Abstract

HET-C2 is a fungal protein that transfers glycosphingolipids between membranes and has limited sequence homology with human glycolipid transfer protein (GLTP). The human GLTP fold is unique among lipid binding/transfer proteins, defining the GLTP superfamily. Herein, GLTP fold formation by HET-C2, its glycolipid transfer specificity, and the functional role(s) of its two Trp residues have been investigated. X-ray diffraction (1.9 Å) revealed a GLTP fold with all key sugar headgroup recognition residues (Asp66, Asn70, Lys73, Trp109, and His147) conserved and properly oriented for glycolipid binding. Far-UV CD showed secondary structure dominated by α-helices and a cooperative thermal unfolding transition of 49 °C, features consistent with a GLTP fold. Environmentally induced optical activity of Trp/Tyr/Phe (2:4:12) detected by near-UV CD was unaffected by membranes containing glycolipid but was slightly altered by membranes lacking glycolipid. Trp fluorescence was maximal at ∼355 nm and accessible to aqueous quenchers, indicating free exposure to the aqueous milieu and consistent with surface localization of the two Trps. Interaction with membranes lacking glycolipid triggered significant decreases in Trp emission intensity but lesser than decreases induced by membranes containing glycolipid. Binding of glycolipid (confirmed by electrospray injection mass spectrometry) resulted in a blue-shifted emission wavelength maximum (∼6 nm) permitting determination of binding affinities. The unique positioning of Trp208 at the HET-C2 C terminus revealed membrane-induced conformational changes that precede glycolipid uptake, whereas key differences in residues of the sugar headgroup recognition center accounted for altered glycolipid specificity and suggested evolutionary adaptation for the simpler glycosphingolipid compositions of filamentous fungi.

Keywords: Lipid-binding Protein, Lipid Transport, Membrane Biophysics, Protein Structure, X-ray Crystallography

Introduction

Self/nonself recognition is a universally important process, encompassing intercellular interactions ranging from vertebrate immune responses to somatic chimera formation in protists, filamentous fungi, sponges, ascidians, and tunicates. Self/nonself discrimination becomes critical for filamentous fungi during hyphal fusion, which enables the exchange of cytoplasm and nuclei during the assimilative growth phase (1–4). Nonself recognition triggers a postfusion, programmed cell death process known as vegetative incompatibility, which leads to heterokaryon death. The benefits of vegetative incompatibility include prevention of transmission of deleterious cytoplasmic elements (i.e. viruses) as well as restriction of plundering by parasitic genotypes.

het genes are known to play a major role in vegetative incompatibility processes that occur in Neurospora crassa and Podospora anserina. het genes exhibit extensive polymorphism and generally encode proteins carrying a HET domain (1–4). Originally, this domain was linked to the het-c2 gene of P. anserina, where it was shown to encode a protein similar in size and with limited sequence homology to mammalian glycolipid transfer proteins (GLTPs)5 (5, 6). HET-C2 was shown to stimulate in vitro intermembrane transfer of galactosylceramide, but not sphingomyelin, ceramide, phosphatidylcholine, or cholesterol (7). Similar glycolipid specificity is displayed by mammalian GLTPs (8), which accomplish transfer using a distinct two-layer “sandwich motif,” dominated by α-helices and without intramolecular disulfide bonds (9–11). A binding site for a single glycolipid molecule consists of a sugar headgroup recognition site located where the sugar-amide portion of the glycolipid is tethered via multiple hydrogen bonds to the protein's surface. A hydrophobic pocket, lined with nonpolar amino acid residues, encapsulates a major portion of the nonpolar hydrocarbon chains of the glycolipid ceramide region. The novel architecture of GLTP and its lipid liganding pocket are distinguishing features compared with other lipid binding and transfer proteins, which use conformational folds dominated by the β-sheet (i.e. β-grooves/concave cups and β-barrels) or helical bundles stabilized by multiple disulfide-bridges (i.e. saposin folds (8–10)). Accordingly, the human GLTP fold serves as the prototype for the GLTP superfamily (12, 13). Nonetheless, other protein folds (e.g. saposin, nonspecific LTP, and phosphatidylinositol transfer protein) are able to bind/transfer glycolipid (14–21).

Currently, there is a lack of experimental data elucidating HET-C2 structure/conformation, leaving the issue of GLTP fold formation by HET-C2 unresolved. Also, HET-C2 transfer specificity for different glycolipids and the functional roles of the two Trp residues of HET-C2 in glycolipid binding and/or membrane interaction remain undefined. Herein, these issues are addressed. The different positioning of Trp residues in HET-C2 provides new insights into the membrane interaction region of the GLTP fold, whereas x-ray diffraction reveals the structural basis for the altered glycolipid specificity of the HET-C2 GLTP fold.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression and Purification of HET-C2

HET-C2 was expressed and purified as detailed for GLTP (22). The P. anserina open reading frame encoding HET-C2 (NCBI GenBankTM number U05236) was subcloned (7) into pET-30 Xa/LIC (Novagen) by ligation-independent cloning. Transformed BL21 cells (Escherichia coli) were grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37 °C overnight, induced with isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (0.1 mm), and then grown for 16–20 h at 15 °C. Purification of rHET-C2 from soluble lysate protein was accomplished by Ni2+-NTA affinity chromatography. The N-terminal His-S tag was removed by factor Xa, yielding protein identical in sequence to native HET-C2. HET-C2 was repurified by FPLC SEC using a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex-75 preparation grade column (Amersham Biosciences). For crystallographic studies, HET-C2 was expressed using pET-SUMO vector (Invitrogen). The His-Sumo tag (N terminus) was cleaved using Ulp1 SUMO protease (Invitrogen). HET-C2 fractions obtained by SEC were pooled, centrifugally concentrated (10 kDa cut-off membrane), and verified for purity by SDS-PAGE.

Crystallization of HET-C2

Reductive methylation of surface lysines was carried out to aid crystallization as described previously (23). Methylated HET-C2 was purified by SEC, and the extent of methylation was assessed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Methylated and unmethylated HET-C2 were concentrated to 30 mg/ml for crystallization screening. Diffraction quality crystals of methylated HET-C2 were obtained in 0.1 m BisTris (pH 5.5–6.5) and 25% polyethylene glycol 3350.

Structure Determination

For data collection at cryogenic temperatures, crystals were stabilized in mother liquor supplemented with 20% ethylene glycol. X-ray diffraction data for the methylated HET-C2 crystal was collected on beamline ID24-E at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory). This data set was processed using the HKL2000 suite (24). Systematic absences indicated that the crystals belonged to space group P41212 or P43212. The volume of the crystal asymmetric unit was compatible with only one subunit and a protein volume per unit of molecular mass of 2.9 Å3 Da−1 with a calculated solvent content of 58.1% (v/v). The structure was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER (25) with human apoGLTP (Protein Data Bank 1SWX) structure as a search model in space group P41212. Refinement was carried out using REFMAC (26) alternating with manual building in COOT (27). The final structure was validated using PROCHECK (28). Statistics for data collection, refinement, and final model geometry are summarized in Table 1. Secondary structural elements were assigned using DSSP (29).

TABLE 1.

X-ray data collection and refinement statistics for HET-C2

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9792 |

| Space group | P41212 |

| Unit cell | |

| a, b, c | 96.93, 96.93, 57.91 |

| α, β, γ | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0-1.9 (1.97-1.9) |

| Total reflections | 379,083 |

| Unique reflections | 22,551 |

| I/σI | 36.8 (2.9) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.9 (93.9) |

| Redundancy | 8.7 (6.0) |

| Rmerge | 7.2 (35.9) |

| Refinement | |

| R/Rfree | 21.6/24.8 |

| Average B-factor | |

| Protein | 37.9 |

| Water | 43.6 |

| No. of atoms | |

| Protein | 1577 |

| Water | 118 |

| RMSDa | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.016 |

| Bond angles (degrees) | 1.512 |

| Ramachandran statistics (%) | |

| Mostly allowed regions | 95.5 |

| Allowed regions | 4.5 |

| Generously allowed regions | 0.0 |

| Disallowed regions | 0.0 |

a Root mean square deviation.

Glycolipid Transfer Activity of HET-C2

Glycolipid intervesicular transfer activity of purified HET-C2 (or GLTP) was monitored by established assays involving glycolipid labeled with either radioactivity or fluorescent probes (30–33) (see supplemental material for details).

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

CD spectra were collected using a J-810 spectropolarimeter (JASCO) equipped with a CTC-345 temperature control system at 0.05 mm HET-C2 in 10 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.4; 10 °C) while purging continuously with N2. Spectral and temperature dependence measurements in the far-UV range (185–250 nm) were performed at a 2-nm bandwidth using a U-type quartz cell (0.148-mm path length) and in the near-UV range (250–320 nm) at 1 nm bandwidth with a rectangular cell (0.5-cm path length) in a custom-built thermostated cell holder (34–37). Five accumulations were recorded, each at a 20-nm/min scan rate with a 2-s response time. The temperature dependence of ellipticity at 222 nm was measured using a 60 °C/h scan rate and 8-s response time. Solvent evaporation was prevented by placing a drop of oil (repeatedly boiled in water to remove soluble impurities) on the top of the sample cell. CD spectra in the far-UV range were smoothed using the JASCO noise reduction routine. The CDPro program suite (34), a modified version of three methods (SELCON3 (35), CONTIN/LL locally linearized approximation (38) of CONTIN (39), and CDSSTR (40)), was used to calculate HET-C2 secondary structure from far-UV CD spectra. Tertiary structure class was assessed using the CDPro CLUSTER program (37) (see supplemental material for details).

Measurement of Protein Concentration

HET-C2 concentration was measured at 280 nm using a DU 640 spectrophotometer (Beckman) at 1.8-nm bandwidth and a molar absorptivity of 17.12 mm−1 cm−1, obtained by averaging results from four calculation methods (41–44). Spectra were corrected for turbidity by plotting the log dependence of the solution absorbance versus the log of the wavelength and extrapolating the linear dependence between these quantities in the 340–440 nm range to the 240–300 nm absorption range, using the DU-640 scatter correction routine. Extrapolated absorbance values were subtracted from measured values, decreasing the apparent protein absorbance at ∼280 nm by ∼15%.

Fluorescence Measurements

Trp fluorescence (295 nm excitation) was measured at 25 °C from 310 to 420 nm with a SPEX Fluoromax spectrofluorometer (Horiba Scientific) using excitation and emission bandpasses of 5 nm. Protein concentration was kept at A295 < 0.1 to avoid inner filter effects (45, 46). Fluorescence quenching experiments were performed by adding aliquots of acrylamide or KI (5 m) stocks in 10 mm sodium phosphate-saline buffer (pH 7.4) to HET-C2 (1 μm; 2.5 ml) with constant stirring at 25 °C. With KI, 10 mm sodium thiosulfate was added to the stock solution to prevent the formation of I3−, which absorbs in the region of Trp fluorescence (45). Data were corrected for dilution effects and analyzed using the Stern-Volmer and modified Stern-Volmer equations as detailed in the supplemental material.

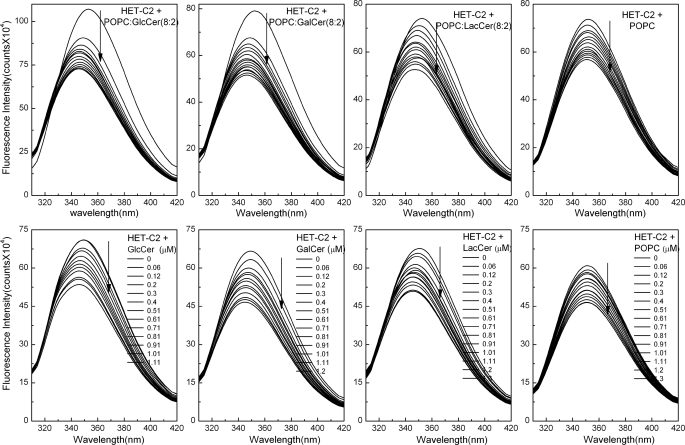

Membrane Interaction and Glycolipid Binding by HET-C2

To assess membrane interaction, vesicles consisting of POPC/glycolipid (8:2) (1.5 mm) or POPC (1.5 mm) were added stepwise to HET-C2 (1 μm) in small aliquots while monitoring Trp emission. Lipids also were presented to HET-C2 by microinjection after dissolving in ethanol as recently detailed by Zhai et al. (46). Measurements were performed under constant stirring by the addition of small aliquots (1 μl) of GSL, dissolved in ethanol (0.1 mm), to protein (1 μm; 2.5 ml). Fluorescence titration curves were analyzed according to Equation 1,

where Kd is the dissociation constant of lipid-protein complex, m is lipid concentration, and n is the number of lipid binding sites (47, 48). ϵ is the spectral parameter value (emission wavelength maximum (λmax expressed as wavenumber) or relative intensity, I) accompanying lipid binding to HET-C2 at lipid concentration m. Thus, ϵ can represent either I/I0 or (λmax)0/λmax, where the subscript 0 indicates values in the absence of lipid. ϵb represents spectral properties of the protein-lipid complex. According to Equation 1, the slope of ϵ − 1 versus (ϵ − 1)/m yields Kd/n and represents the reciprocal of the protein/lipid association constant.

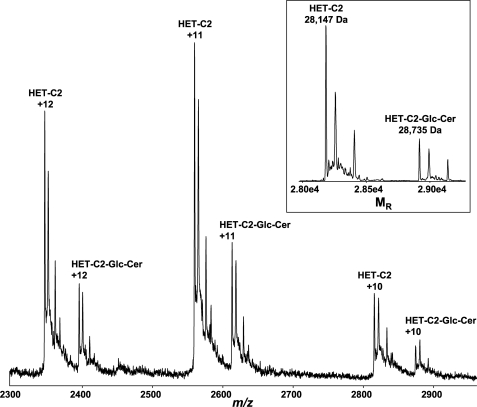

Mass Spectrometry

HET-C2 and HET-C2-glycolipid complex (10 μm protein) were analyzed using an Agilent MSD-TOF mass spectrometer (Santa Clara, CA) in 5 mm ammonium acetate by infusing directly into the electrospray source. Spectra were collected in positive mode over a 500–5000 m/z range using parameters optimized for complex stability (e.g. capillary, 3000 V; fragmentor, 300 V; skimmer, 60 V; Oct RF, 300 V; Oct DC, 32 V. Raw spectral data were transformed into relative molecular masses using the Agilent TOF Protein Confirmation software.

RESULTS

Structure and Glycolipid Specificity of HET-C2

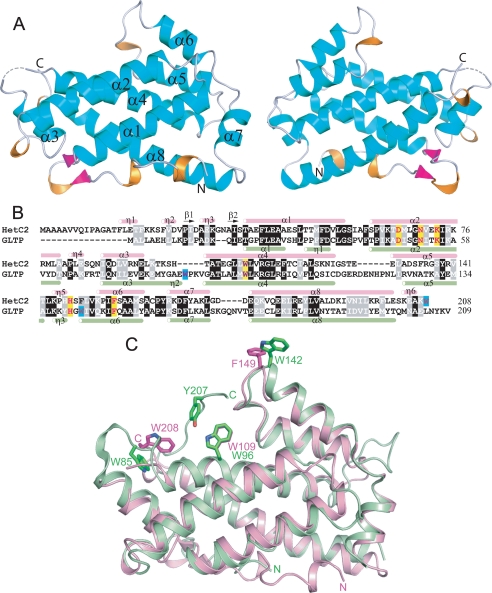

Limited sequence homology between HET-C2 and porcine GLTP was first noted by Saupe et al. (5). Subsequently, glycolipid intermembrane transfer by HET-C2 was shown with radiolabeled and fluorescently labeled galactosylceramide (7). These findings occurred prior to structural resolution of human GLTP and mapping of the glycolipid binding site in the GLTP fold (9–11). To define HET-C2 conformation and localize residues potentially involved in glycolipid binding, the HET-C2 structure was solved by x-ray crystallography. Formation of high quality crystals of apoHET-C2 was greatly facilitated by mild reductive methylation of surface Lys residues (23), enabling resolution to 1.9 Å by molecular replacement (human apoGLTP was the search model) (9, 10). The electron density throughout the polypeptide chain was of good quality except for residues 1–13 and 99, presumably due to disordering. The final crystallographic model was refined to R and Rfree values of 21.6 and 24.8%, respectively (Table 1). The HET-C2 conformational architecture strongly resembles the human GLTP fold (9, 10), showing the distinctive two-layer “sandwich motif” dominated by α-helices (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S1). Like GLTP, HET-C2 has eight α-helices with one layer consisting of α1, α2, α6, and α7, whereas α3, α4, α5, and α8 make up the other layer. Unlike GLTP, a small anti-parallel β-sheet is present near the N terminus of HET-C2. The two Cys residues (Cys118 and Cys162) present in HET-C2 are too far apart for disulfide stabilization. The N-terminal region of HET-C2 is disordered, as in GLTP, but is more extended by ∼16 amino acids (Fig. 1, B and C). Superpositioning of HET-C2 and human GLTP shows that most residues present in the sugar binding pocket and hydrophobic channel are conserved. In HET-C2, Asp66, Asn70, Lys73, Trp109, and His147 are properly positioned to form a sugar headgroup binding site, selective for glycolipids (Fig. 2A). This putative sugar headgroup recognition center is located at the entrance to a hydrophobic pocket, where the nonpolar hydrocarbon chains of the glycolipid are expected to localize. The hydrophobic pocket is lined by 2 dozen nonpolar residues, most of them identical to those lining the hydrophobic pocket of GLTP (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 1.

A, tertiary structure of HET-C2 in the apo-form. Front and back views of HET-C2 are shown with α-helices (cyan), 310 helices (orange), β-sheet (magenta), and loop segments (light gray) in a schematic diagram. B, structure-based sequence alignment between HET-C2 and human GLTP. Secondary structural elements of HET-C2 (pink) and GLTP (light green) are shown above and below the aligned sequences by tubes indicating 310 (η) and α-helices (α) and arrows indicating β-strands (β). Conserved residues that interact with the ceramide-linked sugar of glycolipids are highlighted in yellow in GLTP and HET-C2. Nonbinding site Trp residues are highlighted in turquoise. C, structural superposition of HET-C2 (pink) and human GLTP (green). Key aromatic residues are shown in stick representation. Trp142 of GLTP and Phe149 of HET-C2 are localized on the surface and are completely accessible to the aqueous milieu. Human apoGLTP structure was solved previously (9, 10).

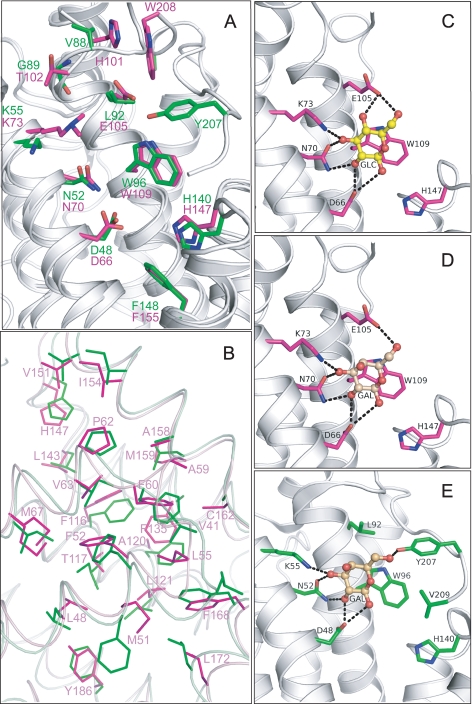

FIGURE 2.

A, structural superposition of HET-C2 (magenta) and GLTP (green) showing conserved residues present in the pocket that interacts with the sugar-amide moiety of glycolipids. Lys73 in HET-C2 is shown containing the exogenous dimethyl group introduced to facilitate crystallization. Human apoGLTP structure was solved previously (9, 10). B, residue homology and similarity between hydrophobic pockets of HET-C2 and human GLTP. For clarity, only HET-C2 residues have been labeled. The following positional correspondence is observed for HET-C2 and GLTP, respectively: Leu48 = Leu30, Met51 ≈ Phe33, Phe52 = Phe34, Leu55 = Leu37, Ala59 ≈ Val41, Phe60 = Phe42, Pro62 = Pro44, Val63 ≈ Ile45, Met67 ≈ Ile49, Phe116 = Phe103, Thr117 ≈ Ile104, Ala120 ≈ Phe107, Leu121 = Leu108, Phe135 ≈ Ala128, Leu143 = Leu136, His147 = His140, Val151 = Val144, Ile154 = Ile147, Ala158 = Ala151, Met159 ≈ Leu152, Cys162 ≈ Ala155, Phe168 = Phe161, Leu172 = Leu165, Tyr186 ≈ Phe183. C, docking of Glc onto the GSL headgroup binding site of HET-C2. Side chains of HET-C2 residues involved in Glc binding are shown in magenta. The Glc sugar ring is colored yellow with red balls representing oxygen. The black dotted lines represent hydrogen bonds. To provide spatial relationships reflecting the situation in wild type HET-C2, the exogenous dimethyl group added to Lys73 to facilitate HET-C2 crystallization is not shown. D, docking of Gal onto the GSL headgroup binding site of HET-C2. The color scheme is the same as for C except that the galactose sugar ring is colored beige. E, docking of galactose onto the GSL headgroup binding site of human GLTP. The color scheme is the same as for D except that the side chains of GLTP residues involved in Gal binding are shown in green. The galactose location is derived from Protein Data Bank entry 2EVL (10).

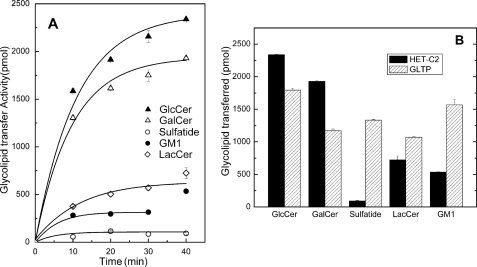

Despite conservation of so many key residues in HET-C2, subtle structural differences raised the possibility of altered selectivity for glycolipids compared with GLTP, which can transfer a variety of glycolipids of differing structural complexity (8). The only glycolipid tested earlier with HET-C2 was GalCer (7). In fungi, glucosylceramide (GlcCer) is more widespread than GalCer, but both GalCer and GlcCer reportedly occur in filamentous fungi (49–51). We found that HET-C2 readily transfers GlcCer (Fig. 3), surpassing that of GLTP. LacCer is transferred by HET-C2 but not nearly as well as GlcCer or GalCer. Unlike GLTP, HET-C2 transferred negatively charged glycolipids (i.e. sulfatide or ganglioside GM1) very poorly.

FIGURE 3.

HET-C2 transfer of different glycolipids between membrane vesicles. A, transfer time course for different radiolabeled glycolipids by HET-C2 at 25 °C using a fixed protein amount (0.5 μg). HET-C2 preferentially transfers glycolipids with headgroups consisting of a single uncharged sugar. B, comparison of HET-C2 and GLTP transfer of different glycolipids at 25 °C using fixed protein amounts (0.5 μg) as detailed in the supplemental material. In contrast to HET-C2, GTLP readily transfers glycolipids with charged and complex sugar headgroups. The data points were fit using a first order exponential fitting routine. All data points represent duplicate assays (average values).

To elucidate the structural basis for the glycolipid selectivity of HET-C2, comparative sugar docking was performed using high resolution GLTP-GalCer and GLTP-LacCer complexes (9, 10) as guides (Fig. 2, C–E). In HET-C2, Trp109 serves as a stacking platform that facilitates the hydrogen bonding of Asp66, Asn70, and Lys73 with Gal or Glc in the same way that Trp96 facilitates the hydrogen bonding network of Asp48, Asn52, and Lys55 with Gal or Glc in human GLTP (9, 10). However, in HET-C2, residues corresponding to Tyr207 and Val209 of GLTP are absent, and Leu92 in GLTP is replaced by Glu105 in HET-C2. Docking of Glc and Gal shows that Glu105 of HET-C2 forms one hydrogen bond with Gal and two hydrogen bonds with Glc (Fig. 2, C and D), thus compensating for the absence of hydrogen bond formation by Gal (and Glc) with GLTP Tyr207 (Fig. 2E). The location of negatively charged Glu105 seems to impede interactions with 3-sulfo-GalCer (sulfatide).

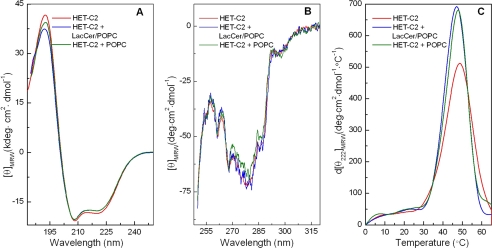

Circular Dichroism of HET-C2

HET-C2 conformation in solution as well as in the presence of membrane vesicles containing or lacking glycolipid was assessed by far-UV and near-UV CD. Fig. 4A shows far-UV CD spectra characteristic of high helical content in secondary structure. Calculations summarized in supplemental Table S1 indicate 56.6% helix, 8.8% β-structure, 12.1% β-turns, and 24.1% random. Incubation of HET-C2 with POPC vesicles either lacking or containing glycolipid resulted in little change in the far-UV CD spectra and secondary structure calculations showing 54.5% α-helix, 9% β-structure, 12.8% β-turns, and 24% random (supplemental Table S1).

FIGURE 4.

Circular dichroism of HET-C2. A, far-UV CD. The spectra indicate high helical content in HET-C2 with large negative n-π* transitions at 222 nm as well as π-π* transitions split into two transitions because of exciton coupling, resulting in negative bands at ∼208 nm and positive bands at ∼192 nm. Data are presented in units of molar ellipticity per residue. B, near-UV CD. Slightly altered spectral signals from Tyr/Trp are obtained by incubation of apoHET-C2 with membranes lacking glycolipid but not with membranes containing glycolipid, consistent with small conformational changes triggered by membrane interaction. C, derivative plots for temperature dependence of molar ellipticity at 222 nm. The relatively low midpoints of the unfolding transitions are consistent with a lack of conformational stabilization by intramolecular disulfides, as expected for a GLTP fold. ApoHET-C2 conformation is slightly destabilized by membrane interaction. Spectra were recorded at pH 7.4 as detailed under “Experimental Procedures.”

Near-UV CD spectra (Fig. 4B), which reflect tertiary structure, showed significant environmentally induced optical activity arising from the four Tyr and two Trp residues (270–300 nm) of HET-C2. The negative signals at ∼255, 262, and 268 nm probably belong to the 12 Phe residues; the prominent negative signal near ∼277 nm probably originates from the four Tyr residues and/or two Trp residues; and the small negative peak near ∼287 nm probably arises from the two Trp residues. When vesicles containing glycolipid were incubated with HET-C2, the near-UV CD signal was unaffected. Interestingly, incubation of HET-C2 with membranes lacking glycolipid resulted in slightly decreased near-UV CD signal from Tyr and/or Trp.

Thermally induced unfolding provided insights into HET-C2 stability at pH 7.4. The first derivative of the CD signal at 222 nm as a function of temperature (Fig. 4C) revealed a highly cooperative unfolding transition between 25 and 55 °C, with a midpoint of ∼49 °C. The relatively low unfolding temperature midpoint is consistent with a lack of stabilization by intramolecular disulfides. HET-C2 incubation with membranes lacking or containing glycolipid slightly decreased the unfolding transition temperature midpoint and decreased peak broadening, suggesting membrane-enhanced cooperativity of unfolding (Fig. 4C).

Intrinsic Fluorescence of HET-C2 Trp

Because Trp residues are important for glycolipid binding and membrane interaction of GLTP (8, 9, 45, 46, 52–55), we characterized the Trp emission of HET-C2. HET-C2 has two Trp and four Tyr residues in its 208-residue sequence. In contrast, GLTP has three Trp and 10 Tyr residues among its 209 residues. Sequence alignment shows that the number and location of intrinsic fluorescent residues differ greatly in HET-C2 and GLTP (Fig. 1B). One of the two Trp residues in HET-C2 aligns with GLTP Trp96, a key residue for sugar headgroup interaction in the glycolipid binding site. The other HET-C2 Trp does not align with either of the remaining two GLTP Trp residues, one of which (Trp142) seems to be directly involved in GLTP-membrane interactions. Superpositioning of the structures of HET-C2 and GLTP (Figs. 1C and 2A) shows that Trp109 of HET-C2 is well located to play a similar role as GLTP Trp96 within the glycolipid sugar headgroup recognition center. In contrast, Trp208 at the HET-C2 C terminus resides on the surface but in a location much different from that of GLTP Trp142. HET-C2 Trp was found to fluoresce maximally (λmax) at ∼355 nm (supplemental Fig. S3). Denaturation with 8 m urea caused the λmax to red shift only ∼2 nm. The red-shifted λmax of wild-type HET-C2 suggests a relatively polar, average environment for the two Trp residues, consistent with surface localization rather than burial in the hydrophobic core (45, 56).

The accessibility and environment of the Trp residues were further evaluated using aqueous quenchers. Fig. 5 (top left) shows that acrylamide quenched >90% of the average Trp emission signal of HET-C2, consistent with exposure of Trp residues to the aqueous milieu. Quenching with KI resulted in a ∼76% decrease in Trp emission signal (supplemental Fig. S6). The lower quenching efficiency by KI was consistent with charged residues residing near either or both Trp residues. With both quenchers, the quenching efficiency decreased slightly upon denaturation of HET-C2 with 8 m urea (supplemental Fig. S4). Stern-Volmer plots were linear under all conditions for HET-C2, consistent with dynamic quenching at physiological pH and ionic strength (Fig. 5, bottom). Modified Stern-Volmer analyses enabled quantitative determination of the fraction of accessible Trp residues (supplemental Figs. S5 and S6). In native HET-C2, Trp emission intensity was 100% accessible to both quenchers, whereas, in urea-denatured protein, Trp accessibility was reduced to 72% for KI (Table 2). Collectively, the data show that the two HET-C2 Trp residues are in a polar environment exposed to the aqueous milieu (45, 56), consistent with the surface localization shown by x-ray diffraction.

FIGURE 5.

HET-C2 Trp emission quenching by acrylamide. Top, intrinsic Trp quenching in the presence of increasing concentrations of acrylamide (vertical arrows). Bottom, Stern-Volmer analyses of the acrylamide quenching response performed as described in the supplemental materials. The correlation coefficients are 0.999 except for LacCer/POPC vesicles (0.998). Values derived from the plots for quenching constants and Trp accessibility are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Analysis of tryptophan fluorescence quenching

KSV and KQ are Stern-Volmer and modified Stern-Volmer quenching constants, respectively, and fa is fractional accessibility. The data represent the extent of quenching and accessibility achieved for both quenchers. The average values obtained for the quenching constants have S.D. values of 5% or less, whereas those of the fa values are less than 1%.

| Protein | Acrylamide |

KI |

Quenching |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KSV | KQ | fa | KSV | KQ | fa | Acrylamide | KI | |

| % | % | |||||||

| HET-C2 | 19.97 | 15.4 | 1.0 | 6.9 | 7.75 | 0.97 | 90 | 76 |

| HET-C2, denatured | 15.48 | 8.8 | 1.0 | 4.48 | 8.6 | 0.72 | 87 | 70 |

| HET-C2 + POPC/GlcCer (8:2) vesicles | 10.33 | 10.7 | 0.94 | 84 | ||||

| HET-C2 + POPC/LacCer (8:2) vesicles | 12.88 | 11.5 | 0.96 | 88 | ||||

| HET-C2 + POPC vesicles | 19.45 | 12.6 | 1.0 | 88 | ||||

Incubation of HET-C2 with membrane vesicles in the presence of quenchers also provided insights into interactions with membranes and glycolipid. When the vesicles lacked glycolipid, the Trp signal was fully accessible to acrylamide quenching (Fig. 5, top right). In the presence of vesicles containing glycolipid, Trp emission was slightly protected from acrylamide quenching. The findings are consistent with membrane interaction of HET-C2 being transient and rapid during glycolipid acquisition/release rather than forming long lived protein-lipid complexes. It is also noteworthy (Table 2) that the Stern-Volmer (KSV) and modified Stern-Volmer quenching constants (KQ) were reduced in the presence of vesicles containing glycolipid, reflecting diminished quenching efficiency compared with HET-C2 Trp in the absence of vesicles.

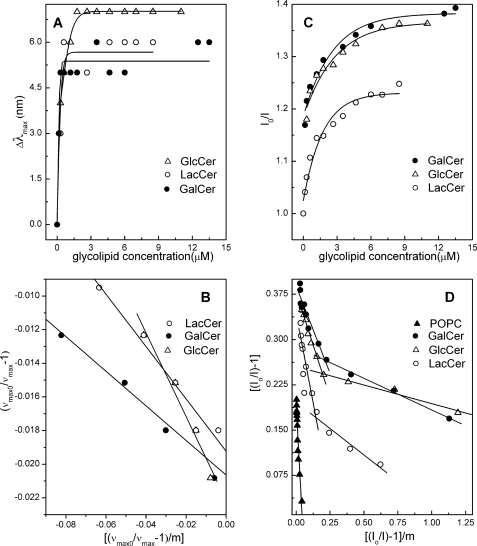

Intrinsic Trp Fluorescence Changes Induced by Membranes Containing or Lacking Glycolipid

ApoGLTP exhibits a red-shifted Trp λmax (∼348 nm). High resolution x-ray diffraction data and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry analyses show an absence of bound glycolipid in human GLTP expressed in E. coli (9–11, 46). The red-shifted Trp emission λmax of HET-C2 (355 nm) suggested a lack of bound glycolipid, affording the opportunity to determine whether the Trp emission signal of HET-C2 becomes altered by uptake of glycolipid and/or by interaction with membranes containing or lacking glycolipid. Fig. 6 (top) shows that the stepwise addition of POPC vesicles containing glycolipid results in reduction of Trp emission intensity (25–29%) as well as a 6-nm λmax blue shift (355 → 349 nm) (Table 3). It is noteworthy that the λmax blue shift ceases after a slight excess of glycolipid has been added, but the intensity continues to steadily decrease. In contrast, the stepwise addition of POPC vesicles lacking glycolipid (Fig. 6, top right) produces almost no λmax blue shift (1 nm) but a substantial reduction in emission intensity (∼17%). The different Trp emission responses with membranes containing or lacking glycolipid suggested that both glycolipid binding and protein interaction with the membrane contribute to the response. The blue shift is indicative of glycolipid binding, whereas the intensity decrease reflects both glycolipid binding and membrane interaction. For this reason, the blue shift was used to assess the binding affinity of HET-C2 for different glycolipids. Kd values for the binding isotherms (Fig. 7, A and B) ranged from 0.15 to 0.2 μm (Table 4). To obtain meaningful Kd values from the emission intensity changes induced by glycolipid binding (Fig. 7, C and D), corrections were made for the membrane partitioning contribution to the POPC vesicles over the glycolipid concentration range producing blue shift (Table 4). With POPC vesicles lacking glycolipid, the intensity change yielded a Kd value of ∼5 μm for the membrane partitioning of HET-C2.

FIGURE 6.

Changes in HET-C2 Trp emission induced by lipids. Top, POPC vesicles containing or lacking glycolipid were introduced in stepwise fashion with 5-min incubation times between injections. The vertical arrows indicate increasing vesicle concentration. The first few injections of membrane vesicles containing GalCer or GlcCer (∼1.2 μm total available glycolipid by the third injection) induce a strong intensity decrease and λmax blue shift. Additional injections result in Trp emission intensity decreases of similar magnitude to those observed with POPC vesicles lacking glycolipid. The λmax blue shift occurred only when the vesicles contained glycolipid. Bottom, stepwise microinjection of lipids, dissolved in ethanol, was used to mix lipids with HET-C2 with 5 min incubation times between injections. The vertical arrows indicate increasing lipid concentration. The starting glycolipid injection and each incremental addition corresponded to ∼10-fold lower levels than with the vesicle additions (top). Fluorescence measurements were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Control injections enabled correction for dilution effects.

TABLE 3.

Trp fluorescence changes in HET-C2 induced by interaction with membranes containing/lacking glycolipid and by ethanol injection of glycolipid or phospholipid

Each glycolipid derivative contained octanoyl acyl chains. ν, wavenumber.

| Glycolipid | Small unilamellar vesicles |

Ethanol injection |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quenching | Blue shift | Δν × 104 | Quenching | Blue shift | Δν × 104 | |

| % | nm | cm−1 | % | nm | cm−1 | |

| GalCer | 29 | 6 | 0.49 | 30 | 5 | 0.41 |

| GlcCer | 26 | 7 | 0.57 | 25 | 4 | 0.33 |

| LacCer | 25 | 6 | 0.49 | 25 | 6 | 0.49 |

| POPC | 17 | 1 | 0.08 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

FIGURE 7.

HET-C2 binding analyses for different glycolipids presented as membrane vesicles containing or lacking glycolipid. A, blue shift in Trp emission wavelength maximum (Δλmax) of HET-C2 induced by POPC vesicles containing different glycolipids. B, analyses of Δλmax blue shift data expressed as wavenumber (ν). C, intensity (I) change in Trp emission of HET-C2 induced by POPC vesicles containing different glycolipids. D, analyses of intensity change data. Subscript 0 indicates values in the absence of added vesicles. Calculations utilized the approach of Bashford et al. (47) and were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

TABLE 4.

HET-C2 binding constants for glycolipids

Kd values were calculated from changes in emission intensity and from the λmax blue shift. Kd I is calculated from the emission intensity changes resulting from the addition of vesicles containing glycolipid after correction against vesicles lacking glycolipid. Saturation of glycolipid binding is indicated by cessation of the λmax blue shift. Kd II represents values calculated from emission intensity changes occurring even after saturation of the λmax blue shift and corresponding to both glycolipid binding and HET-C2 partitioning to the membrane interface. Note that all of the calculations were performed assuming that only half of the glycolipid in the vesicles is available for binding.

| Vesicle composition |

Kd |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength shift/Δν | Intensity change |

||

| I | II | ||

| GlcCer/POPC | 0.177 ± 0.10 | 0.13 ± 0.10 | 0.92 ± 0.32 |

| GalCer/POPC | 0.108 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.60 ± 0.03 |

| LacCer/POPC | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 0.41 ± 0.27 | 1.49 ± 0.43 |

| POPC | 5.26 ± 1.39 | ||

Presentation of Lipids to HET-C2 via Ethanol Microinjection

Recently, Zhai et al. (46) showed that microinjection involving small lipid aliquots dissolved in ethanol is useful for loading the glycolipid binding site of GLTP while minimizing the accumulation of excess membrane interface in solution, thus providing a means to distinguish emission changes induced by glycolipid binding from changes produced by nonspecific partitioning to membrane interface. Fig. 6 (bottom) shows the Trp emission response of HET-C2, titrated with lipid using the EtOH microinjection approach. With each successive injection of glycolipid, the HET-C2 Trp emission λmax became progressively more blue-shifted, whereas fluorescence intensity systematically decreased (25–30%). The emission responses observed for GlcCer, GalCer, and LacCer followed similar patterns. Kd values were similar to those obtained by vesicle addition.

Formation of a wild type HET-C2-glycolipid complex by EtOH microinjection of glycolipid was verified by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Fig. 8 shows spectra obtained by direct infusion of glycolipid-free HET-C2 plus HET-C2-GlcCer complex under nondenaturing conditions. Although ions corresponding to monomeric, glycolipid-free rHET-C2 (28,147 Da) dominate, there is clear evidence for formation of monomeric complex (rHET-C2 + GlcCer (28,735 Da)).

FIGURE 8.

Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry analysis of HET-C2-glycolipid complex. Three main charge states are observed from the direct infusion of the HET-C2:N-octanoyl GlcCer complex (2:1 molar ratio) under nondenaturing conditions. The transformed spectra (see inset) result in molecular masses of 28,147 Da for rHET-C2 and 28,735 Da for the rHET-C2-N-octanoyl GlcCer complex. The N-terminal His6-S tag accounted for the molecular mass being higher than wild type HET-C2 (23,179 Da).

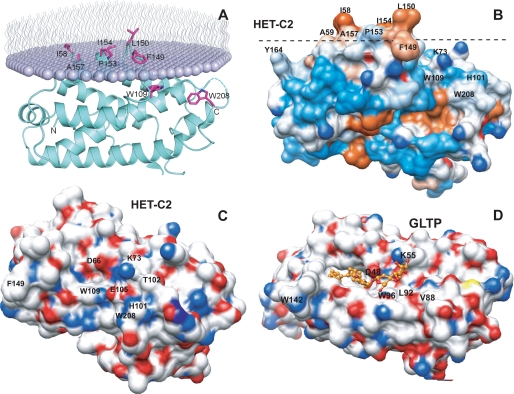

In the case of microinjection of ethanol-solubilized POPC, a non-glycolipid that is not transferred by HET-C2, no λmax blue shift was observed. Nonetheless, substantially decreased Trp intensity (∼17%) was evident (Fig. 6, bottom right). The latter finding was unexpected because ethanol-injected POPC has little effect on GLTP Trp emission intensity (46). The data suggested that interaction of HET-C2 with membrane alters the local environment of Trp208 either directly or by triggering conformational changes that precede glycolipid uptake. To evaluate further, membrane docking by HET-C2 was analyzed using the orientation of proteins in membranes (OPM) computational approach (57) and by assessing HET-C2 surface hydrophobicity (58, 59). In OPM analyses, optimal rotational and translational positioning of the protein with respect to the lipid bilayer is achieved by minimization of protein transfer energy from water to the membrane hydrocarbon core, approximated as decadiene nonpolar solvent, and to interfacial regions characterized by water permeation profiles. In the approximation, protein binding to the membrane is driven by hydrophobic interactions and opposed by desolvation of polar and charged groups. The three-dimensional structure of apoHET-C2 aided the identification of potential membrane-binding sites, protein tilt angles, and membrane penetration depths. OPM analyses (Fig. 9A) suggest that membrane docking involves Phe149, Leu150, Pro153, Ile154, and Ala157 of helix 6 and Ile58 of the adjacent α1–2 loop, which together form a hydrophobic patch (Fig. 9B and supplemental Fig. S7). In contrast, Trp208 and nearby residues do not seem to directly participate in the initial docking of HET-C2 to membranes.

FIGURE 9.

Surface topography of predicted membrane docking site of HET-C2 and sugar headgroup recognition site of HET-C2 and GLTP. A, HET-C2 orientation and positioning during membrane docking. The OPM computational approach (57) was used to identify residues involved in the initial docking of HET-C2 with the membrane interface. The lipid molecules comprising half of the membrane are shown as lavender-colored with wavy lines representing the lipid hydrocarbon chains. HET-C2 helices are cyan-colored, and important side chain residues are shown in magenta. B, surface hydrophobicity of HET-C2 (Protein Data Bank code 3KV0). Mapping was performed using Chimera (58, 59), which relies on the Kyte-Doolittle scale to rank amino acid hydrophobicity, with blue indicating most hydrophilic, white equaling 0.0, and orange-red being most hydrophobic. The dotted black line corresponds to the membrane interface oriented as shown in A. C, surface topology of the GSL sugar headgroup binding site of HET-C2. Surface residue color reflects charge status (red, negative; blue, positive; white, neutral). To provide spatial relationships reflecting the situation in wild type HET-C2, the exogenous dimethyl group added to Lys73 to facilitate HET-C2 crystallization is not shown. Glu105, Thr102, and His101 obstruct the surface adjacent to Trp109. D, surface topology of the GSL sugar headgroup binding site of human GLTP. Surface residue color reflects charge status (red, negative; blue, positive; white, neutral) for the GLTP-18:1 LacCer complex (Protein Data Bank code 1SX6) (9). 18:1 LacCer is depicted in gold with the hydrocarbon chains of ceramide (left) disappearing into the hydrophobic tunnel. The open, unobstructed surface adjacent to Trp96 allows for broader selectivity for binding of various glycolipids.

DISCUSSION

HET-C2 Forms a GLTP Fold

Our x-ray diffraction data (1.9 Å) establish that HET-C2 utilizes a GLTP fold to accomplish glycolipid transfer, even though other protein folds (e.g. saposins, nonspecific LTP, and phosphatidylinositol transfer protein) also are capable of binding/transferring glycolipids (14–21). Absolute conservation and homologous positioning are observed for Asp66, Asn70, Lys73, Trp109, and His147 in HET-C2 compared with Asp48, Asn52, Lys55, Trp96, and His140 in GLTP, residues known to form a sugar headgroup recognition center and confer selectivity for glycolipid binding (9, 10) (Figs. 1B and 2A and supplemental Fig. S2). In the hydrophobic pocket that encapsulates the lipid nonpolar chains, 14 of 24 residues are absolutely conserved, and another nine residues have similar physicochemical features (Fig. 2B). Far-UV CD analyses support GLTP fold formation by HET-C2, indicating a preponderance of helical secondary structure as well as a relatively low unfolding transition temperature midpoint (∼49 °C). Similar features are exhibited by porcine and bovine GLTPs (54, 60, 61) as well as by human GLTP.6 Our x-ray data rectify discrepancies with previous three-dimensional modeling of HET-C2 regarding identification of key residues of the sugar head group recognition center (11). In our three-dimensional jigsaw model (data not shown), the HET-C2 core region precisely superimposed with the crystallographic structure, but a different location emerged for C-terminal residues (Trp208), and no structure was obtained for the first 38 amino acids of the N terminus.

HET-C2 Membrane Interaction and Glycolipid Uptake

Interaction of HET-C2 with PC vesicles containing or lacking glycolipid produces no significant conformational changes in secondary structure as detected by far-UV CD. However, mixing with lipid vesicles does affect the thermal dependence of HET-C2 unfolding, including a slight lowering of the transition temperature midpoint (1–2 °C) and increased cooperativity of the unfolding transition (Fig. 4C). The near-UV CD signal, originating from environmentally induced optical activity of Phe, Tyr, and Trp, is largely unaffected by incubation with PC vesicles containing glycolipid, consistent with diffraction data showing only subtle changes in tertiary folding as a consequence of glycolipid binding by GLTP (9, 10, 46). Nonetheless, when the vesicles lack glycolipid, a hint of tertiary change is observed in the near-UV CD signal associated with Tyr and/or Trp, prompting the further study of intrinsic Trp fluorescence in HET-C2.

The involvement of Trp in GLTP functionality is well established (8, 9, 45, 46, 51–55). In HET-C2, one (Trp109) of the two Trp residues aligns with GLTP Trp96, a key residue for sugar headgroup interaction in the glycolipid binding site. However, the other HET-C2 Trp residue (Trp208) does not align with either of the other two GLTP Trp residues. Fluorescence data show an emission wavelength maximum (λmax) at ∼355 nm and accessibility to aqueous quenchers, consistent with a relatively polar, average environment for the two Trp residues and localization on the protein surface. The crystallographic data (Figs. 1, 2, and 9 and supplemental Fig. S2) indicate that Trp109 is well positioned to play a similar role as Trp96 within the glycolipid sugar headgroup recognition center of GLTP. Trp208 at the HET-C2 C terminus is surface-accessible but at a different location than GLTP Trp142, a residue often linked to the GLTP-membrane interaction domain. Trp208 remains close to the α3-α4 loop via a stacking interaction with His101 (Fig. 2A).

With HET-C2, incubation with membrane vesicles containing glycolipid induces substantial decreases (25–30%) in Trp emission intensity and blue shifts in emission λmax (6–7 nm). With human GLTP, glycolipid binding also induces changes in Trp emission fluorescence (i.e. ∼40% intensity decrease and ∼12-nm blue shift in λmax) attributable almost entirely to stacking of the ceramide-linked sugar over Trp96 of the sugar headgroup recognition site (46). However, with HET-C2, POPC vesicles lacking glycolipid also elicit significant intensity decreases (∼17%), complicating determinations of glycolipid binding affinity based on intensity changes. Fortunately, the blue shifts in emission λmax depend on glycolipids being present in the vesicles. When the sugar headgroup is changed from glucose to galactose or lactose, the dramatic blue shift persists, thus providing a means to calculate glycolipid binding affinity. The resulting Kd values for various glycolipids indicate moderate binding strength by HET-C2, consistent with a role in glycolipid transfer. The Kd values also agree reasonably well with previous values for human GLTP calculated from the Trp intensity decrease. The Kd value for HET-C2 partitioning to POPC membranes is estimated to be ∼5 μm, which seems reasonable, considering values reported for other membrane interaction motifs (e.g. pleckstrin domain, range from 1.6 to 2.9 μm) (62).

A fundamental difference in the HET-C2 Trp response compared with human GLTP is the significant (∼17%) decrease in emission intensity induced by mixing with POPC via ethanol microinjection. Similar treatment leaves the GLTP Trp emission intensity nearly unaltered (46), despite the apparent involvement of Trp142 in the membrane interaction of GLTP. It is noteworthy that Trp142 of GLTP shows spatial homology with Phe149 of HET-C2, whereas Trp208 of HET-C2 localizes more similarly to Trp85 (Fig. 1C). OPM and surface hydrophobicity analyses support direct involvement of Phe149 in the initial docking of HET-C2 to the membrane interface (Fig. 9), but this is not the case for Trp208, despite seemingly favorable surface accessibility and positioning near the glycolipid binding site. Collectively, the findings point to the α1–2 loop and helix 6 (including Phe149) as defining the initial docking site with membranes, whereas the membrane-induced changes in Trp208 fluorescence seem to reflect conformational changes in HET-C2 immediately preceding glycolipid uptake.

Glycolipid Selectivity of HET-C2

The preference of HET-C2 for the two neutral monoglycosylceramides, GlcCer and GalCer, reflects a more narrowly focused selectivity for certain glycolipid types. Inclusion of a second sugar markedly slows transfer activity, whereas the addition of negatively charged sulfate to GalCer (i.e. sulfatide) nearly completely abolishes transfer. Low transfer rates also are observed with ganglioside GM1. It is noteworthy that the glycolipids most preferred by HET-C2 are naturally occurring in filamentous fungi, whereas the others are not (49–51). The more focused glycolipid selectivity of HET-C2 is shared by a plant glycolipid transfer protein recently discovered in Arabidopsis and designated AtGLTP1. West et al. (63) found that AtGLTP1 transfers GlcCer significantly faster than GalCer (∼8-fold) and much faster than LacCer (∼32.5-fold), whereas SM was not transferred at all. The strong preference of AtGLTP1 for GlcCer is not shared by GLTP or HET-C2, which transfer GlcCer and GalCer at roughly similar rates but faster than AtGLTP1. Modeling of AtGLTP1 indicates a GLTP fold and absolute conservation of residues most critical for glycolipid anchoring and selectivity (Asp52, Asn56, Arg59, Trp99, and His138 for AtGLTP1 versus Asp48, Asn52, Lys55, Trp96, and His140 for GLTP). Thus, to account for the selectivity of GlcCer over GalCer by AtGLTP1, West et al. (63) proposed that the OH4 hydroxyl in glucose, but not in galactose, is sufficiently close to interact with the amine group of Asn95 of AtGLTP1. It is noteworthy that negatively charged glutamic acid (Glu105) in HET-C2 occupies the site of Asn95 in AtGLTP1 and of Leu92 in human GLTP but that HET-C2, like GLTP, transfers GlcCer as fast or faster than GalCer. It is also noteworthy that all hydrogen bond classes observed in previous protein-carbohydrate interactions (64, 65) are seen when HET-C2 interacts with the GSL sugar headgroup. Among the classes are bidendate hydrogen bonding involving Asn70, bifurcated hydrogen bonds involving Asp66 (and Glu105 in the case of glucose), and cooperative hydrogen bond formation involving the multiple sugar hydroxyl groups and amino acid side chains.

Compared with GLTP, the surface region adjacent the sugar recognition center of HET-C2 displays considerably different topology (Fig. 9, C and D). In GLTP, this region has the appearance of a wide groove that flows unobstructed and openly away from Trp96, enabling accommodation of sugar headgroups of varying length and complexity, whereas in HET-C2, residues adjacent to Trp109 form impediments that constrict this region, effectively generating a surface pit best able to accommodate glycolipids with single, neutral sugar headgroups. Two structural differences in HET-C2 accounting for the altered surface topology are 1) a shorter C terminus ending with Trp208 and 2) a α3-α4 loop shorter by 5 residues (amino acids 96–101) than the α3-α4 loop (amino acids 78–88) of GLTP with compositional differences, such as negatively charged Glu105, His101, and Thr102 at the same respective locations as Leu92, Val88, and Gly89 in GLTP. Steric hindrance and charge repulsion effects by Glu105 are likely to impede sulfatide binding. Glu105 also forms a water-bridged hydrogen bond with His101, helping orient its imidazole ring for stacking (∼3.4 Å) against the Trp208 indole ring. Nearby Thr102 is bulkier than Gly89 of GLTP and is Cβ-branched, restricting possible conformations and placing bulkiness near the protein backbone. Thus, the net effect of the shorter α3-α4 and C-terminal loops is formation of the bulky His101–Trp208 stack next to Glu105 and Thr102, leading to the pitlike morphology of the HET-C2 sugar headgroup recognition center that favors a neutral monoglycosyl headgroup. It is tempting to speculate that the focused selectivity of the HET-C2 GLTP fold for specific glycolipid types reflects evolutionary divergence and adaptation for the simpler glycolipid compositions of filamentous fungi compared with mammals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Béatrice Turcq of the Université de Bordeaux for providing the het-c2 construct. UCSF Chimera (used to produce the molecular graphics image shown in Fig. 9 (B–D)) was provided by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (National Institutes of Health Grant P41 RR-01081).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health, NIGMS, Grants GM45928 and GM34847 and National Institutes of Health, NCI, Grant CA121493. This work was also supported by Russian Foundation for Basic Research Grant 09-04-00313, the Abby Rockefeller Mauzé Trust, and the Dewitt Wallace, Maloris, Mayo, and Hormel Foundations.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S7.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3KV0) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

R. K. Kamlekar, R. Kenoth, S. Y. Venyaminov, and R. E. Brown, unpublished observations.

- GLTP

- glycolipid transfer protein

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- POPC

- 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-l-phosphatidylcholine

- Cer

- ceramide

- Lac

- lactose

- OPM

- orientation of proteins in membranes

- GM1

- Galβ1→3GalNAc1→4[Neu5Acα2→3]Galβ1→4Glcβ1→1Cer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Glass N. L., Kaneko I. (2003) Eukaryot. Cell 2, 1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saupe S. J. (2000) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 489–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fedorova N. D., Badger J. H., Robson G. D., Wortman J. R., Nierman W. C. (2005) BMC Genomics 6, 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paoletti M., Saupe S. J., Clavé C. (2007) PLoS ONE 2, e283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saupe S., Descamps C., Turcq B., Bégueret J. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 5927–5931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin X., Mattjus P., Pike H. M., Windebank A. J., Brown R. E. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 5104–5110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattjus P., Turcq B., Pike H. M., Molotkovsky J. G., Brown R. E. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 535–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown R. E., Mattjus P. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771, 746–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malinina L., Malakhova M. L., Teplov A., Brown R. E., Patel D. J. (2004) Nature 430, 1048–1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malinina L., Malakhova M. L., Kanack A. T., Lu M., Abagyan R., Brown R. E., Patel D. J. (2006) PLoS Biol. 4, e362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Airenne T. T., Kidron H., Nymalm Y., Nylund M., West G., Mattjus P., Salminen T. A. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 355, 224–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murzin A. G., Brenner S. E., Hubbard T., Chothia C. (1995) J. Mol. Biol. 247, 536–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madera M., Vogel C., Kummerfeld S. K., Chothia C., Gough J. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D235–D239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bloj B., Zilversmit D. B. (1981) J. Biol. Chem. 256, 5988–5991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tilley S. J., Skippen A., Murray-Rust J., Swigart P. M., Stewart A., Morgan C. P., Cockcroft S., McDonald N. Q. (2004) Structure 12, 317–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoh F., Pons J. L., Gautier M. F., de Lamotte F., Dumas C. (2005) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 61, 397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolter T., Winau F., Schaible U. E., Leippe M., Sandhoff K. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 41125–41128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahn V. E., Leyko P., Alattia J. R., Chen L., Privé G. G. (2006) Protein Sci. 15, 1849–1857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snook C. F., Jones J. A., Hannun Y. A. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 927–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeats T. H., Rose J. K. (2008) Protein Sci. 17, 191–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rossmann M., Schultz-Heienbrok R., Behlke J., Remmel N., Alings C., Sandhoff K., Saenger W., Maier T. (2008) Structure 16, 809–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malakhova M. L., Malinina L., Pike H. M., Kanack A. T., Patel D. J., Brown R. E. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 26312–26320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walter T. S., Meier C., Assenberg R., Au K. F., Ren J., Verma A., Nettleship J. E., Owens R. J., Stuart D. I., Grimes J. M. (2006) Structure 14, 1617–1622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2007) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kabsch W., Sander C. (1983) Biopolymers 22, 2577–2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattjus P., Pike H. M., Molotkovsky J. G., Brown R. E. (2000) Biochemistry, 39, 1067–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mattjus P., Molotkovsky J. G., Smaby J. M., Brown R. E. (1999) Anal. Biochem. 268, 297–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown R. E., Jarvis K. L., Hyland K. J. (1990) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1044, 77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mattjus P., Kline A., Pike H. M., Molotkovsky J. G., Brown R. E. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 266–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sreerama N., Woody R. W. (2000) Anal. Biochem. 287, 252–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sreerama N., Venyaminov S. Y., Woody R. W. (1999) Protein Sci. 8, 370–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sreerama N., Venyaminov S. Y., Woody R. W. (2000) Anal. Biochem. 287, 243–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venyaminov S., Vassilenko K. S. (1994) Anal. Biochem. 222, 176–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Provencher S. W., Glöckner J. (1981) Biochemistry 20, 33–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Stokkum I. H., Spoelder H. J., Bloemendal M., van Grondelle R., Groen F. C. (1990) Anal. Biochem. 191, 110–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson W. C. (1999) Proteins 35, 307–312 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mihaly E. J. (1968) J. Chem. Eng. Data 13, 179–182 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gill S. C., von Hippel P. H. (1989) Anal. Biochem. 182, 319–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mach H., Middaugh C. R., Lewis R. V. (1992) Anal. Biochem. 200, 74–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pace C. N., Vajdos F., Fee L., Grimsley G., Gray T. (1995) Protein Sci. 4, 2411–2423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li X. M., Malakhova M. L., Lin X., Pike H. M., Chung T., Molotkovsky J. G., Brown R. E. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 10285–10294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhai X., Malakhova M. L., Pike H. M., Benson L. M., Bergen H. R., 3rd, Sugár I. P., Malinina L., Patel D. J., Brown R. E. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 13620–13628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bashford C. L., Chance B., Smith J. C., Yoshida T. (1979) Biophys. J. 25, 63–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin I., Ruysschaert J. M., Sanders D., Giffard C. J. (1996) Eur. J. Biochem. 239, 156–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olsen I., Jantzen E. (2001) Anaerobe 7, 103–112 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aoki K., Uchiyama R., Itonori S., Sugita M., Che F. S., Isogai A., Hada N., Hada J., Takeda T., Kumagai H., Yamamoto K. (2004) Biochem. J. 378, 461–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park C., Bennion B., François I. E., Ferket K. K., Cammue B. P., Thevissen K., Levery S. B. (2005) J. Lipid Res. 46, 759–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rao C. S., Chung T., Pike H. M., Brown R. E. (2005) Biophys. J. 89, 4017–4028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.West G., Nylund M., Peter Slotte J., Mattjus P. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1758, 1732–1742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neumann S., Opacić M., Wechselberger R. W., Sprong H., Egmond M. R. (2008) Adv. Enzyme Regul. 48, 137–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mattjus P. (2009) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788, 267–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lakowicz J. R. (2006) Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 3rd Ed., pp. 529–575, Springer, New York [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lomize A. L., Pogozheva I. D., Lomize M. A., Mosberg H. I. (2006) Protein Sci. 15, 1318–1333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E. (2004) J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sanner M. F., Olson A. J., Spehner J. C. (1996) Biopolymers 38, 305–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abe A., Sasaki T. (1989) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 985, 38–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nylund M., Mattjus P. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1669, 87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Temmerman K., Nickel W. (2009) J. Lipid Res. 50, 1245–1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.West G., Viitanen L., Alm C., Mattjus P., Salminen T. A., Edqvist J. (2008) FEBS J. 275, 3421–3437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Quiocho F. A., Vyas N. K. (1984) Nature 310, 381–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Quiocho F. A. (1986) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 55, 287–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.