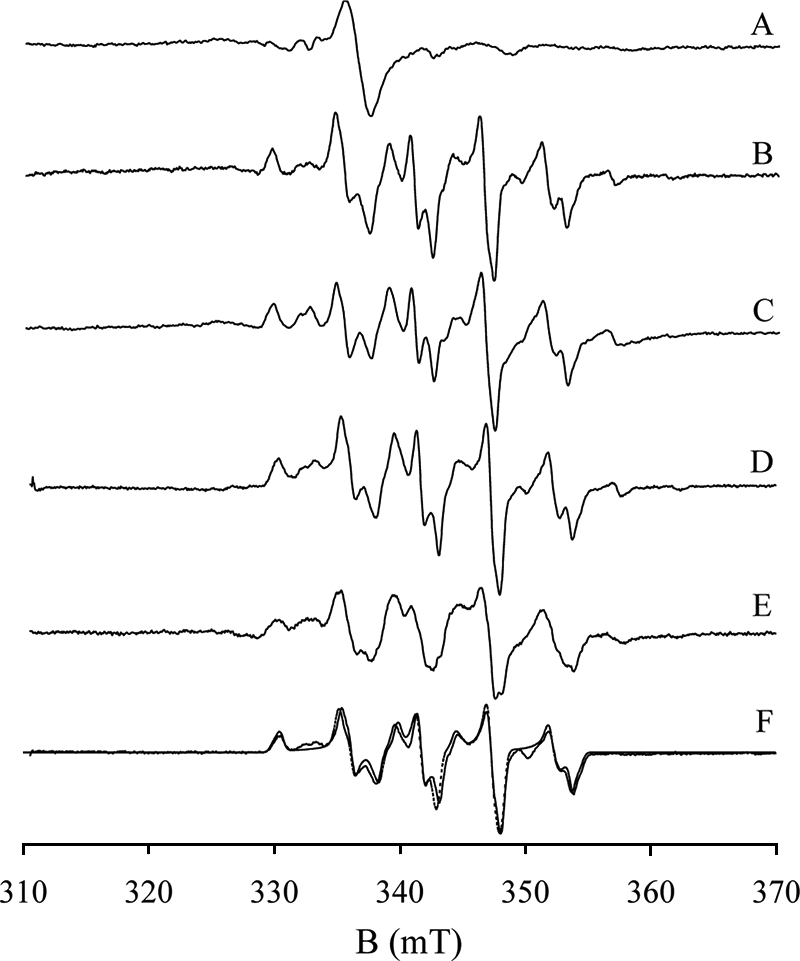

To confirm that the neutral FADH• semiquinone is indeed formed to a significant degree upon partial reduction of the enzyme, we examined the enzyme by EPR spectroscopy. The spectrum of CODH reduced with limiting CO yields an isotropic radical signal centered at g ∼2.003 with a peak-to-trough line width of 20 G (Fig. 7A), indicative of the neutral flavin semiquinone. The integrated spin intensity of this isotropic signal, calibrated using a Cu-EDTA standard, accounted for ∼20% of FADH• accumulation.

FIGURE 7.

EPR spectra of reduced CODH. Samples were prepared as follows (all in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH/D 7.2): A, 50 μm CODH reduced with 23 μm CO for 10 s at 4 °C. The peak-to-trough line width of the isotropic radical signal is 20 Gauss. B, CODH reduced with excess CO under the same buffer conditions; C, CODH reduced sodium dithionite; D, CODH reduced with CO in Tris-D2O buffer, pH 8; E, CODH reduced with 13CO; F, 98Mo-enriched CODH reduced with CO (solid line), and simulation of the spectrum (dashed line) with parameters g1,2,3 = 2.0010, 1.9604, 1.9549, A1,2,3 = 117, 164, 132 MHz, α = 0, β = 40, γ = 40. The EPR instrument settings were: 9.455 GHz microwave frequency; 10 milliwatt microwave power; 5 Gauss modulation amplitude; 150 K.

Functional CODH is EPR silent in the air-oxidized state, implying that the copper ion in the active site is present as Cu(I). Inactive CODH, by contrast, shows a small resting Mo(V) signal resembling the “Resting I” and “Inhibited” signals seen with XOR (22, 32) that is presumably because of enzyme that has lost the catalytically essential copper and bridging sulfur. In our hands, the EPR spectra of CO- or dithionite-reduced CODH (Fig. 7, B and C) were essentially identical, but differed in detail to previously published spectra (the latter appearing to arise from more than one paramagnetic species; Ref. 22). Our spectrum has well-resolved structure suggestive of hyperfine interactions with both Mo and Cu nuclei. The small satellite features attributable to the combined 25% natural abundance of 95Mo and 97Mo (18), at 3275, 3575, and 3625 G, are lost in 98Mo-labeled enzyme (Fig. 7 F, solid line). The quartet features arising from the I = 3/2 nuclei of 63,65Cu are readily evident in the spectrum, and are readily reproduced in simulations (Fig. 7F, dashed line). The parameters from this simulation are g1,2,3 = 2.0010, 1.9604, 1.9549 and A1,2,3 = 117, 164, 132 MHz, with Euler angles α = 0, β = 40, γ = 40. The high quality of the simulation demonstrates that the EPR signal in question arises from a single paramagnetic species.

CODH reduced with CO in D2O shows the identical EPR spectrum (Fig. 7D) as in H2O, with no discernible narrowing even of the observed linewidths. The expected hyperfine splitting for an equatorial Mo-OH in systems analogous to that seen in CO dehydrogenase (that is, those having a square pyramidal coordination geometry for the molybdenum with an apical Mo=O group) is in the range 3–14 G, and splittings of this magnitude yield demonstrable doublet structure in the EPR signal. In the “Rapid type 1” signal of xanthine oxidase, for example, a doublet of doublets is observed due to proton hyperfine splitting from the equatorial Mo-OH and Mo-SH ligands of 3 and 14 G, respectively. In the “Rapid type 2” signal of this enzyme, the Mo-OH splitting grows to 13 G, yielding a 1:2:1 triplet due to two approximately equally strongly coupled protons. As demonstrated in the classic work of Bray and coworkers (33, 34), the Mo-OH and Mo-SH protons of the “rapid” signals of xanthine oxidase are solvent-exchangeable, and substitution into D2O collapses the hyperfine structure to give a single line for each principal g-value of the signals.3 The complexity of the EPR signal seen here with CO dehydrogenase notwithstanding, its linewidths (5–6 G) are comparable to those seen for the signals observed with xanthine oxidase and loss of proton splitting even as weak as 3 G would have led to a demonstrable narrowing of the features upon substitution into D2O. We conclude that the EPR-active Mo(V) state has no equatorial Mo-OH, and that the equatorial position is occupied by a fully deprotonated Mo=O group. This being the case, it is very unlikely that there will be one in the more oxidized Mo(VI) state of the oxidized enzyme. The equatorial oxygen ligand of Mo in oxidized CODH has been assigned as either a Mo-OH group on the basis of the high resolution crystal structure (7) or a second Mo=O from x-ray absorption studies (15). Our EPR result is consistent with the XAS work indicating a MoO2 core in the active site of oxidized enzyme.

In a final EPR experiment, the spectrum of CODH reduced with 13C-labeled CO (Fig. 7E) was found to exhibit significant line-broadening, even (weak) doublet structure ∼3425 and 3470 G. The splitting of Mo(V) signal by 13C-labeled CO clearly demonstrates that CO/CO2 is present in the signal-giving species of substrate-reduced enzyme.

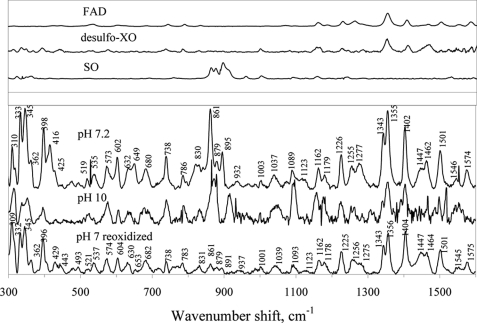

The resonance Raman (rR) spectra of oxidized CODH at pH 7 and 10 (Fig. 8) exhibit features attributable to FAD (1300–1400 cm−1), Fe/S (300–350 cm−1), and two distinct bands at 895 and 861 cm−1, which we ascribe to the symmetric (vs) and antisymmetric (vas) Mo-Ooxo stretching modes, respectively, arising from a MoO2 core. These vibrational frequencies are similar to those previously observed in sulfite oxidase: vs(Mo-Ooxo) = 896 cm−1 and vas (Mo=O) = 864 cm−1 (35, 36), and in Mo(VI) model compounds: vs(Mo-Ooxo) from 858 to 938 cm−1, and vas(Mo-Ooxo) from 835 to 898 cm−1 (37). The present rR results are thus also consistent with a CuSMoO2 core in the oxidized enzyme (15).

FIGURE 8.

Resonance Raman spectra of oxidized CODH at pH 7.2 and pH 10, CODH reduced with CO and then reoxidized in air at pH 7.2. Spectra were obtained at 30 K using 514.5 nm excitation. Resonance Raman spectra of FAD, desulfo-xanthine oxidase, and plant sulfite oxidase, which is known to possess a MoO2 core [26], are shown in the upper panel for comparison.

A CODH sample reduced with CO and then reoxidized in air reveals an rR spectrum similar to that of desulfo-XO (Fig. 8, upper panel), indicating that handling of the protein in this way results in loss of the Mo-S-Cu bond, yielding a catalytically inactive MoO3 core. This result is consistent with the previously observed inactivation of CODH in the presence of both CO and O2 (4).

CONCLUSIONS

In the present work, we have examined the oxidation of CO by CODH using kinetic and spectroscopic methods. The enzyme exhibits a steady-state kcat of 93.3 s−1, similar to previous work (7). On the other hand, the observed rate constant kred for the reductive-half reaction of CODH with CO is 51.1 s−1 at 25 °C and pH 7.2, reflecting an intrinsic kred of 102 s−1 that is in good agreement with the steady-state kcat of 93.3 s−1. The absence of any dependence of kred on [CO] is consistent with the rapid formation of a complex of CO with enzyme prior to substrate oxidation. Previous computational and model compound studies have in fact suggested that the first step of the catalytic cycle is CO binding to the Cu(I) of the active site (17, 18). The good agreement between steady-state and reductive half-reaction kinetics, as well as their similar pH dependences suggest that the reductive-half reaction is the rate-limiting step in CODH catalysis.

Significant FADH• accumulation is seen in the course of reductive titrations of CODH with sodium dithionite, with ∼20% of FADH• accumulating at maximum on the basis of EPR integration. Transient accumulation of FADH•, as manifested in an absorption increase above 550 nm, is also observed in the course of the reaction of CODH with CO at pH 7.2 and below. The results indicate that the FAD of CODH has a significantly higher reduction potential (∼30 mV) relative to the [2Fe-2S] clusters of the enzyme than is seen in XOR.

Our results indicate that the EPR signal shown in Fig. 7, B–F arises from a single Mo(V) species (g1,2,3 = 2.0010, 1.9604, 1.9549) exhibiting strong coupling to copper (A1,2,3 = 117, 164, 132 MHz), as well as weaker coupling to the carbon of CO. No proton coupling is evident, as reflected in the absence of any effect when the sample is prepared in D2O, indicating that neither the paramagnetic Mo(V) species nor the Mo(VI) state of oxidized enzyme is likely to possess a protonated Mo-OH group. The molybdenum is thus best formulated as having a MoO2 core rather than MoO(OH), a conclusion consistent with our resonance Raman results, with bands evident at 895 and 861 cm−1 that are assigned to symmetric and antisymmetric MoO2 stretching modes, respectively. This interpretation is consistent with previous x-ray absorption spectroscopic results with CODH (15).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Holger Dobbek and Ortwin Meyer for helpful discussions. We also thank Woody Smith from Department of Environmental Sciences at University of California, Riverside for ICP measurements.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM 075036.

Substitution of the 2H nucleus (I = 1) for the 1H (I = ½) results in loss of observable hyperfine structure because the nuclear moment of 2H is less than 1/3 that of 1H, with the result that the 1:1:1 triplet expected a priori is not resolved.

- CODH

- carbon monoxide dehydrogenase

- XOR

- xanthine oxidoreductase

- ICP-AES

- inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer

- EPR

- electron paramagnetic resonance

- rR

- resonance Raman

- CAPS

- 3-(cyclohexylamino)propanesulfonic acid

- MES

- 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid

- CHES

- 2-(cyclohexylamino)ethanesulfonic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meyer O., Schlegel H. G. (1978) Arch. Microbiol. 118, 35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer O., Schlegel H. G. (1980) J. Bacteriol. 141, 74–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cypionka H., Meyer O. (1983) J. Bacteriol. 156, 1178–1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer O., Gremer L., Ferner R., Ferner M., Dobbek H., Gnida M., Meyer-Klaucke W., Huber R. (2000) Biol. Chem. 381, 865–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ragsdale S. W., Kumar M. (1996) Chem. Rev. 96, 2515–2540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobbek H., Gremer L., Meyer O., Huber R. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 8884–8889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobbek H., Gremer L., Kiefersauer R., Huber R., Meyer O. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 15971–15976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hänzelmann P., Dobbek H., Gremer L., Huber R., Meyer O. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 301, 1221–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gremer L., Kellner S., Dobbek H., Huber R., Meyer O. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 1864–1872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang B. S., Kim Y. M. (1999) J. Bacteriol. 181, 5581–5590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schübel U., Kraut M., Mörsdorf G., Meyer O. (1995) J. Bacteriol. 177, 2197–2203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santiago B., Schübel U., Egelseer C., Meyer O. (1999) Gene 236, 115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hille R. (1996) Chem. Rev. 96, 2757–2816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moersdorf G., Frunzke K., Gadkari D., Meyer O. (1992) Biodegradation 3, 61–82 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gnida M., Ferner R., Gremer L., Meyer O., Meyer-Klaucke W. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 222–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofmann M., Kassube J. K., Graf T. (2005) J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 10, 490–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siegbahn P. E., Shestakov A. F. (2005) J. Comput. Chem. 26, 888–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gourlay C., Nielsen D. J., White J. M., Knottenbelt S. Z., Kirk M. L., Young C. G. (2006) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 2164–2165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hänzelmann P., Meyer O. (1998) Eur. J. Biochem. 255, 755–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradford M. M. (1976) Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer O., Rajagopalan K. V. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259, 5612–5617 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Resch M., Dobbek H., Meyer O. (2005) J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 10, 518–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraut M., Hugendieck I., Herwig S., Meyer O. (1989) Arch. Microbiol. 152, 335–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Lorio (1981) Methods Enzymol. 76, 58 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dean J. A. (1972) Lange's Handbook of Chemistry, 12th Ed., McGraw-Hill, New York [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olson J. S., Ballou D. P., Palmer G., Massey V. (1974) J. Biol. Chem. 249, 4363–4382 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hille R. (1991) Biochemistry 30, 8522–8529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deleted in proof

- 29.McWhirter R. B., Hille R. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 23724–23731 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim J. H., Ryan M. G., Knaut H., Hille R. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 6771–6780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leimkühler S., Stoker A. L., Igarashi K., Nishino T., Hille R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 40437–40444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bray R. C., George G. N., Lange R., Meyer O. (1983) Biochem. J. 211, 687–694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pick F. M., Bray R. C. (1969) Biochem. J. 114, 735–742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bray R. C., Barber M. J., Lowe D. J. (1978) Biochem. J. 171, 653–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hemann C., Hood B. L., Fulton M., Hänsch R., Schwarz G., Mendel R. R., Kirk M. L., Hille R. (2005) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 16567–16577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garton S. D., Garrett R. M., Rajagopalan K. V., Johnson M. K. (1997) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 2590–2591 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson M. K. (2004) in Diothiolene Chemistry: Progress in Inorganic Chemistry (Stiefel E. I. ed) Vol. 52, pp. 213–266, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ [Google Scholar]