Abstract

The heptapeptide-nucleotide microcin C (McC) is a potent inhibitor of enteric bacteria growth. McC is excreted from producing cells by the MccC transporter. The residual McC that remains in the producing cell can be processed by cellular aminopeptidases with the release of a non-hydrolyzable aspartyl-adenylate, a strong inhibitor of aspartyl-tRNA synthetase. Accumulation of processed McC inside producing cells should therefore lead to translation inhibition and cessation of growth. Here, we show that a product of another gene of the McC biosynthetic cluster, mccE, acetylates processed McC and converts it into a non-toxic compound. MccE also makes Escherichia coli resistant to albomycin, a Trojan horse inhibitor unrelated to McC that, upon processing, gives rise to a serine coupled to a thioxylofuranosyl pyrimidine, an inhibitor of seryl-tRNA synthetase. We speculate that MccE and related cellular acetyltransferases of the Rim family may detoxify various aminoacyl-nucleotides, either exogenous or those generated inside the cell.

Keywords: Enzymes, Nucleoside/Nucleotide/Analogs, Translation/Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase, Acetyl-Coenzyme A, Antibiotics, RimL, Acetyltransferase, Albomycin, Microcin, Microcin Resistance

Introduction

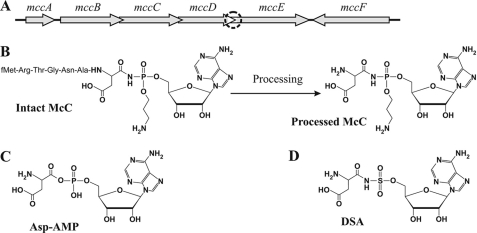

Microcins are a class of antibacterial agents produced by Escherichia coli and its close relatives (1, 2). Microcins are produced from ribosomally synthesized peptide precursors. The molecular mass of microcins is below 10 kDa. Some microcin precursors are heavily modified by dedicated maturation enzymes (3, 4). One post-translationally modified microcin, microcin C (McC), is a heptapeptide with covalently attached C-terminal modified adenosine monophosphate (5, 6). McC is produced by E. coli cells harboring plasmids carrying the mccABCDE operon (Fig. 1A), which encodes the McC precursor, enzymes necessary for McC synthesis, and proteins that make the cell immune to produced McC. The peptide moiety of McC is encoded by 21-bp-long mccA, the shortest bacterial gene known (7, 8). Mature McC (Fig. 1B) has a molecular mass of 1178 Da and contains a formylated N-terminal methionine, a C-terminal aspartate instead of asparagine encoded by the mccA gene, and an AMP residue attached to the α-carboxyl group of the aspartate through an N-acyl phosphoramidate linkage. The phosphate group is additionally modified by a propylamine group.

FIGURE 1.

Microcin C and the mechanism of its action. A, genetic organization of McC biosynthetic operon mcc is schematically shown. The uncertain region between the end of mccD and the previously annotated start points of mccE is highlighted by a circle (also see Introduction and Fig. 3). B, the structures of intact McC and processed form of the antibiotic. C, the structure of aspartyl-adenylate, an intermediate of the reaction catalyzed by AspRS. D, the structure of DSA, an inhibitor of AspRS.

Once inside sensitive cells, McC is processed, and the product of such processing (Fig. 1B), a non-hydrolyzable analog of aspartyl-adenylate, an intermediate of the reaction catalyzed by aspartyl-tRNA synthetase (Fig. 1C), inhibits translation by preventing the synthesis of aminoacylated tRNAAsp by aspartyl-tRNA synthetase (AspRS)3 (9). McC processing involves deformylation of the N-terminal Met residue by peptide deformylase, followed by degradation of the peptide moiety by any one of the three broad specificity aminopeptidases, peptidases A, B, and N (10). Although unprocessed McC has no effect on the aminoacylation reaction, processed McC has no effect on the growth of sensitive cells at concentrations at which intact McC efficiently inhibits growth (9). Thus, McC is a Trojan horse inhibitor (9, 11); the peptide moiety is required for the entry of unprocessed McC into sensitive cells, where it must be processed by peptidases to release the inhibitory aminoacyl-nucleotide part of the drug. Because AspRS of McC-producing cells is readily inhibited by processed McC, special mechanisms must exist to ensure that McC production is not deleterious to the producing cell. One such mechanism involves MccC, an export pump that specifically removes McC from the producing cell into the medium. Disruption of mccC in the context of McC-producing plasmid is toxic to the producing cell (8). On the other hand, expression of mccC alone provides McC resistance to McC-sensitive E. coli cells, indicating that MccC can provide resistance to both internally produced and exogenously added McC.

McC-producing E. coli cells remain fully viable. This and the Trojan horse mechanism of McC action suggest that MccC could not be the only line of defense against internally produced McC because inevitable accumulation of processed McC in the producing cell cytoplasm should ultimately lead to the inhibition of translation and cell death. Earlier studies indicated that disruption of the mccE gene in the context of McC-producing plasmid makes cells harboring such plasmid very sick (8), possibly indicating that MccE contributes to McC resistance. In this work, we prove this conjecture and define the molecular mechanism by which MccE contributes to McC immunity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Molecular Cloning and Recombinant Protein Purification

The mccE gene and its fragments encoding MccENTD and MccECTD were amplified by PCR using pUHAB plasmid (12) as a template. The upstream primers contained an engineered NdeI site, whereas downstream primers contained a HindIII site that was later used for cloning. Sequences of primers used for amplification are available from the authors upon request. The PCR products were first cloned into pGemT vector (Invitrogen). Recombinant plasmids were selected and treated with NdeI-HindIII, and mccE fragments were cloned into appropriately treated pET28 expression vectors. Site-directed mutagenesis to obtain S553A and E572A substitutions in MccE was carried out by PCR mutagenesis of plasmid pET28-mccECTD using appropriate oligonucleotides following the general procedure described elsewhere (12).

Overexpression of MccE, MccENTD, MccECTD, and MccECTD(S553A/E572A) was carried out in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells that also carried a compatible pG-KJE8 (dnaK-dnaJ-grgE, groES-groEL) plasmid (Takara BIO Inc., Japan). Cells were grown at 30 °C in 300 ml of LB supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (40 μg/ml). Overexpression of plasmid-borne mccE was induced by the addition of 0.1 mm IPTG to the medium. l-Arabinose (4 mg/ml) and tetracycline (10 ng/ml) were also added to induce chaperone synthesis. Growth was continued in the presence of inducers for 18 h.

The resistance of cells with different plasmids to various compounds on plates was tested by placing 5-μl drops of McC (300 μm), aspartyl-sulfamoyl-adenosine (DSA; 6 mm), leucyl-sulfamoyl-adenosine (LSA; 3 mm), and tetracycline (500 μg/ml) solutions on the surface of LB plates overlaid with 4.5 ml of soft (0.75%) LB agar seeded with 0.1–0.15 ml of induced overnight (A600 ∼2.5) bacterial cultures to be tested. Soft agar used for overlay contained 0.1 mm IPTG.

Albomycin sensitivity was tested in liquid cultures using E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pET28 vector-based plasmids expressing MccE, wild-type or mutant MccECTD, or cells carrying the pET28 vector alone. Exponentially growing uninduced cultures were diluted with LB medium to A600 = 0.1, and 0.1 μg/ml albomycin was added (zero time point). Because the addition of IPTG was found to affect the growth of some cells, IPTG induction was not used in this experiment. Cell growth was monitored in the presence of 0.1 μg/ml albomycin. Cultures that did not receive albomycin served as controls.

To purify recombinant MccE or its domains, cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 6 ml of buffer A (20 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, 0.05 m NaCl) containing 1 mg/ml lysozyme. After a 1-h incubation on ice, cells were disrupted by sonication, and cell debris was removed by centrifugation. The supernatant was loaded on a 1-ml chelating HiTrap column (GE Healthcare) charged with Ni2+ according to the manufacturer's instructions. The column was washed with buffer A containing 40 mm imidazole, and bound protein was eluted with the same buffer containing 250 mm imidazole. The resulting proteins were ∼95% pure as judged by Coomassie staining of SDS gels. Recombinant proteins were concentrated by ultrafiltration, glycerol was added to a final concentration 50%, and samples were stored at −20 °C until further use.

Acetyltransferase Activity Assays

Acetyltransferase activity was measured using a method described by Bode et al. (13). 50 μl of reaction mixtures contained 100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mm acetyl-CoA or malonyl-CoA, 110 μm substrates (McC, aminoacyl-sulfamoyl-adenosine (AaSAa), or free amino acids) and a 45 pm concentration of MccE or its domains. Reactions proceeded at room temperature and were terminated by the addition of 150 μl of ethanol and 5,5-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoate) (0.2 mm). 5,5-Dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoate) reacts with newly formed free CoA and leads to the increase in A412 as described by Bode et al. (13). To measure the reaction rate (pmol of substrate acetylated/min of reaction), the reactions were stopped at different times, and the amount of CoA formed was determined. The amounts of acetylated compounds formed were assumed to be equal to those of free CoA. The absolute amounts (pmol) of free CoA reported by A412 measurements were determined using a standard curve obtained with free CoA purchased from Sigma.

Chemical Characterization of Acetylation Products

Liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry was used to analyze the acetylation reaction products. The samples were redissolved in 20 μl of methanol/water (1:1), and 100 nl of this mixture was injected directly onto the HPLC system (CapLC, Waters (Milford, MA)). The separation was performed on a hydrophilic interaction column (Grace Alltima HP Hilic, 150 mm × 300 μm (Deerfield, IL)) thermostated at 40 °C. Acetonitrile (HPLC gradient grade; Fisher) was used as organic phase, and 25 mm ammonium formate (pH 6.3) was used as aqueous phase. Flow rate was 5 μl/min, the gradient started at 86% acetonitrile, and the components were eluted by increasing the aqueous phase by 4%/min for 15 min. Electrospray mass spectra were recorded in negative ionization mode on an orthogonal acceleration quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Q-Tof 2, Micromass (Manchester, UK)). Electrospray capillary voltage was set to −2850 V. Mass spectra (scan time, 0.9 s; interscan delay, 0.1 s; m/z range, 200–550) and fragment ion spectra (scan time, 1.9 s; interscan delay, 0.1 s; m/z range, 50–550) were recorded alternatingly. Argon was used as collision gas, and the collision energy was set to 10 eV, 20 eV, and 15 eV for DSA, LSA, and ESA, respectively. The collision cell voltages were optimized based on the fragmentation pattern of the compounds in such a way that the fragments as well as the precursor ion could be observed simultaneously.

Preparation of E. coli S30 Cell Extracts

E. coli cells were grown to A600 of ∼0.8 in LB medium. Cells were collected by centrifugation and washed with 40 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 10 mm Mg(OAc)2, 50 mm KOAc, 0.1 mm EDTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol. The cell pellet was resuspended in an equal volume of the same buffer and disrupted using a French press (pressure 1000 bars). The lysate was next centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 30 min. Then supernatant was aliquoted and either directly used in tRNA aminoacylation reactions or stored at −80 °C until further use.

tRNA Aminoacylation Reaction

Aminoacylation reaction was carried out according to the method described by Metlitskaya et al. (9) with some modifications. To 1 μl of solution containing an inhibitor being tested, 3 μl of E. coli S30 extract was added. Next, 16 μl of aminoacylation mixture (30 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 5 g/liter bulk E. coli tRNA, 3 mm ATP, 30 mm KCl, 8 mm MgCl2, and a 40 μm concentration of the desired labeled amino acid) was added, and reactions were incubated at room temperature for 5 min. The reactions were terminated by the addition of cold 10% trichloroacetic acid, and precipitated reaction products were collected on Whatman 3MM paper filters. After thorough washing with cold 10% trichloroacetic acid, the filters were washed twice with acetone and dried on a heating plate. Following the addition of scintillation liquid, the amount of radioactivity was determined in a scintillation counter.

RESULTS

Extracts of Cells Producing McC Contain an Activity That Relieves McC Inhibition

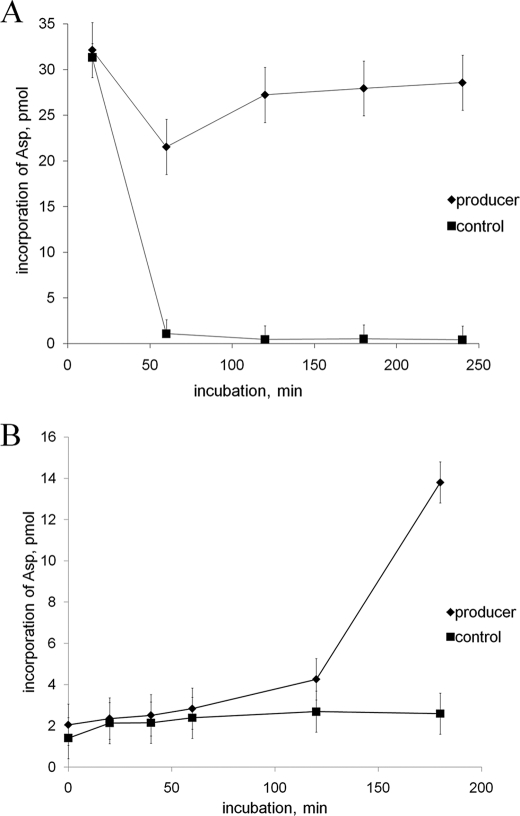

In the experiment shown in Fig. 2A, McC was added to S30 extracts prepared from E. coli cells with or without the McC-producing plasmid pUHAB (12), and after a 50-min incubation, which is a sufficient time for McC processing by endogenous peptidases (10), AspRS activity was measured. As can be seen, the addition of McC to extracts of cells that did not contain pUHAB led to complete and irreversible inhibition of tRNAAsp aminoacylation by AspRS. In contrast, the inhibition of AspRS activity in extracts of cells carrying pUHAB was incomplete after 50 min, and the activity gradually recovered upon longer incubations. In the experiment shown in Fig. 2B, McC was incubated with S30 extract prepared from cells lacking pUHAB to allow complete processing and combined with fresh extracts prepared from cells with or without pUHAB, and AspRS activity was monitored over time. As can be seen, in extracts without pUHAB, AspRS activity remained constant and low at all time points tested. In contrast, in extracts containing pUHAB, the AspRS activity gradually recovered with time. The result thus indicates that in extracts of McC-producing cells, there exists an activity that detoxifies processed McC.

FIGURE 2.

Extracts of cells producing McC contain an activity that detoxifies processed McC. A, AspRS-catalyzed aminoacylation of tRNAAsp in S30 extracts prepared from E. coli cells with (producer) or without (control) McC-producing plasmid pUHAB. Extracts were supplied with intact McC, and tRNAAsp aminoacylation reactions were carried out at the time points indicated. B, processed McC was incubated with E. coli S30 extracts prepared from cells with or without the pUHAB plasmid, and tRNAAsp aminoacylation reactions were carried out at the time points indicated. Error bars show standard deviations of measurements obtained in at least three independent experiments.

The Product of the mccE Gene Is Necessary for Stable Maintenance of Derepressed mcc Operon

In previous work, we showed that wild-type E. coli cells transformed with a plasmid carrying the mccABCDE operon with a stop codon introduced in the mccE gene do not produce McC (14). In contrast, pepA− pepB− pepN− cells harboring such a plasmid produced McC well (14) (recall that pepA− pepB− pepN− cells are unable to process McC). Both types of cells produced McC when carrying a plasmid with intact mccABCDE operon. The reason(s) for this difference remained unknown. We observed that although both plasmids could be introduced into either host with high efficiency, the mutant, mccE−, plasmid but not the wild type, mccE+, plasmid was rapidly lost from the wild-type cells when the culture reached stationary phase, a condition when McC synthesis is induced (15, 16). In contrast, both plasmids were stably maintained in pepA− pepB− pepN− cells (data not shown). The results thus indicate that the product of mccE is necessary for stable maintenance of derepressed mccABCDE operon at conditions when processing of McC by aminopeptidases can occur.

McC-producing cells must contain a certain steady-state concentration of McC in their cytoplasm. In the wild-type but not in pepA− pepB− pepN− cells, some intracellular McC should inevitably get processed, leading to AspRS inhibition and cessation of protein synthesis. Experiments presented in Fig. 2 demonstrate that cytoplasmic extracts prepared from McC-producing cells contain an activity that inactivates processed McC. Based on the observation that mccE is required for stable maintenance of pUHAB plasmid at conditions of mcc operon expression only when aminopeptidases capable of McC processing are present, we hypothesized that MccE is involved in detoxification of internally processed McC. Below, this hypothesis is shown to be correct, and the molecular mechanism involved is revealed.

Overproduction of MccE C-terminal Domain Renders Cells Resistant to McC

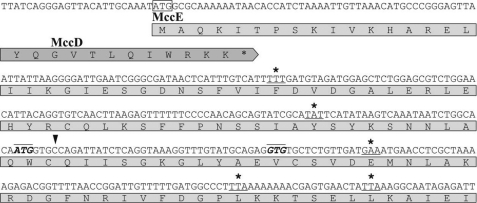

If MccE were involved in detoxification of McC, then overexpression of mccE would be expected to make cells McC-resistant. Recent papers (17, 18) revealed a 1-bp difference (an insertion of a C:G base pair, indicated by a downward arrow in Fig. 3) between the earlier reported sequences of mcc operons carried on plasmids isolated in Spain (7) and Russia (8) and a more recent isolate (Fig. 3). We resequenced part of the mcc gene cluster of the Russian isolate between mccD and mccE and determined that the original sequence of Fomenko et al. (8) contained an error. The corrected sequence matches that of Smajs et al. (18). The correction of the sequence led to an ambiguity in the assignment of the mccE start codon, which was originally proposed to begin with an ATG (7, 8) located ∼190 bp downstream of the last codon of mccD (Fig. 3). In the corrected sequence, this codon is out of frame with the mccE open reading frame. Cursino et al. (17) proposed that in their sequence, a nearby downstream in-frame GTG could serve as a start codon (Fig. 3). Smajs et al. (18) proposed that translation of MccE is initiated much more upstream, from an ATG codon overlapping with mccD (Fig. 3). For our purposes, it was essential to know the exact starting point of the mccE gene. To this end, several amber mutations were introduced in the “non-coding” sequence between mccD and the previously annotated downstream mccE start sites (MccE codons substituted for amber codons are indicated by asterisks in Fig. 3). The mutant plasmids were introduced into the wild-type and pepA− pepB− pepN− E. coli cells, and McC production was monitored. The results indicated that McC production was only observed when host cells lacked aminopeptidases (data not shown), whereas cells harboring wild-type pUHAB produced McC whether aminopeptidases were present or not, as expected. Thus, plasmids with each of the amber mutations tested behaved as the original mccE− plasmid (above) and therefore destroyed the mccE function. The correct mccE start site must therefore be located upstream of the introduced amber codons and therefore matches the site proposed by Smajs et al. (18) overlapping with the mccD gene.

FIGURE 3.

Determination of the mccE start codon. Partial sequence of the mccABCDE operon downstream of the mccD gene is shown. Three proposed start codons of the mccE gene are indicated (two codons are highlighted by boldface italic type and overlines; one, which partially overlaps with mccD, is boxed). An extra base pair that was absent in earlier sequences is shown by a downward arrow. Positions where stop codons described under “Results” were introduced are underlined and highlighted by asterisks.

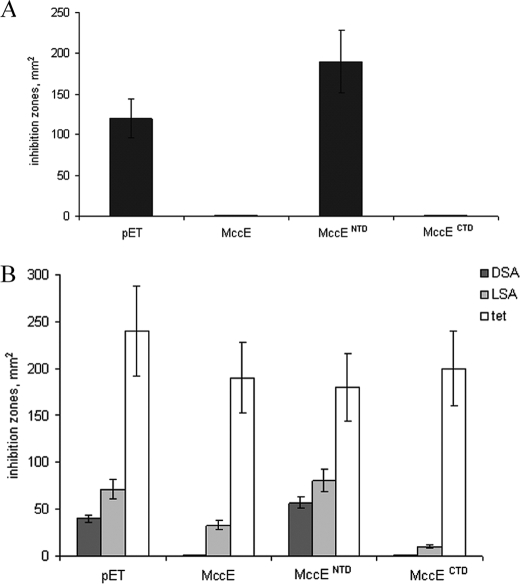

Overexpression of the “long version” of mccE (starting with an ATG that is located within the mccD gene) from a pET plasmid made McC-sensitive BL21(DE3) E. coli cells resistant to McC (Fig. 4A). In contrast, cells harboring the pET vector remained fully sensitive (Fig. 4A). We therefore conclude that MccE alone can provide resistance to McC, at least when overexpressed.

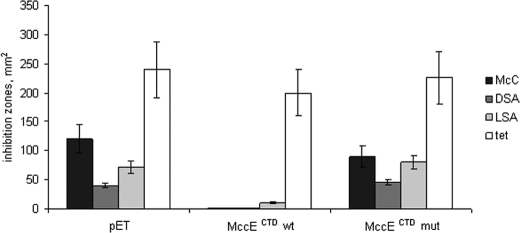

FIGURE 4.

Overproduction of full-size MccE or MccE C-terminal domain renders cells resistant to McC, DSA, and LSA. A, the sizes of growth inhibition zones around drops of McC (10 μg/ml) solutions deposited on cell lawns formed by the indicated cells are shown. B, the sizes of growth inhibition zones around drops of solutions of DSA, LSA, and tetracycline deposited on cell lawns formed by the indicated cells are shown. Error bars show standard deviations of measurements obtained in at least three independent experiments.

MccE is a two-domain protein; the N-terminal domain (MccENTD) is similar to decarboxylases, and the C-terminal domain (MccECTD) is similar to RimL, an acetylase of ribosomal protein L12 (19). Although in most bioinformatically identified mcc operons mccE homologs encode a single two-domain protein, in two bacteria, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Synechococcus sp. CC9605, the two domains of the MccE homolog are encoded by separate genes (4), suggesting that each domain is independently folded and may possess separate function(s). We created pET-based plasmids expressing individual domains of MccE. The domain boundaries were selected based on sequence comparisons with split homologs from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Synechococcus sp. CC9605. The beginning of MccENTD corresponded to the longest version of MccE (above), and the end was located after Lys407. The N terminus of recombinant MccECTD corresponded to Lys407 of full-sized MccE. Plasmids expressing MccE domains were introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells, and the ability of cells to grow in the presence of McC was determined. Overproduction of MccENTD did not lead to McC resistance (Fig. 4A). In contrast, cells overproducing MccECTD were resistant to McC (Fig. 4A). In the case of MccENTD, the lack of McC resistance was not due to low levels of overproduction and/or poor solubility of the target protein (data not shown). We therefore conclude that overproduction of MccECTD is sufficient for McC resistance.

Overproduction of MccECTD Renders Cells Resistant to Non-hydrolyzable Aminoacyl-adenylates

If MccECTD is involved in detoxification of residual processed McC, then one can expect that cells overproducing this domain will also be resistant to DSA, a non-hydrolyzable analog of processed McC (Fig. 1D). Indeed, cells overproducing full-size MccE or MccECTD (but not MccENTD) became resistant to DSA (Fig. 4B). We also tested the ability of cells overproducing MccECTD to grow in the presence of LSA, a non-hydrolyzable leucyl-adenylate analogue inhibiting leucyl-tRNA synthetase (20). Cells overproducing MccE were partially resistant, whereas cells expressing MccECTD were fully resistant to LSA (Fig. 4B). Control cells harboring pET vector or cells overproducing MccENTD were sensitive. The observed effects were specific because cells overproducing MccE domains were as sensitive to a control antibiotic (tetracycline) as cells containing pET vector (Fig. 4B). Additional experiments showed that overproduction of MccE and/or MccECTD rendered cells resistant to GSA, ASA, FSA, and KSA, sulfamoyl-adenylates containing, respectively, glycyl, alanyl, phenylalanyl, and lysyl aminoacyl moieties (data not shown). The results thus indicate that MccECTD targets processed McC and, more generally, that it is also involved in inactivation of non-hydrolyzable aminoacyl-adenylates containing primary amines, apparently irrespective of the nature of the aminoacyl moiety side chain.

MccECTD Is an Acetyltransferase

Bioinformatic analysis indicates that MccECTD is homologous to bacterial Nα-acetyltransferases of the Rim family (4, 8). We hypothesized that MccECTD acetylates aminoacyl-adenylates, thus preventing their interaction with (and inhibition of) their cognate aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Purified MccECTD was combined with the likely donor of acetyl groups, acetyl-CoA, and DSA, LSA, or ESA substrates (the last compound does not permeate E. coli cells and therefore was not tested in the in vivo experiments described above), and the rate of production of free CoA that should be generated during the acetylation reaction was determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The results, presented in Table 1, demonstrate that efficient production of CoA from acetyl-CoA was observed when MccECTD and any one of the three AaSAs tested were present in the reaction, consistent with the idea that the MccECTD catalyzes the transfer of acetyl from the acetyl-CoA donor onto AaSA substrates. No CoA production was detected in reactions that contained MccENTD instead of MccECTD (Table 1) or when MccECTD was incubated with McC or free amino acids instead of AaSAs (Table 1). Because the N terminus of McC is blocked by the presence of a formyl group (see Fig. 1B), we also determined whether deformylated McC, McC1149 (14), will act as a substrate for acetylation. However, as can be seen from Table 1, this compound was not recognized by MccECTD. We also tested whether malonyl-CoA can serve as a cofactor instead of acetyl-CoA in reactions containing full-size MccE or MccECTD. The results indicated that no substrate acetylation occurred in the presence of malonyl-CoA with either protein (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Acetyltransferase activity of MccE and its domains

Acetyltransferase reaction substrates listed in the left column were combined with the indicated proteins in the presence of acetyl-CoA; reactions were incubated for various times, and aliquots were used to determine the amount of free CoA formed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The values represent calculated reaction rates (pmol/min). Averages obtained from three independent reactions are shown. McC(1149) is a derivative of McC lacking the N-terminal formyl group (14).

| MccENTD | MccECTD | MccECTD mutant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| McC | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| McC(1149) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asp | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Glu | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Leu | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DSA | 0 | 19.8 ± 1.9 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

| ESA | 0 | 40 ± 10.0 | 4.0 ± 1.6 |

| LSA | 0 | 47.3 ± 10.3 | 2.4 ± 1.0 |

To show that acetylating activity of MccECTD is necessary for McC resistance, we created a plasmid overproducing an MccECTD mutant containing a double substitution of Ser553 and Glu572 for alanines and tested the ability of this plasmid to provide McC, DSA, and LSA resistance to E. coli cells. MccE Ser553 and Glu572 are homologous to Salmonella typhimurium RimL residues Ser141 and Glu160, respectively. Based on structural considerations, RimL Ser141 could function as a general acid, whereas Glu160 could serve as a general base in the RimL active center during the catalysis of the acetylation reaction (19). Substitution of these residues should therefore have a strong effect on the rate of the acetylation reaction. Despite the fact that the mutant and the wild-type versions of MccECTD were overproduced to the same levels (data not shown), cells harboring the plasmid expressing the mutant version of MccECTD were sensitive to McC, DSA, and LSA, whereas cells expressing wild-type MccECTD were, as expected, resistant (Fig. 5). Similar results were obtained with other AaSAs that possessed antibacterial activities (data not shown). In vitro analysis of acetylating activity of the mutant protein demonstrated that the rate of DSA acetylation was decreased ∼25-fold by the mutation (Table 1). We therefore conclude that wild-type levels of MccE acetylation activity are required for resistance to McC, DSA, and LSA.

FIGURE 5.

Overproduction of MccE C-terminal domain with Ser553 and Glu572 double alanine substitution does not lead to McC, DSA, or LSA resistance. See the legend to Fig. 4. wt, wild type; mut, mutant. Error bars show standard deviations of measurements obtained in at least three independent experiments.

Chemical Characterization of MccE Acetylation Products

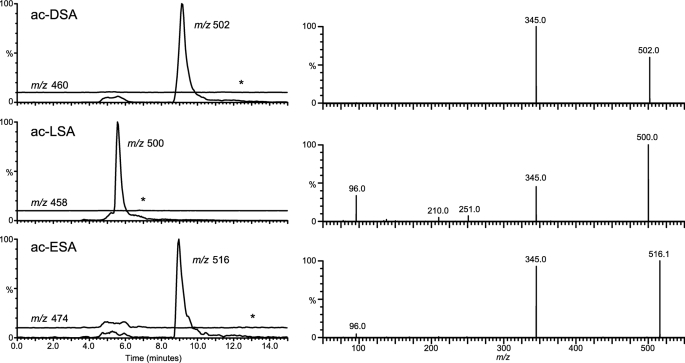

The products of MccE-catalyzed in vitro acetylation of DSA, LSA, and ESA were separated by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography, a convenient method for analysis of polar compounds not easily retained on reversed phase columns. During hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography, the more apolar acetylated reaction products should elute earlier than the starting compounds. Indeed, the presence of peaks eluting earlier than the starting DSA, LSA, and ESA was detected during hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography analysis of the products of MccE-catalyzed acetylation reactions. The starting compounds and the material from the earlier eluting peaks were analyzed by mass spectrometry. Negative ionization mode was used because the sulfamoyl moiety has acidic properties and can be deprotonated. No traces for the original unacetylated compounds (m/z values of 460, 458, and 474 for DSA, LSA, and ESA, correspondingly) were found in extracted ion chromatograms of the products of acetylation reactions (Fig. 6, left, see the 10% offset line). Instead, for each of the three AaSAs used, compounds with m/z values increased by 42 from corresponding unacetylated m/z values were present, consistent with acetylation. The absence of m/z signals for unacetylated compounds indicates 100% conversion of starting AaSAs under the conditions used.

FIGURE 6.

AaSAs undergo full conversion to their acetylated counterparts upon incubation with MccE. Mass spectrometric analysis of the acetylation reaction proves that the acetylation takes place at the α-amino group of the amino acid moiety. Left, extracted ion chromatograms of the injected reaction mixtures are shown. Each chromatogram contains the trace for monitoring the modified and the unmodified compound, respectively. The traces for the m/z of the unmodified compounds are offset by 10% for clarity, and asterisks indicate the expected position of the unmodified species, which proved absent. Top, acetyl-DSA (ac-DSA); middle, acetyl-LSA (ac-LSA); bottom, acetyl-ESA (ac-ESA). Right, fragment ion spectra of the acetylated compounds. Top, acetyl-DSA; middle, acetyl-LSA; bottom, acetyl-ESA. Collision energies were 10, 20, and 15 eV, respectively.

To determine the site of acetylation, the reaction products were characterized by acquisition of fragment ion spectra. Cleavage of the sulfonamide group yields an abundant ion with m/z of 345, which is observed for each of the native (not shown) and acetylated (Fig. 6, right) compounds. The common fragment corresponds to the nucleotide moiety of AaSAs. Therefore, it is the aminoacyl moiety that undergoes acetylation. Because either aspartyl, glutamyl, or leucyl moieties are acetylated, the acetyl group must be located on the α-amino group.

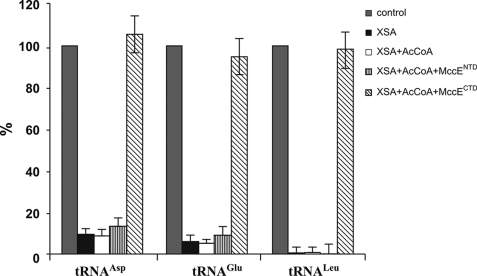

Acetylated AaSAs Do Not Inhibit Cognate tRNA Synthetases

To reconcile the results of the in vitro acetylation assays with in vivo data, one has to postulate that acetylated AaSAs lose the ability to inhibit cognate tRNA synthetases. To check this idea, aliquots of acetylation reactions containing AaSAs were combined with E. coli S30 extracts, and tRNAAsp, tRNALeu, and tRNAGlu aminoacylation reactions were performed (Fig. 7). In agreement with our expectations, aminoacylation reactions conducted in the presence of AaSAs acetylated by MccECTD proceeded as efficiently as in the absence of inhibitors. In contrast, reactions conducted in the presence of AaSAs that had been preincubated with MccENTD and acetyl-CoA or acetyl-CoA alone were fully inhibited. Thus, upon acetylation by MccECTD, AaSAs lose the ability to inhibit aminoacylation of cognate tRNAs.

FIGURE 7.

Acetylated AaSAs have no effect on tRNA aminoacylation reactions by cognate aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. E. coli S30 extracts were supplemented with indicated AaSAs that were previously incubated with acetyl-CoA alone or with acetyl-CoA and MccENTD or MccECTD at conditions that allow complete acetylation of AaSAs (see Fig. 6), and tRNA aminoacylation reactions with the indicated radioactive amino acids were carried out. The amounts of aminoacylated tRNA (measured as incorporation of 14C-labeled Asp, Leu, or Glu in trichloroacetic acid-precipitatable material) are shown. Control reactions show levels of aminoacylation in S30 extracts without any additions. Error bars show standard deviations of measurements obtained in at least three independent experiments.

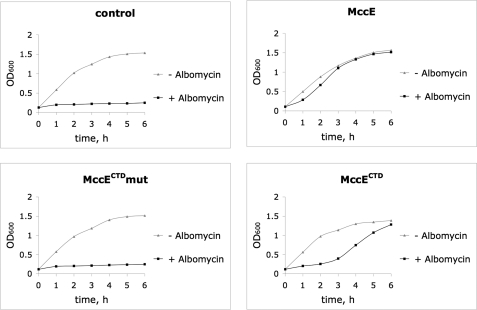

MccE Acetyltransferase Makes Cells Resistant to Albomycin When Overexpressed

Albomycin is a Trojan horse inhibitor that consists of a ferrichrome-like siderophore coupled to a serine that is attached to a thioxylofuranosyl pyrimidine (21). Upon entering cells through the FhuA ferrichrome transporter, albomycin is processed by aminopeptidases with the release of a non-hydrolyzable seryl-thioxylofuranosyl pyrimidine (22) that inhibits seryl-tRNA synthetase (23). As can be seen from Fig. 8, expression of full-size MccE and MccECTD, but not MccECTD carrying Ser553 and Glu572 substitutions, led to albomycin resistance, indicating that the product of albomycin processing is probably acetylatated (and consequently detoxified) by overexpressed MccECTD acetyltransferase. Cells carrying the pUHAB plasmid were partially resistant to albomycin but, naturally, resistant to McC (data not shown). Cells carrying a pUHAB plasmid carrying mccE with substitutions in the catalytic site residues were fully sensitive to albomycin. Thus, MccE acetyltransferase provides protection to albomycin even when expressed in a natural context of the mccABCDE operon.

FIGURE 8.

Overexpression of MccECTD makes cells resistant to albomycin. E. coli BL21(DE3) cells harboring PET28 vector plasmid (control) or PET28-based plasmids expressing the indicated proteins were grown in liquid LB in the presence or in the absence of albomycin (0.1 μg/ml). At the indicated time points, aliquots of cultures were removed, and A600 values were recorded. Representative results of three independent experiments are presented.

DISCUSSION

The principal result of this work is demonstration that the acetylating activity of the C-terminal domain of the MccE protein contributes to McC resistance by acetylating the amino group of processed McC. As a result of this activity, processed McC that inevitably accumulates in McC-producing cells is inactivated, allowing continuous production of McC without the loss of cell viability. In the absence of McC processing by cellular aminopeptidases, processed McC is not accumulated, and acetyltransferase activity of MccE becomes dispensable for McC production.

Previous work demonstrated that cells harboring a plasmid containing the mcc operon with disrupted mccE produce an McC derivative without the aminopropyl group (14). The same compound is produced by cells lacking functional mccD, whose product is homologous to methyltransferases (4, 14). The acetyltransferase activity of MccE is not required for the synthesis and/or attachment of the aminopropyl moiety because cells harboring an McC production plasmid with mccE encoding a mutant protein harboring the double substitution of Ser553 and Glu572 to Ala, which strongly decreases the acetyltransferase activity, produce McC with the aminopropyl group attached (data not shown). This result indicates that MccENTD, whose sequence is similar to decarboxylases, is responsible for the synthesis and/or attachment of the aminopropyl group to the peptide-nucleotide formed from the MccA heptapeptide by the action of MccB, a homolog of ubiquitin-like protein-activating enzymes (24, 25).

The MccE acetyltransferase appears to be specifically capable of recognition of aminoacyl-nucleotides. The nature of this amino acid appears to be unimportant because all compounds tested in this work (containing Asp, Glu, and Leu) as well as seryl- and alanyl-sulfamoyl-adenylates (data not shown) are efficiently acetylated by MccE. The nature of the bond between the aminoacyl and nucleotide moiety seems also unimportant because compounds containing a phosphonamide or a sulfamoyl are recognized as well as the C–C coupled serinyl-thioxylofuranosyl group in processed albomycin. Finally, the nature of nucleotide (adenosine or pyrimidine) is likewise not critical. Nevertheless, MccE cannot use free amino acids or intact McC lacking the formyl group as substrates. Structural analysis will be needed for further insights into substrate specificity determinants of the MccE acetyltransferase.

One of the results of this work is an unambiguous identification of the starting codon of the mccE gene. To date, each of the three mcc sequences deposited in publicly available data bases has had a different proposed starting codon for mccE. Establishment of the correct mccE start codon was important because shorter versions of recombinant MccE synthesized from downstream start codons appeared to be non-functional (i.e. they failed to provide resistance to McC) (data not shown). Our results show that mccE partially overlaps with upstream mccD, suggesting that the two proteins, which are jointly required for aminopropyl addition, may be synthesized in a coordinate manner. In fact, after the reassignment of the mccE start codon, it is evident that all mcc genes coding for McC biosynthesis and immunity partially overlap. Such an overlap may lead to coordinated expression of MccA maturation machinery. In fact, individual maturation enzymes may form a complex with the MccC immunity pump, which would both increase the efficiency of McC maturation and decrease the steady state levels of McC in the cytoplasm, thus providing an additional way of preventing the producing cells from intoxication by internally produced processed McC.

MccECTD belongs to the GNAT (Gcn5-related acetyl transferase) superfamily of proteins. Members of the superfamily perform a large variety of cellular functions, including the regulation of gene expression and inactivation of toxic metabolites and antibiotics. The closest MccECTD relatives are bacterial RimL proteins (supplemental Fig. 1). The MccE acetyltranferease domain is more distantly related to other Rim proteins (RimI and RimJ, each specifically acetylating a dedicated ribosomal protein), bacterial GNAT enzymes, and eukaryotic homologs (supplemental Fig. 1). Although physiological significance of ribosomal protein acetylation by Rim acetyltransferases is still not fully understood, it is tempting to speculate that these proteins may have an additional role and acetylate aminoacyl-nucleotides that accumulate either via cell metabolism or as a result of antibiotic treatment, thus contributing to bacterial cell fitness.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health, NIAID, North Eastern Biodefense Center Grant U54 AI057158. This work was also supported by the Burroughs Wellcome Career Award, a Russian Academy of Sciences Presidium program in Molecular and Cellular Biology new groups grant, a Rutgers University Technology Commercialization Fund Grant (to K. S.), and Russian Foundation for Basic Research Grants 06-04-48865 (to A. M.) and 09-04-13825 (to K. S.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- AspRS

- aspartyl-tRNA synthetase

- IPTG

- isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside

- AaSA

- aminoacyl-sulfamoyl-adenosine

- HPLC

- high pressure liquid chromatography

- DSA

- aspartyl-sulfamoyl-adenosine

- LSA

- leucyl-sulfamoyl-adenosine

- ESA

- glutamyl-sulfamoyl-adenosine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baquero F., Bouanchaud D., Martinez-Perez M. C., Fernandez C. (1978) J. Bacteriol. 135, 342–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baquero F., Moreno F. (1984) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 23, 117–124 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Destoumieux-Garzón D., Peduzzi J., Rebuffat S. (2002) Biochimie 84, 511–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Severinov K., Semenova E., Kazakov A., Kazakov T., Gelfand M. S. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 65, 1380–1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guijarro J. I., González-Pastor J. E., Baleux F., San Millán J. L., Castilla M. A., Rico M., Moreno F., Delepierre M. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 23520–23532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metlitskaya A. Z., Katrukha G. S., Shashkov A. S., Zaitsev D. A., Egorov T. A., Khmel I. A. (1995) FEBS Lett. 357, 235–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.González-Pastor J. E., San Millán J. L., Moreno F. (1994) Nature 369, 281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fomenko D. E., Metlitskaya A. Z., Péduzzi J., Goulard C., Katrukha G. S., Gening L. V., Rebuffat S., Khmel I. A. (2003) Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 47, 2868–2874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Metlitskaya A., Kazakov T., Kommer A., Pavlova O., Praetorius-Ibba M., Ibba M., Krasheninnikov I., Kolb V., Khmel I., Severinov K. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 18033–18042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kazakov T., Vondenhoff G. H., Datsenko K. A., Novikova M., Metlitskaya A., Wanner B. L., Severinov K. (2008) J. Bacteriol. 190, 2607–2610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reader J. S., Ordoukhanian P. T., Kim J. G., de Crécy-Lagard V., Hwang I., Farrand S., Schimmel P. (2005) Science 309, 1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kazakov T., Metlitskaya A., Severinov K. (2007) J. Bacteriol. 189, 2114–2118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bode R., Thurau A. M., Schmidt H. (1993) Arch. Microbiol. 160, 397–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metlitskaya A., Kazakov T., Vondenhoff G. H., Novikova M., Shashkov A., Zatsepin T., Semenova E., Zaitseva N., Ramensky V., Van Aerschot A., Severinov K. (2009) J. Bacteriol. 191, 2380–2387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreno F., Gónzalez-Pastor J. E., Baquero M. R., Bravo D. (2002) Biochimie 84, 521–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fomenko D., Veselovskii A., Khmel I. (2001) Res. Microbiol. 152, 469–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cursino L., Smajs D., Smarda J., Nardi R. M., Nicoli J. R., Chartone-Souza E., Nascimento A. M. (2006) J. Appl. Microbiol. 100, 821–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smajs D., Strouhal M., Matejková P., Cejková D., Cursino L., Chartone-Souza E., Smarda J., Nascimento A. M. (2008) Plasmid 59, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vetting M. W., de Carvalho L. P., Roderick S. L., Blanchard J. S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 22108–22114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finking R., Neumüller A., Solsbacher J., Konz D., Kretzschmar G., Schweitzer M., Krumm T., Marahiel M. A. (2003) Chembiochem 4, 903–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benz G., Schroder T., Kurz J., Wunsche C., Karl W., Steffens G., Pfitzner J., Schmidt D. (1982) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 21, 527–528 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braun V., Günthner K., Hantke K., Zimmermann L. (1983) J. Bacteriol. 156, 308–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng Y., Roy H., Patil P. B., Ibba M., Chen S. (2009) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 4619–4627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Regni C. A., Roush R. F., Miller D. J., Nourse A., Walsh C. T., Schulman B. A. (2009) EMBO J. 28, 1953–1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roush R. F., Nolan E. M., Löhr F., Walsh C. T. (2008) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3603–3609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.